2. Sappho’s Apple

© 2021 Adam Roberts, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0249.02

To step back from the last book of Middlemarch to the first. Eliot’s story opens with the general expectation among her friends and family that Dorothea will marry Sir James Chettam, the eligible and hearty if rather dim young baronet. This, of course, does not happen. Instead she becomes betrothed to Casaubon. But if Dorothea and Casaubon are mismatched, Dorothea and Sir James would have been just as ill-suited to one another, if in a different way, and surely everybody in the novel knows as much. Still, matchmaker Mrs. Cadwallader is not thereby discouraged:

It followed that Mrs. Cadwallader must decide on another match for Sir James, and having made up her mind that it was to be the younger Miss Brooke, there could not have been a more skilful move towards the success of her plan than her hint to the baronet that he had made an impression on Celia’s heart. For he was not one of those gentlemen who languish after the unattainable Sappho’s apple that laughs from the topmost bough.1

We take the point of her allusion: Sir James is a down-to-earth fellow, not the sort to go mooning after unattainable women.

Where did Eliot come across the ‘Sappho’s apple’ reference? It is from Karl Otfried Müller’s History of the Literature of Ancient Greece to the Period of Isocrates, which had appeared in English in 1840—translated by the man who was, a few years after its publication, to become Eliot’s lover, and whom she considered her husband, George Henry Lewes. This is what Lewes’s Müller says:

In a fragment lately discovered, which bears a strong impression of the simple language of Sappho, she compares the freshness of youth and the unsullied beauty of a maiden’s face to an apple of some peculiar kind, which, when all the rest of the fruit is gathered from the tree, remains alone at an unattainable height, and drinks in the whole vigour of vegetation; or rather (to give the simple words of the poetess in which the thought is placed before us and gradually heightened with great beauty and nature): ‘like the sweetapple which ripens at the top of the bough, on the topmost point of the bough, forgotten by the gatherers—no, not quite forgotten, but beyond their reach’.2

Müller adds a footnote: ‘the fragment is in Walz, Rhetores Graeci, vol. viii. p. 883’ and quotes the Greek:

οἷον τὸ γλυκύμαλον ἐρυεθεται ἄκρῳ ἐπ ̓ὕσδῳ,

ἄκρον ἐπ ̓ἀκροτάτῳ, λελάθοντο δὲ μαλοδρόπηες,

οὐ μὰν ἐκλελάθοντ΄͵ ἀλλ΄ οὐκ ἐδύναντ΄ ἐπίκεσθαι …

Sappho may have written as many as 10,000 lines of poetry, although today fewer than seven hundred lines survive. Despite her once widespread popularity, she fell out of favour in the centuries after her death, either because the Aeolic dialect of Greek in which she wrote came to be considered ugly, or else because of disapproval by the Christian church at her bisexuality. For most of the last thousand years Sappho has been known only by those poems and fragments that happened to be recorded by other writers: one whole poem, three partial poems and various shorter fragments and pieces, down (sometimes) to single words. Sappho’s poems had been extracted from these sources and published in separate volumes as early as the 1550s, and in 1681 the French scholar Anne Le Fèvre published an edition of Sappho that made her work more widely known across Europe. Then, in 1879, a papyrus containing a new fragment of Sappho was discovered at Faiyum in Egypt. Many more papyri have been discovered since that date, and our knowledge of Sappho is more extensive nowadays than at any time since classical antiquity. But such ‘new’ Sappho poems lay in the future as Eliot wrote Middlemarch.

Nonetheless, Müller in the 1840s describes Sappho’s apple poem as ‘a fragment lately discovered’. He does so, despite the fact that he was writing long before the discovery of any new Sappho papyri. How so? Because another scholar, Christian Walz, had worked through collections of unpublished manuscripts kept in various libraries and private collections in various European cities and in doing so had discovered a number of previously unknown words, lines and passages quoted by the manuscripts’ authors. Walz published these in a book called Rhetores graeci, ‘Rhetoricians of Greece’, a work which appeared simultaneously in Stuttgart, London and Paris. Much of what Walz had discovered was fairly dull, but some bits and pieces were more exciting—for instance, the three-line poem Müller quotes, which Walz had found in Syrianus’s commentary on Hermogenes’ On Forms (4th century BCE). Walz does not specifically identify this verse as being by Sappho (hence Müller’s caution: ‘a fragment which bears a strong impression of the simple language of Sappho’) although modern scholars are happier to make the attribution on the grounds of its dialect and closeness to the other things we know Sappho wrote.

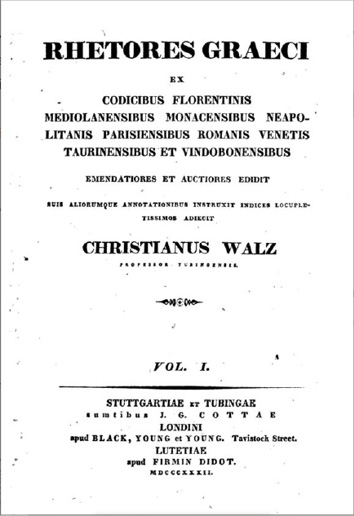

When, precisely, was this ‘fragment lately discovered’ discovered? You can see for yourself with Walz’s title page (see Fig. 1)

Fig. 1 Christianus Walz, Rhetores Graeci, vol. 1 (Stuttgart and Tubingen: J. G. Cotta, 1832), title page, https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Rhetores_Graeci_ex_codicibus_Florentinis/KzTGebC5F6gC?hl=en&gbpv=1. Public domain.

1832: just the period in which Middlemarch is set. This reference to ‘Sappho’s apple’, which Eliot came across in the book her lover had translated into English, could hardly be, in terms of the imagined world of Middlemarch, more up-to-date. A brand-new portion of Sappho had come into the world just as Eliot’s story is unfolding, and her narrator knows all about it.

It is, in other words, another instance of the scrupulousness and precision with which Eliot undertook the research that undergirds her novel. This aspect of her creative praxis has become, for good reason, one of the axioms of Eliot scholarship.3 And if part of that labour was in the service of what we might call, though it is a slippery term, ‘verisimilitude’—creating the textual conditions into which readers might safely suspend their disbelief in a positive sense, with precisely observed detail, and in a negative by avoiding the kinds of errors that ‘bounce’ a reader out of her faith in the story—another part consisted in assembling a matrix of textual reference, like this Sappho allusion, in which the story of Middlemarch itself might be situated and fortified.

The apple, here, is Dorothea Brooke (it is perhaps not coincidental that the ‘west brook’ is a variety of hard, speckled apple popular in the nineteenth-century), but also it is Eliot’s particular correlative for human love, not as a heavenly ideal, and neither down in the dirt, or too easily apprehended. Later in the novel, in another of the story’s three love stories, Fred Vincy rides to the house of Mary Garth, whom he loves. The occasion for the visit is that, having misjudged the sale of a horse, he is out of pocket. He owes a debt of £160 which Mary’s father has co-signed, and he can only pay back £50, even though the shortfall might ruin Mr. Garth. ‘But for Mary’s existence and Fred’s love for her’, Eliot tells us, ‘his conscience would have been much less active both in previously urging the debt on his thought and impelling him not to spare himself after his usual fashion by deferring an unpleasant task, but to act as directly and simply as he could’. So he rides out:

The Garth family, which was rather a large one, for Mary had four brothers and one sister, were very fond of their old house, from which all the best furniture had long been sold. Fred liked it too, knowing it by heart even to the attic which smelt deliciously of apples and quinces, and until to-day he had never come to it without pleasant expectations.4

Apples (plus quinces) are again elevated as a sign of the not-immediately-accessible love object, here located in the bourgeois comfort of a spacious house (such material considerations also being part of Mary’s appeal to Fred). First, though, he must ‘make his confession before Mrs. Garth, of whom he was rather more in awe than of her husband’—and whom, significantly, he encounters in the kitchen ‘her sleeves turned above her elbows […] pinching an apple-puff’—although she is herself described in terms of a different fruit, or fruit product: ‘the passage from governess into housewife had wrought itself a little too strongly into her consciousness […] the exemplary Mrs. Garth had her droll aspects, but her character sustained her oddities, as a very fine wine sustains a flavour of skin’. Apples more than once symbolically situate the Edenic possibilities offered, for Fred and also for Farebrother, represented by marriage to Mary and a place in amongst the Garths:

Caleb, rather tired with his day’s work, was seated in silence with his pocket-book open on his knee, while Mrs. Garth and Mary were at their sewing, and Letty in a corner was whispering a dialogue with her doll, Mr. Farebrother came up the orchard walk, dividing the bright August lights and shadows with the tufted grass and the apple-tree boughs.5

Farebrother, when he recognises that Mary loves not him but Fred, eventually does the decent thing. Still, one of the things Eliot is doing here is contrasting the elevated Sapphic of Dorothea with the more figuratively and literally down-to-earth apple of Mary Garth.

Mr. Farebrother left the house soon after, and seeing Mary in the orchard with Letty, went to say good-by to her. They made a pretty picture in the western light which brought out the brightness of the apples on the old scant-leaved boughs—Mary in her lavender gingham and black ribbons holding a basket, while Letty in her well-worn nankin picked up the fallen apples. If you want to know more particularly how Mary looked, ten to one you will see a face like hers in the crowded street to-morrow […] some small plump brownish person of firm but quiet carriage, who looks about her, but does not suppose that anybody is looking at her. If she has a broad face and square brow, well-marked eyebrows and curly dark hair, a certain expression of amusement in her glance which her mouth keeps the secret of, and for the rest features entirely insignificant—take that ordinary but not disagreeable person for a portrait of Mary Garth. […] Mary admired the keen-faced handsome little Vicar in his well-brushed threadbare clothes more than any man she had had the opportunity of knowing […] it was remarkable that the actual imperfections of the Vicar’s clerical character never seemed to call forth the same scorn and dislike which she showed beforehand for the predicted imperfections of the clerical character sustained by Fred Vincy. Will any one guess towards which of those widely different men Mary had the peculiar woman’s tenderness?—the one she was most inclined to be severe on, or the contrary? ‘Have you any message for your old playfellow, Miss Garth?’ said the Vicar, as he took a fragrant apple from the basket which she held towards him, and put it in his pocket. ‘Something to soften down that harsh judgment? I am going straight to see him.’6

Farebrother takes the apple, but Fred, Mary’s old playfellow, gets the girl. And when Fred calls, later in the novel, to plight his troth, it will not surprise us that he encounters the Garths, ‘the family group, dogs and cats included, under the great apple-tree in the orchard’.7 Eliot provides us with one last twist on this fructal theme. In her epilogue, by way of gratifying her reader’s curiosity as to what has happened with her main characters, Eliot confides:

There were three boys: Mary was not discontented that she brought forth men-children only; and when Fred wished to have a girl like her, she said, laughingly, ‘that would be too great a trial to your mother.’ Mrs. Vincy in her declining years, and in the diminished lustre of her housekeeping, was much comforted by her perception that two at least of Fred’s boys were real Vincys, and did not ‘feature the Garths.’ But Mary secretly rejoiced that the youngest of the three was very much what her father must have been when he wore a round jacket, and showed a marvellous nicety of aim in playing at marbles, or in throwing stones to bring down the mellow pears.8

The shift from apples to pears marks the natural development from generation to generation. There is, I suppose, some piquancy in the allusion to Lady Macbeth (in the reference to exclusively male children) there; although we can take this as a kind of irony. Few characters in literature are less Lady-Macbeth-like than Mary Garth, after all. At the same time there is something more than adventitious in the juxtaposition of Sappho and Shakespeare in Eliot’s textual matrix. The out-of-reach apple of Sappho stands for potential, for the start (perhaps) of something, just as the Edenic apple stands at the mythic start of everything. But Macbeth telling his wife that she should bring forth men-children only9 looks forward to an eventuality that the play closes-down. It is, in other words, the end of something—an end in which Lady Macbeth leaping to her death from the castle battlements, like Sappho leaping to her death from the cliffs of Lesbos, identifies as having to do with despair, derangement and femaleness. Or to put it a slightly different way, Macbeth is a play about the consequences of our actions. That looks, perhaps, like an over-facile summary of Shakespeare’s great drama, but it need not. Lady Macbeth, to a much greater extent than her husband, believes her actions will be both beneficial to her and consequence-free. Accordingly it is Lady Macbeth who proves haunted by the fallout of her choices. Middlemarch avoids, of course, the grand guignol of Macbeth in terms of bodily violence, but it is just as tightly focused on moral violence, and reputational violence, as Shakespeare’s play.

There’s another layer here, which has to do with the larger enframing assumptions different modes bring to a novel like Middlemarch. It is a mode of documentary verisimilitude, and it is an exemplary drama, a myth. Fruit imagery in this novel might be read ‘mythically’, via Biblical narratives of the fall of man, or Greek-mythological narratives (Atalanta’s golden apple, Sappho’s high-growing apple, Hesperidean treasure), or ‘scientifically’, as the mechanism by which trees make more trees, the vehicle of inheritance as such. The cultural—and, as we’ll see with other epigraphs and allusions, spiritual—inheritance of Middlemarch is located in a web of intertextuality.

1 Eliot, Middlemarch, ch. 6.

2 Karl Otfried Müller, History of the Literature of Ancient Greece, trans. by George Cornewall Lewis (London: n.p., 1840), 178–79.

3 See for instance, Meg M. Moring, ‘George Eliot’s Scrupulous Research: The Facts behind Eliot’s Use of the “Keepsake in Middlemarch”’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 26.1 (1993), 19–23 and Jerome Beaty, Middlemarch from Notebook to Novel: A Study of George Eliot’s Creative Method (Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1960).

4 Eliot, Middlemarch, ch. 24.

5 Ibid., ch. 40.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid., ch. 57.

8 Ibid., ‘Finale’.

9 William Shakespeare, Macbeth, I. 7. 73.