2. Writing Friendship: The Fraternal Travelogue and China-India Cultural Diplomacy in the 1950s

© 2022 Jia Yan, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0254.02

The decade after 1950, when the Republic of India became the first non-socialist country to establish diplomatic relations with the Communist-led People’s Republic of China, is famously remembered as the era of ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai’ (Indians and Chinese are brothers). Despite ideological differences and constant negotiations over unsettled geopolitical issues such as the demarcation of borders, the two emerging Asian states made significant efforts to collaborate under both bilateral and multilateral frames, with the shared intention of consolidating their newly-won independence and reshaping Cold War international orders.

Although relations between the two countries deteriorated in 1959 and came to a standstill after the 1962 border conflict, the 1950s deserve to be considered as more than a period of inflated political romanticism floundering on the hard rock of geopolitics. Rather, this decade provides a fertile field of study precisely for the numerous ‘friendship-building’ efforts that resulted in the emergence of unprecedented forms of political solidarity, opportunities to travel, spaces to meet, conduits of knowledge flows, and modes of textual transfer between China and India. Taking these moments seriously instead of focusing on the causes of conflict, as Arunabh Ghosh suggests, contributes to ‘decentering the teleology of 1962 and its overt emphasis on the evolution of Sino-Indian relations’.1 This approach also enables a deeper understanding of the conceptualization, workings, effects, and limits of Third World internationalism during the Cold War.

Focusing on the contacts between Chinese and Indian writers, this chapter offers a comparative analysis of the travelogues they produced in the context of China-India cultural diplomacy of the 1950s. While cultural diplomacy may be defined in general terms, its meanings, mechanisms, and effects, as scholars have shown, can in fact vary greatly from context to context, and the intentions behind it ‘depend very much on the cultural mindsets of the actors involved as well as the immediate organizational and structural circumstances’.2 In the case of VOKS, the USSR’s Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, cultural diplomacy was very much state propaganda despite its non-governmental disguise.3 By contrast, in the case of Nitobe Inazô and other early mediators of Japanese culture for foreign audiences, cultural diplomacy was largely an individual endeavour with no direct state involvement, part of their self-identification with ‘national culture’ and the obligation to promote it internationally.4 Most cultural diplomacy activities lie in the middle of this spectrum, with an unstable combination of the propagandistic and the personal. Therefore, my approach to studying China-India cultural diplomacy foregrounds specific configurations and practices on each side, rather than following a generalized model.

As we shall see, in the 1950s cultural diplomacy enabled an unprecedented series of frequent ‘writerly contacts’ between China and India.5 The establishment of different agencies of cultural diplomacy, such as friendship associations and national chapters of the World Peace Council (WPC), provided effective institutional frameworks within which Chinese and Indian writers could travel abroad, meet face-to-face, acquire first-hand knowledge of each other’s societies, exchange ideas and works, and build personal connections. The numerous travelogues constitute one of the most significant textual outcomes of these writerly contacts. Usually published right after a trip, these travelogues contributed to strengthening a sense of simultaneity and familiarity as well as shaping certain impressions of Chinese and Indian peoples. Due to the hybrid nature of cultural diplomacy, which combines cultural forms and diplomatic functions, these travelogues often fuse literary and political elements. They form a rich genre that shows a convergence and tension between the authors’ personal considerations and the state/party ideology they (were expected to) represent. My readings in this chapter underscore how the texts navigate between the two poles.

A few recent studies have used the genre of travelogue to challenge the rhetoric of ‘China-India friendship’. Tansen Sen questions the fraternal discourse by examining primarily travelogues written by anti-communist Indians who were critical of the Chinese way of ‘managing’ foreign visitors and of the PRC’s communist path in general.6 In her reading of the travelogue by the nationalist Hindi poet Ramdhari Singh ‘Dinkar’, Adhira Mangalagiri foregrounds the ‘ellipses’—‘the mark of silences, tensions, the unsaid’—in order to make visible ‘those literary ties that frustrate the logic and aims of cultural diplomacy’ and to decentre ‘“dialogue” as an easy metaphor for transnationalism’.7 These approaches reveal that travelogues facilitated by cultural diplomacy do not necessarily conform to state ideology, but at the same time they leave a large number of travelogues espousing the idea of ‘friendship’ out of sight, as if they were simply propaganda.

This chapter focuses on the genre of ‘fraternal travelogue’, which denotes travel writings produced with the aim of creating and disseminating transnational friendships. Instead of treating ‘friendship’ as a monolithic political slogan, I propose a critical understanding of it as a discursive amalgam that involved various strategies of expression and carried different significations, as my comparative reading of the similarities, differences, convergences, and tensions between the travelogues produced on both sides shows. As we shall see, while the idea of cultural diplomacy highlights mutuality, egalitarianism, and reciprocity, the different political cultures and national interests of China and India produced significant asymmetries in their cultural diplomacy. These asymmetries in turn produced noticeable contrasts in the fraternal travelogues written by Chinese and Indian writers, as the examples of Bingxin’s Chinese travel essay ‘Yindu Zhi Xing’ (A Journey to India) and Amrit Rai’s Hindi travel book Sūbah ke raṅg (Morning Colours) show.8 The fraternal travelogue, I argue, is a complex ‘form of ideology’ that fulfils propaganda functions while offering scope for self-reflection, silence, tension, and interrogation. One of its main features, which gives concrete shape and meaning to the somewhat hollow state ideology of enhancing ‘friendship’ and expresses the writers’ own political commitment, is its emphasis on chance encounters with ordinary people. For Bingxin, the fraternal travelogue is essentially an account of trips in which repeated chance encounters are deployed to present Indian people’s affinity with China as a spontaneous, ubiquitous, and therefore unchallengeable, ‘reality’. As for Rai, a card-carrying communist writer at the time, focusing on the ordinary people he encountered in China instead of state or communist party officials helped present his favourable comments on the PRC and harsh critique of India’s Congress regime as grounded in an objective evaluation of everyday experiences.

Asymmetries of China-India Cultural Diplomacy

China-India relations in the post-World-War-II period, like the general international order of the time, took place under the influence of the Cold War and the contest between the socialist and capitalist blocs. But whereas the PRC established a strategic alliance with the Soviet Union following the ‘Lean to One Side’ policy announced by Mao Zedong in June 1949,9 independent India under Jawaharlal Nehru adopted the path of Non-Alignment so as to avoid being entangled in the confrontation between the two superpowers while, at the same time, securing economic and political assistance from both.10 However, China and India also succeeded in finding common grounds for collaboration on the basis of their similar concerns and aspirations. Entering the 1950s as the two most populous countries in the world, their leaders realized that they needed to play a decisive role in post-war world affairs, instead of being swayed again by foreign powers. To this end, the two countries considered mutual friendship and support indispensable.

When Mao Zedong announced China’s alliance with the Soviet Union, he also proposed the ‘intermediate zone’ theory that complicated the Cold War division of the world into two blocs. Between the Soviet Union and the United States, Mao stated, there was an intermediate zone spanning Asia, Africa, and Europe, and ‘American imperialists’ would first attempt to encroach on these areas before waging war against the Soviet Union.11 ‘The international united front that communist China encouraged after 1949’, Mira Sinha Bhattacharjea contends, ‘had a single reference point at its core—anti-imperialism’.12 By situating China itself as part of the intermediate zone, Mao emphasized China’s solidarity with all the countries that had freed themselves from colonial rule or were still undergoing national liberation struggles. ‘As long as all these continued to be anticolonial and anti-imperialism even though not led by communist parties, they were regarded by Mao as being revolutionary in nature’.13 India thus gained a significant place in China’s international order thanks to its successful anticolonial struggle and the leading role Nehru was playing in the Third World. Mao’s ‘intermediate zone’ theory appealed to Nehru because it matched some of the key elements of the Non-Alignment framework, such as world peace and Asian solidarity. Moreover, Nehru had long considered China integral to his imagination of pan-Asianism, which was manifest in his moral support and practical assistance during China’s anti-Japanese struggle. The fact that India was the first non-socialist country to establish diplomatic ties with the PRC testifies to Nehru’s conviction about the need to befriend China.

Based on this mutual dependence, emphasized by the two leaders in the early 1950s, China and India ushered in a decade of frequent diplomatic exchanges, both formal and informal. By the time Nehru and the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai first exchanged diplomatic visits in 1954, various activities of cultural diplomacy had been underway between the two states for years, with a view to creating a favourable environment in the media and in the minds of the general public. Compared to the United States and the Soviet Union that deployed cultural agents and products to ‘win the minds of men’ in Europe and the Third World,14 the cultural diplomacy between China and India was arguably less competitive. However, despite the egalitarianism they claimed, the two countries carried out cultural diplomacy with one another in different ways, thus generating different results.

A major difference between China and India was in the relationship between the state and individuals. State involvement means that the exchange activities carried out by cultural agents are, to varying degrees, ‘in the service of the “national interest”, as defined by the government of the time’.15 What complicates a simple understanding of cultural diplomacy and differentiates it from inter-governmental diplomacy, however, is the fact that ‘the state cannot do much without the support of nongovernmental actors. […] The moment these actors enter, the desires, the lines of policy, the targets and the very definition of state interests become blurred and multiply’.16 Therefore, the state-individual relationship is central to my comparative investigation of the mechanisms, motives, strategies, agents, and effects of China-India cultural diplomacy.

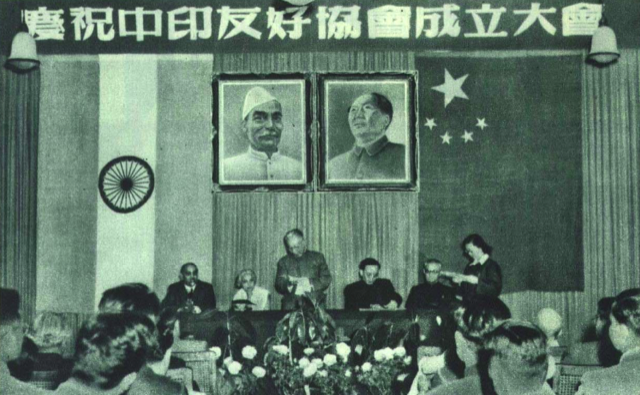

Throughout the 1950s, China-India cultural diplomacy operated at two different, yet overlapping, structural levels: the bilateral and the multilateral. At the bilateral level, the China-India Friendship Association (CIFA) and India-China Friendship Association (ICFA), two non-governmental organizations created in 1952 and 1953, ran a series of exchange programmes. They sent cultural delegations to visit the other country, organized receptions, meetings and sightseeing for visitors, helped popularize each other’s culture through exhibitions, cultural programmes, and film screenings, and attempted to favourably influence public opinion by inviting influential delegates who had returned from such visits to deliver public speeches and disseminate the sentiment of friendship to wider audiences.

Fig. 2.1 Assembly celebrating the founding of the CIFA, Beijing, May 16th, 1952. On the podium, from left to right: K.M. Panikkar, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Ding Xilin, Guo Moruo, and Zhang Xiruo. Photo by Renmin Huabao, public domain, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1952-06_1952%E5%B9%B45%E6%9C%8816%E6%97%A5%E4%B8%AD%E5%8D%B0%E5%8F%8B%E5%A5%BD%E5%8D%8F%E4%BC%9A%E6%88%90%E7%AB%8B.png

Despite the similar names and functions, CIFA and ICFA differed significantly in terms of administration and leadership. Though established to promote people-to-people contacts with India, the Chinese CIFA was sponsored by the state. From its inception CIFA remained a centralized, national association with no provincial branches and it worked efficiently in cooperation with the central government, national people’s organizations, and regional governments to form Chinese delegations to India, invite and receive Indian visitors, and organize India-related cultural activities.

In contrast to CIFA’s distinctively official makeup, the Indian ICFA remained a civil society organization with few formal links to the government of India or any political party. It developed from local branches set up by enthusiastic intellectuals before becoming a nationwide organization in December 1953. While the National Executive Committee of ICFA was responsible for organizing national conferences, passing resolutions, and devising plans, it was the local branches that organized specific activities.17 The unofficial and voluntary nature of ICFA helped it grow and expand and turn it quickly into a widespread movement joined by people from all over the country. By February 1958, ICFA was reported to have eighteen state or regional branches and as many as 140 district and primary branches.18

At the multilateral level, the main arena for China-India cultural diplomacy in the 1950s was the World Peace Council (WPC), founded in 1950 under the auspices of the Soviet-dominated Communist Information Bureau (Cominform). The Soviet-backed WPC and the US-backed Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF, see Zecchini in this volume) served as the cultural ‘fronts’ for the two Cold War superpowers, propagating ‘peace’ and ‘freedom’ as competing codes that respectively implied a pro-Soviet and pro-US position.19 In spite of its conspicuous association with the Soviet Union, the WPC appealed to both communists and non-communists, partly because the Cominform hoped to make it as ‘extensive’ as possible, and partly because pacifists around the world, who had witnessed the tragedies caused by fascism and were now worried about a potential nuclear war waged by the United States, identified with the concept of ‘peace’.20 The WPC promoted intercultural exchange by organizing delegation visits and cultural festivals, and it projected itself as preserver of world culture and humanity by commemorating ‘Noted Figures of World Culture’ and awarding the ‘International Peace Prize’ to intellectuals who made a particular contribution to the movement.

National chapters of the World Peace Movement—the Chinese People’s Committee for Defending World Peace (CPCDWP) and the All-India Peace Committee (AIPC)—were established in China and India in 1949. The PRC wholeheartedly embraced the Soviet-dominated peace movement not only because it was in line with Mao’s ‘Lean to One Side’ policy, but also because the new government regarded it as a platform that would allow China to broaden its external relations and gain international recognition. The fact that the CPCDWP was founded on 2 October 1949—the day after the PRC was born—testifies to the country’s keenness in joining the movement.

Unlike China, the World Peace Movement in India began with a dilemma. Since the movement was under the leadership of the Cominform, the mandate to create an Indian chapter initially went to the Communist Party of India (CPI).21 However, the movement did not receive much support from the CPI. Although the communist-dominated All-India Trade Union Congress convened the first All-India Congress for Peace and set up the AIPC in November 1949, the CPI did little to advance the movement in the next two years since its own radical, anti-bourgeois strategy contradicted the Cominform’s call to broaden the movement by bringing together all possible forces.22 With little backing from the CPI, the peace movement in India also faced obstacles from the Congress government. As the CPI had been waging a class war against the ‘bourgeois’ Congress since 1949, relations between the two parties were deteriorating dramatically. Aware of the movement’s intrinsic (though weak) connection with the communists, the Congress government took a hostile attitude: not only did it refuse passports to the Indian delegates who were to attend the 1949 Peace Congress in Paris, it also thwarted the AIPC’s attempt to host a gathering in Delhi.23 The hostility continued after the CPI party line became more moderate in 1951. While Nehru’s attitude towards the communists may have changed, at the provincial level relations remained strained because Congress leaders at the regional state level were mostly conservative.24 Communists continued to encounter problems when applying for passports to visit China and sometimes had to approach the central government for a solution (as Amrit Rai did).

In the face of the peace movement’s predicament in India, a group of influential leftist intellectuals, including Mulk Raj Anand, R. K. Karanjia, K. A. Abbas and Krishan Chander, were elected leaders of the AIPC Bombay branch in October 1950, and they proved to be more committed to the movement than their communist predecessors.25 Meanwhile, the CPI’s apathy continued in spite of the change in the party line, so that very few CPI members were part of the AIPC leadership or of Indian delegations to WPC conferences abroad throughout the 1950s.26 While US observers claimed that in India ‘the peace movement has proved to be an effective device with which the Communists can gain influence among the non-Communist intelligentsia and the middle-class in general’,27 it was in fact mainly driven by non-communist leftist intellectuals. Apart from Anand, Karanjia, Abbas, and Chander, other non-communist leftist writers closely associated with the peace movement included the English poet and independent Member of Parliament Harindranath Chattopadhyay, the Malayalam poet Vallathol, the Punjabi novelist Gurbaksh Singh, and ICFA president Pandit Sundarlal.

Writerly Contact and the Travelogue

Thanks to these bilateral and multilateral frames of cultural diplomacy, in the 1950s writerly contacts between independent China and India greatly increased in volume and closeness compared to the first half of the century. After Tagore’s sensational visit to China in 1924, over the next two decades encounters between Chinese writers and Indian writers were rare and mostly took place in the European metropoles.28 It was in wartime London, for instance, at Bloomsbury gatherings and PEN International conferences, that the Indian English writer Mulk Raj Anand became acquainted with Ye Junjian and Xiao Qian, two Chinese writers who had gone to England as journalists to enhance the anti-fascist alliance between Britain and China. Underlying their friendship was a shared aspiration to make the oppressed voices of China and India heard in the West by writing in English and participating in England’s literary life, albeit from a marginalized position.29 By contrast, post-1950 at least forty Chinese and Indian writers travelled between the two nations and met to discuss the burning issues of the 1950s, such as cultural reconstruction and nation-building, peaceful coexistence, Asian solidarity, and the global Cold War. Nor did they need to be affiliated to literary organizations in Europe in order to speak to an international audience. Although they continued to meet in European cities (especially under the aegis of the WPC), these cities were supplementary rather than primary sites of contact.

Fig. 2.2 Guo Moruo (middle) seeing off Anand (left), Sundarlal (right) and other Indian delegates of the 1951 mission at the airport. Source: Pandit Sundarlal, China Today (1952).

The variety of positions on the ideological spectrum is noteworthy on both sides. The Chinese writers selected to participate in India-oriented cultural diplomacy comprised both communists and non-communists who adhered to the party line on art and literature. The fact that non-communist writers such as Ding Xilin (the ICFA president), Zheng Zhenduo (the leader of the 1954–1955 cultural delegation to India) and Bingxin (who visited India twice) were given such prominent roles suggests that the PRC government wanted to showcase an ideologically diversified image in its cultural diplomacy with India.

On the Indian side, non-communist leftists and Gandhians were more present and played a more decisive role than the communists. Leftist writers like Anand and Abbas, who had been strongly involved in CPI-backed progressive cultural organizations such as the All-India Progressive Writers’ Association and the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) under the moderate party line of CPI Secretary P. C. Joshi, were expelled in the late 1940s.30 Their engagement with ICFA and the peace movement in the early 1950s can therefore be understood as an attempt to seek an alternative path for their leftist activism on an international level. Equally noticeable is the participation of Gandhians like Pandit Sundarlal, the leader of the 1951 Indian goodwill mission. As Herbert Passin points out, though Gandhians considered the Chinese revolution a contradiction to Gandhi’s non-violent creed, they regarded it as ‘something of the past’ and were instead attracted by ‘Chinese “communitarianism”, mass persuasion techniques, and puritanical morality’.31 They even attempted to make Gandhism a new template for India-China fraternity, in addition to the prevalent discourses of old civilizational bonds and anti-imperialism. Interviewed by Guo Moruo in Beijing, Sundarlal claimed that ‘if some of the angularities could be removed’, the teachings of Gandhi and Marx ‘could become supplementary to each other and could even become one’.32

As already mentioned, few Indian communists, including communist writers, took part in China-India cultural exchanges in the 1950s. Although frequently labelled ‘communist fronts’ in non/anti-communist discourse, the ICFA and the AIPC were only loosely connected to the CPI and there is no evidence that they had direct links to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In fact, direct relations between the CPI and the CCP were limited throughout the 1950s, either as cultural or formal diplomacy. Although the revolutionary movements in India proclaimed themselves to be ‘Maoist’, the CCP exerted no direct influence on them and in fact ‘maintained a policy of studied non-involvement in Indian communism all through the 1950s’ because it accepted the Soviet Union’s direct supervision of the Indian communist movement.33 Indeed, since CCP leaders were likely aware of the CPI-Congress tensions, they may have wanted to prevent state-to-state friendship from being undermined by inter-communist party interactions. A few Indian communists such as Amrit Rai did visit China, but they were mainly selected because of their active engagement in the peace movement or their friendly attitudes towards China rather than any prominent role in the CPI.

The frequent writerly contacts prompted by China-India cultural diplomacy gave rise to various kinds of textual production, such as translations, travelogues, and reportages. In some cases, writerly contacts converted directly into textual contacts, as when Bingxin translated Anand’s anthology Indian Fairy Tales (1946) in 1955 and Li Shui translated Jainendra Kumar’s Hindi novella Tyāg-patra (The Resignation, 1937) in 1959.34 But such cases were unusual because they required not only a high degree of mutual interest but also for the writers in the host culture to be qualified translators (like Bingxin and Li Shui) and for the original works to be available in a language that they knew. This is especially relevant in Li Shui’s case, for his translation would not have been possible had Tyāg-patra not been already translated into English by Sachchidananda Hirananda Vatsyayan ‘Agyeya’ in 1946. On the Indian side, I have been unable to trace any visitor to the PRC in the 1950s who translated the works of the Chinese writers they met.35 Most of the translations of Chinese literature circulating in 1950s India were English versions produced either by the Foreign Languages Press in Beijing or by Western translators, or re-translations of these English versions into Indian languages.36

Compared with the literary translations, the travelogues that emerged from China-India cultural diplomacy are greater in number. And not only did they originate from the cultural interactions between the two countries, they were also directly about these interactions. Unlike press reports, which mostly offer bare summaries of major activities and are often laden with official rhetoric, the travelogues usually blend formal and informal voices and therefore can bring into view the authors’ negotiation between their individual interests and the ‘national interests’, thanks to the intrinsically ambivalent nature of travelogue as a literary genre. Three features distinguish the genre, according to Carl Thompson: a pronounced first-person account of the journey, the author’s sensibility and style, and an ostensibly non-fictional narrative of what really happened.37 Travelogues are therefore simultaneously informative and emotional, objective and subjective. This ambivalence gives the form both epistemological depth and affective weight.

What makes the travelogue a particularly good carrier of ideology in the context of cultural diplomacy is the authority engendered by the sense of ‘being there’ and ‘witnessing’ not just reality but also history. This authority was particularly significant in the 1950s because back then travel between China and India was very much a privilege enjoyed only by few. The claim to objectivity was particularly conspicuous among Indian writers, who tended to insert a marker of truthfulness in the titles of their travelogues, such as Rahul Sankrityayan’s Chīn men kyā dekhā (What I Saw in China, 1960) or Raja Hutheesing’s The Great Peace: An Asian’s Candid Report on Red China (1953). Considering the conflicting views regarding the PRC and communism in India’s public sphere during the 1950s, these truth claims helped to project a travel account as the authentic version, making it appear attractive and persuasive to the readership.

If ‘friendship’ indeed served as a prominent ideological link between post-1950 China and India, what did it exactly mean to Chinese and Indian writers who visited each other’s country? How were their perspectives, impressions, and representations affected by the ideological and organizational asymmetries of China-India cultural diplomacy? What strategies or techniques did these travelogues adopt to foster a particular sense of friendship? In the following pages, I attempt to answer these questions by examining a number of fraternal travelogues, particularly those written by Bingxin and Amrit Rai.

Bingxin’s ‘Yindu Zhi Xing’

For the PRC, which in the early 1950s was still seeking international recognition, the purpose of cultural diplomacy was to promote its new image as an independent, sovereign, and progressive state. Thus, whether facing inward or outward, cultural diplomacy for the PRC featured a strong element of self-presentation. The state considered official involvement to be necessary in order to ensure that its ‘cultural ambassadors’ presented the nation’s image properly. To take the first unofficial Chinese cultural delegation to India in September 1951 as an example, Premier Zhou Enlai is said to have scrutinized the list of delegates himself, and before they left for India, delegates were asked to gather in Beijing for a short course that included the history of the Communist Party of China, the current situation in Asia, and China’s Asian policy, so that they would have the requisite political awareness and knowledge to communicate ‘appropriately’ with their Indian hosts.38

Chinese policymakers were fully aware that, if mismanaged, the ideological discrepancy between China and India could endanger the success of bilateral cultural exchange. One key strategy to avoid conflict was to distance the Chinese delegates from any explicit political agenda that might be deemed provocative by the Indian authorities. The novelist Zhou Erfu, who co-led an official Chinese cultural delegation to India in late 1954, recollected that when the delegates were preparing cultural programmes for Indian audiences, Zhou Enlai emphasized that, ‘The selection of programmes […] should express Chinese people’s wish for peace rather than impose on [the audience] programmes that are charged with strong political overtones. Improving cultural exchanges and friendly interactions between Chinese and Indian […] governments and peoples is itself politics’.39

Nonetheless, the PRC’s cultural diplomacy targeting India in the 1950s was far from monolithic, because ‘cultural exchanges’ and ‘friendly interactions’ took quite different forms in different fields. Dance diplomacy, for instance, emphasized mutual learning, and its primary goal was to learn from, rather than export to, India. As Emily Wilcox argues, it was mainly the sweat and pain that Chinese dancers endured while practising Bharatanatyam moves that made their bodies representative of ‘the dedication [that] China as a nation espoused toward ideals such as working together, valuing diverse Asian cultural traditions, and learning from one another’.40 Sino-Indian exchanges in the field of statistics, according to Arunabh Ghosh, also highlighted ‘learning from each other’s experiences’, but differed from dance diplomacy in the pragmatic expectation of outcomes rather than emphasizing the learning process. In statistics the PRC’s aim was to learn about India’s cutting-edge methods of random sampling in order solve its social problems.41

Chinese writers’ contacts with India, by contrast, emphasized the idea of learning about, rather than learning from, India. While responsible for presenting a positive image of the PRC in India, Chinese writers were also required to bring back home a positive image of India. This meant depicting India as a promising country, and Indian people as true friends of the Chinese people. To this end, travelogues proved to be more effective than reportages, literary translations, and fictional writings.

Reading through Chinese travelogues about India published in the 1950s, one immediately notices their homogeneity in terms of both what and how they reported about India. Most Chinese writers emphasized India’s rich cultural heritage, whereas comments (not to mention criticism) about the country’s present social problems and political system are barely visible.42 It is generally through their experiences of local cultural attractions or artistic performances that any discussion of the relevant aspects of Indian society or history emerge. This is evident in ‘Yindu Zhi Xing’ (A Journey to India, hereinafter ‘Yindu’), a long travel essay by the non-communist writer Bingxin published after her 1953 India trip with a CIFA delegation.

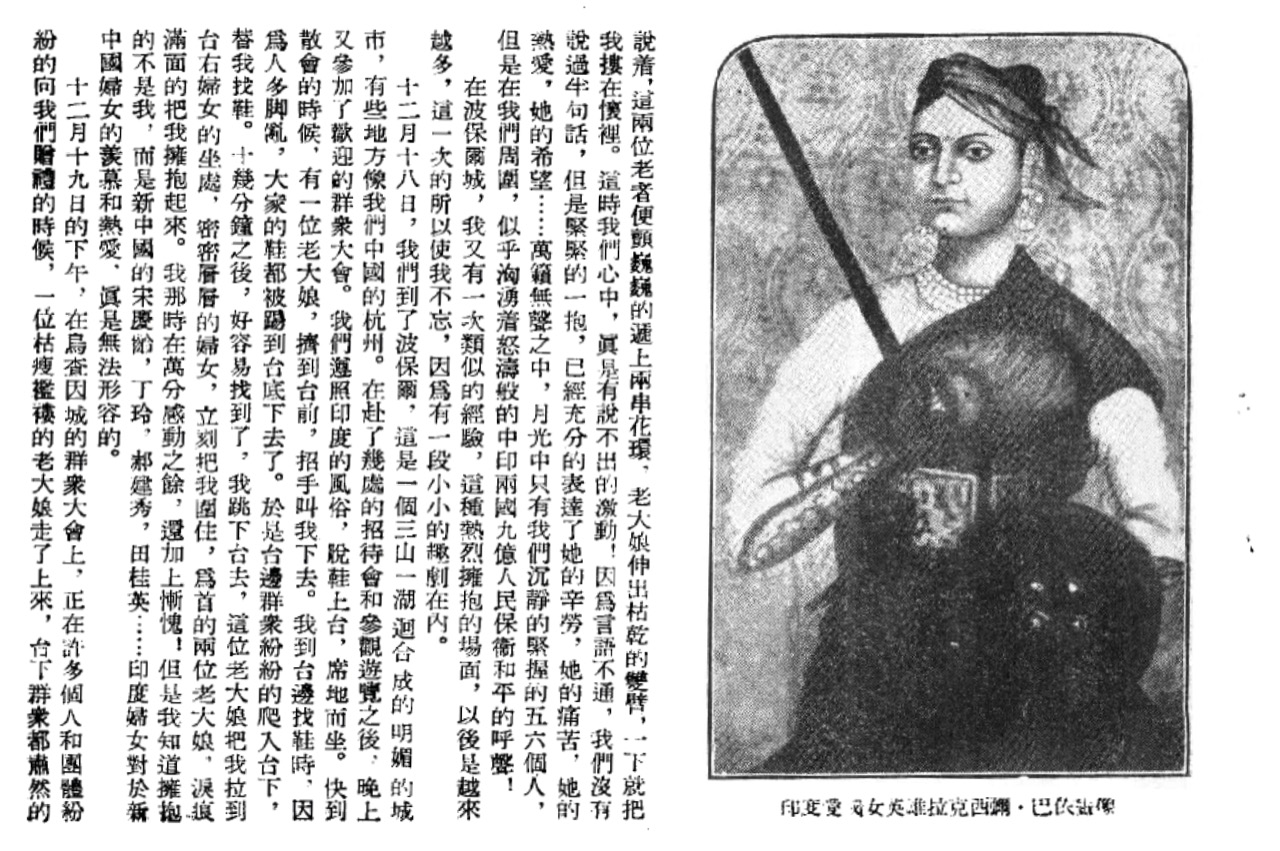

In general, Bingxin provides the reader with knowledge about India in the manner of a tourist, echoing the delegation’s sightseeing led by local guides. Given that, beside formal exchange activities, most of the places they visited were heritage sites, and the India they perceived and articulated was inevitably confined to the past. In ‘Yindu’, the magnificence of the Jama Masjid in Delhi and the Taj Mahal in Agra segues into an introduction to emperor Shah Jahan and Mughal history; her appreciation of Bharatanatyam dance is followed by a paragraph on Hindu deities and mythology; a visit to the tomb of Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi, provokes a reflection on the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the origin of Indian nationalism; and a tribute to the site of the old university of Nalanda immediately turns into a nostalgic account of ancient Buddhist pilgrims like Xuanzang and the long history of China-India cultural exchanges.43

Fig. 2.3 A page from ‘Yindu Zhi Xing’ depicting a visit to the tomb of Lakshmibai, with a picture attached. Source: Bingxin, ‘Yindu Zhi Xing’ (part two), Xin Guancha, 11 (1954), p. 12.

Bingxin’s account shows the PRC’s ambivalent treatment of Buddhism as a resource for cross-cultural interactions. While Buddhism continued to be a symbol of China-India cultural intercourse from 1949, it seldom figured prominently in the interactions between writers.44 For Bingxin

and other writers of socialist China, Xuanzang’s days were not a ‘golden age’ to return to, but a past that was limited in scope and needed to be transcended for a greater cause. Comparing post-war cultural exchanges between China and India with Xuanzang and his Indian teacher Silabhadra, Bingxin wrote: ‘Our goals are higher than theirs because we are striving together not only for the Buddhists in the two countries, but for the sustainable peace of Asia and the entire world’.45 Although Buddhism was invoked to suggest a history of friendly contacts and held symbolic and ideological overtones, new, broader and more relevant templates—in this case, the World Peace Movement—were to carry the China-India interchange forward.

Indeed, almost all the Chinese travelogues about India published in the 1950s contain messages of ‘friendship’ and evidence of the ‘success’ of cultural diplomacy. If the slogan ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai’ is utopian, travelogues offer eyewitness accounts of that utopia realized. China-India friendship in travelogues is embodied in numerous ‘moments of encounter’, in which a visiting writer first mingles with a local crowd. Such moments usually took place at transport hubs like airports, railway stations, and ports, or in public places like squares and conference halls. The depiction of these encounters is always detailed and emotive. Bingxin, for instance, recounts more than ten such encountering moments in ‘Yindu’. In her depictions of formal receptions and mass rallies, the host’s acts of presenting garlands, bouquets and gifts feature extensively as tropes that epitomize goodwill. These symbolic items are sometimes hyperbolized to impress readers: ‘We received more than three thousand garlands… which weighed over four hundred kilograms and would form a line of four kilometres if connected end-to-end’.46

Fig. 2.4 Bingxin and Ding Xilin (second and third left on the table) receiving garlands from Indian hosts. Source: Bingxin, ‘Yindu Zhi Xing’ (part two), Xin Guancha, 11 (1954), p. 14.

Yet it is Bingxin’s depiction of unexpected moments of encounter that really makes her friendship narrative affective. Recounting a train journey in Andhra Pradesh, Bingxin describes a ‘passionate picture’ of her encounter with a group of peasants who look distinctly communist:

The train stopped, as it stopped when passing other small stations. Someone knocked on the door. When the door was opened and we looked down, several flaming torches showed up, clustering around a red flag. Illuminated by the glittering flare were scores of excited and unadorned faces. The one who was holding the flag was a thin and small woman, under whose leadership a contingent of peasants dressed in tattered clothes gathered. They shouted welcoming words and the slogan ‘Long Live Comrade Mao Zedong’, with their eyes filled with tears of delight, zeal and pride. As we embraced, I could smell the pleasing odour of the sun and dust on her worn-out clothes. She was everything about the Indian people and earth. I have held ‘Mother India’ tightly in my arms!47

The scene is replete with sensory touches. The burning flare, red flag, and political slogan typical of the socialist symbolism of comradeship reinforce the joy, excitement, and pride in their tears, making this ephemeral encounter emotionally intense. The emphasis on the simplicity of the peasants’ dresses serves the narrative function of expressing the purity and authenticity of their emotional response. The embrace is at once real and symbolic. By romanticizing the female peasant and blurring her identity with that of the nation—‘Mother India’—Bingxin presents the embrace of two individuals as an allegory of the mutual affection between the Chinese and Indian peoples.48 The unpredictability of the Indian woman’s appearance along with her fellow peasants at the station strengthens the suggestion that she represents the ‘Indian people’.

In ‘Yindu’, both formal and unexpected encounters appear repeatedly. Bingxin seems to deploy them as narrative devices that constantly remind the reader that China-India friendship is something that can be, and in fact has been, felt time and again in real life. Here, the structure of Bingxin’s travel narrative, which follows the chronological order of her itinerary rather than a thematic arrangement, seems deliberate. It creates the opportunity to introduce such moments of encounter at every change of place. The continuous representation of India-China friendship in this case is largely (re)produced by the writer’s own mobility. Notably, Binxin’s moments of encounter do not entail a mechanical iteration of the same content. Rather, the story and object depicted alter from one place to another, though characteristic motifs like garlands, gifts, and embraces regularly recur. For example, while the scene above centres on Indian peasants, Binxin later depicts encounters with a group of Dalits in Vanukuru village near Vijayawada, two women in Bhopal, and an old couple in Calcutta who each represent a different Indian social group—Dalits, women, and the elderly. In this way, India’s affinity with Chinese people is represented as a ubiquitous phenomenon across different geographies, classes, genders, and ages.

Amrit Rai’s Sūbah ke raṅg

Compared to the Chinese delegations discussed above, India’s direct governmental intervention in its cultural diplomacy with China was rather more limited, it seems. Most Indian delegations to China, like the 1951 goodwill mission, were unofficial, with few participants holding bureaucratic posts. Pandit Sundarlal stresses in his travelogue that the delegation he headed was ‘neither sponsored by nor representing the Government of India’. According to him, the government was involved only in providing passports and other facilities.49 There is no evidence showing that Nehru summoned the delegation before it left, as Zhou Enlai did.

The absence of an official agenda and guidelines allowed the motives, expectations, and outlooks of the individual delegates to surface more freely. Diverse and sometimes contrasting voices are clearly reflected in the China travelogues by Indian writers, whose perspectives were largely dictated by their respective ideologies. On the one hand, there are travelogues written by anti-communist intellectuals such as Raja Hutheesing and Frank Moraes, who wrote in negative terms about almost everything they saw in the PRC. They criticized the ‘totalitarian’ control by the communist state over the Chinese people, and interpreted the PRC’s promotion of peace and friendship as an ‘imperialist’ scheme that threatened India and other Asian countries.50 On the other hand, most China travelogues were produced by pro-China intellectuals like Pandit Sundarlal, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, R. K. Karanjia, and Amrit Rai, who were key members of the ICFA or the All-India Peace Committee. Their travelogues are full of favourable comments on the PRC’s accomplishments in various spheres, such as social dynamism, the equality of classes and genders, industrialization, agrarian reform, judicial system, mass literacy, and cultural rejuvenation. Compared with Bingxin’s travel essay, the Indian travelogues pay much more attention to the contemporary socio-political context, and many were published in book form rather than as newspaper or magazine articles. Instead of following a chronological order, they were mostly arranged thematically, with each chapter covering a particular aspect of the ‘new China’, be it ‘song and dance’ or ‘manufacturing workers’. This more systematic approach reveals a deep curiosity about what the Chinese revolution had achieved, and this curiosity, as discussed below, derived partly from a dissatisfaction with India’s status quo. Even the writer who produced the most negative account of the PRC admitted before the visit that ‘China seemed to offer a new way by which the Asian people could acquire the means of improving their lot’.51

In his analysis of Sundarlal’s China Today (1952), Abbas’s China Can Make It (1952) and Karanjia’s China Stands Up (1952), three works in English by pro-Chinese yet non-communist authors that are representative of what I call the ‘fraternal travelogue’, Brian Tsui has highlighted their different strategies to make the Chinese revolution ‘comprehensible in light of the Indian elite’s own priorities as nation builders and social activists’.52 Sundarlal’s strategy was to ‘mobilize terms central to the Congress-led anticolonial movement’ (e.g. by calling the handwoven cloth sold in Beijing khadi) and to ‘emphasize similarities between China and India’ by highlighting the compatibility between Gandhian and Marxist thought, as discussed above.53 Abbas focused primarily on industrial improvement and praised the PRC’s achievements on ‘criteria with which postcolonial societies would readily identify’, such as economic self-sufficiency.54 Adopting the genre of ‘popular history’, Karanjia situated his experiences of China in the ‘longue durée’ of Asia’s subjugation to Euro-American powers, producing a sense of shared anticolonial solidarity.55 In spite of their differences, these travelogues acted as bridges between communist China and postcolonial India and enhanced the fraternal perception of the PRC within India.

To push Tsui’s argument further, I now turn to Amrit Rai’s 1953 Hindi travelogue Sūbah ke raṅg (Morning Colours, hereinafter Sūbah) to explore how an Indian communist writer reported on communist China. What opportunities and challenges did ideological affinity create? How did it affect the perspective, content, language, and narration of these travelogues? Did ‘China-India friendship’ carry different meanings and politics for an Indian communist author, compared with non-communist authors? Answering these questions will help us gain a deeper understanding of the fraternal travelogue as a nuanced form of ideology.

Amrit Rai wrote Sūbah after visiting China in October 1952, where he attended the Asian and Pacific Rim Peace Conference in Beijing before travelling briefly to other places like Shenzhen, Nanjing, and Hangzhou.56 Published by Rai’s own Hans Prakashan in Allahabad in a substantial first edition of 2,000 copies, the book received positive reviews in the Progressive monthly Nayā Path (New Path).57 The travelogue is book-ended by chronological chapters that loosely follow the timeline of Rai’s travel, but the fourteen middle chapters are thematic, with titles like ‘Woman’s Rebirth’ and ‘Culture is a People’s Matter’. This structure allows Rai to present his travel as both a journey and a survey, balanced between anecdotes and commentary. Like Bingxin’s ‘Yindu’, Sūbah is rich in friendship symbolism, including welcoming crowds, flowers, handshakes, smiles, and songs, but Rai does not emphasize spectacle through emotional language and sensory details. His attempt to foster a sense of brotherhood with communist China in his Indian readers relies more on arriving at a correct understanding of the country than on immortalizing moments of friendship.

That Rai’s observations about China are utterly favourable in every chapter comes as no surprise. But the questions to ask are not how or why Rai praised the PRC, but how he rendered his praise credible and convincing to his readers. Comparing his book to the ‘big picture’ of systematic socio-economic progress, with the aid of statistics and maps in Sundarlal and Karanjia’s travelogues Rai told his readers:

You will not find any of these in this little book. Its scope is very small. I tried to understand the new rhythm and melody in the life of China only through the ordinary men and women with whom I came into contact. Telling the story from this point of view was necessary because it was these ordinary men and women who struggled for the people’s revolution and who are now dedicated to rebuilding their ruined country. They are the creators of the new China.58

Rai presented his travelogue as written from the perspective of ordinary people rather than the state, and his focus was primarily on the everyday. Such a choice stemmed not only from his progressivist aesthetics, but may have also been a deliberate attempt to make his travelogue more relatable to readers. He also presented himself as an ‘ordinary Indian citizen’ rather than a committed communist: ‘In this little book created out of my memories’, he wrote in the preface, ‘I will only talk about the anecdotes concerning the ordinary people that have left a mark on my mind. And my mind is that of an ordinary Indian citizen, whose sole claim is love for his own country’.59 In this light, readers were asked to interpret Rai’s many unfavourable comparisons between India and the PRC as patriotic, not partisan.

By crediting ordinary people for the success of the Chinese revolution and nation-building, Rai framed his appreciation of the accomplishments of the PRC as a recognition of their contribution rather than a tribute to communist party leadership. In fact, Rai’s travelogue seldom comments directly on the Chinese communist party but rather refers to it figuratively. The most recurring trope is that of ‘morning colours’, which also appears in the book’s title. ‘If the glow of the new morning’, Rai writes, ‘has made today’s Chinese life bright, it is only because this new morning is true. It is impossible for one not to see its gleam and colours’.60 The ‘new morning’ stands unequivocally for the communist regime, and its ‘gleam and colours’ for the regime’s policies and achievements. Yet by couching his tribute in figurative terms, Rai goes some way toward presenting his arguments as non-party political.

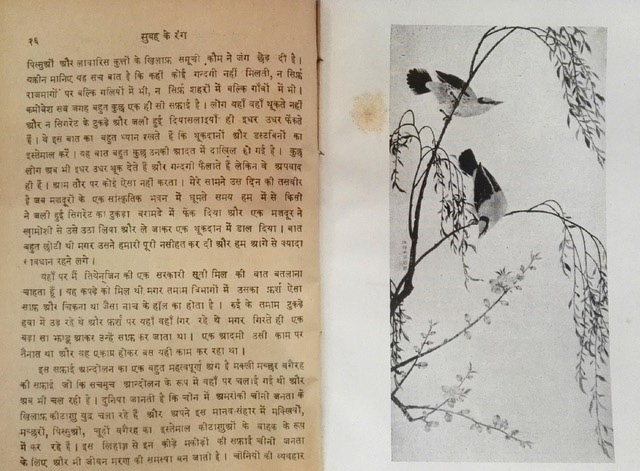

Sūbah is characterized by meticulous argumentation. Unlike most pro-Chinese authors, who often jumped quickly to conclusions, Rai works more slowly towards predictably positive assessments, adding a lot of argumentative detail and anecdotal evidence in the process. Whatever particular topic relating to Chinese society he discusses, he always begins with a paradox or a question. In the chapter entitled ‘Where We Set Foot on the Land of New China’, for instance, he first posits the ‘miraculous’ cleanliness of Chinese cities and villages is ‘unbelievable’ because ‘it is of such a high degree that we can hardly associate it with a backward, ignorant, predominantly agricultural, and semi-colonial country’.61 Riding on the popular expectation among the general Indian public that ‘China must have been more backward than India’, he asks: ‘How did it become possible that such a backward country became so clean and cleanliness-loving overnight?’62 A four-page explanation that includes a discussion of how Chinese people regarded keeping the nation clean as a personal responsibility, three ‘small anecdotes’ depicting workers and villagers who uphold hygiene in their neighbourhood and a comparison with ‘Western democracies’ and India finally lead to the argument that ‘This miracle was realised only because hundreds of millions of people are behind it’.63 While depicting a visit to a village near Beijing, Rai does not conceal his laughter when the village headman reported the number of flies killed by the villagers (a nationwide campaign launched by the communist party in the 1950s). But he soon turns this vignette into a mind-changing event that helps him appreciate the extraordinary popular mobilization and participation in the PRC’s social movements:

I have to admit that at the beginning this sounded funny to me. But after a deeper thought I found it not laughable but remarkable. Obviously, the village head had not made the number up in his imagination. No matter how many flies people killed, they must have kept a record accordingly and reported regularly to the head. This is how statistics were gathered. Just think, developing such a serious political interest in people for matters like killing flies and mosquitoes can’t have been a joke.64

Rai’s attention to detail and practice, and his question here, are anthropological, and his language is often dialogic and reflective. He constantly pauses in the midst of a narration and invites the readers to think along with him. This observational and reflexive style produced an apparently objective account, which in fact aided his political aim of enhancing a sympathetic understanding of communist China among readers. This may explain why travelogues written by communist writers like Rai lack the ‘extravagant language and full-throated paean’ visible in some of those written by non-communist leftists like Karanjia.65

Fig. 2.5 Two pages from Sūbah ke raṅg: the left page discusses cleanliness in the PRC, the right reproduces a traditional Chinese painting depicting natural harmony. Source: Amrit Rai, Sūbah ke rang. © Alok Rai. All rights reserved.

Amrit Rai’s appreciation of the PRC’s achievements in Sūbah ke raṅg often appears alongside a dismal appraisal of conditions in India. That India should learn from China in terms of self-dependency, poverty elimination, mass education, gender equality, and cultural reconstruction comes across clearly in the travelogue. For example, in the chapter ‘Culture is a thing of the People’ (Saṃskriti jantā kī chīz hai) Rai compares the film industries of the two countries. In Rai’s view, the many films he saw during his tour in China, which portray the struggle of ordinary people for self-emancipation and national liberation, inspire one to pursue higher, more patriotic and humanitarian causes. On the contrary, ‘the explicit pictures in the name of entertainment’ produced in Mumbai—according to Rai under the influence of Hollywood—though technologically more advanced, ‘can only draw us towards degradation’ rather than generate the ‘vigour’ of Chinese films.66 Rai further turns the state regulation over cultural matters in the PRC into a critique of Congress governance: ‘This situation will not be corrected unless our government takes it in hand. But at present, far from taking the industry in hand, the government does not even want to do anything to set right these tendencies.’67

Rai’s negative appraisal of the Congress establishment becomes vehement when it comes to his position as a communist. In a chapter entitled ‘Iron Curtain and Bamboo Fences’ (Lohe ke parde aur bāṃs kī ṭaṭṭiyān), Rai responded to the labels that Indian anti-communists often affixed to the Soviet Union and the PRC. He did not challenge their legitimacy, but posited the existence of a ‘Khadi Curtain’ that conservative Congressmen had erected to suppress communism in India. As proof he recounted how the district Congress authority had turned down his passport application to visit Beijing without good reason, just as they had formerly denied his application to go to Moscow. When Rai filed a complaint with the central government, he was considered ‘not so dangerous’ and eventually issued a passport.68 Elsewhere in the travelogue Rai attacked the ‘Congress Raj’ for paying more attention to policing than to education and for jailing dissidents—Rai himself had been briefly imprisoned for his vocal criticism of the government suppression of the 1948 CPI-led peasant struggles.69 Although, as we have seen, the CPC had no ties with these struggles and remained detached from the Indian communist movement in the 1950s, Rai’s writings stress a kind of communist solidarity between Indian and China that operated mostly at the conceptual and affective levels.

Conclusions

Out of shared needs for nation-building and international engagement, post-war China-India cultural diplomacy brought Chinese and Indian writers together on various new platforms. As politically sensitive, socially responsible, and publicly influential intellectuals, these writers navigated national and personal interests and enacted multiple roles—as writers, travellers, representatives of their newly-minted national cultures, observers of one another’s societal conditions, and commentators of China-India fraternity. These multiple roles meant that the writerly contacts facilitated by cultural diplomacy seldom focused on literature alone. This also holds true for other forms of cultural Cold War, whether the Asian/Afro-Asian writers’ conferences or those organized by the International Congress for Cultural Freedom.

Ideally, China-India cultural diplomacy was marked by reciprocity, egalitarianism, and peaceful coexistence (as per the 1954 Panchsheel Treaty), but this does not mean that cultural exchanges or mutual perceptions mirrored each other. The different political systems and cultural agendas produced stark contrasts and asymmetries, which become particularly visible through the lens of the fraternal travelogue. While state intervention pressed upon Chinese authors travelling to India the duty to present a positive image of their new nation, and they wrote almost unanimously about the hospitality and respect they received from Indian people, the more limited involvement of the government allowed Indian visitors to observe and present the PRC from a variety of angles. Their often very contrasting impressions and evaluations suggest that the China tour often worked to confirm their predetermined ideological stance, whether pro- or anti-communist.

Even within the form of the fraternal travelogue, ‘friendship’ was configured and articulated in different ways. Those written by Chinese writers like Bingxin combined a history-based understanding of India with passionate depictions of rapturous encounters, thus moulding a relationship that was at once temporally distanced and emotionally intimate. This configuration projected China-India friendship as everlasting and Indians as an amiable people without necessarily engaging with comparative evaluations of contemporary China and India and their systems. Although the knowledge about India produced by these travelogues was inevitably bound to the past, it nevertheless came across as accurate and enriching.

The fraternal travelogues written by Indian writers, by contrast, focused predominantly on current conditions within the PRC and their immediate relevance to India. Friendship here was configured as a bridge across the ideological and systemic gap between post-revolution China and post-colonial India, refiguring the ideological and social differences between the two as opportunities for self-reflection and self-reform rather than as geopolitical threats. By adopting a non-statist, non-party political perspective as well as nuanced narrative strategies, communist writers like Amrit Rai produced a positive image of the PRC and, more importantly, a convincing explanation of why this image mattered. For these writers, the fraternal travelogue about China served, implicitly, as a manifesto of their faith in the communist ideology.

That both Bingxin and Rai put ordinary people as the centre of their fraternal travelogues challenges the portrayal of ‘China-India friendship’ as simply a rhetoric of the Chinese and Indian governments. This makes us think of ‘Asian solidarity’ not as a statist model but as an unfinished project formed by multiple relation-building processes. In this sense, this study of the fraternal travelogues contributes to China-India scholarship studies by suggesting we don’t go beyond the ‘bhai-bhai’ rhetoric but into the rhetorical discourse, asking why it mattered to individual agents, how it was affectively and aesthetically configured, and what relationships it enabled, instead of following the geopolitical approach that simply calls it a ‘failure’ or a ‘lie’.70 Such an approach to the rhetoric of transnational friendship may speak to other contexts of Third World transnationalism in the Cold War period.

Bibliography

Abbas, Khwaja Ahmad, I Am Not an Island: An Experiment in Autobiography (New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1977).

Ahmed, Talat, Literature and Politics in the Age of Nationalism: The Progressive Writers’ Movement in South Asia, 1932–56 (London: Routledge, 2009), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367817794

Bhattacharjea, Mira Sinha, ‘Mao: China, the World and India’, China Report, 1 (1995).

Bingxin, ‘Yindu Zhi Xing’ (A Journey to India) in Bingxin Quanji Di San Ce (The Complete Works of Bingxin, vol. 3), ed. by Zhuo Ru (Fuzhou: Haixia wenyi chubanshe, 1994), pp. 235–56.

Chen, Jian, ‘China and the Bandung Conference: Changing Perceptions and Representations’ in Bandung Revisited: The Legacy of the 1955 Asian-African Conference for International Order, ed. by See Seng Tan and Amitav Acharya (Singapore: NUS Press, 2008), pp. 132–59.

—, Mao’s China and the Cold War (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

Dube, Rajendra Prasad, Jawaharlal Nehru: A Study in Ideology and Social Change (Delhi: Mittal Publications, 1988).

Fayer, Jean-François, ‘VOKS: The Third Dimension of Soviet Foreign Policy’ in Searching for A Cultural Diplomacy, ed. by Jessica C. E. Gienow-Hecht and Mark C. Donfried (New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010), pp. 33–49.

Fisher, Margaret W., and Joan V. Bondurant, ‘The Impact of Communist China on Visitors from India’, The Far Eastern Quarterly, 2 (1956).

Ghosh, Arunabh, ‘Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History’, The Journal of Asian Studies, 3 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021911817000456

—, ‘Accepting Difference, Seeking Common Ground: Sino-Indian Statistical Exchanges 1951–1959’, BJHS: Themes, 1 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1017/bjt.2016.1

Gienow-Hecht, Jessica C. E., ‘What are We Searching For? Culture, Diplomacy, Agents and the State’ in Searching for A Cultural Diplomacy, ed. by Jessica C. E. Gienow-Hecht and Mark C. Donfried (New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010), pp. 3–12.

Gienow-Hecht, Jessica C. E. and Mark C. Donfried, ‘The Model of Cultural Diplomacy: Power, Distance, and the Promise of Civil Society’ in Searching for A Cultural Diplomacy, ed. by Jessica C. E. Gienow-Hecht and Mark C. Donfried (New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010), pp. 13–29.

Gupta, Bhabani Sen, Communism in Indian Politics (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1972).

—, ‘China and Indian Communism’, The China Quarterly, 50 (1972).

Hutheesing, Raja, The Great Peace: An Asian’s Candid Report on Red China (New York: Harper, 1953).

Jia, Yan, ‘Subterranean Translation: The Absent Presence of Shen Congwen in K.M. Panikkar’s “Modern Chinese Stories”’, World Literature Studies, 12 (2020), http://www.wls.sav.sk/wp-content/uploads/WLS_1_2020.pdf

Mangalagiri, Adhira, ‘Ellipses of Cultural Diplomacy: The 1957 Chinese Literary Sphere in Hindi’, Journal of World Literature, 4.4 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1163/24056480-00404004

Orsini, Francesca, Hindi Public Sphere 1920–1940: Language and Literature in the Age of Nationalism (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Ota, Yuzo, ‘Difficulties Faced by Native Japan Interpreters: Nitobe Inazō (1862–1933) and His Generation’ in Searching for A Cultural Diplomacy, ed. by Jessica C. E. Gienow-Hecht and Mark C. Donfried (New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010), pp. 189–211.

Overstreet, Gene D., and Marshall Windmiller, Communism in India (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1959).

Passin, Herbert, ‘Sino-Indian Cultural Relations’, The China Quarterly, 7 (1961).

Rai, Amrit, Sūbah ke raṅg (Morning Colours) (Allahabad: Hans Prakashan, 1953).

Sankrityayan, Rahul, Chīn men kyā dekha (What I Saw in China) (New Delhi: People’s Publishing House, 1960).

Saunders, Frances Stonor, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (New York: The New Press, 1999).

Sen, Tansen, ‘The Bhai-Bhai Lie: The False Narrative of Chinese-Indian Friendship’, Foreign Affairs, 11 July 2014, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/review-essay/2014-07-11/bhai-bhai-lie

—, India, China, and the World: A Connected History (Lanham: Rowman & and Littlefield, 2017).

Scott-Smith, Giles, ‘Cultural Diplomacy’ in Global Diplomacy: Theories, Types, and Models, ed. by Alison Holmes and J. Simon Rofe (Boulder: Westview Press, 2016), pp. 176–95.

Sundarlal, Pandit, China Today (Allahabad: Hindustani Culture Society, 1952).

Tian, Wenjun, Feng Youlan (Feng Youlan) (Beijing: Qunyan chubanshe, 2014).

Thompson, Carl, Travel Writing (London and New York: Routledge, 2011).

Thornber, Karen L., Empire of Texts in Motion: Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese Transculturations of Japanese Literature (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1dnn9nc

Tsui, Brian, ‘Bridging “New China” and Postcolonial India: Indian Narratives of the Chinese Revolution’, Cultural Studies, 34.2 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2019.1709096

Wernicke, Günter, ‘The Unity of Peace and Socialism? The World Peace Council on a Cold War Tightrope Between the Peace Struggle and Intrasystemic Communist Conflicts’, Peace & Change, 26.3 (2001), https://doi.org/10.1111/0149-0508.00197

Wilcox, Emily, ‘Performing Bandung: China’s Dance Diplomacy with India, Indonesia, and Burma, 1953–1962’, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 18.4 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2017.1391455

Xiao, Qian, Wenxue Huiyilu (Literary Memoir) (Ha’erbin: Beifang wenyi chubanshe, 2014).

Ye, Shengtao, ‘Pianduan Zhi Si’ (The Fourth Segment) in Ye Shengtao Ji Di Ershisan Juan (The Collected Works of Ye Shengtao, vol.23), ed. by Ye Zhishan, Ye Zhimei and Ye Zhicheng (Nanjing: Jiangsu jiaoyu chubanshe, 1994), pp. 166–98.

Zhou, Erfu, Hangxing Zai Daxiyang Shang (Sailing on the Atlantic Ocean) (Chongqing: Chongqing chubanshe, 1992).

1 Arunabh Ghosh, ‘Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History’, The Journal of Asian Studies, 76.3 (2017), 697–727 (p. 700).

2 Jessica C.E. Gienow-Hecht, ‘What Are We Searching For? Culture, Diplomacy, Agents and the State’ in Searching for A Cultural Diplomacy, ed. by Jessica C.E. Gienow-Hecht and Mark C. Donfried (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010), pp. 3–12 (p. 8).

3 Jean-François Fayer, ‘VOKS: The Third Dimension of Soviet Foreign Policy’ in Gienow-Hecht and Donfried, Searching for A Cultural Diplomacy, pp. 33–49.

4 Yuzo Ota, ‘Difficulties Faced by Native Japan Interpreters: Nitobe Inazō (1862–1933) and his Generation’ in Gienow-Hecht and Donfried, Searching for A Cultural Diplomacy, pp. 189–211.

5 Karen Thornber defines ‘writerly contacts’ as the ‘interactions among creative writers’ from different nations; Karen L. Thornber, Empire of Texts in Motion: Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese Transculturations of Japanese Literature (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 2.

6 Tansen Sen, India, China, and the World: A Connected History (Lanham: Rowman & and Littlefield, 2017), Chapter 5.

7 Adhira Mangalagiri, ‘Ellipses of Cultural Diplomacy: The 1957 Chinese Literary Sphere in Hindi’, Journal of World Literature, 4.4 (2019), 508–29 (p. 508).

8 Bingxin, the pen name of Xie Wanying, is also spelled Bing Xin.

9 Chen Jian, Mao’s China and the Cold War (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001), pp. 51–53. The Sino-Soviet alliance broke in 1960 mainly due to their different interpretations of Marxism-Leninism.

10 Rajendra Prasad Dube, Jawaharlal Nehru: A Study in Ideology and Social Change (Delhi: Mittal Publications, 1988), pp. 242–43.

11 Chen Jian, ‘China and the Bandung Conference: Changing Perceptions and Representations’ in Bandung Revisited: The Legacy of the 1955 Asian-African Conference for International Order, ed. by See Seng Tan and Amitav Acharya (Singapore: NUS Press, 2008), pp. 132–59 (p. 133).

12 Mira Sinha Bhattacharjea, ‘Mao: China, the World and India’, China Report, 1 (1995), 15–35 (p. 25).

13 Ibid.

14 Gienow-Hecht and Donfried, ‘The Model of Cultural Diplomacy’, pp. 13–15.

15 Giles Scott-Smith, ‘Cultural Diplomacy’ in Global Diplomacy: Theories, Types, and Models, ed. by Alison Holmes and J. Simon Rofe (Boulder: Westview Press, 2016), pp. 176–95 (p. 177).

16 Ibid.

17 The institutions that Chinese delegations visited in India were not all left-leaning. In addition to ICFA branches, they also visited literary organizations like the Sahitya Akademi and the Indian PEN. For a reception for a Chinese delegation held by the Indian PEN in Bombay, see The Indian PEN, 1 January 1952, pp. 2–3. I thank Laetitia Zecchini for sharing this material.

18 New Age, 16 February 1958, p. 16.

19 Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (New York: The New Press, 1999).

20 Günter Wernicke, ‘The Unity of Peace and Socialism? The World Peace Council on a Cold War Tightrope Between the Peace Struggle and Intrasystemic Communist Conflicts’, Peace & Change, 26.3 (2001), 332–51.

21 Most of my discussion about the peace movement in India is informed by Gene D. Overstreet and Marshall Windmiller, Communism in India (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1959). Due to the authors’ anti-communist stance, I refer to the historical information included in this book while remaining sceptical about their arguments.

22 Bhabani Sen Gupta, Communism in Indian Politics (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1972), pp. 1–65.

23 Overstreet and Windmiller, Communism, pp. 416–17.

24 Gupta, Communism, pp. 26–27.

25 Anand, Karanjia and Abbas were also founding members of the Bombay branch of ICFA and delegates to the 1951 goodwill mission to China.

26 Romesh Chandra, member of the Central Committee of the CPI, seemed to be the only card-carrying communist, who held an important position within the AIPC leadership.

27 Overstreet and Windmiller, Communism, p. 429.

28 Cheena Bhavana at Tagore’s university in Shantiniketan hosted passionate interactions between Indian intellectuals and visiting Chinese academics, artists, Buddhist monks and political leaders, but literary figures were rarely involved. See Sen, India, Chapter 4.

29 Xiao Qian laments in his memoir that when he attended a PEN seminar hosted by E.M. Forster in 1944, he and Anand were the only two representatives of the ‘East’; see Xiao Qian, Wenxue Huiyilu (Ha’erbin: Beifang wenyi chubanshe, 2014), p. 278.

30 Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, I Am Not an Island: An Experiment in Autobiography (New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1977), pp. 329–37.

31 Herbert Passin, ‘Sino-Indian Cultural Relations’, The China Quarterly, 7 (1961), 85–100 (p. 88).

32 See Pandit Sundarlal, China Today (Allahabad: Hindustani Culture Society, 1952), pp. 72–73. An earlier attempt to harmonize socialism with Gandhism was made by Congress Socialist Sampurnanand; Francesca Orsini, The Hindi Public Sphere 1920–1940: Language and Literature in the Age of Nationalism (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 355.

33 Bhabani Sen Gupta, ‘China and Indian Communism’, The China Quarterly, 50 (1972), 279–94 (p. 279). Other than the CPI delegation led by E.M.S. Namboodiripad that observed the eighth CCP Central Committee Conference in September 1956, no CPI leader was formally invited to visit Beijing.

34 Bingxin met Anand during her 1953 visit to India. Li Shui worked as Jainendra’s interpreter during the latter’s 1956 visit to China.

35 K.M. Panikkar, the first Indian ambassador to the PRC, compiled an anthology in English entitled Modern Chinese Stories (1953) during his tenure in Beijing. Panikkar did not translate himself but played a key role in selecting authors and texts and deciding how they would be presented. For the organizational aesthetic and selection strategies of this anthology, see Jia Yan, ‘Subterranean Translation: The Absent Presence of Shen Congwen in K.M. Panikkar’s “Modern Chinese Stories”’, World Literature Studies, 12 (2020), 5–18.

36 For more information about the Chinese short stories published in Hindi magazines, see Orsini’s chapter in this volume.

37 Carl Thompson, Travel Writing (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), pp. 9–33.

38 Tian Wenjun, Feng Youlan (Beijing: Qunyan chubanshe, 2014), pp. 328–29.

39 Zhou Erfu, Hangxing Zai Daxiyang Shang (Chongqing: Chongqing chubanshe, 1992), p. 417.

40 Emily Wilcox, ‘Performing Bandung: China’s Dance Diplomacy with India, Indonesia, and Burma, 1953–1962’, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 18.4 (2017), 518–39 (p. 520).

41 Arunabh Ghosh, ‘Accepting Difference, Seeking Common Ground: Sino-Indian Statistical Exchanges 1951–1959’, BJHS: Themes, 1 (2016), 61–82 (p. 63).

42 Only in the diaries kept by a few visiting Chinese writers that remained unpublished until the 1990s can we find negative comments about India’s caste system and criminal acts. See Ye Shengtao, ‘Pianduan Zhi Si’ in Ye Shengtao Ji Di Ershisan Juan, ed. by Ye Zhishan, Ye Zhimei and Ye Zhicheng (Nanjing: Jiangsu jiaoyu chubanshe, 1994), pp. 166–98.

43 Bingxin, ‘Yindu Zhi Xing’ in Bingxin Quanji Di San Ce, ed. by Zhuo Ru (Fuzhou: Haixia wenyi chubanshe, 1994), pp. 235–56.

44 Rahul Sankrityayan, a scholar whose faith straddled Buddhism and Communism, was an exception. He visited China at the invitation of China’s Buddhist Association; see his Hindi travelogue Chīn men kyā dekhā (New Delhi: People’s Publishing House, 1960).

45 Bingxin, ‘Yindu’, p. 249.

46 Bingxin, ‘Yindu’, pp. 237–38.

47 Bingxin, ‘Yindu’, p. 249.

48 Here, the notion of ‘Mother India’ is best understood as in the 1957 film Mother India, which features the hardships and moral values of a village woman and alludes to post-independence nation-building, rather than the Bharat Mata goddess icon of the nationalist movement.

49 Sundarlal, China Today, p. 4.

50 See Margaret W. Fisher and Joan V. Bondurant, ‘The Impact of Communist China on Visitors from India’, The Far Eastern Quarterly, 2 (1956), 249–65.

51 Raja Hutheesing, The Great Peace: An Asian’s Candid Report on Red China (New York: Harper, 1953), p. 4.

52 Brian Tsui, ‘Bridging “New China” and Postcolonial India: Indian Narratives of the Chinese Revolution’, Cultural Studies, 34.2 (2020), 295–316 (p. 295).

53 Tsui, ‘Bridging’, pp. 306–07.

54 Tsui, ‘Bridging’, pp. 308–09.

55 Tsui, ‘Bridging’, pp. 309–11.

56 The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) shocked Rai and propelled him to re-evaluate his opinions of China and his associations with communism. He later excluded Sūbah from his oeuvre and stopped mentioning it in public. Interview with Alok Rai on 23 October 2016.

57 Nayā Path, June 1954, p. 300. I thank Francesca Orsini for sharing this material.

58 Amrit Rai, ‘Bhūmikā ke do shabd’ in Sūbah ke rang (Allahabad: Hans Prakashan, 1953), n.p.

59 Ibid.

60 Ibid.

61 Rai, Sūbah, pp. 14–15.

62 Ibid., p. 15.

63 Ibid.

64 Rai, Sūbah, p. 17.

65 Tsui, ‘Bridging’, p. 310.

66 Rai, Sūbah, p. 119.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid., pp. 6–7.

69 See Talat Ahmed, Literature and Politics in the Age of Nationalism: The Progressive Writers’ Movement in South Asia, 1932–56 (London, New York, New Delhi: Routledge, 2009), pp. 157–61.

70 See Tansen Sen, ‘The Bhai-Bhai Lie: The False Narrative of Chinese-Indian Friendship’, Foreign Affairs, 11 July 2014, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/review-essay/2014-07-11/bhai-bhai-lie