3. Literary Activism: Hindi Magazines, the Short Story and the World

© 2022 Francesca Orsini, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0254.03

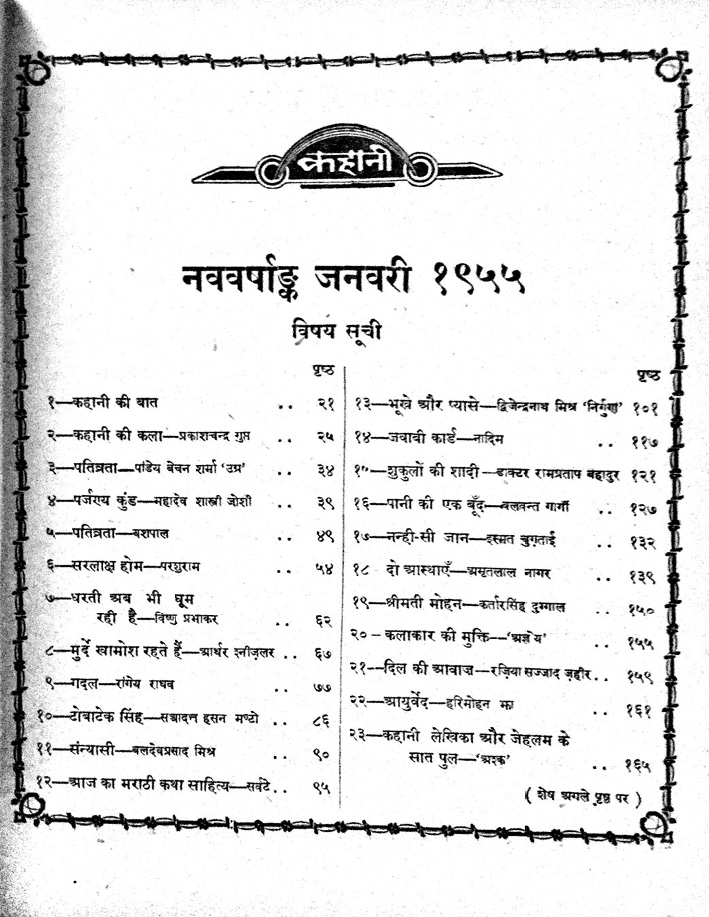

If in January 1955 you had picked up the special new-year issue of the Hindi story magazine Kahānī (Story) (1954, Fig. 3.1), you would have been able to read S. H. Manto’s Partition masterpiece ‘Ṭobā Ṭek Singh’1 and Ismat Chughtai’s blood-curling domestic story ‘Nanhī sī jān’ (A Tiny Life), originally written in Urdu; two of Hindi’s most famous stories, Krishna Sobti’s brooding ‘Bādalon ke ghere’ (Gathering Clouds) and Kamleshwar ‘Kasbe kā ādmī’ (Small-Town Man), amidst twenty-odd stories by famous Hindi writers of the older generation (Ugra, Yashpal, Vrindavanlal Varma, Ashk, Agyeya) and upcoming ones (Bhisham and Balraj Sahni, Kamleshwar, Markandeya, Ramkumar, and so on). You could have sampled a dozen pieces by contemporary Bengali, Urdu, Marathi, and even Kashmiri writers. But you would also read translations of some of the best-known European stories—Theodor Storm’s ‘Immensee’ (1848), Anton Chekhov’s ‘Gusev’ (1890), Arthur Schnitzler’s ‘The dead are silent’ (1907), Maxim Gorky’s ‘An Autumn Night’ (1895), as well as the soon-to-be Nobel prize winner Halldór Laxness’s ‘Slaughterhouse’ and a contemporary Chinese story.2 Through just one 400-page bumper issue you would have gained a good sense of whether older Hindi writers were still producing interesting work, which new ones were worth following, who was writing what in other Indian languages, and how Indian stories compared to those by the European masters of the craft and by Chinese ‘brothers’.3

Fig. 3.1 Table of contents for January 1955 special issue of Kahānī. Author’s photograph, courtesy of Sara Rai.

Magazines have loomed large in Hindi literary lore. They were the arena in which critical debates about aesthetics and ideology were fought, and the main platform on which contemporary Hindi poets and fiction writers presented their new work and found readers and recognition. Publication in book form and academic consecration only cemented reputations first forged on the pages of magazines, which were oriented towards new talent and new material. Despite their ephemeral nature—particularly in the Hindi context, where old books and periodicals are sold in bulk as scrap paper—magazines embody, and capture for us eager after-readers, a lively critical and creative imagined community. To borrow Amit Chaudhuri’s phrase, magazines were sites of intense ‘literary activism’: an activism by editors on behalf of literature to champion new writers and encourage readers’ tastes, but also a constant critical interrogation on the value and function of literature.4

But while magazine activism, particularly in US scholarship, is associated with ‘little magazines’ and the avantgarde, in the Hindi context magazines were simply the mainstay of literary publication, and in most cases they can hardly be called ‘little’.5 In the early twentieth century, for example, Hindi magazines were mostly hefty monthly miscellanies of over one hundred pages that dealt with all matters political, social, and literary.6 In the 1950s to 1970s, the period this essay covers, magazines ranged from very literary small imprints, medium-sized enterprises, literary-political reviews, illustrated weekly broadsheets, ‘middlebrow’ miscellanies and downright commercial ‘timepass’ story magazines. Hindi magazine circulation ranged between 15,000 to 100,000, many times higher than the print run of any new literary book.7

Magazines thrive on short forms, and historically magazines worldwide have been linked to the success of the short story as a modern literary form.8 ‘The story is the oldest literary genre… and the newest’, wrote the editor of another Hindi story magazine, Sārikā (Starling). The oldest, because tales (kathās) are found at the beginning of every culture; the ‘newest’ because the modern short story had developed only in the nineteenth century.9 In Hindi, the story (kahānī) first emerged in magazines in the first decade of the twentieth century, and it was magazines that allowed Premchand (1884–1936), the most celebrated and popular Hindi-Urdu fiction writer of the 1910s to 1930s, to thrive as an independent writer. Already in the 1920s, the story emerged as a protean form, which could be a vehicle of aesthetic experimentation, social reform, political mobilization, entertainment, or romance—or several such goals at the same time.10 In the 1950s, a number of Hindi magazines devoted themselves exclusively to stories. Some, with titles like ‘Juicy Stories’ and ‘Entertaining Stories’ (Rasīlī Kahāniyān, Manohar Kahāniyān), included mostly thrilling, melodramatic, or funny stories and were geared towards ‘timepass’ reading, as on train journeys.11 Others were more serious and literary, like Kahānī (edited by Premchand’s son Shripat Rai with Bhairavprasad Gupta and Shyamu Sanyasi, 1954), Naī Kahāniyān (New Stories) (1959, ed. Bhairavprasad Gupta) and Sārikā (1960, ed. Chandragupta Vidyalankar and later Kamleshwar). Such diversification did not exclude overlaps, and it was not unusual to find stories by writers like Manto or Rajendra Yadav, or even Dostoevsky, packaged as thrilling ‘timepass’ reading.12 Both writers and editors were after all on the lookout for publishing opportunities and printable material. Kahānī, Naī Kahāniyān and Sārikā form the archive of this essay. Hindi writer and editor Kamleshwar (1932–2007), who started out as writer and translator at Kahānī in the 1950s, and became editor of Naī Kahāniyān and then of Sārikā between the mid-1960s and the late 1970s, is one of the heroes of this story.

If they are now remembered in Hindi as platforms for Hindi literature and criticism, in the 1950s to 1970s Hindi magazines were remarkable sites of literary activism in other ways, too. As the January 1955 issue of Kahānī shows, magazines strove to regularly present readers with contemporary writing from other Indian languages, and also from an increasingly wide range of foreign literatures. In the case of Indian languages, this was clearly a nation-building effort: to create a national literary field in which readers and writers would be familiar with what was going on in other regional literary fields.13

A different goal dictated the choice of foreign works: the desire to make world literature visible and familiar. But which world literature? As Laetitia Zecchini puts it, the ‘Cold War can be understood both as a form of “synchronization” of literatures across the globe, and conversely, as a form of disjunction, with world literatures and cultures partitioned along antithetical ideologies’.14 Indeed, the magazines’ choice of foreign stories to translate often mapped directly onto Cold War political affiliations—which is why we see so many Chinese, Eastern European, and Russian stories regularly translated in 1950s Progressive Hindi magazines, while other magazines opted for European and American writers.15

In the 1960s, a growing interest in African decolonization and the emergent discourse of Third-Worldism made African, Latin American, and South-East Asian stories visible to Hindi magazine readers for the first time, creating new ‘significant geographies’.16 But with a paradox: when in the 1950s and 1960s India under Nehru was politically non-aligned, Hindi magazines were largely politically aligned in their literary internationalisms. When Non-Alignment hollowed out politically in the early 1970s after Nehru’s death, a Hindi editor like Kamleshwar reframed Third-Worldism as a third way between the two Cold War literary fronts. In the Sārikā special issue expressly dedicated to the ‘Third World: ordinary people and writers as fellow travellers’ (in January 1973), Kamleshwar embraced the definition of Third World as the postcolonial condition of underdevelopment after centuries of colonial exploitation, a condition shared by the ‘ordinary people’ of Africa, Latin America, and South- and South-East Asia:

From a political viewpoint, the ‘Third World’ is the grouping of geographical units that have gathered on a single platform and accepted that name. But if we move away from that viewpoint and look and connect ourselves to the ordinary people [jan-sāmānya] dwelling in those different parts of the world we shall see that most of the Third World lives in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia. In a way, the southern part of the globe is the Third World. Human beings from this world have been confronting similar inhuman conditions for centuries. Slavery, mistreatment [anāchār], exploitation, poverty, inhuman repression have been piled onto them, and this has been held to be their destiny [niyati]. The so-called civilized and educated world has done nothing beside milking it like a milch cow. What has been given in the name of spreading the light of civilization has been a mongrel [doglī] culture, the killing of the economic system and strangling of political institutions. Today, though, the Third World man is throwing the many lice off his collar and is taking the right [adhikār] of deciding his destiny in his own hands.17

The postcolonial subject—including both toiling worker and alienated intellectual—is shaking off a yoke that is both political and economic but also intellectual and creative (see Zecchini in this volume). Yet, as we shall see, despite this Marxist analytical language, Kamleshwar’s choice of stories and his aesthetic credo moved resolutely away from an alignment with Leftist internationalism. Rather, as he had evocatively put it, riffing off Guimarães Rosa’s story ‘The Third Shore’ (A Terceira Margem do Rio, 1962), the literature of the Third World was the voice of the fate of living midstream, tired of both shores.18 Third World here stood in for non-European stories rather than for stories that embraced a postcolonial vision.

Making world literature visible is never just a geographical gesture, but also a temporal one. How are we to understand the choice of magazine editors to publish ‘the latest’, or else modern or earlier ‘classics’—in other words, a temporal as well as spatial production of world literature? Building on Andrew Rubin’s argument that ‘the accelerated transmission’ of texts across journals affiliated to the Congress for Cultural Freedom in the 1950s and 1960s ‘respatialize[d] world literary time’, Elizabeth Holt has proposed that this ‘near-simultaneous publication of essays, interviews, and sometimes stories and poems in multiple [CCF] journals and affiliated publications engendered a global simultaneity of literary aesthetics and discourses of political freedom and commitment’.19 While this is indeed the language that magazine editors often spoke in this period, what they publish tells a different story. As we shall see, multiple and competing visions of world literature could be found in the same magazine at the same time—tracing different ‘significant geographies’ and belying simple geopolitical polarities. Historical surveys and lessons from the ‘masters of the story’ tended to be Eurocentric and feature French, British, Russian, and American writers, whereas the decolonizing impulse and interest in the ‘contemporary sensibility’ of a ‘world in transition’ drew magazine editors to texts from Africa, Latin America, and South-East Asia—countries and literatures ‘we know little or nothing about’.20 In the process, older texts were ‘transported’ into the present. A great many authors and stories that we now consider foundational to Latin American, African, and postcolonial literatures—from Horacio Quiroga, Jorge Luis Borges, and Mario Benedetti to Juan Rulfo, José Donoso, Miguel Asturias, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, from Chinua Achebe and Ngugi Wa Thiong’o to Cyprian Ekwensi and Alex LaGuma, from Mahmud Taimur to Laila Baalbaki, from Pramudya Ananta Toer to Mochtar Lubis and many, many others—were translated and read in a Hindi mainstream magazine like Sārikā as early as the 1960s and 1970s. As a result, Hindi readers and editors appear to us strikingly less parochial and much more internationalist than we may surmise when we think of Hindi as a ‘regional’ language or bhasha.

Form in this essay is therefore a genre (the story) and a platform or medium (the magazine). I am interested in how foreign stories in Hindi magazines were framed, discussed, shaped, and read in the context of Cold War ideological debates and competing internationalisms, and how Hindi magazines created expansive ‘significant geographies’ of world literature that made this remarkable array of authors and texts not only visible, but readable, for ordinary Hindi readers. Roanne Kantor has called this kind of world literature a ‘fantasy of solidarity’, particularly if viewed from the current market-oriented perspective dominated by multinational book conglomerates, the Anglophone novel and its literary prizes.21 I would agree with Kantor, but only if we consider fantasy not as the opposite of reality but as a world-making activity that helps to create reality.

Hindi magazine editors experimented with different formats for world literature: regular translation slots, broad surveys, dedicated columns and articles, or impressive special issues, producing ‘thick’ or ‘thin’ familiarity.22 As I argue below, the bumper special issues that Kamleshwar devoted to world stories around different themes in particular produced a ‘spectacular internationalism’ that paralleled and even exceeded that of the Asian-African Writers’ Association’s magazine Lotus.23 Such spectacular special issues made visible and palpable the richness and variety of African, Asian, and Latin American literatures, while the presence here and there of contemporary European and North American writers as part of this panoply only emphasized the non-centrality of the latter.

Yet however spectacular—and impressively early—this archive of world literature translations into Hindi makes us wonder about how the medium influences or determines our experience of world literature. Is the experience of reading world literature in the magazine different from that of reading a book, a book series, an anthology, or from studying texts as part of a world literature course, or seeing them canonized through prizes? Apart from one exception, celebrated writer Nirmal Varma’s translations from Czech, stories translated in the magazines were never published in book form and left no trace in terms of the migration of books or ‘bibliomigrancy’ through libraries or publishers’ catalogues.24 Rather, they were often plucked out of other magazines, collections and anthologies to be translated as stand-alone pieces. Did these magazine translations leave a lasting impression on readers, did they create a habitus for world literature, and a lasting archive?

The Hindi Print Ecology of the 1950s

Looking back at the 1950s and 1960s, we can see how the remarkable efflorescence and range of literary talent, from Dharmavir Bharati to Phanishwarnath Renu, Mohan Rakesh to Nirmal Varma, Krishna Sobti to Krishna Baldev Vaid, Shivaprasad Singh to Nagarjun, Mannu Bhandari to Kamleshwar and Rajendra Yadav, to name but the most famous, was sustained and supported by a large network of magazines that published their new work.

Working with magazines as one’s archive requires us to look at each individual issue and each magazine as a self-contained text, but also at each magazine as a platform for different voices and agendas, as well as part of a wider ecology of print publications. The last point is nowhere clearer than in 1950s and 1960s India, where magazines proliferated and many readers acknowledged that they read more than one, in Hindi and English (Fig. 3.2).25 Despite the fact that most magazines featured female beauties on their covers and stories and, in most cases, sought out a direct dialogue with readers, this was a highly populated and nuanced magazine space. In each case, the number and types of ads and illustrations, the more or less visible editorial line, and the presence or absence of political commentary gives us clues about their position in the field.

The Times of India Group alone published six magazines: the Hindi illustrated weekly Dharmayug and English Illustrated Weekly of India; the English film weekly Filmfare, Hindi story monthly Sārikā, and children’s monthly Parāg (Pollen), and English illustrated women’s weekly Femina.26 The Delhi Press published the ‘middlebrow’ English illustrated monthly Caravan (1940) and smaller-sized Hindi and Urdu Saritā (respectively c.1945 and 1959). The story magazine Naī Kahāniyan and the critical monthly Ālochnā (Criticism, 1951) were imprints of the leftist publisher Rajkamal Prakashan, while Nayā Path (New Path, 1953) was a smaller communist/Progressive activist enterprise coming out first from Bombay and then from Hindi writer Yashpal’s publisher Viplav Prakashan in Lucknow. Another important Hindi monthly, Kalpanā (Imagination, 1949), with a broader coverage of the arts and striking covers by M. F. Husain, came out from Hyderabad. English magazines that published literature include the already-mentioned Illustrated Weekly of India and two ICCF-funded publications: the monthly Quest (1955), from Bombay, and the political broadsheet Thought (1949) from Delhi (see Zecchini in this volume).

Interestingly, Hindi and English magazines from this period reveal a smaller cultural and class distance between them, certainly compared to the situation today in which the two literary fields appear as quite separate, and very hierarchical, worlds. Translations and literary references in Hindi magazines reveal that many Hindi editors and readers read broadly in English, too. At the same time, English magazines like the Illustrated Weekly and Quest regularly featured and reviewed contemporary writing in Hindi and other regional languages. In the Illustrated Weekly, stories by Krishna Baldev Vaid, S. Subbulakshmi and others from Hindi, Bengali, Telugu, and other regional languages appeared frequently, side by side with stories in English, and the magazine even attempted a regular column on the Hindi literary world called ‘A Window into Hindi Writing’.27 In other words, while Hindi magazines are remembered for their role in fostering Hindi writing and debates, it pays to read together Hindi and English magazines as part of an integrated, multilingual ecology of reading and publishing.

In Hindi literary histories, this period is remembered for the continued ideological-aesthetic struggle between Progressives and Experimentalists which had been going on since the late 1930s. The debate on the aesthetic and function of literature, hinging on ideas of aesthetic freedom versus social usefulness, morphed in the 1950s into a bitter dispute between the Progressives and the Experimentalists, largely grouped around Sacchidanand Hiranand Vatsyayan ‘Agyeya’ (1911–1987) and the Parimal group in Allahabad.28 Experimentalists accused the Progressives of turning literature into political propaganda, while the Progressives accused Experimentalists of wallowing in individualist and formal concerns and turning their backs on the urgent needs of the country and of society.

Inevitably, these debates took on Cold War overtones. The Indian Council for Cultural Freedom (ICCF) and its magazine Quest paid close attention to the activities of the Parimal group, and the foremost Hindi Experimentalist ‘Agyeya’ was for a while closely involved in the ICCF. It was he who organized its first conference in India in 1951 (see Zecchini in this volume) and edited the weekly Thought.29 Progressives scoffed at the ICCF’s call for ‘cultural freedom’ for its ‘infatuation with capitalist values’ and for ‘trying to destroy our artists’ ethical stance with the poison of mistrust’.30

At the same time, another struggle was going on in the early 1950s within the Progressives over control of the Progressive Writers’ Association, between hardliners within the Communist Party of India and communists and sympathizers who supported a broader United Front (samyukt morchā in Hindi) of democratic forces. This was sometimes framed as a conflict between Soviet- and Chinese inspired literary ideologies.31 Hindi Progressive writers and critics quoted Soviet theorists and Mao’s Yunan Theses and took part in Peace Congresses, while Soviet and Chinese magazines and books flooded the Indian market.32 As we shall see in the next section, these different aesthetic and ideological alignments translated into different geopolitical visions or ‘significant geographies’ of world literature.

It is useful to bear in mind, however, that harsh and uncompromising though these critical struggles were, particularly in print and at literary meetings and conferences, personal friendships crossed ideological faultlines. Moreover, the same critics and writers published articles and stories in magazines like Kahānī, Kalpanā, Naī Kahāniyān or Sārikā. And when modernist or progressive stories appeared in Saritā or Dharmyug, particularly after former Parimal member and Modernist poet, playwright, and novelist Dharmavir Bharati became the latter’s editor in 1959, they reached a broader public.33

Finally, the new generation of New Story (or Nai Kahani) writers like Mohan Rakesh, Nirmal Varma, Mannu Bhandari, Kamleshwar, and Rajendra Yadav that emerged in the mid-1950s and that would dominate the literary scene for the next decades sought a way out of the ideological impasse between Progressives and Experimentalists. They developed an aesthetics based on a commitment to ‘the authenticity of inner experience’ and to the ‘new conditions’ of post-colonial India.34 As already intimated, this aesthetics also produced its own internationalism and vision of world literature.

The Magazine as World Literature

How do magazines produce world literature? Let us pause on this question, and on the magazine as a location, a site, and a means for world literature. Much of the recent debate around world literature has revolved around the curriculum, anthologies, publishers’ series, or book prizes,35 yet in India exposure to and discussion of literature from other parts of the world mainly took place in the pages of periodicals. But how is the medium part of the message: what kind of experience of world literature do magazines create? Does their reliance on short forms (the review, the short note, occasionally the poem or the short story) and on fragmentary, occasional, token offerings produce a particular experience of world literature, a kind of familiarity through repetition or even simple visibility? How is such an experience different from the more systematic ambition and relatively stable arrangement of the anthology, the book series, or the college course?

Three axes seem relevant to this question. The first axis is visibility: before a foreign literature can become familiar to readers and become part of world literature, it needs to be made visible. (By contrast, invisibility actively produces ignorance, a point that world literature discussions do not emphasize enough.)36 How a magazine produces visibility, and with it familiarity, varies. The coverage and the ‘textual presence’ of an author or a literature may be ‘thick’ or ‘thin’—the second axis—though often it is a combination of both. ‘Thick coverage’ includes repeated coverage over several issues, translations (what I call ‘textual presence’) accompanied or introduced by critical discussions, and comparative gestures that help make an author or a text familiar.37 ‘Thin’ coverage includes random, occasional, or poorly identified translations, name-dropping in surveys that produce no name recognition, and snippets of de-contextualized information. If thick coverage produces closeness for the reader, thin coverage can be seen as a form of distant reading (in Franco Moretti’s terms), though it does produce some visibility, something which we should appreciate. The third axis to be considered is world literary time as well as space: coverage of ancient literature from a region may suggest temporal depth and layers within a tradition, but it can also imply that no modern or contemporary literature exists or that, if it does, it cannot match the ancient one.38 Conversely, emphasis on the latest contemporary writing may produce an exciting sense of coevalness and shared enterprise, or else it may suggest that a literature has no depth of tradition behind the contemporary.

In the early twentieth century, Indian periodicals like the Modern Review had presented world literature as a discovery of the plurality of the world beyond India and the British empire, and a redressal of the asymmetric balance and exchange between East and West.39 In the 1950s and 1960s, almost all Hindi and English magazines tried to ‘do’ world literature in some form with whatever resources they had. But rather than sharing in a ‘global simultaneity of literary aesthetics’ (Holt), both temporally and aesthetically they chose different strategies that played out different meanings (and axes) of world literature, often at the same time: world literature as the classics; the best of (a particular genre); the latest or contemporary; and the politically like-minded.

If we take spatial visibility (and recursivity), textual closeness/distance, and world literary time as axes, some magazines chose what one may call ‘random systematicity’, in other words they tried to be systematic about covering world literature but then filled a country’s slot with random pieces, like Caravan’s ‘Stories from around the World’.40 Other magazines chose ‘textual distance’: the monthly Yugchetnā (Consciousness of the Age, 1955), which saw its mission to ‘introduce Hindi writers and readers to world literature of a developed level’, did so only indirectly through critical articles, book reviews, and no translation; its contributors’ preference for classical traditions and for English literature betrays their academic roots.41 Quest, the ICCF journal, also chose textual distance—fresh literary ‘news from Paris’, book reviews, and articles on American, Western European, and non-Soviet Russian writers—while carefully calibrating literary time: only translations of classical Chinese literature were reviewed. Contemporary foreign writers affiliated to the international CCF contributed with thought-pieces rather than poems or stories, while for example Africa featured only as a ‘problem’.42

The Hindi literary and art magazine Kalpanā also chose textual distance, and in 1958 tried to telescope the distance between Hindi readers and world literature by translating from the American magazine Books Abroad lengthy surveys of recent foreign literatures—Spanish, Spanish-American, Brazilian, Israeli, German, Austrian, Irish, Greek, Chinese, Israeli, and so on—written by distinguished academics at American universities. These dense and comprehensive pieces undoubtedly made these literatures visible and produced a sense of temporal depth and substance. For example, Enrique Anderson Imbert’s piece ‘Spanish American literature of the past 25 years’ listed scores of Latin American literary trends and authors from the nineteenth century onwards, singling out a few like Gabriela Mistral, Alfonso Reyes, Jorge Luis Borges, or Pablo Neruda, but mostly handing out brief one- or two-word assessments of the others (such as ‘honest’, or ‘solipsistic’).43 What happens, we may ask, when you read long lists of literary movements and of writers’ names (often garbled in transliteration) without any textual contact, in other words without reading any of their works? Only a familiar reader would pick out Horacio Quiroga, Rómulo Gallegos, or Miguel Angel Asturias.

By contrast, the story magazine Kahānī ‘did’ world literature through direct and regular ‘textual presence’, usually translating one foreign story per issue, occasionally more, as we saw in the special issue of January 1955 with which I started this chapter. Textual presence was also the strategy for contemporary literature from other Indian languages, which made up half of every issue of Kahānī. I explore the magazine’s coverage of foreign literature in greater detail below. Here we may note that whereas Indian stories came with brief introductions to their authors that evoked a strong sense of literary community, foreign stories came mostly without any paratext, sometimes because the editors assumed these foreign writers to be so well known that they needed no introduction, at other times suggesting a ‘thinner’ coverage and a commitment that was only symbolic.44

The same strategy of textual presence held for Hindi story magazines of the 1960s like Naī Kahāniyān and Sārikā. They also began by featuring only one foreign story per issue, but Kamleshwar, who went from editing Naī Kahāniyān to Sārikā in 1965, was particularly keen on special issues and dramatically increased the presence, frequency, and geographical scope of foreign literature.45 The annual bumper special issues (visheshāṅk) of foreign stories that Kamleshwar introduced comprised mostly contemporary African, Latin American, and Western, South-Eastern, and East Asian texts (Tables 1 and 2)—producing a spectacular literary visibility for Third World internationalism, as we have seen.

Table 1 Contents of special issue on the Foreign Story, Naī Kahāniyān, May 1964.

Table 2 Contents of special international issue, Sārikā, January 1969.

|

Thailand: Dhep Mahapaurya |

|

|

Uruguay: Mario Benedetti |

|

|

Mauritius: Abhimanyu Unnath |

|

|

Ghana: Efwa Sunderland |

|

|

Singapore: S. Rajaratna |

|

|

Sierra Leone: Abioseh Nicol |

|

|

Japan: Hayama Yoshiki |

|

|

Yugoslavia: Milovan Djilas |

|

|

Hungary: Judith Fenekal |

In addition, soon after he became Sārikā’s editor, Kamleshwar contributed a series of articles on the contemporary story in countries like Egypt, Iran, and Indonesia. Such articles made those literatures and their authors not just visible but also familiar to Hindi readers, as Kamleshwar consciously drew parallels with developments in Hindi, culminating with the Hindi Nai Kahani. ‘Arabic New Story’ Egyptian writers of the post-war generation like Yusuf Idris, Sofi Abdullah, Said Abdu, and Youssef El Sebai were involved in a ‘search for new values’ (naye mūlyon kī khoj), Kamleshwar wrote: ‘Even there the emphasis lay on the authenticity of inner experience in the story’ (kahānī kī anubhūtiparak prāmāṇiktā par hī vahān bhī zor diyā gayā); and ‘just like the Hindi Nai Kahani, the story there first of all began its search in the field of language’.46 Indonesia had gone through a similar quest for an indigenous national language; the story there had become established ‘on an intellectual basis as a serious and responsible literary genre’ with Idrus (spelt Indrus).47 Mahmud Taimur and Pramoedya Ananta Toer became even more textually present in Sārikā and familiar to its readers once their stories were translated.

Yet this vision of world literature that made so visible the literatures of the Third World and encouraged parallels with contemporary Hindi writing was balanced by other ideals. Sārikā’s regular column in 1965 on ‘What is the story? In the view of the masters’ featured curated extracts by Flaubert, Camus, Sartre, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, D. H. Lawrence, but also Aldous Huxley, Colin Wilson, Norman Mailer, and Jack Kerouac—a much more European and Atlantic canon. Another regular column in 1966 bred familiarity with contemporary writers (and other celebrities) through autobiographical selections: the column included Vincent Van Gogh, Simone de Beauvoir, Arthur Adamov, Hemingway, Henry Miller, Evtušenko… and Sophia Loren!

Before I turn to the specific question of whether this coverage maps onto Cold War affiliations, allow me one more detour on the question of the story as a genre and unit of world literature.

The Story (in the) Magazine

With the new generation of New Story (Nai Kahani) writers after Premchand and after Independence in 1947—Kamleshwar prominently among them—the story became the most theorized literary genre in Hindi, laden with multiple expectations.48 A ‘democratic’ genre, the story was supposed to guide and accompany readers in their daily lives, and at the same time teach the craft of writing to budding writers. Story magazines were therefore both reader- and writer-centric, and editors addressed both. Kahānī for example encouraged readers and young writers to come together to form Kahānī Clubs where they would exchange their views on the stories published. The goal for stories published in ephemeral magazines was to be original and ‘unforgettable’, to challenge readers and budding writers without descending into obscurity or opacity. Progressive writer Amrit Rai’s letter to the editor of Kahānī (his younger brother Shripat) captures the sense of what the task of the magazine and of the short story was supposed to be:

I hope that Kahānī will free Hindi readers from the clutches of Māyā and Manohar Kahāniyān [low-brow story magazines]. Helping to pass the time on a railway journey is not the only goal of a story. A story helps understand the map of life; it prepares one to respond to every turn in life; it enters one’s heart and slowly begins to shape one’s mind in a new mould, which is the mould of a better, more compassionate, human, and sensitive person. A story takes up all aspects of life, all sides. It contains all kinds of characters, all kinds of circumstances in life, sweet and bitter truths. A reader educated through good stories finds herself stronger and better equipped to face life. It’s not by chance that Kalinin gave such importance to stories and novels in the education of the ideal communist.49

In the context of the fierce literary and ideological debates between Progressives and Experimentalists, stories were judged on the basis of craft, theme, characterization, but also of the values they propounded. One of the long-running themes for debate among readers (and writers) on the Kahānī Club page of Kahānī was, ‘Is entertainment the aim of the story?’, with respondents overwhelmingly writing that entertainment was important but could not be the only aim.50

But Kahānī combined ‘soft progressivism’ with an emphasis on aesthetics. If progressivism meant an emphasis on stories that shone a critical light on the problems of the present, like poverty or corruption,51 ‘soft progressivism’ implied a democratic understanding of literature: the magazine aimed to provide good stories for readers with little money and leisure and tired at the end of the working day (‘good stories at a good price’, ‘1500 pages at Rs 15 pa’).52 Kahānī Club aimed to bring writers and readers closer to each other, but also to ‘train’ readers and young writers into developing critical standards of appreciation.53 Translation was key to this vision, and Amrit Rai’s suggestions for Kahānī capture what it was doing already:

1. Publish translations of the world masters (ustad) of the story: Tolstoy, Chekhov, Turgenev, Gorky, Maupassant, Balzac, O. Henry, Jack London, etc.54 Their literature has been hardly translated into Hindi, and often very badly.

2. Translate the best stories from Indian languages: not just Urdu and Bengali, but also Marathi, Telugu, Tamil. Publish an Urdu and Bengali story in every issue. Not at random, but choosing the best ones.

3. Don’t fall for the temptation of older and established writers in Hindi—look for new talent.

4. Publish humorous stories, one per issue. There is a strong tradition in Bengali, Urdu, English, yet hardly in Hindi.55

Naī Kahāniyān and Sārikā also encouraged discussions of the story as a genre, through readers’ letters in response to particular stories or special issues, and through columns presenting authors’ views, like ‘What is a story? In the eyes of a master’; and ‘X: in their own eyes’.56 Kamleshwar’s short editorials emphasized the role of the story as running parallel (samānāntar) with readers’ lives—not a reflection but an attempt to express the language of their dreams, aspirations, concerns, and desires. This made the form of the story a universal language:

If, between this whole progress [pragati] and stagnation [agati] and in the course of the immense journey of events and history, we want to pause for a moment and recognize what a human being [manushya] is, meet him/them, we can only meet their ‘thoughts’, and it is only very few who are able to express their thoughts… in other words whose thoughts we can encounter.

Apart from giving expression to their thoughts, most human beings think in the language of dreams, aspirations, concerns and desires. The script of that language may be English, Russian, Spanish, Arabic, Japanese and so one, but the name of that language is story.

This Sārikā special issue on foreign literature is an attempt to offer a glimpse of the story searching for the experiences and desires of human beings going through this frightening period of history.57

Kamleshwar’s call to writers to ‘live the present to the full’ (vartamān ko pūrī tarah se jīnā), and for the story to parallel life by ‘engaging with context’ (parivesh se sambaddhatā) and with life (jīvan se sambaddhatā) and to ‘join the ordinary individual with full honesty’ (sādhāraṇ vyakti ke sāth gahrī īmāndārī se juṛnā), bypassed political affiliation without forsaking the language of engagement. But whereas the Progressives had urged writers to write about urban and rural working classes, the Nai Kahani’s call to ‘authenticity of inner experience’ meant that urban, middle class Nai Kahani writers felt they could write only about urban middle- and lower-middle class characters like themselves.

Calling the story (kahānī) a ‘universal language’ made unfamiliar and very disparate texts—from Ngũgĩ’s ‘Deshbhakt’ (1969, ‘Martyr’), Marquez’ ‘Dopahar kī nīnd’ (1973, ‘Siesta del martes’, 1962), Borges’ ‘Paristhitiyon kā sūtr’ (1964, ‘Emma Zunz’, 1949) to Alain Robbe-Grillet’s ‘Samudra ke taṭ’ (1969, ‘La Plage’, 1962)—not just visible but readable to Hindi readers. Intriguingly, this emphasis on the story as a universal form de-emphasized the interlinguistic process of translation, as well as the actual channels Hindi editors and translators (whose names barely appear) drew upon. English was—it must have been—the medium, and English-language publications the source of these translations, but they are not mentioned once. I return at the end to this silence about the process of translation and the invisibility of translators, contacts, and networks, which usually feature so prominently in discussions of literary internationalisms for magazines like Lotus, or the magazines connected with the Congress for Cultural Freedom, or the circulation of texts as part of world literature. Why are Hindi magazine editors so resolutely silent about them?

The Cold War, Third World, and Magazine Activism

While in the 1950s India’s Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru pursued a high-profile foreign policy of non-alignment—as one of the protagonists of Bandung and architects of its Panchsheel manifesto—the Indian print market was flooded with Soviet and Chinese books and magazines that translated Russian and Chinese literature, as already mentioned. On the other side of the Cold War divide, India was viewed as a lynchpin of the CCF counter-propaganda strategy to win over the ‘Asian mind’, i.e. Asian intellectuals, and to combat the spread of Communism over Asia.58 Not only did the CCF sponsor the magazine Quest, it also sent books and magazines to the US cultural centres in India through USIS and the Books Abroad programmes.59 Hindi editors never mention where they sourced their translations, but some detective work shows that it was magazines like Soviet Literature (for Kahānī) or the New-York based Short Story International (for Naī Kahāniyān and Sārikā).60

In the 1950s, the choice of foreign literature translated, reviewed, and advertised could be taken as an index of the political affiliation of an Indian magazine. And yet, if we take into account visibility and recursivity, ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ coverage and temporality, the picture that emerges is more complex. Geopolitical orientation ‘lifted’ even older writers and texts into the horizon of the present, and appeals to craft trumped ideological and geopolitical affiliations. And by the mid-1960s and early 1970s, in place of the earlier polarization between the Western and Eastern blocs, literary and mainstream magazines like Naī Kahāniyān and Sārikā shifted towards the Third World and lent unprecedented visibility to Latin American, African, and Asian literatures.

Though Kahānī in the 1950s did not only publish progressive Hindi or Indian writers, its choice of foreign stories definitely betrays a Leftist orientation. Geographically, Kahānī allotted most space to contemporary Chinese writers and writers from the Eastern bloc (see Table 3).

Table 3 Foreign writers published in Kahānī between 1954 and 1958.

Temporally, however, many of the latter belonged to pre-Communist times, like Chekhov or Ivan Čankar. Or Zsigmond Móricz (1879–1942), a Hungarian writer—so part of the Eastern Bloc—but from the pre-Communist generation, a contemporary of Premchand. His story ‘Seven Pennies’ combines a depiction of poverty with humour and centres on an ‘unforgettable’ character, which may be why it was selected. The narrator recalls his remarkable mother, so poor that she did not even own a table, yet always cheerful. One day she needs seven pennies to buy soap and wash her husband’s clothes. While turning the barren house upside down to find them, she manages to make the search riotously funny by giving each penny a personality—one likes hiding, the other has run away—though the reader can perceive the strain. At the end, it is a man who comes begging who gives her the last penny she needs: the poor helping the poor.61

Or take Jomo Kenyatta’s parable ‘The Gentlemen of the Jungle’ (translated as ‘The Elephant and the Man’), possibly the first African literary text published in Hindi.62 Kenyatta wrote it in 1938, but to Hindi readers he is introduced in clear terms of anticolonial solidarity:

Who in the world is unfamiliar with Jomo Kenyatta, the writer of the story ‘The Elephant and the Man’, written in the guise of a folktale. Nobody will be unaware of the mass movement that this popular revolutionary leader of Kenya has been leading to free his country from British foreign rule. He has been the victim of British violence several times. Once a famous British judge was beaten up for defending him in a trial. The British press is giving Kenyatta a bad name by calling him a Mau Mau. Surprisingly, Kenyatta, who is an African scholar who knows six languages, is unfamiliar with the word Mau Mau.63

Even among Soviet and Chinese stories, the more stridently propagandist—like the progressive wedding in Ku-Yu’s ‘Nayā Yug’ (New Age), are comparatively few in comparison with those dealing with politics in a more oblique way.64 Lu Xun’s ‘Havā kā rūkh’ (Where the wind blows), for example, focuses on a local trader, the bearer of news from the wider world to his village, who is unsure whether or not to welcome the re-instatement of China’s last emperor.65 At the same time, consistent with its pedagogical impulse, Kahānī also translated older stories by ‘masters of the craft’ like Maupassant, Chekhov, O. Henry, William Saroyan, or Jack London—whose ‘To Build a Fire’ is an ambitious and chilling account of a man freezing to death, told in the first person.66 What are notably absent are European modernist stories by Kafka, Joyce, Woolf, and so on.

The different aims of Kahānī—to look for and showcase new talent in Hindi, to keep abreast of literary developments in other Indian languages, to make visible authors and texts from China, Russia, and Eastern Europe, but also to publish model stories by masters of the craft — translated into different temporalities. Hindi and other Indian stories were overwhelmingly contemporary and experimented with different narrative strategies. By contrast, foreign stories were often older, chosen for their political message or their ‘mastery’. In terms of the ‘literary time’, therefore, Indian stories appear more modern than foreign ones, and only with Chinese stories there seems to be a gesture toward simultaneity.

As for Sārikā, before Kamleshwar took over as editor sometime in 1967, the previous editor Chandragupta Vidyalankar had pursued a similar line to that of Kahānī in the 1950s: half of the stories published were by contemporary Hindi writers, half by contemporary writers in other Indian languages, and one was a foreign story—in his case a mixture of old masters and contemporary European and American authors, including the Italian Alberto Moravia and Mario Tobino, Yiddish-American Sholem Aleichem and Abraham Reisen, Czech Yaroslav Hašek and Ernst Lustig, as well as Carson McCullers (her philosophical 1942 story ‘A Tree. A Rock. A Cloud’).67 While Kamleshwar continued to showcase the European ‘masters’ of the story, he dramatically broadened the field of vision. As I have already suggested, the decision to bunch together foreign texts into bumper special issues rather than dispensing them individually each month, and to include so many more authors and texts from Latin America, Africa, West as well as South-East and East Asia, produced a spectacularly more diverse world literature.

As with Kahānī, geographical (and geopolitical) orientation presented foreign stories from earlier periods as part of the commitment to the present world.68 Already in the ‘Foreign Story Special Issue’ of Naī Kahāniyān (see Table 1), Kamleshwar wrote that he wanted to ‘offer a selection of contemporary stories from nearby and distant countries that could present [readers] with an emotive picture [bhāvātmak tasvīr] of today’s new world’.69 These were specially commissioned translations, he stressed, aimed at filling a knowledge gap, since these were stories from countries ‘we get little or no opportunity to find out about’. Although in fact about a third of the stories (by Quiroga, Borges, Traven) were several decades old, Kamleshwar stressed their contemporaneity:

Most of the stories in this issue are from this decade—they embrace the contemporary sensibility, the sensibility of today’s new world which is showing itself most forcefully through the medium of the short story. In every country something is dying quickly and something is emerging. To recognize the right values in this fast transition and to make them part of one’s art is not easy.70

That this ‘new world’ was the decolonizing world is clear from Kamleshwar’s editorials.71 But instead of choosing between blocs, the magazine included stories from both blocs, and more. The January 1969 issue, for example—whose cover shows a marching multitude (Fig. 3.2, Table 2)—included stories by the American Henry Slaser, the Russian Viktor Kutezky and North Vietnam’s Nguyen Vien Thong, but also by the German Henrich Böll, France’s Alain Robbe-Grillet, the Indonesian Mochtar Lubis, the Iranian Mohammad Hijazi, and so on.

Fig. 3.2 Cover of Sārikā, January 1969 special issue on the world story. Courtesy of the Times of India Archives. All rights reserved.

In his editorial, as already mentioned, Kamleshwar borrows the title of João Guimarães Rosa’s story ‘The Third Bank of the River’ to suggest a literary way out of the ideological polarization and Cold War blocs. While he effectively makes a case for the ‘Global South’, he also uses Rosa’s story to point to the common uncertainty of the human predicament in the contemporary world (I stick to the masculine subject of the original):

In this issue we find the voice [svar] of almost three quarters of the population of the world. There is a clear difference between the voice of developed and of undeveloped countries — the ‘experience’ of the countries of the whole southern half of the globe differs from that of the developed countries. In the former, in the struggle for economic freedom man [ādmī] has become prey to disintegration [vighaṭan], despondency [badhavāsī], lack of values [mūlyahīntā], and cold cruelty. He is smoldering in the fire of history—that others have bestowed on him. And he is aspiring to the chance to start everything anew. He doesn’t like this world. Every country’s face is distorted… every body is growing ulcers.

Meanwhile, whatever the political voice of the great powers—there man is dejected and alone after suffering from the terrors of the War.

These are superficial and bi-dimensional matters, there is a third dimension, extremely delicate and abstract. And very concrete and deep, like the ‘third bank of the river’ in Rosa’s story in this issue. This is the common fundamental voice of all the stories. The voice of the fate of living midstream, tired of both shores.72

As already suggested, while the articulation of colonial difference and commonality among colonized countries aligns Kamleshwar and Sārikā with Third-Worldism, the tenor of the stories and his choice of authors differ considerably from the emphasis on political struggle and the exploitation of labour, and the voices of revolutionaries and committed Leftists in the pages of Lotus. The 1964 special issue of Naī Kahāniyān edited by Kamleshwar, for example, included a titillating story by Horacio Quiroga (‘Three Letters and Footnote’, 1925), Jorge Louis Borges’s philosophical revenge story ‘Emma Zunz’ (1948), and B. Traven’s ironic contemplation of subaltern cleverness ‘Burro Trading’ (originally written in German in 1929). The January 1969 special issue of Sārikā, as we have seen (Table 2), went even further in making Asia, Africa, and the Middle East visible and creating familiarity through paratexts.73 It included stories from political hotspots like Indonesia and North Vietnam, and several from the Arab world, Africa, and Latin America. Yet the stories themselves veered between Ngũgĩ’s famous meditation on the limit of liberal paternalism in ‘The Martyr’ (translated as ‘Deshbhakt’, patriot) and Mahmud Taimur’s sensational first-person narrative of an ordinary man disgusted by his anonymity who courts fame by claiming to be the murderer of a famous actress; João Guimarāes Rosa’s deeply philosophical ‘Third Bank of the River’; Mario Benedetti’s office satire—which could have been written in Hindi by Bhisham Sahni or Amarkant—and Alain Robbe-Grillet’s exercise in description, perception, and surface meaning (‘La Plage’, 1962). The works showcased bely a single definition of Third World literature.

The effect of this spectacular visibility of world literature on readers was tremendous: ‘unique’, ‘very useful and collectible’, ‘the best of all previous special issues’. Readers particularly liked ‘The Third Bank of the River’ (‘a wonderful accomplishment of world literature’), Mochtar Lubis’ story of a farmer tricked out of his fields, and Mahmud Taimur’s piece.74

The January 1973 special issue of Sārikā—rechristened a ‘complete magazine of stories and of the story-world’ (kahāniyon aur kathā-jagat kī sampūrṇ patrikā)—was expressly dedicated to the ‘Third World: ordinary people and writers as fellow travellers’ (tīsrī duniyā: sāmānya jan aur sahyātrī lekhak) and again combined a definition of Third World in terms of postcolonial underdevelopment with an emphasis on decolonization as an intellectual and creative, as well as political and economic, struggle (see editorial above).75 The list of names and texts—thirteen stories (and four folktales) from Africa, eleven from Latin America, a handful of stories from the Middle East and South East Asia, and one from India, by Mohan Rakesh—includes some of the most celebrated names of Latin American and postcolonial literature: Juan Rulfo, Miguel Angel Asturias, José Donoso and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Chinua Achebe, Ngũgĩ, Alex Le Guma, Cyprian Ekwensi, and Pramoedya Ananta Toer (Table 4).76

Table 4 Contents of special issue on the Third World story, Sārikā, January 1973.

Yet not all the stories are about exploitation or colonization or even postcolonial alienation: Mario Benedetti’s ‘Miss Iriarte’ imagines a secretary falling in love with the voice and imagined identity of a woman rather than the person herself; Donoso’s ‘Anna Maria’ is about the tender friendship between a poor gardener and a little girl. Once again, geographical and geopolitical orientations transmute temporality and bring the stories within the common historical and political perspective of the present.

Conclusions

Magazines play a crucial role in literary world-making, this chapter has argued. And often it is the story, a supremely portable genre that can be easily called upon to ‘represent’ a country or a trend, is its currency and unit of exchange. In the context of the Cold War, competing internationalisms—competing ‘significant geographies’ that overlayed ideological fault lines within the Hindi literary field—brought an abundance of stories in translation, and an unprecedented investment on the part of Hindi magazine editors in translating them for their Hindi readers.

How do magazines—ephemeral print objects—produce world literature? Isn’t the considerable investment needed for sourcing and translating texts incommensurate to the time it takes to read and discard a magazine? (And a reason why such intensive bouts of translational activism usually do not last beyond five years.) This chapter has suggested visibility, recursivity, and temporality as categories of analysis, and assessed different kinds of ‘thick’ or ‘thin’ coverage. We saw that the ‘spectacular internationalism’ and textual presence of special issues made world literature (or the literature of the ‘new world’, as Kamleshwar put it) much more visible than having a regular monthly slot. For that, Hindi magazine editors cheerfully sourced material from an abundant print archive provided by competing propaganda programmes. Editors did not dwell on their sources or on translation, but their spectacular internationalism was predicated on the availability of English-language translations produced by China and the Soviet Union as well as American and British magazines, publishers, and state programmes. Nor were the hurdles of translation ever mentioned—and usually nor were the translators, though in some cases they included established Hindi writers like Dharmavir Bharati, Nirmal Varma, or Kamleshwar himself. Rather, the story was a common idiom, and the different languages merely its scripts.

Literary ‘significant geographies’ mapped onto political ones. Editors made some geographies more visible, and some writers and regions recur more often than others. When the scope was extended to include Latin American, African, Middle Eastern, and South East Asian stories, they needed to foster familiarity through helpful paratexts and framing discourses. By contrast, when it came to talk of the ‘masters’ of the story craft—Chekhov or Maupassant, Gorky or Saroyan—familiarity could be assumed and the canon was pretty stable across the ideological checkerboard.

At one level temporality folded within geopolitics—Quest reviewed books on classical Chinese literature and ignored the post-1950 literature of Communist China, making it invisible. But there were grey areas and exceptions in both camps: Lu Xun was universally valued in Hindi magazines of the 1950s, while Kahānī largely published non-political or pre-Communist stories from the Eastern bloc. In the 1970s, in place of the East-West frame of the two blocs, Third-Worldism became a way to broaden and realign the literary gaze, introducing contemporary African, Latin American, and South-East Asian literatures into Hindi to an unprecedented degree. That such a wealth of translated stories became mainstream in a commercial magazine belonging to the Times of India group is even more remarkable. In some cases, as we have seen, the temporal choice seems very deliberate. In others—perhaps unlike magazines such as Soviet Literature or Chinese Literature—a spatial political affiliation expanded across historical periods (Móricz’ story in Kahānī, the earlier Latin American stories in Sārikā). The result could be a mismatch between political orientation and aesthetic choices: for example when Progressive writer K. A. Abbas was asked what Soviet literature he read and he replied, none, because he preferred leftist American writers. When pressed, Abbas speculated that Soviet fiction was less interesting because Soviet society had eliminated all its contradictions!77 In this respect, to argue that magazines in the Cold War era produced a ‘global simultaneity of literary time’ overlooks the phenomenon of the geopolitical transmutation of literary time.

The wide-ranging and stylistically eclectic world literary activism of the special issues of the Hindi magazines Kahānī, Naī Kahāniyān and Sārikā is very impressive—I don’t see a parallel in European magazines, or even those oriented towards the world like Sur or The Paris Review.78 Arguably, the propaganda and counter-propaganda efforts of the Cold War produced an expanded literary internationalism and showed interest in, translated, and made available vast repertoires of literary texts. But it was the literary activism of Hindi editors like Kamleshwar that increasingly made them pick out stories from Third World literatures from that archive and translate them into Hindi. This literary Third-Worldism, if we call it that, was different and more aesthetically eclectic than the idea of progressive literature in Hindi. It spoke rather to a reorientation away from the Western and Eastern blocs and a curiosity to discover what literatures lay behind the term Third World. From our current perspective in the age of global Anglophone, it is ironic that the decline of ‘magazine activism’ in search of stories to translate may well be one of the unintended consequences of the end of the Cold War.

Is the experience of world literature in an ephemeral medium like the magazine different from that of the book series, the anthology, the course, or canonization through prizes? Did the magazine issues that brought Ngũgĩ, Achebe, Le Guma, Guimarães Rosa, Rulfo, Garcia Marquez, Ananta Toer, and many others to Hindi readers in the 1960s and 1970s leave a lasting impression? Particularly since, unlike original stories in Hindi, translated stories only very rarely got a second, more extended life in book form? Terms like ‘collectible’ issue or ‘unforgettable’ story suggest that stories in magazines could leave a mark. When I read in Hindi author Gyanranjan’s memoir of studying in Allahabad in the 1950s that he read Osamu Dazai, I imagined he had done so in English. But coming across two stories by Dazai in Naī Kahāniyān and Sārikā, I now wonder.

Bibliography

Abbas, Khwaja Ahmad, ‘Abbās: vyaktitva aur kalā’ (Abbas: personality and art) in Mujhe kuchh kahnā hai, ed. by Zoya Zaidi (New Delhi: Rajkamal Prakashan, 2017).

—, ‘Alif Lailā 1956’, Kahānī, October 1956, pp. 24–36.

Antonov, Segei, ‘Kahānī ke sambandh men’ (About the story), Nayā Path, January 1954, pp. 281–87.

Baldwin, Dean, Art and Commerce in the British Short Story, 1880–1950 (London: Routledge, 2013).

Bano, Jilani, ‘Ek hazār ek romans’, Kahānī, March 1954, pp. 12–18.

Bharati, Dharmavir, Pragativād: Ek Samīkshā (Prayag: Sahitya Bhavan, 1949).

Bradford, Louisa Rose, ‘The agency of the poets and the impact of their translations: Sur, Poesía Buenos Aires, and Diario de Poesía’ in Agents of Translation, ed. by John Milton and Paul Bandia (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2009), pp. 229–56.

Brouillette, Sarah, ‘US–Soviet Antagonism and the ‘Indirect Propaganda’ of Book Schemes in India in the 1950s’, University of Toronto Quarterly 84.4 (2015), https://doi.org/10.3138%2Futq.84.4.12

Bulson, Eric, Little Magazine, World Form (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

Chaudhuri, Amit, Literary Activism: Perspectives (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Damrosch, David, What is World Literature? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003).

David Damrosch, ed., Teaching World Literature (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2009).

Halim, Hala, ‘Lotus, the Afro-Asian Nexus, and Global South Comparatism’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 32.3 (2012), https://doi 10.1215/1089201x-1891570

Holt, Elizabeth, ‘“Bread or Freedom”: The Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA and the Arabic Literary Journal Ḥiwār (1962–1967)’, Journal of Arabic Literature 44 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1163%2F1570064x-12341257

Imbert, Enrique Anderson, ‘Spanish-American Literature in the Last Twenty-Five Years’, Books Abroad, 27.4 (1953): 341–58.

Jalal, Ayesha, The Pity of Partition: Manto’s life, times, and work across the India-Pakistan divide (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013).

Jia, Yan. ‘Beyond the ‘Bhai-Bhai’ Rhetoric: China-India Literary Relations, 1950–1990’, unpublished doctoral thesis, SOAS, University of London, 2019.

Kahānī, ‘Kahānī ki bat’, May 1955, p. 4.

Kamleshwar, Editorial, Sārikā, January 1973, p. 6.

—, Editorial, ‘Donon taṭon se ūbkar’ (Tired of both Shores), International special issue (Deshāntar aṅk), Sārikā, January 1969, p. 7.

—, ‘Kuch bāten’ (A few words), Naī Kahāniyān, May 1964, n.p.

—, ‘Manushya ke astitva aur jīvan-mūlyon kī khoj men indoneshiyā kī kahānī’ (In search for human existence and life values: the Indonesian story), Sārikā, March 1966, pp. 81, 83, 91.

—, ‘Misr kī samkālīn kahānī: bhūmadhyasāgarīy saṃskriti kī khoj’ (The Contemporary Egyptian Story: in search of Mediterranean culture), Sārikā, January 1966, pp. 33–35, 82.

—, ‘Vishva-kathā-yātrā: jal-pralay se anu-pralay tak’ (The journey of the world story: from the deluge to the atom bomb), Sārikā, January 1970, pp. 44–48.

Kantor, Roanne, South Asian Writers, Latin American Literature, and the Unexpected Journey to Global English (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).

Kenyatta, Jomo, ‘Hāthī aur ādmī (Elephant and Man), trans. by Jagatbahadur Joshi, Kahānī, May 1955, 56–57.

Komey, Ellis Ayitey and Es’kia Mphahlele, eds, Modern African Stories (London: Faber and Faber, 1964).

Ku-Yu, ‘Nayā Yug’ (New Age), trans. by Satish, Kahānī, October 1955, pp. 65–69.

Laachir, Karima, Sara Marzagora and Francesca Orsini, ‘Significant Geographies: In lieu of World Literature’, Journal of World Literature 3.1 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1163/24056480-00303005

London, Jack, ‘Āg’ (Fire), trans. by Vishvamohan Sinha, Kahānī, July 1956, pp. 63–71.

Mandhwani, Aakriti, ‘Everyday Reading: Commercial Magazines and Book Publishing in Post-Independence India’, unpublished doctoral thesis, SOAS, University of London, 2018.

Mani, Preetha, ‘What Was So New about the New Story? Modernist Realism in the Hindi Nayī Kahānī’, Comparative Literature, 71.3 (2019), http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/amnd-ap31

Mani, Venkat B., Recoding World Literature: Libraries, Print Culture, and Germany’s Pact with Books (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017).

Morgan, Ann, Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer (London: Random House, 2015).

Moretti, Franco, Distant Reading (London: Verso, 2013).

Móricz, Zsigmond, ‘Seven Pennies’ (Sāt peniyān), trans. by Bhairavprasad Gupta, Kahānī, March 1954, pp. 38–41.

Orsini, Francesca, ‘Beyond the Two Shores: Indian Magazines and World Literature between Decolonization and the Cold War’, LINKS/IMLR Seminar (26 November 2020), https://modernlanguages.sas.ac.uk/events/event/23336

—, The Hindi Public Sphere: Language and Literature in the Age of Nationalism, 1920–1940 (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002).

—, ‘Present Absence: Book Circulation, Indian Vernaculars and World Literature in the Nineteenth Century’, Interventions 22.3 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2019.1659169

—, ‘World literature, Indian views, 1920s-1940s’, Journal of World Literature 4.1 (2019), doi:10.1163/24056480-00401002

Popescu, Monica, At Penpoint: African Literature, Postcolonial Studies and the Cold War (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2020).

Pravinchandra, Shital, ‘Short story and peripheral production’ in The Cambridge Companion to World Literature, ed. by B. Eherington and J. Zimbler (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 197–210.

Premchand, Ṭālsṭāy kī kahāniyān (Tolstoy’s Stories), Allahabad: Hans Prakashan, 1980.

Pushkal, Ajit, ‘Kamleshwar: chintan, patrakāritā aur sampādan ke sandarbh men’ in Kamleshwar, ed. by Madhukar Singh (Delhi: Shabdakar, 1977), pp. 329–342.

Rai, Amrit, Letter to the editor, Kahānī, May 1954, pp. 52–54.

—, ‘Sāṃskritik svādhīntā ke ye ālambardār’ (These standard bearers of cultural freedom/independence), Kahānī, July 1957, pp. 72–77.

Roadarmel, Gordon, ‘The theme of alienation in the modern Hindi short story’, unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California at Berkeley 1969.

Rubin, Andrew, Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

Sahityakar, ‘A Window into HindiWriting’, Illustrated Weekly of India (1 April 1962), p. 49.

Sapiro, Gisèle, Traduire la littérature et les sciences humaines: Conditions et obstacles (Paris: Ministère de la Culture – DEPS, 2012).

Sārikā, Readers’ letters, March 1969, pp. 6–7.

Schomer, Karine, Mahadevi Varma and the Chhayavad Age of Modern Hindi Poetry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983).

Shih, Shu Mei, ‘Global literature and the technologies of recognition’, PMLA, 119.1 (2004), 16–30.

Whitehead, Sarah, ‘Edith Wharton and the Business of the Magazine Short Story’ in The New Edith Wharton Studies, ed. by J. Haytock & L. Rattray (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), https://www.doi.org/10.1017/9781108525275.004

Yeh, Chun Chuan, ‘Khwāb’ (Dream), trans. by Vishnu Sharma, Kahānī, January 1955, pp. 302–309.

Xun, Lu, ‘Havā kā rūkh’ (Where the Wind Blows), trans. by Kamleshwar, Kahānī March 1954, pp. 27–32.

Zecchini, Laetitia, ‘Practices, Constructions and Deconstructions of ‘World Literature’ and ‘Indian Literature’ from the PEN All-India Centre to Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’, Journal of World Literature, 4.1 (2019), https://brill.com/view/journals/jwl/4/1/article-p82_5.xml

—, ‘What Filters Through the Curtain: Reconsidering Indian Modernisms, Travelling Literatures, and Little Magazines in a Cold War Context’, Interventions, 22.2 (2020), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1369801X.2019.1649183

1 Written in 1954 (Ayesha Jalal, The Pity of Partition: Manto’s life, times, and work across the India-Pakistan divide, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013, p. 122), ‘Ṭoba Ṭek Singh’ was published in book form in Urdu in 1955 (in Phundne, Lahore: Maktaba-e Jadid), the year Manto that died. The story therefore appeared in print at the same time in Urdu and Hindi and on both sides of the border.

2 Chun Chuan Yeh’s ‘Dream’ is a story about a young man who falls in with a family of performers in war-torn China; according to Jia Yan, this could be Chun-chan Yeh or Ye Junjian; I thank him for the suggestion.

3 As Yan Jia’s chapter in this volume shows, the rhetoric of ‘Hindī-Chīnī bhāī bhāī’ (Indian and Chinese are brothers) was at its peak in the 1950s.

4 Amit Chaudhuri, Literary Activism: Perspectives (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2017).

5 See Eric Bulson, Little Magazine, World Form (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

6 See Francesca Orsini, The Hindi Public Sphere: Language and Literature in the Age of Nationalism, 1920–1940 (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002).

7 See Aakriti Mandhwani, ‘Everyday Reading: Commercial Magazines and Book Publishing in Post-Independence India’ (unpublished doctoral dissertation, SOAS, University of London, 2018).

8 See also Dean Baldwin, Art and Commerce in the British Short Story, 1880–1950 (London: Routledge, 2013); Sarah Whitehead, ‘Edith Wharton and the Business of the Magazine Short Story’ in The New Edith Wharton Studies, ed. by J. Haytock & L. Rattray (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 48–62.

9 Chandragupta Vidyalankar, Editorial, Sārikā, November 1966, p. 93. See also Kamleshwar’s essay, ‘The journey of the world story: from deluge to atomic explosion’ (‘Viśva-kathā-yātrā: jal-pralay se aṇu-pralay tak’), Sārikā, January 1970, pp. 44–48, which traces the development of the story (more or less loosely, as fiction and as short story) from Gilgamesh to Beckett. The fact that stories are found at the beginning of every culture, whether in Egypt, Mesopotamia, China or India, may have mitigated any anxiety about the modern short story being an imported ‘western’ form; I thank Neelam Srivastava for this suggestion.

10 See Premchand’s early discussion of the genre in ‘Kahānī-kalā’ (The Art of the Story), reprinted in Premchand, Kuch vichār (Some Thoughts) (Allahabad: Saraswati Press, 1965).

11 See Mandhwani, ‘Everyday Reading’.

12 Ibid.

13 Whether translations from other Indian languages figured as prominently in magazines in other bhasha fields is an interesting question for Indian comparatists. Usually the main institutional actor in this regard is understood to have been the Indian Academy of Letters (Sahitya Akademi, 1957), which launched a translation programme (with English as the medium when no direct translator was available) and an English and a Hindi magazine (Indian Literature and Samkālīn sāhitya or Contemporary Literature). As this essay shows, Hindi magazines from the 1950s to 1970s were equally important actors.

14 Laetitia Zecchini, ‘What Filters Through the Curtain: Reconsidering Indian Modernisms, Travelling Literatures, and Little Magazines in a Cold War Context’, Interventions, 22.2 (2020), 172–94 (p. 177).

15 Russian stories by Tolstoy and Chekhov were already familiar to Hindi readers; Premchand himself had translated some Tolstoy stories in 1923 (reprinted as Premchand, Ṭālsṭāy kī kahāniyān, Allahabad: Saraswati Press, 1980).

16 See Karima Laachir, Sara Marzagora and Francesca Orsini, ‘Significant Geographies: In lieu of World Literature’, Journal of World Literature, 3.1 (2018), 290–310.

17 Kamleshwar, Editorial, Sārikā, January 1973, p. 6. He viewed this special issue as a direct continuation of two earlier issues dedicated to Indian stories about the inner and mental world of ordinary Indians (ibid.). All translations from Hindi are mine.

18 Kamleshwar, ‘Donon taṭon se ūbkar’ (Tired of both Shores), Sārikā, January 1969, p. 7.

19 Elizabeth Holt, ‘“Bread or Freedom”: The Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA and the Arabic Literary Journal Ḥiwār (1962–1967)’, Journal of Arabic Literature, 44 (2013), 83–102 (p. 89), emphasis added, quoting Andrew Rubin, Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), p. 58.

20 Kamleshwar, ‘Donon taṭon se ūbkar’, p. 7.

21 Roanne Kantor, South Asian Writers, Latin American Literature, and the Unexpected Journey to Global English (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).

22 See my webinar ‘Beyond the Two Shores: Indian Magazines and World Literature between Decolonization and the Cold War’, https://modernlanguages.sas.ac.uk/events/event/23336

23 For Lotus, see Hala Halim, ‘Lotus, the Afro-Asian Nexus, and Global South Comparatism’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 32.3 (2012), 563–83; and Monica Popescu, At Penpoint (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2020).

24 For the term ‘bibliomigrancy’, see B. Venkat Mani, Recoding World Literature: Libraries, Print Culture, and Germany’s Pact with Books (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017). These stories did not become part of the Index Translatiorum and would not therefore register in studies like Gisèle Sapiro’s Traduire la littérature et les sciences humaines: Conditions et obstacles (Paris: Ministère de la Culture – DEPS, 2012).

25 I am referring here to the Hindi and English literary spheres; accounts of other Indian regional language fields would feature different magazines and publishers.

26 By far the most popular film magazine of the time was, however, the Urdu Shamā’, published from Delhi.

27 ‘Sahityakar’ (i.e. ‘Literato’ in Hindi), ‘A Window into Hindi Writing’, Illustrated Weekly of India, 1 April 1962, p. 49.

28 For a brief account of these debates in English, see Karine Schomer, Mahadevi Varma and the Chhayavad Age of Modern Hindi Poetry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983). There were several attempts at mediation: for example, poet and future Dharmayug editor Dharmavir Bharati tried to argue that Marxism itself was not a dogma but a sweeping ‘experiment’ of human civilization with progress, beneficial but and not without its weaknesses; Dharmavir Bharati, Pragativād: ek samīkshā (Progressivism: a review) (Prayag: Sahitya Bhavan, 1949), p. 2. I thank Xiaoke Ren for this reference.

29 As Zecchini shows, the Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom brought together both right and left critics of Nehru and of the Communists, so non-Communist Congress Socialists (JP Narayan, Narendra Dev, Minoo Masani) and the Congress Right (K.M. Munshi), who opposed both the Communist takeover of cultural and labour organizations and the ‘one-party’ rule of Nehru’s Congress.

30 Amrit Rai, ‘Sāṃskritik svādhīntā ke ye ālambardār’ (These standard bearers of cultural freedom/independence), Kahānī (July 1957), p. 75. ‘We are in favour of the writer’s freedom-relative-to-society [samāj-sāpeksh svādhīntā] and consider any kind of socially unrelated solitary freedom [samāj-nirpeksh, ekāntik svādhīntā] a synonym of derangement [ucchrinkhaltā]’; ibid., p. 76.

31 See Xiaoke Ren, ‘The Interface Between Literature and Ideology in Post-Independence India: Hindi Progressive Novels of the 1950s and 1960s’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, SOAS, University of London, in progress).

32 For example, the Progressive/Communist magazine Nayā Path published, in lieu of feedback to budding writers, a three-part series ‘About the story’ (Kahānī ke sambandh men) by Soviet writer Sergei Antonov (Nayā Path, January 1954, pp. 281–287). Nayā Path also printed articles about Gorky, Nazim Hikmet, and one by Pablo Neruda condemning obscurity in poetry (‘Kavitā aur aspashṭtā’, Nayā Path, May 1954), pp. 466–468. For Chinese publications in India, and especially in Hindi, see Jia, ‘Beyond the “Bhai-Bhai” Rhetoric’: China-India Literary Relations, 1950–1990’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, SOAS, University of London, 2019).

33 See Mandhwani, ‘Everyday Reading’.

34 See Preetha Mani, What Was So New about the New Story? Modernist Realism in the Hindi Nayī Kahānī’, Comparative Literature, 71.3 (2019), 226–51.

35 See e.g. Teaching World Literature, ed. by David Damrosch (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2009); Mani, Recoding World Literature.

36 See Shu-Mei Shih, ‘Global literature and the technologies of recognition’, PMLA, 119.1 (2004), 16–30.

37 I differentiate here between textual presence (translation, i.e. when the literary text is there) and textual closeness, which usually includes translation with some apparatus. I understand that some readers (like Ann Morgan, Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer, London: Random House, 2015) find contextualization intrusive, while for other readers like myself it is necessary in the case of unfamiliar texts and literary traditions. While Franco Moretti has advocated ‘distant reading’ as a critical practice, i.e. reading patterns and secondary rather than primary texts, I use it here for magazines which provide information about texts and writers without the texts/translation themselves: as the examples below show, this information can be ‘thin’ (e.g. Modern Review) or ‘thick’ (e.g. Kalpanā). See Franco Moretti, Distant Reading (London: Verso, 2013).

38 This is the impression one gets from world literature surveys that included Indian literature only among ancient literatures; see my ‘Present Absence: Book Circulation, Indian Vernaculars and World Literature in the Nineteenth Century’, Interventions, 22.3 (2020), 310–28.

39 See my ‘World literature, Indian views, 1920s–1940s’, Journal of World Literature, 4.1 (2019), 56–81, and Zecchini in this volume.

40 The Greek Lafcadio Hearn for China (Caravan, September 1950); American Konrad Bercovici for Arabia (November 1950); Canadian Charles Roberts for Turkey (May 1951).

41 The first issue of Yugchetnā (January 1955) included an article on ‘China’s cultural tradition’ and another on Henry James, while the editorial quoted Toynbee and Spengler. Later issues featured articles on ancient Greek theatre, Sappho, modern Chinese poetry, Dante, Disraeli, Benjamin Constant, E. M. Forster on the novel, Existentialism, Herbert Read, T. S. Eliot, André Gide, etc.

42 E.g. Quest, 17 (April–June 1958); 38 (July–September 1963), 43 (October–December 1964).

43 Enrique Anderson Imbert, ‘Spanish-American Literature in the Last Twenty-Five Years’, Books Abroad, 27.4 (1953), 341–58, translated in Kalpanā, April 1958, pp. 62–88.

44 Or reference to where they were taken from! All translations were from English.

45 As editor of Naī Kahāniyān, Kamleshwar also promoted new voices in Hindi with three special issues on ‘New writers’, see Ajit Pushkal, ‘Kamleshwar: Chintan, patrakāritā aur sampādan ke sandarbh men’ (Kamleshwar: in the context of editing, journalism and thought), in Kamleshwar, ed. by Madhukar Singh (Delhi: Shabdakar, 1977), p. 337.

46 Kamleshwar, ‘Misr kī samkālīn kahānī: bhūmadhyasāgarīy saṃskriti kī khoj’ (The Contemporary Egyptian Story: in search of Mediterranean culture), Sārikā, January 1966, p. 35.

47 Kamleshwar, ‘Manushya ke astitva aur jīvan-mūlyon kī khoj men indoneshiyā kī kahānī’ (In search for human existence and life values: the Indonesian story), Sārikā, March 1966, p. 83.

48 Gordon Roadarmel’s pioneering study, ‘The theme of alienation in the modern Hindi short story’ (unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California at Berkeley, 1969) identified ‘alienation’ as their key theme and drew up a rather rigid dichotomy between tradition and modernity. More recently, Preetha Mani has offered a more nuanced interpretation that views New Short Stories as engaged in nation-building through their emphasis on individuals and the ‘truth of inner experience’ (anubhūti kā satya), love, family and work relationships, and the commitment to register the ‘new circumstances’ (naī paristhitiyān) of post-1947 urban India; Mani, ‘What Was So New’.

49 Amrit Rai, letter, Kahānī, May 1954, pp. 52–53.

50 See Kahānī, September 1956, pp. 70–73.