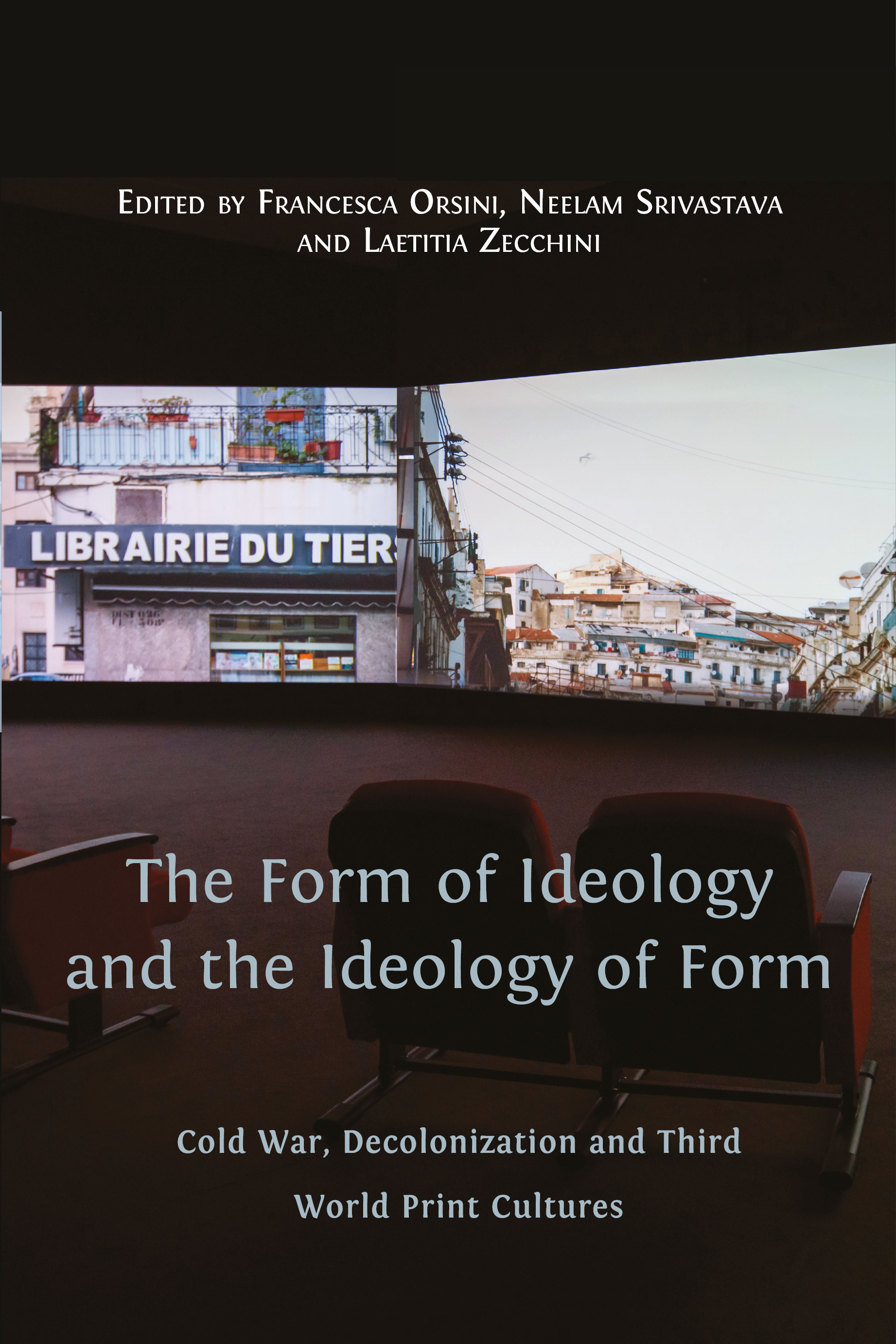

5. The Meanings, Forms and Exercise of ‘Freedom’: The Indian PEN and the Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom (1930s–1960s)1

© 2022 Laetitia Zecchini, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0254.05

Again and again, that question: to be free. What did it mean?

Introduction

This chapter focuses on two organizations many Indian and world writers have been associated with over the years: the PEN All-India Centre, founded in 1933 in Bombay as the Indian branch of International PEN (the ‘world association of poets-playwrights-editors-essayists-novelists’ started in London in 1921), and the Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom (ICCF), founded in 1951 in the aftermath of the first Asian conference convened in Bombay by the Congress for Cultural Freedom (an organization established a year earlier in Berlin to put forward ‘a rival ideology to Communism’).2 Although started in very different contexts, these organizations belong to a similar ideological constellation and highlight the need to recover the largely overlooked lineage of liberalism both for anticolonial and post-colonial struggles, and for an understanding of modernisms in India.

The PEN All-India Centre and the ICCF have been largely subsumed under more mainstream narratives of South Asian literary history, decolonization and the Cold War, yet they offer fascinating examples of the interconnectedness of local and international print cultures, and of particular histories that were world histories as well.3 As Indian branches of two international organizations, they both championed internationalism and acted as platforms where specific concerns were articulated and where many Indian writers wrestled with the meanings, the forms and the practice of ‘freedom’.

Drawing on the conference proceedings of these two organizations, on their journals (especially Quest and The Indian PEN), and on the form of the critical essay through which Indian writers exercised their critical and creative freedom and cultivated their individuality, this chapter attempts to excavate alternative lineages of decolonization, and of struggles for cultural freedom in India which intersected with the anticolonial freedom struggle in the 1930s and 1940s; with a liberalism that was partially defined by the anti-communist cultural front in the 1950s, and with modernist ventures in the 1950s–1960s and beyond. If modernism is an important part of this history, it is in part because the struggles over the implications of the notion of ‘freedom’, which became the central catchword enlisted by the United States to rally against communism, were also struggles over the meanings and forms of ‘modernism’ (turned into a political weapon by the ‘free world’ in a campaign against ‘social realism’). The interplay between the liberal and modernist lineages is perhaps best embodied in a writer like Nissim Ezekiel, modernist Bombay poet par excellence, prolific critic,4 prominent figure of the PEN All-India Centre and the ICCF, and editor of a constellation of literary and cultural magazines after Independence, including The Indian PEN (henceforth TIP), and two ICCF-sponsored journals, Quest and Freedom First.

‘Again and again, that question: to be free. What did it mean?’, wrote Nissim Ezekiel trying to recollect his state of mind in 1947.5 Since Ezekiel tirelessly explored the meanings or possibilities of (political, cultural, literary and critical) ‘freedom’, and championed it against its many (local and international) opponents, I often return to him in the following pages. His question is also the one I want to raise here. Like Ezekiel, who was a strikingly complex voice, weary of ‘closed systems’ (his words) and predictable alignments, many of the figures I discuss below, whose (at times sinuous) cultural, ideological and political trajectories spanned more than 40 years of a tumultuous Indian political history, are difficult to pigeonhole. Some were anticolonial conservatives, like the founder of the Indian PEN, Sophia Wadia; others were liberal Third-Worldists or ex-Marxists who became anti-communists; freedom fighters who viewed their anti-communism as continuous with their anticolonialism (like Jayaprakash Narayan, Socialist and prominent member of the ICCF); or modernists who can barely be defined as experimentalists, like Nissim Ezekiel.

While acknowledging the fluidity of a term that took on many hues, from the Freedom Struggle to the post-colonial period where ‘freedom’ also became a liberal credo and a modernist anthem, I would like to examine what freedom meant for the writers engaged in the PEN and the ICCF. In his seminal text ‘The Essay as Form’, Adorno takes advantage of the generic hybridity of the essay (which is both creative and scholarly, in the sense that its form cannot be dissociated from its content) to argue that the essay does not obey the rules of objective discipline, but reflects a ‘childlike freedom’ in mirroring what is loved and hated.6 Essayists try out their likes and dislikes, and shy away from the violence of dogma. That’s also why Adorno equates the essay, by virtue of being the experimental and the critical form par excellence, with the ‘critique of ideology’. Many of the essays (understood comprehensively to include editorials and reviews) that I discuss below illustrate this unapologetically subjective, experimental and anti-dogmatic (even anti-ideological) disposition. They not only reflect the variety of the debates that were happening at the time, but offered writers a forum for critical dialogue with other writers and readers; a platform to articulate their concerns, their anxieties, and sometimes their ‘uncertain certainties’ (to take up the title of a column by Nissim Ezekiel);7 and a form to exercise their freedom, and tease out its varied meanings.

For the PEN All-India Centre, literature was a means of political independence, and ‘freedom’ was defined as freedom from colonial servitude. In its publications, political freedom and cultural/literary freedom are seen as inseparable, and the ‘forms’ of freedom were also the forms of a unified, institutionalized and easily identifiable ‘Indian literature’. But what did ‘freedom’ imply and what forms did it take, once India’s Independence had been attained? The question, in the 1950s and 1960s, was a pressing one—both in the immediate post-colonial context marked by widespread disillusionment with the promises of independence, and in a more global context at the height of the Cold War, when the significance and implications of ‘freedom’ (and the rights over it) were intensely scrutinized and debated, and India, like many other parts of the world, was subjected to the ‘competitive courtship’ (Margary Sabin) of the United States and the Soviet Union. The Hindi writer Mohan Rakesh could even talk about his country as a chessboard between United States and USSR’s ideologists.8

A specific illustration of this struggle over the definition, ownership and boundaries of ‘freedom’ in the 1950s may be useful here. At the inaugural 1951 ICCF conference in Bombay, Denis de Rougemont argued that the only way to defend intellectual freedom and liberty of thought was to become ‘vigilant watchmen and guardians of the true meaning of words’.9 He also recounted a simplistic parable involving three characters: the ‘shepherd’ (the United States); the wolf (the Communists), and the ‘lamb’ (India), who could—providing it did not ‘refuse to take sides’—be saved from the predator’s appetite. Not only was Rougemont’s speech a clear indictment of (India’s) neutrality, but it constructed ‘freedom’ as the property of the liberal West, and claimed the right both to teach the non-West the road to ‘freedom’ and to define who was free and who wasn’t.

Yet, if ‘cultural freedom’ was no doubt a rallying cry of the CCF and its affiliated organizations, in India it was never limited to an anti-communist or anti-Soviet slogan—nor were Indian writers who participated in some of these liberal ventures mere pawns of the Americans.10 As the publications of the ICCF demonstrate, not only did many Indian intellectuals refuse to be taught the road to a ‘freedom’ they had not defined, but they identified many enemies of cultural freedom other than communism. These variously included the neo-imperialism of the ‘free world’; the so-called ‘indigenous’ traditions of inequality and authoritarianism, which the Kannada writer D. V. Gundappa identified in 1945 with an ‘enormous mass of social conservatism’;11 dependence on foreign ideologies or models, including aesthetic ones; the regimentation of culture by an over-powering central state, or the absence of a vibrant, plural, even irreverent critical culture, and of publishing spaces where this culture could flourish. Hence, while the Indian PEN emphasized ‘unity’, many intellectuals affiliated with the ICCF emphasized difference or disagreement.

In his article ‘Poetry in the Time of Tempests’, Nissim Ezekiel acknowledged that part of the answer to his pressing question (To be free: ‘what did it mean?’) came to him during the National Emergency (1975–1977) imposed by Indira Gandhi, which taught him that freedom was never to be taken for granted: ‘Even in Independent India, we would always have to be on the alert for the insidious ways in which those in power try to suppress the inconvenient voices from the margin, the angry voices of the dispossessed and even the quiet voice of poetry’.12 Although both the Emergency and current threats to cultural freedom in India fall outside the scope of this chapter, they nonetheless provide the backdrop against which it must be read. Limits to free speech and censorship are, as I suggest below, important concerns of the two organizations, and some of the struggles for cultural freedom waged from the 1930s up to the 1960s throw light or foreshadow the present struggles by Indian writers and activists to resist the ‘chill on India’s public sphere’.13 That is also why, following Amanda Anderson, it is indeed possible to reconsider liberalism as ‘a situated response to historical challenges’, such as communism and Nazism in a global context, along with all the other forces of fascism, repression and authoritarianism in India itself, including of course colonialism before independence.14

The articulation between politics and literature will be another guiding thread. To a certain extent, the ‘dilemma’ of many of the writers involved in these two organizations was how to liberate forms from ideologies and reconcile political and cultural activism while preserving literature from politics, at a time when both ‘literature’ and ‘freedom’ were deeply politicized. This may also be one of the central questions of post-colonial modernisms: restoring the poetics of freedom against ideological or political instrumentalizations, but without upholding an ‘illusion of the literary world outside of politics’.15 In postcolonial India, this could also mean freeing the project and practice of modernism from recuperation by the West, in order to craft forms and idioms one could recognize as one’s ‘own’.

Literature in the Freedom Struggle: The PEN All-India Centre

Born in the international interwar culture of pacifism, PEN championed the ‘ideal of one humanity living in peace in one world’ and considered that the unhampered circulation of literature and the promotion of mutual understanding between world writers served the cause of world peace: ‘literature knows no frontiers’ and must remain ‘common currency’ in spite of political upheavals, its Charter states.16 The Indian PEN, whose All-India branch was founded by the Colombian-born Theosophist Sophia Wadia, with Rabindranath Tagore as its first president and Sarojini Naidu and S. Radhakrishnan as vice-presidents, was officially created to bridge divisions between Indian literatures, and between India and the world. ‘How many among the litterateurs of different vernaculars know each other?’ and ‘What does the world know of the work?’17—this dual agenda was always translational, with translation promoted both as a means of nation-building and a means of internationalism. Redressing the invisibility of India (and of ‘Indian literature’) on the world stage was also meant to assert India’s eminence on a par with other world cultures and literatures. Hence, to the question raised by the title of the editorial (‘Why a Pen Club in India?’) a defiant rejoinder is provided: ‘Why not? Are Indian writers not good enough to take their place in the fellowship of the world’s creative minds?’18

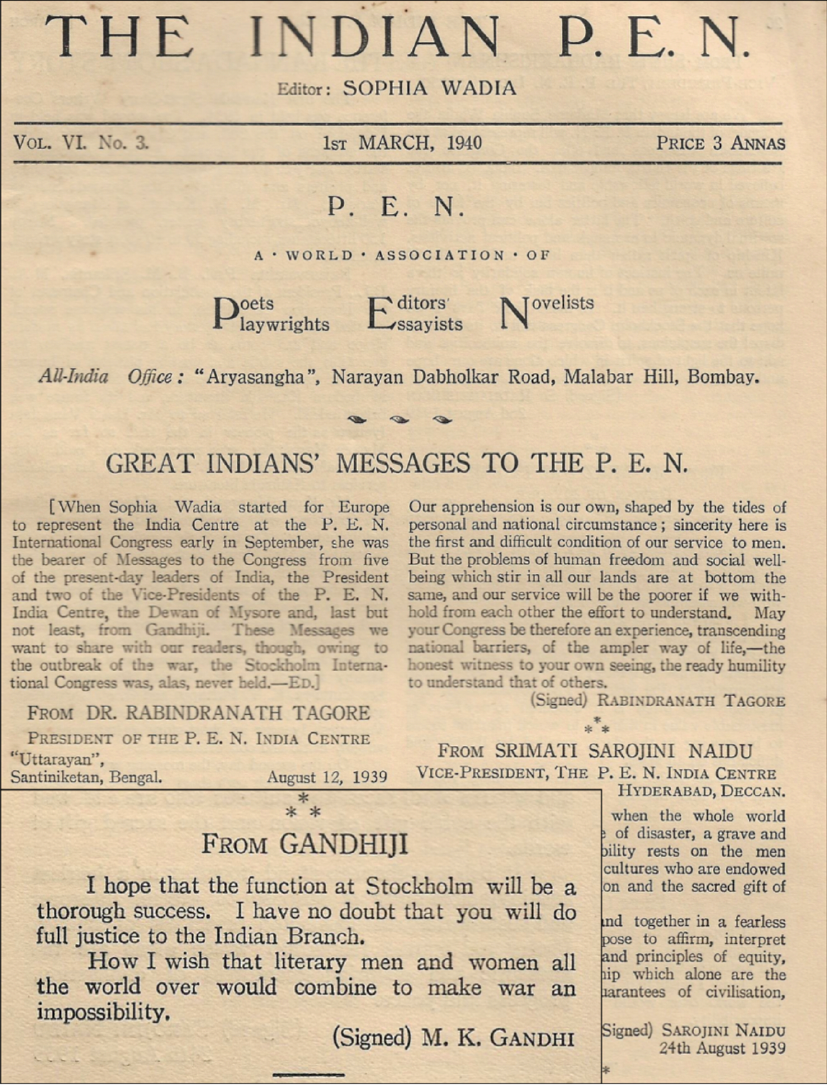

Although PEN asserted that it stood above state or party politics, it was premised on the agency of literature, both on the international and the ‘national’ stages, and one of its foremost concerns in the 1920s and 1930s was to prevent another world war: ‘The writers of a country wield greater power than its lawmakers […] our PEN organization is an instrument better fitted to achieve where the League of Nations has failed’ claimed Sophia Wadia in a speech delivered on ‘PEN’s Ideals and Aims’.19 In a 1940 issue of TIP which carried ‘Great Indians’ Messages’ to the International Congress scheduled in Stockholm (and subsequently cancelled by the outbreak of the war), Gandhi called upon writers to ‘combine to make war an impossibility’ (See Fig. 5.1), while Tagore urged writers to transcend national barriers and realize that the ‘problems of human freedom […] which stir in all our lands are at bottom the same’.20

Fig. 5.1 Great Indians Message to the PEN (TIP, March 1940). Courtesy of the PEN All-India Centre.

But if the problems of human freedom were the same everywhere, India was obviously waging its own freedom struggle. Anticolonialism was in fact the backdrop for many of PEN’s activities in the 1930s and 1940s. Exalting the worth of Indian literature, which was time and again described as the ‘mirror’ or the ‘pulse’ of national life, was meant to serve the cause of political independence. Since, in the words of Sophia Wadia herself, ‘swaraj’ could not be attained through political action alone, writers were called upon as the builders and architects of the nation-to-be.21 The Indian PEN’s first objective was to establish an ‘Indian literature’ that was both recognizable and indivisible. Political freedom, many editorials suggested, could never be granted to a country that did not speak in a single voice, that was divided, inchoate, or ‘inarticulate’. Strong cultural unity was ‘a categorical imperative for India if our national aspirations are ever realized’.22 Several literary forms, genres and programmes were established to articulate these aspirations, and bridge barriers between Indian writers, readers and publics: The Indian PEN monthly; the All-India Writers’ Conferences organized periodically in different parts of India; the anthologies of translated regional literatures whose forewords written by Sophia Wadia opened with the line ‘India’s ruling passion is for freedom from foreign domination’;23 projects for an all-India encyclopedia and for an Indian academy of letters (later institutionalized with the founding of the Sahitya Akademi in 1954); and literary awards in India. All these different proposals are seen (and each word is significant) as ‘potent forces for the establishment on a firm footing of modern India’s claims to eminence’.24 If the ‘Development of the Indian literatures as a Uniting Force’ was the theme chosen by the Indian PEN to convene the first All-India Writers’ Conference in 1945, ‘uniting force’ and ‘national force’ could therefore be used interchangeably: ‘In literature everything depends on how much freedom there is to function. […] Lack of political freedom comes in the way of all progress’, proclaimed Jawaharlal Nehru, also one of the vice-presidents of the Indian PEN at the time.25 And in a telling reference to the French resistance, Mulk Raj Anand acknowledged: ‘as intensely as the resistance movement in France […] we do hunger for and suffer for freedom’.26 The fight for liberty appeared as worthy—and as imperative—in India, as it did in France under Nazi rule. In the eyes of Mulk Raj Anand, fascist repression and colonial repression commanded the same resistance. It is a parallel he had actually drawn with uncompromising vigour in an influential earlier essay on ‘The Progressive Writers’ Movement’ (1939) of which he was a foundational member:

We, the writers of India, know how the forces of repression and censorship have thwarted the development of a great modern tradition in the literatures of our country; we saw the ugly face of Fascism […] earlier than the writers of the European countries, for it was British Imperialism which perfected the method of the concentration camp, torture and bombing for police purposes which Hitler, Mussolini and the Japanese militarists have used so effectively later on.27

The Progressive Writers’ Association, which was the only other pan-Indian writers’ organization at the time, championed a much ‘more revolutionary ideology in all spheres’28 than Wadia’s organization, and attacked the spiritualism, idealism and elitism of culture and literature—which are inescapable features of the Indian PEN.29 The PWA was founded in the aftermath of the storm created by the collection Angare (banned for obscenity in 1933) by a group of writers who refused to ‘submit to gagging’, and challenging literary censorship (both from colonial authorities and religious conservatives) was an explicit part of its agenda.30 Yet, if the PEN was a more conservative organization in terms of class, caste, and literary and political sensibility31 (social justice, for instance, was never one of its concerns), the two writers’ collectives shared prominent members (such as Mulk Raj Anand, Premchand, Ahmed Ali and even Agyeya who was briefly associated with the PWA in the 1930s and 1940s) and also significant objectives.32 Like the PEN, the PWA stressed the fundamental role of literature in furthering the cause of Indian freedom, and envisaged itself as a pan-Indian organization that aimed at the unification of the country with a strong translational agenda and international(ist) outlook. Redressing the asymmetric recognition of nations and literatures on the world stage and the denigration of non-Western cultures were also paramount concerns for both organizations. And although Sophia Wadia’s speech at the International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture held in Paris (and largely supported by the Soviet Union) in 1935 was criticized by PWA founder, Sajjad Zaheer, for what he considered to be its reactionary undertones and its ‘Hinduization’ of India,33 it was suffused by the rhetoric of anticolonialism.

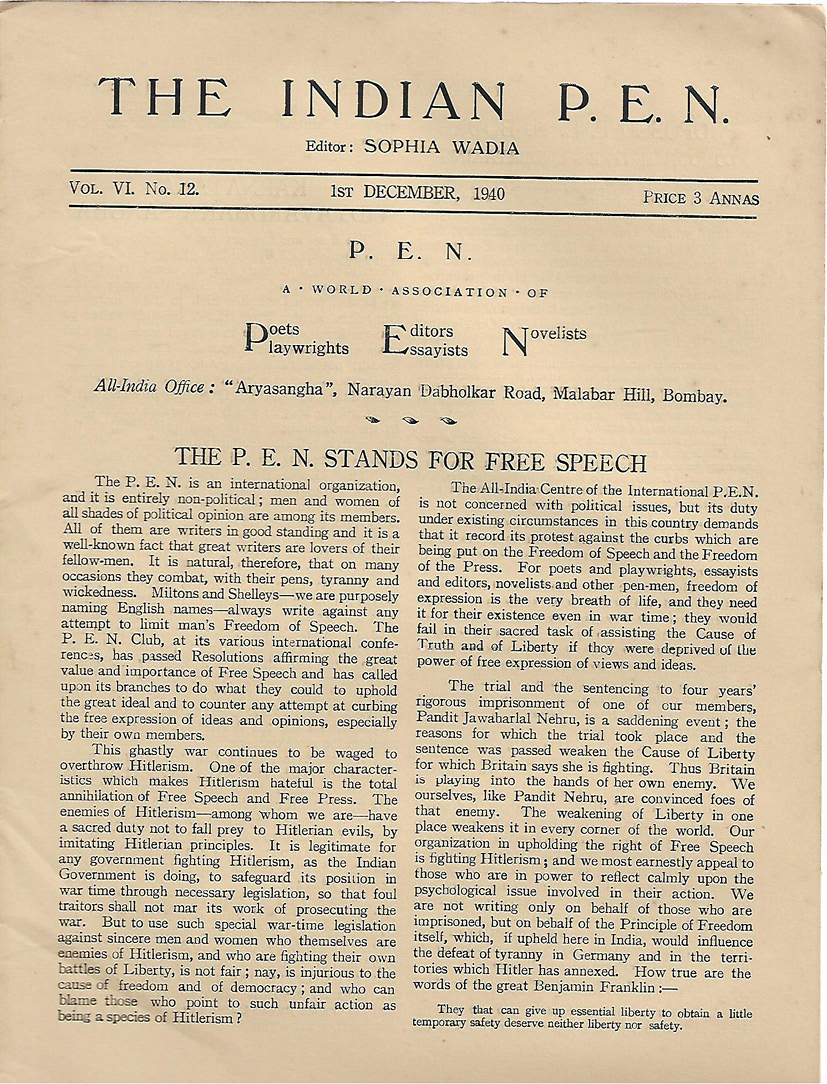

PEN’s anticolonialism, however, was always sustained by ideals of cosmopolitanism and universality. Take for example an editorial like ‘the PEN Stands for Free Speech’ (see Fig. 5.2), in which the Indian PEN registered its protest against the British government’s sentencing of Nehru to four years of imprisonment in impassioned and personal terms, while also incisively highlighting the hypocrisy of an organization that upheld the ideal of Free Speech internationally, but stayed silent to the encroachments of Liberty (by PEN members) in non-Western parts of the world. Curbing the freedom of those who, like Nehru, were both fighting Hitlerism and ‘fighting their own battles of Liberty’ injured the ‘cause of Liberty’ and the ‘Principle of Freedom’: ‘And who can blame those who point to such unfair action as being a species of Hitlerism?’34 By re-asserting at the outset that ‘the P.E.N. is entirely non-political’, the editorial was careful to show that its protest was not motivated by contingent or particular considerations, and should not be interpreted as taking sides in a political, East versus West, or even colonial versus anticolonial battle. In other words, local struggles are not waged in the name of ‘sex and age, of race and creed, of cultural backgrounds and political leanings’,35 but are variants of world struggles. This explains why the Indian PEN often correlated India’s freedom struggle with the war against Hitlerism and fascist tyranny in the 1930s and 1940s.

‘The weakening of Liberty in one place weakens it in every corner of the world’ could, in many ways, represent the motto of an organization which asserted India’s independence as much as its interdependence, stood for a freedom based ‘on the oneness of humanity’,36 and claimed that ‘Cosmopolitan and Liberal Internationalism [was] the only salvation for mankind’.37

Fig. 5.2 ‘The PEN Stands for Free Speech’ (TIP, December 1940). Courtesy of the PEN All-India Centre.

(Cultural) Freedom in the Cold War, the Indian PEN and the ICCF

This ‘oneness’ was severely tested during the Cold War, when the proximity of the Indian PEN and the ICCF also showed that the ‘Principle of Freedom’ was not free from ideological struggles. The ICCF and the Indian PEN regularly collaborated, and many writers belonged to both organizations. Sophia Wadia and Nissim Ezekiel, for instance, were at the same time foundational figures of the PEN and prominent members of the ICCF. Ezekiel, who was the first editor of Quest, started getting involved in the Indian PEN in the early 1950s and became its secretary for more than 30 years, while Sophia Wadia was a signatory of the ‘Sponsor’s Appeal’ and a delegate to the 1951 CCF Bombay Conference aimed at bringing together Indian intellectuals in ‘their joint resolve to uphold and extend the liberties they have inherited or created’.38

Within minutes of his ‘welcome address’ at the same conference Minoo Masani referred to International PEN as ‘the organisation of the writers of the free world’, thereby conflating, in one sweeping formula, International PEN with anti-communism, and by the same token jeopardizing PEN’s supposed apolitical or supra-political stance:

This (totalitarian) threat is not one that is confined in India but is universal and at its recent Congress in Edinburgh, the International PEN — the organisation of the writers of the free world — went on record “for liberty of expression throughout the world and viewed with apprehension the continual attempts to encroach upon that liberty in the name of social security and international strategy”.39

International PEN, however, had never been the organization of the writers of the free world—but the organization of world writers committed to uphold freedom of expression. The nuance, of course, was crucial, though clearly difficult to maintain at the time.40 This was apparent in 1955 when the then President of International PEN Charles Morgan gave a speech entitled ‘The Dilemma of Writers’ at the International PEN Congress in Vienna. The ‘dilemma’ of an organization like the PEN was how to reconcile the two principles on which it was founded: on the one hand, PEN was not a political assembly and did not engage in state or party politics, and on the other hand, it pledged to ‘oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression’.41 Although International PEN had tirelessly sought to bring together writers from opposite sides of the curtain, Morgan concluded that writers who are ‘refugees from tyranny’ were entitled to PEN’s protection, while writers who are ‘instruments of tyranny’ were not. Centres in totalitarian countries, including a prospective Soviet Centre, could not be admitted within the PEN.42 This was interpreted by the Communists as proof that PEN had chosen its side.

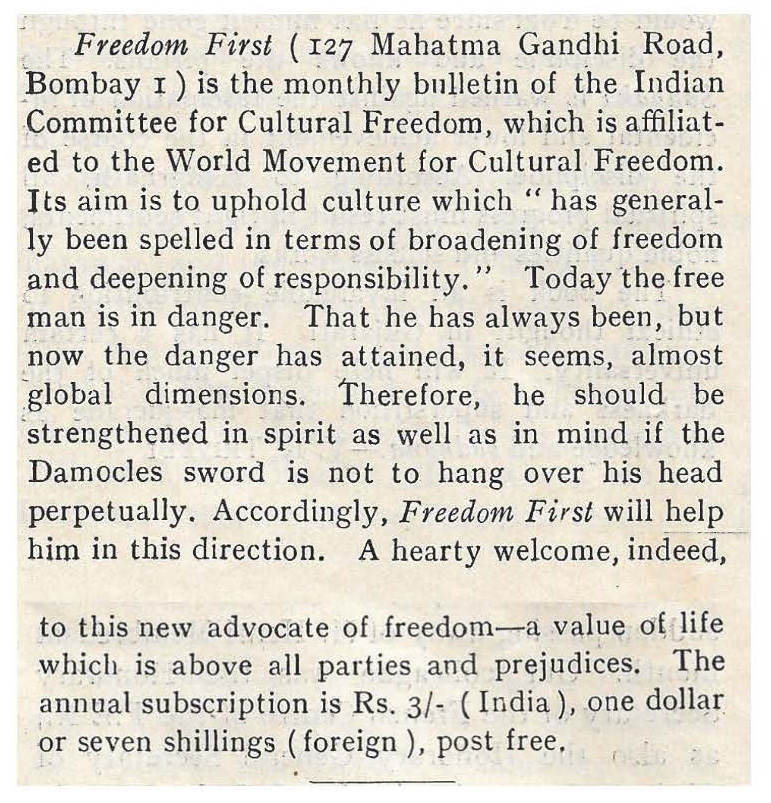

In India, it would indeed be difficult to claim that it had not.43 Although it was not surprising for The Indian PEN to advertise activities of the ICCF—after all, the journal was supposed to act as an echo chamber of world literary news and a ‘clearing-house for news of literary developments in all of the country’s language areas’—,44 the proximity between both organizations was remarkable. Not only did the two journals cross-advertise their respective events and publications, but they explicitly displayed their shared understanding of the notion of ‘freedom’, and of the attacks to which it was subjected. Pages of TIP regularly assert that both PEN and the Congress stand for liberty of expression; the new monthly bulletin of the ICCF, Freedom First, is defined as a ‘new advocate of freedom’,45 engaged in the ‘global struggle’ against enemies of ‘free men’ (See Fig. 5.3), and Quest is called a ‘sister journal’:46

Fig. 5.3 The Indian PEN on Freedom First (TIP, September 1955). Courtesy of the PEN All-India Centre.

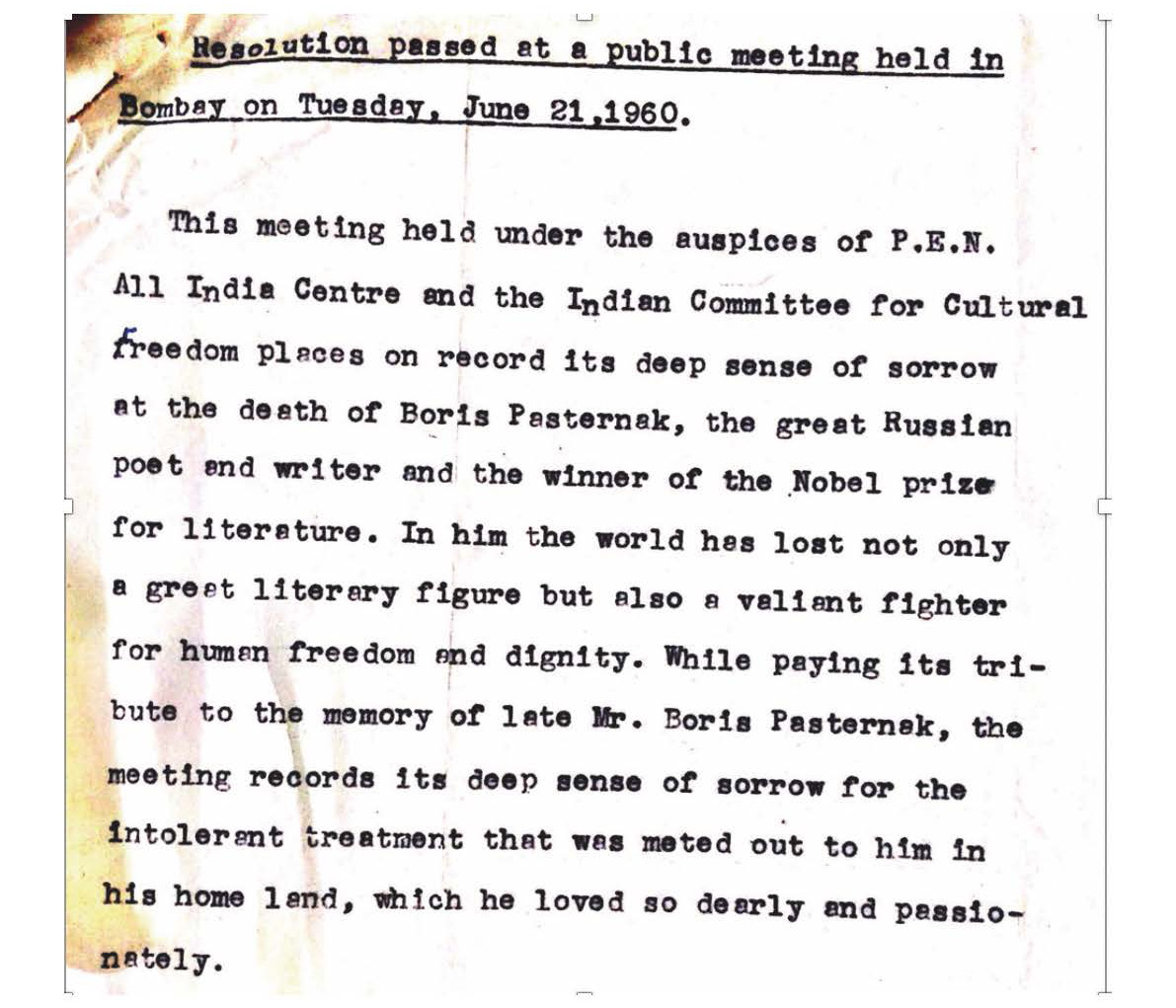

The Indian PEN Centre and the ICCF also held joint meetings and passed joint resolutions. A non-exhaustive list of events co-organized and/or co-sponsored in the 1950s and early 1960s includes: a public meeting in Bombay to protest against a new copyright bill that encroached on the rights of authors (1956); a four-day seminar on ‘Trends in Post-Independence Literature’ in Marathi, Hindi, Gujarati, and Urdu (1958); a public meeting that led to a common resolution recording their deep sorrow at the persecution and the death of Pasternak (remembered both as a great writer, and as ‘a valiant fighter for human freedom’, see Fig. 5.4), as well as a meeting around Stephen Spender’s visit to Bombay where he gave a talk on The God that Failed (1960); a joint scheme to raise funds for the relief of writers afflicted by floods in Poona (1961); a resolution condemning the Chinese invasion of India ‘as an attack on human freedom and world democracy’ (1962); a joint appeal on the invasion of Czech territory by the Soviet Union (1963).

Fig. 5.4 The Indian PEN papers, Theosophy Hall.

Before discussing the different meanings and forms taken by these struggles for cultural/literary freedom in the essays of various ICCF publications, let us recall that for the CCF, and as briefly suggested above, ‘cultural freedom’ was synonymous with anti-communism.47 In the 1950s and 1960s, both blocs were engaged in ‘pressing the fight’ and in devising a vast ‘arsenal of cultural weapons’ (in Saunders’ phrase).48 Out of this arsenal, the Congress, which was indirectly (and covertly) funded by the CIA through a network of foundations (such as the Ford, Farfield and Asia Foundations), had a key role, and one of its most influential ‘weapons’ was the magazines it sponsored, such as Quest.

‘There is no neutral corner in Freedom’s room’ was one of the famous catch-phrases of the inaugural 1950 Berlin Congress.49 A similar profession of faith was reproduced in the first issue of Quest, which opens with an insert about the CCF: ‘Considering moral neutrality in the face of the totalitarian threat to be a betrayal of mankind, the Congress opposes “thought control” wherever it appears’.50 The CCF is described as an unofficial ‘association of free men bound together by their devotion to the cause of freedom’ (italics mine). Most Indian writers associated with the ICCF would no doubt have recognized themselves in parts of the ‘Freedom Manifesto’ drafted by Arthur Koestler in 1950, which asserted that intellectual freedom is one of the ‘inalienable rights of man’, and also defined freedom as both ‘the right to say no’ and the right to express opinions which differ from those of rulers.51

Like organizations in other parts of the world connected to the liberal constellation, in India the ICCF was founded by left-wing anti-communists, but their struggle for ‘cultural freedom’ had other genealogies than the Cold War. The first genealogy, common to the Indian PEN, was the freedom struggle (see above). Many co-founders of the ICCF were towering intellectual figures who had not only embraced Socialism or Communism in their youth but had taken a prominent part in the Quit India Movement. Without arguing for a smooth continuity between anticolonialism and anti-communism, it is important to keep in mind that Jayaprakash Narayan (who had been tortured by the British, and later became a prominent political opponent of Nehru—and Indira Gandhi), Minoo Masani and K. M. Munshi all placed their struggle for ‘cultural freedom’ in the 1950s in the same lineage as their earlier freedom struggle against the British Raj.

As a few scholars have recently argued, it is necessary to recover the anti-totalitarian (both anti-imperialist and anti-communist) lineage of liberalism for Third World struggles. Roland Burke, for instance, claims that the ‘variegated ideological texture’ of the Third World has been washed away by more obvious narratives of Non-Alignment and anticolonialism associated with the Afro-Asian movement and what he calls the ‘mythology of Bandung’.52 By discussing a series of conferences hosted by the CCF in Rangoon, Rhodes and Ibadan in the 1950s, he foregrounds a ‘Third-Worldism’ that was shaped by Asian and African intellectuals with an aversion to concentrated power. Poised ‘between imperial and postcolonial authoritarianisms’, these ‘Cold War liberals’ voiced their concern for individuals rather than states, and focused on the universality of experience, more than on racial — or even Third World—specificity.53 In Burke’s definition of the CCF’s Asian and African members, I would indeed recognize the position of many of the Indian writers examined in this essay: ‘Weary of extremity in all its species, be it nativist reaction, messianic nationalism, or bureaucratic and technocratic statism, the variegated collection of participants were generally unified in a kind of urgent insistence on caution and care in navigating the threats to freedom’.54

Anti-imperialism, then, wasn’t only a prerogative of the World Peace Congress, the Communist bloc, or the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association at the time. If, as Patrick Iber has argued, the CCF mostly ‘focused on the totalitarian continuities between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union’,55 many members of the ICCF and other Asian and African branches of the Congress stressed the totalitarian continuities between colonialism and communism.56

What’s more, although anti-communism was certainly on the agenda of the inaugural ICCF conference in Bombay, it wasn’t the priority of many Indian participants whose struggles for cultural freedom also took other forms.57 The huge poster featuring words attributed to Gandhi that was placed behind the podium of the opening session could sum up the spirit of the meeting: ‘I want the winds of all cultures to blow freely about my house. But not to be swept off my feet by any’. Several writers stubbornly flaunted their refusal to partition the globe between the ‘enslaved world’ and ‘the free world’ (where, precisely, ‘varying degrees of freedom and slavery’ in fact intermingled, in Narayan’s words); or the splitting of writers into ‘clear-cut camps’ (in the words of Buddhadeva Bose); or again the ‘false choice’ between ‘peace’ and ‘freedom’ (Agyeya).58 In a sense, many also used this platform to stage their independence, their own quests and struggles for freedom—while also connecting them to world struggles. Several resolutions were passed, including on Soviet slave-labour camps and on racial discrimination, while the last resolution emphatically condemned the suppression of cultural freedom ‘by either totalitarianisms of the Left or reactionaries of the Right’.59

‘Freedom’, to various writers at the time and certainly to many participants of the Bombay conference, often meant freedom from Cold War alignment; freedom from the weaponization of literature reduced to ‘militant propaganda’;60 and also freedom to build their lives/worlds/words in their ‘own quiet way’, to quote from Buddhadeva Bose’s poignant declaration: ‘refusing to be terrified […] we in India try to build our lives in our own quiet way instead of modelling ourselves on any of the great world powers, who are now the hope and terror of other nations’.61

In his chairman’s address, Jayaprakash Narayan not only castigated the ‘narrow, sectarian and oppressive’ aspects of Indian culture (and the immensity of the task ahead to achieve ‘cultural freedom’) but highlighted the hypocrisy of the ‘free world’, and of the British in particular, for whom the fight against fascism during World War II had meant turning India into a ‘concentration camp’. In a gesture reminiscent of Mulk Raj Anand, and Sophia Wadia before him, Narayan argued that the British were no better than their totalitarian (fascist and communist) counterparts:

Why should the world, or rather the free world, as it is called be divided between the shepherds and the lambs? And what does the fight mean to the lambs? Let us concede that the lambs have been protected. What happens then? The shepherd comes one day with his shears and the lambs are shorn of their wool. And finally, the shepherd appears with his knife, and who will protect the lamb? In the circumstances you cannot blame the lamb if he does not enthuse over his protectors. There is a great deal of talk today of the conflict between totalitarianism and freedom. During the last war there was a great deal of talk of similar conflict between fascism and democracy. Mr. Churchill had then invited the Indian people to take part in that “war for democracy”. […] India had said then […] that she would not fight for democracy when she herself was enchained in slavery. And for that answer “democracy” did not hesitate to shut up Mahatma Gandhi in prison and turn the whole country into a concentration camp. Is the situation different today? […] Over a hundred million Negros of Africa and millions of Arabs are being ruled today by the free nations of the world: Britain, France, Spain, Portugal. What does the fight against totalitarianism mean to these millions of people? […] If at the end of the impending ‘anti-totalitarian’ war, the world picture remained essentially unchanged, i.e. of a world divided between the weak and the strong, the prosperous and the abjectly poor […] the war would have been fought in vain.62

‘Democracy’ and ‘freedom’, ‘anti-fascism’ and ‘anti-totalitarianism’ are turned on their heads or exposed for what they truly amount to: ‘mere talk’ that leaves millions of Africans, Asians and Arabs in subordination. Narayan’s speech, which called for the overturning of a world order that sees the ‘big nations’, the ‘strong’ and powerful, continue to use, enslave and rule over the ‘small’ and weak, foreshadows in many ways some of the declarations and positions later taken in Bandung, and then Tashkent. This may be another way to understand Elizabeth Holt’s argument that the would-be radical gesture of Lotus, the trilingual journal of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association founded in 1967, ‘borrows more than a few pages’ from projects already initiated by the CIA’s covertly funded CCF.63 The difference however, was that Jayaprakash Narayan seemed less concerned by a specific ‘Third World’ solidarity, than by the vision and project of a ‘world community’, in which (as the end of his speech suggested), the big nations ‘willingly share their power, prosperity and knowledge with the small’.64 Ideals of the ‘oneness of humanity’ and of ‘world community’ (even ‘world federalism’) were largely shared, as suggested above, by the Indian PEN, and they also help understand the intellectual kinship between the ICCF and the Indian PEN.

With respect to Lotus, Hala Halim argues that if the journal was founded in 1968 (a year after the role of the CIA in the CCF was exposed) to counter cultural imperialism, its partial funding from the Soviet Union attests to the degree that ‘Non-Alignment was inevitably undermined by the Cold War configuration’.65 Yet gauging to what extent these publishing and intellectual ventures (whatever the ‘side’ which sponsored them) were undermined by the Cold War configuration, seems far less relevant than understanding how they were constitutive of this complex—and far from manichean—configuration. First, because, as Jayaprakash Narayan declared, varying degrees of alignment and non-alignment, just like freedom and slavery, intermingled in all these ventures. Second, because, as I will continue to argue below, for many postcolonial intellectuals these ventures were often also enabling. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that if we want to retain the language of compromission, the journals that belonged to the transnational galaxy of the anti-communist CCF, and were sometimes ignorant recipients of CIA money, were perhaps no less and (crucially) no more undermined than those identified with the communist bloc.

It is hence difficult to agree with critics like Andrew Rubin when he declares that journals such as Preuves, Encounter or Quest ‘reinforced the formidable structures of cultural domination’, or prevented the emergence of dissenting discourse.66 True, there was a certain cooptation of dissent, and of modernism, which Greg Barnhisel described as being purged of its radicalism by its Cold War institutionalization. As poet and critic Adil Jussawalla wrote of curtain-filtered or state-sanctioned literature, ‘what filters through the curtain is only fit for the international shit-pot’.67 True as well, the formidable publishing artillery that exported knowledge and books to India, and ensured the publication of foreign writers (such as George Orwell, William Faulkner, Czeslaw Milosz, or Auden), contributed less to sustain local book industries and publishing infrastructures.68

Yet, Indian modernisms were crucially nurtured by the transnational and translational traffics also made possible by the Cold War.69 What’s more, the institutional cooptation of culture that could be seen as the continuation of colonial processes of cultural imperialism in postcolonial contexts often triggered, in reaction, a quest for self-determination and for unofficial literatures or countercultures. Finally, as I argue below, if Quest was officially a CCF mouthpiece and published a wealth of foreign intellectuals mostly belonging to its galaxy (Arthur Koestler, Paul Tabori, Denis de Rougemont, Edward Shils, Raymond Aron, Stephen Spender, etc.), it also published some of the most important Indian writers and critics of the time (in English and in translation) who often used its pages to articulate their own concerns and hone their creative, critical, and polemical skills.

Cultural Criticism as an Exercise in Freedom

‘Cultural regression links up to political reaction’

In an essay initially published in 1963, Nissim Ezekiel made a case for writers to act as a pressure group for freedom. Since, however, an agreement as to what freedom means cannot be taken for granted, he argued, it is essential for writers to debate it frequently among themselves. Ezekiel also made a plea ‘for a persistent debate of this kind’ which ‘clears the ground for action against censorship in all its forms’.70 In many ways, these words capture the tone of Ezekiel’s essays, and the agenda of several of the journals he edited: clearing the ground for debate, for dissensus, and for (political, cultural and literary) pluralism as an antidote to forces of conformism and repression.

Culture, according to Ezekiel, is ‘a complex of problems’—not a ‘personal acquisition’ or a ‘formal doctrine or ritual’.71 In Quest, whose first sub-title was ‘a bi-monthly of Arts & Ideas’, and which sought, as its first editorial article made clear, ‘vigorously written articles of a provocative nature’,72 many Indian writers in effect gave voice to their ‘problems’ with various ideas, authors or art forms. Among the regular features of the journal were book, film, art and theatre reviews, as well as long ‘review articles’ and a feature called ‘Discussion’, where specific ideas were debated, often over the course of several issues, through two opposite opinions (for instance ‘For and Against Abstract Art’ in the Spring 1963 issue). The objective was to create the conditions for freedom—freedom to argue, to question, to doubt, to disagree—to thrive in India; and for cultural or critical independence, both to fulfil the political independence achieved less than ten years earlier, and to prevent the future suppression of freedom.

‘We shall continue to deserve the rulers we have until a ferment of ideas displaces the co-existence of ideologies’, Ezekiel wrote in another illuminating editorial in which he complained about the deep-rooted acquiescence in the acts of authority and a ‘lethargic’ respect for it’, which he thought explained the absence of an organized political opposition.73 In his essay ‘Ten Years of Nehru: A Minority Report’, J. S. Saxena (ICCF member and frequent contributor to Quest) likewise emphasized the need for dissenting thought and the importance of cultivating a pluralist conception of power, while painting a scathing portrait of a megalomaniac Nehru, surrounded by ‘yes-men’, and whose vision had hardened into a creed with ‘apostles and renegades’: ‘the prime-minister has swallowed the thinker: the party-machine has tamed, if not broken, the rebel and the democrat’.74 Of course, this indictment of ‘the rulers we have’, and many of Quest’s virulent attacks on the Congress, on Nehru in the 1950s and 1960s, and later on Indira Gandhi, must be contextualized within the disenchantment (or ‘moh-bhang’ in Hindi) of the 1950s. The feeling that India’s official freedom from the British was in fact ‘an untrue freedom’75 was shared across ideological divides, and Quest was not alone at the time in challenging Nehruvian state-planning ideology and the stronghold of New Delhi, nor in voicing concerns over the betrayed promises of Independence or over the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution (1951), supported by Nehru, which restricted press freedom.76

‘What exactly do we mean when we call a society free?’, Ezekiel’s essays tirelessly returned to that question:

A non-communist society such as the Indian does not automatically qualify for the label free. In fact […] there is a constant need to explore the conditions in which it exists. We must probe, doubt, question, question, question. As soon as freedom is taken for granted, it is already diminished. Before freedom is destroyed a state of mind must be popular to which freedom does not matter. […] Some other value is more important — the welfare of all, security, a national emergency […] there may be more censorship in India during the years to come and it will not be an accident.77

In this Quest editorial, which also criticized the practice of preventive detention without trial, Ezekiel again emphasized the need to debate the conditions, meanings and implications of freedom, and asserted the experimental and uncertain vocation of criticism (‘we must probe, doubt, question, question’). This relentless need was mirrored by a personal, self-reflexive style that did not iron out repetitions and modal expressions.

Twenty years later, another editorial (published just before the journal had to shut down during the Emergency) declared that dissent needed to ‘be deliberately nursed, not muzzled and driven underground (as anti-social or inspired by forces bent on harming the nation)’.78 To many writers and intellectuals, the right to differ seemed as imperative as cultural unity was to the Indian PEN in the years leading to Independence. Hence Ezekiel’s championing of the writer as someone able to struggle ‘against the processes by which a nation is made to conform’,79 or at least to question prevailing ideological, cultural and even formal orthodoxies—the ‘streamlined beliefs’80 that could in turn be those of communism or Nehruvianism, religious orthodoxy and ideological alignment, or simply intellectual conformism and literary uniformity.

Ezekiel’s plural conception of power matched his plural conception of the literary and cultural field. Since the lack of literary and cultural pluralism could pave the way for the suppression of ‘inconvenient’ and ‘angry’, but also marginal and ‘quiet’, voices to take up Ezekiel’s words again, many of the journals with which he was involved also gave space to different or marginalized forms of Indian writing at the time (Indian writing in English, modern Indian poetry, ‘new’ or modernist voices, translations, etc.), and to divergent ideas or various literatures (in English, together with other Indian languages). Long reviews or review-articles were also meant, as suggested above, to give form to a diversity of ‘vigorously written’ opinions.

Liberalism, Modernism and the Primacy of the Individual Voice

The origin of the new is always the individual

Nissim Ezekiel

Unlike the PEN All-India Centre, which received government money and was close to the leaders of Indian independence (Nehru, Radhakrishnan, Sarojini Naidu, Zakir Husain, etc.), many intellectuals affiliated with the ICCF understood freedom—in accordance with the liberal credo—as the antithesis of state control. An article written by Ionesco and reprinted in Quest under the title ‘Culture is not an Affair of State’ sums up the spirit of this liberal outlook. The essay criticized the drive, on the part of governments but also organizations such as UNESCO, and even PEN, to prescribe rules for writers and artists. According to Ionesco, the only duty of a Minister for Cultural Affairs was that of a ‘poet-gardener’: making sure that thousands of different flowers grow while defending endangered herbs, because the ‘deep instinctive biological imperialism’ that inhabits plants and nations encourages them to suffocate the space belonging to others. No voice must ever be reduced to silence.81 The essay ends with a Dada-like gesture that Tristan Tzara would not have disowned: ‘When I hear men of State, politicians, international diplomats […] speak of culture, I want to take out my revolver.’82

In Ionesco’s case, his outspoken anti-communism explains his virulent anti-statism. If anti-communism similarly colored the anti-statism of many Indian writers affiliated with the ICCF (‘socialist realism’ is described in an article reprinted in Quest from Soviet Survey, as the ‘wheels’ and ‘screws’ of the great machine of State),83 yet I would argue that this anti-statism is only one of the forms taken by their aversion to different kinds of ‘thought-control’. These writers constantly object to culture or literature being made subservient to an authority or an ideology (whether statist, religious, national, or nationalist), to individual voices being diluted in the ‘mass’ or choked by the ‘strident voices’ of cultural regimentation and authoritarianism.84 Art and individuality must not surrender to what J. S. Saxena also called the ‘stentorian voice’: ‘only a totalitarian society tends to produce a monolithic individual elite, structurally centralized, speaking with a stentorian voice to the whole of society’.85 Against this monolithic, stentorian or strident voice, Ezekiel and Quest promoted those ‘myriads of little truths’ and voices that humiliate ‘the Truth’,86 and cultivated doubt, ambivalence and obliqueness. ‘If your certainties lack the flavor of uncertainty, the restraining power of doubt, you become a murderer in the realm of ideas’, Ezekiel wrote in the beautiful essay-column tellingly entitled ‘Uncertain Certainties’ that he periodically published in Fulcrum during the Emergency.87 And against these voices of power that claim to speak to the whole of society, writers and intellectuals affiliated with the ‘liberal’ constellation favoured small collectives, associations, fraternities and micro-communities,88 which both the Indian PEN and the ICCF represented, to a certain extent. To get creative and critical work done, Ezekiel suggested again, we have to ‘fall back on small groups and individuals. […] In cultural affairs any colossal attempt at cultural development often fails’.89

The primacy of the individual, and of the (defiant) singular voice leads us to the question of modernism. When Nissim Ezekiel writes that ‘the origin of the new is always the individual’, he is, in many ways, providing a possible definition for both liberalism and modernism.90 ‘Modernism’, as briefly suggested at the beginning of this chapter, was transformed into a Cold War cultural-diplomatic weapon by the ‘free world’. The CCF and its journals promoted modernism because its so-called autonomy and abstraction, its presumed emphasis on form, style or the ‘medium’ itself, rather than on content or ideology, were seen as a bulwark against totalitarianism and a symbol of Western artists’ freedom.91 Modernism and the avant-garde were in turn targeted by the Union of Soviet Writers for being decadent, bourgeois, and solipsistic. At the first Soviet Writers’ Congress held in Moscow in 1934, where Andrei Zdhanov endorsed ‘socialist realism’ as the official line of Communist writers, Karl Radek outlined a mutually exclusive alternative: ‘James Joyce or Socialist Realism’ (italics mine). Epitomized by James Joyce, modernist experimentalism was seen as the literature of a dying capitalism, whose ‘triviality of content’ was matched by ‘triviality of form’.92

As I have highlighted elsewhere, the Cold War hence undeniably sharpened the debate between the ‘politics of art’ and its autonomy, between ‘socialist realism’ and experimentalism, between poetic vocation versus social relevance, and between ‘the culture of the masses’ and the radical individuality of artists.93 These issues were hotly debated in Indian journals in the 1950s and 1960s as well. Yet, in the case of India the struggle of many writers and artists at the time seemed also about freeing their voices from such exclusive alternatives; freeing the notion of ‘freedom’, as it were, from both ideological and nationalist cooptation; and freeing the notion of modernism from ownership by the ‘West’. Remember Mulk Raj Anand’s call to free literature from the ‘militant propaganda’ to which the Cold War had reduced it. Many writers, whatever the ‘side’ they were apparently on, refused to let literature be cut to shreds by the scissors of ideology.94 That is also how we must read Ezekiel’s insistence on examining literature with literary standards rather than political ones, or for instance his contempt at the ‘hysteria’ of western critics who had ‘extravagantly praised’ a book such Not by Bread Alone by V. Dutintsev, only because it gave an unfavourable picture of the Soviet Union.95

The struggles over Dr. Zhivago at the time need to be read in this context. Pasternak was championed by the ‘free world’ for his ‘a-political’ art and heralded as a martyr of Communist persecution, while the Soviets accused him of ‘pathological’ individualism and of concealing his anti-communism behind claims to artistic autonomy. Ezekiel argued that Dr. Zhivago was not a political novel but a great love story, while Buddhadeva Bose paid tribute to Pasternak for ‘making love the business of poets’ again. By declaring his reverence ‘for the miracle of a woman’s hands’ and his lifelong devotion to ‘back, shoulders, neck’, Bose argued, Pasternak had re-asserted ‘man’s sacred right to become and remain an individual’.96 To Alexei Surkov (then Secretary of the Soviet Writers Union), who had claimed that it was crucial for writers to be of the same opinion, Bose offered a remarkable rejoinder. When that happens, there can be millions of printed words, but no literature: ‘from the Russia of Dostoievsky, Tolstoy and Pasternak, comes anew the message that “salvation lies not in loyalty to forms and uniforms, but in throwing them away”’.97

Modernism’s ‘Freedom Struggles’: Finding One’s Voice

Freedom… consists in making meanings for yourself

We breathe for ourselves, not for the age we live in

Modernism in India was also, I would argue, about the ‘displacement of ideologies’ through the ferment (or ‘throwing away’) of forms. This explains Yashodhara Dalmia’s claim that the powerful individualistic possibilities of modernism could be considered a betrayal in India, where cultural nationalism was virtually required of writers and artists during the struggle against colonial rule and in the two decades following independence. The autonomy and the individuality of the artist were everything but a given. Asserting both was one of modernists’ struggles in India.

The painter Gulammohammed Sheikh remembers the ‘scent of freedom, promised by the winds of the “modern” blowing in the air’ in the 1950s, and his generation’s hunger for ‘untrammeled visual terrains’ (italics mine).98 The ‘blasting’ of academic traditions, which is an inescapable signature of the avant-garde, was also about short-circuiting ideologies, and cultural nationalism. The painter F. N. Souza states this well in a 1949 essay about the evolution of the Progressive Artists Group: ‘we have hanged all the chauvinist ideas and the leftists’ fanaticism we had incorporated in our manifesto […] Today we paint with absolute freedom for content and techniques almost anarchic’.99

Admittedly, a journal like Quest was not at the forefront of this experimentalism, unlike the more radical, short-lived, anti-commercial and anti-establishment ‘little magazines’ in English, Marathi, Gujarati, Bengali and other languages in the 1950s–70s which were the privileged medium of the avantgarde,100 or the ‘little magazine’ of Paulo Horta’s chapter in this volume. However, Quest and many other journals with which Ezekiel was associated welcomed some of these more experimentalist texts, perhaps because, as Adil Jussawalla puts it, Ezekiel was also one of the first Indian poets to show that ‘craftsmanship is as important to a poem as its subject matter’.101 Arun Kolatkar’s first English published poems for instance appeared in the inaugural issue of Quest, and Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s Howl-affiliated sequence ‘Bharatmata’ (‘which was everything that Nissim’s poetry was not’102) came out in Poetry India, another of Ezekiel’s magazines, in 1967.

At least during Ezekiel’s editorship, then, the intellectual and creative agenda of Quest—oppositional, and open to marginal or inconvenient voices—participated in the idiom and project of modernism. In fact, Quest did become a vehicle of literary modernism from the 1950s onwards by publishing creative texts from a wealth of budding or more established contemporary voices belonging to the different literary cultures of India, among whom Asha Bhende, Gieve Patel, Mulk Raj Anand, Kamala Das, Buddhadeva Bose, Krishna Baldev Vaid, Arun Kolatkar, Indira Sant, Amrita Pritam, Jibananda Das, P. S. Rege, A. K. Ramanujan, Eunice de Souza, Agha Shahid Ali, Adil Jussawalla, Agyeya, Dom Moraes, Subhash Mukhopadhyay, Saleem Peeradina, Kersy Katrak, Keki Daruwalla, Georges Keyt, Gauri Deshpande, Farrukh Dhondy, Anita Desai, Kamleshwar, U. R. Ananthamurthy, Kiran Nagarkar, Keki Daruwalla, Dilip Chitre, and so on.

If Quest pressed for evaluating art and literature through literary standards, it also aimed at raising the standards of writing and style, of criticism, and of translation. In the editorial of an issue of TIP on ‘the problem of translation’, which he guest-edited, Ezekiel asserted that if translating between Indian languages and into and from English was an urgent task, the difficulty for Indians to use English creatively made it all the more problematic. Turning English in India, which is so often ‘flat, unevocative, if not altogether dead’, into a contemporary, ‘live, changing language’, and also into a vehicle of modernism, was obviously one of the main objectives of Ezekiel, and of many of the journals he edited.103 This concern was shared by Adil Jussawalla in ‘Boys and Girls in Purdah’, where he equated the ‘curtain’ through which literatures are filtered (and castrated) to the ‘purdah’ of a very ‘correct’ English language, from which there seemed to be no escape but into what he called ‘Little Englands and Little Americas’.104 A lot of Indian writers who write in English are ‘students who write or housewives who write’ rather than writers with a sense of vocation, Jussawalla argued. Because of the dreadful trivialization of the English language, he called for the ‘living acid’ of the contemporary Indian writer to wrestle with the curtain, and tear holes in it.

Many of these texts epitomize the struggle of a generation of writers to find an idiom and a modernism of one’s own, so to speak—connected to world voices and modernisms but also, crucially, distinct. ‘True modernism is freedom of mind, not slavery of taste. It is independence of thought and action, not tutelage under European masters’, Tagore had said, and Ezekiel often quoted him approvingly.105 As I have tried to argue here, this struggle has a long lineage, and is, in many ways, shared by the more radical or experimental ‘little magazine’ writers mentioned above.106 If this struggle may have been more acute for writers writing in English, or in English and another Indian language, it was a widely shared one. The ‘curse of belatedness’ (in Dipesh Chakrabarty’s words) or of influence, inauthenticity and mimicry that has plagued non-western or postcolonial modernisms was another prominent ‘freedom struggle’ to wage after Independence, both in India (where modernism was often perceived as an offspring of the West) and in or vis-à-vis the West (where many Indian modernists were told to go back to their ‘folk’ or classical art).107

J. S. Saxena’s essay published in Quest, ‘The Coffee-Brown Boy looks at the Black Boy’, for example, revolves around the struggle to resist imitation, and to reclaim ideas, feelings and forms that had not first been framed or voiced by others (and in the process tamed or trivialized). Focused on ‘the links that bind’ Indians and black Americans, connected by their common effort to resist the compulsion of ‘catching up’ with the West and discard abstractions about themselves, Saxena’s essay gives this struggle a painful, enraged, and often self-sabotaging tone.108

How can ‘coffee-brown’ and ‘black boys’ stop writing, thinking, even feeling like? How do you break free from the pressure to model yourself on the images and the aspirations of others? How do you stop trying to return to where you never came from? What struggles and imaginaries can brown and black ‘boys’ reclaim as their ‘own’, when even the language of struggle and freedom has been coined or devised for (not by) them: ‘Even when we talk of Indianisation and negritude, we are White Liberals draped in black or coffee-brown skin’. Saxena’s essay is suffused by forms of guilt, shame, and self-hatred that also prove his argument. The compulsion to imitate breeds monsters—like the United States and the Soviet Union which, he argues, succeeded so well in catching up with Europe that they ‘have become the most frightening monsters Man has ever known’.109

Like many of his other texts, Saxena’s essay is saturated with a dizzying number of quotations and references to Western writers and philosophers, which also expose the difficulty of articulating one’s own voice. ‘Imprisoned in other people’s metaphors’, the ‘Indian’ is described as a scatter of attributes, a dust-bin for the debris and fictions (the words?) of others. In a striking image, ‘a lot of gaping holes tied with the White Man’s string’:

The zest with which the status symbols of Europe and America are imbibed and assimilated, honed up, refurbished, renovated in the race for catching up cannot […] cover up the nullity and boredom of the coffee-brown boy’s existence. Miming is not living. […] How do we stop being somebody else’s image? […] Freedom does not lie in searching for meanings in the debris of your own life which someone else has hidden for you to find. It consists in making meanings for yourself, in improvising […] a set of resonances you can really call your own110

Yet in the culture of the ‘black man’ Saxena recognized the possibility of an alternative—for instance in the ‘pure logic of refusal’ of blues and jazz. Its practitioners, he argued, represent a permanent reserve of misfits condemned to ‘perpetual minority’. Yet, they can claim an art which is really theirs, and which does not turn away from a brutal reality. Compared to the tameness of the coffee-brown Indian boy’s idiom and rage, which ‘crumble up’ into ‘parish-pump dissertations and home-made Indian lies’, jazz and blues—but also the ‘fragmentary beat’ of a prose writer like James Baldwin, who makes inventive (‘cubic’ is another word Saxena uses) use of the English language—give form to the black man’s traumatic experience of oppression and alienation. This is the central struggle articulated in Saxena’s essay: finding forms and idioms to express the Indian writer’s protest, his freedom and his survival.

Conclusion

By discussing the history of the Indian PEN and the ICCF through the creative and critical spaces they cleared, and through the ‘critical form’ of the essay (Adorno), I have tried to argue for a connected history of decolonization, the Cold War, and modernism. By examining the varied meanings that many writers of the time gave to their ‘freedom struggles’ across forms and ideologies, I have also tried to restore the political and cultural significance of these two relatively neglected organizations connected by a shared liberal ethos. Struggles for literary/cultural freedom and for political freedom were absolutely inseparable, and these writers were in different ways carving out spaces/voices of self-determination and freedom that were also spaces/voices of Non-Alignment.

Nissim Ezekiel epitomized the struggle of his generation of writers—poised not only between colonial and postcolonial authoritarianisms, to borrow Burke’s words again, but also between individual and collective freedom; between the quest for a voice of one’s own and a shared idiom; between poetics as the invention of a subjectivity (in and through language) and politics as a form of collective practice; and between the withdrawal or solitude that sustains the creativity of a writer and the ‘tempests’ of history. That is also the ‘dilemna of writers’ that has haunted an organization like PEN: preserving literature from political alignment, as a condition of independence, while also struggling against the ‘ugly face of Fascism’ (in Mulk Raj Anand’s words), that threatens the freedom, and survival, of writers, intellectuals and artists in India today.

Ezekiel’s words in 1956 that ‘there may be more censorship in years to come’ (quoted above) were, in many ways, prophetic of the Emergency, which gave Indira Gandhi authority to lead by decree, suspended civil liberties and constitutional rights, and resulted in censorship of the press and the imprisonment of political opponents. His quests and struggles, as well as the resistance of journals like Freedom First and Quest during the Emergency, and the opposition of leading ICCF figures such as Narayan and Masani to Indira Gandhi,111 show that ‘cultural freedom’ was not just an extraneous, geopolitical or doctrinal Cold War issue in India after independence. The cultivation of a literary and critical culture; the defense, exercise and ‘probing’ of cultural freedom, as a prerequisite for other kinds of freedom, were a condition of India’s survival, or at least its survival as a democracy. That is also how we must understand Ezekiel’s luminous statement that ‘cultural regression links up to political reaction’.112

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor, ‘The Essay as Form’, New German Critique, 32 (1984), 151–71.

Altbach, Philip, Publishing in India, an Analysis (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1975).

Anklaseria, Havovi and Santan Rosario Rodrigues, eds, Nissim Ezekiel Remembered (New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2008).

Anderson, Amanda, Bleak Liberalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1086/698191

Barnhisel, Greg, Cold War Modernists: Art, Literature and American Cultural Diplomacy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015).

Barnhisel, Greg and Katherine Turner, eds, Pressing the Fight: Print, Propaganda and the Cold War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2010).

Barua, B. K., Assamese Literature (Bombay: P.E.N. All-India Centre, 1941).

Bird, Emma, ‘A Platform for Poetry: the PEN All-India Centre and a Bombay Poetry Scene’, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 53.1–2 (2017), 207–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/17449855.2017.1282927

Brouillette, Sarah, ‘US–Soviet Antagonism and the ‘‘Indirect Propaganda’’ of Book Schemes in India in the 1950s’, University of Toronto Quarterly, 84.4 (2015), https://doi.org/10.3138/utq.84.4.12

Burke, Roland, ‘Real Problems to Discuss’: The Congress for Cultural Freedom’s Asian and African Expeditions 1951–59, Journal of World History, 27.1 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2016.0069

Coleman, Peter, The Liberal Conspiracy, The Congress for Cultural Freedom and the Struggle for the Mind of Postwar Europe (New York: The Free Press, 1989).

Congress for Cultural Freedom, Indian Congress for Cultural Freedom Proceedings, March 28–31 1951 (Bombay: Kannada Press for the Indian Congress for Cultural Freedom, 1951).

Coppola, Carlo, Urdu Poetry, 1935–1970, The Progressive Episode (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1080/17449855.2019.1636556

Chaudhuri, Rosinka, ed., An Acre of Green Grass and other English Writings of Buddhadeva Bose (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Dalmia, Yashodhara, The Making of Modern Indian Art, the Progressives (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Doherty, Megan, ‘A Guardian to Literature and its Cousins’, The Early Politics of the PEN’, Nederlandse Letterkunde 16 (2011), https://doi.org/10.5117/nedlet2011.3.a_g332

Ezekiel, Nissim, ed., Indian Writers in Conference (Bombay: PEN All-India Centre, 1962).

—, Selected Prose (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1992).

—, ‘Art and Literature in Emerging India’, Sameeksha, a quarterly of arts and ideas, ed. by M. Govindan and A. N. Nambiar (December 1965).

Freedom First, Organ of the Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom, Bombay, June 1952.

Garimella, Annapurna, ed., Mulk Raj Anand, Shaping the Indian Modern (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2005).

George, Rosemary Marangoly, Indian English and the Fiction of a National Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Halim, Hala, ‘Lotus, the Afro-Asian Nexus, and Global South Comparatism’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 32:3 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2020.1827599

Holt, Elizabeth, ‘Cairo and the Cultural Cold War for Afro-Asia’ in The Routledge Handbook of the Global Sixties, ed. by Jian Chen et al. (London: Routledge, 2018), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315150918-44

Iber, Patrick, Neither Peace nor Freedom: The Cultural Cold War in Latin America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674915121

Iyengar, Srinivas, ed., Indian Writers in Council: Proceedings of the First All-India Writers’ Conference (Bombay: PEN All-India Centre, 1947).

Jussawalla, Adil, ‘Boys and Girls in Purdah’ (Bombay: Campus Times: 1972).

Kalliney, Peter, ‘Modernism, African Literature and the Cold War,’ Modern Language Quarterly, 76.3 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1215/00267929-2920051

Mandhvani, Aakriti, ‘Sarita and the 1950s Hindi Middlebrow Reader’, Modern South Asian Studies, 53.6 (2019), 1797–1815, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0026749x17000890

Nerlekar, Anjali and Laetitia Zecchini, eds, ‘The Worlds of Bombay Poetry,’ Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 53.1–2 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1080/17449855.2017.1298505

Padhye, Prabhakar, Edward Shils, and Bertrand de Jouvenel eds, Democracy in the New States: The Rhodes Seminar Papers (New Delhi: Congress for Cultural Freedom, 1959).

Passin, Herbert, ed., Cultural Freedom in Asia: Report of the Rangoon Conference (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956).

Pradhan, Sudhir, ed. Marxist Cultural Movement in India: Chronicles and Documents (1936–1947) (Calcutta: National Book Agency, 1979).

Prashad, Vijay, ed., The East Was Read, Socialist Culture in the Third World (Delhi: Leftword, 2019).

Pullin, Eric, ‘Money Does Not Make Any Difference to the Opinions That We Hold: India, the CIA and the Congress for Cultural Freedom, 1951–58’, Intelligence and National Security, 26.2–3 (2011), https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2011.559325

—, ‘Quest: Twenty Years of Cultural Politics’ in Scott-Smith Giles and Charlotte Lerg, eds, Campaigning Culture and the Global Cold War: The Journals of the Congress for Cultural Freedom (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2017), pp. 285–302.

Quest, a Bi-monthly of Arts and Ideas, ed. by Nissim Ezekiel, Bombay: August 1955; April–May 1956; February–March 1957; February–March 1958.

Quest, a Quarterly of Inquiry, Criticism and Ideas, ed. by Abu Sayeed Ayuub and Amlan Datta, Calcutta; July–September 1959; October–December 1959.

Quest, a Quarterly of Inquiry, Criticism and Ideas, ed. by V. V. John, Bombay: April–June 1970; January–February 1972;

Quest, a Quarterly of Inquiry, Criticism and Ideas, ed. by V. V. John, A.B. Shah, Bombay: November–December 1974; March–April 1976

Quinn, Justin, Between Two Fires: Transnationalism and Cold War Poetry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198744436.001.0001

Rakesh, Mohan, ‘Interview with Mohan Rakesh’, Journal of South Asian Literature, 9. 2/3 (1973), 15–45.

Rubin, Andrew, Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

Sabin, Margery, Dissenters and Mavericks: Writings about India in English, 1765–2000 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Saunders, Frances S., The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (New York: New Press, 2013 [1999]).

Scott-Smith, Giles, The Politics of Apolitical Culture (London: Routledge, 2002), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203471739

Sethi, Devika, ‘Press Censorship in India in the 1950s’, NMML Occasional Paper (New Delhi: Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, 2015).

Sinha, K. K., ed., Boris Pasternak (Calcutta: Congress for Cultural Freedom, 1958).

The Indian PEN, ed. by Sophia Wadia, Bombay: March 1934; March 1940; March 1936; April 1936; August 1936; February 1937; June 1937; December 1940; July 1952; January 1955; April 1955; September 1955; February 1956; September 1967.

Zecchini, Laetitia, Arun Kolatkar and Literary Modernism in India (London, New York and New Delhi: Bloomsbury, 2014).

—, ‘We Were Like Cartographers, Mapping the City: An Interview with Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 53.1–2 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1080/17449855.2017.1296631

—, ‘Practices, Constructions and Deconstructions of “World Literature” and “Indian Literature” from the PEN All-India Centre to Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’, Journal of World Literature, 4.1 (2019), 81–105, https://doi.org/10.1163/24056480-00401005

—, ‘What Filters Through the Curtain: Reconsidering Indian Modernisms, Travelling Literatures, and Little Magazines in a Cold War Context’, Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 22.1–2 (2019), https//doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2019.1649183

1 This chapter is an output of the “writers and free expression” project, funded by the AHRC. I thank Ranjit Hoskote for facilitating access to the archives of the PEN at Theosophy Hall, Mumbai.

2 Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (New York: New Press, 2013 [1999], p. 49.

3 On the PEN All-India Centre, see Emma Bird, ‘A Platform for Poetry: the PEN All-India Centre and a Bombay Poetry Scene’, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 53.1–2 (2017), 207–20, and my ‘Practices, Constructions and Deconstructions of “World Literature” and “Indian Literature” from the PEN All-India Centre to Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’, Journal of World Literature, 4.1 (2019), 81–105. There are a few insightful pages on the PEN in Rosemary Marangoly George, Indian English and the Fiction of a National Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp. 32–36). The ICCF and Quest have been the object of insightful studies by the historian Eric Pullin, but literary scholars have largely ignored the journal. The only exception is Margary Sabin, to whom I am indebted for her remarkable chapter ‘The Politics of Cultural Freedom: India in the 1950s’ in Dissenters and Mavericks: Writings about India in English, 1765–2000 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 139–56.

4 Although considered as a canonical figure of Indian poetry in English, Ezekiel’s role as a cultural critic is mostly ignored.

5 ‘Poetry in the Time of Tempests’ (Times of India, 1997) in Nissim Ezekiel Remembered, ed. by Havovi Anklaseria (Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2008), p. 222.

6 Theodor W. Adorno, ‘The Essay as Form’, New German Critique, 32 (1984), 151–71.

7 Ezekiel, ‘Uncertain Certainties’ in Selected Prose (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1992), pp. 105–38.

8 Sabin, Dissenters and Mavericks, p. 139. Also see ‘Interview with Mohan Rakesh’, Journal of South Asian Literature, 9. 2–3 (1973), 15–45.

9 See Indian Congress for Cultural Freedom Proceedings, March 28–31 1951 (Bombay: Kannada Press for the Indian Congress for Cultural Freedom, 1951), p. 19.

10 A point that, following Peter Coleman, Eric Pullin and Margaret Sabin (as well as Peter Kalliney, in the African context), I make in ‘What Filters Through the Curtain: Rethinking Indian Modernisms, Travelling Literatures and Little Magazines in a Cold War Context’, Interventions, 22.2 (2020), 172–94.

11 Indian Writers in Council: Proceedings of the First All-India Writers’ Conference, ed. by Srinivas Iyengar (Bombay: PEN All-India Centre, 1947), p. 248.

12 Ezekiel, ‘Poetry in the Times of Tempests’, p. 222.

13 See International PEN’s reports on India, including Fearful Silence: the Chill on India’s Public Sphere (2016), https://pen-international.org/defending-free-expression/policy-advocacy/reports.

14 Amanda Anderson, Bleak Liberalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016, p. 21). While making a case for the complexity of liberalism, Amanda Anderson also argues for its necessary ‘unmooring’ from neoliberalism.

15 Words Andrew Rubin uses to define the agenda of the CCF (Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), p. 17.

16 Pen Charter. Resolution passed at the PEN Congress in 1927: https://pen-international.org/who-we-are/the-pen-charter

17 TIP, March 1934, p. 1.

18 Ibid., p. 1. See also my ‘Practices, Constructions and Deconstructions’, for the Indian PEN’s claims to equality, reciprocity and a more balanced world order.

19 TIP, August 1936, p. 40. Another of Sophia Wadia’s idealist editorials proclaims: ‘World-leadership must soon pass from the hands of the politician and the legislator to those of the creative writer… The pen can break every weapon of enmity, of hatred, of vanity and of pride, in the home, in society, in the nation and in the international world’ (TIP, January 1955, p. 1).

20 TIP, March 1940, p. 1.

21 TIP, August 1936, p. 40.

22 TIP, editorial on the ‘Unification of Vernacular Cultures’, April 1936, p. 19.

23 B.K. Barua, Assamese Literature (Bombay: P.E.N. All-India Centre, 1941), p. 1.

24 TIP, Editorial, ‘Literary Awards for India’, March 1936, p. 9. For a discussion of the intertextual fabric of The Indian PEN, with its notes, reviews, summaries, and features like ‘From Everywhere in India’ showcasing the achievements in the country’s vernacular literary cultures, see my ‘Practices, Constructions and Deconstructions’.

25 Indian Writers in Council, p. 41.

26 Indian Writers in Council, p. 160. An exhibition of books about the Resistance was arranged in Jaipur, with readings of poems by Louis Aragon (who was initially scheduled to travel to India), including ‘Ballade de celui qui chanta sous les supplices’, published under pseudonym in 1943 as a tribute to a tortured communist resistant.

27 Marxist Cultural Movement in India: Chronicles and Documents (1936–1947), ed. by Sudhi Pradhan (Calcutta: National Book Agency, 1979), p. 17.

28 Mulk Raj Anand, ‘On the Progressive Writers’ Movement’ in Marxist Cultural Movement, p. 3.

29 On the exclusive and hierarchical nature of the Indian PEN, see Zecchini, ‘Practices’. The language of the All-India PEN Center in the 1930s and 1940s, was inflected by Sophia Wadia’s close association with Theosophy (she and her husband B.P. Wadia founded the Bombay branch of the United Lodge of Theosophists in 1929).

30 Angare, lit. Burning Coals, was a collection of short stories written in Urdu by Ahmed Ali, Sajjad Zaheer, Rashid Jehan and Mahmuduzzafar. ‘In Defense of Angare, Shall we Submit to Gagging’ is the title of a statement drafted by Mahuduzzafar in The Leader (Allahabad) in 1933.

31 If Ahmed Ali’s championed a ‘literature brutal even in its ruggedness, without embellishments’ (cited in Marxist Cultural Movement, p. 82), many of the editorials of TIP in the 1930s and 1940s deplore the ‘licence’ of modern literature (‘trashy’ and ‘filthy’ are recurrent terms to define that writing: precisely the terms that were used to ban Angare).

32 The PWA is cited as one of the affiliated organizations of the 1945 All-India Writers conference in Jaipur.

33 Carlo Coppola, in his otherwise groundbreaking book, is dismissive of Sophia Wadia, whose ‘Indianness’ acquired by ‘marriage rather than by heritage’ he also questions (Urdu Poetry, 1935–1970, The Progressive Episode, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 101).

34 TIP, December 1940, p. 157.

35 TIP, June 1937, p. 46.

36 Ibid.

37 TIP, August 1936, p. 41.

38 ICCF Proceedings, p. 284.

39 Ibid., p. 5.

40 As Megan Doherty suggested, it is precisely because of PEN’s championing of the a-politicality of literature, that the organization could be manipulated by the CIA which deployed the idea of artistic ‘autonomy’ as a token of ideological independence, and anti-totalitarianism; © Megan Doherty, “A Guardian to Literature and its Cousins: The Early Politics of the PEN”, Nederlandse Letterkunde 16 (2011), 132–51; see also Giles Scott-Smith, The Politics of Apolitical Culture (London: Routledge, 2002).

41 Words of the PEN Charter, op. cit.

42 TIP, February 1956, p. 39.

43 The PEN All-India Centre in fact received funds from organizations like the anti-communist ‘Asia Foundation’, created in 1951. The Indian PEN and USIS (the overseas service of the United State Information Agency) also regularly collaborated. When news of CIA involvement in the CCF and other cultural organizations became known, TIP published Arthur Carver’s ‘Categorical Disclaimer’ to dispel ‘false rumours’ of CIA sources augmenting International PEN’s income (September 1967, p. 262).

44 TIP, Editorial ‘A Cooperative Enterprise’, February 1937, p. 9.

45 TIP, July 1952, p. 100.

46 TIP, September 1955, p. 305.

47 Although it is important to keep in mind that various agendas and strains coexisted within the CCF. Many CCF liberals, for instance, were as opposed to communism as they were to capitalism, or (in the US) to McCarthyism.