10. India: Learning Challenges for the Marginalized

© 2022 Chapter Authors, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0256.10

Introduction

There are numerous sources of inequality in India–linguistic, economic, sociocultural, class, and caste. In this chapter, we examine the heterogeneities and inequalities that characterize India and impact learning at bottom of its pyramid (BOP), focusing primarily on linguistic diversity and mother-tongue instruction.

India’s people speak many languages, including 3592 numerically weak mother-tongues used by 705 tribes or ethnic groups, and 1284 castes scattered across the country’s mostly rural landscape. Across 36 states and union territories of India there are 739 districts1 and 5,572 sub-districts.2 There are 7,935 urban areas3 (4,041 statutory and 3,894 census towns) housing 31 percent of Indians (which is much lower by world standards) and 649,481 villages4 often located in remote subdistricts5 that support 68 percent of the population. According to the census in 2011, the number of urban agglomerations (with populations of over 100,000) stood at 474. Managing teaching and learning across this vast space poses many challenges and opportunities.

The biggest challenge comes from multilingual or pluricultural learning situations. Nearly 96 percent of India’s mother-tongues are spoken by only 4 percent of the population. Plans for early grade education, textbook production, teacher-training programs, and so on, often do not take into account these linguistic minorities, despite constitutional provisions that require schools to impart education in everyone’s mother-tongue. As a result, there are many smaller groups who must learn to read in “other”-tongues, and therefore fail almost invariably. Periodic national assessments of children’s learning conducted by the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), which tests children both in school and out of school, and the National Achievement Survey consistently highlight the sub-par academic capacities of these children, especially in foundational reading and numeracy in the state language.

Such diverse classrooms can be found not only in state-run schools of different types, but also in private schools, except that in most privately managed institutions, a monolingual regime is imposed from the top. There is often a vast linguistic distance between the “ideal” or the “standard” language the school systems expect all students to master vs. the dialectal or mother-tongue background of many students. The students coming to a city school from the districts are as challenged in this respect, as are the urban students coming from a certain class background. In many instances, the students from divergent backgrounds are able to “comprehend” academic language, but find it difficult to acquire fluency of speech or the standard pronunciation.

These challenges only increase as children become young adults who only possess an elementary level of reading and writing because of these previous challenges. Their advantage, unlike many adult learners, is that they are less afraid of making mistakes. Assuming that none of them have speech disabilities or difficulties in pronunciation because of their base language influence, their teachers need to work on what could be done to improve their processes of learning, or how sociocultural and sociolinguistic barriers could be overcome to infuse confidence in them. However, getting the right kind (and quantity) of teachers or instructors is another major challenge. A trained and patient teacher can go a long way towards helping a struggling child or young adult overcome linguistic barriers, but many teachers are not sufficiently sensitive to this issue.

Another challenge is that, in the Indian Constitution, each of the 36 states (and Union Territories) has the right to come up with its own education policy vis-à-vis use of mother-tongues in elementary schools. Even as the “Right to Education” (RTE) was accepted as a legal instrument, there were numerous cases filed in different high courts about the policies of different state governments with respect to mother-tongue education. In the post-independence period, the States Reorganization Commission (SRC) of India reviewed this question based on linguistic principles. Thus, language diversity increased as more and more states were carved out of the existing huge provinces.

Managing a diversity of languages and cultures is perhaps the biggest challenge for education in India. Howarth and Andreouli’s (2016) book Nobody Wants to Be an Outsider is valid today: they question how we can manage diversity so that it becomes a source of mutual enrichment rather than conflict, especially when “societies cannot manage cultural diversity due to assumed incompatibility” (Chryssochoou, 2014). The nature of globalized communities encourages dialogue and interactions across different sets of people. As societies diversify, psychological analysis shows that our identities become populated with “multiple selves” to respond to these complexities. Given this scenario, it is interesting to see if these heterogeneities also affect the bottom of our societies today. One may be a resident of Delhi living in the not-so-affluent colonies and settlement areas, but may also use one’s identity as a Bihari where it may work, or may show allegiance to Bhojpuri speech community that would cut across several states, and make one a member of a larger network.

Heterogeneity at the “bottom of the pyramid”

The Indian population can be divided in myriad ways—by language, culture, socioeconomic conditions, religion, and gender, amongst others. The sheer number of tribes, castes, ethnic communities, speech groups, and mother-tongues active in a pluricultural India is immense. Language roles and their differences in power add to the complexities at the bottom of the pyramid. Some are immensely successful in the market, such as Hindi, Marathi, or Malayalam, while others are left behind. The languages on the margin (Singh et al., 2017) are viewed in much the same way economists view “the forgotten man at the bottom of economic pyramid” (Roosevelt, 1932). Of course, in this metaphoric “pyramid” what is on top is considered a dominant force or a commanding voice while the bottom remains powerless. Those at the “bottom of the pyramid” may feel alienated for different reasons, but a lack of opportunities and economic deprivation are the common factors for all of them. The learning issues of the children of these marginalized families need to be understood in the context of this heterogeneity.

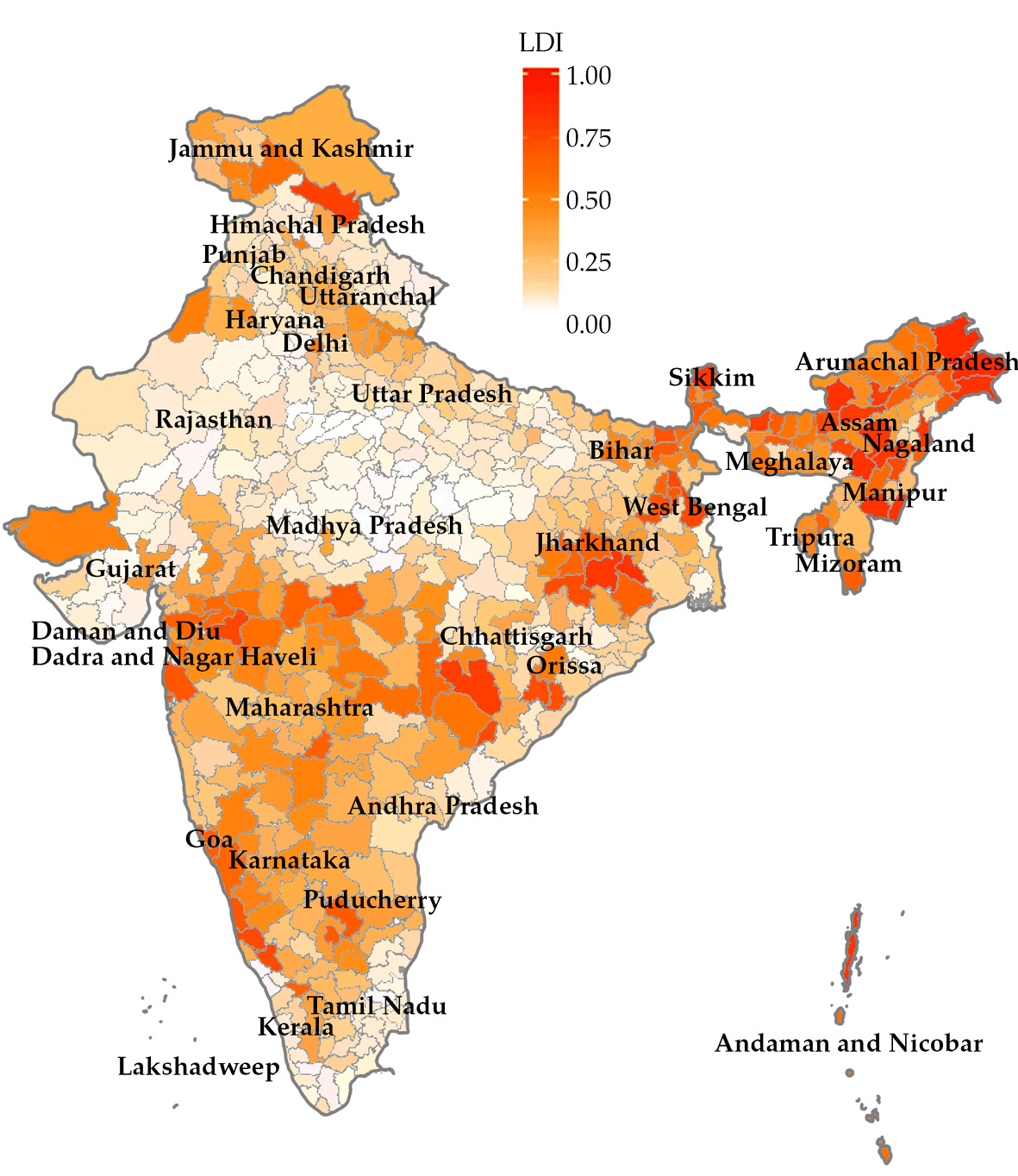

At the bottom of the hierarchy in India is a set of heterogenous, under-developed, scantily published, and unprofitable (in terms of the market) speech communities, ethnic groups with thinning numbers, and scheduled castes that are both socioeconomically and culturally excluded. If we set aside the problems of methodology and accuracy with how one counts “languages”, the sheer number of mother-tongues in India is intimidating: Sir George Abraham Grierson’s Linguistic Survey of India (1903–1923) documented 179 languages and 544 dialects, while early census reports (1921) showed 188 languages. Post-independence, the 1961 census reports mentioned a total of 1,652 “mother-tongues” which kept on increasing until we reached the census in 2011.6 Other sources, such as People of India—the Anthropological Survey of India,7 identified 75 “major languages” out of a total of 325 languages used in Indian households, and the Ethnologue8 reported 398 languages, including 387 living and 11 extinct languages. Despite a lack of consensus on the language count, it is clear that the linguistic landscape is diverse. Using Greenberg’s (1956) Linguistic Diversity Index (LDI), which measures the probability of two people selected from the population at random speaking different mother-tongues—ranging from 0 (everyone has the same mother-tongue) to 1 (no two people have the same mother tongue)—India ranks 9th out of 209 countries with an index of 0.930 (UNESCO, 2009). A visualization of India’s linguistic diversity based on LDI is shown in Figure 1 below (Singh, 2018):

Fig. 1. Linguistic diversity index of India.

In India, language families roughly coincide with broad geographic division of the subcontinent, although their growth pattern shows the differences as Figure 2 below does:

Fig. 2. Distribution of languages in India—comparative strength. Source: the authors.

The number of “castes” (usually referred to as “scheduled castes”, or SCs) and tribes in the country is more numerous than the language count; the government of India’s Scheduled Castes Order 19369 (Gazette of India on June 6, 1936) lists 16.23 percent of people categorized into 428 castes. This has now grown upwards to 1284 castes under Article 341 of the Constitution (cf. Table 1.2.8 in Handbook).

Article 366 (25) defines “scheduled tribes” as “such tribes or tribal communities or parts of or groups within such tribes or tribal communities as are deemed under Article 342 to be Scheduled Tribes for the purposes of this constitution”. One could, of course, question their identification methods, but after the census in 1931 identified them based on indications of primitive traits, distinctive culture, geographical isolation, shyness of contact with the community at large, and backwardness, this was reiterated in the Reports of First Backward Classes Commission (1955), the Advisory Committee (Kalelkar), on Revision of SC/ST lists (Lokur Committee, 1965), the Joint Committee of Parliament on the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Orders (Amendment) Bill (1967), and the Chanda Committee (1969). The 30 Indian states that have reported these tribes show that they constitute 8.6 percent of our total population, over 100 million people, and 705 distinct tribes. The IWGIA (International Work Groups for Indigenous Affairs), a Copenhagen-based human rights group, claims that: “In India, there are 705 ethnic groups officially recognized as ‘Scheduled Tribes,’ although there are several ethnic groups that are also considered Scheduled Tribes, but are not officially recognized”. 10

There is diversity in religious practices as well. Although 79.8 percent of people in India are, broadly speaking, followers of Hinduism, India also houses more than 172 million Muslims, comprising 14.2 percent of the population—making it one of the world’s largest Muslim populations. The population also includes the following smaller religious minorities: Christian (2.3 percent), Sikh (1.7 percent), Buddhist (0.7 percent), Jains (0.4 percent), and other (0.9 percent).

McKinsey’s 2007 report shows that roughly five out of every six Indians have an annual income of less that INR 200,000. Thus, 997 million people, (or 80 percent of the population) are at the bottom of the economic pyramid. For those in the urban areas, one may have to say that the qualifying income bracket is about INR 300,000, and those in the rural area earning below INR 160,000 could be included.

Amongst this diversity, implementing inclusive socioeconomic growth and prosperity becomes a great challenge. The current predominant emphasis on curriculum, syllabus, and enrollment has propagated an environment that is not learner-centric. Instead of promoting child-friendly and child-centric educational opportunities, the current system is more administration friendly. The Indian government’s mantra of Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas (“development for all”) which is the cornerstone of its National Education Policy (2019) is generally oblivious to children’s varying needs and non-uniform learning trajectories.

Weakness of “mother-tongues” and Education for All

Given this background, the core tenets of Education for All—namely the right to attend school and learn one’s mother-tongue—become practically meaningless pronouncements. As the UNESCO 2013 report rightly observed, for inclusive education to become a reality, the world education scene needs to undergo a systemic change. Quoting a World Bank Report of 2016, Roche (2016, p. 131–132) observes that “not only is lack of education generally recognized as a cause of poverty, it has come to be recognized as one of three core dimensions alongside living standard and health”. Despite strong economic growth in countries with high per-capita GDP, poverty continues to persist, which has encouraged many observers to doubt the meaning of “development”.

In implementing many of the ideal programs and curricula, the problems are twofold: there are quite diverse school populations, containing children and guardians from varied backgrounds; rural-urban immigration and displacement could also increase variation. As Ghiso (2013, p. 23) observes, “educators themselves are cultural beings… their backgrounds may be useful in promoting multicultural learning and global sensitivity in early childhood classrooms”. Experiments with children as collaborators (Kirmani, 2007) have yielded success, although in small-scale environments.

Teachers who are aware of the local context are therefore necessary. Recruitment of teachers across India’s government schools is currently not sufficiently decentralized to meet this demand. Additionally, there is a great need to construct school environments that encourage culturally responsible learning and help children retain and evolve their own identities, so as to create a pluralistic school education space, and develop close home-school partnerships for successful school-based learning outcomes. It is well-known that the public schools in India are constrained by budget.

Ejele (2016, p. 141) comments that Western development ideals often promote the belief that multilingual and multicultural societies are “prone to the ‘inevitable clash of cultures and civilizations’”. These non-harmonious sentiments are echoed by Huntington’s (1993) Clash of Civilizations thesis as well. However, according to Annamalai (1995, p. 216), the Indian experience shows the opposite: “Europe promoted monolingualism as part of nation formation… This contrasts, for instance, with the situation in India, where contact with the English language, via colonisation, did not result in language loss, but triggered renaissance in the major Indian languages…”. There are also alternative positions, such as that of Appadurai (1996), who would say that the margins are where languages and cultures interact and allow greater understandings to develop, giving rise to spaces for creativity.

Nevertheless, in the real world, there aren’t many incentives for supporting non-market-friendly heterogeneity. This coexistence of a large number of marginalized people governed by majority communities is a source of constant tension and political negotiation. While the language of education may not be a practical means of promoting marginalized cultural dimensions, including the knowledge system of marginalized communities would only enrich the education of India’s children.

Empowering marginalized learners

“Marginality” refers to an uncontrolled and involuntary position that a group finds itself in with respect to sociopolitical, cultural, economic, ecological, and biophysical systems. Such groups are unable to or are not permitted to access the resources available to all other groups, or to assets and public services. Thus, the marginal groups are restrained in using their freedom of choice, which in turn affects their capabilities, and delays their development, causing them to remain on the margin within the confines of poverty. The Centre for Development Research11 tells us that although global poverty has decreased substantially, the ultra-poor are now concentrated in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Even though India has seen rapid economic growth, poverty still affects a large proportion of the population. In this matter, the lingua-ethnic minority groups have suffered the most. Using evidence from the Sustainable Development Goals Index released by Niti Aayog and the UN, Khan (2020) showcases worrying trends that “India is losing its footing in key areas such as poverty alleviation, ending hunger, economic growth, and preserving life on land. It’s a setback for the country’s efforts to rapidly raise standards of living”.

For any planned “sociocultural development”, the thrust must be on empowerment of the marginalized. Once empowered, those at the bottom of the ladder have the freedom of choice and social action. Tagore, one of India’s premier educationists, had a deep dissatisfaction for the hodgepodge that emerged in the name of modern education in India, which led him to conceive of a practical form of “de-schooling” reflected in the practices at Viswa-Bharati. He tried to build a true human community with no marginalization.12 Tagore was not alone in this goal Freire’s Critical Pedagogy approach promoted emancipation of students and learning (Freire 2000; 2007; Freire & Faundez, 1989). Critical Pedagogy aimed at guiding students to become responsible members of a society where the voices and opinions of the marginalized are also heard. “Through these opportunities, students can comprehend their position in society and they can take positive steps to amend their society and ultimately eliminate problems, inequities, and oppressions in their future life” (Mahmoudi, Khoshnood, & Babaei, 2014, p. 86). In fact, the Critical Pedagogy approach aims at encouraging learners not only to interpret the situation and understand the problems, but also to develop the much-needed critical consciousness that is so crucial to changing the world. Those at the BOP then would be encouraged to intervene in the affairs of their society and culture to make a difference. Once this leadership or ownership is accepted by those at the bottom, one may see many changes in mitigating the problems.

Mitigation of challenges: Recommendations

Language and education planners in India must come up with plans and strategies to manage and celebrate diversities in schools, rather than only depending on legal mandates to teach several languages in schools. How education can liberate India from the seemingly inevitable problems of poverty, unemployment, environmental degradation, violence, and so forth, was a concern of the visionaries of India’s past—Gandhi, Tagore, Sri Aurobindo, and Jiddu Krishnamurti, among others. In their writings and their experiments, each one of them tried to envision a better reality for India, one unmarred by the greed and destruction associated with the Western model of development, facilitated by the Western style of schooling. They believed that India could only grow and regenerate itself by seeking out those tried and tested beliefs, values, languages, cultures, knowledge, and wisdom upon which it had developed and lived for a long time.

Policies that systemically promote marketable skills and employability of learners within a socially inclusive framework can act as catalytic force to fulfil the priorities of NEP 2019 and SDG4. We present here a tentative model that can ensure universal quality education based on “bottom of the pyramid” framework:

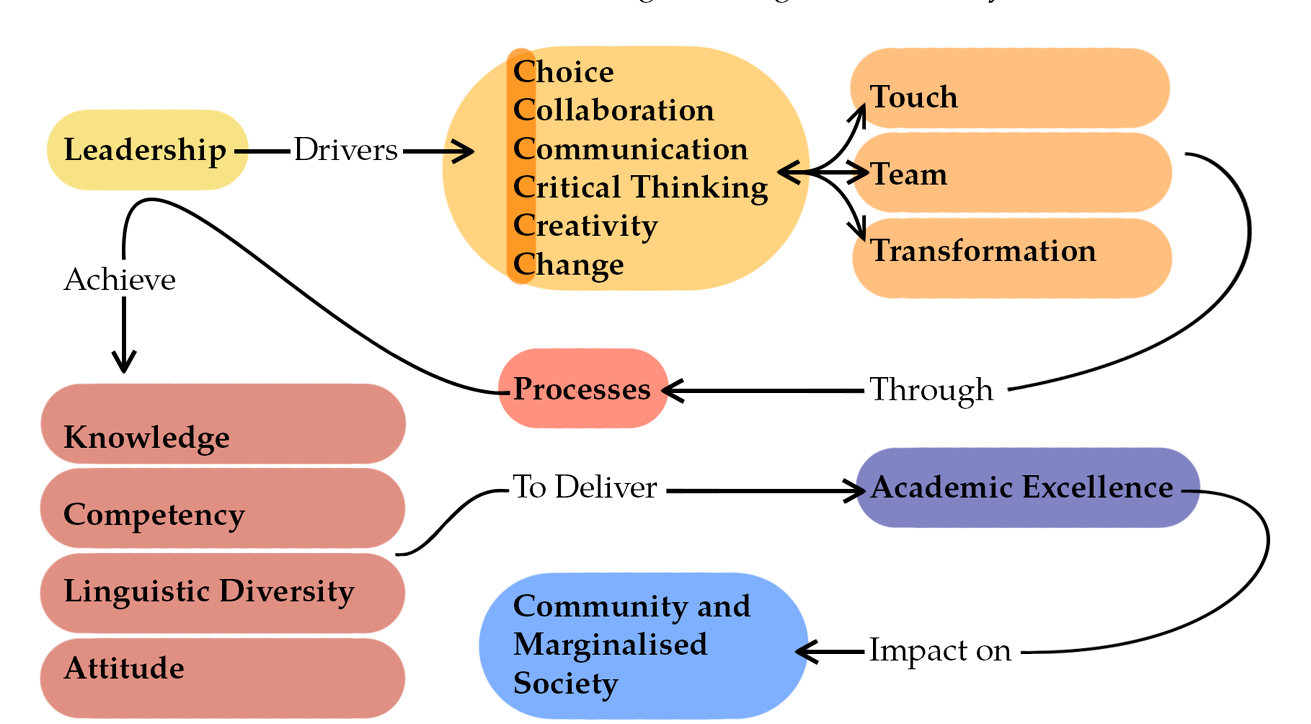

Fig. 3. A model of learning in diverse linguistic contexts of India. Source: based on the work of P. Banerjee (co-author).

The model integrates the six Cs (choice, collaboration, communication, critical thinking, creativity, and change management) along with academic excellence and leadership traits. The model promotes the use of mother-tongue communication to improve the targeting of socially underprivileged and marginalized populations and bring them into the “educational mainstream”. Harmonizing the educational expectations and standards across the different states and central boards of education would surely help in educational mainstreaming.

The foremost component of the 6C model is “choice”. In the model, the learning pathway is chosen by the student, or by the parents on their behalf, depending upon their ability, aptitude, and interest. Teachers design and develop the curriculum based on the directions of an academic leader or mentor who influences the choice to move in a particular direction when there are diverse course options.

An important component of the 6C model is “collaboration”. The primary focus is on mutual efforts and activities worldwide, keeping in mind processes that create academic excellence in ideal schools. Technology could be an accelerator for this kind of education, given the variety and accessibility of options. This entire process is planned and handled by teachers to help learners become more communicative. The term “change” refers to the fact that change is unavoidable as the learners’ progress. Repetitive teaching of expressions and “vocables” (that are in the process of becoming “vocabulary” for these learners), often introduced through rhymes, poems, and role-playing at the elementary level, can be one method.

The six Cs of the model are strengthened by touch, team, and transformation, where touch refers to the teacher’s investment, team refers to the group effort required for knowledge creation, and transformation to the changing paradigms of teaching and learning and the role of a teacher (Banerjee et. al., 2019).

In conjunction with the above-stated approach, there is also a need to institutionalize inclusive education by involving communities, social workers, other students, and volunteers. Here, inclusive education “involves the right to education for all students… and revolve[s] around fellowship, participation, democratization, benefit, equal access, quality, equity and justice” (Haug, 2017, p. 206). Even though there is some degree of uncertainty about defining “inclusive education” across countries, there is no doubt about the necessity of securing quality education for every learner.

To begin tackling the challenge of educational disparity, one could harness a well-devised technology-driven solution, which could promote the inclusion of marginalized populations in accordance with the Digital India Campaign, Fourth Industrial Revolution as propounded by 10th BRICS Annual Summit Joint Statement, SDG4 and 8.

Lastly, to make any universal education framework successful, there is an urgent need to foster a vibrant and holistic educational environment as envisaged by NEP 2019 and SDG4, especially in primary and secondary schools, by instituting smart classrooms, libraries, laboratories, auditoriums, and playgrounds, among other things. Explaining to students the purpose of education—and that their attempts to succeed will only reflect positively in their own lives—is important. In addition to creating a climate of positivity and safety where risk-taking is encouraged, such tactics would create an open and authentic conversation where trust and respect are fostered, making learning “relevant” to the students. Loveless (2020) shows that these strategies could have a number of results and manifestations such as:

- Establishment of a good feeling and development of positive self-image;

- Positive wellness-related actions such as nutrition, exercise, and sleep;

- Actions leading to problem-solving, decision-making, and thinking skills;

- Inculcating empathetic and respectful feelings towards others;

- Positive actions in both time management and managing emotions;

- Positive actions such as admitting mistakes and taking responsibilities for actions; and

- Help in goal-setting, leading to personal growth and improvement.

Concluding remarks

We have examined the nature of heterogeneities and inequalities in India that are based on linguistic, economic, sociocultural, class, and caste-based factors. Given this diversity, planning for early grade education or preparing teachers and textbooks are huge challenges, no matter what constitutional provisions are made. Variations across regions and communities have emerged (even after ASER and the National Achievement Surveys) which, coupled with economic, political, and psychological barriers, have led to deprived marginalized communities.

We have identified several challenges and have argued that academic, socioeconomic, and psychological support systems that account for India’s heterogenous populace can enhance behavioral and learning competencies, leading to resilience and lifelong learning of children. However, since so many people in India are often juggling multiple identities, what we need is an efficient and responsible system of diversity management. It will be important for our teacher education managers to keep in mind how intercultural tensions could be turned into interethnic bonds.

References

Annamalai, E. (1995). Multilingualism for all: An Indian perspective. In T. Skutnabb-Kangas (Ed.). Multilingualism for all: European studies on multilingualism (pp. 215–219). Lisse, the Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization (Public Worlds Series). Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Banerjee, P., Ludwikowaska, K., Adhikari, B., & Bandyopadhyay, R. (2020). 6C model of leadership excellence in higher education. In Academic Leadership Framework for Sustainable Environment: Capacity Building in Higher Education (pp. 11–27). Warsaw: Diffin, SA.

Chryssochoou, X. (2014). Identity processes in culturally diverse societies: How cultural diversity is reflected in the self. In R. Jaspal & G.M. Breakwell (Eds.), Identity process theory: Identity, social action and social change (pp. 135–154). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ejele, P. E. (2016). The challenges of linguistic and cultural diversities as the common heritage of humanity: The Nigerian experience. In O. Ndimele (Ed.), Convergence: English and Nigerian languages: A festschrift for Munzali A. Jibril (pp. 141–158). M & J Grand Orbit Communications.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. Bergman Ramos, Trans.). New York: Continuum (Original work published 1996).

Freire, P. (2007). Critical education in the new information. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Freire, P., & Faundez, A., (1989). Learning to question. New York: Continuum.

Ghiso, M. P. (2013). Every language is special: Promoting dual language learning in multicultural primary schools. YC Young Children, 68(1), 22–26.

Greenberg, J. H. (1956). The measurement of linguistic diversity. Language, 32(1), 109–115.

Haug, P. (2017). Understanding inclusive education: Ideals and reality. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 19(3), 206–217.

Howarth, C., & Andreouli, E. (2016). “Nobody wants to be an outsider”: From diversity management to diversity engagement. Political Psychology, 37(3), 327–340.

Huntington, S. P. (1993). The clash of civilizations? Foreign Affairs, 72, 22–49.

Khan, M. (2020). Cloud over India’s growth story: Poverty and inequality rose in most states in 2019. ET Prime. https://prime.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/74232740/economy-and-policy/cloud-over-indias-growth-story-poverty-and-inequality-rose-in-most-states-in-2019

Kirmani, M. H. (2007). Empowering culturally and linguistically diverse children and families. YC Young Children, 62(6), 94–98.

Loveless, B. (2020). Strategies for building a productive and positive learning environment. educationcorner.com

Roche, S. (2016). Introduction: Education for all: Exploring the principle and process of inclusive education. International Review of Education, 62(2), 131–137.

Singh, K. S. (Ed.). (1993). Tribal ethnography, customary law, and change. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Singh, R. (2018) Choosing the right path: People, development and languages (Plenary talk given at the National Seminar-Cum-Workshop on Revitalization of Heritage Languages and Culture with Special Reference to the NER). Amity University Haryana, Gurugram & Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi.

Singh, U. N. (2009) Status of lesser-known languages of India. In A. Saxena & L. Borin (Eds.) Lesser-known languages in South Asia: Status and policies, case studies and applications of information technology. Mouton de Gruyter.

Singh, U. N. (2010). Erosion of cultural and linguistic bases in South Asia (Keynote address, 21st ECMSAS). Universität Bonn; Institut für Orient und sienwissenschaften Abteilung für Indologie, Germany.

Singh, U. N. (2014). Education and what it does to us. Visva-Bharati Quarterly. Santiniketan: Visva-Bharati.

UNESCO. (2009). Policy guidelines on inclusion in education (ED.2009/WS/31). Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2013). Inclusive education (Education sector technical notes). Paris: UNESCO.

1 “Districts | Government of India Web Directory”. www.goidirectory.gov.in. Census 2011 shows 640 and Census 2001 has the figure 593 for districts. There are 687 unique names and others are similar or identical names.

3 http://mohua.gov.in/pdf/5c80e2225a124Handbook%20of%20Urban%20Statistics%202019.pdf. According to the World Urbanization Prospects, 2018, 55.29 percent of the world population lived in urban areas in 2018 as compared to 34.03 percent in India in 2018.

4 As per the census in 2011, out of which 593,615 are inhabited; IMIS database pegs it at 608,662, SBM-G at 605,805.

5 The subdistricts are known by different names – sometimes called Tehsils or Talukas, or Mandals (Andhra Pradesh and Telengana), Circles, C.D. Block (Bihar, Tripura, Meghalaya, West Bengal and Jharkhand), R.D. Block (Mizoram), Commune Panchayats (Pondicherry), and Subdivisions (Lakshadweep and Arunachal Pradesh), and even Police Stations (Odisha).

6 The unclarity with respect to the concept of “mother-tongue” arose because the Indian Census authorities had passed on different instructions to the ground-level enumerators. The emphasis in the censuses in 1881 and 1891 was on counting mother-tongues “ordinarily spoken in the household”. In 1901, enumerators were instructed to record names of languages “ordinarily used”. This was extended to mother-tongues “ordinarily used in his own home” in 1911 and 1921. In 1931, and 1951, it was stipulated as the language first spoken “from the cradle”.

7 Singh (1993).