9. Maud Gonne, and Yeats as Petrarchan Lover

© 2021 Patrick Keane, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0275.10

Like most love poems in the West, Yeats’s Maud Gonne lyrics are in the Petrarchan tradition. James Longenbach, who has written on Yeats and, as both practitioner and critic, on poetic form, observed in 2004 that, ‘to read love poetry—to speak of the language of love—is to read Petrarch, who is largely responsible for inventing what W. B. Yeats called ‘the old high way of love.’1 He is quoting from one of the pivotal Maud Gonne poems, ‘Adam’s Curse,’ a poem as much about, and beautifully demonstrating, lyric craftsmanship, as it is about the travail of unrequited love. As Longenbach is hardly alone in recognizing, Yeats conceived of Maud, unique though she was, as yet another kind yet inevitably cruel and inaccessible domina in the Medieval and Renaissance courtly love tradition:

I had a thought for no one’s but your ears:

That you were beautiful, and that I strove

To love you in the old high way of love;

That it had all seemed happy, and yet we’d grown

As weary-hearted as that hollow moon.

This elegiac evening scene, with love faded beneath a ‘hollow’ moon, is gentle; but the Maud Gonne we encounter more often than not in the poems to and about her is a more violent cousin of Petrarch’s Laura, and of the even more famously unattainable Beatrice of Dante, a Dante whose iconically gaunt cheek was ‘hollowed,’ in Yeats’s telling (in his 1917 dialogue-poem ‘Ego Dominus Tuus’), by his ‘hunger for the apple on the bough/ Most out of reach’—Sappho’s simile, as translated by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (‘Like the sweet apple which reddens upon the topmost bough’ beyond the reach of pickers, Fragment 105A, titled by Rossetti ‘One Girl’). As I will suggest when we return to ‘Adam’s Curse,’ Yeats also has in mind Sir Philip Sidney’s sonnet-sequence, Astrophil and Stella, whose immortal ‘Stella’ is based (almost as transparently as Astrophil is on Philip Sidney) on the Elizabethan court-‘star’ Penelope Rich, a beauty engaged, like Maud, in dangerous political intrigue. She was a Muse with whom Sidney, unlike Dante, Petrarch, and Yeats, may not actually have been in love, but who compelled him, as a Petrarchan poet, to adopt the artifice of courtly love ‘invention’ (a word thrice repeated in the famous opening sonnet), before he is told by his Muse to ‘looke in thy heart and write.’2

‘Beloved, gaze in thine own heart,’ Yeats begins and ends the opening movement of the esoteric and yet personal Rose poem, ‘The Two Trees.’ The benign tree, holy, rooted in joy and quiet, is growing in her heart; if she looks therein, her ‘eyes grow full of tender care.’ But there is also its antithesis, a malignant tree, its ‘fatal image’ of ‘stormy night’ and ‘barrenness’ reflected in her mirror (a looking glass very different from the one in ‘Michael Robartes and the Dancer’). She is warned, at the beginning and end of the poem’s second and final movement, to ‘Gaze no more in the bitter glass,’ lest her ‘tender eyes grow all unkind.’ Beneath the Cabbalistic and Blakean foliage of the poem, and the Muse-stereotypes of a beloved’s alternately kind and unkind eyes, Yeats is addressing two opposing aspects of the actual Maud Gonne, who was capable of tender care, and susceptible, politically, to the storm-tossed and ultimately barren abstract hatred that could make her ‘tender eyes grow all unkind.’ Yeats didn’t have to invent a Muse of double and divided aspect. He already had one in Maud Gonne. That is obvious from many of Yeats’s poems to and about her, culminating in the stern-eyed ‘A Bronze Head,’ but also from some of the life choices of the ‘real’ Maud.

Nevertheless, that Maud Gonne, however real, was also, in part, Yeats’s ‘invention,’ is graphically illustrated in two flanking texts of 1903, written before and after she had shocked Yeats by informing him (speaking of bad life choices) that she had decided to wed. She had often told him that she would not marry him—for which the world should ‘thank me’ because ‘you make such beautiful poetry out of what you call your unhappiness’—an axiom for denying herself to him, though she happens to have been largely right. But she had also assured him that she would marry no one else. The plan to wed MacBride violated that repeated ‘deep-sworn vow,’ later immortalized in Yeats’s concise, powerful poem of that title. The first of the two texts I referred to is a letter written just before the marriage; the second a poem, ‘Old Memory,’ written after that debacle. I will return to both; it is enough for now to describe the letter as one of bitter recrimination, written in a desperate attempt to stave off the impending union of Maud with Captain John MacBride, a hero of the Irish Brigade that had fought against the British in the Boer War. It was a marriage, Yeats insisted, ‘beneath her’ in every way: not only a betrayal of herself and her Anglo-Irish ‘class,’ but of him, personally and in terms of public humiliation.

He had elevated her in his poetry to the heroic status of a Greek or Celtic goddess reborn, and as a modern Helen of Troy; above all, he had presented her to the world as a woman as aloof and unattainable as the worshiped ladies of the courtly love tradition in whose virginal company he had poetically enlisted her. By marrying MacBride—vulgar, violent, and Catholic (from Yeats’s Protestant perspective, a religion of censorship and of opposition to the Irish nationalism both he and Maud espoused, he constitutionally, she by whatever means necessary)—Maud was not only throwing herself away, he charged, but trashing the image he had labored long and successfully to put before the public.

In ‘Old Memory,’ the first lyric he could bring himself to write in the numbed aftermath of that marriage, Yeats is even more possessive, an impresario jealously protecting an investment, or a publisher a copyright. Here, Maud’s aristocratic and oxymoronic nobility—‘Your strength so lofty, fierce and kind,/ It might call up a new age,’ evoking ‘queens that were imagined long ago’—is, he tells her, only ‘half yours.’ Echoing Wordsworth as ‘lover’ of the ‘world of eye, and ear—both what they half create,/ And what perceive’ (‘Tintern Abbey,’ lines 102–7), Yeats claims that the ‘Maud Gonne’ persona was half-created by himself: a suffering unrequited lover and skilled artist who ‘kneaded in the dough/ Through the long years of youth,’ and, like a secular Yahweh, brought forth the iconic image of a solitary, heroic, and above all, unattainable Muse.

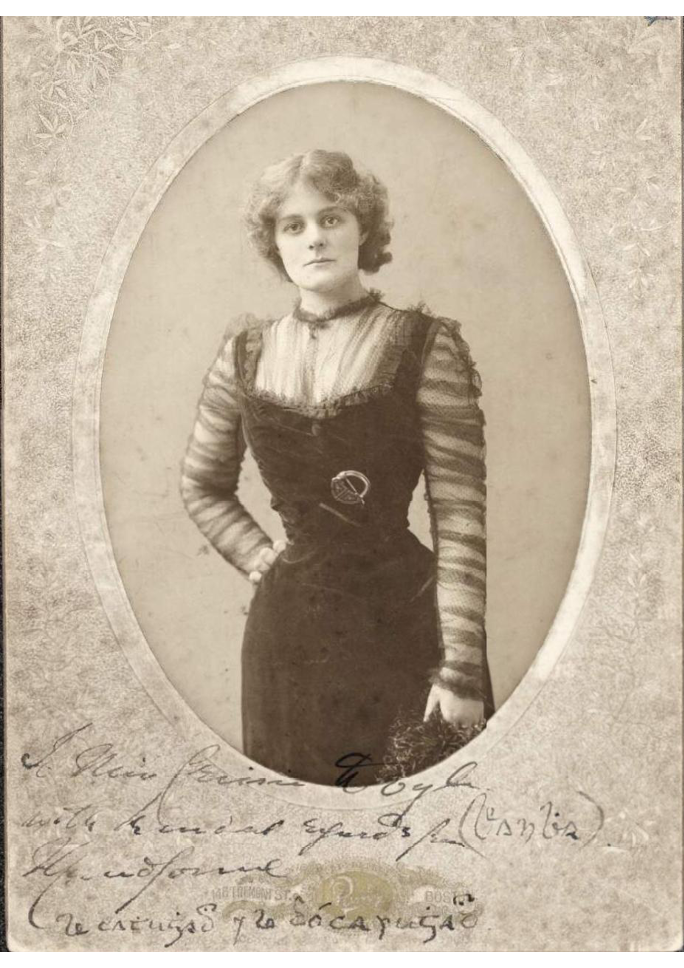

Of course, fourteen years earlier, before she had publicly sullied the image by marriage to ‘a drunken, vainglorious lout’ (Yeats’s accurate depiction of MacBride even in later honoring his memory as one of the executed Easter 1916 leaders), there was the seemingly untarnished and instantly idealized Maud: the stunning beauty Yeats fell in love with at first sight when, under the auspices of the old Fenian hero, John O’Leary, she swept exuberantly into the Yeats family home in Bedford Park. Maud had come, bearing an introduction from O’Leary’s sister, ostensibly to visit Yeats’s artist father; but, as Yeats’s wary sister Lolly accurately surmised, ‘really to see Willie,’ whose just-published The Wanderings of Oisin she had read with enthusiasm. He seemed a promising talent to be enlisted in Ireland’s cause. Both sisters were annoyed by Maud’s ‘royal sort of smile,’ and, as a family with little cash, noticed that the independently wealthy Maud (heiress to a portion of her grandfather’s huge fortune) extravagantly kept her hansom cab waiting for the entirety of her visit.3

As for the young poet, he recorded twenty years later in private notes that he ‘had never thought to see in a woman so great beauty. It belonged to famous pictures, to poetry, to some legendary past. A complexion like the blossom of apples, and yet face and body had the beauty of lineaments which Blake calls the highest beauty because it changes least from youth to age, and a stature so great that she seemed of a divine race.’ That first meeting evoked ‘overpowering tumult that had yet many pleasant secondary notes.’ On that day, 30 January 1889, the ‘troubling of my life began.’4 With the retrospect of twenty years, in his 1909 essay ‘The Tragic Theatre,’ Yeats acknowledged an element of self-consciousness in his idealization of Maud. ‘When we love,’ he asked rhetorically, ‘if it be in the excitement of youth, do we not also’ exclude little ‘irrelevancies’ of character, in order to emphasize the mysterious, archetypal personality. We do so ‘by choosing that beauty which seems unearthly because the individual woman is lost amid the labyrinth of its lines as though life were trembling into stillness and silence, or at last folding itself away’ (E&I, 243–44).

Given my title and the emphasis already placed on Maud Gonne, that ‘woman lost,’ as ‘a great labyrinth’ from which the long-ensnared poet admits having ‘turned aside,’ a brief turning aside in the form of digression may be in order. The recurrent image of the labyrinth is one of internalization, in which one is self-enfolded, either protected or ‘lost.’ A year after he made the remarks just quoted from ‘The Tragic Theatre,’ Yeats described Maud, in the poem ‘Against Unworthy Praise,’ as being secreted within ‘the labyrinth of her days/ That her own strangeness perplexed.’ In the great sequence ‘Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen,’ we are told that ‘A man in his own secret meditation /Is lost amid the labyrinth he has made/ In art or politics,’ and in that sequence’s tumultuous coda, chaos attends the cyclical and occult return of Herodias’ crazed daughters, ‘their purpose [lost] in the labyrinth of the wind.’ Perplexity, being lost, caught up in a maze or whirlwind of violence the ‘purpose’ of which is difficult to discern: all seems concentrated in the image of Maud Gonne. Politely but firmly rejecting the protection Yeats offered in 1898, she wrote that she was ‘under the great shield of Lugh,’ and ‘should not need and could not accept protection from any one,’ though she fully realized and understood ‘the generous and unselfish thoughts which were in [his] heart.’ She continued, ‘I love you for them […]. I am in my whirlwind, but in the midst of that whirlwind is dead quiet calm which is peace too.’5 In the eye of the storm, Yeats’s ‘labyrinth of the wind,’ Maud also seems a Daedalian ‘great labyrinth,’ herself anything but peaceful: the devouring minotaur at the center, half-divine, double-gendered, a creature both spiritual and driven by instinct, and with an appetite for violence.

For all its fusion of opposites, the minotaur is a monster, hardly young Yeats’s initial impression of Maud Gonne. After that life-changing first meeting, he remained in virginal thrall for a decade, and, despite sexual affairs and his own eventual marriage, stayed connected to her—mystically, personally, and of course poetically—essentially for life. They had quarrels, personal and political, some, as we shall see, leading to estrangements. But there were also sustained periods of deep intimacy, of friendship and love, albeit—with a single exception, in December 1908—non-sexual. Maud may not have fully understood him, certainly not his politics nor the more demanding of his poems, though she was always aware of her co-creative role as Muse. And though she never plumbed the depths of his suffering on her account, she was often kind and considerate. Aside from the brief period, in 1908/9, when he was ‘beloved,’ she addressed her letters to him for decades as ‘my dear Willie,’ and she meant it. But that is part of the tragedy, what made the situation, like the minotaur, ‘monstrous.’ I am quoting the eerie but intimately revealing dream-poem, ‘Presences,’ placed, in The Wild Swans at Coole, immediately after ‘A Deep-sworn Vow,’ in which Maud’s face looms up from the subconscious. Of the three presences he imagines of women ‘laughing or timid or wild,’ one is a ‘harlot,’ the second, a ‘child,’ the third, ‘it may be, a queen.’ The one thing the trinity (perhaps Mabel Dickinson, certainly Iseult Gonne, and Maud herself) have in common was that ‘they had read/ All I had rhymed of that monstrous thing,/ Returned and yet unrequited love.’

But that was still in the future. When she erupted into Yeats’s life, the twenty-two-year-old Maud was a strikingly beautiful woman radiating energy yet poised, majestically tall, with a stunning hourglass-figure, a glorious head of Pre-Raphaelite bronze hair, heart-melting eyes, and a complexion delicate and translucent as the ‘apple-blossom’ Yeats associated with her from the epiphanic moment he first laid eyes on her. The poet certainly had promising Muse-material to begin with. A month before Maud descended on Yeats, Douglas Hyde—Fenian, Irish scholar and, a half-century in the future, destined to be the first president of Ireland—recorded in his diary for 16 December 1888: ‘I saw the most dazzling woman I have ever seen: Miss Gonne, who drew every male in the room around her […]. My head was spinning with her beauty.’6 Among many others, another Irish president (of the post-Treaty Free State), Arthur Griffith, was equally bedazzled. George Bernard Shaw was another notable struck by the statuesque Maud. Though he had fallen in love with another of Yeats’s Muse-figures, the actress and occultist Florence Farr, Shaw, a man of the world not given to hyperbole, pronounced Maud Gonne ‘the most beautiful woman in the British Isles.’ For Yeats, her smitten bard, Maud, a study in Contraries, was sweet and childlike, yet also a Virgilian goddess redivivus and a Helen of Troy born out of phase, and thus destined to be a destroyer: ‘terrible beauty’ personified.

Even, then, of course, she was an activist prone to violence. Describing their momentous first meeting back in January 1889, Yeats, though blinded with love at first sight, also recorded, not only that ‘she vexed my father with talk of war,’ but—and here Maud was reflecting, along with physical-force Irish nationalism, the kind of apocalyptic excitement that was in the air—‘war for its own sake, not as the creator of certain values but as if there were some virtue in excitement itself.’7 When Yeats took Maud’s side against his father, it ‘vexed him the more, though he might have understood that a man young as I could not have differed from a woman so beautiful and young’ (Mem, 40). If, he remarked, she held that ‘the world was flat or the moon an old caubeen I would be proud to be of her party.’ Her excitement in turn excited Yeats, who was both fascinated and, later, disturbed by her commitment to the cult of blood sacrifice, and appalled by what he saw as the self-destructive virulence of her hatred of the British Empire.

It didn’t take long for Yeats to realize that his own love was self-destructive. In explaining to himself why, in 1896, he returned to Maud, throwing away his first sexual relationship (with Olivia Shakespear, disguised as ‘Diana Vernon’), Yeats cited a passage from the notebooks of Leonardo: ‘All our lives long, as da Vinci says, we long, thinking it is but the moon we long [for], for our destruction, and how, when we meet [it] in the shape of a most fair woman, can we do less than leave all others for her. Do we not seek our dissolution upon her lips?’8

§

Given her fame as a great poet’s Muse, it is easy for enthralled readers of the poetry to forget, or simply never care to know (and there’s a case to be made for both perspectives) that Maud Gonne was a woman of considerable if obsessive achievement in her own right: an impressive if eccentric woman not only of remarkable beauty but of great physical courage, and indefatigable commitment to the Irish cause. The label, ‘Ireland’s Joan of Arc,’ first proposed by her secret French lover, was put in print in late 1897 by the New York Herald during her tour of the United States to raise money for a Wolfe Tone memorial. Since it is an aspect of her heroic myth, most readers of the poetry know, or else should know, that Maud Gonne was an Anglo-Irish English-born revolutionary nationalist, more Irish than the Irish, committed, by any means necessary—violence very much included—to the cause of Irish independence. Quite aside from her role in Yeats’s poetry, Maud Gonne had her own life, though even the most personal aspects of that life were mingled with the political and the excessive, the ‘overflowing abundance’ (Mem, 41) and self-destructive ‘wildness’ Yeats had seen in her from the outset. ‘But even at the starting-post, all sleek-and new,’ he claims in ‘A Bronze Head’ (1938), ‘I saw the wildness in her and I thought / A vision of terror that it must live through/ Had shattered her soul.’

At the time of their first meeting, Maud’s instant worshiper had no idea that across the Channel she was in the midst of a clandestine sexual relationship with the French Boulangist Lucien Millevoye, the father-to-be of Maud’s daughter, Iseult. An embodiment of Maud’s spiritual and political credo, ‘life out of death, life out of death, always,’ Iseult was conceived in the tomb of an earlier child by Millevoye, Georges, who had died of meningitis in 1892, at just nineteen months old.9 Inconsolable and obsessed by the thought of reincarnation, Maud, encouraged by Yeats’s friend George Russell (AE) to believe the myth that a dead child might be reborn within a family, persuaded Millevoye to have intercourse with her in Georges’ tomb, a vault under the memorial chapel in the Samois graveyard.

Yeats, who had heard stories of a French lover, stories he naively ‘disbelieved,’ and thought ‘twisted awry by scandal,’ was finally trusted by Maud with at least most of the truth. Writing in 1915/16, in an account unpublished until 1972 (Mem, 132–33), Yeats recorded the story told him by Maud ‘bit by bit.’ It was a story too bizarre not to be believed, though she had been lying to him for years, even as he defended her, at least once at her request, against those who maligned her as either a French or a British spy, or as ‘a vile abandoned woman who has had more than one illegitimate child.’ The latter accusation was made by Charles MacCarthy Teeling, a violent man already despised by Yeats for having thrown a chair at the venerable John O’Leary, causing Teeling to be ousted from London’s Young Ireland Society, of which Yeats was president.10 As for the occult experiment in the graveyard vault: it worked. Iseult, passed off by Maud as her niece or as a ‘child I adopted,’ was born on 6 August 1894. All of this—the liaison with Millevoye and the sex among the tombstones—was a secret unknown to Yeats, until Maud, trusting him with the key to ‘the labyrinth of her days,’ finally confided in him. That was in 1897, a full eight years after they had first met; and yet, a year later, Yeats was still willing to champion Maud in poetry as well as prose, most notably in the poem ‘He Thinks of Those Who Have Spoken Evil of His Beloved.’ His song, made ‘out of a mouthful of air,’ would, he assured her, outweigh their slander:

Half close your eyelids, loosen your hair,

And dream about the great and their pride;

They have spoken against you everywhere,

But weigh this song with the great and their pride;

I made it out of a mouthful of air,

Their children’s children shall say they have lied.

No matter that, at least when it came to such vicious but accurate charges as those of Teeling, it was Yeats who was fabricating. Nevertheless, through the power of his poetry he will, he assures his beloved, turn the tables on her enemies, persuading their posterity to believe them the liars.

But then, as public as the earlier liaison was private, there was her later troubled marriage to MacBride, another ‘physical-force’ political revolutionary: a marriage a devastated Yeats had tried, as we’ve just seen, to prevent. The penchant for violence in MacBride, that ‘drunken, vainglorious lout,’ was exercised domestically as well as politically, as Yeats discovered in later working to extricate Maud from that short-lived but disastrous marriage. In 1905, he confided to Lady Gregory that MacBride’s drunken violence and sexual abuse extended (‘the blackest thing you can imagine’) to ten-year-old Iseult. Ironically, it was her wish to give Iseult a conventional home that had motivated Maud to marry; now her husband’s molestation of that child led her to seek a legal separation.

She had from the outset been more tolerant of MacBride’s penchant for political violence. Planning their honeymoon in Gibraltar in 1903, MacBride conceived of a plot to assassinate King Edward VII, a plot that fizzled out because of his drinking. But Maud, as she tells us in one of the more revealing moments in her unrevealing autobiography, acquiesced in the plan.11 Their union did, however, produce a son, Séan, at first an IRA revolutionary, but later President of the International Peace Bureau, co-founder of Amnesty International, and, in 1974, fulfilling his mother’s most commendable advocacy, recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for ‘his efforts to secure and develop human rights throughout the world.’

Fig. 2 Maud Gonne, three-quarter length oval portrait wearing Celtic brooch, by J. E. Purdy, January 1900, during Maud’s second American tour. Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maud_Gonne,_as_photographed_by_J.E._Purdy_circa_1890_to_1910.jpg.

By the time long-pining Yeats was himself finally admitted into Maud’s bed, briefly and inconsequentially except in terms of poetry, twenty years had passed since their first meeting in 1889. By the time they finally physically consummated their strange union, in Paris, in December 1908, Maud had mothered three children, two of whom survived; converted to Catholicism; was in the midst of a legal separation from MacBride (though divorce was refused or postponed by the court); and was, at 42, still attractive but no longer the stunner that had once taken men’s breath away. She had told Yeats as early as 1898 that she had a ‘horror of physical love.’ At the time, given her circumstances, it may have been a ploy to keep their relationship non-sexual. But the confession also seems accurate, despite her history. She reiterated her dread of physical intimacy following their one night in Paris, informing Yeats, in what amounted to a loving but firm morning-after note (G-YL, 258), that she had triumphed over her physical desire for him, was now ‘praying’ that he could overcome his for her (easier said than done), and wished to return to their intimate but sexless ‘mystical marriage,’ which they had recently renewed, in Paris in June 1908. Now, to Yeats’s immediate grief, though it triggered a mature reassessment on his part, Maud quickly reverted to the old arrangement—an amitié amoureuse.

Yeats adhered to Maud’s decree, though he did make one last try, a final marriage proposal in 1917, after MacBride had been executed by the British as one of the Easter Rising leaders. It should be mentioned that Maud seemed willing to forgive all in that tragic but redemptive light. Speaking of those who were ‘executed in cold blood,’ her ‘husband among’ them, she noted, in a letter of 16 August 1916, to John Quinn (who knew all about Maud’s earlier domestic situation, Yeats having consulted him as attorney): ‘He has died for Ireland and his son will bear an honoured name. I remember nothing else,’ his ‘fine heroic end’ having ‘atoned for all.’ After citing the account of the Franciscan friar who was with MacBride during his final hours, she concluded, ‘he is with his comrades and England is powerless to dishonor their memories.’12

That was left to Yeats. Though, in ‘Easter 1916,’ he included MacBride by name among the honored dead, he did not refrain from violating elegiac decorum by labeling him ‘a drunken, vainglorious lout’ who ‘had done most bitter wrong/ To some who are near my heart.’

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly;

A terrible beauty is born.

Just as in his poems to and about Maud Gonne, Yeats here transcends political reservations and personal bitterness to celebrate a role played in a larger, heroic drama. His transformative love for his own ‘terrible beauty,’ which changed Yeats utterly, was also celebrated in ‘song.’ Much of the history I have just synopsized does not seem the biographical material out of which great love poetry is to be made. But it was; and it is primarily Maud Gonne’s role as Yeats’s Muse that concerns me here. Since, as the poet declares (in Part III of ‘The Tower’), ‘only an aching heart/ Conceives a changeless work of art,’ Maud may be said—to adapt Auden’s phrase, ‘Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry’—to have ‘hurt’ Yeats into great love poetry. She was fully aware of her status as a Muse-figure, and, as an active agent in the collaboration, is not to be thought of as a mere projection, a passive recipient of male adoration—an understandable feminist charge regarding Muses, but in Maud’s case somewhat off the mark. That Maud, a political activist and lifelong advocate of human rights, was more than a great poet’s Muse, is clear from the biographies by Nancy Cardozo (1978), Margaret Ward (1990), and Trish Ferguson (2019). Maud Gonne’s complexity is suggested by the titles of the two other recent biographies: Adrian Frazier’s good if gossipy The Adulterous Muse (2016) and the latest, with the title lifted from the Yeats poem, Kim Bendheim’s engaging though overly personal The Fascination of What’s Difficult (2021).

But Maud’s complexity extends to her function as Muse, assuming a masculine role, as Yeats had assumed a female role, in his elegy for the Easter 1916 martyrs. In that remarkable letter written to Yeats on 15 September 1911, Maud strangely anticipates Yeats’s taking on, along with the role of national elegist and eulogist, of a specifically maternal role in the final stanza of ‘Easter 1916.’ Answering his own question as to when Ireland’s long ‘sacrifice’ may finally ‘suffice,’ he responds as choral commemorator of what Michael Collins called ‘a Greek tragedy’: ‘That is Heaven’s part, our part/ To murmur name upon name/ As a mother names her child.’ In that 1911 letter, Maud assumed the role of domina, but, like her devotee, reversing genders. ‘Our children were your poems,’ she informs Yeats, ‘of which I was the Father sowing the unrest & storm which made them possible & you the mother who brought them forth in suffering & in the highest beauty & our children had wings—’ (G-YL, 302).13

1 Longenbach’s comment linking Petrarch and Yeats appears as the first of three notes of praise prefacing David Young’s 2004 translation of The Poetry of Petrarch. I cite the poet from this text.

2 Aside from Shakespeare’s, the other great Elizabethan sonnet-sequence, the Amoretti by Edmund Spenser, departs from the tradition since Spenser is courting and celebrating the woman, Elizabeth Boyle, soon to become his wife, their marriage immortalized in the rapturous ‘Epithalamion.’

3 Foster, The Apprentice Mage, 87.

4 Mem, 40. Though Maud thought they had first met in 1887, at John O’Leary’s house, Yeats, as the more thunderstruck, is likelier to be right about the place and date: Bedford Park on 30 January 1889.

5 An undated fragment of a letter, quoted by Ward, Maud Gonne, 57.

6 Dominic Daly, The Young Douglas Hyde, 95. Maud subsequently took Irish lessons from Hyde.

7 Addressing Florence Farr (under her Golden Dawn initials, S.S.D.D.), in December 1895, Yeats wondered if the Venezuelan border dispute of that year might initiate ‘the magical armageddon’ (L, 259–60). Maud, writing to Yeats from Samois on 27 September 1898 (G-YL, 95), told him, ‘I believe more than ever in some terrible upheaval in Europe in the near future.’ She reports the ‘most extraordinary sight I ever witnessed’: lights flashing across the night sky, one a seeming ‘spear of light.’ She was witnessing the aurora borealis, but Maud welcomed the flashing lights as portents of violence: ‘It was so wonderful I felt a sort of awe I am sure it presaged terrible events.’

8 Yeats, (Mem, 88). In the passage Yeats paraphrases (turned a quarter-century later into a poem, ‘The Wheel’), da Vinci describes a ‘return to primal chaos, like that of the moth to the light.’ The ‘man with perpetual longing’ for (for instance) too-slow seasonal change is actually ‘longing for his own destruction.’ Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, 1:80–81.

9 The same archetypal belief was intoned by Padraic Pearse over the grave of O’Donovan Rossa in 1915 and put to the test a year later at, inevitably, Easter, feast of the Resurrection.

10 Yeats also spoke out publicly against Frank Hugh O’Donnell, the Irish nationalist who had accused Maud of being a French spy. See Bendheim, 98.

11 For Maud’s account of the abortive plot, see A Servant of the Queen, 282–85.

12 John Quinn Papers, Berg Collection, NYC Library; cited in Cardozo, 309, n444–45.

13 Maud added that Yeats and Lady Gregory also had a ‘child,’ in the form of the Abbey Theatre Company. She was ‘the Father who holds you to your duty of motherhood,’ with a child that ‘requires much feeding & looking after.’ There is a parallel in Yeats’s later personal and poetic relationship with Lady Dorothy Wellesley, who was lesbian. Yeats admired in her poetry ‘its masculine element amid so much feminine charm,’ a mixture reminiscent of Maud Gonne. His own creativity, he’d told her earlier, arose out of ‘the woman in me,’ artistically demonstrated in his ‘Woman Young and Old’ and ‘Crazy Jane’ poems. Yeats saw his collaboration with Wellesley on a sequence of explicit ballads on a sexual triangle, as a marriage of her masculine rhythms with his feminine Muse (L, 875).