Chapter Seven

© 2022 William F. Halloran, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0276.07

When the Sharps reached Rome in early December of 1890, they settled in for the winter. Elizabeth recalled those months as “one long delight” for her husband; they “amply fulfilled even his optimistic anticipation. He reveled in the sunshine and the beauty; he was in perfect health; his imagination was quickened and worked with great activity” (Memoir, 173). In mid-December Edith Wingate Rinder came from London to spend three weeks with Mona Caird who was wintering in Rome “for her health.” A beautiful and intelligent young woman of twenty-six, Edith had married Mona’s first cousin, Frank Rinder, less than a year earlier, on February 17, 1890. Edith and Frank were childhood sweethearts who had grown up as landed gentry on neighboring farms in the north of England. Educated at home and locally, Edith spent a year studying in Germany and worked for a time as a governess in Lincolnshire after returning home. Frank was also educated in Lincolnshire before his parents sent him to Fettes College, an established boarding school in Edinburgh. During his first year — 1883–1884 — he became ill with cerebral meningitis which left him somewhat crippled for the rest of his life. Back in Lincolnshire, Edith and Frank felt isolated. Deprived of culture, without prospects, and unable to overcome their parents’ opposition to their marrying, they set their sights on London and Frank’s first cousin Mona Caird.

Alice Mona Alison was the daughter of John Alison of Midlothian, Scotland, who invented the vertical boiler. As a girl she lived with her family in a substantial house on Bayswater Road in London, close to Elizabeth Sharp’s family home in Inverness Terrace, and the two girls became life-long friends. In 1887 Mona married James Alexander Henryson-Caird (1847–1921) of Cassenary, Creeton, Kirkendbrighten. A member of Parliament and a determined agrarian, he spent most of his time on his farm in Scotland and his country house in Micheldever, a village in Hampshire. His wife, on the other hand, spent most of her time in their large South Hampstead house where she entertained many of the day’s luminaries. An early advocate of freedom from the stultifying restraints of high Victorianism, Mona, in 1888 invited her cousin Frank Rinder and Edith Wingate to London and welcomed them into her household. Two years later, against the wishes of their parents, she facilitated their marriage, which took place not at a church, as was customary, but at a London Registry Office.

Wescam, the Sharp’s South Hampton house, was only a few blocks from the Caird’s house, and there was frequent entertaining back and forth. The Sharps were well-acquainted with the Rinders, but we do not know if William and Edith were attracted to each other before Edith arrived in Rome. By December 1890, Edith and Frank had been living with each other for at least three years, and the glow had worn off their relationship. Sharp’s relationship with Elizabeth, which also began as a youthful friendship, had devolved into that of a mother overseeing her frequently ill child whom she called “my poet.” In any case, the friendship between the handsome William Sharp, free of pressing obligations and revitalized at the age of thirty-five, and the strikingly beautiful Edith Rinder, who was twenty-six, blossomed under the warm Italian sun. Edith would become the mysterious unnamed friend Sharp frequently alluded to in letters and conversations and the principal catalyst for the Fiona Macleod phase of his literary career. In an 1896 letter to his wife, Sharp said he owed to Edith his “development as ‘Fiona Macleod’ though, in a sense of course, that began long before I knew her, and indeed while I was still a child.” “Without her,” Sharp continued, “there would have been no ‘Fiona Macleod’.” After quoting from this letter (Memoir, 222), Elizabeth continued, with remarkable generosity,

Because of her beauty, her strong sense of life and the joy of life; because of her keen intuitions and mental alertness, her personality stood for him as a symbol of the heroic women of Greek and Celtic days, a symbol that, as he expressed it, unlocked new doors in his mind and put him “in touch with ancestral memories” of his race.

When the first Fiona Macleod book, Pharais: A Romance of the Isles, was published in 1894, it was dedicated to “E. W. R.” — Edith Wingate Rinder.

Sharp and Edith took long walks together in the Roman Campagna in late December and early January. The beauty of the countryside and the joy of his newfound love moved Sharp to compose in February a sequence of exuberant poems that were privately printed in March 1891 as Sospiri di Roma which translates as sighs or whispers of Rome. Of that volume and Edith Rinder’s role in its genesis, Elizabeth wrote

The “Sospiri di Roma” was the turning point. Those unrhymed poems of irregular meter are filled not only with the passionate delight in life, with the sheer joy of existence, but also with the ecstatic worship of beauty that possessed him during those spring months we spent in Rome when he had cut himself adrift for the time from the usual routine of our life, and touched a high point of health and exuberant spirits. There, at last, he found the desired incentive towards a true expression of himself, in the stimulus and sympathetic understanding of the friend to whom he dedicated the first of the books published under his pseudonym. This friendship began in Rome and lasted throughout the remainder of his life (Memoir, 222).

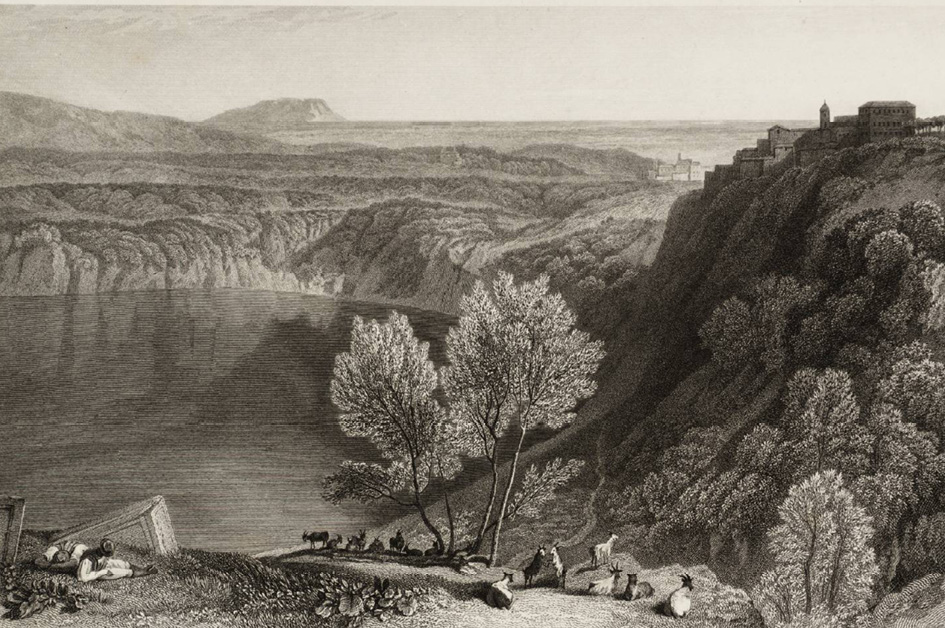

Elizabeth included in the Memoir excerpts from Sharp’s diary that detail his activities and his writing during January and February. On January 3, he and Edith traveled by train to the village of Albano south of Rome and walked from there to Genzano where they looked down into Lake Nemi, which was “lovely in its grey-blue stillness, with all the sunlit but yet somber winterliness around. Nemi, itself, lay apparently silent and lifeless, ‘a city of dream,’ on a height across the lake.” He continued, “One could imagine that Nemi and Genzano had once been the same town, and had been riven asunder by a volcano. The lake-filled crater now divides these two little hill-set towns.”

This excursion stands out among others Sharp described because he used it to define his relationship with Edith Rinder and his creation of Fiona Macleod. On February 8, after Edith had returned to London, he wrote a poem about the experience:

The purple blueness,

The swimmer goeth.

Ivory-white, or wan white as roses

Yellowed and tanned by the suns of the Orient,

His strong limbs sever the violet hollows;

A shimmer of white fantastic motions

Wavering deep through the lake as he swimmeth.

Like gorse in the sunlight the gold of his yellow hair,

Yellow with sunshine and bright as with dew-drops,

Spray of the waters flung back as he tosseth

His head i’ the sunlight in the midst of his laughter;

Red o’er his body, blossom-white ‘mid the blueness,

And trailing behind him in glory of scarlet,

A branch of red-berried ash of the mountains.

Drifting athwart

The purple twilight,

The swimmer goeth —

Joyously laughing,

With o’er his shoulders,

Agleam in the sunshine

The trailing branch

With the scarlet berries.

Green are the leaves, and scarlet the berries,

White are the limbs of the swimmer beyond them

Blue the deep heart in the haze of September,

The high Alban hills in their silence and beauty,

Purple the depths of the windless heaven

Curv’d like a flower o’er the waters of Nemi.

In his diary, Sharp followed the poem’s title with “(Red and White) 42 lines” though it was shortened to thirty-one lines when it appeared in Sospiri di Roma. The free verse of this poem and others in the volume is a deliberate departure from the rigid formalism of “Victorian” poetry. Rather than describing a place in detail, the poems use color and partial glances to create an impression of a place. From Rossetti and other Pre-Raphaelites, Sharp inherited an interest in the relationship between painting and poetry. In Rome, he created with words what the French impressionists were creating in painting. That effort reemerged in the poetry he wrote as Fiona Macleod, especially in the prose poems, or what Sharp preferred to call “prose rhythms,” in “The Silence of Amor” section of From the Hills of Dream (1896) which Thomas Mosher published separately, with a “Foreword” in 1902.

More can be said about the Nemi poem. Sharp may have seen paintings of the lake by John Robert Cozens (1777) and George Inness (1857); he surely knew J. M. W. Turner’s many depictions of the lake and its surroundings. He must also have known the lake was associated with the Roman Goddess Diana Nemorensis (“Diana of the Wood”) who was the goddess of wild animals and the hunt. She derived from the Greek goddess Artemis who was also goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, and wild animals. The sister of Apollo, Artemis was also a goddess of the moon and fertility. Sharp must also have been aware of the myth central to James Fraser’s ground-breaking Golden Bough, which appeared in 1890. Therein the King of the Woods — Rex Nemorensis — guards the temple of Diana Nemorensis, Diana of the Wood, with a golden bough that symbolizes his power. Annually, reflecting the progress of the seasons and the harvest, a man plucks a bough from the golden tree, swims Lake Nemi, kills the King, assumes his powers, and guards Diana’s temple. In his poem, Sharp idealizes himself as the handsome and powerful swimmer who carries the red-berried ash bough, a symbol of dynamic life, to lay at the feet of Diana’s reincarnation as the beautiful Edith Rinder.

Fig. 11 John Robert Cozens, Lake Nemi (1777). © Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/cozens-lake-nemi-t00982, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Fig. 12 Joseph Mallord William Turner, Lake Nemi (c. 1827–1828). Turner visited Lake Nemi in 1819 and painted this sketch from memory in Rome in 1828. © Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-lake-nemi-n03027, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Fig. 13 Lake Nemi, Engraved by Middiman and Pye in 1819 after a sketch by Joseph Mallord William Turner. Transferred from the British Museum to Tate Britain in 1988, CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported), https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-lake-of-nemi-engraved-by-middiman-and-pye-t06023

Sharp’s fascination with Lake Nemi, its renewal myth, and the day — January 3, 1891 — he visited Nemi with Edith Rinder did not end with the poem. Years later he cast the day in a different guise, but with the same significance. He transformed the poem’s handsome male swimmer into a beautiful woman. Ernest Rhys, in his Everyman Remembers, recalled Sharp telling him that

His first meeting with Fiona was on the banks of Lake Nemi when she was enjoying a sun-bath in what she deemed was virgin solitude, after swimming the lake. “That moment began,” he declared, “my spiritual regeneration. I was a New Man, a mystic, where before I had been only a mechanic-in-art. Carried away by my passion, my pen wrote as if dipped in fire, and when I sat down to write prose, a spirit-hand would seize the pen and guide it into inspired verse. We found we had many common friends: we traveled on thro’ Italy and went to Rome, and there I wrote my haunting Sospiri di Roma.”

Rhys took Sharp’s words to mean there was “an objective Fiona Macleod,” and “the passion she inspired gave Sharp a new deliverance, a new impetus.” Though Rhys did not know who she was, he was correct. A real woman figured crucially in Sharp’s creation of Fiona Macleod. The male swimmer in Sharp’s Nemi poem, “Ivory-white, or wan white as roses | Yellowed and tanned by the suns of the Orient,” was initially an idealized self-portrait. Years later, he had become Fiona “enjoying a sun-bath in what she deemed was virgin solitude, after swimming the lake.” The lengthy diary account of his first day-long walk with Edith Rinder and the importance he placed on their visit to Nemi suggest that may have been the day their relationship deepened. It was she, not the imaginary Fiona, who was responsible for his “spiritual regeneration,” for his becoming a “New Man, a mystic,” where before he “had been only a mechanic-in-art.” She was responsible for the burst of creativity that produced the poems of Sospiri di Roma and later for the emergence of Fiona Macleod

On February 8, Sharp wrote “A Winter Evening” which describes his walk through a heavy snowstorm on January 17. His diary entry for the 17th begins “Winter with a vengeance. Rome might be St. Petersburg.” In the late afternoon, he had gone alone for a walk on the Pincio Terrace in the whirling snow.

Returning by the Pincian Gate, about 5:45 there was a strange sight. Perfectly still in the sombre Via di Mura, with high walls to the right, but the upper pines and cypresses swaying in a sudden rush of wind: to the left a drifting snow-storm: to the right wintry moonshine: vivid sweeping pulsations of lightening from the Compagna, and long low muttering growls of thunder. (The red light from a window in the wall) (Memoir, 176–177).

When he formed this experience into a poem on February 8, the same day he wrote “The Swimmer of Nemi,” he focused on that red light:

A Winter Evening

(An hour after Nightfall, on Saturday, January 17, 1891)

[To E. W. R.],

Here all the snow-drift lies thick and untrodden,

Cold, white, and desolate save where the red light

Gleams from a window in yonder high turret

And the poem ends:

Here in the dim, gloomy Via dell’Mura,

Nought but the peace of the snow-drift unruffled,

Whitely obscure, save where from the window

High in the walls of the Medici Gardens

Glows a red shining, fierily bloodred.

What lies in the heart of thee, Night, thus so ominous?

What is they secret, strange joy or strange sorrow?

Why he chose this poem to dedicate to Edith we cannot know, but it is tempting to speculate. Walking home, he observed the contrast between the sweeping winds above and the relative peace below as the lightning and thunder approached the city, the rush of wind and snow on one side and wintry moonshine on the other. He was walking alone, and the dedication to Edith suggests the poem was meant to describe the experience for her. If so, he may intended the red light high in the dark wall to represent Edith — a steady, though now remote, beacon of warmth and contentment for the poet who, Edith having returned to London, was alone and buffeted between periods of moonlit joy and stormy depression.

In mid-January, the Sharps became more active in the literary and artistic life of Rome, attending lectures and visiting art studios. Sharp’s diary shows he was sampling a remarkable array of writers: Élie Reclus, Pierre Loti, George Meredith, Robert Browning, Charles Swinburne, Coventry Patmore, Antonio Fogazzaro, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Henrik Ibsen, Edgar Allan Poe, Honoré de Balzac , and Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve. He wrote articles for the New York Independent and the British National Review and a poem for Belford’s Magazine. He met Elihu Vedder who wanted to know what the British press had written about his illustrations for Omar Khayam. On January 10, Sharp thanked Bliss Carman, literary editor of the New York Independent, for sending the issue of December 25 that printed his poem, “Paris Nocturne,” an unrhymed impressionistic poem that anticipated those he was writing in Italy.

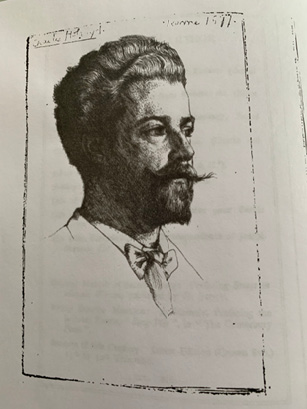

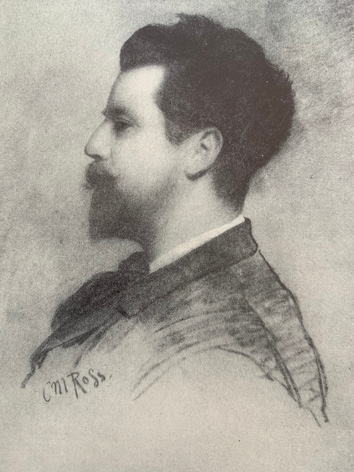

On January 30, Sharp turned in earnest to the poems that would become Sospiri di Roma. By February 2, he had written fourteen and remarked in his diary, “Such bursts of uncontrollable poetic impulse as came to me today, and the last three days, only come rarely in each year.” The next day, February 3, he sent several poems to Bliss Carman and asked him to consider publishing them or send them to other American editors for consideration. If accepted they should appear before the volume of poems he planned to publish in March. On February 10 and 11, Sharp sat for a drawing by Charles Holroyd that became the etched portrait Sharp used to face the title page of Sospiri di Roma. In late February, Charles Ross, a Norwegian painter, asked Sharp to sit for him and produced a pastel portrait that Elizabeth reproduced in the Memoir (180). The many surviving portraits of Sharp suggest painters and photographers considered him a handsome and imposing figure.

Fig. 14 Sir Charles Holroyd’s etching of William Sharp, which Sharp reproduced for insertion opposite the title page of Sospiri di Roma, the book of poems he wrote in Rome in January/February 1891 and published privately in Tivoli in March 1891, https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Sospiri_di_Roma/jT9DAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

Fig. 15 A pastel painting of William Sharp by the Norwegian painter Charles M. Ross. Sharp sat for this portrait in Rome in early March 1891. This is a photograph of the copy Elizabeth Sharp reproduced in her Memoir, taken by William Halloran (2021).

Sharp arranged to have the poems printed by the Societa Laziale’s press in Tivoli and continued writing and revising until mid-March when Elizabeth left for Florence to spend more time with her aunt. Sharp went to Tivoli for a few days to put the poems in final shape and oversee their type setting. Julian Corbett, a prominent British naval historian who had just published a biography of Sir Francis Drake, accompanied him, and the two men spent mornings working and afternoons exploring Tivoli and the surrounding hills. During a visit to the castle of San Poli dei Cavalieri, they met a “comely woman” who gave them some wine. She also told a tale that found its way, along with the town and surrounding scenery, into Sharp’s “The Rape of the Sabines,” a convoluted story that appeared the following year in the first and only issue of Sharp’s Pagan Review.

Towards the end of the month Sharp joined Elizabeth in Pisa, and from there they went to Arles in the south of France. On March 30, Sharp sent Catherine Janvier a letter from Provence in which he told her his Sospiri di Roma was being printed that very day

to the sound of the Cascades of the Anio at Tivoli, in the Sabines — one of which turns the machinery of the Socièta Laziale’s printing-works. I do hope the book will appeal to you, as there is so much of myself in it. No doubt it will be too frankly impressionistic to suit some people, and its unconventionality in form as well as in matter will be a cause of offense here and there. You shall have one of the earliest copies (Memoir, 182–183).

About seventy-five copies were printed and sent to Sharp who sent them to his friends and to newspapers and periodicals where they were most likely to be well received. He told Catherine Janvier that Marseilles was unattractive compared to Rome. He and Elizabeth preferred Arles, but it paled in comparison to the hill towns of the Apennine and the Sabines:

When I think of happy days at the Lake of Nemi, high up in the Albans, of Albano, and L’Ariccia, and Castel Gandolfo — of Tivoli, and the lonely Montecelli, and S. Polo dei Cavalieri, and Castel Madamo and Anticoli Corrado, etc., among the Sabines — of the ever new, mysterious, fascinating Campagna, from the Maremma on the North to the Pontine Marches, my heart is full of longing.… You will find something of my passion for it, and of that still deeper longing and passion for the Beautiful, in my “Sospiri di Roma,” which ought to reach you before the end of April, or at any rate early in May.

Sharp was in Scotland on May 1 when he wrote again to Catherine Janvier, this time about the critical response to Sospiri di Roma:

It is no good to any one or to me to say that I am a Pagan — that I am “an artist beyond doubt, but one without heed to the cravings of the human heart: a worshipper of the Beautiful, but, without religion, without an ethical message, with nothing but a vain cry for the return, or it may be the advent, of an impossible ideal.” Equally absurd to complain that in these “impressions” I give no direct “blood and bones” for the mind to gnaw at and worry over. Cannot they see that all I attempt to do is to fashion anew something of the lovely vision I have seen, and that I would as soon commit forgery (as I told someone recently) as add an unnecessary line, or “play” to this or that taste, this or that critical opinion. The chief paper here in Scotland shakes its head over “the nude sensuousness of ‘The Swimmer of Nemi’, ‘The Naked Rider’, ‘The Bather’, ‘Foir di Memoria’, ‘The Wild Mare’ (whose ‘fiery and almost savage realism!’ it depreciates — tho’ this is the poem which [George] Meredith says is ‘bound to live’) and evidently thinks artists and poets who see beautiful things and try to fashion them anew beautifully, should be stamped out, or at any rate left severely alone (Memoir, 185–186).

Sharp objected to being called a “Pagan” if it connoted only unrestrained sensuality and the absence of ethical messages and religious beliefs, but the more he thought about the term, the more he warmed to it. The unclothed statues he saw in and about Rome were certainly pre-Christian and therefore Pagan. His descriptions of them in the Sospiri poems reflect his renewed energy, sexual and artistic, his reawakened appreciation of the beauty of the naked human form, and his incorporation of sensuality into a wholistic view of human life. Those were the very qualities that bothered the unnamed reviewer in Scotland’s chief paper, the Edinburgh Scotsman (April 20, 1891, 3). Soon, as if to flaunt the reviewer, he would appropriate the term and write under various pseudonyms the essays, stories, and poems in his Pagan Review.

It is no wonder the conservative papers and journals that received copies of the book were put off by its “nude sensuousness.” The male swimmer in the Nemi poem is one of several white nudes — men and women and even a white mare pursued and mounted by a dark stallion — that populate the volume. Shortly after his previous volume of poems — Romantic Ballads and Poems of Phantasy — appeared in 1888, Sharp wrote to a “friend:”

I am tortured by the passionate desire to create beauty, to sing something of the “impossible songs” I have heard, to utter something of the rhythm of life that has touched me. The next volume of romantic poems will be daringly of the moment, vital with the life and passion of today.

Three years later he fulfilled that promise in a month-long burst of creativity in Rome. He saw himself as part of a wider effort to break through the constraints of late Victorianism, but the assault on poetic forms and sexual norms that resulted from his “passionate desire to create beauty” in Sospiri di Roma met resistance or avoidance among all but a few close friends who shared his goals. George Meredith was one of those friends. In a letter to Sharp, he praised the volume with some reservations: “Impressionistic work where the heart is hot surpasses all but highest verse.… It can be of that heat only at intervals. In ‘The Wild Mare’ you have hit the mark.” That was the poem the reviewer in the Scotsman criticized for its “fiery and almost savage realism.”

The Sharps stayed in Provence until the end of April. In early May Sharp went to London and intended to go back to France where they would spend the summer in the forest of Fontainebleau. While he was away, Elizabeth became ill with an “insidious form of low fever” and returned to England for treatment. Along with medication, she needed rest so they went to Eastbourne on the Sussex coast for two weeks where she could have the fresh sea air, and he could work undisturbed on the Severn book. After several weeks Sharp went to see his mother in Edinburgh while Elizabeth, restored to health, stayed with her mother in London. In mid-July they met in York and went to Whitby on the Yorkshire coast for six weeks. On August 21, back in London, Sharp asked the editor of Blackwood’s Magazine if he might be interested in publishing a story curiously entitled “The Second Shadow: Being the Narrative of Jose Maria Santos y Bazan, Spanish Physician in Rome.” Blackwood’s declined, but Bliss Carman published it on August 25, 1892 in the New York Independent. From May until mid-August, Sharp spent most of his working hours on his biography of Joseph Severn. Having finished the last revisions on August 28, he and Elizabeth left for Stuttgart where Sharp and Blanche Willis Howard would execute their collaboration.

For a title, the two writers adapted a line from Shakespeare’s Othello — “A fellowe almost damned in a faire wife.” The main characters of A Fellowe and His Wife would be a German Count and his beautiful young Countess who goes to Rome to become a sculptor. Sharp drew upon his experience in Rome to write the letters of the “faire wife” while Howard drew upon hers in the German court to write the Count’s replies. In Rome, the wife falls under the spell of a famous sculptor who seduces and then betrays her. Though it takes a great deal of heightened prose, especially on the wife’s part, the husband finally goes to Rome, confronts the sculptor, forgives his wife, and takes her back to Germany. Sharp’s decision to play the part of the Countess was logical enough given his recent immersion in Rome. His easy adoption of the role and his obvious pleasure in molding the female character through her writing foreshadowed his decision to adopt a female authorial voice and pseudonym for his first Fiona Macleod romance in 1894. Published in both America and Britain in 1892, A Fellowe and His Wife contained a good deal of Sharp’s enchantment with the beauty and culture of Rome and Howard’s with the German aristocracy she recently joined.

.jpg)

Fig. 16 Blanche Willis Howard, in F. E. Willard, A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life (Buffalo, N. Y.: Moulton, 1893), 735. Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BLANCHE_WILLIS_HOWARD_VON_TEUFFEL._A_woman_of_the_century_(page_745_crop).jpg, Public Domain.

Sharp was energized by the warm fall weather in southern Germany and by his relationship with Howard, who enjoyed being called the Frau Hof-Arzt von Teuffel. In a letter to Catherine Janvier on September 3, he said he was “electrified in mind and body:”

The sun flood intoxicated me. But the beauty of the world is always bracing — all beauty is. I seemed to inhale it — to drink it in — to absorb it at every pore — to become it — to become the heart and soul within it. And then in the midst of it all came my old savage longing for a vagrant life: for freedom from the bondage we have involved ourselves in. I suppose I was a gypsy once — and before that ‘a wild man o’ the woods.

He also wrote excitedly to Bliss Carman on September 3:

How strangely one drifts about in this world. Not many days ago I was on the Yorkshire moors or along the seacoast by Whitby: a few days ago I was in Holland, and rejoicing in the animated life of that pleasant ‘water-land’: last Sunday I was strolling by the Rhine or listening to the music in Cologne Cathedral. And now we are temporarily settled down in this beautiful Vine-land — in Stuttgart, the loveliest of all German capitals. It is glorious here just now. The heat is very great, but I delight in it. These deep blue skies, these vine clad hills all aglimmer with green-gold, this hot joyous life of the South enthralls me — while this glorious flooding sunshine seems to get into the heart and the brain.

He concluded the letter to Catherine Janvier on that high note:

I have had a very varied, and, to use a much-abused word, a very romantic life in its external as well as in its internal aspects. Life is so unutterably precious that I cannot but rejoice daily that I am alive: and yet I have no fear of or even regret at the thought of death. There are many things far worse than death. When it comes, it comes. But meanwhile we are alive. The Death of the power to live is the only death to be dreaded.

With the Severn biography finally behind him, Sharp experienced in Germany in September and October 1891 a joy that came powerfully, seldom. Soon after arriving in Stuttgart, he confided in his diary, “What a year this has been for me: the richest and most wonderful I have known. Were I as superstitious as Polycrates I should surely sacrifice some precious thing lest the vengeful gods should say, ‘Thou hast lived too fully: Come!’”

In his diary on September 6, Sharp called Howard a “charming woman.” He “liked her better than ever” and had to remind himself he was there to collaborate with her on a novel. Conscious of his propensity to fall in love with attractive women, he wrote, “I must be on guard against my too susceptible self.” In his late September annual birthday letter to E. C. Stedman, he wrote more expansively:

I am here for a literary purpose — though please keep this news to yourself meanwhile — i.e., collaborating with our charming friend Blanche Willis Howard (von Teuffel) in a novel. It is on perfectly fresh and striking lines, and will I think attract attention. We are more than half through with it already. She is a most interesting woman and is of that vigorous blond race of women whom Titian and the Palmas loved to paint, and whom we can see now in perfection not in Venico but at Chioggia, further down the Adriatic. But if I fall too deeply in love, it will be your fault — for it was you who introduced me to her! I told her about your birthday, and I think she is going to send you a line of greeting. We see each other for several hours daily, or nightly, and — well, literary life has its compensations! But our affectionate camaraderie is as Platonic as — say, as yours would be in a like instance: so don’t drag from its mouldy tomb that cynic smile which lies awaiting the possible resurrection of the Old Adam! Your ears must sometimes tingle as your inner sense overhears our praises of you as man and writer.

He proceeded to tell Stedman he planned to visit America in early 1892 and give a series of public lectures in Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Cincinnati, Chicago, Buffalo, Albany, & perhaps elsewhere. He listed fourteen topics ranging from the Pre-Raphaelites to “Poets and Poetry Today” and asked Stedman for advice and assistance in making the arrangements. More immediately, he and Elizabeth left Germany in mid-October and returned to England via Amsterdam on October 20.

The extreme high Sharp experienced in Germany collapsed into physical illness and a deep depression in London. Elizabeth wrote, “The brilliant summer was followed by a damp and foggy autumn. My husband’s depression increased with the varying of the year.” On November 9 he spent all day at his London club — the Grosvenor — and wrote as follows in a note to Elizabeth who was spending the day with her mother.

I have been here all day and have enjoyed the bodily rest, the inner quietude, and, latterly, a certain mental uplifting. But at first I was deep down in the blues. Anything like the appalling gloom between two and three-thirty! I could scarcely read or do anything but watch it with a kind of fascinated horror. It is going down to the grave indeed to be submerged in that hideous pall. As soon as I can make enough by fiction or the drama to depend thereon, we’ll leave this atmosphere of fog and this environment of deadening, crushing, paralysing death-in-life respectability. Circumstances make London thus for us: for me at least — for of course we carry our true atmosphere in ourselves — and places and towns are, in a general sense, mere accidents (Memoir, 192).

In a December letter to Catherine Janvier he asked, “Do you not long for the warm days — for the beautiful living pulsing South? This fierce cold and gloom is mentally benumbing.” He looked forward to seeing her in New York in three weeks and reading for her one of the pieces of “intense dramatic prose” he had written in Germany.

While dealing with his depression and proceeding with his “Dramatic Interludes,” Sharp had to return to his Severn biography. The publisher — Sampson Lowe, Marston & Company — decided to issue the work as one volume rather than two. He was forced to condense the first volume and eliminate most of the second which chronicled Severn’s life after Keats died, including the twenty years he spent as British Counsel in Rome. He fashioned an article, “Joseph Severn and His Correspondents,” to make use of some of the material he was forced to eliminate from the biography. Horace Scudder published it in the December 1891 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. In early December he wrote to Scudder:

If practicable, within the next fortnight or 3 weeks I shall send you the promised “Unpublished Incidents in the Life of Joseph Severn” (or such title as you prefer). I am glad there is a chance of these reminiscences appearing in a conspicuous place — for it appears that many people both in America and here are mainly anticipating the record of Severn’s consular life (partly, no doubt, after Ruskin’s splendid eulogium of him in Praeterita) — which is, so far as the book is concerned, regrettable.

Scudder published that article as “Severn’s Roman Journals” in the May 1892 issue of the Atlantic.

On December 8 Sharp informed Bliss Carman he had booked passage on the Teutonic which would sail from Liverpool on January 6 and arrive in New York on January 12 or 13. He had been forced to postpone all lecturing.

I am going out partly to attend to some private literary business, best seen to on the spot; partly to arrange for the bringing out in America of a play of mine which is to be produced here; and partly to get a glimpse of the many valued friends and acquaintances I have in N.Y. and Boston. I shall be in N.Y. for three weeks at any rate. Perhaps later on, say in your issue for the first week in January, you will be able to oblige me by inserting in the Independent a para to the above effect: as this would save me letting a lot of people know, and enable me to economize my limited time.

According to Elizabeth, Sharp’s doctor had “strictly prohibited” him from giving lectures in the United States. Once in New York, he used that excuse to decline a request from a Harvard faculty member to lecture there “upon a subject of contemporary literature.” His doctor may have warned Sharp to avoid stress, but the fact that no lectures were prepared followed a pattern of planning and then canceling. That pattern, I believe, was rooted in a deep insecurity about the depth of his knowledge which caused his weak heart to race uncontrollably before and during any presentation to a potentially critical audience.