11. The Manner of Our Deaths

© 2021 Philip Graham, CC BY-NC 4.0https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0278.11

From the time of her first excursion into public life in the 1970s until the end of the twentieth century, Mary Warnock had always been at the forefront of progressive liberal thought in Britain. She had been a supporter of the Labour Party until the mid-1960s, when she left the party because of its support for comprehensive schools and especially the abolition of grammar schools. Since then, she had been generally centre-right in her political views but when it came to social issues she always seemed to be on the same side as left-leaning people. She was with them, for example, on socially divisive matters such as the abolition of capital punishment, the abortion laws and the decriminalisation of homosexuality. In particular, readers of The Guardian who bought the paper because they knew they would nearly always agree with the opinions it expressed, were used to finding Baroness Warnock quoted as providing moral philosophical support for views they instinctively knew were the right ones to hold. So, in September 2008, it must have been a shock for these same Guardian readers to discover that their highly respected philosopher was on the receiving end of harsh criticism, not only from the reactionary right, but from socially liberal people they would normally expect to agree with her. It was the robustness of her views on death which caused spluttering over the toast and marmalade.

Mary’s views on death and assisted dying had developed over a twelve-year period, starting in the mid-1990s with the death of her husband, Geoffrey. In 1994, she had been a member of a House of Lords Select Committee on Medical Ethics. Lord Walton introduced the report of this committee in a debate held in the House of Lords on 9 May 1994. He reported that the members were unanimously opposed to voluntary euthanasia. After describing a number of distressing cases in which individuals desperately wanted to be helped to die, supported by distinguished legal opinions in favour of legalising euthanasia, he said:

ultimately, however, we concluded that such arguments are not sufficient reason to weaken society’s prohibition of intentional killing which is the cornerstone of law and of social relationships. Individual cases cannot reasonably establish the foundation of a policy which would have such serious and widespread repercussions. The issue of euthanasia is one in which the interests of the individual cannot be separated from those of society as a whole.1

Clearly Mary supported these conclusions at the time, but it seems likely that her views were already beginning to change.

In 1992, Geoffrey had started to show signs of a chest complaint that would take three years to kill him. The condition, cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis, is one in which fibrous tissue gradually invades the lining of the air passages in the lungs where oxygen replaces carbon dioxide in the blood stream.2 As the disease progresses, blood leaves the lungs with less and less oxygen. The patient becomes progressively weaker as oxygen is necessary for the creation of energy and ultimately, for survival. There is no cure, although steroid drugs can slow the progress of the disease. When oxygen levels become dangerously low, the patient is connected to a ventilator and breathes in pure oxygen. Eventually this fails to meet the patient’s oxygen needs and death ensues.

Geoffrey managed to lead a reasonably normal life until the middle of 1994 when his symptoms became more acute. He was prescribed large doses of steroids but gradually, in the summer of 1995, breathing became more and more difficult even with artificial ventilation. It was increasingly hard for him to cough. Geoffrey feared he might suffocate and was at risk of drowning in his secretions. His terror of drowning stopped him sleeping.3 According to Mary, who wrote in response to the author of a letter of condolence ten days after Geoffrey died, he was ‘stoical, indeed heroic’ in the face of his impending death, and finally decided ‘he was not going into hospital and not submit to the horrors and indignities of being unable to get out of bed.’4 He was offered a hospital bed but turned it down, preferring to spend his last days at home, nursed by Mary. He managed to hold off his death in a manner ‘typical of his courage and courtesy’5 so that he could attend the opening of new student accommodation at Hertford, named after him. On this occasion, he ‘delighted his friends and colleagues with a witty and eloquent valedictory speech.’6 He died twelve days afterwards.

On the morning of 8 October 1995, he saw his general practitioner, Dr. Nick Maurice, who prescribed morphine to ease his breathing and reduce his extreme distress. His daughter Fanny, and her daughter, Abigail, visited and Geoffrey enjoyed their company. After they left, he asked Mary to leave him and ‘give me half an hour.’ She went for a short walk. When she returned, she found him lying on the floor in the bathroom, dead. The ventilator was disconnected. She realised that he had made up his mind he was not going to go into hospital and so he took the action he did. It was, she wrote, ‘a cool, rational choice’: he had decided to take matters into his own hands and end his life.7 When Dr. Maurice returned in the late afternoon he found Mary in floods of tears on the doorstep. Geoffrey’s body had already been taken to the mortuary. Nick Maurice was in no doubt that Geoffrey had taken active steps to end his life; the dose of morphia he had prescribed would not have been sufficient in itself to cause death.8

Throughout his illness, Mary had been the sole carer. Both she and Geoffrey strongly disliked the idea of causing any interference in the lives of their children. Indeed, when he realised how much he had been shielded from the knowledge of the severity of his father’s condition, their son Felix was quite angry with his mother.9

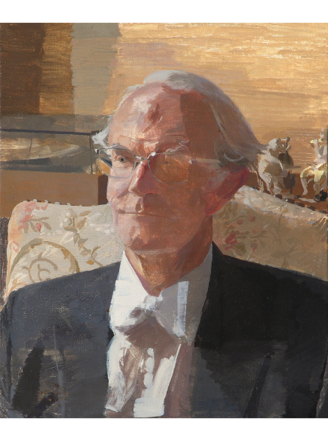

So ended forty-six years of married life. Geoffrey had been a most remarkable husband. A philosopher whose work was highly esteemed by his academic colleagues, he had gone on to become a highly successful university administrator. As Principal of Hertford College, he had overseen several substantial new building projects and taken the college from near the bottom to a proud position at the top of the Norrington Table, a league table for measuring the Oxford colleges’ academic performance according to undergraduate degree results. He is still remembered with gratitude for having rescued the college from the dismal situation it was in when he took over in 1971. He went on to serve for four years as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford. His close friend and professional colleague, the philosopher Peter Strawson, wrote of him after his death that he ‘never deviated from the clear and literal truth, and the difficult exercise of cleaving to that path he conducted, in his writings on perception and the philosophy of language, with such an absence of fussiness, with such coolness, urbanity, and elegance, that the result gave (and can still give) not only deep intellectual satisfaction but great aesthetic pleasure.’10 Although he gave the impression of an austere personality, this was misleading. According to Strawson,

he had a great capacity for enjoyment, and a lively sense of the ridiculous, being vastly and delightfully amused by the absurdities which so often cropped up in human speech and behaviour. He was a games player, a keen cricketer and golfer; and all his friends and colleagues found him a charming companion, invariably courteous and considerate, indeed chivalrous, in personal relations. In the old phrase, he was ‘a man of feeling’.11

After his death, Mary asked for and received permission to have carved on his gravestone the motto of his regiment, the Irish Guards, the two words ‘Quis Separabit’ (Who Shall Separate Us). Doubtless, these words expressed her own feelings that their partnership would endure in some way for ever.12

|

|

Fig. 10 Portrait of Geoffrey Warnock by Humphrey Ocean (1987), with the permission of the artist and of the Principal, Fellows and Scholars of Hertford College in the University of Oxford. Fig. 11 Portrait of Mary Warnock by June Mendoza (1989), with the permission of the artist and of the Mistress and Fellows, Girton College, Cambridge.

Geoffrey and Mary were extremely fortunate to have had Nick Maurice as their general practitioner. He was the last of several generations of medical Maurices who had served as family doctors in Marlborough, Wiltshire, since 1792. After Geoffrey’s death, he and Mary developed a strong friendship. Then, in 1997, Dr. Maurice found himself in the national spotlight as a result of a short article he had written in a newsletter for patients in his practice. In it he disclosed that

we doctors are practising euthanasia all the time and should be proud of it. In the past three months I have induced a quiet and easy death for two of my patients for which the relatives were grateful. That is not to say I have killed two patients. It is simply to say that I have given sufficient quantities of morphine to ensure that the physical and mental suffering of the patient, and the relative also, has been kept to a minimum.

He defined euthanasia as allowing people to die ‘peacefully and quietly.’13 As it happened, one of the patients in his practice was Sir Ludovic Kennedy, a television personality and President of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society. Kennedy read the article and gave his support for Dr. Maurice in a letter to the Wiltshire Gazette and Herald. He praised the doctor’s actions as ‘admirable for the compassion shown in bringing his patients’ suffering to an end.’14 The letter caught the eye of the national press. In the subsequent furore, Dr. Maurice received much encouragement and positive support from Mary. He was similarly praised by a number of people who supported his practice, especially from his patients, but he also had some hostile criticism, some of it linking his views with those of Mary. One angry correspondent wrote ‘I cannot understand why people like you and Lady Warnock go on talking about it publicly all the time!’15

About a year earlier, in December 1996, Mary gave an interview about end-of-life issues to a journalist, Peter Millar, that was published in The Sunday Times.16 She said that her husband’s death had ‘concentrated her mind’ on the subject. She was irritated by the attitude of the doctors who gave ever-increasing doses of morphine. ‘They always went on about doing it to ease suffering, not admitting it was killing them.’ Her argument was not with what they were doing, just with their lack of honesty. Her views on medical attitudes to elderly people who did not want to go on living were expressed with a brutal honesty. ‘I can’t bear the idea of all that money being wasted on reviving old people who can’t be bothered to go on living, who don’t want to burden their children or even the NHS.’ Her interviewer, Peter Millar, recorded his reaction to such extreme views. ‘I look, I realise, stereotypically aghast. […] perhaps I ought not to be surprised at an old lady [Mary was seventy-two at the time] advocating attitudes that come straight from the ancient world. But this is Mary Warnock, the champion of humanist enlightenment.’17 It is clear that Mary’s attitude towards euthanasia had changed over the two years since the House of Lords Medical Ethics Committee had reported in 1994, and that the manner of Geoffrey’s death had been responsible for this shift in attitude.

In 1999, Mary published An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Ethics. The first chapter, entitled ‘Death’ begins with two case examples, in both of which a doctor participates actively in bringing about the death of a patient. The first example is clearly based on Geoffrey’s final illness, though she changes the gender of the patient. The terminally ill woman she describes is painfully thin as the result of all the weight she has lost. She is too weak to move and is entirely dependent on her husband.

She is given analgesics, including morphia, which marginally ease her breathing. But she longs to die as she knows she soon will. She longs to release her husband from his terrible life, and she has had enough of her own. She is terrified of dying of suffocation […] and now she cannot sleep for thinking about it. When she does sleep, she wakes from a nightmare of suffocation.

The doctor tells the husband he is gradually increasing the morphia. Within a few weeks, the woman has died.18

In discussing this case, so clearly based on her own experience, Mary points first to the fact that, although some would suggest that the death of the woman has been brought about by ‘unnatural’ means, in fact, had it not been for the earlier ‘unnatural’ medical interventions, the woman would have died much earlier. Second, Mary raises the importance of the fact that the couple love each other and so ‘can enter into the other’s feelings and discern where each other’s interests lie.’ She describes how the dying woman has always placed a high value on independence and making her own choices. ‘She now finds that, though she wants to die, she cannot choose to do so.’ These considerations, Mary thinks, guide the couple in deciding what the right thing to do might be, in formulating their ‘private morality’ derived from a mixture of principle and sentiment.19

An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Ethics discusses a number of other issues of great ethical complexity. Nearly forty years after the publication of Ethics since 1900, Mary was by now full of relevant experience which enabled her to demonstrate how valuable it could be to focus on how people came to moral decisions when formulating public policy and on the making of moral decisions by individuals themselves.20 The chapter on ‘Birth’ focuses on her experience of chairing the Committee on Human Fertilisation and Embryology. In ‘Rights,’ she expresses once again her scepticism regarding the value of human rights that are legally unprotected, as well as her opposition to the idea of animal rights. The chapter titled ‘Where Ethics Comes From’ considers historically the religious and Enlightenment views on this subject before asserting that ‘in a precarious situation, people must assert and share certain values, or perish. It is this realisation, it seems to me, which lies at the root of the ethical.’21 The Intelligent Person’s Guide to Ethics was warmly praised in The Times Higher Educational Supplement. While criticising what he regards as Mary’s over-simplistic dismissal of moral relativism, the reviewer goes on to say that ‘this criticism should not detract from the book’s other excellent qualities. It is lucid, accessible and brims with humanity. Warnock should be applauded for her achievement.’22

* * *

By June 2003, Mary was ready to give her support to a bill on assisted dying in the House of Lords. In her speech in support of the bill, one of many introduced by Lord Joel Joffe allowing health professional assistance to terminally ill, mentally competent people who wish to end their own lives, she cited three reasons why she was in favour of this new law. First, she said, it was time for assisted death to be regulated. It was happening all the time in an unregulated fashion, and this was dangerous. Second, she asserted, it is time for the matter to be considered separately from religious belief. Instead, ‘it is the morality of compassion that must be paramount.’ Finally, it is time the wishes of the terminally ill were given the paramount importance they deserve. The terminally ill are not concerned about what will happen to them after they die or whether they will die, but with whether they will suffer ‘the deterioration—perhaps the inability to breathe, the total helplessness, or the humiliation—that will precede what they know to be their imminent death.’23

In May 2006, supporting a similar bill introduced by Joel Joffe, she made different points. She agreed that palliative care should be improved and be made more widely available. Assisted suicide should never be a substitute for good palliative care. The bill before the House, she thought, had very narrow scope to which no one could reasonably take exception. She was not persuaded by those who opposed the bill on ‘slippery slope’ grounds: this was the argument that any legislation on assisted dying will inevitably be followed by further measures making it ever easier for lives to be taken for reasons of convenience or for the saving of expense, rather than for the relief of intolerable suffering. She argued that the circumstances in which assisted suicide might be permitted were so narrowly defined and carefully safeguarded as to render the slippery slope argument inapplicable. In particular, there was no realistic threat to disabled people. Clearly, she suggested, people who wanted an assisted death could in no way be regarded as immoral. Why, she asked, should it be expected that they should follow ‘the morality of religious or medical leaders rather than a morality in which they do believe, not another which would compel them to live against their wish?’24

The following year, in 2007, Mary was approached by Dr. Elisabeth (Lisa) Sears who was thinking of writing a book on the management of terminal illness. Dr. Sears (professional name Macdonald) was a recently retired clinical oncologist with enormous experience in the field. She wrote to Mary asking for advice and was invited to tea in the House of Lords. They discovered many mutual interests and talked non-stop until the staff came to lay the tables for dinner. Mary proposed they wrote a book on assisted dying together. She would provide the philosophical background and Lisa would describe the clinical situations in which an assisted death might become desirable to a terminally ill patient. So Mary wrote chapters on the fundamental principles relevant to the debate on assisted dying, on the importance of mental competence and on the ‘slippery slope,’ while Lisa wrote chapters giving clinical details of relevant cases and describing the methods currently available to ease death.

The title of the book, Easeful Death, was taken from the poem ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ by John Keats which contains the lines: ‘Darkling I listen, and, for many a time, I have been half in love with easeful death. […] Now more than ever seems it rich to die, To cease upon the midnight with no pain.’25 By coincidence, though the co-authors did not know it, the title they chose echoed the title of a book A Very Easy Death, by Simone de Beauvoir, the lover for many years of the existentialist philosopher, Jean Paul Sartre, about whom Mary had written copiously nearly forty years previously. De Beauvoir’s book with its ironic title was about the distressing last months of her mother’s life, in which she was tortured by pain and humiliating incontinence. When, after her mother’s death from cancer, Simone de Beauvoir’s sister, Poupette, agonised to a nurse about the suffering her mother had endured, the nurse replied ‘But, Madame, I assure you it was a very easy death [une mort très douce].’26

In their book, Mary and Elisabeth Macdonald discussed why someone might qualify, under new legislation, for an assisted death. The experience of intolerable suffering unrelieved by palliative care was likely to be the main reason, but the authors added a further, much more controversial reason. They turned on its head the argument of those who objected to a new law on assisted dying on the grounds that some people might want to die because they felt caring for them was posing an intolerable burden on their relatives and friends. Those who objected to legislation usually took the line that no relative or friend would regard such caring as a burden and wish for the assisted death of the person they were looking after unless they had a mercenary reason for doing so. Only greedy relatives, who could not wait to get their hands on the money of the dying person, it was suggested, would think of caring as a burden. Mary Warnock and Elisabeth Macdonald took a very different view. They wrote:

It is not difficult to imagine feeling that one’s children were getting impatient either for their inheritance or simply for relief from the burden of care and that one had not so much a right to ask for death, as a duty to do so, now that it was lawful to provide it. There undoubtedly exist predatory or even exhausted relatives. But it is insulting to those who ask to be allowed to die to assume that they are incapable of making a genuinely independent choice, free from influence. (Indeed, there are people so determined to confound their children, if they see them as hovering over a hoped-for corpse, that their will to spite them by staying alive may outweigh their wish to escape their own pain).

In any case, to ask for death for the sake of one’s children or other close relatives can be seen as an admirable thing to do, not in the least indicative of undue pressure, or pressure of any kind. Other kinds of altruism are generally thought worthy of praise. Why should one not admire this final altruistic act? And it would not be wholly altruistic: the desire to avoid squandering resources, or being a burden is combined, in the cases we are considering, with a sense that prolonging life is both futile and painful. It is idle to try to separate these motives. Part of what makes a patient’s suffering intolerable may be the sense that he is ruining other people’s lives. If he feels this keenly, and asks to be allowed to die, he is not a vulnerable victim, but a rational moral agent.27

The reviews of the book were largely positive. The distinguished philosopher, Onora O’ Neill, a former pupil of Mary’s at Oxford, but an opponent of a new law on assisted dying, wrote in The Lancet: ‘The authors set out with exemplary clarity reasons for prohibiting or permitting physicians to “help” patients to die. Their arguments are cogent, illuminating, and in many ways convincing.’28 Steven Poole in The Guardian, wrote: ‘An extremely lucid and sympathetic interrogation.’29 In The Times Higher Education Supplement Julia Stone called it a ‘sensitive and succinct book […] This book not only has the power to stimulate informed discussion, but also to shape social policy and inform good professional practice. […] ”Easeful Death” deserves a wide readership, and it should be compulsory reading for politicians and policymakers.’30 The book stimulated much popular interest. The two co-authors were invited to talk about it at a number of book festivals, including Hay-on-Wye and Cheltenham. On long train journeys they took together, they became good friends and continued to see each other and correspond until, two or three years before Mary’s death, communication became difficult and they lost touch.31

The argument put forward in the book that people who felt a burden should be able to ask for an assisted death was out of step with most progressive thinking on the subject. The lead British organisation Dignity in Dying, campaigned only for terminally ill, mentally competent people thought to be in the last six months of their lives who were enduring intolerable suffering to have the legal right to health professional assistance to end their lives. Humanists UK, on the other hand, did not see why it should only be people in their last six months who had this right. Anyone terminally ill who was suffering intolerably should also qualify. But the idea that feeling oneself a burden should justify requesting an assisted death was quite new, although it did not go as far as more extreme but poorly supported organisations such as EXIT International, which campaigned for anyone who had had enough of life, regardless of the reason, to be able to access help to end it.

It might have been dissatisfaction with the lack of notice taken of the new argument in the book that led Mary to go further. In October 2008, in an interview with the Church of Scotland’s magazine Life and Work, she repeated her view that the terminally ill who felt a burden to others should be given the right to die with health professional assistance. But now she talked of them having a ‘duty to die.’ She added: ‘I’m absolutely, fully in agreement with the argument that if pain is insufferable, then someone should be given help to die, but I feel there’s a wider argument that if somebody absolutely, desperately wants to die because they’re a burden to their family, or the state, then I think they too should be allowed to die.’32 This was highly provocative.

Mary also went further than others when it came to dementia. ‘If you’re demented, you’re wasting people’s lives—your family’s lives—and you’re wasting the resources of the National Health Service.’ Most of those who advocated for a new law on assisted dying thought it was important that the person requesting to die should be fully mentally competent at the time the final decision was made to go ahead. Of course, in the early stages of dementia, a person would be competent to make this decision, but the expectation was that people with dementia would not wish to die until the disease had advanced to the point when, for example, they did not recognise their close family members. At this point they certainly would not be mentally competent. Those who wished for sufferers with advanced dementia to be allowed to have their lives terminated therefore proposed that people in the early stages could make advance directives stating that once their disease had progressed to a point when their quality of life was unacceptable, they could have their lives terminated.

This time round, there was no lack of publicity for the views Mary had expressed. Not surprisingly, those with strong right-wing and religious views were most forthright in their criticism. Nadine Dorries, a Conservative MP, wrote,

I believe it is extremely irresponsible and unnerving for someone in Baroness Warnock’s position to put forward arguments in favour of euthanasia for those who suffer from dementia and other neurological illnesses […] Because of her previous experiences and well-known standing on contentious moral issues, Baroness Warnock automatically gives moral authority to what are entirely immoral viewpoints.33

Phyllis Bowman, executive director of the campaign group Right to Life, which was strongly supported by religious organisations, wrote of Mary’s interview: ‘It sends a message to dementia sufferers that certain people think they don’t count, and that they are a burden on their families. It’s a pretty uncivilised society where that is the primary consideration. I worry that she will sway people who would like to get rid of the elderly.’34

Equally forthright criticism came from organisations with which Mary much more frequently found herself in tune. Neil Hunt, the chief executive of the Alzheimer’s Society, said:

I am shocked and amazed that Baroness Warnock could disregard the value of the lives of people with dementia so callously. With the right care, a person can have good quality of life very late into dementia. To suggest that people with dementia shouldn’t be entitled to that quality of life or that they should feel that they have some sort of duty to kill themselves is nothing short of barbaric.35

Sarah Wootton, the Chief Executive of Dignity in Dying wrote in The Guardian in strong opposition to Mary’s view: ‘absolutely no one has a “duty to die”. Consequently, when the law on assisted dying does change it will include a legal safeguard to ensure that any terminally ill adult who chooses an assisted death is mentally competent: capable of making the decision and understands its consequences.’36 There was similar criticism from medical ethicists. Nancy Jecker, writing in the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics declared: ‘Encouraging elderly people to die, or helping them to end their lives, would certainly save money and free up resources. But this approach is neither ethically defensible nor necessary.’37 Some, such as June Andrews, a registered mental nurse, although they disagreed with Mary’s views, nevertheless welcomed the fact that she had opened a debate. She wrote:

Baroness Warnock is a dignified philosopher who has led an amazing intellectual life. Now, aged 84, she was asked for an opinion and expressed it. She said that euthanasia and assisted suicide are a good idea and that some of us have a duty to kill ourselves when we become a burden. Personally, I do not agree and never have. But I am glad the debate is now in the open.38

It should be added that around this time, there were two more prolonged and distressing family deaths which confirmed Mary’s developing thoughts on these issues. The first was her sister Stephana’s husband, Duncan Thomson, who died a particularly hard death from cancer. Then her older sister Jean Crossley died. Mary maintained she had been unnecessarily kept alive at the age of 101 when she was hospitalised with pneumonia. She wrote about how angry, then depressed, her sister became at her inability to prevent this so-called treatment when she was ready to die. In 2009, at around the time of Jean’s death, Mary had a more unexpected and even more painful confrontation with a death in the family. Her daughter, Stephana, (Fanny) died of pneumonia when she was only fifty-three.39 Mary was naturally deeply upset and repeatedly asked herself how she could have done more to help her daughter.

To return to the assisted dying issue, it is worth considering in more detail Mary’s view that people who face a progressive form of dementia ought to be able to stipulate, in advance of the event, their wish to die. If they are not competent to make a decision themselves, their proxies should be able to decide on an assisted death on their behalf once they have reached an advanced stage of the condition. In the Netherlands, it is legal for doctors to end the lives of people with dementia, even if this is at an early stage, if they have previously expressed a wish for this to happen. Polling in the Netherlands suggests that about half the population support this position, but in other countries there is greater reluctance to extend assisted dying criteria to dementia sufferers. A majority want a right to make such a momentous decision for themselves, but not for others to make it for them. Amongst the medical profession even this limited position does not command support although there are strong signs that opinion amongst health professionals is beginning to change.

There are three main objections to the type of legislation currently applied in the Netherlands. The first is that expressed by the Alzheimer Society. Many people with dementia enjoy a good quality of life and there is no reason why they should want their lives to end. Further, much can be done to alleviate the symptoms of dementia so what is needed is not a defeatist attitude but a positive approach. This point of view is, of course, valid for those at an early stage of the disease, but much more dubious, indeed Mary thought ridiculous, for those whose disease has progressed to the point at which they have lost the ability to communicate, need help with toileting and feeding and can no longer recognise their family members or friends.

A second objection is made on the principle that it can never be right to end someone’s life without their informed consent at the time the final decision is made. As Professor Ray Tallis, a passionate advocate for assisted dying for the mentally competent, terminally ill patient has put it, ‘informed consent at the time a lethal medicine is taken is a totally necessary safeguard against abuse.’40

A third objection can be described as pragmatic. In most countries, such as the UK where euthanasia legislation is not in place, it is believed that the general public finds it abhorrent to suggest that people with dementia or other fatal illnesses should be able to end their lives because they feel they are a burden to their families and to society. People with dementia and other terminal illnesses, it is widely thought, should be reassured that their family members and society are happy to continue to look after them for as long as it takes. Many members of the House of Commons who took part in the debate on assisted dying held in September 2015 reported this was the view that had been frequently put to them by their constituents.

Mary vigorously refuted these objections in an unpublished lecture titled ‘Easeful Death for the Very Elderly’ delivered to the Society of Old Age Rational Suicide (SOARS) when she herself was eighty-six in 2010. She pointed to the neglect of the plight of people with dementia in discussions of assisted dying. It was widely argued that a health-professional-assisted death should not be permitted for people with advanced dementia because they could not give informed consent. Even if people had made advance directives asking for such a death if they became severely demented, they might have changed their minds. But, Mary argued, the concept of a change of mind was meaningless. ‘The patient has no mind left to them to change, no settled intention, no powers to foresee the future or consider the course of a whole life.’41 This made the advance directive a necessity for those who do not wish to continue to live once they have developed severe dementia.

Mary views the protests of organisations such as the Alzheimer Society that people with advanced dementia can be happy and enjoy life to be offensive. She writes ‘I simply do not want to think that, in the future, I may be patronised by people pretending to believe my fantasies […]’42 As for the argument that people should not be allowed to take their own lives because they feel a burden, Mary asks, as she had many times previously, why should ‘altruism turn out to be the thing that is avoided?’ at the end of life.43 For her this is a moral issue ‘of personal integrity, of trying to behave consistently and trying, roughly speaking, to do what is right by other people’44 It is also a philosophical issue. ‘Once the brain has reached a certain stage of tangles and degeneration which cannot be reversed, I believe I am not the same person as I was and I can take no further responsibility as a moral being.’45 She goes on to note that some people think it is wrong to take life no matter how deteriorated a person is. This thought she sees as coming from the ancient idea of a spirit or essential being surviving the body. Somehow, she maintains, ‘we must escape this dualism, this Cartesian separation of mind from body.’46 Mary recognised the strong resistance to the idea that advance directives should be honoured even in the cases of advanced dementia but, she writes ‘I believe that society is moving in this direction.’47

Of course, as Mary rightly wrote, societal attitudes may change, as they clearly have in the Netherlands. Further, there have been societies in the past and there continue to be societies today where suicide is not only sanctioned but, in certain specified circumstances, is regarded as the honourable course to take. In ancient Greece and Rome those condemned to death were given the option of ending their own lives and it was regarded as morally desirable for them to do so. It was in such circumstances that Socrates drank hemlock. Today, or at least until very recently, seppuku, or ritual self-disembowelment was practised by some Japanese soldiers at the end of World War II in 1945 as an alternative to dishonourable surrender. The attitudes of British society to assisted dying in advanced dementia are a very long way from these, at least to Western minds, exotic examples, though nearer to those held in the Netherlands.

Mary took part in two further debates on terminal illness in the House of Lords. In December 2013 she spoke in a debate on health at the end of life introduced by Lord Dubs. She reiterated her view that the present state of the law on what doctors might and might not do at the end of life was ‘unsafe and intolerable.’ She drew attention particularly to the plight of people who were dying and regarded as incompetent to make decisions about their own care. ‘I cannot think of anything more humiliating,’ she said, ‘than to say that I wanted to die and that my life was no longer worth living only to be told that I was suffering from depression.’48 She thought it was a ‘scandal’ that so few people made advance directives. General practitioners were the culprits who did not do enough to make sure their patients were informed about advance directives. She said that she often talked to her GP about her own death.49

In July 2014, Mary spoke in a debate on a bill introduced by Lord Falconer to legalise health-professional-assisted dying for the terminally ill. At that time, the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) had produced guidelines which made it clear that relatives who assisted a terminally ill person to die would not be prosecuted if it could be shown that they did so out of compassion for someone who clearly wanted to die. Mary pointed out that DPPs change, so the policy might be changed, and a more permanent solution was needed. She said that, although opponents of the bill claimed the numbers involved were small, this was not the case. As many as 30,000 people suffered ‘bad deaths’ each year. Even if the numbers were much smaller, it was wrong for them to have to suffer unnecessarily. She then reverted to the unpopular argument she had previously advanced. ‘It is somehow thought to be wrong,’ she said,

that people who are approaching death and are terminally ill should take into account the suffering, expense and misery they are causing to their family as they are being a burden. Of course, they are also a burden to the state. Why is it that this is thought to be a wrong motive, or part of a motive, for wanting to end one’s life when it is coming to an end anyway?

Up to that point in time, it was thought that altruism was a good thing: ‘why should it be regarded differently now?’50 Some supported her, but many did not. The bill was passed by the House of Lords by a clear majority, but a similar bill introduced into the House of Commons the following year by Rob Marris was heavily defeated.

At the time Lord Falconer introduced his bill on assisted dying there was a strong groundswell in the House of Lords in support of such a measure. Indeed, there was a team consisting largely of crossbench peers who actively and often successfully canvassed support. Mary was not part of this group. Her view that seeking death was an altruistic act by dying individuals relieving both the state and their families of the intolerable burden of looking after them was not seen as helpful. The team disagreed with her on advance directives and feared that the way Mary expressed her extreme ideas might turn some against their more modest proposals.51

* * *

Over the last decade of her life, Mary began to consider her views on the origins of morality and its relationship to the law and to reflect on her own religious beliefs. She was motivated to do this particularly by the need to justify her views on euthanasia against those of the established Anglican clergy. She admitted that in writing about the relationship between morality and the law she was travelling a very well-trodden philosophical path, but she articulated the fundamental problem in a way which remains hard to answer: those who frame laws must do so by drawing on a pre-existing moral framework. Thus morality must precede the law, but where then does such morality come from? She published her conclusions in a book, Dishonest to God (2010).52

She begins by examining the widely-held assumption that religion is the basis of morality. Obedience to God’s will may, for the religious, enable the faithful to lead ‘a good life,’ but the values of non-believers, now a majority in British society, are derived more from humanity itself than from religious doctrine. Mary recognises the danger that the separation of morality from religion can lead to moral relativism. In this connection she quotes Lord Denning who, in 1953, wrote that ‘without religion there can be no morality and without morality there can be no law.’53 This view she sees as now outmoded in Britain but still extant in the United States where no politician would dare to put his name forward for election unless he subscribed to a particular religious faith. The rejection of this line of argument in Britain has led, she writes, to a reaction by the Anglican Church which insists on the relevance of Christian belief to political life. Rowan Williams, for example, while Archbishop of Canterbury, pronounced that ‘Christian ethics is relentlessly political.’54 Some radical Anglicans go further and join with the Catholic Church in maintaining that unless there is some sort of supernatural standard, people can have no meaningful idea of what is good. They assert that democracy can only function properly if it is based on a ‘correct’ understanding of the human person and this understanding must accord with Christian teaching.55

Such involvement in political decision-making by the Church takes many forms. Mary was especially angry at the amount of lobbying in which the clergy engaged at the time Lord Joffe’s bill on assisted dying was debated in the House of Lords in 2007. She describes how the Catholic Archbishop of Cardiff announced he was launching the biggest political campaign by the Church in its whole modern history to oppose this bill. The campaign ‘culminated in an article published in The Catholic Times entitled ”Legalising Euthanasia Turns Carers into Killers” which included a photograph of 24 children who had been murdered by the Nazis in the late 1930s.’56 So successful was the campaign that the bill was defeated at second reading, thus breaking a long-standing tradition that a Private Member’s Bill should always be passed to the next stage. This occurred despite the fact that the provisions of the bill were supported by 80% of the population. Mary believed that ‘the conflation of religion with morality and the habit of according moral authority to the declarations of religious leaders, directly led to this outcome.’57

She goes on to discuss alternative, non-religious bases for moral judgements. She notes that concepts of human rights are often pressed into service as providing a kind of fundamental law, but Mary is sceptical. Rights, she says, are frequently claimed but can only be regarded as true rights if they are enforceable. She refers to the UNICEF Declaration of the Rights of the Child, published in 1990, as a ‘meaningless proclamation.’ The ideals the declaration declares to be the rights of children, such as the right to play and to exercise their imagination in the arts are, she accepts rather dismissively, ‘very nice,’ but ‘nobody has or could have a duty to ensure they are fulfilled.’58

So, if one cannot look to religion or to the language of human rights to underpin morality, where can one turn if morality is not to become simply a matter of personal preference? Some believe that among non-religious people, it is only the retention of the vestiges of religion taught to them by their parents or grandparents, that gives them a sound moral sense. Mary disagrees. She notes that Kant and Hume proposed that humans have an interest in sharing moral values if they are to get on together, and Bentham thought that such shared values could also be based on imagined, as well as real, outcomes. Mary’s own view was that human beings need a shared morality to alleviate the predicament in which they all find themselves when facing disaster, loss and death. She sees moral judgement as based on sympathy and feelings for others. The existence of such feelings depends on the imaginative capacity of human beings, the one defining feature that distinguishes them from other animals. Now our imaginations might lead us to different moral conclusions, but Mary believed this did not happen. The central requirement of such moral behaviour is the ability to resist temptation, to overcome the attraction of yielding to immediate selfish interest. ‘Thus, the resistance to temptation is at the heart of individual morality.’59

She pointed out, following Auguste Comte, the French positivist, that if moral behaviour is only performed in obedience to divine commands because of the promise of reward in heaven, this can hardly be regarded as morally ‘good.’ In contrast, when such unselfish behaviour arises in a social context, from community, cooperation and love, then morality has been created which even a non-believer can accept. Inevitably, there will be an element of moral relativism in this view, for as times change and values change, so will moral judgements change, but, Mary maintained, the central core of what lies at the heart of such judgements will remain solid and invulnerable.60

In the light of these reflections Mary’s hostility to clerical interventions in politics becomes much more understandable. She put her feelings into words most powerfully in an interview with Laurie Taylor after the publication of Dishonest to God in 2010. ‘I find it extraordinarily irritating,’ she said,

when people treat the bishops in the Lords, or the Church elsewhere, or the clergy in general, as moral experts. I think that is an outrageous thing to believe, but people still believe it automatically, without thinking. They think that these members of the Church, of any religion, have a special insight. And often that insight is narrowed down to Christianity alone. There was a perfect example in one House of Lords debate when Lord Lloyd of Berwick, who’s a former president of the Law Society, suggested, in the aftermath of the Director of Public Prosecutions’ guidelines about [right-to-die campaigner] Debbie Purdy, that one very important step forward would be to change the law of homicide so that it became possible for a jury to say to a judge that there were mitigating circumstances in some cases of murder. Because at the moment if it’s murder then it’s life. And Lord Lloyd wanted to be able to distinguish between gain-induced murder and a mercy killing. Every single person who spoke in favour of this was a lawyer and they all agreed that this would be an enormous improvement on the law. And then up jumped the Bishop of Winchester and said, ‘Ah, but this would give the wrong message. This would show that we didn’t, after all, care about life, which is sacred.’ That was the collapse of all argument. That was it. That was the end of it. It was terrible.61

Despite her views on the inappropriateness of the position of bishops in the House of Lords, she never advocated their removal. Indeed, she wrote: ‘I even believe it is right that the established church should have a place in Parliament, provided that no one supposes that the Bishop’s Bench in the House of Lords has a monopoly of moral authority.’62 This inconsistency was symptomatic of her deep affection for the Anglican Church.

Mary’s beliefs might have resulted in her seeing herself as a humanist, but she explicitly denied this possibility. When she spoke in a House of Lords debate in 2013 on the contribution to society of atheists and humanists, she said

I am not a member of the British Humanist Association. I consider myself to be a Christian by culture and by tradition. I frequently attend services of the Church of England, and one of my greatest passions is church music, as sustained in the great English cathedrals and colleges, as well as the great oratorios and passions. I do not want the Church of England to be disestablished, and I regard my loyalty to the sovereign as loyalty to the head of the church as well as to the head of the state. Having said that, I suppose I should confess that I am an atheist.63

* * *

Following his four-year term as Vice-Chancellor, (or ‘four-year sentence’ as he sometimes called it), from 1981 to 1985, Geoffrey returned to his position as Principal of Hertford College until he retired in 1988. On his retirement, the Warnocks sold their small house in an Oxfordshire village, Great Coxwell and bought Brick House, in Axford, in Wiltshire. This house was a surprise in the sense that it was a newly built bungalow sitting on the top of a small hill in the middle of what, at the time, could best be described as a building site. But, according to Mary, it ‘had a marvellous view across the Kennet Valley to more downs beyond and the edges of Savernake Forest.’64 It was built on chalky soil, unpromising for a garden, but she and Geoffrey immediately saw its potential and, over the following years, created a wonderful garden of which they were very proud. They both loved it.65 Geoffrey settled down to a relatively (for him) inactive life, reading, watching television, gardening and what he himself called ‘footling about.’ He began to enjoy cooking and even shopping. For three years after his retirement, Mary continued to spend the week in Cambridge where she continued as Mistress of Girton until 1991, returning to Axford every weekend. Then, shortly after Mary herself retired, Geoffrey fell ill and looking after him gradually became a more and more time-consuming occupation for her. For about two years before Geoffrey died, Mary very consciously withdrew from all but her most essential public positions. Quite apart from Geoffrey’s everyday needs, there was always the possibility of a crisis and she was determined to be on hand to deal with unexpected demands.

.png)

Fig. 12 Mary and Geoffrey Warnock in the garden of their Axford home (1993), provided by the Warnock family, CC BY-NC.

Mary’s genuine love of their Axford home did not survive Geoffrey’s death. She immediately knew she could not continue there and soon began to plan a move away from Brick House. This was the start of a series of moves which perhaps reflected the spirit of restlessness already noted at other times of her life, but which was also a great source of pleasure and creativity. She simply loved having new decorative and gardening projects. She chose to buy a very different characterful house, 4 Church Street, in Great Bedwyn, a few miles from Marlborough, in Wiltshire. One of the drawbacks of the Axford house had been that it had a steep drive which often became hard to navigate by car (or indeed on foot) in winter. In complete contrast, Great Bedwyn had a main-line station from which the trains ran directly to London, Paddington. Following Geoffrey’s death, she was determined to take a more active role in the House of Lords, so to have a main-line station within walking distance of her home was a huge benefit.

When she ceased to be Mistress of Girton in 1991, Mary was sixty-seven: she never again held a salaried position. She had been an infrequent attender at the House of Lords while at Girton, but she had bought a flat in Shepherd’s Bush which she could use as a London base. However, as Geoffrey’s illness progressed her overnight stays became less frequent and she rented a room to use as an office in her youngest daughter, Boz’s house in Camberwell. It was only after Geoffrey died that she was free to contribute more to parliamentary business and she was soon serving on a number of committees and attending on most days the House was in session.66 For some years Mary also had an office of her own in the Palace of Westminster but with the large increase in the number of peers, this was taken away from her. From 2012 until her retirement from the House of Lords in 2015, she shared a room with three other life peers, Molly Meacher, Elaine Murphy and Valerie Howarth, all distinctly younger than her. Molly Meacher and Elaine Murphy describe her as having been incredibly focused. She had no secretary, made her own arrangements for what seemed like an endless number of lecturing engagements around the country and, when not on the phone, was researching and writing her latest article or book. She seemed to have no close friends among her fellow peers and, unlike many of the others, virtually never put in an appearance at the Bishop’s Bar or restaurant where people tended to go to meet colleagues for coffee, lunch or dinner. She was definitely not ‘clubbable’ in any sense of the word. She was, however, not at all unfriendly.67 When Elaine Murphy first took her seat in the Chamber, she sat next to Mary who whispered to her ‘I gather you are a psychogeriatrician.’ When Elaine admitted she was, Mary responded ‘Ah well, you’ll have plenty of trade here.’68 She prepared carefully for her contributions to debates and, when she did speak, was listened to with great attention and respect, though she herself felt she never performed at the level she wished. Molly Meacher described her as ‘a formidable woman. She had an outstanding mind combined with immense humanity. There are lots of people with outstanding minds, but she enhanced justice and fairness in the world. Her reports on excluded children treated unfairly meant their plight was brought into the mainstream.’69

She spoke on a variety of issues in which she had some special knowledge, especially matters concerning children, education at all levels, and genetics. Her support on any issue was greatly valued. In 2014, she spoke in favour of a motion on drug reform introduced by Molly Meacher, who was extremely grateful for her support.70 Mary described how her own experience with her son, James, and the correspondence she had received had changed her mind on the subject. She also described the contents of a letter she had received from a former student of hers with multiple sclerosis, whose symptoms were greatly relieved by cannabis.71

When she reached her eighties in 2004, Mary often reflected on the predicament of the elderly and wrote about her own experience of getting old. In an article published in The Guardian in September 2007, she wrote: ‘For the first time I feel that I am an old woman […] my knees are stiff, and I am inclined to hobble.’ But she finds much compensatory pleasure in recollection of activities she will never repeat. ‘Even of the things I truly loved, like riding, having babies, playing in an orchestra or sex, I think with pleasure that I understand them without inappropriate hankering.’ She sees herself not in a second childhood, but in a second adolescence.

People think of adolescents as perpetually miserable, embarrassed and lacking in confidence and of course the aged can feel like that sometimes. But for me, adolescence was mostly a time of blissful solitude and no responsibilities. It was a time of discovery, of poetry and Greek tragedy, music and Wordsworthian sentiments about nature. All these things seem fresher and more intense, now that I have settled for being old, and have again the solitude to enjoy them.72

Mary’s sense of being old as adolescence without the angst is highly typical of her positive attitude to so many things. It was a standing joke in the family, encouraged by Geoffrey himself, that he ‘had a duty’ to die before she did as she was one of ‘nature’s widows’ and should live to enjoy this period of her life.73 Indeed, she did.

She remained extremely active as a public figure and in writing for newspapers. Her interest in seeing life as a woman in no way diminished. As we have seen, at all points in her life, as young don, as headmistress of a girl’s school, as Mistress of Girton, she had had a strong interest in clothes and had delighted in shopping for clothes for herself and other members of her family.74 In an interview with The Observer’s fashion correspondent, Mary fiercely rejected the idea that once you are over the age of forty, it doesn’t really matter what you wear.75 She complained that every article about clothes was written for the young. However, when the journalist examined Mary’s wardrobe, it revealed that she completely disproved her own theory. Everything seemed to come from the pages of glossy magazines. Her favourite possession was ‘a man’s black hat, without which no fashion model would have looked completely dressed last winter.’76 Not only her clothes, but ‘her collection of bangles, necklaces and belts would not disgrace the fashion page of a Sunday newspaper.’ As her views on Margaret Thatcher’s clothes, described in Chapter One, revealed, Mary thought that a woman’s choice of clothes reflected her personality. In her own case, the way she dressed reflected her exuberant, energetic, and, above all, feminine persona and façon de vivre that would persist almost to the end.

In 2010 she sold the house in Great Bedwyn and bought a small house in Lower Sydenham in south-east London. This was a characteristically bold decision; she was moving to London in her late seventies, an age when many might be contemplating a move in the opposite direction. But her logic was, as ever, clear: she expected her eyesight and her general health to deteriorate as she grew older, and she wanted to live within reasonable access of the best hospitals and to public transport. She chose Lower Sydenham partly because it was affordable but largely because the house was within walking distance of Maria and her family. Maria was, at this time, Head of Art at Dulwich College. Mary greatly improved the property, indoors and especially outdoors: she removed the ‘hideous garage’ erected by the previous owner and, as with all her homes, re-invented the two gardens, one at the front and one at the back.77 Mary benefited enormously from being so close to her youngest daughter, and was delighted to take up her husband Luis’s willingness to help her tackle some quite major projects round the house. But the cosiness of these domestic arrangements was not to last for long because Maria was offered an irresistible opportunity to launch a new art department at one of Dulwich’s overseas schools in Singapore. Shortly before her retirement from the House of Lords in 2015, Mary sold her house and moved ‘round the corner’ into the modest ground-floor flat which Maria and her family had recently vacated. Here Mary lived and continued to work until her death in March 2019.78 According to Norma Scott, the retired Jamaican nurse who lived two doors away, if you walked past the flat, most of the time you could see her working in the front room at her computer.79 Her very poor eyesight made it difficult for her to see the screen, although it is fair to say that her love-hate relationship with computers was not greatly different from her relationship with all other things mechanical. Cars were always rebellious and washing machines and other domestic appliances seemed wilfully uncooperative in her hands. She was not very skilful in the art of word-processing. She continued, however, to write articles, even providing, shortly before she died, a substantial piece for The Observer which was commissioned at six p.m. one evening with a deadline of ten a.m. the following morning. She told Felix and his daughter, Polly, who visited her for lunch later that morning, how staying up into the small hours made her feel young again, like an undergraduate with an essay crisis.80

Most of the time, she was at home alone, though she never complained of being lonely. She was very much in touch with her children. She had visits from Felix and from Kitty who came around about once a week for lunch which Mary prepared for her. James came to see her when he was down from Liverpool where he lived and worked. Maria, now working in South-East Asia, spent time with her on her visits back to London. Numerous nieces, nephews and occasionally grandchildren and great-nephews came to visit. In many cases she had been very kind and helpful to them in the past and they were all fond of her.81 Occasionally other friends and relatives came round. She enjoyed holidays with one or more of her children and their families in rented cottages in different parts of the country. Christmas was usually spent in Liverpool with James’s family, but she declined to go there for her last Christmas in 2018 and appeared to have spent most of the day in bed.

Throughout these last years of her life, Mary was troubled with poor eyesight and hearing. All the same, she remained active and was able to manage a trip to Tel Aviv in May 2018. In the autumn of that year, now ninety-four, she suffered a number of mini-strokes. For a few days she was weak and a little confused, and the experience frightened her so much that she decided it would be sensible to move into a care home. The possibility of an eventual move into care had been anticipated; the previous year she and Kitty had visited a number of potential homes and identified the one which Mary preferred, or at least disliked less than the others. This was Peasmarsh Place, near Rye in Sussex, and arrangements were hastily put in place for a trial two-week stay. Despite her frailty, she was deeply reluctant and delayed packing until the last possible moment and, when she arrived, driven there by Kitty and Felix, she had to be more or less dragged through the door, repeating all the time ‘This is death. This is death.’ She was given a beautiful room and received excellent care including, most importantly, a complete review and proper organisation of her medications. This enabled her to make a remarkable return to tolerable good health with the unfortunate consequence that she quickly came to see herself as confined against her will. A week after her admission, Felix and Polly visited her and took her, on a bright but windy day, to the beach near Rye. Walking with Polly on the sands in the teeth of a howling gale, ice-cream cone in hand, she pronounced this to be ‘the happiest day of my life.’ The return to Peasmarsh Place was a shock after the elemental pleasures of the wild beach, and it was immediately clear that she had had enough of the ‘care’ experiment. Indeed, she desperately wanted to return home there and then. At last, though, she agreed to remain one more night provided that Felix return as early as possible on the following day having made the necessary arrangements for her rapid discharge from ‘care’ and for her return to her own home in London.82

Mary’s brief stay at Peasmarsh House was a turning point. Following her discovery of how much she disliked being ‘cared for,’ both her mental and physical state improved. She had no more mini-strokes, her mood lightened and she found a renewed determination to manage her own life, for better or worse. Despite the fact that her eyesight was poor, she continued to do her own shopping in the local Sainsbury’s supermarket about half a mile away. The route she took to Sainsbury’s was along a path away from the road, beside a little river of which she was very fond.83 On one occasion, she did fall outside her flat grazing her forehead and damaging some fingers. An ambulance was called but she refused to get in. Her neighbours insisted and she went off to Lewisham Hospital, returning the same evening. Norma Scott, her neighbour, offered to help with the shopping and gave Mary her phone number, but Mary never contacted her. Even Norma’s offers to carry her shopping for her were turned down. As Norma remembered her, ‘She was a remarkable lady. Just so independent.’84 She was indeed determined not to be a burden.

Finally, on the evening of Tuesday 19 March 2019, she went to bed, leaving not for the first time a saucepan on a hob she had forgotten to turn off. During the night, her upstairs neighbour noticed smoke coming from her flat. Without her hearing aids she could not hear the front doorbell or the phone, so the police and fire service were called. Her front door was broken down and a serious fire averted. Once again, she refused, against all persuasion by the police among others, to go to hospital to see whether she had suffered any damage from inhaling smoke. Her neighbours left her to go back to bed at three a.m. but when her gardener, Peter Lawrence, called at eight a.m. the following morning, there was no reply when he rang the bell. He had the key and entered to find Mary lifeless on the bathroom floor. She had suffered a massive stroke and would have died instantly, thus succeeding in her determination to live her life to the end without being a burden to anyone.85

Mary’s ashes were interred beside those of her husband, as she wished, in the graveyard of St. Michael’s Church, in Axford, Wiltshire. An interment ceremony was held beside the grave followed by a service in St. Mary’s, Great Bedwyn and a lunch for family members and her few surviving Oxford contemporaries including Susan Wood and Ann Strawson. The service was taken by her niece, Stephana’s daughter, the Reverend Canon Celia Thomson, Dean of Gloucester Cathedral. There were readings from Wordsworth’s ‘Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey’ and Keats’ sonnet ‘To Sleep.’ Later that year, a well-attended Service of Thanksgiving was held on 22 October 2019 in St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster to celebrate her remarkable contribution to public life over a period of nearly half a century.

On 9 February 2019, less than six weeks before she died, she was interviewed by Giles Fraser, an ex-Anglican priest, for a series titled Confessions. In this series, Fraser talked to a number of well-known people about matters they did not usually discuss and might be reluctant to make public, particularly their religious views. (Mary was not reluctant in the slightest degree.) She agrees with him that she thinks of herself as an ‘atheist Anglican,’ resisting when he tries to persuade her otherwise about the existence of God. ‘I don’t think we need a God,’ she says firmly. In her last public words, based on the Epistle of St. John, she claims instead, ‘Loving one another is the most important value.’86

1 House of Lords, Hansard, 554, 1344, 9 May 1994.

2 Mary Warnock, personal communication.

3 Nick Maurice, personal communication.

4 Mary Warnock, personal communication, 18 October 1995.

5 Peter Strawson, 2004.

6 Ibid.

7 Mary Warnock, personal communication, 18 October 1995.

8 Nick Maurice, personal communication.

9 Felix Warnock, personal communication.

10 Peter Strawson, 2004.

11 Ibid.

12 Mary Warnock, Kitty Warnock, personal communication.

13 Nick Maurice, Marlborough Medical Practice Newsletter, August 1997, pp. 9–10.

14 Ludovic Kennedy, 1997, p. 6.

15 Nick Maurice, personal communication.

16 Peter Millar, 1996.

17 Ibid.

18 Mary Warnock, 1999, pp. 19–39.

19 Ibid., pp. 21–23.

20 Mary Warnock, An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Ethics, 1999.

21 Ibid., p. 89.

22 Jackson, 1998.

23 Mary Warnock, House of Lords, Hansard, June 2003.

24 Mary Warnock, ibid.

25 Mary Warnock and Elisabeth Macdonald, 2008.

26 Simone de Beauvoir, 1990, p. 78.

27 Mary Warnock and Elisabeth Macdonald, 2008, p. 83.

28 Onora O’Neill, The Lancet, 2008.

29 Steven Poole, The Guardian, 2009.

30 Julia Stone, Times Higher Education Supplement, 2008.

31 Elisabeth Sears, personal communication.

32 Jackie Macadam, 2008.

33 Nadine Dorries, quoted in Beckford, Telegraph, 2008.

34 Phyllis Bowman, quoted in Beckford, 2008.

35 Neil Hunt, quoted in Beckford, 2008.

36 Sarah Wootton, The Guardian, 29 September 2008.

37 Nancy Jecker, 2014.

38 June Andrews, 2008, p. 3.

39 Felix Warnock, personal communication.

40 Ray Tallis, personal communication.

41 Mary Warnock, unpublished lecture to the Society of Old Age, Rational Suicide (SOARS), 2010.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 House of Lords, Hansard, 12 December 2013.

49 Ibid.

50 House of Lords, 18 July 2014a.

51 Molly Meacher, personal communication.

52 Mary Warnock, 2010.

53 Ibid., p. 96.

54 Ibid., p. 100.

55 Ibid., p. 101.

56 Ibid., p. 108.

57 Ibid., p. 109.

58 Ibid., p. 112.

59 Ibid., p. 121.

60 Ibid., p. 123.

61 Mary Warnock, Interview with Laurie Taylor, BBC Radio 4, 10 September 2010.

62 Mary Warnock, ‘The Future of the Anglican Church’, unpublished, p. 2.

63 House of Lords, Hansard, 25 July 2013.

64 Mary Warnock, 2015, p. 35.

65 Ibid., p. 36.

66 Kitty Warnock, personal communication.

67 Molly Meacher, personal communication; Elaine Murphy, personal communication.

68 Elaine Murphy, personal communication.

69 Ibid.

70 Molly Meacher, personal communication.

71 House of Lords, Hansard, 2014b.

72 Mary Warnock, The Guardian, 2007.

73 Ibid.

74 Kitty Warnock, personal communication.

75 Sally Brampton, The Observer, 24 July 1983.

76 Ibid.

77 Ibid., p. 38.

78 Kitty Warnock, personal communication.

79 Norma Scott, personal communication.

80 Felix Warnock, personal communication.

81 Kitty Warnock, personal communication.

82 Ibid.; Felix Warnock, personal communication.

83 Kitty Warnock, personal communication.

84 Norma Scott, personal communication.

85 Kitty Warnock, personal communication.

86 Interview with Giles Fraser, Confessions, 9 February 2019.