6. What Are Schools For?

© 2021 Philip Graham, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0278.06

After nearly a decade at St. Hugh’s, Mary had begun to feel frustrated and bored with her life as an Oxford philosophy don, limited as it was by the demands of teaching a rather rigid curriculum and by the parochial concerns of college politics. She was not sure what new directions she could take but was at least certain that she should seize any opportunities which arose. In this spirit, she accepted, in 1956, the appointment as Editor of The Oxford Magazine,1 a weekly periodical for senior members of the university covering academic matters, book reviews and obituaries. She had served as a member of the editorial board, but now, as editor, she had to write a 1,000-word editorial every week in term time. She also found herself with a hands-on executive role, one of her duties being to set up the magazine at the printers. This experience served her well when she later embarked on what virtually amounted to a second career in freelance journalism. Over the years she wrote opinion pieces and book reviews for, among others, The Sunday Telegraph, The Telegraph, the Times Educational Supplement, The Times Higher Education Supplement, New Society, The Listener, The Oxford Quarterly Magazine, The New Republic, The London Review of Books, and The Glasgow Herald.2

In the post-war period The Oxford Magazine had moved away from its more literary origins but it still maintained a focus on poetry alongside its newer role as a forum for commentary and discussion of university affairs. J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis had both been contributors in the pre-war years as had Dorothy Sayers and a young W. H. Auden. It was perhaps this aspect of the magazine’s history which attracted the interest of the publisher, Robert Maxwell, who approached the new young editor with a takeover offer.3 To protect the magazine’s independence, Mary successfully resisted the proposal, but she was fascinated by the power of Maxwell’s personality and his drive to dominate. She got on well with Elisabeth, Maxwell’s wife and on discovering that she wanted to study for a degree in French arranged a place for her at St. Hugh’s.4

Around this time she joined the Board of Governors of Littlemore Grammar School which always co-opted a fellow of St. Hugh’s. In the early 1960s, there was a move to abolish the tripartite system set up in 1944 of grammar, secondary modern and technical schools, merging the three types into a single ‘comprehensive’ system. Littlemore was an ideal candidate for such rationalisation as it already shared its site with Northfield Secondary Modern. The two schools merged to become Oxford’s first comprehensive school. The moving spirit behind the merger was Jack Peers and the new school was named after him—the Peers School. He became a friend. Mary was swayed by the arguments for the comprehensive system and briefly became an advocate for them, though she was soon strongly opposing the abolition of grammar schools which, it seemed to her, provided a valuable pathway for the clever children of working-class parents to access higher education with all the subsequent career benefits that could offer.

Peers was Chairman of the Oxfordshire Education Authority and Mary soon found herself a member of that body too.5 She decided the teaching of music in the local authority would be her main focus. She had always been passionate about music and was determined that all children should have the opportunity to share her enthusiasm. The County Education Officer was willing to support her, but, a shy man, he could not cope at all or communicate with his eccentric Director of Music, Constance Pilkington. After Mary had tried and failed to act as a liaison between them, it was agreed that a Music sub-committee should be set up and she should chair it.6 Mary described Miss Pilkington, as she was known, as having brilliant, short white hair and bright blue eyes and wearing ‘impeccable pleated skirts and striped Macclesfield silk blouses and extremely elegant pointed brogue shoes.’7 When Mary asked her where she bought these shoes, she replied with withering scorn, mingled with embarrassment ‘They were made for me, of course.’ Miss Pilkington was hopeless at any sort of organisational development but had an unerring eye for unusual ability and would identify and encourage any really talented child musicians, setting many of them on the path to a professional career. Mary provided the organisational touch as well as advocacy for music within the local authority and soon music teaching began to flourish. There seemed to be limitless money for new premises and instruments. New school orchestras were encouraged throughout the county and a new county youth orchestra was launched with professional guest conductors. Notable amongst these were Muir Matheson, a successful composer and conductor of film music and a young Hungarian refugee, Laszlo Heltay, who went on to found the Brighton Festival Chorus and the chorus of the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields.8

Mary’s tentative explorations of opportunities outside university life took an unexpected turn following a chance meeting in Oxford’s Broad Street with Dame Lucy Sutherland. Dame Lucy was the Principal of Lady Margaret Hall and Chair of the Girls’ Public Day School Trust, the governing body responsible for a number of independent girls’ schools, including the Oxford High School (OHS). She told Mary that the head of this school was leaving and suggested that she should apply for the vacancy.9 The suggestion appealed to Mary more than Dame Lucy probably expected. Mary felt that she had been pigeonholed as a specialist in existentialism and she was being asked to supervise every postgraduate who showed an interest in the subject. She found some of these students ‘rather dim’ and teaching them unrewarding.10 ‘Each was more terrible than the last,’ she felt. They would hang around after the usual hour was over and, unlike undergraduates, expect to be supervised in the vacations. Mary couldn’t wait to get away. Her two daughters, Kitty and Fanny, who were at the High School, encouraged her to apply. Geoffrey thought she was mad to want to change her job but didn’t discourage her.11 As for her two sons, they bet her that if she were to apply she would not get the job. This probably only served to spur her on.

Given that her experience in school teaching was limited to six months spent as a school-leaver at the preparatory school, Rosehill, before she went up to Lady Margaret Hall, and two years at Sherborne Girls’ School as an assistant teacher while she was an undergraduate, it is indeed surprising that she was appointed. But in February 1966, appointed she was, and she took up her appointment the following September.12 The OHS was a direct grant school, receiving a grant from central government on condition that it admitted a certain number of children who otherwise would not have been able to afford the fees. The idea of the direct grant was to open such schools to the brightest poor children, but the majority of pupils were fee-paying, and therefore from middle-class families as, in fact, were many of the scholarship girls.13

Mary, by now in her early forties, made an immediate impact, not least by her style of dress. According to one ex-student, ‘she was always soberly but smartly dressed, yet with a sense of individuality […] She wore no nonsense pencil line skirts with a blouse or jumper, occasionally a suit with flat shoes. Her gown billowed as she strode on to the stage for morning assembly.’14 Another former student remembered her, perhaps on more informal occasions, as wearing ‘swirling purple capes, hats, big belts, once even an ethnic hammock’15 (whatever that may have been). It was recalled that ‘through her glasses she had a steady gaze. Her voice had a distinctive and rich timbre. She had clear diction with an unmistakeable North Oxford delivery of clear and considered thoughts and ideas. She was forthright, unfussy, calm and direct in her communications.’16 She was also outspoken in her enthusiasms and extremely energetic.

One of her early priorities was to improve the teaching of music in the school. When she arrived, there was a significant obstacle in the form of the Head of Music who had an unfortunate tendency to turn ‘people against the subject.’17 She had high standards but was ‘inflexible and snobbish.’ Mary’s view was that she really hated teaching and, given that she also seemed actively to dislike her pupils, sometimes throwing a board rubber at anyone who crossed her. The distressing consequence was that her pupils reciprocated with a dislike of her subject. Mary successfully persuaded her that her real talents lay in organisation, ‘that she was wasting her time in the lowly company of school mistresses’ and that she should change career and become a hospital administrator.18

Mary already had her eye on a successor, John Melvin, who was teaching in a preparatory school in Malvern. His initial appointment was part-time but when the position became vacant, he was appointed Director of Music. When Melvin arrived, he found that many of the students viewed music with positive animosity and regarded it as a subject not worthy of serious thought. As one ex-student put it, ‘great things were expected of him and great things he gave.’19 He found his position, one ex-student wrote ‘a true baptism of fire but quite soon he had established an orchestra which was gradually able to tackle the symphonic repertoire—an indication of both his leadership and the potential of musical ability there was in the school.’20 His other great aim was to involve as many girls as possible in musical activities and his warm, enthusiastic personality and humour soon resulted in a high-powered senior orchestra and large senior choir as well as two other orchestras, two choirs, a wind band and other smaller chamber groups. Mary helped him by ensuring that on entry to the school, all girls with musical talent were placed in the same entry form thus facilitating the timetabling of music. She also established the principle that girls were allowed to absent themselves from other lessons if they were required for rehearsals. Mary led by personal example. At one point the junior orchestra needed a French horn player. Mary bought a horn and began to learn to play it from scratch. She bribed the students in her Latin class to play the instrument too by offering a reward of Smarties to any of them who reached a higher standard than she did after a year.21 Mary’s enthusiasm for learning the horn did not last for long but her ‘can do’ approach and determination to lead by example clearly captured the imagination of the girls. At a more strategic level her most enduring legacy to music at the school was the planning and fundraising for a separate music block which was built and opened in 1975.22

Perhaps the trickiest task for new headteachers is deciding what to do about existing members of the staff they have inherited whom they find to be incompetent, obstructive or difficult to work with. As well as the Head of Music, whose redeployment is described above, there were two other teachers who fell into this category. One was a man whose poor teaching combined with unfortunate personal habits such as forgetting to do up his fly buttons. Mary convinced him he would be better off teaching at a boys’ school.23 The other was the teacher responsible for religious education. She was a figure of fun to many of her pupils who mocked her with pranks competing, for example, to see how many lunch boxes they could manage to drop out of the classroom window during a forty-minute lesson. This teacher saw Mary as an ungodly influence. When Mary broached the possibility of her leaving, the response was discouraging. ‘Mrs. Warnock,’ she replied, ‘As long as you are in the school, I feel it is my duty to stay.’ Mary eventually enticed her to leave by persuading a friendly don at one of the Oxford women’s colleges to offer her a place to read Theology.24

The rest of the staff viewed Mary with some reserve but were largely swept along by her enthusiasms. Initially she found staff meetings unnerving because no one volunteered any ideas or responded to hers. Yet almost before she was out of the room, she could hear discontented mutterings about proposals she had made. However, she was fortunate in having two deputy headteachers whom she found energetic, competent and delightful to work with.

One might have thought that, given the school’s academic catchment area, the students would all have had a good grounding in basic literacy and numeracy skills. This was far from the case. The prevailing philosophy in British primary schools at that time was that young children should learn reading and basic maths by a process of discovery, preferably through play. This child-centred approach had been developed in the 1920s and 1930s by Susan Isaacs, a psychologist and child psychoanalyst, whose books Intellectual Growth in Young Children (1930) and Social Development of Young Children (1933) were compulsory reading for teachers training to work in infant and primary schools.25 Mary had visited a number of primary schools during her time as a member of the Oxfordshire Education Authority and had come to believe that children were being short-changed by educational methods such as these. In one school in Thame she had seen ‘children […] being encouraged to count books by piling them up in lots of four along the walls. They had never heard of the four times table.’ For Mary, this meant every child had to be a ‘sort of Leibniz, an inventive mathematician. who could discover how to calculate without rules of thumb or rote learning.’26 Fortunately, her Head of Maths, Miss Jackson, took a similar view and was driven to despair by the students’ ignorance of their times tables. It became a common sight to see Miss Jackson ‘tramping around in the grounds, often in rain or snow, with one small girl, getting her to recite her tables or repeat formulae whether she understood them or not.’27

Unlike many headteachers, Mary took on some classroom teaching herself. All girls had to learn Latin and she allocated herself the lower of two streams containing the girls supposed to be less linguistically competent. Her aim, which she shared with her class, was that by the end of the year they would as a group be achieving better than the top stream. On Mary’s account they nearly always won. They learnt their conjugations by heart. Mary wrote later: ‘The sheer spirit of competition entered the souls of these children and they mopped up knowledge of tenses, conjugations, parts of speech, the agreement of adjectives with nouns.’ Mary drew on the teaching she had received at St. Swithun’s as well as her experience of teaching Latin to the Sherborne girls during the war, There was, of course, no nonsense about girls learning to conjugate Latin verbs by a process of discovery; indeed there was much chanting of Latin grammar of the ‘hic haec hoc’ variety. She again awarded her pupils prizes of packets of Smarties for success in their tests.28 Doubtless Mary’s own competitiveness was infectious.

|

|

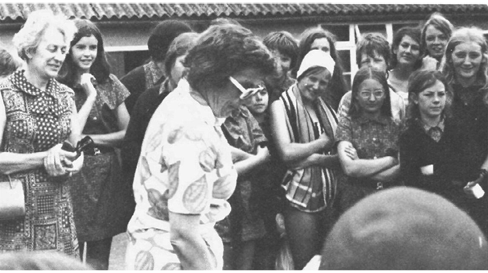

Fig. 5 Images of Mary during her time as headmistress (1966–72), from Oxford High School Magazine. Photographs provided by Oxford High School with the permission of Mary Warnock’s family, CC BY-NC.

As headmistress she had many more arduous duties, amongst which was dealing with parents. Mary categorised the parents, in a rather sweeping generalisation, as either pushy (the academic parents) or indifferent. But there was another group who ‘tended to be either rude or patronising or both.’29 Surprisingly these were often the parents of so-called scholarship girls rather than the fee-paying. Many parents were dissatisfied that the school was not following the new trend of learning through discovery rather than learning by rote but here Mary was implacable. She had little patience with parents like this and found them hard to deal with. Her attitude to parents may have come from a sense of identification with girls whose parents were not allowing them sufficient autonomy. In any event, it was unjust to many parents, and later lost her some allies.

In contrast, Mary was far more positive in her attitude to the older girls in the school. A new Sixth Form block was completed shortly after her arrival. Judy Hague, who was a pupil throughout Mary’s tenure as headmistress, recalls

the Sixth Form block was an important step as it gave generations of sixth formers a place to study and socialize: a half-way house between school and university. There was a common room, library and study area and a kitchen. It was the sixth formers’ domain, staff had to be invited in. On the study area walls hung art by Leonid Pasternak, father of Boris, which inspired me as I began to learn Russian. To aid the transition to life after school, sixth formers were allowed to wear their own clothes rather than school uniform.30

Under Mary’s leadership, the prefect system and position of Head Girl were abolished. Instead, older girls volunteered to be ‘part of a changing group who ran the school and ran the School Council.’ She regularly had tea with this group and any other member of the sixth form who wanted to attend ‘and these teas went on until I had to throw people out to go home to get the supper.’31 Every aspect of the school was discussed; the curriculum, the narrowness of the A level syllabus, what to do about drugs and other less important disciplinary matters. At times, Mary wrote later, ‘I felt myself in danger of discussing things more freely with the sixth form than with staff.’32

The mid- and late 1960s coincided with the rise of hippy culture in Britain. Mary herself, like most of the school parents, felt that the use of cannabis was by far the most worrying feature of the societal changes that were occurring at this time. It was widespread. For example, nearly all the 400.000 people, among them a significant number of sixth-formers who attended The Isle of Wight Music Festival held in August 1970, smoked cannabis. As a university town, with large numbers of young people in its population and on a drug circuit stretching from Birmingham to Southampton, Oxford was an epicentre of cannabis usage.33 Thus, the girls at OHS were exposed to a culture in which the use of cannabis was both normalised and regarded as adventurous and exciting. The main worry, which Mary shared with parents, was that cannabis use might lead to experiments with more dangerous drugs, particularly heroin. Many parents would have known that the issue of drugs had arisen in Mary’s own family. As we have seen, in 1971, she was asked to remove her younger son James from Winchester College. Although no reason was articulated, she and Geoffrey were given the misleading impression that the main problem was drugs in some form. James was friends with a number of OHS girls, so his expulsion was widely known about.34

Another challenge arose from the fact that the contraceptive pill had come on the market in the early 1960s and was widely available when Mary became headmistress of OHS. Now that it was becoming so safe and easy to prevent pregnancy, the trend towards earlier intercourse, which was already underway, accelerated. The average age of first intercourse for women fell from twenty for women born in the late 1940s, to eighteen for those born in the mid-1960s.35 Many more girls were becoming sexually active for the first time before the age of 18, something that would have been distinctly less common in their parents’ generation and even less so when Mary had been an adolescent. This raised generational anxieties among parents and staff who were dealing with these issues for the first time and who were uncertain how to respond.36

There was also the question of clothes. The Upper-Sixth had been allowed to abandon wearing a uniform before Mary arrived and it was hard to resist the pressure from the Lower-Sixth to follow. Dress was a topic always raised at governors’ meetings. Governors thought that the girls in the top forms presented an appalling spectacle and Mary could not but agree. On her description, ‘their hair was lank and drooped in curtains across their faces. Out of doors they wore blankets with a hole through which their heads appeared. They seldom wore shoes.’ In Assembly one day she told them the school was the opposite of a Mosque: the rule was that you had to put on your shoes when you entered it. The girls often wore ‘exceptionally smelly Afghan coats, the dirty-white uncured leather revealing the fur of the animal through the seams. Their skirts were little frills, barely concealing their knickers, and over these, ridiculously, they often had much-prized maxicoats’ falling to the ground.37 But having said they need not wear uniform, Mary thought it would be counter-productive to try to specify what was acceptable clothing. Gradually through persuasion and common-sense, most of the girls settled ‘for a kind of cleanish voluntary uniform of trousers and floppy men’s sweaters, with no shirts under them,’38 though the curtains of hair remained.

Before they made their choices of A level subjects, all students had to go and see Mary to discuss them. Judy Hague described her own interview:

I was apprehensive about the interview as I wanted to study three languages and did not know how the school/Mrs Warnock would view this. I knew I wanted to pursue my love of languages and literature. I had taken my French O level one year early and was already studying German. Having passed my French O level, I took up the opportunity to begin Russian. I was clear where my path lay, I wanted to study languages at university. No-one in my family, at that stage, had attended university. I tentatively asked Mrs Warnock if it was acceptable to take three modern languages. She agreed and I was relieved. Even more tentatively, I asked if I should be aiming high and thinking of applying for Oxford. She fixed me with a steady, encouraging gaze and replied ‘absolutely’.39

This encouragement to aspire high was characteristic of Mary’s approach to students. Judy, who afterwards did indeed go to Oxford, writes

without her encouragement and the high standards of education at the High School, I would not have had the courage to step out and aim for Oxford. My subsequent career was in the UK public sector, civil service and international development. Growing up in Oxford and attending the High School under Mrs Warnock’s leadership gave me a love of learning, a wide angled lens on the world, a cosmopolitan outlook, a passion for the arts, literature and languages and a sense I could make a difference.40

Mary took a more personal, continuing interest in girls who were suffering difficult family circumstances. One of these was Ruth Cigman. In the summer of 1967 Ruth had taken her O levels at another Oxford grammar school, Milham Ford. She was then, however, asked to leave as she was seen as naughty and rebellious, leading a group of girls who broke all the rules. Ruth’s parents had separated acrimoniously. Her mother had come from London to Oxford to study but had very little money. Needing to find another school for her daughter, she was put in touch with Mary who agreed to admit Ruth to the High School on a scholarship. Ruth wanted to study French, Russian and Music, but there was no Russian teacher. As there was one other girl who wanted to study Russian, Mary hired a Russian teacher for the two of them. Then Ruth didn’t get on with the music teacher whom Mary knew was difficult. Mary arranged for her to have lessons in her home with her own son, Felix, who was also studying music from home, following his early departure from Winchester at the age of sixteen. Ruth had a difficult home life, caught between warring parents. She became anorexic and was referred to the Warneford, Oxford’s mental hospital where she was given no psychotherapy but prescribed medication she didn’t take. To reduce the pressure on her, Mary suggested she gave up French and this seemed to relax the situation. Subsequently, Ruth became an academic philosopher of education attributing her career to Mary’s influence. She later commissioned Mary’s so-called U-turn Special Educational Needs: A New Look (2005, see Chapter Seven) and worked on several further writing projects with her.41

Jane Wardle was another pupil Mary took under her wing. Jane’s parents were unable to provide a stable home for her. Her father, portrait painter Peter Wardle, spent much of the year in Portugal. Her mother suffered from a chronic mental illness and spent long periods in mental hospitals. Jane and her two brothers were moved from pillar to post during their childhood, even spending some time in children’s homes. She attended thirteen different schools before presenting herself to the OHS at the age of sixteen. Typically, Mary took a particular interest in her and, on a number of occasions when the home situation broke down, while permanent solutions were sought, she found room for Jane in her own home. Jane won a place at St. Anne’s College, Oxford and went on to train as a clinical psychologist. As an academic, she made important and original contributions in cancer prevention and specialised in the psychological impact of cancer. She herself tragically died of cancer in 2015, not long after her appointment as Professor of Clinical Psychology at University College, London.42

While Mary was immersed in the administration and leadership of the High School, Geoffrey’s academic career was also moving in an administrative direction. Having been Senior Tutor at Magdalen for many years he had been narrowly defeated (by a single vote) in the 1968 election for president of that college, but three years later he was appointed Principal of Hertford College. This was clearly going to be a challenge: the college was achieving poor academic results, was in financial difficulties and the buildings were in a state of disrepair. After a short period of time, Mary decided that she could not continue as headmistress of the High School while also providing the level of support she felt Geoffrey needed.43

There was a second, more complicated reason for her departure: she was becoming increasingly troubled that the direct grant arrangement was under threat. The High School would either have to become fully independent or it would need to merge into the state system and become comprehensive, and neither option was especially palatable to Mary. She felt that the abolition of grammar schools would disadvantage the brightest pupils from the poorest backgrounds. Their access to fee-paying schools would be curtailed, condemning them to remain in the comprehensive state schools which, she thought, would be less academically aspirational. When the High School’s governors took the decision to become independent, Mary did what she could to mitigate the damage (as she saw it) by arranging with the headmaster of the local comprehensive, Cherwell School, for some of their sixth formers to attend the OHS for specific subjects.44 But there was no turning back the tide and the direct grant system was duly abolished in 1976.

Mary left the High School in the summer of 1972. Despite her disagreements over education policy, she did not find leaving easy. Many years later, when she was in her late seventies, her daughter Maria, who was then Director of Art at Dulwich College, London, arranged for her to spend a morning at the school, taking two assemblies and then teaching philosophy to various classes of different ages. Mary wrote of this experience: ‘I had forgotten the excitement of teaching a class of perhaps 24 children, all keen to contribute, all eager to absorb new ideas, all articulate and confident. I ended my morning exhausted but exhilarated, thinking “if I had my life again, this and only this is what I would do. Who knows?”’45

In truth, Mary knew that assisting Geoffrey in his duties would not amount to a full-time occupation but she did not want to go back to university teaching. Fortunately for her, Lady Margaret Hall was advertising a research fellowship and, although she was more senior than might have been expected for an award of this sort, she applied and was appointed to it. This gave her the time to write her next philosophical work, Imagination, published in 1976.46

She was also able to contribute to the public debates which were just then beginning on the future direction of education in British schools. These were given a strong impetus by a speech delivered by James Callaghan, then the newly appointed Prime Minister, at Nuffield College, Oxford in October 1976. Callaghan had previously taken little or no interest in educational issues and this speech was, in fact, written by his Senior Policy Adviser, Bernard (later Lord) Donoughue.47 Much of the public controversy around state secondary education was still centred around the contentious issue of the abolition of grammar schools, but Donoughue, who had four children being educated in the state sector, pointed out that what parents were really worried about was that their children should be protected from bullying and intimidation and that basic standards in educational skills and discipline should be ensured. In a deplorable number of schools, he thought, this was not happening. In a note to the Prime Minister, he wrote ‘This is surely an appropriate time to restate the best of the traditional and permanent values—to do with excellence, quality and actually acquiring mental and manual skills; and not only acquiring these qualities but also learning to respect them.’48 Callaghan’s speech echoed these sentiments and concluded with a call for a Great Debate on education. The teaching unions and Her Majesty’s Inspectorate were predictably incensed at this political incursion into what they saw as their exclusive territory. The civil servants at the Department for Education and Science were also unenthusiastic and produced a bland Green Paper barely responding to the issues raised in the Prime Minister’s speech.49 But Callaghan had prompted a debate which was to continue for some years both regionally and nationally, and Mary contributed to it.

First she collaborated with an education journalist, Ian Devlin, in writing a book What Must We Teach (1977).50 Devlin attended all the regional conferences that followed the Prime Minister’s speech and interviewed large numbers of teachers, parents, children and business leaders about their views. This collaboration with Devlin was the first of a number of books, public lectures and articles in magazines in which she expressed opinions on many aspects of education in schools. Her views were partly an expression of her own experience as a pupil but had been developed most substantially in the various teaching roles and institutions she had been involved in. In fact, her own education, as we have seen, was unusual: she did not go to school until she was nine and so had no personal experience of infant or state primary schooling. From nine to sixteen she attended an independent school with a particularly strong emphasis on the teaching of moral behaviour as the highest purpose of secondary education (at least for girls). She then moved, for her sixth form years to another private secondary school with more rigorous academic teaching. It was as a university teacher that she began to gain a wider experience: her undergraduate pupils came from a range of different secondary schools, so she was able to see for herself the skill levels and diverse value systems which such schools had taught. Above all, though, it was her experience as headmistress of the Oxford High School which had shaped her opinions on educational matters. Another formative experience, on a strategic and policy-making level, was her chairmanship between 1974 and 1978 of a government committee on the education of children with special educational needs (see Chapter Seven). She had not previously worked in special education, but she visited dozens of schools for such children both at home and abroad. Any gaps in her first-hand experience in education were compensated for by her professional background in philosophy; she had learned always to rely on evidence rather than opinion and, especially, to subject received wisdom to the closest scrutiny.

Mary continued to take an interest in education for the rest of her life. Over a period of forty years she wrote on a wide variety of educational matters. In that time there was a number of reforming Ministers for Education and Prime Ministers, notably Kenneth Baker, Tony Blair and Michael Gove, and some major changes to the educational system, particularly the introduction of the National Curriculum as well as some significant changes in teacher training. For the most part, Mary’s views remained consistent, but consideration of her published work needs to take account of the changing context in which she was writing.

She was never afraid to tackle the really big questions relating to education, so it is not surprising that she wrote extensively on the fundamental question—what was education for? In Schools of Thought, published in 1977, she proposes that education should be judged on whether it improves the life of the pupil in the future.51 This is an arguable proposition for surely one’s time at school is a part of life, not just a preparation for life, but Mary saw the preparation of children for the future as the main purpose of schooling. In order to decide whether an individual’s life has been changed for the better by education, one needs to be clear about what we mean by a ‘good’ life and she examines three criteria: virtue, work and imagination.52

Mary draws on the work of three philosophers, Aristotle, Kant and Hume, to suggest that to be judged virtuous or ‘good’ an individual must behave ‘truthfully, loyally, bravely, kindly and fairly.’53 When teachers consider the ways in which they can encourage ‘good’ behaviour, they should think beyond mere conformity to school rules. Some rules are clearly necessary, but school rules are largely ‘specific regulations with regard to such things as the marking of clothes, the production of explanatory notes in case of absence, the seeking of permission to leave the school grounds during the day and other such matters.’54 Some rules are clearly necessary to ensure the safety and wellbeing of pupils, but ‘so-called moral rules are utterly different […] in the case of morals, what is wanted is essentially a certain attitude, specifically an attitude towards other people.’ This distinction, between behaviour determined by narrow rules and behaviour governed by sympathy for and consideration of others,55 was an issue she was to return to several times.

At the time Mary was writing some moral philosophers were advancing the view that being moral was primarily a matter of making the right decisions. There were correct moral principles which, if followed, would inevitably lead to moral behaviour. As Mary put it, this view claimed that ‘the knowledge in question is knowledge of how to make rational and defensible decisions.’56 If this were the case, then morality could be taught, like arithmetic. Mary profoundly disagreed with this rationalist view of morality. According to her, while mathematics is an abstract subject that can be taught in the classroom, ‘there is no such thing as “doing morality”, only behaving well or badly, and behaviour needs real contexts, not merely exemplary ones.’57 The most effective way for children to learn morality in school is for them to see their teachers behaving well themselves. ‘A teacher can be fair or unfair, honest or dishonest (pretending to knowledge he hasn’t got, for instance), kind or cruel, forgiving or relentless, generous or mean.’58 These kinds of qualities allow a teacher when dealing with children’s conduct, to be unequivocal in condemning certain types of behaviour such as claiming to have finished work when it hasn’t been or taking the belongings of another child, and praising other behaviour, such as being helpful or generous.

Schools of Thought had a mixed reception in philosophical and educational journals. Karen Hanson agreed with Mary that we should all bear more responsibility for our educational institutions. She finds the book ‘a passionate and intelligent plea to take up that responsibility and a helpful and interesting aid in the task.’59 In contrast, Richard Peters, whose ideas are criticised in the book, though he does not mention this, was largely dismissive of the arguments Mary put forward, regarding it as patchy and poorly researched with a misleading title.60 An American reviewer was disappointed by the absence of any mention of the potentially destructive influence of schools and the neglect of the psychological and political factors that bear on the problem of inequalities.61

Mary expanded much later on some of her views on the teaching of moral behaviour in a sermon, titled Education and Values, delivered in February 1995 in the University Church in Oxford.62 Her views as expressed in this sermon are not far from those espoused by her High Anglican school, St. Swithun’s, sixty years earlier (although without the emphasis on guilt and remorse). Children have to learn, she claimed, ‘that they have such natural passions, that they may be led by them into doing what they immediately want, rather than what they ought to do; that is to say they can be tempted.’63 According to Aristotle and Christian teaching, overcoming temptation is powerful in contributing to a positive self-image. In contrast, determinism, the belief that one is fated to behave in the way one does, undermines self-belief. Determinism, she wrote, ‘is the most hopeless philosophy if taken seriously. It removes all will to fight, whether for intellectual or moral improvement.’64 In her sermon she quotes Bishop Joseph Butler who, in 1726 argued there were two steady principles in human behaviour: benevolence and what he called ‘cool self-love.’ He was convinced that humans do care for other people, it was part of their nature to do so. But they should also care for their long-term self-interest, realising coolly that it is contrary to their own interests to behave badly, to let people down, to bully them, to prove themselves too greedy or ambitious.’65

The school, Mary wrote, is an important, perhaps the most important, place for children to learn values, including the value of behaving well. But other values were taught in school. For example, for many children, ‘it may be the only place where aesthetic values can be experienced and discussed.’66 A powerful medium for teaching morality, particularly to young children, is, Mary believed, the telling of stories with strong moral relevance to their own experience. By way of counter-example, she did not believe that teaching about cutting down rain forests or over-fishing, reprehensible though such activities undoubtedly are, would do much to improve children’s moral behaviour—these issues were too remote from children’s everyday lives. Instead, the discussion of stories that raised moral problems about children like themselves would be far more effective.

More broadly, Mary sensed that teachers found it difficult to teach moral values. ‘Either they say that it is a matter for the family, or, more specifically, they say that of course they are prepared to keep decent order in the classroom and playground, but they raise the question, who are they to dictate morality to their pupils?’67 Mary thought this reticence arose from moral relativism, a mistaken deference to multiculturalism, when there were ‘common elements in humanity […] the preferences, likes and dislikes, loves and hates, which all humans share.’68 These universal human values must be taught. It followed that schools should not base their teaching of such values on any particular set of religious, including Christian beliefs. On the other hand, there are some kinds of values which are not universal, such as sexual mores for example, and in these cases, Mary recognised a valid place for instruction according to religion if this accorded with the ethos of the particular school.

The second ingredient of a good life for which school should prepare children was work, which included practical skills training as well as what might be described as a ‘work ethic.’ ‘Children should learn at school what will help them to work for the rest of their lives,’ she wrote in Schools of Thought, although she made it clear this should dictate only part of the curriculum.69 She realised, too, that there is hostility in some circles to the idea that ‘one should teach children with an eye to what they will do, how they will work, when they leave school.’ This might suggest working-class children should only be prepared for working-class jobs. Preparing children for work does not mean preparing them for particular types of work; they should be prepared for a wide range of work situations. Mary accepted that some work is by its nature boring but ‘even where a job is bad in all kinds of ways, it is better to have it than not, and probably better to work hard at it than less hard.’ School is a place where one learns that it may be necessary to work really hard, overcoming boredom to achieve a worthwhile academic goal.70 She noted that most people find hard work surprisingly enjoyable, and that money earned is better than money ‘handed out.’ But schools, in determining what they should teach, should listen to what the outside world is demanding.71 This does not, as is sometimes implied, diminish the subject in question. ‘To know that arithmetic will be useful to you later does not mysteriously reduce the value of learning it or render it impure.’72

Mary concludes the section on work with a list of subjects that children should be taught.73 She begins with reading and writing and mathematics, especially arithmetic, to a standard of competence. The pupil will need to gain understanding of what adult society is and this will lead, depending on interests and ability, to a branching out into economics, geography, history and sociology, together with at least one foreign language. The pupil must also have a certain understanding, part practical, part theoretical, of the physical sciences and technology.74 Looking back at Mary’s list it may nowadays seem uncontroversial, even banal, but her point was that these were subjects which all schools should teach. Of course, they would also be expected to add numerous other subjects in response to demand from their pupils.

Finally, after discussing virtue and work as components of the good life for which schools should prepare children, Mary considers the third and, in her view equally important component—imagination. Imagination, or the capacity for ‘image-making,’ is essential for the construction of memories of the past and visualisations of the future: ‘Educating a child’s imagination, then, is partly educating his reflective capacity, partly his perceptive capacity; it may or may not lead to creativity; but it will certainly lead to his inhabiting a world more interesting and understood, less boring than if he had not been so educated.’75 Of the types of educational activity that stimulate the imagination, she considers the vital importance of play in younger children who, as they grow older, begin to find in work the fun they enjoyed in play. Indeed, a recurring theme in Mary’s writings on education was that one of the many purposes of education should be ‘pleasure.’ To increase the chances of enjoyment, the curriculum should allow the child to choose some of the subjects studied. This would reduce the possibility of boredom. She believed also that a pupil’s imagination would be more stimulated by specialisation in some subjects than by learning ‘a little bit of everything.’

Mary very much believed in the vital place of the arts as part of every pupil’s education, but she rejects the idea that offering students endless opportunities for self-expression is the only or even the best way to educate the imagination. Nor should art education be seen as therapy for which most children have no need. Such an approach might result in children missing out on the appreciation of great art. ‘While teachers are flogging their pupils into original compositions, may not masterpieces of music or painting or literature go unobserved […]?’76 If Mary was sceptical of the excessive value sometimes attached to ‘self-expression,’ especially in music, she was clear that time and space should be available for ‘solitary reflection’ and for contemplation of the beauty of the natural world, and that such opportunities were often undervalued. Of course it is difficult for schools to find time when such reflectiveness can occur, but teachers should provide moments when the child’s mind can ‘wander, for him to think and feel as he likes.’77 Mary was writing this nearly fifty years ago but it seems relevant in the twenty-first century when the ‘crowding out’ of solitude and reflection by children’s constant exposure to screen-based activities such as television and video games, is a source of growing anxiety amongst present-day parents and educationalists.

While Mary stopped short of advocating a national curriculum as a legal requirement, in What Must We Teach she strongly encouraged the then Secretary of State for Education (Shirley Williams) to ‘intervene now to restore a sense of direction to teaching in schools which is so badly lacking.’78 She should, through the national inspectorate and local advisers, ‘issue positive guidelines by altering the examination system, by the use of specific grants to encourage the teaching of compulsory subjects.’79 In fact, the Secretary of State did nothing, and it was to be a further eleven years before a reforming Conservative minister, Kenneth Baker, introduced a compulsory national curriculum.80

The political debate around Baker’s Education Reform Bill 1988 spurred Mary to make a further significant contribution. Except in the field of special needs education, she did not intervene in the debates on the Bill in the House of Lords, but she wrote a book, A Common Policy for Education (1988), in which she discusses the issues raised in the Bill. The book was greeted in the press in rather sensational terms, described by the Morning Star as a ‘new broadside for Baker—the latest missile to be fired is by a formidable educationalist’ and by the Financial Times as containing ‘a string of proposals of breath-taking boldness,’81 but in truth it is no more than a measured contribution to the debate and contains proposals that, had he read them, would have been largely acceptable to Baker. A review in The Spectator was more accurate, describing the book as ‘one of the most lucid contributions to the “great debate”. It merits the widest possible readership.’82 Mary agrees with Baker, against the views of many teachers, that competition is necessary in education, provided it is fair competition with all students given a fair chance of success, and she also recognises the inherent risks in the imposition of a centralised and paternalistic curriculum. But, she claims, paternalism that works for the common good is by no means necessarily harmful.83

Despite the dangers of over-rigid centralisation, Mary was by now clearly in favour of a national curriculum, but she was understandably concerned about what it would contain. Her greatest concern, just as it had been a decade earlier, was that a prescriptive curriculum would discourage the development of the imagination, which should not be seen as an optional extra but as an essential part of all levels of education,.84 She also draws an interesting and important distinction in the teaching of English, between the ‘two great arms of the educational system.’85 Students must learn the ‘practical’ skills such as how to construct a letter, write grammatically and spell correctly. They should also, if possible (and it will not be possible for all students) study English literature, a ‘theoretical’ subject. The curriculum and the examination system must give equal weight to both arms. This distinction between the practical and the theoretical holds for all the humanities as well as for the sciences and mathematics. In her view, the ‘theoretical’ should become more philosophical and more critical than it is at present.86

In A Common Policy for Education, Mary wrote for the first time on the teaching profession itself, its status and training programmes. She had already spoken on this, in February 1985, in the BBC’s Richard Dimbleby Lecture, titled Teacher, Teach Thyself,87 but in her book, she was able to give more considered views. Her lecture had been criticised for containing some patronising attitudes to parents, whom she categorised as either pushy or indifferent, but the book recognised the fundamental importance of a more collaborative relationship between parent and teacher, a stance that had been taken up strongly in the Report on Children with Special Needs nearly ten years earlier.88 In A Common Policy for Education she discusses the low standing of teachers among the general population. The stereotypical teacher had for long been viewed either as a frustrated spinster or as a man who has failed at some other profession, but she felt there were two further reasons why teachers had fallen even lower in public estimation. A long teachers’ strike had just ended. The strike appeared to have achieved little in terms of teachers’ demands but had undoubtedly been highly exasperating for hard-pressed parents unable to send their children to school. The reluctance of teachers to return to the classroom had, in Mary’s view, damaged the standing of the teaching profession. Indeed, it raised the very question that Mary had addressed in her Dimbleby Lecture: can we speak at all of teaching being a ‘profession’ when one of the essential characteristics of ‘professionals’ is that they do not withdraw their labour. And her second point was related: she described what she saw as the increasing politicisation of teachers. Inevitably, when teachers discuss unfairness in society, they risk encroaching on political territory, but, to the best of their ability, they should avoid taking sides where political controversy exists.89 Once again Mary was highlighting an issue which remains relevant today.

While the politics of teachers, and of teaching, are matters of general concern for Mary, she sees teaching as primarily a practical task and considers in some detail what teachers need to be taught to do their job effectively. There are some purely practical skills, such as, for example, record-keeping, tracking pupils’ progress, marking examinations and marking homework within a reasonable time. Then there are communication skills which may be instinctive in some, but which can also be learned. Amongst these she highlights learning how to respond to abuse from pupils and encouraging parental co-operation. A teacher’s relationship with parents is distinguished from that of social workers who, seeing parents as products of their environment, are careful to avoid implying they ‘could do better.’ For Mary, ‘could do better’ is a necessary part of a good teacher’s approach to children, and they need to convey this to parents. Teachers should strive to avoid preconceptions, based on social background, about their students’ potential. Instead, they should nurture the individuality in each pupil and encourage parents to be surprised by what their children can achieve. Lastly, skills of a more personal kind are needed for the trainee to learn how to maintain control over a classroom of children, indeed, to exercise power.90 This requires self-awareness and self-monitoring to avoid, for example, favouritism or signs of gender or racial preference. Nurturing individuality is vital, in Mary’s view, and she returns to this theme again when reminding teachers to be constantly aware of the differences between students in their level of understanding and to tailor their approach accordingly.91

To emphasise the practical skills required to teach well and to develop the concept of teaching as a profession of equal status with other professions, Mary proposed the establishment of ‘teaching schools,’ analogous to the familiar teaching hospitals. Mary was ahead of her time with this idea, and it would be another twenty years before the first ‘teaching school’ was established in 2010. Also ahead of her time, although this was an idea which was already part of the public discourse on teacher training, she proposed a General Teaching Council (GTC) set up by teachers themselves to achieve common professional standards.92 Such a council was indeed established in 2000 but was not a success, surviving only until 2012. It was replaced by a less bureaucratic Teaching Regulation Agency, which does not have the powers Mary envisaged for the GTC. Finally, Mary argued for an improved career structure and greatly enhanced salaries, especially for headteachers. ‘The top salary they can reach is ridiculously low compared with that of other professions […] It is not satisfactory if the only people willing to embark on teaching as a career are […] those who feel themselves incapable of making a living in the competitive world of commerce/industry or the City.’93 To some degree at least this has been achieved, but only in the early years of the twenty-first century when the salaries of headteachers were significantly increased and when, in order to attract the brightest graduates, the fast track Teach First scheme was introduced.

So how can we assess Mary Warnock’s contribution to secondary education in the last half of the twentieth century? First, she was an inspirational headmistress of the Oxford High School who made a significant impact on many of those who attended while she was in post. Nationally, her thoughtful contributions to the education debate that ran into the early years of the twenty-first century were marked by great common sense and a consistent philosophy. Over this period, education in Britain changed in two very significant ways. The responsibility for the running of schools was increasingly removed from local authorities with central government taking a much larger role. On this matter, Mary had very little to say in public though her unpublished writing reveals she was largely in favour. There was also very significant centralisation of teaching itself through the mechanism of the central control of the curriculum. This had begun with the debate initiated by James Callaghan in 1976 but was only activated by Kenneth Baker in the late 1980s and then carried even further by Michael Gove in the 2010 coalition administration. In the early years of the reforms, she had been greatly in favour of the emphasis on standards in literacy and numeracy and on the retention of a strong academic focus in secondary education. But her advocacy of a broader view of the purposes of education went largely unheeded. Instead, just as she had feared, the curriculum was increasingly determined by the content of examinations which seemingly had little relevance to adult life. Mary was disappointed, to put it mildly, that the increased emphasis on the measurement of academic achievement through testing and exams led to the neglect of the arts and humanities and of the imagination itself, all of which were being relentlessly squeezed from the system. Hopefully, as the twenty-first century unfolds, more attention will be given to the logic and sound common sense of her views.

There was just one area of great educational significance which Mary discussed not at all. The success of a school depends very largely on two factors—first, the quality of classroom teaching, on which she had much to say, and second, the quality of leadership, on which she said nothing.94 Yet leadership was the quality in which Mary perhaps most excelled. As headmistress of the Oxford High School, she provided a model of academic excellence, discipline, fairness and compassion. In her subsequent writing on education in schools, she provided unique intellectual leadership, combining practical experience with the clarity of thought of a trained philosopher, this combination making her uniquely qualified to contribute to the debate.

.png)

Fig. 6 Portrait of Mary Warnock, unknown photographer (1977), provided by the Warnock family, CC BY-NC.

1 Unpublished autobiography, UA, 7, p. 1.

2 Girton Archive, 1/16/2/7.

3 UA, 7, pp. 3–4.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., p. 6.

6 Ibid., p. 7.

7 Ibid., p. 8.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid., p. 10.

10 Ibid., p. 11.

11 Ibid.

12 OHSGA Archive, Oxford High School for Girls Archive, http://oxfordhighschoolforgirls.daisy.websds.net/.

13 UA, 7, p. 13.

14 Judy Hague, personal communication.

15 Ibid., Janet Jones.

16 Judy Hague, personal communication.

17 UA, 7, p. 19.

18 Ibid.

19 OHSGA, John Melvin.

20 Ibid.

21 UA, 7, pp. 18–19.

22 OHSGA.

23 UA, 7, p. 23.

24 Ibid.

25 Graham, 2009.

26 UA, 7, p. 16.

27 Ibid., p. 15.

28 Ibid., p. 18.

29 Ibid., p. 13.

30 Judy Hague, personal communication.

31 UA, 7, p. 22.

32 Ibid.

33 Warnock, OHSGA.

34 Ibid.

35 Wellings et al., p. 41.

36 Warnock, OHSGA.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Judy Hague, personal communication.

40 Ibid.

41 Ruth Cigman, personal communication.

42 Andrew Steptoe, personal communication.

43 Warnock, 2000, p. 24.

44 OHSGA.

45 UA, 5, p. 15.

46 Warnock, 1976.

47 Donoughue, 2003.

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.

50 Devlin and Warnock, 1977.

51 Warnock, 1977.

52 Warnock, 1977, p. 129.

53 Ibid., p. 132.

54 Ibid., p. 137.

55 Ibid., p. 138.

56 Ibid., p. 131.

57 Ibid., p. 132.

58 Ibid., p. 135.

59 Karen Hanson, p. 145.

60 Richard Peters, p. 115.

61 Joseph Novak, p. 85.

62 Warnock, University Sermon, 5 February 1995.

63 Ibid., p. 14.

64 Ibid., p. 15.

65 Ibid., p. 16.

66 Ibid., p. 1.

67 Ibid., p. 3.

68 Ibid., p. 8.

69 Warnock, 1977, p. 143.

70 Ibid., p. 144.

71 Ibid., p. 148.

72 Ibid.

73 Ibid., p. 150.

74 Ibid., pp. 150–151.

75 Ibid., p. 152.

76 Ibid., p. 160.

77 Ibid.

78 Devlin and Warnock, p. 154.

79 Ibid.

80 Baker, 1993, pp. 189–209.

81 Warnock, 1989.

82 Ibid.

83 Ibid., p. 176.

84 Ibid., pp. 37–38.

85 Ibid., p. 171.

86 Ibid., pp. 172–173.

87 Warnock, 1986.

88 Department of Education and Science, 1978, pp. 152–161.

89 Warnock, 1988, p. 112.

90 Ibid., pp. 117–118.

91 Ibid., p. 126.

92 Ibid., p. 132.

93 Ibid., p. 134.

94 Leithwood et al., 2006.