2. ‘How do we set straight our sacred city?’1

© 2022 William St Clair, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0279.02

Men of Athens. It is the proud boast of our city that we are governed not by kings nor by oligarchs, but by ourselves.2 And it is as free Athenians addressing free citizens that your Commissioners exercise our duty to speak usefully and plainly, without fear, flattery, or sophistry, and without resort to any of the rhetorical tricks that others employ to ensnare and corrupt the unwary.3 As the saying goes: [The reciter notes by a change in voice that he is quoting] ‘It is easy to praise the Athenians among the Athenians’.4 Weak minds, we all know, can be misled by the arts of persuasion, but your Commissioners will never bend the measuring rod that we ourselves must use.5 Men of Athens know the difference between words that are polished but unfair and those that may be rough on the surface but that tell the truth.6

So we give you our own words as plainly as you wish to see them.7 And we know that however good we are in word, without your goodwill, we will not be useful in deed.8

Today we discuss the refloating of our foundered city, a matter that is, for all of us [the reciter again notes by his tone of voice that a quotation follows] ‘above all time-consuming business’, as the poet sings.9 Our fortunes have been shaken, and now is the time to again set them straight.10 As your Commissioners, ours is a heavy burden, but, although we are as unworthy in our own judgement as we are in yours, we accept the duty to obey that our laws lay upon us all.11

In preparing our proposals, we have, in accordance with the ancient customs of our city, sought the advice of the god, and all that we say accords with the oracles of Delphi, that you can read if you wish.12 There may be a few here today who may have heard foolish stories that the gods take no interest in the affairs of men, but they are wrong.13 Sometimes the gods are careless.14 Since they know everything, they do not need the images that we dedicate to them nor the sacrifices that we make in their honour and of which we always give a share to the gods, but the more we show the sincere piety with which these gifts are offered, the greater the delight that the gods take in our gifts.15 We Athenians will always be dear to the gods and, as our poets sing, in time the gods bring everything to a conclusion, even if they are slow.16

We have listened to the spirit (‘daimon’) of our rivers, of our hills, of our winds, and to the whispers of our olive trees.17 We have journeyed over our land of Attica, to our towns, to our frontier forts, to our harbours, and to the rocky walls that defend us from robbers from the sea.18

But enough of woods and rocks.19 As the saying goes, for all matters that are dark, the teacher needs the light of evidence and of likelihood.20 Under the watchful eyes of the gods, we are able steadfastly to follow the course and capture: [quoting] ‘the pure light shining from afar’.21

In asking the Assembly to approve the plans, your Commissioners speak on behalf of the whole polis.22 As Homer teaches us [quotes] ‘two good men are better than one’, and, like Agamemnon, we too wish we had ten of such fellow councillors.23 And we speak especially for those citizens who are recovering from wounds or from sickness, who have been absent on campaign or working to secure the cities of our overseas kinsmen, or who have been on sea voyages bringing the fruits of other lands to our Attic shores.24 On the knowledge and wisdom of these men the greatness of Athens is built and just as a huntsman selects his dogs and horses for how eager they are in the chase and not for their lineage, so too good birth does not always make for useful men.25

We speak too for those with little education, such as those who pull the oars of our ships of war, those who steer and act as lookouts, those who build the ships, and others who work tirelessly for our city for pay.26

We do not speak at length of what is already known.27 Those who have served as commissioners already know more than we do. Others have participated in our deliberations since the plans were first proposed in shadowy outline (‘skiagraphia’) or have talked with the members of the Commission or our secretaries. It is difficult to say neither too little nor too much; and even moderation is apt not to give the impression of truthfulness.28

Tomorrow we, the people, (Assembly of the ‘Demos’) will decide what is best after we have all heard the reasoning (‘logos’) for our proposals. Every man who has the right to speak and he who speaks in respectful words will be listened to.29 But let each man recall that Athens wants to hear only from those who have something useful to contribute.30 Anyone who makes a disturbance will be handed over to the Scythians, and if he forfeits his daily payment for attendance, his family will go hungry.31 And let us remind ourselves too that, if you change the decisions already taken, you may feel the displeasure of those who have taken upon themselves and their heirs the responsibility for ensuring that the work is finished and that all the appropriate payments are made.32 When things go well, citizens cannot claim to share in the credit for our good judgment, and if they go wrong, we cannot blame the unexpected.33

Everyone who speaks will also reflect carefully whether his words are in accordance with our ancient laws and customs. Today we see the Areopagus at work, keeping us safe, day and night. [The reciter points to the hill]. If ever our laws and customs are polluted by misuse, or godlessness (‘asebeia’) they become like water stained with filth, poisonous and unfit to drink.34

As is the custom, we begin with our ancestors, who alone of the Hellenes arose from the land of Attica, and who have passed it on unconquered, from generation to generation, to the present day.35 When the gods divided the earth, Athena, who loves wisdom, and Hephaistos, who loves the arts of making, of whom we are the sons, fashioned our land of Attica to be a place whose very nature encourages good government and civic virtue (‘arete’).36

We have all heard our fathers speak of the never-to-be-forgotten year when Phainippides was archon [490 BCE] when alone of the cities in Hellas, our men of Marathon saved Hellas and Hellenism itself.37 Our immortal dead we awarded with special honours that, like their fame, can never perish.38 Others remember the year when Kalliades and then Xanthippos were archons [480/479 BCE] when the oriental barbarians invaded our land, treacherously captured our acropolis, destroyed our sacred buildings, killed those who stretched out their arms in supplication, and knocked down our family dedications with their savage hammers and axes. When Hellenes take possession of another Hellenic city and its holy places, we do not act like the barbarians but allow the rites and ceremonies to continue as far as is possible.39 But, not content with destruction, the hated orientals set fire to our holiest places and committed another crime against the gods. Our houses are burned to ashes, our life-giving wells are choked with our broken household possessions.40

Cast your eyes, men of Athens, on our sick old men and wounded youths spurting blood as their defenceless bodies are pierced by eastern spears. See our daughters to whom we entrusted our most sacred treasures, cling to our altars like ivy to an oak.41 Hear them shriek as they are raped and killed by monsters screeching their pitiless chants.42 Smell the blackening blood, swipe at the clouds of buzzing flies, tremble at the snarling dogs. Our daughters who have not yet been given to a husband shake their arms in vain at birds so glutted that they can no longer cry out their messages that tell our soothsayers what the future holds.43 Shudder at the impiety of monsters who deny the dead the ceremonies that they deserve that save them from the black night of oblivion.44

When your Commissioners first looked at our shining city on the hill of Cecrops, we saw death-dealing scorpions and serpents slithering on the paths along which our perfumed daughters used to dance and sing their joy-giving hymns. The city has already put to a stop to the burning of useless things and the dumping of dung.45 But your Commissioners share with you the shame of our young men, when at the ceremony at which they become our warriors, they see not the moment of victory but that of the unmerited defeat. We weep to see our best youths drinking in taverns, gambling with dice, and spending time with flute girls when they should be making new citizens with their wives at home. Some spend time with Lydians, Phrygians, Syrians, and others from the lands of the great king, whose hordes our fathers twice drove from our land, and whose foreign customs, unless they too are driven out, will dilute both their love of country and our native blood.46 It is not our custom that immigrants should set themselves above the autochthonous, that those who receive the benefits should think themselves superior to their benefactors, or that those who come as suppliants should lord it over those who have helped them.47

We heard Athenians who see a snake calling on a foreign god they call Sabazios.48 We see them cooling their wineskins in the ‘Nine Channels’ …. [A member of the audience shouts out an obscenity that raises a laugh. The reciter then addresses the interrupter] Will you tell me, you brute, where I can buy a stopped-up nose [laughter]. [The reciter resumes]. Camel dung is for your yokel theatres [more laughter].49 Let us remind ourselves of the law of Solon that requires that speakers must not be interrupted or shouted down.50 You are not at the Dionysia now.51

[The reciter resumes his formal style] Our beloved city, O men of Athens, is stretched out like a sacrificial black horned beast, bleeding, eviscerated, stinking, with nothing useful left but its skin.52 And we hear again the voice of Solon, the founder of our Athenian constitution, cry out in his immortal lament: ‘How my breast fills with sorrow when I see Ionia’s oldest land being done to death.’53

But why, you may ask, do we [changes tone to signify a quotation] ‘repeat the unspeakable’?54 For we also remember the day when as the oracle foretold, the women of Cape Colias roasted their barley on fires made from broken Persian oars.55 Our alliances with kindred cities fortify our land with walls of brass and steel.56 And now, every true Athenian is asking himself, what is to be done to make the ship of state fit to resume our journey and make our holy places live again in shining glory? Some say that we ought to build more warships, but as the poet tells us, the safety of a city does not depend upon its walls but upon its men.57 The success of a city does not lie in its armies and navies, but in the wisdom of its rulers.58

If the great king [spoken with a touch of contemptuous irony] and the unforgivable medizers were mad enough to try to invade our land again, we are ready.59 But in our city the flood of lawlessness and impiety cannot be held back by endlessly adding new laws to those that already fill our porches.60 For our forefathers in the time of Solon and Cleisthenes, who drove out the tyrants and gave the power back to the people, it was enough to ensure that our ancient customs were taught to the young and that those who broke them were punished and dishonoured.61

When we visit other lands, some possessed by other Hellenes, and others by the barbarians, we see the members of each household working every day to produce just enough for its own needs, keeping sheep and goats for cheese, meat, and wool, and picking fruits from their trees, but always at the mercy of Tyche, wondering whether the rains will come and if there will be enough to eat in the winter.62 We see wild men in the countryside afraid of their neighbours, carrying arms in case they are attacked when they are on land and afraid to venture on to the sea because of the sea-robbers.

It was because we are one people, united in our trust in the gods and in one another, that we Athenians were the first to go naked and now only carry arms when we are at war.63

As we look out to Brilessos, that until the days of our grandfathers only supported grazing goats, we see men at work harvesting the gifts of shining marble that the gods have planted in our land.64 All Hellas has seen the strength and beauty of our Athenian marble at Delphi, and we will sell our surpluses to other cities.65 Hard, stoney, and difficult to work though our land is, we win prizes in the competitions in the four great festivals. Our winners wet the cloaks of the spectators with our olive oil as they rush among them.66 [Shouts of approval]. Since the time of King Cranaos, son of Cekrops, we Athenians have been the ‘men of the rocks’.67 [Shouts of approval].

No enemy in ancient times tried to seize our land by war in hopes of expelling us and resettling our motherland with men of alien kin sent from their mother city, as Athenians do. And unlike other cities, Athens has never gone to war or exacted a sweet revenge except when our cause is just.68 We Athenians have, as we all learned in childhood, always remained in possession of the land from which we sprang and have been shaped and kept pure by its excellences as if by another mother and another nurse.69 Our land and our sea, from whom we are born, came to our aid as our kin when Darius in his arrogance (‘hubris’) had tasted the bitterness of defeat at immortal Marathon. See [the reciter assumes a solemn tone usually heard in the theatre or a formal oration] Amistres and Artaphrenes and Megabates, and Astaspes skilled in archery and horsemanship and Artembares, who fought from his chariot, and Masistres, and noble Imaeus, skilled with the bow, and Pharandaces, and Sosthanes, who urged on his doomed horses, and Susiscanes, and Pegastagon of Egyptian lineage, mighty Arsames, lord of sacred Memphis, and Ariomardus, governor of Egyptian Thebes, and the marsh-dwelling oarsmen. See those who held the cities of our kin in subjection redden our harbour with their noble blood.70

Today it becomes our duty to seek the truest causes both of the defeats and of our glorious victories. Your Commissioners had wished, men of Athens, to bring forward Hippocrates of Cos, skilled in the art of healing, as many can testify.71 He has sent us a written papyrus, part of a longer work, in which he sets out the most modern knowledge on how differences among peoples arise, and especially the differences that have arisen between the Ionians of Athens and those Ionian kinsmen who live overseas in the cities of Asia and the islands. We will not weary you with theogonies that are tiresome to the ear.72 But, as we all know, just as children owe a debt of mutual gratitude (‘charis’) to their parents and to their nurses, so too the men of today are bound to render to our fathers the honours which they have earned by their deeds.73

[The reciter reads aloud the following deposition that is written and spoken in the Ionic dialect: ‘With regard to the lack of spirit and of courage among the inhabitants, the chief reason why Asiatics are less warlike and more gentle in character than Europeans is the uniformity of the seasons, which show no violent changes either towards heat or towards cold, but are equable. For there occur no mental shocks nor violent physical change, which are more likely to steel the temper and impart to it a fierce passion than is a monotonous sameness. For it is changes of all things that rouse the temper of man and prevent its stagnation. For these reasons, I think, Asiatics are feeble. Their institutions are a contributory cause, the greater part of Asia being governed by kings. Now, where men are not their own masters and independent, but are ruled by despots, they do not seek to be practised in war but on not appearing warlike.’74

[The reciter resumes] We Athenians have always treated both our Ionian kin and those who have come home to live in our city as our own children whom we love and educate, and who in their turn from their earliest childhood must again learn how to honour the parents who have adopted them.75 And their minds and dispositions too will be improved as our city, that is their motherland, is restored to health by your wise decisions. The sons of Dorus like to say that they are the bravest of the Hellenes, but the sons of Ion know that we are the cleverest.76 [Laughter].77

In the times through which we have lived, the stories of our united city have been damaged and we need to straighten them too.78 Like the sacred buildings at Delphi built by others that are made from coarse local tufa with a covering of smooth imported Parian marble, they do not persuade our eyes and are easy to destroy.79 We need no songs that please only for the moment, and that will not bear the bright light of our Attic sun.80 The clear aether that the gods have given us has always made us able to see the distant horizons by land and sea.81 The air around enters us through our eyes, our noses, our mouths and other apertures of our bodies, subtly becoming part of the marrow of our bones, like an enchantment.82 Our superiority in the arts of peace and war we owe to our mother, the land, and to our sky, our winds, and our encircling sea.83

It will next be judged useful to remind ourselves of the choices with which the city is confronted. And just as in a trial of criminals and traitors, in which many of you have been jurymen, those who have not been fully informed cannot give the right verdict, so too in matters of policy, the city requires its lawgivers to understand the situation in its entirety.84 We have therefore decided to begin by setting forth the argument [‘logos’], for if we had neglected to make this clear, our speech would appear to many as curious and strange.85

In our walks outside the walls, we saw the dutiful storks who arrived here, as they do every spring, twenty-two days after our Flower Festival (‘Antherstia’) [7 March] which our slaves celebrate with us. Some say that it is our slaves, who do not benefit much from other festivals, who like them most, having few other pleasures in their daily lives.86 The storks have been faithfully repairing and rebuilding their nests, feeding their young, caring for their old, bathing the wounds of their injured kin in health-giving herbs, and sharing with us the benefits of living close to us in our houses.87 Our citizens too follow the unceasing ‘charis’ of parents to children and of children to parents, in which the storks have reached the perfection of their nature. [The reciter points to the nests that are always in sight even when the storks themselves have left for the winter].88

Our daughters are as dutiful as the birds. [Noises of approval].89 As we look up to the heavens through our matchlessly clear Athenian aether, we see the stars and the planets circling as in a dance, as our Ionian philosophers have explained.90 And we all recognize those who are feigning as easily as if they have a bell round their necks.91 When we hear the cries of the cranes [‘geranoi’] overhead, we know it is time to plough our land and to prepare for the winter rains.92 Some say the birds learned their extraordinary dance from seeing us dancing our own geranos.93 As we watch them fly over our land and sea, we see them formed into squadrons with the leader changing frequently, as in our democracy, but always maintaining their allotted place in the ranks.94

All who live here obey all the laws and customs, not only the ancient and the unwritten, but the newly enacted, that keep our city pure.95 Men are fitted by their nature to govern the polis, and women the household (‘oikos’).96 We will celebrate the tasks performed by our pure Athenian women, the best in all Hellas, and especially their faithfulness in performing their duty to produce useful Athenians.97 For, as we all know, for human beings (‘anthropoi’ ungendered), as for all other animals and living plants, it is only when the first shoots are cultivated properly that they develop towards their full potential of excellence.98 Euripides, son of Mnesarchus, tells us that he would rather fight in three battles than give birth to even one child. [Laughter]. And it is easy for him to set himself up as your adviser for he knows nothing about either. [Approving laughter, and a shout of ‘neither do you’].99 We offer a sketch of how what we all desire might be pictured. [The reciter passes round an outline as in Figure 2.1].

Figure 2.1. ‘The stages of womanhood’. Engraving from a painted vase in Naples.100

When we show mortals, we will not pick out the strongest or the fastest but show those that hold the mean position between opposites.101 And only those, whether male or female, who lead blameless lives such as fit them to be guests at the ceremonies of marriage and acceptance of children will be pictured.102

In the mornings and in evenings of the springtime, we hear the laments of the nightingales, always remembering, always returning, never conquered by the sharp-eyed hawks. Some say that women who have been wronged by their families are transformed into nightingales so that they will never be forgotten and in due time will enjoy a sweet revenge.103 But, on our walks, we also see the shameless and greedy kites whose arrival tells us that it is time to shear our sheep, but who snatch meat from the divine altars and the market stalls, who gobble the eggs and chicks of the other birds, and who even pick at our clothes for scraps to line their nests.104 Among the cities of the birds the kites are the Achaeans, but we are the storks.105 Our city is for Athenians, but it is also for our kin and our friends, always as welcoming as Delphi, Olympia, and Delos, as our birds, our birdcatchers, and our flocks of fatherless and cityless urchins know.106

Our famous hills and places show us our democracy at work.107 We are struck with awe as we look at the plain where Theseus saved the city from the bare-bosomed archers. Our eyes fill with tears when they meet the armour-makers on the nightingaled hill from where the child of the blind king of Thebes caught her first sight of our welcoming walls.108 [Here the reciter gestures to the Hill of Colonos] Oh how unfortunate was that mortal family when it was deserted by Tyche.109

So how, we now ask you to consider, can we best restore the ancient customs of our city? How can we cure its many illnesses?110 How do we help our friends and harm our enemies?111 How can we again be sure that our women again know that the best service they make to our city is to see that the household (oikos’) is well run, to look after the property indoors, and to obey their husbands.112 How can we strengthen all the duties of kinship.113

During the troubled times our city never ceased to pay due honours to the gods. While the danger persisted, we preserved and repaired as much as we could of our beloved city.114 We repaired our walls and many of the sacred buildings knocked down and burned by the barbarians, and we maintained our ancestral customs and ceremonies.115 It is the nature of our Attic olive trees to live well not only when the air is hot and when it is cold, but in the rain that wets and in the sun that dries.116 And, as we all know, nature does nothing in vain.117 As with our dogs, so with our trees, it takes time for them to become tame and give us their benefits, but even when they are forced to revert to their wild state, they return willingly to our households. When they are wounded, the gaps close.118 If our enemies cut them down, they bring forth new shoots. Like our city, the trees renew themselves as one generation follows another as they have always done. Their fruit, each in its shield, that give us oil for cooking our meat, fuel for our lamps, and relish for our bread, bring to our blessed land the alien fruits that are, by nature, unsuited to our land.119 It is not only our stinging and biting insects that our famous oil drives away but any enemy who sees our shining bodies [laughter].120 The trees that spring from our land are the greatest of the gifts that Athena has conferred on the city that has taken her name, and we will never cease to return her charis in word and in deed.121 And now is the time, men of Athens, for our city to yield new fruits of ‘arete’.122

Even those philosophers who wish to undermine the ancestral wisdom of our city are united in their belief that civic morality (‘arete’) can be taught, and that the first step towards learning the good is to unlearn the bad.123 Our young men are not like the stamped gold valuables that we keep in our acropolis, ready to be brought into use when needed, their nature unchanged.124 Some of you keep your slaves fettered to stop them running away.125 But other slaves have been so successfully educated into our Athenian laws and customs, written and unwritten, that they are trusted with our most precious possessions, and some take a part in the education of our children.

The time has come, the Assembly has already decided, to rebuild our city to make it fit not just for today and tomorrow but for all time.126 The tyrants, who only sought their own glory, were untrue to our ancient customs, and their sons, who accompanied the barbarous and cowardly Asiatics, will always be condemned as traitors by all right-thinking Athenians.127 We Athenians will continue pull down the images set up by other cities in their holy places as we have always done since we punished the cursed city of Troy, but never again will any enemy be able to do the same to us.128 We will ensure that any invader of our land, whether barbarian or Hellene, who looks at our Acropolis will know that he can never capture our holy places, and that he can never destroy or remove our idols, our memorials, or our tombs.129 They cannot take away what is most precious to us, our nature as Athenians.130 And we will always be able to guard and to keep safe the knowledge of who we are and what we hold in common with the best men and women of our past, on which the future well-being of our city depends.131

With our excellence in the arts of writing, in which our children are becoming ever more skilled, our city need no longer rely solely on our memories, refreshed by our festivals, and the stories that our land tells that the best people will always remember.132 And it is by bringing together the elements of Nature that our most marvellous visual images are made, gold with fire, stone [marble] with Athena’s [olive] oil and water.133 Our makers, who are inspired by the Muses, were already practising in the age of heroes.134

It is not our custom to inscribe the images of our gods and our heroes with their names.135 What need is there for words? From our childhood we Athenians know them and their stories and we learn how to emulate them.136 Some say that images can only exercise their power in the cities where they are set up, whereas stories of great men can be told in words all over Hellas. But while words can be changed by our enemies, images tell the same story for ever.137

And we have a well-tried medicine for that disease.138 We see the bird of night with the other birds flocking round her in admiration.139 It is her nature to serve the purposes of the gods.140 Athena’s living bird with her flashing eyes keep her divine presence in our minds day and night.141 Our signed silver that leaves our mints show Athena with her owl and olive, and for the benefit of those foreigners who can read or remember a sign, we will proclaim that it was you, the people of Athens, who made them from the purest silver dug from the underground riches of Athena’s land, and carried them, with the help of Poseidon all over the world and back to us.142 We will celebrate our kings, both those who sprang from the earth and those who were sons of Poseidon.143 We will tell the histories of those who first ruled our land long ago when only Pelasgians lived here.144 We remember the sons of Kecrops and Erechtheus, when we became Athenians, and when Ion, son of Xuthus, was made leader of our armies, when we became Ionians.145 Our ancestors are always with us and we bear their names.146

We are warned by clever men not to trust what is written by others for that may discourage the arts of memory that lie within ourselves, so that some men may appear to be more wise than they are.147 But, knowing the dangers we do not fear them, and we can also turn to the arts of today in which all Hellas knows we are the leaders and that they then follow. As our own inspired poet reminds us, when he warned of the dangers of tyranny: [quotes] ‘when the laws are written, both the powerless and the rich have equal access to justice’.148 And we will ensure that the new records are kept safe, even when they are made of perishable wood and wax, or written on skin with ink.149

As for what form the buildings should take, your Commissioners have been reading again the works of the great Ionian philosophers of the skills and instruments needed for successful architectony, Theodoros, Chersiphon, and his son Metagenes, who at the time of our grandfathers, helped to prepare the designs (‘paradeigmata’) and also to supervise the building of the largest, the most modern, and the most worthy-to-be-seen sanctuaries in all Hellas.150 Also useful to us is the library of our kinsman, Euthydemos of Chios, whose collection of books is enough to prepare him to become an architecton himself if he ever chose to move from words to deeds.151 [Laughter].

Architectons are useful men, with useful skills in making useful things, and with experience of telling workmen what to do according to rules. We will pay them well for their help in returning our city to heath just as we pay our doctors. But their skills do not fit them to govern a city as you, men of Athens, have been called upon to do.152We will only employ sworn association members with long experience and knowledgeable masters. Only they can ensure the excellence [‘arete’] of the work and keep it in good condition.153 Our own Endoios, who made the ancient dedication on the Acropolis that we have all seen, learned his craft from Daidalos himself.154 We will preserve the old image of Athena seated on her throne that, although in a style that nobody would choose today, was made for Callias by Endoios of Athens, son of Metione, and grandson of our king Erechtheus. Endoios, who made images all over Ionia and elsewhere, learned his skill direct from Daidalos.155

We invite anyone who has knowledge of the designs (‘paradeigmata’) of the building that Libon of Elis is constructing for the Eleans at Olympia, to prove that he is a useful citizen.156 How are the Eleans dealing with the visits of the Earthshaker to the new temple (‘naos’) that they are dedicating in replacement of the brick, timber, and terracotta structure that, all Hellenes agree, is a disgrace that hurts the eyes? The houses made for other gods in other cities, even when they are well made, always fall, but your Commissioners will make sure that Athena’s male children will stand for ever.157

As we rebuild our great temple with the stones that even the Persians could not destroy, every visitor will know that the immortal gods have never ceased to favour those who have served our city by land and by sea, and that they will continue to do so for ever. [Shouts of approval].158

The wise Solon will forever be remembered for reuniting Salamis with her Ionian motherland as the Delphic oracle decided.159 Ionians and Dorians, though we have a common ancestor in Hellen, and together defeated the Barbarians in the immortal battle near the island, will always be enemies.160 But we remember too how Solon, with the blessing of the gods, taught us how to use the fruits of the earth and how to share our knowledge with other men.161 On our acropolis, we celebrate the ancient olive tree that sprang up again the moment the enemies and the traitors left our land. And wood from our sacred tree always protects Athena’s house from the Earthshaker.162

To achieve the useful is always difficult. But a man who can lift a heavy load can easily lift a light one. A good runner will always beat a laggard. But a spear-thrower or an archer who is not the best will die in a battle and lose the whole city.163 We will build our new Propylaia and our new Parthenon to a colossal size.164 And we will build them to such exactitude that they will appear to have been made from a single piece of flawless marble. The winds that blow secretly through narrow openings are sharper than those that are more diffused.165 Any enemy considering laying siege to our acropolis will know that, however big his army, he can never succeed. And even if, as happened in the years of our shame, an enemy has found traitors, he will never be able to knock down our buildings or change our eternal story before the true Athenians return and cast them frothing into the dust.166 To affirm our proud ancestry as Hellenes and as Ionians, we will build two temples that will both be in sight when the processions come to a halt.167 See, men of Athens, the single altar where the beasts are slaughtered and where we share the food and the smoke with the gods.

We Athenians give the honour to Butades and his daughter and to the effeminate Corinthians for being the first to use clay and fire to imitate a shadow thrown by a lamp.168 And as befits our ancient custom of being a people who welcomes ideas that are just and useful, our Athenian potters soon learned how to do better. As we all know, our pottery is now admired and desired by all, and carries pictures of our Athens all over the world even to the wild Scythians beyond the Pontus.169 But we Athenians are not slavish copiers, doing the same things again and again just because they are familiar. Even the divine Daidalos, who received the gift of image-making from the gods, and who taught the skill to our own Endoios, if he were to come back and make images of mortal men in the Daidalian style, would be laughed at.170

As far as is fitting, we will rebuild on the locations of the temples that were destroyed by the barbarians or were under construction at the time.171 We will remind both Athenians and our Ionian kin who live both here and overseas that, unlike the Lacedaimonians, we do not disdain the cosmetic arts.172 Our jewellery makers and pottery workers will prepare the golden beads, the coloured glass, and the precious stones that will capture the eyes as effectively as the ornaments worn by our women on special days, and with which we clothe and remember them on their memorials. We ask the best makers [in Greek ‘poets’] to make proposals, to present preliminary models, and to come and work for us in Athens for good pay. We will proclaim our invitation to all Hellas by sending out heralds.173 We will set up images in places where they can be seen and from where they can send their lessons into our minds both as we move around our city and on festival days.174 But we will rearrange all the festivals for another day if the city is in danger. [Laughter].175 We already have many useful images, including some dedicated long ago, such as those of the Tyrannicides, who protected our city, that will remain for ever as heralds for the eternal values of our city and of our democracy.176 They will produce children, and children of children, for ever.177

Since the Tyrannicides and our other heroes show us how the life of the city is always more to be valued than that of any man, we propose that no citizen should be permitted to put up an image of himself nor of any official, however famous, who is only holds his office for a short time on behalf of us all.178 It will be for our grandchildren to decide who should be commemorated in perpetuity among our city’s heroes. As the great Solon told us, we cannot judge men till after they are dead.

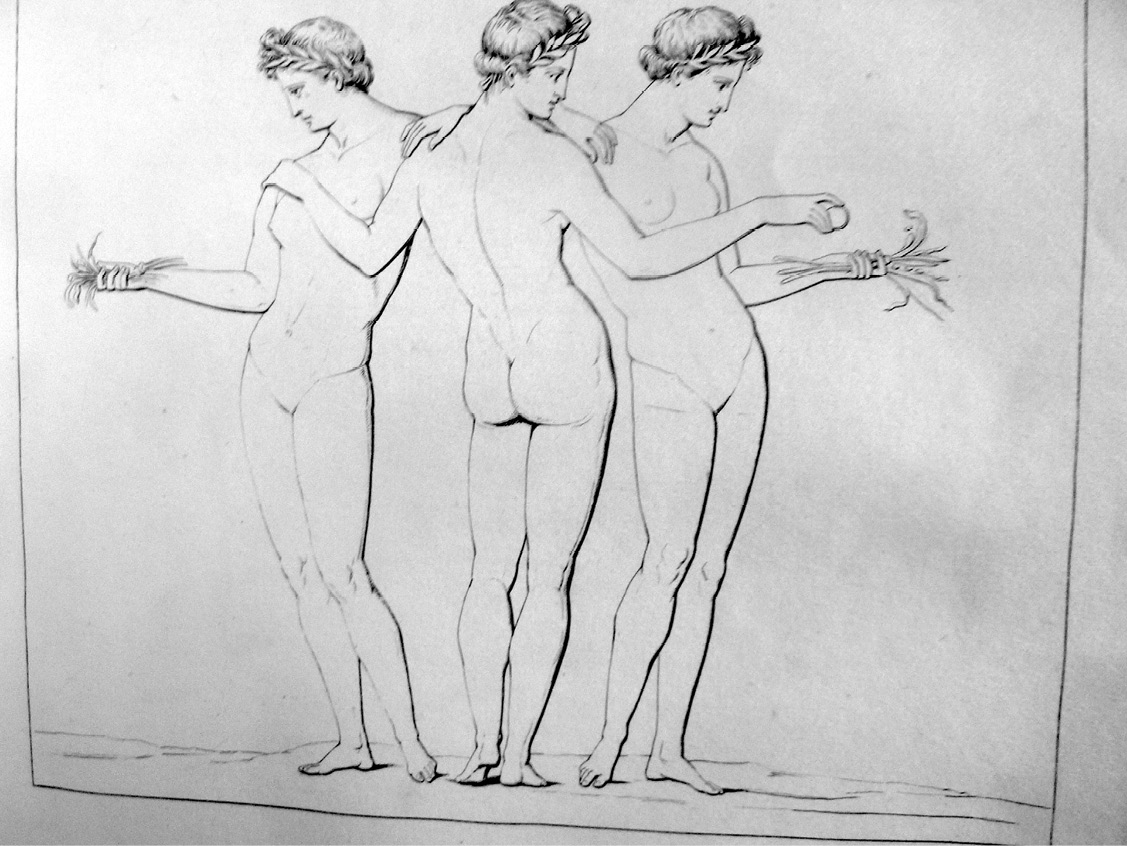

So what must we do? We must first encourage the practice of ‘charis’ that binds together the rich nobleman and the poor labourer. Your Commissioners welcome proposals from those who have useful knowledge for translating into stone the story (‘logos’) of this preliminary sketch (‘paradeigma’). [The reciter passes round an image as shown in Figure 2.2].

This picture, when set out in a prominent place in imperishable stone at the entrance to the Acropolis, will draw the eager eyes of men and boys to the exciting bodies of the naked women as they dance, in a perpetual circle, each in her proper place.179 And their eyes will follow the beams emitted by the eyes of the women to the fruits that they are holding out to us in their hands. Just as a well-managed farm, in which the master, the mistress, the slave, and the beast work together to produce all that is needed for the body, so too, just as harvest follows seeding, a city that practises ‘charis’ will always produce ‘arete’.180 And we, our sons, and their sons will commission more stories to be told in bronze and marble now and for ever in the future.181 The men of Athens will look upon our beautiful city, day after day, and become her lovers.182

Figure 2.2. ‘Paradeigma for an image of the three Charites’. Copper engraving.183

Since we Athenians rule ourselves, we have learned to distinguish what is real from what are mere imaginings and attempts to deceive us.184 Men who walk alone lazily feed their own imaginations without bothering to consider other possibilities.185 We Athenians imitate our skilled midwives who, from their long experience in their art, know when they can bring forth the true and when they must abort the false.186 And we will ensure that those who participate in our festivals obey the rules that our city lays down. [Quoting] In sound is our sight, [unquoting] as we all know.187 Even a change in our songs can hurt the whole city.188

We will commission the best musicians of Hellas to prepare the songs that we will sing at our festivals. The proxenos of misty Thebes, has already celebrated the uniqueness of our clear-air city. [At this point, a section of the audience begins to chant an extract from a commissioned work of Pindar that had already become almost an Athenian civic anthem, inadequately rendered as ‘shining and violet-crowned and celebrated-in-song bulwark of Hellas, famous Athens, god-favoured city’].189

We will ensure that all who live here obey all the laws, both old and new, that, with the help of the gods, our city has enacted for our safety and for our benefit.190 And we will show stories that celebrate our continuing progress from brutishness and our city as a school for all Hellas.191 Our city will educate not only our own sons and daughters in the qualities that have made us great, but other Hellenes too.192 On our sacred hill we will commemorate the moment when Athena taught us how to domesticate the grey olive tree.193 We will remember the tasks performed by our women in the ‘oikos’, where we lived in the childhood of Athens before we became a ‘polis’.194 Our Athenianesses as much as our Athenians, all will see, are superior to those of all other Hellenes, as mothers, as teachers of our children, and as makers of the useful things that we wear.

Theseus was a great hero who did great things for Athens in his time and we have his bones in our land where he will be remembered for ever.195 See him rescuing unfortunate women fleeing the wrath of Ares who are being torn from altars by brutish monsters. Our new philanthropy, as you all know, has now become our custom, decided upon by the city with the consent of our citizens, and will always remain so. [The reciter passes round an image as shown in Figure 2.3].

Figure 2.3. Theseus as rescuer, as presented on the frieze of the classical-period temple at Phigaleia.196

Refugees are ambassadors for the generosity of your city, better speakers than any inscribed monument (‘stele’).197 And it was the sons of Theseus, Demophon (‘he who speaks for the people’) and Akamas (‘the untiring’) who showed us by their deeds how greater works can done by sons than by fathers, now and in the future.198 Our temple will celebrate them too.199 Since some who visit our acropolis, including our children, are not yet as mused as we are, we will not show gods and heroes when they are untrue to their divine nature.200

Some have suggested that Athenians cease from killing the men we capture when we seize a city or in battle.201 But if enemies are permitted to live they will come back and attack us. Nor can they be turned into useful slaves. We must therefore continue to follow the ancient laws of Hellenes and barbarians.202

We proclaim our autochthony not only on the dedications to Athena but on the sacred buildings and at other places in our favoured land.203 Just as when we are captivated by a well-prepared and multi-coloured funeral oration, we feel more noble and more tall, and our companions too feel that our whole city is ennobled, so we will be able to use our festivals to achieve the results we all desire.204 It is not enough that we and our friends are given an occasional treat, like the nibble of a quince that our great Solon recommended to brides before they are first taken to bed, as a sign that the delights of lips and speech should be harmonious and pleasing from the first day.205 As in our tragic drama, the number of ways in which our stories can be usefully told and usefully seen, told, and heard, to the benefit of our city, is limited only by the number of festivals and by the willingness of our citizens to show their ‘charis’.

We will grant immunity to citizens from being seized for debt during a festival, so that these occasions become havens of peace in the stormy life of our city.’206 And we will defend the gods against irreverence (‘asebeia’).207 We have all been to festivals where some of those present say the right things about the gods and the city, who parade, sing, dance, and pray in unison, but then, when the food and drink run out, a few [signifies contempt] ‘cynics’ start sneering.208 We will punish with death or exile, and with the confiscation of property, anyone who steals from our holy places. And we will accept the testimony of slaves, who often know what is happening within a household (‘oikos’) and grant them freedom, so that even the meanest can see the benefits of performing good citizenship.209

Our festivals will take place both at rosy-fingered dawn and at violet-crowned evening, not only in eye-dazzling summer but also in soft-shadowed winter when our mariners are at home with their families.210 At no other times do our images reveal the gods more clearly to us than when the Earthshaker sends his life-giving watery tempests, on which our city depends, and when, to delight as well as to terrify us, for the gods like to be playful, he lights up the starry sky with his sudden silver rods.

There may be some who think that Athens already has too many festivals, that the crowds block the traffic, interrupt the life of the city, and slow down the work that many have to do.211 And we hear the same men complaining that our metics and our slaves are dissolute and out of control, and by forgetting their proper place, are corrupting the whole city and even our language, with their foreign usages.212 The duty to advise the city on how much of its useable resources (‘chremata’) the city should devote to meeting its many needs lies with other commissions, and today we will not go into the precise amounts either on the costs of our proposals or on how best to pay for them. It is however right for you to learn what is needed as early as is possible, not only so that we can decide on how best to manage our farms so that they will produce animals and other foods and wines that are needed at the right time, but also to give us time to consider how much the most fortunate will be able to afford to contribute as our duty and our obligation (‘charis’) require us.213 Only a foolish steward agrees to buy a donkey on his master’s behalf without knowing whether it is stubborn or biddable, how much food and water it will consume, and whether its labour will improve the income of the farm. And we remember the sheep who complained to the master that while they worked hard every day to produce milk, wool, and leather, his dog just lay around eating food from his master’s table, and the master had to explain to the stupid sheep that it was the dog who guided them, guarded them, and kept them safe.214

Festivals bring us together, even those whose nature is to serve. And as the festivals become more frequent they drive out those gods that are not approved by the polis. We will take measures against men who set up their altars and slaughter sacrificial animals in the storkade.215 And despite the best efforts of the Areopagus, foreigners from the east have brought their [the reciter pauses and signifies contempt] ‘Magi’ into our city and turn to magic practices to try to communicate with the gods directly. We swear by Zeus, by Athena, by all the gods of Olympus, and by those ancient gods who inhabited this land before them, that if these evil men or unchaste women use their despicable tricks to fix horse races, on which honour and money depend, and harm men and women whom they want to destroy, they will not succeed.216 Their cursing tablets, often cunningly made from imperishable lead, have been found hidden in our most sacred places, including the abodes of the dead and among the bones of our babies.217 When cursing is appropriate, it is our city not individuals [‘idiotes’] or nurses or slaves who will decide who must be cursed.218 Our city is not a bar of iron or a slab of marble that looks strong at first sight but has a hidden seam that causes it to break up if it is ever put under strain.219

So what more must we now do? In a city, as in a human body, although disease may flow from the parts into the whole, the wholesome parts can also correct the whole.220 Some measures to preserve ourselves from the effects of marriage with foreigners have been taken, at the behest of the wise Pericles.221 But we need new regulations and new officers to enforce them.222 And laws by themselves are not enough. As we all know, love (‘φιλότης’) brings together the four elements of which all nature is composed, and strife (‘νεῖκος’) causes them to separate.223 And, as the wise Anacharsis told Solon who thought he could bring about order in the city with written laws, ‘these laws are like spiders’ webs; they hold the weak in their meshes, but are torn to pieces by the rich and powerful’.224 So what better measures, we ask every man of Athens to consider for himself, can we take to bring our city back together as strongly as we were when we faced the barbarians? And the answer your Commissioners give you is simple: Just as a farm, however small, when it well tended, will yield a harvest; just as the Scythian slaves that we have bought, when given their food and shelter, will contentedly keep order at disturbances; so too can our famous festivals continue to produce harvests of peace and harmony in our city.225 And just as we must make our acropolis secure against any attack by an army and make sure that enemies can see with their own eyes that it is impregnable, so too we must protect our city’s most valuable possessions against infiltrators, usurpers, and thieves.226

You, men of Athens, who share a lineage of unrivalled purity, do not need to be reminded that the aim of ‘paideia’ is to turn our young men into brave soldiers.227 So how can we use our surplus of useful things to produce useful men?228 As we look out across Attica we see our groves of tame olive trees, that, as our poet sings [signifies quotes] ‘are a terror to enemy spears’ [unquote].229 Since we can obtain whatever we want with the proceeds (‘poroi’) of what we exchange, our barns are no longer full of stocks of food, drink, and oil that are not yet needed and that attract the greedy eyes of tyrants and robbers.230 As we look out to Brilessos, that once could only support a few goats, we see men at work harvesting other gifts that the gods have bestowed on our land of Attica.231 It is fitting that, as our fathers decided, for our sacred sites, autochthonous men should use autochthonous stone.232

As for the stories that our great temples will tell now and for ever, our problem, men of Athens, has been how to choose which of our heroes to leave out than which to include.233 None will be without signs.234 We need no longer show the monsters by which our ancestors recalled that time using images made from unshining poros stone.235 It is more useful to be reminded of the brutish life that those who first seized Attica and founded our city had to endure so that we today and in the future can live in a well-run city.236 We will offer pictures that by their freshness nourish the sight and draw our minds to ancient deeds that deserve to be imitated.237 Made from eternal marble, held with hard iron and gilded bronze, and easily renewed if their cosmetic paint is wiped or stained by rain, the images will draw the eyes of our people, causing them to remember, to re-tell, to imitate, and to relive.238 We will make sure that no enemy of our city, either from Athens or from elsewhere, will destroy or deface them.239 We will present the history of the war against the Trojans from the first sailing of our fleet to the glorious burning and sacking of that city.240 As Homer sings, we Ionians, with our long flowing chitons, were among those who captured and sacked Troy, as we now celebrate and commemorate at our festival at Delos.241 We will make our own Menestheus live again, wielding his death-dealing axe and seizing his deserved share of the spoils.242 Our brave sailors were also there. As Homer tells us, when Ajax (Aias) brought twelve ships from our Salamis to Troy, he [quotes] ’halted them where the Athenian phalanxes were stationed’.243 In those never-to-be-forgotten times, which we relive in our festivals, it was we Athenians who were the gallant Opuntian Locrians, doing more than anyone thought that we could, and leading all Hellas to victory.244 We will show how our gods fought against the Giants and our own ancient victories against oriental barbarism.245 Every good citizen of Athens knows the name of his ancestral father who lived here in our ancestral land, the common possession of all Athenians.246

And of all our festival feasts, none gives more delight to Athenians than those in which we remember the ancestral heroes of our kin.247 [A member of the audience, foreseeing where the argument is leading, intervenes: ‘Can the Commissioners promise that we, the Anagyrasians, who are descended from Erechtheus, will be able to see and remember our ancestor Anagyrus?’, a remark that is met with shouts of assent and some knowing nods. The reciter, picking up the mood, responds]. Our friend speaks well. Your Commissioners will show how all our demes and families came direct from the earth.248 It would however be wrong for our temple to show insulting versions of our stories put about by a few malcontent and godless playwrights.249 Some of us wish that some citizens would show their charis by donating a few black oxen to the festivals that bring us together as Athenians, or helping to pay for a warship, instead of confusing audiences with their clever honied words at the Dionysia.250 And we assure you that our people, including our women and children will be able to look at the stories in complete safety just as when the chorus watches a tragedy performed by actors in our festivals.251

Our citizens will call on the Sun and the Moon, on our swift-winged breezes, on the sources of our rivers, and on the laughing waves of ocean, by which our mother earth nourishes us.252 All true citizens will be able to point out their own ancestors and share in the glory of their great deeds.253 The images we commission will help us to see the invisible gods who helped to give our city the glory that she now deserves, as well as all the other gods, known and now unknown, who have favoured our unity as citizens, as kinsmen, and as heroes held together in unbreakable bonds.254

The mortals will be tall, straight, and perfect in limb from having been carefully moulded by their kin from the moment of their birth.255 Our young men and women will never be fat, short, and flabby like wild Scythians.256 Long ago we adopted a good custom from the noble ‘long-heads’ and soon all our sons and all who come later will be as the brave and wise general Pericles son of Xanthippos.257

Since everything is intended by nature to fulfil a purpose (‘telos’) all the men carrying jars or containers will use their left shoulder, as is needed when they defend themselves in battle.258 With their horses too, it is hard to persuade them to keep their ranks in processions.259 It was here in our land [pointing to the hill of Colonus] that Poseidon first gave men the horse-taming bridle and our horses, like our other beasts, will soon be as far advanced in their nature as their owners.260

Since the glorious time when we sacked the city of the Trojans, the best-bred of our youth have been ready to do their duty and to sack other cities and increase our wealth of possessions.261 All over Hellas, the sons of Homer honour them in their rhapsodies.262

We mortals are, by our nature, moved by intellect, imagination, purpose, wishes, and appetites. And as we respond to our feelings, the objects of our desire move us to action.263 And so we heed the wise advice of our guest and friend Pindar not to make images that stand idly on their pedestals and do nothing more, but they will [the reciter signifies by tone of voice a quotation] ‘inspire men with impulses which urge to action, with judgments that lead them to what is useful’.264 We will only choose the stories that will be useful to our own kin, including to our women, and not to strangers.265 As our own god-inspired poet sings [quotes] ‘Strange and wondrous is the power of kinship and companionship’. It is a power that even the gods themselves find and use for good or ill.266 And we will continue to send kinsmen to plant our seed overseas in places, such as Sicily, where none of the Hellenes are autochthonous, for unless we do so, we will lose those cities that we already hold.267

When our words have become deeds, when we visit our acropolis we are smitten as directly as Hippodameia is by Pelops, as if struck by a kind of lighting of the eyes, by which both are warmed and enflamed, and our minds are drawn to the images as directly as the craftsman’s kanon goes straight.268 And, as we all know: [quotes] ‘he is no lover who does not love for ever’.269 Just as a breeze or an echo rebounds from smooth rocks and returns whence it came, so too the stream of useful stories passes through our eyes, the windows of our minds, and causes us inwardly to accept what they tell us.270 And when our processions move amid the changing shadows cast by the Sun and by the Moon, turning the pictures into shadow pictures (‘graphe’ into ‘skiagraphe’), they come alive in our minds. We take their stories shown on our buildings into our minds as we look at them and hold them there, perpetually renewed with every glance at the everlasting stone which the gods have bestowed on us.271 The shining metal flashes, the mute stones speak, and the idols move and converse like living things.272 When, as Orpheus sings, [quotes] ‘the hour of delight arrives’ [ends quote] I see each grasp the wrist of his nearest companion.273 I see true Athenians joined together like the rings of an iron chain, and the power of a Heraclean stone passing through every one.274 The stories enter our minds both by our seeing and by our remembering.275 As the heat rises in our bodies, the images are entering through the openings, ready to rise even when they are asleep, and are far from Athens.276

Our young children are given lessons (‘paideia’) by their parents and their nurses, and examples are shown to them in stories told in words. Even the youngest and least educated among us has eyes to see and can receive pictures, and the more often that they look upon them, the more the stories will live in their memories.277 Some fortunate boys learn to love ‘arete’ and wisdom (‘sophia’) by becoming the lovers of wise men, whose intensity of desire given by Eros surpasses the love of women and of family.278 But, for the governing of our city all our people work must together in harmony and mutual trust. And to the end (‘telos’) that we are constantly reminded of what we share with one another, we follow the wise examples of Theseus and Solon when they brought us together into one city in former times. Just as a farm, when it is well tended, will yield crops for ever, and just as our Scythian slaves, when given food and shelter, will dutifully keep order at our meetings, so too, with foresight and care, our city will produce harvests of civic peace and harmony now and forever.279

An ability always to put our city first (‘arete’), we all know, is not born in the nature of mortal men. It has to be learned and frequently practised like the skills that some men have in writing poetry, in making visual images, in performing music, or even in delivering [the reciter here indicates by the modulation of his voice and his body language that the Commissioners are about to make a self-deprecating joke emphasizing the next phrase] a ‘useful’ speech.280 [Pause for laughter]. And as Prodikos reminds us, only a fool thinks he can acquire these skills just by praying to the gods.281

There are many paths to glory. As the eagle of Ceos sings: ‘Each man seeks a different path on which to walk to attain conspicuous fame; and the forms of knowledge among men are countless. Indeed, a man is skilful if he has a share of honour from the ‘Charites’ and blooms with golden hope, or if he has some knowledge of the prophetic art; another man aims his artful bow at boys; others swell their spirits with fields and herds of cattle. The future begets unpredictable results: which way will fortune’s scale incline?’ [Pause]. But ‘The finest thing is to be envied by many people as a noble man’.282 The names of all those who have served their city by generously giving her a share of their surplus money will be commemorated for ever on the imperishable marble of our everlasting city.283

[The reciter signals that the Commissioners are approaching the peroration].

Look about you, men of Athens. The tables and tents are being taken out of storage. The servants hang fabrics on our buildings. The garlands of blossoms that the Charites love hang on the gates.284 At Anagyra, at Acharnae, at Eleusis, at Rhamnos, at Piraeus, families rise before the sun. At Salamis the men are woken from their beds by their dutiful wives to make sure they do not miss the boat.285 See our brothers and sisters putting on their coloured clothes and donning their flowered chaplets.286 Smell, men of Athens, the wild violets of the garlands.287 Hear our Athenian women singing: ‘Never will we divide the sisters of Charis from their sisters, the Muses, forever married in a sweet union / Never will we live among coarse men and women, but we swear always to be numbered among those who wear the crowns’.288 The adulteresses, the criminals, and the oath breakers shrink away in shame, excluded from the glories of our city.289 The pimps tremble with fear that they will be put to a deserved death.290

The men of Athens go to parts of our city that they seldom visit, full of wonder at our famous hills, at our agora (market place) where our goods as well as our news are exchanged. Those who seldom have time visit our holy acropolis to see the latest decisions on treaties, on expenditures, on honours conferred, and stop womanly gossip and idle and vexatious [emphasizes] ‘Rumour’ from corrupting our democracy.291 Some of the most useful wisdom began when groups of friends arranged to meet as they went together to see the new Thracian festival at the Piraeus, that, although still new, as all are agreed, is well arranged and orderly.292 As we walk in the Panathenaic procession we see the young men of the Academy studying the secrets of Nature and acquiring useful knowledge, sometimes inviting wise men from abroad to help them.293 As Herodicus says, they go to the city wall and back, and sometimes even to Megara [laughter].294

We see our citizens and our kinsmen walking first in reverential silence and then, at the signal, the music starts at the bidding of the leaders, and they begin to dance and sing together.295 As we all know, there is nothing more pleasing to the gods than to see, to hear, and to smell the processioning crowds, as the music-making flutes are mixed with the bleats of the doomed animals.296 The gods, who have no need of our praises, joyfully join the mortals in the feast.297 Listen to the crackle of the fire, smell the sizzling fat, hear the people sing and dance together with joy as the bursts of flame rise above the altars.298 Happy too are those who watch and who smell the flowers of the garlands from afar.299 They know that our city can be relied on to keep the gods on our side. Our festivals nourish the memories not only of those who see our Acropolis every day, but the dusty-footed workers in the fields who only come here on special occasions.300 At our night festivals too, those who are travelling by land from our harbours see the Acropolis sparkling with lights that match the stars.301 Wisdom is lighting up in their minds with visions.302 As the men, women, and children of our city live again the stories of the heroic deeds of our ancestors, the lessons are inscribed into the wax-tablets of their minds.303 Our peoples are glued together as securely as one piece of wood is joined with another.304

In peace the images return to us in dreams that bring messages from the gods. In war too, when we stand together, hoplite by hoplite, horseman by horseman, oarsman by oarsman, we are united by a single Athenian mind.305 As Homer tells us, Athena not only protects our city but gives us the means to sack the cities of others, whether Hellenes or barbarians, when they are mad enough to resist our just demands.306 See the battles in which all Ionians act together to defeat the arrogant Dorians who cannot forget that their ancestors conquered the lands that are now occupied by other Hellenes.307 See the stupid and untrustworthy Thebans running like frightened sheep. Although we are far from home and meet many dangers, we know that Athens, the mother who bore us, always remains.308 We will not rob our ancestors of the honours that they have won since the earliest times.309 On the contrary we are glad when some god, out of admiration for our natural ‘arete’, has sent a war that shows that we are the equals of our fathers, and that, if we die, we too will be honoured for ever.310

Many here will also have heard your fathers speak of that other never-to-be-forgotten year when Phainippides was archon, when alone of the cities in Hellas apart from the gallant little Plataeans, our Athenian men of Marathon defeated forty six nations.311 In that year we saved civilization itself.312

When your Commissioners first looked over the ruins of our shining city on the hill of Kecrops, with its broken dedications, kouroi and korai, forever young but now no longer able to bringing comfort or memory to the families who commissioned and visited them, we saw the shameless snakes slithering on paths along which our daughters used to dance and sing their music, hissing and spitting even at the wise bird of the night. We hear Solon, the founder of our modern Athenian constitution, cry out his immortal lament: ‘How my breast fills with sorrow when I see Ionia’s oldest land being done to death’.313

For thirty years, the effects of the barbarian invasion lay about for all to see, but as the metal crowns (‘poloi’) of the korai were stolen to be melted down, as the broken marble was used again for other building purposes, and as the serpents and the scorpions made their homes among the ruins, the memorials that had been living reminders of our glorious past became instead evidences of neglect and disrespect. And it was increasingly burdensome for us to have to explain the state of our holy places to our rising younger generations of future soldiers. Never again, our city decided, can our holiest places be put at risk.

Our ancestors, let us remind you, lived close to our life-giving spring when they first founded our city before they had even begun living together as households.314 And it was not long afterwards, as we remember from the stories we learned in our boyhood, that the Hill of Kekrops became the Acro- [the reciter pauses for emphasis] -polis.315 We will build to ensure that our clear water will always be plentiful on our Acropolis.316 And, as in all the great cities of Hellas, we will welcome our new sons and daughters on their birthday, with water from our city’s pure and cleansing stream.317

It was right to re-use the broken marble dedications to the practical task of repairing the Acropolis walls.318 A memorial that does not carry a story or a memory, whether they are family members or others, is powerless painted stone and metal.319 We are now at peace with the Great King, and do not need as many warships as in the past.320 We have rebuilt our walls and our harbours, and our frontier forts too are well prepared. But the Great King, whose gods tell him that he rules the world, may come again one day, for who can foresee the future? The perennial struggle between Europa and Asia that began long before the war against Troy can never be over. Nor can we neglect the ambitions of the Lacedaimonians, the treacherous Thebans, and the luxury-loving Corinthians, who all look upon our city with envious eyes.321

We will employ craftsmen, carpenters, metal-workers, farmers, and men knowledgeable in numbers and in the management of households, and follow the advice of those with experience in commanding armies. Since the stone, the main material used by temple-builders, already belongs to us, most of the public money that we will spend will benefit you, men of Athens, and not flow away. For the cedar wood that we will obtain from other countries, we have the ships to bring it and the surpluses of fruits to give in exchange. We will learn too from those who understand the arts of divining for the deepest secrets that the gods reserve for themselves. You may plant a field; but you know not who shall gather the fruits: you may build a house well; but you know not who shall dwell in it. And although you are able to command, you cannot know whether it will turn out to be worthwhile to you to have accepted the honour. If you marry an attractive woman when she is still a girl, you cannot tell whether she will bring you sorrow.322No madman, out of impiety towards the gods or from a terror that his name will not be remembered, can destroy the holy buildings.323 But nothing in human life is certain.324 No man and no god can escape the changing winds of Tyche.325 As the old Egyptian priest told our Solon [quotes] ‘There have been and there will be many and divers destructions of mankind’ in which the earth was burned up and all our ancient knowledge was lost.326 And it was out of respect for that truth that the Commissioners for the design and construction of one of our images has, with the assent of the Assembly, inscribed their publicly-displayed accounts of the annual expenditures to ‘Athena and Tyche’.327

When we travel to the land of Pelops and we ask what happened to Mycenae, rich in gold, the answer is that the name of the city of Agamemnon, which sent eighty men to fight at Thermopylae, is engraved with ours on the Brazen Serpent at Delphi.328 The ‘city of the walls’ [Tiryns] too, whose men were with us at Plataea, is also honoured.329 But the men of Argos who were cowards in the wars against the Medes and the Persians now see their runaway slaves take over the whole Argolid.330 For some cities, there is everlasting glory, but to those who show themselves to be unworthy, the gods assign an endless shame.331 Indeed, some wonder why Agamemnon and his [implies contempt] Argives took so long to win the war against the Trojans.332

Our children will always learn about the blind poet of Ionia. But we need no Homer to sing the praises of our city.333 Our age too has its poets who carry our fame across Hellas and far beyond.334 Our Athenian walls will not disappear like those that our ancestors, at Nestor’s bidding, once built on the beach at Troy.335 We have not destroyed these ancient walls that Heracles, maddened with grief and desire for vengeance, wanted to tear down with crow-bars and pickaxes. We Athenians will always sack cities, take plunder, and seize women unless there is good reason to do otherwise. But our enemies are men not stones.336 We will leave many great signs of our power that will make Athens an object of wonder not only to the men of today but to those who come after us.337

Our city gleams with radiance and our land is a garden. Our city is a sacred fire that never goes out, but moves around from one time to another, seen by some and then by others, a sight made more fair and more just by the ways we live and have always lived, and we must pity those who live outside our hegemony who are deprived of such gifts.338 Athens, favoured by Athena, will ensure that we and our children will always preserve our sacred places and will add new memorials to our glory just as our ancestors did, despite their misfortunes.339 And our holy places will be useful not only to the Athenians of today but to our sons for always.340

But, as we approach the end of our speech, we say again that nothing in human life is certain.341 Mountains overwhelm cities with fire and the earth itself is shaken.342 As Homer teaches us, even the gods cannot see the future.343 But we know that, if a new Minos again invades our land with swift ships, if Zeus and Poseidon again cover our land with water, as happened nine thousand years ago when Athens was in command in the long war against the huge island of Atlantis, then a new Deucalion, a new Hellen, and a new Ion will arise to repopulate our land.344 And as the men of that time look at the ruins of our Acropolis, just as we today look on the ruins of the city of Agamemnon, they will say that here once stood the greatest city of Hellas and here lived its greatest men.345

And now, men of Athens, it is time to sacrifice a sheep and pour a libation. And let us make a prayer that the gods will preserve all the right things that have been spoken today and punish us if we have sung out of tune.346 Tomorrow all who have the right to speak will decide.347 As our friend from Colonos reminds us, [the reciter here gestures towards the Hill of Colonos] ‘In any question, the truth always has the greatest strength’.348

[The president dismisses the Assembly].

A Reflection on this Experiment

Since the Parthenon and the other buildings were actually built in record time, without interruption, we can be sure that all the necessary approvals were given by the institutions of the city and that any unforeseen problems were coped with. Although the process may have been more prolonged, untidy, and contested than the composers of the speech have suggested, the institutions were persuaded to accept the proposals. In the short term at least, we can therefore say that the Commissioners were successful, and also that it is likely that many of the cognitive, discursive, and rhetorical practices illustrated above were employed.

For resistance to the proposals that we can be certain occurred, although most of the evidence comes from non-contemporary authors, I will offer in Chapter 5 an attempted reconstruction of another ancient historiographical genre now seldom practised: a formal ‘rhetorical exercise’ composed with hindsight. I will use the opportunity to try to reconstruct what can be said about the opposition to the Commissioners’ proposals for building the Parthenon, attempting to recover both the conventions and the substance of the contestation.

As for the potential value of the experiment, my initial aim was simply to see whether the discursive environment could be reconstructed from the inside looking out, and if so, what it might look like. I hoped that it might prove useful in treating the strangeness as a topic in its own right and as a caution against the unconscious biases to be found in much contemporary as well as past scholarly writings. As with scientific experiments, although it does not claim to be the only way the material can be presented, it offers an implicit challenge to others to try to replicate the results. Although obviously the weight attributed to each component could be altered, at the time of writing, I cannot think of any that has been omitted. What I had not expected to find was that the buildings were of less importance than the festivals that took place in their vicinity, that at the receiving of the officially endorsed mythic stories the media of performance were integrated with those of inscription. I was surprised to find the framing offered by kinship and Ionianism, the brutishness narrative, and the emphasis on success in aggressive war as the main collective aim of the city. I had not expected that, with the results of the experiment to hand, I would be able to make more authoritative suggestions on what stories were displayed on the Parthenon and how they were consumed.349

Meanwhile, in the following chapter, I revert to a normal modern voice to discuss how the Parthenon, when built, was encountered in classical times, with suggestions for the genres of seeing that were practised, for which the evidence is also patchy. And I will suggest my own solution to a long-standing question about the Parthenon frieze that, without implying that the speech offered above is more than a controlled experiment, is likely to prove more persuasive when it is set within a discursive context of the kind attempted above.

1 The title picks up on the wide range of metaphors relating to ships and voyaging, some already dead or moribund, that were common in classical Athens, and brought together by, for example, Brock, Roger, Greek Political Imagery from Homer to Aristotle (London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), http://doi.org/10.5040/9781472555694. At the time of the Greek Revolution, the commonest words used to describe the building of the new nation were variations on ‘rebirth’ and ‘regeneration’. In classical Athens, such concepts, which owe much to post-antique Christianity, seem scarcely to have existed.

2 Although classical Athens had many characteristics of direct democracy by those adult men who qualified for full citizenship, in practice in many respects it was an oligarchy, as pointed out in the Thucydidean speech put in the mouth of Athenagoras of Syracuse at Thuc 6. 39 1 and 2.

3 The claim to be avoiding rhetoric, or not to know about rhetoric, is a common figure of rhetoric, for example in the opening section of the Panathenaicus by Isocrates, and one that the Athenian audience would discount as a mere conventional courtesy. Even in the world of myth, the character of Hecuba in the play by Euripides of that name, in pleading at line 819 with the character of Agamemnon as she faces death or slavery for herself and her children, and the destruction of all that Troy meant, apologizes for not having learned the art of persuasion, ‘the only tyrant’, implying that if she, like other mortals, had been more willing to pay the fees, she would not be in her present situation. Hecuba’s invoking of a visual image in the same speech in order to make vivid her situation both to Agamemnon and to the audience and readership is referred to in discussing Figure 2.3 below. The Commissioners’ promise to confine their speech to what is ‘useful’ echoes the advice given by the character of Athena in the passage from Euripides’s Suppliants discussed with reference to Milton’s Areopagitica at the end of St Clair, William, Who Saved the Parthenon? A New History of the Acropolis Before, During and After the Greek Revolution (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2022) [hereafter WStP], https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0136, Chapter 22, https://doi.org/10.1164/obp.0136.22. The Commissioners also echo the sentiment of the speech by the character of Ion in Euripides’s play of that name, in which he laments the rights to speak in Assembly the he would lose if it turned out that, as a result of an audit of the evidence for what happened at the time of his birth, he was disqualified from speaking under the law of 451/0, to be discussed in Chapter 3.

4 The Commissioners make a point that seems to have become a cliché, included in the Platonic dialogue the Menexenus at Plat. Menex. 235d and 236a as an example of how to anticipate an objection. The Menexenus, a dialogue in the style of Plato, may have been written by him or another author as a rhetorical exercise, not as a work intended to deceive. The saying was attributed to Antiphon who was regarded as the best public speaker in classical Athens.

5 An example of the many metaphors drawn from the building industry, following, in this case, Aristotle in his treatise on rhetoric. Aristot. Rh. 1.1.5, An image of a measuring rod as used in the long eighteenth century, which matches what is known of actual ancient measuring rods and the metaphors they attracted, is at Figure 1.8.

6 A common rhetorical device, of which there are at least three examples in the plays of Euripides. Noted with references to the surviving plays and fragments by Karamanou, Ioanna, ‘Fragments of Euripidean Rhetoric’, in Markantonatos, Andreas and Volonaki, Eleni, eds, Poet and Orator: A Symbiotic Relationship in Democratic Athens (Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter, 2019), 90–91, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110629729.