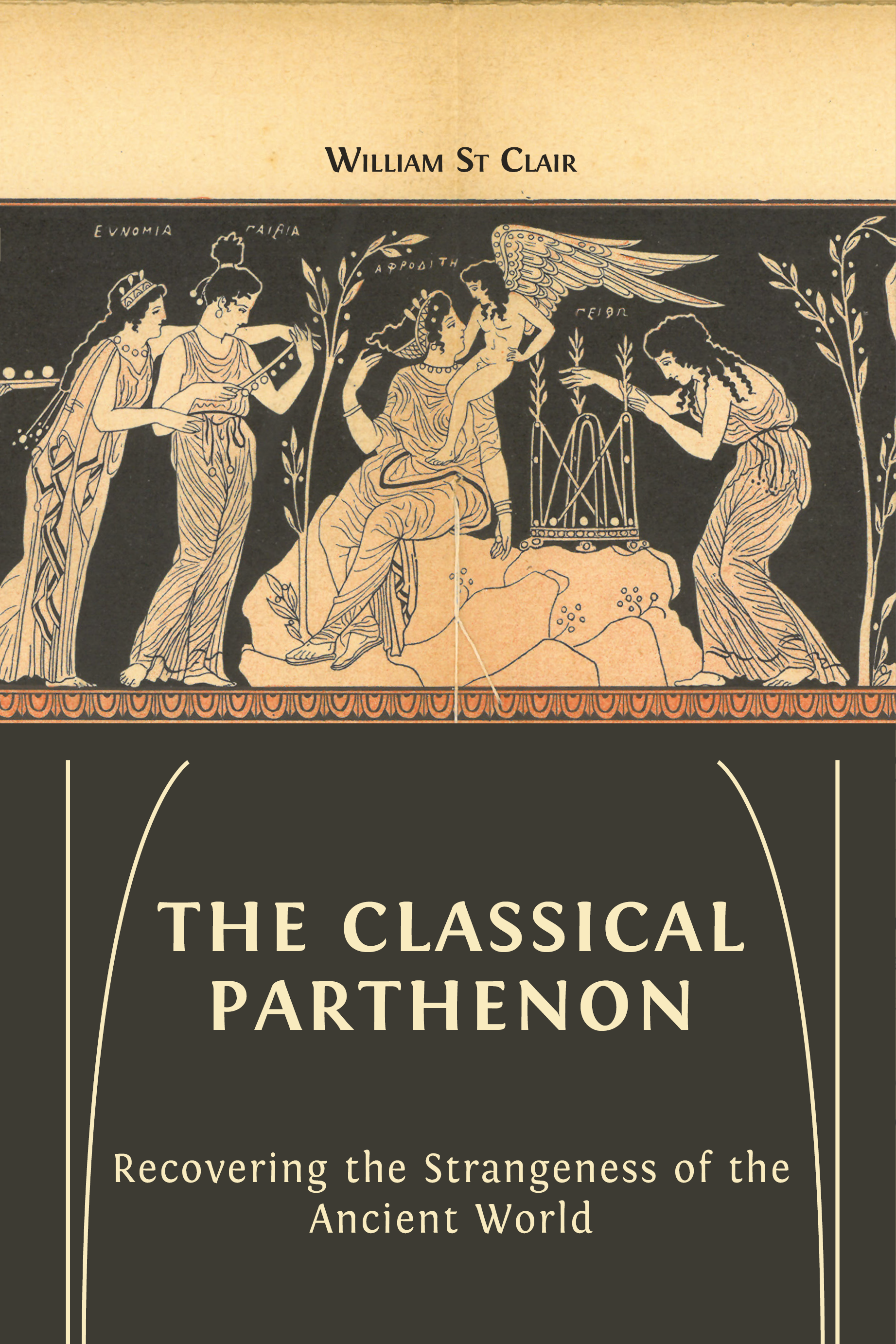

4. A New Answer to an Old Question

© 2022 William St Clair, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0279.04

As for the frieze of the Parthenon, what experiences, I now ask, were offered to the ancient viewers when the building was first brought into use? What events and stories were pictured and commended? How, and in which contexts, were they encountered? What expectations did the men, women, and children of that time bring to the experiences? What emerges if we temporarily throw off the mind-forged manacles of western categories, traditions, and academic disciplines, and look instead for answers that fit comfortably, and even predictably, into the discursive and rhetorical environment?

The frieze presents many of the standard components of ancient Greek festival processions as described by ancient authors and pictured on ancient objects. Large numbers of men, women, and children are shown as coming together for an occasion that will involve the ritual slaughter of cattle and sheep, whose meat, the viewers of the composition will know, will be used in ritual feasting. Indeed, the fact that only large and highly prized animals are pictured, rather than the pigs, rabbits, and fowls that were more commonly used in real festivals, itself marks the pictured event as special. The bones and other inedible body parts of the slaughtered animals will, in the fiction as in real life, be ritually burned, in ways that ensure that the fire, the smoke, and the smells, including some specially contrived with odorous substances added to the fire, catch the attention of people within a wide local periphery. The participants in an actual festival were being invited by the frieze to imagine a fictional festival.

At many actual festivals, the participants were not performing for an audience external to themselves like actors in a drama, but within in sight of one another for long periods, with all the pressures to conform, at least outwardly, that such practices bring about, and that in classical Athens were among their publicly acknowledged purposes.1 It is however unlikely that it was always possible, however eagerly and sincerely the participants may have wished to transport themselves into an alterative immaterial world, that they could forget or ignore the material setting. Many rituals required long-term planning and careful organisation on the day, which inescapably entered the conscious minds of participants during the events as well as in the assembling and dispersing, before and after. Many ancient Athenians, we can also be certain, knew that what was presented to them had passed through all the stages of approval that marked the formal acceptance of the completed work by the client who commissioned it: the city of Athens through its institutions. Indeed, many of the citizens had personally participated in these processes, with changing cohorts of citizens sharing a responsibility for the vision of the imagined city that was displayed and commended.

Individuals, and members of constituencies at a community-building festival, might display and perform their acceptance, but to suggest that they all always believed in what was ritually spoken and sung, or followed the advice of the appointed or elected officials, would be to risk confusing the implied with the historic viewer or assuming that the rhetoric was always successful in persuading those who received it. Such an approach also ignores or downplays the plentiful evidence for playing along, for scepticism, and for resistance, including the ever-present risk of the theft of valuables, despite the heavy penalties. What we can say with confidence is that participants knew that what they were offered, including the stories presented and the desired responses, had been officially approved and commended by the institutions of the city. As a society marked by a keen sense of rhetoric, it had little need for the modern concept of ‘propaganda’, often assumed to be a deception of those who receive it rather than as a reassurance to would-be conformists that what was offered had been officially ‘deemed’ to be true or right.2

On the Parthenon frieze, young women and men, seldom differentiated as individuals, are presented as carrying what appear to be containers of food and drink that, we can be confident, will also be consumed by the participants pictured in the composition in the forthcoming feasting. Others are leading large animals, notably much-prized heavy cattle and sheep, but no day-to-day items, such as rabbits or fowls, to be slaughtered in a ritual sacrifice. As part of such rituals, a share was invariably scattered or poured on to the ground as offerings to the gods, and although small as a proportion, the rituals themselves were sufficiently frequent to affect the local ecosystem of the Acropolis site and how it appeared both to participants and to observers within the local periphery. Indeed, the flocking birds were as much part of the Acropolis festival experience as the buildings and the people.3

The events shown are pictured as a series of episodes in broadly chronological order, like frozen frames in a film, that the viewers experienced either individually, or at the group level. They are guided by leaders (‘marshals’) who are directing the events and whose presence within the composition itself both helps viewers to see the images episodically and gives silent advice on what to expect. If a visitor or member of a festival procession attempted to see the whole frieze in chronological order, he or she would have had to break ranks and disrupt the implied script of a united community arriving at its ritual culmination.

When the marble blocks are rearranged in a gallery or in a book of photographs, the sense of encountering a succession of episodes is lost, and attempts to understand the ancient experience are made harder. However, even with the complete loss of large sections of the frieze, the export of many sections, the almost total disappearance of the colour and the metal, and the changes brought about by weathering, by casual damage, and, in the case of most of the pieces at present entrusted to the care of the British Museum trustees, by deliberate mutilation and whitening, there remain markers that, when situated within the discursive environment, can help to reduce the obstacles to understanding brought about by the many modern anachronistic intrusions into the strangeness.

The frieze was only comprehensible as a totality if the ancient viewers walked round the whole building. If they did so, negotiating any internal walls, gates, and guards, they would have had to choose whether to try to follow with their eyes the part of the procession that moved eastwards along the north side of the building or, alternatively, the other part of the procession moving in the same direction along the south side. Unless he or she doubled back after seeing one section and then started again, he or she would have had to view one of the two as moving in reverse. But however predisposed an ancient viewer might have been to regard the Parthenon frieze as an aid to imagining the invisible, it is hard to envisage anyone, even in a festival context, being so rapturously transported by the magnetic force running through the bodies of the hand-linked crowds as to be unaware that they were in a setting invented by human decisions.4

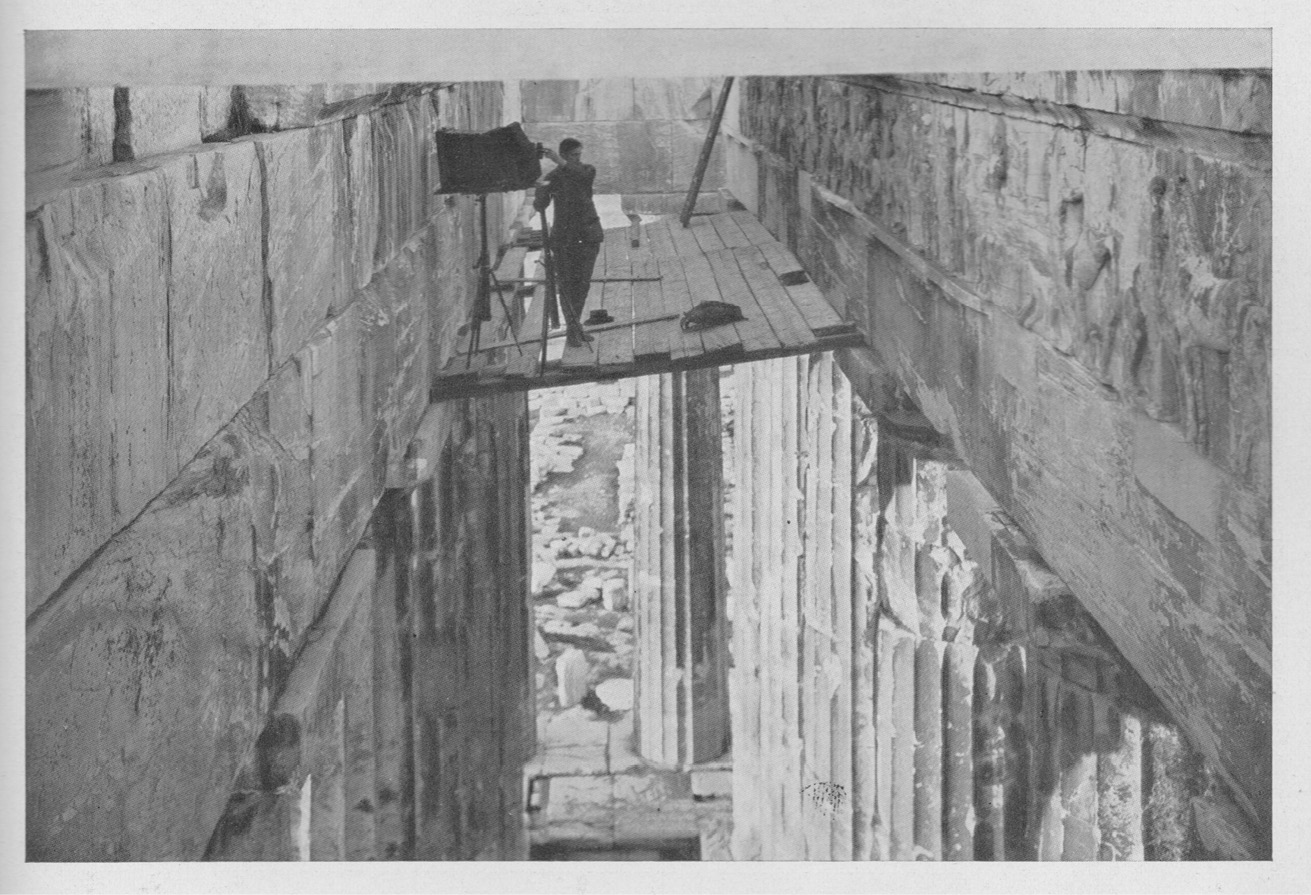

And here we encounter a problem. Those who have studied the sculptural components as objects to be subjected to stylistic analysis have found themselves withholding some of their usual admiration, describing the frieze, for example, as ‘decorative’, ‘ornamental, ‘repetitive’, ‘monotonous’.5 If, however, we regard the ancient viewer as at least an equal partner in the cognitive transaction with the ancient producer, we can see that it would have suited parties of ancient processioners and their guides to be able to halt simultaneously from time to time before an image of an episode.6 In ancient times, however, in sharp contrast with the easily visible pediments and metopes, it was hard for anyone looking up from ground level to see the frieze at all, let alone comprehend it as a unified composition. Indeed, only if viewers kept close to the steps of the building, or entered the tight Parthenon colonnade (assuming they were permitted to do so) and then stood still, could they make out much of the composition at all. Insofar as they were able to follow the frieze through the columns, it was as a series of episodes. The extraordinarily steep angle, around forty degrees, that any ancient viewer would have had to contend with in looking up at any section of the frieze can be seen from Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1. Walter Hege photographing the west frieze of the Parthenon, c. 1929.7

A photograph taken in 1900, one of the first to show the portion of the frieze on the building, as shown as Figure 4.2, gives an indication of the scale of the frieze when seen close up.

Figure 4.2. Looking at the west frieze in 1900. Photograph.8

It was this section of the Parthenon frieze, within the west porch, that the agents of Lord Elgin had been ordered to leave on the building by the Ottoman vizieral letter (‘firman’) sent at the instigation of the French Ambassador Brune, and that, as a result, now gives us and future generations the best chance we have of understanding the ancient experience.9

At the end of the twentieth century, when the air pollution and acid rain in Athens were severe, it was decided to bring the blocks of the west frieze indoors, replacing them with replicas. To the surprise of many, although damage had been done to the surfaces, the deposits of soot of recent times resting on older deposits had, to an extent, not only acted as a shield against erosion but brought out the sharpness of the carving, as shown in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3. The surface of part of the west frieze before the removal of the surface deposits. Photograph c. 1999.10

It is possible that, in ancient times, the oily deposits from the smoke of innumerable acts of burning the non-edible parts of sacrificial animals improved visibility from ground level. The removal of the surface deposits also showed how little the surface had deteriorated over the centuries. And it provided further proof that the frieze had been coloured, as shown in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4. The surface of part of the west frieze after the removal of the surface deposits, showing the remains of bright blue mineral. Photograph c. 1999.11

Some modern writers, aware of the difficulties faced by real ancient viewers looking up at a sharp angle, have suggested that it is ‘a mistake’ to think in such terms. Joan Breton Connelly, for example, has claimed that the intended and implied viewer was ‘Athena, not the human visitors’, giving renewed currency to what others had already suggested.12 However, there is little or nothing in the ancient authors or in the wider discursive environment to support this suggestion. On the contrary, with the Parthenon, as with other buildings, the ancient designers and the craftsmen that they employed were evidently aware of the need to help human viewers to understand the compositions as they were visually encountered at the steep angle.

Nor was the fact that offsets were routinely designed into buildings a secret or a guild secret. As ‘the stranger from Elea’, a character in the Platonic dialogue, The Sophist, points out, if the makers of visual images reproduced the true proportions: ‘the upper parts, you know, would seem smaller and the lower parts larger than they ought, because we see the former from a distance, the latter from near at hand’.13 Since the character of the stranger, who is introduced as an educated philosopher, presents his point as something well known, we can be confident that knowledge about offsetting from the orthogonal was routine and expected. Indeed, without such an understanding, the changing cohorts of Athenian citizens who served on the various commissions, including those with responsibility for the design, execution, and acceptance of building projects, would not have been equipped to meet the responsibilities laid on them. Since optical devices that help the ground-level viewer are employed in many other classical-era buildings besides the Parthenon, we can have confidence that the techniques needed for making images appear more convincing to the human eye than if they were produced orthogonally formed part of the training of the guild, passed on by experience and tradition from master to pupil, perhaps also with the help of written handbooks and treatises.14

When the pan-Hellenic site of Delphi was excavated in the nineteenth century, it was discovered that the marble slabs of the frieze of the elaborate Treasury of the Siphnians had been designed to tilt from the perpendicular, being wider at the foot of the composition than at the top.15 Some have thought that the same optical device was used in the frieze of the Parthenon.16 What is, however, apparent to any modern visitor is that the composition is more deeply carved at the top than at the foot of the slabs. As was noted by the late Martin Robertson: ‘a three-quartered face [is] given almost its sculptural value, a foreshortened foot hardly more than drawn in the marble’.17 The general effect, as had been noticed earlier by Charles Waldstein (later Sir Charles Walston) who conducted experiments in the nineteenth century, was to pull the attention of the human viewer upwards to the top of the composition, making it appear larger and more ‘realistic’ than it would have appeared if it had been carved to a uniform depth.18

The details of the carving become more visible to a modern viewer when the pieces are presented close up in a gallery, but they detract from attempts to understand the ancient experience. The hair shown on the displayed persons and monsters, for example, that could be seen ‘only as masses’ at a distance, when it is re-presented at eye-level, wisp by wisp, curl by curl, misrepresents the experience of the ancient viewers.19 The aim of the classical-era commissioners, we can be confident, was not to give ground-level visitors a technical lesson in how skilled craftsmen executed an intermediate stage of their work when the surfaces of the stones were being given their last touches before being lifted into their appointed place on the building, but to seduce the eyes of viewers towards a fuller appreciation of what they were being invited to think was there. In an age when alternatives can be offered with digital technology, it seems perverse to offer only a version that is anachronistic and therefore unfair to those who commissioned and executed the work.

When the carved front parts of the marble blocks are cut out and hung like pictures in a picture gallery, or when they are re-presented as a continuum in a book of photographs, they do not form a single narrative even within the sections where the composition is at its most simple.20 Some horses are presented as moving so fast that they would cause an immediate pile-up as soon as they reached the next horse. In some places the wind is shown as blowing so strongly that it causes the drapery of the costumes of the horsemen to stream out almost horizontally, but the cloaks of the adjoining horsemen on either side are unruffled. Seen through the columns, it was a series of discreet panels or episodes that the viewer might choose on focus on, as, for example, the breezes as among the features of the local microclimate.21

The events pictured are, in accordance with long-standing pan-Hellenic convention, evidently set in mythic time when, in contrast with the civic time of the classical era, men went naked or semi-naked, and women wore the clothes associated with festivals and ceremonies, and that were also presented in the words used in the tragic drama as normal in mythic times. Occasionally some mortals are shown as suffering the same mishaps as contemporary viewers, as, for example, in Figure 4.5, where one of the carriers has either stumbled under the weight of the heavy jar, or is resting, without breaking ranks. Some males appear to be carrying liquids in large jars balanced on their left shoulders, with others bringing goods that cannot be identified, in all cases invariably carried on their left shoulders.22 It is likely that the jars were understood by viewers as containing fresh water, for pouring as well as for drinking and that the basins were for ritual washing. On the mythic Acropolis, as on the real, water was always a precious commodity.

Figure 4.5. Carriers of liquids, and, on the slab to the left of the viewer, an unidentified box-like object. Photogravure made at eye level before 1910.23

Such touches offered a hint of realism, part of a general assumption, shared with the conventions of the tragic drama, that the mythic world was inhabited by personages who were subject to the same contingencies as the humans who observed and dramatized them. Such touches encouraged viewers to see themselves, or rather their aspired-to-but-hard-to-attain better selves, self-reflexively. The temple dedicated to Zeus at Olympia, which is almost contemporaneous with the classical Parthenon, shows one of the Lapiths with a cauliflower ear like a then-contemporary boxer.24 These details can be regarded as the equivalents in the static theatre of the Parthenon of the ‘signs’ that the character of the god Hermes in the Prologue to Euripides’s play, the Ion, mentions in encouraging the audience of the performed theatre to be alert to contemporary parallels.25

The Scene Above the East Door

The central slab on the east side, the culminating scene towards which both processions are moving, is the crux of one of the longest-running questions about the classical Parthenon. Figure 4.6, reproduced from a photograph taken at eye level before 1910 when the slab retained more of its surface than it does now, shows a scene that has caused puzzlement since it was first noticed by those who in modern times wished to learn about ancient Athens from a study of its standing remains.26

Figure 4.6. The central scene of the Parthenon frieze as presented above the east door. Photogravure made before 1910.27

In the eighteenth century the piece was built into the south wall of the Acropolis, facing inwards.28 And, from its sheer length, weight, and size, its importance as an extraordinarily large piece of the Parthenon frieze that had required extraordinary feats of quarrying, transportation, and engineering, was quickly recognized.29 Richard Chandler, for example, in many respects the best prepared of the eighteenth-century researchers, who saw it in 1765, realized that it was the slab that had ‘ranged in the centre of the back front of the cell’, that is, below the east pediment that, as Pausanias had reported, displayed scenes from the birth of Athena.30 Chandler could not, however, identify the event being pictured, suggesting that the display was of ‘a venerable person with a beard reading in a large volume, which is partly supported by a boy’.31 In the early 1750s, however, the architect James Stuart conjectured that the tall figure ‘is a man who appears to examine with some attention a piece of cloth folded several times double: the other is a young girl who assists in supporting it: may we not suppose this folded cloth to represent the peplos?’32

The question of which story was presented on the frieze has been a matter of speculation and contention since the eighteenth century.33 Among the suggestions that, in my view, are incompatible with the discursive environment are all those, such as the Stuart conjecture, that regard the frieze as reproducing pictorially a then-contemporary practice, such as the Panathenaic procession. Only a mythic story that looks back to a mythic past would pass the conditions applied to temples for hundreds of years across the Hellenic world. We should, I suggest, be searching for candidates from within the discursive tradition that shows an event already known to the main viewerships, and recognizable by them, as Loraux remarked, ‘without any hesitation’.34

A display of a peplos ceremony, even if thought of as idealized version set in a mythic past—an Ur-peplos ceremony—would have been so exceptional that it is unlikely to have passed unnoticed in the plentiful subsequent written record.35 To commemorate the establishment of a commemoration would, in the discursive conventions of the time, I suggest, be almost as much a breach as displaying the commemorative ceremony.

In recent times, too, even those who have felt obliged, for lack of any more plausible explanation, to accept the Stuart conjecture as updated, have found it ‘strangely anticlimactic’.36 To Robin Osborne, writing in 1987, the central scene was ‘an embarrassment’, only explicable, if at all, as a preparation for looking at something else.37 Some in the confident nineteenth century blamed the designers, which, since they assumed that the design was a matter for ‘artists’, implied that the Pheidias had misjudged. According to Thomas Davidson, even the best-known German scholars, Welcker and Michaelis, were of the opinion that the reason why the gods were presented with their backs turned was that the central scene was ‘not specially worth looking at’.38

Are there better candidates? Are we obliged, for lack of anything better, to accept that all these gods and heroes, men, women, and children, three hundred and seventy-eight personages in all, plus two hundred and forty-five edible animals, have been brought together just so as to be present when a piece of cloth made in a local workshop is ceremonially folded in order to be put away in a cupboard?39 The modern discussions too, that mostly take the Stuart conjecture as their starting point, have tended to suggest that ‘peplos’ is a term of art for the ceremony performed in the Panathenaic festival. There has also been modern writing about the alleged deep significance of the ceremony in the Panathenaic festival.40 In the usage of classical Athens, however, a peplos meant festival or ceremonial clothes as distinct from those worn day to day, as when, in the Suppliants by Euripides, the character of Theseus is surprised that the women who are in distress at not being permitted to bury their dead relatives, and are tearing their skin with their nails, are not peplosed.41 On an Attic funerary monument of the fourth century, a grieving widower, in praising the devotion of his dead wife to himself and to family values, declares that she was ‘not impressed by peploses or gold’.42 In the world of tragic drama, peplos could refer to the garments worn by a male, as when, in the Orestes by Euripides, the hero lies comatose after killing his mother and is described by the Chorus as coming back to life, stirring in his peploses.43 And it is the same sense of a large piece of cloth that might, or might not, be cut and worn that is employed when the character of Agamemnon, recently returned from sacking Troy, was stepping out of his specially prepared bath when the character of his wife Clytemnestra, all smiles, wrapped him in an embroidered peplos before murdering him.44

The ‘deep significance’ suggestion, leaving aside that almost everything about the Parthenon and the mythic stories it presented could be so regarded, was evidently contested. In Plato’s dialogue, the Euthyphro, the character of Socrates, who in the dialogue has already been indicted for spreading disbelief in the gods, is presented as confronting the credulous Euthyphro with the absurdity of believing that the story of the war between the gods and the giants is true. It also runs counter to the remark of Aelius Aristides that the peplos was an ‘ornament’ used in that festival, the Greek word (‘kosmos’) being cognate with that used for the ‘cosmetic’, that is, he remarks, was deemed (‘nomismatized’) to be symbolic by those observing the spectacle.45 In Xenophon’s Socratic dialogue on the management of the household (‘oikos’) and of the city (‘polis’) the character of Ischomachos is set up as exemplifying the arguments whose incoherence Socrates is about to expose. Dutiful and rich, a man who pays his taxes and contributes voluntarily as examples of his ‘charis’, to the cost of festivals, Ischomachos is presented as well satisfied with the education he gave his wife whom he married when she was ‘not yet fifteen’. Among the wifely qualities that he picks out for special praise is her care in looking after clothes and making sure that they are neatly folded away in the right places, along with ‘the things that we use only for festivals or entertainments, or on rare occasions’.46 That passage has been read as a comic exaggeration, although it need not be, but we can guess that if such a scene had been presented on the Parthenon frieze, it would also have raised wry smiles. The ‘deep significance’ of the peplos in the Panathenaic festival lay in the picture it exhibited, that is, as a reminder of the age at the beginning of the world when gods struggled with giants, one of a range of images that reminded viewers of an era when chaos reigned as were traditionally offered on Hellenic temples, such as the Telamons of Acrigas (modern Agrigento), and not in the soft fabric on which the picture was able to be carried and shown off by processioners.47

Can more be gleaned from the history of the slab in modern times? In 1801, acting under the authority of the Ottoman firman of May of that year, it was removed by Elgin’s agents from its then setting on the inside of the Acropolis wall. Although the agents were astonished and impressed by its size, they did not at first realize that, when on the building, it had displayed the culmination of the composition presented by the frieze.48 Since the slab was too heavy to be transported with the resources available to Elgin’s agents in Athens, mainly ships’ tackle, they had planned to cut it into two, but they seem to have changed their minds before the sawing was completed. However, as the slab was being moved, it broke down the middle.49 Both pieces, which were separately packed, were included among the cargo of the brig, the Mentor, commissioned by Elgin that sank near Cerigo (Cythera) in the Arches in September 1802. They spent some months on the seabed before being brought to the surface, and were then stored under a temporary covering on the beach, from where they were shipped in another vessel to Malta in February 1805, and later to England, where they were put in store again, and a few years later gathered into the Elgin Collection.50 If any paint or gilding had remained in Elgin’s day when it was removed, as is possible given that colour survived on the west frieze that Elgin’s agents had been obliged to leave on site, it is unlikely to have survived its months in the sea and on the beach.51 When the broken slab was reassembled on its arrival in the British Museum in 1817, besides the empty holes for metal attachments that are found on many other pieces of the Parthenon, the traces of rust were thought to indicate that the two personages presented on the central scene on the viewer’s right, had been shown wearing coronets or wreaths made of ferrous metal that had been painted or gilded, as is likely, from what we know of the general custom, to have been the case.52

An earlier photograph, made with a source of light that brings out more of the contours, is shown as Figure 4.7.

Figure 4.7. Detail from the central scene. Photograph made before 1885.53

With low relief, even small differences in the position of the source of light affects where the shadows fall, and therefore the modern viewer’s ability to re-imagine what was to be seen before the ancient surface was battered, bleached and stripped down to the layer below the epidermis of the marble.54

So how might the scene have appeared in ancient times? An example of looking at the slab through modern eyes, defended on the grounds that: ‘[T]he first law of iconography [is] that a depiction ought in some way to look like what it represents’ was provided by the art historian Evelyn B. Harrison in 1996.55 Harrison invited her readers to ‘think of yourself folding up a sheet after you have taken it out of the dryer’, noting that ‘if you have a little helper it will be easier to get the edges and corners even’.56 She also addressed the question of the sex of the young person pictured on the viewer’s right by looking at the surviving marble through modern eyes, suggesting, in leading a race to the bottom, that ‘the bare buttocks of the child are obvious enough to identify the figure from a distance as a boy’.57 When it was pointed out that in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York is a grave memorial to a girl shown in a similar pose that has been known since the eighteenth century, Harrison suggested, not without prudery, that on that piece, ‘the bare flesh is very discreet’, and ‘this child is alone with her pets in the sheltered courtyard of her home’.58

What we can say with confidence is that the smaller figure on the viewer’s right is wearing a peplos. Ancient costumes were mostly not tailored but consisted of a folded piece of cloth, sometimes pinned at the shoulder, as reconstructed from presentations elsewhere in Figure 4.8.

Figure 4.8. ‘Open peplos’. Wood engraving.59

The idealized female body presented by Athenian families in korai, the perfect ‘social body’ pictured on grave memorials, so that viewers can remember the dead at their best (or aspired-to best) is usually, in the case of classical Athens, physiologically young, with the shape of the back of the body presented in such a way that it is often impossible to tell from the surviving marble whether the figure was pictured as naked or as wearing a diaphanous garment that may have been rendered with paint.60 Nor need we exclude the possibility that the young men and women, the boys and girls, and even the gods and goddesses, who are themselves mostly shown in varying degrees of dress and undress, were designed to attract an erotic, including a homoerotic, gaze.61 Aristotle, discussing sexuality, says that a boy resembles a woman in shape.62 In the ancient romance known as Aethiopica, written much later but preserving older conventions, albeit in fictional form, and perhaps mocking the official values and verities, a father introduces his seven-year-old daughter, who is ‘as beautiful as a statue’ and appears to her male admirer to be ‘approaching marriageable age’.63 What Harrison regarded as an objection may instead be evidence that ancient viewers were being shown a mythic scene relating to the women’s sphere and to its rituals and customs.64

That an erotic gaze was discursively a valid way of generating extramissionary exchange with the imagined city emerges from an image of Aphrodite on the Acropolis, surrounded by scenes from olive cultivation and consumption, shown as Figure 4.9.

Figure 4.9. Aphrodite with Eros on the Acropolis. Engraving by Notor from a vase painting in the British Museum, not identified.65

Notor may have over-adapted his source. However that suspicion cannot apply to a key moment presented on the Parthenon frieze that shows the gods sitting in a circle going about their normal activities when Aphrodite, with Eros, turns away from the others to point to the central scene as shown in Figure 4.10.

Figure 4.10. Aphrodite and Eros pointing to the central event. Line drawing.66

These two images suggest that the passage in the Thucydidean Funeral Oration in which the character of Pericles advises his audience to learn to love Athens sexually, in accordance with the conventions, social hierarchies, and reciprocities noted and discussed in Chapter 2, was not an invention of Pericles or of Thucydides but part of the mainstream discourse, here shown visually, and would have been regarded as such by the Athenian viewer. So: what was the event that could turn the heads even of the gods?

As was pointed out, with some impatience, by a nineteenth-century scholar, there is nothing in the ancient authors to connect the Parthenon with the Panathenaic festival.67 Nor is the building alluded to in formal written compositions where we might have expected to find it mentioned, for example in the long Panathenaic orations of Isocrates or Aristides, nor in any description of the festival during the subsequent half-millennium when it continued to be celebrated. On the contrary, as many have pointed out, the scene displayed on the Parthenon frieze does not match what is recorded about what occurred in the historical Panathenaic procession. Where are the hoplites, where is the ship, where are the allies?68 Nor, when we read on an ancient public inscription how the duties were allocated according to ancient custom, does the washing and folding away of the ceremonial peplos, a commemoration of the establishment of a commemoration, to qualify for the place of honour.69

Far from being immediately recognizable by those who participated in the real event, it would have required an implausible stretch of imagination to see any resemblance.70

When we imaginatively restore the archaic costumes familiar from archaic korai, including the crowns, wreaths, and chaplets, the decorated garments, the nudity and semi-nudity and other markers that signal that a mythic scene was being offered to viewers, we should expect that what was presented on the central slab before it was stripped was more like the image shown as Figure 4.11, one of many scenes from myth pictured on ancient pottery. We have an opportunity then to imagine it bright with strange non-realistic colours and glittering in endless variations as the changing sunlight, and at some festivals the changing moonlight, was reflected from the metal.

Figure 4.11. Mythic scene with Pherephatta (‘Persephone’) and Triptolemos. Engraving of a vase painting, flattened.71

Can we find a local myth, preferably one recognized across Hellas, such as those shown on the metopes and the central figures in the pediments that ancient viewers might have expected to see shown on the Parthenon frieze? The suggestion that the frieze shows the sacrifice of the daughters of Erechtheus, made by Joan Breton Connelly in the 1990s and later the subject of her book-length study, is the only one offered so far that meets the requirement that what was pictured must be a scene from myth, which had evidently become as inflexible as the convention that only stories from myth should be allowed in the tragic drama.72 Connelly was the first to relate the composition to the speech in the play by Euripides, the Erechtheus (of which fragments previously unknown were first published in 1948, adding to a substantial passage already known) and to suggest that what is displayed is the sacrifice of the daughters of Erechtheus. In the story, Erechtheus, the king of Athens, surrounded by enemies, saves the city by agreeing to sacrifice his eldest daughter, and the other two daughters proudly offer themselves too. What is presented, according to Connelly, is the sacramental dressing before death.

Human sacrifice, a means of appeasing, or negotiating with, supernatural forces, is common in Hellenic myth, Iphigeneia being the best-known example—and she was among many mythic characters whose actual tomb was allegedly situated in Attica—but human sacrifice is to be found in other religions practised in the Eastern Mediterranean region, with many instances found in the archaeological record, including some from prehistoric Greece. Connelly’s conjecture, however, although the most plausible offered so far, has its own difficulties. The speech includes many of the features of the emergence-from-brutishness narrative familiar from the version offered by Thucydides; for example, that the inhabitants were only able to remain autochthonous because Attica, having poor-quality land, was not resettled as a result of successive conquests, re-conquests, and re-settlements, which are compared to moves in a board game, implying, as Thucydides does, that no justification other than a wish to seize ‘useful things’ was needed in mythic times. The passage reports the transition to living in families in an oikos-based economy, an episode in the brutishness narrative of which examples of the different stages were observable across Hellas and beyond. The speech includes a comparison with those brutes that have a well-developed culture, in this case, with bees. There is an emphasis on the mutual obligations of ‘charis’ that are directly linked with the mutual obligations of children and parents, with the word in its cognates being repeated in the same line, as ‘useful’.73 In all these respects, the Connelly conjecture meets expectations of what might have been offered to the viewer to picture and animate in his or her imagination. However, the notion of human sacrifice would set the occasion as a stage in the brutish narrative that had long been superseded. And there are remains of a countering speech to the anti-immigrant rhetoric that we would expect in a dialogic text, with its metaphor from the building industry, as when the character of Praxithea, the mythic queen, declares: ‘a person who moves from one city to another is like a peg badly fitted into a piece of wood, a citizen in name but not in action’.74

The story of the Eumolpides, one of the eponymous families by which the classical city was politically constituted, and among the core corpus of Athenian identity-constructing myths, grates in a community-building context. It would have had to be presented by the guides as a step in the brutishness narrative that, in the drama, was brought to an abrupt end when Athena causes an earthquake. Lycurgus, the orator, whose works have been preserved as examples of the arts of persuasion used in schools of rhetoric, who quotes the passage from the speech in making the case against a man on a capital charge of deserting Athens in its hour of danger, refers to it as having been ‘composed’ by Euripides, with the implication that the playwright had invented a variation.75

Although, in one sense, the saving of the city by a human sacrifice may be an event to be celebrated, it was also a horror to be mourned. In the Agamemnon by Aeschylus, the character of Iphigeneia does not go willingly to have her throat cut by her father, but protests and resists. And the Chorus, when inviting the audience to imagine the scene, refers them to ‘pictures’, appealed to as normalizing and legitimating that reaction—but the one visual image that has been found offers horror, not honour.76 Nor does the character of Iphigeneia go willingly to her death in the Iphigeneia in Aulis by Euripides.

Moreover, in the rest of the composition of the frieze with which ancient viewers were presented, there is little to suggest an act of impending heroism. The figures identified as the Eponymous Heroes, who flank the gods on the east side, wear sandals and cloaks, an informal dress usually a sign of having travelled from a distance.77 They stand around, apparently chatting, scarcely appropriate for the imminent judicial killing of the three most highly privileged young women in the mythic city.78 Although twelve, invisible, deities are shown seated, six male, six female, they are not the twelve Olympians. Hestia, the goddess of the hearth, whose role is to stay at home when the other gods go out, is omitted, her place being taken by Dionysus, the god of festivals.79 Athena has taken off her helmet and left her shield behind. Described by the late Martin Robertson as ‘relaxed and informal’ and as having a ‘casual gossipy air’, the gods do not evince the solemnity required at a human sacrifice intended to placate their wrath.80 Under the Stuart conjecture, what the female figures are carrying on their heads are cushions brought by slaves or temple servants, as they may appear to modern eyes, but scarcely, in ancient terms, worth noticing, let alone assigned spaces of honour on the most significant story pictured on the whole frieze. Under the Connelly conjecture, they are the shrouds of the daughters of Erechtheus who are about to die for the city. If, however, as I suggest, the ancient Athenians were being shown a scene of joy, the objects are gifts appropriate to a mythic rite of celebration, such as are shown as Figure 4.12.

In a telling detail, Aphrodite and Eros are shown pointing to the central scene, a neat example of how presenting the viewer in the picture can not only direct the gaze of the viewer but, as on the west pediment, recommend the appropriate response. None of the women are presented as having cut off their hair as signs of impending mourning. The horsemen have not cut off the manes of their horses, as was the custom in the mythic world as presented in the tragic drama, and the manes stream conspicuously behind the horses as part of an illusion that they are moving.81

Figure 4.12. Woman carrying a basket on her head. Engraving.82

In the modern tradition, the naked and semi-naked horsemen are commonly said to be ‘cavalry’, but no weapons are depicted.83 The fact that many are presented as naked by itself rules out any suggestion that a contemporaneous event is being pictured.84 The horsemen display so wide a variety of combinations of dress, including of headgear and footwear, as to suggest not uniformity but diversity. If they were intended by the ancient designers to be seen as cavalrymen, they are not on duty.85 As Thucydides says explicitly in his account of the Athenian development from brutishness, the decision not to carry arms, in which the Athenians of the past had set an example that others later followed, was only made possible by the trust that had been built up.86 These features, taken together, we may reasonably conclude, not only signalled that viewers were being offered a procession on a non-military occasion, but that they asserted the values, including the practical usefulness, of the internal civic peace and mutual trust that Athenian civic and personal paideia was intended to promote.

So can we find another candidate that fits, in Connelly’s phrase, the ‘ultimately genealogical function of architectural sculpture’ and that ‘demands the telling of local versions of myths, grounding the formula in specific landscapes, cult places, family lines, and divine patronage’?87 A point that has seldom, if ever, been noticed is that, whichever authority it was that first arranged for the huge central slab to be removed from its slots on the Parthenon without breaking it, performed a complex feat of engineering, almost as impressive as that of the ancient builders who raised it into place in the first place. The modern suggestion that such a long slab could have ‘fallen to the ground’ whether accidentally or deliberately brought about, accelerating through a drop of nearly forty feet, without breaking up on impact, is next to impossible.88 When that dismantling occurred is not noted in any surviving literary or epigraphic record, although a technology already exists that will enable the dates of breakage and mutilation to be estimated with greater precision, for example to the nearest century, and could be proposed as a project to the authorities responsible for the site.89 From recent studies of the stones, it is already almost certain that this slab was taken down and repositioned at the time when the ancient Parthenon was adapted for use as a Christian basilica, sometime in the middle centuries of the first millennium CE. It is likely that the dismantling occurred at that same time as the changes authorized and financed by the ecclesiastical authorities, that the door at the west end, which had previously been the entrance to the part of the building, normally shut, where the city’s possessions were kept secure, became the entrance to the building, having being adapted to receive a congregation inside and to align it along a Christian axis. At the same time, again in accordance with a top-down empire-wide decision to bring Christian ritual practice indoors, an apse was built into the east end, making the removal of the huge central slab of the frieze architecturally unavoidable.

The slab was, however, not actively destroyed, nor treated as marble waste to be recycled as building material, as seems to have happened with the private dedications on the Acropolis at that time. A more plausible explanation is that it was carefully taken down and then systematically mutilated, as had been the custom of the Romans and occasionally in classical Athens. In this case, as with other parts of the Parthenon frieze and figurative sculpture found in sanctuaries all over the ancient world, the mutilations were not intended to destroy the artefact outright and so remove it from the built memory altogether, but to commemorate the act of mutilation itself. The intention was to display to members of the then newly triumphant religion, and to others who might not have actively wanted to be Christianized, the fact that the ‘idolatrous’ images which their ‘pagan’ votaries had allegedly ‘worshipped’ had now lost their power. To these men, the Parthenon was, in modern terms, a dark heritage, that had a value as a building that made it worth preserving, but only provided it no longer exercised the power to persuade that it had done in former, now happily superseded, centuries.

When the piece was examined in preparation for the first formal publication, the museum managers thought that ‘the heads of these figures, as of almost the whole line of the [east] frieze, appear to have been purposely defaced’.90 The care given to the taking down and selective mutilation can be regarded as part of the slow, long-drawn out, step-by step, top-down policy of imperial Christianization.91 Paradoxically, if this is what happened, it has not only brought about the survival of the slab but has had the incidental result of enabling us to offset the damage that was done at that time. We can also offset the distortion of presenting the composition at eye level. A recent photograph, as shown as Figure 4.13, taken from a more oblique angle, shows a bulge more clearly.

Even without the adjustment to the viewing angle, it is implausible that the lump of mutilated marble at the top of the composition is the left hand of the central male figure as many have assumed.92 If that had been the case, the left arm of the adult male figure under the cloth would be grotesquely long, and the knuckles of the hand implausibly disproportionate, even if some allowance were to be made for helping the ground level viewer. Nor is the lump likely to be some disproportionately large piece of a frame positioned in the most central spot of the central composition to which all eyes are drawn.

Figure 4.13. Detail of the slab in its state at the time of writing. Photograph by author taken from an oblique angle. CC BY.

As was pointed out in the nineteenth century, the action assumed by the Stuart conjecture to be the handing over a piece of cloth by the smaller figure to the tall bearded male figure on the viewer’s left is better seen as the man who is looking at the viewer as he hands over or accepts something wrapped in the cloth to or from the smaller figure.93 In 1975, the late Martin Robertson suggested that what was wrapped in the cloth might be the image made of olive wood (‘xoanon’) that had allegedly fallen from the skies at the time of Erechtheus. But, like the Stuart conjecture, it is open to the objection that it is not a mythic event.

When we adjust the viewing angle, the lump of marble becomes the feature of the composition to which the eyes of viewers are drawn. As Waldstein had noticed in another context, once we offset the distortion brought about by presenting the piece at eye level, the effect is to draw the eye of the viewer upward. From the most common angles at which the composition was seen in ancient times, that is, all those other than full frontal, the central male figure, even in its mutilated state, appears be looking at the viewer, exhibiting to him and her the object under the cloth, a pose encouraging the reflexivity that is to be expected in the central action of the composition of the frieze. A co-opting stance of this kind can be seen in Figure 4.14, a photograph of a plaster cast that also preserves only the contours of the marble sub-surface as it has come down to our time.

Figure 4.14. Cast of the central scene, Acropolis Museum. Photograph by the author of a cast taken from an angle, June 2018. CC BY.

The cast also preserves a line of holes, whose purpose is not clear, but which, if they are the remains of coloured ceramic studs of the kind that were prominent on the Erechtheion nearby, would have indicated to the ancient viewers both the shape and the importance of the covered object that is being displayed to them by the male figure. And, even in its mutilated state, and after over a thousand years without maintenance, unsheltered from wind and weather, and its surface cleansed by its months in the sea, the exposed marble subsurface may still retain traces of other identity markers. The figure on the viewer’s right, for example, appears to be shown as wearing something on her wrist that was so pronounced that it has been picked out in marble and not just in paint or ceramic. The raised lump may be a survival of the ‘golden snake’ that was worn by those women of Athens who belonged to families who claimed to be autochthonous.94 The puzzling incisions to the neck could be the remains of a golden snake necklace that, as is noted in the Ion, served the same identifying purpose.95 If the heads of the older men depicted on the frieze had survived in better condition, with their paint and metal, it might have been possible to find traces of the golden cicadas or grasshoppers that Thucydides and others say were worn in the hair by old-fashioned Athenians as symbols of their Ionianism.96 Among the objects listed in the inventories of valuables held in the Acropolis temples, alongside the special clothes, wreaths, brooches, necklaces, and other paraphernalia used in festivals, are golden grasshoppers.97 Whether they were made available to temple servants (‘priests’), male or female, or to other participants in festivals in which Ionian kinship was remembered and re-enacted, is not recorded but seems likely.

The object wrapped in a cloth is, I suggest, a baby tightly wrapped in swaddling bands, a public display of a custom known to every Athenian family, even if not always practised.98 Among the tens of thousands of visual images surviving from the ancient world, not one has been found that shows a man and a young person folding a piece of cloth.99 By contrast images of tightly swaddled babies, of which a typical example is shown as Figure 4.15, are common.

Figure 4.15. Grave memorial apparently of a woman who died in childbirth or soon afterwards handing over the swaddled baby to be cared for by another woman. Author’s photograph. CC BY.100

According to Hippocrates in his treatise on how climate, diet, and social customs affect the character of a people, those babies who were not swaddled were likely to grow up to be flabby, squat, and impotent.101 In Plato’s ideal state it was to be laid down in law that a child should be swaddled, ‘moulded like wax’, until the age of two, and to be carried by their nurses till the age of three to ensure that their legs were straight.102 To present a baby tightly swaddled was therefore itself a recommendation to viewers, female as well as male, on how they ought to bring up their children to become useful to the city. Images of tightly swaddled babies made from terracotta, a material associated with personal votive offerings, look much the same.103 Although there are innumerable presentations of actual swaddling both in words and images over many hundreds of years, making it one of the most enduring and recognizable components of the discursive environment, only one image of an event set in the mythic age is known to me. Shown as Figure 4.16, as noticed and copied by Winckelmann, it is thought to picture the birth of Telephos and may refer to the play by Euripides, of which some fragments survive.

Figure 4.16. Birth of Telephos, , facsimile of an engraving from a bas relief in the Villa Borgese, with a similar image depicted in a mural from Heculaneum that was moved to the Museo Archeologico in Naples.

The image, which appears to present the pregnancy of a mother and the presentation of the swaddled child, ‘scenes from the birth of Telephos’, shows the infant with even its head tightly swaddled, wrapped in a large peplos, as it is ceremonially handed over and accepted. What was shown positioned under the pediment that presented scenes surrounding the birth of the Athena, I suggest, were episodes relating to the birth and naming of a famous mythic child. Indeed, since both pediments offer myths of eponymous naming, we might even have guessed that the frieze would do the same.

In the custom of classical Athens, there was a time gap between the physiological birth of a child and the ceremony of accepting it as a member of the family.104 Although there are differences in the record, it appears that on the fifth day, the nurse, in the presence of close family members, carried the infant round the family hearth in the middle of the room, hence the name ‘amphidromia’, literally ‘walking round in a circle’, a custom so well known to contemporary Athenians that the character of Socrates, in Plato’s Theaetetus, used it to explain his method of arguing as a circular process.105 On the tenth day the child was formally named. During that interval, from which males appear to have been excluded or to have excluded themselves, the baby was without identity, born physiologically but not yet socially.106 One of the characters of Theophrastus, commonly called ‘The Superstitious Man’ but perhaps more accurately rendered as ‘the man who pays excessive attention to customs’, refuses to visit a woman when she has given birth for fear of pollution, which he regards as equivalent to the prohibition on touching a dead body.107

Nor was the interval between physiological and social birth a formality. Exposing an unwanted child to die seem to have been legal and acceptable during the first days of a child’s life, both on grounds of physical unfitness, if, for example, the infant exhibited a disability, and also on moral and social grounds, as would be the case, for example, if it was not born legitimately according to the city’s norms.108 In archaeological excavations in the Athenian agora in the 1930s, a well was discovered near the so-called Theseion that contained the skeletal remains of about four hundred and fifty children as well as of dogs. Although dated to the Hellenistic period, it appears to give confirmation that infanticide whether active or passive was practised in Athens, as well as in Sparta, and probably in other Hellenic cities.109 The autochthony claimed by certain Athenian families was not only a discourse, but ensuring racial purity was a current social practice.

When, however, as I suggest is the case here, the birth is entirely legitimate and a source of family and social celebration, the giving of gifts, of animal sacrifices and feasts, a birth scene fits well with the general storytelling function of the Parthenon and of the site. In Aristophanes’s comedy, the Birds, the character of Euelpides, who boasts of how Athenian he is by birth, complains that his cloak was stolen when he was drunk at a tenth-day naming party. The dramatic purpose of the remark in the context of the play, other than to imply that Euelpides is a free-loader, is not obvious since it hangs without further explanation or follow up. The anecdote may have had a topicality not now recoverable, but its presence in the play shows that naming parties were a normal part of life in classical Athens.110 Nor should we assume that kinship festivals took second place to civic, nor that attendance was optional.111

In the Birds, Aristophanes includes a parodic description of a naming ceremony with its procession, whose comic potential is exploited to great effect. Although it is usually overambitious to infer actuality from comedy, it is striking that when the scene is introduced, the first things that are called for, which serve as markers for the audience of the play, are a basket and a washing basin, both of which are presented among the objects being assembled on the Parthenon frieze.112 In the Clouds, we are given a comic conversation between the character of Strepsiades and his wife about the choice of names and how the child would be affected by the alternatives.113 At the naming ceremony, a birth tax that can also be regarded as a registration fee, consisting of a quart measure of barley and another quart of wheat, plus one obol in cash, was also payable by the father, as it had been since the age of the tyrants, so turning the ceremony of acceptance of a child into a public civic duty. The same tax was levied at death, so marking both the entrance to and the exit from the status of Athenian citizen.114

Figure 4.17, a detail of a nineteenth-century sepia photograph of an unidentified funerary monument appears to show a woman who has died soon after giving birth handing over responsibility for the infant to surviving family members. It conforms with a common theme, but also, unusually, provides visual evidence for the practice of swaddling an infant’s head in order to turn him into a ‘long-head’ like Pericles.115

As Figure 4.17 showed, head swaddling was also presented as occurring in the mythic world. Although my suggestion does not depend upon the point, I note that if the image of the swaddled baby in the central scene of the Parthenon included such a head covering, it would situate its head even more prominently in the composition as seen by viewers looking up, and make it an even stronger candidate to be mutilated. The same would be true of any other head-dress that acted as a marker.

Figure 4.17. A swaddled infant with a conical head covering. Detail from a nineteenth-century sepia photograph, perhaps by Constantinos, of a grave memorial in high relief.116

So, if viewers of the Parthenon were being shown a mythic baby being accepted into the community of the city, who is being pictured? One candidate jumps to mind. What was being shown, I suggest, are ‘scenes relating to’ the birth and naming of Ion, to adopt the phrase used by Pausanias for the stories presented by the pediments, ‘birth’ being understood as the social birth that did not occur until the naming ceremony. Ion, the eponymous father of all Ionians, was one of the most ancient of Athenian heroes, being mentioned in the eighth century in Hesiod’s Catalogue of Women in a fragment not discovered till the twentieth century, and with an apparently unbroken tradition for over a thousand years.117 According to Thucydides, the Ionian descendants of the Athenians who lived in Athens continued in his day to celebrate their (kinship) connexion annually on a special day in the month of Anthesterion as part of the ‘ancient Dionysia’.118 My suggestion therefore fits well with Nicole Loraux’s suggested requirement, as well as that of Connelly already noted, that the mythic stories, if they were to fulfil their purpose, had to be recognizable by Athenians ‘without any hesitation on their part, as if these identifications were self-evident’.119

The suggestion, unlike those suggested by others, is fully in line with the rhetoric of the building as a whole and with the discursive environment. Besides the allegedly welcoming attitude to foreigners presented by the character of Pericles in the Thucydidean funeral oration, there is plentiful evidence of a fear of hybridity.120 To reassert the common kinship and the mutual obligations through the mythic figure of Ion was therefore not just a useful old story alongside others in the mythic past of Athens, but, as was the case in some tragedies, one with topical relevance. As Lisa Kallet has remarked about the classical period: ‘They [the Athenians] also, through an increasing cultivation of the hero Ion and an emphasis on their connection to Ionians, marketed themselves as the mother city of all Ionians’, an observation well attested in the contemporary authors who described the institutions of the classical city, the claims to antiquity, and the use of eponyms.121 And her comment is amply borne out not only by the experiment that brings out the plentiful references to Ion in the discursive environment, but by much other evidence. It was part of their self-fashioning that the Athenians were themselves Ionians, and that overseas Ionians as their ‘children’ owed them obedience, especially at a time when the original Ionians, the Athenians, had saved them in the still recent unsuccessful Persian invasion.122

But a presentation of scenes surrounding the birth of Ion offered even more. One of the biggest, the most regular, amongst the most ancient, and, at three days, the longest-lasting of all the festivals, the pan-Ionian Apatouria, which occurred in various sites in Attica every autumn, was not only a celebration of kinship, but the administrative occasion when new members were formally enrolled.123 Although there appears not to have been any age limit after which a boy or man could not be enrolled, most enrolments appear to have been of infants born to the legitimate wives of existing members in the previous calendar year. The naming and enrolment displays not only enabled boys to proceed through later rites of passage to the privileges and duties of citizenship, but they determined private property and inheritance rights far into the future. As emerges from the corpus of legal speeches of the fourth century in which the details of the induction ceremonies were put under scrutiny, naming and enrolment were amongst the instruments by which the inter-generational continuity of the city was celebrated and performed.

Once modern assumptions are discarded and the lost paint and metal restored, the smaller figure can emerge as the mythic Kreousa, mother of the eponymous Ion. Since it is a social birth that is being celebrated, not the physiological, she is pictured as a girl at the moment of transition to adulthood, as an ancient viewer would recognize.124 And the male figure who is accepting the baby into the family can be identified as Xuthus, the husband of Kreousa, whose memory was also honoured in recurrent ceremonies, as testified by a fragmentary inscription of c. 430; one of many that regulate the calendar of sacrifices, it notes that an Attic ‘trittys’, one of the large constituencies of citizens into which the population had been divided in 506, records a duty to sacrifice ‘a lamb to Xuthus’.125 As for the female figure to the left of the tall male figure, she may be formally receiving the gifts associated with a naming ceremony, some of which are mentioned in ancient authors, brought to her by female kin and friends holding trays on their heads.126

Recovering the Ancient Meanings of the Ion Myth

If my suggestion is valid, can more can be said about the way the stories were likely to have been understood by real Athenians? Although the Parthenon frieze was part of the background experience of those participating in rituals on the Acropolis for around a thousand years, not a single author of the surviving corpus makes even a passing reference to it in the terms used by modern histories of sculpture, or even in those used by Pausanias as a collector of stories.127 However, there are some indirect indications. In listing the benefits that a mother can give to her daughters that will be precluded by her voluntary death, for example, the character of Alcestis, in the play by Euripides of that name, declares that attending them in childbirth is the most caring.128

And we have a few reports of critiques of the discourses of autochthony and Ionianism. Antisthenes, for example, a learned and prolific author and friend of Plato, had a personal reason for resenting the backward-looking nativism of the two-parent decree. Although born in Athens, his mother had been born in Thrace, and he was therefore barred from participating in many aspects of public life, including speaking in the Assembly.129 He was ‘Attic’ but not ‘Athenian’. His sardonic remark that moving from Athens to Sparta was like moving from the women’s quarters to the men’s, a variation on a standard theme that Spartans were more manly than Athenians, is more pointed if he is alluding to scenes relating to the birth of Ion.130 And when he said, in a sardonic phrase that owes its survival to its having been adopted as a moral tag (‘chreia’), that the only autochthonous creatures on the Acropolis were the snails and the grasshoppers/cicadas, he was referring both to the creatures that appeared to hatch spontaneously and to the golden grasshopper brooches of the ‘old Ionians’ who wore them.131

As Jenifer Neils has pointed out: ‘images of youths carrying troughs or baskets are not common’.132 And the suggestions for what the receptacles might have been understood by viewers to contain, for example honeycombs, as well as other free-standing items, have tended to start from descriptions of the Panathenaic processions, despite the lack of any correspondence with what is pictured on the frieze in any of the main features. If, however, we start instead from a hypothesis that what are presented are scenes from the naming of Ion, in which all the elements presented are immediately recognizable as following the normal Athenian practices of birth ceremonies, the youths are explainable as male guests bringing gifts. Athenaeus, a later writer who gathered stories about the lore of food, preserves mentions of the customs of the naming festivals that he had extracted from works now otherwise lost: the Geryones by Ephippus; the Parasite by Antiphanes; the Insatiable Man by Diphilus; the Palæstra by Alcæus; and the Birth of the Muses by Polyzelus.133 We also have a papyrus fragment that may come from the tragedy of Aeschylus known as Semele, or the Water Carriers, which seems to have been enacted by the Enneakrounos (‘Nine Channels’) spring.134 The ceremony of inducting children into the community, real and imagined, by washing them in the local source of fresh water, thus linking them securely to the life-giving earth, is recorded for several ancient Greek cities, including Argos and Thebes, as well as for Athens. As familiar to every Athenian family of the classical period as the practice of swaddling new-born babies, it is referred to by Thucydides, and given authority by being pushed back in time to the heroic age as already noticed.135

Although there are many descriptions in words, visual images of the ceremony are rare. One, evidently drawing on a Greek model, was seen and pictured by Winckelmann in the collection of Cardinal Albani, as shown in Figure 4.18.

Figure 4.18. ‘Bacchus raised by the nymphs of Dodona’. Engraving.136

If my suggestion is right, how should we regard the Ion, the play by Euripides? The first public production, which depended upon its having passed through the stages of obtaining approval and financing required of all works entered for dramatic festivals and competitions, can be reliably dated to some time in the latter part of the mid-fifth century when the main plans for the Parthenon had already been approved and some of the actual construction work had begun and perhaps been completed.137 Since Euripides’s career as a dramatist began in 455, there is no problem in relating one of its themes to the Periclean two-parent decree of 451/450. How, we can therefore ask, would an early audience of Athenians have regarded the play in the circumstances in which it was first performed?

In the play, a male baby who was found abandoned by some unfortunate local girl outside the perimeter of the holy site (‘temenos‘) of Delphi, is taken in by one of the female temple servants, out of kindness and against the regulations, itself a critique of convention. Gradually the child learns to survive by living off scraps from the sacrifices. As he grows into a boy, he makes himself so useful by doing odd jobs that he is given permanent employment. Among those whom he meets as he goes about his temple duties is Xuthus, husband of the Kreousa, daughter of King Erechtheus of Athens who has come to seek advice. After many unexpected twists, it turns out that the boy is the same person as a baby whom Kreousa bore in secret in a cave of the Acropolis slopes and then she abandoned. When the boy’s true history is eventually discovered, he is given his name ‘Ion’ in a belated ceremony, and taken to Athens where he is installed as heir to Xuthus and awaits his destiny as founding father of all Ionians.

My suggested answer has used the Ion as a source for contemporary Athenian customs of the classical era, such as the gold rings, bracelets, and other markers that signalled to viewers that a woman was from an autochthonous family. My suggestion is not however that the story offered on the Parthenon frieze shows any moment, episode, or set of scenes in the play, something we should not expect. It does, however, fit well into the discursive environment. Indeed, it fills a gap in the array of stories that my experiment suggests demand to be given prominence on the Parthenon.

As was common in the Athenian tragic theatre, especially in the plays of Euripides, the Ion took the myth in a new direction while maintaining many features of its predecessors. In the world of myth, it was not uncommon for characters to be abandoned as infants, brought up by shepherds or animals, and eventually recognized and either rehabilitated into a normal social hierarchy, or, as in the case of Oedipus, made to confront an unwelcome truth.138 In the Ion, Euripides offered a plotline full of mistaken identities, plans to kill family members, and of death by stoning narrowly averted. The drama, a work of astonishing poetic power and of narrative complexity, is held together by fantastical coincidences and by no less than three instances of dramatic reversal, of ‘peripateia,’ defined by Aristotle, who may have coined the term, with the peripatos road round the Athenian Acropolis in mind, as ‘a change by which the action veers round to its opposite, subject always to our rule of probability or necessity’.139 The skill of the playwright, presenting within a genre that in modern terms is more romance than tragedy, and that was shared with the implied and the actual audience, enabled the interlocking complexities and instances of implausibility to be fitted into the complex formal structure demanded by the rules of the dramatic festival competition into which the Ion was entered.140

In the Wise Melanippe, an earlier play by Euripides, of which fragments survive, the eponymous heroine notes, as an incidental contribution to the setting of the scene, that Ion had been born in Athens to Kreousa and her foreign-born husband Xuthus.141 Indeed, in the new play, in order to display and draw attention to the change being made from the version of the Ion myth known to and expected by the first audiences, Euripides included a summary of the older version in the Prologue where it was reported under the allegedly unquestionable authority of the god Hermes and of the Delphic oracle.142

As a story, the Ion elaborated what had hitherto been an unremarkable foundation myth of a child born to a Athenian mother, Kreousa, and to her husband, the military hero Xuthus, into one in which Ion implausibly turns out to have been fathered by the god Apollo, Kreousa having been impregnated against her will outside the Cave of Pan on the north slope.143 In the Ion, as the story was recast, Ion therefore eventually turns out be Athenian by both parents, and to conform with the Periclean two-parent decree of 450, assuming that Apollo is a deity closely although not exclusively associated with Athens.

By the end, the mythic eponymous hero Ion has been culturally reconstructed to be in full compliance, with implications not only for his exercise of citizenship in the male public sphere of speaking in debates, participating in elections, and in his eligibility for holding public offices, but in the private and family sphere, especially in questions relating to inheritance. As Gunther Martin has written, the character of Ion ‘who was formerly only half Athenian is turned into a “pure” citizen’.144 And, as the character of Ion himself makes explicit, before he knows about the soon-to-be revealed circumstances of his birth and upbringing, if it had not been for the unexpected change in the story of his birth, he would be excluded from participating in public affairs. His tongue, he says, would have been enslaved.145 If he did not satisfy the two-parent rule, he could not have passed the test set at the Ionian-wide festival of the Apatouria at which his name would be voted on and registered on a citizen list (‘phratry’), a rite of passage that, for most male children occurred in their first year of adulthood but that had no age or time limit.146 One of the many ironies in the old Ion story, which Euripides has the character of Ion himself point out, is that after the two-parent decree, Ion was not even an Ionian.147

The Ion concludes with what Gunther Martin has called ‘a glorifying twist’ that asserts that all Ionians are the descendants of the autochthonous citizens of Athens, a point about an aspired-to future already trailed in the Prologue.148 The implication is that the Ionians overseas, as ‘kin’ of the Athenians, owe obedience to the largest city in the Ionian world, a staple of the discursive environment. However, before the play reaches what Donald J. Mastronarde has called its ‘veritable orgy of imperialistic genealogy’, it has performed another function of the Athenian tragic drama. In a series of exchanges, the characters question the credibility of the implausible narrative of a series of events that the audiences, and later the readerships, of the play were being invited to believe. Surely Kreousa’ s story that she had been raped by a god, the character of Ion suggests, was just a tale commonly invented by women who become pregnant in circumstances they are unable or unwilling to explain?149

The women viewers of the frieze on the temple at Delphi were wrong to trust the stories and songs that they had heard from other women as they worked at their looms.150 The knowledge of the future supposedly obtained from scrutinizing the entrails of sacrificed animals and bird omens is unreliable.151 What the gods allegedly tell humans through the medium of the Delphic oracle also turns out to have been untrue.152 With example after example, the characters in the play are presented as losing their confidence in the ways in which Athenians had been officially taught to regard their city.

The character of Kreousa presents herself as a victim of gender stereotyping when she asserts that women are all treated in the same way by men. But shortly afterwards her husband Xuthus not only declares that he is not interested in who was the biological father of Ion, whom he intends to treat as his son and heir, but shows himself to be considerate of Kreousa’s feelings. Indeed, some audience members might have thought, he is remarkably forgiving of a wife who, in an earlier scene, had intended to kill him.153 And not only is gender-stereotyping critiqued as a two-edged weapon. When the generous-minded Xuthus, in deciding to accept the temple boy Ion as his son and heir, reaches out to touch him as a member of his family, Ion thinks he is being subjected to a homoerotic advance and has to be reassured that, in this case, his normally useful working assumption did not apply.154

When the character of Ion, in repeating the official civic ideology of autochthony, says he was ‘born from the earth’, the character of Xuthus tells him that the earth does not give birth to children.’155 In affirming his belief in the autochthony myth, the still un-disillusioned character of Ion quotes, as his evidence that the stories are true, the fact that they are validated by ‘pictures.’156 There are other examples in classical Athens of images of the half-man, half-serpent creature that personified autochthony, but none was more often seen nor more officially normative than the so-called Cecrops group presented on the west pediment of the Parthenon and on the base of the more rarely seen cult statue inside. If so, we have another example of the custom of inserting features of the classical-era built landscape into the mythic age of the tragic drama, and also of how, as with ‘the gods’, that does not shield them from discursive assault. By using a cognate of the Greek word ‘nomizo’, the character of Ion implies that the mythic stories and the gods that people them are also fictions, socially useful for those who benefit, but with nothing intrinsically valuable supporting them, other than the misplaced belief that they are true which is conventionally accorded to them.

There are other passages in the play in which the nature of what should count as evidence is discussed, drawing attention, for example, to the absurdity of judging individuals by their external markers and indicators (‘gnorismata’) rather than by their observable behaviour. In the play, neither Kreousa nor Ion meets the standard of paideia, although the non-autochthonous Athenian Xuthus usually does. When the character of Xuthus performs the belated naming ceremony on the boy, he prophecies a good fortune (‘Tyche’) that any audience would have recognised as a reference to the future role of Ion as the eponymous hero and father of all Ionians. But that ceremonial speech act is immediately followed by what to modern ears is a groan-inducing pun: ‘… for I first met you when you were exiting (‘exIONti’) the sanctuary’.157 The same word had already been used twice in the play where we can imagine the actors drawing attention to the pun in their diction and preparing the audience for the comic bathos of the naming ceremony.158 By word play, more suited to comedy than to tragedy, the mythic characters, like the historic Antisthenes, dismiss the whole discourse of eponyms and of Ionianism, and suggest that the play may be giving currency to the ideas of Prodikos, who taught that the gods were in origin nothing more than names of useful things.159

As in Athenian tragedy generally, the Ion exposes moral questions to scrutiny and debate. Although, when he is a mere temple servant, the character of Ion has qualms about killing the birds ‘that bring messages from the gods’, he decides to be a slave to his human duties and never to ‘cease serving him who feeds me’, an unheroic and hypocritical pragmatic surrender to outward conformity and its system of economic beneficiaries, who include not only himself but the sections of the Athenian citizenry who made good money from building, supplying goods and services to, and promoting the official rhetoric.160