15. Summary: Fundamentals of Character Theory and Analysis

©2025 Jens Eder, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0283.15

This book began with the observation that characters are omnipresent and have an immense influence on life in today’s media societies. There are many reasons to take a closer look at them. Filmmakers and other creators want to make them more interesting or effective; pundits and enthusiasts want to understand them better or experience them more intensely; cultural critics and activists discuss their social causes or consequences. In everyday life, in professional circles and in the public, debates about characters are constantly erupting: about their discriminatory embodiment of social groups, their moral or religious significance, their artistic and aesthetic values, their complex or controversial meanings, or their successful or unsuccessful design and adaptation.

In all these cases, it is important to grasp characters perceptively and talk about them precisely. Subjective intuitions are often not enough for this. In order to understand characters in their depth and diversity, we also need more systematic approaches. These in turn depend on fundamental questions: What are characters and how do they come about? What are their features and structures? What is their relationship to media and narrative environments? How are they perceived and experienced by their audiences? And how do they relate to culture and society? There are many competing answers to such questions, but so far no coherent and comprehensive theory. The main aim of this book was therefore to bring together key perspectives from different disciplines in order to find out how characters can be studied more thoroughly and deeply. The following summary of the findings provides a general orientation and can therefore also serve as a starting point for looking up the more detailed arguments and references in the previous chapters.

15.1 A Theoretical Basis and a Model for Analysis

What Are Characters and How Are They Experienced?

What characters are is already very controversial, as the first parts of this book have shown (especially Chapters 3, 5, and 6). Often, they are seen as imaginary humans, but their spectrum also includes animals, aliens, monsters, robots, ghosts, gods, animated shapes, singing plants, talking toys, and any kinds of fantastic creatures. All these beings are distinguished from inanimate elements of represented worlds, such as refrigerators or mountains, by their inner lives, their perceptions, thoughts, motives, feelings, and other experiences ascribed to them. These inner lives can remain rudimentary (Punch or Lassie do not have particularly differentiated psyches) but must be represented or suggested in some form or other.

The mode of existence of such depicted beings, especially fictional ones, is viewed very differently and discussed controversially by scholars in philosophy, psychology, film, literature, and media studies (Chapters 2, 3). Most theories regard characters either as sign constellations or as mental representations. Such views have practical consequences; they determine how characters are analysed. Hermeneutic interpreters, for example, tend to focus on characters’ psyche or cultural meaning, while (neo-)formalists rather concentrate on their textual design. However, most competing approaches can be related to each other if films and other media texts are understood as tools in communicative games of imagination in which the participants create worlds and beings together. Like laws or scientific theories, these collectively imagined worlds and beings are sophisticated artefacts that emerge from social practices of communication.

Among other things, this means that characters are formed on the basis of creators’ and audiences’ experiences in real life, but can be perceived to varying degrees as corresponding to or deviating from reality. In both fictional and non-fictional media texts, characters are co-created through imagination and communication, albeit according to different rules. The basic rule for fictional texts is: ‘Imagine … but don’t believe that everything is true’, so that even historical figures such as Napoleon or Phoolan Devi are separated from reality in them. Fiction thus enables an especially broad range of dramatic intensification, idealised exaggeration, escapist flight, nightmarish counter-reality, or defamiliarising estrangement. In contrast, the characters or ‘media personae’ of documentary film and other non-fictional media are associated with claims to true and truthful representation and concrete correspondences with reality (claims that are often not fulfilled, but still exist and can have legal consequences). Nevertheless, non-fictional characters too are communicative artefacts, products of collective imagination, and should not be confused with the real people they are based on. Sometimes, the fictional or non-fictional status of characters and their relation to reality may also be ambiguous or controversial, as in the case of the gods or saints in religious texts. This book focuses predominantly on fictional characters in film, and I am aware that non-fictional characters as well as characters in other media would require a more in-depth examination. However, the fundamental similarity of their ontology and genesis suggests that most findings of this book can also be applied to them (see, for example, the analysis of Yellow Fever in Chapter 4).

So, my general proposal is to understand characters as recognisable represented beings with an inner life that exist as communicatively constructed artefacts (and thus as abstract objects in the sense of philosophical metaphysics; see Chapter 3). In the case of film characters, all their properties are attributed to them in the communicative processes of making and experiencing films. Filmmakers create and viewers process the signs and cues of the film, supplementing explicitly given information with their own knowledge, experience, and imagination to form vivid mental models of depicted beings. Nevertheless, characters are neither signs ‘in the text’ nor mental representations ‘in the head’, but collective constructs with a normative component. The individual character models of filmmakers and viewers resemble each other because they are formed on the basis of partly shared physical and psychological dispositions, including a shared knowledge of media and reality.

At the same time, the development of character models is not only based on such shared dispositions, but also on the rules and conventions of certain games of communication and imagination (such as Hollywood or Bollywood genres, or modes of arthouse cinema and documentary film). That characters have properties which are considered intersubjectively valid on the basis of communicative conventions is shown by the fact that we can argue about who understood a character better. Perhaps each of us has a different idea of one and the same character, but in meta-communication about characters we all assume that these ideas are not arbitrary. For example, anyone claiming that Rick Blaine is an alien or a Nazi spy would not be taken seriously. And any discussion about whether Rick and Ilsa really love each other presupposes that there are more or less correct views about this, which could be justified by recourse to the film and communicative rules.

Thus, characters are not purely subjective, but intersubjective. Nevertheless, their reception and mental representation are of decisive importance (Chapters 3, 5). Since characters are understood, remembered, loved or hated, they must be mentally represented in some way. Different philosophical, psychological, and semiotic theories regard the mental representations of characters as sign complexes, propositions, mental imagery, or patterns of neuronal activation. The approach with the greatest explanatory power, however, conceives of characters as being represented in the form of mental models. These models are multi-modal; they combine various forms of perception, imagination, and information—visual, acoustic, linguistic, etc.—into a vividly experienced whole, a gestalt. Mental models are dynamic, change over time, are present in consciousness during reception but can step back and be stored in memory. Character models represent the traits of a represented being with a certain structure, vividness, and perspective, which varies in different media, works, or scenes of one film. They are closely connected to other mental models that viewers have of the situations in the story or of themselves. When we watch Casablanca, for example, we form mental models of Rick, Ilsa, and the other characters, arrange them into situation models, and relate them to each other and often also to our self-models (for example by comparing oneself to Rick, Ilsa, or Sam). The structures and contexts of character models are therefore important in explaining how we react to characters or ‘identify’ with them.

The theoretical approach of mental modelling emphasises the mediality, constructivity, perspectivity, and fluidity of characters, which comes to the fore in numerous works: for example, when in animated films characters form fleetingly, only to immediately transform again or dissolve completely; when their artificiality is self-reflexively stressed (as with Daffy Duck in Duck Amuck); when in surrealism they exhibit absurd inconsistencies and inexplicable behaviour (as in L’Age d’or); when in mind-game films they turn out to be something different than previously assumed, sometimes even a mere hallucination (like Tyler Durden in Fight Club); when their ontological status within the storyworld—whether they are real, merely imagined or unreliably narrated—remains uncertain (like in Last Year at Marienbad). Such stylised, fragmented, metamorphotic, or metaleptic characters often point to further levels of meaning.

The formation of mental character models is a prerequisite for the genesis of characters, but it is by no means the only aspect of their reception. Rather, it is at the core of several interrelated levels of character-centred reception processes (see Chapter 3 and Chapter 4):

- the sensory perception of material signs representing the character, such as moving images and sounds in a film (or letters in a book, static images in a comic);

- the mental modelling of the represented being;

- inferences about its higher-level meanings;

- assumptions about its causes and consequences in reality; and

- aesthetic reflection on its representation in the medium (regarding levels 1–4).

In the case of Rick Blaine in Casablanca, for example, we perceive actor’s voices, moving images of Humphrey Bogart’s body, and many further filmic signs, mostly in a preconscious way. We then process these sensory perceptions in several steps further to form a mental model of Rick. Among other things, we combine partial views of his moving body, various verbal statements about him, and conclusions about his inner life to create an overall idea of an interesting-looking cynic in existential crisis. This initial model deepens and changes dynamically over time until we leave the film with a final model of Rick that we can remember later. During the film, we can also make inferences about Rick’s ‘higher’ symbolic or thematic meanings. For example, we may assume he represents the conflict between love and duty, or symbolises the importance of moral integrity. Moreover, we can think about Rick’s causal relations to the filmmakers or to certain audiences, for example by asking ourselves what political intentions the filmmakers had with Rick, or what effects he had on college audiences in the 1950s. Last but not least, we can reflect on how Rick is presented through the film’s forms and devices, such as Bogart’s acting, camera work, or narrative structure.

Chapter 3 of this book shows that these levels of experience are consistent with both everyday talk about characters and sophisticated theories of textual meaning. Each level involves specific cognitive and affective processes that can be analytically separated. However, these processes build on each other and are in constant interaction. When analysing characters, therefore, all levels of experiencing them should be considered, and it should be clear which ones the analysis focuses on and which ones are excluded. This is worth mentioning because many theories and studies tend to ignore certain levels, particularly the third and fourth.

A Heuristic Tool for Analysis: The Character Clock

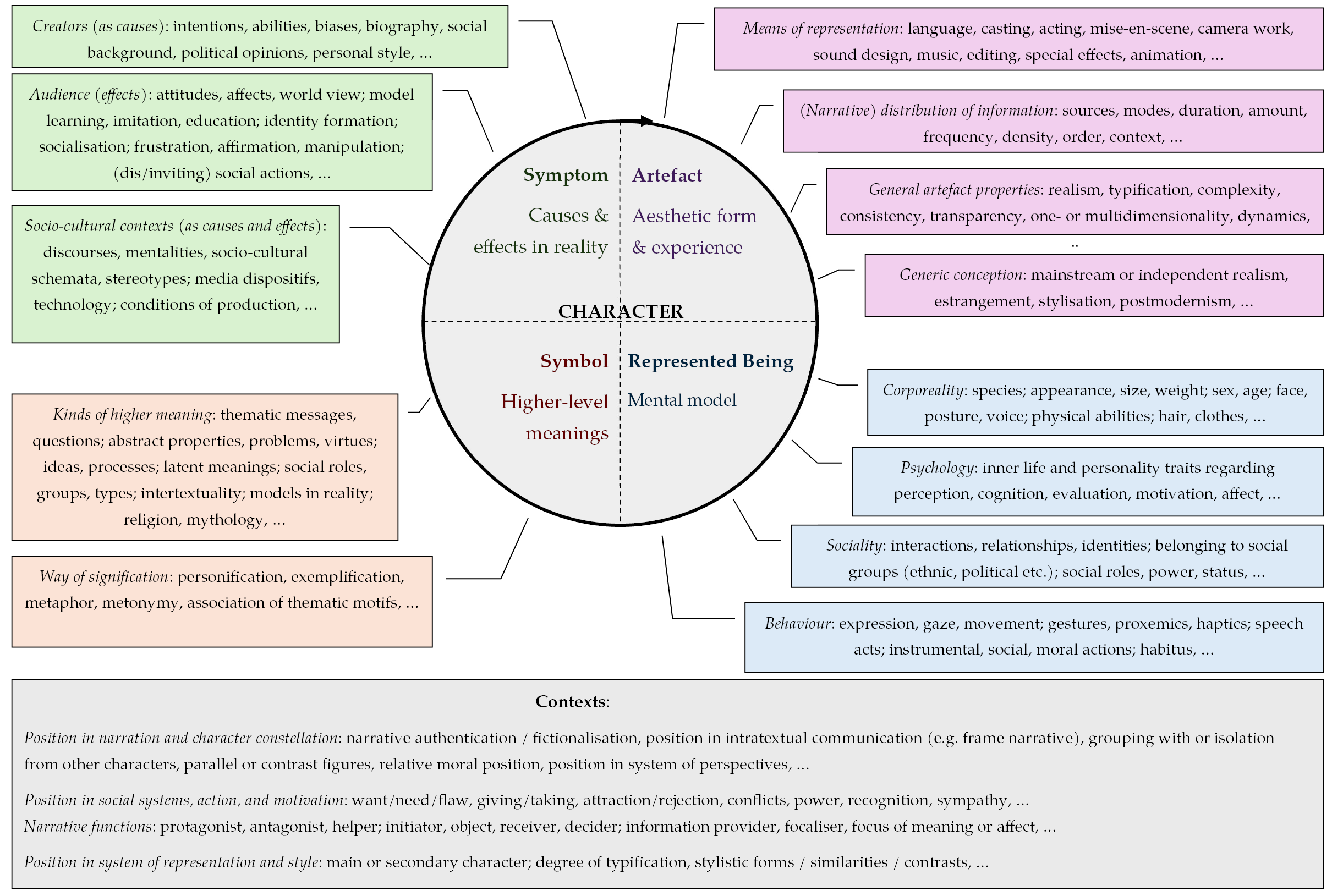

To counter this tendency and encourage a more complete approach, a simplified heuristic for analytical practice can be derived from the theoretical basis: the Character Clock (see Chapter 4 and Diagram 34). According to this heuristic model, characters have four aspects or dimensions. They can be analysed from an aesthetic, mimetic, semantic/thematic, and causal/communicative point of view, each of them focusing on specific questions:

- Artefact—How is the character represented? Here, characters are considered in relation to the signs and structures of the media text. Texts evoke sensory and perceptual experiences (first level of reception), but later one can also consciously reflect on their formal qualities and aesthetic strategies and attribute general artefact qualities to the character, such as realism or complexity (fifth level) (Chapters 7, 8).

- Represented being—What traits, relationships, and experiences does the character have in the storyworld? The answers are based on the formation of mental models and concern the character’s body, mind, sociality, and behaviour (Chapters 5, 6).

- Symbol—What does the character stand for, what higher-level meanings does it convey? ‘Symbol’ here refers to all forms of second-order meaning in which characters function as signs for something else, such as an overarching theme or message (Chapter 11).

- Symptom—What are the causes and effects of the character in extratextual reality? Here the characters are considered as having or indicating certain causes and effects in communicative and social reality, for example as results of filmmakers’ intentions or as behavioural models for the audience (Chapter 12).

We are therefore not only dealing with a ‘twofoldness’ of characters as represented beings and artefacts (Smith 2011), but actually with a ‘fourfoldness’. When watching and analysing films, attention may switch between these four aspects of characters, focus on one or more of them, and connect some of them. When watching Casablanca, viewers may primarily perceive Rick as a casino owner in love, but occasionally also admire Bogart’s acting, understand Rick as a symbol of the USA, or question the idea of masculinity that he embodies. When they think about him later, they may further elaborate their model of the represented being (for example, regarding Rick’s psyche) or focus more on the character’s qualities as artefact, symbol, or symptom. For some characters, the latter aspects may already be foregrounded from the start. For example, sometimes characters are portrayed in such striking ways that we pay more attention to their design as artefacts than to their traits as beings in the storyworld. Or we have already read in a review that certain characters affirm discriminatory stereotypes, which pushes their symptomatic dimension into the foreground. In all four dimensions, individual characters are embedded into larger contexts, such as stylistic and representational conventions (Chapters 7 and 8), the narrative contexts of action, story and plot (Chapter 9), the character constellation (Chapter 10), as well as contexts of meaning, production, and culture (Chapters 11 and 12).

The heuristic model of the Character Clock largely corresponds to a broad range of existing theories from different disciplines, such as Roman Ingarden’s multilevel structuring of literary works (1931), Erwin Panofsky’s image analysis (1955), James Phelan’s ‘multichromatic’ conception of literary characters (1989), Per Persson’s stages of film reception (2003), as well as current psychological views of art perception (Pelowski et al. 2017). The model proposed in this book draws on some of these valuable approaches, but at the same time attempts to go beyond them by showing how they might be systematically related on the basis of more general theories of reception and meaning, as well as analyses of everyday talk about characters and art. Thereby, the Character Clock model aims to capture some basic distinctions that are lost in other approaches and to put various disciplinary perspectives on characters in connection to each other. For example, most cognitive theories focus on characters as represented beings and artefacts but tend to neglect their qualities as symbols and symptoms, which take centre stage in psychoanalytical approaches or cultural studies. The Character Clock makes such complementary emphases visible by providing an overview of the general dimensions of characters and their relations to different reception processes. It shows what kinds of properties can be attributed to characters, how these properties are connected, and what categories can be used to analyse and describe them.

The Character Clock model was developed with a focus on film, but it is fundamentally transmedial and can be applied to characters in different media. Of course, every medium shapes its characters in specific ways. The material, sensory, and semiotic qualities of different media, their technologies, organisations, practices, and conventions lead to media-specific forms and types of characters, and to different experiences and mental models of media users. In literature, for example, the inner life of characters is usually described directly through written language. Photography or painting, on the other hand, rely primarily on bodily expression in a single significant moment. Film, again, conveys the experiences of characters primarily through moving images of external action as well as spoken language, sound, or music. In combination with other factors, all this may ultimately contribute to broad media-specific tendencies, such as a greater frequency of action-centred characters in film, interiority-centred characters in literature, symbolic characters in painting, or talkative characters on the stage.

However, such differences between media mostly concern the concrete manifestations and the frequency of certain characters rather than the general dimensions and categories of character analysis. Characters in all media can be analysed as represented beings, artefacts, symbols, and symptoms. Within these four dimensions, many more specific categories described in this book can also be applied to characters in different media to examine, for instance, their psyche and sociality, their higher meanings, or their social effects (see Diagram 34, external fields). There is one important exception, one crucial difference, that concerns mostly Chapter 7 in this book: the design of characters as artefacts (and thus their phenomenological experience) will differ significantly from medium to medium, especially regarding the concrete means of representation. The analysis of cinematic devices (such as acting, camera work, sound design, editing) would therefore have to be replaced by the analysis of the specific means of other media, such as single-frame sequences in comics, or musical stage performances in opera. This in turn affects other aspects of the artefact dimension, such as narrative structures typical of certain media. A further limitation of the heuristic model in this book concerns the analysis of characters in interactive media, such as avatars in computer games, as well as transmedia characters. Jan-Noël Thon, Felix Schröter, and others have made interesting suggestions as to how the model could be further developed in this respect (see Chapter 2). With suitable additions, it could also provide a basis for media-comparative analyses of characters, but this goes beyond this book.

In the practice of analysing, interpreting, and evaluating characters, the Character Clock model can be used flexibly. In the previous chapters it has been applied to analyse characters in very different types of films, such as Hollywood movies (Casablanca, Imitation of Life), European auteur films (The Marriage of Maria Braun), non-fictional animated essay films (Yellow Fever), and many other works. Later in this summary I will say a little more about how the model can be used in analytical practice, and at the end its suitability will be tested through a challenging case study, Roman Polanski’s Death and the Maiden. But before that, let’s look again at some more nuanced analytical categories in each of the four general dimensions of the Character Clock (see Diagram 34, external fields).

Diagram 34 The Character Clock and its central categories

15.2 How Can Characters Be Understood in Their Different Dimensions? A Conceptual Toolbox

Characters as Represented Beings

When analysing characters, it often makes sense to start with their traits as thinking, feeling and acting beings in a storyworld (see Chapter 5 and Chapter 6). This is their defining core and, in most cases, the central aspect of experiencing them. Even if some characters appear to be intuitively and instantly accessible in this respect, it is never easy to describe represented beings in a differentiated and convincing way. To do this, precise expressions must be found for subtle, complex qualities that are often only grasped through unreflective perception, or are inferred through imagination and interpretation.

Recourse to interdisciplinary studies of humans and other beings in reality can help here. Of course, it would be naive to equate characters with real persons; our approach to both is fundamentally different. We cannot physically and socially interact with characters as we do with persons, and we do not view persons as communicative artefacts, symbols, or symptoms shaped by media texts (at least not in the same way as characters). Moreover, characters can take on forms that are very different from real people or animals and enable counterfactual thought experiments, hybridisations of the human and the non-human, or experiences of alterity that transcend reality. However, as our development of mental character models is to a large part based on everyday experiences with extratextual reality, many useful concepts from disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, sociology, anthropology, ethnology, or biology (including their reconstructions of common folk-theories) can still be used to perceive and describe characters in more differentiated ways. In doing so, it is important to reflect on the extent to which such concepts fit the analytical question, the characters and works to be examined, and the cultural context within which they were created or experienced (e.g., does it make sense to use concepts from psychoanalysis or behaviourism to describe a character’s psyche?).

On this basis, the following system of categories for analysing represented beings can be proposed (Chapter 6). It is anthropocentric, but with some modifications it can also be applied to non-human characters (animals, monsters, robots, aliens). Based on common distinctions in philosophy, narrative theory, and everyday life, we can most generally distinguish between three broad areas of properties that both real and represented beings exhibit:

Of course, the distinction between these areas is again a heuristic simplification, as they are by no means strictly separated, but rather entangled with each other. They overlap and come together, particularly in behaviour, but can still be analytically distinguished and related to each other. Their distinction may seem almost banal, but it can help a lot in not becoming blind to important features of the character and overlooking them simply because they seem self-evident or are overshadowed by more striking features.

When analysing represented beings, it is therefore often useful to start with asking what their most important physical, mental, social, and behavioural traits are. In each of these areas, more specific categories can then be used for more detailed analysis (see Diagram 34, bottom right). They can help to be more attentive to subtle but significant nuances of the character and to avoid missing relevant features.

To analyse the physicality of characters, we can go beyond everyday talk by drawing on interdisciplinary studies of human (or animal) bodies. Psychological, sociological, and linguistic research on nonverbal communication is particularly useful as it allows for a more accurate perception and description of characters’ appearance and performance, such as their body shape, face, gaze, voice, expressions, posture, gestures, kinesics, proxemics, haptics, body-related accessories and styles (such as clothing or hairstyle). Such categories sharpen the eye for what is otherwise often only subliminally perceived, such as Rick Blaine’s larger-than-average, expressive face, the efficiency of his movements or his alternately absent, controlling, and wistful gaze. Particularly significant in the area of physicality, as in the other property fields, are characteristics that are linked to widespread norms and ideals, such as physical beauty, strength, or agility. In this context, for example, it can be noted that blockbusters focus on such characteristics, or that Casablanca blends out people with visible disabilities.

Often, external physical features of the characters already point to mental or social properties. The sociality of characters can be analysed in more detail by using concepts from cultural studies and social sciences. Categories from sociology and social psychology are particularly helpful to describe characters’ social identities, interactions, relationships, roles, positions of power and belonging to certain groups (for example, regarding gender, partnership, friendship, family, profession, class, ethnicity, nationality, politics, or religion, as well as their various intersections). Sociology has imported some crucial concepts (such as the social role) from the arts, and they can now be re-imported in a refined form. The characters’ positions in social power structures and intergroup conflicts are particularly relevant. Rick, for example, is at first characterised primarily as a middle-aged white American man in exile, who holds a self-sufficient position of power and high status in Casablanca through his role as a casino owner and his skilful manoeuvring between conflicting groups. He initially organises his social ties according to pragmatic-egoistic criteria and tries to stay out of the conflict between Nazis, Vichy French, and refugees. But eventually, he assumes moral responsibility, sacrifices his love, gains a friendship and decides to join the Resistance, thereby becoming part of a new group and assuming a new social identity.

To analyse the psyche—the inner life and personality—of characters, one can generally start with their traits and experiences regarding the basic mental faculties of humans and other animals: perception, cognition, evaluation, motivation, and emotion. In our example, Rick’s thoughts and feelings mainly revolve around Ilsa and himself, he recaptures lost values, and his emotional and motivational development progresses from bitterness to longing to serious determination. More detailed analyses of characters’ minds can draw on various approaches, in particular reconstructions of folk psychology, historically and culturally specific ideas of the mental, and various current theories such as psychoanalysis, personality psychology or cognitive science. Again, such approaches can provide more nuanced descriptions of represented beings, but they can also lead to widely divergent analyses and interpretations. Rick’s personality traits, for example, could be described according to the leading psychological model of the Big Five factors: extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness to experience. At the beginning of the film, we could describe him as introverted, conscientious, difficult to get along with, emotionally unstable, and not very open. However, based on psychoanalysis, we would come to very different conclusions by focusing on Rick’s unconscious, his repressed desires, inner conflicts, neuroses, childhood experiences or object attachments (which are each interpreted differently by diverse psychoanalytic schools). For example, some authors have described Rick as an Oedipal character.

Choosing between such competing conceptualisations of physicality, psyche, and sociality depends on several criteria. One of them is the aim of the analysis: Is it about how past, present or future audiences perceive and experience Rick? Or is it about how the filmmakers intended Rick to be experienced? Or is it about determining what an ‘ideal’ perception of Rick would be like, one that is particularly inspiring or corresponds to optimal communication? Another criterion concerns which features of the character are unclear or controversial in the first place. In most cases, there is widespread agreement about physicality and clearly signalled social positions—nobody will doubt that Rick is a dark-haired café owner. Differing interpretations mostly concern imperceptible aspects of inner life or complex nuances of social behaviour. For example, do Rick and Ilsa really love each other? And did they sleep together, even if it is not shown in the film? Answers to such questions require interpretation and justification. Ultimately, they are based on assumptions about dispositions of the empirical, intended or ideal audience. These include dispositions that also guide the perception of real people (e.g., folk psychology or social stereotypes), but also knowledge about media and communication (e.g., genres or character types). Since such dispositions range from innate reaction tendencies to culturally shaped affect structures to individual memories, they have varying degrees of intersubjective similarity and validity. Reflecting on how the aims of the analysis relate to such audience dispositions can help to choose and justify certain approaches to characters’ bodies, minds, and social lives, and thus substantiate their interpretation.

However, when we examine characters’ physicality, psyche, and sociality, we do not only refer to the storyworld level. Although their psyche and sociality are revealed to a large extent through their externally perceptible features (appearance, behaviour, speech, or surroundings), information from outside the storyworld, such as a voice-over, extradiegetic music, visual styles, or perceived plot functions, also contribute to their characterisation. For example, the casting of Bogart and Bergman already signals that Rick and Ilsa will continue their affair, and what they feel when they say goodbye is suggested by the musical leitmotif ‘As Time Goes By’. The above categories thus help to describe the traits of represented beings, but are not sufficient to explain how these beings and traits emerge. For this, characters must also be considered as artefacts.

Characters as Artefacts

The basic question when examining characters as artefacts is how they are given certain aesthetic forms by media means and textual techniques. We can analyse the formal qualities of characters on four levels of increasing abstraction (see Diagram 34, top right). The first two levels concern the mode of representation (Chapter 7):

- media-specific means shape the sensory-semiotic cues that guide our encounters with characters, and

- these cues are distributed across narrative, rhetorical, or other textual structures.

The other two aspects concern the results of these modes of representation (Chapter 8):

- characters are ascribed general artefact qualities (e.g., complexity), and

- they correspond to (or diverge from) overarching, conventional character conceptions of media genres or cultures.

In film, a variety of cinematic devices shapes the flow of images and sounds that present characters to the viewer into a concrete, sensual form: casting, acting, staging, mise-en-scene, camera work, sound, music, and editing contribute to this. Such categories of film production help describe the sensory presence of characters, their phenomenal experience that is otherwise difficult to grasp. For example, if we say that Bogart’s face is shown in slightly low-angle close-ups and first given little, then more fill light, this explains how visual experiences are evoked that make Rick appear as ‘close’, ‘tall’, ‘dark and hard at first, later a little softer’. If Casablanca were a novel or a comic, its characters would be presented through other, linguistic or visual means such as word choice or drawing styles, with correspondingly different sensual-aesthetic effects. To examine this in more detail, we could draw on a wealth of art and media studies. The analysis of the means of characterisation breaks down the character as an artefact into many partial aspects, such as Bogart’s acting, Curtiz’s staging, or Edeson’s camera. These partial aspects combine to form certain patterns and media-, author-, or work-specific styles of characterisation.

On a more abstract level above concrete media devices and techniques, characters are shaped by narrative, rhetorical, or other overarching text structures. All signs or cues that trigger processes of character reception can be regarded as character-related information. This information is structured in specific ways, guiding the formation of mental models and other cognitive and affective processes, such as curiosity, suspense or surprise. Information about characters can have different functions, relevance, modality, immediacy, and reliability, and can be conveyed by different means and perspectives. For example, it makes a difference whether a characterisation comes from a reliable or unreliable narrator, or that the act of love between Ilsa and Rick is only vaguely suggested and not directly shown. In addition to these modes of character information, it is also important how this information is arranged in the text, that is, in which order, frequency, duration, quantity, density, and context, and whether it is redundant, complementary, or discrepant.

The use of such structural categories makes it possible to differentiate between various forms and developments of character models. Films can facilitate, complicate or even completely block the formation of consistent models. Many protagonists are introduced right at the beginning in condensed portraits. In other cases—as with Rick—their exposition is stretched out. Some characters only become comprehensible at the end of a work, others remain enigmatic even then. Information about characters is often bundled into particularly significant phases of characterisation. In addition to the exposition and the ending, these include extended dialogues, plot climaxes, scenes of decision or empathy, of crisis and change, sequences with typical or conspicuous behaviour, or scenes that vividly present the character’s mental experiences. In such significant phases, both the audience’s character models and the depicted beings in the storyworld themselves can change. Both kinds of changes need not necessarily go hand in hand, so characters may appear different to the audience than they actually are in the storyworld, which is often used for narrative effects. For example, for a while you may fear that Rick will actually hand Victor Laszlo over to the Nazis, whereas in reality he plans to save him.

Cinematic devices and narrative techniques make viewers form mental character models with a certain structure. Building on this, we attribute broader artefact qualities to characters, such as realism, stereotypicity, complexity, consistency, transparency, multidimensionality, dynamism, and their counterparts (Chapter 8). Such terms refer, on the one hand, to how the character model is internally structured, for example, whether the traits represented in it fit together (consistency). Moreover, artefact qualities indicate how the character model relates to other mental representations of the audience—for example, the extent to which it corresponds to common ideas of reality, cultural ideals, or narrative stereotypes (realism, idealisation, typification). For instance, Rick was considered idealised because he is so extremely cool and willing to make sacrifices. And that Ilsa initially acts courageously, strongly and independently, but then hands over all decisions to Rick, may be seen as psychologically inconsistent, or as conforming to gender stereotypes. This also reveals a double meaning of speaking about the ‘multidimensionality’ of characters: on the one hand, multidimensionality can be understood as the roundedness of depicted beings with a rich set of traits, and on the other as the general fourfold nature of characters as artefacts, depicted beings, symbols, and symptoms.

If certain combinations of artefact qualities are repeated in many characters over time, they can congeal into character conceptions, cultural conventions of creating and experiencing characters (comparable to genres, and often related to them). Character conceptions can influence both aesthetic judgement and cultural images of human nature. According to the conception of mainstream realism, prevailing in Hollywood and other popular narratives, protagonists are supposed to be individualised, multidimensional, consistent, easy to understand, psychologically transparent, dynamic, autonomous, and dramatic. Mainstream films and novels thus suggest an image of humans as easily understandable, coherent, conscious, emotional, autonomous, active, morally straightforward beings. In contrast, characters in independent realism, as in Akerman’s or Antonioni’s works and many other arthouse films, are more opaque, ambivalent, complex, and difficult to understand, less consistent and less dramatic, more static and more passive. The result is a different image of humans as fundamentally incomprehensible, morally ambiguous, emotionally diffuse, driven by unconscious motives, at the mercy of external and internal constraints, and inherently contradictory. Further character conceptions, for example in postmodern, surrealist, or experimental works, differ from both types of realism in that they stylise, alienate, fragment, or even dissolve the characters, thereby emphasising their dimensions as artefacts or symbols in the audience’s experience.

Characters can thus be analysed as artefacts by examining the media-specific means of their presentation, the structure of the textual information about them, the constellation of their general artefact qualities, and their relation to existing character conceptions in media culture. For example, although Casablanca provides information that places Rick Blaine as the protagonist at the centre, it leaves his motivation and true personality largely in the dark for a long time, thus fostering curiosity and suspense. Rick’s characterisation involves seemingly contradictory cues: everyone respects, admires or desires him, although he remains cold and, by his own words, ‘sticks his neck out for nobody’. Such apparent contradictions are resolved by Bogart’s star image and acting style, which, in a blend of realism and idealisation, emphasise Rick’s deep hurt and signal his future transformation. All that contributes to making Rick an individualised, multidimensional and dynamic character. However, due to his passivity and opacity throughout much of the film, Rick does not fully conform to Hollywood’s convention of mainstream realism, but in some respects appears closer to independent realism. Of course, one could go into much more detail and describe subtle strategies that shape our experience of the characters in certain scenes, such as when Rick’s delayed exposition plays on the desire to finally see his face. Such analyses always rely on (mostly implicit) assumptions about reception, about how the artwork evokes certain experiences, as well as about a character’s contexts.

Characters and Their Contexts

In all their dimensions, characters are embedded in various narrative, aesthetic, semantic, and practical contexts: as represented beings in the film’s storyworld, as artefacts in its textual structures, as symbols in its higher meanings, and as symptoms in the sociocultural contexts of production and reception. Two narrative contexts are especially important in analysis: plot and character constellation (see Diagram 34, bottom).

An essential link between characters, story, and plot is the motivation of their actions (see Chapter 9). Most stories and their narrative organisation in plots revolve around the actions of characters, and when characters act, certain motives are attributed to them that can evoke interest, curiosity, suspense, and surprise. When Rick insults Ilsa, we may assume that he wants to take revenge on her. Conversely, we can also already know a character’s motives and therefore expect them to carry out certain actions. We know that Rick still loves Ilsa and wonder what he will do to win her back. Inferences from known motives to future actions can create suspense; inferences from actions to underlying motives can create curiosity, understanding, perspective-taking, or empathy.

The characters’ central motives form the core of their personality, and their development—such as Rick’s change from selfishness to renunciation—is an important basis for a narrative’s overarching themes and affective involvement. In analysing motivation, we can draw primarily on psychology, philosophy, literary studies, but also on screenwriting guides. Among other things, they help to distinguish between different kinds and levels of characters’ motives, from general needs to more concrete values and wishes to specific goals and plans. Such types of motives have different effects on the narrative, its themes and the audience’s experience. For example, stories can focus on different levels of needs, from the need to breathe (e.g., in horror films) to social needs like love (in melodramas) to the need for transcendence (in spiritual films). Crucial to most stories are the characters’ social motives, which range between egoism and altruism and are often related to social groups and roles.

Characters’ motives also give rise to the driving force of most narratives: conflict. Narrative conflict patterns range from the inner struggle of individuals to interpersonal confrontations, to arguments in love triangles, to larger groups clashing. Characters come into external conflict with each other when their goals are incompatible: Ilsa needs the travel visas, but Rick doesn’t want to give them to her. Many characters have several motives at the same time, which leads to internal conflicts. Ilsa is torn between her role as Victor’s wife and Rick’s lover; she behaves altruistically and renounces her own desires in order to protect her husband. Screenwriting guides recommend that characters have a concrete external goal (‘want’), a real inner need, and a key flaw, all of which can come into conflict with each other. This inner conflict develops over the course of the plot and often only becomes apparent gradually. When Rick refuses Ilsa and her husband the vital visa, it is initially unclear why he is doing this. Does he want to win Ilsa back, take revenge on her, humiliate her or force an explanation from her? All these possibilities of external motivation remain open, but they all contradict Rick’s inner need to reconcile with Ilsa and restore his integrity. This need is initially opposed by his central flaw of selfishness and bitterness, which he overcomes in the course of the film.

Driven by their motives, the characters meet and interact with each other in changing scenic constellations that follow each other in the plot: Rick and Ugarte; Rick and Renault; Rick, Ilsa, and Laszlo. On a more general level, each character occupies a specific position within the character constellation, the overall system of all the characters and their relationships in a certain artwork (Chapter 10). In film, such systems range from one-person plays to ensemble films with dozens of characters. The structure of the character constellation is formed by the network of manifold relationships that exist between the characters both as represented beings and as artefacts. The individual characters are situated in networks of hierarchy, interaction, communication, values, narrative functions, similarities and contrasts, attraction and rejection, power and recognition, conflict and support. As major or minor characters, they occupy positions in a hierarchy of attention; as narrators and narratees in communication; as represented beings in a social system; as protagonists or antagonists in interactions and conflicts; as heroes or villains in a value structure; as parallel or contrasting characters in diegetic, stylistic, or thematic patterns.

How the characters are positioned in this constellation contributes significantly to their characterisation, narrative meaning, and audience involvement. As a rule, characters are perceived in comparison to each other, which emphasises certain traits and developments. The submissive, talkative Ugarte emphasises Rick’s self-sufficient, laconic nature; the idealistic Laszlo is the touchstone for Rick’s moral development. The way in which value-laden traits, such as moral qualities or physical attractiveness, are distributed across the characters in a constellation results in a value structure that affects the appraisal of the individual characters. In Casablanca, the range between good (Laszlo) and evil (Strasser) is wide. Rick rises from the middle of the moral spectrum to its positive extreme until he surpasses Laszlo not only in power, humour and attractiveness as before, but also in morality. In films noirs, on the other hand, often all the characters are more or less flawed, and the viewers tend to orient themselves towards those characters who behave the least immorally.

However, the character constellation is not only a moral and social system, but also a narrative and aesthetic system in which the characters fulfil certain functions as artefacts. They contribute to the development of the plot and its conflicts by performing narrative roles: as protagonist, antagonist or their helpers, as initiator of the plot, its target object, recipient, or decider. They offer a narrative perspective on the events, provide information, reinforce realism effects, convey superordinate meanings, establish intertextual references, or possess intrinsic aesthetic or affective value. The attention we pay to them as main or secondary characters depends, among other things, on the density and significance of such functions. Since protagonists and antagonists drive the plot forward, they generally occupy a prominent position in the hierarchy of attention.

Characters are also related to each other through similarities and contrasts of their diegetic and formal properties. Thereby they can be grouped or isolated in the constellation, often with sociocultural consequences. Characters from marginalised social groups are frequently forced into the function of antagonists or helpers, stereotyped, and portrayed in aesthetically unfavourable ways. Casablanca is not free of this either: the relationship between the main character Rick and the secondary character Sam is friendly but unequal, and Moroccans only appear in tiny roles as usual suspects or fraudulent dealers.

The various forms and functions of character constellations have hardly been researched to date, although they could offer essential starting points for analysing and criticising narratives from aesthetic, ideological, or political perspectives (for instance, many political narratives feature a constellation of perpetrators, victims, and heroes or helpers). The complex structure of character constellations has a broad range of narrative, aesthetic, and sociocultural effects. This concerns also the characters’ symbolic and symptomatic qualities.

Characters as Symbols and Symptoms

‘Symbol’ and ‘symptom’ are used in this book as umbrella terms to capture the various complex relationships of characters to higher-level meanings and sociocultural realities (Diagram 34, left-hand side). As symbols, characters contribute to indirect or superordinate meanings that go beyond the storyworld, such as the themes of an artwork (Chapter 11). As symptoms, characters point to causal factors that shaped them in sociocultural reality (e.g., in media production), as well as actual effects they may have on audiences or societies (Chapter 12). Because their study as both symbols and symptoms usually involves numerous contested presuppositions, it is often referred to as interpretation and distinguished from their more basic analysis as represented beings and artefacts. Interpreting characters is considered complex and controversial, and different emphases are placed on it. In everyday life, media users often interpret characters quite freely and casually; the classical hermeneutics of art, literature, and religion are dedicated to detailed symbolic interpretation; sociocultural criticism or psychoanalytical approaches, again, focus more on characters as symptoms; and some structuralist or neo-formalist media studies take a critical stance towards both. Moreover, there are media differences: characters in literature, theatre or painting tend to be more often considered as meaningful, culturally valuable symbols, while characters in film, comics, and other popular art forms are more often critically discussed as revealing or potentially dangerous symptoms. Such different attitudes towards the interpretation of characters as symbols and symptoms can be related to each other on the basis of a descriptive, meta-theoretical approach that starts from how characters are experienced in reception.

Accordingly, the study of characters as symbols is about exploring what higher-level meanings audiences can derive from the characters, based on prior knowledge, textual cues, and mental models (Chapter 11). On this basis, viewers can associate various types of higher meanings with a character’s features, such as references to virtues and vices, repressed desires, abstract facts, social groups, historical persons, or mythical figures. For example, interpreters have claimed that Rick embodies a certain personality type or masculinity ideal; that he stands for the American people or President Roosevelt; or that his moral development reflects US foreign policy during the Second World War. Moreover, Rick has been understood to represent thematic messages such as ‘the preservation of moral integrity is worth great sacrifice’. The association of the character with such ideas can arise in various ways, e.g., by generalising their traits so that they stand for a social group or humanity as a whole; by identifying their similarities and analogies with elusive processes such as love or death; or through their metaphorical or metonymic connections with semantic fields of all kinds. The characters in question thus become personifications, allegories, exemplars, or representatives of a theme. Some films explicitly call for such a search for higher meanings, for example many auteur films or animated films. But the symbolic and thematic meanings of characters are also important in mainstream live-action movies, as the example of Casablanca shows. The aim of entertaining an audience excludes neither deeper meanings nor propaganda messages.

This already points to the symptomatic properties of characters, their perceived causes and effects in extratextual reality (Chapter 12). The generic term ‘symptom’ refers to the dimension of characters as sociocultural indicators or factors, and thus also as causal links between production and reception.1 Once we have a rough idea of a character as a represented being, artefact, or symbol (and this can happen even before the film, for example through advertising), we can ask ourselves why the character was created like this, and what effects this might have on the audience or society.

When we look at the causes of characters, we can see them as indicators that point to very different factors of their emergence in communicative environments and sociocultural reality. Following Critical Discourse Analysis and other approaches, we can locate these causal factors at micro, meso, and macro levels. They include, for example, the motives of the individual creators involved (such as the members of a film team), the media dispositif (the structure of the medium as a constellation of technologies, organisations, professional roles and routines), as well as larger sociocultural contexts, including discourses, ideologies, or inter-group relations. In the case of Casablanca, for example, we can speculate how the actor Bogart, the Hollywood studio system, or cultural ideas of masculinity contributed to shaping the character Rick.

With regard to the reception and impact side, inferences can be drawn about the effects of characters as behavioural models, deterrent examples, empathy trainers, identification figures, parasocial partners, fictitious friends, opinion leaders, or objects of fear, desire, and worship. This concerns, among other things, the use and discussion of characters in contexts of psychotherapy, humanitarian communication, education, advertising, professional training, political propaganda, ideology critique, youth protection, as well as media production, ethics, and regulation. Chapter 12 brings together a wide range of findings from interdisciplinary research on the question of how characters can have real effects, including observational learning, imitation, pleasurable vicarious experience, narrative persuasion, cultivation, identity formation, Entertainment-Education, (anti-)discrimination, as well as more direct forms of impact on real-life relationships and practices. Characters like Rick can invite imitation and spark learning processes, contribute to images of humanity, provide building blocks for the construction of individual identity, confirm or question the social status quo.

Accordingly, characters are also used purposefully in various practical contexts, for example in school education, vocational training, commercial advertising, religious rituals, political information or demagogic propaganda. In societies where freedom of opinion prevails and the rights of minorities are protected, many characters have positive effects as elements of art, socialisation, moral clarification, social self-understanding, and self-questioning. But characters can of course also contribute to problematic discourses and societal structures, as ideology criticism rightly emphasises. Violent protagonists are often the subject of public debate about possible copy-cat crimes (as in the case of A Clockwork Orange). But more important are the negative effects of discriminatory characters (such as the Black villains in The Birth of a Nation). The stereotyping of marginalised social groups is one of the main causes of characters’ negative impact. As stereotyping concerns characters both as represented beings and as artefacts in the context of character constellations, it is addressed in several chapters of this book (particularly Chapters 6, 8, 10, and 11).

An essential aim of interpreting characters as symbols or symptoms is to justify or criticise evaluations of their meanings or their causes and effects. The fact that some theoretical approaches shy away from interpretation is problematic, as the four dimensions of characters all interact with each other. For example, if one recognises a profound meaning or a discriminatory stereotype in a character, this usually also influences how one perceives the character as a depicted being and as an artefact. It can draw attention to certain features of the character and change affective responses to them (as the example at the end of this book will show).

15.3 Experiencing Characters: Imaginative Closeness and Affective Involvement

The results summarised so far also have implications for the much-discussed question of how characters are experienced by their audiences. What forms of imaginative and affective involvement (or engagement) do they evoke, and in what ways? Obviously, characters can make us laugh, cry, marvel, tremble or rage, arouse curiosity or suspense, lust or disgust, admiration or hatred. Years later, we can still remember them with affection or trepidation. All of this is part of the psychological effects of characters, which in turn underlie their sociocultural impact. But how do such reactions arise and how can they be described and explained? Theories from various disciplines provide different answers to these questions. The most common approaches refer to ‘identification’, ‘empathy’, ‘sympathy’, ‘moral evaluation’, or ‘parasocial interaction’.

However, one-dimensional explanations based on these concepts fall short, as Chapters 13 and 14 show. In contrast, affective involvement with characters is conceptualised in this book as multidimensional, multilevel, perspectival appraisal of characters’ features and situations. Appraisal means an affective reaction to stimuli that are perceived as positive or negative, pleasant or unpleasant, attractive or aversive, which involves changes in bodily arousal. Such an appraisal is multidimensional because characters evoke affective responses in each of their dimensions: as represented beings, artefacts, symbols, and symptoms. It is multilevel because it is not limited to conscious judgements, but ranges from preconscious affects and moods to consciously experienced emotions to analytically reflected meta-emotions. And it is perspectival, because it always takes place from a certain perspective, shaped by the interplay of text structures and audience dispositions.

The affective multidimensionality of characters results from their fourfold nature and the corresponding levels of sensual-perceptual, cognitive, and imaginative reception: we perceive moving images or other material representations of characters, form mental models, associate higher meanings, and draw inferences about real causes and effects (Chapters 3 to 12). Each of these dimensions of experiencing characters involves specific kinds of affective responses. We can respond affectively to Bogart’s acting, Rick’s coolness, the meanings he conveys, the political intentions in his creation, and his presumed influence on other viewers. With different characters, works, genres, or media, different dimensions may dominate the audience’s affective experience. There is countless evidence of responses to characters that go beyond their qualities as represented beings, for example in the enthusiasm of fans for star performances or intertextual connections of favourite characters, in the interpretive desire of connoisseurs to decipher deeper meanings of auteur film protagonists, in public outrage over racist or sexist stereotypes, in censors’ concerns about moral influences of anti-heroes, or in the veneration of religious and political icons. The example at the end of this book will show how affective impulses from characters’ different dimensions can also come into conflict with each other.

If Chapters 13 and 14 focus primarily on involvement with characters as represented beings, it is because this tends to dominate both the audience experience and the theoretical discussion and already requires considerable clarification. Research in psychology and neuroscience suggests that perceiving and modelling characters and their situations evokes affective appraisals on different levels of consciousness, shaped by structures of the human body, sociocultural influences, and individual experiences. The approach proposed here builds on that research, but in contrast to many other theories, particularly in media psychology, it emphasises the mediating role of imagination and perspectivity in responding to characters. Accordingly, affective appraisals of depicted beings and situations nearly always involve imagination and take place from a certain perspective, guided by the media text. In media studies, this is often treated under terms such as focalisation, filtering, or point of view, which emphasise relations either of (visual) perception or knowledge. However, this does not go far enough; perspectivity must be understood more comprehensively.

Chapter 13 has therefore argued that all responses to represented beings are shaped by a system of imaginative closeness or distance to them, which influences how we judge them, whether we like them, and whether we take sides for or against them (with implications for their sociocultural impact and ethical evaluation). Imaginative closeness or distance to characters has spatial, temporal, social, cognitive, and affective aspects that interact with each other and are guided by media texts to achieve certain effects. In film, for example, close-ups can give the impression of being spatially close to a character, and slow motion can synchronise us with a character’s experience of time. Both spatial and temporal proximity have immediate bodily effects. Another, situational form of closeness arises when we experience events of the storyworld together with the characters, or when films direct our attention to the same objects and action possibilities on which the characters are also focused. Moreover, we can feel close to a character in the sense that we understand their psyche, their sociality and their situation well, because the film provides relevant information about them. In terms of social closeness, viewers can compare their own social position (as lovers, parents, workers, outsiders) with that of a character and gain the impression that they are familiar or similar to them. They can assign characters to their own in-groups or out-groups, project social desires onto them, or feel like they could interact with them. Finally, affective closeness to characters emerges when viewers develop strong, positive feelings for them or empathically share their emotions.

All of this can be guided by the film. Mainstream films usually aim to enhance the viewers’ closeness to their protagonists in all aspects while keeping much greater distance to antagonists. In Casablanca, numerous techniques are used to bring the audience closer to Rick, such as close-ups of his face, approximations to his visual point of view, the narrative focus on his experiences, dialogues about his inner life, the flashback to his memories, or the suggestion of inner processes through mood music and mise-en-scene. Rick’s narrative characterisation and his embodiment by Humphrey Bogart reinforce the social closeness of male, middle-class, anti-fascist Americans to him, and his moral development and prosocial actions suggest positive appraisals and emotions. In contrast, some types of arthouse films create a far greater (Brechtian) distance to their protagonists.

The most important aspect of closeness to characters concerns the viewers’ relationship to the characters’ mental perspective on the storyworld, their way of experiencing its elements and situations through perception, cognition, evaluation, volition, and emotion. Both characters and viewers (and sometimes narrators) can be ascribed such a mental perspective, and through audiovisual and narrative techniques, films can bring their perspectives into specific relationships to each other. As a result, the way a viewer experiences the storyworld can be more or less close to the experience of a character in various ways, which are in principle independent of each other, including the perspectives of seeing, hearing, imagining, thinking, knowing, judging, wishing, and feeling. For example, a POV shot can bring us close to Rick’s visual perception, while we don’t share his knowledge or feelings: we may see Ilsa from a similar point of view as him, but while he is angry with her, we can know more than him and sympathise with both of them.

The system of mental perspectives establishes different ways of experiencing characters: viewers can react to them like distanced analysts, engaged observers, empathisers, or imaginary interaction partners. Sometimes viewers follow a character through the action like external observers, feeling for them in a way that is distinctly different from the characters’ own feelings (this is often referred to as sympathy or antipathy). In other cases, viewers identify with a character by sharing their perspective in relevant ways (e.g., we may share Rick’s goals at the end of Casablanca). More particularly, a relationship of empathy is created when film techniques make us feel with characters and develop affects that are similar to theirs (e.g., through contagious expressions or mood music). And if viewers have the impression that characters are directly addressing or attacking them (think of monsters pouncing out of the frame or protagonists talking into the camera), these are cases of parasocial interaction.

These different perspectives and attitudes towards the characters influence the way the audience reacts affectively to them (Chapter 14). Basically, films direct viewers’ reactions by foregrounding certain features of the characters and their situations that act as affective elicitors and trigger appraisal processes. There are at least four basic forms:

- the appraisal of the characters themselves, which may be intersubjective or subjective/group-specific and

- the appraisal of the characters’ situations, which may be empathetic (sharing the characters’ feelings) or sympathetic/antipathetic (feeling differently from the characters).

Of course, this distinction is again a simplification, but it can help to better understand the range and interplay of various reactions to represented beings.

Accordingly, some appraisals focus on the characters themselves, their physical, mental and social traits and behaviours. In intersubjective appraisal, viewers react to characters’ traits according to widely shared values and norms: Rick’s altruistic motives may elicit the viewer’s moral approval. Moral appraisal concerns pro- or antisocial motives and actions (giving and taking) and is especially important. But the audience may also respond to non-moral qualities such as intelligence, humour, status, or physical strength.

In subjective appraisal, on the other hand, viewers assess characters according to their own individual or group dispositions and react with self-orientated affects. For example, characters can trigger erotic desire or political outrage if the viewers perceive them as attractive to themselves or dangerous to their in-group. Intersubjective judgements tend to evoke converging audience reactions, while subjective judgements tend to evoke diverging reactions from audience groups who differ, for example, in their sexual orientation or political opinion. These tendencies have an impact on narrative strategies for creating characters. For example, it can be assumed that commercial mainstream films align the design of their characters with the presumed dispositions of the majority of their paying target audience, so that their positive protagonists predominantly correspond to the values and interests of that audience, are attractive to heterosexual viewers, and elude political categorisation.

While both intersubjective and subjective appraisal concentrate on the characters themselves, other appraisals focus on storyworld situations that involve or concern the characters. Depending on the degree of approximation to the characters’ experience of the situation, such appraisals can be empathetic or rather sympathetic/antipathetic. Empathetic appraisal simulates the characters’ mental perspective and experience of the situation and involves affects that are largely similar to theirs. This can be achieved through various means, such as somatic contagion through the character’s expressions and bodily actions, foregrounding situational triggers and goals the character also focuses on, using music and other audiovisual means to create corresponding moods, or using narrative techniques that invite active imagination and perspective-taking. Empathetic appraisal can be fostered by the audience’s desire for vicarious experience and by their social comparisons with the character (‘ego-identification’ or ‘wish-identification’).

Objective, subjective, and empathetic appraisal of characters form the basis for developing more permanent dispositions of sympathy or antipathy for them, taking sides for or against them in conflicts. This is the basis of sympathetic feelings for characters (or antipathetic feelings against them) in situations that affect their interests and wellbeing. We hope that Rick and Ilsa will get together, fear that there is no happy solution for them, and are satisfied when they are able to maintain their integrity (and Strasser gets what he deserves). Taking sides for protagonists or against antagonists usually develops, as in this case, across longer, increasingly intensive episodes. In most films, the imaginative and the affective involvement with protagonists unfolds dynamically, but with increasing closeness and intensity.

The diversity of affective involvement with depicted beings results from the various forms of their perspectival appraisal in combination with the variety of their potentially affective features, such as their emotional expressions, their physical, mental or social abilities, their group membership, power and status, their selfish or altruistic motives, their pro- or anti-social actions, their beauty, illness and death. At the same time, the affective appraisal of such storyworld features and situations is influenced by multiple contexts, including the experience of characters as artefacts, symbols, and symptoms. For example, their conspicuous artificiality, crude symbolism, or discriminatory purpose can negatively influence their appraisal as depicted beings.

The understanding of imaginative and affective involvement with characters proposed here constitutes a novel theoretical approach that differs significantly from the currently most influential theories of characters and affect/emotion. In contrast to most positions in cognitive media theory, it emphasises the multidimensionality of appraisal; in contrast to media psychology its imaginative perspectivity; in contrast to psychoanalysis its variable range between identificatory closeness and analytical distance. The advantages of such an approach lie in its ability to differentiate between diverse types of affective involvement, to explain otherwise incomprehensible film structures and systematically diverging audience reactions, and to capture reactions not only to likable mainstream movie protagonists or identification figures, but also to ambivalent anti-heroes, terrifying monsters, objects of erotic desire, minor characters, disturbing arthouse protagonists, or symbolic characters in animated and experimental films. Most existing theories do not take this affective complexity of characters into account, but limit themselves to selected aspects of responding to represented beings, such as identification, parasocial interaction, moral judgement, or bodily contagion. Ultimately, they are based on the assumption that all other possibilities of affective reactions to characters, as outlined in Chapters 13 and 14, play no role. This assumption seems so implausible to me that it should be better tested theoretically and empirically.

15.4 Limitations, Implications, and Applications of the Theory: The Variety of Characters

The general aim of the theoretical approach developed in this book was to better understand characters as central elements of media, art and culture and to sensitise attention to them in all their dimensions. In view of the breadth, fragmentation, and messiness of interdisciplinary research on characters, it seemed to me that the most important thing at the moment was to help consolidate the field and develop a general conceptual and argumentative infrastructure for it. To do this, it was necessary to connect many individual theories from different disciplines, to triangulate and comparatively evaluate them in order to identify the central questions, conflicts and gaps within the field, and to understand for which purposes certain approaches might be best suited. If I have criticised other theories in the process, this in no way calls their value into question; I have learned much from them. In most cases, my criticisms concern only an over-extension of their scope, which often was originally limited to specific questions, dimensions or types of characters (e.g., Hollywood characters; represented beings; certain affective responses), but then expanded implicitly to the whole field.

Of course, I am aware that my book itself gives reason for criticism. Despite its excessive length, the complex subject matter has led to simplifications and imprecisions. Its biggest limitation may be that it touches only superficially on some important topics, such as the interplay between characters’ various aspects, the phenomenology of their experience, their (trans-)mediality, their culture and history, or their use and misuse in sociocultural contexts. However, I hope that my approach helps to find more detailed ‘piecemeal theories’, case studies and empirical research on these topics (including vivid and subtle interpretations of characters) and suggests possible avenues for further research. Among the particularly interesting and under-researched topics are character constellations and characters’ dimensions as symbols and symptoms. The Character Clock model could also facilitate the comparative analysis of characters in certain media, genres, oeuvres, cultures, epochs, or trends.

In addition to analysing individual characters and works in detail, a typological approach could also be useful for the purposes of some studies. The findings of this book suggest typologies of characters at several levels (see Table 13). Generally speaking, a distinction can be made between diegetic, artificial, symbolic, and symptomatic characters, depending on whether the focus is on the character as represented being (Casablanca), artefact (‘The Child’), symbol (Destiny) or symptom (Jud Süß). Connected to this is the classification according to artefact qualities—for example, individualised or typified, realistic or non-realistic—and character conceptions such as mainstream realism, independent realism, or postmodernism. Types of represented beings include the human and the non-human, the latter falling into natural (animals, plants), artificial (robots, artificial intelligences), and fantastic categories (aliens, monsters, demons, ghosts, animated things). Various properties of represented beings are also emphasised more or less strongly in different works or genres. Some characters, particularly in action, porn, horror, or fantasy genres, are more strikingly physical in their appearance or abilities. Other characters are more psychological, for example in personality studies or mind game films, which present the characters’ interior in detail and often from their perspective. Many characters in melodramas, political thrillers, or social problem films, again, are sociality-centred, as they are primarily characterised through their group affiliations, roles, and relationships. The numerous social (stereo)types in terms of gender, race, age, class, religion, profession, politics, or personality (such as worker, communist, or housewife), as well as conventional genre types (such as cowboy, femme fatale, mad scientist) are more finely differentiated. Basically, a typology of characters could be derived from almost every distinction made in this book, for example by referring to characters’ position within a constellation (protagonists, antagonists; main and supporting characters); to their motivation (social or spiritual needs; selfish or altruistic goals; achievable or unachievable desires); or to their mode of representation (predominantly visual, auditive, or linguistic).

The most general conclusion that can be drawn from this book is that characters have often been theorised and analysed too one-dimensionally so far and that we need to become more aware of their internal complexity and external variety. For far too long, most cognitive and psychological theories have focused almost exclusively on ‘realistic’ mainstream protagonists, and here on their dimension as represented beings. As a result, not only the symbol and symptom dimensions have been neglected in research, but also minor characters or characters beyond the mainstream. Some structuralists and formalists, again, have avoided the interpretation of characters altogether or reduced their analysis to actantial roles or their representation as artefacts. And psychoanalytic interpretations have often not recognised that, depending on the work and its context, alternative models of a character’s psyche may be more appropriate than those of Freud or Lacan. Finally, researchers have often failed to distinguish between the creators’ intended reception of the character, the empirical reception of actual audiences, and the ideal reception in optimally competent or inventive communication. If the argumentation of this book is correct, then this has consequences not only for many theories and critical judgements about characters, but also for empirical research on them. Among other things, it suggests that the results of many media-psychological studies on characters and ‘parasocial interaction’ with them should be re-examined to see whether they do not make inadmissible generalisations. It can be assumed, for example, that the reactions of psychology students to Hollywood protagonists do not cover the entire spectrum of experiencing characters.

In short, this book argues that it is time to expand our field of vision to examine the full spectrum of characters’ features, forms, functions, and experiences. In view of their complexity, one could ask: What is the most important, decisive feature of characters? The answer is: their variety and diversity (see Table 13).

From Theory to Practice: How to Analyse and Interpret Characters