3. What Are Characters, How Are They Created and Experienced? (T)

©2025 Jens Eder, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0283.03

3.1 Definition and Ontology: What Are Characters?

This chapter will be rather abstract and theoretical; it could be skipped by readers who are more interested in practical matters of character analysis. Nevertheless, it is necessary for the following argument to clarify fundamentally what characters actually are.1 This question may seem strange. After all, characters are part of our daily lives, and we deal with them intuitively. We have no problem talking about them, and everybody can even invent their own characters and should, therefore, know first-hand what they are like. This presumed familiarity, however, gives way to a whole series of difficult questions on closer examination. How can I define ‘character’ precisely? What kind of objects are characters if they do not exist in reality? How can we share their feelings and thoughts although they are not real? What features do they have and how do they originate? How are they related to media texts, to human imagination and communication? The answers to these questions determine the way in which characters are analysed, as a look at the various possible statements in common analytical practices shows. We talk about characters in very different ways. For example, even simple statements about Rick Blaine in Casablanca assign him quite heterogenous attributes:2

- Social, physical, and mental features: Rick is the owner of the most popular bar in Casablanca. He has dark hair, is of medium height, around forty, and has an expressive face. A disillusioned idealist, he is cynical, relaxed, sentimental, clever, bold, sensitive, and controlled.

- Relationships with other characters and events in the story: Rick loves the resistance fighter Ilsa Lund; he saves her and her husband from the Nazis.

- Relationships with medial means of presentation: Rick is played by Humphrey Bogart. Framing techniques frequently focus the attention upon him, and the camera often shows him in close-ups.

- Overall forms and functions of the presentation: Rick is portrayed in a differentiated way as an individualised type. As the protagonist, he pushes the action forward.

- Reception and affective potential: Rick is an easily comprehensible character that elicits affection and compassion and whose secrets make him fascinating. Sometimes we even share his memories.

- Comparisons with real persons and characters in other texts: Rick appears to be taller than the actor Bogart actually was. He is parodied or quoted in many other films.

- Larger meanings: Rick stands for a ‘typically American’ combination of sentiment and pragmatism, apparent cynicism, and hidden idealism.

- Typologies, contexts of historical genres, and mentalities: Rick embodies an ideal of masculinity of his period along with features of typical heroes of Westerns and gangster movies.

- Sociocultural functions and influences: the filmmakers intended Rick to be seen as a model American who abandons his isolationist stance and supports the war against Nazi Germany. His ways of behaving and speaking were imitated repeatedly.3

The survey in the previous chapter shows that each theory of characters favours different sets of the above features while neglecting others, depending on their definition of character. If characters are regarded as human-like entities, their personality traits will be the prime topic of investigation. If they are viewed as components of a text, the focus will be on structures of presentation. If they are assumed to be mental constructs, a psychological approach to reception will be applied.

The spectrum of common definitions admits all of these possibilities. Most frequently, the character is defined as an equivalent to a real person or a ‘fictional analogue of a human agent’ (Smith 1995: 17).4 At the opposite pole are structuralist notions that specify the character as a sign constellation, a bundle of textual functions, or a ‘paradigm of traits’ (Chatman 1978: 107ff.).5 The definitions are so antagonistic that one can neither presuppose some intuitive understanding nor simply accept one of the definitions, since most of them prove to be problematical. The divergence of character conceptions has led to numerous misunderstandings and a lack of exchange between theories. However, it is also not helpful to leave the concept of character completely open, because it needs to be clarified if different theories are to be systematically linked.6

A look at current character definitions reveals three central areas that need to be clarified: firstly, the anthropomorphic quality of characters, secondly, their ontological status and, thirdly, their relationship to neighbouring concepts like role, star, or actant.

The most widespread definitions correspond to the scheme ‘a character is a fictional human being’, but this is obviously too narrow, because the spectrum of characters also includes animals, aliens, gods, ghosts, robots, monsters, magical, or other non-human beings. Although most characters exhibit human traits, they can also differ significantly from humans in their mode of existence, physicality, sociality, or mental capacity, and their significance can lie precisely in questioning the criteria of being human. Even definitions that understand characters not as human persons, but more generally as beings capable of acting or taking action, are still too narrow, as some characters can also remain completely passive or immobile and only undergo mental processes.

However, there is one decisive feature (and also one decisive prerequisite for action) that is in fact common to all characters: they possess an—at least rudimentary—inner life and the capability of relating to objects with their conscious minds, for instance, to perceive, feel, or desire something. In the philosophy of mind, this ability to mentally represent objects is called intentionality. While in everyday life ‘intentionality’ generally refers to deliberate or purposeful action, in philosophy the term is used in the broader sense of the directedness of something at something (Searle 1983, 2004: Chapter 6) or ‘the power of minds and mental states to be about, to represent, or to stand for, things, properties and states of affairs’ (Jacob 2019). Furthermore, for a fictional being with the capacity for intentionality to be called a character, it must be recognisable. Extras whizzing by in the background or merging into crowds will not usually be considered characters. A first working definition might therefore be:

A character is a recognisable represented being with an inner life—more precisely: with the ascribed capacity of mental intentionality.

This definition is somewhat broader than in earlier editions of this book because it replaces ‘fictional beings’ with ‘represented beings’. In this way, the definition also includes characters from documentary film or other non-fictional media. Nevertheless, it makes sense to first look at the more widely discussed (and more ontologically difficult) standard case of fictional characters here, of intentional beings that are represented in fictional media such as feature films.

So, what are fictional beings, what is their ontological status? In analytical philosophy all those objects are considered fictional that are represented by fictional textual utterances (Künne 1983: 291ff.; the German original differentiates more precisely between ‘fictitious’ [fiktiven] objects and ‘fictional’ [fiktionalen] texts, but this does not translate well into English). Fictional are all those descriptive texts for which their producers do not claim that the described objects really exist or that these objects really possess the properties ascribed to them (see Gabriel 1975; Searle 1979). Rick Blaine is therefore fictional because the movie Casablanca never asserted that he really existed. And the characters of historical feature films like Cleopatra or Napoleon are fictional because their makers do not insist that their real counterparts actually possessed exactly the same properties, the same looks and lives, as the actors or animated figures representing them in the film.

Thus, characters are marked as fictional by certain communicative contexts and media practices and as non-fictional by others. Viewers expect documentary films and other non-fictional media to correspond to reality, and their claims to concrete factual truth can even lead to legal disputes, for example over defamation. Fictional films, on the other hand, are seen as games of the imagination, inviting viewers to imagine worlds which, as the credits often emphasise, are ‘free inventions’ and in which any resemblance between their inhabitants and real people is ‘purely coincidental’. Between fiction films and documentaries there are hybrid forms such as docudramas, reenactments or autofictions, whose degree of fictionality must be assessed in each case.7 This definition of fictionality, which is pragmatic, context-dependent, and allows for differences of degree, applies not only to characters, but also to everything else in fictional communication, to entire fictional worlds.

A simple answer to the question of the ontology of characters might therefore be to define them as elements of such fictional worlds and refer further clarification to fictional worlds theories in literature and media studies.8 Here, a fictional world is understood as a system of non-real, possible states-of-affairs, as a framework of objects, individuals, space and time, events, laws, etc. that is construed by a fictional text (Doležel 1998: 16–23; Ryan 2001: 91). This reference to fictional worlds, however, cannot solve our problem. To specify fictional worlds ontologically, scholars refer to philosophical theories of possible worlds, which are themselves completely at odds regarding their ontology.9 Theories of fictional or possible worlds thus cannot provide any clarification of the mode of existence of characters, because they are themselves battling with equally massive ontological problems.

As the scholarly discourse on characters is older and richer than the one on fictional worlds, it is advisable to make it the point of departure. The four central positions on the ontological status of fictional characters are extremely controversial.10 (1) Semiotic theories consider characters as sign constellations or textual structures.11 (2) Cognitive approaches assume that they are conceptions of imaginary beings in the minds of viewers.12 (3) Some philosophers believe that characters are abstract objects existing beyond material reality.13 (4) Others again think that they do not exist at all.14 There are also attempts to connect some of these assumptions with each other.15 Such considerations may seem unnecessarily abstract and dispensable, but they are not, because each position has far-reaching consequences for the practice of analysing characters. Those who view characters as textual structures will primarily examine the media text. Those who view characters as mental constructs, on the other hand, will focus instead on the audience’s reception processes. And if characters are abstract objects or if they do not exist at all, then the question arises as to what one is actually analysing and talking about. Every definition thus entails a particular perspective and methodology. The pros and cons of the different positions cannot be dealt with in detail here, but I shall at least sketch out a few of the essential arguments.16

The assumption that characters are ‘signs’ leads to problems, whichever of the meanings of this word is selected. Fundamentally, three different meanings of ‘sign’ may be distinguished: as a thing standing for something else, as a physical carrier of signification, and as a relation, for instance between a signifier (expression) and a signified (content). Now characters may often stand for something else and thus function as secondary signs (e.g., as an allegory). But this is only a functional specification, not an ontological one. Ontologically, characters cannot be equated with any dyadic or triadic sign relation according to de Saussure or Peirce.17 It appears to be counterintuitive that they should be abstract relations between signifiers and signifieds or between sign carriers, referential objects, and interpretants, especially since the question of how to define each of these relata would lead to great difficulties.18 Could they be one of these relata? Certainly not the material sign carriers, because we speak differently about characters and concrete textual structures. In contrast to ‘Rick Blaine has dark hair’, the sentence ‘Rick is this set of images and sounds’ sounds strange. More importantly, characters may exist apart from their original text and its specific set of signs: after all, film characters can also appear in other films, novels, or computer games. Characters therefore seem to be a complex meaning of signs rather than these signs themselves.

However, this meaning cannot consist in the individual conception of a character formed by a particular viewer as suggested by psychological approaches (e.g., Persson 2003; Schneider 2000). The subjective conceptions or mental models of Rick Blaine formed by different viewers of Casablanca will certainly diverge from each other. They are not the same, neither numerically nor qualitatively, and they change during the film. The character Rick Blaine, however, remains the same (although Rick’s personality changes). Viewers may even admit that they have formed a wrong picture of Rick. This suggests that particular norms determine when an individual mental representation of a character is ‘right’ and corresponds to the actual character. If characters are based on normative assumptions and abstractions, however, which are derived from an analytical perspective, then a character cannot even be an abstract type of mental representations. For a type in the sense of a mere generalisation based on the mental models of different viewers—i.e., based on what remains the same with these viewers—would no longer be normative but descriptive.

The comparison with ideas or texts representing real beings also contradicts the notion that characters are mental representations of viewers or complexes of signs. Neither a television programme about the former Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel nor the image that I as a viewer create of her are identical with Merkel herself. Fictional media do not correspond completely to this pattern, as characters do not exist like persons in material reality. But the analogy supports the assumption that signs and ideas are only external or internal representations of characters, not the characters themselves. We can say that Rick is portrayed by Bogart in certain sequences of the film Casablanca and that we have formed an idea of Rick on this basis, but we cannot meaningfully claim that the film sequences with Bogart or our individual ideas are identical with Rick. So, the provisional conclusion is:

Characters must be distinguished from their mental and textual (medial) representations, even if they are based on them.

Since the concept of representation is often misunderstood, I would like to emphasise again that representations are obviously not to be understood as abstract propositions here, but as mental or medial entities with a material basis. Mental representations or ideas of a certain character develop in the minds of the audience through various mental processes. Textual (medial) representations of characters, again, include all those textual elements that contribute essentially to those mental processes by evoking or influencing ideas of characters: images of the character’s body, dialogues about their personality, or musical leitmotifs recalling the character. Both mental and textual representations are clearly necessary for the genesis of characters, but they are not identical with them.

Thus, the question of what characters really are arises again. Or do characters really not exist at all and talking about them is merely the result of a linguistic illusion? Some philosophers assume that all statements about characters are ultimately either statements about texts or about mental representations (e.g., Künne 1983: 310–14; Currie 1990: 158–62). ‘Rick Blaine loves Ilsa’ would then mean: ‘According to the film Casablanca, Rick loves Ilsa’ or ‘Casablanca triggers the idea that Rick loves Ilsa’. Whenever we believe to be analysing characters, we would in reality be examining external or internal representations although it would still remain unclear in what form this might happen. In addition, not all utterances are so easy to resolve. How could we, for instance, transform the following sentence: ‘Rick Blaine is a multidimensional character invented by Murray Burnett, played by Humphrey Bogart, often shown in close-up shots, meeting an ideal of masculinity of his period, therefore re-emerging in several film parodies’? Here a simple introductory formula like ‘according to Casablanca’ is obviously not sufficient. The attempts at a reformulation of such complex statements in logical language by analytical philosophers therefore result in almost endless sentences twisted into something like a Gordian knot (for examples of that, see Currie 1990: 171–80).

There is, however, an alternative that will do justice both to practical character analysis and the intuition that we do in fact talk about characters. It consists in conceiving of characters as abstract social objects, as for example in Amie L. Thomasson’s ‘artefact theory’ of fiction (2003). According to this theory, characters are comparable to laws, theories, or works of art: they are cultural artefacts created by textual utterances. Characters are abstract because they can neither be handled materially nor located spatio-temporally; they still are, however, contingent elements of our real world that originated at a particular point in time. Similar views are held by scholars with varying backgrounds.19 My own version of the proposition in the German first edition of this book was: fictional beings are communicative artefacts that are created by the intersubjective construction of mental representations of certain beings on the basis of fictional texts. However, this proposition (developed in more detail in Eder 2008d) can be broadened to cover also non-fictional characters of documentaries or other non-fictional media (see Eder 2014, 2016; Plantinga 2018b):

Represented beings are communicative artefacts that are created by the intersubjective construction of mental representations of certain beings on the basis of texts.

As mentioned before, ‘texts’ are understood here as complex but coherent sign utterances or units of communication that are based on and shaped by the material, sensory, semiotic, and pragmatic specificity of certain media. For instance, filmic texts are shaped by the specific affordances of moving images and sound used as predominantly iconic signs in the pragmatic contexts of cinema.

Thus, characters do exist, but they are neither signs in the text nor subjective ideas in people’s heads. They are abstract objects created through communicative practice and are in this way made part of an objective social reality—like numbers, laws, theories, or money. Karl Popper’s philosophical ‘three worlds theory’ would assign them neither to world one of the physical-concrete nor to world two of the subjective-mental, but to world three, the world of objective cultural contents that exist independently of individual minds (cf. Popper 1972: 153–90). This position can best be made clear by showing how characters originate. The clarification will, at the same time, provide indications of how character analysis should proceed properly and how different theories of character could be combined with each other. In the following, I will focus on fictional characters in feature films. But it should be noted that most of what I will say about them could also be applied to non-fictional characters or to characters in other media.

3.2 Communication and Meaning: How Do Characters Originate?

Characters are created through communication: through interactions in which texts are produced and received in order to influence mental states such as thoughts and feelings, and through these often also behaviour.20 To put it more precisely, characters appear in two very different forms of communication: representational and meta-representational communication. Representational communication presents certain real or invented worlds and objects, while meta-representational communication (or simply meta-communication) focuses on the processes and results of representational communication. This is most evident in the field of fiction. Fictional characters appear in fictional and meta-fictional communication.21 On the fictional level, feature films are produced and viewed. The films serve as an invitation to imagine, as tools to evoke ideas and feelings about invented worlds in the viewers and to let them experience these worlds. Some of the film structures are character representations, intended to induce intersubjective processes of character reception. In this way, fictional communication forms the basis of characters that may subsequently, on the level of meta-fictional communication, become the subject of conversations between viewers, of advertising, criticism, analysis, and interpretation. Usually, it is only at this stage that assertions about characters are made, that they are, for instance, said to be stereotypical or differentiated. Fictional characters are thus constituted through fictional communication and then become objects of meta-fictional communication. Or more generally, if we want to include not only fictional but also non-fictional characters: all characters are constituted through representational communication and then become objects of meta-representational communication.

I shall begin with the first level. The essential prerequisites for the emergence of characters are:

- producers and recipients who form ideas of characters;

- a text that includes semiotic representations of characters;

- a practical context of representational communication; and

- collective mental dispositions and communicative rules.

The genesis of film characters starts when filmmakers begin to develop ideas of the beings they want to portray—usually in a collective process in which writers, directors, actors, and other members of a film team exchange their individual ideas about a character and shape the film with the intention of evoking similar character conceptions and mental processes in the imagined audience. This kind of intended character reception will affect the film’s creation in a mostly intuitive way. For example, dialogues will be rewritten, actors cast, or failed scenes removed to achieve the desired effects. When the film is finished, it is distributed, with peri- and paratexts such as posters, trailers, or press announcements designed to give the audience a preliminary idea of the characters.

Production and distribution of the film make up the first large part of the communicative context; the second part consists in the film’s reception and appropriation. Viewers act in selecting the film, watching it, in various places, at varying times, and for various motives. They need not be the targeted audience, nor need the film trigger the expected reception. The filmmakers may want to enlighten the spectators may prefer to be entertained. They often use the text in ways that diverge from the planners’ intentions, make it function differently. Besides, people of different age or gender, and members of different cultures, groups, and milieus, may experience the film in different ways. The character conceptions, imaginations, and evaluations of various viewers may thus differ from one another and from the intentions of the filmmakers.

At a basic level of understanding, however, audience reactions will most often be fairly similar. Even people who perceive, understand and evaluate Rick Blaine differently—who, for instance, admire him or take him to be a self-pitying macho—will still generally agree about his bodily features and actions. For most viewers, the film will evoke processes of character reception that are in many ways similar to those intended. Such intersubjective effects of the representations of characters are fundamentally conditioned by collective mental dispositions ranging from innate modes of reaction to culturally and media specific knowledge (Persson 2003: 8–13). Whenever spectators respond to a film and filmmakers attempt to anticipate their responses, they do so on the grounds of physical and mental preconditions with individual variations but also common biological foundations, cultural influences, shared experiences, and comparable reception situations. Some of these dispositions, such as folk psychology or social categories and stereotypes, are particularly relevant for character reception (see Chapter 5 and Chapter 6).

The similarities between the mental dispositions of producers and recipients are not merely a matter of coincidence, nor do they automatically lead to similar reception processes. Instead, the context of communicative action correlates them with each other, and they are intentionally brought into correspondence.22 Filmmakers and film viewers in this way mutually generate certain facts of a social reality, including films with an intersubjective meaning; communication forms like the feature film; categories and genres; the institution of the cinema. All these are ‘observer-dependent’ facts (Searle 2001: Chapter 5) that would not exist without a conventional agreement between the participants—in contradistinction to the objects of the natural sciences (at least to realist theories of science). They arise in intersubjective frameworks of action through collective intentionality and the attribution of functions by means of constitutive rules (cf. Searle 2001: 139–51).

Collective intentionality means here that filmmakers and spectators pursue common goals on the basis of shared presuppositions that include very general mutual expectations: the screening of the film is intended to trigger mental processes, among them the imagination and experience of invented worlds and characters. The material object film, a succession of images and sounds, is thus collectively assigned this function. Some theorists speak of a ‘communicative contract’, an implicit agreement between filmmakers and spectators (Casetti 2001; Wulff 2001c). Genres, star systems, posters, or trailers promise the spectators experiences with particular gratifications, among them information, orientation, and learning; entertainment, relaxation, and emotional stimulation; development of personal identity; social integration and interaction (cf. Schramm and Hasebrink 2004: 472). This kind of communicative contract is linked to specific sanctions: filmmakers must be prepared to tolerate bad criticism, and spectators can be accused of having failed to understand the film correctly. The contract also implies that the promises of gratification will be kept as long as the spectators orient themselves by the reception as intended by the filmmakers. This is only an offer and not a command: the spectators are free to view the film in different ways and ignore the filmmakers’ intentions. But then they cannot hold the filmmakers responsible if the gratification is not delivered. It is therefore part of the implicit contract that viewers try to comply with the intended reception at least in some sort of indirect way.

The possibility of approximating the intended reception and both the differences and the commonalities of reception processes are essentially grounded in the complex spectrum of physical and mental properties of the spectators, which extend from biological or bodily tendencies toward certain reactions to culturally and individually specific sets of knowledge and affect, biases and preferences. To a certain extent, universal dispositions such as innate systems of perception and affect automatically lead the spectators to experience the intended reaction, for instance that they recognise represented beings correctly. On this basis of automatic perceptual tendencies, a further network of more complex, higher-level processes of understanding comes into play, often concerning that which is not directly perceptible: What is the character planning to do, what is its moral quality, what does it symbolise, is its representation meant to be ironical? Processes of this kind require implicit knowledge and spontaneous inferences on the basis of communicative rules. Some of these rules are constitutive rules of the form: X in context K means Y (Searle 2001: 148). Whenever a person makes certain noises with their mouths, then this is taken to be a promise of marriage in our culture; whenever lovers switch off the lights in an old Hollywood film, they are probably going to have sex; whenever a cartoon character is shown with dollar signs in place of its eyes, it is meant to be greedy. However, such cultural rules, conventions, schemata, or codes (terminologies vary here) in no way uniquely determine the reception process; they are only points of orientation that may suggest associations or help make the intended reception comprehensible through inferences. Thereby spectators primarily draw on stocks of knowledge that are easily accessible and appear most relevant.

The communicative context plays a role in determining which areas of knowledge are used. Among the foundations are some general principles of communication, for instance the assumption that the film was made so as to serve particular purposes of the communication situation (e.g., entertainment, information).23 The mutual recognition and consideration of the given communicative contexts and prerequisites takes place on the basis of communication rules. The filmmakers try to anticipate the reactions of their audiences; the spectators try to comprehend the intentions of the filmmakers. Depending on the kind of film communication, the responsibility may be shifted: producers of mainstream films try to please their target audiences as far as possible, so these audiences can expect to be ‘served’ without having to bother about the intentions of the producers. Conversely, the spectators of complex auteur films are conventionally expected to use knowledge about the filmmakers and their situation in order to understand the films. Thus, special features of film communication and its different forms must be taken into account, including that filmmakers and spectators are not in direct contact; that a film must not be seen only as a message but also as a commodity, a toy, an instrument of the senses; that the levels of narration and meaning of a film can be multifaceted; and that indirect meanings and sensory processes often play a central role (metaphor, irony, aesthetic experience). Fictional communication, as a rule, is more complex and open in its meaning than direct instrumental everyday communication; it is also split into different forms and practices. Generally, the activities of making or understanding fiction are also subject to communicative goals, norms, and conventions. They are geared to fulfil particular functions and therefore expected to meet collective dispositions and communicative rules to do so. This is the foundation for the constitution of characters as intersubjective objects.

A more precise understanding can be achieved by considering meta-fictional or meta-representational communication. In this context, characters are the prime object of debates between spectators, filmmakers, critics, interpreters, and censors. All the aspects of representational communication are dealt with: one may discuss the filmic means used to depict Rick in Casablanca, how Rick should be understood from the point of view of the filmmakers, how spectators actually reacted to him or might hypothetically respond to him. Beyond the responses of individual viewers, one may try to explore group-specific responses: How do men or women, Americans or Moroccans, perceive Rick at a certain point in time?

In all these cases one, makes essentially empirical hypotheses about the actual, probable, or intended reception of characters by individuals or social groups. Empirical statements of this kind play a role in film creation in order to gauge the future character reception (for example, in test screenings), and in sociocultural analyses in order to assess the effects of characters (for example, in youth protection committees). They may be supported by production and reception data, such as audience surveys, focus groups, or interviews with filmmakers. When available, they may provide decisive arguments for or against the asserted form of character reception.

Other statements about characters cannot be confirmed empirically, but need to be made plausible in other ways. Especially in film interpretation and criticism, one may encounter propositions that are openly or covertly normative or evaluative: character representations are supposed to have been understood ‘correctly’ or ‘wrongly’; certain interpretations are called ‘better’, ‘more adequate’, or ‘more interesting’ than others. Such statements obviously measure the actual reception of characters against certain ideals. But what are those ideals and what standards apply? In other words, what could be a basis for an intersubjectively valid meaning of representations of characters? Three criteria are most often mentioned: the rules of communication, the intentions of the producers, and the interests of the recipients (cf. Jannidis et al. 2003).

A first criterion of ideal character reception could be its optimal correspondence with communicative rules and other collective dispositions. However, this would often leave the reception more or less open; it would furthermore raise the question as to what dispositions and rules are relevant in a given case. After all, there may be great differences between the dispositions and rules of different times and cultures—and thus between filmmakers and spectators. The intentions of filmmakers might be used as an additional or alternative criterion. Author-intentional theories of meaning assume that the ideal reception matches the reception intended by the creators; character representations should then be understood as the authors explicitly intended or implicitly presupposed them to be. Other positions, by contrast, emphasise the legitimate interests of the spectators: perhaps it is more interesting, entertaining, or enlightening to understand character representations in ways different than the producers intended.

The position taken here is that not one of these criteria is in itself sufficient to determine the ideal character reception, but that all three must be taken into account.24 This is already implied by the framework of communicative action and its aims. Communicative action is ideally successful precisely when the interests of all participants, the communicators as well as the recipients, are optimally satisfied according to the given communicative rules. This would be the case when the viewers, due to their communicative competence, fully realise the intended reception and precisely through this also achieve the highest possible measure of gratification. Ideal communication in this form will most probably never be reached. How deviations from the ideal are assessed depends on how much weight is given to communicative rules, intentions of authors, and interests of spectators in specific contexts of film communication. In mainstream movies, for instance, the prime goal is to satisfy the spectators, even against filmmakers’ intentions. Here the film is primarily a commodity and the client is king. For the auteur film, in contrast, the intentions of the filmmakers conventionally pull greater weight. It may be generally stated that normative statements and assertions about ideal character reception can only be justified by weighing up the three criteria, and that they thus depend on the particular contexts and practices of film communication.

A preliminary conclusion might then be: firstly, in meta-representational communication such as character analysis, empirical hypotheses are constructed about the probable, factual, or intended character reception of concrete (groups of) recipients—how might Rick be understood by future viewers; what conceptions of Rick would spectators of different times, cultures, and milieus develop; how did the filmmakers intend him to be understood? Secondly, in meta-representational communication normative assertions about ideal character reception are at least implicitly presupposed—what would an ideal understanding of Rick be, taking into account the intentions of the authors, the interests of the spectators, common dispositions, and communicative rules and contexts? Thirdly, statements about the characters themselves can be explained on this basis: they are based on implicit assumptions about the ideal character reception of competent viewers. Since the viewers’ ideas of a character change over the course of a film, statements must furthermore generalize in order to ascribe certain largely stable characteristics to the character itself.

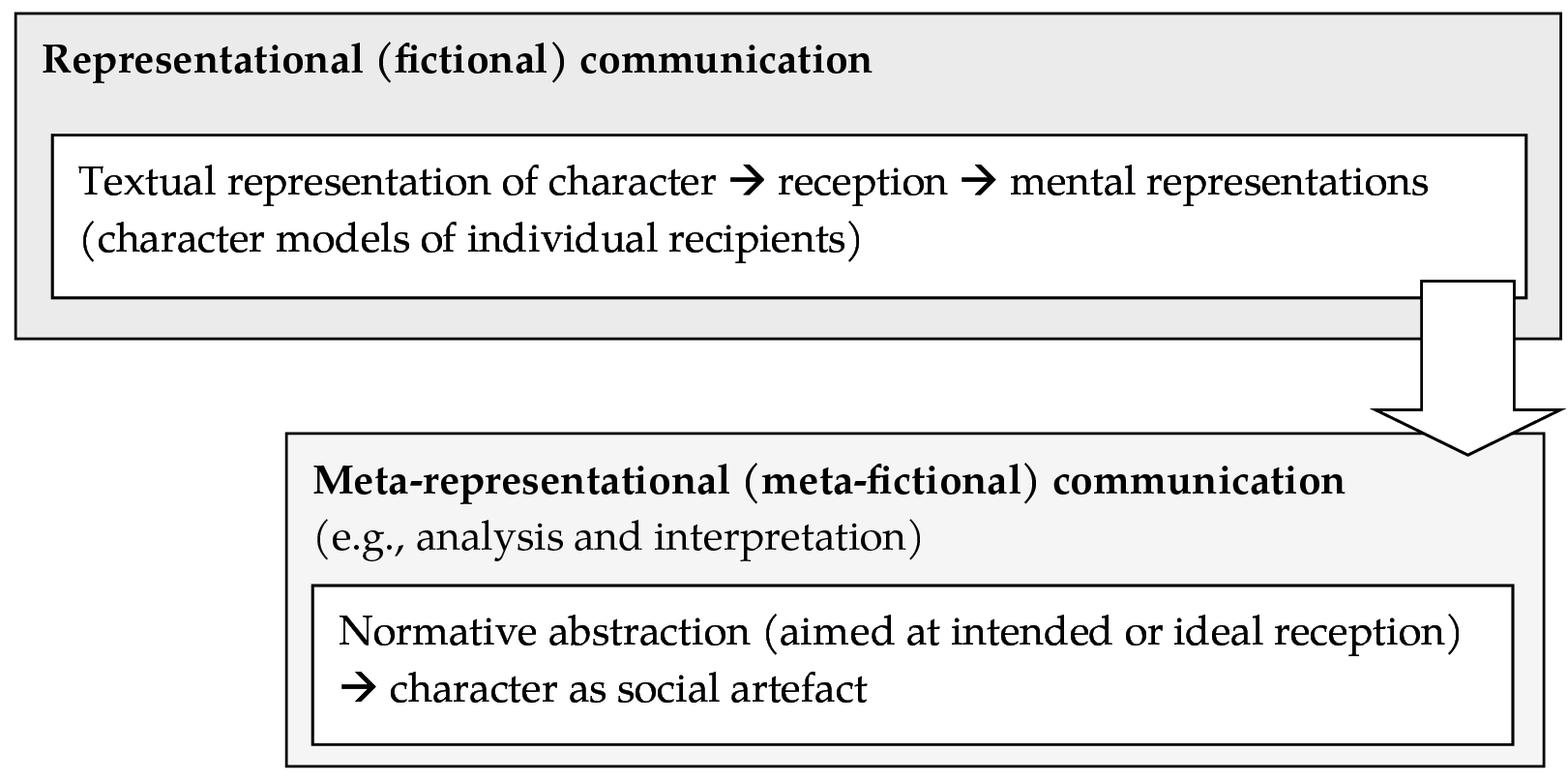

Diagram 1 From individual mental representations of a character to the intersubjective character

as a social artefact

The creation of characters as communicative artefacts thus proves to be a multi-layered process (see Diagram 1). At the start of fictional (or more generally: representational) communication, producers create representations of characters in order to evoke imaginations of those characters in the recipients. Intersubjective correspondences of these imaginations are made possible by an interaction of collective dispositions of perception and experience, communicative rules, contextual knowledge, and the consideration of authors’ intentions and recipients’ interests. The same factors also enable the reconstruction of ideal character conceptions in meta-fictional (or more generally: meta-representational) communication. Abstracting from these ideal character conceptions finally leads to the character itself as a communicative artefact, an intersubjective abstract object, and a component of the meaning of the text.

The way in which characters appear and are discussed in meta-representational communication has far-reaching consequences for their analysis. The first concerns the scope and objects of character analysis. When characters are analysed, not only are they themselves discussed, but also all other aspects of representational (fictional) communication that relate to them, including the textual means and forms of their representation and all varieties of their reception (individual, group, ideal, intended, or probable reception). In previous character theories, statements about these different objects of investigation have not been clearly distinguished. The characters themselves have often been confused with representations or imaginations of characters. Pointing out the differences between such objects makes it possible to explain enduring misunderstandings between competing theories of character and to integrate their results. Roughly speaking, structuralist theories have concentrated on character representation, cognitive theories on character reception, and hermeneutical theories on the characters themselves. The different theoretical strands might thus benefit from each other exactly because they have focused on different aspects of the object domain, as will be shown later.

A third consequence is that the features and structures of characters can at least partially be derived from the structure of their mental representations. Characters are not mere signs but are based on mental models of beings with physical, psychological, and social features, which are imagined based on the perception of the film. This means that character reception and mental character models are of central importance in the analysis. The next chapter will therefore deal in more detail with character reception and try to describe what makes it intersubjective. Film communication presupposes some universal dispositions of perception, comprehension, and affect, and since only communicative norms can guarantee the intersubjectivity of character reception, statements about characters will always be implicitly normative. Precisely because universal dispositions and collective norms are widely shared, this kind of normativity generally remains inconspicuous and rarely provokes controversy. However, when problems with characters arise and their proper analysis is required, then statements can ultimately only be substantiated by reconstructing ideal character conceptions and processes of abstraction, and by weighing up against each other collective dispositions, communicative rules, intentions of authors, and interests of spectators in specific contexts of communication.

Thus, a pragmatics of communication provides the most convincing basis for understanding characters. On this basis, characters can be defined as recognisable represented beings with the attributed capability of intentionality. They are constituted as cultural artefacts through representational communication and discussed in meta-representational communication. Characters are fictional when films are fictional and do not explicitly or implicitly claim that concrete beings with the same features exist in reality (even if they have been modelled on real persons).

One could also say that characters are elements of the meaning of a text, whereby ‘meaning’ must be understood as an intersubjective, ultimately normative construct. When we talk about characters, we always implicitly assume the successful joint construction of similar mental models in the communication between authors and audience. The success of such communication is determined based on a set of criteria that range from largely universal bodily dispositions (we could all see that the character has dark hair) to culturally specific conventions (for example, concerning the understanding of the characters’ motivation). Due to processes of normative abstraction according to such criteria, characters are not simply generalisations of the diverse character conceptions of individual recipients—of what is the same in all these individual ideas—but of what should be the same in all of them. In short, characters are grounded in the normative abstraction of ideally intersubjective character models.25 As communicative artefacts, they are multidimensional objects of meta-representational communication: When analysing characters, interpreting them, or simply talking about them, one can not only ascribe certain traits, actions and relationships to them as represented beings, but also describe how they are shaped as artefacts by textual strategies, or examine how mental models of them emerge in various types of reception.26 The following chapters will describe how these different aspects of character analysis are interconnected and what the corresponding structures of characters are.

The ontology of characters outlined here could be extended to entire represented worlds (mostly discussed as ‘fictional worlds’ or ‘storyworlds’): every such world is—just like a character—a communicative artefact that arises through the intersubjective formation of mental representations by means of (fictional) texts. Storyworlds are naturally much more complex structures than individual characters. They form a total framework, a system, which comprises not only characters and their interrelations but also all their spatio-temporal environment, inanimate objects, situations and events, norms, and principles. The structures of this system have been described in detail in the theories of fictional worlds, and character analysis might well profit from them.27 As represented beings with intentionality, characters are particularly important and prominent inhabitants of represented worlds. Similar relationships hold between characters and stories (see also Chapter 1). A story contains a chain of events from a represented world that usually consists primarily of actions of characters. Ontologically, this chain of events is, just like the world to which it belongs, a communicative artefact that is mentally represented in the form of event conceptions or situation models. Character theory is thus not only closely connected with more general theories of fiction and narration, worldbuilding and storytelling, but can make relevant contributions to them. The conception of character presented here makes it also easier to situate the character concept in a field of related concepts with which it is often confused and to distinguish characters more clearly from persons, actors, star images, actants, parts, or roles.28

The question is now how characters and the aspects of communication connected with them can best be investigated in a systematic way. The essential purpose of communication and the precondition for the emergence of characters lies in reception, in the mental processes that emerge by interacting with (media) texts. The following chapter will therefore deal with how characters are (re-)constructed and experienced in reception processes.

3.3 Reception: How Are Characters Understood and Experienced?

How characters are perceived, understood, and experienced is crucial for their analysis. Firstly, the reception of characters is of interest in itself and plays a central role for the overall impact of a film (or other media text). Secondly, characters’ traits can only be discovered through the reception process. The first question is therefore what processes produce the effects of characters. How is Rick Blaine perceived by the viewers, why is he admired or pitied? Whoever poses a question of this kind usually presupposes that the character is already unproblematically given for the audience and asks what further reactions it might trigger in its members.

However, the preceding chapter has uncovered a second and more fundamental meaning of character reception. The text, as a communicative tool, is functionally determined by its reception. Its structures are—beyond a purely physical description—objectively given only to such an extent as the properties of the participants in communication allow. Therefore, even the simplest attributes of characters can ultimately be revealed systematically only by recourse to ideal reception processes: how else could the proposition be justified that Rick did indeed act heroically and did not want to revenge himself on Ilsa? Or that he slept with Ilsa although this was not shown? Characters are created through imagination in representational communication. Watching a film triggers imaginations of a world and its inhabitants in the viewers. Statements about characters ultimately refer to such imaginations and to normative assumptions about their intersubjective validity. Propositions about Rick can only be verified if I know how ideas of Rick are formed during the viewing of Casablanca and under what circumstances they can be accepted as correct. Mental representations thus make up a basis of the analysis of characters. At least in problematical cases, the analysis should be capable of making the implicit assumptions about them explicit.

These mental representations (or ideas, imaginations, mental models) of characters are, at the same time, embedded in larger frameworks of reception. I shall subsume any perceptual, cognitive, and affective processes that contribute to the formation of mental character models or contain them under the concept of character reception. This is broader than the notions of other theories, such as ‘parasocial interaction’ (Hartmann, Klimmt, and Schramm 2004) or ‘character engagement’ (Smith 1995). Character reception begins even before the first reaction of viewers to represented beings like Rick sets in; it begins as soon as they start to reconstruct such beings from their first perceptions of character representations in the text. To summarise: a character is derived from mental character models, and these are part of the process of character reception, which in turn is embedded in the context of film perception and reception as a whole. The result is the following chain of indications:

Reception of the entire film → character reception (as part of film reception) → viewers’ subjective character conceptions → intersubjectively given character

All systematic character analysis, therefore, presupposes a model of reception.29 Anyone who wants to investigate characters must know how they are perceived, recognised, understood, and experienced. Only by recourse to a model of reception can it be uncovered whether characters are incomprehensible or likeable or why audiences empathise with them. But even when reception processes are not as directly involved as in connection with statements about characters’ physical, mental, or social qualities, propositions cannot simply be justified by reference to the film. It is precisely when films and characters are understood in different ways by different recipients that analysis is necessary.

The reception of characters encompasses diverse kinds of mental experiences, which can provisionally be arranged in the following way:

- Perceptual and sensory processes: perceiving or sensorially experiencing ‘the character itself’ or representations of the character; perceiving something connected with the character (objects, musical leitmotifs); perceiving the same things or situations as the character does.

- Higher cognitive (imaginative and epistemic) processes: developing an idea of a character, attributing traits to it; apprehending the external experiences and the inner life of a character; understanding its behaviour and its motives; sharing its opinions or thoughts; contemplating it; associating something with it; recognising its symbolism or its thematic content; considering it as the counterpart of an interaction; discovering similarities between a character and real persons; comparing oneself with it; analysing its structure and its mode of presentation.

- Affective processes: affectively responding to representations of the character, or to its appearances and movements; developing feelings toward a character; sharing its hopes and fears; experiencing similar emotions, feeling with a character, empathising with it. This sphere of the affective—explored in detail in Chapter 13 and Chapter 14—includes sensational and bodily processes (e.g., sensations induced by the representation or imagination of a character; imitation of movements; sharing the experiences of a character, such as dizziness in Vertigo) as well as conative processes (desiring the character; wishing certain things to happen to it; projecting goals on it; wishing to possess the character’s abilities; sharing its goals etc.).

The perceptions, cognitions, and affects in reception can only analytically be distinguished, but are actually closely interwoven.30 Apart from such transitory experiences, spectators may develop certain persistent dispositions and attitudes relating to characters, such as stable images of their personalities; expectations of actions; sympathies, antipathies, or indifference.

This provisional draft of the field of character reception will be systematised later; it already makes clear, however, that much-debated concepts like ‘identification’ or ‘parasocial interaction’ alone are insufficient for a systematic examination of character reception. Moreover, the provisional list already indicates why approaches to film reception that are based in direct perception theory or enactivism must fail—they cannot account for many more complex, higher-level mental processes.

A theory of character reception should describe its general structures, processes, and products comprehensively and systematically and answer at least four basic questions: What dimensions or levels does character reception have? What are its presuppositions in relation to the film, the viewers, and their contexts? How do character conceptions originate, and what role do they play in other conscious processes? How are they built up and structured (as mental representations)? A number of specific problems have been particularly controversial for reception theories (Staiger 2005: 7): How are cognitive and affective, conscious and unconscious, innate and learned aspects of reception related to each other? Are mental representations of characters related more to language or images, or neither? What is the decisive factor: text, spectator, or context? How active are the spectators? What are the basic and crucial structures of their minds? How does character reception relate to the perception of real persons? What are identification and empathy? What differences are there between characters in film and other media like literature?

Various theories approach these questions in very different ways (see Chapter 2): hermeneutics and reception aesthetics emphasise the historical differences between the horizons of expectation of producers and recipients and the necessity of the interpretation of characters. Phenomenology starts from the individual recipient’s perspective and offers detailed descriptions of subjective experiences (but has difficulties in grasping processes that lie below the threshold of conscious experience). Semiotics regards reception as a process of semiosis, as largely culturally moulded sign processing and text decoding governed by conventional codes. Psychoanalysis sees the relationship with characters and producers as determined by the dynamics of drives in subjects, the conflict-laden relations between the id, the ego, and the superego, by conditioning in early childhood and experiences of lack as well as processes of desire, repression, or identification. Post-structuralism combines primarily semiotic and psychoanalytical models, whereas the cultural studies approach stresses the role of medial and sociocultural contexts.

These approaches dominated theory formation until developments in the cognitive sciences in the mid-eighties provided new impulses and increasingly became the basis for several sophisticated models of the reception of characters.31 The most important contribution of cognitive theories of reception to solving problems of character analysis is that they model the fundamental processes of the creation and reception of characters in the first place, whereas most other approaches take characters as something simply given. In my view, cognitive theories offer further advantages (Eder 2003a), in particular greater conceptual clarity and differentiation, compatibility with empirical research, integration of scientific findings, and an explanatory approach that is more comprehensive and better capable of explaining the relationship between media reception and everyday perception. Of course, other approaches have crucial advantages, too, which should not be lost. By keeping the cognitive foundation as open and inclusive as possible, many of their findings may be integrated.32 As the cognitive approach is of relevance to many aspects of my argumentation, I shall now present it in greater detail.

Cognitive Theories of Reception

Since current cognitive approaches are still frequently misrepresented, it is necessary to first clear up some possible misunderstandings:33 first, recent cognitive theories by no means consider only conscious, higher-level cognitive processes. They model reception as a psychophysical, partially preconscious process consisting of interlaced cognitive, affective, perceptual, and sensory responses to external or internal cues. Even attention towards certain textual elements may already depend on affective factors. Second, cognitive theories see cognition not as a detached computer algorithm, but as shaped by dynamic interactions between brain, body, and both physical and social environments—as embodied, embedded, and often also extended and enactive (4E cognition).34 Consequently, the experience of films, stories, and characters is an active, bodily operation of completing, imagining, conjecturing, coherence-making, and sense-searching, embedded in specific communicative situations and co-determined by media structures and viewers’ motives. The processes and results of this operation may diverge significantly from the everyday perception of real environments. Third, cognitive theories turn increasingly to sociocultural and interactional factors of cognition, including stereotypes, ideologies, power relations in society, or affordances of certain media (e.g., van Dijk 2015; Brylla and Kramer 2018). Fourthly and crucially, cognitive theories are not homogeneous but form a diverse field. For example, when describing processes of reception as ‘information processing’, the textual ‘information’ in question can be modelled in different ways as energy patterns, perceptual stimuli, textual cues, signs, external or internal representations, and the ‘processing’ can be modelled by reference to psychology, neuroscience, philosophy of mind, or combinations of these and further disciplines.

Despite their diversity, however, cognitive theories have certain basic principles in common (cf. Hogan 2003a: 29–31). They require that mental processes be described and explained as accurately and comprehensively as possible, in a logically coherent and empirically testable manner. Moreover, they start from a lower level than other theories such as hermeneutics or psychoanalysis. They try to offer explanatory models also for basic processes of reception, which are already necessary for the emergence of the idea of a character, which can only then become an object of interpretation or emotion.35 Most cognitive theories also assume that a mental architecture with certain resources, possibilities and limits shapes both everyday experience and media reception. In order to explain why humans possess this mental architecture, evolutionary psychology is used by some; however, this is by no means necessary and I will not use it.

Three different basic models of cognitive theories can be distinguished, representing stages of increasing objectification: representationalism, connectivism, and neurobiology (see Hogan 2003a: 30–34; Thagard 2005). In everyday life, one describes one’s own experiences and those of others—here: character reception—intuitively, from a subjective perspective, and in folk psychological terms. On a first level of cognitive theory formation, representationalism, such descriptions are objectified, clarified conceptually and empirically, systematised, and further differentiated. Here the assumption of mental representations plays a central role. By contrast, neurobiology seeks to reconstruct the concrete material correlates of mental processes, in particular the neuronal structures and activation patterns of the brain. Such materialist descriptions of mental processes have the advantage of greater objectivity, but entail the loss of the subjective perspective, detach themselves from ordinary language, require extensive experimentation, and rapidly turn exceedingly complex. Connectivism simplifies and abstracts principles of neuroscience by regarding consciousness, in analogy to the nervous system and the electronic computer, as a network of representational nodes through whose spreading activation (increasing neuronal action potential) information is processed in an associative and parallelly distributed way.

These three basic models do not exclude each other but can be understood as different levels of description of one and the same phenomenal complex. The representationalist approach, however, seems the best-suited for character analysis by far, because it facilitates connections with practical analysis, folk psychology, and theories beyond cognitivism. Some cognitive and other theories (e.g., in film phenomenology) reject the representationalist approach and pursue the idea of a direct perception of both natural and audiovisual environments, for instance, following James Gibson’s work.36 In my view, this approach is unsuitable as a foundation of character theory: if my ontological considerations are correct, then it can neither consistently define what characters are nor explain their different kinds of properties and the ways we talk about them.

The basic notions of representationalism may be summarised as follows:37 whenever items of textual information are perceived and processed, they are run step by step through relevant parts of a bodily and mental system. The images and sounds of a film are perceived by sensory organs and further processed in auditory and visual centres (associated with other centres of sensory perception). The resulting filtered information can directly affect the emotional centres and trigger basal affects. After further, partially parallel, steps of processing and experiencing, the items of information reach the working memory where they are synthesised and given the form of certain mental representations and higher cognitions that are, in turn, accompanied by conscious experiences and more complex emotions. All these steps of processing may simultaneously stimulate various bodily reactions.

The capacities and rhythms of the sensory, working, and long-term memories influence the outcome. The eyes, while scanning the field of vision in saccades at lightning speed, already focus on certain areas. Not all information can be taken in, experienced consciously, and stored; the limited capacity leads to selective attention, including additional control by affects and interests. The consequences have been impressively demonstrated by the famous film experiments on ‘inattentional blindness’ (Simons and Chabris 1999): many of the spectators focusing their attention on the change of the ball in a basketball game do not even notice a person in a gorilla costume intermingling with the players. What is perceived when watching a movie, therefore, not only depends on the availability of certain textual signs, but also on the spectators. Character conceptions and other mental representations arise when the mental and bodily dispositions of viewers interact with textual information. The objective information given in the film (its changing patterns of light and sound) is not received one-to-one, but processed selectively, modified in steps, and supplemented by memory contents. Such processes are fundamentally bidirectional, guided in varying degrees by the textual input (processing bottom-up) or pre-existing mental dispositions (processing top-down).

In the empirical study of literature, the totality of the authors’ and readers’ dispositions has been called the ‘system of preconditions’ (Voraussetzungssystem) of the communication partners (Schmidt 1991: 71–74). It comprises the abilities, knowledge, general motivations, needs, and intentions of producers and recipients, as well as the influences of their sociocultural circumstances. Furthermore, it includes ‘special conditions’, i.e., assumptions about the other communication partners and their dispositions, the knowledge of communicative actions, roles, and expectations, situative physical and mental states (Schmidt 1991: 72). The spectrum of mental dispositions ranges from innate reaction tendencies, such as those concerning startle effects or optical illusions, to culturally specific beliefs and individual concepts of identity. Partial aspects have been dealt with under a variety of different concepts, the most common being categories, mental schemas, framing, knowledge, and memory.38 A schema might involve, for instance, the preconscious expectations on a handshake; one assumes that it will last for two or three seconds and is surprised when it lasts much longer (Smith 1995: 51). All such dispositions focus attention, structure information processing, and direct expectations and processes of making meaning. They permit inferences going beyond the textual basis, which are usually of an informal and subconscious kind. A well-known example is the mental script for a restaurant visit. Entering a restaurant, one expects a particular sequence of events: sitting down, ordering, eating, paying, and leaving. This sequence is presupposed, so it does not have to be shown in detail in a film. Deviations from the script (such as eating without sitting down or paying), however, trigger surprise. Such dispositions influence the perception of characters on all levels: even the cut from one image to the next is conditioned by ‘sensory-motor projections’, implicit expectations on continuity of movement (in editing) whose disappointment, e.g., by jump cuts, will lead to perceptual micro-irritations (Hogan 2007).

Compared with hermeneutics, semiotics, and psychoanalysis, cognitive theories permit a more differentiated and empirically substantiated description of the system of mental dispositions as a hierarchically structured multiplicity.39 In nearly every case, mental dispositions involve affects or could trigger or be activated by them. Some of these cognitive and affective preconditions seem to be universal, e.g., the basic capabilities to recognise certain affective patterns or to empathise. Others, such as knowledge of languages, stereotypes or complex moral emotions, are learnt in sociocultural contexts—also of watching films—and are connected to particular times or cultures. A third group of dispositions stems from individual experiences, for example personal recollections that are evoked by sensory stimuli like particular smells or patterns of movements. A fourth group depends on the situation, for example the specific motives for going to the cinema or the expectations generated by the specific film itself. Within certain limits, however, intersubjective, generalisable statements about the connections between film, cognition, and emotion are possible.

I mention these distinctions here because, contrary to widespread views, they make clear that the reception of media and consequently of characters is not at all restricted to either everyday perception or the decoding of conventional signs, that it is neither the mere reproduction of textual information nor a process of understanding devoid of all emotion. It is, furthermore, neither biologically or culturally determined nor purely subjective. It is rather an experiential process with cognitive, affective, and somatic aspects, which is specified by dispositions on at least four levels: the biological, sociocultural, individual, and the situation- and text-specific levels. In order to talk about commonalities in reception, it is necessary first to clarify what correspondences may underlie these processes at each of these levels. Before dealing with those most relevant to analysing characters, it may suffice to say that there is a very general foundation for the basic understanding and experience of characters that transcends epochs and cultures, but upon which rest innumerable cultural and individual particularities.

A largely universal basic structure is already given with the mental architecture: most humans possess certain kinds of sensory organs, systems of short- and long-term memory, emotional and motor centres in the brain. The breadth of variation of this mental architecture and its capacities is relatively limited among neurotypical and able-bodied adults, but children, neurodivergent, blind, or deaf people, as well as intoxicated individuals, may perceive films in quite different ways. It is the long-term memory, however, that is mostly responsible for fundamental differences among spectators. Its material basis is in the plasticity of neuronal complexes throughout the entire brain. In a functionalist perspective, it comprises two main components: the procedural memory in which automatic skills and motor processes are stored (e.g., riding a bicycle, slicing onions, reacting bodily to certain perceptual stimuli), and the declarative memory that contains knowledge about the world and personal experiences (semantic and episodic memory).

The contents of memory are often modelled by the cognitive sciences (but also in semiotics) in the form of associative conceptual systems or lists of features. Stored items of information are combined to form more complex structures: schemata, prototypes, and exempla (Hogan 2003a: 44–48). Schemata are general structures of knowledge based on the constellations of features of human beings, things, or sequences of experiences (like the script of a restaurant visit mentioned above). They form an open pattern of alternative features arranged according to probabilities of occurrence. When Western people enter a restaurant, they will expect with decreasing probability that they will look for a place themselves, that they will be led to a table by a waiter, that they shall have to wait at the bar, or that they are forced to help out in the kitchen. The fact that spectators also use schemata for particular groups of human beings or categories of fictional characters (waiters, cowboys, femmes fatales) will be dealt with later in greater detail (Chapter 5 and Chapter 6).

Prototypes are, as it were, the more specific default case of a schema: subjectively imagined constellations of typical features of particular kinds of human beings, things, or situations (Hogan 2003a: 45–46). Apart from the standard values of the schema, prototypes contain additional features that are considered to be average or particularly characteristic and that separate the category from others. Since a man is defined, amongst other things, by not being a woman (and vice versa), the prototypical conceptions of men and women emphasise their differences, and thus are oriented toward the concept of a ‘particularly masculine’ man and ‘particularly feminine’ woman, rather than towards, for instance, average cases. Prototypes are thus not far from stereotypes, although they may be linked to personal experiences. A third form of memory content are exempla, representations of exemplary individuals. Thus, if I see a Nazi in a movie, I might, for example, be reminded of Major Strasser from Casablanca.

The schemata, prototypes, and exempla stored in the memory form an important foundation for the understanding and experience of characters. As the examples already suggest, such memory content is not affectively neutral, but connected with affective reactions (emotional memory). The link with affects and emotions is perhaps strongest with regard to episodic recollections: when I recall my own personal love encounters or traumatic experiences of violent events, then the associated emotions will be re-awakened (Hogan 2003a: 155–65). Therefore, medial representations are, in this way, closely connected with personal experiences and feelings. Memories can be activated by the perception of particular features, which in turn may lead to the association of further features, affects, and expectations with what is perceived—often stereotypical ones: in a film noir, the appearance of a lascivious woman with black hair might make viewers expect difficulties for the male protagonist. Memory supplements the information perceived, making reception possible, but it can also often trivialise and automate the process to some extent. Schemata and prototypes may be changed and reflected, but this usually happens only when information contradicts them or makes them conspicuous. Nevertheless, most information processing takes place associatively and metaphorically, not mechanically or by logical reasoning and concentrated rational reflection. Many of the things stored in memory function like metaphors because they are not only activated by their original area of experience but are transferred to other areas as well.40 This affects the perception of human beings and characters in many different ways: their bodies may be considered to be containers of their souls (21 Grams); sad music may be connected with their emotional state; a skeleton may stand for death. The term ‘memory storage’ in itself expresses a metaphorical understanding of memory as a container.

Spectators acquire the schemata, prototypes, and exempla stored in their memory in the course of their socialisation through individual experiences within specific cultural contexts. Their memories and the associated emotions are therefore always to some extent individual and different; however, commonalities also exist. Shared forms of memory may be related to various factors. One area is that of biological, genetically determined bases and mostly universal tendencies, for example in regard to particular capabilities (e.g., empathy and linguistic competence), developmental stages (from childhood to old age), experiences (based on gender, age, size, etc.), interests and affective dispositions (sexuality, altruism, fascination with death and disease). A second group consists in sociocultural factors like cultural spaces (language, nationality); living conditions and group affiliations (milieus, classes, peer groups); social norms and rituals (for emotions, sex/gender behaviours, etc.); trades, professions, and other activities; and institutionalised instances of socialisation (family, school), including mass media. In view of this large spectrum of factors, differences and commonalities between human beings cannot solely be traced back to conflicts between drives and conditioning in early childhood, as older varieties of psychoanalysis seem to suggest. Memory is always formed in the interaction of multiple biological and social factors whose relative influence is still waiting to be explored systematically.

This brief summary of cognitive theories has not yet included their treatment of the reception of media. It presented a general picture of how human beings encounter the world: on the basis of a mental architecture possessing particular capacities and dispositions that are moulded biologically, socially, and individually and that show differences particularly (but not exclusively) in the area of memory. Cognitive and affective information processing (or more simply: text-induced thoughts and affects) starts from this basis and runs through several phases, particularly the formation of mental representations. Many cognitive theories assume that the reception of media is essentially based on the same foundations and mental dispositions as the ordinary perception of non-medial environments (Currie 1999a). They propose that the spectators are active individuals who are looking for meaning by means of ordinary cognitive procedures (Bordwell 1985a: 30–33). ‘Instead of searching for a “language” of film we had better search for ways and means to make films in such a way as to release those activities of “cognising” that lead to understanding’ (Bordwell 1992: 7); and one might add: that also lead to affective experience. In this search, however, it is of importance to pay closer attention to certain crucial differences between media reception and ordinary everyday perception: most importantly, communicative framing, media-specific input, and the activation of specific dispositions.

Recipients are usually aware of being in a communicative situation and perceiving a media text. Such reception is obviously preconditioned by the given media framework or dispositif (cinema, television, video/DVD; e.g., communal viewing; ticket; darkened room in the cinema) and its paratexts (trailers, posters, advertisements).41 This communicative framing and the film itself can activate specific dispositions: the knowledge of media-specific rules and conventions of communication; the feeling of not perceiving present objects and real situations and thus of not being able to interfere; the subliminal awareness of fictionality, of perceiving an invented story; the readiness to accept, therefore, even a non-realistic logic in the narrated world. At the same time, specific contents stored in memory are called up: media-specific knowledge about themes, genres, and conventions of narration, for instance types of characters and standard situations; knowledge about inter-textual and inter-medial references; knowledge about authors, directors, stars, and their images or intentions; and, finally, the assumption of the broader significance of what is shown, i.e., that the show is not just a randomly observed event but a consciously shaped component of a communicative process (see Culpeper 1996: 353). When, and to what extent, such dispositions are activated will depend on the kind of media text and its recipients (as indicated by debates about self-referentiality; Withalm 1999).

A further difference between everyday perception and media reception lies in the kind of input. In the case of media reception, this input basically comes from two different sources: the media text and the context of reception (who hasn’t been annoyed by noisy neighbours in the cinema?). The recipients are able to shift their attention from one of these sources to another; they may, for instance, divert it from the screen to a neighbour. Furthermore, in contrast to the everyday world, media perception does not engage all the senses directly; for instance, film only indirectly involves the senses of smell, taste, temperature, or touch (see Antunes 2016). The most important difference, however, lies in the potential of media to guide the perception process in various ways. By way of that, they are able to generate more comprehensive knowledge about characters than is usually available about persons in the outside world.