4. The Writer Anatole France

© 2022 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0284.20

Félix Brun and Raymond de Borrelli brought very different reworkings of the thirteenth-century masterpiece before audiences of their late nineteenth-century countrymen. The first, with his three prose versions, had one chance to catch the attention of newspaper readers at the national level and two others to spread the word among the loyal coterie of cultivated friends and associates he enjoyed in his Picard hometown and its environs. The second was a known quantity in the French Academy, even if many members of the elite disparaged his poetry despite its blue ribbons.

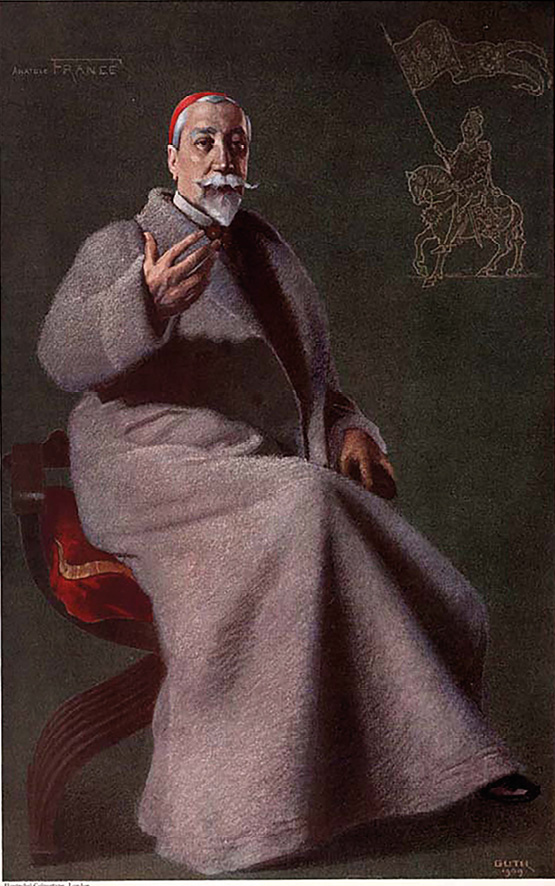

For all their efforts, Brun and Borrelli by themselves would have realized precious little through their revamped forms of “Our Lady’s Tumbler.” Certainly, they would not have achieved a long-lasting niche for the medieval tale in the modern Western world or even merely in their native land. It required another individual, with greater writerly craft and cultural clout, to create the short story that would propel the tale to break out from restricted confines and to become disseminated not merely throughout France but even throughout the world, especially across the Atlantic. This third one who recast the gist of the poem from the Middle Ages plied his pen under the pseudonym of Anatole France.

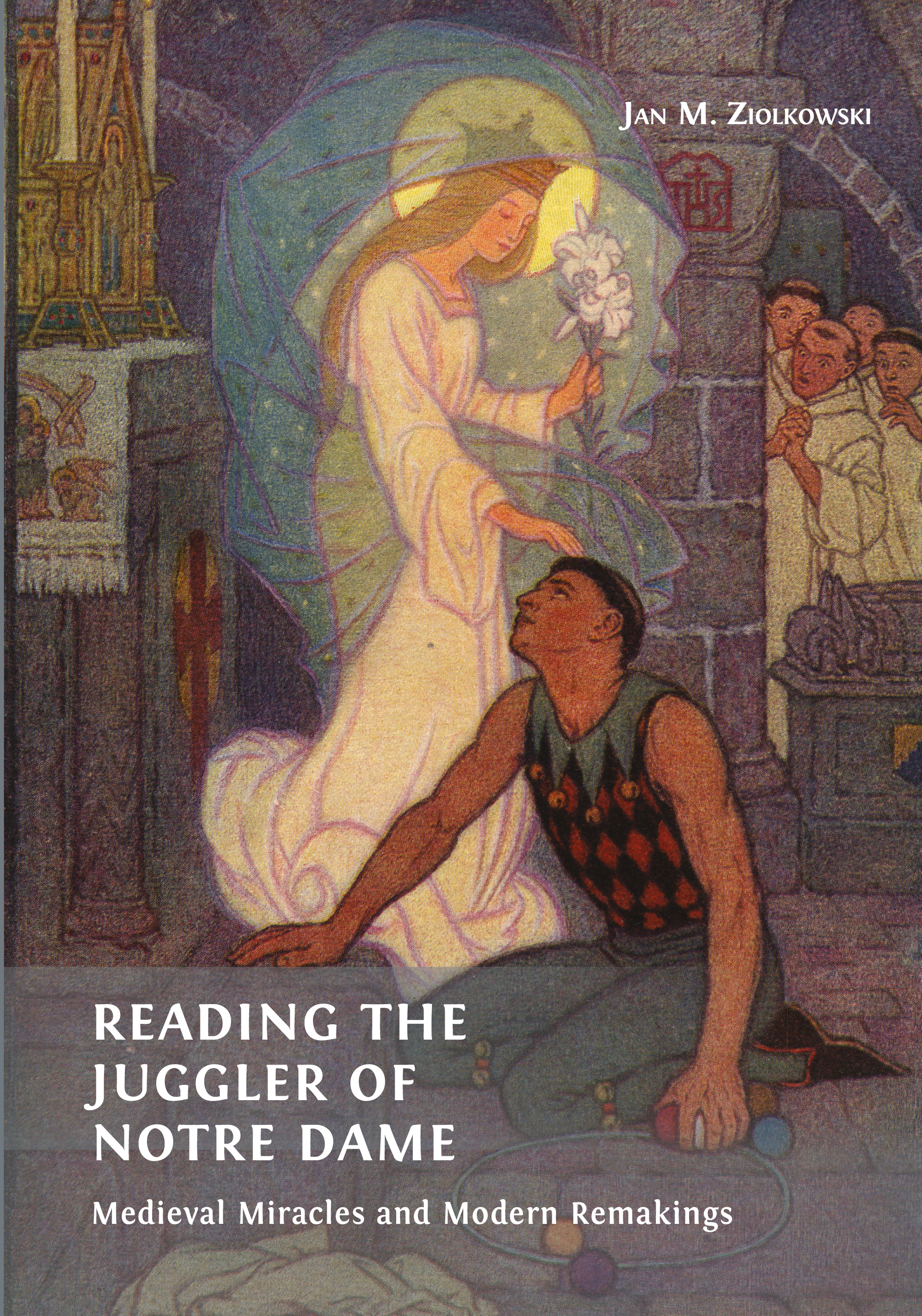

Fig. 27: Anatole France—“The Greatest Living Frenchman.” Illustration by Jean-Baptiste Guth, 1909. Published on the front cover of Vanity Fair Supplement (August 11, 1909). Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anatole_France, Vanity_Fair,_1909-08-11.jpg By assuming this nom de plume, the man who had been christened Jacques-Anatole-François Thibault effectively transformed his nation into his family.

The process of artistic creation often unites many elements. The metaphor of spinning a yarn conveys this multiplicity, evoking as it does the intertwining of many fibers to make a whole. In a few columns published in the popular press, Anatole France, who lived from 1844 to 1924, revealed a central thread in his own textile craft: the intermediary through which he purported to have encountered the contents of the original poem. In evaluating Gaston Paris’s highly influential history of French literature in the Middle Ages, France sketched a romanticized vignette of his initial exposure to the thirteenth-century verse that he owed to the mediation of the illustrious philologist.

France conjures up a picture, possible but implausible, in which one fine day he perused the scholar’s book to the accompaniment of birdsong, while lolling on the grass beneath an oak. Modern literary historians often call this kind of setting, a commonplace of medieval poetry, by the Latin locus amoenus, for “pleasant place.” The belletrist showed his genius in transplanting himself into this very kind of pleasance for his first contact with the recently discovered miracle poem.

Though Gaston Paris himself doubted the capacity of literature from much earlier in the second millennium to inspire the authors of his own day, Anatole France contrived ways to appropriate for modernity aspects of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages as glimpsed through Belle Époque eyes. Among the works of postclassical literature that he reimagined for the readership of his day, the most numerous and important were saints’ lives and miracle tales, especially those involving the Virgin Mary. He took possession of the European past far less through direct study of older literature on his own—even in translation—than through indirect reliance on scholarship. Gaston Paris was an especially distinguished intermediary, with whom the storywriter shared a privileged bond as a fellow member of the French Academy.

But the learned académicien was not the only contemporary who stimulated Anatole France’s fancy as he composed. The writer’s lovely narrative appeared first in 1890, in a daily as a feature for May, which was simultaneously the month of Mary, under the French title corresponding to the English “The Juggler of Notre Dame.” The day after the paper hit the kiosks, an impassioned note arrived whose author accused France of having committed plagiarism. Allegedly, the celebrated man of letters had borrowed without acknowledgment from the letter writer’s own handling of the same story. Though the original communication no longer exists, and though no record of the aggrieved man’s name survives, France’s self-defense has come down to us. In English it reads:

11 May 1890. Sir, I would regret immeasurably a circumstance that does me praise, if your work could suffer from it. But it is obvious that my work is not of a sort to do injury to yours. The idea came to me, in reading the book of Gaston Paris on poetry in the Middle Ages, to tell in my manner the story of the “Jongleur de Notre-Dame.” I even say a word about it in an essay on The Literary Life that has been included in the second series [of that collection]. Being committed this year to furnish Monsieur Arthur Meyer one tale per month, the idea came to me naturally to take up this miracle of the Virgin again for the month of May. I should wish quite keenly, Monsieur, that Monsieur Arthur Meyer would publish your work, which could not have a likeness to mine. As you have surmised, I do not know the text of the original poem and I have created my tale solely on the basis of the six lines of analysis that Monsieur Gaston Paris has provided.

France’s offer to facilitate publication rules out Félix Brun as the disgruntled correspondent, since by this date the archivist had published his tale at a minimum twice and perhaps even three times. No, the injured party had to have been the Vicomte, the proud and thin-skinned Raymond de Borrelli. The poem “The Juggler” of the patriotic poetaster had not yet been printed, and though seemingly he had still not recited it before the French Academy, he could have submitted it already to be considered for the trophy it eventually won. Who knows? Anatole France could have been one of the jurors who read it in the competition, or he could have spoken about the piece with someone else who served on the jury. Nor are formal recitation and submission the exclusive channels through which Borrelli’s idea could have seeped to France.

The author of the short story brushed aside the reproach brought against him. He admitted freely to having gotten his idea from another, giving credit entirely to the foremost French medievalist of his day. In fact, in the daily newspaper he dedicated the pages not merely “To Gaston Paris,” as he put the matter succinctly in later volumes of his short stories, but with all the bibliographic trimmings of a full citation:

What you are going to read has been drawn from a miracle of the thirteenth century. (See Gaston Paris, La Littérature française au Moyen Âge, 2nd edition (Paris, 1890), p. 208.)

We can take France at his word about the original. Nothing suggests that he ever so much as laid eyes upon the edition by Wendelin (or Wilhelm) Foerster, which in 1890 remained the single means of printed access to the thirteenth-century poem for anyone not equipped to consult one of the few codices. The French fiction writer, the son of a book-loving bookdealer, was himself a bibliophile. Being a bookworm, he did his share of poking around in scholarly tomes, both hot off the presses and antiquarian. In fact, in “The Juggler of Notre Dame” he refers with fond exactitude to an illustration reproduced as the frontispiece to the mid-nineteenth-century edition of Gautier de Coinci’s Miracles of Our Lady. For all that, he did not fuss with the mustiness of learned journals or medieval manuscripts. He was far from being an autodidact historian or amateur philologist, with the requisite training for parsing the alien forms of Old French language. Instead, he was a belletrist living in a century preoccupied with a millennium or so of national history, who observed with both wryness and wonderment as experts from the world of learning engaged with the past. From this remove, he picked up tidbits with which he stocked his imagination.

The closer France drew to anything smacking of pedantry, the more he gave vent to his characteristic irony. His reputation had been launched by a first novel entitled The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard, published in 1881. In it he treated with his hallmark dry wit the main figure, who was a Chartist—a graduate of the École Nationale des Chartes or, translating verbatim, National School of Charters. Recall that Félix Brun had differentiated his own research on medieval topics from the unimaginative technicality of these very scholars.

But let us venture back to the exchange with Borrelli. France pointed out correctly that in his review of the literary history he had summed up the medieval poem as described by Paris. Sure enough, the short-story writer had written:

Finally, here is a still more naïve miracle, that of “Our Lady’s Tumbler.” There was a poor jongleur who, after having performed physical feats in public places to earn his living, dreamt of eternity and had himself accepted into a monastery. There he saw monks, good clerics that they were, honor the Virgin by learned prayers. But he was not a cleric and did not know how to ape them. Finally, he had the notion to shut himself in the chapel and to perform, alone, in secret, before the Blessed Virgin, the somersaults that had won him the most applause in the days when he was a jongleur. Some monks, disturbed by his lengthy absences, set themselves to spying on him and caught him in his pious exercises. They saw the Mother of God come herself, after each somersault, to dab the forehead of her tumbler.

Not a sentence of France’s prose follows its thirteenth-century forebear exactly. How could his précis have been more faithful to this ancestor, when he viewed it solely as refracted through Gaston Paris’s recapitulation?

Despite his candor about what he appropriated from the summary of the Old French, France may have been more disingenuous about not owing any debt to Borrelli. The poet probably gave France the idea of casting the leading man not as a jack-of-all-trades jongleur but as just a juggler. Sure, both the English terms juggler and jongleur derive ultimately from the Latin ioculator, and both meanings of the French jongleur do too. But Borrelli innovated by transitioning the general gymnast of the medieval poem into a specialized entertainer: he made the dancing acrobat into a juggler who concentrates on the continuous tossing and catching of multiple objects.

Even less likely to be mere coincidence, the short story has at both beginning and end the colorful distinction that the juggler juggles with copper balls. This motif, not attested in the original from more than 650 years earlier, did not appear in the prose of either Gaston Paris or Félix Brun, but it was an eye-catching element in the prizewinning verse by Raymond de Borrelli. So too was the fine point that the performer carried a carpet that he would unfurl for use in his show. Though the two details may reflect the realities of juggling in the late nineteenth century, put together as circumstantial evidence they suggest strongly that the storywriter was indebted to the poet more than he was willing to concede.

But enough said about sources, when what matters is what France made of them. To him, the medieval era may not have been paradise lost but it was at least simplicity lost. In reaching this perspective, he could have had personal circumstances in mind. His mother died in 1886, his father in 1890. In 1888 he began a stormy affair with Madame Arman de Caillavet, née Léontine Lippmann, that contributed to his separation from his wife in 1892 and his divorce in 1893. To say that he was rethinking childhood beliefs and values or that he was endeavoring to be his own man would state the case too mildly.

If the Middle Ages as France supposed or at least desired them to have been constituted a parallel universe to the developments in his own life, he implied that the period contrasted even more emphatically to the tenor of the whole fin de siècle. He took as a given that in contradistinction to his contemporaries, medieval folk still clung staunchly to a simple faith in God and in the capacity of the Virgin to make herself felt on earth through apparitions and through intercession in heaven.

The simplicity belonged part and parcel to the childlike nature of people in the Middle Ages. Wendelin Foerster mentioned this childishness in the article printed by Romania in 1873. Anatole France, in concluding his assessment of Paris’s literary history, exhorted readers similarly not to take their medieval predecessors to task for their shortcomings. They were to be held no more accountable than are children. In effect, they were the Old World’s own noble savages, resembling more than a little the natives of continents under the colonialist rule of Europe’s empires: cultural and chronological primitivism have a close kinship. Supposedly primitive, medieval folk were free from the artificiality and decadence of the all too urbanized society in which their descendants lived.

France stayed true to this outlook in “The Juggler of Notre Dame.” The closing message, even moral, of the story fuses two beatitudes from the Gospel of Matthew, “Blessed are the simple, for they will see God.” At the same time, the author made clear that along with loss came a superiority: his own times possessed a sophistication that lofted his contemporaries and him beyond what, in referring to his medieval forebears, he called “the naïveté of their imagination.” This naïve quality enabled their forerunners of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries to maintain their certainty about a good deal that, more than a half millennium later, no longer seemed believable but instead charmingly ingenuous and childlike.

So much for chronological matters. What about geography? “The Juggler of Notre Dame” remarks nowhere explicitly on the capital city of Paris, but Anatole France could not have conceived and composed the short story outside the metropolis. In institutions such as the French Academy, the elite of the arts hobnobbed with the elect of the humanities. Though the archivist Brun may have had no aspiration to penetrate this inner circle, the Vicomte de Borrelli surely did. Yet despite his military medals, aristocratic title, and poetic laurels, he gained admittance without ever being embraced. Instead, he was kept on the outskirts and subjected to snickers by up-and-coming writers whose names and fames remain alive even today.

In the meantime, France’s star rose for its half century or so of prominence in the firmament before fading from sight. In 1892, forty-eight years of age, he reprinted the tale in a collection with a French title that could be put into English as The Little Box of Mother of Pearl. As the metaphor conveys, he envisaged the book to be a container for literary bric-à-brac—a case inlaid with nacre that holds smalls objects, such as gems. The jewels housed within its two covers are seventeen short stories, among them four saint’s legends and two loosely hagiographic ones, counting “The Juggler of Notre Dame.” Added together, they certified the Frenchman to be the worthy successor to his countryman Guy de Maupassant as the king of short story, a genre which was at its apogee when they wrote.

The tale of the jongleur lent itself well to the delicate cultural politics of France during the Third Republic. The populace was polarized over few issues more vehemently than over Church-State relations. At one extreme, the anticlerical mounted the ramparts; at the other, the reactionary advocates of Catholicism and royalism dug in. The irony of the short-story writer doubled as tact: his narrative of the jongleur could be parsed by either group as supporting its causes.

Anatole France called his leading man Barnaby. His story, despite its brevity, teems with names, which render less stereotypical the collectivity of monks. The individualization, absent from the medieval poem, marks the juggler as an artist, but as one who feels inadequate in comparison and competition with the monastic specialists in the fine arts.

For more than a half century, “The Juggler of Notre Dame” held sway as a classic. Anatole France reigned supreme in France for his short fiction and novels. The canonicity of his story may have been even more pronounced in the English-speaking world and especially in America than in his homeland. In the original French, it lent itself to language instruction in schools and colleges. For those contexts it was incorporated into one anthology and reader after another. In translation, it was deemed suitable for reading aloud, dancing, singing, and theatrical presentation.

But the very success of “The Juggler of Notre Dame” set the stage for the exhaustion and overexposure that were doomed to set in. Teachers eventually recoiled from the ubiquity of the tale, and students may have done the same: familiarity breeds contempt. Its author took a nosedive in popularity: the existentialism of more recent French intellectuals such as Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre became chic; the irony of Anatole France, old hat. Then, as the French language lost ground within the United States educational system, so naturally the little narrative slipped even further from the universal recognition that it had once commanded. Along the way, the religious content—despite its author’s trademark wit—shifted from being an advantage to effectively disqualifying it from use in many teaching contexts. A story that had taken the world by storm at the turn of the century and charmed multitudes for decades after became forgotten.

“The Juggler of Notre Dame”

I

In the time of King Louis, there lived in France a poor juggler, a native of Compiègne, named Barnaby, who would go from town to town, performing tricks of strength and skill.

On market days, he would spread out in the public square an old carpet, all worn-out, and after attracting children and passersby with some amusing quips that he had picked up from a very old juggler, and that he never changed at all, he would strike unnatural poses and balance a tin plate on his nose. At first, the crowd observed him with indifference.

But when, standing on his hands with his head down, he would throw into the air and catch with his feet six copper balls that glittered in the sunlight, or when, tilting backward until the nape of his neck touched his heels, he assumed the shape of a perfect wheel and in that posture juggled with twelve knives, a murmur of marvelment arose from the spectators, and pieces of change would rain on his carpet.

For all that, Barnaby of Compiègne, like most of those who make a living by their wits, had a very hard time doing so.

Earning his bread by the sweat of his brow, he bore more than his share of the troubles linked to the sin of Adam, our father.

What is more, he could not work as much as he wished. For showing his fine know-how, he needed, as do trees for producing flowers and fruits, the warmth of the sun and the light of day. In winter, he was no more than a tree stripped of its leaves and all but dead. The frozen earth was hard for the juggler. Like the cicada of which Marie de France tells, he suffered cold and hunger in the winter months. But since he had a simple heart, he endured his ills patiently.

He had never thought about the origin of wealth or the inequality of human conditions. He expected firmly that if this world is evil, the next could not fail to be good, and this hope supported him. He did not imitate the mountebanks, thieves, and miscreants who sold their souls to the devil; he never took the name of God in vain; he lived honestly, and though he did not have a wife, he did not covet his neighbor’s, for woman is the enemy of strong men, as is evident from the story of Samson, which is recounted in the Scriptures.

In truth, he did not have a mind inclined to carnal desires, and it was harder for him to renounce drinking than women. For, without neglecting sobriety, he liked to drink when the weather was warm. He was a good man, God-fearing, and very devoted to the Holy Virgin.

When he went into a church, he never neglected to kneel before the image of the Mother of God and to address to her this prayer:

“Madam, take care of my life until it please God that I die, and when I am dead, let me have the joys of Paradise.”

II

Now, one evening, after a day of rain, as he went along, sad and stooped, carrying under his arm his juggling balls and knives hidden in his old carpet, and looking for a barn where he might go to bed without having eaten, he saw on the road a monk who was going the same way, and greeted him courteously. As they were both walking in step, they began to exchange pleasantries.

“Friend,” said the monk, “how does it happen that you are dressed all in green? Would it be to play the part of the fool in some mystery play?”

“Not at all, father,” replied Barnaby. “Such as you see me, I am named Barnaby, and I am a juggler by trade. It would be the finest trade in the world if a person in it could eat every day.”

“Barnaby, friend,” continued the monk, “take care what you say. There is no finer trade than the monastic one. The person in it performs in praise of God, the Virgin, and the saints; and the life of a monk is a never-ending hymn to the Lord.”

Barnaby replied: “Father, I confess that I spoke like an ignorant man. Your trade cannot be compared to mine, and though there may be some merit in dancing while balancing on the tip of my nose a coin on top of a stick, the merit does not come close to yours. I would not mind singing the office every day like you, my father, especially the Office of the Very Holy Virgin, to whom I have pledged a special devotion. I would gladly give up the craft for which I am known from Soissons to Beauvais, in more than six hundred towns and villages, to pursue the monastic life.”

The monk was moved by the simplicity of the juggler, and, as he was not lacking in insight, he recognized in Barnaby one of those men of good will of whom our Lord said, “Let peace be with them on earth.” That is why he replied:

“Barnaby, friend, come with me and I will have you enter the abbey of which I am the prior. He who led Mary of Egypt into the desert put me on your path to lead you down the road to salvation.”

It is in this way that Barnaby became a monk. In the abbey where he was received, the brethren celebrated in eager competition the cult of the Holy Virgin, and to serve her, each one used all the knowledge and skill given to him by God.

The prior, for his part, put together books which, according to the rules of scholasticism, treated of the virtues of the Mother of God. With an expert hand, Brother Maurice copied these treatises on leaves of vellum. On them, Brother Alexander painted delicate miniatures. In them, you could see the Queen of Heaven, seated on the throne of Solomon, at the foot of which four lions keep watch; around her haloed head fluttered seven doves, which are the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit: gifts of fear, piety, knowledge, fortitude, counsel, understanding, and wisdom. As companions, she had six golden-haired virgins: Humility, Prudence, Restraint, Respect, Virginity, and Obedience. At her feet, two little figures, naked and all white, held themselves in a suppliant pose. They were souls who entreated for their salvation and, surely not in vain, for her all-powerful intercession.

On another page, Brother Alexander depicted Eve opposite Mary, so that one might see at the same time sin and redemption, the fallen woman and the Virgin elevated. In this book one could also marvel at the Well of Living Waters, Fountain, Lily, Moon, Sun, and Garden Enclosed (which is described in the Canticle), the Gate of Heaven, and the City of God, and on it there were images of the Virgin.

Brother Marbod was by the same token one of the most loving children of Mary. Unceasingly, he carved images of stone, so that his beard, eyebrows, and hair were white with dust and his eyes were perpetually swollen and teary; but he was full of strength and joy in his advanced years, and evidently the Queen of Paradise watched over the old age of her child. Marbod represented her on a pulpit, seated, her forehead encircled by a halo with an orb of pearls. And he took care that the folds of the robe covered the feet of the woman of whom the prophet said, “My beloved is like a garden enclosed.” Sometimes he also depicted her with the features of a child full of grace, and she seemed to say, “Lord, you are my Lord! I have spoken from the womb of my mother: You are my God” (Psalms 21:11).

There were also in the abbey poets who composed prose and hymns in Latin in honor of the blessed Virgin Mary, and there was even a Picard who put the Miracles of Our Lady into the vulgar tongue and into rhymed verses.

III

Seeing so great a competition in praises and such a handsome harvest of works, Barnaby bemoaned his ignorance and simplicity. “Alas!” he sighed, as he walked by himself in the little shadeless garden of the abbey, “I am so unhappy at not being able, like my brothers, to give worthy praise to the Holy Mother of God, to whom I have pledged all the tender feeling in my heart. Alas, alas, I am a coarse and artless man, and to serve you, madam Virgin, I have no edifying sermons, no treatises set out in order according to the rules, no fine paintings, no precisely carved statues, and no verses counted off by feet and marching in time! I have nothing, alas!” He groaned in this way and gave himself over to sorrow.

One evening, as the monks took a break by conversing, he heard one of them tell the story of a monk who could not recite anything but the Hail Mary. This monk was scorned for his ignorance, but when he died, there issued from his mouth five roses, in honor of the five letters in the name Maria, and in this way his holiness was made evident.

In listening to this account, Barnaby marveled once more at the kindness of the Virgin, but he was not consoled by the example of that blessed death, for his heart was full of fervor and he wished to serve the glory of his lady, who is in heaven.

He sought, without being able to find it, a way to do this, and each day he was more distressed, until one morning, having awakened joyfully, he ran to the chapel and remained alone there for more than an hour. He returned there again after dinner. And, starting from that moment, he would go every day into the chapel at the time when it was empty, and there he spent a good part of the time that the other monks dedicated to the liberal arts and mechanical arts. He was no longer sad and he groaned no more.

Such peculiar behavior awakened the curiosity of the monks. People in the community asked themselves why brother Barnaby went off by himself so often. The prior, whose duty it is to be unaware of nothing in the behavior of his monks, decided to watch Barnaby during his times on his own. One day then, when Barnaby had shut himself up in the chapel according to his custom, Dom Prior, accompanied by two elders from the abbey, came to watch, through the chinks of the door, what was going on within.

They saw Barnaby. who was before the altar of the Holy Virgin, his head downward, his feet in the air, juggling six copper balls and twelve knives. In honor of the Holy Mother of God he was performing the tricks that had formerly brought him the most praise. Not understanding that this simple man was thus putting his talent and knowledge at the service of the Holy Virgin, the two elders cried out at the sacrilege.

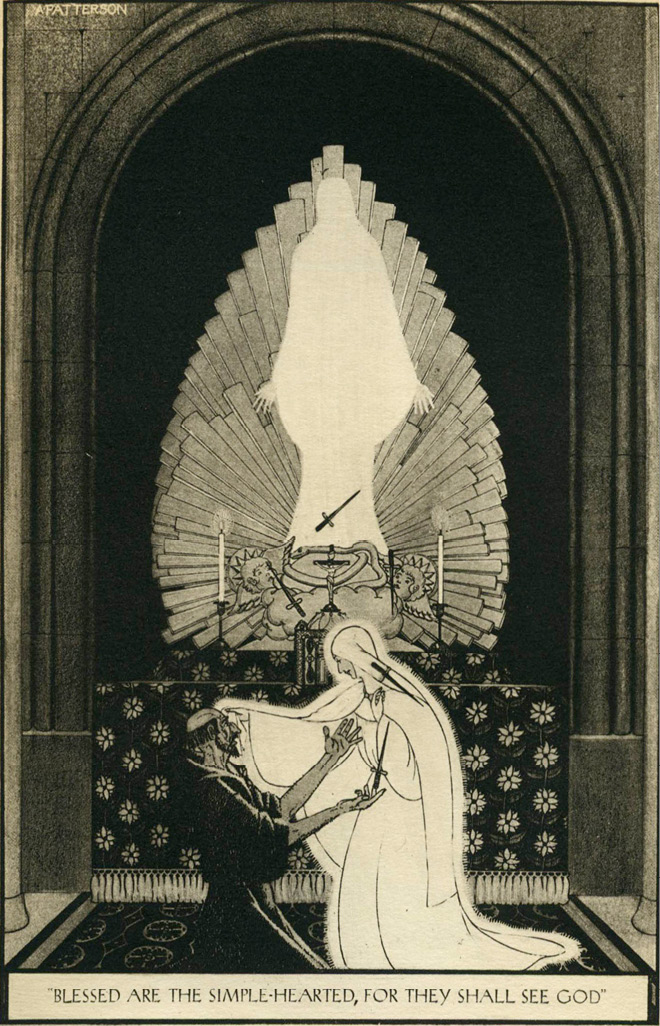

The prior knew that Barnaby had a blameless soul; but he believed that the man had sunk into madness. All three were preparing to remove Barnaby forcibly from the chapel when they saw the Holy Virgin descend the steps of the altar to come wipe with a fold of her blue mantle the sweat that was dripping down from the forehead of her juggler.

Then the prior, prostrating himself with his face against the flagstone, recited these words: “Blessed are the simple, for they will see God.”

Fig. 28: “Blessed are the simple-hearted, for they shall see God.” The Virgin descends to wipe the brow of the juggler. Illustration by L. A. Patterson, 1927. Published in Anatole France, Golden Tales of Anatole France (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1927), facing p. 112.

“Amen,” replied the elders, kissing the ground.