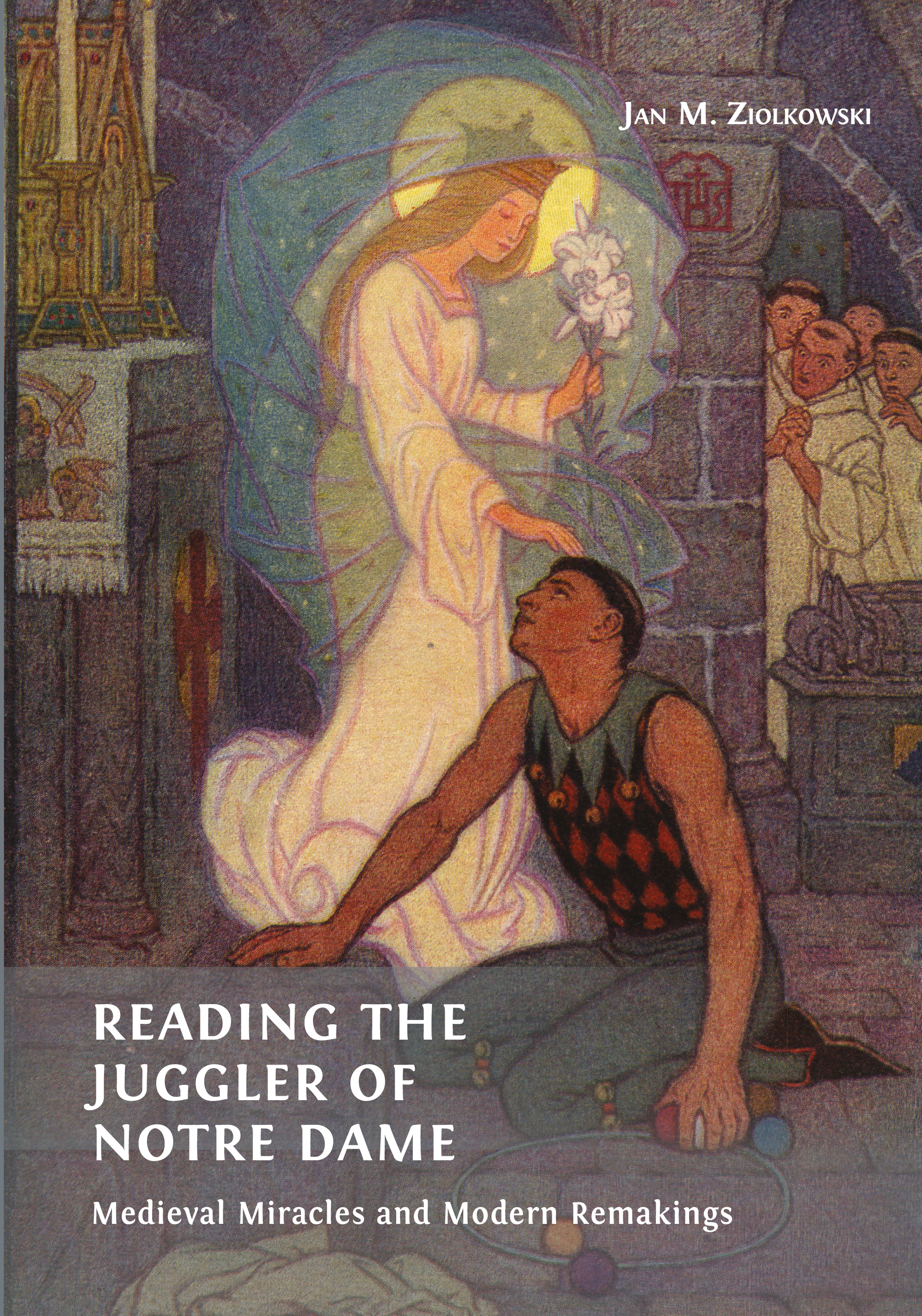

5. The Composer Jules Massenet

© 2022 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0284.21

Jules-Émile-Frédéric Massenet, despite being consigned nowadays to relative oblivion, scored greater commercial success during his lifetime than any of the many other French composers roughly contemporary who command greater fame today, such as—to name only four—Camille Saint-Saëns, Gabriel Fauré, Claude Debussy, and Erik Satie.

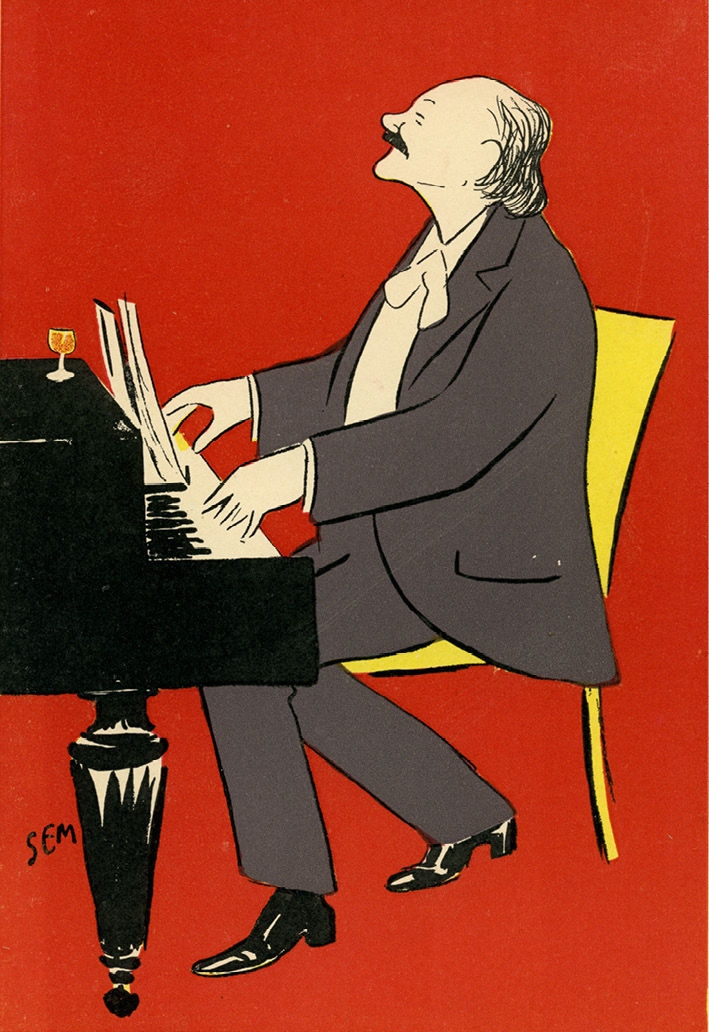

Fig. 29: Caricature of Jules Massenet. Illustration by Sem, before 1909. Published in Sem, Célébrités contemporaines et la Bénédictine (Paris: Devambez, 1909).

Massenet set a goodly share of his operas in the Middle Ages: Le Cid, playing out against the backdrop of Christian-Muslim clashes in Spain, premiered in 1885; Esclarmonde, focused upon a Byzantine empress (and sorceress) who falls in love with a French knight, in 1889; and Grisélidis, the story of a long-suffering and unfairly mistreated wife, in 1901. His operatic outpouring of medievalism reached a crescendo in 1902 with Le Jongleur de Notre Dame or, put into English, The Jongleur of Notre Dame.

Like many others of his day, the young musician was dazzled by his first exposure to Richard Wagner’s Parsifal. Later, when the Frenchman conceived of his own musical drama based on a medieval romance, Esclarmonde, its purportedly Germanizing features caused him to be slurred as Mademoiselle Wagner. Though the German composer influenced him, the taunt of “Mrs. Wagner” was not entirely fair. Neither Massenet’s Middle Ages nor his music exhibited consistent signs of Wagnerism.

Whatever the case with this or that among his earlier operas, the setting and music of The Jongleur of Notre Dame are through-and-through French, from the town square of the opening scene on. In his ghost-written autobiography, Massenet concocted a fanciful anecdote to explain how he came to compose this sensation. The centerpiece of the fantasy takes place on a train ride, as the composer tears open a parcel supposedly sent to him anonymously by mail and thumbs through the manuscript of a libretto that seizes his imagination.

Whatever the realities of the collaboration, Maurice Léna, a professor, music critic, and librettist, evidences in the text a profound, even erudite acquaintance with Latin liturgy, Medieval Latin poetry, Old French poetry, and modern French poetry.

Fig. 30: Maurice Léna. Photograph, date and photographer unknown. Published in Louis Schneider, Massenet: L’homme—le musicien. Illustrations et documents inédits (Paris: L. Carteret, 1908), 247.

What he does not betray is any inclination to acknowledge his principal sources, perhaps partly because no one would have needed telling that to some extent he was indebted to Anatole France—but for a story that originated in the Middle Ages. Decades later, the deeply learned Léna reveals his awareness of the edition by Wendelin Foerster, the passing mentions of the centuries-old original by Gaston Paris, the poem by Raymond de Borrelli, and the prose by Anatole France. The question is whether he possessed all these minutiae before putting together the libretto, or whether he picked up some or most of his erudition about the literary tradition after the fact.

The only certainty is that the librettist had to have been aware of France’s famous piece. Yet Léna’s remaking has little in common with its closest predecessor. Though the short story has three sections, each numbered with a Roman numeral, and the opera has three acts, even so the progression of the narrative differs greatly. Yes, in both France and the opera, the principal character feels inadequate as an artist when judged against the monks, with their mastery of more prestigious crafts. But the two characters, the exotic-sounding, well-traveled Barnabé in the prose and the homespun, almost peasant-like Jean in the libretto, are not at all the same. The second is not a top-flight juggler but a humbler and even sometimes inept jack-of-all-trades in the entertainment industry—a jongleur. This adjustment is essential to the drama, since it enables Léna more scope for the performance of songs and display of verbal art.

To turn to religion, Jean appears far more sacrilegious than Barnabé, but the old adage seems to apply: the greater the sinner, the greater the saint. The sinfulness makes itself manifest early, since Jean joins the monastery only under pressure and with reluctance. As events proceed, he may not be a martyr, but he is miserably mistreated. The hostility toward Jean in the opera, particularly from the prior, is far more intense than toward Barnabé in the short story. The antagonism is counterbalanced only by the jovial Boniface, whose affability distracts the audience from recognizing what his gourmandise reveals about the hypocrisy of the monks’ lifestyle. By the end, Léna’s protagonist prevails and is proven to be truly saintly, his piety certified within the monastery.

The endings of France’s short story and of Léna’s libretto stand apart. In the opera stagecraft comes into play, with the glow of artificial lighting, angelic voices off stage, the special effect of a halo, the melodrama of fainting, the miracle of the jongleur’s suddenly understanding Latin, the ascent of Mary and angels, and the death of Jean himself, who becomes almost in his own right a deus ex machina. Simplicity is rewarded with very showy sanctity: the composer and librettist were absolutely right to subtitle the poem as a “Miracle in Three Acts.”

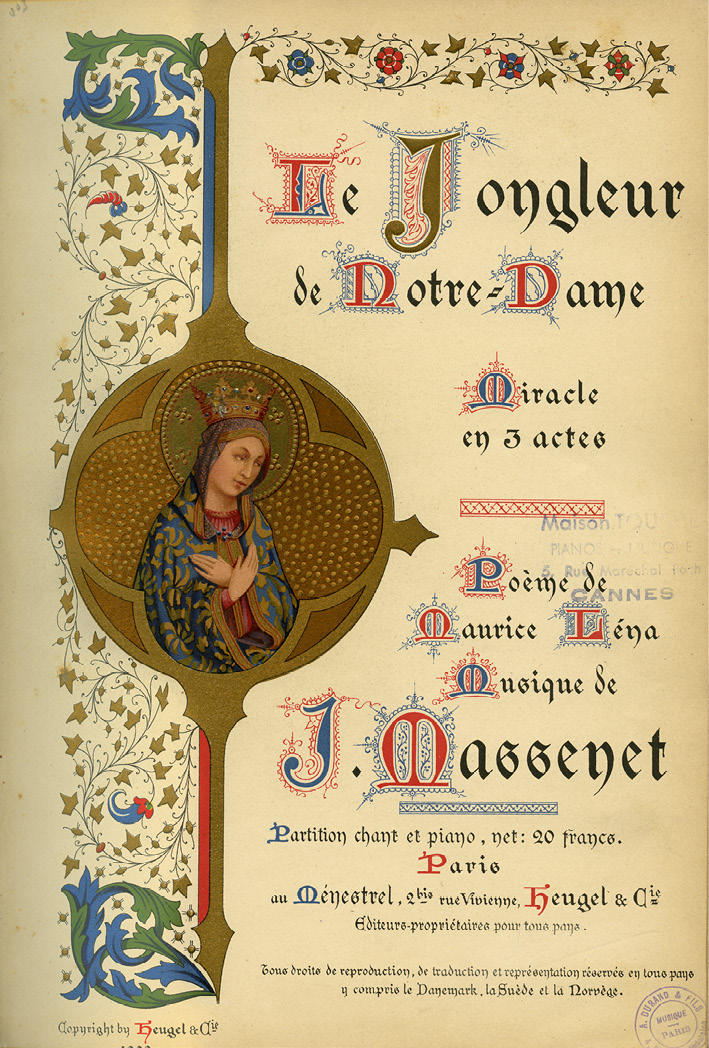

Fig. 31: Title page of piano-vocal score for Maurice Léna and Jules Massenet, Le jongleur de Notre-Dame: Miracle en trois actes (Paris: Heugel, 1906).

The text of the opera, wherever we choose to pin down its wellheads of inspiration, brought out the best in Massenet. In general, the musician attained more favor from audiences of his own day than from critics—and from posterity. But this topic encouraged him to display his talents and range as he did rarely elsewhere. Just as Léna endeavored to immerse his listeners in the literature, liturgy, and legends of the Middle Ages, so too the composer reveled in plumbing the potentials of Church music as well as those of what were thought in his day to be medieval melodies and folk songs.

One circumstance that affected very literally the tenor of the music is the all-male cast of the opera as Massenet originally framed it. In allocating no parts for sopranos or altos on stage, he was in a sense merely owning up to the single-sex realities of medieval monasteries. At the same time, he had reasons relating to his reputation, far beyond verisimilitude, that induced him to conceive of music without any roles that required or even permitted to sing on stage a member of what was then styled “the fair sex” and would become in due course “the second sex.” Over much of his career, the musician was faulted, even ridiculed, for being a woman’s composer. In the gender politics of his day, he allegedly wrote feminine music, found his muse only when creating his operas for divas he adored or lusted after, and attained no success except with musical dramas, verging on soap operas, that relied on female heroines and that drew audiences predominantly of ladies. The Jongleur of Notre Dame is his only opera in which the leading soloist is not a soprano.

If Massenet was intent on proving a point about his masculinity, he trod more carefully in portraying religion and the Church. Both the words and the notes of the opera dance a delicate dance so as to appeal to the two extremes within the riven cultural politics of France in his period. The result could be construed as validating the piety valued by conservative Catholics. Seen from this perspective, the opera looks fondly at the humble faith of a medieval minstrel. Simultaneously, it could be interpreted by secularists as poking fun at the foibles of clerics and treating with irony—gentle, but irony all the same—the credulousness of the uneducated faithful.

The musical drama benefited from a couple of circumstances that kept it in the limelight longer than might otherwise have been the case. At that time the Prince of Monaco had his sights set on making his principality a serious competitor with Paris in operatic productions. To that end, Albert I intervened personally to cajole Massenet into allowing Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame to debut in Monte Carlo, on February 18, 1902. As a result, the slightly belated opening in the capital of France, on May 10, 1904, gave the composition a lift when its novelty might otherwise have begun to sag. But the most emphatic boost came from a Scottish-American diva. Mary Garden, who had taken Paris by storm, prevailed upon Massenet to rewrite the title role from calling for a tenor so that she might sing it en travesti—as a woman in a man’s clothing.

Fig. 32: Mary Garden as Jean the juggler in Massenet’s Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame. Photograph by Matzene Studio, 1909. Published in Henry C. Lahee, The Grand Opera Singers of To-day (Boston: L. C. Page, 1912), frontispiece.

She premiered it with this innovation in the Manhattan Opera House of New York, on November 27, 1908, during the phase when the impresario Oscar Hammerstein I was competing fiercely with the Metropolitan Opera.

Both Hammerstein and Garden were adroit at snagging headlines. The Jongleur of Notre Dame had the distinctive feature of a female lead, which was taken patriotically to be an American innovation, made contrary to the vehement wishes of the composer that “the monk’s habit … [n]ever be disguised in a petticoat.” Whatever the case may be, the work became widely known throughout the United States until the golden age of this art form drew to a close. The end coincided with the curtain fall of Mary Garden’s career in 1930. By that point Massenet’s opera was well positioned for making the transition to vaudeville and radio, as well as for supporting the use of Anatole France’s short story in schools and universities, especially in the French-language curriculum.

The following translation is not intended to be singable, but rather to help English-speakers piece together what the French libretto from the Belle Époque means. Nowadays such an understanding requires decoding many references to Catholic religion and medieval literature that have become obscure in the more than a century that has intervened between its composition and our encounter with it today.

The Jongleur of Notre Dame:

Miracle in Three Acts

Libretto by Maurice Léna

Jean, the Jongleur

Boniface, the Monastery Cook

The Prior

A Poet Monk

A Painter Monk

A Musician Monk

A Sculptor Monk

The Virgin

Two Angels

A Crier Monk

A Heckler

A Drunk

A Knight

A Voice

Angelic Voices, Monks, Knights, Clerics, Townsfolk, Peasants, Vendors, Beggars

|

ACT 1 |

|

|

The town square of Cluny in the fourteenth century. At the center of the square, the traditional elm and under it a bench. We see the façade of the abbey with a statue of the Virgin over the door. It is the first day of the month of Mary, and a market day. Girls and boys dance the shepherd step. |

|

|

SCENE 1 |

|

|

TOWNSPEOPLE, KNIGHTS, CLERICS, PEASANTS, and BEGGARS come and go; VENDORS are at their places. |

|

|

THE CROWD |

|

|

For Our Lady of Heaven |

|

|

dance the shepherd step, |

|

|

Here is charming May, |

|

|

dance the shepherd step |

|

|

and for young prince Jesus |

|

|

take another turn. |

|

|

VENDORS |

|

|

Leeks, turnips, prunes from Tours! |

|

|

Fresh strawberries! |

|

|

Cream cheese! White cabbage! |

|

|

Green sauce, buy the tasty green sauce! |

|

|

A CRIER-MONK |

|

|

Indulgences are available at the high altar! |

|

|

SCENE 2 |

|

|

THE SAME PEOPLE |

|

|

In the distance is heard the melody of a vielle getting closer |

|

|

VARIOUS VOICES |

|

|

Quiet! Do you hear? It’s the sound of a vielle. |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

A jongleur, a jongleur! |

|

|

VARIOUS VOICES |

|

|

The lively refrain hops |

|

|

like a grasshopper. He’s coming! A jongleur! |

|

|

Praise be, it’s a jongleur! |

|

|

He will sing us a new song, |

|

|

do us a new stunt, |

|

|

pull his newest face. |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

He’s here! Make way, make way! |

|

|

SCENE 3 |

|

|

THE SAME PEOPLE, JEAN. |

|

|

JEAN enters playing the vielle; stops |

|

|

Make way for the Jongleur King! |

|

|

He is scrawny and gaunt-faced, with well-worn clothing. |

|

|

General disappointment, murmuring. |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

The king is not very handsome, |

|

|

A king with a piteous look. |

|

|

HECKLER |

|

|

His Majesty, King Starvation. |

|

|

A few laughs. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Attention! Come forward ... Step back ... Attention! |

|

|

Listen all, knights and churls, |

|

|

Young and old, beasts and men, |

|

|

Ladies with a sweet smile, |

|

|

Cripples, hunchbacks, drunkards, thieves, |

|

|

Listen to Jean, Jongleur King! |

|

|

KNIGHTS and PEASANTS singing; girls and boys dancing, around the jongleur, an ironic round. |

|

|

Noble king, choose your queen, |

|

|

Choose your queen, handsome king, |

|

|

Lanturli lon la ... |

|

|

JEAN, interrupting the round |

|

|

Attention! |

|

|

But first, my kind friends, |

|

|

a little small change in my begging bowl. |

|

|

To someone who gives |

|

|

May Jesus repay you for it, sir. |

|

|

Sadly, looking at his bowl |

|

|

An old coin, worth nothing. |

|

|

Resuming his patter |

|

|

Attention! |

|

|

Would you like tricks of jugglery, |

|

|

truly of magic? |

|

|

Never have you seen on earth |

|

|

one more skilled at juggling the stick, |

|

|

bowls, or balls. |

|

|

Scornful laughs |

|

|

I can pull eggs out of a hat! |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

It’s childish ... an old trick ... Go away and pull out chickens! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

I know the hoop dance! |

|

|

[He clumsily sketches a dance step.] |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

What nimble grace! |

|

|

The boys and girls make the jongleur dance with them. |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Choose your queen, handsome king. |

|

|

Lanturli lon la. |

|

|

JEAN, after breaking free |

|

|

Peace, you fools! |

|

|

Continuing his patter: |

|

|

My lords, I’ll sing a lovely salut d’amour. |

|

|

ONE GROUP OF VENDORS |

|

|

Leeks, turnips! |

|

|

Laughter. |

|

|

ANOTHER GROUP |

|

|

Prunes from Tours! |

|

|

JEAN, who begins to lose hope |

|

|

Well then! A battle song, |

|

|

olifant, drum, and clarion, |

|

|

neighs under the spur, |

|

|

cut and thrust! |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

No, no. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

I know Roland. |

|

|

THE TWO GROUPS OF VENDORS |

|

|

Cream cheese! White cabbage! |

|

|

Laughter. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

I know Bertha of the Big Feet. |

|

|

SEVERAL VOICES |

|

|

No, no, too old a story. |

|

|

The round resumes |

|

|

JEAN, trying to be heard over the racket: |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

No, no. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

No, no. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

A HECKLER, imitating a cry from the street |

|

|

Rabbit skins! |

|

|

Laughter, uproar |

|

|

ALL, across the various groups |

|

|

Tell us instead a drinking song. |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Very good! Hurrah! Very good! |

|

|

A DRUNKARD |

|

|

A GROUP |

|

|

Tell us the Credo of the Drunkard. |

|

|

A KNIGHT |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

The Gloria of Ruddy-Face. |

|

|

JEAN, proposing timidly |

|

|

The Hallelujah of Wine? |

|

|

ALL, with joy |

|

|

The Hallelujah of Wine! |

|

|

JEAN turns, his hands clasped, toward the statue of the Virgin. |

|

|

Forgive me, holy Virgin Mary, |

|

|

I will sing a blasphemous song, |

|

|

but it is necessary all the same to earn a living. |

|

|

Hunger cries out in my guts, |

|

|

and if my heart is good Christian, |

|

|

why is my belly pagan? |

|

|

ALL, calling again for the song |

|

|

The Hallelujah of Wine! |

|

|

JEAN, warming up on his instrument. |

|

|

Pater Noster. The wine, it’s God, it’s God the Father, |

|

|

who descends from the very heights of heaven, |

|

|

clad in silky velvet, |

|

|

all the way down my pious throat |

|

|

when I drain my glass. |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Hallelujah! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Hallelujah! Let’s sing the Hallelujah of Wine. |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Hallelujah! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Ave. Beautiful Venus says to suitors: “Good fellow, |

|

|

by night even more than by day, |

|

|

drink aged wine, potion of love; |

|

|

Your heart is as hot as a furnace |

|

|

when you drain your glass.” |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Hallelujah! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Hallelujah! Let’s sing the Hallelujah of Wine! |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Hallelujah! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Credo. Drink no water, a baneful brew— |

|

|

To the water drinker, the infernal abyss! |

|

|

But so that heaven may say to my |

|

|

triumphant nose: “Enter, cardinal!” |

|

|

let’s drain another glass! |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Hallelujah! |

|

|

SCENE 4 |

|

|

THE SAME ONES, THE PRIOR |

|

|

The door of the abbey opens abruptly. The prior appears on the steps. |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

It’s the prior … Let’s take flight! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Away from here, you unspeakable crew! |

|

|

All flee except Jean, dumbfounded. To Jean: |

|

|

And you, base balladeer, the better to damn your soul, |

|

|

you come even to this abbey to insult |

|

|

our mother Mary and her divine child! |

|

|

JEAN, falling to his knees |

|

|

Mercy, Father, mercy! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Despised and cursed clan! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Oh Father, mercy! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Do you not see Satan, |

|

|

He bestrides you; he carries you off. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Mercy! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Here flames and iron engulf you, |

|

|

here tears and groans. Here |

|

|

the frightful gate of Hell opens! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Mercy! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Tremble! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Mercy! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Hell! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Pardon! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Hell! |

|

|

JEAN, as if thunderstruck, stretched out lengthwise on the ground |

|

|

Ah! I am burning! Ah! I’m dying! |

|

|

On his knees |

|

|

Ah! Father, pardon ... |

|

|

Dragging himself toward the Virgin. |

|

|

Pardon, pardon, Mary, |

|

|

See my tears. |

|

|

He sobs. |

|

|

THE PRIOR, aside |

|

|

He weeps ... A little faith, in this withered soul, |

|

|

Pale winter rose, will it flower again? |

|

|

To Jean. |

|

|

Your name? |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Jean. |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

That’s the name of a saint dear to the Virgin. |

|

|

Pointing to the Virgin. |

|

|

This pardon of Mary, it may be won. |

|

|

You’ll be pardoned if, burning like a candle |

|

|

and scented like a censer, |

|

|

at her altar your heart renounces this impure trade |

|

|

without delay, from this evening on. |

|

|

If, full of keen repentance, |

|

|

and shaking off at the threshold the dust of the world |

|

|

you become, from this evening, my brother in this abbey. |

|

|

JEAN, his hands clasped to the Virgin. |

|

|

Lady of Heaven, |

|

|

you know well, and Jesus knows it too, |

|

|

the tender and devoted love with which |

|

|

Jean, the poor jongleur, loves you ... |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Well then? |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

But to swear off, when I am still young, |

|

|

To swear off following you, oh, Freedom, my beloved, |

|

|

carefree sprite with a bright golden smile? |

|

|

It is she whom my heart has chosen as mistress. |

|

|

Hair in the wind, laughing, she takes me by the hand, |

|

|

and leads me off with no concern for the hour or path. |

|

|

the diamonds of the nights, through her are mine! |

|

|

Through her I have space, love, and the world! |

|

|

Through her, the beggar becomes king! |

|

|

By her divine charm, everything smiles on me, everything enchants me. |

|

|

I go, and I breathe, and I dream, and I sing, |

|

|

and to accompany the flight of my song, |

|

|

a concert of birds bubbles up in the green brush. |

|

|

Gracious mistress, and sister I have chosen, |

|

|

must I lose you? Oh, my royal treasure! |

|

|

Oh, Freedom, my beloved, |

|

|

carefree sprite with a bright golden smile! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

A gorgeous mistress, |

|

|

in truth? |

|

|

Fear, poor fool, the fatal caress |

|

|

of her deceitful beauty. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Spring smiles in her train. |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Do you not see Winter, Storm, and Snow? |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Her youth is in flower. |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

But soon her lover, the jongleur, will be old. |

|

|

JEAN, looking at his juggler’s equipment. |

|

|

And you, balls, hoops, old friends full of enthusiasm, |

|

|

Will he throw you away, your unfaithful master? |

|

|

Addressing his vielle: |

|

|

You, whose docile soul sang under my hand? |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Keep them and go off. Go off to die of hunger, |

|

|

in a ditch, without anyone to give you confession, you vile rag … |

|

|

But the abbey, that was the salvation of your soul, |

|

|

the salvation of your body. |

|

|

Smiling. |

|

|

In Lent, no doubt, beans and salted herring; |

|

|

but on major feast days, |

|

|

ah! the plenteous days! |

|

|

Come, see for yourself. |

|

|

Boniface appears atop a donkey that a lay brother holds by the bridle. The donkey also carries two baskets, one containing flowers, the other food and bottles. |

|

|

Cook without equal, |

|

|

Brother Boniface returns from his quest, |

|

|

glorious, smiling, he brings |

|

|

every tasty delight for a feast. |

|

|

SCENE 5 |

|

|

THE SAME ONES, BONIFACE |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Taking flowers and foods one by one from the baskets. |

|

|

First for the Virgin, here are the flowers she loves: |

|

|

carnations, lilacs, forget-me-nots, |

|

|

violet, sweetbriar, and lily, |

|

|

rose, poppy, sunflower, |

|

|

and here too the periwinkle, |

|

|

silver sprig, and buttercup. |

|

|

First for the Virgin, here are the flowers she loves. |

|

|

And for the servants of Madame Mary, |

|

|

here are spring onions |

|

|

and green leeks. |

|

|

Here is garden cress, |

|

|

velvety cabbage, flowery sage ... |

|

|

This is for the servants of Madame Mary. |

|

|

Holy Virgin, the beautiful capon! |

|

|

Father, if you please, feel the weight of this ham ... |

|

|

chitterling sausage, a full quarter of head cheese, |

|

|

saveloy, regular sausage, blood pudding. |

|

|

Look what perfect saltiness; |

|

|

Nothing like it for putting in wine to cook! |

|

|

Wine: we have some, and how exquisite! |

|

|

See how it sparkles in the crystal of the decanter. |

|

|

Sweet Jesus, it is vintage Mâcon! |

|

|

Here are flowers |

|

|

and this beautiful taper |

|

|

for the Virgin. |

|

|

And this for her humble servants. |

|

|

We hear the breakfast bell ring from interior of the abbey; then the voices of |

|

|

the monks in the refectory reciting the Benedicite. |

|

|

Voices of the Monks inside the Abbey. |

|

|

A VOICE |

|

|

Benedicite. |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Benedicite. |

|

|

A VOICE |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Amen! |

|

|

A VOICE |

|

|

ALL |

|

|

Amen! |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

The Benedicite, Father. To the table! To the table! |

|

|

And may a good lunch |

|

|

Showing his provisions. |

|

|

prepare us for dinner. |

|

|

THE PRIOR to Jean, inviting him. |

|

|

To the table! |

|

|

JEAN, as if in ecstasy, hands joined in blissful blessing. |

|

|

To the table! |

|

|

ALL THREE, with varying expressions and gestures. |

|

|

To the table! |

|

|

The Prior, Boniface, and the lay brother with the donkey make their way toward the entrance of abbey. Jean follows them, still hesitating, but attracted by the smell of the food. At the threshold he turns around to get his juggling equipment, which he carries in secretly. Before entering, he makes a humble prayer at the feet of the Virgin. |

|

|

ACT 2 |

|

|

The Cloister |

|

|

At the abbey, in the study hall that leads into the garden. Tables, desks, easels. A statue of the Virgin, recently completed, stands out very much in view, in a pose of indulgence and love. A monk is in the process of painting it. Grouped around the musician monk, other monks finish rehearsing a hymn to the Virgin under his direction which he composed for the occasion; it is the morning of Assumption Day. |

|

|

SCENE 1 |

|

|

JEAN, THE PAINTER MONK, THE POET MONK, THE SCULPTOR MONK, THE MUSICIAN MONK |

|

|

ALL THE MONKS, including the four indicated above. |

|

|

The musician monk directs the vocal ensemble and adds his voice to the mix. |

|

|

Ave rosa speciosa, |

|

|

Ave mater humilium, |

|

|

In hac valle lacrymarum |

|

|

Da robur, fer auxilium. |

|

|

JEAN, musing at a distance |

|

|

The cooking is good at the abbey. |

|

|

I, who did not sup often, |

|

|

now drink good wine, I eat marbled meats. |

|

|

Glorious day! |

|

|

Today the Virgin ascends to heaven, |

|

|

and for her they rehearse a song of thanks. |

|

|

Sadly. |

|

|

A song in Latin! |

|

|

oh you, to whom I owe fat meat and good wine, |

|

|

I would like to celebrate your praises with them. |

|

|

Alas! I don’t know how to sing Latin. |

|

|

SCENE 2 |

|

|

THE SAME CHARACTERS, THE PRIOR, BONIFACE |

|

|

PRIOR entering. |

|

|

That’s very good, brothers. |

|

|

To the Musician Monk. |

|

|

My compliments to the author. |

|

|

To the poet monk, author of the words of the hymn, who steps forward jealously. |

|

|

To the poet, too. |

|

|

Each of the monks resumes his station and work in the study hall: some paint, others sculpt or model, still others copy on vellum. Some dig with a spade at the bottom of the garden and cultivate flowers, and so forth. In a corner, Boniface modestly peels vegetables. |

|

|

THE PRIOR to Jean |

|

|

But what are you doing, alone in this solitary corner? |

|

|

You, an experienced singer, you do not sing? |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Pardon me, Father; |

|

|

But, alas, I know only |

|

|

profane songs in uneducated French. |

|

|

SEVERAL MONKS who have drawn near |

|

|

Oh, Brother Jean! What laziness! |

|

|

Look how fat he’s getting. |

|

|

Touching his stomach |

|

|

Do you feel his stomach growing? |

|

|

BONIFACE, intervening good-naturedly |

|

|

Well what of it! Brother Jean loves good things. |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

To the Virgin, no doubt, he offers this morning |

|

|

as a bouquet the freshness of his complexion, |

|

|

all abloom with lilies and roses. |

|

|

THE MONKS, still without Boniface |

|

|

(The musician, the poet, the painter, and the sculptor) |

|

|

are you sleeping ... |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Brothers, I know my sad unworthiness. |

|

|

Day and night I weep over it. |

|

|

You mock me, but that is little. |

|

|

Your wrath should destroy me this moment; I have well deserved it. |

|

|

Ever since the Virgin, helping mother, |

|

|

guiding me with her white hand, |

|

|

has allowed me to eat my fill |

|

|

in this prosperous abbey, |

|

|

have I earned my bread a single day? |

|

|

No, never has one meritorious deed |

|

|

given witness of my love to heaven. |

|

|

An ignorant monk, an uncouth monk, |

|

|

I know nothing but in the refectory |

|

|

to eat and drink, drink and eat. |

|

|

Everyone in this holy house |

|

|

serves Our Lady with great zeal; |

|

|

there is no altar boy so little |

|

|

that he does not knows how to sing |

|

|

verses or psalms for her in the chapel. |

|

|

And I who would face death |

|

|

with such a joyous heart for her glory, |

|

|

alas, alas, what a dreadful fate! |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

I know nothing but in the refectory, |

|

|

to eat and drink, drink and eat. |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Jean knows nothing but in the refectory |

|

|

To eat and drink, drink and eat. |

|

|

JEAN, to the Prior |

|

|

Ah! Drive me away, Father: |

|

|

I fear that I will bring you misfortune ... |

|

|

Let’s go, jongleur, |

|

|

Take up again your shoulder bag and your poverty. |

|

|

SCENE 3 |

|

|

THE SAME CHARACTERS |

|

|

THE SCULPTOR MONK, approaching Jean. |

|

|

Jongleur, a pitiable profession. |

|

|

Ironically |

|

|

Become a sculptor instead. |

|

|

You can be my pupil … |

|

|

Pointing out the small statue he is in the process of carving with a chisel. |

|

|

Look: the allure of the Queen, with her charming face, |

|

|

rises from the flanks of marble, |

|

|

awakened by a pious chisel. |

|

|

I, in my turn, create her, I her creature, |

|

|

winning heavenly glory. |

|

|

Nothing equals sculpture! |

|

|

THE PAINTER MONK, approaching |

|

|

Brother, you forget painting. |

|

|

Be my pupil, Jean. |

|

|

Inanimate marble cannot give life; |

|

|

but under the all-powerful brush, |

|

|

Pointing to a painting of the Virgin |

|

|

you see her quiver, trembling, subdued, |

|

|

to the lips it reddens, to the expression in the eyes— |

|

|

painting, |

|

|

it is the great art! |

|

|

THE SCULPTOR MONK |

|

|

The great art, |

|

|

it is sculpture! |

|

|

THE POET MONK, approaching |

|

|

Not so. Only poetry ought to take a seat |

|

|

in the place of honor. |

|

|

She is my Lady, and I am her devoted servant. |

|

|

Your art is very coarse. Of choicer essence, |

|

|

the poet, fixing the flight of pure spirit, |

|

|

encloses it, still moving, in verses of gold and azure. |

|

|

Glory to poetry! |

|

|

THE PAINTER MONK |

|

|

Painting, |

|

|

that is the great art! |

|

|

THE SCULPTOR MONK |

|

|

The great art |

|

|

is sculpture! |

|

|

THE PRIOR, intervening |

|

|

Brothers, let’s calm down. |

|

|

THE MUSICIAN MONK, approaching in turn |

|

|

As for me, I imagine that |

|

|

my art alone can make you agree ... |

|

|

See, while you grovel on earth, |

|

|

in what passionate flight |

|

|

music takes off straight up to heaven. |

|

|

Voice of the ineffable, echo of the great mystery, |

|

|

it is the Blue Bird that comes from the Eternal Shore, |

|

|

and the White Ship on the Ocean of Dreams. |

|

|

What does a seraph do in heaven? |

|

|

He sings, again, and always, without rest. |

|

|

Music is a divine art. |

|

|

THE SCULPTOR MONK |

|

|

No, the great art is sculpture. |

|

|

THE PAINTER MONK |

|

|

No, the great art is painting. |

|

|

THE POET MONK |

|

|

Poetry, oh, Queen of Arts! |

|

|

THE MUSICIAN MONK |

|

|

Oh, Music, Queen of Arts! |

|

|

A babbler, the poet! |

|

|

THE PAINTER MONK |

|

|

Sculptors are just masons! |

|

|

THE SCULPTOR MONK |

|

|

Painters, all they do is daub! |

|

|

JEAN frightened |

|

|

Good God! What a storm! |

|

|

THE POET MONK ironically, to the musician who threatens him |

|

|

Music softens manners. |

|

|

(Tumult) |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Brothers, what discord in this haven! |

|

|

It’s Virgil’s turn of phrase. |

|

|

By order of Apollo, by order of the prior, |

|

|

Let Muse to Muse offer a sisterly kiss. |

|

|

The four rivals embrace, but reluctantly. |

|

|

Now everyone come to the chapel, |

|

|

to the feet of Our Lady, and with humbler hearts |

|

|

pray to receive her new image. |

|

|

Carrying the statue of the Virgin, the monks go back in front of the Prior and resume singing. |

|

|

SCENE 4 |

|

|

JEAN, BONIFACE |

|

|

JEAN, sitting head in hands. |

|

|

I alone offer nothing to Mary. |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Come on, Brother Jean, don’t envy them. |

|

|

They’re all full of pride, you see, |

|

|

And paradise, that’s not for them. |

|

|

JEAN, disheartened |

|

|

Paradise! |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

If one must swell with glory, |

|

|

when I prepare a good meal, |

|

|

I am also doing work of merit. |

|

|

I am a sculptor of nougats; |

|

|

a painter, by the soft color of my creams. |

|

|

A chicken cooked medium rare is alone worth a thousand poems. |

|

|

And what a symphony to ravish heaven and earth |

|

|

is a table where harmonious order holds sway! |

|

|

JEAN, with conviction |

|

|

Certainly. |

|

|

BONIFACE, a little smug |

|

|

But to please Mary |

|

|

I remain simple. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

Simple, alas, |

|

|

I am too much so … She loves to be venerated |

|

|

in this Latin I do not know. |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

And I know so little ... just kitchen Latin ... |

|

|

Is that your worry? |

|

|

Naïvely |

|

|

Come on, the Virgin understands the French language quite well, too; |

|

|

in her tenderness she senses if there is need. |

|

|

For the humble, Mary has the generosity of a sister. |

|

|

And I read in a book a marvelous story |

|

|

in which you see clearly that she gave her heart |

|

|

to the simplest, humblest flower. |

|

|

Telling the story. |

|

|

Mary was fleeing with the baby Jesus over mountains and plains, |

|

|

but the winded donkey can go no further; |

|

|

and see here how over there, on the side of the hill, |

|

|

the bloodthirsty cavalry of the child-killing king suddenly appeared. |

|

|

“Oh, my son, where to hide you in your helplessness?” |

|

|

A rose was blooming on the roadside: |

|

|

“Rose, beautiful rose, be good to my child! |

|

|

So that he can nestle there, open wide the cup of your bloom; |

|

|

save my Jesus from dying.” |

|

|

But for fear of spoiling the crimson of her dress, the proud flower |

|

|

replied: “I don’t want to open.” |

|

|

A sage plant was blooming on the roadside; |

|

|

“Sage, my little sage, open your leaves to my child.” |

|

|

And the good plant opens her leaves so wide |

|

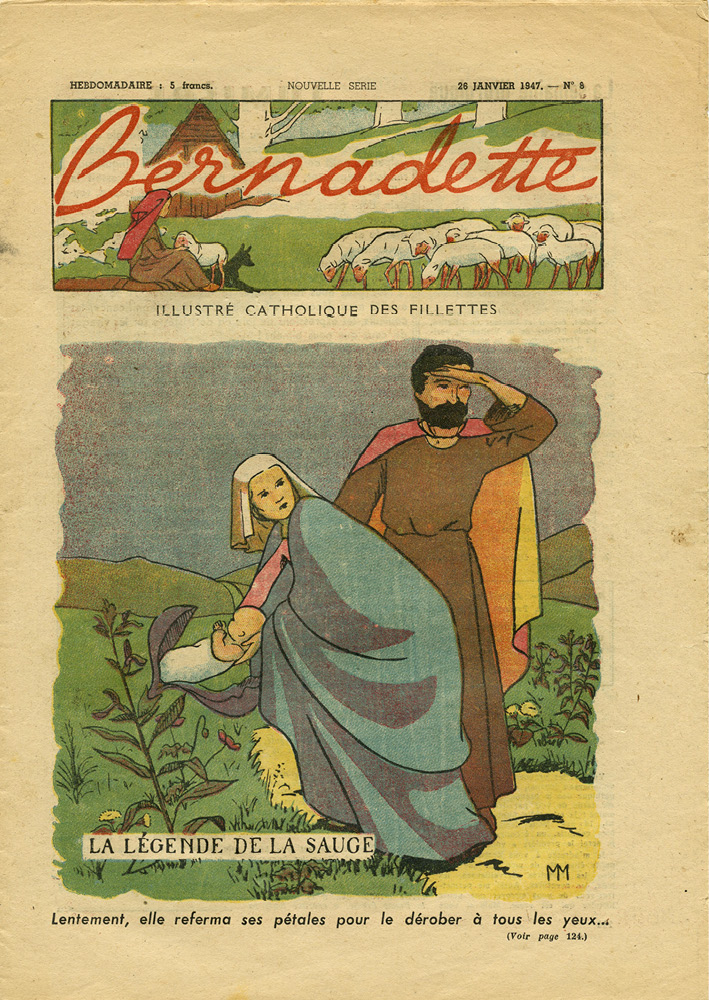

Fig. 33: Front cover of Bernadette: Illustré catholique des fillettes, no. 8, January 26, 1947.

|

JEAN tenderly, an aside |

|

|

Oh, miracle of love! |

|

|

BONIFACE finishing |

|

|

And the Virgin, blessed among all women, |

|

|

blessed the humble sage among all flowers! |

|

|

Aside, with great conviction. |

|

|

In fact, sage is prized in cooking. |

|

|

JEAN, aside, with enthusiasm, his eyes raised to heaven |

|

|

If your white hand should bless me someday, |

|

|

let death come. To die beneath your gaze, what a feast day! |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

First we’ll celebrate the dinner I’m preparing. |

|

|

I must check on my young turkey, |

|

|

Coming back |

|

|

for I please the Virgin in watching over the oven. |

|

|

Did Jesus not receive with an equal smile |

|

|

and the pipe-tune of the poor shepherd? |

|

|

He exits running. |

|

|

SCENE 5 |

|

|

JEAN left alone, vaguely repeating the |

|

|

words just uttered by Boniface. |

|

|

The pipe-tune of the poor shepherd … |

|

|

Changing his tone, and with emotion. |

|

|

What a sudden ray of light, |

|

|

and what a feeling in my heart! |

|

|

He’s right, the Virgin is not proud. |

|

|

The shepherd, the jongleur, in her eyes, equals the king. |

|

|

He walks forward, eyes and hands toward heaven. |

|

|

Virgin, mother of love; Virgin, supreme goodness. |

|

|

Just as the Christ-child smiled at the tune of the shepherd, |

|

|

if the jongleur dares to honor you likewise, |

|

|

deign to smile from the threshold of heaven! |

|

|

Jean remains in a posture of divine invocation. |

|

|

The orchestra plays the mystic pastorale that connects the two acts. |

|

|

ACT 3 |

|

|

Mystic Pastorale |

|

|

In the chapel of the abbey. In plain sight on the altar, the painted |

|

|

statue of the Virgin. The chapel is arranged so that |

|

|

people can see Jean from the sides without his noticing those who watch him. |

|

|

SCENE 1 |

|

|

In the distance we hear the monks singing the hymn to the Virgin. |

|

|

THE PAINTER MONK, alone in front of the statue |

|

|

One last look at my work, at my Virgin ... |

|

|

The chant grows faint and dies ... In the silence, where |

|

|

the still flame of the candles sleeps, |

|

|

for her jealous painter she is even more beautiful. ... |

|

|

But someone enters.—It’s Jean ... Why all this equipment? |

|

|

He hides behind a column. |

|

|

SCENE 2 |

|

|

THE SAME CHARACTER, JEAN |

|

|

Entrance of Jean, still clad in his monk’s robe, carrying his vielle and |

|

|

jongleur’s shoulder bag. He enters on tiptoe, looking all around anxiously. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

No one ... Come on, be brave! |

|

|

No one comes any more at this hour. |

|

|

Approaching the altar. |

|

|

Venerable mother of Jesus, |

|

|

so I am here alone before you ... |

|

|

Trembling, my heart full of love and pain, |

|

|

I fall at your knees ... |

|

|

hear my prayer: |

|

|

Alas, poor Jean is nothing but a worthless jongleur. |

|

|

Yet let him, in his humble manner, |

|

|

work beneath your eyes, oh, Virgin, in your honor. |

|

|

Stripping off his monk’s robe, he appears in the outer tunic of a jongleur, spreads |

|

|

his carpet, and, grabbing his vielle, draws from it the same chords that announced |

|

|

his arrival at the town square of Cluny. |

|

|

THE PAINTER MONK. |

|

|

He’s going mad. I will run to warn the Prior. |

|

|

He goes out swiftly. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

I begin. |

|

|

He greets the Virgin. |

|

|

Make way, make way, silence! |

|

|

Listen to Jean, Jongleur King. |

|

|

Carried away by habit, he roams, with a cup in hand, through a circle of |

|

|

imaginary spectators. |

|

|

But first a few pennies in my cup ... |

|

|

Stopping, embarrassed, at the Virgin. |

|

|

Force of habit! Forgive me. |

|

|

Resuming his routine. |

|

|

Attention! ... |

|

|

To please you, |

|

|

I will sing a song of war. |

|

|

when they are mounted and decked out; |

|

|

it’s nice to see these weapons gleam |

|

|

beneath golden standards. |

|

|

To gain honor and fine land, |

|

|

between you and me, noble companions, |

|

|

let’s follow war!” |

|

|

SCENE 3 |

|

|

JEAN alone; then the PRIOR, BONIFACE, the PAINTER MONK, the POET MONK, the MUSICIAN, SCULPTOR, and OTHER MONKS |

|

|

JEAN, aside |

|

|

But all this racket frightens the Virgin. |

|

|

Addressing the Virgin, in his simplicity. |

|

|

Do you prefer, perhaps, |

|

|

the Romance of Love? |

|

|

He starts the song, which was well known at that time. |

|

|

Memory fails him; aside. |

|

|

I don’t remember it anymore. |

|

|

Beginning another. |

|

|

“… Lovely Erembourg |

|

|

atop the highest tower ...” |

|

|

Memory fails him again. |

|

|

Oh, treacherous memory ... |

|

|

Well then, stupid minstrel, keep repeating |

|

|

the never-ending |

|

|

of Robin and Marion. |

|

|

“To the edge of the pretty countryside |

|

|

Marion, shepherdess quite sensible, |

|

|

still thinks |

|

|

of her loves. |

|

|

Aé! |

|

|

A handsome horseman |

|

|

just passed by, proudly sporting armor |

|

|

Saderaladon— |

|

|

Sing little nightingale— |

|

|

‘I am the King. |

|

|

Be all mine.’ |

|

|

Aé! |

|

|

‘No, dear Lord, I will stay sensible.’ |

|

|

Saderaladon— |

|

|

Sing, little nightingale— |

|

|

‘With my dress and my cheese |

|

|

I belong to Robin, |

|

|

I love Robin.’ |

|

|

Aé! Aé!” |

|

|

While Jean sings the pastourelle, the Prior, led by the painter monk, |

|

|

arrives with Boniface. Jean cannot see them; they observe the jongleur’s routine. |

|

|

Several times, the outraged Prior makes as if to throw himself on Jean but is held back by Boniface. |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Sacrilege! |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Calm down. |

|

|

The song ends with |

|

|

a Catholic marriage of |

|

|

the girl to the boy. |

|

|

SCENE 4 |

|

|

THE SAME CHARACTERS, ALL THE MONKS |

|

|

JEAN, in the manner of a quick sales pitch |

|

|

And now do you want juggling tricks, |

|

|

or even ones of sorcery? |

|

|

Should I summon up griffins and flying devils |

|

|

in the flaming air? |

|

|

Stopping, ashamed of this sacrilege; to the Virgin. |

|

|

Forgive me, old habit! |

|

|

Moving closer to the Virgin and in secret. |

|

|

Between you and me, I exaggerate! |

|

|

But you know that a pitch |

|

|

is never completely honest. |

|

|

Resuming. |

|

|

Attention! To finish the performance, |

|

|

I will have the honor to dance before you |

|

|

With humility. |

|

|

quite simply a dance from back home. |

|

|

THE PRIOR, ready to rush forward. |

|

|

That’s it, I’m going ... |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Patience! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

I don’t believe that David was a pagan. |

|

|

The jongleur begins to dance a kind of country step with pliés and shouts given at intervals. He dances faster and faster, until the moment when, covered in sweat, he falls out of breath at the feet of the Virgin and prostrates himself in long and intense veneration. All the monks arrive successively, including the musician monk, the poet monk, and the sculptor monk. |

|

|

The monks aside, their anger contrasting with the jongleur’s dance. |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Sacrilege! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Anathema! |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Mercy! |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

he wallows and plays |

|

|

in his impiety. |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Anathema! |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Mercy! |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

What an insult ... |

|

|

Vengeance |

|

|

for the Mother of God! |

|

|

Let us chase him away, |

|

|

vile spawn, |

|

|

chase him away from this holy place! |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Mercy, mercy for him! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Anathema! |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Sacrilege! |

|

|

Death to the blasphemer! |

|

|

Furious, the monks are about to throw themselves on Jean. But Boniface stops them with a gesture toward the statue of the Virgin. |

|

|

SCENE 5 |

|

|

THE SAME CHARACTERS, THE VOICES OF UNSEEN ANGELS |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Get back, everyone. |

|

|

The Virgin protects him! |

|

|

The picture ... Do you see ... Do you see? |

|

|

It’s beginning to shine |

|

|

with a strange light ... |

|

|

A gentle glance arises at the edge of the eyelid, |

|

|

a smile is nearly awakening on the mouth. |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Oh, miracle! |

|

|

THE PAINTER MONK, radiant with pride. |

|

|

Oh, painting! |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Ah, look! ... The white hand |

|

|

reaches toward the jongleur in a maternal gesture ... |

|

|

The exquisite brow |

|

|

tilts down with love … |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Oh, miracle! |

|

|

We hear heavenly voices. |

|

|

BONIFACE |

|

|

Listen to the music of heaven. |

|

|

VOICES OF INVISIBLE ANGELS |

|

|

Hosannah! Glory to Jean! Hosannah! Glory, glory! |

|

|

Glory in the heights of heaven! Glory and serenity! |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Mystery worthy of adoration! |

|

|

The Prior, followed by the monks, draws near to Jean, who is still at the feet of the Virgin, lost in prayer. Jean gets up and turns at the noise, frightened at being caught in his jongleur’s outfit. |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

It’s the Prior! |

|

|

Falling on his knees. |

|

|

Pardon! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Get up: |

|

|

it is I who should be at your knees. |

|

|

You are a great saint … Pray, pray for us. |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Pray for us. |

|

|

JEAN, thinking they are mocking him |

|

|

No, don’t mock me. Punish me, Father. |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

Mock you, punish you? |

|

|

You, the honor of the monastery, |

|

|

pointing to the altar, |

|

|

when with my own eyes I see the Virgin bless you! |

|

|

JEAN, very simply |

|

|

I see nothing. |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Strange marvel! |

|

|

THE PRIOR |

|

|

A teaching from heaven, a lesson without equal |

|

|

of innocent virtue, of holy humility. |

|

|

Addressing the Virgin. |

|

|

And yet, oh, Virgin Queen, |

|

|

Mother of love and goodness, |

|

|

divine and living paleness, |

|

|

to ease him of his trouble, |

|

|

reveal yourself |

|

|

to the eyes, still closed, of your dear jongleur. |

|

Fig. 34: The juggler collapses: a scene from Massenet’s Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame. Illustration by Edouard Zier. Le Monde Illustré 2459 (May 14, 1904): 395.

|

The altar, up to this point dimly lit, gleams with an intense light. |

|

|

And detaching itself from the hands of the Virgin, the halo of the |

|

|

blessed comes to shine above the head of Jean. |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Miracle! Miracle! |

|

|

JEAN, as if he has been struck in the heart. |

|

|

Radiance, |

|

|

happiness, |

|

|

I die |

|

|

in ecstasy. |

|

|

He faints in the arms of the Prior. |

|

|

THE MONKS, falling to their knees. |

|

|

JEAN, lifting himself halfway, in a simple and gentle tone, |

|

|

At last! I understand Latin. |

|

|

He falls back. |

|

|

VOICES OF TWO ANGELS, unseen, |

|

|

Hallelujah! |

|

|

Caressed by the breeze of our wings, |

|

|

the jongleur, smiling, falls asleep. |

|

|

Look, the golden gate to heaven opens |

|

|

before his humble zeal; |

|

|

on his head crowned with light |

|

|

shed your petals, cornflowers and lilies. |

|

|

Amid incense and prayer, |

|

|

let us sow the flowers of paradise. |

|

|

Hallelujah! |

|

|

It rains cornflowers and lilies. |

|

|

Clouds of incense appear. |

|

|

THE MONKS, reciting litanies. |

|

|

mater castissima, |

|

|

mater inviolata, |

|

|

ora pro nobis. |

|

|

The Virgin begins to ascend slowly toward heaven. |

|

|

We then see her, surrounded by angels, in the middle of paradise. |

|

|

JEAN, near death, in ecstasy. |

|

|

Radiant vision! |

|

|

I see the heavens open! ... |

|

|

Divine scents ... the cool fluttering of wings ... |

|

|

in blue meadows, blooming with new flowers, |

|

|

under the eyes of Mary and the infant Jesus |

|

|

I see passing the brotherly round of angels and chosen ones ... |

|

|

The Virgin beckons me with her hand ... I come ... |

|

|

What a gentle smile ... Oh! Her white hand ... |

|

|

BONIFACE, with ardent and radiant piety. |

|

|

Freed from earthly bonds, |

|

|

he flies away to the happiness of an eternal Sunday ... |

|

|

No more sorrow, no more worry ... |

|

|

He enters the heavenly round ... |

|

|

JEAN |

|

|

I am here! ... |

|

|

He dies. |

|

|

THE PRIOR, reciting |

|

|

VOICES OF THE ANGELS |

|

|

Amen! |

|

|

THE MONKS |

|

|

Amen! |

|

|

THE END. |

|