6. The Professor-Poet Katharine Lee Bates

© 2022 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0284.22

Katharine Lee Bates, who lived from 1859 to 1929, was first a student and later a professor of English literature at Wellesley. The famous women’s college in Massachusetts had been founded in 1870, not even a decade before she matriculated. Independent of her activities there as a teacher and scholar, she was the author of poetry, novels, children’s literature, and more.

Today Bates is remembered mostly for the lyrics of “America the Beautiful.” Her words came to be paired with the melody only more than a decade after she originally composed the poem. Thereby hangs a tale. In 1893, the poet wrote down a first, partial draft of the words in her elation at the vista she saw upon reaching the summit of Pikes Peak in Colorado. The year has a strong bearing on her patriotic epiphany, since it witnessed the opening of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, Illinois. This extravaganza marked the four-hundredth anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World. Also called the Columbian Exposition, the exhibition was accompanied by much patriotic fervor throughout the US, including the release of commemorative postage stamps and coins. Two years later, a first version of the poem was printed in 1895 under the one-word title “America,” in the Independence Day issue of a Boston-based church weekly. It was set to music repeatedly. In 1904, the text of her piece was matched with a melody entitled “Materna” that Samuel A. Ward (whom she never met and who died in 1903) composed as the setting for a seventeenth-century poem, “O Mother dear, Jerusalem.” The two compositions dovetailed perfectly: both were in what is called common meter double. The combination of her words and his music resulted in a hymn that won the status of the anthem we still know today. Her final revisions are found in the form she published in 1911.

Despite the undeniably powerful name-recognition that “America the Beautiful” retains in the United States, it would be unfair to present Bates as nothing more than a one-hit wonder. After receiving her undergraduate degree in 1880, she taught high school before pursuing advanced studies. In 1891, she earned a master’s degree from her alma mater and began teaching in the English department there. In the first two decades of her career, she worked extensively with medieval literature, not just as a teacher and researcher but also as a poet and even as a children’s book author.

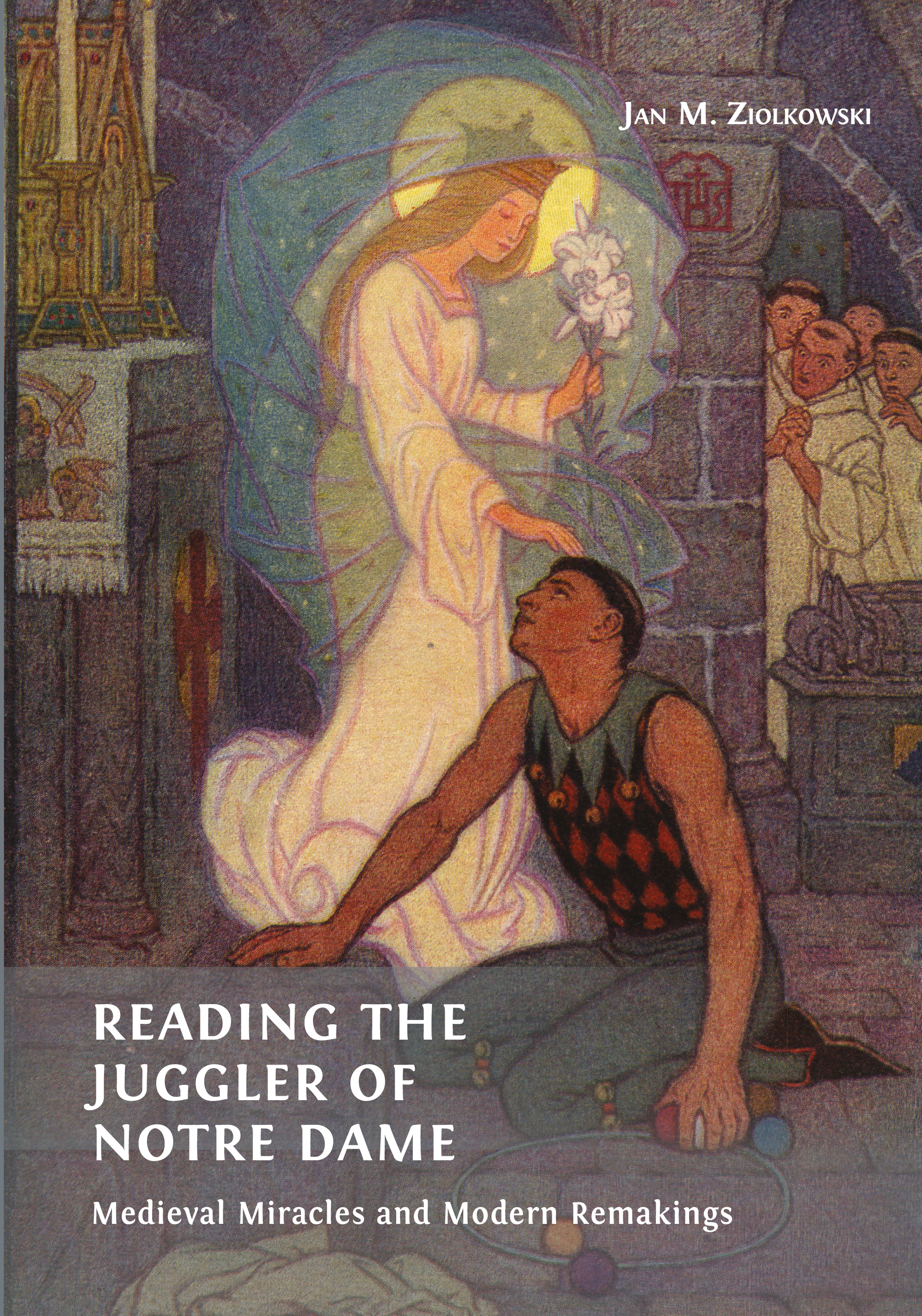

Fig. 35: Katharine Lee Bates. Photograph, early twentieth century. Photographer unknown. Wellesley, MA, Archives of Wellesley College. Image courtesy of Wellesley College. All rights reserved.

Committed to maintaining what might be called her creative side and beyond it her wholeness as a woman, she once wrote: “My heart isn’t quite pressed flat in a Middle English dictionary.” Over the past few decades one aspect of her interior life that has elicited considerable attention relates to her fellow Wellesley professor, housemate, intimate friend, and perhaps even more, Katherine Coman. The failed courtships of Bates by at least two men have also been the object of fascination. Could any of these emotional entanglements have informed moments in the poem that she made out of our story?

At an intersection between her scholarship and her poetry, Bates wrote a verse adaptation entitled “Our Lady’s Tumbler.” She published this poem first in 1904 and a few times afterward. It totals fifty-four lines, in nine six-line stanzas (sixains or sextains) of iambic pentameter that are uniformly rhymed ababab. The form resembles the Sicilian sestet. Anything but a verbatim translation of the thirteenth-century French poem, these 428 words reduce the cast of characters to the tumbler and the object of his devotion, Our Lady. Though the dancer is a convert in a monastery, his fellow monks and the abbot or prior are omitted from the picture.

In “Our Lady’s Tumbler” Bates’s bent as a professional medievalist shows strongly in two ways. One is that her poem opens bookishly, by conjuring up the brittleness of the manuscript folio on which the text of the medieval legend was supposedly transmitted. The other is her diction. Some terms relate to religious practices and customs that were entrenched within Christianity many centuries ago, often as maintained in Roman Catholicism even long after the Middle Ages. But other words are archaisms and obsolete English that are meant to evoke the society and speech of “ye olde” days when the dramatic action of the piece purportedly occurred. These choices in diction hold true to a style that was once commonly used in writing about olden times. This pseudo-medieval tic owed much to Sir Walter Scott, whose choice of vocabulary in his fiction about the Middle Ages exerted an irresistible influence on many later authors for more than a century. Bates herself had visited numerous sites in the British Isles that were associated with the novelist and his oeuvre. Her mannerism, including the archaizing lexicon, was encouraged more generally by the medieval revival. The movement made a medieval-esque style in architecture, decorative arts, and literature popular throughout the West in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

|

On a leaf that waits but a breath to crumble |

||

|

Is written this legend of fair Clairvaux, |

||

|

How once at the abbey gates stood humble |

||

|

A carle more supple than beechen bow, |

||

|

5 |

And they cloistered him, though to dance and tumble |

|

|

Was all the lore he had wit to know. |

||

|

He had never a vesper hymn nor matin, |

||

|

Pater noster nor credo learned; |

||

|

Ill had the wood-birds taught him Latin, |

||

|

10 |

But to every wayside cross he turned, |

|

|

Because of the gold his gambols earned. |

||

|

So they cloistered him at his heart’s desire, |

||

|

Though never a stave could he tone aright. |

||

|

15 |

With shame and grief was his soul a-fire |

|

|

To stand in the solemn candle-light |

||

|

Abashed and mute before priest and choir |

||

|

And the little lark-voiced acolyte. |

||

|

Of penance and vigil he was not chary, |

||

|

20 |

With bitter rods was his body whipt; |

|

|

Yet his heart, like a stag’s, was wild and wary, |

||

|

Till at last, one morn, from the Mass he slipt |

||

|

And hied him down to a shrine of Mary |

||

|

25 |

“Ah, beauteous Lady,” he cried, imploring |

|

|

The image whose face in the gloom was wan, |

||

|

“Let me work what I may for thine adoring, |

||

|

Though less than the least of thy clergeons can, |

||

|

But here thou are lonely, while chants are soaring |

||

|

30 |

In the church above; and a dancing-man |

|

|

And vaulted before her the vault of Champagne. |

||

|

On his head and hands he tumbled featly, |

||

|

Did the Arragon twirl and the leap of Lorraine, |

||

|

35 |

Till the Queen of Heaven’s dim lips smiled sweetly |

|

|

As she watched his joyance of toil and pain. |

||

|

He plied his art in that darksome place |

||

|

And never again he scourged nor fasted |

||

|

40 |

His eager body whose lissome grace |

|

|

Cheered Our Lady till years had wasted |

||

|

The dancer’s force, and he drooped apace. |

||

|

And once, when the buds were bright on the larches |

||

|

And the young wind whispered of violets, |

||

|

45 |

He came like a wounded knight who marches |

|

|

To the tomb of Christ. With striving and sweats |

||

|

He made there under those sombre arches |

||

|

The Roman spring and the vault of Metz. |

||

|

Then he could do no more and, with hand uplifted, |

||

|

50 |

Saluted Our Lady and fell to earth, |

|

|

Where the monks discovered his corse all drifted |

||

|

Over with blooms of celestial birth. |

||

|

For when human worship at last is sifted, |

||

|

Our best is labor and love and mirth. |

||