7. The Philosopher-Historian Henry Adams

© 2022 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0284.23

The American intellectual Henry Brooks Adams, whose life spanned the eight decades from 1838 through 1918, appreciated full well the privilege that birth from the bluest of blue blood accorded him. In The Education of Henry Adams, the author admitted of himself, using the third person as he did strikingly throughout the memoir, “Probably no child, born in the year, held better cards than he.” In John Adams and John Quincy Adams, he benefited from both a great-grandfather and a grandfather who had served as US Presidents. The political career of Charles Francis Adams Sr., his father, culminated in service as Minister to the United Kingdom (as the ambassador was then styled) under Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, from 1861 to 1868. During those seven years, Henry upheld a family tradition by flanking Charles Sr. as private secretary.

Though ancestry may have seemed to destine Henry Adams for prominence in politics, he in fact made his mark not as a leader but rather as an observer of men. Sure, he had a spell as a tenured professor at Harvard University from 1870 to 1877, but ultimately, by resigning his position in medieval history there, he renounced even the opportunity to guide others through teaching. Instead, he produced fiction such as Democracy: An American Novel, printed anonymously in 1880, and Esther, another novel, released under the female pseudonym Frances Snow Compton in 1884. He penned the innumerable pages of The History of the United States of America during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, nine volumes that appeared between 1889 and 1891. Near the end of his life, he published his most famous book, the autobiography entitled The Education of Henry Adams, in 1918. This is to say nothing of his remarkable letters, which fill six stout tomes.

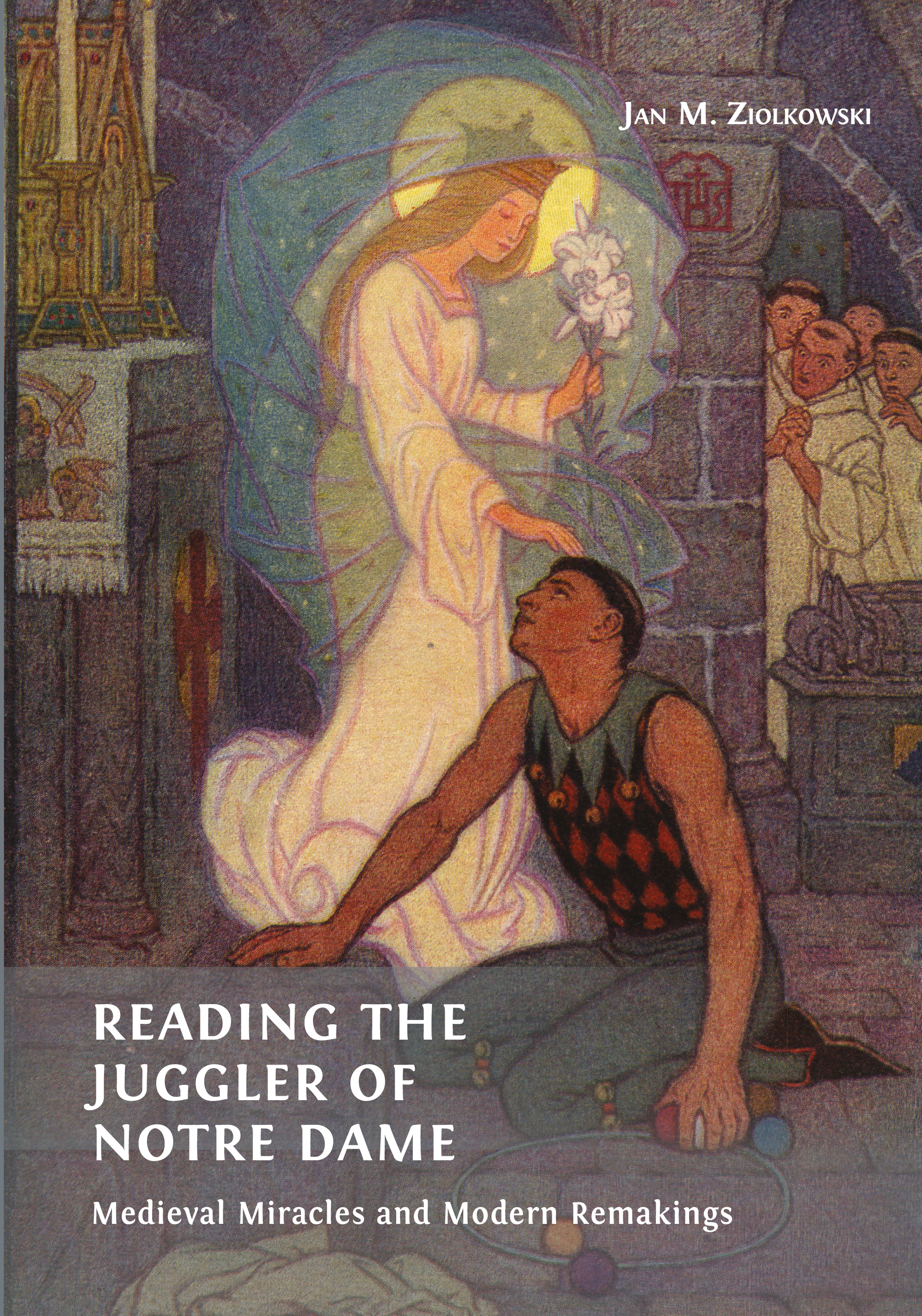

Fig. 36: Henry Adams in the library of his home, 1603 H Street NW, 1891. Photographic self-portrait (MS Am 2327). Image courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

The work of concern here is Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, first printed privately in 1904. By today’s lights it could be considered a cultural and intellectual history, but the contents defy facile categorization into any conventional genre. Forming a pair (or more accurately an odd couple) with his memoir, it is a meditation that sets the culture of Western Europe in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries against that of the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In both titles he sought to identify the forces that propelled the respective eras. In the Middle Ages he pinpointed the faith vested in the Virgin Mary; in modernity, the electric power embodied in the dynamo.

For all its strangeness, Mont Saint Michel and Chartres was an oft-reprinted bestseller. The thirteenth of its sixteen chapters, entitled Mont Saint Michel and Chartres: “Les Miracles de Notre Dame,” explores, as the French would suggest, miracles of the Virgin Mary. It culminates in lengthy quotations from “Our Lady’s Tumbler,” reproduced from the medieval text with Adams’s translations in parallel columns. The format reveals much about the writer’s imagined audience, whom he expected to have sufficient command of the modern foreign language to enable them, with the help of his English, to muddle their way or better through the original poetry. The excerpts, totaling only a few pages in a long book, are tied together through intervening paraphrase and brief commentary. The section could not have failed to spark interest for decades to come in the tale of the medieval entertainer among admirers of Adams, including notably the poet W. H. Auden.

In the closing decades of the nineteenth century, the philologist Gaston Paris salvaged the medieval French poems from the dusty shelves of scholarly libraries and thrust it before his countrymen for their attention and admiration. If the Frenchman had a counterpart in the United States of the early twentieth century, it would have to be Henry Adams. By the time Adams polished off his curious study of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, several renderings of “Our Lady’s Tumbler” into English existed. Despite being short in length and small in size, these books played an essential role in familiarizing the Anglophone world, perhaps especially in the New World, with the poem. Yet Adams’s prose gave the tumbler added cachet.

The American writer observed correctly that the piece from the Middle Ages had achieved greater popularity in his day than it had done in its own. To take one crude measure that ignores the incommensurability of medieval scribal culture with the era of the printing press, the five extant manuscripts of the thirteenth-century French could not begin to compete with the untold thousands of copies of modern English translations already in circulation by the early years of the twentieth century.

In the original poem the Francophile Adams detected “a quiet sense of humour that pleases modern French taste.” Though he abstained from invoking the concept of irony, the reader is left wondering if the historian was not projecting upon the verse from the Middle Ages the same spirit—the Gallic wit—that manifests itself ever so gently in Anatole France’s retelling. But this is all guesswork: the American, in his disquisition on the contrasts between the medieval and the modern, never came close to mentioning such facets of contemporary mass culture as the short story, let alone the opera composed by Jules Massenet and sung by Mary Garden, however conversant with them he proved himself to be in his immense personal correspondence.

In Mont Saint Michel and Chartres Adams’s heart takes wing and flies back from his own days to the Middle Ages. He may well have identified with the jongleur, both of them fully comfortable in no world, both characters striving for recognition from seemingly unattainable women to whom they were devoted. If such conjectural correspondences between Adams’s and the tumbler’s lives seem enlightening, what should we make of the Virgin? Henry’s wife Clover left him a widower after her death by suicide in 1885 at the age of 42. Afterward he became stuck in a relationship with the younger and married Elizabeth Sherman that remained, contrary to his desires, platonic. His idealization of medieval Marianism and more generally of women in the Middle Ages ought not to be correlated too facilely with his own supposed experiences of the women in his own life. Then again, they should not be set aside. Adams’s treatment of the tumbler could very well call for psychological or even psychoanalytic criticism.

Whatever verdicts we reach on such matters, there can be no doubt that because of his fascination with late Romanesque and early Gothic French architecture, the American historian could visualize the action and movement in “Our Lady’s Tumbler” as he could have done with few other poems from medieval times. He had the imagination to transport himself to the crypt and to see in his mind’s eye the athletic devotions of the performer. The vividness with which he re-created the scene could not have failed to stir readers. If he resorts to the word naïveté in summing up the poem, he means it as a compliment.

The text, English and French alike, has been unaltered, except that in extracts from the original poem line numbers have been added to facilitate consultation of the standard editions and of the fresh translation with which this book begins. The poetry is iambic tetrameter couplets, mostly rhymed aabbccdd.

Les Miracles de Notre Dame

… A better [miracle] is that called the “Tombeor de Notre Dame,” only recently printed; told by some unknown poet of the thirteenth century, and told as well as any of Gaultier de Coincy’s. Indeed the “Tombeor de Notre Dame” has had more success in our time than it ever had in its own, as far as one knows, for it appeals to a quiet sense of humour that pleases modern French taste as much as it pleased the Virgin. One fears only to spoil it by translation, but if a translation be merely used as a glossary or footnote, it need not do fatal harm. The story is that of a tumbler—tombeor, street-acrobat—who was disgusted with the world, as his class has had a reputation for becoming, and who was fortunate enough to obtain admission into the famous monastery of Clairvaux, where Saint Bernard may have formerly been blessed by the Virgin’s presence. Ignorant at best, and especially ignorant of letters, music, and the offices of a religious society, he found himself unable to join in the services:—

|

25 |

Car n’ot vescu fors de tumer |

For he had learned no other thing |

|

Et d’espringier et de baler. |

Than to tumble, dance and spring: |

|

|

Treper, saillir, ice savoit; |

Leaping and vaulting, that he knew, |

|

|

Ne d’autre rien il ne savoit; |

But nothing better could he do. |

|

|

Car ne savoit autre leçon |

He could not say his prayers by rote; |

|

|

30 |

Ne “pater noster” ne chançon |

Not “Pater noster”; not a note; |

|

Ne le “credo” ne le salu |

||

|

Ne rien qui fust a son salu. |

Nothing to help his soul in need. |

Tormented by the sense of his uselessness to the society whose bread he ate without giving a return in service, and afraid of being expelled as a useless member, one day while the bells were calling to Mass he hid in the crypt, and in despair began to soliloquize before the Virgin’s altar, at the same spot, one hopes, where the Virgin had shown herself, or might have shown herself, in her infinite bounty, to Saint Bernard, a hundred years before: –

|

“Hai,” fait il, “con suis trais! |

“Ha!” said he, “how I am ashamed! |

|

|

125 |

Or dira ja cascuns sa laisse |

To sing his part goes now each priest, |

|

Et jo suis çi i bues en laisse |

And I stand here, a tethered beast, |

|

|

Qui ne fas ci fors que broster |

Who nothing do but browse and feed |

|

|

Et viandes por nient gaster. |

And waste the food that others need. |

|

|

Si ne dirai ne ne ferai? |

Shall I say nothing, and stand still? |

|

|

130 |

Par la mere deu, si ferai! |

No! by God’s mother, but I will! |

|

Ja n’en serai ore repris; |

She shall not think me here for naught; |

|

|

Jo ferai ce que j’ai apris; |

At least I’ll do what I’ve been taught! |

|

|

Si servirai de men mestier |

At least I’ll serve in my own way |

|

|

I.a mere deu en son mostier; |

God’s mother in her church to-day. |

|

|

135 |

Li autre servent de canter |

The others serve to pray and sing; |

|

Et jo servirai de tumer.” |

I will serve to leap and spring.” |

|

|

Sa cape oste, si se despoille, |

Then he strips him of his gown, |

|

|

Deles l’autel met sa despoille, |

Lays it on the altar down; |

|

|

Mais por sa char que ne soit nue |

But for himself he takes good care |

|

|

140 |

Une cotele a retenue |

Not to show his body bare, |

|

Qui moult estait tenre et alise, |

But keeps a jacket, soft and thin, |

|

|

Petit vaut miex d’une chemise, |

Almost a shirt, to tumble in. |

|

|

Siest en pur le cors remes. |

Clothed in this supple woof of maille |

|

|

Il s’est bien chains et acesmes, |

His strength and health and form showed well, |

|

|

145 |

Sa cote çaint et bien s’atorne, |

And when his belt is buckled fast, |

|

Devers l’ymage se retorne |

Toward the Virgin turns at last: |

|

|

Mout humblement et si l’esgarde: |

Very humbly makes his prayer; |

|

|

“Dame,” fait il, “en vostre garde |

“Lady!” says he, “to your care |

|

|

Comant jo et mon cors et m’ame. |

I commit my soul and frame. |

|

|

150 |

Douce reine, douce dame, |

Gentle Virgin, gentle dame, |

|

Ne despisies ce que jo sai |

Do not despise what I shall do, |

|

|

Car jo me voil metre a l’asai |

For I ask only to please you, |

|

|

De vos servir en bone foi |

To serve you like an honest man, |

|

|

Se dex m’ait sans nul desroi. |

So help me God, the best I can. |

|

|

155 |

Jo ne sai canter ne lire |

I cannot chant, nor can I read, |

|

Mais certes jo vos voil eslire |

But I can show you here instead, |

|

|

Tos mes biax gieus a esliçon. |

All my best tricks to make you laugh, |

|

|

Or soie al fuer de taureçon |

And so shall be as though a calf |

|

|

Qui trepe et saut devant sa mere. |

Should leap and jump before its dam. |

|

|

160 |

Dame, qui n’estes mie amere |

Lady, who never yet could blame |

|

A cels qui vos servent a droit, |

Those who serve you well and true, |

|

|

Quelsque jo soie, por vos soit!” |

All that I am, I am for you.” |

|

|

Lors li commence a faire saus |

Then he begins to jump about, |

|

|

Bas et petits et grans et haus |

High and low, and in and out, |

|

|

165 |

Primes deseur et puis desos, |

Straining hard with might and main; |

|

Puisse remet sor ses genols, |

Then, falling on his knees again, |

|

|

Devers l’ymage, et si l’encline: |

Before the image bows his face: |

|

|

“He!” fait il, “tres douce reine |

“By your pity! by your grace!” |

|

|

Parvo pitie, par vo francise, |

Says he, “Ha! my gentle queen, |

|

|

170 |

Ne despisies pas mon servise!” |

Do not despise my offering!” |

In his earnestness he exerted himself until, at the end of his strength, he lay exhausted and unconscious on the altar steps. Pleased with his own exhibition, and satisfied that the Virgin was equally pleased, he continued these devotions every day, until at last his constant and singular absence from the regular services attracted the curiosity of a monk, who kept watch on him and reported his eccentric exercise to the Abbot.

The mediaeval monasteries seem to have been gently administered. Indeed, this has been made the chief reproach on them, and the excuse for robbing them for the benefit of a more energetic crown and nobility who tolerated no beggars or idleness but their own; at least, it is safe to say that few well-regulated and economically administered modern charities would have the patience of the Abbot of Clairvaux, who, instead of calling up the weak-minded tombeor and sending him back to the world to earn a living by his profession, went with his informant to the crypt, to see for himself what the strange report meant. We have seen at Chartres what a crypt may be, and how easily one might hide in its shadows while Mass is said at the altars. The Abbot and his informant hid themselves behind a column in the shadow, and watched the whole performance to its end when the exhausted tumbler dropped unconscious and drenched with perspiration on the steps of the altar, with the words: —

|

237 |

“Dame!” fait il, “ne puis plus ore; |

“Lady!” says he, “no more I can, |

|

Mais voire je reviendrai encore.” |

But truly I’ll come back again!” |

You can imagine the dim crypt; the tumbler lying unconscious beneath the image of the Virgin; the Abbot peering out from the shadow of the column, and wondering what sort of discipline he could inflict for this unforeseen infraction of rule; when suddenly, before he could decide what next to do, the vault above the altar, of its own accord, opened: —

|

L’abes esgarde sans atendre |

The Abbot strains his eyes to see, |

|

|

Et vit de la volte descendre |

And, from the vaulting, suddenly, |

|

|

Une dame si gloriouse |

A lady steps,—so glorious,— |

|

|

410 |

Ains nus ne vit si preciouse |

Beyond all thought so precious,— |

|

Nisi ricement conreee, |

Her robes so rich, so nobly worn,— |

|

|

N’onques tant bele ne fu nee. |

So rare the gems the robes adorn,— |

|

|

Ses vesteures sont bien chieres |

As never yet so fair was born. |

|

|

D’or et de precieuses pieres. |

||

|

415 |

Avec li estoient li angle |

Along with her the angels were, |

|

Del ciel amont, et li arcangle, |

Archangels stood beside her there; |

|

|

Qui entor le menestrel vienent, |

Round about the tumbler group |

|

|

Si le solacent et sostienent. |

To give him solace, bring him hope; |

|

|

Quant entor lui Sont arengie |

And when round him in ranks they stood, |

|

|

420 |

S’ot tot son cuer asoagie. |

His whole heart felt its strength renewed |

|

Dont s’aprestent de lui servir |

So they haste to give him aid |

|

|

Por ce qu’ils volrent deservir |

Because their wills are only made |

|

|

La servise que fait la dame |

To serve the service of their Queen, |

|

|

Qui tant est precieuse geme. |

Most precious gem the earth has seen. |

Fig. 37: Glyn Warren Philpot, The Juggler, 1928. Oil on canvas, 51 x 40.5 cm. Collection of Ömer M. Koç.

|

425 |

Et la douce reine france |

And the lady, gentle, true, |

|

Tenoit une touaille blance, |

Holds in her hand a towel new; |

|

|

S’en avente son menestrel |

Fans him with her hand divine |

|

|

Mout doucement devant l’autel. |

Where he lies before the shrine. |

|

|

La franc dame debonnaire |

The kind lady, full of grace, |

|

|

430 |

Le col, le cors, et le viaire |

Fans his neck, his breast, his face! |

|

Li avente por refroidier; |

Fans him herself to give him air! |

|

|

Bien s’entremet de lui aidier; |

Labours, herself, to help him there! |

|

|

La dame bien s’i abandone; |

The lady gives herself to it; |

|

|

Li bons hom garde ne s’en done, |

The poor man takes no heed of it; |

|

|

435 |

Car il ne voit, si ne set mie |

For he knows not and cannot see |

|

Qu’il ait si bele compaignie. |

That he has such fair company. |

Beyond this we need not care to go. If you cannot feel the colour and quality—the union of naïveté and art, the refinement, the infinite delicacy and tenderness—of this little poem, then nothing will matter much to you; and if you can feel it, you can feel, without more assistance, the majesty of Chartres.