10. The Radio Narrator John Booth Nesbitt

© 2022 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0284.26

Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, “The Juggler of Notre Dame” made breathtaking leaps and bounds, much like its humble star, from one form of expression to another. From the narrow confines of scholarship, it infiltrated into the more capacious ambit of verse adaptations, short stories, and prose translations. Eventually it crossed over into the still bigger realm of opera and vaudeville. From the 1920s on, the tale took a further jump by insinuating itself on the airwaves.

Commercial broadcasting furnished an excellent medium for the dissemination of the juggler story to even larger audiences than it had previously reached. The golden age of radio stretched from 1930 through 1955. In this era, broadcasters, advertisers, and listeners displayed an insatiable hunger for entertainment through dramatic plays and narrations. Soap operas, situation comedies, crime dramas, science-fiction shows, and anthology series abounded. Most of those who put together the scripts for such fare cut their teeth on reading books and to a lesser extent on seeing vaudeville, theater, operas, and other live spectacles on stage. A goodly number of them would have encountered Anatole France’s and Jules Massenet’s The Juggler of Notre Dame. Some of these writers, probably fewer, would have chanced upon the original “Our Lady’s Tumbler” in translation. As the decades rolled by, more and more of those active in the industry could have become acquainted with the tale through radio itself.

In Europe of the 1920s and early 1930s, a Jesuit named Remigio Vilariño, who lived from 1865 to 1939, produced a fanciful adaptation for a show that he devised for families. His script was published in Castilian Spanish in 1926 and 1929 before being put into French in 1934. These printings, in two languages no less, constitute convincing evidence that the good priest reached appreciative auditors among devout Catholics on both sides of the Pyrenees. In his adaptation, the leading role is played by a Hungarian jongleur named Georges, who is accompanied by a horse and thirteen-year-old nephew.

In the English-speaking world, the BBC aired a production of Jules Massenet’s opera in May 1929, for which the elaborate lead-up included a printed libretto in translation that listeners could purchase for their convenience. In America, many competing radio versions existed. The one that achieved the broadest currency and left the deepest marks was created by the Canadian-born narrator, announcer, and actor John Nesbitt.

Fig. 46: John Nesbitt, age 46. Photograph, 1956. Photographer unknown.

Within a life that ran from 1910 to 1960, his career extended from the 1920s well into the 1950s. His middle name was Booth, which memorialized his ties to an extended theater dynasty that stretched back to the first half of the nineteenth century. The clan included Nesbitt’s grand-uncles Edwin Booth, the Shakespearean actor, and John Wilkes Booth, younger brother of the preceding, also an actor but better remembered as the assassin of Abraham Lincoln, the American president.

Known on radio first and television later, Nesbitt recounted his “The Juggler of Our Lady” on the air initially in December of 1938 on the Gulf Oil Company radio program. His effort became an overnight sensation, with thousands of requests pouring in for copies of the script. In the following year, the author circulated his text privately among friends as a holiday gift. He also shared his creation with the English-born actor Ronald Colman. For years afterward, listeners became accustomed to dramatic readings of this crowd-pleasing favorite at Christmastime by one or the other of the two. No two performances are word-for-word identical or have the very same accompanying songs, but all of them conform to roughly the same text and musical format.

The impact of Nesbitt’s version was increased thanks to long-play records: his narration of “A Christmas Gift: The Story of the Juggler of Our Lady,” enhanced by choral interludes, was released on vinyl first in 1943. Thereafter it was pressed again repeatedly for more than a decade. Beyond satisfying individual consumers, the recordings served for broadcasts that were transmitted not only domestically in the US but also abroad for the armed forces. The author of an illustrated German reworking of the juggler narrative that was published in 1961 related that he was exposed to the narrative through Nesbitt. In 1942 the tale was reconfigured in a film short entitled The Greatest Gift of All.

In the liner note to the recording, Nesbitt elaborated on the source of his story. This long and fanciful account claims that in 1933, while sifting through an inherited trunk filled with his father’s papers, he came upon “one of the most interesting literary discoveries of modern times.” The find? A supposedly fresh translation that “his father had made from the French, of a folk tale called Le Jongleur de Notre Dame, an ancient legend almost completely unknown to the English-speaking world.” The radio narrator put this version on a par, or so he claimed, with the collection of Hans Christian Andersen. If we take him at his word, he selected the text as his script to follow when he auditioned for a job in radio. Two years later he used it for another tryout, once again successfully.

Despite the apparently detailed provenance, the notes are evasive about the ultimate source. The rendering is “John Nesbitt’s own, adapted from the original translation he found in his father’s trunk, and presented in the clear and simple manner of a storyteller relating an old legend by the fireside on the eve of Christmas. As far as can be determined, the origin of this story is still unknown. It is suspected to be about five hundred years old, but as the story was passed on for so many centuries, nobody knows. It comes from the simple people.” The text explains further that thanks to “Nesbitt’s reintroduction of the forgotten story to America” it has “become part of our own folk lore.” The announcer predicted that “It will someday be as familiar to our children as The Christmas Carol, or Puss in Boots, or The Little Match Girl.” Consistent with this effort to package and market the tale as a folktale, Nesbitt cultivates a style frequent in storytelling, called parataxis, in which he lines up clause after clause and connects them simply by the conjunction “and,” rather than by arranging them in a complex syntax that requires subordination.

The names of the characters belie any claim that the text is not derivative or that it transcribes the oral delivery of a folktale. Either directly or indirectly, the radio personality, his father, or both lifted the tale from Anatole France and Jules Massenet. The names and special talents of the monks are clear giveaways. Notably, Nesbitt commandeers from the French short story the sculptor named Brother Marbod who is covered in dust from his carving. Other aspects reveal an indebtedness, again either directly or indirectly, to the staging of the opera. For instance, the narrator describes, without giving a name, a fat monk who corresponds to Brother Boniface in Massenet. Likewise, Nesbitt focuses on visual features that betray his (or his father’s, if we accept that pretense) familiarity with a theatrical form. Thus at the end he seems to evoke the brightness of a spotlight, a recollection of the artificial illumination that heightened the drama of Massenet’s opera.

Nesbitt’s only substantial change, not that it was original to him, is to set the miracle at Christmas. From early on, the story had been drawn into this season. Despite efforts to associate it with the Marian month of May, its sentimentality accorded better with the winter religious holiday. In addition, Mary’s salience in the action was easier to justify in Protestant communities at Christmas, owing to the Virgin’s central involvement in the nativity. Whatever the causes, Massenet’s opera was often performed around the holiday, especially with Mary Garden in the leading role. The children’s version by Violet Higgins seems to have been retailed at Yuletide, and the poem by Edwin Markham was published in December. These bits of information speak to a pattern that in due course became entrenched.

In the days when the world was young, there lived in France a little man of no importance. Everybody said he didn’t amount to anything, and he firmly believed this himself. For he was just a traveling circus performer, a juggler. He couldn’t read or write and all he knew how to do was to go about from town to town, following the little country fairs, doing his tricks for the children, and earning a few pennies a day. His first name was Barnaby, but he was too unimportant to have any last name at all.

Now when it was summer time, and the weather was sunny and beautiful, and the people were strolling around the streets, and the young lovers were holding tightly to each other’s hands in the park, then Barnaby would be happy, because he could find a clear place in the village square, spread out a strip of old carpet on the cobblestones, and on the carpet he would perform his tricks for the children and grown-ups alike.

And Barnaby, although he knew he was a man of no importance, was a wonderful juggler. You wouldn’t believe half the things he could do. At first he would only balance a tin pie plate on the tip of his nose. But when the crowd had collected, he would stand on his head and juggle six golden-colored balls in the air at the same time, catching them with his feet. And sometimes he could actually stand on his head and juggle twelve sharp knives instead of the golden balls and catch the knives with his feet too. And then the people would applaud and the children jump up and down with delight, and a whole rain of pennies would be thrown down onto Barnaby’s carpet. And at the end of a day’s work like this, Barnaby would collect the pennies in his hat and, before wearily resting his aching muscles, he would kneel down on his carpet and reverently thank God for the hat full of pennies. And always the people would laugh at his simplicity, and everybody would agree that Barnaby would never amount to anything.

But all this is about the happy days in his life, the summer days when the sun was shining and people were willing to toss a penny to a poor juggler. Well, when winter came, then Barnaby could afford no place to sleep, and he had to wrap up his juggling equipment in the old carpet and trudge along the muddy roads, begging a chance to sleep a night in a farmer’s barn or doing his tricks for some rich person’s servants in order to be given a meal. And Barnaby of course being so simple, never thought of complaining, for he knew that the winter and the rains were as necessary as the spring and the summer. And as he plodded along, he would say to himself, “How could such an ignorant fellow as me ever hope for anything better?”

[Choir] Now one year in France there was a terrible winter, and on an evening in early November at the end of a dreary wet day, as Barnaby trudged along a country road, sad and bent, with the raindrops running down his face and off the end of his nose, carrying under his arm the golden balls and knives in the old carpet, he saw something moving in the mist ahead of him. As he got closer, he saw that it was a fine fat white mule and on top of the mule was a fine fat monk, dressed in warm clothes and singing to himself as he rode along. When the monk saw poor muddy Barnaby, he smiled at him and called out, “It’s going to be a cold evening. How would you like to come and spend the night where I live, at the monastery?” “Oh!” cried Barnaby, running in the mud alongside of the mule. “If I only could! But will they let an ignorant fellow like me enter such a holy place as a monastery?” And the monk laughed, “Of course, friend! For aren’t we all ignorant as jackasses when we compare ourselves to the Lord?” And the monk pulled Barnaby up behind him on the mule, and Barnaby had to hold both his arms around the monk’s fat middle in order to stay on. And both of them began laughing again as they rode down the road.

And that night, Barnaby found himself seated at the table in the huge dining room of the monastery. It was blazing with candles and silver candlesticks, and the table was covered with enormous roasts of fine rare beef, and legs of mutton swimming in gravy, and whole roast pigs with red apples in their mouths, and chicken pies and big cakes covered with crushed almonds, and all the fresh apple cider you could drink.

Although Barnaby, of course, sat down at the very foot of the table, together with the servants and the beggars. He looked around with the candlelight shining in his eyes, and he thought he’d never seen such a wonderful sight this side of heaven. And suddenly, trembling with excitement, he jumped up, ran around the table to where the lord abbot who was head of the monastery sat at the top, and Barnaby sank down to his knees.

“Father, grant my prayer: please let me stay here! I can’t ever hope to become a holy man: I’m too ignorant. But let me work in the stable, and mop the kitchen floor, and just stay.” And the fat jolly monk who’d met Barnaby turned to the head of the monastery, “This is a good man. He’s simple and pure of heart.” And so the abbot nodded his head. And that night Barnaby was given a cell of his own to sleep in, and he put his juggling equipment under the cot, and before he fell asleep, he promised solemnly that he would never again go back to his old profession of juggling six golden balls and twelve sharp knives.

[Choir: “The First Noel”] In the days that followed, everybody smiled to watch Barnaby work. He would scrub the flagstones of the kitchen floor, and polish the big copper kettles, and with his strong acrobat’s muscles knotting under the strain, he would willingly carry huge bundles of fodder to the cattle. And when the chapel bells rang out for services, he would creep humbly in by the side door and kneel down in a dark corner of the rear.

And all through those early days, his face shone with happiness from morning until night—until two weeks before Christmas. And then a bewildered expression began to appear upon his simple face, and slowly his joy turned to misery and despair. For all around him he saw every monk, busy preparing a wonderful gift to place in the chapel on Christmas Day. There was Brother Maurice who was a painter, who would take gold and silver and rare enamels and paint exquisite little miniature pictures on the corner of each page of a Bible. And then there was Brother Marbod who was a sculptor and who was finishing a beautiful statue of Christ. This artist spent all of his hours in chiseling stone, so that his beard and his eyebrows and his hair were always white with stone dust. And there was Brother Ambrose who was writing a new hymn to be sung at the Christmas service, and Brother Joseph who was composing the music for it. Everywhere Barnaby went were these educated, trained men following their work, each one of them making a beautiful gift to dedicate to God on Christmas. And what about Barnaby? He could do nothing. He would go to his tiny cell and unwrap his juggling equipment and look at it sadly. “I’m but a rough man, unskilled in art. I can’t read or write. All I know how to do is to perform a few tricks. Alas, everybody has a gift to give except me.”

Christmas morning came at last. And strangely enough, it was the first day in that bitter winter that the sun broke out and shone brilliantly. And the great stone halls were decked out in pine branches and red holly berries. Thousands of candles gleamed everywhere, and all of the buildings rang with music and songs. It took twenty-five of the monks to roll Brother Marbod’s big new statue into the chapel, and then the choir sang the new song that had been written by Brother Ambrose, and then the beautiful Bible with the paintings of Brother Maurice was placed before the altar, and every brother went forward to present his gift to God. But Barnaby had disappeared.

Now a strange and terrible thing happened that no brother in the great monastery would ever forget during all the days of his life. For that evening, after the visitors had gone home and the chapel was deserted and nearly all the brothers were resting on their hard beds, the plump jolly monk who had brought Barnaby to the monastery went running down the halls, with his face white as a ghost’s. He pounded over the stone floors to the private room of the abbot. He shoved open the door without knocking, and panting with excitement he seized the abbot by the arm. “Father, a frightful thing is happening, the most terrible sacrilege ever to take place is going on right in our own chapel. Come with me!” Without speaking a word, the abbot joined him, and the two elderly men ran down the corridors, burst through a door, and came out on the choir balcony at the rear of the chapel. The monk pointed a trembling finger down toward the altar. The abbot looked, turned ashen in color. “God forgive him! He has gone mad.”

[Choir: “Ave Maria.”] Down below, squarely in front of the altar, was Barnaby. He had spread out his old strip of carpet and, kneeling reverently on one knee, was juggling in the air six golden balls. He was presenting his old act—the bright knives, the shining balls, and at the very tip of his nose was balanced a tin pie plate, and on his face was a look of adoration and joy.

“We must seize him and drag him away!” cried the abbot. And the two men turned toward the door, but at that exact moment a dazzling light suddenly filled the chapel, a brilliant beam coming directly from the altar. And both the monks sank to their knees. For as Barnaby had finished his juggling act and knelt exhausted on his carpet, they saw the statue of the Virgin Mary move.

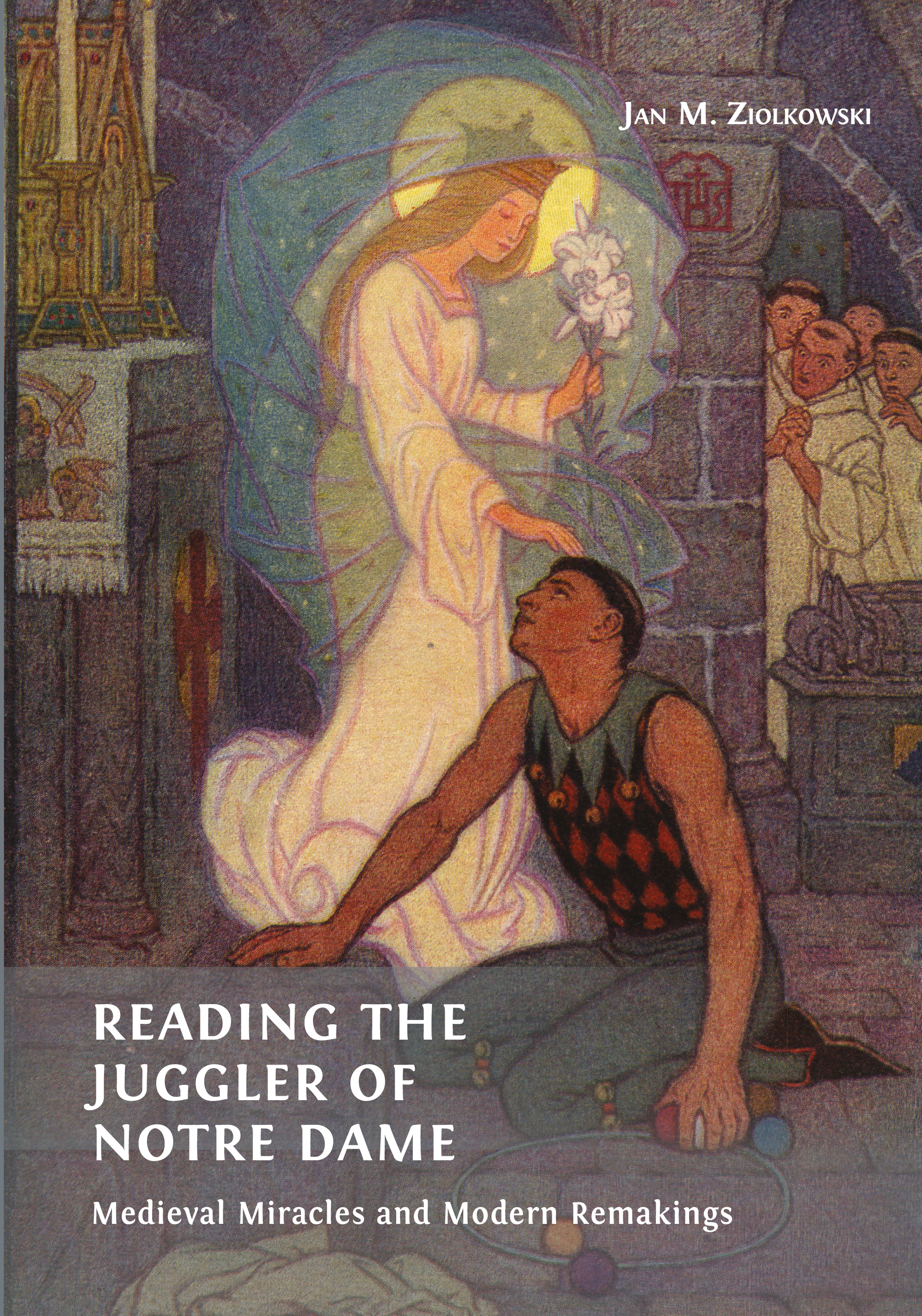

Fig. 47: The Virgin descends to bless the juggler. Illustration by Maurice Lalau, 1924. Published in Anatole France, Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame (Paris: A. & F. Ferroud, 1924), p. 23.

She came down from her pedestal and, coming to where Barnaby knelt, she reached down and took the blue hem of her robe and touched it to his forehead, gently drying the beads of sweat that glistened there. And the light dimmed, and up in the choir balcony, the monk looked at the abbot. “God has accepted the only Christmas present he had to give,” and the abbot slowly nodded, “Blessed are the simple in heart, but they also shall see God.” [Choir: “Ave Maria.”]