5. The Jongleur and the Black Virgin of Rocamadour

© 2022 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0284.05

Rocamadour, a community in southern France, stands between Quercy and Périgord, in the diocese of Cahors. Perched high in a ravine above the river Alzou, the town serves as a way station for pilgrimage on the celebrated Camino de Santiago. “Saint Iago,” to break the last word into its two elements, shortens the Spanish equivalent to the Latin Sanctus Iacobus. The name, originally Hebrew and then Greek, gave English both Jacob and James. The “Way of Saint James,” to translate the Spanish phrase fully, designates a network of routes by which pilgrims travel from all points of the compass to the northwest of the Iberian peninsula, with the ultimate goal of reaching the shrine of the apostle Saint James the Great in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, twenty-two miles east of the Atlantic Ocean.

Since the Middle Ages the French municipality of Rocamadour has been renowned for having one of the most celebrated Marian sanctuaries in Europe and even in the world, to which visitors gain access by clambering up more than two hundred steps carved into the rock cliff. Already in antiquity the epicenter of a pagan cult, the location acquired luster from a local hermit named Amadour, after whom it is supposedly called: Roc-Amadour or “Cliff Amadour.” The alleged background of the holy man varies from version to version of his life. One account maintains that he spent most of his existence as Zacchaeus, the chief tax-collector at Jericho who is mentioned in the Gospel of Luke. After changing his identity, he is said to have voyaged from the Holy Land and to have founded in honor of Mary a house of worship that is now named after him.

The main claim to fame of the church has been a wooden statue of the Virgin that the holy man purportedly hewed himself. The carving belongs to the type known in English as “Throne of Wisdom,” because of the position in which the two figures are placed. In such likenesses, Mary is enthroned with her child on her lap. But the orientation of the Mother and Child in the representation is not what has elicited the most attention from visitors across the ages.

The image is a so-called Black Madonna or Black Virgin, representing the Mother of God with the infant Jesus, both of them very dark in coloration.

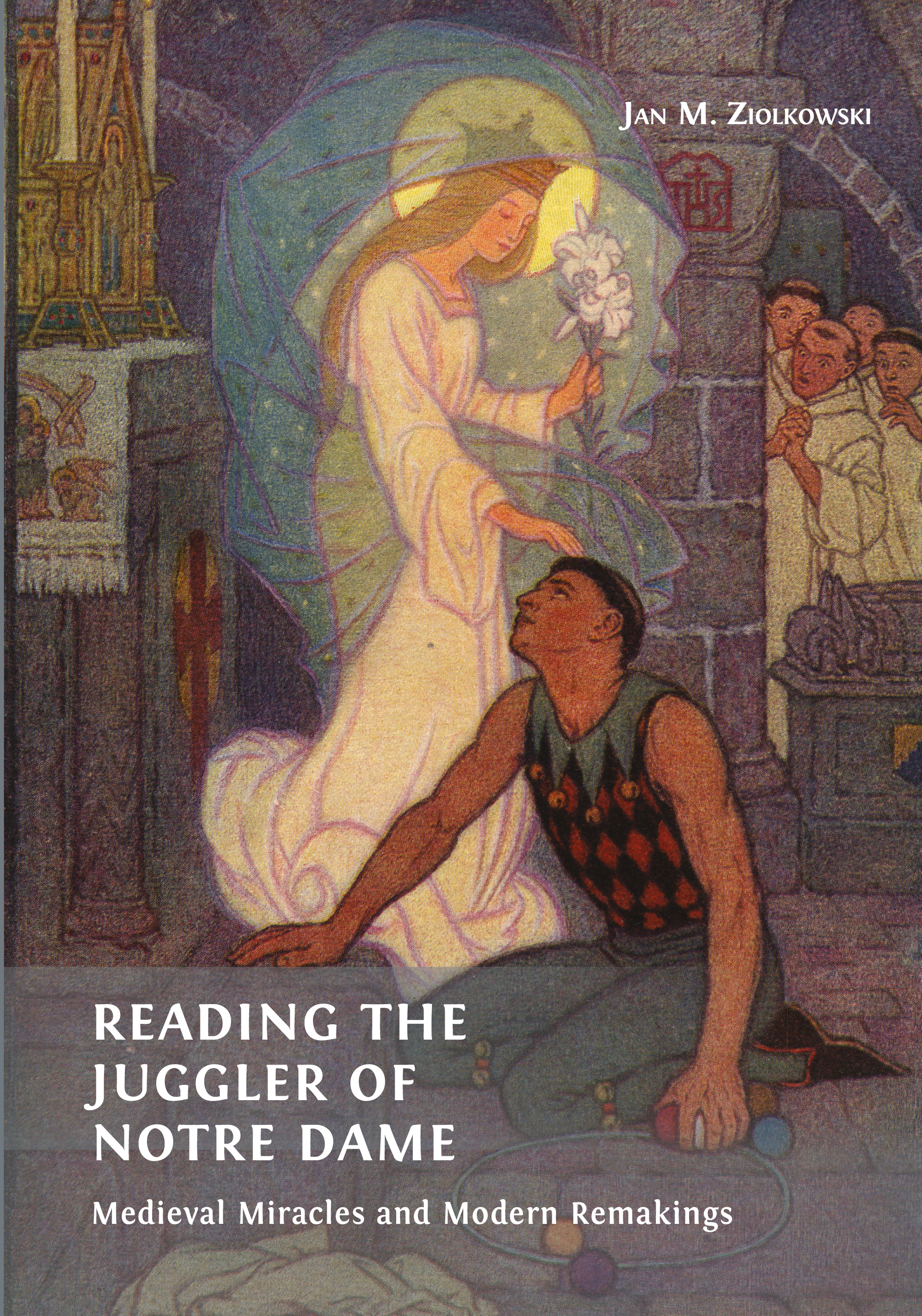

Fig. 7: The Black Madonna of Rocamadour. Photograph by Martin Irvine, no date. Image courtesy of Martin Irvine. All rights reserved.

Statues and paintings of this kind have fascinated viewers and generated much speculation across the centuries, with considerable curiosity about the reasons for the blackness. Sometimes they have darkened with time, from the natural aging of woods and paints, the effects of smoke and soot, or both; but in other instances they were crafted of substances that must have been black by nature from the beginning. In certain cases they may have been imported from outside Europe. Such circumstances have left researchers wondering which if any of these artworks were intended to represent black people and which acquired the color fortuitously.

The site of Rocamadour belonged to the Benedictine abbey of Tulle, which was located 55 miles away. In 1166 the leader of the latter, Abbot Gerald of Escorailles, commissioned a notary, presumably one of the monks, to compile the stories of wonders that had been bestowed on those who sought Mary’s intercession by venerating the Black Virgin. The anonymous compiler claims explicitly to recount only those miracles that he had witnessed with his own eyes or that he had heard from reliable parties. Of course, this assertion must be taken with a hefty grain of salt: fact-checking was anything but the norm in the Middle Ages.

The resultant three-book text, entitled The Miracles of Our Lady of Rocamadour, edifies its readers with 126 extraordinary events. The first and second books, written in unpretentious Latin prose, have been dated to 1172, the third to 1173. Because the initial miracle was reported only in 1148, the dating furnishes vivid evidence of the rapidity with which the local cult took shape.

Among the reports bundled up in this collection is the first attestation of a shrine wonder about a musical performer and a candle that subsequently received treatment in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century from Gautier de Coinci. The medieval French poet, a Benedictine monk who eventually became a grand prior, credits the Latin of The Miracles of Our Lady of Rocamadour explicitly as his source. Later, King Alfonso the Wise renders the story into Galician-Portuguese verse in his songs that celebrate miracles of the Virgin.

The marvel revolves around a jongleur called Peter Iverni of Sieglar. The second component in his name has been construed as the genitive for a Latin noun of the second declension, here suffixed to the German personal name Ivern. To put all this more plainly, the implication is that Peter was son of Ivern. The final element denotes the Rhineland community of Sieglar, today a neighborhood in Troisdorf. The last-mentioned German city is situated not far from Siegburg, in the district of Bonn and in the diocese of Cologne.

However the full appellation of this Peter is parsed and decoded, the incidents that bring him into conjunction with the Virgin Mary play out not in Germany but in France, in the commune of Rocamadour. The presence at the French shrine of a professional from the upper Rhine should not surprise us. In the stretch between 1166 and 1172, both lay people (merchants, above all) and churchmen from the Cologne Lowland made pilgrimages to Rocamadour or at least took vows to undertake them. These journeys had impacts on both locales that likely contributed to the specificity of the place with which the musician is identified in this narrative.

Then again, the writer of this account takes pains to indicate indirectly that the episode took place significantly before 1172–1173: he specifies that the key actor had experienced the miraculous reward long ago, had commemorated it annually for a lengthy but indeterminate period since it happened, and had died, all well before the gestation of The Miracles of Our Lady of Rocamadour.

According to the legend, Peter Iverni of Sieglar played his viol and performed his best songs in honor of the Virgin before the wooden statue of her that stood in the basilica of Saint Mary. In return, he petitioned her before that same Madonna, if his entertainment pleased her, to give him one of her candles or at least a chunk of wax from it. Three times the taper descended upon his instrument. The miracle prompted the wonderment of the pilgrims who thronged around him, but by the same token it incurred the indignation of the sexton. Enraged, this officious Gerard twice took away the votive but had to give up when it alighted on the viol for the third time.

Fig. 8: A taper miraculously alights upon a jongleur’s viol, prompting wonder from bystanders. Illustration by Pio Santini, 1946. Published in Jérôme and Jean Tharaud, Les contes de la Vierge (Paris: Société d’éditions littéraires françaises, 1946), between pp. 130 and 131.

Thereafter Peter returned annually to the sanctuary to offer to the Mother of God a candle of more than a pound’s weight.

The physical things that play such important roles in the story deserve a moment of consideration. First comes the medieval viol, a protoviola or -violin. Its name is cognate with vielle and, far more familiar in English, fiddle. The instrument, used widely in western Europe, was a bowed and stringed instrument, with three to five gut strings, a leaf-shaped pegbox with frontal tuning pegs, a low and flat bridge, and a waist that curved slightly inward, sometimes resulting in an overall body shaped like a figure eight. It was sounded most often with the bottom of its lower bout resting on the shoulder of the instrumentalist.

Second, the chapter title of the miracle features the unusual and somewhat ungainly Latin expression cereus modulus or “waxen form” to describe the candle or object made of beeswax that alights upon Peter’s instrument. In the text proper, the nameless author of The Miracles of Our Lady of Rocamadour employs the noun modulus unmodified by the adjective five times. Modulus, if not a hapax legomenon (a term attested only once), was at least a rarity for denoting anything made of wax. Later versions of the legend in both literature and representational art depict the item invariably as a taper, mostly as a lighted one, but this writer gives no hint that whatever he has in mind is illuminated or indeed even a candle.

The word directs attention instead, without divulging any details, to the fact that the wax is shaped or, to use a cognate, “modeled.” As the last translation suggests, modulus is related etymologically to the French noun moule for a mold or form. In an analogous development, the Latin formaticum, with “form” at its basis, gave rise to the modern fromage for cheese. At some point, in a common occurrence familiar to linguists as metathesis, the consonants d and l in modulus and the letters or in formaticum were flipflopped, and voilà! the present-day English and French words emerged.

The term modulus could designate a block of wax, a candle in a special shape, a large or small taper, or something else. To concentrate for a moment on votives, offerings could have been made that resembled an afflicted or healed body part. When Peter himself refers to “wax forms that hang,” a wick could be implied. For instance, he could have in mind two candles that shared such a cord, as happens often in candle making. By being joined in this way and left uncut, a pair could have been draped over a peg or suspended from another sort of hanger.

The emphasis on the physicality of the material is amplified in the conclusion to the story, where the Latin libra does not denote a pound as a monetary value but rather as a weight. The author specifies further that Peter committed to depositing this amount of beeswax as an annual tribute. The spelling of the Latin trecensus, with an initial element that suggests the number three, tempts the translator to use the English “threefold payment,” but the term is encountered in dictionaries first under transcensus and only secondarily with the other spelling. Such payments have been interpreted as a yearly fee that membership in the confraternity of Rocamadour required. In this case, they would be a type of insurance that distributed the costs and risks of pilgrimage across a large group. Alternatively, they could have been expressions of individual devotion to the Virgin as she was embodied in one shrine that held special significance to them.

What light can this episode shed on “Our Lady’s Tumbler”? What relationships can we hypothesize between the two stories, and what could have motivated the differences between them? Some similarities are obvious. An entertainer expresses devotion to the Virgin by performing before an image of her. A church authority, not terribly high in the hierarchy but wielding power all the same, takes exception to the performer and denies the miracle. For all that, the jongleur is vindicated in the end.

Among many dissimilarities, “The Jongleur of Rocamadour” depicts no retreat from the world, no monastery, no class contrast between the professional and the monks, and no saintly death. Rather, it concludes by focusing upon a yearly gift made by the jongleur to a specific shrine. Additionally, it furnishes the particular of names for both the protagonist and antagonist, Peter Iverni the jongleur and Gerard the sexton, whereas “Our Lady’s Tumbler” is resolutely indeterminate except for the detail of its setting in Clairvaux.

“Our Lady’s Tumbler” calls attention to the narrative form called exemplum. This genre is a nod to preaching. The sermonizing could have taken place outside monasteries, for instance in or near cathedrals, where Cistercians such as Bernard of Clairvaux sought recruits to their cause. Alternatively, the story could have been used to good effect in homilies within the chapter houses of the abbeys. What better means could have been devised for coaching choir monks to treat their lay confreres fairly?

The tale connected with the Black Virgin of Rocamadour conjures up very different social settings and messaging, without the faintest whiff of monasticism. In the late fourteenth century, the English writer Geoffrey Chaucer composed The Canterbury Tales. In verse and prose, he regaled his readers with stories that are purportedly told in a contest by pilgrims as they wend their way from London to Canterbury. Already two centuries earlier, we can readily picture similar travelers on the Continent who are entertained by jongleurs. Going further, we can imagine entertainers singing to them of miracles that celebrate stopping places on pilgrimages. The great routes often had among their multiple destinations cathedrals where the Virgin Mary revealed herself and caused wonders on behalf of her petitioners. Accounts in which jongleurs were cast as central characters would have held a special appeal to these professionals, making such stories natural choices for inclusion in their repertoires.

A. The Miracles of Our Lady of Rocamadour: “On the Wax Form That Came Down upon a Viol”

Peter Iverni from Sieglar sought his sustenance by playing instruments. According to his habit, he would come to churches and, after pouring forth prayer to the Lord, he would touch the strings of the viol and render praises to the Lord.

Once he was in the basilica of the Blessed Mary of Rocamadour. For a long time he had been giving no rest to the strings while intoning, but harmonizing sometimes with the instrument in the notes he sung, when he looked up: “Lady,” he said, “if my tuneful songs please you or your son, my Lord, take down any one you wish from the innumerable and inestimable wax forms that hang here and bestow it upon me.” While singing in this way, he was praying, and while praying, he was singing, one form came down upon his instrument, as those who were present saw.

But the monk Gerard, sexton of the church, asserting that he was a magician and sorcerer, took back the form with indignation and put it back where it had been. Yet Peter, reckoning it the work of God, suffered patiently and did not cease making music. Lo and behold, the form that had been on the instrument previously was put down on it a second time. But the monk, unwilling to endure his anger, took back the same object and put it back fastened more securely.

As is to be expected, the Lord, whose essence it is to be constant always and not to vary on different occasions, performed a third time an act similar to what he had done twice already. As all those who were present saw, “wonder at that which happened to him” took hold of them. Praising the Lord together, they raised their voices to the heavens. He likewise, crying aloud for joy, returned to its giver the wax form that had been given him by God, praising him “with timbrel and choir, with strings and organs.”

To honor and praise the Lord’s name, he became accustomed to render in memory of the miracle every year as long as he lived a wax form, supplementing it further by a pound, as annual payment to the magnificent Virgin of Rocamadour.

B. Gautier de Coinci, The Miracles of Our Lady: “Of the Candle that Came Down to the Jongleur”

The next major iteration of the miracle owes to the Benedictine monk Gautier de Coinci. This medieval French poet, thought to have issued from lordly stock, was born in 1177, probably in Coinci-l’Abbaye. This village was located between Soissons and Château-Thierry, in the region known after its principal city as Soissonnais. He joined the Benedictine monastery of Saint Médard in Soissons in 1193 at age 16 and entered the priesthood at age 23. In 1214 at age 37 he took office as prior of Vic-sur-Aisne, a dependency of Soissons located ten miles away. In 1233 he returned to his home institution as grand prior, in which capacity he served until dying in 1236 at age 59.

Despite the administrative burdens he bore, Gautier composed religious songs, sermons, and saints’ lives. He was also a skilled musician. Where he acquired his knowledge and skill remains unknown, but it would be reasonable to hypothesize that he studied for a spell in Paris. Whatever the case may be with his education, his magnum opus is the Miracles de Nostre Dame or The Miracles of Our Lady. He began the first book in 1218, wrote the second between 1223 and 1227, and revised the first intermittently. The two books comprise fifty-eight narratives and eighteen lyrics, for a total of approximately 35,500 octosyllabic lines.

His oeuvre has commanded admiration for its narrative and lyric skill, virtuoso versification, exuberant vocabulary and wordplay, resolute moralism, and social satire, but above all for the range and intensity of the devotion to the Virgin Mary that it displays. These qualities secured strong success for the poet’s Marian miracles in the Middle Ages, most readily gauged by the 114 manuscripts still extant that transmit the poetry in whole or part.

For many of the legends, Gautier credits as his source a Latin manuscript, no longer extant. In the case of the narrative about the jongleur in Rocamadour, he commences with a six-line prologue in which he points out that miracles of the Virgin of Rocamadour are numerous, that “a very large book” has been made to record them, and that he intends to retell one he finds attractive. By these remarks he acknowledges the Latin account given in The Miracles of Our Lady of Rocamadour. He caps his narrative with an extended commentary in which he gives credit to the jongleur protagonist for his sincere faith in performing the songs: clerics would do well to follow heed, by bringing their hearts and mouths into accord as they fulfill their liturgical duties.

|

The sweet mother of the creator |

|

|

performs so many miracles, so many lofty deeds, |

|

|

at her church of Rocamadour, |

|

|

that a very large book has been made of them. |

|

|

5 |

I have read it many times. |

|

In it I found a very fine miracle |

|

|

of a jongleur, a layman, |

|

|

that I wish to relate, if I can, |

|

|

so as to make understandable to anyone |

|

|

10 |

the refinement of Our Lady. |

|

In that land a jongleur lived |

|

|

who would sing very willingly |

|

|

the lay of the savior’s mother |

|

|

when he came through her sanctuaries. |

|

|

15 |

He was a minstrel of great renown, |

|

who was named Peter of Sieglar. |

|

|

He went on pilgrimage |

|

|

to Rocamadour, it seems to me, |

|

|

where great crowds often gather. |

|

|

20 |

There he found many pilgrims |

|

who were from distant lands |

|

|

and who were celebrating very greatly. |

|

|

When he had said and done his prayer, |

|

|

he grabbed his viol and drew it to him. |

|

|

25 |

He makes the bow touch the strings |

|

and makes the viol resound |

|

|

so that without any delay |

|

|

everyone gathers round, cleric and lay. |

|

|

When Peter sees that everyone is heeding him |

|

|

30 |

and everyone is lending him their ears, |

|

it seems truly that he plays so well |

|

|

that his viol is poised to speak. |

|

|

When he had greeted sweetly and praised at great length |

|

|

35 |

wholeheartedly the Mother of God, |

|

and bowed down greatly before her image, |

|

|

he said very loudly and cried out, |

|

|

“Ah, Mother of the king who created all, |

|

|

40 |

if anything that I say has pleased you, |

|

I ask of you in return |

|

|

that you make me a gift of one of these candles |

|

|

of which there are so many around you up there |

|

|

that I have never seen more, far or near. |

|

|

45 |

Lady without equal and without peer, |

|

send me one of your lovely candles |

|

|

for celebrating at my dinner. |

|

|

I do not ask of you more, if God guides me.” |

|

|

Our Lady, saint Mary, |

|

|

50 |

who is a fountain of refinement |

|

and is the source and channel of sweetness, |

|

|

heard well the voice of the minstrel, |

|

|

for now, without waiting further, |

|

|

she causes to come down on his viol |

|

|

55 |

quite overtly, in the sight of the people, |

|

a very lovely and fair candle. |

|

|

A monk who had the name Gerard, |

|

|

who was very wicked and wild, |

|

|

who now guarded the sanctuary |

|

|

60 |

and who watched over things, |

|

took the miracle for a folly, |

|

|

as a man full of black bile would. |

|

|

He said to Peter that he was a magician, |

|

|

thief, and enchanter. |

|

|

65 |

He takes the candle in his hands, |

|

he puts it back and hangs it high up. |

|

|

The minstrel, who knew a good deal, |

|

|

sees the monk as being obstinate and stupid, |

|

|

does not put his own sense on the level with his, |

|

|

70 |

for he understands and perceives well |

|

that Our Lady has heard him. |

|

|

From this he has a heart so rejoicing |

|

|

that he shed tears and weeps for joy. |

|

|

He prays often to the Mother of God |

|

|

75 |

and thanks her much within his heart |

|

for her very great refinement. |

|

|

He takes up the viol once more, |

|

|

lifts his face toward the image, |

|

|

sings and fiddles so well |

|

|

80 |

that there is neither a sequence nor a kyrie eleison |

|

that you would hear more willingly, |

|

|

and the candle, lovely and intact, |

|

|

comes back down again on the viol. |

|

|

Five hundred saw this miracle. |

|

|

85 |

The treacherous monk, the crazy one |

|

who has his head full of relics, |

|

|

when he again sees his candle come down, |

|

|

rushes forward among the people and the crowd, |

|

|

faster than a stag, doe, or fawn. |

|

|

90 |

He is so angry, he is so upset, |

|

that he can hardly say a single word. |

|

|

With great irritation and great anger, |

|

|

he pulls his hood back, |

|

|

and, like one who does not have even a bit of sense, |

|

|

95 |

tells the minstrel to understand well |

|

that he will not at all have his candle. |

|

|

He marvels very much at what he sees |

|

|

and holds it very much for a great marvel. |

|

|

He never saw in his life, |

|

|

100 |

he says, such great magic. |

|

He claims over and over |

|

|

that the minstrel, the jongleur, is a magician. |

|

|

Vexed and fired up with anger, |

|

|

he took the candle again in his hands, |

|

|

105 |

angrily climbs up above again, |

|

puts it back very firmly, |

|

|

and ties it well and secures it well. |

|

|

He says to the minstrel to understand well |

|

|

that Simon Magus the magician |

|

|

110 |

was not such an enchanter |

|

as he will be if ever he makes it |

|

|

come down from up there. |

|

|

The minstrel, to give the gist of it, |

|

|

who had seen both near and far |

|

|

115 |

many foolish and many wise men, |

|

is not in the slightest stirred up by all this. |

|

|

He endures patiently |

|

|

the monk’s stubbornness and impatience. |

|

|

He is so even-tempered that he does not |

|

|

120 |

on any account take to heart anything |

|

of what the treacherous monk says, |

|

|

but begins once more |

|

|

his song and melody. |

|

|

He knows well that Our Lady |

|

|

125 |

will prevail in this matter very well |

|

if his songs are fit to please her. |

|

|

In fiddling he sighs and weeps, |

|

|

his mouth sings and his heart prays. |

|

|

He prays sweetly to the Mother of God |

|

|

130 |

that in her sweetness she again hearken to him |

|

and, to make the miracle even more evident, |

|

|

again make the lovely candle |

|

|

return at least once |

|

|

that the monk, like a man in fury, |

|

|

135 |

who is a fool and an illiterate, |

|

foolishly snatched |

|

|

twice from his hands. |

|

|

Around him there are great throngs of people, |

|

|

who are stunned and stirred |

|

|

140 |

by the miracles that they have seen. |

|

Everyone marvels, everyone makes the sign of the cross, |

|

|

with their fingers they point out to one another the candle |

|

|

that has come down already twice. |

|

|

Peter does not have his fingers |

|

|

145 |

asleep or numbed on the viol, |

|

but sings and fiddles so well |

|

|

before the image of Our Lady |

|

|

that he makes many a soul weep for tenderness. |

|

|

Whatever sound the viol produces, |

|

|

150 |

the heart sings and fiddles so loud |

|

that the sound goes off from it all the way to God. |

|

|

For now, as we read, |

|

|

the candle again makes the third leap |

|

|

to the minstrel, to whom God gives aid. |

|

|

155 |

Three times the lady held it out to him, |

|

who understood it better than the monk |

|

|

and who is more refined |

|

|

than the treacherous monk, who |

|

|

is astonished and stunned by the noise. |

|

|

160 |

Everyone cries out, “Play, play! |

|

A lovelier miracle never happened |

|

|

nor will ever take place again, believe you me!” |

|

|

Throughout the sanctuary they make so great a celebration, |

|

|

both clerics and laypeople, men and women, |

|

|

165 |

and go about sounding so many bells, |

|

you would not hear even God thundering. |

|

|

Who then had seen the minstrel |

|

|

offering the candle on the altar, |

|

|

to thank God and Our Lady, |

|

|

170 |

would have a hard heart, by the faith that you owe my soul, |

|

if not moved by compassion. |

|

|

He was not foolish or worthless; |

|

|

on the contrary, he was refined, worthy, and wise, |

|

|

because, as long as his life lasted, |

|

|

175 |

every year, as I find it in the book, |

|

he brought to Rocamadour |

|

|

a very lovely candle of a pound’s weight. |

|

|

So long as he lived, |

|

|

he enjoyed serving God in such manner |

|

|

180 |

that he never entered any church afterward |

|

without immediately fiddling |

|

|

a song or lay of Our Lady, |

|

|

and when it pleased God that he came to his end, |

|

|

he reached the glory of heaven |

|

|

185 |

and his soul went off before God |

|

thanks to the prayer of Our Lady, |

|

|

of whom he would sing so willingly |

|

|

and to whom each year at Rocamadour |

|

|

he was donor of a candle. |

|

|

Of Those Who Sing and Read and |

|

|

Do Not Think at All about What They Say |

|

|

190 |

We priests, we cantors, |

|

we clerics, we monks, we friars, |

|

|

if we have understood well |

|

|

this miracle that I have related, |

|

|

we must sing night and day, |

|

|

195 |

devoutly, loudly, and deliberately, |

|

of the lady who brings to the respite |

|

|

of heaven all those |

|

|

who put effort into serving her. |

|

|

But I certainly see many of them |

|

|

200 |

who are weak and lazy. |

|

It does not matter to many to serve God. |

|

|

There are many who do not make what they perform |

|

|

in any fashion hot or cold to God: |

|

|

they screech much and they cry much |

|

|

205 |

and they stretch their throats much, |

|

but they do not stretch out |

|

|

or pull well the strings of their viols. |

|

|

By this they much worsen their singing. |

|

|

The mouth lies to God and is in discord |

|

|

210 |

if the heart is not in concord with it. |

|

God wishes the concord of the two. |

|

|

If the heart gambols, springs, and dances, |

|

|

looks around and thinks of foolish pleasure, |

|

|

neither God nor his mother take any pleasure |

|

|

215 |

in the mouth, if it makes notes, |

|

no more than in a donkey if it brays. |

|

|

God is not very much concerned about |

|

|

singing or trilling |

|

|

220 |

but, when the mouth really exerts itself, |

|

the heart must strengthen itself |

|

|

and reinforce the strings |

|

|

of the viol and extend them |

|

|

so that without waiting anymore, the bright sound |

|

|

225 |

goes off at the first word and soars |

|

up above into paradise. |

|

|

Then their song is lovely to God. |

|

|

But many have such a viol |

|

|

that is put out of accord both early and late |

|

|

230 |

if it is not tuned with strong wine. |

|

Whatever the heart thinks or says, |

|

|

truly a melody will not issue |

|

|

from the mouth until it has been refreshed; |

|

|

but when the wine has cured it |

|

|

235 |

and mulled wine has stunned the head, |

|

then they sing and celebrate greatly |

|

|

and rouse a whole monastery. |

|

|

I know someone who often has |

|

|

a sickly voice, feeble and weakened, |

|

|

240 |

if strong wine does not heal it; |

|

but when good wine strengthens it nicely |

|

|

and the son of the crooked has struck it, |

|

|

then it sings loud and then it rejoices. |

|

|

Good wine but not beer does this: |

|

|

245 |

such song is not at all lovely, |

|

God does not listen to such a viol, |

|

|

for when drunkenness pulls the bow, |

|

|

God has a small share there. |

|

|

When wine touches the strings, |

|

|

250 |

the whole song is full of discords. |

|

When wine rouses the heart, |

|

|

God cannot hear the mouth; |

|

|

God on no account hears the mouth |

|

|

255 |

It is fitting for the stream to spring up from the heart |

|

that causes the voice to please God. |

|

|

God and his mother are not concerned |

|

|

about a loud voice or a clear voice. |

|

|

Some sing low and simply, |

|

|

260 |

to whom God listens more tenderly |

|

than he does to one who gives himself airs and graces |

|

|

when he loudly sings—and loudly in five parts. |

|

|

God sets no stock by |

|

|

a clear voice, pleasing and lovely, |

|

|

265 |

the sound of the harp and of the viol, |

|

if there is no devotion in the heart. |

|

|

God pays heed to the intention, |

|

|

not the voice nor the instrument. |

|

|

270 |

He who wishes to praise God tenderly, |

|

praises him as David did: |

|

|

his heart was wholly rapt to heaven |

|

|

when he praised God on his harp. |

|

|

That one sings, fiddles, and harps well |

|

|

275 |

who adores and prays to him in his heart |

|

while the harp or the voice cries out. |

|

|

And he who harps should watch out well |

|

|

to keep his hand on the harp: |

|

|

the hand signifies the craft. |

|

|

280 |

When a man leads a good life, |

|

in that case he harps and sings so well |

|

|

as to enchant the devils, |

|

|

just as David enchanted them |

|

|

when he played the harp for King Saul. |

|

|

285 |

There are plenty of good singers, |

|

good clerics, and good preachers, |

|

|

who preach and shout out in great quantity, |

|

|

but do nothing of what they say. |

|

|

He who sings and harps in this way |

|

|

290 |

does not have his hand at all on the harp, |

|

and neither his harp nor his fiddle |

|

|

is pleasing or lovely to God. |

|

|

He who pronounces and counsels something well, |

|

|

if he does not do it, he is truly idiotic. |

|

|

295 |

His wits are not worth an old nothing, |

|

because the opposite of his wit is ignorance. |

|

|

Let us not be such minstrels. |

|

|

Let us do it well (there is none of that sort), |

|

|

and then afterward let us teach it. |

|

|

300 |

Let us immerse ourselves in all good works |

|

and in doing good and in speaking good, |

|

|

in singing good and in reading good. |

|

|

Let us all pay heed to the minstrel |

|

|

who sang before the altar |

|

|

305 |

until Our Lady hearkened to him |

|

and held out to him a lovely candle. |

|

|

The movement of the candle tells |

|

|

that devotion readily moves God. |

|

|

If when singing we wish to please God, |

|

|

310 |

let us not be intent on screeching loudly |

|

or crying or bellowing, |

|

|

but let us be intent on directing |

|

|

to God our thoughts and heart. |

|

|

We clerics, we monks, when we sing |

|

|

315 |

in the choir our high kyrie eleisons, |

|

our sequences, our lovely hymns, |

|

|

we should be on guard that our heart be up there, |

|

|

since we know that no one |

|

|

reads pleasingly or sings pleasingly to God |

|

|

320 |

if he does not root his heart in God |

|

while he chants, sings psalms, and reads. |

|

|

Let us sing, let us sing with such delight |

|

|

that sweet God may hear our sweet songs. |

|

|

Let us think, let us think of the great joy |

|

|

325 |

and of the sweet songs of heaven above. |

|

As soon as the heart descends down here |

|

|

and does not accord with the mouth, |

|

|

the mouth fails and sings out of tune, |

|

|

and there is great discord between the two. |

|

|

330 |

People say “Lift up your hearts” |

|

because it is right that the heart rises |

|

|

up there on high as we sing. |

|

|

At a time when the accord is lovely, |

|

|

then our voices merge and join |

|

|

335 |

without delay, have no doubt of it at all, |

|

in the saintliest melody |

|

|

and in the praises that are said |

|

|

day and night by saintly spirits |

|

|

who will praise with pure heart |

|

|

340 |

God and his mother, always without end. |

|

If we sing as I have said, |

|

|

know truly, without counterargument, |

|

|

that our viol will sound loud, |

|

|

and our song will be good and lovely. |

|

|

345 |

For our viol not to be in discord, |

|

we pray to that one to make accord, |

|

|

who achieves the accord of humanity with God. |

|

|

You who have a heart, who still dance, |

|

|

and who are in discord with God, |

|

|

350 |

if your heart is in accord to serve this one, |

|

who will so tune your viol |

|

|

and harmonize your song |

|

|

that you will be at once in accord with God. |

|

|

You who still love dice |

|

|

355 |

and whom the Enemy holds in his cords, |

|

if you agree a little to the service of this one, |

|

|

your chords will come into such concord |

|

|

that they will bring you into accord with God’s heart. |

C. Alfonso X the Wise, Songs of Holy Mary: “The Jongleur of Rocamadour”

Our third and final exposition of the miracle of “The Jongleur of Rocamadour” owes to none other than the King of Castile and León. Alongside untold other achievements that have left lasting imprints on history, Alfonso X the Wise was a preeminent patron of the arts and sciences. Beyond many other contributions in the law, history, and sciences that his sponsorship enabled, he may be most famous for overseeing, underwriting, and, at least in part, composing the thirteenth-century Cantigas de Santa María or Songs of Holy Mary. This homage to the Virgin Mary in poetry went through three drafts, the first overseen from 1270–74, the second from 1275–79, and the third from 1279–83. In its final form, it comprises more than four hundred miracles of the Virgin and hymns written in praise of her. These songs are in Galician-Portuguese, a language of medieval Iberia from which both modern Galician and Portuguese descend. They are unlikely to have been the work of Alfonso alone, though he certainly had a strong hand in them.

The collection holds more than one claim to being an important monument of Iberian culture in the Middle Ages. Most obviously, it transmits poetry of enormous literary worth. Apart from its value as literature, the songbook is entitled to broader cultural relevance because of its manuscripts. Of the four extant from the thirteenth century, two contain not only musical notation but also heavy illustration in the form of miniatures. Both of these codices are products of collaboration by a large team in the Alfonsine scriptorium. The music probably emanated from an equally substantial pool of composers and performers.

Whatever their authorship, Alfonso valued the Cantigas so greatly that in his so-called “Second Testament” of January 21, 1284, he directed that all the manuscripts of them be deposited in the church where he was to be interred and that they be intoned there on the Virgin’s feast days. Continuing, he enjoined that if in the future a rightful heir should wish to take possession of the books, that descendant of his should compensate the church for them.

This is how in Rocamadour Saint Mary caused a candle to come down on the fiddle of the jongleur who was singing before her.

|

Refrain: |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary: |

|

|

we all should praise her, |

|

|

singing in joy, |

|

|

we who hope for her blessing. |

|

|

On this account, I will tell you a miracle that it will please |

|

|

you to have heard. The Blessed Virgin Mary, |

|

|

Mother of Our Lord, performed it in Rocamadour. |

|

|

Now hear the miracle, and we will tell it to you. |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary ... |

|

|

A jongleur, whose name was Peter of Sieglar, |

|

|

who knew how to sing very well and to fiddle even better, |

|

|

and who has no equal in all the Virgin’s churches, |

|

|

always sang a song of hers, according to what we learned. |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary … |

|

|

The song he sang was about the Mother of God, |

|

|

as he was before her image, weeping from his eyes. |

|

|

And then he said, “Oh, glorious one, if these songs of mine |

|

|

please you, give us a candle so that we may dine.” |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary … |

|

|

Saint Mary took pleasure in how the jongleur sang, |

|

|

and made a candle come down on his fiddle. |

|

|

But the monk who was sexton had it removed from his hand, |

|

|

saying, “You are a wizard, and we will not leave it to you.” |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary … |

|

|

But the jongleur, who had put his heart in the Virgin, |

|

|

did not want to leave off his songs, and the candle then |

|

|

settled again on his fiddle. But the brother, very angry, |

|

|

took it away another time, faster than we can tell you. |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary … |

|

|

After that monk had taken the candle |

|

|

from the jongleur’s fiddle, at once he put it there again |

|

|

where it had been before, and he stuck it there very firmly. He said, |

|

|

“Jongleur, sir, if you take it, we will take you for a sorcerer.” |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary … |

|

|

The jongleur did not worry a bit about all this, but fiddled |

|

|

as he had fiddled before, and the candle settled |

|

|

once again on the fiddle. The monk intended |

|

|

to take it, but the people said to him, “We will not allow you to do this.” |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary … |

|

|

After the stubborn monk saw this miracle, |

|

|

he understood that he had made a great mistake, and at once repented. |

|

|

He threw himself down before the jongleur on the ground, and begged his |

|

|

pardon by Saint Mary, in whom we and you believe. |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary … |

|

|

After the glorious Virgin performed this miracle |

|

|

that made a gift to the jongleur and converted the black |

|

|

monk, from then on, the jongleur of whom we have spoken |

|

|

brought to her each year in her church a man-sized taper. |

|

|

The Blessed Virgin Mary … |

|