Hair

© 2022 Ruth Rosengarten, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0285.02

I am thirteen, and this is Johannesburg. Everyone praises my long, auburn hair. Titian, some call it, though it will be several years before I learn that Titian is the name of a painter; that many voluptuous women in his paintings have rich red tresses. I love my hair, but it seems old-fashioned: the wavy ponytail, the wayward fringe. It’s the 1960s, and voluptuous is the last thing I want to be.

I scour magazines when I can lay my hands on them: Cosmopolitan, Elle. With my pocket money, I have started buying Jackie, which comes from London. London occupies a big chunk of the real estate of my imagination. There are pull-out centrefolds of singers and bands I’ve never heard of. Longingly, I examine fashion models with pixie cuts. I hanker for their doe-eyed, skinny loveliness, the edginess of their hairstyles, the crisp geometry of their short dresses. Especially, for the boys they surely attract.

You’d look beautiful with your hair like that, my mother says. You have such a pretty face. Such a pretty face. She says this many times, or so it seems to me. The pretty face, in its reiterations, pushes against something else that I don’t have, and I think I know what that is. My mother makes sure I do, but indirectly, surreptitiously. It’s something to do with my body, which must be always reined in, educated, made hungry. My mother is quite the hunger artist, but such notions are still unavailable to me. I am only vaguely aware that the site of her battle with her own body is my body, and it is a struggle expressed in opposing imperatives: Eat! Don’t eat!

I live clumsily in my body, but I also live in pictures, in music, in books. My reading seems to situate me outside of the world, and yet also, my reading is of this world: my books get yellow as my skin reddens and peels and freckles because I’ve forgotten to wear a hat; and its pages warp and waffle where I’ve forgotten to dry my hands after pulling up my pants. The attention to my body and its comforts accompanies my early readings even as now, I need to nestle and find an absolute accommodation before I can settle into reading. Back then: like most youngsters, I am a fantasist; I am earnest and questing. I dream through the books and songs and pictures I consume; they all transport me elsewhere. But those conveyances take me to places not too far away. Nurturing a kind of realism that has persisted as a character trait, and sustaining a disinterest in any form of the epic or heroic, my imagination plays on safe ground (and yes, that is a free instrument I’m sending out to my critics, go for it if you must).

I avoid sport at school and am happy when I have my period so I can get a note from my mother requesting that I be let off swimming lessons: I know that Mr Green stands on younger children’s hands as they cling to the edge of the pool, forcing them to thrash about in the water. It strikes me as a terrifying form of pedagogy. I don’t care if I never swim, despite the lovely silky smoothness of the water. My body wants to decline its own existence: I don’t recognise myself in any of the loose-limbed, outdoorsy girls I read about. I am not Jo March. I have aching nipples popping out of breasts that already fit too tightly, and for the last time, into a B cup. My thighs are omelettes oozing together at the top, where I wish they were separate; my knees join too.

I look, I think, awkward, childish.

So, I take up my mother’s suggestion of a haircut. I need to believe her: I need to trust that she knows a thing or two about short hair. That her urgings are not selfish, not personal; that she is neither moved by the daily drudgery of the school plait, nor driven by a darker, inchoate emotion.

I look at her hair made lustreless from straightening and hair spray, ruined by a longing to alter the curly course of nature. It’s a longing I shall inherit. The word envy is waiting to form itself, out in the future, but Mama, right now I need you to be on my side. When I read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s story ‘Bernice Bobs Her Hair’ (1920), I recognise something that was not present in Jo’s altruistic self-shearing in Little Women (1868–1869), a scene I always recollect with admiration and horror. Jo presents her mother with a roll of twenty-five dollars as a contribution to making her father— who was injured while serving as a chaplain in the Union army during the Civil War—‘comfortable and bringing him home.’ In Fitzgerald’s story, the dramatic bobbing is a symptomatic acting out, the misguided conclusion drawn from a competitive web of youthful entanglements.

Hair, I’ll come to understand, can be currency in unspoken exchanges, unnamed rivalries.

But that comes later.

At thirteen, I go along with the idea of the haircut despite the last-minute hesitation I see on the face of the girl in the mirror, a green salon cape draped around her shoulders. Tears etch her cheeks. ‘Are you sure?’ the hairdresser asks. Sure she’s sure, my mother says. It is then that I have an impulse that I now recognise as fully formed, characteristically my own. An archival impulse, I would call it now, using a phrase coined by art critic Hal Foster. Don’t cut it in bits, I say. Cut off the whole thing at once.

Lop off the ponytail so I can keep it, is what I mean.

Even before it has been severed from my body, in thought, the ponytail has become a keepsake. And what is a keepsake if not a thought materialised, a thing narrativised?

Now the hair is wrapped in acid free tissue paper like a treasured artefact or work of art. This hair may be as dead as a relic, darkened where I might have expected it to have faded, but it has a wild, weird electricity that reminds me of its connection to a living body. My body.

After the ponytail is chopped off, I feel light: inexplicably transformed, briefly free. But it is not too long before I feel bereft, unsexed.

For forty years after that haircut grows out, I remain fetishistically bound to my head of long, burnished curls, the first descriptor I ever use when portraying myself to strangers, identifying how they might recognise me: my pocket carnation, my intimate calling card. Scrunchy or grip always to hand, hair up, hair down, screen and shield and weapon all in one. Eventually, menopause will teach me that there is freedom to be found in abandoning bodily ideals—fuck those—along with all the other attachments I need to shed; ageing will instruct me in the joys of ditching a fixed tag (the girl with the long red hair) and gaining, in its place, something changeable, less specific. And an ongoing relationship with Ollie, the hairdresser who now asks, twinkling all over, well what will it be today? Little old lady or sexy bedhead?

Years pass without my looking at the severed ponytail, this bodily remnant, this almost repellent treasure, this thing that is me and not me.

No one who has known me for a long time and to whom I show the photograph on the cover this book, doubts that it is a self-portrait; they all recognise the hair. But I can now scarcely remember what it feels like for my shoulders to be cloaked, the thick cascades of it heavy, swirling from strawberry blonde to deep russet in the underlayer. I remember the hair resisting, then yielding, to the pull and stroke of lovers, husbands; I remember clips in, clips out. I remember pinning it up in summer, twisting it around several times before catching it with a toothy grip. I remember battles with sleekness, and the relief of submission to curls, the permission to do so granted by changing trends and new ideas in self fashioning.

But looking now at the photograph of the ponytail, the word that comes to mind has nothing to do with the sensuous pleasure of hiding behind my own hair, using it as a seductive veil. Rather, I am struck by the word severance. The cut looks blunt, brutal, and with the darkened redding rope tumbling away from the ribbon, it seems obvious to me now that this is an image of birthing, of radical separation, of something cleaved in order that something—someone—else might grow. It occurs to me that this is the most intimate evocative object I own, one that speaks of a painful personal individuation.

I want to think about this fragile parcel in crinkly tissue paper: a twisted rope filled with static, beribboned at either end. Safeguarded for decades, through three emigrations and many more house moves.

Why?

What gets kept? What gets thrown away?

The protagonist of Guy de Maupassant’s story ‘A Tress of Hair’ (‘La Chevelure,’ 1884) is a deranged man, incarcerated for his necrophiliac obsessions. Never having experienced love with another human being, he loves, instead, old furniture. It evokes in him thoughts of ‘the unknown hands that had touched these objects, of the eyes that had admired them, of the hearts that had loved them; for one does love things!’ He is drawn to the past, terrified of the present, and ‘the future means death.’ In a phrase that foreshadows Roland Barthes, Maupassant binds together death and the future: a certain configuration of the past comes to a standstill with someone’s death, and from that moment on, the survivors need to marshal their future. ‘As soon as someone dies,’ writes Barthes in Mourning Diary (2009), published posthumously but composed in intimate notes for two years after the death of his mother), ‘frenzied construction of the future (shifting furniture, etc.): futuromania.’

Through objects, Maupassant’s unnamed character experiences the arresting of time as an erotic charge, and in this frisson, it is as though death might be forestalled. He becomes obsessed with a rare Venetian bureau, which he buys from an antiquarian. In his rapture, he describes ‘the honeymoon of the collector,’ passing his hand over the wood ‘as if it were human flesh’ and looking at it repeatedly ‘with the tenderness of a lover.’ When he searches the bureau for a secret drawer, he is rewarded: ‘a panel slid back and I saw, spread out on a piece of black velvet, a magnificent tress of hair.’ Spread out like a lover’s body, the hair has been severed close to the head and is secured by a golden cord; the hair is fair, ‘almost red.’ Every night, the man caresses and kisses the tress, and the dead woman from whose head it was severed comes to him, not as a ghost, but as a presence.

My mother loved Guy de Maupassant for the cruel ironies and comeuppances in his stories, filled with people who spend their lives under misconceptions, seduced by false appearances. Harsh social justice. When I first read ‘A Tress of Hair,’ I saw the eroticised relic as my own lopped off ponytail. Why had it been kept? Why secreted in a drawer?

The distinction between relic, fetish and garbage is hair thin.

There is so much I have discarded without giving it a second thought; without giving those things a second chance at igniting my imagination, enfolding me in narrative possibility. A full compendium—an archive of life’s traces—would lead me into an infinite regression of multiple lifetimes. But in the long run, writer Julietta Singh’s succinct formulation utters the truth: ‘no archive will restore you.’

I recognise in the impulse of the hoarder a misconception about the selective nature of the archive; this, not that. But on what grounds, other than happenstance, random impulse, intuition? ‘Remembrance itself is a type of hoarding,’ writes Dodie Bellamy, ‘a clutching at love or trauma—those “others” that make us fully human—and all of us are these futile Humpty Dumpties trying to put our shards back together again.’ Bellamy writes of hoarding as écriture, but, having turned over ‘fifty-five file boxes of ephemera to the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale,’ she contrasts her writing and that of her late husband Kevin Killian (a queer and amazing couple) to hoarding: ‘though we spent thirty years of our literary life hoarding its dejecta, our writing has been committed to spewing all sorts of shit few would dare reveal. Hoarders of information we have never been.’

Intimate writing as spewing, a kind of extimacy; mulling on memories as hoarding. Our interconnected, intertwined body-minds constantly hit against questions of the archive, the body-mind as archive. What am I an archive of and what is constantly being omitted from this archive? What happens with the archive when I die?

Hoarding speaks of the limits of the archive, for who can keep—and keep track of—everything? Andy Warhol tried to. In the latter part of his life, he saved source material that he had used in his work, business records and traces of his everyday life in cardboard boxes that were then sealed. There are over six hundred Time Capsules. These boxes are now owned by the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. On 30 May 2014, the museum staff began opening them in the presence of Warhol’s assistant Benjamin Liu. The contents included correspondence, junk mail, fan letters, memorabilia from friends, soiled clothing, pornography, LPs, envelopes, packets of sweets, unopened Campbell’s soup tins, toenail clippings, the mouldy corpses of half-eaten sandwiches, postage stamps, gift wrappings, condoms, and more; but also strips of photobooth photographs that Warhol used to create his celebrated portraits, and original works by his collaborators and friends like Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Considering personal and cultural ephemera as process-driven works of art, Warhol drove the logic of the found object and of Marcel Duchamp’s readymade into the heart of American consumerism. His performative deadpan enabled Warhol to straddle the gap between seriousness and irony. He also had the resources—wealth, staff and storage—to act out a hyperbole of hesitation, the vacillation of those who live with excess and superfluity: to keep, or to toss away? Decluttering is not for the impoverished.

The studio where I make drawings and collages is home to a modest number of boxes containing my paper trail, a half-hearted archive of possibility. An aesthetic predilection for certain kinds of paper (no garish colours, a preference for the matt or the translucent, for monochrome, for the printed word or maladroitly printed image; old diaries and technical manuals, sewing patterns, washi paper) has led to certain choices (a distinctly non-archival practice of selecting on aesthetic grounds) and that means that there is much that I discard. A new cull is now overdue. But sometimes I regret the many to-do and shopping lists I did not keep, the Zoom lecture notes scratched on backs of envelopes, those gorgeous nothings, the serendipitous poetry of adjacency, the scribbles and calendar pages that might later have served as triggers or keys: clues to how, in the past, I envisioned a future. So many notes to self and notes to others have been snubbed by second and third thoughts.

I am thinking of how enraptured I become when faced with works by artists who use such ephemera, and in doing so, touch on the collector’s conundrum, the archivist’s dilemma: what to discard? What to exclude? I am thinking of certain artists other than Warhol: of Keith Arnatt and Candy Jernigan and Dieter Roth.

British photographer Keith Arnatt’s work draws me for its skewed humour and the taxonomic attention paid to overlooked objects. Arnatt himself was fascinated with systems, collections, things cast off, trivial things kept. I whirr in sympathy with his photographs of discarded cardboard boxes and paint tins, each an almost un-ironic sculpture. His Pictures from a Rubbish Tip (1988–1989) focus on decomposing matter captured in golden early evening light, resembling richly sensuous still life tableaux with their memento mori subtext turned into the main event. For The Tears of Things (Objects from a Rubbish Tip) (1990–1991) Arnatt removed items from the Howler’s Hill rubbish tip, brought them into his Tintern home and photographed them on an improvised wooden plinth in the manner of lofty statuary. Minute decaying and mouldering scraps of wood, fabric, glass, and rotting food stand out against a hazy, unfocused background. I want to find these hilarious, but their poignancy and abject beauty hits me. Arnatt’s photographs of dog pee leaving abstract expressionist drip paintings on trees is hilarious and I wish I’d thought of that. And here is a series of photographs of notes Arnatt’s wife Jo left him on the kitchen table in the early 1990s (‘pies in microwave—press down thing that says “start” to start/In bed but awake/Where are my wellingtons, you stupid fart?/Let dogs out before you go to bed/You bastard! You ate the last of my crackers’). As it turns out, they served as poignant testimony after Jo died of a brain tumour in 1996: evidence of love and of the singularity of life à deux, made and remade in daily rituals of companionship and care.

Candy Jernigan, an American artist who died of cancer in 1991 at the age of thirty-nine and whose work was collated in a beautiful book called Evidence in 1999, collected traces of her living, the cast-off ephemera of urban life. She would preserve these items in sealed plastic bags, but she also drew them. The presentation of her evidence brings together the meticulousness of the archaeologist or forensic pathologist with the energetic inventiveness of a dada bricolage artist, transforming trash into works of fragile beauty. Evidence was, for Jernigan

any and all physical ‘proof’ that I had been there: ticket stubs, postcards, restaurant receipts, airplane and bus and railroad ephemera… food smears, hotel keys, found litter, local news, pop tops, rocks, weather notations, leaves, bags of dirt—anything that would add information about a moment or a place, so that a viewer could make a new picture from the remnants.

It is as though living itself were not enough (as, indeed, for me it isn’t). She needed sustained acts of collecting: substantiation in the form of traces, indexical remainders.

Dieter Roth, a German-Swiss artist remarkable for the range and diversity of his practice was also an inveterate archivist of his own life, similarly obsessed with keeping track—and leaving proof—of his passage through time. His traces exist as physical items filed or boxed, but also as diary notations. To this end, every aspect of his existence, including his working process and the materials he used, constituted the content of his work and also its medium. For his Tischmatten (Table Mats) begun in the 1980s, Roth placed grey cardboard mats on tables in his homes and studio, collecting on them what he called the ‘traces of my domestic activities,’ which included drips and stains from studio and kitchen alike, doodles and encrustations of paint, and items that he affixed onto the mats: leftover food, notes, doodles and photographs.

In his durational project Flat Waste, which had two iterations (1975–1976 and 1992), Roth, like Warhol, gathered the banal, unique traces of everyday life under consumer capitalism. His only guiding principle was that every item collected be flatter than three sixteenths of an inch: this included food packaging, receipts, envelopes, slips of paper, handkerchiefs, offcuts of drawings and leftover food, amassed as the artist travelled between cities, visiting bars and restaurants, galleries and friends. Through the detritus of the life of a privileged, celebrated artist in the second half of the twentieth century, he created a kind of deadpan autobiography. This forms part of an ongoing reworking of the confessional genre through a representation of the material conditions of his life. The stuff gathered was placed in transparent plastic sleeves and filed chronologically in ring binders. There are 623 ring binders in total, exhibited on wooden shelves and bookrests in an installation that models itself on the archive or the library.

Appearing as a motto on the front of Roth’s book 2 Probleme unserer Zeit (1971) published under one of his heteronyms, Otto Hase, Roth writes: ‘Of what does time consist?—Of the fact that it passes.’ This lies at the heart of the work of the artist as a collector of moments, as an archivist of his own transience. Such endeavour is hyperbolised in Roth’s final work, still in the making when he died. Solo Scenes (1997–1998)—a work of one-upmanship on Warhol’s real time movies—is a video diary made in real time, capturing the daily activities of what turned out to be his last year. In the final, posthumous installation, 131 video monitors are stacked in a grid, presenting the simultaneous, continuous footage, with each monitor dedicated to a different point in the artist’s daily routine.

What struck me, looking at Roth’s late work at an exhibition at Camden Arts Centre in London in 2013, was a sense of fascinating futility, since in all this endeavour, I could not find Roth himself. Jernigan is more present in her work: the drawings leave the unique marks of her hand, their combination with actual detritus has an improvised, individuated quality. But with Roth, whose work appeals to me immensely at gut level, I feel as though despite (or perhaps because of) all the obsessive record keeping, he has managed to slip away.

I find a formulation for this in Sven Spieker’s book The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy (2008). In his discussion of how Andy Warhol seems to disappear from his own Time Capsules, Spieker says: ‘What an archive records […] rarely coincides with what our consciousness is able to register. Archives do not record experience so much as its absence; they mark the point where an experience is missing from its proper place, and what is returned to us in an archive may well be something we never possessed in the first place.’ The question is more acute when the ‘experience’ referred to is a mise en abîme: the experience of attempting to pack life into an archive. The arkheion, it turns out, is not the storage space for memory, but rather a filing cabinet containing that which replaces memory: a technology, a system. It might even turn out to be nothing short of a lumbering monument to the obliteration of memory, a bureaucracy for upholding the art of forgetting.

But still, I feel safe thinking about how I archive my stuff: the systems I use to keep, retrieve, obliterate. Without such systems, I would be unmoored, floating in pure presence. I can’t do that. I am an officiant at the altar of memory, and when I panic, in a futile attempt to align myself with my breathing at this very moment, there are always the mementos from the past to tether me, the idea of a future to establish a gravitational pull, and the imperatives of the digital infinite scroll to distract me from all of it.

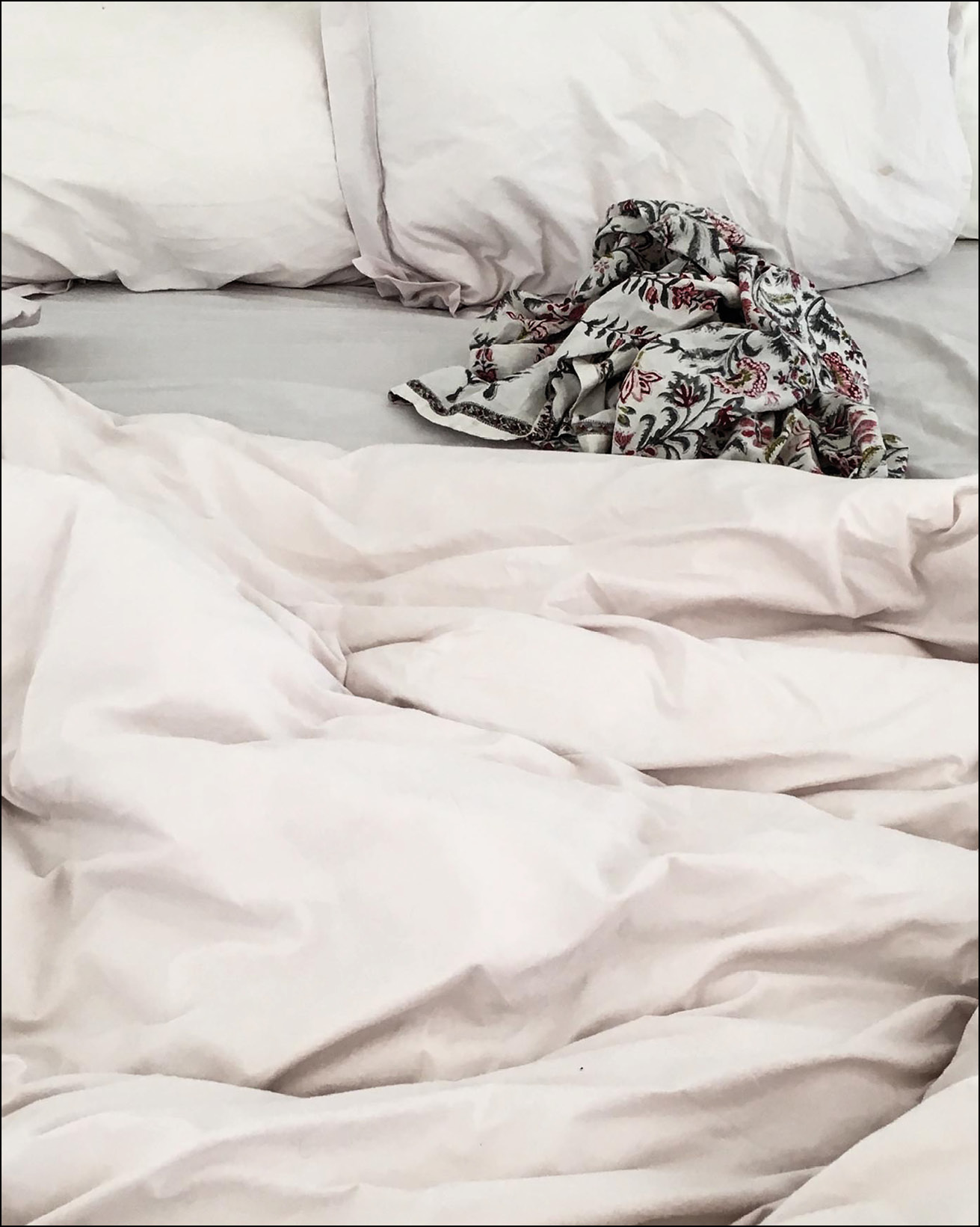

I recognise in my youthful impulse to preserve the severed ponytail a fascination that I have continued to nurture with remnants and traces. Testimony of existence linking then to now. In my studio, I have drawn scuffed and battered shoes, gloves that bear the imprint of hands, bendy hats doffed. Outside, I photograph food leftovers on a picnic blanket, animal pelts and bones and viscera flattened on road and footpath, footprints in muddy soil, the impress of paws on beaches. I have many times photographed the scraped remainders of meals on plates; sheets that have been slept in, loved on. With my iPhone, I snap a mascara-impregnated tissue, a forsaken hairclip, a dust-snarled broom. The disembowelled, dismembered, flattened fluffy toys of several generations of dogs are precious to me, evoking the syncopated soundtrack of nails scuttling on wooden floors.

Tracks, Traces, Evidence

These things that are almost no longer things—disintegrating, torn apart—are not only the past tense made concrete; they are also of course reminders of the future, which is death. Nothing lasts, and such scraps—as signs of erasure—are the bearers of a muted grief. Parents keep the evanescent mementos of infants precisely because infancy itself is so fleeting. Hair cuttings, nail parings, milk teeth: the parts that grow again and that transition between the body and the outside world—of the body but not in it. The strange tense of such squirreling of remnants is the future-past: it will come to be a snapshot of the now-time, a relic of this little person whose body will grow beyond recognition. (Lovers’ hair in lockets, invested in a future separation or loss, served a similar memorial purpose; in a modern version, I kept the lint that P picked out of his navel every night; kept it in a glassine envelope like the precious thing it was, half joke, half not-joke.)

With babies, the present appears especially fugitive, asking urgently and pointlessly to be snatched from oblivion, as though to keep a record were to impede two opposing forces: growth on the one hand, and obliteration on the other.

If I had been a mother, like artist Mary Kelly I would have made an archive of my child’s nail parings, the fine curls of the first haircut, remainders of milk and poo and vomit, feeding bibs, precious scribbles. But Kelly’s brilliance in her Post-Partum Document (1973–1979) lies in her ability to bring the elements of this intimate archive into the public sphere, making it as legitimate a subject for art as traditional portrayals of mothers and infants; from the point of view of the contemporary female observer, more convincing than the idealised Madonna and Child.

Post-Partum Document contributed to a complex conversation about motherhood and women’s domestic labour at the emergence of second-wave feminism. It is a large-scale installation consisting of 139 individual pieces, mapping the relationship of a mother—Kelly herself—with her male child, Kelly Barrie, over the first six years of his life. Different aspects of the intimate experiences of mother and child are recorded in six sections (Documentation I–VI), fostering connections with varied discourses (scientific, medical, feminist, educational and so on) through which child rearing is considered. The work explores the trajectory from the original symbiotic relation of mother and child, through various stages of attachment and separation to the constitution of the child’s identity and his growing autonomy. In the process, Kelly also documents maternal subjectivity in its struggle with contradictory impulses: on the one hand, the desire to merge with and protect the child; on the other, the impulse to enable the child to find his own way as an autonomous being.

The theoretical framework for Post-Partum Document was Lacanian psychoanalytic theory. In gesturing to the dearth of works of art exploring the mother and child relationship from the point of view of maternal subjectivity, it has been highly influential on numerous generations of feminist artists. Contained and constrained by the protocols of both minimalism and conceptual art (the use of documents, a predilection for grid formations in hanging; an unemotional and coolly analytical approach to subject matter), Post-Partum Document juts through its theoretical structures and speaks to maternal compulsions.

I know I first encountered the work in reproduction in the early 1980s; I have never seen it physically in its entirety. I know that when I first became aware of this work, I felt liberated by the range of possibilities now offered by the moniker artist, though I had no idea how to translate this into my own practice as an artist, or my practice as a writer: the two remained separate for too long. I know, too, that when I first encountered this work, I was left with a feeling of longing, despite Kelly’s refusal to engage with the more emotional side of maternity. This was long before I thought of myself as childless, or even child-free, long before the harrowing encounters with reproductive bio-technology. Children were in the future. For women of my generation, Mary Kelly was a role model, an older artist who not only combined practice and theory in her work, but who also made it look possible to be both a serious artist and a mother.

As things turned out (that sharp visibility afforded by hindsight), without children, it has been my own body—my own life—that became the source of such longing and loss, preservation and release.

I am consumed by the wish to document the material leftovers of my trajectories, to chronicle this singular and ordinary life through its traces. My need to preserve an archive of the ephemeral has adhered stubbornly to objects that have, in turn, become the transmitters of that very need. Objects to which I am immoderately attached.

I am, of course, not unique in this. In the opening lines of her memoir on the aftermath of the death of her husband, John Forrester, Lisa Appignanesi writes that though she has given away his clothes, discarded ‘unopened packs of tobacco, wires that belonged to defunct machines and some of the other leavings of life,’ she somehow cannot throw away ‘a small translucent bottle of shampoo […] the kind you take home from hotels in distant places,’ something entirely banal and commonplace, which had outlived him. She knows that in some way, superstition drives her, for some reason, significance has attached itself to that particular object above others. ‘We all know the dead inhabit select objects,’ she says.

Similarly, considering photographer Tina Ruisinger’s body of work Traces (2006–2016), a ten-year project photographing the things left behind after people have died, Nadine Olonetzky writes:

There are some things that we associate with only one single person. Even when the object is a mass product. A leather belt, for instance; a pair of jeans; a pearl necklace. But for us, it is the leather belt; the pair of jeans; the pearl necklace. How very little is required to spark so much? We put our face in the scarf, and a whole world forms.

Ruisinger’s photographs include a cardboard box containing five tuning forks, a pen, a pile of colourful shirts, a set of old kitchen knives, a pair of men’s shoes, a manicure set, a child’s jumper, diaries and ledgers, index cards, a bag of buttons, a pair of boots, a key, a photograph album, a small cutting of hair, folded jeans, a mended pipe, the corner of a chair. These items are photographed in isolation, close up. Sometimes, they are pictured, from above, in a way that links them to the images that I have included in this book, a tradition allied to documentary and forensic photography; in other images, the contrast between sharp and soft focus and a more off-centre framing speaks of an immersion in a tradition of still life. A tattoo brings memorialising traces right onto the body. One photograph shows the frontispiece of a book with a quote by Claude Lanzmann: ‘life is banal; death is a catastrophe’.

Not only the dead, but those others who are now lost to me, others with whose stories mine are intertwined, who contain broken-off bits of my own past and my misplaced selves, are similarly contained in certain objects. Although they do not add up to a coherent portrait of me, the objects are touchstones. Like the iconographic details of Renaissance paintings that I was taught to decode—a shell, a fig-tree, a dog—they serve as narrative shortcuts.

The trail of free associations unleashed by my evocative objects tracks through not only vision, but all the senses. I cannot hear certain songs (I’m So Tired of Being Alone by Al Green springs immediately to mind; Don’t Give Up on Me by Solomon Burke) without thinking of P, and This Feeling by Alabama Shakes takes my whole body into a big fat snog watching the last scene of Fleabag, and Janet Baker singing Du Ring an meinem Finger from Schumann’s Frauen-Liebe und Leben will always transport me to a messy flat in West Hampstead in the early 1980s and to a then-new Australian friend throwing an olive up in the air and not catching it with either mouth or hand on its return. Smell reaches even further, deeper into that region ‘more intimate than those in which we see and hear,’ as Marcel says in a hotel room in Balbec in Within a Budding Grove (1913). He locates ‘that region in which we test the quality of odours’ at the very heart of his ‘inmost self,’ where the smell of flowering grasses launches an ‘offensive against my last feeble line of trenches.’ There is no defence: when someone in my proximity applies TCP, my husband Ian—over a decade dead—is summoned: the timbre of his voice, the strigine combination of green eyes and spectacles, the sheer cliff of his nose; his scorn and his kindness too in that antiseptic hit.

Those of us who live amidst many possessions of whatever nature might feel the need to assess (continuously or occasionally) which objects to discard, which to preserve. ‘Things are needy,’ writes Ruth Ozeki in The Book of Form and Emptiness (2021). ‘They want attention, and they will drive you mad if you let them.’ Maria Stepanova describes her aunt Galya taking things from one room to another, then tidying and re-evaluating, decluttering and re-cluttering individual rooms. I have several friends for whom such an ouroboros of activity would be familiar; it describes me too. While Internet shopping has seduced many of us in the West with apparently seamless, obstacle-free access to stuff, further abstracting our already abstract notion of money (not linked to sheep or cows, not even to gold), we are also constantly assailed by an opposing solicitation: declutter. The word is sonorous with moral virtue.

In Extremis

It is easy to forget, from the perspective of material comfort, that for millions of people, the need to strip away possessions is far more than a fashionable dialectic between excess and purification: it is an imperative of transience and precarity. In an essay ‘Goodbye To All That’ (2005), a riff on Joan Didion’s eponymous essay (1967), Eula Biss reviews her four moves while living in New York. ‘Each time I owned less,’ she writes.

I left New York without even a bed. I no longer had potted plants, or framed pieces of art, or a snapshot of my father. I remember the moment when I threw that snapshot out. I was sifting through my things before another hurried move with a borrowed car, and I looked at the photo, thinking I don’t really need this—he still looks almost the same.

It is striking that Biss feels that even a photograph is too much to carry; this clearly speaks of an extreme of mental duress. It is more frequent, under such conditions of adversity, for people to preserve a bare minimum, however flimsy: material reminders of intimate ties and of how we come to be who we are. This mattering of our lives—the expressions of what counts through certain material things—throws a light on those elements of our autobiography that we value and wish to safeguard.

Several photographers in the last decade have sought to explore the relationship between subjects and their material objects. For his project Home and Away (2014–2015), Malaysian-based photographer Adi Safri spent time with asylum seekers crossing the border into Malaysia. Safri created photographic portraits of some of these refugees, each framed individually, facing the camera directly. Their quiet poise suggests, in each case, that being a refugee is a condition, not an identity. There is nothing arty here in these photographs: these images are unapologetically witness statements. Each person is captured holding a possession she or he could not bear to leave behind. These include a school bag, a stuffed toy (gift from a lost father), the dress of a small daughter who had to be left behind, a pair of flip flops used at the time of escape, a traditional Somali shawl, a slingshot given to a boy by a childhood friend, an engagement photograph.

In a similar vein, German/British photographer Kiki Streitberger’s project Travelling Light (2015) considers, out of all the displaced people worldwide (around 65 million in 2015) the 30,000 people who undertook a perilous journey across the Mediterranean to Europe in 2015, often having paid extortionate sums to smugglers, and surviving—if they survive—gruelling hardship, while facing uncertainty and possible deportation at the other end. Streitberger’s photographs of items of clothing flattened against a white ground have about them the cool, unemotional quality of documentary images, though her work is exhibited in art contexts (the two professional circuits—art and documentary—have often been kept apart). The images are paired with transcribed verbal testimony. A sample:

- Ahmad, 40, printer and shop owner: I bought the kufiya in Syria and I bought it for the journey. It is very important in Palestine, but outside Palestine it’s not. I had it with me to protect me from the sun and the sand […] The lighter is from my supermarket. I have had it for four years. It’s now broken but I still want to keep it as a memory.

- Nezar, 11, student: The pink document is my school report. I brought it because I was the best in my class. My favourite subject was Maths. I had so many friends in school. I miss them.

- Asmaa, 36, home economics teacher: The prayer dress is a gift from my mother. I got it while me and the children stayed with her in Latakiya. I had another one in Damascus, but when our house got destroyed everything we had was lost […] On the journey I didn’t pray. I kept the dress in a bag.

Streitberger’s deadpan images display what people who leave almost everything behind to embark on a precarious new life choose to take on their journey and what these items mean to them.

I was struck by this body of work when I saw it in the ‘Contemporary Issues’ category of the Sony World Photography Awards exhibition in London in 2016. Now I look at them again. I google Streitberger to see what other work she has made. It includes a project titled Chimera (2013) tracking the effects on her of a stem cell transplant she underwent that saved her life. Writing of her donor, she says: ‘for the rest of my life, his blood will flow through my veins. Genetically, it is always his. He will always be a part of me.’

I am interested in the different ways Streitberger’s work focuses on borders and traces, including the boundaries between her and another human being, and the traces of another human being in her blood: otherness incorporated. I return to the images of the possessions of refugees to chastise myself, for bad faith, for excess.

Reading and Writing Objects

Objects—like new facts about the past—make inroads into the fluid, ambiguous spaces of memory. Essayist Brian Dillon says that there is something terrible ‘about the way a dumb artifact can lead us back to the past, if only because its very existence is at odds with the passing of the bodies to which it might once have attached itself, or with which it once shared the space of daily life.’ Objects might remind us of our old selves or of other people, but that very association can land up fossilising the living, changeable beings we once were, and those others whom we miss.

Such objects, though often totally ordinary at the outset, are plucked away from the realm of plainness—the category of the merely objectual—by the power of contiguity, the friction of usage, the pull of association, the force of evocation. Unlike Proust’s madeleine, a sense impression that prompts a chain of uninvited associations by stealth, these are objects that we purposefully hold onto: mementos, keepsakes, souvenirs, amulets. I am, as I write this, remembering the gnarled potato that Leopold Bloom carries in his pocket in Ulysses (1920), first appearing in the ‘Calypso’ chapter, where, on leaving his house, he searches his trouser pocket for his latchkey. ‘Not there. In the trousers I left off. Must get it. Potato I have.’ Associated with Ireland’s history, the shrunken tuber rubs against other pocket objects and gradually serves, for Bloom—who is strolling with hands in pockets—as a reminder of Molly’s infidelity but also as a talisman against violence and other dangers, a possible prophylactic against rheumatism and as his ‘poor Mamma’s panacea.’

Like the treasured artefacts that fill the vitrines of historical and archaeological museums yet without any material value attached to them, my evocative objects are touched by the everyday magic of time as a medium. In them, self and body become enmeshed. They are reminders of how, incarnate, I glide or limp, sprint or amble into the future. They not only inhabit my life in ways that illuminate who I once was; subtly, they shape the very substance of that self as it moves forward into the future.

I think about the notion of a self and how shifting it feels, a conglomerate of agencies that are not autochthonous and identifications moving in different directions and in multiple temporal dimensions. I remember reading about Katherine Mansfield’s conception of her ‘many selves’ and spend a good hour following it down a rabbit hole. I hear, and then track again, an episode of Free Thinking on Radio 3 recorded in 2020, in which neuroscientist Daniel Glaser describes the concept of self from the point of view of the brain. ‘The self,’ he says, ‘is the consistency about the relationship between me and the world, it’s that which is preserved.’ From the brain’s point of view, objects define a self through their solicitation to performance. Objects, in other words, are things that make you want to act, with or upon or through them; not only verbs, but prepositions too. Through such an invitation to engage with a thing and also to use that thing upon other things in the world, you know you have a body. An espresso cup elicits a different response from, say, a sponge. A pen. A lipstick. I wonder to what extent that is still true when the self might be defined as that entity that responds with flickering attention to clickbait generated by bots and contributing to the huge complex machinery of global capitalism. Still, I find this reversal of everyday logic not only simplistic, but also seductive. Objects are addressed as physical entities with particular characteristics that invite—or in the case of the arrested status of evocative objects, have already invited—action.

Yet that material encounter does not describe the ways in which they also bear the contracted, compacted sediments of so many physical and affective encounters with us. Our appropriation and appointment of objects according to the expression they enlist is, in other words, also historical; it has its origins in our material and affective past.

Objects are further complicated by the fact that they change over time, both in themselves and in how they summon us to consider them. And when objects remain in a deep slumber for months or years, our re-encounter with them may be a kind of revivification. We rediscover them, we act on them once again, feeling anew the lure of the mnemonic, which is also the lure of the future. Perhaps these secondary acts are ones of restoration, touching us as we touch them, with hands as remedial and alleviative as bandages.

We attach ourselves to objects because of their perceived stability: this ponytail, this handkerchief, this sled with the word Rosebud inscribed upon it. The very thingness of our evocative objects, their staunch assertion of presence, confers the fantasy of stability on the subject, on me.

But with our fervent attachment to meaningful objects, we sometimes forget that the relationship between humans and the object world in which they are immersed is never that firmly fixed. We know the natural world is in flux, but a visit to any museum will remind us that the artefactual world is not stable either. Time not only corrodes and reshapes objects, it also affects our association with them. Even our relationship to deeply cherished mementos can suffer the whips and scorns of time. Objects, in other words—even ones that are not charged with the burden of carrying our personal histories—have contours that are more porous than we might imagine; their quiddity is not necessarily assured. And so, the self finds and defines, and then re-finds and re-defines itself in the process of assigning shifting mental and emotional places to and for such things. Loved, unloved, loved again perhaps.

Simultaneously, much as evocative objects serve as pocket memorials, as I grow older, I find myself overwhelmed by the desire to disencumber myself of the dead weight of things, their meanings, their link to grief, to loss. This makes me think of Orson Welles’ classic Citizen Kane (1942), where, amidst prodigious collections of useless objects, the memento enjoys a certain tyranny. And sometimes, its nested allusions point simply to other mementos, a meta-text of memories unmoored from any founding subjectivity. This seems like a cautionary tale. I find myself longing to achieve a whittling down, an existential minimalism. To examine my store of inner objects and count on them more confidently. And even perhaps to rely less tentatively on the flow and ebb of recollection, allowing what gets lost to remain lost. Making the job easier for those who will one day have to clean up after me. Or rather: I long for such release, and equally I don’t. Because to long for it is to acknowledge ending. My ending.

Writing shares with photography the semblance of defying death, or at least of deferring it. It is a clean, space-saving way of laying claim to things, having them still, or having them again; an opportunity to reassemble fractured pieces of the near and distant past into the narrative shapes on which memory insists. I am hoping that eventually, it will obviate the need to cling onto stuff by writing about it, but I am not certain this will happen.

For me, now, writing away from my old discipline of art history has become a way of thinking about objects without the restraints of set methodologies; has become a vehicle for the meshing together of autobiography and theory, of experience and thought. And I love the way writing remains constantly in dialogue with other writing: I am always also a reader; perhaps first and foremost, a reader.

I have drawn on an archive of works by writers and artists that have been meaningful to me, that—for different reasons—have addressed me over the years in my capacity as writer, artist, occasional curator, daughter, lover, friend, dog-mama. It has taken me many years to come to realise that my art practice and my writing practice do not exist in separate, airtight containers. What writer and curator Lauren Fournier describes as ‘the entanglement of research and creation’ in which ‘artists and writers wrestle with the place of theory and autobiography’ both in their lived experience and in their practice, speaks directly to me, of me.

Thinking through and with the objects that serve as signposts to my history seems to be but one step away from telling my stories through this miscellany of the non-functional, this bounty of useless, haunting objects. As I write ‘telling my stories’ I think: no. No, it’s not that. I roll my eyes when I hear the words storyteller, or, worse, raconteur. Bore. This exercise, I feel, must surely throw light on connections that I have not previously made, that I forge in the telling, but that also speak to others of their entangled associations. More significantly, I am hoping for light to be thrown on aspects of my own thinking that have remained in hiding; that have slipped through the scaffolding of the stories that I have frequently, perhaps unthinkingly, told others, told myself.

The objects that unleash my trains of association and unfurling narratives are as idiosyncratic as anyone’s private relics. My ponytail would certainly give some people the creeps: to me it evokes me in some quintessential form.

I find that in order to write about these objects—in order to experience them in a mediated, communicable way—I need to photograph them first, as if to fix and contain them, to pin them down and frame them already in representation. I am particular in how I do this. I want the ground on which the object is positioned to be pale; I want the light to be soft and fairly even. No artificial lighting, no horizon-line. But, despite the care I take in framing and lighting, I don’t want these images to be too artful. Nevertheless, their quality as images is not immaterial to me either: they are not snapshots. And I cannot begin the process of mnemonic unwinding and rewinding, of un-forgetting and association, without first positioning the image on a blank page on my virtual document, the one here, on this screen. Scaling and centring it; containing it in a fine outline to separate it from the luminous page-that-is-not-a-page.