1. The Theoretical Framework: Common Goods and Systems of Common Goods

© 2022 Mathias Nebel, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0290.02

Reasserting the Notion of the Common Good in the Twenty-First Century

My goal in the following pages is to propose a possible understanding of a common good approach to society for the twenty-first century. This is certainly not a full-fledged theory of the common good, but rather the scaffolding for one. We apply many insights of antiquity and medieval times to the notion but then reframe the concept from the perspective of a philosophy of action.

This reframing is actually our main shift in our approach to the concept. The common good has to do first and foremost with action, and not so much with metaphysics. In essence, the concept is linked to how our social interactions are generated and thrive. A common good perspective on society is therefore neither totalitarian nor conservative. On the contrary, it is creative, capable of novelty and inclusiveness; it embraces not only justice and law, but also the purpose of the good life in politics.

I will proceed in two stages. The first section lays the foundation for a reinterpretation of the various traditions of the common good. The second considers the common good’s dynamics, structure and essential elements.

1. The Common Good Belongs to the Sphere of Action

I. A Notion Implicit in All Public Action

My main intuition here is that the common good is not only or even primarily a metaphysical concept—it is an ethical principle, a principle that governs action and remains implicit in all action undertaken in the public realm. The common good is not first and foremost a question about the good itself, or about the hierarchy of human goods, or even about whether the whole or the part has priority. It is not primarily a comprehensive view of the good—some complex, splendid architecture in which each part fits into the whole, as in a cathedral. My conviction is that the common good is based on the logic of common action and cooperation (Sherover 1984, pp. 475–498; Sluga 2014, pp. 155–167).

The essential input from scholastic authors on the common good was metaphysical, focusing on the quality of the ‘good’ in the term ‘common good’ (Kempshall 1999, pp. 76–101). But in the order of action planning, it is the ‘common’ generated by our interaction that is the crucial question (Arendt 1985, p. 50; Bollier and Helfrich 2015). How a community rallies around a goal, and congregates in the pursuit of that goal, is the key element of the common good. This is Thucydide’s conviction: the most precious and primary common good is our common freedom (Palmer 1992, pp. 15–37), a thought that Aristotle would further develop in his assertion that the entelechia of a city is our common humanity, emerging in the form of shared practice or virtue (Aristotle 1094). A widely shared assumption among philosophers of antiquity is the idea that the common good has to do with the expression of the human logos and, more specifically, with the glory of the deeds of freedom (Palmer 1992, pp. 111–114).

That is why the question of the common good is far more prosaic and specific than is usually thought, for it is implicit in all interaction. As soon as common action is wanted, it carries a hope, the hope of a common good; and as soon as it is conceived of, the interaction reveals the structure of a dynamic, the dynamic of the common good (Nebel 2006, pp. 7–32). The issue of the common good can be extended to all public or political action, for it is its principle and its driving force.

Of course, this assertion can be seen to conflict with warfare, which grows out of the constant wish throughout history to appropriate other people’s goods by force, subterfuge, or lies.1 It seems almost laughable to claim that the basis of public action is the common good, for experience seems to show that private interests and power plays are the true basis for politics. This is an old argument. Machiavelli framed it in a treaty; Ludwig von Rochau coined a name for it: realpolitik (Machiavelli 1995, Von Rochau 1972). Yet it is not the only reasonable, prudent option, nor does it reflect the whole experience of politics.2 It is a narrow understanding of the common good, sized down to fit the interest of a prince, a social class, or a nation. It sees the common good of others as inherently antagonistic to its own and therefore discounts the possibility of a universal common good. Sound politics are then reduced to the protection of our own interests and renounce the search for something bigger—namely the universal common good.

Maintaining that the common good is based on action means asserting that it can be grasped and understood only through action. If the common good is a normative concept, it is dynamically so, as a duty to act and a horizon for action. For in action, as Blondel once remarked (Bondel 1893, p. 326), we may recognise something similar to the Kantian categorical imperative (Nebel 2013 pp. 151–163). There is a need to act. There is a duty to act. And since antiquity this duty in the public sphere has been named and framed through a concept: the common good.

II. The Need to Act in Common: The Community Created by Common Action

Whenever you have a mass of people, it tends to organise itself through a combination of shared history, common needs, or primary forms of human solidarity. Certain goods emerge spontaneously as being useful to all, and appreciated by all. Producing such goods, organising their distribution, and obtaining them—this is what will organise the masses; this is what forms the basis of society; this is what makes a fluid group of individuals gradually create a common way of life, shared institutions, and a culture whose social goods mold collective habits.3

This is not a vision of the mind, but an empirical fact, as state-building practices have shown (Weller and Wolff 2005, pp. 1–23, 230–236). It can be seen whenever war, poverty, or misfortune force a whole population to flee. What forms the rationality of everyday life—family, work, friends—is now lost. War and/or poverty have destroyed the former structure of society, and its culture, standards, and institutions no longer operate. In fleeing imminent danger, refugees are a mass of individuals united by misfortune, the hope of a refuge, and the desperate urge to survive. And it is these common features that generate the embryos of society: on the road you have to keep eating, find water and shelter for the night, plan the next day’s journey. The importance of these primary goods is the basis for collaboration. People work together to meet these basic needs; they will collaborate and organise, for it is easier to obtain them together.4 It is this shared action, this organisation in common to achieve a social good, that the notion of the common good describes.

The common good is linked to these interactions that forming the basis of community life. The notion can’t be properly grasped without referring to these common needs, these shared goals, and the primordial forms of care and solidarity that tend to unite us. Wherever there is a community, the question of the common good arises at this practical level. What are our common needs? What goods do we need? What shared benefits may we get by seeking a specific goal together? The question of the common good is specific, not speculative.

The question arises again and again in every community or society because of the innumerable interactions that take place and then must be continued, recast, or abandoned. None of these interactions is spontaneous or natural. Societies are not mushrooms. They do not grow in the dark through some kind of systemic autopoiesis (Luhmann 1997), repeating some given, ‘near biological’ pattern of organisation. On the contrary, they are free, fragile, and conscious. And so the question of the common good keeps returning to the forefront, requiring public decisions to be made and political governance to be exercised. Political governance, most specifically, is at the core of the common good question. It is the place where the question should arise, be debated, and settled, as we will see later on.

III. The Elements of Common Action

What are the elements of common action? With Mounier (1949, pp. 15–29) and Ricœur (1990, pp. 86–89, 109–110, 167–179), we may distinguish the following: the subject of the action, the object of the action, and the social stage on which the action unfolds. The subject is, of course, the ‘who’ that performs the action, in this case a collective subject, a group of people sharing a common intentionality and linked together in pursuing the object of the action. The object describes the purpose of an action, the goal it aims for and gradually achieves, while the social stage is the cultural environment ‘enabling’ the action, the environment where it ‘makes sense’ (Ricœur 1986, pp. 168–178, 184–197).

The action keeps the subject and the object together on the social stage (Ricœur 1986, p. 193). What is more, action is the specific form through which the subject appears to others on the stage: the unique way they exist for others in this environment. What appears on the social stage is not the subject ‘in itself,’ but an ‘acting subject.’5 Similarly, the goal of an action is ‘present’ in our social environment mainly through the very action achieving it.6 It is present on the social stage as an ‘object being realized.’ Finally, there is the ‘world of the action’ (Ricœur 1986, pp. 168–172), i.e., the cultural context giving coherence and meaning to the action. The action is thus never a mere machine that mechanically transforms an intention into some output, but the main way in which both the subject and the object exist on the social stage (Ricœur 1990, pp. 86–92). There, the subject and object of the action are coextensive, united by the very process of their interaction.

On the social stage, the subject is never neutral. It is in-formed by the cultural context. The subject of a common action is always a situated subject, regulated by the social stage in its language and the shared rationality used by the group’s members, and limited by the larger cultural assumptions structuring this community. As Walzer (1983, pp. 6–10) indicates, there are no pure, timeless, or a-cultural subjects. It is on a distinctive social stage that both the ‘acting subject’ and the ‘achieved object’ will acquire a specific meaning and be appreciated as having a value and representing a good (McIntyre 1984, pp. 206–210).

What strikes us then is the great fragility of action, and indeed its impermanence (Arendt 1958, pp. 188–191). Action must constantly renew itself in order to endure. It must constantly retrieve its intention and reinvent itself to face unforeseen events, while making sure to maintain the commitment of the people involved. The miracle of action is that it exists! Its main hazard is that it may lose its dynamism and be dispersed. Action is maintained as a tension—an in-tention to achieve something—that is constantly threatened by the fragility of human commitment and the tribulations of time.

This perspective affects how we perceive subjects as different and external to the action. They are not. They are part and parcel of the action, and the main question is then how the subjects may remain themselves while changing through the action. How can the subject’s intention and commitment be maintained for the long term? We are talking here about the subject’s unity and stability while acting.7 Similarly, this perspective changes the way in which the object of the action is perceived. The question becomes how to maintain the unity of the object pursued by the action while the action is taking place.

I will therefore study the notion of the common good by transposing the question from the metaphysical level to the ethical level of public action—in the hope that this will re-emphasise the practical dimension of the common good.

2. The Vocabulary of the Common Good

The notion of the common good is an old one and its lexical field is broad.8 Through the ages, and through various translations, many terms have been added to this field, either to establish distinctions that were deemed necessary or to express specific aspects. The use of the same term by different writers should, therefore, always be treated with caution. More often than is realised, a notion may be understood in quite different ways by different authors. It is this polysemous vocabulary that I will address in this section, specifying each of the terms that will subsequently be used in the next chapter.

I. The Social Good and the Shared Value of the Common Benefit

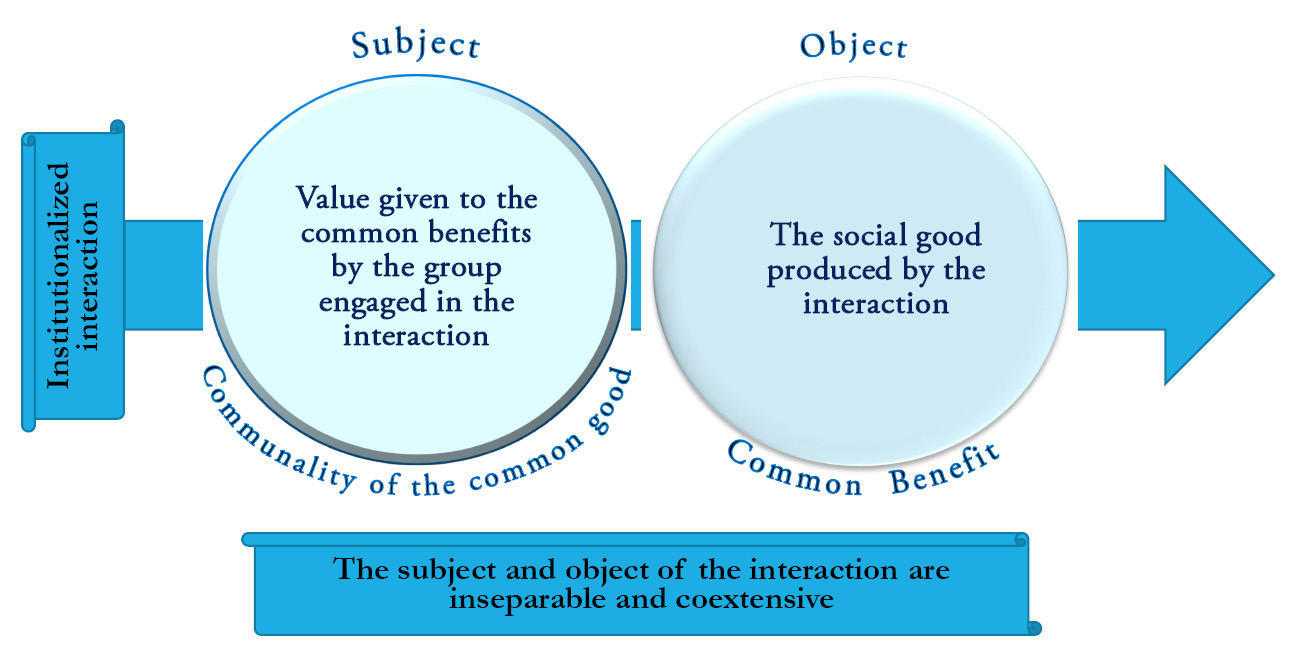

Figure 1. A common good as shared interaction producing a given social good.

As we see in Figure 1, every interaction has a certain object and gradually achieves it, unless the interaction is in vain. I will call this goal of interaction the ‘social good.’ We must remark first that the social good is not just the result of an interaction, but is coextensive to the interaction itself. Secondly, the term ‘good’ is not used here in an explicitly moral sense; it simply means that the community of people engaged in its achievement usually assigns a positive value to this good. Finally, the social good adds something to the community: a collective capability whose distribution we will call the ‘common benefit’ shared among the community (see Chapter 4).

The relationship between involvement in the interaction and sharing in the common benefit is one of the main features of a common good approach to society. Yet the criterion for distributing the benefit is not necessarily equality, nor even complex equality. For instance, someone may be illiterate but still involved in the collective effort to build a village school and pay a teacher so that the children can receive an education. What is shared is the valuation of the common benefit itself. Thus, a community that gathers around a social good is more than just a community of interests. It is not necessarily united by a correlation of individual interests, as social contract theories would have us believe. That is why the people who create the social good are not always, or necessarily, the same people who benefit from it. The community that benefits may be larger, or smaller, than the one doing the creating.

This is not to say that the common benefit need not be distributed fairly. When the hoped-for benefit is unduly diverted or appropriated by a person or group, people’s anger and indignation are reactions based on their sense of fairness. However, what is claimed is not necessarily one’s own share, but respect for the meaning of the social good in itself, i.e., for the value assigned to it by the community. It is the common nature of the benefit, linked to the shared recognition of its value, that is negated by undue appropriation. Returning to the previous example, if a local shopkeeper offers to rent an ‘unoccupied’ classroom as a storehouse for his goods, then takes advantage of this agreement to gradually turn the whole school into a storehouse, forcing the teacher to teach out on the playground, the community of people who have built the school and who pay the teacher will have been swindled out of their social good. They will feel robbed of the common benefit created by their interaction. They will claim that this is ‘unfair’! Not primarily because they are denied their ‘due,’ but rather because there is a conflict with the meaning and shared valuation of the social good. They will say, ‘we didn’t build a school for it to be used as a storehouse!’ It is the meaning of the social good—the school and the children’s education—that is diverted and then negated by the shopkeeper’s action. Being well aware of this, the shopkeeper will take good care to avoid claiming that the building is not a school, but will argue speciously that ‘he has a fully legal contract,’ that ‘the children can be taught in the open air anyway during the dry season,’ or even that the ‘whole thing is an emergency measure’ and that he will ‘soon stop using the premises.’ He will never say, ‘the building isn’t a school any longer—it’s my storehouse.’

So the social good can’t be detached from a ‘communality of meaning.’9 What this neologism means is that the social good does not only exist materially—in the school’s walls, tables, and chairs—but also as a meaning shared by the people involved in the interaction. The community that gathers around the meaning of this social good makes it exist as such, and imposes this meaning on anyone who seeks to misuse it. Therefore, an inherent feature of every social good is a community to whom it has a particular, normative meaning.10 This is what the village blames the shopkeeper for, and it is this meaning that the shopkeeper knows he has violated. And thus the villagers will reject the shopkeeper’s specious arguments ‘in the name of the common good.’

II. The Good of Order and the Common Rationality it Creates

When a number of people want to get something done, they organise themselves. The good we want to achieve together, the object of the interaction, will have to be planned. If we want to build a school, we need a site, plans, and funding; we have to persuade the families and children, find a teacher, and agree on the school timetable. To cooperate is to organise. There is no way to efficiently provide a certain social good without some immanent ‘good of order’ that organises our cooperation.11

This organisation of interactions generally involves determining the shared goal, each person’s status and role,12 and responsibilities in our interaction, and the rules that will govern our cooperation. The fact is that the ‘communality of meaning’ comes along with a specific organisation of the community, which, once internalised by people, is the shared rationality that makes sense of each individual action as part of the interaction. One person is responsible for finding and purchasing the future site; another draws up the plans for the school; masons supervise the volunteers who are to build it; and someone else will look for a teacher. Any interaction that seeks to produce a social good efficiently will necessarily produce a specific organisation, a shared rationality (ever more so when an interaction increases in complexity). This ‘good of order’ describes the organisation of a community so that it can achieve and then maintain a given social good.

The ‘good of order’ derives its raison d’être or its value from the object of the interaction, the social good it seeks to achieve. It therefore has an instrumental value, and its quality can be judged by: (a) how it coheres to the meaning of the social good; and (b) whether the good is achieved efficiently.

Finally, with the ‘subject,’ we describe a community that shares the same understanding of the social good. Each and every member of this group will have internalised the ‘good of order’ as the ‘common rationality’ of their interaction. Indeed, any given organisation—in order to be efficient—defines a set of standard statuses and rules that are rational in this specific context. Two chess players, for example, are bound by the rules of the game and the moves that can be made by the various pieces. They analyse their opponent’s strategy and devise their own on the basis of these rules. The rationality of each move on the chessboard depends thus on the logic of the game. The more the players have internalised this rationality, the more they will manage to play well and predict their opponent’s next moves. It is the logic of the game that explains the opponents’ strategies. However, just like the good of order, the value of this rationality is instrumental, and is assessed through its consistency with the social good and its ability to achieve it efficiently.

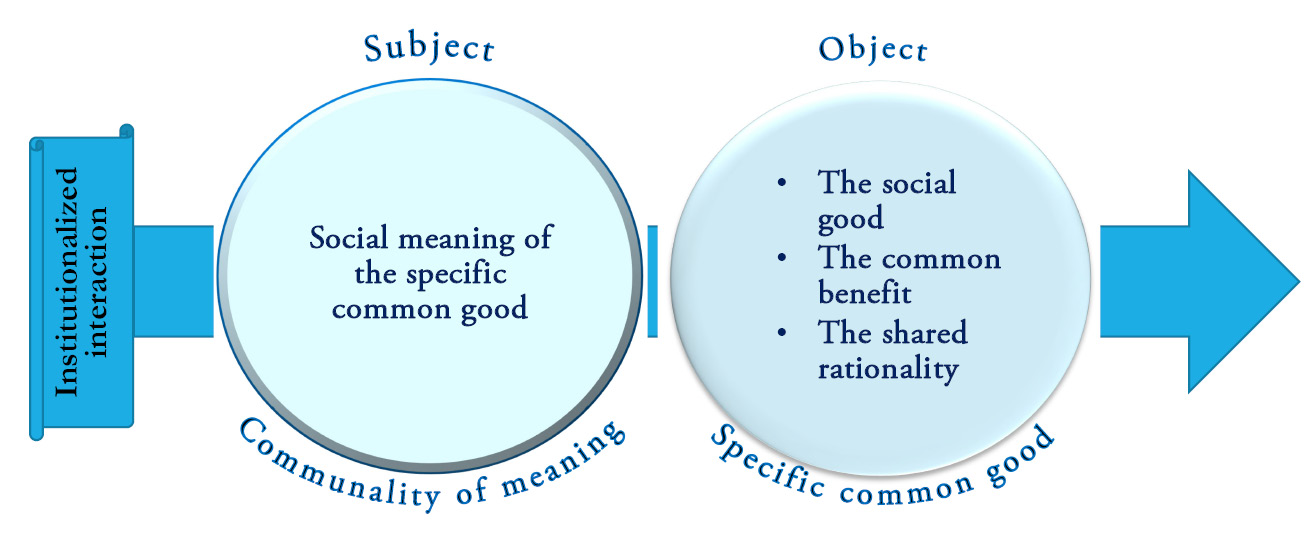

III. A Specific Common Good

Together, the ‘social good’ (communality of meaning), the ‘common benefit’ (shared valuation), and the ‘good of order’ (common rationality) form what I will call a ‘specific common good’ (the communality of a common good). The common good created by an interaction is made up of these three features: the ‘social good’, the ‘common benefit,’ and the ‘good of order.’ Correspondingly, the common good will be upheld by the subject as ‘shared valuation,’ a ‘common rationality,’ and a ‘communality of the common good,’ as Figure 2 shows:

Figure 2. The core elements forming a specific common good.

It is now time to bring up what I have thus far ignored for the sake of clarity. The subject and the object are held together in the dynamic of the action. The common good cannot be reduced to its objective dimension (the production of a social good), but nor can it be reduced to its purely subjective dimension (a communality of meaning and habitus).

The common good creates a social dynamic whereby a community exists and asserts itself. It is a specific community, as specific as the social good that gathers its members together. Let’s reconsider the previous example. Among the people of the village, there is a group who wanted to create the school and organised themselves to do so. This group is very specific. It enables the social good to exist and be maintained. Yet its boundaries are hard to draw. At the centre there will be a number of people who are clearly part of it: the parents, the teacher, the children. Further away, there will be those who helped to build the school and whose work for the project is now over, and even further away, the broad circle of those who support and approve of the project without benefiting from it or being actively involved in it. So the boundaries of this community are essentially the boundaries of the communality of meaning, that is, the meaning given by the community to the social good. In contrast, those who are not part of this community are those who, for some reason, can’t or don’t commit to this conception, and whose practical actions may conflict with the coherence of the common meaning—as the shopkeeper’s did.

Seeing the common good as a dynamic process also means that none of its embodiment can be considered as settled once and for all. To be preserved, the common good must be constantly reinvented over time. It is an interaction, and as we have seen, no interaction is spontaneous: it is the result of a certain communality of meaning and continuity of will. Thus, a specific common good will have to be readopted and reinvented by each generation if it is not to be lost and disappear—which also effectively means that the community gathered around a common good is not itself natural, but the result of a real sharing of a communality of meaning, which can easily be lost. Over time, the village in our story may become a nearby city’s smart suburb, whose children attend other schools. The village school, and what it once meant to the original population, would then gradually lose its meaning. Common goods may change or transform over time, which is only natural. But they will do so only if the meaning given to the social good radically changes.

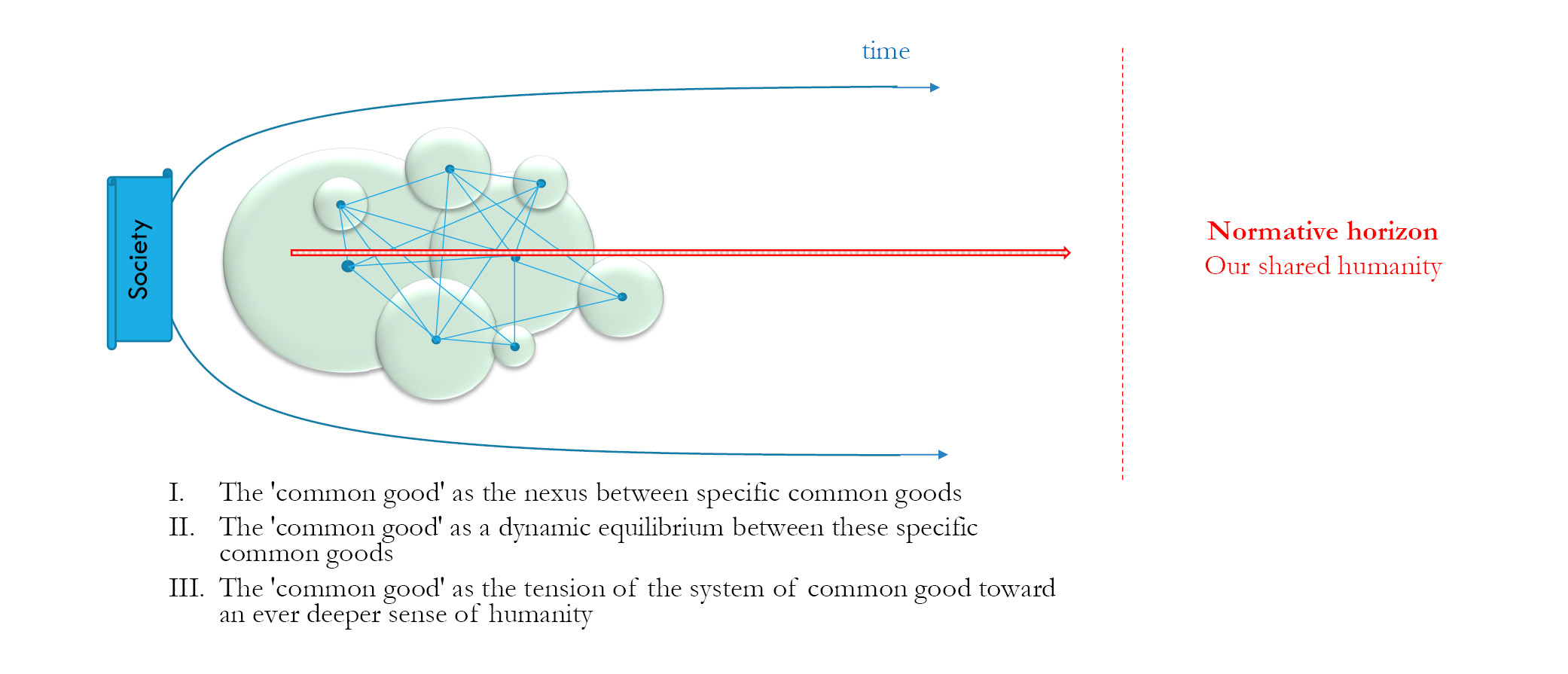

IV. The Nexus of Common Goods

It goes without saying that every society is built on an often very broad set of common goods that only partially overlap. There is a whole series of relationships between these specific common goods; most of the relationships are complementary, superimposed, and mutually reinforcing. This is not to say that all these specific common goods are uniform or equally important. There are tensions, or sometimes even contradictions, between them that make it hard for them to coexist within the same society. I will use the expression ‘nexus of the common good’13 to denote the real relationships between these various specific common goods in a given society.

Such a nexus does not appear of its own accord, as a kind of spontaneous self-organisation of society (Luhmann 1984, p. 15). On the one hand, it is the result of a shared history—centuries of common experience that have gradually brought various social goods together and created a hierarchy among them—and on the other, it is a result of the constant efforts of the present generation to reframe and to some extent reinvent them. This is a shared responsibility, a political task par excellence. A nexus of the common good results from exercising this political responsibility. That is why nexuses vary considerably in quality, with substantial gradations. Their quality partly depends on this shared history and partly on the present generation’s commitment and wisdom.

This commitment usually takes the form of a specific interaction seen as a particularly important social good: contributing governance to the ‘nexus of the common good.’ It is political power itself that is here valued and constructed as a common good, and one which is of crucial importance to any society. Indeed, the task given to governing bodies is to pursue an ever richer, deeper, and more inclusive nexus of the common good. Their task is to work out a real conjunction between the many specific common goods existing in the society, so that their nexus may be more humane.

Such a need for ‘collective wisdom’ appears frequently after terrifying or traumatic man-made events such as war, revolution, or genocide. The 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man, for example, emerged from a rejection of the structural injustice upon which the ancien régime was built. It was an explicit effort to learn to live by another standard of humanity. It encompassed and enshrined hard-earned wisdom about what it means to live together as human beings.

Now, we should not think of the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man as the ultimate expression of such wisdom. A document like this should be constantly reassessed and renewed by each generation, as indeed has been the case for the Declaration after the Second World War in 1948, and again in 1976. And this is precisely where wisdom comes back into politics. In my framing, the sole and purest goal of governance can’t be justice. The most pressing political question does not concern distribution, but rather coherence of meaning embedded in the nexus—the coherence of what it means to be human. We can summarise the point easily enough: does the nexus—in all its complexity—provide a social system where we can all live together as human beings? Or does this nexus only permit such standard of living for a restricted part of the population? Or even worse, does the nexus thrive by considering some of its population useless and redundant—the poor, for example? Even if this question obviously implies a notion of justice, it does start with an insight into what it is to be human. It starts with a wisdom whose legitimacy is only as strong as the collective experience that validated this ‘truth’ in the public square—war, genocide, systemic humiliation, etc. It starts, in other words, with an understanding of humanity as a shared, common humanity (see Chapter 5).

What is ultimately at stake in political governance is the humanity of our coexistence; no political entity can escape this question forever. As Aristotle said long ago, a polity, to be recognised as such, has to serve the common good.

Now, this wisdom is not formal. It can’t be enshrined in a declaration or a constitution. Real wisdom is linked to real behaviours. Along with authors as different as Bourdieu (1980), Giddens (1979),14 or McIntyre (2007, p. 187), we may recognise that social structures entail social practice, or, as Bourdieu (1980, pp. 88–89) would have it, collective habitus.15 These normative social practices are standard expectations of behaviours directly linked to the overall rationality of a nexus. These are the social practices needed to access and play along with the institutional framework of a society. They are objective and not a matter of individual choice. You can obviously disagree and reject them at a personal level; but not to follow them entails a cost not limited to public shame or underground culture. Being excluded from the basic social goods controlled by the nexus may be tantamount to death. Social goods like work, citizenship, or education are so important that the person will usually abide by the practices directing the work ethic, citizenship, or intellectual integrity in higher education. Not all collective habitus in a nexus are relevant to humanity. However, at a systemic level, there is no nexus that does not present a number of normative practices regarding the way we should behave with fellow humans in the nexus (outside of close family and friends).

Indeed, a frequent error is to believe that the nexus of the common good is a given, a natural state of affairs. On the contrary, the nexus is fragile and changes constantly. Its humanity is the result of a collective wisdom painstakingly acquired through history about what is more and what is less human in the organisation of society. It is always a patchy and imperfect wisdom. More often than not, a nexus will also carry some form of collective blindness to and tolerance of structural injustices. That is why its political governance needs more than legislators to determine what is just. It needs public actors who can assign a value to the coherence between many specific common goods, and understand their limitations and the tensions that both separate and unite them—in other words, public actors who endeavour to judge the moral quality of the nexus. This essential exercise of judging largely depends on the horizon of the universal common good.

Finally, it is important to underline that the nexus of the common good is what lends societal coherence to the communality of meaning. The communality of meaning is what binds together a society or a culture, providing it with some degree of identity and unity—a fragile and dynamic identity, to be sure, but an identity nonetheless. Perhaps even more importantly, the stability and resilience of the nexus derives from its quality (see Chapter 10). The richer in connections and more coherent the nexus is, the better it will be able to withstand shocks and reinvent itself. The poorer and more superficial it is, the more blindly it will focus on its supposed identity, and the more likely it is to be destroyed when confronted with a different social ethos (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. A nexus of common goods.

Using this vocabulary, the next sections of this paper will attempt to explain the specific features of this nexus and its dynamic tendency towards the universal common good.

3. Aspiring to the Universal Common Good

Arendt (1983, pp. 175–176) famously stated that human freedom crafts itself into being through action. Freedom of thought—this utterly internal freedom—only becomes historical to the extent that it is expressed in history, shaping its human environment through its radical novelty (Ibid., p. 177). Freedom that rejects action is freedom that rejects itself. To Arendt, freedom only achieves the radical novelty it carries insofar as it engages in action. Action is thus the place where human freedom is actualised and comes to fruition.

That is why, to Arendt, political society results from action (Ibid., p. 199). It is born of shared action, free interaction between human beings. A polity is not the result of a sum—an aggregation however complex of individual acts—but rather the interplay of these actions as they produce an environment, a sphere in which each action is not only recognised as achieving a utility, but as the revelation of a thought and a freedom (novum). What she calls politics is thus the only space in which human action is recognised as human through its involvement in social interaction. Politics is the space in which an agent’s action is recognised; the space in which the various agents’ inputs construct a common world whose primary feature is humanity: accepting the fragility of humanity, making it possible, deepening and continuing it. In Arendt, this recognition does not initially assume the form of law, which remains formal. This recognition is only real where the interaction directs and develops it (Ibid., pp. 230–235). Thus the humanity of society is not so much to be sought in the various meta-discourses that supposedly legitimise it,16 but in the very specific way that interactions operate and favour a real, present recognition of our common humanity.

The paradox of society is that, born of possible cooperation between freedoms, born of deliberate interactions, it is constantly undone by the conflicts that undermine it. Conflict and violence are so co-extensive with society that they may be considered as the primary evidence of political philosophy. This is the whole Augustinian current of thinking, which sees in the power of political authority the necessary remedy for the violence that original sin induces in social relationships (Gilson 1954, pp. 47–80). It is on this skepticism that British philosophers, at the dawn of the modern age, based their view of the need for state power. As Hobbes saw it, the natural and insurmountable conflict of individual passions required a Leviathan state that would mandate prioritising the general interest over private interest. This, supposedly, is the price to be paid for a minimal threshold of peace, justice, and wellbeing to exist. And yet the vitality of society and its continuous historical reinvention bears witness to something different. It displays a deeper truth than conflict and violence as the basis of a polity. It bears witness to a hope: the hope of a possible and real conjunction between personal good and the good of the community. In other words, the hope is that my good and your good are not forever in opposition, but will eventually enrich each other. It is the hope that my good and your good are augmented by each other, as our freedoms do not so much clash, but empower us both. This hope that our freedoms are not ultimately diminished by that of the other, but augmented and enriched, drives the search for the common good (Nebel 2007, pp. 217–232).

By no means does this hope deny the conflict inherent to social relationships. What it refuses is to posit violence and war as the basis of the polity (Rousseau). An anthropology of the common good states that even though conflict exists, it is no more ‘natural’ or ‘original,’ or even more dominant, than the hope for the common good. Rather, such an anthropology states that the incompatibility that frequently arises between the private good and the good of the community will be one of the specific features of the search for the common good. To desire and aim for the common good will thus be marked by conflict; and this is why the hope of the common good must be backed by a will for the common good in order for it to be achieved. This is also why any historical achievement of the common good is but a transient stage of an ever-ongoing process.

Always specific, the will for the common good will also be limited by time and space. And hence, because it excludes from the achieved good the people who are beyond the boundaries of the interaction, any achievement of the common good will always be partial and will always entail a potential conflict linked to its very limitations. The common good is thus a dialectical concept17 whose horizon is the hope of a future humanity in which each person’s good would finally coincide with the good of all (Arendt 1983, pp. 305–308). This is why the hope of the common good is ultimately based on a transcendent hope: that of an eschaton of human history in which the good of the whole of humanity would coincide with that of each of its members. The hope of the common good thus depends on a belief—secular or religious—in the eschatological advent of a reconciled humanity.18 The political conviction at the root of a common good approach may thus be framed as believing that the unity and solidarity of humanity can be real and possible.

Reclaiming Aristotle’s statement in the Politics (1979a), we may thus recognise the common good as the overarching goal of any polity. As a hope and a common endeavour, our shared humanity is the core of this goal. In other words, wanting to live together is not just a matter of wanting to survive, but of wanting to live well (Ricœur 2001, pp. 55–67). The good life—the hope of a future humanity in which each person’s good would finally coincide with the good of all—is the normative horizon founding the aspiration to the common good. Without this hope, the conflicts that mark the pursuit of the common good could no longer be seen as part of an ascending dialectic, but as evidence that pursuit of the common good is irrational. The obstacles to the broadening of the common good could then finally exhaust the hope that drives political action, for, once the dialectical pendulum is broken, the hope that dwells in the will to live together would seem little more than a naïve illusion or a theological relic from which we should be ‘brave’ enough to break free. ‘Political realism’ then withdraws to a minimum: limiting conflicts, preserving public order and peace, maintaining the rule of law. Yet the hope of the common good is constantly reborn, over and over again, and no historical failure seems able to destroy it. Though defeated, conquered, and bruised, it is always reborn. The hope that drives social action is invincible—and this is the paradox! The common good is not just any hope; it is the eschatological horizon onto which all political action is projected. Therefore, a reinterpretation of the common good must, in my view, account for this paradox driving the political dynamic.

4. The Common Good as the Dialectic of Politics

I have identified the elements of the common good, and mentioned the hope that dwells in its pursuit; but I have not yet specified the nature of this hope. This final section will attempt to do so.

I. The Conjunction of the Individual Good and the Good of the Community

Historically, the concept of the common good refers to the relationship between the good of an individual and the wider community to which he belongs. So it is not a particular good that is fixed and determined once and for all, but the dynamic coincidence of two or more goods that fluctuate over time.19

It is an interaction that combines these two goods, for every interaction is simply the organised collaboration between different freedoms, united around the achievement of a given social good. It is people who collaborate in the intention and creation of a social good; it is people who share a common benefit and a certain practical rationality derived from the good of order and therefore find their own good in this collaboration. The social good that they produce together is thus both the good of all and the good of each one of them.

Here we must bear in mind how profoundly our thinking is marked by materiality (Bergson 1896). We spontaneously think about sharing a good as if what is obtained by one person is lost to another, as if we were sharing a biscuit. But the material element of social goods is only part of what is shared, and not the most important part. Of course, interaction does usually produce a material, tangible good, but its creation, and even more so its existence, depend, as we have seen, on a communality of meaning: a common intention and will, a common benefit and communal rationality. All of these elements are intangible, but still real. And the sharing of intangible goods is marked by the fact that what is given to one person does not diminish what others receive. On the contrary, a broader distribution base, to a greater number of people, tends to increase the total good. The classic example is a mother’s love for her children. The birth of another child does not reduce her love for the previous ones.

The expression ‘basic social goods’ is used in development literature to designate the minimum goods that should be available to all, such as food, housing, safety, and all the fundamental human rights.20 Each of these basic social goods is what is referred to in this book as a specific common good. What my analysis adds to this literature is first an understanding of all the intangible elements that structure the actual existence of these goods, and second, a focus on the social process through which they exist. The lasting creation of a ‘basic social good’ depends on the existence of a communality of meaning. None of these goods—decent work, formal education, adequate housing or the right to food—can be created on a lasting basis unless they are collectively seen as common goods that we want to create together.

Indeed, it is clear that even in the case of food the problem is not merely a question of production. Of course, in a famine there may be a real shortage of food; but, as Sen (1981) has pointed out, famines are not so much due to the lack of food as to the lack of will to distribute it to everyone. It is rare to have food crises under democratic regimes. What prevents the implementation of the right to food is the widely held belief that food is only a private good. Ultimately, it is because there is no communality of meaning surrounding the notion that no one in a community should die of hunger that some people still do. Food production and distribution is organised on such a fundamental consensus.21 This is even truer of education, in which the distribution of the intangible element—knowledge—does not involve any reduction of shares. Teachers do not lose or forget what they impart to their pupils; on the contrary, their knowledge is enriched by being passed on to others.

It is because common goods are essentially intangibles that the good of the individual and the good of the community can overlap in interaction. One person’s good increases another’s, even though it is shared.

II. Wanting the Common Good

This conjunction of individual and community, even though it is an intrinsic part of our social condition, does not occur without us. We have to want the common good. We have to work out how it must occur, and can occur, in the present circumstances. We have to work at wanting to live together, in order to maintain, reinvent, and increase the common goods around which we gather together as a community. Although already found in their most basic forms within the family, clan, or ethnic group,22 actions for the common good are bound to become increasingly conscious and free, i.e., political (Sherover 1991, pp. 55–60, 89–90). It is this process—this common good dynamic—that must determine which goods unite us, which ones we want to create together, and how to design, share, or distribute them.

But since the conjunction achieved at the level of the nexus must be wanted and given the fact that different equilibriums between specific common goods may be possible, this conjunction should be the central object of political deliberations. We must discern exactly what the conjunction consists of, what it requires in the present circumstances, determine the goods that bring us together as a community and what we want to promote in common (for example, appreciation of common goods, formation of hierarchies, coherence, resolution of conflicts of meaning/production/distribution). The forms that political agencies of deliberation and decision-making take are many, but in contrast to the now prevailing idea, democratic institutions are not the unique or even prevalent source of this order of the common good. More often than not, democratic governance does not invent, but inherits, the order of the common good and is only called on to frame and develop it.

Take customary law, which in all civilisations is one of the oldest forms of the common good nexus. The reciprocity of customary rights and duties organises a community. Custom coordinates individual goods with the good of the community, preexisting positive law formulated by a legislature. The order of the common good is thus primarily a practical matter, and its political dimension only emerges gradually. The same applies to the executive, which in the vast majority of cases is in much more of a position to manage the nexus of the common good than to create it. The daily bread of the executive is to assess and settle the many possible conflicts emerging between individual good and that of the community. The origin and then the slow flourishing of the nexus of the common good thus escapes the republican ideal: that of an omnipotent, sovereign assembly that decrees the form of the state, decides the general interest, and promulgates a constitutional order. The fact is that these decisions are not usually the result of an assembly, but of far longer processes, age-old experiences that form the wisdom of a people and ground its political culture. That is why a common good approach, while acknowledging the important role of democratic governance, does not reduce governance to a parliament or state bureaucracy.

III. The Dialectical Dynamic of the Common Good

Yet the quality of different nexuses of the common good may vary significantly. Some will be more human, others less human. Some will be organising the social relationship binding us together in a more human way, while others will be degrading it with violence, injustice, and oppression. Not every nexus of the common good is equally valuable. Some are basic, reduced to the simplest common goods; others are more complex and, like modern society, include many specific common goods. Yet it is not complexity that determines the quality of the nexus of the common good, but the quality of the relationships it creates between people. The freer these relationships, the more they will enhance our dignity. The truer they are, the more universal they will be. The more they are focused on values of the spirit, the more they will be able to accommodate our desires for the good life.

Deepening and broadening the common good often involves a paradoxical stage in which the quality of the previous nexus is lost in order to broaden its base. The lost quality will then have to be reconstructed among this broader base of people. But this is a perilous undertaking that may also fail. Without the lost quality, the new equilibrium may be worse than the previous one. Aiming for the universal common good takes thus the form of a dialectic. Its progress is not linear. Any deepening or enlargement will come at a cost and will trigger resistance. Creative destruction can’t be totally avoided. It is part and parcel of the progress of the common good dialectic.23

The construction of Europe is a good example of a common good dialectic. It began with a wish to integrate Europe’s various countries, i.e., to broaden and deepen the nexus of the European common good. The attempt to do so is remarkable, brave, and makes sense. It responds to the call of the common good. But will it succeed? The question remains entirely open. European integration was first seen in terms of economic integration, the free movement of goods, services, and people through a single market. But such integration is only one aspect of the common good—the creation of economic wellbeing—and it is quite clearly insufficient. Everyone is aware of this: the quality of the nexus of the European common good cannot be reduced to just an economic good. The difficulty is that the pursuit of integration, the deepening of a nexus of the European common good, entails transferring sovereignty to the European Commission and the European Parliament. It is the very nation states involved in integration that are putting the brakes on and rejecting it. The success or failure of Europe will depend on nation states’ ability to forge a European nexus of the common good of a quality similar to those they have created at the national level. If in the long term the quality is not the same—or, worse, if European integration reduces the quality of national nexuses of the common good—it is a fair bet that the democratic process in some countries will encourage a nationalist withdrawal, wreck the European project, and contribute to the slow decline of the various national nexuses.

Indeed, every determination of the nexus of the common good is historical, and hence incomplete and unfinished. First of all, the nexus is dynamic, and the equilibrium achieved in recent decades cannot claim to respond to all future challenges. Populations change, economies are transformed, technologies develop; and the nexus of the common good must respond to these changes. Second, the size of the reference community varies and tends to keep increasing. The common good of a family is not that of a nation, or of the whole of humanity. The nexus of the national common good is too narrow to cope with the various processes of globalisation. The national nexus must expand, for many of the interactions of the nexus are nowadays beyond the governance of the nation state, like the regulation of transnational corporations, financial flows or CO2 emissions. If the dynamic of achievement of the common good tends towards universality, it is not just with reference to a moral imperative, but also to a gradual movement towards global integration of communities (Hollenbach 2002, pp. 212–229).

If every historical determination of the common good is never more than partial and incomplete, destined to be revised and transformed, and if every achievement of the common good is characterised by conflict, we can only say that what drives the wish for the common good is hope—hope that this conjunction of the individual good and the good of the community is possible and will one day be real. This hope is at the root of politics and political commitment. Should it ever be lost, the community will collapse. If the hope of the common good disappears, the institutions that make up a society can, depending on their resilience, do no more than delay the gradual dissolution of the nexus.

Conclusion: The Quality of Common Good Dynamics

Let me conclude this chapter with something that will be developed more thoroughly in the next one. One key open question is that of whether we can assess the quality of the nexus. Can we? The complexity of a social system is enormous. Can we really think that we may be able to assess the quality of the common good dynamic in terms of humanity? It seems a daunting prospect at best, and at worst a hubristic and morally dangerous endeavour.

However, even the most unsophisticated person knows for sure that some nexuses are undeniably more human than others. It is obvious to any refugee: poverty, oppression, injustice, persecution, and war make for a less human nexus than peace, wellbeing, justice, rule of law, and political freedom. Why can’t academics understand what any refugee knows for sure? This book tries to formulate an answer. Can we find some normative anchors that may work to assess dynamics of the common good?

We noted in the previous section that nexuses are dynamic equilibria moving toward an ever deeper and broader humanity: a humanity we described as -embedded in the collective practices or habitus that govern the relationship to others in this nexus. This means basically two things. First, that the main normative anchor will be humanity, not a formal humanity acknowledged through rights and duties, but a real one, embodied in the practices that define our coexistence. Humanity describes the overall direction, or the compass indicating the North Pole of common good dynamics. Second, if a nexus is a dynamic equilibrium, we may also identify some permanent features required for the equilibrium to move toward more humanity. The next chapter will propose that we recognise four such drivers of common good dynamics, namely: agency freedom, governance, stability, and justice.

We could also think of a minimal threshold of basic common goods inherent to any nexus of the common good, including for example culture, solidarity, education, the rule of law, etc. While the drivers refer to the dynamic of the equilibrium as it moves toward humanity, an inexhaustive list of basic common goods might describe the core elements needed for any sort of nexus. Such a list would include common goods deemed so essential to human society that any nexus that does not include them would be considered below a minimal threshold of humanity. The next chapter will describe each of these elements and present a matrix of common good dynamics.

References

Arendt, H. 1958. The Human Condition, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Aristotle. 2009. Politics (trans. Barker, E.), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bergson, H. 2012 (1896). Matière et mémoire, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Blondel, M. 1893. L’action, Paris: Alcan.

Bollier, D. and Helfrich, S. 2015. Patterns of Commoning, Amherst: The Commons Strategies Group.

Bourdieu, P. 1980. Le sens pratique. Paris: Editions de Minuit.

Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fessard, G. 2015 (1944). Autorité et bien commun, Paris: Ad Solem.

Friedberg, E. 1993. Le pouvoir et la règle. Dynamique de l’action organisée, Paris: Seuil.

Giddens, A. 1981. A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism, vol. 1, London: Macmillan.

Giddens, A. 1979. Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, Structure and Contradiction in Social Analysis, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Outline of the Theory of Structuration, Cambridge: Polity.

Gilson, E. 2005 (1954). Les métamorphoses de la cité de Dieu, Paris: Vrin.

Herrera, A. O. (ed.) 1976. Catastrophe or New Society? A Latin American World Model. Ottawa: IDRC, https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/213/IDL-213.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Hibst, P. 1991. Utilitas Publica—Gemeiner Nutz—Gemeinwohl, Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Hobbes, T. 2014 (1651). Leviathan (ed. Malcolm, N.), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hollenbach, D. 2002. Christian Ethics and the Common Good, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606380

Jehne, M. and Lundgreen, C. (eds) 2013. Gemeinsinn und Gemeinwohl in der römischen Antike, Stuttgart: Steiner. https://doi.org/10.1515/hzhz-2014-0343

Kempshall, M. 1999. The Common Good in Late Medieval Political Thought, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Luhnmann, N. 1984. Soziale Systeme: Grundriss einer allgemeinen Theorie, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Machiavelli, N. 2008 (1532), The Prince (trans. Bondanella, P.), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McIntyre, A. 1984. After Virtue, South Bend: Notre Dame University Press.

MacIntyre, A. 2007. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. South Bend: Notre Dame University Press.

Mounier, E. 1949. Le personnalisme, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Nebel, M. 2006. “El bien común teológico: ensayo sistemático”, Revista Iberoamericana de Teología 1, 7–32.

Nebel, M. 2007. “Espérance et bien commun”, in Gavric, A. and Sienkiewicz, G. (eds), Etat et bien commun. Berne: Peter Lang, 217–232.

Nebel, M. 2013. “Action de Dieu et actions de l’homme”, Transversalité 128/4, 151–163.

Palmer, M. 1992. Love of Glory and the Common Good: Aspects of the Political Thought of Thucydides, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Ricœur, P. 1986. Du texte à l’action, Paris: Seuil.

Ricœur, P. 1990. Soi-même comme un autre, Paris: Seuil.

Ricœur, P. 2001. “De la morale à l’éthique et aux éthiques”, in Ricoeur, P., Le juste II, Paris: Esprit.

Riordan, P. 2015. Global Ethics and Global Common Good, London: Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474240062

Rousseau, J.-J 2009 (1762). Discourse on Political Economy and The Social Contract, (trans. Betts, C.), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. 1981. Poverty and Famines, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sherover, C. 1984. The Temporality of the Common Good: Futurity and Freedom, Review of Metaphysics 37/3, 475–497.

Sherover, C. 1989. Time Freedom and the Common Good, New York: New York University Press.

Sluga, H. 2014. Searching for the Common Good, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Von Rochau, L. 1972 (1859). Grundsätze der Realpolitik, Frankfurt am Main: Ullstein.

Walzer, M. 1983. Spheres of Justice, Oxford: Blackwell.

Weller, M. and Wolff, S. (eds) 2005. Autonomy, Self-Governance and Conflict Resolution: Innovative Approaches to Institutional Design in Divided Societies, Routledge: New York. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474240062

1 This tension is indeed forcefully presented by Thucydides in the Melian dialogue. See Thucydides 2010, paragraphs 64–74.

2 Public action has never been only conflict, subterfuge, and lies. On the contrary, a lasting community on a human scale—one that is able to welcome, recognise, and protect fragile human dignity—cannot be constructed on conflict, subterfuge, and lies.

3 I rely for this paragraph more on the French tradition than on the Anglo-Saxon one, more on Lévi-Strauss and Bourdieu than on McIntyre.

4 Similarly, archaeologists distinguish the advent of the first great Mesopotamian civilisations by their major agricultural works, their creation of law, their ability to make military plans, and their development of trade. All these features point to the importance of agricultural production, law, trade and security as specific social goods. Cf. Ostrom (1990).

5 This recalls the Arendtian conception of action as the vehicle of thought and the place where interiority is revealed to others—action that constructs the common artefact, action that constitutes the common world. See Arendt (1958, pp. 73–78, 175–188).

6 Ibid., 175–176. The object’s independence and otherness in contrast to the subject only apply to material objects. Most objects involved in a common action are immaterial: education, peace, stability. Although they have a material dimension, these goods are essentially common meanings that are inseparable from the subject that carries them out and the community to which they have meaning. It is in the action that creates it that the object will then be chiefly present on the stage—as an object being created.

7 This, of course, is the essence of Ricœur’s thinking about his notion of narrative identity (1990, p. 167).

8 We now have a series of modern studies of this history: Hibst (1991), Jehne and Lundgreen (2013), and Kempshall (1999).

9 Riordan (2014, pp. 83–96) proposes to understand the ‘common sense’ associated to a common good as one of its crucial elements.

10 To understand the distribution, we must therefore first understand the value given to the social good by the population. It is this normative meaning—shared by the population—that will be the base of the more or less equal distribution of the benefits, which is basically the central point made by Walzer against Rawls in 1983 (pp. 3–31). Now, regarding normative meaning, we do not refer to the discussion in analytic philosophy about the normativity of language, but to Ricoeur’s understanding of meaning as convening to action (1986, pp. 184–197). See also Sherover (1989, pp. 27–52).

11 This section builds on the old, scholastic notion of ‘good of order’, but revisits the notion through the sociology of organisation and social structures developed by Friedberg (1993) and Giddens (1984).

12 The status describes here the powers, duties and responsibilities attributed to a position in the interaction while the role refers to the way a specific person enacts this status. The first is unpersonal and refers to a position in the interaction, for example the striker in a soccer team. The second refers to a person, acting as the striker of this team. Following the example, not every striker has the genius of a Diego Maradona or Lionel Messi.

13 Rather than the terms ‘network’ or ‘web’—now overused because of the Internet and globalisation—I prefer the Latin term ‘nexus’, which means ‘relationship, intertwining or linkage of causes, connection, bond,’ a term linked in Roman law to that of responsibility or duty. It is derived from the verb nectere, which means ‘to tie together, to unite, to link.’

14 Social structures are for Giddens dual in the sense of ‘both the medium and the outcome of the practices which constitute social systems.’ See also Giddens (1981, p. 27).

15 Bourdieu develops a rich understanding of the duality existing between social structures and practice. To quote his impossible French, habits are for him a « système de dispositions durables et transposables, structures structurées disposées à fonctionner comme structures structurantes, c’est-à-dire en tant que principe générateurs et organisateurs de pratiques et de représentations qui peuvent être objectivement adaptées à leur but sans supposer la visée consciente de fins et la maîtrise expresse des opérations nécessaires pour les atteindre ».

16 Ibid., 294 ff. Although Arendt does not use the term ‘meta-discourse’, she lays the groundwork for analyses such as Foucault’s of the relationship between truth and power.

17 Fessard (1944, pp. 96–98) is the one that identified the dynamic of the universal common good as a dialectical dynamic. Unfortunately, his Hegelian reinterpretation of the common good has widely been overlooked by the Anglophone literature on the topic.

18 The introduction of this historical tension into the notion of the common good is specifically Christian. See Hibst (1991, pp. 144–157).

19 Writing from a different perspective, Hans Sluga arrives at the same conclusion. See Sluga (2014, pp. 231–250).

20 A basic needs approach to development was proposed by the Bariloche Foundation in 1976 and adopted later on by CEPAL, the UN, and many other organizations. Cf. Amilcar et al. (1976).

21 Recognition of the right to food as a human right is a first step towards the recognition of food as a common good. But in terms of the nexus of the common good, this human right clashes with other requirements, especially legal and economic ones. This goes to show the complexity of this nexus, and why political governance is so essential.

22 The conjunction of the common good is based on a certain logical and empirical correspondence between the existence of the individual and the existence of a community. The existence of an individual is always a social existence. This is self-evident in practice; it can be challenged in theory, but not in terms of action.

23 Fessard’s Hegelianism is but the translation of a much older, theological intuition of the patristic era: the movement of the common good is essentially that of God’s Spirit or Charity leading humanity toward its ultimate reconciliation with the Father in Christ. Thus, its movement necessarily involves a kenotic moment (2015, pp. 96–98). The cross is not a part of a reconciliation that can be avoided altogether. This idea of a kenotic moment is not exclusively religious, however. Marx used it to frame the dialectic struggle between capital and labour.