3. Design and Reflection on the Metric of Common Dynamics1

© 2022 Garza-Vázquez and Ramírez, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0290.04

Introduction

Development efforts are increasingly challenging as the world becomes more complex. The interconnectedness of peoples and economies, the diversity of cultures, and the endurance of global development issues demand more than ever approaches that are able to capture this intricacy and multidimensionality both at the global and local levels. In the search for such approaches, development indicators have burgeoned, contributing to the monitoring of the progress of societies and the effectiveness of policy and public decision-making in the last decades. However, most of these efforts focus on measuring progress at the international and the individual levels, overlooking the collective production of progress by people acting together in local contexts. The Institute for the Promotion of the Common Good (IPBC) seeks to meet this gap by proposing a metric of common good dynamics at the municipal level that can capture the shared construction of social goods in order to guide local governments in their development plans.

Although there seems to be a growing interest in moving beyond individualistic narratives, few approaches have ventured to create measures on relational or collective processes. In addition, as explained below, the focus of these approaches either remains at the level of outcomes or considers a particular dimension in isolation. Instead, the metric presented here adopts a systemic approach within process-oriented dimensions. As such, the contribution of the metric offered here is that it captures the quality of the nexus of the common good by analysing how the structural and dynamic aspects of the production of common goods combine to build a society that lives together. The structure of the common good comprises the way in which the social and institutional context in the municipality frames people’s opportunity to live well and to achieve collective goals, while its dynamics involves the expected patterns of behaviour in which the residents act in the production and distribution of the basic common goods of a municipality over time. The metric examines these aspects of the nexus of the common good through the interconnection of five dimensions: Justice, Stability, Governance, Collective Agency Freedom, and Humanity.

This article introduces the metric of the common good proposed by the IPBC research group and discusses the steps taken in the construction of the seventy-one indicators that comprise the aforementioned five dimensions, the advantages of this perspective, and the remaining challenges. It is structured as follows. The first section summarises and comments on the pertinence of the common good approach proposed in this book. The second lays out the process of constructing the indicators. This was primarily a dialectic process between experts in the theory of common good, measurement specialists, and local government officials and political actors knowledgeable in the local challenges of the municipalities. This section also reviews the qualities sought in the items as they were designed, as well as the challenges faced. The third section presents the dimensions and the items that comprise them, delineating the specific aspects of the dimension that each item seeks to capture. Before the conclusion, the fourth section discusses the metric’s contributions and future challenges if it is to be used to guide policy and decision-making at the local level.

1. The Theoretical Foundations of the Survey

Measuring is never done for its own sake. The collection of data is necessary in order for us to keep track of the evolution of those things that we care about. It provides us with information about how we are doing, whether we have advanced, and how much more we can achieve. As Székely’s (2005) book title states, numbers also move the world; what is measured can be improved. In addition, data allows us to infer things that are beyond our own sight. By learning about how different variables connect with each other we can better understand the world in which we live. We can also learn about some realities which have been ignored by current metrics and of whose complexity and avenues for improvement we have little knowledge. Yet, developing measurements is no simple task. It is always imperfect, and it is always value-laden. Hence, the best one can do is to try to measure what really matters based on people’s realities and a sound theoretical framework, and to be transparent about the choices one makes in this process.

Previous chapters in this book have introduced the theoretical foundations of the metric of the common good presented here (see also Beretta and Nebel 2020, Nebel and Arbesu-Verduzco 2020). These chapters offer a rationale for the development of a practical measure of a common good approach as a necessary practical tool to complement existing metrics of ‘social’ progress. As mentioned, most of these ‘social’ indicators rely on aggregated individual data as a proxy for the social, and thus they fail to account for the systemic interactions, that is, the interconnection between the common institutions, values, and shared practices underlying the production of individual results. Instead, the matrix of the nexus of the common good aims its focus ‘on commons’, that is, on those things that we value, produce, share, and benefit from, as a collectivity. Likewise, as opposed to these measures, the metric developed here focuses on ‘the process by which these [collective goods] combine in society to create a nexus–of–commons’.

This move is a major contribution to the conceptualisation of development and to the design and evaluation of social policies to improve people’s lives. It responds to the urgent need for measuring things that have long been left outside of our modern conception of development and wellbeing, namely the structural and relational aspects of development, in order to place them in the academic and political agenda.

For a long time, we have given too much importance to what we measure (just because we can measure it) instead of measuring what is important. Indeed, some still justify the use of GDP as a measure of social progress due to its simplicity and its apparent exactitude. Yet, even if we assume that GDP indeed offers a precise measure, we may still ask whether it measures the ‘right’ thing.2 In the last thirty years, we have seen great advancements in terms of indicators going beyond GDP. Most of these emphasise the need to focus on what really matters, namely, the person and her wellbeing. Nowadays, we know that a GDP measure is simply insufficient (even if necessary), and not the most important indicator of the development of societies, as it does not capture what we truly care about, i.e., people’s quality of life. In response, several efforts to measure people’s wellbeing have emerged (e.g., Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index, the Human Development Index, Italian BES, and others). Even if measurements differ, the great majority of them coincide in insisting on the complexity of people’s lives, and thus defend the use of multidimensional indicators to assess social realities, and to inform the design, monitoring, and assessment of policies.

This has signified a huge improvement in more directly measuring the relevant dimensions of people’s lives. Now, besides income, we have information about health, education, standards of living, and so on. This has also translated into improved poverty measures which now provide a more realistic picture of the many deprivations people face when in poverty (e.g., see the Multidimensionality Poverty Peer Network, www.mppn.org). However, there are also some problems with these measures and with how we interpret them. These issues amount to the fact that these measures rely on the aggregation of individual data, and the fact that we tend to wrongly assume that they are the only thing that matters. Indeed, we have come to use these multidimensional measures of individual wellbeing as a new substitute for the supremacy of GDP, as if they were the only relevant information capable of informing development policies. This has the unintended consequence of dismissing as unimportant other features that do not appear in our statistics, even though these are crucial for an integral notion of development and for combating poverty effectively. With the transition from GDP measures to various forms of aggregation through individual wellbeing measures, we have ultimately removed the person and her experience of life from the social context in which she is embedded and in which her wellbeing is co-constructed.

It is in this sense that, by emphasising the dynamic processes and the socio-structural aspects of development, the common good approach proposed in this volume makes an important contribution. It asks us to reinterpret and broaden the way in which we read the success or failure of social life in at least two areas.

First, it recognises that the processes through which a society generates its outcomes in terms of individual wellbeing are also relevant to our lives. That is, it is not enough to know what kind of functionings people manage to achieve. We also care about other things such as the social arrangements in which we live, people’s collective freedom to exercise their agency and responsibilities in society, and the humanity of the processes to achieve them, as these are all part of the complex social dynamic in which we live, and which informs our behaviour. While these concerns are not unique to the common good approach presented in this edited volume, our approach does go further, since these structural aspects are understood as an inherently connected, systemic whole. That is, rather than treating these aspects as isolated dimensions that form part of the development process (e.g., measures of Rule of Law), they are seen as working in a nexus. Justice, for instance, cannot be fully understood without reference to agency freedom, the quality of governance, and so on. Precisely how the latter dimensions (Collective Agency, Governance, and others) work in harmony with others determines how we address justice concerns. It is the quality of these interconnections that the common good approach sets forth, through a matrix of five dimensions—as further explained below. The common good approach does not focus on the function of legal and legitimate authority alone, but also on the total community dynamics within a territorial demarcation.

Secondly, it shifts our concerns from static end states of individual functionings to actual dynamic patterns of behaviour. The common good approach’s primary concern is action rather than accomplishments. As such, it diverts its focus from what people achieve and the quantity in which they achieve it, towards what people—in conjunction with others—actually do in order to achieve whatever they value, and how. Ultimately, it is people’s practices and their social interactions that provide us with a richer understanding of the quality of the social development actually experienced by the members of a given community. For instance, from this perspective, to understand the situation of health in the population would imply focusing on whether shared values, goals, and practices lead people in a given community to be healthy, as opposed to measuring only the actual health of each individual (which would disregard the social context in which the results of such a study were produced).

Overall, this stance encourages us to realise that many (if not all) of the things we value, such as agency, humanity, dignity, and other fuzzy concepts, do not reveal themselves dichotomously in our lives. These are not something you either have or do not have. Rather, they are states which are constantly being negotiated and co-constructed in conjunction with others. Therefore, a common good approach affirms that the experience of being agents, of living in a humane way, and so on, can be better appraised through a gradient scale at the social level (i.e., by measuring the extent to which these aspects are present as practices in a given population) rather than as an on/off condition that can then be aggregated for the population as a whole. In fact, both individual and social achievements are sustained by the recurrence of practices in society, rather than being an on-off condition of individuals within society. Hence, the problem with most measures of social progress focusing on outcomes is that, although they can tell us something about people’s wellbeing or agency, for example, the resources that people possess or their internal abilities to make choices (e.g., income, ownership of resources, literacy levels, self-esteem), do not reveal anything about the vitality of practices, nor the extent to which those practices are spread across the population, nor indeed their permanence in the near and distant future.

In sum, a metric of the common good dynamic reveals the fact that although the person and her wellbeing are a central part of development, this is not the only concern, as it does not provide the necessary information to tackle the systemic problems we face in the modern world. Operationalising the common good as a nexus, therefore, makes us move beyond individualised, static measures to appraise the dynamic process through which we generate, share and enjoy common goods (including individual enjoyments).

This metric seeks to move beyond a simple description of the state of things (in terms of individual access to education, health, etc.), to allow us to say something about how these outcomes are generated. For example, obtaining a desirable outcome through a desirable process that respects human dignity and freedom, is not the same as doing so by means of an undesirable and disrespectful process. Simply stated, we could arrive at similar results in terms of individual levels of wellbeing through very different social dynamics. Therefore, we need to be able to discern between desirable and undesirable development processes, just as we need to know why desirable outcomes are not attained in certain contexts. We need to assess people’s behaviours and the processes and social structures in which their actions take place, and understand how these—together—result (or not) in a common good dynamic, in the hope of a freer, more human, more just society. The challenge is to encapsulate this process in a metric. This is precisely the task that the IPBC has set itself, and the subject of our discussion in the following paragraphs.

As has been argued in the previous chapters, and as the metric will show, the questionnaire seeks to capture information through the expected social practices and expected patterns of human behaviours. This is motivated by the idea that every person is deeply embedded in a social context with specific rules that structure their actions and interactions. These socially recognised patterns of behaviour that coordinate our social interactions inform us of whether a particular social dynamic promoting the common good (or a common bad) is being reinforced or transformed. Indeed, when we think, act, and choose, we are not only deciding our way of life, we are also reproducing or confronting social structures that—partly—determine and validate our actions and the processes by which we do things in our common social life (see also Chapter 4). It is through our shared actions with others that we produce, procure, and experience common goods. As such, the metric aims to inform how institutions, behaviours, and groups interact with one another to constitute a nexus of the common good. This will be a necessary tool for informing policies through a more comprehensive view of social dynamics, with the aim of a flourishing community and flourishing individual lives.

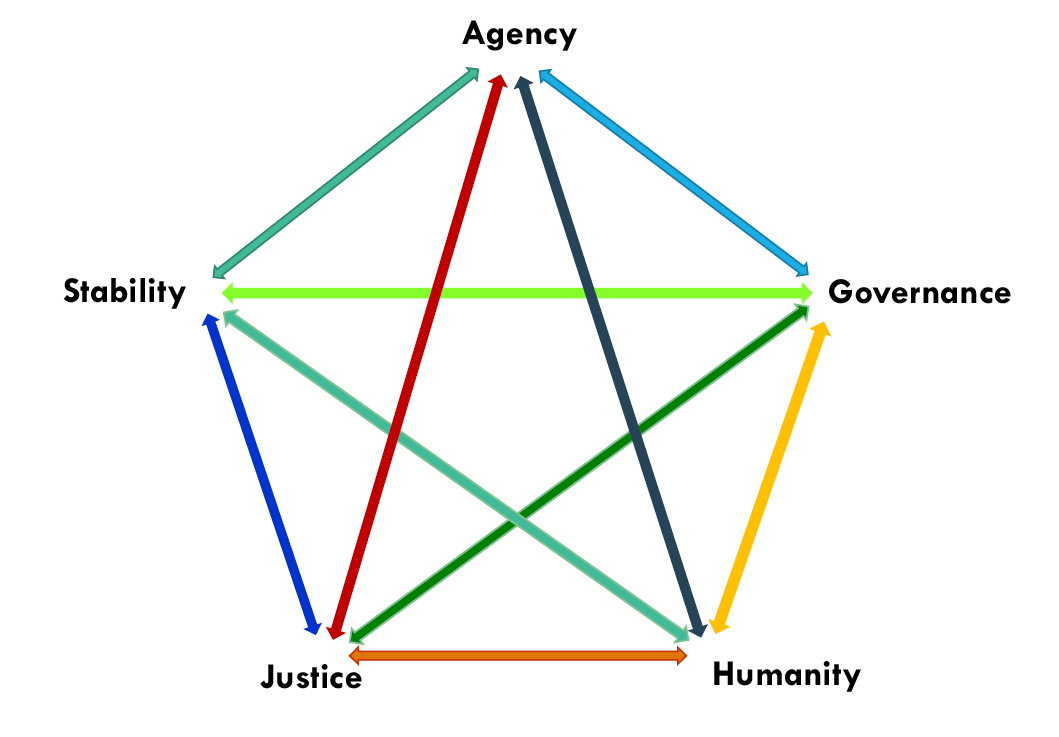

The IPBC’s team proposes to capture the collective dynamic processes and their interconnectivity through the matrix reproduced below (Figure 1). The model identifies the five normative dimensions deemed minimally necessary for the production of common goods at the local level. It also illustrates the fact that accounting for the presence or absence of each of these dimensions alone is insufficient; for the common good is the systemic outcome resulting from the quality, strength, and density of the interactions between these dimensions—rather than the simple results of their aggregation as separate phenomena. Therefore, the matrix envisions the nexus of the common good as the dynamic resulting from the combination of and interactions between each of these dimensions.3

Figure 1. The common good pentagram. Source: Nebel and Medina (in this volume).

2. The Design of the Survey

Anyone who has designed a survey or collaborated in the process knows that it is no easy task. There are too many considerations to take into account in order to stay as close as possible to the original intention of the theoretical framework. Even apparently unproblematic features, such as the wording, response options, and order of questions in a survey can affect the quality of any metric (e.g., Kelley et al. 2003; Brown 2009). Therefore, our metric went through a careful design process, which we can map in relation to recommendations from the literature.

The construction of the items was primarily the result of an iterative process undertaken in consultation with a number of experts to reflect on how we could operationalise the notion of the common good and to provide advice on the indicators produced. The IPBC, based at the Universidad Popular Autónoma de Puebla (UPAEP), together with other academic institutions, carried out a number of research seminars—Puebla (December 2017), Barcelona (23–24 May, 2018), Notre Dame (22–23 October, 2018) and Puebla (13–14 February, 2019 and 25–26 October, 2019). These meetings sought to bring together a diversity of perspectives, from academics, policy experts, members of civil society and local mayors who engaged in discussions about the conceptualisation and operationalisation of the common good at the municipal level.

In addition to these academic assemblies, individual meetings were held with key specialists such as Flavio Comim (May 2019), Clemens Sedmak (October 2019), and Gerardo Leyva (May 2019), as well as virtual discussions with a large group of academics that have made invaluable comments on the proposal. Finally, the formal production and refinement of the items was achieved through regular meetings of the core research team between March and October 2019. The purpose of these meetings was to integrate the knowledge produced in the aforementioned discussions, while considering the formal requirements of survey indicators and ensuring careful planning and piloting of the survey application.

One of the main difficulties in this process was that many of the items of the metric are completely new in the literature, having been developed for the novel approach presented in this book. For this reason, although the model and the dimensions of the model behind this survey are based on extensive theoretical research, the particular items of the survey were developed through an exploratory process that gave priority to capturing the particular aspects of collective life in Mexican municipalities.

In addition, according to the literature, the process of designing survey questions needs to include some reflection about the qualities that items must follow in order to be selected for the metric. A review of the literature quickly showed that there is a variety of qualities that indicators need to satisfy. In the literature, however, the use of different names to indicate similar qualities is common and, often, the qualities chosen in each study or project are dependent on the final purposes of the scale.4 Hence, we would be interested in developing items that satisfy the following qualities, which include many of the suggestions of the literature, without losing sight of the particular interest of this metric, i.e., to measure common good dynamics at the municipal level and to diagnose ‘development priorities at the local level’ through self-reported surveys. For this purpose, the four qualities are: specific, relevant, meaningful, and intelligible.

Specific: Items should be specific in the sense that they capture only the component that they intend to measure, and not any other element within the metric. To achieve this, items should clearly describe and adequately reflect the phenomenon targeted with the measurement. To maximise specificity and the respondents’ understanding, it is also important to be clear and unambiguous in the terms included in the item. This is essential to ensure that the data collected is consistent and comparable across municipalities and times. The complexity of the theoretical model behind this metric made achieving specificity particularly challenging. Since the purpose was that each item captured a particular aspect of the nexus of common good—and thus the linkages between dimensions and basic common goods (BCG)—it was sometimes difficult to highlight the aspect that predominated in a statement. To achieve this, the team focused specifically on simplifying the wordiness of the items and being clear about what the particular intersection of the model being measured was. Hence, the team tried (to the extent that this was possible) to avoid items that captured more than one aspect at a time, in order to reduce confusion in the respondent as to what the true purpose of the item was. Yet, this was not always possible and thus some items may not comply perfectly with this requirement. Nonetheless, this was a conscious decision by the team so as to ensure that the survey did not lose its complex systemic approach (which, in the end, is one of the main added values of the approach).

Relevant: To comply with this requirement, items should offer a valid measure of the desired underlying construct. There are a number of ways to assess this, for example the underlying construct might be decided statistically through factor analysis or based on the theoretical framework employed. In this project, relevance was assessed based on the degree to which the item was able to capture the dimensions proposed by the theoretical framework of the common good. Hence, if the item needed to capture, for example, the intersection between a dimension and one of the basic common goods (see section 3 below for further explanation about this), this intersection was first defined conceptually and then the item was construed based on that conceptual definition. Take the intersection between ‘Governance’ and the basic common good of ‘Rule of Law’ as an example. To develop the item, this intersection was first defined as the extent to which the law served everyone in the locality, and then the item was construed under this definition. Therefore, the final form of the item was ‘In this locality, the municipal administration is at the service of the majority’ (see Table 4 below).5

Meaningfulness and Intelligibility: This means that items must be intelligible and easily interpreted by the average respondent. There are a number of ways to achieve this, and one of them is cognitive interviewing. Cognitive interviewing is a technique that has expanded over the last forty years. It is routinely used by national institutes and research centres and has been recommended as a useful tool for developing quantitative indicators of multidimensional models of wellbeing (Camfield 2016). This tool uses qualitative interviews to test surveys, and it permits observation of the cognitive process that respondents use to answer the survey and evaluation of the quality and effectiveness of the items as well as questionnaire design (see Willis 1999; Forsyth and Lessler 1991).

In the construction of this metric, cognitive interviews were carried out with six individuals who were chosen based on their socioeconomic characteristics that resembled the average population in municipalities in Mexico (e.g., primary or secondary schooling, low- or middle-income households, etc.). The interview process sought to prompt the individual to reveal information about their comprehension of the statement, their response processes and the recall strategies they use to gather the information needed to answer a statement. The core research group discussed the findings from these interviews extensively in a series of meetings. These interviews allowed for the identification of those items that were difficult to comprehend or that entailed a complex cognitive evaluation from the respondent. They also helped us to improve response options and item wording, to get a sense of the length of the whole survey and to make a more thorough selection of the final list of items included in the scale.

Ultimately, the resulting version of the survey, including demographic questions, was finally tested in two pilot applications, one in the municipality of Ocotepec (June 2019) and one in the municipality of Atlixco (May 2019). In addition to testing the psychometric performance of the metric, these two pilot studies permitted us to test the entire fieldwork plan. This included, first, identifying the best mode of survey administration for these contexts (either paper-based or electronic surveys), and second, selecting the ideal training for the data collectors. The version of the survey that resulted from these pilot exercises was then used to collect data from stratified and representative samples in Atlixco and San Andres Cholula, results which are reported in the respective articles in a special issue of Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali (RISS 2020).

Based on the previous process, the final items of the survey were designed as statements to ascertain the level of agreement-disagreement of respondents on each issue. A five-point Likert scale was used for response options: (1) strongly disagree, (2) somewhat disagree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) somewhat agree, and (5) strongly agree. The limitations of agree-disagree response scales are well-known as they can be more prone to acquiescence response bias (Krosnick 2012). This bias reflects the common desire of people to be seen as affable and thus tend to agree with the statement regardless of its actual content (see also Nebel and Arbesu-Verduzco 2020 for other limitations). Despite these limitations, this response scale also has noteworthy advantages as it eases the administration of the survey by significantly reducing the duration and increasing comparability across dimensions and indicators to identify underlying constructs. Hence, in this metric this format allows us to reduce the time spent on data collection and other biases that arise as respondent tiredness increases.

The final survey is structured as follows. The first section contains fourteen demographic questions measuring well-known drivers of development and socioeconomic status including neighbourhood, sex, age, education, employment, and ethnicity; and five items that together form an indicator of socioeconomic status (number of bathrooms in the household, number of automobiles owned, access to Internet connection in the household, number of family-members employed, number of people sleeping in the kitchen). The second section of the survey covered the five dimensions of common good measured, through seventy-one items in total; sixteen items for Justice; eleven items for Stability; sixteen items for Governance; eleven items for Collective Agency Freedom; and seventeen items for Humanity. The final version of the survey, along with its content and justification, is presented below.

3. The Dimensions of a Common Good Metric and Its Indicators

The structure of the survey and its characteristics aim at reflecting the theoretical foundations of the metric explained above in two ways.

First, one of the purposes of the metric was to move beyond measuring the simple individual experience, in order to capture the collective processes that structure social life in a municipality. Hence, even though this metric lies at the level of individual perception, (most) items ask respondents to focus and reflect on social goods and the expected social practices of the people in their location. Arguably, these items capture collective (as opposed to individual) doings, in the sense that they refer to the collective action that constrains individual behaviour in the locality (see Chapter 1).6 The items try to measure the local practices that give structure and dynamism to shared life. This includes aspects such as the way people reproduce, modify, and/or give life to the way institutions work in practice. For instance, the indicator “People take the initiative when they have to solve problems in my locality”, in the dimension of Collective Agency Freedom, tries to measure the extent to which the population members value self-organising as a group in order to improve something in the locality. This indicator thus aims at capturing, through individual perception, a form of collective agency that goes beyond individuals, as it requires the common volition and shared action in the consecution of something valued collectively.

Second, the items aimed to assess the structure as well as the dynamics of the nexus of the common good in each of the dimensions (Justice, Stability, Governance, Collective Agency Freedom) aside from the dimension of ‘Humanity’ (which we briefly explain below). As mentioned above, the structure is measured by reference to the set of institutions that exist or the quality with which they are perceived to function in a municipality, such as laws, physical buildings, and existing legal support in relation to each of the dimensions. In turn, the dynamics of the nexus is gauged through dimensions and items assessing expected social practices in the common good of a municipality for each dimension (again, aside from the dimension of ‘Humanity’). Moreover, the degree to which both of these aspects of a common good dynamic are present is, in turn, evaluated in relation to some ‘basic social goods’, which are considered as a ‘minimal threshold […] inherent to any nexus of the common good’. This minimum set of basic social goods that form part of any nexus of the common good in a municipality are five: Rule of Law, Work, Education, Culture, and Solidarity (see Chapter 1).

Put differently, each dimension has at least one item that measures the combination of the structure of the dimension with one or more of the basic common goods. For instance, for the dimension of Justice, the structural aspects refer to people’s perception about equal opportunities in participating in the creation, valuation, and access to the benefits of the basic common good in question. In this sense, some items aim at capturing the relationship between the dimension (Justice) and the basic common good of ‘Solidarity’ in the structural aspect. One item, for example, tries to capture access to institutionalised forms of solidarity (“In my locality, there are places where people can go to get help (DIF, Red Cross, Church, etc.)”).

Similarly, each dimension has at least one item that measures the combination of the dynamic aspect of the dimension with at least one (or more) of the basic common goods. For instance, for the same dimension (Justice), the dynamic aspect refers to people’s perception in terms of the way people treat each other. To capture the relationship between the dimension (Justice) and the basic common good of ‘Solidarity’ in its dynamic aspect, one item tries to capture the reciprocity among its members (“In my community, if someone is having a hard time, we organise to help him/her”).

Moreover, to address the systemic emphasis of the nexus (even if partially), some items reflect the strength of the relationship between the dimensions and the way each dimension potentialises the other. For this, a number of individual items focus on capturing the two-way relationships between dimensions (e.g., Governance and Stability, Governance and Collective Agency, Governance and Justice, and vice versa). Take, for example, the two-way relationship between the dimensions of Governance and Stability. On the one hand, the governance of stability is measured by one item focused on the capacity of the municipal government to promote a dignified life for everyone in the locality in the long term (“The municipal government works to ensure that everyone can keep living in the community in the long term”). Reciprocally, on the other hand, another item tries to capture the stability of governance (“The programmes implemented by the municipal government have long-term benefits”). Hence, as mentioned before, this multidimensional metric is therefore composed of items that try to capture not only a dimension in isolation, but also the interconnection between dimensions and sub-domains (such as basic common goods).

Now, the Humanity dimension is treated differently (see Chapter 2). For this dimension, the metric drops the structure/dynamic division. This dimension is treated differently since it aims at capturing the extent to which the whole structure and dynamic of the nexus results in a socially virtuous way of living together in the community, which makes itself visible through a set of social virtues embodied in people’s collective practices in a community. These social virtues include items related to freedom and responsibility, justice and solidarity, peace and concord, and others. Hence, items in the survey ask about the expected behaviour in the community in relation to these.

On the basis of the theoretical framework, the next subsections present the list of indicators of a metric of a common good dynamic. Each subsection describes one of the dimensions. Each dimension, in turn, presents a table that includes information about: the list of items attributed to the dimension (column 1); and a justification/description of the purpose of each item (column 2).

I. Justice

The dimension of Justice (Table 1) captures the collective processes and institutions at play in a municipality through which people share common goods (in their valuation, production, and benefit). The dimension is measured in terms of equality of opportunity in the five basic common goods (i.e., structure), and in people’s expectations about the common practices (i.e., how people treat each other) in the context of the other dimensions of the matrix (Governance, Stability, and Collective Agency Freedom).

Table 1. Justice: items and justification.

Source: IPBC’s team elaboration.

II. Stability

The dimension of Stability (Table 2) captures the permanence and transmission of the nexus of the common good. The structure of the nexus is measured through items that focus on the extent to which this structure, manifest in the five basic common goods, allows the transmission of humanity in the nexus. The dynamics of the nexus, in turn, captures the permanence of the three key elements of the dynamics of common good: Governance, Justice and Collective Agency Freedom. This permanence is measured through (a) the quality of the duration of local institutions (to all, to us, to the majority, or to some); and (b) the time projection of institutions (e.g., one, five, or ten years).

Table 2. Stability: items and justification.

Source: IPBC’s team elaboration.

III. Governance

The dimension of Governance (Table 3) captures whether the basic common goods in a municipality are governed as common goods or not. Put differently, the focus is on whether the basic common goods are placed at the service of the community as a whole (for the good of all and everyone) and not co-opted by certain groups. The structure of the nexus is measured through items that assess the quality of the management, organisation and administration of the common goods by the local authorities and civil society. The dynamics of the nexus is captured through items that evaluate the capacity of political governance to serve the common good. Four areas of quality are studied: authority of the governance, efficiency of the governance, conflict resolution and generation of consensus.

Table 3. Governance: items and justification.

Source: IPBC’s team elaboration.

IV. Collective Agency Freedom

The dimension of Collective Agency Freedom (Table 4) answers the question: ‘what determines the quality of collective agency in a municipality?’ It measures, on the one hand, the dynamic aspect of collective agency, that is, the capacity of the local population to act together in view of their future. This capacity to self-organise can be captured through (a) the value given to the capacity to self-organise in the community; (b) the legal possibility to self-organise; (c) the capacity to generate consensus around a common goal; (d) the capacity to self-govern in the consecution of a common goal; and (e) the capacity to generate synergy with other organisations to reach a common goal.

On the other hand, it measures the organisation/structure of collective agency, which can be observed through the existence of organisations that give structure to community life and its quality. Hence, the items related to this aspect measure the capacity of the existing collective agency in the municipality to generate dynamics that promote the common good. This can be inferred through three criteria: (a) the freedom of agency in these organisations; (b) the possibility of universalising the shared benefits generated by these organisations; (c) the quality of the existing relations between organisations.

Table 4. Collective Agency Freedom: items and justification.

Source: IPBC’s team elaboration.

V. Humanity

The dimension of Humanity (Table 5) refers to the social behaviours and expectations that emerge in the population as a result of the common good dynamics. That is, what are the social expectations in the community about the behaviours that express humanity. These can be assessed through the expectations of standard behaviour in the community, including (a) freedom and responsibility; (b) justice and solidarity; (c) peace and concord; (d) prudence and magnanimity; (e) resilience and courage; (f) rationality and wisdom.

Table 5. Humanity: items and justification.

Source: IPBC’s team elaboration.

4. Discussion and Future Improvements

In this section, we would like to offer some general reflections/questions about the metric of the practical common good approach presented above. To begin with, we would like to point out that in a world in which the development of new indicators of social progress/development abounds, this metric has the potential to be much more than a simple alternative to other indicators on progress, wellbeing, or development. In fact, rather than being an alternative, it seems to us that it paves the way towards a new list of indicators interested in processes, actions, and complexity that can complement existing outcome-oriented measures. By shifting the focus of analysis to indicators aiming at capturing institutionalised practices of the local population (in structure and actions), the metric sheds light on the complex social settings within which individuals act, think and choose, and their relevance for understanding the outcomes that societies produce.

People’s positive and engaging reactions to the survey in initial pilot applications, as well as their applications to assess different social situations, attest to the significance of this information for people’s lives and their localities. Consequently, data produced by this metric will be crucial for informing decision-makers about local social processes, institutions, and their interaction that promote or hinder a common good dynamic. This information cannot but be fundamental for identifying key areas of opportunity and strengths present in the local community (e.g., quality of social ties, organisation skills, knowledge of existing social institutions, etc.) from which to build up a plan of action that promotes a community-driven development towards the common good of living well together.

Despite these welcomed points however, there are some questions, which, although we do not aim to respond to them here, need to be asked and reflected upon to clarify and improve the metric. First, some general questions may arise in relation to the theoretical model and its dimensions. Even if there is a theoretical framework underlying the metric, the criteria for selecting the dimensions are still insufficiently clear. For instance, while we do not dispute the selection of the five normative dimensions already included in the model, one may wonder why other dimensions (or other basic common goods) are not included. One could think that a comprehensive notion of the common good would include, or discuss more explicitly, social concerns such as peace, security, the environment, and the economy, among others. Of course, we grant that the model may indirectly touch upon these concerns and that any metric needs to be as simple and parsimonious as possible, yet an explicit reference to the reasons behind the components of the metric would be welcome.

The second concern is related to the simplicity of the items of the survey. It is desirable that a questionnaire be sure that its items are easy to interpret and clearly understood by the respondent. Although the presented survey already went through a long process of refinement, the survey remains complex in at least five areas. One is the inherent complexity of the statements themselves. The survey asks respondents to think beyond their individual experience in order to reflect on their social world and its common practices (e.g., “In my locality, it is valued that people organise themselves to solve their problems”). While common practices may be identifiable to people after reflection, the dynamics of expected patterns of social behaviour and their influence in the social world tends to be unconscious and difficult to pin down explicitly. A subsequent issue that adds to the inherent complexity of the items is the composition of the statements. Several statements in the metric refer to multiple phenomena at the same time. For instance, the statement “The municipal government is able to reach agreements that benefit the entire community” may direct attention towards both the ability of the government to generate consensus or to the resulting benefits of the agreement, or to the combination of the two ideas (which is the intention of the question).

This leads to difficulties in interpreting responses. This can be problematic, on the one hand, for composite statements like the latter (is the data shedding light on the ability of the government to generate agreements? Or is it about the benefits in society? Or is it about the ability to generate consensus that at the same time results in a benefit for the entire community?). On the other hand, because even if it is not a composite statement, we do not really know what is behind participants’ responses. This is more salient if we want to compare responses between groups. For instance, if we find that women’s answers to the statement “Most people in my locality have work” were lower than that of men, we do not know what these lower responses indicate. Are women responding based on their individual experience (i.e., women have less access to work)? Or are they responding based on what women perceive around their community (this is the original intention of the item)? If the latter, do they perceive that there is less work available for women in particular, or in general for the population as a whole (and why might this be different from the men’s perception?) In other words, the challenge is that we can only know women perceive this feature differently, but we cannot be sure about what, from their perspective, the exact problem is regarding access to employment in the municipality.7

Second, a related, but somehow distinct concern in relation to the items of the metric is the fact that statements aim at measuring people’s perceptions about social phenomena in their localities that contain normative inclinations. In other words, the items are associated with desired common behaviours and processes within the locality, and how individuals perceive these. Although researchers have been testing self-reported items since the 1960s (see Zapf 2000), they have been contested for their potential to be influenced by social desirability biases and adaptive preferences (e.g., Kahneman and Tverskey 1984; Frederic and Loweeinstein 1999; Gasper 2007). Social desirability bias occurs when people answer survey questions based on what they think is expected from them by the researcher or what they themselves think is the ideal behaviour in their locality, instead of what actually occurs in the locality. In turn, adaptive preferences reflect the possibility of people adapting to positive or negative life circumstances. Hence, social desirability and adaptive preferences could result in data that portray the locality more positively than it is actually experienced. This can be especially problematic if the items originally contain normative values of what the desired practice of common good in the locality for a specific dimension is.8

Third, when metrics are used as a ‘diagnostic tool’ to inform social actors about social priorities in the locality, one may also worry about the malleability and the temporality of the phenomena being measured. What we are questioning here is the possibility of changing common social practices, which are established patterns of behaviour embedded in the culture of a certain population, through social policies; and, we could also ask about the timeframe that this change may take. These questions are relevant because they raise the query about the correct time for applying a follow-up survey to measure possible changes in the common dynamic of a municipality, for example. Similarly, when designing metrics to be of use for policy actors, we also need to think about indicators that can shed light on potential courses of action for policy-making and thus on indicators that capture social problems that can be modified by policy interventions.

Fourth, this type of comprehensive metrics also makes explicit the tradeoffs associated with the choice of statistical tools available to construct the model, such as Factor Analysis, Principal Component Analysis or Structural Equation Modelling. Statistics such as the latter rely on the amount of variance shared by the items in order to find commonalities between them. Hence, the fact that some of the items of this metric capture different dimensions simultaneously, due to the interconnections of the model, makes it more difficult for these statistical tools to discriminate between dimensions, thereby lowering the quality of the metric based on the reliability analysis offered by these tools. In other words, it is difficult to reconcile the complexity of the metric with the assumptions and requirements behind the statistical tests.9 However, sometimes these tradeoffs need to be carefully considered and evaluated by researchers when they are interested in constructing more comprehensive, interdependent, and multidimensional measures that capture the complexity of human existence.

A fifth, and last, reflection relates to the difficulty of applying this kind of metric to very diverse audiences. The items of the metric presented here are complex and require a fair amount of cognitive reflection to be answered. Some of them might also require some degree of knowledge and experience about how the local government works, how neighbours interact and act together, and the values of the locality as a whole. Additionally, some items require basic knowledge of the abstract lexicon such as ‘laws’, ‘social programmes’, and ‘property title’. This could increase the difficulty of applying this survey to individuals who have not participated in different public spheres in their localities, nor kept a household, or those who do not have a certain level of education. This is particularly relevant if the metric will be applied in diverse populations, including those municipalities with indigenous and non-indigenous backgrounds. Translation issues are also relevant here, since the interpretation of the meaning of survey items might vary for people whose mother tongue is not Spanish.10 Hence, issues of meaning, interpretation and translation need to be taken into account when comparing results across municipalities.

To close the section, we would like to point out that while these concerns may not be trivial and perhaps more reflection about them is required, we also recognise that the extent to which these previous points are relevant to the metric is a matter of further empirical investigation.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have presented the rationale, the process, and the structure of the metric developed by the IPBC of Puebla, México to measure the common good dynamics of a municipality. The elaboration of the indicators was the result of a research project that received feedback from prestigious experts, local specialists, NGOs, public officials, and researchers. It was carefully designed to reflect the theoretical framework behind and the common requirements of survey indicators, but also to obtain and include the feedback of potential respondents of the survey through cognitive interviewing. Much reflection has gone into the construction of this metric. We have recognised the many trade-offs involved in the process, and made decisions to the best of our abilities. With this chapter, we wish to make these decisions and their potential implications for the final form of the survey and the resulting data explicit.

We also argued that the new information that this measure of common good will offer to municipal governments, NGOs, researchers, and decision-makers can facilitate the adoption of better-informed policies that take into account the dynamics and structure of the common good produced by the citizens of a municipality. In fact, the initial process of constructing the indicator has already had concrete effects, since it has already encouraged the collaboration of municipal governments in recollecting the data and compromising in order to take the results into account in their municipal development plans.

Overall, we can say that the theoretical framework and the metric presented in this book already provide valuable contributions for the purpose of bettering the measurement of development processes at the local level and the information that governments use to make better policy decisions. However, this is for researchers, governments, policy actors, and, more importantly, for people themselves to decide. Hence, the main intention of this chapter is to promote and encourage more and better discussion in this direction.

References

Alkire, S. 2015. The capability approach and well-being measurement for public policy, OPHI Working Paper, No. 94. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199325818.013.18

Brown D. 2009. Good practice guidelines for indicator development and reporting. A paper at the Third World Forum on Statistics, Knowledge and Policy, Charting Progress, Building Visions, Improving Life, 27–30 October, 2009, Busan, Korea.

Camfield, L. 2016. “Enquiries into Wellbeing: How Could Qualitative Data Be Used to Improve the Reliability of Survey Data?”, in White, S. C. and Blackmore, C. (eds), Cultures of Wellbeing, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137536457_2

Deneulin, S. and Shahani, L. 2009. An Introduction to the Human Development and Capability Approach Freedom and Agency, London; Sterling; Ottawa: Earthscan. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849770026

Forsyth, B. H. and Lessler, J. T. 1991. “Cognitive laboratory methods: a taxonomy”, in Biemer, P. et al. (eds), Measurement Errors in Surveys, New York: Wiley, 393–418.

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G. 1999. “Hedonic adaptation”, in Kahneman, D. (ed.), Well-Being: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, New York, Russell Sage Foundation.

Gasper, D. 2007. Uncounted or illusory blessings? Competing responses to the Easterlin, Easterbrook and Schwartz paradoxes of well-being, Journal of International Development 19/4, 473–492, https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1383.

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. 1984. Choices, values and frames, American Psycological Association, Inc. 39/4, 341–350.

Kelley, K., Clark, B., Brown, V., and Sitzia, J. 2003. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research, International Journal of Quality in Health Care 15/3, 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzg031

Krosnick J. and Fabrigar, L. 2012. “Designing rating scales for effective measurement in surveys”, in Lars Lynberg et al. (eds), Survey Measurement and Process Quality, Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics, New York, Wiley, 141–164 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118490013.ch6.

Nebel, M. and Arbesu-Verduzco, I. 2020. “A metric of common goods dynamics”, in Beretta, S. and Nebel, M. (eds), A Special Issue on Common Good, Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali, 4, 383–406.

Ramírez, V. 2021. Relational Well-being in Policy Implementation in Mexico: The Oportunidades-Propsera Conditional Cash Transfer, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74705-3

Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali. 2020. A Special Issue on Common Good, Beretta, S. and Nebel, M. (eds). https://riss.vitaepensiero.it/scheda-fascicolo_contenitore_digital/simona-beretta-mathias-nebel/rivista-internazionale-di-scienze-sociali-2020-4-a-special-issue-on-common-good-000518_2020_0004-370666.html

Stiglitz J. E., Sen A., and Fitoussi, J.-P. 2009. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Perfornance and Social Progress. Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE), Paris. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi-Commission-report.pdf

Székely, M. 2006. Números que mueven al mundo. La medición de la pobreza en México, México: Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

Willis, G. B. 1999. Cognitive Interviewing: A ‘How To’ Guide. Reducing Survey Error through Research on the Cognitive and Decision Processes in Surveys, short course presented at the 1999 Meeting of the American Statistical Association. https://www.hkr.se/contentassets/9ed7b1b3997e4bf4baa8d4eceed5cd87/gordonwillis.pdf

Zapf, W. 2000. Social reporting in the 1970s and in the 1990s, Social Indicators Research, 51, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006997731263

Appendix

Instrument’s questions to measure the common good dynamics in original language (Spanish).

|

Ítem |

|

|

J1 |

En mi localidad, los derechos de cada persona son respetados. |

|

J2 |

En mi localidad, la policía sirve para protegerme. |

|

J3 |

En mi localidad, se pueden corromper los funcionarios públicos. |

|

J4 |

En mi localidad, se valora trabajar. |

|

J5 |

En mi localidad, la mayoría tiene trabajo. |

|

J6 |

En mi comunidad es importante que todos tengan la posibilidad de estudiar. |

|

J7 |

En mi localidad, cualquier persona puede estudiar si así lo decide. |

|

J8 |

Las tradiciones culturales de mi localidad son respetadas por la mayoría. |

|

J9 |

En mi localidad, los refranes los entienden la mayoría. |

|

J10 |

En mi comunidad, si alguien la pasa mal nos organizamos para ayudarle. |

|

J11 |

En mi localidad, hay lugares donde la gente puede acudir para recibir ayuda (DIF, Cruz Roja, Iglesias, etc.). |

|

J12 |

En mi localidad la gente no necesita dejar el municipio para poder vivir. |

|

J13 |

Los programas de los gobiernos municipales benefician a la mayoría de la población. |

|

J14 |

En mi localidad hay grupos sociales que no tienen acceso al poder. |

|

J15 |

En mi localidad hay algunos grupos sociales que tienen todo el poder. |

|

J16 |

En mis actividades diarias en la localidad, soy frecuentemente humillado. |

|

S17 |

En mi localidad cuando se atrapa a un ladrón lo entregamos a la policía. |

|

S18 |

En mi localidad cuando alguien es arrestado, la policía lo trata con respeto. |

|

S19 |

Me enorgullece hablar de mi trabajo con otros. |

|

S20 |

Es importante haber ido a la escuela para participar en la vida social de la localidad. |

|

S21 |

Me siento orgulloso de la cultura de mi comunidad. |

|

S22 |

Las generaciones más jóvenes participan en las fiestas, costumbres y tradiciones de mi localidad. |

|

S23 |

Cuando yo o algún familiar buscamos ayuda de una institución en la localidad, somos tratados con respeto. |

|

S24 |

Los programas del gobierno municipal tienen beneficios de largo plazo. |

|

S25 |

Si compro un terreno o una casa, tengo confianza que el gobierno respetará mi título de propiedad a futuro. |

|

S26 |

La mayoría de las asociaciones de mi localidad existen desde mucho tiempo (Por ejemplo: mayordomía, jornales, sociedad de padres de familia, grupos ejidales, etc.). |

|

S27 |

Los miembros de las asociaciones suelen reunirse con frecuencia. (Por ejemplo: mayordomía, jornales, sociedad de padres de familia, grupos ejidales, etc.). |

|

G28 |

Considero que en esta localidad la administración municipal está al servicio de la mayoría. |

|

G29 |

En la localidad, la mayoría paga impuestos. |

|

G30 |

El gobierno se esfuerza para que los trabajadores tengan mejores condiciones laborales. |

|

G31 |

El gobierno de mi localidad promueve de manera activa el mantenimiento y la creación de espacios públicos como parques, plazas y calles. |

|

G32 |

En mi localidad la mayoría cuida los espacios públicos como parques, plazas y calles. |

|

G33 |

El gobierno crea las condiciones necesarias para que exista una solidaridad efectiva entre los ciudadanos de mi localidad. |

|

G34 |

En mi localidad el gobierno hace el esfuerzo para que todos terminen la preparatoria o bachillerato. |

|

G35 |

En esta localidad se respeta la autoridad del gobierno municipal. |

|

G36 |

El gobierno municipal trabaja para el bien de la mayoría. |

|

G38 |

El gobierno tiene la voluntad de resolver conflictos entre diferentes grupos de la localidad. |

|

G39 |

El gobierno municipal es capaz de generar acuerdos que benefician a toda la comunidad. |

|

G40 |

El gobierno municipal busca que todos tengan las mismas oportunidades en la comunidad. |

|

G41 |

El gobierno crea las condiciones necesarias para que nadie tenga que dejar la localidad para vivir. |

|

G42 |

El gobierno de mi municipio nos escucha. |

|

G43 |

Puedo participar en las decisiones de mi municipio. |

|

A44 |

En mi localidad, se valora que la gente se organice para resolver sus problemas. |

|

A45 |

La gente toma iniciativas cuando se tienen que resolver problemas de mi localidad. |

|

A46 |

Los vecinos logramos ponernos de acuerdo cuando tenemos un problema común. |

|

A47 |

Los vecinos sabemos organizarnos para solucionar un problema común. |

|

A48 |

Las leyes nos impiden frecuentemente dar solución a problemas locales. |

|

A49 |

La mayoría de las veces, los vecinos logramos los objetivos que nos proponemos. |

|

A50 |

Cuando nos enfrentamos a problemas difíciles, en mi comunidad podemos conseguir el apoyo de otras instituciones. |

|

A51 |

Puedo expresar mis opiniones en los grupos en los que participo. |

|

A52 |

La mayoría de los grupos de mi comunidad contribuyen al bien común. |

|

A53 |

Es posible la cooperación entre los grupos de mi localidad. |

|

A54 |

Los grupos de mi localidad cooperan con el gobierno. |

|

H55 |

La gente de mi localidad exige que me haga responsable de mis acciones. |

|

H56 |

La gente de mi localidad se molesta si no cumplo con mis promesas. |

|

H57 |

La gente de mi localidad se molesta si no trato a los demás de manera cordial y respetuosa. |

|

H58 |

La gente de mi localidad se molesta si no hago lo correcto. |

|

H59 |

En mi localidad, se ve mal a la gente que no es solidaria con los demás. |

|

H60 |

En mi localidad, la gente es honesta. |

|

H61 |

En mi localidad, cualquier persona puede salir de día sin temor. |

|

H62 |

La gente de mi localidad acostumbra a resolver conflictos de manera pacífica. |

|

H63 |

La gente de mi localidad se enoja si no pienso antes de actuar. |

|

H64 |

La gente de mi localidad no tolera que una persona sea mala onda con los demás. |

|

H65 |

La gente de mi localidad espera lo mejor de mí. |

|

H66 |

La gente de mi localidad espera que yo sea fuerte cuando sufro alguna desgracia. |

|

H67 |

La gente de mi localidad esperan de los demás que hagan prueba de valor en la vida. |

|

H68 |

La mayoría de las personas de mi localidad, expresa sus opiniones de manera clara. |

|

H69 |

Cuando se habla de temas importantes, la gente de mi localidad pide que se haga de manera seria y objetiva. |

|

H70 |

La gente de mi localidad espera que yo no cometa dos veces el mismo error. |

|

H71 |

La gente de mi localidad sabe reconciliarse después de un conflicto. |

1 Chapter 3 of this book presents a slightly modified version of the article with the same title available in Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali, Research In Social Science (2020), vol. 4, published by Vita e Pensiero, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy. We are grateful to the editors of the journal for granting the rights.

2 The following paragraphs are inspired by the ideas of two well-known economists: ‘We need to stop making important what we measure, instead we need to measure what is important’ (Branko Milanovic). Measuring what matters may involve rejecting being ‘precisely wrong in favour of being vaguely right’ (Hawthorn on Amartya Sen’s work: 1987, viii).

3 We provide a brief description of each of these dimensions below, along with the items proposed to measure each dimension.

4 A commonly cited approach is SMART, a methodology used by a number of development agencies (e.g., the World Bank and the UN) and governments to construct indicators that measure social outcomes and programme results. SMART stands for indicators that are Specific, Measurable, Attributable, Realistic and Time-bound (for a broader list of qualities see e.g., Brown, 2009).

5 Tables 1 to 4 present the items and the conceptual definition or justification of the indicator for each dimension.

6 Some items are indeed directed towards the respondent’s individual experience as opposed to one’s perception about common social practices (e.g., “In my locality, the police protect me”). However, we think that in these few cases, the aggregation of responses provides a good proxy about the collective perception of, for example, the effectiveness of the police in the community.

7 Note that these concerns may also complicate the statistical analysis of the results.

8 For instance, in the application of the survey in two different municipalities (Atlixco and San Andrés Cholula), participants tended to respond more positively to statements related to people’s behaviour than to those related to the municipal government’s actions (see papers in RISS special issue 2020).

9 See e.g., Ramírez (2021) for a similar experience with a multidimensional model of psychosocial wellbeing and a discussion on this.

10 See the Appendix for the Spanish version of the survey.