7. Organising Common Good Dynamics: Justice

© 2022 Rodolfo De la Torre, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0290.09

Introduction

The common good refers to those social conditions that members of a community provide to everyone in order to fulfil a relational obligation they all have to care for certain interests that they share. In very general terms, justice is what we owe to each other, and underlies the will to render to each his or her due. So, justice is part of a relational obligation necessary to promote common interests and requires the provision of particular social conditions to be fulfilled.

The ‘nexus of the common good’ is a collection of interrelationships between various specific common goods in a given society. As a nexus, the Common Good, capitalised to distinguish it from specific common goods, is a set of social relationships to fulfil voluntarily shared commitments. Justice is one of these communal links for the accomplishment of reciprocal duties.

The relationship between justice and the Common Good is a key element for a meaningful measurement of the Common Good itself. In this link, there is a difference between a shared meaning of justice, which is abstract and general, and the implied share of the common benefits created by a common good, with concrete rules to operationalise the concept of justice. The former is the practical reason to accomplish an equitable distribution of the latter. Both could be examined in terms of moral values, either consequential (i.e., having utility) or not.

The social meaning of what is just, intangible as it is, has to be translated into a concrete and measurable way to decide individual conflicts about what is exclusive and competitive. Several questions arise: what is understood by justice at the level of concepts and procedures? What role should be given to an appraisal of their outcomes? Considered as ways and/or consequences, justice is one of the normative dimensions of any model of the Common Good. It is one of the social functions that regulate the nexus’s organisation.

The goal of this chapter is to explore possible metrics for the justice component of the nexus of the common good concept, building on Nebel and Medina (Chapter 2). The proposed metric should be focused on the nexus’s procedural or distributional relationships, and it should be simple and unambiguous. As a nexus, the Common Good should be conceived as social cohesion stemming from shared meaning in a specific society and providing unity, identity, stability, and resilience to the community.

Justice should include a shared perception of goals, a shared procedure for achieving them, and a shared way to distribute benefits or results. Justice implements acceptable interactions (procedural justice) and what is fair (distributional justice) in the nexus. Justice watches to make sure the nexus does not disintegrate, and it seeks to promote a dignified and flourishing life for each and every person in the nexus, which in turn promotes justice.

The present document is divided into four sections. The first revises the concepts of the common good and the nexus of the common good, and the normative dimensions proposed to measure the quality of the nexus. This section discusses the link between the common good and two economic concepts related to both the idea and mechanisms of justice: social welfare and public goods. The second section analyses the meaning of the concept of justice as a normative dimension of the common good. Finally, the last two sections explore alternative ways to measure ‘justice’, including justice as equality of opportunity.

The chapter proposes the following:

- Justice cannot be reduced to a separate dimension on its own, isolated from the agency (see Chapter 4), humanity (see Chapter 5), governance (see Chapter 6), and stability (see Chapter 8) components of the Common Good. However, it makes sense to distinguish this dimension for analytical and measurement purposes. This means that the measurement exercises are unavoidably quite static and limited in scope.

- It is convenient to conceptualise the justice component of the Common Good as dealing with the fair generation of social goods and the possibility of shared benefits according to individuals’ contributions to the production process of the Common Good, but in a context of social solidarity. For this to happen, individual agency must be protected, which implies that the procedural aspect of justice be measured.

- One way to translate the concept of distributive justice to a measurable index that goes beyond equality of results is through the idea of equality of opportunity. Solidarity requires that circumstances beyond the control of individuals—circumstances that put them at a disadvantage with respect to others—be compensated for, so results are determined only by effort, which is under each person’s control. The inequality of results explained by circumstances is an indirect measure of ‘unfairness’ or distributive injustice.

The chapter concludes by describing actual measurements of inequality of opportunity for several countries, including how the concept relates to the idea of social mobility. The chapter presents measures of inequality of opportunity at the state level in México, and suggests ways to obtain such indices at the municipal level. Finally, several limitations and warnings about the inequality of opportunity approach are presented.

1. The Common Good

Embodied in institutions, goods, and practices, a common good is a set of shared values and interests within a group of autonomous individuals who relate in a certain way with respect to each other (e.g., as members of a family, as part of an organisation, or as citizens in a society). A common good is a set of conditions that enable the members of a group to attain for themselves reasonable objectives, for the sake of which they have reason to collaborate with each other in a community (Finnis 2011). A common good approach focuses on groups or communities while concentrating on the process through which they achieve and maintain social goods (see Introduction, Chapter 1 and Chapter 2).

The common good is a concept that can be used to assess the moral goodness of social states in which the explicit position and the relationships of each participant with respect to others is important. It does not entail that individuals have the same values; it implies only that there be some set of conditions that needs to be present if each person is to attain their own objectives. Unlike the economic notions of ‘efficiency’ or ‘social welfare,’ or even transcendental institutionalism’s views of justice (Sen 2009), the common good goes beyond the anonymity of individuals or just the consideration of end results.

The common good is a notion of what is good within the boundaries of a social relationship. It consists of the conditions and interests that members have a special obligation to care about due to the specific relationship they have with other members of a group. In a neighbourhood, for instance, public goods, like street lamps that work, or clean sidewalks, are part of the common good because the bond of sharing the same public spaces requires members to take care of them in order to ensure safety and sanitary conditions for all.

I. Social Welfare and the Common Good

Economic values that are intended to be universal, such as efficiency or maximum social welfare, transcend the relationships in a specific community. Unlike the common good, these concepts set out fully independent standards for the goodness of social states with no fundamental reference to the requirements of a social relationship. According to economic efficiency defined by the Pareto criterion, for example, opportunities to improve some members of a society should be judged impartially without worrying about who benefits, as long as at least one individual improves without making others worse. But in a relationship that defines how individuals should act towards one another—e.g., neighbours should prefer to improve their neighbourhood if this does not harm others—the neutrality of efficient allocations does not satisfy the requirements of the relationship.

Social welfare notions that incorporate efficiency and distributive elements—e.g., inequality aversion—closely relate to the idea of distributive justice and could be useful within the boundaries of a relationship. For example, giving priority to the worst-off member of the neighbourhood, implied by a maximin Social Welfare Function, is closely related to the Rawlsian idea of transcendental justice, and makes sense when solidarity has been established in a community. But even equality-sensitive notions of the good retain other features that make it difficult to see how these notions could be internal to a relationship (Sen 1993a). One example is agent neutrality, which implies that the correct course of action does not change with the relationships that the agent happens to have (Williams 1973). Understood in this way, the common good requires an agent to perform an action in a non-neutral way, from the standpoint of her relationship with her group, instead of doing what is optimal for the world’s welfare in the abstract.

Because it is a non-neutral notion, the common good requires, for example, neighbours to prioritise their own circumstances such that doing so would bring about the best result for the welfare of the group. A neighbour might be required to act this way, even when increasing the welfare of her neighbourhood would lead to a suboptimal level of welfare in the world as a whole. These implications clearly take into account the ordinary understanding of the agent-relative character of relational requirements.

Social welfare criteria used to evaluate situations present in a society (social states) are not based on conceptions of the common good. Even the economic value of social relationships, based on concepts like social capital, is concerned with non-positional concepts of what is socially preferred: notions of the good or value that are independent of any particular social relationship. Nonetheless, an economic account of individual preferences for behaviour with a social benefit may incorporate a conception of the common good as part of agents’ motivation to contribute to aggregate welfare.

II. Public Goods and the Common Good

As a concept, social welfare is related to the idea of common good, since welfare is affected by changes in social behaviour guided by common good criteria and vice versa. Although they are not the same, the understanding of one concept enriches the other. Another important relationship to draw is between the common good and a public good. In economic theory, a public good is a particular type of good that all members of a community can enjoy (non-exclusion) without the consumption of one individual interfering with the consumption of any other (non-rivalry) (see Chapter 6).

A public good is hard to achieve by market mechanisms, where each agent is motivated only by their own self-interest. For example, imagine that the residents in a town could enjoy clean common areas if every resident followed the simple rule of not littering and paying their taxes, which in turn pay for cleaning. Cleanliness costs time and money, but every resident would be better off taking the time to put the trash where it belongs and paying their taxes in order to enjoy life in sanitary conditions. If most residents follow the rules, everyone in the town will enjoy the benefit, even those residents who do not comply. But there is no feasible way to exclude those who do not respect the rules from enjoying the benefit.

The optimal provision of a public good requires a non-egoistic course of action from each individual (see Roemer 2020). Take any resident in the town described. From the standpoint of their own self-interest, they should not follow the rules, but let others adhere to them. However, if they overcome their own self-interest, by a strong common conviction or internalising other people’s welfare, for example, they will produce the good of clean surroundings for all. In this way, shared values that define a common good due a particular social relationship can be confused with a public good or a set of public goods. But it is important to keep the two ideas distinct.

The facilities make up the common good look like public goods because they are open to everyone (e.g., the administration of justice). This means that it is not possible to exclude those who do not contribute from enjoying the benefits, and as long as the facilities are not congested to the point of not allowing more cases, the administration of justice for one does not preclude the same treatment for the rest. The facilities that make up the common good serve a special class of interests that all citizens have in common, i.e., the civic relationship of justice, but each citizen will have private interests that could be in conflict with these common interests. From the standpoint of a citizen’s egoistic rationality, such a facility may not be a net benefit to all and thus not a public good.

Despite the differences, some public goods are closely related to some common goods: specifically, collectively produced public goods that involve social capital (see Table 1). That kind of good (X) requires the participation (effort time T) of at least a certain number of individuals (i = 1,2,3…n) in a community; a single agent cannot produce them. X is a public good since it provides satisfaction when consumed at the same time by several individuals (Xi is the simultaneous consumption of individual i). The perceived consumption depends on the empathy level toward other individuals (ai, represents how much X benefits i, taking into account other people’s welfare; more empathy increases ai,), and all individuals’ perceptions make the good public (the sum of all ai is one in the case of private goods and more than one of a public one). Social capital here is conceived as empathy; for each individual the welfare of others is part of their own welfare (Robison and Ritchie 2019). This is very similar to a common good defined by shared empathy values that demands collective action for its production.

Table 1 Collectively produced public goods that involve social capital.

|

Concept |

Formally |

Implications |

|

The public good is produced collectively |

X=X(T1x,T2x, T3x,…,Tnx) |

Production of the public good takes time Tix |

|

Xi=ai X (ai is an empathy coefficient) |

||

|

Individuals purchase and consume private goods |

Yi=w Tiy (w is the real wage) |

There is a market for labour and private goods |

|

Individuals value the public and the private goods |

Vi = Vi ( Xi, Yi ; Ti) Ti= Tix + Tiy |

Individuals maximise Vi subject to a time constraint |

|

W=W (V1, V2, V3,…,Vn) |

Social welfare depends on the public good |

Individuals can purchase a private good (Yi) with labour income (w Tiy), but not the public good, which they have to generate with others. So they allocate time for private consumption and time to produce the public good (Tix), maximising the value of the joint consumption, subject to a time constraint (Ti). The production of the public good demands coordination, which is not provided by market forces as in a private good, but both goods contribute to social welfare (W) throughout the individual value obtained by each individual (Vi).

In this schematic model some public goods and common goods are excluded. For example, a single agent contracting labour and inputs in the private market can provide a park or a library, which produce fresh air and a repository of knowledge, even in a sub-optimal way. But other public goods, like the rule of law in a state or public policies against discrimination, cannot be offered by a single agent but require the involvement of at least a certain majority of individuals. In this case the public good is closer to the nexus of the Common Good, and it is to that relationship that the collectively produced public goods involving social capital are relevant.

III. The Nexus of the Common Good

What human beings living in society hold in common are relationships and interactions. Community is, among other things, a unifying link between persons. As conscious and intelligent beings, individuals share connections in the physical and biological world, in the context of a culture and with similar objectives. Common interests are required to assemble conditions that are beneficial to achieving similar objectives, and those conditions can be said to be a good common for a group of people, a common good. A set of common goods requires a set of relationships, a network of them; this persistent network of common goods is its nexus. It enables human beings to reach their potential to do and be what they have reason to value. A stable, sustainable and resilient nexus is valuable beyond the production of specific goods. It has an intrinsic value, conferring a sense of belonging and identity on its members, for example, and an instrumental value (see Chapter 2).

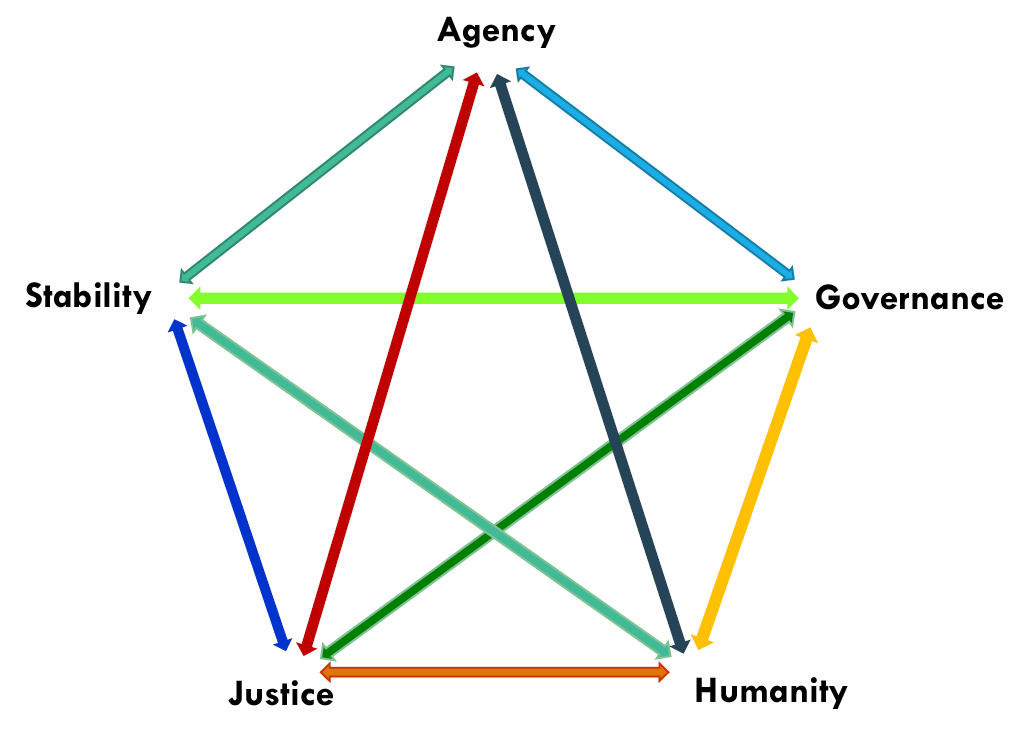

In summary, as introduced in Chapter 2, there are five key characteristics of the nexus of the common good:

- It considers agents’ shared concerns that arise from explicit relationships;

- It promotes and helps to fulfil the potential of human lives;

- Its stability has intrinsic and instrumental value;

- The quality of its governance enables effective collective action;

- It has a component of procedural and distributional justice.

These five dimensions of the nexus—agency, humanity, stability, governance, and justice—should be conceptualised and measured (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The common good pentagram. Source: Nebel and Medina (Chapter 2)

Clearly, a complete measurement should take into account the twenty links between various dimensions of the nexus.

2. Justice and the Common Good

The Common Good, as a set of conditions that allow the members of a community to collaborate to achieve or carry out objectives or values for themselves, implies justice as the practical will to favour and promote the common goods of the communities themselves. Thus, the nexus of the common good needs practical guidance in order to reach collective decisions that a purely private society would not be able to make. Collective decision-making must unfold in public life to transcend the limitations of individual concerns (e.g., market failures) and promote shared benefits (e.g., public goods), and governance must facilitate such decision-making if it is to be successful. Governance must include at least some restraints against interference in any individual life-plan and any form of association, that is, some form of ‘negative rights.’ Upholding such rights is a form of ‘justice,’ albeit an incomplete one (Berlin 1969).

The nexus of the common good has a component of social justice (e.g., respect for basic rights, freedoms, and distributional principles) but goes beyond that because it must maintain patterns of conduct that serve common interests. Members of a community share concerns that limit competing private claims about total resources through a distributive principle that determines how the group should respond to such particular interests.

Justice encompasses several elements (Finnis 2011): one’s relations and dealings with other individuals; what is owed to another and, consequently, what that other person is entitled to, and; a type of equality, in the sense of balancing different characteristics, processes or results in the same way for all individuals, which could be called equity.

The realisation of the common good faces two problems. First, the distribution of resources, opportunities, results and responsibilities; in general, everything that serves the common good until it is appropriated by particular individuals (distributive justice). Second, the admissible dealings between individuals and/or groups, where what can be distributed is not directly in question (commutative justice).

Distributive justice implies a reasonable solution to the problem of assigning something that contributes to the Common Good but which must be appropriated by individuals. Commutative justice deals with criteria for determining what relationships, in the sense of interactions, are appropriate between individuals, including groups. This distinction between distributive and commutative justice will be useful to distinguish approaches on the way of considering the community to which one belongs, the obligations towards it, and a certain sense of equity.

In the following sections, a general conception of justice and specific ways of understanding different aspects of the concept will be developed, for which it is convenient to remember the distinction between distributive and commutative justice.

3. Justice

Justice refers to how persons are treated when they have conflicting claims in entering into specific relationships; justice always concerns interpersonal relationships, and something is a matter of justice only where there is a plurality of individuals dealing with one another. As free agents in a particular community, individuals have shared concerns that define a common good, and justice is part of that. Justice requires an agent or group of agents willing to alter the circumstances surrounding the conflicting claims.

Conflicting claims can involve freedoms, opportunities, resources, or any other entitlement that has value for the individual or her community. Justice implies rights, that which can be claimed from others, and duties, that which is owed to someone else. This means that there are some limits that have to be respected in social interactions (do not harm others) and there are some claims that involve changing boundaries in social interactions (expand opportunities). Justice thus has consequences for both the potential and the fulfilment of human lives.

Justice is related to equality in a broad sense. To treat two individuals ‘equally’ under equal circumstances is a form of justice, but to treat them equally when they are not equal is not. This begs the Aristotelian question: equality of what? Whatever the answer, a crucial aspect of justice is a sort of proportionality. This is the basis for distributive justice of resources or entitlements in a community. In turn, the level and distribution of entitlements influences the possibility of dispensing justice in some other sense.

As for the ‘equality of what?’ question, Sen (1980) has forcefully defended the idea that capabilities, the set of possible beings and doings open to individual choice, should be of capital importance for an appraisal of well-being, but also for a theory of justice (Sen 2009). Any substantive theory of justice has to choose which informational space is pertinent to assess what is just or unjust. The concept of capability is of particular value because it is linked closely with the opportunity aspect of freedom, although the process of choice itself is important. Allowing, for example, a person not to be obliged to accept some state because of constraints imposed by others (see Chapter 4).

Capabilities define effective freedom, the opportunity to pursue people’s objectives—those things that a person values. They focus on human life, on the actual possibilities of living, not on the means to do so or the subjective valuation of what is accomplished. This informational basis is consistent with diverse individual theories of the good. Sen (1993b) explicitly asserts that ‘quite different specific theories of value may be consistent with the capability approach’ and that ‘the capability approach is consistent and combinable with several different substantive theories.’ So, the idea of justice for the common good, and the concept of the common good itself, would benefit from the adoption of the capability approach to effectively enhance individuals’ living conditions.

A way to further explore effective freedoms is the theory of justice as equality of opportunity (Roemer 1996). In this theory there is a boundary between what people are responsible for and what they are not. It recognises a particular conception of responsibility, denoting a situation in which a person has the control. Separating responsibility situations from circumstances that are out of individuals’ control means that egalitarianism has the specific purpose of leveling opportunity. Equality of opportunity for welfare is equalised if transferable resources have been redistributed so that the observed inequality is only due to different preferences and choices (and some residual luck). So, equality of opportunity is just in the sense that it recognises individual responsibility and inequality that is beyond the individual’s control.

Whether dealing with plurality, conflicting claims, or equality, the requirement of justice is to favour and foster the common good of the relevant community and the basic aspects of human flourishing. This means conforming to a standard (procedural justice) and taking no more than one’s share (distributional justice). In realising the common good, there are two issues to resolve: first, what is required for individual wellbeing, which arises in relationships and dealings between individuals and/or groups in a community; and second, how to distribute resources, opportunities, and advantages. But there is also a perception problem.

The perception of justice has an impact on the stability of human interactions. To suffer from an unjust social structure implicitly entails the recognition that something ‘legitimate’ has not been granted. We are deprived of some social good that should exist. To ignore the identity, ability, or contributions of individuals to their community is unjust. Justice is then measured according to a society’s ability to ensure conditions of mutual recognition, where identity formation and individual self-realisation can develop (Honneth 2004).

A sense of injustice undermines the basis for a cohesive and resilient group. Similarly, a sustainable and balanced set of social relationships could favour social justice. Involvement in the community is key for justice. In some theories, the basic supreme principle is equality of participation (Fraser 2010), which requires equality in the distribution of material resources, regardless of differences of sex, age, race, or any other characteristic of the participants. In this view, redistribution has priority over recognition and representation.

Democratic equality integrates the principles of distribution with demands for equal respect, reconciling equality of participation and recognition (Anderson 1999). It guarantees citizens who follow the law equal access to the social conditions for their effective freedom. It justifies the required redistribution by appealing to the obligations of citizens in a democratic state. Since the fundamental objective of citizens in the construction of a state is to ensure the effective freedom of all, the distributive principles of democratic equality are not intended to tell people how to use their opportunities (for which they have a legitimate claim), nor do they seek to judge how responsible a person is for the choices that may lead them to unfortunate results.

Justice as recognition, participation, or democratic equality can be rightfully claimed against the agent imparting it, which in turn has the obligation of dispensing justice. The state has that role, since the administration of justice is a public good practically impossible to provide privately. And the state has the duty to do so, since it is the social mechanism that amalgamates individual values into social choices.

Three kinds of actions are required from the state in matters of justice: to govern the relationship of subjects to the state, to be in charge of the state’s relationship with its citizens, and to regulate the relationship of one private person or entity to another. To effectively impart justice in these matters, it has to be enforceable in society, which requires some kind of collective action. The governance of the nexus of the common good is closely connected to the ability to dispense justice, which in turn can enhance the potential for good governance.

4. Measuring Justice

As can be seen from the previous discussion, to measure justice directly or indirectly is a multidimensional and complex exercise. It involves taking into account plurality, rights and duties, and equality. It can be procedural or distributional. The materials of justice can be resources, capabilities, opportunities, recognition, participation, or equal respect. Justice involves the willingness of agents to acknowledge and/or modify the circumstances of possible injustices, the resources and authority granted to attend injustices, the perception that conflicts are solved, and the quality of institutions and rules to administer justice.

To complicate matters more, strictly speaking, justice cannot be reduced to a separate dimension on its own, isolated from the agency, humanity, stability, and governance components of the nexus of the common good. To do so means ignoring justice’s full scope (see Chapter 2), and implies that a modest measurement should concentrate on the most salient elements of a particular idea of justice, sacrificing many of its components, since the whole complexity of the concept is beyond the scope of a specific measure.

Another constraint is the availability of relevant information. To obtain a proxy for the relevant concepts, many compromises have to be made in terms of the definition of variables and their interpretation. Even then, space and time comparability are not possible sometimes, so it is necessary to work with more limited information. But the measurement exercise demands us not to stop there. For practical diagnosis and public policy, the measures should be simple, transparent, and replicable.

In what follows the focus is on the distinction between justice as a procedure and distributive justice. The first emphasises the violation of rights and freedoms, while the other requires that available resources and entitlements be shared according to relevant criteria. In the second case, the key emphasis is on the difference between end results and opportunities. The basis for measurement is the set of available indices that can be explored at the local level.

I. Justice as Freedom

Perhaps the most basic idea of justice is its protections for individual freedom, conceived as the absence of obstacles, barriers, or constraints, in such a way that an individual is able to take control of her own life and realise her fundamental purpose (negative liberty). In the words of John Locke (1689), freedom implies that an individual should not ‘be subject to the arbitrary will of another, but freely follow his own.’ Thus, justice poses stringent limits on coercion and state intervention, even beyond protecting the right not to be subjected to the action of another person or group (negative rights).

A way to measure this conception of justice is through negative liberty indices. There is a plethora of composite indices covering the subject (see the inventories by Bandura 2011, and Yang 2014), but the most salient are the Human Freedom Index (Cato Institute, Fraser Institute, Friedrich Naumann Foundation), the Economic Freedom of the World Index (Fraser Institute), the Index of Economic Freedom (Heritage Foundation), Freedom in the World (Freedom House), and the Democracy Index (Economist Intelligence Unit).

In their simplest terms, these indices measure noninterference by others. They are focused on procedural justice, in which the right means justify any and all results. Respect for human integrity, private property, and voluntary contracts is the basis of justice. But not all indices are restricted to this concept, and sometimes they include the removal of constraints that impede the fulfilment of potential, as the individual understands it. Typically, following Hayek (1960), the first three indices listed above ignore a broader concept of freedom.

For example, the Human Freedom Index (HFI) focuses on the absence of coercive constraint to human agency in the world, based on a broad measure that encompasses personal, civil, and economic freedom. It uses objective and perception data obtained by experts; its sub-dimensions include the rule of law, security and safety, movement, religion, association, assembly, civil society, expression and information, identity and relationships, size of government, legal system and property rights, access to sound money, freedom to trade internationally, and regulation of credit, labour, and business.

An example is the HFI for six different countries (see Table 2). Mexico is second to last in the selected group.

Table 2. Human Freedom Index for selected countries.

|

Country |

||

|

United Kingdom |

8.49 |

14 |

|

United States of America |

8.46 |

15 |

|

Spain |

8.12 |

29 |

|

Chile |

8.15 |

28 |

|

Mexico |

6.65 |

92 |

|

Brazil |

6.48 |

109 |

Source: Vásquez and Porcnik (2019).

There are at least ten other indices similar in conception to the HFI, but focusing on particular sub-dimensions of the index, mostly on economic and political freedoms. Another group of indices emphasises the rule of law and access to effective and impartial institutions of justice.

It should be noted that measures similar to the HFI are sometimes complex and demanding in terms of data and information, and sometimes not relevant for subnational political units since many negative freedoms are a matter of national institutions or public policies. However, at least a number of the components of the HFI have been disaggregated at the subnational level.

Mexico’s HFI, like that of other countries, is composed of two indices: a personal freedom index and an economic freedom index (see Table 3). The first considers basic civil rights, the second economic liberties, such as a smaller government, a solid system of property rights, sound monetary institutions, freedom to trade, and few regulations.

Table 3. Components of Mexico’s Human Freedom Index.

|

Country |

Index Value |

Ranking (162 countries) |

|

6.38 |

106 |

|

|

6.93 |

76 |

|

|

6.65 |

92 |

Source: Vasquez and Porcnik (2019).

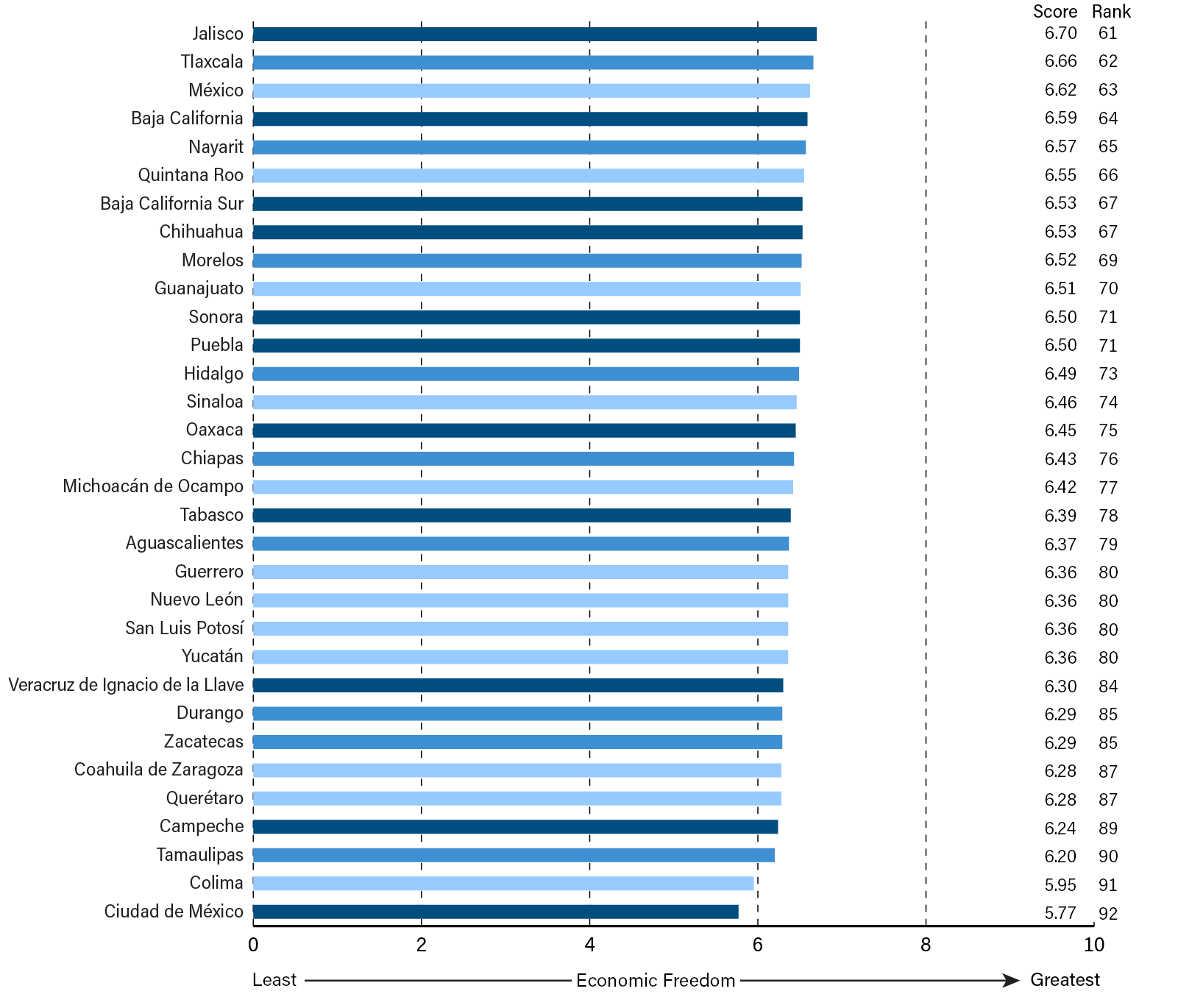

Stansel, Torra and McMahon (2019) have calculated an index for the Mexican states as part of their analysis of North America for the Economic Freedom of the World Index; see Figure 2 for their classification of the Mexican states according to economic freedom. However, many national indicators had to be dropped since they are not features of subnational units. This problem increases with the level of disaggregation to the point that it is extremely difficult to measure negative rights at the municipal level.

Figure 2. Economic Freedom Index of Mexican states by quartiles. Source: Stansel, Torrea and MacMahon (2019).

II. Justice as Equality of Results

An alternative conception of justice goes beyond negative liberties and rights, requiring a substantially equal distribution of advantages. In this distributive justice approach, resource and welfare egalitarianism are two central notions. Fundamental to justice from this perspective is the principle of equal concern and respect for persons, meaning that equal resources or welfare should be guaranteed to each member of society. People are morally equal, and equality in resources or welfare is the best way to further this moral ideal.

A more elaborate account of the argument in favour of resource egalitarianism asks, if one is an egalitarian, should one try to equalise resources available to agents, or try to equalise their welfare? With a suitably general conception of what resources are, equality of resources cannot be distinguished from equality of welfare (Roemer 1986). A practical implication of this result is that every person should have the same level of alienable resources and, if possible, be compensated for those inalienable ones.

In resource egalitarianism, there is the problem of the construction of appropriate indices, because it is necessary to measure the aggregate level of goods if they are to be distributed efficiently, that is beyond an egalitarian distribution of each and every good. Money is an imperfect index for the value of material goods and services. Nevertheless, using a monetary value, either for income or wealth, is the most common response to the index problem.

An additional difficulty is the choice of an inequality index, since each measure embodies different properties and value judgments (Sen 1973). Because inequality indices aggregate all income differences with different weights, they implicitly embody value judgments about which gaps matter most. Atkinson (1970) argued that such judgments should be explicit about the social welfare function underpinning each index and should avoid the indiscriminate use of any index, understand the welfare implications of their weights, and try to make explicit the associated ‘inequality-aversion.’

The most common index for measuring income inequality is the Gini coefficient. If income is distributed equally, the Gini is zero; if all income is concentrated in one person, the Gini has a value of one. As a result, the Gini coefficient can be interpreted as the percentage of the maximum inequality present in the current distribution of resources. The Gini coefficient—along with other commonly used measures—is a consistent measure that satisfies several principles (e.g., if a poorer person makes a transfer to a richer person, the measure should record a rise in inequality, regardless of where they are in the distribution).

Here is an example of the Gini coefficient as a measure of distributive injustice (see Table 4). With a different ranking than the HFI, Mexico is now in fourth place.

Table 4. Income Gini coefficients for selected countries.

|

Country |

Gini coefficient Value |

Gini coefficient Ranking (138 countries) |

|

Spain |

0.35 |

97 |

|

United Kingdom |

0.36 |

88 |

|

United States of America |

0.41 |

56 |

|

México |

0.47 |

33 |

|

Chile |

0.52 |

18 |

|

Brazil |

0.55 |

13 |

Source: UNDP (2020).

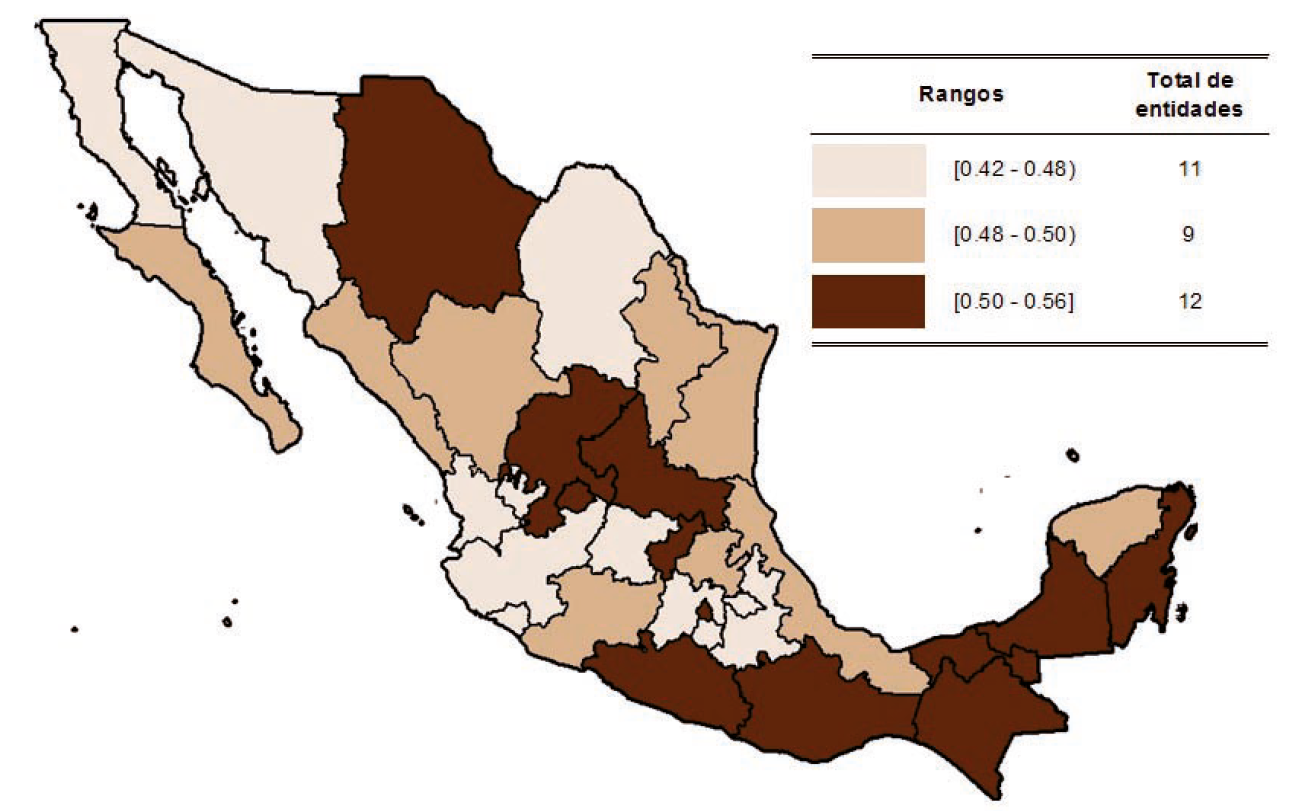

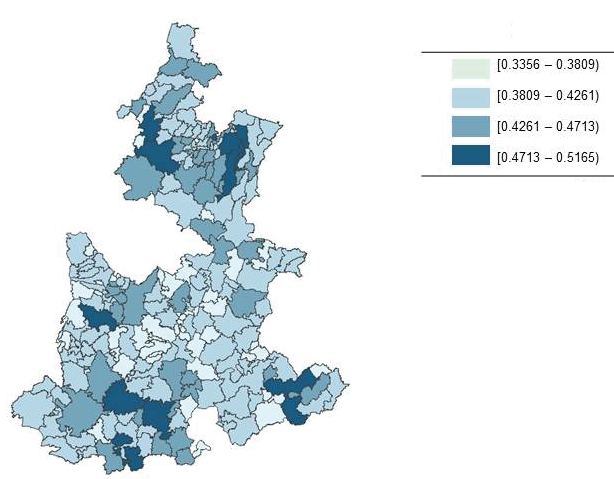

The information necessary to calculate Gini coefficients at the subnational level is increasingly available, at least for income, and income distribution is relevant for identifying local conditions that impact the wellbeing of households and individuals in small political units. Mexico’s National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) releases such information at the state level every two years (see Figure 3) and at the municipal level every five years (see the example of the state of Puebla in Figure 4) (Coneval 2020).

Inequality of results, as measured by the Gini for household or individual income, however easy to calculate, is not a convincing way to illustrate a lack of justice, since inequality not only ignores the process leading to outcomes but also oversimplifies the connection between resources and welfare. Also, as discussed in Section 2 above, inequality does not consider effective freedom, and there is no place for individual responsibility.

Figure 3. Income inequality of Mexican states by Gini ranges. Source: Coneval (2020).

Figure 4. Income inequality of Puebla municipalities by Gini ranges. Source: Coneval (2020).

III. Justice as Equality of Opportunity

One problem with the concept of justice as protection of negative rights is that it ignores the different sets of possible beings or doings open to individuals. In other words, equality of treatment does not imply equality of effective freedoms. On the other hand, pursuing justice as an equality of final resources ignores, among other things, the role of individual choice in economic outcomes. That is, even if equality of results means equality of effective freedoms (which is not necessarily implied), it can undermine individual responsibility.

A central question of distributive justice might be formulated in this way: under what conditions are the protection of liberties and the distribution of final resources just or morally fair? One reasonable answer is that justice requires equality of opportunity, which means that non-chosen inequalities should be eliminated to give equal initial conditions and a fair framework for interaction to all individuals (Roemer 1998). The idea is that justice requires a degree of protection of negative rights and a level playing field so that individual choices play out and dictate the final results.

The conception of equality of opportunity is a component of a theory of justice, but not the only component, even if it is the central core. Justice requires at least leveling the playing field by rendering everyone’s opportunities equal (Anderson 1999). When fully elaborated, this view specifies both to what extent it is not morally acceptable that some people are better off and the level of inequality that is implied (Brunori, Peragine and Ferreira 2013).

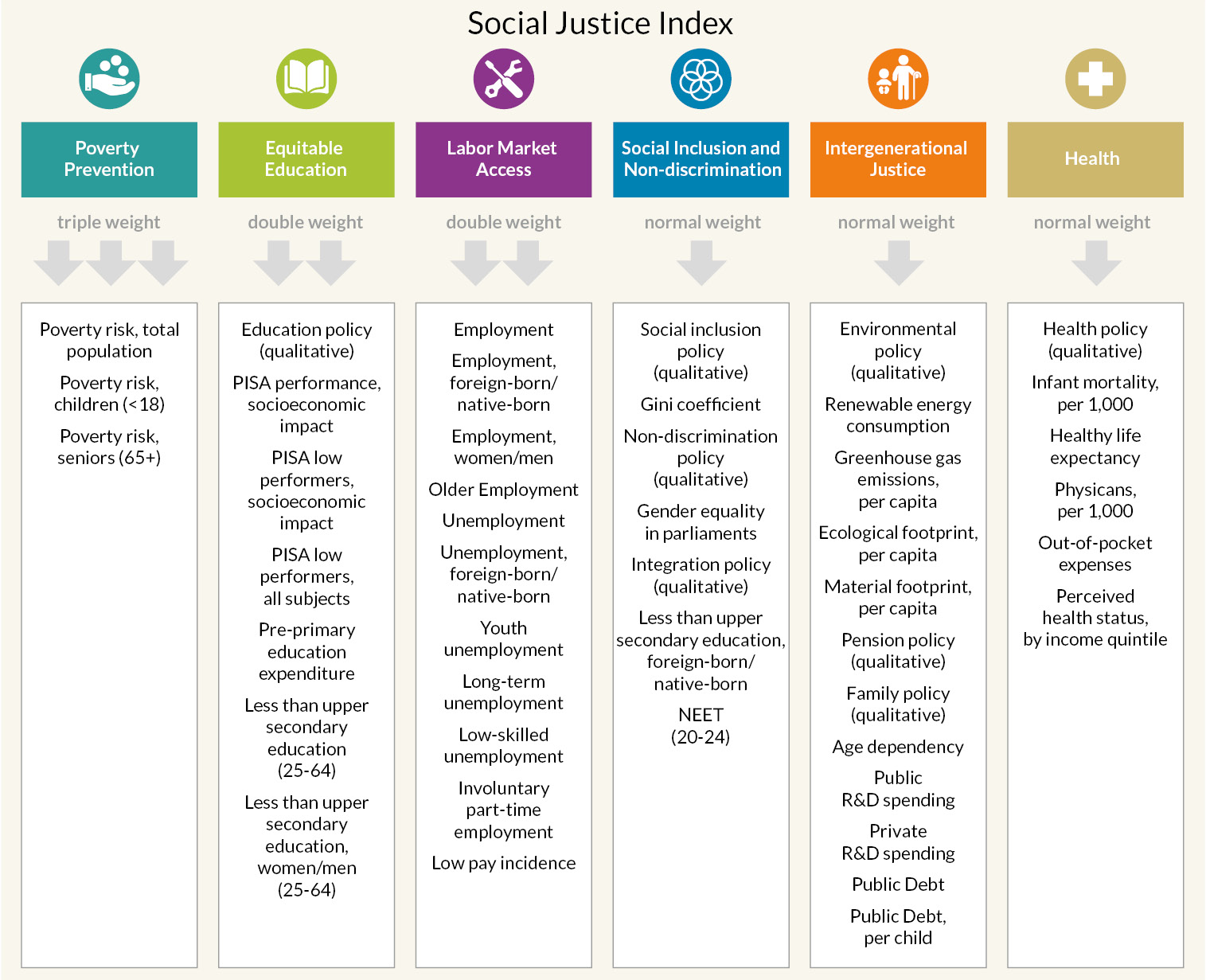

One example of this approach to measuring justice is the EU and OECD Social Justice Index (SJI) (Hellman, Schmidt and Heller 2019). The Social Justice Index is informed by the paradigm that, within the scope of his or her own personal freedom, every individual should be empowered to pursue a self-determined life course, and that specific unequal starting points should not be allowed to negatively affect self-realisation. By focusing on opportunities for personal development, such a concept of social justice avoids the blind spots of formal procedural justice on the one hand and equality-of-results distributional justice on the other. The SJI takes into account the following:

Instead of an ‘equalizing’ distributive justice or a simply formal equality of life chances in which the rules of the game and codes of procedure are applied equally, [… the] concept of justice is concerned with guaranteeing each individual genuinely equal opportunities for self-realization through the targeted investment in the development of individual ‘capabilities.’[…] Thus, within the scope of his or her own personal freedom, every individual should be empowered to pursue a self-determined course of life, and to engage in broad social participation. (Hellman, Schmidt and Heller 2019).

Following Merkel and Giebler (2009), the SJI is concerned with six dimensions: poverty prevention, access to education, labour market inclusion, social cohesion and non-discrimination, health, and intergenerational justice. The index comprises twenty-one quantitative and eight qualitative indicators. The data for the indicators is derived from OECD databases and from evaluations by experts responding to a survey on various policy areas. In order to ensure compatibility between the quantitative and qualitative indicators, all indicators are collected or undergo a linear transformation to give them a range of 1 to 10. More weight is given to the first three dimensions of the SJI (poverty, education, and labour). Figure 5 summarises the components of the index.

Figure 5. Social Justice Index dimensions and variables. Source: (Hellman, Schmidt and Heller 2019).

An example of the values and the rankings provided by the SJI can be seen in Table 5. Again, the ranking differs from the previous tables, and Mexico is in sixth place. (The Brazil information is not available, so for this table it is replaced by Turkey because of the similarities in economic development between Mexico and Brazil).

Table 5. Social Justice Index for selected countries.

|

Country |

||

|

United Kingdom |

6.64 |

11 |

|

Spain |

5.53 |

28 |

|

United States of America |

5.05 |

36 |

|

Chile |

4-92 |

37 |

|

Turkey |

4.86 |

40 |

|

Mexico |

4.76 |

41 |

Source: (Hellman, Schmidt and Heller 2019).

The shortcomings of the SJI are similar to those of the HFI: the information needed to calculate the index at the subnational level is demanding, and many of the indicators depend on national policies rather than on local conditions. However, it is possible to propose a more rigorous version of the inequality of opportunities approach that is simplified and requires less information.

The existing literature has two main approaches to measure inequality of opportunity, the non-parametric and the parametric. The first defines types of individuals according to their circumstances (e.g., parents’ years of schooling) and calculates the inequality between types to obtain an index of inequality of opportunity (e.g., educational inequality of the present generation). The second finds the correlation between relevant variables from the two generations and uses this parameter as an index of inequality of opportunity (in fact, the square of the correlation coefficient; see Ferreira and Gignoux 2011).

Each method has advantages and limitations, but the second is convenient because of its simplicity, since it has a built-in partition of individuals and a selection of inequality measures. Thus, a very simple indicator of inequality of opportunities corresponds to the percentage of the inequality of results transmitted from one generation to another. This indicator is directly related to the correlation between the results of one generation and the next (e.g., between parents’ education and that of their children).

Table 6 shows an example of the values and the rankings provided by the Intergenerational Correlation of Educational level (ICE) as an index of inequality of opportunity. This time, in this new ranking, Mexico improves its position with respect to Brazil and Chile.

Table 6. Intergenerational correlation coefficient in education for selected countries.

|

Country |

ICE Value |

ICE Ranking (44 countries) |

|

United Kingdom |

0.31 |

39 |

|

Spain |

0.45 |

19 |

|

United States of America |

0.46 |

16 |

|

México |

0.47 |

14 |

|

Brazil |

0.59 |

5 |

|

Chile |

0.60 |

4 |

Source: Velez, Campos and Huerta (2013).

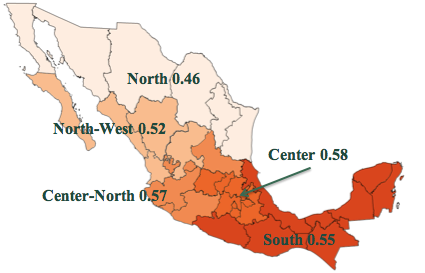

One advantage of the ICE is that it can be calculated at the subnational level. In the case of Mexico, it is already available for several regions (see Figure 6) and a proxy can be calculated at the state level with data from the Household Income and Expenditure Survey provided by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography.

Obtaining information at the municipal level would require conducting an ad-hoc survey that asks the respondents for retrospective information about their parents’ schooling because no current source has the necessary data. Another route would be to use imputation techniques to obtain proxies for the relevant inequalities (Elbers et.al. 2002).

Figure 6. Intergenerational correlation of education by regions. Source: Own calculations with ESRU-EMOVI (2017).

5. Towards a Local Survey to Measure Justice of the Common Good

The dimension of justice should capture the local-level collective processes and institutions through which people share common goods (in their valuation, production, and transmission). The common good metric for justice should seek to understand this dimension in a broad sense, paying attention to both the formal presence of institutions (procedural justice) and the final distribution of goods and opportunities (distributional justice).

From this perspective, the dimension of justice should capture citizens’ perspectives on institutions, current distributive results, and intergenerational inequality of opportunities. Justice in these three forms could be measured in relation to three common basic goods: rule of law; inequality of basic opportunities (health, education, and employment); and intergenerational transmission of inequality of opportunity.

The dimensions of justice should be measured in terms of rights, distribution of current opportunities, and intergenerational transmission of inequality of opportunity, according to the survey questions laid out in Table 7.

Table 7. Basic questionnaire for the measurement of justice at the local level.

This basic set of questions could be extended to the necessary means to preserve freedoms and rights (i.e., police resources, absence of corruption, the way the judicial system works), to the distribution of other basic resources (i.e., wealth, income, consumption), or to other ways to measure the transmission of opportunities (i.e., persistence of socioeconomic status, social mobility, coefficient of determination in multiple regressions). However, the questions in the table define the indispensable information needed to measure the dimension of justice for the common good.

Conclusion

There are several implications of the analysis previously laid out in this chapter:

- To measure the basic aspects of justice, the metric should capture justice’s procedural and distributional dimensions. A measure of those dimensions should focus on institutions’ effectiveness in protecting freedoms and rights in a narrow sense, on current distributive results, and on intergenerational inequality of opportunities. Justice in these three forms could be measured in relation to the rule of law, inequality in health, education, and employment opportunities, and the intergenerational transmission of inequalities.

- Justice conceived as limitations on what people can do to others to avoid coercion or the unacceptable loss of autonomy seems to be more a matter of agency than of opportunities to be free. However, procedural justice demands only particular ways to establish social relationships within the nexus of the common good.

- The conception of justice as protection of negative rights has a limited scope but is a key ingredient to defend the agency aspect of freedom. It is unsuitable as a measure of distributive justice, not only because it ignores effective freedoms, but also because it is insensitive to the effect of end results on social welfare.

- If the objective is to measure the basic aspects of distributive justice at the municipal level, the equal opportunities approach has conceptual advantages, although it requires making geographical imputations of the simplest correlation index or surveys representative of municipalities. Both exercises are technically feasible, but represent very different strategies in terms of the research involved and its costs.

- The equal opportunities approach can be elaborated to include multiple dimensions (correlations between the achievements of parents and children can involve, for example, health, occupational position, and income) and even address public policy interventions, such as the EU and OECD Social Justice Index. The greater the number of dimensions and components in the selected index, the lower its viability or relevance in the calculations for a particular municipality.

- While income inequality indices are relatively easy to calculate, it is difficult to justify them as indicators of distributive justice. Equality of resources, although it has its advocates, generally implies ignoring the agency of individuals or their differences to transform resources into effective freedoms.

- The complexity of the concept of justice makes any of its measurements a pale reflection of what we are trying to measure. In particular, any indicator of justice must not be isolated from other elements, such as the notions of agency, governance, stability, and humanity.

- The concept of the common good, designed to evaluate the good of a situation, involves not only the positions but also the relationships between the individuals, with the solidarity between them particularly important. Solidarity among the members of a group implies concern for those who are in a disadvantaged position, which translates into providing equal opportunities to progress on their own. Hence, equality of opportunity is also a relevant concept to measure this aspect of the common good.

The formalisation of the concept of the common good as ‘social conditions that individuals provide as relational obligations to shared interests’ has a long way to go in providing better grounds for the measurement of its components. Justice as what we owe each other is not completely captured by the current measures. But sometimes an imperfect measure is the only thing we need to avoid patent injustice.

References

Anderson, S. E. 1999. What Is the Point of Equality?, Ethics 109, 287–337.

Bandura, R. 2011. “Composite indicators and rankings: Inventory 2011”. Technical report, Office of Development Studies, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), New York.

Berlin, I. 1969. “Two Concepts of Liberty”, in Berlin, I., Four Essays on Liberty, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brunori, P., Peragine, V., and Ferreira, F. 2013. Inequality of Opportunity, Income Inequality and Economic Mobility: Some International Comparisons, IZA Discussion Paper No. 1755. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2210795

CONEVAL. 2020. Cohesión social, https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/Paginas/Cohesion_Social.aspx.

Elbers, C., Lanjouw, P., Mistiaen, J., Özler, B., and Simler, K. 2002. Are Neighbors Equal? Estimating Local Inequality in Three Developing Countries, Washington, DC: World Bank. https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/are-neighbours-equal-estimating-local-inequality-three-developing-countries

ESRU — EMOVI. 2017. Encuesta ESRU de Movilidad Social en México (ESRU — EMOVI). https://ceey.org.mx/contenido/que-hacemos/emovi/

Ferreira, H. G. F. and Gignoux, J. 2008. “The Measurement of Inequality of Opportunity: Theory and an Application to Latin America. Policy Research Working Paper No. 4659, Washington, DC: World Bank,https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6859.

Finnis, J. 2011. Natural Law and Natural Rights, New York: Oxford University Press.

Fraser, N. 2010. Scales of Justice. Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World, New York: Columbia University Press.

Hayek, A. F. 1960. The Constitution of Liberty, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hellmann, T., Schmidt, P., and Matthias Heller, S. 2019. Social Justice in the EU and OECD, Index Report 2019, BertelsmannStiftung. https://www.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Social-Justice-Index-2019.pdf.

Honneth, A. 2004. Recognition and Justice: Outline of a Plural Theory of Justice, Acta Sociologica 47/4, 351–364, https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699304048668.

Hussain, W. 2018. “The Common Good”, in Zalta, E. N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/common-good/.

Locke, J. and Hollis, T. (ed.) 1764 (1689). The Two Treatises of Civil Government, London: A. Millar et al., 1764, Liberty Fund, at Online Library of Liberty, https://files.libertyfund.org/pll/titles/222.html.

Merkel, W. and Giebler, H. 2009. “Measuring Social Justice and Sustainable Governance in the OECD”, in Bertelsmann Stiftung (ed.), Sustainable Governance Indicators 2009. Policy Performance and Executive Capacity in the OECD,Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 187–215.

Roemer, E. J. 1986. “Equality of Resources Implies Equality of Welfare”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 101, 751–784, https://doi.org/10.2307/1884177.

Roemer, E. J. 1996. Theories of Distributive Justice, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, E. J. 1998. Equality of Opportunity, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, E. J. 2010. Kantian Equilibrium, Scandinavian Journal of Economics 112/1, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2009.01592.x

Sen, A. 1973. On Economic Inequality, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sen, A. 1980. “Equality of what?”, in McMurrin, S. M. (ed.), Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sen, A. 1985. Commodities and Capabilities, Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Sen, A. 1987. On Ethics and Economics, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Sen, A. 1993a (2002). Positional Objectivity, Philosophy & Public Affairs 22/2, 126–145. Reprinted in Sen, A. 2004. Rationality and Freedom, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. 1993b. “Capability and Well-Being”, in The Quality of Life, edited by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 30–53.

Sen, A. 2009. The Idea of Justice, Cambridge, Mass: Belknap/Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095382081100046X

Stansel, D., Torra, J., and McMahon, F. 2019. Economic Freedom of North America 2019, Fraser Institute.

UNDP. 2020. Income Gini coefficient, https://hdr.undp.org/en/content/income-gini-coefficient.

Vasquez, I. and Porcnik, T. 2019. Human Freedom Index 2019, Cato Institute, the Fraser Institute, and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. https://www.cato.org/human-freedom-index/2019

Williams, B. 1973. “A Critique of Utilitarianism”, in Smart, J. J. C. and Williams, B., Utilitarianism: For and Against, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 82–118. Reprinted as “Consequentialism and Integrity”, in Scheffler, S. (ed.) 1988. Consequentialism and its Critics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 20–50.

Yang, L. 2014. An Inventory of Composite Measures of Human Progress, Occasional Papers, UNDP Human Development Report Office. https://hdr.undp.org/en/content/inventory-composite-measures-human-progress

1 Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesias.