12. Re-Engagement and Motivation

© 2022 S. Hallam & E. Himonides, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0292.12

Active engagement with music has been shown to support the positive development of young people who are from areas of high deprivation and may be at risk of disaffection, not fully engaged with education, exhibiting poor behaviour or involved in the criminal justice system. Music has also been found to help with the rehabilitation of prisoners and their successful reintegration into society. This chapter begins by setting out the various influences on an individual’s motivation, followed by an exploration of evidence as to how active engagement with music may contribute to bringing about change.

Motivation

Lack of motivation is a problem in formal education across much of the developed world. There is concern about high levels of student boredom and disaffection, high dropout rates, poor attendance and poor behaviour leading to exclusions from school, particularly in urban areas. Some students report viewing school as boring, or as a game where they try to do as well as they can with as little effort as possible. Disaffection increases as students progress through school, particularly in the final years of compulsory education. These issues are particularly acute in boys, some ethnic minorities and those with special educational needs. Young people from lower socioeconomic groups are underrepresented in higher education, and those who take up opportunities to participate in formal education as mature adults tend to be those who have already been relatively successful. There is a substantial group of individuals whose motivation is insufficient to sustain engagement with formal learning in the short-, medium- and long-term.

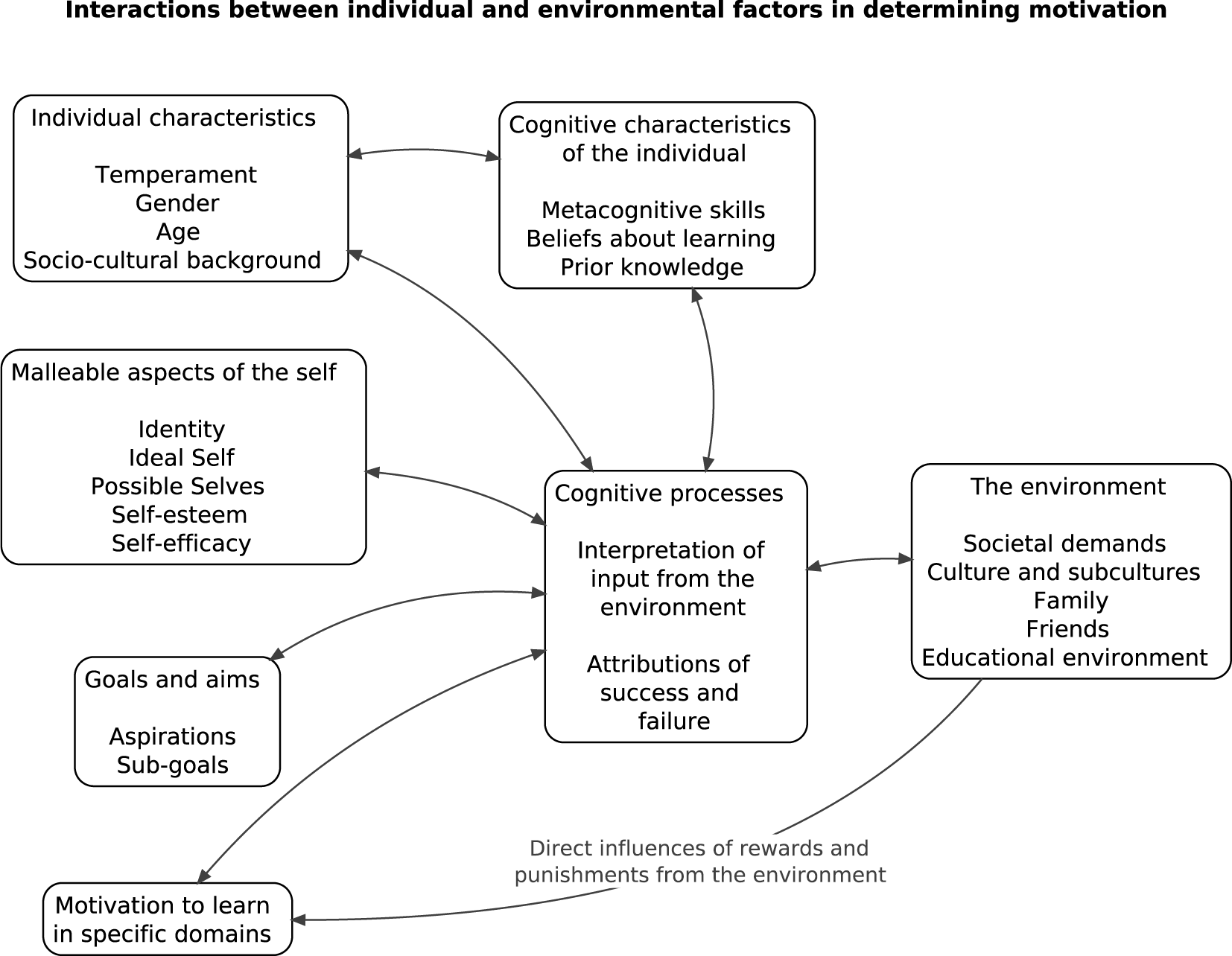

The complex interactions which occur between the environment and the individual which influence self-development, motivation and ultimately behaviour are set out in Figure 12.1. An individual’s identity or self-concept represents the way he or she thinks about him or herself and his or her relationships with others (Mead, 1934; Rogers, 1961; Sullivan, 1964). Identity is developed in response to feedback received from the environment. The desire for social approval, particularly from those we admire and respect, leads us to behave in particular ways. Over time, values and beliefs leading to behaviour associated with praise are internalised. Positive feedback from others raises self-esteem and enhances confidence. Identity develops as a result of these processes. The family has a crucial role to play in this process in the early years but as the child’s social contacts broaden, others (including teachers and peers) become important. Individuals set themselves goals, which determine their behaviour. Goals are influenced by identity, ideal and possible selves, as well as environmental factors. Behaviour is the end link in the chain, but at the time of enactment, it too can be influenced and changed by environmental factors. There is interaction between the environment and the individual at every level in the long- and short-term. Individuals can also act upon the environment to change it or seek out new environments more conducive to their needs.

Behaviour is influenced by the individual’s interpretation of situations and events, their expectations and the goals that they have, which mediate and regulate behaviour (Mischel, 1973). While each individual has needs and desires, these are tempered by consideration of the consequences of actions prior to attempts to satisfy them. Cognition plays a role in the ways in which we attempt to enhance our self-esteem, leading us to attribute our success or failure to causes which will allow us to maintain a consistent view of ourselves. When a learner has completed a learning task successfully, this will have an impact on self-esteem and motivation which will be carried forward to subsequent learning tasks. Conversely, when learning outcomes are negative, motivation is usually (but not always) impaired.

There are complex interactions between learning and motivation. The more successful and enjoyable our learning in a domain, the more likely we are to be motivated to continue engaging with it. At the same time, the more interested and motivated we are in a domain, the more likely we are to persist when we fail or face difficulties, particularly if we believe that, ultimately, we can be successful. If early engagement with learning in a particular domain is enjoyable and positively rewarded, self-efficacy beliefs are supported and learning continues. This brings further rewards and a positive possible self develops in that domain-enhancing motivation and increasing persistence for the future. Motivation to learn is related to identity and the goals individuals set for themselves in the short-, medium- and long-term. The value attached to learning tasks is related to the extent to which they support this developing identity and the goals derived from it. Throughout life, an individual will engage with learning across several domains and it is inevitable that they will be more successful and interested in some domains than others, and that some will be more closely linked with their personal goals. From time to time, personal goals may be in conflict and individuals may have to make choices based on their relative importance. The difficulty during the years of compulsory schooling, and on occasion after that (when individuals may be required to undertake further training), is that in these circumstances the individual’s freedom to choose what and how to learn is removed. If there is little relationship between personal goals and those determined by the educational system and teachers working within it, then motivation is likely to be poor and learners are likely to become disaffected. The more closely the goals of learners, teachers and educational systems are matched, the more likely that effective learning will occur. Motivation is crucial in how well children perform at school and is closely linked to self-perceptions of ability, self-efficacy and aspirations (Hallam, 2005). Actively engaging with music can help enhance motivation and change behaviour through changing self-beliefs and aspirations, and through the transferable skills that it can develop. A study by the Norwegian Research Council for Science and Humanities supported this, finding a connection between having musical competence and high motivation, which led to a greater likelihood of success in school (Lillemyr, 1983). There were high correlations between positive self-perception, cognitive competence, self-esteem, and interest and involvement in school music.

Motivation Developed through Engagement with Music

The process of learning to play an instrument or sing frequently requires hours of practice, typically in solitude, and a commitment to music even when there are competing curricular and extracurricular activities. This may foster motivation-related characteristics (Evans, 2015; Evans and Liu, 2019). Students who learn that repeated music practice can lead to the mastery of complex skills and the achievement of desired outcomes (such as positive examination outcomes or successful performances) develop a mastery-focused learning approach (Degé and Schwarzer, 2017). This may lead to the internalisation of a sense of self-efficacy, which may then be applied to learning in non-musical domains.

Bandura (2005) suggests that efficacy beliefs are multifaceted, although they may covary across distinct domains of functioning. Self-efficacy developed in one area of learning may generalise to other areas. For instance, self-efficacy developed through learning in music may generalise to other areas of learning, particularly when similar subskills are involved. Similarly, self-regulation acquired through music may generalise to other areas. Such transfer of self-efficacy or other motivation-related characteristics is plausible given the parallels between music education and traditional academic subjects. Instruction and feedback are required for both, and there are tangible outcomes in relation to examinations or performance. Self-efficacy is associated with achievement (Caprara et al., 2011), while mastery-learning and self-efficacy develop in an iterative, mutually reinforcing manner (McPherson and Renwich, 2011). Some research has demonstrated how recognition for achievement in music, leading to high levels of self-efficacy, can enhance self-efficacy and self-esteem, which then transfers to motivation for other schoolwork. For instance, McPherson and O’Neill (2010) found that students who were engaged in learning music reported higher competence beliefs and values and lower task difficulty across all school subjects in comparison with those not engaged in making music. Overall, having experience of learning to play an instrument or sing enhanced motivation for other school subjects.

Burnard (2008) explored the attempts of three secondary-school music teachers to re-engage disaffected young people through music lessons. They reported that they democratised music-learning, emphasised creative projects and used digital resources. Similarly, the Musical Futures project was designed to devise new ways of engaging young people (aged 11 to 19) in music activities. Initially, this entailed young people working in small groups, learning to copy recordings of popular music by ear. A large-scale evaluation of the project showed that the music teachers perceived students to be more motivated, better behaved and demonstrating higher levels of participation, greater focus, enhanced musical skills, more confidence, improved small-group and independent-learning skills, and enhanced leadership skills. Those who benefited the most were lower- and middle-ability students (Hallam et al., 2017). The pupils themselves reported improved listening skills and an impact on other schoolwork, including less reliance on the teacher, enhanced concentration and using music to help with other subjects (for instance, making up songs to help with remembering facts). Team-working skills also transferred to other lessons (Hallam et al., 2018). Non-music staff in the participating schools also reported that the Musical Futures approach had had a positive impact on student motivation, wellbeing, self-esteem, concentration, organisation, attitudes towards learning, progression and team-working (Hallam et al., 2016).

Similarly, students randomly assigned to weekly piano lessons over the course of three years demonstrated gains in self-esteem, particularly its academic dimension, whereas a control group showed no such gains (Costa-Giomi, 2004). A quasi-experimental study revealed that students who received a higher number of music lessons over several years reported gains in academic self-concept that were unmatched by those in a comparison group (Rickard et al., 2013). Positive relationships have also been reported between the number of music lessons taken and academic self-concept (Degé et al., 2014) and higher levels of musical engagement (Degé et al., 2014; Degé and Schwarzer, 2017). The experiences of students in musical groups may also contribute to a general sense of accomplishment and collaboration, which may support enhanced interactions in school, leading to a more positive school climate, greater academic achievement and decreased disaffection (Rumberger and Lim, 2008).

Figure 12.1: Model of motivation

Children and Young People Facing Challenging Life Circumstances

Children born into areas of high deprivation face considerable life challenges. Typically, they only acquire low-level skills and qualifications, and in adulthood they are less likely to be employed and more likely to have lower earnings than those from more affluent areas (Blanden et al., 2008). Other long-term consequences include those relating to health (mental and physical) and involvement in criminal activity (Feinstein and Sabates, 2006). Parental involvement in their child’s education, lack of cultural and social capital, negative experiences at school, low aspirations and exposure to multiple risk factors are all implicated in the relationship between deprivation and poor educational outcomes. In relation to music, there is some evidence that children from deprived areas are less likely to have played a musical instrument (Scharff, 2015) and are more likely to have negative experiences with instrumental teachers, interpreting this as their own failure and feeling less comfortable and confident learning classical music (Bull, 2015).

Group music-making offers the opportunity to engage in wider cultural experiences, explore new ideas, places and perspectives, and support social cohesion through broadening experience (Israel, 2012). This not only benefits participants but also increases parents’ attendance at cultural events and their exposure to culture more generally (Creech et al., 2016). A range of musical projects have focused on the role that music can play in enhancing the lives of vulnerable children, providing them with a range of transferable skills. Some of these programmes will be discussed here, while others will be addressed in detail in Chapter 16, which addresses issues of social inclusion (for instance, the inclusion of refugee children), while Chapter 14 considers programmes supporting the psychological wellbeing of children from war zones.

Music can be a vehicle for re-engaging young people in education and supporting those who are at risk in making changes in their lives. The context within which projects operate is important for their success, as are the musical genres adopted and the quality of the musical facilitators. Deane and colleagues (2011) found that, whilst music-making acted as a hook in terms of initial project engagement, it was frequently the building of a trusting and a non-judgemental relationship between a young person and their mentor that supported change.

El Sistema and Sistema-inspired Programmes

Internationally, the largest group of programmes supporting children living in deprived areas and at risk of disaffection are El Sistema programmes and those inspired by El Sistema. El Sistema was founded in 1975 as social action for music by Jean Antonio Abreu. It was premised on a utopian dream in which an orchestra represented the ideal society—and the idea was that, if a child was nurtured in that environment, it would be better for society. El Sistema has survived through many different administrations and has a large network of youth and children’s orchestras. In addition, there are many programmes around the world which have been inspired by El Sistema and share its values. The goal of El Sistema is to use music for the protection of childhood through training, rehabilitation and the prevention of criminal behaviour. Evaluations of El Sistema or Sistema-inspired programmes show that they offer a safe and structured environment which ensures that children are occupied and at reduced risk of participating in less desirable activities (Creech et al., 2013; 2016). Evaluations of individual programmes report that children’s sense of individual and group identity is enhanced and that children take pride in their accomplishments. They show increased determination and persistence, and become better able to cope with anger and express their emotions more effectively (Creech et al., 2013; 2016).

Raised Aspirations and Motivation for Learning

In England, Lewis and colleagues (2011) showed that participants in a Sistema-inspired programme, In Harmony, exhibited more positive attitudes and improved behaviour. Parents and teachers indicated that the pupils had a greater sense of purpose and self-confidence, and their aspirations were raised. This was, in part, attributed to contact with role models in the form of the In Harmony teachers and other visiting artists (Lewis et al., 2011). A prominent theme reported in the evaluation of Big Noise, Scotland (GCPH, 2015) was the raised aspirations of participants. The researchers reported qualitative evidence demonstrating enhanced motivation, determination, willingness to be challenged, and the ability to imagine and achieve goals, particularly amongst the secondary-school participants. In particular, the aspirations of the 15- to 16-year-olds were raised (GCPH, 2015). Qualitative interviews with 35 parents of children involved in Big Noise, Scotland (Gen, 2011a) provided strong evidence that they considered the programme to have enriched their children’s lives. Twenty-nine parents took part in a quantitative survey, which revealed a positive impact attributed to Big Noise with regard to confidence, friendships, hope for the future, happiness, concentration and behaviour.

Not all of the research on Sistema-inspired projects has been positive. For instance, Rimmer (2018) explored children’s reflections on the value of their participation in the English programme, In Harmony. Interviews were undertaken with 111 primary-school children aged six to eleven, from three programmes in Newcastle, Telford and Norwich. Parents, siblings and the school environment were all important in the way participating children viewed the programme. The value of engaging with music in the family was particularly important in influencing the children. Challenges in handling or holding instruments—and perceptions of the sounds created as somehow lacking in desirable qualities—emerged. The absence within the programme of some of the valued visual, representational and kinetic aspects of popular music emerged in many accounts. The compulsory nature of In Harmony participation contrasted with the valued dimensions of popular music-related activities which were associated with freedom, choice, self-directedness and play.

Raised aspirations were noted by Uy (2010) in the Chicago núcleo of Chacao, where all of the students were enrolled in high school, university or conservatoires, with 40 percent of those studying music while others pursued careers in engineering, medicine or other subjects. In comparison with other underprivileged communities, Uy described this as astounding. Other programmes reported similar raised aspirations and self-beliefs, including The Boston Conservatory Lab Charter School (2012), El Sistema Colorado (2013), In Harmony Stockton, Kalamazoo Kids in Tune, KidZNotes, OrchKids, The San Diego Community Opus Project, YOLA, The People’s Music School Youth Orchestras and El Sistema Chicago. Numerous USA programmes have included measures in their evaluations which demonstrate the successes they have achieved in realising motivational goals (Case, 2013; Duckworth, 2013; In Harmony Stockton, 2013; Orchestrating Diversity, 2013; Silk et al., 2008; and Smith, 2013—for a review, see Creech et al., 2013; 2016). Other programmes report similar findings. For instance, Devroop (2009) explored the effects of music tuition on the career plans of disadvantaged South-African youth and found positive outcomes, while Galarce and colleagues (2012) reported that academic aspirations had improved as a result of engagement in the programme and that students were less likely to procrastinate in their schoolwork. Similarly, Cuesta (2008) found that 63 percent of participants achieved better outcomes in school compared with 50 percent of non-participants, while Wald (2011) researched two Sistema-inspired programmes in Argentina and found evidence of enhanced motivation and commitment. Programmes in Scotland and Ireland also showed enhanced aspirations, engagement with learning and improved behaviour (Kenny and Moore, 2011). In their review, overall, Creech and colleagues (2013; 2016) concluded that raised aspirations were one of the most frequently cited positive outcomes of El Sistema and Sistema-inspired programmes.

In some programmes (for instance, In Harmony Liverpool) changes in aspirations were not restricted to the children participating in the programme but extended across the community. Burns (2016) showed progress in academic attainment at age 11, enhanced musical attainment, and enhanced perceptions of children’s social and emotional wellbeing. Parents and carers noted changes in musical ability, communication, confidence, focus, concentration and behaviour. As families engaged with the musical activities and the children took home new skills and shared them with other family members, there was a direct impact on family life. Individual aspiration and community pride changed, creating a virtuous cycle of change. In what was perceived as a severely deprived area, residents now saw some hope. Also working in Liverpool, Robinson (2015) found that parents participating in the research were actively supporting their children and felt that their lives had been transformed, as their children developed new skills and had greater opportunities, experiences of other places and a greater appreciation of music.

In an evaluation of all of the English Sistema-inspired programmes, Lord and colleagues (2013) collected evidence through pupil surveys, including a matched-comparison sample drawn from schools not participating in In Harmony, as well as case study interviews. The findings showed improvements in pupils’ attitudes to learning, self-confidence, self-esteem, wellbeing and aspirations to improve. This was borne out by the national inspection agency for schools, Ofsted, whose reports highlighted pupils’ social, emotional and spiritual wellbeing. They attributed this (at least in part) to participation in In Harmony. These positive wellbeing outcomes were thought to be influenced by the group work ethic which involved discipline, focus and teamwork. Comparison between the well-established In Harmony programmes in England (Liverpool and Lambeth) with more recently established programmes revealed statistically significant differences with regard to children’s application of self to learning and their view of their future prospects. Children from the more established In Harmony schools who had participated in the programme for longer had more positive scores, suggesting that the programme had had a positive impact with regards to dispositions towards learning and future aspirations. When the established In Harmony schools were compared with matched-comparison schools not accessing In Harmony, statistically significant differences were also found in relation to application of self to learning and children’s views of their future prospects, as well as self-assurance, security and happiness. It seemed that, over time, the programme impacted on children’s wellbeing, leading them to become young, confident learners with clear future aspirations.

An evaluation of a summer residential orchestral programme also demonstrated the impact on personal wellbeing amongst participants (NPC, 2012; Hay, 2013). Thirty-five young people aged nine to eighteen, including some with special educational needs, completed a survey of wellbeing before and after the course. While caution must be exercised in interpreting the data—as the sample size was small—there were indications of enhancement in self-esteem, emotional wellbeing, resilience and life satisfaction. A large effect size was reported for each of these measures, although the girls seemed to benefit more than the boys. Compared with national baseline scores for these measures, boys’ post course scores for self-esteem and resilience were in the top quartile of what might be expected in a national sample.

Uy (2010) carried out a cross-cultural comparison of El Sistema in Venezuela and the USA, and reported consistency with regard to positive outcomes relating to personal development. Overall, parents and students from both contexts reported improvements in focus and discipline, time management, relaxation and coping, communication, ability to work with others, academic performance and aspirations, creative thinking, and self-esteem. In South America, considering the impact of the Batuta, Colombia programmes, which offer strategies for social, educational and cultural development, and support the national system of youth orchestras in Colombia, Cuéllar (2010) drew on key findings from the CreCe report (Matijasevic et al., 2008). Qualitative data provided examples of personal development similar to those reported elsewhere. Students reported positive changes in respect, tolerance, honesty, solidarity, teamwork, sense of responsibility and emotional regulation which helped control aggressiveness, intolerance and impatience. Self-esteem was enhanced, particularly self-efficacy, through feeling competent. Students also reported greater self-care, resilience, happiness and enhanced aspirations. Their social networks were greater and there were enhanced family interactions.

Many USA programmes identified elevated aspirations and goals as key to bringing about change. They included in their evaluations measures to assess these, which demonstrated their success (Case, 2013; Conservatory Lab Charter school, 2012; Duckworth, 2013; In Harmony Stockton, 2013; Orchestrating Diversity, 2013; Renaissance Arts Academy, 2012a; 2012b; 2013; Silk et al., 2008; Smith, 2013; The People’s Music School Youth Orchestras - El Sistema Chicago, 2013). For instance, the Renaissance Arts Academy in Los Angeles demonstrated elevated academic and professional aspirations in their students as a result of participating in an academically and musically rigorous intense programme. Their high graduation rate of 100 percent, coupled with the percentage of students who continued their education at university, 95 percent exemplified the huge transformations that occurred, in terms of not only what students believed they could accomplish, but also the goals and expectations that they set for themselves as a result of this realisation. Accomplishments in music and the arts transferred to their beliefs about their academic capabilities, and their elevated goals and achievements in both these areas showed the shifts that can take place in possibilities as a result. Many other programmes have measured and reported raised aspirations and greater self-esteem amongst students. In the Caribbean, OASIS—a Sistema-inspired orchestral programme established for youth at risk—showed that, after a six-month period of participation, students were significantly less likely to be provoked to anger and display aggressive behaviours including teasing, shoving, hitting, kicking or fighting, or to be involved with delinquent peers. They also had higher educational aspirations. After 18 months, the findings showed positive overall outcomes (Galarce et al., 2012). In terms of academic aspirations, 62 percent of the OASIS group, as compared with 41 percent of a control group, expressed hopes to be able to obtain a doctoral degree. Increases in self-regulation were also seen. Seven percent of the OASIS group, as compared to 21 percent of the non-OASIS students, reported speaking inappropriately to others. They were also less likely to report that pleasurable activities prevented them from achieving their work goals and were less likely to procrastinate in their schoolwork, be involved in fights, or use alcohol or marijuana. After the six-month stage, the results from the Haitian programme were similar to those of Jamaica, with OASIS students being significantly less likely to be angered easily, less likely to be involved in aggressive behaviours and to have delinquent peer relationships. Within 18 months, the results for Haitian OASIS students mirrored those of Jamaica in terms of academic aspirations, with 80 percent as opposed to 61 percent hoping to attain a doctoral degree. They were also less likely to have disagreements with parents or caregivers, and were more likely to be involved in sports.

Self-Beliefs

Positive self-beliefs regarding what can be achieved (self-efficacy) and what is possible (possible selves) are crucial to motivation. El Sistema and Sistema-inspired programmes have prioritised the personal and social development of participants, and many evaluations point to the positive impact of the programme on self-beliefs (Esquaea Torres, 2001; 2004; Galarce et al., 2012; Israel, 2012; Uy, 2010). Participation in two Argentinean Sistema-inspired orchestras was explored by Wald (2011b) who found that students, parents, coordinators and directors perceived participation in the orchestras as being related to self-esteem, self-worth, self-confidence, and pride about achievements, motivation and commitment. Frequent opportunities for performance helped to raise aspirations (Billaux, 2011) and created safe opportunities for risk-taking (Uy, 2012) which allowed children to experience success on many occasions, enhancing their self-efficacy and self-esteem.

School Attendance and Positive Attitudes towards School

Creech and colleagues (2013; 2016), in their review of El Sistema and Sistema-inspired programmes, showed that a major area of focus for many American programmes was the impact on students’ rates of attendance and punctuality at school. Several programmes documented positive evidence regarding school attendance, including Austin Soundwaves (2011-2012), In Harmony Stockton (2013), Kalamazoo Kids in Tune (2013), KidZNotes (2012), OrchKids (Potter, 2013), The Renaissance Arts Academy (2012a; 2012b; 2013), The San Diego Community Opus Project (Smith, 2013), and the YOURS programme (2013). Evaluation findings in America showed that Sistema participants generally increased their attendance at school. The B Sharp Programme (Schurgin, 2012) reported a decrease in absenteeism between 2012 and 2013, from an average of 6.5 days to 4.5 days per child. Many Sistema participants attended schools where the majority of students qualified for free or reduced-price school meals. Attendance rates at schools attended by Sistema students had higher than state or local average evaluation results in the USA, and showed that Sistema students generally had improved attendance at a higher rate than the average for their schools.

In England, the primary school at which In Harmony Liverpool is based saw a drop in absence from almost eight percent in 2009 to six percent in 2012 (Burns and Bewick, 2012). This compared with a sector average of five percent. Although absenteeism rose in 2010, an analysis of attendance rates between 2009 and 2013 showed an overall significant improvement, with a school average rate of absence of 6.5 percent by 2013 (Burns and Bewick, 2013). In contrast, in Scotland there was no evidence showing that involvement in Big Noise improved attendance (Gen, 2011a), although qualitative data did suggest that the programme was making a difference in this regard. More recently, the 2015 report suggested that the programme was associated with improved school attendance. In Raploch, school attendance was 93 percent among Big Noise participants, four percent higher than the eligible population. Govanhill school data showed attendance among Big Noise participants to be almost 93 percent—nearly two percent higher than the eligible population (Glasgow Centre for Population Health, 2015). In Canada, Morin (2014) found no improvements in school attendance, although in New Zealand, Wilson and colleagues (2012)—reporting on Sistema Aorearoa—indicated that there was a reasonable improvement in overall attainment, engagement and social skills in school, but insufficient data to comment on attendance. Overall, although the data relating to attendance is mixed, there is some evidence of enhanced achievement.

Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties

Alemán and colleagues (2017) assessed the effects of a Sistema-inspired music programme on children’s developmental functioning in the context of high rates of exposure to violence. The trial was conducted in 16 music centres during 2012 and 2013. In total, 2,914 children aged six to fourteen participated, with approximately half receiving an offer of admission to the programme in September 2012 and half in September 2013. The children in the treatment group participated for one semester more than the control-group children. After one year, there was evidence of improved self-control and reduced behavioural difficulties. The effects were larger among boys and children with less educated mothers, especially those exposed to violence. Following participation in the programme this group exhibited lower levels of aggressive behaviour. The programme improved self-control and reduced behavioural difficulties, with the effects concentrated among subgroups of vulnerable children. In Columbia, Castaneda-Castaneda (2009) explored the impact of intensive guitar workshops offered as part of a rehabilitation programme on young people in a youth detention centre. The findings showed improvements in musical and citizenship skills.

Transferable Skills

Parents and teachers of children participating in some of the El Sistema or Sistema-inspired programmes referred to the way that the programme developed transferable skills, including concentration (Hallam and Burns. 2018). One parent commented:

‘The impact on the kids is enormous, the concentration. I’ve got nephews in other schools and the difference is huge. Our kids can sit there in a massive big place listening to classical music without coughing or fidgeting and sit there and be well behaved for that length of time. There’s not many primary kids who can do that. We’ve got special education kids as well and they can do that.’

Another parent emphasised the impact on learning more generally. ‘These children are dedicated to this. Other areas of her learning have come on in leaps and bounds because of this. Without a doubt it is the music.’

Some parents recognised the impact on confidence. ‘Their confidence has gone up sky high. She says she’s really nervous but she seems calm.’ Another parent commented: ‘The music brought my daughter out of her shell into a confident young lady.’ Some of the older students were able to self-reflect on the wider benefits of participation:

‘You learn things from it that you don’t learn at school. You learn lots of skills for life and you make links with people, like being able to talk to new people, like being able to work on things, so like, team work, listening to others. So even if you don’t want to do music for a career, in five years’ time you’ll have those skills and you’ll be able to say I learnt this in orchestra and it will have paid off.’

The young people were also able to develop leadership skills from the mentoring that they were engaged with. This was recognised by staff and parents.

Music Interventions Unrelated to El Sistema

There are several music interventions in addition to El Sistema or Sistema-inspired programmes which have been designed to support disadvantaged children. For instance, Pasiali and Clark (2018) worked with 20 children aged five to eleven years old on a programme that consisted of eight 50-minute music sessions, where teaching social skills through song lyrics and improvisation were central. Social competence, antisocial behaviour and academic competence were assessed, and the outcomes showed that the number of low-performance, high-risk skills decreased significantly, while teacher assessment indicated significant improvement in communication and a decrease in hyperactivity, autistic behavioural tendencies, overall problem behaviours and internalisation. Parent ratings generally mirrored those of teachers. Similarly, Millar and colleagues (2020) reported positive outcomes for the COOL project, a 12-month intervention which involved 16 sessions of participatory music-making with 32 hard-to-reach young people aged 12 to 17. The programme aimed to increase confidence and self-esteem, and improve social skills through music that resonated with the young people’s lived experience.

One study examined the impact of a singing programme, Sing Up, on 48 children and young people (Hampshire and Matthijsse, 2010). The findings indicated that participants’ self-confidence and aspirations were enhanced, and that they developed new friendships and better connections with parents. However, Hampshire and Matthijsse cautioned that children and young people from privileged backgrounds benefited more than those from disadvantaged backgrounds, as the latter risked rejection by their existing friends due to the programme being perceived as cheesy or gay. This emphasises the importance of any musical intervention being seen as relevant to the participants.

School music lessons themselves can be therapeutic. For instance, in a case study of a general music class in a Spanish public secondary school, undertaken with disaffected learners who had received a total of 130 reprimands throughout the school year for poor behaviour and systematically rejecting school rules, Rusinek (2008) established that they enjoyed their music lessons. This may have been because the music teacher generated enthusiasm through an inclusive pedagogy in which the principle of ‘music for all’ was adopted. Arrangements for percussion instruments, in four to twelve parts, of pop, classical and film music were played by each class. The goal of performance was shared by the children and the teacher, and was widely accepted as an important part of school culture. Similarly, an Australian study showed that a group of boys who were identified with behavioural issues who engaged in a proactive music-making activity showed notable improvements in both classroom cooperation and self-esteem. The drumming exercises in the programme were among the most popular and connected closely to the participants’ sense of maleness. The activities were fun and provided opportunities for students to enhance positive values such as group cohesion and self-esteem, along with their behavioural and social competence (Smith, 2001).

Drumming seems to be a particularly effective form of musical intervention when children are disaffected. It can support anger management, team-building and substance-abuse recovery, leading to an increase in self-esteem and the development of leadership skills (Mikenas, 2003). Group drumming can foster a sense of cohesion, as it teaches coordination and teamwork, with participants having to assume different roles and work together (Drake, 2003). Faulkner and colleagues (2012) developed a drumming programme as a way of engaging at risk youth, while simultaneously incorporating themes and discussions relating to healthy relationships with others. The evaluation of the programme with a sample of 60 participants in Western Australia’s wheatbelt region used quantitative and qualitative methods, including informal discussions with staff and participants, observation, participant and teacher questionnaires, and school attendance and behavioural incident records. The findings showed an increase in scores on a range of social indicators that demonstrated increased connection with the school community. Also in Australia, O’Brien and Donelan (2007) reported on the effectiveness of the creative arts as a diversionary intervention for young people at risk. In this three-year government-funded study, ten arts programmes were conducted across urban and rural areas. The findings demonstrated that arts programmes could have a significant and positive impact on marginalised young people, offering opportunities for skill development and social inclusion, while in Canada, Wright (2012) argued that music education in schools could lead to social transformation

Research on the impact of music-making on children living in care (looked-after children) in the UK has shown that engagement in high-quality music-making projects can support the development of resilience in dealing with challenges. Salmon and Rickaby (2014) researched how developing a musical play could facilitate skills development, improve mental health and strengthen resilience in young people in care. Participants were able to develop new skills, confidence and resilience, and felt more socially connected. In a review, Dillon (2010) showed that music-making could contribute to improved negotiation skills and cooperative working; learning to trust peers; developing the capacity for self-expression and a stronger sense of self-awareness; increased self-discipline and responsibility; a sense of achievement; feelings of belonging and shared identity; and the opportunity to make friends and develop positive relationships with adults. Music-making provided respite from problems and opportunities to have fun. In addition, there was evidence of increased confidence and the acquisition of a wide range of skills. In Norway, Waaktaar and colleagues (2004), in a study of young people who had experienced serious and or multiple life stresses leading to behaviour difficulties, found that a music programme was able to enhance resilience. Positive peer relationships and self-efficacy also improved when the young men demonstrated coherence and creativity as they produced a music video for public viewing. Zanders (2015) also showed how music therapy could support young people in foster care, helping to create stability and find resources and meaning in their lives to promote healing, addressing the displacements, abuse, grief and loss that many had experienced. In England, the evaluation of the Youth Music mentoring programme, which included a total of 419 mentees, showed that participants were aware of the musical opportunities available to them and had increased their agency (as assessed by feeling respected, capable and in control). Mentees indicated enhanced ability to work with others, express themselves, respect other people’s views and be punctual (Lonie, 2011). Similarly, Brown and Nicklin (2019) explored the impact of a global youth-work project that aimed to engage young people in social issues through the medium of hip hop. Most participants—who were from a range of British ethnic backgrounds—were not in education, employment or training, or were otherwise identified as marginalised, due to having a criminal record or being excluded from mainstream education. The project aimed to challenge the exclusion implied by labels such as ‘marginalised’, and value participants’ experiences, aiming to engage them with global and social issues. The sessions ran over three years and considered financial independence, political identity and mental health, with an overarching focus on money, power and respect. Activities were creative, including lyric-writing, art, interviews and developing tracks to build self-esteem. The outcomes showed that the project built self-esteem and positive attitudes to learning. Participant perceptions suggested that the programme provided them with positive experiences of learning and skills development, thus enhancing self-esteem and reducing risk factors for antisocial behaviour. Hip hop was used to connect young people to social issues and engage them in learning, developing their transferable skills and building confidence, as well as increasing their employability, prosocial behaviour and engagement with social issues. Sessions were interactive, facilitating dialogue and providing peer mentoring. Studio facilities with recording equipment were available. Data included project reports, interviews, field notes, session plans and feedback. The findings suggested that opening informal spaces with opportunities for creative experiential learning (such as hip hop) had positive outcomes for young people and facilitated engagement with prosocial behaviours.

A review of 15 projects funded by Youth Music (Qa Research, 2012) showed a range of positive outcomes associated with engaging those not in education, employment or training, or those at risk, in music-making activity. Outcomes included increased motivation to engage in education, employment or voluntary activity, including gaining qualifications, heightened aspirations and a more positive attitude towards learning. Participants also developed a range of transferable skills, including basic academic skills, listening, reasoning and decision-making, concentration, focus, team-working, time-keeping, goal-setting and meeting deadlines. There was also evidence of enhanced wellbeing including increased self-esteem, self-respect, pride, empowerment, sense of achievement and confidence, and an expansion of friendships, trust and improved relationships with adults. Aggression, hyperactivity and impulsivity decreased as participants learned to control their emotions. The projects also broadened horizons, including increased awareness of different cultures and traditions.

An evaluation of the European Social Fund project, Engaging Disaffected Young People (Lancashire Learning Skills Council, 2003), found that music and sport activities could encourage participants back into learning by changing negative attitudes and perceptions towards education. Following completion of the project, 85 percent of the 173 project participants were working towards a qualification. Alvaro and colleagues (2010) evaluated the pilot phase of the European Union’s E-motion project, which was designed to utilise youth-friendly music software in order to engage 14- to 17-year-olds who had dropped out of school, or who were at risk of dropping out. Three experimental pilot programmes were delivered to groups containing between 19 and 26 students in single schools in three different countries: Italy, Romania and the UK. Teachers completed a scorecard for each student at the beginning and end of each programme. Overall, there were improvements in a range of basic academic skills and personal skills including listening, speaking and alcohol avoidance. Interviews also indicated a reduction in offending, antisocial behaviour and substance abuse and, for some participants, enhanced interest in schoolwork, improved school attendance, attention, self-confidence, self-belief, motivation, cultural awareness and communication skills.

School Attendance and Attitudes towards School

Taetle (1999) investigated the relationship between daily school attendance and enrolment in fine arts electives. Three secondary schools participated. Students were divided into three groups according to their elective participation: fine arts courses only, non-fine arts courses only, and a combination of fine arts and non-fine arts courses. Students were then stratified according to grade point average (low or at risk, medium and high). Attendance rates were computed as a percentage of days absent. The findings showed that students with lower absence rates had a higher grade point average, students not enrolled in fine arts electives had significantly higher absence rates than those students with at least one fine arts elective, and students with a low grade point average (at risk) who were not enrolled in fine arts electives had significantly higher absence rates than those students who were enrolled in at least one fine arts elective. Similarly, Oreck and colleagues (1999) reported that participants in an arts-based programme stated that their involvement enabled them to make friends, establish support networks, and feel accepted and valued. Davalos and colleagues (1999) examined extracurricular activity, perception of school, ethnic identification, and the association with school retention rates among Mexican American and white non-Hispanics. Participants engaging in extracurricular activities were considerably more likely to be enrolled in school than were those not participating. Similarly, Lashua (2005) and Lashua and Fox (2007) studied a recreation project that taught young people aged 14 to 20, mainly from Aboriginal backgrounds, to make their own music using computers and studio production software. They showed how participants with literacy problems were able to create complex, spontaneous rhymes through the medium of rap. The participants reported that the programme was meaningful and made school more enjoyable, helping them to stay out of trouble. Activities such as rap battles provided an acceptable outlet for aggression and enabled participants to demonstrate their skills, gain respect and learn humility.

The Integration of Young People with Special Educational Needs into Mainstream Education

Increasingly in Europe, young people with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties are taught in mainstream schools. This presents particular challenges for teachers. Many of these children have difficulties in learning, which may or may not be related to their behaviour. As a result, a prominent area of work in music therapy has become the integration of children with special educational needs. This is particularly the case in Germany and Italy, where government strategies have focused on the integration of children with special educational needs into mainstream schools. In Germany, Hippel and Laabs (2006), Kartz (2000), Koch-Temming (1999), Kok (2006), Mahns (2002), Neels and colleagues (1998) and Palmowski (1979) have explored how music therapy could help children with special educational needs integrate into mainstream classrooms. Similarly, in Italy, Pecoraro (2006) reviewed how music therapy could help young children, some with special educational needs, to learn in mainstream classes, while D’Ulisse and colleagues (2001) also considered how music therapy could be applied in schools. In the UK, some student music therapists have focused on the role of music therapy in supporting children with special educational needs in mainstream schools (Carson, 2007; Crookes, 2012; Hitch, 2010).

Historically, improvisation with individuals has been the principal method adopted in music therapy (Darnley-Smith and Patey, 2003) but increasingly music therapists work in a range of different contexts, including in child and adolescent mental health services, with social services, and in educational settings. Working in schools is a developing area. Carr (2008) undertook a review of 57 relevant papers, 12 of which included outcomes. Although successive governments in the UK have been concerned with the wellbeing of children, in schools music therapy has played a limited role. In a review, Carr and Wigram (2009) found only ten papers which specifically addressed work within mainstream schools. The main recipients were children with mild emotional, behavioural or social problems. Different therapeutic approaches were adopted. For instance, Jenkins (2006) advocated a flexible approach, while Strange (1999; 2012) adopted client-centred music therapy for emotionally disturbed teenagers who had moderate language disabilities. Butterton (1993) used music in the pastoral care of emotionally disturbed children aged 13 to 18 using psychotherapy with music improvisation and drawing, while Nöcker-Ribaupierre and Wölfl (2010) described a preventative approach, introducing music therapy into two secondary boarding schools in Germany with the aim of helping students to express their emotional state and release aggressive tension. The project proved particularly successful in classes with migrant students from diverse cultures, who were able to communicate effectively through shared improvisation.

Pethybridge and Robertson (2010) suggested that music lessons in schools should consist of improvisation, which they believed had the potential to guide the student into areas of learning as a result of experiences acquired through musical interaction. Students from a language and communication unit attached to a mainstream school participated in their study, which involved child-led creative music-making and structured activities to enhance social skills. The findings showed that working in small groups led to greater ability to address educational objectives, both musical and non-musical. Further, Pethybridge (2013) evaluated ways in which music therapists might support teachers to offer interactive group music-making to children with additional support needs. Working with a nursery teacher, Pethybridge planned and delivered an 11-week intervention for three children on the autistic spectrum. The findings showed that experiential music therapy groups offered some level of transferable learning for teaching and support staff, and the potential for developing more indirect approaches. Derrington, in a series of papers (2004; 2005; 2010; 2011, 2012; Derrington and Neale, 2012) also argued for the need to offer music therapy in mainstream schools and pupil referral units to disaffected young people, with an emphasis on creative activities including song-writing, while McFerran (2020) reviewed the research literature in education, mental health and community music, suggesting that grouping knowledge in this way offered new perspectives on the types of programmes offered and the way that they were evaluated.

School-Based Music Therapy Interventions for Children with Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties

There are examples of the use of music therapy with young children. For instance, Brackley (2012) describes the increasingly common need for music therapy work in behavioural support programmes in pupil referral units for children aged between five and nine, who have been excluded from mainstream education. She referred to music therapy’s potential to recreate the conditions of the early mother-infant relationship, allowing the music therapist to revisit problematic stages of the pupil’s early development and aid their ego development. Similarly, De Silva (2006) also illustrated how music therapy could bring about radical transformation in the behaviour and emotional interaction of younger children, while Thomas (2014) undertook a qualitative case study of two primary-school children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties, one who exhibited withdrawn behaviour, the other poor behaviour. Music lesson interventions over a period of one year benefited the children in terms of personal competence, self-regulation, self-confidence and self-esteem; task competence, enjoyment, engagement, motivation, social competence, collaboration and social connectedness.

Montello and Coon (1999) also studied the impact of active and passive group music therapy with pre-adolescents with emotional, learning and behavioural disorders. Teachers were asked to rate and confirm changes in the students’ attention and motivation. After a period of four months, there were significant changes in aggression, brought about by the facilitation of self-expression, which provided a channel for frustration, anger and aggression. Similarly, Horton (2005) showed that group music therapy with female adolescents in an educational treatment centre—involving stepping, a series of body percussive movements such as foot-stamping and hand-clapping, and chanting or singing—significantly increased group cohesion. The participating adolescents were identified as being at risk of dropping out of school, and were engaged in violent and risky sexual behaviours. The stepping procedure promoted positive social behaviour.

Gold and colleagues (2001) assessed the benefits of music therapy for those with emotional and behavioural difficulties, and showed that children’s needs for relationships and opportunities for emotional expression were met by the therapy. In a review, Gold and colleagues (2004) analysed music therapy studies, comprising a total of 188 children and adolescents, and found that the benefits were greater for those who had behavioural problems. Similarly, McIntyre (2007) showed that nine weeks of music therapy with adolescent boys with behavioural and or emotional disorders helped them to develop new skills, enjoy music, experience group cohesion and increase self-esteem. Hirst and Robertshaw (2003) investigated the impact of the Otherwise Creative project, an intervention which involved a wide range of arts activities (including music production and song-writing), targeting young people in pupil referral units with a range of emotional and behavioural difficulties. Following engagement in the project, the participants demonstrated growth in confidence and self-esteem, and an enhanced ability to communicate with staff and to resist negative peer pressure. Chong and Kim (2010) examined how an after-school education-oriented music therapy programme impacted on students. The intervention lasted for 16 weeks and used musical activities to promote academic, social and emotional skills. A rating system completed by teachers assessed change and showed that social skills and problem behaviour improved significantly, although there were no improvements in academic competency.

Using drumming to promote self-expression, Ho and colleagues (2011) compared the effects of 12 weeks of school-counsellor-led drumming on social and emotional behaviour in two fifth-grade intervention classes, with two standard control classes. The children in the intervention classes improved significantly compared with controls on multiple areas of social and emotional behaviour, as assessed by their teachers. Thompson and Tawell (2017) studied the effects of an arts-based intervention on young people deemed at risk of school exclusion because of social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. Eleven young people aged 11 to 16 were studied using observations and interviews. The interventions offered to the young people provided alternatives to their personal, cultural and historical ways of experiencing the world. Experimenting with different arts media and trying out ideas enabled them to develop a new identity for themselves. The findings suggested that imagination, invoked through the intervention, helped the disengaged young people to change their perceptions of their future.

Sausser and Waller (2006) showed that, with proper planning of musical activities, students could benefit from a music therapy programme structured for the success of each individual. They reviewed how music therapy had been used with students with emotional and behavioural difficulties, and proposed a model of music therapy for students in a psychoeducational setting. The model was designed to combine the music therapy process with the nine-week grading period of the school setting. It suggested ways for music therapy and other therapeutic modalities to work collaboratively with students with emotional and behavioural difficulties.

Krüger (2000) set up work in a contemporary secondary school in Norway as part of a new strategy for helping secondary-aged students with emotional and behavioural problems. The students had been labelled as the ‘bad guys’ and were living up to this name. By gaining attention because of their challenging behaviour, they were able to maintain this role within the school. Krüger found the computer to be a source of new meaning for those who had not learned to play an instrument. Technology led to broad possibilities of exploring, mastering, arranging, creating and improvising music. Participants quickly became confident at using it and being in control. Krüger showed how one child who had threatened other pupils, had very low respect for authority and was difficult to talk to was able to engage in the therapy. Through the shared use of information technology, the process of developing a trusting and communicative relationship was enabled. Krüger reported how he encouraged the boy to master recording techniques but also allowed the child to express anger and shout at him to show that he would always be there. This helped to create a bond and the opportunity to talk about what was wrong in the child’s life. Ultimately, the process of using information technology led to a product, and the child became very involved in music-making, burning CDs and creating covers for the CD cases, selling his work and even publishing his music on school radio.

Some research has focused on interventions with children exhibiting highly aggressive behaviour. For instance, Choi and colleagues (2010) investigated 48 such children, who were allocated to either a music intervention or a control group. The music intervention group engaged in 50 minutes of musical activities twice weekly for 15 consecutive weeks. After 15 weeks, the music intervention group showed a significant reduction in aggression and improvement in self-esteem compared with the control group. These findings suggested that music could reduce aggressive behaviour and improve self-esteem in children with highly aggressive behaviours. Similarly, Hashemian and colleagues (2015) studied whether 12 90-minute music therapy sessions could reduce aggression in visually impaired Iranian adolescents compared with a control group matched in relation to age, socioeconomic status and the education level of parents. Two behaviour questionnaires showed a significant decline in aggression in the intervention group. Ye and colleagues (2021) carried out a meta-analysis of research, exploring whether music therapy could reduce aggressive behaviour in children and adolescents. Ten studies were included. The research showed a significant decrease in aggressive behaviour and a significant increase in self-control compared with control groups, whereas there were no differences in a music medicine group and the control group. Music interventions with durations of less than 12 weeks and more sessions per week were more efficient in reducing aggressive behaviour.

Some work has been undertaken with refugee students. For instance, Baker and Jones (2005; 2006) studied the effects of a music therapy programme in stabilising the behaviours of newly arrived refugee students. The research examined the effects of a short-term music therapy programme on changes to behaviour of 31 refugee youths attending an English-language reception centre in Brisbane. Two five-week intervention periods were employed, with group music therapy sessions conducted once or twice a week. The findings indicated that music therapy led to a significant decrease in externalising behaviours, with particular reference to hyperactivity and aggression.

One of the main aims of music therapy for children with emotional and behavioural difficulties is to address behaviour within the classroom. This is particularly prevalent in research in the USA. For instance, Eidson (1989) studied the effect of behavioural music therapy on the generalisation of interpersonal skills from therapy sessions to the classroom by middle-school students with emotional difficulties. Also in the USA, Haines (1989) studied the effects of music therapy on the self-esteem of emotionally disturbed adolescents and showed that music therapy enhanced group cohesion and cooperation. Krout and Mason (1988,) using computers and electronic music resources, worked with behaviourally disordered students aged 12 to 18, either in a self-contained or integrated classroom. Students had the option of enrolling in a music elective class which met three times each week, or of receiving individual music therapy services that focused on learning a musical instrument. Both programmes emphasised targeted social behaviours or skills while learning about music. Kivland (1986) noted the effect of individual music therapy sessions on self-esteem in an adolescent boy with a diagnosis of conduct disorder. Self-esteem was measured by frequency of both positive and negative self-statements, and by his ability to accept positive comments appropriately. By the twelfth week of therapy, he was able to list independently what he had done well at each session, and was able to accept positive comments from others appropriately. In addition, his ability to list what he had done well and what he needed to improve transferred to other disciplines. In Canada, Buchanan (2000), working in mainstream services, studied the effects of music therapy interventions with adolescents aged 15 to 19 who were designated as ‘at risk’. The intervention gave them an opportunity for self-expression in a group setting. Similarly, Cheong-Clinch (2009) studied the use of music as a tool to engage young people with English as a second language in a high school and a residential care facility, in particular newly arrived immigrant and refugee students.

Carr and Wigram (2009) identified existing research and clinical activity utilising music therapy with mainstream children, as well as a potential need for music therapy with this group of children. They undertook a systematic review relating to work with children in mainstream schools. Sixty papers were identified, 12 of which were outcome studies. There was evidence that music therapy was used with children in mainstream schools, both in the UK and abroad. They showed that the literature at the time of the review suggested that music therapy was effective in addressing the needs of mainstream schoolchildren—several therapists had documented the benefits of music therapy as a way to increase student’s self-esteem, address challenging behaviour, motivate learning and help develop interpersonal relationships (Procter, 2006), although more evidence was needed. Derrington (2012) studied whether music therapy could improve the emotional wellbeing of adolescents who were at risk of exclusion or underachievement. The research took place in a mainstream secondary school and its federated special school for students with emotional and behavioural difficulties. Over 19 months, the intervention group received 20 weekly individual music sessions, while a waiting-list comparison group received the same treatment later. Quantitative data were collected four times during the research from students, teaching staff and school records, while the students were also interviewed. Very few pupils dropped out and the majority of teachers reported improvement in students’ social development and overall attitude.

The Role of Rap and Hip Hop in Therapy in School Contexts

The cultural significance of music for youth populations has long been recognised, both in terms of the performance and production of music itself, and the stylised identities surrounding its consumption. Perhaps it is not surprising, therefore, that music-based interventions have been particularly effective at positively impacting the mental health and wellbeing of young people. The kind of music which adolescents prefer is related to their experience of emotional and behavioural difficulties (Took and Weiss, 1994), including expressions of anger (Epstein et al., 1990). Armstrong and Ricard (2016) suggest that rap, hip hop, and rhythm and blues provide a cultural lens, through which many urban adolescents forge identity and express themselves. The music therefore has the potential to combat emotional and interpersonal distress. Creative techniques that incorporate these genres of music can be used to help adolescents understand and regulate coping responses to difficult and emotionally sensitive situations. Schwartz and Fouts (2003), studying 164 adolescents who preferred light or heavy qualities in music or had eclectic preferences, found that each of the three music preference groups was inclined to demonstrate a unique profile of personality dimensions and developmental issues. Those preferring heavy or light music qualities indicated at least moderate difficulty in negotiating some aspects of personality and/or developmental issues, while those with more eclectic music preferences did not indicate similar difficulties. Despite this, when Gardstrom (1999) examined offenders’ perceptions of the relationship between exposure to music and their criminal behaviour, only four percent perceived a connection between their musical preferences and their deviant behaviour, although 72 percent did believe that the music influenced the way that they felt at least some of the time. Most believed that music mirrored their lives rather than being a causative factor in their behaviour. Music was perceived by some as being cathartic, and by some as only harmful when applied to pre-existing states of negative arousal.

In 2000, Elligan introduced rap therapy as a psychotherapeutic intervention for working with at-risk youths, primarily African-American males whose identities were highly influenced by rap music. Rap is able to engage a population of youth who often enter counselling apprehensively (Elligan, 2000; 2004; Allen, 2005). Gonzalez and Grant Hayes (2009) reviewed rap culture, its relationship to inner city youth and the benefits of Elligan’s rap therapy with at-risk youth. Kobin and Tyson (2006) also used rap lyrics as the impetus for therapeutic dialogue and the facilitation of empathic connections between clients and therapists. This aided in breaking the ice, encouraging participants to engage in projective narration, and helped the therapist to establish relevant, client-centred treatment goals. In Australia, de Roeper and Savelsberg (2009) showed that taking part in a community-based hip-hop culture project helped at-risk young people to develop confidence, skills, ambition and a stronger sense of identity, although they urged caution in interpreting the findings, as the data were limited.

Cobbett (2007) illustrated an integrative approach to working therapeutically with individual children experiencing emotional and behavioural difficulties, which combined music therapy with other creative therapies, particularly play therapy and drama therapy. In 2009, Cobbett developed the approach, suggesting that such interventions would be more effective if they were available in schools and utilised materials which were relevant to the young people concerned (e.g. rap music or electronic music). In 2016, Cobbett compared 52 young people receiving arts therapy—including music, drama or visual arts—and a control sample of 29 young people on a waiting list over a year-long period in two schools for children with emotional and behavioural difficulties. Two outcome measures were used: a staff-rated Goodman’s Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and a self-rated scoring system. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire outcomes showed a significant difference in improvement for those in the therapy group compared to the control group for all measures related to emotional and conduct difficulties. The effect sizes were large. Three out of four self-rated categories also showed significant differences in improvement between the groups. Interviews with six young participants suggested that the young people felt that the arts brought benefits that augmented verbal interventions. Examples from the interviews are set out in Box 12.1. In a further paper (2016b), Cobbett outlined a systemic approach which would further support young people.

Box 12.1: Teenagers’ comments about music therapy (derived from Cobbett, 2016)

Parker and colleagues (2018) undertook a small-scale, qualitative interview study in a secondary school over ten weeks with marginalised and at-risk children. The programme was delivered by a team of young people aged 18 to 25, the majority of whom had previous experience of the criminal justice system. They facilitated a single, two-hour music session once a week for approximately 15 pupils. All sessions took place during the course of the normal school day and consisted of a series of activities which involved lyric-writing, usually rap and composing beats, mostly using Logic Pro software on Mac computers, although those pupils who could play musical instruments also did so. The music they composed was recorded and performed. The 32 students aged 13 to 16 were selected to participate because their general behaviour had been disruptive and they had demonstrated defiant, angry, aggressive behaviour towards other pupils and teachers. To remain on the programme, they had to maintain positive interactions with other students and teachers. Some were considered ‘at risk’ because of previous involvement with the criminal justice system or involvement with gangs. The students revealed in the interviews that music-making increased their confidence, improved their attitudes towards teachers and peers, induced feelings of calm, and improved their communication skills. Parker and colleagues concluded that music-making activities could provide significant psychosocial benefits for young people, particularly when combined with mentoring support.

In a series of papers, Uhlig (2011a; 2011b; 2013; 2015) considered how the voice could be used as a primary therapeutic instrument. Initially, Uhlig worked with children with special educational needs in a public-school setting in New York. She showed that at-risk children demonstrated honesty in expressing their most personal desires and fears through vocal music therapy. Cursing, shouting, singing, rapping, chanting and song-writing helped them to survive their personal and familiar environments, and increased their learning potential. Together with the therapeutic relationship based on sharing rap, behavioural changes occurred. In later research, Uhlig and colleagues (2013) carried out a systematic review and reported that many studies had demonstrated the effects of music on emotion and emotionally evoked processes. In 2015, Uhlig and colleagues investigated the performance of rap-music therapy in a non-clinical, school-based programme to support the development of self-regulative abilities to promote wellbeing and to reduce the risk of low academic performance attributable to troubled mental health. All adolescents in Grade 8 of a public school were invited to participate, and randomly assigned to either rap-music therapy or to regular classes. The rap-music classes took place once a week over a period of four months. Measures of change were taken at four monthly intervals. Primary outcome data included measures of psychological wellbeing, emotion regulation, self-esteem, self-description, language development and executive functioning. Secondary outcome data consisted of the subjective experiences of participants collected in follow-up interviews with members of the experimental group. In 2016, Uhlig and colleagues carried out a survey in the Netherlands of the use of rap and singing by 336 qualified music therapists. The results indicated that rapping and singing applications in music therapy could enhance self-regulative skills during the process of emotional expression. Rapping occurred considerably less frequently than singing but was considered to decrease aggressive behaviour. Singing was applied daily and was associated with the support of deeper emotional involvement. However, the findings suggested the need for more consistent descriptions of therapeutic interventions using rap styles in music therapy practice, and the development of specialised protocols for research studying its effects. In 2018, Uhlig and colleagues investigated ‘rap and sing’ music therapy in a school-based programme designed to support self-regulative abilities. One-hundred and ninety adolescents in Grade 8 of a public school in the Netherlands were randomly assigned to participate or act as a control group. The intervention took place once a week over a period of four months. Significant differences between groups were found on the teacher Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire, indicating stabilisation in the ‘rap and sing’ music group as opposed to increased problems in the control group.

Porter (2012) also planned a trial to determine if improvised music therapy could lead to clinically significant improvement in communication and interaction skills in young people experiencing social, emotional or behavioural problems. In 2017, Porter and colleagues studied 251 children aged eight to sixteen with social, emotional, behavioural and developmental difficulties from six child and adolescent mental health service community-care facilities in Northern Ireland. The children were randomly allocated to 12 weekly sessions of music therapy in addition to their usual care, or acted as a control group. Follow-up occurred at 13 and 26 weeks. For participants aged 13 and over in the intervention group, communication was significantly improved, although this was not the case for their carers. Overall, self-esteem was significantly improved and depression scores were significantly lower at Week 13, although there was no significant difference in family or social functioning at this time point. While the findings provided some evidence for the benefits of the integration of music therapy into clinical practice, differences between subgroups and secondary outcomes indicated that further research was needed.

Olson-McBride and Page (2012) described the implementation of a specialised poetry therapy intervention, which incorporated hip-hop and rap music, with high-risk youths. The programme supported the young people’s use of self-disclosure. The intervention involved creative writing and the use of popular music, primarily from the rap and rhythm and blues genres, during the receptive prescriptive component of the session. In some sessions, the facilitator chose the music, but in others group members did so. Group members created a collaborative poem, a structured individual poem or an unstructured individual poem. The symbolic ceremonial component of the session involved group members reading the poems created during the session aloud to the group and soliciting appropriate feedback. Each poetry-therapy group intervention was ten sessions in length, lasting 45 to 60 minutes. Three interventions were conducted with participants selected from two facilities—an alternative school and a transitional living program designed to meet the needs of individuals between the ages of 12 and 21 who were deemed ‘at risk’ due to problems such as family poverty, family instability, academic problems and behaviour problems. The majority of group participants had histories of serious externalising behaviour problems. Some participants were in state custody as a result of involvement with the juvenile justice system. Data were collected for each group session via video camera. Overall, the intervention fostered a group environment in which guarded, difficult-to-engage, at-risk adolescents felt comfortable and connected enough to engage in surprisingly honest and bold self-disclosure, an initial step in addressing their problems.

Zarobe and Bungay (2017) undertook a rapid review exploring the role of arts activities in promoting the mental wellbeing and resilience of children and young people aged between 11 and 18. Only studies related to activities that took place within community settings, and those related to extracurricular activities based within schools, were included. Eight papers covering a wide range of interventions were included. It was found that participating in arts activities could have a positive effect on self-confidence, self-esteem, relationships and sense of belonging: qualities which are associated with resilience.

Music Programmes for Young Offenders