What is a Cover?

© 2022 P.D. Magnus, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0293.01

Consider this recent Twitter thread:

8:00 PM Jun 3, 2021

Panda Lakshmi: Once I was singing Istanbul (not Constantinople) in my house and my mom starting singing along. Turns out the TMBG version is a cover!

Ellen Fuoto: So my 70 something year old brain is starting to wake up. You mean They Might Be Giants made a cover of the Four Lads hit from back when I was 6?

Uglysquirl: You two have blown my mind.. I’m a big fan of cover songs and TMBG and I never knew this was a cover.

gargoyle: I... With the.. But... I was today years old when I learned this. I’m going to need some alone time to deal with this crisis.

The song that they are talking about (‘Istanbul (Not Constantinople)’) was a hit in 1953 for the quartet the Four Lads, and it ‘found its way into our cultural lexicography as one of those songs that you knew you knew, but didn’t know where you knew it from’ (Treble 2018). The duo They Might Be Giants (TMBG) recorded a faster, livelier version for their breakthrough 1990 album Flood. The younger participants in this thread are surprised to learn this, because they just know it as a TMBG song. At the same time, the one older participant is surprised to learn about the TMBG version. Minds are blown. Even though the winking emoji in the last post makes clear that nobody’s life is deeply changed by this discovery, all the participants find it significant that the TMBG version is a cover.

Music audiences, which include you and me, use the concept of cover to understand certain songs, performances, and recordings. We take the difference between original and cover to be significant. But what is the difference? What does ‘cover’ mean?

The dictionary definition

A ‘cover’ is typically defined as a recording of a song that was first recorded by someone else. Something like this is given in many dictionaries and by some scholars. For example: Albin Zak provides a glossary entry defining a ‘cover version’ as ‘A recording of a song that has been recorded previously by another artist’ (2001: 222). Don Cusic writes, ‘The definition of a “cover” song is one that has been recorded before’ (2005: 174).

If it were that simple, this could be a short book. Inevitably, complications arise. Let’s look at five of them.

Five problems

1.

Consider the song ‘Let It Be’, written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Their band, the Beatles, had a hit with it when they released their version in 1970. However, the first released recording of the song— by a few months— was by Aretha Franklin. A website which generates its descriptions automatically labels the Beatles’ version as a cover of Franklin’s, and that is just what the usual definition would suggest. However, this seems absurd. If either version is a cover, then it is Franklin’s. Lennon and McCartney were members of the Beatles who wrote the song with the intention of recording it, even though McCartney sent a demo to Franklin in hopes that she might record a version. It just happened that her version was released earlier.

One might think that the prior existence of the demo makes Franklin’s version a cover, but many recordings— most in recent decades— exist as demos before there is a published version. To take just one example, consider Patsy Cline’s 1961 hit ‘Crazy.’ The song was written by Willie Nelson, who was trying to get a singer to record and release it. He cut a demo record of ‘Crazy’ and played it in a bar in Nashville for Patsy Cline’s husband, who insisted he play it for Cline. She loved it and recorded her version the next week. Although Nelson had recorded a demo, almost nobody calls Cline’s version a cover. It does not show up on internet lists of best cover songs or songs you didn’t know were covers. Artists on YouTube typically list their versions of ‘Crazy’ as covers of Patsy Cline. So the existence of a demo does not seem to make Cline’s version a cover.

However, consider ‘Girls Just Want to Have Fun’, a hit for Cyndi Lauper in 1983. It was written by Robert Hazard, and he recorded a demo version in 1979. Surprisingly, Lauper’s version appears on many of those internet lists. This may partly be confusion because Hazard’s demo was later published (to piggyback on the success of Lauper’s version) but often these lists acknowledge that Hazard’s version was a demo. One comments, ‘Hazard’s recording never got past the demo stage, so I’ll choose to consider Lauper’s version “technically a cover but sort of not really”’ (Proximo 2017). When Lauper’s album was selected for the National Recording Registry, a webpage at the Library of Congress included the comment, ‘Lauper’s take on Robert Hazard’s “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” wasn’t a mere cover, it was a transformation of the song into a joyous feminist anthem’ (NRPB 2018). Something which is not a mere cover is more than a cover, rather than not being a cover at all.

Another example is the Crickets’ 1957 hit ‘Oh Boy’, which is often described as a cover of Sonny West’s version (Londergan 2018). West, who cowrote the song, had recorded a demo of it under the title ‘All of My Love.’

Contrary to the simple definition, the existence of a demo version does not automatically make a version a cover— but maybe it does sometimes. Call this the problem of demo versions.

2.

If we accept Cline’s version of ‘Crazy’ as the original, then later recordings should count as covers. However, when Willie Nelson recorded it for his debut album the following year, it was not obviously a cover. Here common usage is unclear. Some people count Nelson’s version as a cover (due to Cline’s original) but others do not (due to Nelson having written the song). It is a vexed question.

It is also unclear how to think of cowritten songs. Consider two cases: First, the song ‘China Girl’ was cowritten by Iggy Pop and David Bowie, and Bowie played on and produced Pop’s 1977 recording. Bowie recorded his own version in 1983 without Pop. Second, the song ‘Layla’ was cowritten by Eric Clapton and Jim Gordon. They recorded it with their band (Derek and the Dominos) in 1971. For MTV Unplugged in 1992, Clapton recorded an acoustic version which won the Grammy Award for Best Rock Song. The usual definition would call Bowie’s ‘China Girl’ and Clapton’s ‘Layla’ covers, and some people would agree (Leszczak 2014, Popdose 2011). Bob Leszczak, for example, describes the MTV Unplugged performance as Clapton having ‘covered his own song’ (2014: 120). Other people are inclined to say that these are not covers.

So there are vexing questions about whether and how a person who wrote or cowrote a song can cover earlier recordings of it. Call this the problem of songwriters.

3.

The typical definition only applies to new recordings. Yet a cover band is a musical group that just performs covers, and most cover bands perform live rather than recording. This shows that the word ‘cover’ is readily applied to live versions as well. There is an asymmetry, however, because something is not a cover if it is a recorded version of a song that has previously been performed live. Even though a cover may be a live version, the earlier original must be a recording. Call this the problem of live versions.

4.

A cover of a song need not include any singing, and instrumental versions are regularly labelled as instrumental covers. Nevertheless, one would not call Miles Davis and Cannonball Adderly’s 1958 version of ‘Autumn Leaves’ a cover. There were earlier released recordings by Yves Montand in 1946 (as ‘Les feuilles mortes’), by Dizzy Gillespie and Johnny Richards in 1950 (as the instrumental ‘Lullaby of the Leaves’), and by others. The tune had become a jazz standard. When it is played today, one might compare the new performance to the famous Davis/Adderly version, but one would not call the new performance a cover.

‘Autumn Leaves’ is not extraordinary in this regard. We treat jazz recordings differently than we treat rock recordings. This has prompted writers like Deena Weinstein (1998) and Gabriel Solis (2010) to argue that covers only exist in rock music. Weinstein writes, ‘Cover songs, in the fullest sense of the term, are peculiar to rock music, both for technological and ideological reasons’ (1998: 138). However, this requires an expansive conception of what counts as rock. There are covers in pop music and contemporary country as well. Moreover, there are numerous points of interaction between jazz and rock (especially rock in this expansive sense). It is unclear how to draw the boundaries around the regions of musical or cultural space where covers are possible. Call this the problem of genre.

5.

Contrast two cases: First, Kid Cudi’s 2008 ‘50 Ways to Make a Record’ follows the same melody and musical structure as Paul Simon’s 1975 ‘50 Ways to Leave Your Lover’ but replaces Simon’s lyrics about love lost with ones about making music. Cudi’s track is often described as a cover of Simon’s. Second, Weird Al Yankovic’s 1981 ‘Another One Rides the Bus’ follows the melody and musical structure of Queen’s ‘Another One Bites the Dust’ but replaces lyrics about being indomitable with ones about public transit. ‘Another One Rides the Bus’ is usually described as a parody of ‘Another One Bites the Dust’ and is not counted as a cover.

The percentage of words shared between the original and the parody does not seem to matter. There is parallel structure in the title and lyrics between Cudi and Simon but also between Yankovic and Queen. Perhaps the only thing which stops ‘Another One Rides the Bus’ from being a cover is that it is a parody, which in turn is because it is funny. And ‘50 Ways to Make a Record’ counts as a cover because it is not a parody, which in turn is because it is not funny. John P. Thomerson, who denies that parodies have to be humorous, seems to count all covers as parodies; he refers to typical cover band performances as ‘reverential parodies of classic rock and country hits’ (2017: 1). A definition of ‘cover’ should be able to make sense of this. Call this the problem of parodies.

Looking for the real definition

These problems are reasons to be unhappy with the usual definition, and we can use them as a toolbox to dismantle other definitions. For example, Andrew Kania defines a cover in this way: ‘A cover version is a track (successfully) intended to manifest the same song as some other track’ (2006: 412). This is vulnerable to all of the problems discussed above.

One might start tinkering with these definitions, adding clauses to resolve each of the problems. Yet that is not the only possible response.

An alternative approach supposes that the meaning of the term is determined by how it was introduced. The word ‘cover’ refers to a particular type of thing. So it has a real definition, the true nature of those things, regardless of what ordinary people or scholars might say when asked to define the term.

This approach was originally applied to proper names and to natural kind terms like ‘gold.’ The idea is that the word ‘gold’ was introduced to describe samples of gold, and it meant that kind of stuff. For centuries, people did not know what gold really was. They could not have given a true and informative definition. Only later did chemists develop atomic theory and physicists learn the structure of atoms, allowing us to characterize gold as a chemical element in terms of the number of protons in each of its atoms. Nevertheless, that is what ‘gold’ meant all along (on this account). (My gloss of the view here is rather breezy. Key texts are by Saul Kripke (1972) and Hilary Putnam (1975), and decades of literature have followed.)

Although the category of cover versions does not look like a natural kind, it has also been suggested that this approach to meaning applies to artifacts (Putman 1982). So maybe ‘cover song’ picks out that kind of recording or that kind of version. Unlike ‘gold’, which entered Old English from even older sources, the word ‘cover’ in the sense that interests us arose only in the late 1940s. So let’s turn away from puzzle cases and consider some history.

The history of covers

The term ‘cover’ first found widespread usage in the 1950s, corresponding to a shift in the record business.

Here is the simplified version: Before the 1950s, songs which everyone played became standards. This is natural when the paradigm case of music was live performance, both because performance is ephemeral and because it is done by whatever musicians someone has in front of them just at that time. Radio, initially dominated by live performance, did not immediately change this paradigm. After the 1950s, new versions of songs are often considered in relation to earlier recordings of that same song which are taken as canonical or original. The new versions are covers.

Early days

Initially, customers tended to seek out a particular song rather than a particular recording of that song by a particular artist. By covering a song, a record company could steal sales which would have gone to a competitor. As John Covach and Andrew Flory write, ‘When the original version appeared on a small independent label, a larger independent label (or a major label) could record a cover and distribute its records faster and more widely….’ They add that ‘to some extent, this explains the greater success of these versions and why we call them “covers”’ (2018: 87). Ray Padgett writes that covers in the 1950s were ‘copycat recordings done quickly’ and suggests two reasons these might have come to be called ‘covers’: First, a publisher might be ‘“covering its bets’’ by releasing its own recording of a popular song.’ Second, it was aimed to ‘“cover up’’ another version of the same song on a store’s shelves’ (2017: 4).

That is only part of the story. In a 1949 Billboard magazine article on small record labels, Bill Simon writes:

The original disking of Why Don’t You Haul Off and Love Me?, cut for King [a small record label] by Wayne Raney, has hit 250,000, and versions are now available on all major labels. None of these, however, has approached Raney’s mark. Another King disk, Blues Stay ’Way From Me?, by the Delmore Brothers, is close to 125,000 in six weeks, and other companies have just begun to cover the tune. (1949: 18)

Here ‘cover’ has the sense of coverage. Just as a band might try to learn the popular songs that an audience member might request, a record company wanted to be able to have a version for sale. This reflects how songs work. A song can be performed by different artists. It is not matched one-to-one to the person who wrote it or the singer who made it famous.

From a commercial standpoint, there is no reason to make something original. It is easiest just to copy the interpretation and arrangement of a hit record, and the success of the hit suggests that it might be more commercially successful than trying something new. So there was a shift from making sure a label’s library covered the repertoire to cutting records that just copied successful ones. In 1954, the chain store Woolworth’s launched its own record label in the UK, Embassy Records. Their entire line was cheaply recorded knock-offs (Inglis 2005, Woolworths 2017).

(Image courtesy of the Woolworths Museum.)

Some in the industry commented on the contrast between earlier covers (new versions of a song recorded for coverage) and these new copy recordings. A 1955 Billboard article laments ‘the duplication (rather than the covering) of successful disks’ (1955a). An article a few months later describes a New York radio station that ‘will henceforth refuse to play “copy” records.’ The article explains that this policy ‘draws a clear distinction between “cover” records and “copy” records— defining the latter as those disks which copy— note for note— the arrangement and stylistic phrasing of the singer’ (1955b). Nevertheless, the word ‘cover’ came to apply to both sorts of records— both recordings of the same song that used a different interpretation or arrangement and also those that copied the interpretation and arrangement of the original recording.

A further feature of music in this period was the centrality of rankings in trade magazines as a measure of commercial success. At least in the United States, this introduced complexities of race and class. The Billboard magazine rhythm and blues (R&B) chart had, prior to 1949, gone under a succession of other titles: ‘Harlem hit parade’, ‘race’, and ‘sepia.’ As the earlier names make clear, the chart was not meant to capture a particular style of music but instead a particular audience demographic— black people. The country and western chart, previously ‘hillbilly’ and ‘folk’, was also organized around a particular audience. As Covach and Flory note, ‘Rhythm and blues… charts followed music that was directed to black urban audiences, and country and western… charts kept track of music directed at low-income whites’ (2018: 85). This left the pop charts, although nominally just tracking popular music, focused predominantly on the white, middle-class market.

Covach and Flory put the point in terms of the music’s target audience, but a song could have success beyond just its target. The charts were constructed based on reports from radio stations and juke boxes (of what they were playing) and from record shops (of what they were selling). As a result, a song by a black artist could make it onto the pop charts if it had plays and sales in places to put it there. Similarly for country musicians. A song that made it onto multiple charts was called a crossover, and crossing over meant a distinct kind of commercial success.

Although some crossover hits were a single record appearing on multiple charts, others were the same song but recorded by different artists. Given the racial division of the charts, there are striking examples of white artists having pop hits with songs that had been R&B hits when recorded by black artists. The most famous example of this is probably Pat Boone’s 1956 pop version of Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti.’ In that case, the cover by the white artist did not completely eclipse the original. Although Boone’s cover reached #12 on the Billboard pop chart, Little Richard’s reached #17 on the pop chart and #2 on the R&B chart. Regardless, this is just one instance of a broader pattern in which, as Denise Oliver Velez puts it, ‘Black music… was “borrowed,” “lifted,” “copied,” and made money for white artists, often garnering both commercial success and awards… while leaving the Black originators with far less, or nothing’ (2021). Singer-songwriter Don McLean describes it this way:

[I]f a black act had a hot record the white kids would find out and want to hear it on ‘their’ radio station. This would prompt the record company to bring a white act into the recording studio and cut an exact, but white, version of the song to give to the white radio stations to play and thus keep the black act where it belonged, on black radio. A ‘cover’ version of a song is a racist tool. (2004)

The word ‘cover’ suggests itself here perhaps as a contraction of ‘crossover.’ McLean leverages this as a definition, to argue that Madonna’s 1999 version of his 1971 song ‘American Pie’ should not be called a cover. Yet, common usage treats Madonna’s version as a cover. Although covers were sometimes used as racist tools, racism is not intrinsic to the concept of a cover as such. As Michael Coyle puts it, crossover covering of R&B hits by white artists ‘exploited racist inequality but did not arise because of it’ (2002: 144).

The word cover originally had a sense of coverage which was not in itself tied to race, and covers in that sense continued. Even when a cover eclipsed the original, it was not always about race. For example Sonny West cowrote and recorded ‘All My Love (Oh, Boy)’ (1957) and ‘Rave On’ (1958), but both were covered by Buddy Holly and the Crickets. Borrowed, lifted, and copied, but by white musicians from a white musician.

In the earlier, song-focussed market, songwriters and publishers would make money from sheet music as well as recordings. In the 1950s, the situation was changing. The only way for a country and western song to sell successfully as sheet music was if it crossed over to the pop charts (Gabler 1955). And soon enough sheet music would not be a central concern at all, as the primary product became the recording itself. Because of the changing marketplace, covers were a way for a song to get exposure to a broader audience. This was good for songwriters (who got a royalty from every sale, regardless of whose version was selling) but bad for performers (who profited only from sales of their records).

Coyle argues that this history fails to capture what covers really are. He writes ‘that no one in 1954 would have used the word “cover” to mean what we mean by it today.’ The sense of the word ‘cover’ that I’ve discussed so far in this section is what Coyle prefers to call hijacking a hit or just hijacking. Although hijacking was called covering in the 1950s, Coyle maintains that the word means something different now. He writes, ‘The notion of covering a song has changed radically in meaning because… the relation of writers to performers to audiences… has changed radically’ (2002: 136).

Coyle maintains that the contemporary sense of ‘cover’ began in the late 1950s and that, ‘in our modern sense of the term, Elvis Presley was the first cover artist’ (2002: 153). Elvis neither wrote his own songs nor recorded ones that were current hits. Instead, he recorded songs that had faded from memory. Coyle writes, ‘In recovering nearly forgotten recordings by black artists Presley was doing much more than reviving potentially money-making properties; he was using recordings by black artists to perform for himself and for America a new identity’ (2002: 153). Writing about subsequent developments in the late 1960s, Coyle writes that ‘while the black audiences for 50s-style R&B had long since moved on to other styles, there was an audience of “serious” white fans’ eager to embrace a blues revival (2002: 152). Elvis also recorded covers of country songs, but the R&B songs did more to define his image.

The covers that Coyle highlights exploited race in a different way than McLean describes. Whereas Pat Boone recorded songs written by black musicians without any suggestion of their origins, Elvis and later artists positioned themselves explicitly as white musicians performing black music. So, Coyle claims, covers were ‘a way for performers to signify difference’ and to ‘project their identity’ (2002: 134). This identity was bound up with issues of race, because ‘white groups were striving to sound black’ by harking ‘back to material that black audiences had already largely abandoned’ (2002: 143).

So Coyle advances two theses. The first is that the early-50s sense of ‘cover’ went away. The second is that it was replaced by ‘cover’ in the sense of a recording that establishes the recording artist’s identity by signifying the original version in a way that exploits the dynamics of race. Although he is pointing to important historical developments, neither thesis is true. I will explain why in the next two sections.

Hijacking continues

Coyle is right that there were changes in the music industry in the late 1950s which made covering (in the sense of what he calls hijacking) less prevalent. However, it did not go away. The Scottish jazz musician Sandy Brown still defined ‘cover’ in those terms in 1968; he writes, ‘The jackal thinking behind cover versions, which are near copies of original recordings, is predicated on the belief that so much money is showered in the general direction of hit records that any performance of the song will collect if sufficiently adjacent’ (1968: 622). Adapting Brown’s language, we might call these jackal covers. They continue to be at least part of what contemporary audiences think of as covering.

If we look at the music industry press, there have been declarations that covering in that sense was on the way out for almost as long as there have been covers. Considering the success of Decca records, Milt Gabler writes in 1955, ‘The day of the fast, haphazard “cover” record is gone. This does nothing but lose money for the company, the artist and the publisher. Today more money is put into advertising and exploitation than at any other period in the history of the business. Records must be good to pay off.’ He adds, ‘The best chance a new artist has is with new material or an outstanding arrangement of a great standard!’ (1955) An article in Cashbox magazine a couple of years later discusses changes underway in the music business: ‘Record fans in the current market know the records of all the fields and very often even if there are cover records, they want the original one’ (1957). In 1970, the head of a record label is reported in Billboard to have said that covering was ‘a costly affair’ because ‘a company that comes out with a “cover record” has to put an extra effort to beat the original and this means a heftier outlay in promotion and advertising expenditure’ (1970).

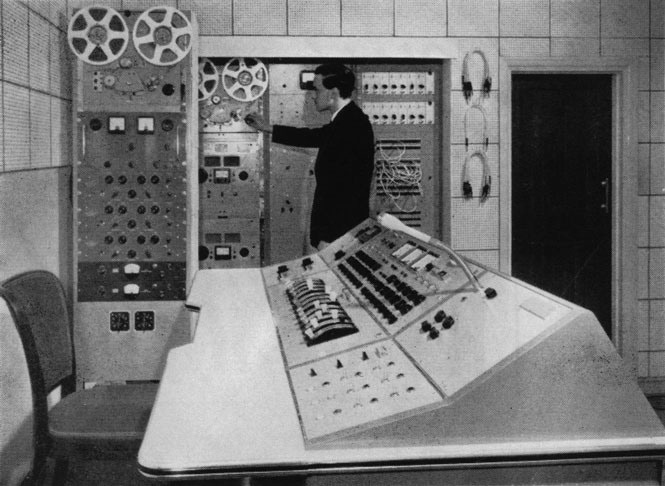

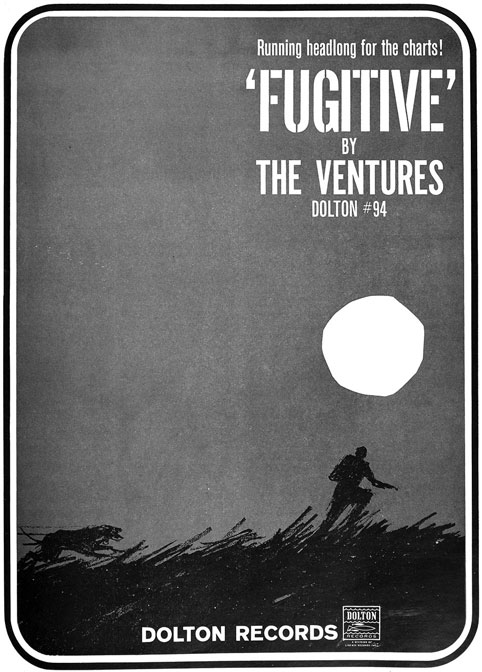

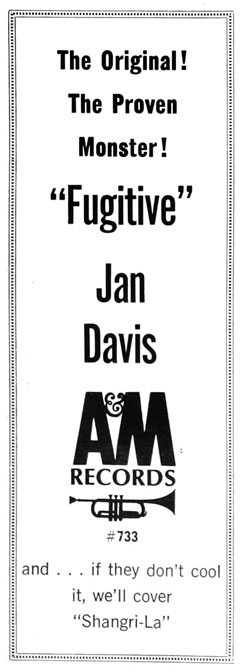

Take one vivid example: A&M records released ‘Fugitive’, a guitar instrumental by Jan Davis. Dolton records released a cover by the Ventures, taking out a full-page ad in the April 11, 1964 issue of Cashbox magazine which announced that the Dolton disk was ‘Running headlong for the charts!’ Since neither version of ‘Fugitive’ made it into the Billboard Hot 100, maybe it just shows that you cannot hijack a hit if your target does not end up being a hit— but there is more. A&M had a sidebar ad in the same issue, declaring Davis’ version to be ‘The Original! The Proven Monster!’ and adding, as a threat addressed to Dolton, ‘if they don’t cool it, we’ll cover “Shangri-La”.’ (See Figure 1.3.) ‘Shangri-La’ was another of Dolton’s records which was climbing up the charts. Curiously, Dolton’s version of ‘Shangri-La’ (recorded by Vic Dana) was itself a cover (of a version by Robert Maxwell). Given that the two ads appeared in the same issue, it is possible that the A&M/Dolton conflict was a bit of theater. Yet even as contrived drama it only makes sense with the presupposition that ‘Fugitive’ was a hit and that Dolton’s ‘Shangri-La’ was the genuine article. The ads invite the reader to presuppose those things, against a background understanding that struggling to overtake a hit record with a cover is a losing proposition.

The shift away from jackal covers occurred somewhat later in foreign markets. Paolo Prato discusses songs from the 1960s that he knew growing up in Italy. Although they were English or American pop hits, he thought of them as Italian songs because he only knew them from translated cover versions. Prato writes, ‘Cover bands had an easy job in the 1960s, when many English and American records arrived in Italy: it was enough just to pick up a hit record and translate it to be successful’ (2007: 458). He describes a drastic shift in the 1970s, though, both because more Italian musicians began to record original rock/pop songs and because Italian audiences began to expect English-language hits in their original versions. As a sign of similar shifts elsewhere: A Spanish producer in 1968 comments, ‘Three years ago it was possible to get a Spanish group to cover a Beatles record and score a hit. But not any more. Spanish record buyers are demanding original versions and the language barrier has gone for good’ (Billboard 1968).

Despite the trend away from it, however, jackal thinking did not end entirely. The music press notices periodically that there are covers that sell well. In 1965, Tom Noonan writes that ‘cover disks are making it— that is, sharing the loot along with the big version.’ Claiming that this is an exception, Noonan adds, ‘In an earlier era, one version would generally step up and the others would drop out of the race’ (1965: 1).

As albums became more widely available (rather than disks just being singles) new space for covers was created. When a song on an album was not released as a single, another artist might record a cover just to have it released as a single. Consider two examples. First, in 1961, ‘His Latest Flame’ was one of the tracks on an album by Del Shannon. Elvis Presley cut a version of the song just weeks later, and it was released as a single under the title ‘(Marie’s the Name), His Latest Flame.’ Elvis’ single reached #4 on the Billboard Hot 100. Second, in 1968, ‘Back in the U.S.S.R.’ was one of the tracks on the Beatles’ White Album. There were several cover versions, including a single by Chubby Checker just a few months after the album was released. Checker’s single reached #82 on the Hot 100.

Even when many buyers started to demand original hits by original artists, some were still less discerning. Even though Woolworth’s Embassy Records ended, low cost cover albums continued to be a thing. And the children’s market allowed another niche for covers. A 1973 Billboard article comments, ‘Unlike the pop field, where the buyer recognizes a cover immediately and, in fact, is usually looking for the original, the children’s field is rife with cover records.’ The article goes on to quote one record exec, who comments that cover records for children are ‘good sellers’ (1973a).

More recently, the shift to streaming music services has given a new place for jackal covers. Users search for a popular song but, depending on the exact search terms they use and where they click, may end up listening to a cover. Lizzie Plaugic writes, ‘On platforms like Spotify, playing riffs on popular songs can lead to a far larger audience than recording original material — all you need is a song people are already searching for. … [W]ith a little creative track name optimization and a halfway decent recording, you could be looking at a potentially huge audience.’ She adds a cautionary word which echoes the sentiments expressed in 1950s Billboard articles, but updated for the new technology: ‘If streaming services are in fact the music-listening platforms of the future, expect a world with a few originals surrounded by dozens of copy and pastes’ (2015).

To sum up: Despite changes in the music industry, there have continued to be covers in the sense that goes back to the 1950s. Changes in the market have discouraged covers in a certain respect but also created new opportunities for covering.

Before moving on, it is worth noting that charts and coverage in industry magazines were tools for commercial purposes and not a direct window into musical tastes. Rather than neutrally reporting trends, they could also reinforce and shape them. Elijah Wald notes that, by the late 1950s, there was a tremendous overlap between the Billboard pop and R&B top fifty. He suggests that this was due only in part to a convergence of musical style and that it also resulted from white teens starting to patronize the radio stations and record shops that served as the reporting basis of the R&B charts (2009: 180–181). There were subsequently changes in how the lists were constructed.

Even though there are limitations to what can be gleaned from industry magazines like Billboard and Cashbox, they nevertheless provide insight into the attitude toward covers at the time. What someone then actually wrote or how high a recording made it on the charts provides a check on present-day myths about what happened or biases about which records are significant. They are evidence, albeit imperfect, that my historical claims are not a just-so story that I contrived to underwrite my philosophical account.

Covers that hark back

Recall that Coyle claims covers, in a later sense of the word, are ‘a way for performers to signify difference’ and to ‘project their identity.’ He is right that this can happen, and his examples of early Elvis and the early Beatles are apt. Nevertheless, he is wrong that this necessarily involves the politics of race, and he is wrong that this is all there is to a ‘cover record per se’ (2002: 134).

First, regarding race: Consider two examples.

At the height of his fame in 1973, David Bowie released an album of covers. Instead of drawing songs from early American R&B, the Pin Ups album includes covers of songs which Bowie described as ‘favorites from the 64–67 period of London’ (Lenig 2010: 128). Stuart Lenig suggests that the album served ‘as a crash course in British pop/mod culture of the last ten years’ shaped to fit Bowie’s vision (2010: 131). One might argue, because the rock bands of the 1960s that Bowie was covering were themselves influenced by black music and American R&B, that Pin Ups still figures in the complicated story of race and popular music in the 20th century. Those influences have nothing to do with Pin Ups as an album of covers, however. The identity which Bowie was forming and projecting was as a British rock star in relation to earlier British rock.

In the late 1980s, the punk band Social Distortion made a shift toward the subgenre of cowpunk— sort of the intersection of country music and punk. Their 1990 album included a cover of ‘Ring of Fire.’ It is typically understood as a cover of Johnny Cash, because Cash’s version of the song is the classic despite not being the first published recording. Social Distortion’s cover refigures it as a punk song, at once legitimizing the fusion of country and punk and projecting the group’s identity as a cowpunk band. Lead singer Mike Ness recounts, ‘This was during a period of time where there were a lot of those “what’s punk versus what’s not punk” discussions going on [but] I thought it was very punk rock to cover a Johnny Cash song’ (Hodge 2017).

In both of these examples, an artist or band records a cover so as to establish their identity by their revision of and relation to an earlier version. Covers functioning in that way need not involve a dynamic of race, as it did when Elvis, the Beatles, or the Rolling Stones covered early R&B. Although race can arise as an issue in covers, that is because racial issues run deep in American culture and in American music. The phenomenon of the cover song is not essentially connected to it.

Second, regarding covers as the projection of identity: Although the last two examples were further illustrations of how musicians can use covers to establish their identity, there are many other reasons why musicians decide to cover.

There are periodic waves of nostalgia in popular culture. Lenig describes one such wave: ‘Cover albums were rampant in the early seventies. During that time, Bryan Ferry, Bette Midler, Manhattan Transfer, the Band, Bob Dylan, Don McLean, were all engaged in cover projects. Television like Happy Days, plays like Grease, and films like American Graffiti celebrated a culture of past worship’ (2010: 130–131). There was not a dominant new style, so ‘cover albums were likely to at least rally some sales in a precarious and uncertain market’ (2010: 131). In such a period, an artist might cover a track from the 1950s in order to craft their identity in relation to musicians of the earlier period. Yet they might do so simply in order to sell records. The same jackal thinking that justifies recording a cover of a current hit can, in the context of nostalgic market forces, justify recording a cover of a song from decades ago.

Yet, sometimes, there is no special reason for the timing of a cover. There just happens to be an earlier song which a new musician would like to play. Take ‘Istanbul (Not Constantinople)’, the example that started this chapter. It had the lyrical structure of a They Might Be Giants song already. Their songs have small stories and not-quite-serious drama, which they fold into what Jon Cummings describes as ‘hyper-verbal alt-rock souffles’ (Popdose 2011). So when they covered it, they were only projecting the identity that they had cultivated in all of their original songs. They were not trying to steal it, but neither were they using their relation to the original version to establish their bona fides. Nor was there any special reason why a song from 1953 should enjoy a resurgence in 1990.

Coyle is right that, as time went on, there were many covers of songs that had been hits years before (if they had been hits at all) rather than just covers of current hits. However, I think the explanation for this is rather more banal and superficial than he suggests.

In the 1950s, the history of recorded music was all relatively recent. In a series of Billboard articles in 1961, June Bundy writes about the oldies trend (1961a,b,c). There are two striking features of this trend.

First, although it included programming focussed on the big band era of the 30s and 40s, there was also a significant focus on late 50s rock and roll. Describing the success of one radio station, Bundy writes that ‘the bulk of the programming is made up of hits from the ’50s, [especially] r.&r. hits of 1955, 1956, 1957, and early 1958’ (1961a: 1). From the standpoint of 1961, this reached back just a few years. As decades passed, that early rock and roll receded further. The oldies got older.

Second, as a result of the oldies trend some old songs had a resurgence of popularity. Bundy describes ‘old hits’ which had recently made it into the Billboard Hot 100. Old hits were competing with new productions; she explains, ‘The new nostalgia trend isn’t entirely to the liking of the recording industry, which is anxious to expose new wax product as well as old’ (1961a: 47). In listing old songs making a resurgence, however, Bundy does not distinguish original recordings by the original artists from recent covers. Covers could be hits with songs that had been hit records before, and this means that it could make commercial sense to release covers of oldies. As the history of rock and roll grew from a few years to several decades, there were simply more earlier records to cover.

Because rock and roll began in the 1950s, it would have been impossible for a band in the 50s to cover a rock and roll song from an earlier decade. It was possible for bands in 1961 just because it was a new decade. Recorded music matured as a medium— it had been around for longer— so a musician who wanted to record an existing song was more likely to think of one that had already been recorded. Moreover, they were more likely to think of the original or classic recording of it as the source for the song. So it was more likely that their recording would end up being a cover.

This also explains why, over time, jackal covers make up a smaller proportion of all covers. Covering only threatens to hijack a hit when it is done just as the original is starting to climb the charts. A record is only a hit for a brief window of time, and a cover done later looks like returning to an old favorite rather than trying to steal sales from a hit. Dionne Warwick complains about other musicians recording covers that competed with her releases. Nevertheless, she admits, ‘It’s true that I’ve cut a lot of songs which other people did first but I always waited until the originals had had their chance. I had a hit with “I’ll Never Fall In Love Again”, but I had refused to record it until Ella Fitzgerald’s original had died’ (St. Pierre 1975).

The lessons of history

Where has this discussion of the history of the word ‘cover’ led us? The term first applied to new versions of songs which had already been recorded, where the original was already a hit or was expected to become a hit. It was extended to new versions of songs recorded longer ago. The motivation for publishing covers was often to capture sales which could otherwise have gone to the original. So when the original recording was by a black artist and the cover was by a white artist, covers could be a tool of exploitation and oppression. Yet covers were also sometimes recorded just because a current artist had fond regard for a classic recording.

This does help resolve some of the problems raised at the outset of the chapter. Let’s take the problems of demo versions, songwriters, live versions, genre, and parodies in order.

1.

Because cover songs began as a phenomenon of music publishing, for something to be a cover in the original sense there had to be an earlier published recording. Unpublished demo versions do not count. Robert Hazard’s demo of ‘Girls Just Want to Have Fun’ is a peculiar case because it was published a few years later. Sonny West only recorded a demo of ‘All My Love (Oh, Boy)’, but his version of ‘Rave On’ was released as a single. Buddy Holly and the Crickets had hits with both, and they are usually mentioned together. If Hazard’s demo had never been published and if it hadn’t been for ‘Rave On’, then there might be no temptation to call Lauper’s ‘Girls Just Want to Have Fun’ or the Crickets’ ‘Oh Boy’ covers.

2.

When a songwriter records their own song after someone else, it meets the simple definition of a cover. Yet they are not obviously driven by the jackal motive of stealing profits from the earlier recording, because the songwriter stands to gain royalties from the sale of either version. And they are not obviously establishing their identity by association with the song and the earlier recording, because as the songwriter they already were associated with it. As a result, the issue is vexed. It is tempting both to call it a cover and to not do so.

3.

Although live versions can count as covers of earlier recordings, recordings cannot count as covers of earlier live versions. The former point is a natural extension of the concept. Cover bands play covers, even if they only ever perform live. The latter point, the requirement of an earlier recording, captures precisely the shift in the 1950s. The introduction of the term ‘cover’ coincided with a shift from live performances to recordings being the central musical commodity. Covers were a new thing, but playing songs that had been performed live by someone else was the usual condition of music since forever.

4.

Differences between genres are explained by the fact that the history of cover versions primarily centers on pop and rock music. Recording has played and continues to play a different role in jazz. Whereas the recorded track is the primary way to encounter a rock song, jazz recordings serve more as documentation of the original performance. When there are pop versions of jazz tunes or jazz versions of rock songs, it is unclear whether we should call them covers or not.

Genre difference also explains why recordings of classical music are not referred to as covers. Although aficionados might want recordings of specific performances, many buyers will take any recordings of a composition. Although I own a CD of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, for example, I honestly have no idea which orchestra is recorded on it.

5.

In marketing terms, covers were distinguished from novelty records. This commercial difference may partly explain why parodies do not count as covers.

Admittedly, these considerations do not fully solve the problems. They neither provide a natural definition nor point to an essence. They do not reveal, out in the world, a kind to which the word ‘cover’ referred all along regardless of whether anyone could articulate its real definition. Both the word ‘cover’ and the practice of making covers serve a diverse range of purposes. Looking to history does not yield a forensic test which we can apply to determine whether, for example, Aretha Franklin’s ‘Let It Be’ is a cover or not.

Covers and remakes

A number of scholars have used the broader notion of a remake to understand covers. In the next two sections, I consider two such approaches. The first aims to find a definition by way of an analogy with film remakes. The second distinguishes covers as a special kind of music remake, arguing for a narrower definition of ‘cover’ itself.

Covers and film remakes

Andrew Kania takes film remakes as an important clue to his understanding of covers (2006: 408–409, 2020: 237). Michael Rings takes this a step further, incorporating the analogy into a definition. He writes that a cover is ‘a rock recording that captures a performance of a song that has already been recorded… by another artist and, as such, functions as a remake of the original recording, in a manner somewhat analogous to how remakes of films function in cinema’ (2013: 56).

The greatest problem with such an approach is that it just replaces one puzzle with another. I do not know what to say about film remakes. It would take a great deal of time and thought for me to figure out what I ought to say, even tentatively. Moreover, this would be time poorly spent because film remakes are at best a loose analogy for cover songs.

Tony Kirschner points out several disanalogies. First, people encounter music in a greater variety of ways than they encounter films. He lists, ‘live performance, recorded commodity, radio broadcast, music video, commercial jingle, movie and television soundtrack, and background music in public places’ (1998: 249). Although a clip from a film can be used as part of a commercial or as a reaction to an internet post, music still shows up in a wider array of contexts.

Second, ‘the lion’s share of rock music production occurs at the amateur level’ (1998: 249). Although computers and the internet have made video production easier, there is still a larger gap between what amateur video and what professional film look like than between how amateur rock and professional rock sound.

Third, music is more portable and travels more easily. Rock and pop music has influence around the world on local music scenes. Its influence is amplified by the fact that it shows up in more ways and impacts amateur practice.

I would add: Fourth, a song is simply much shorter than a movie. Listening to an original and a cover takes a few minutes, but watching an original film and a remake would take a whole evening. This difference changes how we can interact with them in fundamental ways, and is part of the reason that music appears in more contexts.

Fifth, movie remakes require large crews, from actors and directors down to gaffers and grips. Studio recording of a cover requires fewer people. Since a movie requires sound production and typically includes music, making it involves all the tasks involved in recording music plus all the visual tasks. In the limit, a cover requires just the musician. Although a film remake could in principle be made by just one person, that would be extraordinary. It is a common case for covers, though. It is not unusual for a cover played live or for an amateur YouTube video to not require anyone else. This explains why there is more amateur music production, and it greatly impacts the range of possibilities for cover versions.

Although Rings only relies on film remakes and covers being ‘somewhat analogous’, the connection is too weak to be helpful.

Covers and mere remakes

Theodore Gracyk argues that ‘cover’ has taken on a different meaning than it had in the early 1950s. Gracyk writes,

Since the 1960s, the concept of the cover… normally refers to a communicative act of “covering.” The cover record or performance is a version of an existing musical work. However, it is more than a version. It is a version that refers back to a particular performer’s arrangement and interpretation of a particular song. (2012/3: 23–24)

He calls covers in the older sense mere remakes. He spells out the distinction in terms of whether the audience knows about— and is intended to consider— the earlier version. For a version to be a cover on Gracyk’s account, ‘A musician must intend to communicate with a particular audience — many of whom can be expected to recognize its status as a remake — and must intend to have the remake interpreted as referencing and replying to the earlier interpretation’ (2012/3: 25). A version is a mere remake when the audience need not know about the earlier recording and is not intended to have it in mind. He writes, ‘In contrast to a cover, a mere remake is a new recording of a song that is already known by means of one or more recordings, but where there is either no expectation of, or indifference about, the intended audience’s knowledge of the earlier recording’ (2012/3: 25).

His distinction is similar to Coyle’s distinction between hijacking and recording a ‘cover record per se’ (2002: 134, discussed above). Gracyk, however, is not concerned with the projection of identity or entanglements with race. Instead, he thinks of a cover as involving reference to the earlier recording. The audience is invited to, even expected to, think of the new version in relation to the old one.

Many of the counterexamples to Coyle’s thesis could be given again here as counterexamples to Gracyk’s definition. He anticipates such a move, however. Precisely because the meaning of the term has shifted, the past will be rife with apparent counterexamples to his claim about the current meaning. Gracyk writes, ‘The analysis offered here does not pretend to capture all uses of “cover” in recent popular music. Concepts evolve, and therefore the early uses of a term are not an infallible guide to its present meaning’ (2012/3: 25).

There are limits to this maneuver, however. On Gracyk’s account, the 1987 version of ‘I Think We’re Alone Now’ by Tiffany is merely a remake of Tommy James and the Shondells’ 1967 hit. It is not a cover, he says, because there was no expectation that Tiffany’s adolescent fans would recognize it as a remake (2012/3: 25). Nevertheless, a news report in 2019 says, ‘Tiffany Darwish, known as Tiffany, is today possibly best known for her Billboard No. 1 cover version of the song “I Think We’re Alone Now”’ (DiGangi 2019). And Tommy James himself sees it as a cover, recounting in an interview that ‘Tiffany came up to me at a convention to apologise for covering us. I said: “Are you nuts? I should be thanking you.” She did a great job…’ (Simpson 2019). These are recent choices of words, and cannot be dismissed as a relic of mid-20th-century usage. One could argue that James is wrong to describe Tiffany’s version as a cover, but saying that the usage is mistaken is different than saying it is only evidence of earlier meaning.

Consider also that Tiffany released a new version of the song in 2019. It would be awkward to say that it is a cover of her 1987 version, because Tiffany is the artist who recorded both. It might be another cover of the 1967 original. Some news coverage avoids calling it a cover, calling it a remake instead, although one report does describe it as ‘a more crunchy and rock-inspired cover’ (DiGangi 2019). Regardless, her new interpretation of the song is explicitly in relation to her earlier version. Many listeners will remember the song from the 1980s, she knows this, and she intends for them to think of it. Many of her old fans will both remember the earlier version and be able to share the new version with their teenage children. So Tiffany’s 2019 version counts as a cover of her 1987 version under Gracyk’s definition.

Gracyk’s definition gets it wrong in both cases. The 1987 version of the song counts as a cover by contemporary common usage, but it does not meet Gracyk’s definition. The 2019 version is not obviously a cover— at least not of the 1987 version— but it meets Gracyk’s definition.

What are we doing here?

Part of the difficulty in defining ‘cover’ is that it is unclear what kind of answer we want when we ask what a cover is.

First, we might be trying to give an analysis. In providing a conceptual analysis, a philosopher takes the concept to be pretty well settled. The philosopher’s task is just to make explicit what we already understand. Traditionally, this has meant to provide a precise definition— necessary and sufficient conditions. An alternative is to analyze the concept as a property cluster. Regardless, analysis starts from common usage and is taken to be successful if it accords as much as possible with common usage. Because of that, it becomes a relentless cycle of proposal and counterexample. For every proposed definition, the philosopher stumbles on something that counts as a cover that is left out of the definition or something that should not count but is left in. A revised definition which handles those cases is devised, but counterexamples to the new definition arise. The process repeats.

Second, we might be trying to provide an explication. Instead of trying to say what we already mean by a term, explication is aimed at figuring out what we ought to mean. The term ‘explication’ comes from Rudolf Carnap, but the approach has more recently been called conceptual engineering (Cappelen 2018). Instead of abiding with the messy, imprecise concept we already have, the conceptual engineer tinkers with it so as to produce one that is more fit to use. Explication is not vulnerable to counterexamples in the way that analysis is. What matters is not whether the engineered concept fits with common usage but whether it can fulfill the function of the original term. It is often the case that the more useful concept will require reclassifying some specific cases.

Explication is often a good strategy in scientific work. Carnap gives the example of fish (1962: 5–6). Before the 18th century, it was standard to count whales as fish. Carl Linnaeus’ taxonomic system counted whales not as fish but as mammals. Although this required revising common usage, it better tracked distinctions that biologists were concerned with making. Now modern evolutionary systematics has put pressure on the Linnaean concept of fish. (Another example, which Carnap develops in his own work, is probability.)

Explication need not always be scientific. However, it requires that the context determine what function the concept is supposed to fulfill (Nado 2021). The problem with the cover concept is that it has no clear function. It is possible to propose definitions which would be more precise and give definite answers, to say about any recording whether or not it is a cover, but our interests and practices provide too little constraint to make any such explication the right one.

An artificially precise definition risks stipulating answers to substantive questions. For example, we might start out with the question of whether covering is an essentially racist practice. If we accepted Don McLean’s definition of a cover as a racist tool, then we would say that it is racist— but this result would follow just from the definition itself.

One might argue that the function of the cover concept is to help understand musical practice, and surely that is right. However, which musical practice should it help us to understand? The answer cannot be covering, because the function is meant to help us say what counts as covering. If we were concerned primarily with how musicians can use old songs to convey messages to new audiences, then something like Coyle’s or Gracyk’s definition might work as an explication. Yet this would leave out other important functions of ‘cover’ talk. Recall the fans from the outset of the chapter surprised to discover that TMBG did not write ‘Istanbul (Not Constantinople).’ Recall Sandy Brown lamenting the ‘jackal thinking behind cover versions.’ I would like to offer an account that addresses their concerns, too.

Kurt Mosser argues that ‘“cover’’ is a systematically ambiguous term’ corresponding to a cluster concept (2008). I would push the matter even further. There is not a clear enough cover concept to make analysis worthwhile, and our talk of covers does not have a unified enough function to make explication worthwhile.

Of course, there are things we can say in general about covers. Covers, in the sense that I am concerned with, are musical performances or recordings that stand in relation to an earlier recording. This does impose some restrictions. Where there is no earlier recording, I will not count a version as a cover.

Moreover, the word ‘cover’ has extended metaphorical uses which I do not have in mind. Take two examples: First, Greg Metcalf discusses covers not just of songs but of artists, as when a performer adopts something like the persona of Bob Dylan without actually playing any of Dylan’s songs (2010: 183). Second, a character in the television show Lucifer offers praise for a copycat using the same M.O. as an earlier serial killer by saying, ‘This new guy is not the original, okay? But he is a damn sweet cover’ (2018). Without a definition of ‘cover’, I cannot say that these uses are somehow illegitimate. However, I can say that they do not describe the kind of covers that this book is about.

This yields a necessary condition— that to be a cover something needs to be a musical version which covers an earlier recording. One might think this puts us right back at the definition proffered at the beginning of the chapter, namely of a cover as a ‘recording of a song that has been recorded previously by another artist’ (Zak 2001: 222). I do not think so.

First, a necessary condition is not on its own a definition. There are, as we have seen, several ways in which a version can meet the condition but still not be a cover.

Second, and more contentiously, I am not sure that the cover and the earlier recording will always be the same song. Covers can be different than the original, and maybe they can be so different as to be a different song. The necessary condition allows for this possibility, whereas the usual definition does not. (This point is addressed further in Chapter 5.)

Regardless, the usual definition allows us to identify a typical case of a cover. There are lots of extraordinary cases of versions that meet the definition as written but are not covers and maybe some that are covers even though they fail to meet the definition. We could try different formulations in hopes of hitting on a definition of ‘cover’, either to capture the existing meaning (analysis) or to craft the term for some specific function (explication). My suggestion instead is that we should forge ahead. There are interesting things to be said about covers, there are important distinctions to be made, and we can do that without a precise definition.

Conclusion

Carnap reflects on his attempts to give an explication of philosophy: ‘Yet actually none of my explications seemed fully satisfactory to me even when I proposed them… Finally, I gave up the search.’ He advises that ‘it is unwise to attempt such an explication’ because it is better to work on philosophical problems than to refine a sense of ‘philosophy’ that precisely fits them (1963: 862).

I suggest that what holds for ‘philosophy’ also holds for ‘cover.’ Common usage identifies some recordings as covers, and I take that as given. A cover is pretty much whatever audiences and critics count as a cover, but that alone is of little consequence. Considering those so-called covers, there are philosophical questions that arise and useful distinctions to be made. I start that work in the next chapter.