21. Reading against the Grain of the Black Madonna: Black Motherhood, Race and Religion

© 2022 Yelaine Rodriguez, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0296.21

Introduction

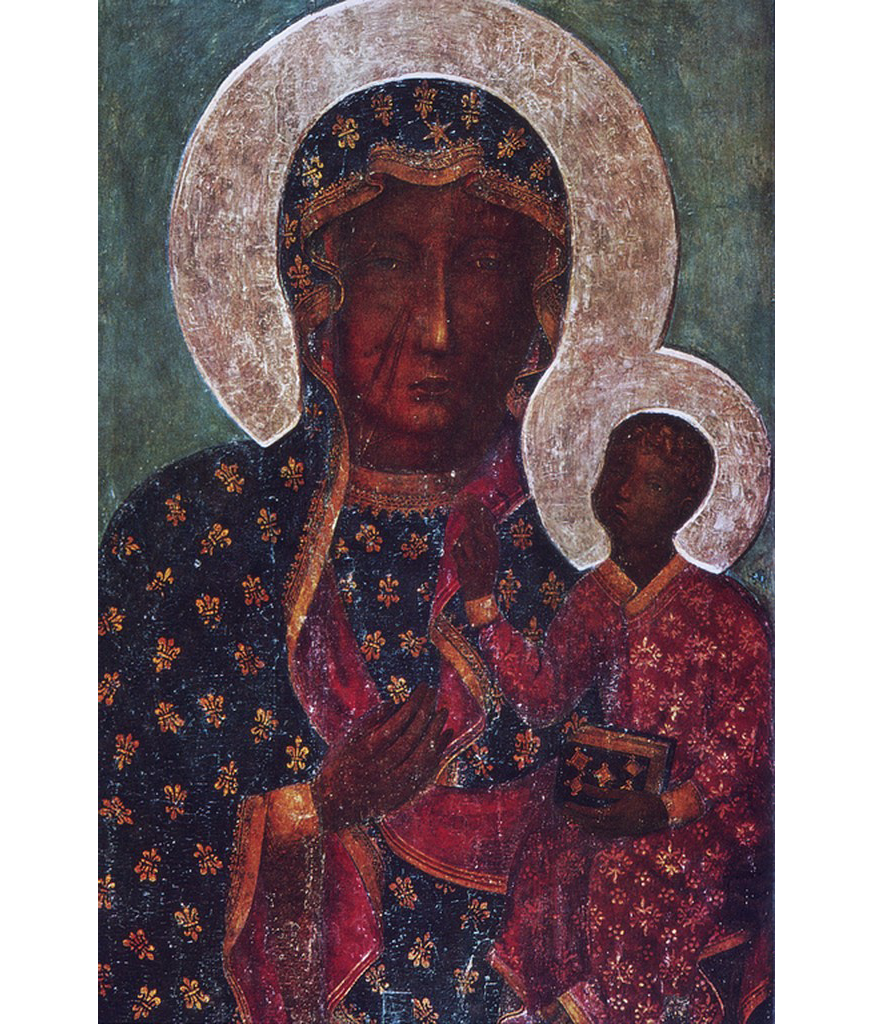

Could BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) productively produce without the confrontations or challenges of colonial legacies or archival silences? Moreover, how can they recover silenced voices and provide agency to marginalized ones? By employing the Black Madonna in Częstochowa, Figure 1, I demonstrate how BIPOC attempting to revive underrepresented voices build their arguments through the absence of resources, archival limitations, and bias constructs. I bring forth the Black Madonna as a case study since the narratives regarding her adaptation tell the untold stories of women’s lives. I argue that within the colonial archives, the erasure and ghosting processes of Black women further highlight this observation. When Black women do appear in colonial archives, usually, the pen of a man dictates their narratives. This detail matters because it illustrates why there is a lack of representation of Black women within the archives. It also matters because it serves as an example of some of the elements contributing to the erasure and ghosting of Black women.

Fig. 1 15th C. Black Madonna of Częstochowa restored in 1434, https://library-artstor-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000891521.

BIPOC must read through the biased sources in the archives while researching and constructing their arguments. They have to perfect reading “against their grain”1 to justify their research. The Black Madonna’s connections to various demographics and geographical locations and biased archival sources have rendered her origins a mystery. In this paper, I examine the migration patterns of the Black Madonna [in] Częstochowa, from Polish soldiers to Haitian insurgents during the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), and her appropriation into Haitian Vodou as loa (deity) Erzulie Dantor, ultimately attributing her for the success of the revolution. I examine how her Blackness was justified to allow the adoration of White patrons in Europe. Lastly, I display how contemporary Black artists reinterpret her to celebrate Black women and draw awareness and compassion for Black expressions and experiences. This research paper is composed of three main points. The first of these is an analysis of the appropriations of the Black Madonna and religious imagery within Black and White communities. Second, the connections between the Haitian Revolution, the Black Madonna, and Erzulie Dantor are considered, followed thirdly by a discussion of colonial legacies, archival silences, and BIPOC scholars and artists’ attempts to preserve and recover Black experiences and stories.

First, I like to acknowledge that I choose to write ‘Black Madonna in Częstochowa’ rather than the commonly used ‘Black Madonna of Częstochowa’, because [of] implies a singular ownership of the image by the people of Częstochowa. By replacing [of] with [in], I place emphasis on the migration patterns of this specific painting of the Virgin Mary from its discovery in the Holy Land (Jerusalem) in 326 by Saint Helena, mother to Constantine the Great, to Poland in the fourteenth century, and to the hands of the Haitian insurgents as inexpensive lithograph reproductions in nineteenth-century Saint-Domingue, modern-day Haiti. Additionally, by using ‘in’ rather than ‘of’, I seek to remove ownership of this image by an individual group. The recontextualization of the Black Madonna, throughout history and across numerous geographical locations, takes on new meaning. From the general public to distinctive cultures and BIPOC artists’ interpretations, the Black Madonna is reborn. Regardless of her place in history, her association with motherhood and as protector of children remains intact and undisputable. For example, both the Virgin Mary and Poland’s history with adversities made her a symbol of Poland’s soul and culture since her arrival, which also coincided with Poland’s nation-building project during the mid-1300s. Similarly, she appears in the nineteenth century, when Haiti is constructing its nation-state identity. Naturally, within the circumstances and timing, she becomes a mother figure to the formerly enslaved population of the first free Black republic.

Additionally, in this paper, I delve further into the origins of the Black Madonna and how her story has shifted depending on time, place, and culture. I discuss how believers of different races, traditions, and backgrounds justify their relationship with the image and how they negotiate with the resources that best promote their arguments. Furthermore, I study archival silence methods within colonial and Black archives, the preserved resources, and the written and dismissed narratives. I look into the archival hierarchy and how BIPOC find alternative strategies to extract and recover untold Black accounts. In conclusion, I recontextualize the main points by bringing forth three Black contemporary artists who use religious imagery, breathing new life, and drawing awareness to Black experiences. The works of Chris Ofili (born 1968), Renée Cox (born 1960), and Jon Henry (born 1982) together dismantle the biased constructs of what we know, based on archives as knowledge production. Their works speak to the contemporary relevance of the subject matter discussed in this text. Together, these bodies of work serve as visual representations of ‘going against the grain’, deconstructing our epistemologies of religion and race.

Part 1: The Appropriations of the Black Madonna and Religious Imagery within Black and White Communities.

How does an image like the Black Madonna in Częstochowa take on multiple patrons from distinctive paths of life, race, and cultures? If we are “made in the image of God,”2 should our visual representation of religious figures mirror each individual? What happens when that image does not reflect marginalized or disenfranchised communities, BIPOC? How can we justify our beliefs and principles when the visual does not reflect who we are and what we know? The Black Madonna in Częstochowa, who attracts pilgrimages yearly in great numbers, made her way to Poland in the fourteenth century. However, how she made her way onto the earth, in general, is far from simple. In addition, her dark complexion not only raises questions but renders her origins notably perplexing. Some believe that the Black Madonna in Częstochowa was “not made by human hand”3 and that she is a product of acheiropoietoi.4 It is worth noting that the beginning of Christian art is an outcome of the presence of Christ on earth and the desire to capture the ‘true image’ of Christ by early believers. Before Christ, figurative works of the holy had numerous opponents hesitant to accept icons, but as Ewa Kuryluk affirms, “the existence of Jesus, a vera icon of divinity created in Mary’s flesh, calls for representation.”5 An acheiropoietoi image is associated with mystery and supernatural happenings, ultimately determining how the faithful interact with the object. The earliest account of the Black Madonna in Częstochowa states that “Saint Luke painted with his own hands”6 the image in her likeness, thus making it the most true-to-life portrait in possession. Others say that “it was created by angels, while Saint Luke fell asleep,”7 or by Mary herself. It is also said that the surface on which the image is painted is a wooden desk made by Jesus Christ himself. Together these legends emphasizing direct contact between the object and the holy figure enable believers to feel closer to the Black Madonna. Collectively these legends fabricate a narrative centered on false or self-contradictory grounds, which further adds to the inaccurate and biased nature of the archive.

Naturally, patrons want to see themselves reflected within religious imagery. Both White and Black patrons hold on to the narratives or legends that best fit their interest, or support their beliefs, and how they relate to this version of Mary. White patrons attribute her Blackness to a force unbeknownst to man, as one newspaper clipping from 1915 states: “the Madonna was originally painted in flesh tints, but once miraculously turned black overnight.”8 For White patrons, her Blackness must be a miracle, inexplicable by natural or scientific laws, but a divine occurrence rather than her natural complexion. If her White patrons accept her Blackness as part of her ’initial’ origin, they will have to confront their own racial prejudice and beliefs. Their inability to explain her Blackness does not prevent them from fabricating other external possibilities, adding to the bias we face in the archives. For example, some credit her Blackness to aging, accumulation of smoke from the candles, and other environmental factors, as alluded to in a newspaper clipping from 1899.9 They choose to believe that aging or smoke accumulation is responsible for her dark complexion, disregarding that such processes would have darkened other portions of the painting. Besides, this rationalization does not explain why there are Black sculptures of the Madonna from around the same period. It is important to note that over three hundred Black Madonnas exist in both painted and sculptural form, yet her Blackness is still in question. Coming to terms with the possibility that Mary herself could have been a person of color is not an option, although there is a sculpture of the Black Madonna in Sicily dating back to the eighth century with a Latin inscription that states, “I am Black.” Whitewashing influential Black historical figures is a common trope of the colonial period, as lithographs and other visual representations in archives demonstrate.

Despite the attempts to erase the Black Madonna’s true origins, Black believers refuse to accept any justifications that negate her Blackness. In the 1960s, Black reverends such as Rev. Albert B. Cleage from Detroit sought to “restore Christianity to what he considers to be its ‘original’ identity: a black man’s religion.”10 Preaching in front of a Black Madonna, Rev. Albert B. Cleage pushed for “a Black Messiah born to a Black woman”11 and for the Black religion to “reinterpret its message in terms of the needs of the Black Revolution.”12 For the Black population during the Civil Rights Movement, the way Christianity was taught, through the White male perspective, “was a way of directing attention away from social injustice”13 and kept the Black man in his place (enslaved and uninformed of his roots), alleviating the slave owner‘s guilt. For the Black community in the 1960s, when ‘Black is Beautiful’ and ‘Buy Black’ were phrases employed to empower the Black race, it was crucial to “Color God Black”14 and to have religious imagery representing Blackness. The intention behind these images was that Black visual representations would entice Black people to see themselves as active participants of a community, of a country. It was about a self-assurance and self-empowerment through visual representation that exceeds religion.

It is worth noting that “such pictures, chiefly in the form of cheap lithographs, have for years past been supplied to the negroes [Black Americans] and Indians of South America [Latin Americans] by enterprising German printing firms,”15 as stated in a 1924 newspaper clipping from The New York Times. The author Henry C. Hampson writes in the ‘Letter to the Editor’ on 6 August 1924, petitioning for Black representation: “The effect, when seen for the first time, is certainly startling, but in reality, there is little to cause surprise in the fact of negroes making a mental picture for themselves of a black Deity, nor anything to offend the susceptibilities of the white man, however religiously inclined.”16 Henry C. Hampson further states: “What is chiefly remarkable is that the Catholic negroes and Indians of South America have solved this problem for themselves in a simple, natural and inoffensive manner, without any attempt, as was very apparent at yesterday’s convention, to drag in racial animosity.”17 The author chose to highlight the desire to see oneself reflected within these religious imageries without offending White patrons or creating racial animosity, illustrating the silence imposed on Black expressions and voices. His letter emphasizes which groups are in positions of power, and how these groups in power use violence and their positionality to silence disenfranchised communities. Together, these exchanges and written documents from Black and White patrons of the Black Madonna perpetuate the archival inaccuracies with which scholars interested in this subject must contend.

Part 2: The Haitian Revolution, The Black Madonna, and Erzulie Dantor

In the early 1800s, when the Black Madonna made her way into Haiti in the form of cheap miniature lithographs within the pockets of Polish soldiers sent forth by Napoleon to fight against the rebels, the Madonna was further recontextualized. She was adopted into the Afro-Syncretic religion of Haitian Vodou, taking on new meaning, with her image gaining another layer of mystery. Napoleon Bonaparte’s attempts to recapture the French colony of Saint-Domingue, modern-day Haiti, ironically backfired when the Polish soldiers he sent in 1802 switched sides, joining the Black insurgents. Haitian accounts speak of a Vodou ceremony (Bois Caïman ceremony) before the uprising of 1791 against the French colonizers, in which a new loa (deity) emerged, born to Haitian soil. The loa is Erzulie Dantor, regarded as the mother of Haiti. She has origins at the inception of the uprising. Erzulie Dantor became an inspiration for the enslaved people of Saint-Domingue, who were struggling for liberation and independence from their oppressors. By 1802 the war was eleven years in and still two years from its end when the image of the Black Madonna in Częstochowa appeared as a symbol that inspired the Haitian rebels and provided the incentives they needed during the last months of the revolution. When the Polish troops joined the Haitian army, this solidified Haitians’ beliefs that the lithograph of the Black Madonna that Polish troops brought with them was, in actuality, Erzulie Dantor. The Polish soldiers, and the image of the Black Madonna they carried, revived the revolution.

Numerous Polish troops sided with the Haitian army. They were dissatisfied with the French forces, which disregarded and undervalued their demi-brigades. Furthermore, they were seeking independence for Poland by oppressing another country, and could not ignore the irony of this situation. In 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte vowed to re-establish Poland as a nation if they joined his army, but in actuality he had little intention of doing so. The French coerced the Polish troops into action. Around 5,300 troops landed in Haiti, having been misinformed by the French that they would be landing in Louisiana-State instead of Saint-Domingue. In the following months, about 4,000 troops “died on the distant island: as prisoners, drowned, killed in battle, or—primarily by the yellow fever.”18 As a result, Polish demi-brigades departed for the rebel army, “where Dessalines nicknamed them the negroes of Europe.”19 General Dessalines granted the remaining 400 Polish soldiers Haitian citizenship, giving the “order to spare the lives of Poles because he was touched […] Polish soldiers had joined the uprising.”20 These events provide a context for the incorporation of the Black Madonna in Częstochowa into Haitian culture.

The Polish soldiers that arrived in Haiti during the final months of the revolution helped carry it towards victory. The image of the Black Madonna that they brought with them did not go unnoticed. Her story was to be forever cemented in the birth of the Haitian nation, culture, and belief system. For example, the author of a 1966 article discusses the importance of the “American Czestochowa” in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. The “American Czestochowa” houses a shrine for a reproduction of the Black Madonna that was celebrating its fiftieth anniversary in 1966. The author notes that “Czestochowa’s role is shifting,”21 elaborating further that: “members of the Haitian community have for many years made pilgrimages to Doylestown to honor the Black Madonna, who is also revered by some as a representation of the Vodou deity, Erzulie Dantor.”22 This detail matters because it illustrates the complexity and multiple dimensions underlying the Black Madonna. Both White and Black patrons, from different geographical locations, Poland and Haiti, find their way to this image in America (a third nation), to pay tribute to two distinctive translations of this religious imagery. One group is partaking in a pilgrimage to the Black Madonna and the other to the Vodou loa Erzulie Dantor, but both regard the same image with adoration. This image travels through various geographical locations across time, being associated with infinite narratives. In a sense, she experiences a rebirth in each new context. However, despite the evolution, endless admiration, and constant desire to protect her image, there is ironically a continuous silencing of the Black Madonna in Częstochowa.

Countless fabrications and inconsistencies circulate the true origins of the Black Madonna in Częstochowa, all of which are distinctive and support multiple beliefs. However, the most logical explanation, overlooked by records, is that “it is possible that some of the oldest [Black Madonnas] are imported figures of Isis,”23 as stated in a newspaper clipping from 1899 in The New York Times. I argue that this is the most sensible explanation for her dark complexion. Isis, an Ancient Egyptian goddess, is an African figure, reported to be of dark complexion. The Black Madonna in Częstochowa, as stated earlier, was found in Jerusalem in 326 by Saint Helena. Jerusalem may be reached from Egypt on foot in a little over a week. As the gospel reports, Joseph, Mary, and Jesus went to Egypt to escape Herod’s great slaughter of baby boys in Bethlehem, thus illustrating the historic cultural exchange between these two nations. We can therefore conclude that the Black Madonna has experienced both displacement and wrongful identification. External beliefs projected onto her have ultimately perpetuated misinformation and silenced her true origins, Africa. The Egyptian goddess, Isis (Queen of the Throne), similarly to the Virgin, is a virgin who births children, a compassionate, selfless, and giving mother. As we shall now see, ironically, Haitian adaptations of the Black Madonna in Częstochowa into Haitian Vodou as loa Erzulie Dantor have enacted a similar process to that of the fourteenth-century Polish patrons who imposed another identity onto this painting.

What is noteworthy about the adaptation of the Black Madonna in Częstochowa into Haitian Vodou is that Erzulie Dantor is a unique product of the New World and religious syncretism. Erzulie Dantor is a collage of various sources encompassed as one, original to Haiti and its nation-building project, which began in 1791. She is neither Catholic, nor from Yoruba traditions, the common combination of Afro-Syncretic religions. She emerges from the enslaved Africans and is exclusive to Haiti and the New World. However, even though she is the youngest variation or adaptation of this portrait, her story is fractured. With her various incarnations and many faces, her mere existence is a reminder of the impact of colonialism on women’s experiences not only in Haiti but everywhere in the Caribbean.

Erzulie is one to Haiti, and analogies that align her with other religions or belief systems are unjustified. Yet, there are various versions of Erzulie, each connected to a version of the Virgin Mary, for example, Erzulie Dantor and the Black Madonna, or Erzulie Freda and Our Lady of Sorrows, with the skin complexion of both pairings coinciding. Erzulie Dantor is Black, Erzulie Freda is White, like their respective saints. In Haiti, there are three popular Erzulie recognized as such: Erzulie-Freda (White lady of luxury and love), Erzulie-Dantor (Black woman of passion with a dagger in her heart), and Erzulie-Ge-Rouge (red-eyed militant of vengeance). In Erzulie: A Women’s History of Haiti (1994), the author Joan Dayan demonstrates how authors such as Roumain, Alexis, and Chauvet turn to analogy. They describe Erzulie Dantor as Venus or the Virgin. However, the author suggests that when addressing Erzulie, we should “forgo such external impositions […] instead [trying] to talk about the continuing presence of Erzulie through those relationships and events particular to women in Haiti whether black, mulatto, or white.”24 By abandoning such external impositions, we may preserve the original voice of Erzulie and prevent further misconceptions that may erase her true nature. Problems arise when we identify different Erzulies, pitting them against each other, and thereby perpetuating the erasure of a full picture. The author exposes the issues that arise when women are either erased from narratives, or written into them by men who dictate their voices.

As Dayan points out, “everything written about Erzulie can be contradicted.”25 Records showcase Erzulie as the loa of lust prayed to by prostitutes, as a goddess served by Haitian elites, young virgins, and the LGBTQ+ community, as they are all her children. Some feminist scholars argue that “to be Erzulie is to be imagined and perceived by men.”26 Women like Erzulie are split into objects to be desired or abhorred. Based on the imaginations of men, women are confined to specific roles. They are either one or the other, presented as stereotypes of Black or White women, like the “spiritualized and de-sexualized images of white women”27 that are only made possible by the “prostitution or violation of the dark women in their midst.”28 The splitting of Erzulie mirrors the roles of women that adhere to the beliefs of men. One such example is the fabrication of a corrupted dark woman invented by the male imaginary and colonized gaze. Vodou is an arrangement of colonial and post-colonial memories of the enslaved that continues to be passed down to their descendants. The loas are creations of enslaved peoples of Caribbean history, as seen through the colonized gaze. It is about the lives they live, their experiences, and their education. The various identities of Erzulie are reflections of the numerous roles performed by women. However, the issue is “whether called whore or virgin, women seem always to find themselves in the hands of the definers.”29 Splitting Erzulie into these distinct fixed ideas of women who are “lady” or “savage” does not give her the agency to freely exist, making her incomplete, and thus silencing her.

Part 3: Colonial Legacies, Archival Silences, and Black Scholars and Artists’ Attempts to Recover Black Women’s Voices

To construct a narrative about the Black Madonna in Częstochowa and her various incarnations, for once, we must be critical of our use of documentary sources that speak for her. The Black Madonna in Częstochowa has a complicated and unfinished history, fragmented in scattered archival records, across numerous institutions. Black scholars or artists employing the Black Madonna in Częstochowa as a topic or source of creative inspiration must see the “archives as epistemological experiments rather than as sources.”30 The archives and their records are not sites of historical truth. The archives house official documents of the state, yet this does not exempt them from bias structures, as “cultural accounts were discredited or restored”31 according to the state’s interests. Scholars must read through the absence of sources as “colonial archives were both sites of the imaginary and institutions that fashioned histories as they concealed, revealed, and reproduced the power of the state.”32 Scholars must read against the grain of the archives, as well as with the grain. They must do this while being attentive “for its regularities, for its logic of recall, for its densities and distributions, for its consistencies of misinformation, omission, and mistake.”33 It is necessary to acknowledge the issues with archives in order to prevent further inaccuracies and mistakes as scholars continue to develop and share their research.

I argue that all archives are colonial, or influenced by colonialism. For example, “a historic social hierarchy exists within the black community, most notably along lines of class, gender, and sexual orientation; this stratification creates prohibitive selection dynamics similar to those in traditional archives.”34 Even within marginalized groups, hierarchical structures dictate which cultural accounts are preserved. Afro-syncretic religions have historically been stigmatized as backward within some elite circles. Therefore, it is not unusual for Afro-Caribbean religious practices to be underrepresented in the archives. It is not sufficient to read “against the grain” of the colonial archives; we must also recognize the internalized prejudices and standards of inclusion within Black archives themselves. Black focus archives are not exempt from the “traditional appraisal and selection models that excluded minority groups.”35 The first Black archives are products of an “elite class of college-educated intellectuals”, and “these early pioneers, such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson, believed that Black history and education were requisite components for racial advancement.”36 This observation matters because the standard of elitism for racial progress influenced what entered into the archives for both remembrance and as an example of Black excellence. Those works that did not fit within the elite frameworks of college-educated intellectuals thus fell short, and were neither prioritized nor counted.

There has been a “move from archive-as-source to archive-as-subject [gaining] its contemporary currency from a range of different analytic shifts, practical concerns, and political projects.”37 For example, Michel-Rolph Trouillot, in his treatment of the archival silences of the Haitian Revolution, is an example of this shift whereby scholars are becoming active participants in their approach to the archives. This portrait of a Black mother and child often termed the ‘Black Madonna of Częstochowa’ is ironically a product of archival silence. It is one of the most recognized images, adored by various patrons, and a source of creative inspiration for numerous artists. Nonetheless, the inconsistency of her story and the endless adaptation of her portrait has erased the voice she was initially intended to have. Numerous people make the pilgrimage hoping that their prayers are heard, disregarding how she herself has been rendered mute by their actions.

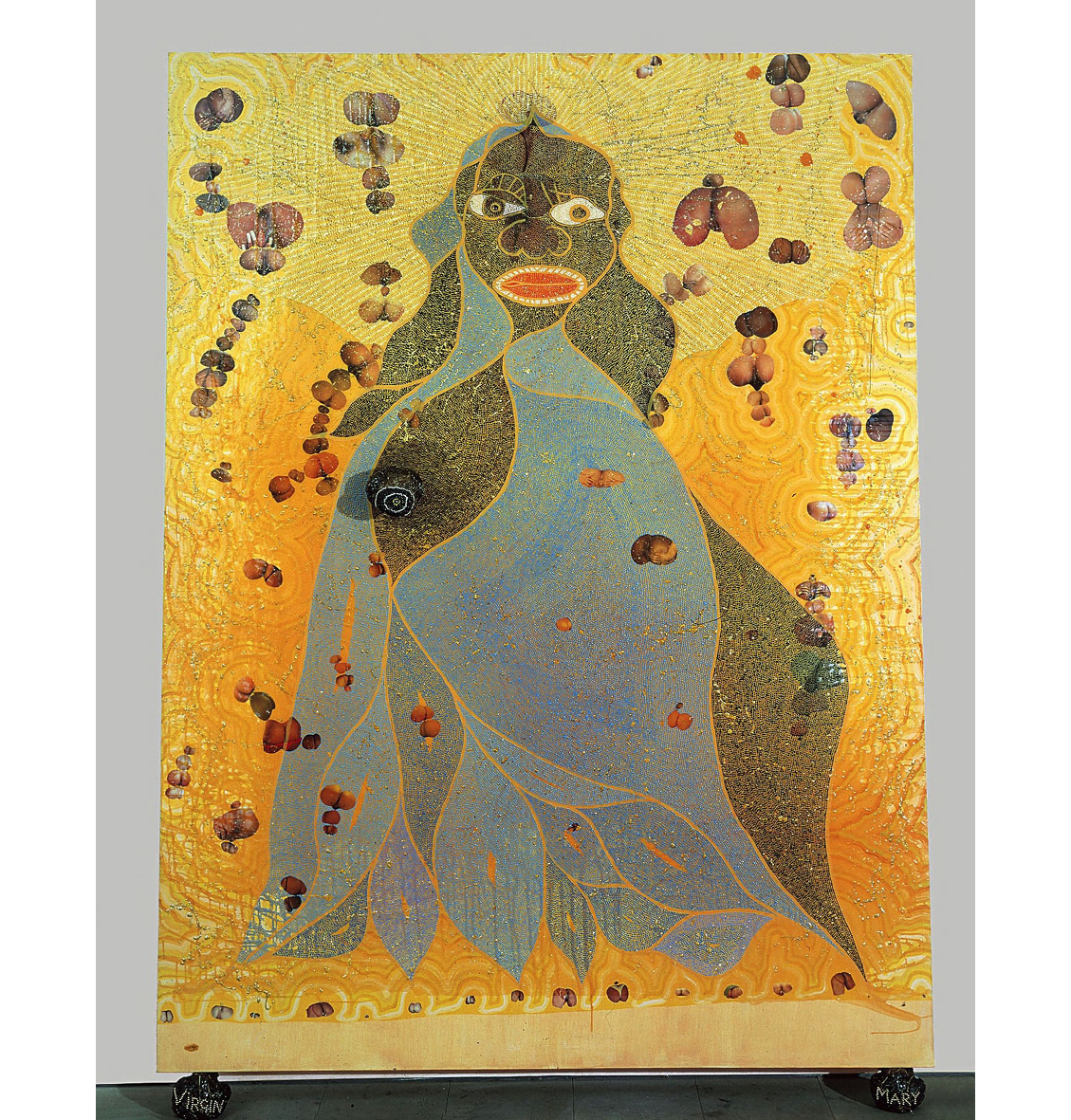

“Whether documents are trustworthy, authentic, and reliable remain pressing questions,”38 but how scholars and artists become consciously active participants of history depends on the individual. The fact that irregularities exist within the archives is undisputable. Their foundations uphold colonial agendas. The sources are manipulated, the “publishing houses made sure that documents were selectively duplicated, disseminated, or destroyed,”39 and that documents were “properly cataloged and stored”40 to their liking. Everyone working in archives should ask themselves: “what political forces, social cues, and moral virtues produce qualified knowledges that, in turn, disqualified other ways of knowing, other knowledges”?41 Black contemporary artists, attempting to recover Black voices, are thus challenging what we know, which relates to the archives and the colonial production of knowledge. For example, in 1999, The Holy Virgin Mary by Chris Ofili, depicting the Virgin Mary (Black Madonna) “with a clump of elephant dung on one breast,”42 almost caused the financial destruction of the Brooklyn Museum (see Figure 2). In 2001, Renée Cox’s Yo Mama’s Last Supper, a nude self-portrait of the artist in Christ’s place at the Last Supper, drew public outcry. Additionally, New York-based photographer Jon Henry’s series Stranger Fruit (2014–present) draws the classical Pietà for inspiration for his portraits of Black mothers cradling their sons. Jon Henry began the series Stranger Fruit in 2014 as a commentary and a form of response to the police murders of Black men: “Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice and continues as they never seem to end.”43

In 1999, London-based artist Chris Ofili participated in the Brooklyn Museum exhibition Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection with a painting of “a Black Madonna with a clump of elephant dung on one breast and cutouts of genitalia from pornographic magazines in the background.”44 The following day, then-mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani stirred a political and religious furor, encouraging people to protest the exhibit, and threatening to cut the museum’s funding. The support of the mayor and the Catholic League empowered and provoked individuals like Dennis Heiner, a seventy-two-year-old white male, who removed “a plastic bottle from underneath his arm and squeezed white paint in a broad stroke across the face and body of the Black Madonna.”45 This individual felt an entitlement and ownership of the Madonna, hence his deliberate attack on Chris Ofili’s version of the Virgin. This gesture was a sinister act of violence and erasure of Black perspectives, which I argue is derivative of the mechanism of archival silences. Additionally, this act against Chris Ofili’s painting is a product of the misguided and misrepresentational nature of religious imagery perpetuated over time in the archives of individuals who choose to see the raw sources without examining them. As Chris Ofili said, “the people who are attacking this painting are attacking their own interpretation, not mine.”46 They are once more projecting their views onto others, deciding which stories to value and which to discredit.

Fig. 2 Chris Ofili, The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), © Chris Ofili, image courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and David Zwirner.

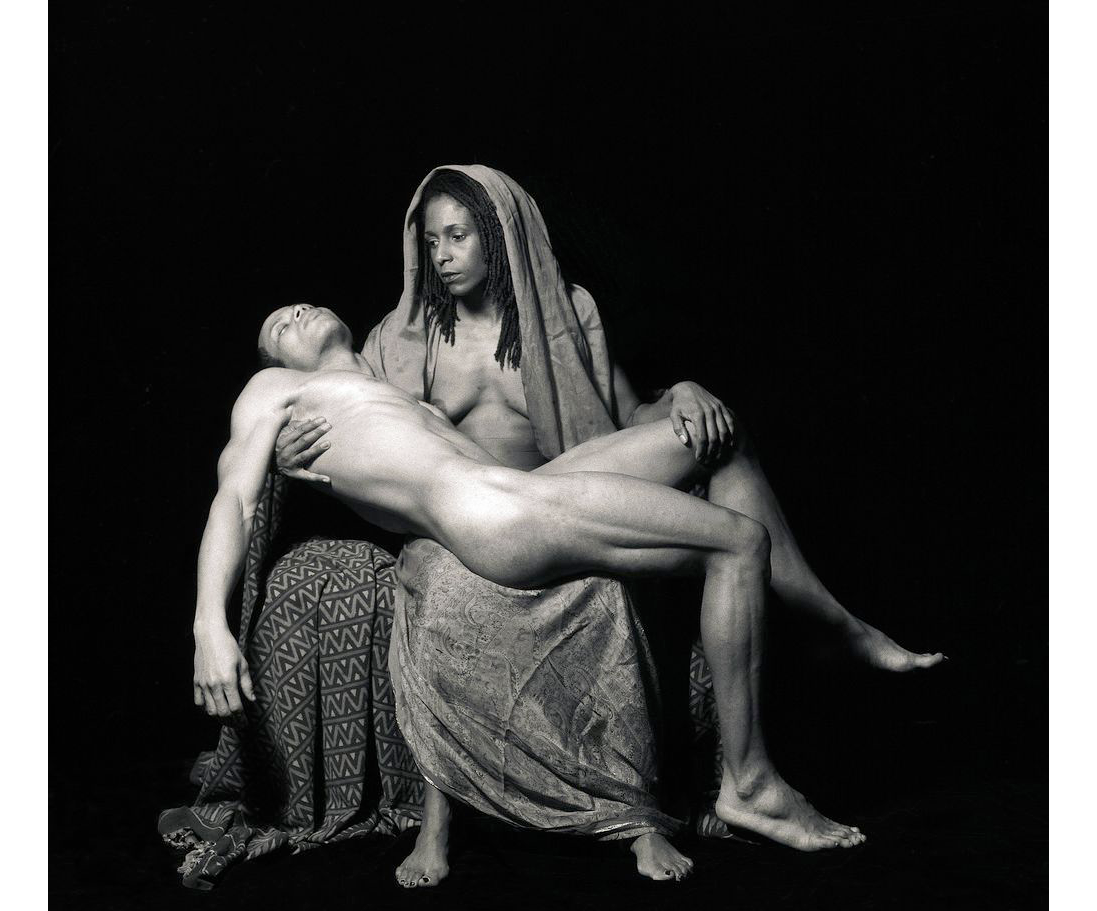

In 2001, the Brooklyn Museum again drew negative attention, this time over photographer Renée Cox’s Yo Mama’s Last Supper. Once more, Rudolph W. Giuliani and the Catholic League were at the forefront of the controversy. Instead of threatening to pull funds, Giuliani vowed to “appoint a commission to set [decency standards] to keep such works out of museums that receive public money.”47 He describes the work as “disgusting, outrageous, and anti-Catholic,”48 rallying protestors to censor the artist, discrediting her work and perspective. Whether the public agrees with the artist or not, the “link between what counts as knowledge and who has power, has long been a founding principle of colonial ethnography,”49 manifesting in various facets of life. Renée Cox’s body of work is an act of resistance against the Whitewashing of the Black Madonna. The Yo Mama series also includes the classical Pietà of a half-nude Renée Cox with a veil made of fabrics as she observes and embraces the sitter in the position of Christ (see Figure 3). Renée Cox’s artworks incorporate topics of motherhood and social critiques of institutionalized religion. Cox replied to the controversy by confronting the Catholic critics: “I have a right to interpret the Last Supper just as Leonardo da Vinci created the Last Supper with people who look like him.”50 By embodying the Black Madonna, Cox gives agency to Black women and takes a political stance that draws awareness to marginalized voices and perspectives that have been silenced by colonialism and its legacies. In effect, her body of work challenges and addresses structural silences.

Fig. 3 Renée Cox, Yo Mama’s Pietà, 1994.

Fig. 4 Jon Henry, Untitled #29, North Miami, FL, 2015.

New York-based photographer Jon Henry takes on a similar approach as Renée Cox through his series Stranger Fruit (2014–present) (see Figure 4). He brings into conversation religion and institutionalized racism. His photographs of Black mothers holding their sons allude to Michelangelo’s Pietà through a political lens. The difference with Jon Henry’s photography is that in these portraits, the mothers almost always return the viewers’ gaze directly. With this stylistic choice, these mothers are active participants in confronting the public. Their eyes urge spectators to take notice and to be part of the movement to dismantle police brutality and all the senseless deaths of Black men. By employing the Pietà, Jon Henry strategically illustrates the irony and contradictions of institutionalized religions when it comes to marginalized BIPOC communities. He draws attention to the countless murders inflicted by the police while utilizing iconic religious imagery, forcing viewers to pay attention to Black women and their voices, narratives, and pain.

Together, these artists employ religious imagery to reassess and recover the untold narratives of Black women. In effect, they give agency to the Black Madonna and acknowledge her Blackness via everyday Black women. Yet, certain opponents utilize modern tactics to silence these artists, thus acting on the colonial tropes visible in the archives. We must ask who has ownership of the Madonna, and why? Which institutions validate dominant views of this religious imagery, and how does it partake in the erasure of the subject’s true origins? Can a singular demographic dictate how to represent her image? Despite the contradictions surrounding this image, she is foremost a mother figure to numerous patrons, both Black and White, whether regarded as Isis, the Black Madonna in Częstochowa, or as Erzulie Dantor. However, that does not justify the erasure of her true origins, and I argue that it should act as a motivator for scholars, who as knowledge producers are morally obligated to correct such inaccuracies.

Bibliography

“Black Images of the Madonna”, The New York Times, 1 January 1899, 19.

Bumiller, Elisabeth, “Affronted by Nude ‘Last Supper,’ Giuliani Calls for Decency Panel”, The New York Times, 16 February 2001.

Dayan, Joan, “Erzulie: A Women’s History of Haiti”, Research in African Literatures 25/2 (1994), 5–31, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4618262.

“Famous Shrine One Oasis In War”, The New York Times (18 March 1915), 4.

Feinstein, Jon, “These Portraits Process Black Mothers’ Greatest Fear”, Humble Arts Foundation, 15 October 2020, http://hafny.org/.

Fiske, Edward B., “Color God Black”, The New York Times, 10 November 1968, 249.

Gibbs, Rabia, “The Heart of the Matter: The Developmental History of African American Archives”, The American Archivist, 75 (2012), 195–204, https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.75.1.n1612w0214242080.

Hampson, Henry C., “Representing Deity As Black”, The New York Times, 6 August 1924, 150.

Kolankiewicz, Leszek and Olga Kaczmarek, “Grotowski in a Maze of Haitian Narration”, TDR 56/3 (2012), 131–40, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23262938.

Mcfadden, Robert D., “Disputed Madonna Painting in Brooklyn Show Is Defaced”, The New York Times, 17 December 1999, https://www.nytimes.com/1999/12/17/nyregion/disputed-madonna-painting-in-brooklyn-show-is-defaced.html.

Niedźwiedź, Anna, The Image and The Figure: Our Lady of Czestochowa in Polish Culture and Popular Religion (Krakow: Jagiellonian University Press, 2010).

Rzeznik, Thomas, “[About the Cover]: The National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa”, American Catholic Studies, 127/2 (2016), 97–106, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44195846.

Stoler, Laura Anne, “Colonial Archives and the Acts of Governance”, Archival Science, 2/1 (2002), 87–109, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435632.

Vogel, Carol, “Holding Fast to His Inspiration; An Artist Tries to Keep His Cool in the Face of Angry Criticism”, The New York Times, 28 September 1999, https://www.nytimes.com/1999/09/28/arts/holding-fast-his-inspiration-artist-tries-keep-his-cool-face-angry-criticism.html.

Williams, Monte, ”‘Yo Mama’ Artist Takes on Catholic Critic”, The New York Times, 21 February 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/02/21/nyregion/yo-mama-artist-takes-on-catholic-critic.html.

1 Laura Anne Stoler, “Colonial Archives and the Acts of Governance”, Archival Science, 2/1 (2002), 87–109 (p. 99), https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435632.

2 The phrase “Image of God” has its origins in Genesis 1:27, wherein “God created man in his own image […]” This phrase does not suggest that God is in human form. What it insinuates is that humans resemble the image of God morally, spiritually, and intellectually. The metaphysical expression is associated solely with humans, which signifies the symbolic connection between God and humanity.

3 Anna Niedźwiedź, The Image and The Figure: Our Lady of Czestochowa in Polish Culture and Popular Religion (Krakow: Jagiellonian University Press, 2010), p. 6

4 This is a Medieval Greek word meaning “made without hands” and referring to images thought to have been made without hands. These are Christian icons whose existence in itself is a miraculous act. I am using Niedźwiedź’s spelling of the word.

5 E. Kuryluk, Veronica and Her Cloth. History, Symbolism, and Structure of a “True” Image (Cambridge, MA: Oxford, 1991), p. 8. Cited in Niedzwiedz (2010), p. 5.

6 H. Kowalewicz (ed.), Najstarsze historie o Częstochowskim Obrazie Panny Maryi XV i XVI wiek, trans. H. Kowalewicz, M. Kowalewiczowa (Warszawa, 1983), p. 75. Cited in Niedźwiedź (2010), p. 12.

7 M. Skrudlik, Królowa Korony Polskiej. Szkice z historii malarstwa i kultu Bogarodzicy w Polsce (Lwów, 1930); Cudowny obraz Matki Boskiej Częstochowskiej (Kraków, 1932), p. 64. Cited in Niedźwiedź (2010), p. 13.

8 Staff Correspondent of The Times, 18 March 1915, p. 4.

9 Monte Williams, “Yo Mama” Artist Takes on Catholic Critic”, The New York Times, 21 February 2001. Section B, p. 3.

10 B. Albert Cleage, cited in B. Edward Fiske, “Color God Black”, The New York Times, 10 November 1968, p. 249.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Henry C. Hampson, “Representing Deity As Black”, The New York Times, 6 August 1924, p. 150.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Leszek Kolankiewicz and Olga Kaczmarek, “Grotowski in a Maze of Haitian Narration”, TDR (1988-) 56/3 (2012), 131–40 (p. 132), http://www.jstor.org/stable/23262938.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Thomas Rzeznik, “[About the Cover]: The National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa”, American Catholic Studies, 127 (2016), 97–106 (p. 106).

22 Ibid.

23 “Black Images of the Madonna”, Notes and Queries, The New York Times, 1 January 1899, p. 19.

24 Joan Dayan, “Erzulie: A Women’s History of Haiti”, Research in African Literatures 25/2 (1994), 5–31 (p. 6), http://www.jstor.org/stable/4618262.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid., p. 7.

27 Ibid., p. 8.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid., p. 15.

30 Stoler, p. 87.

31 Ibid., p. 98.

32 Hyden White (1987), p. 12. Cited in Stoler, p. 97.

33 Stoler, p. 100.

34 Rabia Gibbs, “The Heart of the Matter: The Developmental History of African American Archives”, The American Archivist, 75 (2012), 195–204 (p. 197), https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.75.1.n1612w0214242080.

35 Ibid., p. 195.

36 Ibid., p. 200.

37 Stoler, p. 93.

38 Ibid., p. 91.

39 Ibid., p. 98.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid., p. 95.

42 Carol Vogel, “Holding Fast to His Inspiration; An Artist Tries to Keep His Cool in the Face of Angry Criticism”, The New York Times, 28 September 1999, Section E, p. 1.

43 Jon Feinstein, “These Portraits Process Black Mothers’ Greatest Fear”, Humble Arts Foundation, 15 October 2020, http://hafny.org/.

44 Vogel.

45 Robert D. Mcfadden, “Disputed Madonna Painting in Brooklyn Show Is Defaced”, The New York Times, 17 December 1999, Section A, p. 1.

46 Vogel.

47 Monte Williams, “Yo Mama” Artist Takes on Catholic Critic”, The New York Times, 21 February 2001.

48 Bumiller, Elisabeth, “Affronted by Nude ‘Last Supper,’ Giuliani Calls for Decency Panel”, The New York Times, 16 February 2001, Section A, p. 1.

49 Stoler, p. 96.

50 Williams.