7. The Fiction of the Empty Pandemic City: Race and Diaspora in Ling Ma’s Severance

© 2022 Rishi Goyal, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0303.07

‘It takes hard work not to see’.

—Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark

During a zoom conversation in May of 2020, my younger brother, a conservationist living in Kathmandu, mentioned how clean and sweet the air seemed. During that year, we were flooded with colour coded satellite images of improved air quality and lower levels of pollution, from the megacities of the global South to the Northern highlands, as people fled infected cities and the world economy came to a screeching halt. As humans supposedly abandoned Rome, London, Mumbai and Tel Aviv, reports suggested that wildlife were repopulating urban spaces and that countless animals and vegetation were rewilding the world’s cities. But many of these stories, both about the cities emptying of people and about animals and plant life resurging, are fictions. The photos showing the return of animals or of emptied cities have often been revealed as fakes: doctored images or historically unrelated. And while certain people definitely fled the city, a new twenty-first-century white flight, many more people could not. In New York City, the quiet of the streets was punctuated by both an increase in bird song and an increase in ambulance sirens.

Fig. 16 Sourav Chatterjee, 49th St. between 7th and 8th Ave (2020) © Sourav Chatterjee. Editorial use.

Fig. 17 Reena Rupani, Times Square (2020) © Reena Rupani. CC BY-NC.

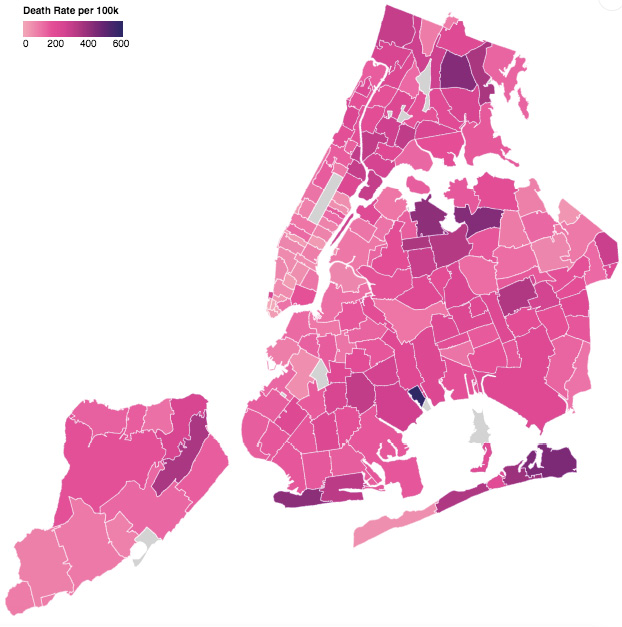

Ambulance call volumes nearly doubled from late March to early April. But they only increased in lower socioeconomic status (SES) areas which are predominantly populated by black and brown people, while the call volumes decreased in higher income areas where many residents fled the city.1 The emptying of the city is a pandemic fiction that masks the uneven class and race effects of biological catastrophes.2 The ‘empty city’, I suggest, focuses our attention on the racialized nature of biopolitical existence while also magnifying the uneven effects of restrictions or regulations on movement: immigration bans, cordon sanitaire, quarantine, shelter-in-place orders.

Fig. 18 NYC Health Department, Coronavirus death rate by zip code (2020) © Courtesy of NYC Health Department. The interactive map reveals that there was a striking increased mortality rate among people of colour and those that lived in poor neighbourhoods.

As an Emergency Medicine physician, I treated hundreds of patients with severe pneumonia from COVID-19 when New York City was the epicentre of the pandemic. Many, if not most of them, died. The overwhelming majority of those that were sick and those that died were black and brown. The neighbourhood that I live in, Harlem, and the neighbourhood that I work in, Washington Heights, were full of people, people who often got COVID-19. While other neighbourhoods, SoHo, the West Village, the Upper East Side, felt like ghost towns as their primarily white and/or wealthy residents fled the city. The spatial logic of COVID-19 was overwhelming even as it revealed class and race differences.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the biopolitical assemblage: biology and politics have grown ever increasingly intertwined in the last two centuries as populations become the site of political power. Public Health concerns and policies now influence all aspects of civic life ranging from urban planning and transportation services to housing and environmental protection. Pandemic fictions, an increasingly popular genre, help mould and imagine this constellation. Unlike other dystopic or catastrophic imaginaries (like ecological disaster, alien invasion, supernatural apocalypse, AI or technology) pandemic fiction often portrays a city left standing but empty of its humans. The physical infrastructure of highways and buildings remain mostly undisturbed, but the human infrastructure has been decimated. People are imagined leaving the city behind because there is something particularly infectious about the city itself. In films like Francis Lawrence’s I am Legend (2007), in video games like The Last of Us (2013), and in novels like Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven (2014), and Ling Ma’s Severance (2018), buildings, highways and roads remain undamaged, but cities are rapidly depopulated as people are either killed by the infection or flee to the countryside. Even Daniel Defoe’s 1722 Journal of the Plague Year, a fictionalized account of the 1665 great plague of London, depicts the flight from the plague city: ‘[O]ne would have thought the very City itself was running out of the Gates, and that there would be no Body left behind’.3

Pandemic fiction and the fiction of the pandemic both imagine an emptied city as a response to or an effect of biological catastrophe. But why does the catastrophic imaginary of pandemic fiction envision an empty city when the reality is more likely that the poor and brown and black people will not and cannot leave? In White Flights, Jess Row writes, ‘In a country shaped by colonization, enslavement, and racialized capitalism—practices of exclusion and exploitation very much alive in the early twenty-first century—few spaces remain empty by accident’.4 This is true for fictional and counterfeit emptiness as well. Row then observes that, ‘[t]here are implicit and explicit barriers that govern the visible world, and these lines are themselves a design, or authorship, that deserves to be read’. The empty city of the pandemic is empty of some people but full of others, even if they are not visible. In what follows, I want to explore the fiction of the empty city of the pandemic. I want to repopulate the fictional city with the many essential workers, precarious peoples, everyday inhabitants, street homeless and other individuals who lived through New York City in particular as it was struck by the COVID-19 pandemic, even as essential services—the subways, street cleaning, garbage pickup, and park maintenance—were cut in real time.5 These cuts and austerity measures follow a long tradition of racialized public health and urban planning like ghettoization, gentrification, and quarantine. While exposing the dangerous fiction of the empty city, I will develop a reading of Ling Ma’s debut novel Severance as it entangles these questions with global immigration patterns, racial identity formation and the haunted cityscape.

‘White flight’, the rapid post World War II migration of white Americans out of cities and into the suburbs and exurbs, was not a random or self-originating event, somehow representing the spirit of the people. It was a function of racist urban planning and housing policies in response to the new (albeit temporary) mobility of black Americans. As black people migrated to cities like Chicago and New York, some whites, threatened perhaps by the loss of what W. E. B. Dubois called the ‘psychological wage’ of being white (whiteness as a psychological compensation for low actual wages)6 first resorted to terrorist fire bombings and harassment,7 and then ultimately left the cities for segregated planned communities like Levittown. As Ta-Nehsi Coates writes, ‘[W]hite flight was a triumph of social engineering, orchestrated by the shared racist presumptions of America’s public and private sectors’.8 The urban blight resulting from redlining and white flight during the 1950s and 1960s was further promoted by diminished funding for the inner cities, the crack wars and a presumed threat of violence during the 1970s and 1980s.

That urban breakdown occurring in the context of the intermingling of blacks and whites is often described in terms of biological metaphors like blight (a disease in plants caused by other species like fungi) is no accident. There is a long history of understanding urban degradation in biological terms, especially in relation to infectious diseases. But the effects of real infectious diseases can provide the optics for a social analysis of the urban. Historian Charles Rosenberg derived a narrative structure of a society’s and individual’s response to epidemics: ‘Epidemics start at a moment in time, proceed on a stage limited in space and duration, follow a plot line of increasing revelatory tension, move to a crisis of individual and collective character, then drift toward closure’.9 In this three-act play, the epidemic reaches an individual and societal crescendo that is marked by a crisis which puts pressure on the social fabric. Epidemics perform a kind of social analysis, revealing who and what is valued. Continuing the theatrical analogy, if the epidemic is a tragedy, then this moment is an anagnorisis, what Aristotle in his poetics referred to as ‘a change from ignorance to knowledge’ or recognition of a hidden truth,10 the truth here being that some people are valued more highly than others. This lifting of the veil exceeds the scale of local or national politics, and that of a well-defined period. As we engage in a history of the present, we might ask whether our current pandemic is an exceptional event or an everyday event. Malaria kills more than 400,000 people a year, AIDS killed 770,000 in 2018 and Tuberculosis kills more than 1.5 million annually. 800,000 children die from diarrheal illness every year.11 These deaths, like the COVID-19 deaths, are not distributed evenly but follow the geospatial patterns of colonial history. The vast majority of all of these deaths from treatable and curable infectious disease are in Africa and Southeast Asia. Even during the AIDS epidemic, leading health experts suggested that the era of infectious disease was over and had been replaced by chronic diseases of lifestyle.

Every year in the winter months our urban emergency rooms see a surge of patients with fever and cough. The number of emergency visits doubles in the winter, especially in areas that are servicing poor, minority, and otherwise marginalized communities. Because of antigenic shift (the recombination of genes from different strains of a virus) and antigenic drift (the accumulation of minor genetic mutations), influenza is rendered a ‘constantly emerging disease’. Flu kills at least 50,000 people in the US per year and perhaps a million worldwide. Our seasonal flu epidemic is the norm every winter. Epidemics and pandemics are catastrophic but singular events that have demarcated beginnings and ends. But in the contemporary world, they have become regularized, ongoing, and without end. Epidemics have become endemic. How else can we still refer to AIDS as an epidemic if it has persisted for forty years? Infectious diseases, modelled and theorized as epidemics, resist the rhetorical transformation to endemics. The colonial language of epidemics links it to early nineteenth-century problems of swamps or miasma or nonhuman spaces; but the modern flu and COVID-19 pandemics are specifically the results of human practices and intervention: global urbanization, agribusiness, industrial livestock production, and deforestation.

To begin to understand and theorize the uneven distribution of deaths and the contradictions of care they entail in endemic and epidemic diseases, we may find some provisional approaches in Michel Foucault’s concepts of biopower and biopolitics. While the notion is sometimes more suggestive than precise, biopower is comprised of a series of regulatory policies, disciplinary practices, and epistemic shifts centred on the body and population that we can all recognize. Distinguishing between the rights of the sovereign and those under biopower, Foucault writes: ‘If genocide is indeed the dream of modern powers, this is not because of a recent return of the ancient right to kill; it is because power is situated and exercised at the level of life, the species, the race, and the large-scale phenomena of population’.12 Foucault marks a shift from a sovereign power with its right to kill to a late eighteenth-century biopower which circulates between the disciplinary order of the body and the biopolitical optimization of the population. But Foucault asks, if the end of biopower is to increase life, prolong its duration, improve its chances, how is it possible for this political power to kill? It is here that we see the birth of state racism. Race enters directly into the basic mechanisms of state power. Racism is the ‘indispensable precondition’ that authorizes the biopolitical state’s right to kill.13 The optimization of life under biopower relies on a distinction and hierarchy among races to produce groups within the population—on the one hand, fit and vital, and on the other, endemically unfit, inferior, and unhealthy: ‘[R]acism justifies the death function in the economy of biopower by appealing to the principle that the death of others makes one biologically stronger insofar as one is a member of a race or a population, insofar as one is an element in a unitary living plurality’.14 The disproportionate mortality rates among minority populations during the COVID-19 (and also the Spanish Flu) pandemic seems to reflect this state. Social distancing is an example of biopolitical regulation/regulatory biopower. Only the ‘fit and vital’ can engage in social distancing while the unfit populations of racialized essential workers—who are more likely to take public transportation, to not have second homes to escape the cities, to work in jobs that cannot be performed at home, to live in multigenerational families, to suffer the effects of pollution and overcrowding—die.

Ling Ma’s 2018 debut novel, Severance, a love affair with New York City as well as a dystopian pandemic fiction, hints at this contradiction. A fungal pandemic originating in China disrupts global supply chains and ultimately wipes out most of the world’s population. While the novel is conventionally realistic in many aspects, the symptoms of the infection include becoming stuck in an endless loop of everyday tasks, eventually dying of something like malnutrition. The novel proceeds from the protagonist Candace Chen’s perspective in alternating recursive chapters that narrate her flight to and away from the city. In the post-flight narrative, Candace and a small band flee the city together to make a new home at a commune ironically set in a suburban shopping mall. But the pre-flight narrative that details her parent’s emigration from Fungzhou, China and her own immigrant or diasporic experience sustains the interest in the story. In narrating her parents’ achingly banal attempts but heartbreaking failures to assimilate into American life, Candace prefigures the effects of the pandemic. Shen fever, caused by a fungal infection originating in Shenzen, China, ultimately decimates and destroys the human population, but not before transforming the victims into zombie like automatons, endlessly repeating everyday routinized tasks like setting a table or folding clothes in a department store: ‘It is a fever of repetition, of routine’.15 As the post-colonial scholar Anjali Raza Kolb notes, Severance is about ‘race, waste, ennui, fevers, cults, suburbia and apocalypse’.16 But Severance is also very much about cities and New York City in particular. The interest in urban theory is signalled by Candace and her boyfriend’s courtship which happens over a copy of Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities. And the image of the empty city serves as an ekphrastic figure chronicled in Candace’s blog NY Ghost in which, as one of the last living non-fevered humans in New York City, she photo-documents the empty buildings, places, spaces, and icons: subway stops, the Flatiron Building, Times Square. Near the end of the novel, as the city becomes increasingly emptied and devoid of infrastructure, as the subways stop running, Candace takes a taxicab from her apartment in gentrified Bushwick across the iconic Brooklyn Bridge to her now empty office in Times Square. She strikes up a conversation with her ‘middle-aged Hispanic’ driver, both somewhat surprised that the other is still in New York City. When Candace directly asks why he chose to remain, he responds, ‘[N]ow that all the white people have finally left New York, you think I’m leaving?’ (261). What is often experienced as necessity, contingency, and exploitation, can at least momentarily be reclaimed as choice, or at least a moment of recognition. The city is basically unliveable, but for these two minority immigrants, there is a compensation. With the white majority gone, their experiences are no longer defined by the indignities of racism. The mutual recognition of the two minority characters suggests that they have a shared experience as immigrants or racialized persons. They find comfort in each other’s existence as they both identify as non-white. The presence of a white majority had left them marginalized, diminished their life chances, and rendered them invisible. For a moment, they can see and recognize each other after the majority white populations have either fled or been fevered. But their bonds are still tethered to whiteness since their only affiliation is as non-white, while their differences are further cemented by their class positions. Candace is constituted in and through the myth of the model minority while the cab driver belongs to the working class.

In Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, the fictional narrator HF, like Candace, stays in the fevered city even after many of its inhabitants have fled. It is not clear what impels him to stay—curiosity, individual will, God’s design (both Candace and HF practice the medieval art of sortes biblicae or bibliomancy where a reader opens a page and verse of the Bible at random and is guided by it)—but it provides him with an opportunity to observe the effects of the plague on the denizens of London. While he notices and describes the centrifugal flight of the rich (‘Those that had mony always fled farthest’), he is sympathetic to those that remained or were left behind. Even as he describes the emptying of the city (‘there would be no Body left behind’), he is acutely aware not only that the city is in fact still full of people, but that it is certain kinds of people, the poor, the vagrants, the disenfranchised and immiserated masses: ‘It must be confest, that tho’ the plague was chiefly among the poor; yet, were the Poor the most Venturous and Fearless of it, and went about their employment, with a sort of brutal Courage’.17 The flight of the rich is contrasted with the often strict restriction in movement experienced by the vast majority of London’s population. Houses suspected of harbouring plague were shut up, literally locked from the outside, and presided over by watchmen, day, and night. The shutting up of houses under quarantine was complemented by strictly enforced curfews and shelter in place orders. But alongside the roll calls of the dead, HF imbues the London poor with pathos and agency as they outwit their jailors and continue the essential work of city life. Ultimately as much a love letter to London as Severance is to New York, both pandemic fictions inscribe and then trouble the fiction of the empty pandemic city.

Severance is unique and relevant because it is both dystopic pandemic science fiction and a coming-of-age diaspora novel by an Asian American. It makes the link between emerging global pandemics and emerging immigrant identity formations explicit. Pandemics are often coded as threats to national identity from an Other. The Spanish Flu. The English Malady. The China Virus. The earliest response to pandemics has been the closing of borders and ports, followed by limitations on internal mobility. In America, hate crimes and violence against Asian Americans have noticeably increased since the beginning of the pandemic.18

Fig. 19 George Hirose, Protesters against Anti-Asian Hate, Union Square Park, March 21 (2021) © George Hirose. All rights reserved.

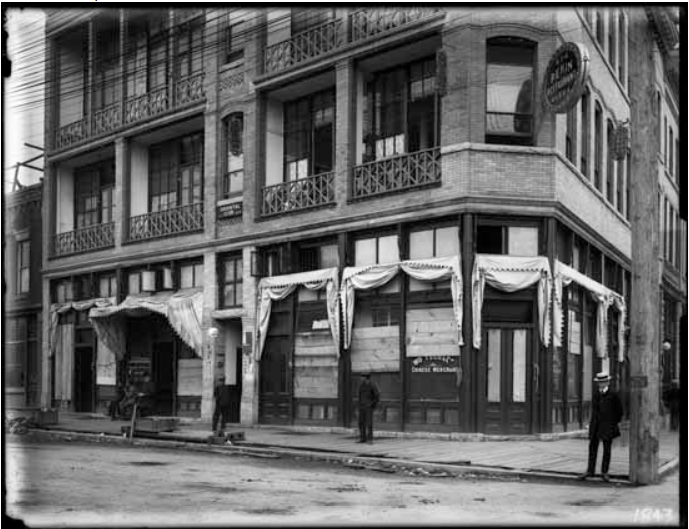

This follows pre-existing circuits of hate and racialization. From the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to the eugenicist Immigration act of 1924 which banned all immigration from Asia to the forced internment of Japanese Americans in camps during WWII, the United States periodically restricts immigration from Asia, while symbolically and juridically casting Asian Americans as internal foreign threats (‘the foreigner within’) against which society must be defended.

Fig. 20 Philip Timms Studio, Boarded-up businesses after race riots in Chinatown at northwest corner of Carrall Street at Pender (1907) © Courtesy of Philip Timms Studio/Vancouver Public Library/VPL 940.

In The Melancholy of Race, Anne Cheng explores the ambivalent psychodynamic process by which racial identity is formed in America through a study of art by Asian and African Americans. Cheng forcefully asserts that ‘[a]s both the targeted, racialized group in United States immigration policy and yet the least ‘coloured’ group, Asian Americans offer a charged site where American nationhood invests much of its contradictions, desires, and anxieties’.19 By specifically invoking the Freudian concept of melancholy, Cheng reconstitutes racial identity formation as radically ambivalent:

Racialization in America may be said to operate through the institutional process of producing a dominant, standard, white national ideal, which is sustained by the exclusion-yet-retention of racialized others. The national topography of centrality and marginality legitimizes itself by retroactively positing the racial other as always Other and lost to the heart of the nation. Legal exclusion naturalizes the more complicated ‘loss’ of the unassimilable racial other.20

Just as the melancholic subject constitutes its ego through the internalization of the lost object, racial identity is constituted as loss, exclusion, and incorporation. Asian Americans are both American and not American. But melancholy is constitutive of both subjects and objects. Dominant white identity is itself melancholic because it is caught in the bind of incorporation and rejection. This excluded presence haunts the American experiment. In Playing in the Dark, Toni Morrison argues that African American presence, the ghost in the machine, is the excluded centre of the American literary production. They are invisible by design. This canonical exclusion is a purposeful form of invisibility that is similar to the fiction of the empty pandemic city that I have been discussing. The inability to see allows for ongoing police brutality, the squalor of migrant camps and the continued marginalization of racial minorities.

While previous commentators on Freud have noted that there might not be a self without melancholy,21 I would suggest that there might not be an immigrant self without nostalgia. Melancholy and nostalgia are certainly related, and the title of Ma’s novel, Severance, is an example of the ‘vocabulary of grievance’ which allows Cheng to associate the legal work of grievance with the affective work of grief in identity formation. But nostalgia may be an even more important affect in immigrant racial identity formation than melancholy. Nostalgia derives from the Greek nostos (‘homecoming’) and algos (‘pain, grief’). In contemporary usage it most often refers to a wistful yearning for the past that has recently become even more abstract. But in its original formation, nostalgia was specifically a longing for a place (‘home’), and it was understood primarily as a medical condition: ‘severe homesickness considered a disease’.22 Initially applied in the context of war, nostalgia was often the purported cause of death for soldiers whose death had no immediate organic reference. Ma seems to have both ideas in mind as she works out the central role which nostalgia plays in her novel. Nostalgia is the most non-realistic element of Shen fever. It is a symptom and a cause of a mortal medical condition. As Candace notes after Ashley becomes fevered, ‘Don’t you think it’s strange Ashley became fevered in her childhood house? It’s like nostalgia had something to do with it’ (143). And a few pages later, the narrative voice becomes even more affirmative and didactic, ‘Shen Fever being a disease of remembering, the fevered are trapped indefinitely in their memories’ (160). The narrative transformation from subjective introspection to clinical objectivity is a feature that unsettles the reading experience, by manipulating the expected conventions of realism and the fiction of the psychologically whole and reliable narrator.23

Nostalgia is also central to the novel’s intertwined narrative, where it is the critical affect in immigrant racial identity formation. Candace’s parents’ flight from China is steeped in the tropes of immigrant literature: escape from an oppressive family and state structure, the desire for educational and economic opportunities for self and child, and the liberating conveniences of American life. But immigrant life is equally marked by the centripetal pull of the homeland: ‘My mother wanted to return to China’, Candace writes, ‘if not today then eventually’ (42). The competing pushes and pulls of nostalgia and assimilation situate the trope of immigrant identity in America. Nostalgia is a longing (perhaps in bad faith) to return home, but to a home that no longer (or perhaps never even) existed. The spatial logic of immigrant nostalgia is bad politics and bad history. Watching live footage of the Tiananmen Square protests on TV from their Salt Lake City basement apartment, surrounded by ‘tchotchkes that did not belong to them, that they did not know or understand within any cultural context and did not find beautiful’, Candace’s father says to his wife, ‘We are never going back’ (176). Nostalgia links the two anti-parallel narrative strands like base pairs in DNA, connecting its own historical life first as disease and now as affect. The novel actually reverses this history of nostalgia. Nostalgia is a disease that became an affect but in Severance, nostalgia is an affect that becomes a disease.

Candace’s approach to nostalgia and the past is to keep moving forward: ‘The past is a black hole, cut into the present day like a wound, and if you come too close, you can get sucked in. You have to keep moving’ (120). But you cannot escape a black hole. The double metaphor of black hole and wound serve to locate the past in physical space and in the body. The past as wound and as unescapable are explicitly linked to her immigrant identity formation. In her reconstruction, before she immigrated to America, as a young child in Fuzhou, she ‘seemed to lack all neurosis or anxiety’ (183). It was only after moving to America to be with her parents that she describes herself as ‘angry, chronically dissatisfied, bratty’ (184). Her tantrums lasted well into her teen years and are a way of expressing the body’s knowledge.

Personal meaning in the novel is revealed through time, through history, memory, and nostalgia, but it is also registered in terms of space, place, and geography. In Urban Underworlds, Thomas Heise explores the process by which immigrant and other marginalized communities and the geographies they inhabit become associated with miasma and disease as they are quarantined to the underworld in literature and space. He cites journalist Edgar Saltus’ view in 1905 from atop the newly built world’s first skyscraper, the Flatiron Building, also photo-chronicled by Candace for her blog. From up high, Saltus imagines a vision of frenzied capitalism ‘erupting gold’. But Saltus’ vertical vision grasps the uneven social, geographic, and racial space. Turning from the northern upper Fifth Avenue with its gods of industry, Saltus describes the southward Chinese quarter as a ‘sewer’.24 The North-South Modernist grid of the city seen from high above is coded as moral, economic, and racial hierarchy all at once. The view from a height both highlights and obscures the racial, economic, and colonial effects of capitalism on the new geography of the city. That paradox of perspective is also reflected in the glass-box architecture Candace works in and comes to inhabit. Candace’s contemporary New York City is a postmodern kaleidoscope where the ethnic ghettos of Brooklyn have gentrified and rebranded on a global scale. The vice districts and sexual cruising of Times Square seedy theatres and sex shops have been replaced by multi-national brands, made for Instagram neon signs and family entertainment (for upper-class tourists).

Candace’s New York office, which also becomes her home briefly, takes up the thirty-second and thirty-third floors of a Times Square building. And it is from this vantage that she initially describes the effects of the pandemic:

I looked out the windows. For the first time, I noticed that Times Square was completely deserted. There were no tourists, no street vendors, no patrol carts. There was no one. It was eerily quiet, as if it were Christmas morning. Had it become this way without my noticing? I walked around the perimeter of the office, trying to spot a fire truck or police car pulling up outside, trying to discern a siren in the distance, something. It wasn’t just the emptiness. In the absence of maintenance crews, vegetation was already taking over; the most prodigious were the fernlike ghetto palms, so-called because they exploded in prolific waves across urban areas, seemingly growing from concrete, on rooftops, parking lots, and all sidewalk cracks. (252)

We find here all of the traps and tropes of pandemic fictions. The emptying of people and the resurgence of prehistoric wildlife, as if the city were being swallowed up into its past. But height and distance create a false sense of emptiness and totality. Describing a view from a similar vantage point atop the 107th floor of the World Trade Center, the philosopher Michel de Certeau notes that the height falsely transforms the ‘extremes of defiance and poverty, the contrasts between races and styles’ into a unified surface. For de Certeau, the totalizing panoramic view erases difference and context, obscures life and ‘creates the fiction of knowledge’.25 Like the fiction of the empty city, this panoramic ‘fiction of knowledge’ is the result of optical transformations and desires. The empty city of pandemic fiction displaces cultural anxieties over immigration, changes in racial makeup, and altered standards of behaviour onto imagined contagion. It obscures real social and geographic deprivation. When Candace comes down from the heights and begins to document New York City, she not only falls in love with the ‘real’ city, she also begins to notice signs of human life. Like HF, Defoe’s fictional narrator, Candace chronicles places and the remaining people: a fruit vendor, an old lady in a nightgown, a homeless teen couple. But New York City is also home to a significant non-fevered population, Sentinel security guards: ‘The Institutions here were still being maintained, as if someone expected everyone to come back eventually. They were guarded by security guards […] The city had contracted Sentinel to protect public institutions from looters. Private owners also hired the company to guard evacuated homes’ (255). Even as the pandemic rages, the conjunction of capital and state power maintain the value of specific geographic spaces. Lights blazing without any tourists, and guards to protect when there are no threats. As Candace asks, ‘If a horse rides through Times Square, and no one is there to see it, did it actually happen?’ (253–54).

Race and racism are legislated and buttressed through a logic of spatial politics predicated on exclusion. Racialized bodies and identities are constituted through acts of immigration restriction that limit or block entry. But just as travel bans fail to prevent the spread of infectious disease in a globalized era, immigration restrictions only highlight the real permeability of borders. And like the ancient single cell organisms that became incorporated into other cells as mitochondria, the immigrant is always already the foreigner within. The racialized immigrant body is further distinguished by spatial limitations that confine them to specific neighbourhoods, ghettos and underworlds. But, as if that is not enough, in states of emergency and crisis, they are further relegated to the interstices of the visible. The trope of the empty city, both in pandemic fictions and fictions of the pandemic, inflicts psychological and physical harm on immigrant and minority bodies. During the pandemic, the fiction of the empty city supported an austerity reduction in city services that augmented the already disproportionate death toll in black and brown populations while alleviating the guilt of a dominant white majority that escaped the cities. Federal, state, and local governments contained the virus by allowing it to multiply and thrive in low resource settings amongst the most marginalized and vulnerable populations. Cordon sanitaire prevented the virus from getting out, but it also prevented the people from getting out or the healthcare workers from getting in. While literature can support and reflect these obfuscations, it can also lay bare the contradictions in the naturalized order of things. Severance engages with nostalgia as both a symptom of a global infectious disease and a process of racial formation, to question and highlight the spatial logic of exclusion and invisibility at the heart of the American Experiment. This novel works hard to make us see what hard work had made us not see.

Works Cited

Anne Cheng, The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation, and Hidden Grief (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Aristotle, Poetics, trans. by S. H. Butcher (New York: Cosimo Classics, 2008).

Associated Press, ‘More than 9,000 anti-Asian incidents since pandemic began’, POLITICO (12 August 2021), https://www.politico.com/news/2021/08/12/more-than-9-000-anti-asian-incidents-since-pandemic-began-504146

Balibar, Etienne, Masses, Classes, Ideas (London: Routledge, 1994).

Butler, Judith, The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1997).

Carrión, Daniel et al., ‘Neighborhood-level disparities and subway utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City’, Nature Communications, 12.3692 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24088-7

Cheng, Anne, The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation, and Hidden Grief (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Coates, Ta-Nehisi, ‘The Case for Reparations’, The Atlantic (15 June 2014), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

De Certeau, Michel, ‘Practices of Space’, in On Signs, ed. by Marshall Blonsky (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), pp. 325–38.

Defoe, Daniel, Journal of the Plague Year (New York: Norton, 1992).

Diamond, Elin, ‘The Violence of “We”: Politicizing Identification’, in Critical Theory and Performance, ed. by Janelle G. Reinelt and Joseph R. Roach (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992), pp. 390–98.

Du Bois, W.E.B., Black Reconstruction (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1935).

Du Bois, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction, trans. by Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage, 1990).

Foucault, Michel, Society Must Be Defended, trans. by David Macey (New York: Picador, 1997).

Handelman, Kali and Anjuli Raza Kolb, ‘Epidemic Empire: A Conversation with Anjuli Raza Kolb’, The Revealer (6 May 2020), https://therevealer.org/epidemic-empire-a-conversation-with-anjuli-raza-kolb/

Heise, Thomas, Urban Underworlds: A Geography of Twentieth-Century American Literature and Culture (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2011).

Ma, Ling, Severance (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018).

Matt, Susan, Homesickness: An American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Natali, Marcos Piason, ‘History and the Politics of Nostalgia’, Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, 5 (2004), 10–25, https://doi.org/10.17077/2168-569X.1113

Quealy, Kevin, ‘The Richest Neighborhoods Emptied Out Most as Coronavirus Hit New York City’, The New York Times (15 May 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/15/upshot/who-left-new-york-coronavirus.html

Rosenberg, Charles E., ‘What is an epidemic? AIDS in historical perspective’, Daedalus, 188. 2 (1989), 1–40.

Row, Jess, White Flights: Race, Fiction, and the American Imagination (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2019).

Sager, Stacey, ‘Coronavirus Update NYC: Neighborhoods hit hardest by COVID now buried under garbage’, ABC7 (15 September 2021), https://abc7ny.com/covid-garbage-hard-hit-nyc-neighborhoods-buried-by-trash-new-funding/11022921/

Shah, Nayan, Contagious Divides: Epidemic and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

Smith, Katherine F. et al., ‘Global rise in human infectious disease outbreaks’, Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 11.101 (2014), 1–6.

Spivack, Caroline, ‘Here’s how the coronavirus pandemic is affecting public transit’, Curbed (21 May 2020), https://ny.curbed.com/2020/3/24/21192454/coronavirus-nyc-transportation-subway-citi-bike-covid-19

Stoler, Ann Laura, Race and the Education of Desire: Foucault’s History of Sexuality and the Colonial Order of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995).

Wilkerson, Isabel, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010).

World Health Organization, ‘Global Health Estimates 2015: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2015’, World Health Organization (2016).

1 Zip code level data about covid death rates, infections and ambulance call volumes is available from the NYC Department of Health (https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page#maps); The New York Times and other mainstream media reported on the disparity between income, infection rate and urban flight, e.g. Kevin Quealy, ‘The Richest Neighborhoods Emptied Out Most as Coronavirus Hit New York City’, The New York Times (15 May 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/15/upshot/who-left-new-york-coronavirus.html. Carrión et al. developed a NYC zip code level index to demonstrate the association between neighborhood social disadvantage and rate of covid infections, and mortality in Spring 2020. See: Daniel Carrión et al., ‘Neighborhood-level disparities and subway utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City’, Nature Communications, 12.3692 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24088-7.

2 Editors’ note: This masking is also discussed by Pieter Vermeulen (chapter 9) in his study of elitist and racist fantasies of a depopulated Earth, typical of what he calls (after Brian Aldiss) ‘cosy catastrophe fictions’.

3 Daniel Defoe, Journal of the Plague Year (New York: Norton, 1992), p. 79.

4 Jess Row, White Flights: Race, Fiction, and the American Imagination (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2019), p. 105.

5 Stacey Sager, ‘Coronavirus Update NYC: Neighborhoods hit hardest by COVID now buried under garbage’, ABC7 (15 September 2021), https://abc7ny.com/covid-garbage-hard-hit-nyc-neighborhoods-buried-by-trash-new-funding/11022921/; Caroline Spivack, ‘Here’s how the coronavirus pandemic is affecting public transit’, Curbed (21 May 2020), https://ny.curbed.com/2020/3/24/21192454/coronavirus-nyc-transportation-subway-citi-bike-covid-19.

6 ‘It must be remembered that the white group of labourers, while they received a low wage, were compensated in part by a sort of public and psychological wage. They were given public deference and titles of courtesy because they were white. They were admitted freely with all classes of white people to public functions, public parks, and the best schools. The police were drawn from their ranks, and the courts, dependent on their votes, treated them with such leniency as to encourage lawlessness. Their vote selected public officials, and while this had small effect upon the economic situation, it had great effect upon their personal treatment and the deference shown them’. W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1935), pp. 700–01.

7 On 11 July 1951, a young black family, Henry Clark Jr., his wife Johnetta, and their two children, had to flee their new home in Cicero, a suburb of Chicago, on the very same day they moved in, because a mob of 4,000 white people stormed their apartment, destroyed their property and firebombed their building. Like other young black families, the Clarks had moved to a Northern city (Chicago) from the South (Mississippi). While this was one of the most egregious instances of Northern white hostility to the arrival of Black people during The Great Migration, it was one of countless examples. See: Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010).

8 Ta-Nehisi Coates, ‘The Case for Reparation’, The Atlantic (15 June 2014), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

9 Charles E. Rosenberg, ‘What is an epidemic? AIDS in historical perspective’, Daedalus, 188 (1989), 1–40 (pp. 1–17).

10 Aristotle, Poetics, trans. by S. H. Butcher (New York: Cosimo Classics, 2008), p. 20.

11 Global Health Estimates 2015: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2015, World Health Organization, section ‘Mortality data’ (2016); Katherine F. Smith et al., ‘Global rise in human infectious disease outbreaks’, Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 11.101 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.0950.

12 Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction, trans. by Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage, 1990), p. 137.

13 Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended, trans. by David Macey (New York: Picador, 1997), p. 257. For extended discussions of race and biopower, see: Ann Laura Stoler, Race and the Education of Desire: Foucault’s History of Sexuality and the Colonial Order of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995), and Etienne Balibar, Masses, Classes, Ideas (London: Routledge, 1994).

14 Foucault, Society, p. 258.

15 Ling Ma, Severance (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018), p. 62. Further quotations from the novel will be cited internally.

16 Kali Handelman and Anjuli Raza Kolb, ‘Epidemic Empire: A Conversation with Anjuli Raza Kolb’, The Revealer (6 May 2020), https://therevealer.org/epidemic-empire-a-conversation-with-anjuli-raza-kolb/.

17 Defoe, Journal, p. 75.

18 Associated Press, ‘More than 9,000 anti-Asian incidents since pandemic began’, POLITICO (12 August 2021), https://www.politico.com/news/2021/08/12/more-than-9-000-anti-asian-incidents-since-pandemic-began-504146.

19 Anne Cheng, The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation, and Hidden Grief (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 21.

20 Ibid., p. 10.

21 In their readings of ‘Mourning and Melancholia’, Judith Butler, Elin Diamond, and Anne Cheng have all suggested that melancholia, rather than being only a pathological later life formation, may actually be constitutive of the ego in early development. See: Judith Butler, The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1997); Elin Diamond, ‘The Violence of “We”: Politicizing Identification’, in Critical Theory and Performance, ed. by Janelle G. Reinelt and Joseph R. Roach (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992); Anne Cheng, The Melancholy of Race.

22 Marcos Piason Natali, ‘History and the Politics of Nostalgia’, Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, 5 (2004), pp. 10–25, https://doi.org/10.17077/2168-569X.1113. During the American Civil War, there were 74 deaths from nostalgia on the Union side, and more than 5,200 cases in the Surgeon General’s records. Susan Matt, Homesickness: An American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

23 One of my students, Junjie Ren, even suggested that the entire novel could be read as a retrospective account of Candace’s own fevered nostalgia as she, like the other characters, has fallen victim to Shen fever.

24 Quoted in Thomas Heise, Urban Underworlds: A Geography of Twentieth-Century American Literature and Culture (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2011), p. 2. Similarly, in Contagious Divides: Epidemic and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), Nayan Shah recounts how nineteenth-century public health officials described San Francisco’s Chinatown as a ‘“plague spot”, a “cesspool”, and the source of epidemic disease and physical ailments’, p. 1.

25 Michel de Certeau, ‘Practices of Space’, in On Signs, ed. by Marshall Blonsky (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), pp. 122–23.