8. Dead Gods and Geontopower: An Ecocritical Reading of Jeff Lemire’s Sweet Tooth1

© 2022 Kristin M. Ferebee, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0303.08

Let me begin with a proposition: Jeff Lemire’s 2009–2013 comic title Sweet Tooth, adapted by Netflix as a science fiction series that began airing in 2021, is a story about extractive resource exploitation. This claim will surprise those familiar with the comic, who know it as a post-apocalyptic narrative about the half-animal hybrid children who rise to found their own post-human world after a pandemic destroys human civilization and, simultaneously, a narrative about the journey across America undertaken by an ex-hockey bruiser, Jepperd, and a small half-deer boy named Gus. Indeed, very little that is even tangentially evocative of extractive industries appears in the first twenty-five issues of the comic, which conform to the post-apocalyptic fiction genre and to the genre of frontier captivity narrative popularized by American Westerns in which a vulnerable child must be returned to human civilization from the savage wilderness. The arc that begins in Sweet Tooth #26 does not overtly broach the topic of extraction, either. This arc, an historical flashback to an ill-fated Arctic voyage in 1911, presents the experiences of a surgeon who is traveling to a missionary settlement in what is now Alaska in search of his sister’s vanished fiancé, a man named Simpson. When the surgeon, Thacker, reaches the settlement, he finds all the missionaries dead of a plague save one, Simpson, who has been assimilated into a local Inuit community. Simpson relates an extraordinary tale of how, venturing into a passage deep below the ice one day, he trespassed upon the skeletal animal-human bodies of what he later learned were Inuit gods. He explains that a shaman told him that this place was where the gods rested after their earthly bodies died—that ‘their spirits remained free, but their bodies would rest there until they returned one day’.2 There are two consequences of Simpson disturbing the tomb of the hunting god Tekkeitsertok:3 viral sickness wipes out the mission, and Simpson’s Inuit wife gives birth to a deer-human hybrid son whom Simpson believes to be an incarnation of Tekkeitsertok ‘come to reclaim this land’.4 However, the repulsed Thacker massacres the entire Inuit community before perishing of the sickness alongside all of his shipmates, still locked in the ice.

The exact relationship of this historical anecdote to the central narrative of the comic is not entirely transparent. It is clear, based on later scenes, that Thacker’s journal (containing the account of his search for Simpson) has been recovered from the icebound wreck of his ship, and that this either led to or occurred contemporaneously with the rediscovery of the passage below the ice by American scientists who attempted to clone a living creature (Gus) from the bones of Tekkeitsertok’s ‘earthly body’. Their violation of the Inuit sacred space and of the gods’ dead bodies caused the pandemic that ravaged the world and triggered the birth of the hybrid children, some of whom are reborn gods. Further detail is never offered, nor is there an attempt to explain how the Inuit beliefs described in Thacker’s journal might ‘translate’ to Western understanding in an acceptable way.

Here, I argue that the Sweet Tooth’s refusal to suture Inuit ontology to Western ontology by providing ‘reasonable’ answers to these questions situates the comic within the collapse of what anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli has termed geontopower: the ongoing effort on the part of settler capitalism to maintain essential boundaries between Life and Nonlife and regulate who or what is considered capable of ‘being’. At the same time, Sweet Tooth tries to productively imagine ways and scales of biological and quasi-biological being that geontopower has largely worked to invisibilize, utilizing the technics of narrative to engage the reader in new knowledge-practices that chart a course out of the fly-bottle of the Anthropocene age.

The term ‘fossil fuel’ is a moderately accurate evocation of the source from which such resources come. Though natural gas and crude oil may not be derived from the corpses of dinosaurs, as both the popular imaginary and Timothy Morton (in his evocation of ‘liquefied dinosaur bones burst[ing] into flame’) suggest, they are created by the decomposition of plants and organisms over millennia.5 In other words: petroleum is the remains of the nonhuman dead. This element of the carbon imaginary is rarely emphasized in ecocritical accounts, which tend to focus on the impact and imagined futures of petroleum products—as Kathryn Yusoff puts it, the ‘future fossilization of humanity’ or the ‘human-as-fossil-to-come’.6 Even where Yusoff suggests that the slogan ‘Welcome to the Anthropocene!’ might be replaced with ‘The Carboniferous Lives Again!’,7 she opts not to engage with the notion of fossil fuels as possessed of a history and (arguably) a life cycle. Amanda Boetzkes and Andrew Pendakis describe oil as ‘time materialized by sediment’ and as ‘the energy made possible by eons of fossilized death’,8 but choose not to treat the organic life that underlies this death.

Boetzkes and Pendakis also describe oil as ‘an oddly feral god’, and Sweet Tooth literalizes this description in its representation of dead ancient animal gods whose corpses—buried beneath the Arctic ice—are ‘extracted’ as resources by modern technology. The mythology that is mobilized in Sweet Tooth reads these corpses as simultaneously non-living things (the skeletons that first Simpson and later the scientists disturb) and as merely one non-living aspect (the dead ‘earthly bodies’) of beings that are capable of what Povinelli calls ‘chang[ing] states’.9 These are dead bodies whose deadness does not divorce them from their relationship to the living world, but is rather part of a larger being-ness that constitutes the intentional ‘thing’ that is a god. Povinelli analyses how rock and mineral formations, in indigenous Australian ontology, possess such an intentionality. This is an intentionality that allows them to ‘intend, desire, [and] seek’10—in the titular examples that Povinelli gives,11 to listen or die—as part of an identity as durlg or type of Dreaming that is capable of, among other things, engendering human life through a conception that is both nonbiological (in that it is separate from human biological conception) and material (in that it is related to an understanding of shared biological material—in the example that Povinelli discusses, sweat).12 This ontology points towards a profoundly different ‘slicing’ of the world than that practiced by settler capitalism, as Povinelli details—not into human and nonhuman, or into life and nonlife, but rather into affiliations of being and kinship that do not differentiate on these bases. (That this categorization dissolves the problems associated with the ontological status of a virus, which we struggle to characterize as alive or dead, seems evocative in the context of Sweet Tooth’s plague.)

Tekkeitsertok and his fellow Inuit gods emerge, when viewed through the possibility of such alternative ontologies, as the type of bodies that literary theorist Monique Allewaert has described as ‘disaggregated’ or ‘decomposed’: ‘pulled into parts’ in a way that does not ‘vanish’ the bodies or beings in question, but rather changes them into another state. Allewaert suggests that at the centre of disaggregate being is relation, which ‘describes an enmeshment that is not a merging and that forecloses the possibility of exchange’.13 In the titular example of Allewaert’s Ariel’s Ecology, the Shakespearean spirit Ariel describes a drowned traveller as transformed into coral and pearl through a ‘sea-change’ that, Allewaert argues, pulls the body ‘into parts’ and renders it ecological, yet preserves ‘the apparently paradoxical possibility that the personhood is not vanished by the disaggregation but instead changed’.14 Applying this model, we might see that the skeleton in the underground cavern that Simpson discovers is a part that exists in a certain relation to the living body of the hybrid Inuit infant whom Thacker murders, both of which exist in a relation to the living body of Gus that we might call ‘Tekkeitsertok’. Thus, when Gus is close to death in Sweet Tooth #25 and a vision of Tekkeitsertok appears to him and guides him to the slaughtered Inuit village where the hybrid child and its mother lie dead, Tekkeitsertok is revealing himself to himself: awakening Gus to the relationality that characterizes his/their own being. This is significant because at no other point in the narrative or its world is there any contact between Gus and the slaughtered Inuit. Indeed, Thacker’s narrative, confined within its hundred-year-old journal, is isolated from the comic’s central storyline. The Thacker narrative unfolds over three issues of Sweet Tooth (#26–28) and makes a central appearance in another (#17), meaning that it constitutes a full tenth of the comic—yet it exists almost entirely in parallel with the narrative present of the twenty-first-century pandemic, an enmeshment of the type (never quite separate or quite merging) that Allewaert describes. Simpson and Thacker’s violation of the Inuit gods does not seem to cause the pandemic, nor does it solve the pandemic; it barely even explains the pandemic through its thirdhand account of Inuit lore. Only the presence of this journal in the hands of a scientist at the remote Alaskan base that extracted the gods’ skeletons, which the half-mad doctor Singh discovers, gestures towards any place where these two narratives diegetically intersect. The Tekkeitsertok relation, however, offers a schema according to which we can understand the two story ‘parts’ as related.

This emphasis on partedness (a condition of being part of a larger whole yet also parted from in a way that implies independent wholeness) seems congruent with a reading of the gods as a form of extractive resource. Extractive resources occupy several simultaneous scales: they are microscopic and macroscopic in ways that draw attention to them as always already incomplete and that act to obscure meaningful perception of their substance. After all, oil may be an ‘oddly feral god’, but it is rarely imagined as such. As Amitav Ghosh famously points out in an early treatment of ‘petrofiction’, oil is scarcely imagined at all. Ghosh suggests a number of reasons why this might be the case: oil is aesthetically unpleasant (it looks and smells bad). At the time when Ghosh was writing (1992), oil ‘reek[ed] of unavoidable overseas entanglements’; it ‘smell[ed] of pollution of environmental hazards’.15 Even now, when scholars seek to visualize oil, they most often do so in terms of oil-as-infrastructure and oil-as-pollution. The collection Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture (2017) contains twenty-two chapters examining aspects of the titular petrocultures, from plastics to automobiles to cosmetics to dead ducks to the Gulf War. Appel, Mason, and Watts suggest that oil functions as a metonym for other forces—‘authoritarianism, corruption, violence, misallocation of money’16—but their point is obscured by the extent to which oil itself is never quite what is being discussed. Indeed, Jenny Kerber assumes their intent is to suggest that ‘the difficulty of grasping “oil” writ large means that we often turn to stand-ins’.17 When we imagine oil, we do not imagine oil. We imagine the thing that oil is inside, the thing that oil has made, the thing that oil has ruined, failing to apprehend it as part or partial being.

All of this seems to define what Timothy Morton has termed a ‘hyperobject’: so ‘massively distributed’ across spacetime relative to human existence that it cannot be completely or directly perceived. Morton’s notion of hyperobjects as being massive relative to human existence, however, overlooks the possibility that the problems associated with such objects also accrue to objects that are hypo: in other words, massively small. Furthermore, Morton spends little time dwelling on the fact that many of the phenomena he classifies as hyperobjects are actually at once massively large and massively small—most notably all of the examples involving radiation (Chernobyl, Fukushima, the Trinity test), and arguably those involving weather as well. In the same way, these phenomena distort our conception of time. They are extremely long-lasting, but also inconceivably instant (vide the discrepancy between the lightning-quick timescale of radioactive exposure and the long half-lives of radioactive isotopes); they are also often simultaneously past and future. Astrid Schrader has explored the characterization of the microscopic as evolutionarily primitive and inherently prior to complex life,18 while macroscopic complexity is often associated with modernity or with advancing futures, yet both orders or structures of life are invoked in hyperobjects such as oil. Clearly the central obstacle presented by these phenomena is not that they are spatiotemporally massive, since they are also spatiotemporally miniscule, or even that they exist on a nonhuman scale (since they exist on more than one scale). I suggest that the obstacle is that we struggle to attribute meaningful being to objects that we perceive as ‘parted’—that is to say, either: 1) parts of other objects or, 2) made up of parts in a way that does not form a coherent unity.

In my analysis of plural subjectivity in science fiction,19 I have discussed the threat that partedness poses to the human fantasy of bodily completeness and coherence—in short, the microscopic threatens to remind us of the microscopic scale at which ‘we’ dissolve into vital systems, organs, and microorganisms (what Stefan Helmreich describes as Homo microbis, ‘the microbial human’),20 while the macroscopic threatens to remind us that we, too, are only parts of material systems that exist at a macroscopic scale. Schrader suggests that ‘[e]mpathy requires the unity of an “I”’ and that identification with the Other must begin with ‘auto-affection, the becoming-present to self’,21 rendering parted beings outside of the possibility of compassion insofar as they not only lack a unified self that can be identified with, but also trouble the plausibility of a unified ‘I’ from which the human can identify and therefore empathize.22 This is particularly significant insofar as the most common human engagement with both the microscopic and the macroscopic takes the form of inter-assimilation of human and machine parts—the usage of cameras, telescopes, microscopes, etcetera, in a way that Helmreich has described as becoming ‘part of a compound eye’.23

There are obvious implications in this compound or ‘parted eye’ for responsibility in the practical sense that Karen Barad describes: the ‘ability to respond to the other’ that they argue ‘cannot be restricted to human-human encounters’,24 but that is often restricted to a certain subdivision of Life—the subdivision that is possessed of a soul, or, as Povinelli picks out of science studies and the Aristotelian tradition, the ‘carbon-based metabolism [that] provides the inner vitality (potentiality) that defines Life as absolutely separate from Nonlife’.25 Barad asserts that this responsibility/response-ability is ‘“the essential, primary and fundamental mode” of objectivity as well as subjectivity’, but acknowledges the difficulty inherent in a situation where ‘the “face” of the other that is “looking” back at me is all eyes, or has no eyes, or is otherwise unrecognizable in human terms’26—a point that they explore in more depth through their study of the ‘all eyes’ brittlestar that dwells on the sea bottom.27 However, the brittlestar, as an animate creature, is relatively recognizable as responsive in human terms in comparison to Povinelli’s rock formations, and both examples escape the problems caused by the being that cannot be seen except by the compound, parted eye that disallows any fantasy of the human as other-than-assemblage. Barad addresses this issue in their discussion of Ian Hacking’s account of microscopic ‘seeing’, writing that what the use of microscopes permits is not a practice of seeing so much as it is a practice of bringing-into-being certain kinds of phenomena that we are prone to calling ‘objects’.28 Of course, the assemblage human-plus-microscope is not inherently different from the assemblage human, which also operates to bring-into-being certain kinds of phenomena (sensory perceptions/organizations of the world) in certain ways—and it is this destabilizing fact that we must reckon with when our consideration of the compound eye brings it to the fore.

Barad suggests that Hacking’s failure lies in his inability to resist ‘one of representationalism’s fundamental metaphysical assumptions: the view that the world is composed of individual entities with separately determinate properties’.29 Rather than emphasize the individuality or separateness in this assumption, as I would argue Barad does, I wish to critique the implicit wholeness of the ‘entity’ to which Barad refers. In their mobilization of Niels Bohr’s quantum philosophy, Barad writes of a ‘wholeness’ that Bohr attributes to phenomena marked by their inseparability, a wholeness that is made possible in their philosophy by an experimental arrangement that performs a ‘cut’. Though Barad understands this wholeness as always contingent, it nevertheless seems like one of the less developed parts of their work. Further development would perhaps require our contemplation of what the relationship is between the inseparable inner workings of the phenomena and everything that is excluded from it, which we might also frame as the relationship between the actual (or the actualized) and the potential (all other actualizations that are possible). Take, for instance, the case of oil: how can a study of petroleum-based plastics take these objects not merely as symptomatic of or stand-ins for (that is, parts of) the larger oil phenomenon, while also acknowledging their relatedness to microorganisms that lived and died and were compressed into petroleum? How can the lives of those microorganisms be attended to as lives qua lives, while they are simultaneously viewed as part of an oil ‘thing’ that encompasses dead ducks and smog over Los Angeles? If, as Schrader notes, much philosophical development of empathy for the nonhuman takes mortality and its corollary experience of vulnerability to be its basis,30 and even the ‘hetero-affection’ of her proposed human-nonhuman intimacy ‘inscribes mortality within life’, then how, in the case of the microorganisms who have become oil, can we share the experience of mortal vulnerability with something that is already dead? Even further: if we understand mortality, in a less material sense, to refer to a cessation of being-as-something, and argue therefore that it is possible for certain rock formations and certain creeks to be mortal through their vulnerability to being transformed into some other kind of thing, then the microorganisms at the base of oil have already undergone such a transformation and constantly threaten to undergo another. How can we feel compassion for these things and, thereby, be moved to respond to and be responsible for them in the ways that seem so necessary in the Anthropocene?

Something about oil, in its ooziness and its infiltration, its microscopic (ci devant organic) and macroscopic (infrastructural, Anthropocene) qualities, its already-deadness and its not-yet-aliveness (its potential to fuel or be made into things) frustrates any effort to understand it as a thing that deserves empathy, or even to understand it as an oil thing. So how can we reach towards the actualization of the oil thing without making the mistake of thinking that by doing so we will somehow grasp a whole (unparted) object in a way that will force it to cohere and thereby yield itself as visible—knowable—to our eyes?

It has become a trope of Anthropocene scholarship to note the destructive effects wrought by new forms of knowledge production birthed in the Enlightenment era—an era ‘shaped by human beings’ preoccupation’, Allewaert writes, ‘with uncovering, mapping, measuring, and (in most cases) instrumentalizing the natural world’.31 Jason Moore describes these forms of knowledge-production as ‘premised on a new quantitativism whose motto was: reduce reality to what can be counted, and then “count the quanta”’.32 This epistemological practice is premised on a Cartesian dualism in which an ‘objective’ subject (the counter) who is, to reverse engineer Donna Haraway’s words, ‘disengaged’ and ‘from everywhere and so nowhere… free from interpretation, from being represented […] fully self-contained [and] fully formalizable’,33 counts the quanta of an ‘individually determinate entit[y] with inherent properties’,34 wholly external and therefore capable of being anatomized. Moore suggests that this conception of the object as entirely external works to render objects better capable of being ‘subordinated and rationalized, [their] bounty extracted, in service to capital and empire’.35 In other words, the concept of the individual discrete object as something separate from the subject-observer is at the heart of settler-capitalist world-ecology.

Crucially, Sweet Tooth frames its colonial history in terms of this knowledge-production. The three-issue arc in which Thacker’s narrative is related is entitled ‘The Taxidermist’, and a large panel early in #26 (Fig. 21) reveals that the titular taxidermist is Thacker himself, who occupies himself with taxidermy on the long sea voyage to the Arctic.

Fig. 21 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #26 (2011) © Jeff Lemire and Vertigo Comics. All rights reserved.

He is, he writes, ‘a seasoned naturalist’, whose ‘hunger for adventure’ and eagerness to catalogue ‘exciting new species’ motivates his journey as much as the need to find his lost brother-in-law. A panel depicts Thacker’s tool stitching the pieces of a preserved bird together; the next reveals the ship’s cabin that he has filled with other such birds and fish. Lemire’s choice to title the arc after this single activity, which is never again seen or mentioned, suggests his awareness that it speaks to some larger theme of the episode, and indeed the comic as a whole. Certainly, a parallel exists between the fragmented, reassembled bodies of the animals that Thacker preserves and the skeletal remains of the Inuit gods’ earthly bodies, even leaving aside the ways in which the disturbance and extraction of the latter evokes controversies surrounding the colonial-scientific misappropriation of indigenous remains. Where indigenous cultural prohibition forbids the disturbance of the gods’ bodies while the gods are ‘resting’, in spite of the fact that these bodies are dead, Thacker’s taxidermy speaks to a belief that animal bodies are fundamentally divorced from any former or future being—that they can be disassembled and rearranged according to his whim without any effect on other beings. Defining Thacker as ‘taxidermist’ centers this belief as his primary characteristic and positions his anatomization and reconstruction of animal bodies as representative of a larger onto-epistemology in which his deft hand with a needle sewing up fur and feathers does not really count as a touch; or rather in which a touch does not engineer a relation between two beings. This is an ‘unsticky’ world where division upon division can be smoothly and unproblematically enacted or unenacted: a cell from an organ, an organ from a body, a body from its environment. It is a quality that is mirrored in the work of Sweet Tooth’s modern-day scientists, who indifferently dissect hybrid children in their quest for a plague cure—a resemblance that is highlighted by Lemire’s cover art for the comic, which features, in #5, Gus’ head mounted like a taxidermized hunting trophy and, in #8, his body preserved in a giant specimen jar.

To say that Thacker is the titular taxidermist is not to overlook the extent to which Louis Simpson also plays this role in the story. Simpson is superficially the less sinister of the two characters—a missionary who finds himself ‘more and more enamored with [Inuit] ways’ and comes to consider the Inuit ‘so much more enlightened than [colonizers] are’.36 Abandoning his mission, he marries into an Inuit community and happily adopts their ways. Yet his willingness to ignore his own instinct of boundaries and prohibitions—‘Deep down I knew I wasn’t meant to be here’, he narrates, ‘I knew that as much as I’d come to be accepted by these people, I was still an outsider’37—suggests the extent to which his ‘going native’ is part of a tradition whose basis reinscribes white male agency. Sara Ahmed has detailed how fantasies of becoming-other (and particularly, as in her reading of Dances with Wolves, becoming-indigenous) are enabled by a white male ability to make and unmake boundaries at will: ‘the border between self and other, between natives and strangers’.38 Moreover, Ahmed connects these fantasies to epistemology: ‘the Western subject can have the difference and thus knows the difference’.39 Knowledge here indicates an occupation that is also assimilation, or vice versa—a type of mastery that hearkens to Wittgenstein’s questions regarding the nature of the connection between ‘knowing’ and ‘knowing-how-to-go-on’.40 Colonial knowledge practices elide the gap between these two zones, collapsing description and agency. The agency that Ahmed attributes to becoming, which she diagnoses as the ‘ability to transform oneself’, is of a piece with the capacity to anatomize, and therefore ‘master’, the natural world. Simpson’s perception of himself as the super-agential knower who can touch the other without being touched by it (becoming and unbecoming the other as convenient) is akin to that of Thacker: the taxidermist. (It is also relevant that the two characters are said to have met in medical school.)

It is simple enough to read Simpson’s crime, in this way, as one of incorrect relation—he did not behave towards the gods in the way that is correct. Yet, I want to press harder on this point. Simpson more specifically recounts the Inuit shaman as saying that the plague was ‘the price of [his] betrayal. Mankind’s price for disturbing the gods’. The syntactical apposition of ‘betrayal’ and ‘disturbing the gods’ suggests an equation: Simpson’s crime is not violation of religious prohibitions, nor transgression into a sacred space, but his ‘disturbance’ of the bones in the cave, which are dead/inanimate and yet characterized by a form of being that is capable of being disturbed. I emphasize this in part because Povinelli41 has compellingly explored how often indigenous tradition is enjoyed as an authentic difference until it offers substantial challenge to universalized liberal settler beliefs—humoured according to the ‘profound asymmetry’ that Wendy Brown notes as characterizing the ‘culturalization of politics’, wherein ‘liberalism’s conceit about the universality of its basic principles’ demands that these principles and the culture of which they are representatives be perceived as not-culture, and liberalism therefore as cultureless.42 An indigenous belief that a certain cavern is sacred, or that specific kinds of behaviour are forbidden within that cavern, might be enjoyed as harmlessly cultural; however, Simpson’s actions are not described in terms of belief or culture. The Inuit, indeed, are absent from this issue, which is about what Simpson has done to the gods. What we are asked to accept is not a belief that Simpson has done something, but rather the more challenging assertion that he has—and that his actions are mirrored by the extractive efforts of scientists in our own era.

When the twenty-first-century Dr. Singh arrives in the cavern of the gods, which has been transformed into a scientific laboratory, he discovers that the dead gods are still present, and they are still dead: their bones lie, exposed to the air, on slabs. Broken industrial incubation tanks mark where DNA was extracted from the bones and used to create new clones of the gods. Where Gus was successfully ‘born’ from his tank and raised by a runaway janitor (the only survivor when the plague swept through Fort Smith) the other new gods were left to smash their way out and become feral animal-children. Singh encounters these feral gods in a scene that sees him surrounded by the gods as both dead and living bodies: two different materializations of the same source. The simultaneous visibility of these materializations draws attention to their relation, foregrounding not only the historicity and potentiality of the separate-yet-inseparable Tekkeitsertok parts, but also the very real impact that disturbance of the one can have upon the other. Though the ancient bones may be inanimate, they are not inert insofar as, for example, Tekkeitsertok’s bones participate in a meaningful and ongoing lineage of Tekkeitsertok relation that connects Gus to the slaughtered Inuit and beyond them to the dead bodies of the gods. The Inuit manner of describing this—that the bodies ‘rest’ while waiting for the gods to return—emphasizes the characterization of earlier material incarnations as dissolved-but-involved, dead-yet-responsive, past in a way that does not dissolve obligations on either side of the encounter. The disturbance of the gods, in this sense, manifests as an intrusion into this lineage: a disruption of the process of becoming, and one for which no acknowledgement is given or responsibility taken. This is not dissimilar to the intrusion into and disruption of indigenous cultures that colonialism causes, another parallel highlighted by the relationality of Thacker’s and Gus’ tales.

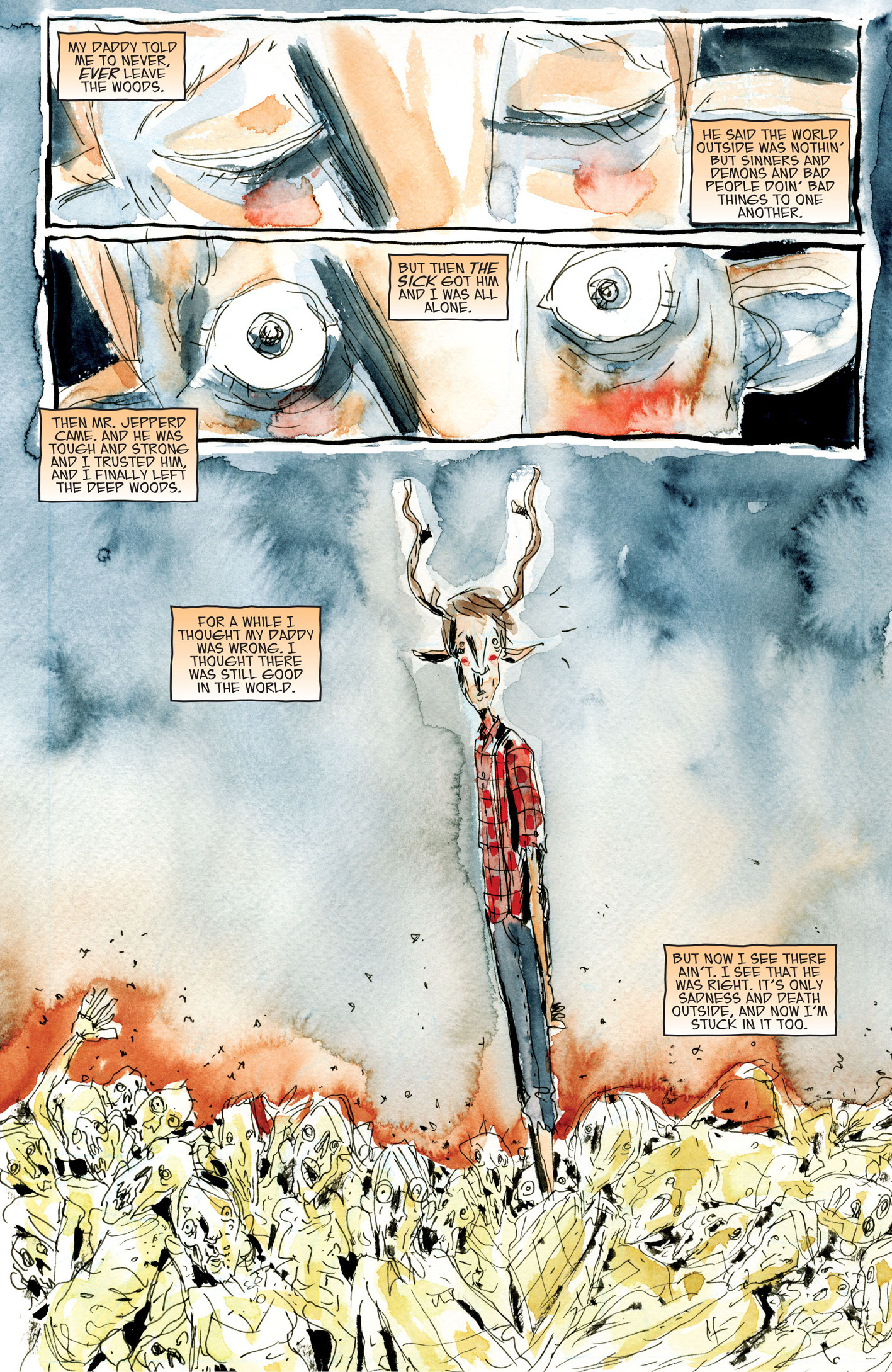

This resonance between human and nonhuman histories43 is heightened by the comic’s use of several panels (and one piece of cover art) in which Gus is pictured against a backdrop or atop a pile of dead human bodies (Fig. 22).

Fig. 22 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #36 (2012) © Jeff Lemire and Vertigo Comics. All rights reserved.

These bodies are not literally present, but represent the millions of humans who have died of the ‘Sick’ in the course of Gus/Tekkeitsertok’s inadvertent ‘cleansing’ of the world. The bodies, unindividuated and compressed into the ground, might suggest the victims of colonialism on top of whom much of modern civilization has been constructed — or, equally, the masses of microscopic dead whose bodies have literally fuelled that same civilization. Meanwhile, the images, with their striking juxtaposition of childhood innocence and mass death, also confront the reader with the question of what the exact relation is between Gus and these dead. After all, the plague is entwined with Tekkeitsertok-being: described, in the ‘taxidermist’ interlude, as the ‘breath’ of Louis Simpson’s hybrid son, and in its modern incarnation as something to which hybrid children are immune at a genetic level. (‘Something fucked-up in yer DNA’, Jepperd tells Gus.44) In #37, Dr. Singh insists that Gus was ‘the carrier’ of the plague, ‘sent to kill all of us’, and Gus seems to accept this idea, later repeating to his pig-girl friend, Wendy, that he ‘carried the Sick, and whatever it was that made all the hybrids, in [him]’, and that he ‘killed everyone. [He] killed [his] daddy and [hers]’.45 Even Jepperd, Gus’ father-figure, admits that Gus’ creation probably did cause the plague.46

Yet Jepperd, Wendy, and their human ally Becky are also reluctant to attribute culpability to Gus, perhaps not only because Gus is a child, but it is, on the face of it, absurd to view Gus as responsible for a phenomenon that he is only one part of. In the face of their inability to assign blame and, correlatively, agency in this context, these characters instead repeatedly assert the impossibility of any objective answers to the conundrum. Becky at first shifts responsibility to humans, before saying that she simply ‘can’t believe’ that God sent Gus to kill people;47 Jepperd renounces quantitativism, telling Gus, ‘Truth is we ain’t ever gonna understand how it happened… what the hell they were doing here in the lab… none of it. There is no big secret. At least not one that you or I or Singh or your daddy are ever going to be able to explain’.48 Perhaps most interestingly, Sweet Tooth’s villain, the psychopathic Abbot, is left crazed by his inability to pry forth the answers from any text—notably from the flesh of hybrid bodies, written in the code of their ‘fucked-up’ DNA. ‘What did Singh find?’ Abbot demands when he reaches the Alaskan cavern. ‘Where did the boy come from? The plague?’ Singh has already told him, however: ‘There are no answers. At least not the ones you want’.49 And, ultimately, Abbot is slain by Gus himself: the vexation of all of these questions made flesh insofar as he both is Tekkeitsertok and is not Tekkeitsertok, is not all Tekkeitsertok and is not all of Tekkeitsertok: a paradox of agency and wholeness that can find no resolution in the text.

It is easy to say that this paradox offers a critique of settler capitalist knowledge practices and their inability to encompass certain kinds of problems, and to argue that this is why the text itself mirrors the partedness it takes as topic. The metaconundrum of the relation between the Thacker and Gus parts of the narrative thus reflects the conundrum of the relation between Gus, the Sick, the dead bones of the gods, and the Inuit child: a problem of understanding the relation between parts. Yet, as I have previously referenced, critiques of settler capitalist knowledge practice are not novel—they are a trope of Anthropocene scholarship. What distinguishes the critique that Sweet Tooth offers is the ways in which its focalization through (principally) the character of Gus highlights a very specific problem that we are confronted with when we utilize our current knowledge practices to perceive the hypo-/hyperphenomena that are defined by what I have termed their ‘partedness’. I have discussed the simultaneously macro- and micro- qualities of such objects, and the temporal distortions that render them simultaneously past and future, instantaneous and prolonged. Missing from this discussion, however, is attention to the question of why oil seems absent from our conversations about oil. In other words: between microscopic and macroscopic, between past and future, there ought surely to be a here-now of parted objects that never seems to appear. It is precisely when we try to fix our gaze on such a thing that it recedes into very small or very large spatiotemporal scales—becoming particulate or massively made up of parts. When we work to ‘bring into focus’ (gesturing back towards Hacking’s work on microscopy) the thing itself, we cannot bring a thing into focus at our own scale. We are confronted by an absence that, often, we take as an essential characteristic, a quality of weirdness that defines (in the case of Morton) a special quality of object, or that, at the very least, becomes constitutive of a quasi-horror that births what Gry Ulstein describes as ‘Anthropocene monsters’, situated in a spatiotemporal landscape (the Anthropocene) that is distinguished by ‘disorientation and chaos[,] overwhelming confusion and terrifying realizations’.50 Perhaps it is no surprise that this ‘New Weird’ would so often be identified as or with a kind of horror, when the absent presence of the thing functions as a kind of specter in the Derridean sense, agential in spite of its displacement in both space and time.

In fact, the specific genre in which Sweet Tooth most clearly participates is a kind of Arctic horror that clearly works in the sense Ulstein51 suggests, as a metaphor for ecological issues. This genre addresses itself to the hyper-systems of resource extraction and climate change, focusing on the massive, world-destroying horrors that might be birthed from such systems, while simultaneously materializing these horrors as microscopically viral or parasitic. The 2015–2018 TV series Fortitude, for example, builds its central horror on the premise that an ancient parasite might be preserved in thawing permafrost, capitalizing on a popular news narrative that has spawned headlines about possible ‘frankenviruses’52 or ‘zombie viruses’,53 reanimated after millennia, emerging due to anthropogenic global warming. Sweet Tooth’s virus, released from beneath the Alaskan ice, clearly echoes these fears of the alien agent that is both too small and too large for us to engage with directly, too ancient and yet too futural (in its ability to define a coming apocalypse). Like Fortitude, Sweet Tooth also builds on media narratives about the emergence of animal bones and mummies from permafrost, themselves now a precious resource that ‘prospectors’ in the tundra extract.54 These bones, parasites, viruses, oil, and rare earth minerals all emerge from the Arctic as haunting parts of a spectral whole that we cannot visibilize but sense must be there. The absence of this projected whole impels us to treat all of these parted objects as, well, parts: partial beings to which we need not attribute the kind of responsiveness that is characteristic of a whole being, though we trouble ourselves with supernatural visions of how this hallucinatory whole being, the Anthropocene monster, might respond were it to awaken.

Our failure to engage with parted objects on their own terms is evident in the kind of language we use for them. Ulstein notes how prominent Anthropocene theorists use language to describe the Anthropocene and its parts that is ‘strikingly horror-evocative and apocalyptic’, marked by evocations of ‘malevolence’, ‘trauma’, ‘annihilations’, ‘intrusion’, and ‘terrors’.55 Within the realm of petrohumanities, the language used to specifically describe oil is no more neutral: oil is ‘dirty’, ‘toxic’; in the words of Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso, ‘the devil’s excrement’. Scholars, as much as anyone, fall prey to this embedded moralizing: ‘To unveil mounds of petrochemical debris and the fungus of derricks everywhere’, Georgiana Banita writes,

is akin to an autopsy on a body whose death, we are made to feel, could have been avoided. The images convey a surgical violence in their attention to malignant sprawl… The film of oil mingled with the earth’s surface has the unfinished, un-chewed quality of something our bodies secretly consume or excrete.56

Stephanie LeMenager suggests that something of this expressive revulsion may result from the fact that oil’s ‘biophysical properties have caused it to be associated with the comic “lower bodily stratum”’.57 Andrew Pendakis argues that oil is ‘arguably the dirtiest of liquids […] not just on the level of its (highly racialized) material properties (its blackness, its stickiness, its opacity, etc.), but on the terrain of its social and political usage’.58 This discourse seems to subsume oil itself within a dread of the objects that it is read as part of—appalled and revolted by these beings in a way that denies and forecloses their potential to have been and to become other things, the very quality that Povinelli identifies (rejecting the alternative of ‘vitality’) as intrinsic to being itself.

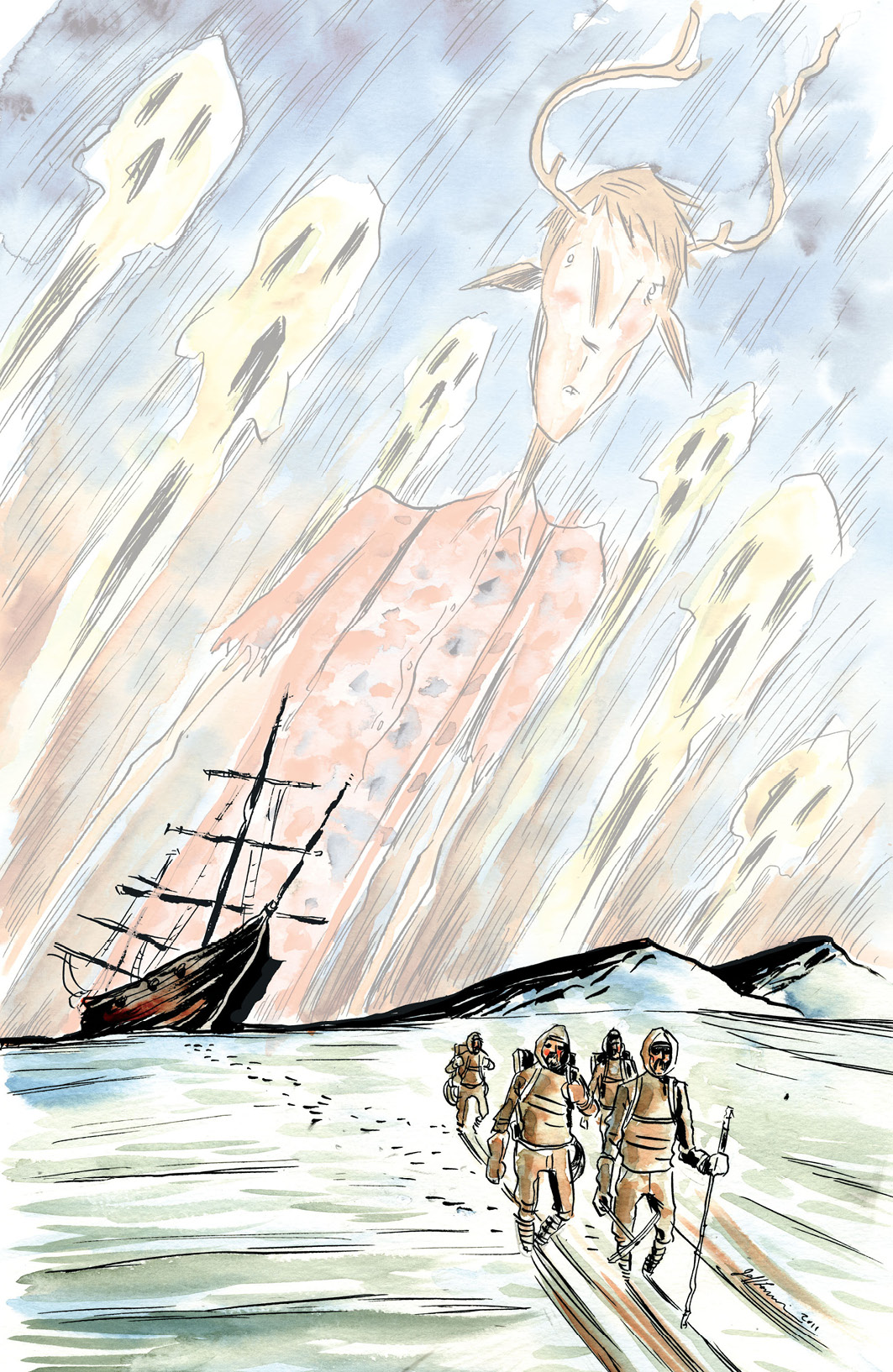

It is therefore the very partedness of parted things, their quality of binding together things in relations of unwholeness, that marks them as response-able. This is the aspect that the focalization of Sweet Tooth’s narrative through Gus most productively allows to emerge: not only is Gus, as a part of Tekkeitsertok, bound to the massacred Inuit community, but the comic also shows us his identification with the animal nonhuman (Fig. 23), the immanent sacred (Fig. 24), and the Alaskan landscape (Fig. 25)—the last through the skeletal face of Tekkeitsertok and, in one case, Gus himself shown haunting the clouds of the Arctic sky.

Fig. 23 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #1 (2009) © Jeff Lemire and Vertigo Comics. All rights reserved.

Fig. 24 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #20 (2011) © Jeff Lemire and Vertigo Comics. All rights reserved.

Fig. 25 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #26 (2011) © Jeff Lemire and Vertigo Comics. All rights reserved.

In one striking vision that Gus experiences, he encounters an ambiguous figure who appears to be Tekkeitsertok, but who looks extremely similar to the adult Gus we later see in Sweet Tooth #40. This figure’s answer of ‘Not yet’ when Gus asks, ‘Who?’59 (Sweet Tooth #13) amplifies the sense that it gestures towards some potential that exists within Gus—yet another form, like the murdered Inuit child, like the deer he encounters, like the metaphysical form of Tekkeitsertok and the land, that he could have been/could be/could become. In many ways, Sweet Tooth is the story of how Gus—whose creation was also his disruption, an act of parturition and partition that brought him into being as a being separate (yet also inseparable) from another being—explores and reconciles himself to the paradoxes of his parted existence.

Perhaps, even beyond its mischievous invitation to imagine what oil or a virus might be like if it were a little boy with antlers growing out of his head, Sweet Tooth asks us to reconcile ourselves to the paradoxes of our existence. After all, as Matthew Zantingh has observed, the comic ‘calls on readers to witness the suffering of Indigenous lives at the hands of colonialism and to imagine a different future’,60 just as Tekkeitsertok poses the same implicit demand to Gus—and, too, asks us to imagine the possibility of affinity with nonhuman others from the position of someone who looks (mostly) like us. Furthermore, as genetic and microbial humans embedded in Earthly ecological systems, we are also confronted by the tensions of partedness. Like Gus, we must ultimately ask ourselves: how can we conceive of ourselves as beings defined by affinities that cross species, scale, and animacy and interpret ourselves as existing in relation with a past and a future that we have responsibilities to?

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara, Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality (London: Routledge, 2000), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203349700

Allewaert, Monique, Ariel’s Ecology: Plantations, Personhood, and Colonialism in the American Tropics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Appel, Hannah, Arthur Mason, and Michael Watts (eds), Subterranean Estates: Life Worlds of Oil and Gas (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801455407-002

Banita, Georgiana, ‘Sensing Oil: Sublime Art and Politics in Canada’, in Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture, ed. by Sheena Wilson, Adam Carlson, and Imre Szeman (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017), pp. 431–57.

Barad, Karen, Meeting the Universe Halfway (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822388128

Boetzkes, Amanda and Andrew Pendakis, ‘Visions of Eternity: Plastic and the Ontology of Oil’, e-flux, 47 (September 2013), [n.p.].

Brown, Wendy, Regulating Aversion: Tolerance in the Age of Identity and Empire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400827473

Davis. Lennard J, Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body (New York: Verso Books, 1995).

Doucleff, Michaeleen, ‘Are There Zombie Viruses—Like the 1918 Flu—Thawing in the Permafrost?’, NPR.org (19 May 2020).

Ferebee, K.M., ‘Pain in Someone Else’s Body: Plural Subjectivity in TV’s Stargate: SG-1’, LLIDS: Language, Literature, and Interdisciplinary Studies, 4.3 (Summer 2020), 26–48.

Fox, A.C. Heron, and M.Q. Sutton, ‘Characterization of natural products on Native American archaeological and ethnographic materials from the Great Basin region, USA: A preliminary study’, Archaeometry, 37.2 (August 1995), 363–75.

Ghosh, Amitav, ‘Petrofiction: The Oil Encounter and the novel’, The New Republic (2 March 1992), 29–34.

Haraway, Donna, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, in Feminist Studies, 14.3 (Autumn 1988), 575–99, https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Harrell, J.A. and M.D. Lewan, ‘Sources of mummy bitumen in ancient Egypt and Palestine’, Archaeometry, 44.2 (May 2002), 285–93.

Helmreich, Stefan, Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009).

Helmreich, Stefan, Sounding the Limits of Life: Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400873869

Kerber, Jenny, ‘Up from the Ground: Living with/in Petrocultures in the US and Canadian Wests’, in Western American Literature, 51.4 (Winter 2017), 383–9, https://doi.org/10.1353/wal.2017.0001

Kurlansky, Mark, Salt: A World History (New York: Walker & Co., 2002).

LeMenager, Stephanie, Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jav188

Lemire, Jeff, Sweet Tooth (New York: Vertigo Comics, 2009–2013).

McDonald, Grantley, ‘Georgius Agricola and the Invention of Petroleum’, Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance, 73.2 (2011), 351–63.

Mooney, Chris, ‘Why you shouldn’t freak out about ancient “Frankenviruses” emerging from Arctic permafrost’, The Washington Post (11 September 2015).

Moore, Jason W., Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (London: Verso, 2015).

Morton, Timothy, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Pendakis, Andrew and Ursula Biemann, ‘This Is Not a Pipeline: Thoughts on the Politico-Aesthetics of Oil’, in Energy Humanities: An Anthology, ed. by Imre Szeman and Dominic Boyer (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), pp. 504–11, https://dx.doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.sightoil.3–2.2

Povinelli, Elizabeth, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822373810

Povinelli, Elizabeth, The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002).

Povinelli, Elizabeth, ‘Do Rocks Listen? The Cultural Politics of Apprehending Australian Aboriginal Labor’, American Anthropologist New Series, 97.3 (September 1995), 505–18, https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1995.97.3.02a00090

Roth, Andrew, ‘Permafrost thaw sparks fear of “gold rush” for mammoth ivory’, The Guardian (14 July 2019).

Schrader, Astrid, ‘The Time of Slime: Anthropocentrism in Harmful Algal Research’, Environmental Philosophy, 9.1 (2012), 71–94, https://doi.org/10.5840/envirophil2012915

Schrader, Astrid, ‘Abyssal intimacies and temporalities of care: How (not) to care about deformed leaf bugs in the aftermath of Chernobyl’, Social Studies of Science, 45.5 (2015), 665–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312715603249

Ulstein, Gry, ‘Brave New Weird: Anthropocene Monsters in Jeff VanderMeer’s The Southern Reach’, Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies, 43.1 (March 2017), 71–96, https://doi.org/10.6240/concentric.lit.2017.43.1.05

Wilson, Sheena, Adam Carlson, and Imre Szeman (eds), Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017).

Wittgenstein, Ludwig, Philosophical Investigations (Oxford: Blackwell, 1953).

Wynter, Sylvia, ‘Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Truth/Power/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument’, CR: The New Centennial Review, 3.3 (Fall 2003), 257–337.

Yusoff, Kathryn, ‘Anthropogenesis: Origins and Endings in the Anthropocene’, Theory, Culture & Society, 33.2 (2016), 3–28, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276415581021

Zantingh, Matthew, ‘Tekkietsertok’s Anger: Colonial Violence, Post-Apocalypse, and the Inuit in Jeff Lemire’s Sweet Tooth Series’, Studies in Canadian Literature, 45.1 (2020), 5–28.

1 The research for this chapter was carried out with the support of the European Research Council.

2 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #26 (New York: Vertigo Comics, 5 October 2011). As Sweet Tooth is inconsistently paginated, I will cite by issue rather than by page.

3 The misspelling ‘Tekkietsertok’ and the accurate spelling ‘Tekkeitsertok’ are both used in the comic, but I have opted to use the more accurate transliteration here.

4 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #26.

5 Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), p. 58.

6 Kathryn Yusoff, ‘Anthropogenesis: Origins and Endings in the Anthropocene’, Theory, Culture & Society, 33.2 (2016), 3–28, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276415581021.

7 Ibid.

8 Amanda Boetzkes and Andrew Pendakis, ‘Visions of Eternity: Plastic and the Ontology of Oil’, e-flux, 47 (September 2013), [n.p.].

9 Elizabeth Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), p. 28, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822373810.

10 Ibid., p. 46.

11 Elizabeth Povinelli, ‘Do Rocks Listen? The Cultural Politics of Apprehending Australian Aboriginal Labor’, American Anthropologist New Series, 97.3 (September 1995), 505–18, https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1995.97.3.02a00090; Povinelli, Geontologies, p. 30.

12 Elizabeth Povinelli, The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), p. 219, 241.

13 Monique Allewaert, Ariel’s Ecology: Plantations, Personhood, and Colonialism in the American Tropics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), p. 8.

14 Ibid., p. 2.

15 Amitav Ghosh, ‘Petrofiction: The Oil Encounter and the novel’, The New Republic (2 March 1992), p. 30.

16 Hannah Appel, Arthur Mason and Michael Watts (eds), ‘Introduction: Oil Talk’, in Subterranean Estates: Life Worlds of Oil and Gas (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015), p. 10, https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801455407-002.

17 Jenny Kerber, ‘Up from the Ground: Living with/in Petrocultures in the US and Canadian Wests’, Western American Literature, 51.4 (Winter 2017), 383–9 (p. 386), https://doi.org/10.1353/wal.2017.0001.

18 Astrid Schrader, ‘The Time of Slime: Anthropocentrism in Harmful Algal Research’, Environmental Philosophy, 9.1 (2012), 71–94 (p. 79), https://doi.org/10.5840/envirophil2012915.

19 K. M. Ferebee, ‘Pain in Someone Else’s Body: Plural Subjectivity in TV’s Stargate: SG-1’, LLIDS: Language, Literature, and Interdisciplinary Studies, 4.3 (Summer 2020).

20 Stefan Helmreich, Sounding the Limits of Life: Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), p. 62, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400873869.

21 Astrid Schrader, ‘Abyssal intimacies and temporalities of care: How (not) to care about deformed leaf bugs in the aftermath of Chernobyl’, Social Studies of Science, 45.5 (2015), 665–90 (p. 679), https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312715603249.

22 The fragmented being might arguably be particularly difficult for humans to empathize with if one accepts the argument (emerging from Lacan) that Lennard Davis makes regarding the discomfort that humans feel when confronted with fragmented bodies. Davis argues that such bodies uncomfortably call attention to the always-already-fragmented nature of the human body, in which wholeness is only ever hallucinated.

23 Stefan Helmreich, Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), p. 43.

24 Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), p. 392, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822388128. Barad uses nonbinary pronouns.

25 Povinelli, Geontologies, p. 49.

26 Barad, Meeting, p. 392.

27 Ibid., pp. 369–84.

28 Ibid., pp. 50–54.

29 Ibid., p. 55.

30 Schrader, Intimacies, p. 672.

31 Allewaert, Ecology, p. 9.

32 Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (London: Verso, 2015), p. 211.

33 Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, 14.3 (Autumn 1988), 575–99 (p. 590), https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

34 Barad, Meeting, p. 137.

35 Moore, Capitalism, p. 18.

36 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #26.

37 Ibid.

38 Sara Ahmed, Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality (London: Routledge, 2000), p. 124, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203349700.

39 Ibid.

40 Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations (Oxford: Blackwell, 1953).

41 Povinelli, The Cunning of Recognition.

42 Wendy Brown, Regulating Aversion: Tolerance in the Age of Identity and Empire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), p. 20–21, https://doi.org/10.1515 /9781400827473.

43 Sylvia Wynter has explored how human and nonhuman histories are linked together by their othering under a settler-colonial regime intent on easy capitalization.

44 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #2 (New York: Vertigo Comics, 7 October 2009).

45 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #38 (New York: Vertigo Comics, 3 October 2012).

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #37 (New York: Vertigo Comics, 5 September 2012).

49 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #39 (New York: Vertigo Comics, 7 November 2012).

50 Gry Ulstein, ‘Brave New Weird: Anthropocene Monsters in Jeff VanderMeer’s The Southern Reach’, Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies, 43.1 (March 2017), 71–96 (p. 78), https://doi.org/10.6240/concentric.lit.2017.43.1.05.

51 Ibid., p. 74.

52 Chris Mooney, ‘Why you shouldn’t freak out about ancient “Frankenviruses” emerging from Arctic permafrost’, The Washington Post (11 September 2015).

53 Michaeleen Doucleff, ‘Are There Zombie Viruses—Like the 1918 Flu—Thawing in the Permafrost?’, NPR.org (19 May 2020).

54 Andrew Roth, ‘Permafrost thaw sparks fear of “gold rush” for mammoth ivory’, The Guardian (14 July 2019).

55 Ulstein, ‘New Weird’, p. 78.

56 Georgiana Banita, ‘Sensing Oil: Sublime Art and Politics in Canada’, in Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture, ed. by Sheena Wilson, Adam Carlson, and Imre Szeman (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press: 2017), pp. 431–57 (p. 446).

57 Stephanie LeMenager, Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 92, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jav188.

58 Andrew Pendakis, ‘This Is Not a Pipeline: Thoughts on the Politico-Aesthetics of Oil’, in Energy Humanities: An Anthology, ed. by Imre Szeman and Dominic Boyer (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), pp. 504–11 (p. 506), https://dx.doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.sightoil.3–2.2.

59 Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth #13 (New York: Vertigo Comics, 1 September 2010).

60 Zantingh, Matthew, ‘Tekkietsertok’s Anger: Colonial Violence, Post-Apocalypse, and the Inuit in Jeff Lemire’s Sweet Tooth Series’, Studies in Canadian Literature, 45.1 (2020), p. 7.