1. A Secret Inheritance

© 2022 Dorinda Evans, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0304.01

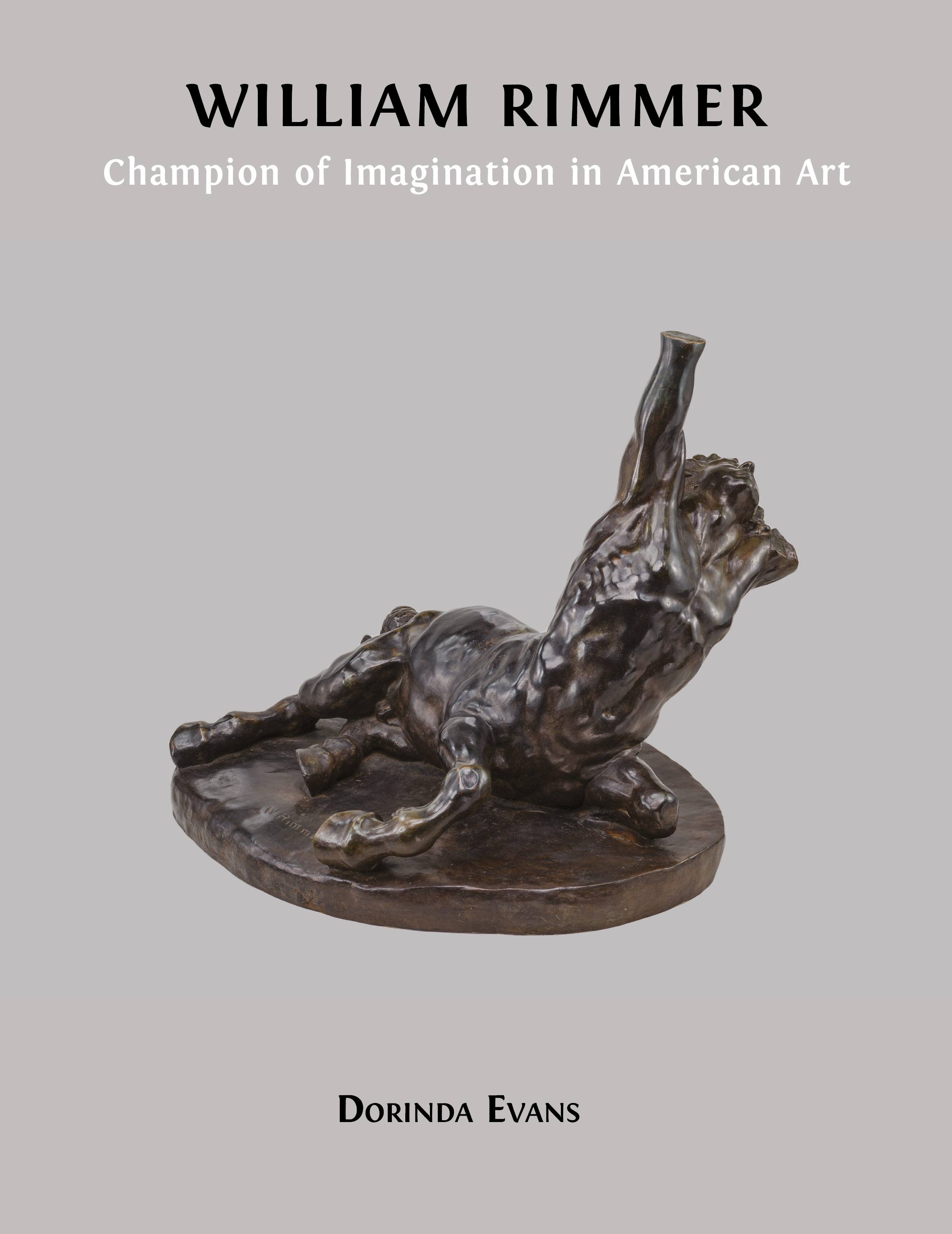

William Rimmer (1816–1879) was a major and highly influential American artist, who, fairly consistently, managed to be misunderstood. Since his death, assessments of him have varied widely. He has been labeled both a neoclassicist and a precursor of the rebellious French sculptor, Auguste Rodin.1 Yet the content of Rimmer’s sculpture is very different from both. Just as concerning, many of his paintings and drawings have been misinterpreted, and his unsigned work confused with that of others. This book is an attempt to reconstruct his artistic identity and to provide a long-overdue reconsideration of his place in history.

To begin with, Rimmer had a much more creative mind than has been assumed. At his death in 1879, he was typically praised as a man of “original genius.”2 In the context of flattering obituaries, this might not seem so unusual. But posthumously he gave new life to this estimation when he won a contest that acknowledged his fertile imagination. In 1880, a national journal of arts and literature, out of Buffalo, asked its readers to name which two American artists, alive or dead, were “pre-eminent in imaginative power.”3 Given Rimmer’s relative obscurity as a man of “reserved habits,” the result must have been a surprise.4 He shared the honor with Elihu Vedder — a still living, European-trained artist who was primarily a painter and book illustrator. They both were innovative in subject matter, but Rimmer differed in also being unusually original in sculptural form.

With an uncommon breadth of talent, Rimmer split his creative energy as an artist. He worked in both two and three dimensions as well as taught art. During his career, he had to overcome the drawbacks of being not only self-taught — except for some lessons from his father — but also hindered by a late start so that he was not even recognized as a professional until the age of forty-five. It was then that he became a sculptor and necessarily only part-time.5 He produced few saleable works over a twenty-year career and supported himself by teaching. When he did exhibit — which was rare — his contributions tended to sacrifice public appeal by being inaccessible in meaning. Not only was his iconography esoteric, but he also earned a reputation for a curious reticence by not offering explanations.6 In short, he rarely created artworks for the purpose of earning public favor or even selling them. According to a now-destroyed diary, he typically practiced as an artist “to gratify” his family or “in gratitude” for a friend.7

As for Rimmer’s posthumous fame, it was boosted by several means. In addition to having admirers who remembered him, he had published a drawing book that was said to be the only volume on human anatomy that had “any true artistic character.”8 A memorial exhibition was arranged at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (where he had taught), in 1880 and a biography by the sculptor Truman H. Bartlett followed in 1882.9 For their preservation, between 1905 and 1907, bronze casts were produced from his best known sculptures which Rimmer had modeled in clay and cast in plaster: Falling Gladiator, Dying Centaur, and Fighting Lions. In 1913, four of his drawings appeared in New York’s much-publicized International Exhibition of Modern Art, also called the “Armory Show,” in a section devoted to the finest American art.10 Also in the twentieth-century, he was repeatedly rediscovered through small, one-man exhibitions in 1916, 1946 and 1985.11 His stubborn independence, extensive influence through teaching, and avant-garde ideas are why he is worthy of close consideration. Beyond this, there is the undeniable quality of his surviving work.

Rimmer had been born in Liverpool, England, on February 20, 1816, and brought at age nine to Boston, Massachusetts. His father, Thomas Rimmer, possessed the advantages of a well-educated man, purportedly because he had a connection with the French throne, but actually because he grew up in a prosperous English family, about whom nothing else is known. He became a timber merchant and married an Irish woman, Mary Burroughs, in Liverpool.12 In 1818, he arrived in New Brunswick, Canada, at the recorded age of twenty-three (suggesting that Thomas had been born in 1795) and sent for his wife and child to follow.13 They first lived in Nova Scotia and, in 1819, moved to Aroostook County, Maine. Strangely, Thomas found his chances for advancement repeatedly thwarted, so he worked first as a common laborer and by 1824 as a boot maker.14 He relocated with his family to Boston in 1826, and together he and his wife had seven children.

Mistakenly — with notable consequences for his eldest son — Thomas claimed that he was the French dauphin and rightfully should have succeeded Louis XVI, who had been executed in 1793.15 He had this delusion apparently by the time he was ensconced in Canada with what he deemed was a fake identity as “Thomas Rimmer.” That is, he believed that he had been falsely declared dead and his inheritance, as the king’s son, stolen by the king’s brother, Louis XVIII. His survival depended upon moving often to avoid — as he contended — French secret agents. According to his great granddaughter, his mere existence threatened the pretender whose agents pursued him because of a special locket he always wore. It held the only evidence of his heritage: the names, birthdates and titles of his parents as well as his own. In further proof of his claim, he physically resembled the Bourbons, particularly in his profile and lobeless ears.16

Taking pride in his education, Thomas spent what he could on books and taught his children himself, including in such subjects as history, botany, and ornithology as well as painting, drawing, and the playing of musical instruments.17 His son, the wiry and athletic William, supplemented his interest in history by learning Latin as well as French. By all accounts, William needed little encouragement to read widely on his own as he had “an exceedingly studious disposition.”18 Clearly, he had the same autodidactic nature as his father who pursued his remarkably diverse interests by experimenting with electricity, metallurgy, and the raising of silkworms.19 Almost twenty years after his wife’s death from tuberculosis at age forty in 1836, Thomas died a painful death from “chronic diarrhea” in Boston in 1852. By then, he was a disillusioned alcoholic.20

At a young age, William Rimmer became known for his creativity in drawing pictures, constructing toy boats, and cutting small horses out of discarded India-rubber used in the soles of old boots.21 Yet, despite his early inclination toward an artistic career, he had to pursue additional professions for financial support. He assisted and then followed his father in becoming a shoemaker and, with that as his most stable source of income, intermittently tried other paths such as that of a typesetter, sign maker, soap maker, altarpiece painter, and lithographer.22 Except for a few lithographic prints, his early artworks are lost.23

From about 1841 to 1847, Rimmer undertook a more ambitious direction and sporadically studied medicine. The opportunity arose because a friend, Abel Washburn Kingman, was a physician in Brockton, Massachusetts. Rimmer read the medical works from Dr. Kingman’s library, observed instruction in dissection at Massachusetts Medical College, and then settled on a mixed career as a country doctor, shoemaker and itinerant portrait painter.24 Fusing his main interests after 1863, he became an art-school lecturer on the correct drawing of human anatomy, modified for artistic purposes.25

Perhaps the switch to medicine was inspired by his marriage to Mary Hazard Corey Peabody, a congenial Quaker about eight years younger, in 1840. Described as “very tall,” she still measured shorter than Rimmer and was an “unusually striking looking person.” She had “very white skin and black hair and dark eyes.”26 Thereafter, Rimmer devoted himself to supporting and raising a family who occupied the center of his life. His wife and children were a source of both happiness and grief as five of his eight offspring died in infancy. Adding to his misfortune, his wife became an invalid with chronic kidney disease at age forty-four in 1868.27

Rimmer’s biographer, Truman Bartlett, thought the prioritizing of his family led to “unevenness” in his career as an artist, implying a stunted ambition. This might be so, but, along with William Morris Hunt, Rimmer became one of the two most revered teachers in the Boston art community. Together, between 1861 and 1879, they dominated the Boston art scene.28 Rimmer taught in other cities as well, such as New York; Worcester, Massachusetts; New Haven, Connecticut; and Providence, Rhode Island. In fact, his success as a teacher came to overshadow public knowledge of him as a professional artist. At the height of his pedagogical fame — from 1866 to 1870 — Rimmer’s most important teaching and administrative position was seasonal, as director of the School of Design for Women at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a private college in New York. He would return to Boston for the summer.

Before he died in 1879, the artist produced two books at the instigation of friends, The Elements of Design (1864) and the better-known Art Anatomy (1877). They present most of his subject matter and are indicative of how he conducted his classes.29 The first book, with plates of chiefly stick, skeletal and manikin figures, was written mainly for the parents and teachers of young art students.

The second, for more advanced students, is a large atlas of comparative human anatomy, showing different ages and sexes, with photomechanically produced plates. It includes detailed illustrations of the exterior, along with muscles and skeletons, of variously sized human bodies. What is unusual in this kind of book is the comparison of the heads and skulls of a man, lion, and ape and a limited section on interpreting human profiles and facial expressions. The latter are sometimes extreme caricature.30 The purpose of codifying facial characteristics was presumably to help art students convey the moral status of invented characters. But it was justly criticized for lacking sufficient interpretation.31 Today this lack would be less concerning than the insensitivity of some of his commentary.

With the book’s chief focus on the male nude in various postures, it demonstrated anatomical drawing as not nature dependent, but, rather — as art anatomy — the product of an artist’s conception. For this, figures generally influenced by the Italian Renaissance master, Michelangelo, proved helpful as a teaching tool. The emphasis on the male appears to have been largely due to ancient Greek and Renaissance precedent.

Many who knew Rimmer spoke of him as at his best when giving “inspired” lectures on the artistic portrayal of human anatomy, which he illustrated with images from his memory and imagination in rapid blackboard sketches.32 He would show how a human body could be built upwards from the bones and muscles to the outer skin, and how a person might be shown in various actions and from various viewpoints.33 Frequently he would produce entire figures and elaborate compositions of several of them. Unfortunately, these drawings — reputedly often spirited or strikingly beautiful — were necessarily erased after class, an action that numerous students found painful to witness. Deepening this loss, Rimmer usually worked quickly and discarded what he disliked. In the end, he destroyed most of his other artwork as well.34

This destruction included clay models that were reported to be “more wonderful” than the exhibited sculpture.35 Probably only about 200 works in different media survive. Most of what has been exhibited since 1883 has been the same pieces. Unfortunately, a number of the more recent additions have been painting misattributions.36

Long before Rimmer became a teacher, he taught himself. “He was a green young man of eighteen or twenty when I first knew him,” a brother artist recalled, “but one could see that he had great mental capacity. His drawing was always full of energy, but not suited,” he added presciently, “for commercial purposes.”37 This was the opinion of Benjamin Champney, a fellow apprentice, whom Rimmer had joined in 1837 for about a year at Thomas Moore’s lithographic print shop in Boston. Moore’s shop trained talented beginners who learned from each other as well as from the chief draughtsman.38 Champney continued that Rimmer “loved the Old Masters, and could then, as he did more perfectly later, indicate with a few strokes of his pencil the human figure in action. He could even then paint a head in a rough way, counterfeiting the Old Masters’ tone and color.”39 Another beginner in this print studio remembered Rimmer as someone who “always took part in the discussions on art matters [and] his perceptions and aspirations were far above the others.”40

His earliest work includes a design for Moore for a sheet music cover for The Fireman’s Call (fig. 1), which has autobiographical associations and was drawn on lithographic stone. In addition to having a fine singing voice himself, Rimmer was a volunteer with Boston’s Fire Engine Company No. 12, so the depiction of a fireman’s rescue of a child would inevitably appeal to him.41 In fact, the subject relates to Rimmer’s character. His capacity for selfless daring and family loyalty were such that he once rushed into a burning and collapsing building in a near-suicidal mission that alarmed onlookers and became the talk of the town. He had feared that his brother, Thomas Jr., who was also fighting the fire, had been trapped there. Fortunately, he then caught sight of him outside.42

Fig. 1 The Fireman’s Call (Music Cover), 1837. Lithograph, image: 7 1/8 x 8 ¾ in (18.12 x 22.25 cm). Courtesy the Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

Although The Fireman’s Call is an early work, the awkward drawing of the advancing mother who seems anchored by an oddly enlarged ankle and foot, does not jibe with Champney’s description. A co-worker at Moore’s might have had this in mind when he noted that occasionally “We thought his drawings exaggerated, but he always defended them.”43

While working in a lithographic medium in the late 1830s, Rimmer produced copies after well-known artists, probably as part of his self-instruction. One of these is The Banished Lord (fig. 2), a small copy, printed in reverse, after an English work: Sir Joshua Reynolds’ untitled, bust portrait of a man (Tate Gallery). As sometimes happened, the original painting was copied as a print with an invented title. From its appearance, Rimmer’s version was generally based on the 1777 mezzotint after Reynolds (fig. 3) or one of its many copies.44 That Rimmer should be attracted to a theme of banishment, and a sorrowful man wrapped entirely in a cloak, suggests the impact of his father’s claim. The picture’s title refers to the Rev. Thomas Warton’s meditation on the vanity of life in his 1745 poem, “The Pleasures of Melancholy”, but the image and Warton’s text were not published together. Their union is the result of the ingenuity of the engraver who combined one of Reynolds’ character pictures or “old heads” in 1777 with the subject of the poem for better print sales.45

Fig. 2 The Banished Lord (Formerly: Head of a Prophet), probably the late 1830s. Lithograph, 6 3/16 x 4 ¾ in. (17.75 x 12.09 cm). Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts. Photo: © Worcester Art Museum / Charles E. Goodspeed Collection / Bridgeman Images

Fig. 3 J.R. Smith, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, The Banished Lord, 1777. Mezzotint on paper, 13 ½ x 11 in. (33.70 x 27.90 cm). Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Bequeathed by William Finlay Warren, 1886

Rimmer surely felt the injustice of losing his father’s supposed birthright. His own position as the eldest son of the presumed dauphin was almost never mentioned to friends, but, in at least one lapse or moment of closeness, Rimmer did tell a neighbor that his real identity would surprise him.46 He did not speak further on the subject or — as far as is known — ever act on his belief. Possibly he considered his father too powerless and the title claim too late to pursue effectively.

As for other claims, Rimmer did assume an academic title during his lifetime. After his apprenticeship with Dr. Kingman — like many physicians at the time — Rimmer practiced without a license, and, contrary to his biographer’s claim, he never received a diploma from the Suffolk County Medical Society.47 As a physician, he had some success with “difficult cases” and in treating such diseases as typhoid fever, but he did not receive enough pay to sustain his family, and his health suffered from the strain of overwork. Therefore, after about sixteen years — during which time, art was his recreation — he abandoned his medical practice in 1863 but retained the honorific “doctor.”48 Ostensibly, he did this because his livelihood thereafter depended upon teaching at art schools as an anatomist rather than as an artist. But it was thought at the time that he also had a “great regard for the dignity of his character.”49 He was distinguished looking, athletically built and relatively tall, so that a stranger might infer that “he was haughty and aristocratic,” but as his biographer, Bartlett, learned, “that was far from the truth.”50

The truth, which evaded Bartlett, is that Rimmer’s opinion of himself — leading to humility or arrogance — varied to a remarkable degree, depending on his mood.51 As part of this changeableness, on occasion, he adopted another embellishment to his name and added the middle initial “P,” standing for “Phillip.” It has royal significance because it is the name of a medieval French king. In a cryptic reference, the artist signed two birth certificates and a death certificate for his children as “William P. Rimmer.”52

More meaningfully, Rimmer connected “Phillip” and royalty through a fictional story of well over 300 hand-written pages, titled “Stephen and Phillip,” that he wrote and rewrote from at least 1869 to 1879. It included the characters Stephen and Phillip, who join Rimmer as aspects of himself on a journey in search of self-improvement and divine truth. Phillip is a flawed angel who returns to earth as a lesson in humility to overcome his consistent lack of charity toward others or the sin of pride, which Rimmer thought he shared. Although Phillip assumes human form, he can change at will into a powerful lion.53

Fig. 4 Dante and the Lion, 1878. Graphite pencil on paper, sheet: 6 1/8 x 9 7/16 in. (15.6 x 24.0 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Partly purchased and partly the gift of E.W. Hooper, William Sturgis Bigelow Collection, and Mrs. John M. Forbes. Photograph © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The link that reveals that Phillip, the lion, refers to Rimmer’s French heritage is Dante Alighieri, who was one of Rimmer’s favorite poets.54 Dante wrote in Inferno (part of his Divine Comedy from 1320) about his confrontation with a lion, and Rimmer acknowledged his interest in the scene by illustrating it (fig. 4). Although Dante did not explain, his translators deduced from the context that the lion is a symbol of France representing “Philip le Bel,” King of France from 1285 to 1314.55 Supporting this connection, Rimmer depicts Phillip in his manuscript as imposing, like “the son of a great king.” Identifying with him, he speaks of himself once in the same saga as dressed in purple raiment, playing his royal part with a voice that shakes “the soul of things with its deep roar.”56 Perhaps inevitably, because of the ancient and biblical linkage (Proverbs 19:12; 20:2) between a lion and a king, the lion (which was accessible in a Boston menagerie) became one of Rimmer’s favorite subjects.57

Significantly, Phillip (fig. 5) and his prototype with Dante are different from Rimmer’s other lions in that they have vertical, flaming manes, suggestive of the intensity of a spiritual presence. In a further refinement as the drawing of his head shows, Phillip, despite being a fearsome lion, is vulnerable and sensitive with large, soulful eyes — described by Rimmer as “glowing.”58

Fig. 5 Phillip (Head of a Lion), 1869. Graphite pencil on paper, 11 1/16 x 7 ½ in. (28.1 x 19 cm). Harvard Art Museums/ Fogg Museum, Louise E. Bettens Fund, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Although his royal claim is expressed in Phillip, Rimmer was actually more concerned, in his surviving art and writing, with the spiritual state of his own soul and the universal moral condition of humanity. The second character in his story, the long-suffering spirit called Stephen, helps make this point. Rimmer’s interest in the name “Stephen” almost certainly stemmed from his close friendship with Stephen Higginson Perkins — an intellectual merchant from an old Boston family and a sometime-artist whom he met in 1858. In fact, Rimmer’s 1860 granite bust of the biblical St. Stephen was undoubtedly created to please him. But, about nine years later when he likely began his manuscript, Rimmer could evidently go further and actually identify with St. Stephen, perhaps partly because of the saint’s heavenly vision before his death (Acts: 7:56). Rimmer, too, had visionary experiences and even celestial visions.59 Moreover, Stephen, the first Christian martyr, was historically important as Paul’s predecessor. He was the first Christian to engage publicly in religious disputes.60 In this inclination to dissent, he resembled Rimmer. All three of Rimmer’s characters engage in theological debate, and, in a real life parallel, Rimmer was known to argue over religious matters in a debating society in Randolph, Massachusetts, by the mid-1850s.61 He was an impressive amateur theologian who, although Christian, had his own non-denominational viewpoint.

The Stephen in Rimmer’s narrative arrives as a demon or divided soul from Hell.62 After undergoing unbearable torture — much of it inflicted by his memories — he is overcome with remorse, his angelic self begins to be revealed and he advocates for compassion. Like Phillip, but initially much darker (even suicidal), he embodies many of Rimmer’s flaws as the artist saw them — his anger and accumulated resentments to the point of hatred — as well as his conflicted response which was his moral anguish over having such feelings.63

Both Stephen and Phillip are self-criticisms. If Phillip represents Rimmer’s mistaken pride, Stephen represents his moral inadequacy, but this difference between them is irrelevant to the story. The entire text of “Stephen and Phillip” is a wildly inventive tale, concerning three eventual friends and incorporating sub-stories and hallucinatory scenes, but it is also partly rewritten passages that drift into incoherence. At its best, it has lines that read as poetry, such as when Rimmer describes how the ocean’s “teeth grate on the ringing sand.”64

The incoherent parts of “Stephen and Phillip” are suggestive of mental illness. Rimmer did suffer from what appears to be bipolar disorder or extreme mood swings that could range from deep depression to the exuberance of mania. Otherwise known as manic depression, this is a spectrum illness with different degrees of severity, and it was not well understood in the nineteenth century. The average age of onset is eighteen which, for Rimmer, would mean his illness probably began in about 1834.65

Because of Rimmer’s moodiness, as Bartlett stated, the opinions of those who knew him could differ greatly. “Ordinary people,” he reported, “were often half in doubt of his sanity.”66 Rimmer himself spoke of madness and of hearing the “voices of demons,” saying it came from “my own madness, the disorder of my soul changing the sweet melody of nature into groans.”67 He recounted experiencing both mania and depression: “What is it,” he asked, “that makes night what it is, mad or melancholy?”68 Conscious of his illness, he wrote of his feeling of “ecstacy” as being called a “disease of the mind.”69 Later he expressed regret over an apparent manic episode and felt “the horror of a [contrasting] sanity that was beside itself in what had gone before.”70

Unfortunately, his mood swings could have adverse financial consequences, such as when he finally earned enough to purchase a small house and then impulsively sold it to lend the money to a needy friend.71 In these shifts, he could develop grand ideas that he later abandoned, such as his plan in 1874 to open a public aquarium in Boston. He went so far as to rent rooms and set up tanks; then, in a reversal of confidence, he abruptly abandoned the idea, certain that it would fail. In the end, he lost several thousand dollars.72

As if he were different people, Rimmer could range widely from someone who disliked speaking to a “brilliant and tireless talker, advancing constantly the most startling and beautiful theories, and making astonishing statements, often with the most reckless disregard alike of the opinions and feelings of his hearers.73” Such inconsistent loquaciousness, rapid flow of ideas, abundant confidence, and self-absorption are typical of mania.74

On one occasion, when a sitter complained about an unfinished portrait, Rimmer, in likely a manic state, responded by taking up his paintbrush and covering it with monkeys.75 This vulnerability to mood might explain some of his more whimsical statements, such as “The thigh is the noblest part of the body.”76 Indeed, seemingly brilliant synthesizing of larger truths or a professed, unique understanding of interconnectedness — such as a physical thigh and the concept of nobility — is typical of mania.77 Such combinatory thinking possibly played a role in the occasional stereotyping of humanity in his lectures and in Art Anatomy. An example is his class drawing of two “debased” heads — or heads reflecting immorality — and categorizing them as a characteristic contrast in the debased type between an Englishman and a Frenchman.78 To condense whole nationalities into physical averages, stated factually and not meant to be caricature, presumed a stunning knowledge of mankind.

Fortunately, his loyal friend and patron, Stephen Perkins, provided a record of Rimmer’s depression in surviving correspondence. He tried to promote his friend’s career but then, tellingly, felt compelled to liken the depth of Rimmer’s despondency in 1863 to Abraham Lincoln’s persistent melancholy. Repeating Rimmer’s description of his depression as so incapacitating as to be the “twin brother of death,” he worried over its inevitable impact on the artist’s productivity.79 From the report of others, Bartlett too acknowledged Rimmer’s periodic depressions, “peculiar temper and sensitive nature,” and had the insight to conclude “for reasons beyond his control, he [could] not do his best.”80 Rimmer’s grand-niece, who had been raised by Rimmer’s brother, helped to explain by asserting that Rimmer “always worked in a ‘mood’ and hurried to produce what he wanted when the spell was on him.”81

If bipolar — which fits what is known of him — the artist went through periods of apparent normalcy (which could be for months), punctuated by one or more episodes of mania but, more often in his case, by periods of depression. He might also be extremely irritable, as reported of him, in probably a mixed state.82 Recognizing his illness provides understanding of not only Rimmer but also his artwork and the peculiar changes in his manuscript handwriting that are clearly affected by mood, such as increased speed and sudden illegibility suggestive of mania.83 To speak of Rimmer’s bouts with illness is to recognize his struggle and the obstacles he had to overcome, but — as with many, famous bipolar artists — it does not undermine the extraordinary quality of his achievement. Much of the misunderstanding of Rimmer during his lifetime and subsequently stemmed from this mental illness.

Manic depression or bipolarity is hereditary. While Thomas Rimmer’s mental illness is not known — nor when it began — he undeniably suffered which helps to explain his erratic career, his belief that he was the dauphin, his paranoia concerning secret agents, and his probable self-medication with alcohol. Grandiose delusions, such as his, are typical of manic or hypomanic (less severe) episodes.84 Reciting Thomas’ memories, his great-granddaughter wrote that he was “spirited out of France” for his safety as a small child and placed with a “very wealthy Englishman” who employed tutors for his education. As the story goes, he later joined the British army (no record of this) and, when his term ended, returned to France to make his claim. It was acknowledged, but his inheritance had already been taken by a pretender.85 One report related his death to mental illness, saying he “died raving, his screams ringing through the town all night.”86

According to her death certificate, an equal or stronger case for bipolarity concerns the artist’s oldest daughter, Mary Matilda (Rimmer) Haskell, who died at age forty-one in 1891 of “Nervous Exhaustion — Acute Mania.”87 This medical diagnosis is straightforward enough, with added evidence, to support the theory of a genetic illness.

Decades after Bartlett’s biography, Lincoln Kirstein published the tale, from hearsay, that Thomas Rimmer died in a cottage in Concord, Massachusetts, while being tended by the famous author Ralph Waldo Emerson. Sad to say, this is far from the truth. Thomas died in poverty in the House of Industry in South Boston, having lived there possibly since 1848.88 This meant he was imprisoned in a city-run workhouse for able-bodied paupers where he had to work to earn his keep. He would have been admitted by a director or committed by a court because of a minor offense, such as disorderly conduct or drunken behavior. This would explain why he did not live with his relatives in his final years.89

Some of Rimmer’s pictures refer to the family usurper myth and provide insight into his perception of his position in relation to his heritage. The myth is resurrected with the storm pictures, Scene from The Tempest (fig. 6) and Scene from Macbeth (fig. 7), an original altering and pairing of Shakespeare’s plays to create his own message. From a canvas stamp on the reverse that supports their date, we know he produced them in about 1850. The pictures offer a contrast between two sorcerers, Prospero and Hecate, and — more importantly — indirectly allude to the Rimmer family’s blocked heritage.90 Typically, as in this instance, when Rimmer was inspired by a text or visual image, he did not copy the ideas presented but rather incorporated them into his own thinking, saying something often wholly new.

In the scene (Act 1, Scene 2) from The Tempest, which was Rimmer’s favorite Shakespearean play, Prospero, who is the banished rightful duke of Milan, explains to his daughter, Miranda, that, years ago, he had his heritage stolen by his brother.91 Knowing that his usurper was on a ship passing their island, he caused the storm that led to their shipwreck, seen at the right. Although he is the wronged party, Prospero exercises restraint and, as the play unfolds, his character softens. Since Caliban, at left, is not in the play’s scene, his inclusion clarifies Rimmer’s meaning. As once ruler of the island, he also suffered the consequences of usurpation, but by Prospero. In response, he plans to seek revenge and right this wrong by immoral means. Thus, he and Prospero are essentially lower and higher versions of a person who has been similarly victimized.

Fig. 6 Scene from The Tempest, ca. 1850. Oil on canvas, 36 x 26 in. (91.4 x 66 cm). Detroit Institute of Arts. Gift of Sally A. Feldman in Memory of Joseph D. Feldman

In the Macbeth scene (Act 3, Scene 5), Hecate, a lunar goddess of witchcraft, scolds her assistants for proceeding without her in tempting Macbeth to seize the Scottish throne. He was ripe for the temptation as a military hero fresh from a victorious battle. She leaves them to take the lead herself by fooling Macbeth into believing he is greater than fate. Together the three characters are creating, or encouraging, a ruthless usurper who is under the illusion that his success is assured. Despite Hecate’s display of power, she is subservient to an unidentified “little spirit” who calls to her from the clouds above (line 446). Rimmer converts this spirit into the identifiable Cupid — who is not in the play — but, fittingly, Cupid is a symbol of desire, and his bow is trickery. In fact, as Rimmer would have known as a Latin reader, “cupido imperii” means “desire for ruling power.”92 In this guise, Cupid governs not only Hecate, but, through her, Macbeth.

Fig. 7 Scene from Macbeth, ca. 1850. Oil on canvas, 36 x 26 in. (91.4 x 66 cm). Detroit Institute of Arts. Gift of Sally A. Feldman in Memory of Joseph D. Feldman

In the first picture, Prospero and his daughter assume roles that resemble those of Rimmer and his family. Instead of his usual staff, Prospero holds the staff of Asclepius (changing Shakespeare’s text) — the Greek and Roman god of medicine — with its ancient symbol of a serpent entwined around a rod.93 Like the physician Rimmer, he will fulfill the role of a healer. With brown hair, deep-set eyes, and a straight-bridge nose, Prospero could be a self-portrait, bearing resemblance to Rimmer even more than twenty-five years later (fig. 8). Behind him, Caliban, a beast-man, is a witch’s son. His horned head recalls not only that of a horned satyr, suggesting his lecherous nature, but also, more distantly, the monstrous head of Hecate. This is one way of connecting the two scenes visually.

Fig. 8 J.J. Hawes, William Rimmer, ca. 1878. Photograph, 4 x 2 ½ in. (10.5 x 6.3 cm). Boston Medical Library, William Rimmer Collection

In the companion picture, Hecate wears an obvious mask with a visible edge, recalling her role as a double dealer who both warns and falsely reassures Macbeth. This scene undoubtedly refers to the Rimmer family’s enemies or those who encouraged them. Rimmer, or — much more likely — his father, now occupies the position of the rightful king who is the subject of plotting and will lose his kingdom to Macbeth’s overweening ambition. Paired this way, the pictures provide a moral contrast in the treatment of greed between its triumph in Hecate’s picture and its defeat in Prospero’s. Presented as a healer, Prospero retakes his dukedom but acts magnanimously toward the shipwrecked men, choosing “nobler reason” over full revenge (Act 5, Scene 1, line 26).

Characteristically, almost no detail is unimportant. At above left in Scene from The Tempest, the ball of fire, seen in an opening in the cave wall, is the “most auspicious star” that Prospero mentions (Act 1, Scene 2, line 182). Similarly, the conch shell in the foreground is not in the play but has significance as a sign of Prospero’s ability to summon the play’s action, and, in the Macbeth scene, the flourishing plants and water at lower right evidently refer to renewal after Macbeth’s defeat.94

Well aware of the pitfalls of a vanity such as Macbeth’s, Rimmer ridiculed any dreaming with regard to his father’s claim. He wrote in his undated “Stephen and Phillip:” “And Self was a great King, and others bowed down before him, and he sang in royal robes, master by one consent.”95 That is, others bow to a robed king — as a requirement of the office — but only a fool would think this meant consent to his ascension of the throne.

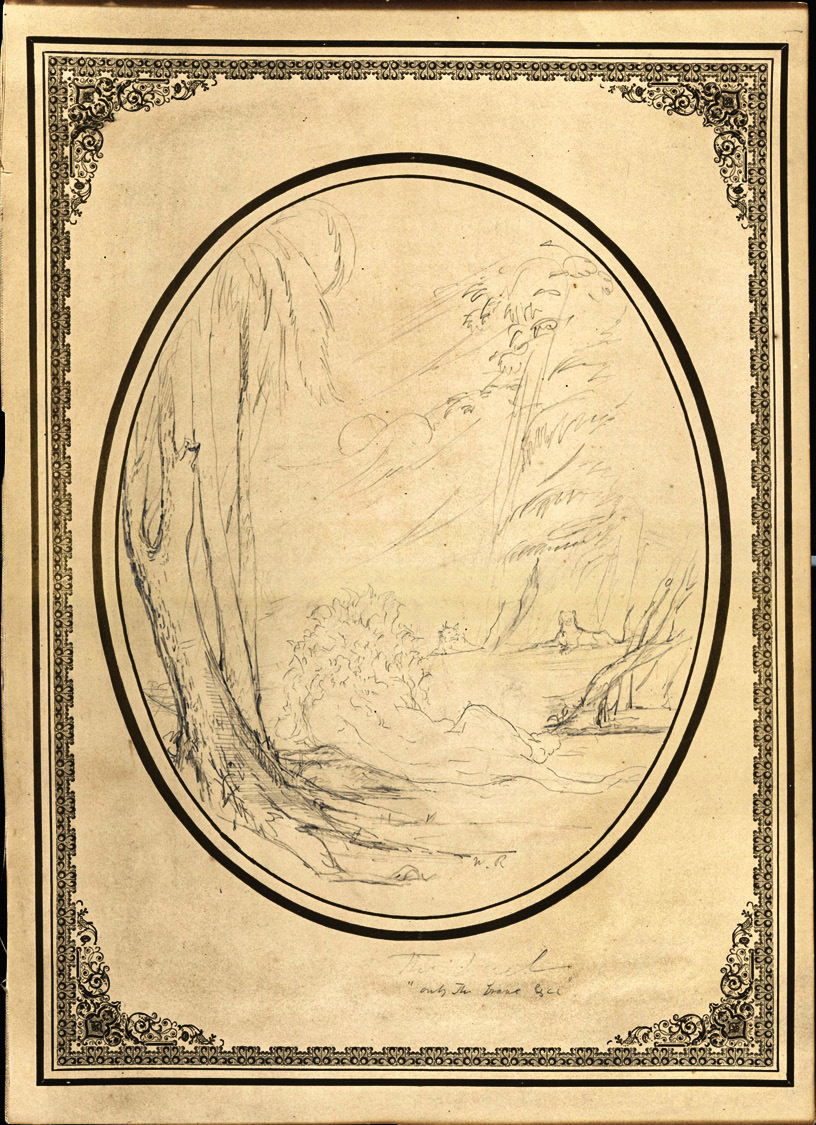

A perhaps related drawing is The Duel: “Only the Brave” (fig. 9) which is also undated. Created for an oval lithographed mount, it shows a lion, from the back, reclining beneath a strongly rooted but partially broken tree which can be interpreted as a symbolic comment on this lion. He looks across an empty expanse at a lioness and second lion. In doing so, he appears to recognize that possession of the female has passed to a younger rival, or that she has betrayed him. The one clue is that the picture is inscribed at bottom right, outside the oval: “The Duel/ ‘only the brave &cc.’” This alludes to Laurence Sterne’s twelfth sermon in The Sermons of Mr. Yorick which is on the theme of generosity and forbearance when revenge is expected. The paraphrase is from the line “The brave only know how to forgive; — it is the most refined and generous pitch of virtue … but a coward never forgave. — It is not in his nature.” Sterne’s example is the biblical Joseph, son of Jacob, who was sold into slavery by jealous brothers and yet able to forgive them.96

Fig. 9 The Duel: “Only the Brave,” probably 1860s or 1870s. Graphite on paper, 18 x 12 ¾ in. (45.73 x 32.40 cm). Boston Medical Library, William Rimmer Collection

Rimmer created a different story with his metaphorical scene of lions. The distant opponent is not well defined, so the viewer needs to imagine the rest of his form and most of the female as well. The trees are again significant in that the lion currently with the female is near a vigorously growing tree, whereas she is separated from the foreground lion by dead branches. This leonine interaction has been interpreted as a comment on the Rimmer family myth that has the near lion turning his back on his enemy and gazing at his family in a refusal to fight.97 Turning the back is more avoidance than forgiveness, but, with either interpretation, this clearly symbolic drawing of treachery and forgiveness could signal acceptance. Either Rimmer accepts the successful claimant to the French throne, Louis XVIII, or he unrelatedly forgives someone who has wronged him. Regardless, compassion and forgiveness were ideals that he sought to embrace throughout his life, and they appear to relate to his father’s experience.98 Like Prospero — or like St. Stephen who famously, at his death, forgave his persecutors (Acts: 7:60) — he had no great desire for vengeance.

Yet Rimmer’s family kept the story of his father’s royal birth alive. In the family scrapbook, which has his wife’s name engraved on it, is a relevant newspaper clipping. It conveys the erroneous story that the Empress Josephine had been murdered by poisoning in 1814 to prevent her from communicating to her friend, Czar Alexander I, the proofs she had that the son of Louis XVI had been taken from prison and was still alive.99

Before he died, Thomas Rimmer gave his oldest son his specially designed locket (which now had a broken chain) in a box and told him not to let anyone know that he had it. A granddaughter wrote that, at the end of his life, when Rimmer was preparing to visit his daughter, Adeline, he found the box, wrapped in yellowed paper and tied with string. As she related, “He sat they say a long time with it before him undecided whether to open it or not.” When he finally did, he found the box empty with “the imprint of the locket and three pieces of the chain, still in the cotton and nothing else.”100

In coming to terms with his heritage, Rimmer wrote: “The highest pleasure of existence is intellectual joy [replaced with “peace”].” He added: “no tinkling of the senses, no pride of things, no court, no retinue” can compare with it.101 This might well pertain to his sense of fulfillment through the academic and cultural life of the Cooper Union in New York, where he spent his happiest years.102

Rimmer’s peaceful acceptance of his lot reflects Warton’s poem on melancholy, where Warton speaks of the material trappings of a court and concludes that, without them, “far happier” is the banished lord.103 The poet’s preference is for a solitary, contemplative life — enriched by depth of feeling and an educated imagination. But unlike Warton’s exemplary lord, Rimmer never cut himself off from others and departed even further from the lure of royal trappings with his empathy for the poor, the unfortunate, and the unjustly treated.104 He repeatedly took action on their behalf. Arguably, he was much more affected by his father’s despair and humiliation than his father’s birthright.

Apparently repelled by the thought of benefiting from his father’s tragedy, he told his children never to give details about their ancestral heritage to anyone outside the immediate family. This request passed through a couple of generations. It was his “express wish.”105 For their part, the family thought of him as admirably honorable, altruistic and “free from guile.“ In a moral sense, he had a nobility that was not conferred by title. As the youngest daughter, Caroline, expressed it, “None will ever know perhaps the degree to which my father led a noble life.“106

1 For neoclassicist, see Helen W. Henderson, “Has New England an Art Sense?” The Bookman; a Review of Books and Life 51 (April 1920):138. For Rodin, see Wayne Craven, Sculpture in America, rev. ed. (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1984), 347. Craven likens the style of Rimmer’s Seated Man (Despair) to that of Rodin’s work. Jeffrey Weidman in his William Rimmer: Critical Catalogue Raisonné (Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International, 1983), 1: 42–43, notes that both created fragmented pieces and thought of sculpture “in terms of formal values.” The linkage with Rodin occurs more frequently than with neoclassicism and goes back at least to 1905. See Charles de Kay, “Honors for William Rimmer, Sculptor and Teacher,” The New York Times, September 17, 1905, SM6.

2 For genius, see Anon., “The Late Dr. Rimmer,” Boston Daily Advertiser, August 23, 1879, [2].

3 For contest, see C.W. Moulton, ed., Queries with Answers in Literature, Art, Science and Education (Buffalo: C.L. Sherrill and Co., 1886), 9 (quote), 59. The question was asked of the readership in an 1885 issue of Queries, A Monthly Series of Published Questions and answered in a subsequent issue.

4 Truman H. Bartlett, The Art Life of William Rimmer: Sculptor, Painter, and Physician (New York: Kennedy Graphics, 1970), 146 (quote). See also ibid., 21. This is a reprint of the 1890 ed. with a new pref. by Leonard Baskin. The 1890 ed. is a reprint of the 1882 ed.

5 For self-taught, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 31.

6 On reticence, see Bartlett, Rimmer, vi, 11; and Almira B. Fenno-Gendrot, Artists I Have Known (Boston: Warren Press, [1923?]), 36.

7 On public favor, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 144. The diary entry is overstated. For instance, he did create some inexpensive pictures that were sold at an auction (ibid., 20) and drawings to be sold at charities to benefit soldiers and a hospital. See C.H.D., “Chicago Sanitary Fair, 1865,” Boston Daily Advertiser, May 18, 1865, 6; and Anon., “Hospital for Women and Children,” Boston Post, October 20, 1865, 4. For the quotes, see the undated diary reference in Bartlett, Rimmer, 130. Bartlett saw one or two volumes that no longer exist. See Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 4:1328–29n. These diaries were perhaps within the Rimmer material offered to Harvard University by a descendant in about 1936 and, except for some drawings, refused. On this see Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 4:1353–54n.

8 Edward R. Smith, “Dr. Rimmer,” Architectural Record 21, no. 3 (March 1907): 201.

9 On the 1880 exhibition, which ran from May to about mid-November, see Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 4:1323n. The checklist catalogue by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, was published as Exhibition of Sculpture, Oil Paintings, and Drawings by Dr. William Rimmer (Boston: Alfred Mudge and Son, 1880). In appendix C of volume 4 of his catalogue, Weidman reproduces this checklist plus checklists for an 1883 sale of Rimmer’s work at J. Eastman Chase’s Gallery, Boston, and the exhibitions of 1916 (reconstructed) and 1946–1947. According to Caroline Rimmer’s notation in her copy of Bartlett’s 1882 book in the possession of collateral descendant Robert Korndorffer, Bartlett never knew her father.

10 See Gail Stavitsky, Laurette E. McCarthy, and Charles H. Duncan, The New Spirit: American Art in the Armory Show (Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum, 2013), 76. See also Walter Pach’s letter, May 23, 1946, to Lincoln Kirstein, box 1, research file: Misc. Copies, Drawings and Lithographs, Undated, 1945–1946, Lincoln Kirstein and Richard Sherman Nutt Research Material on William Rimmer, 1849–1971, Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C. Pach thought one of the drawings was a study for the Falling Gladiator.

11 The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, organized the February 17–March 1, 1916, exhibition, with approximately 135 works and no catalogue. Lincoln Kirstein and the Whitney Museum of American Art organized the exhibition, William Rimmer, 1816–1879, at the Whitney Museum, November 5–27, 1946, and at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, January 7–February 2, 1947, for which Kirstein wrote the catalogue. Jeffrey Weidman and the Brockton Art Museum / Fuller Memorial organized the exhibition, William Rimmer: A Yankee Michelangelo, at the Brockton Art Museum, October 6, 1985–January 12, 1986; the Cleveland Museum of Art, February 25–April 20, 1986; and the Brooklyn Museum, June 6–July 20, 1986. Weidman wrote the catalogue with additional essays by Neil Harris and Philip Cash.

12 Based on family records, Bartlett, Rimmer, 2, provided Rimmer’s birthdate and birth location, identifying his mother as “Mary” and Irish, but he omitted her maiden surname. There is no known parish record. In the 1940s, William Rimmer’s grandniece, Marion M. McLean, supplied a “Burroughs” surname. On this, see Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 1:67n. This must be Mary Burroughs who married Thomas Rimmer on July 31, 1815, at the Anglican church, Holy Trinity, in Liverpool. Thomas is identified as a timber merchant. Because of the timber supply in North America, this might have been a reason to move to Canada and subsequently the United States. On their marriage, see the Marriage Register, 1813–26, p. 60, for Holy Trinity, Liverpool Records Office. They were members of the same parish. On Thomas’ education, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 2, 3.

13 Verifying much of Bartlett’s account, the record shows that Rimmer arrived in Fredericton, New Brunswick, in 1818, but he came via Ireland. Then, according to Bartlett (Rimmer, 2), he sent for his wife and son. See Terrence M. Punch, Erin’s Sons: Irish Arrivals in Atlantic Canada, 1761–1853 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2008), 1:52. There is no known record of the crossing of his wife and son.

14 Weidman, et al., Rimmer, xiii. Bartlett, Rimmer, 1, describes Thomas as an itinerant shoemaker by 1824. Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 1:69n, shows, through Boston City Directories, that Thomas’ address changed almost yearly, and his profession did not switch from laborer to boot maker until 1834. Evidently there was switching back and forth.

15 According to his death certificate, Thomas Rimmer was a decade too young to be the heir of Louis XVI. See his 1852 death certificate, giving his age as 57, under Biographical Material, box 1, Kirstein and Nutt Research Material, Archives of American Art. The U.S. Census in 1830 and 1840 uses age spans that also place him a decade too young. Furthermore, his claim is disproved by Suzanne Daley, “Genetics Offers Denouement to Mystery of Prince’s Death,” The New York Times, April 20, 2000, A1, A8. Without more precise information from the family, Bartlett, Rimmer, 1, writes of Thomas as belonging to a “branch” of the French royal family. Lincoln Kirstein, in “William Rimmer: His Life and Art,” The Massachusetts Review 2, no. 4 (Summer 1961): 686, https://doi.org/10.2307/25086738, adds, from descendants, his claim to be the dauphin. This essay is reprinted from Kirstein’s 1946 essay, unpaginated, for the catalogue of the Whitney Museum and Boston Museum exhibition. That Bartlett did not make more of the senior Rimmer’s tragic life was a point of contention with the Rimmer family. See Caroline Rimmer’s annotations in her copy of Bartlett’s biography in the possession of collateral descendant Robert Haskell Korndorffer. Weidman follows Kirstein in accepting the possibility that Thomas was the dauphin. See his listing of the family’s evidence given Kirstein in Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 1:65n3.

16 Alice Caroline (Haskell) Lapthorn, “Stories and Memoirs,” 5–6, typed manuscript in the possession of descendant Robert Haskell Korndorffer. On Bourbon resemblance, see Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 1:66n3.

17 Ibid., 6. Bartlett, Rimmer, 3–4.

18 On wiry, etc., see Bartlett, Rimmer, 9. A late student even called him a natural athlete. For this, see Smith, “Dr. Rimmer,” 196. For Latin and French and even further tutoring, see Kirstein, “Rimmer: His Life,” 687. For the quote, see Anon., “Dr. William Rimmer,” Evening Transcript, August 22, 1879, clipping, box with bar code: 3-1027-00033-7440, Kirstein and Nutt Research Material, Archives of American Art.

19 Bartlett, Rimmer, 4.

20 The death of Mary Rimmer, wife of Thomas, from “lung fever” at age 40 on October 25, 1836, is recorded in the “Massachusetts Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988,” digital images, Ancestry.com. She is buried in Boston’s South End Burying Ground which — according to Kelly Thomas, Director of Boston’s Historic Burying Grounds — was reserved for the poor. For Thomas’ alcoholism, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 4.

21 For more on early creative endeavors, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 3. For drawing, boats, and horses, see ibid., 4–5.

22 Ibid., 8–9. Rimmer, for instance, is listed in Boston Directories as a soap manufacturer in 1838 and an artist in 1843, but he was a boot maker in the 1850 United States Census.

23 On the basis of a typed note, two childish drawings of Zeus (?) on Eagles (now lost) have been attributed to him and dated 1835. This much later note says Rimmer was a “frequent visitor” to a house in Hingham in 1835. It is not known that Rimmer ever lived in Hingham. He is assumed to have been with his father in South Boston at the time. See Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 3:734.

24 Bartlett, Rimmer, 16–17. Weidman calculates Rimmer’s intermittent study with Kingman to be from about 1841 to 1847. He studied dissection in 1843. On this, see Jeffrey Weidman, et al., William Rimmer: A Yankee Michelangelo (Hanover, NH: Brockton Art Museum / Fuller Memorial, 1985, distributed by University Press of New England), xiii. On continuing shoemaking, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 19.

25 Bartlett, Rimmer, 39.

26 Bartlett, Rimmer, 16, on his marriage to a Quaker. Mary Hazard Corey Peabody was born on January 12, 1824, in Dartmouth, MA., the daughter of Isaac Peabody and Abigail Corey. See “North America Family Histories, 1500–2000,” digital images, Ancestry.com. Although she and her family cannot be connected with a specific meeting house, the location was known for its Quaker adherents. On their marital rapport, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 122. For her description, see Lathorn, “Stories and Memories,” 7.

27 Rimmer is buried in a family plot in Milton with his wife, three daughters, a son-in-law, a grandchild, and a plaque listing the five infants who died, four of whom were sons. The early deaths included their first three children. His wife’s illness is mentioned in Bartlett, Rimmer, 22; William Rimmer’s manuscript, “Stephen and Phillip,” 252, Boston Medical Library, Boston, MA; and an inscribed, 1868 parlor sketch of her and daughter Adeline, Rimmer Commonplace Book, Boston Medical Library. Their daughter Caroline added a note that it was done “after one of her severe illnesses.” She survived her husband and died in 1885 at age 61 of “kidney disease.” See “Massachusetts Deaths, 1841–1915,” database with images, Family Search.org.

28 On unevenness and the centrality of home life, even before marriage, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 4, 16, 18, 130–31. He cites elsewhere Rimmer’s refusal of a trip abroad as a gift because it would entail an embarrassing obligation and leaving his family (88). On Hunt and Rimmer, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 80. Given their combined ability, Hunt even proposed, more than once, that they open a school together (79). Hunt’s attempt to obtain Rimmer’s collaboration on murals for the New York State Capitol at Albany failed when he disagreed with Rimmer’s criticisms. On this, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 78.

29 James Elliot Cabot, a philosopher and amateur artist who attended Rimmer’s lectures, wrote an introduction to Rimmer’s first book and possibly subsidized it. He promoted its adoption in elementary schools. See Cabot in William Rimmer, The Elements of Design (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1864), 8. Also see Cabot in Bartlett, Rimmer, 43–44. The Transcendentalist, poet and artist Caroline Sturgis (Mrs. William A. Tappan) paid to have Rimmer’s second book published. See Bartlett, Rimmer, 85. A revised second edition of the first book, including a new section on form (based on Art Anatomy), was published in 1879 as Elements of Design in Six Parts.

30 While the original volume was consulted, the edition used in this book is William Rimmer, Art Anatomy, with an introduction by Robert Hutchison (New York: Dover Publications, 1962), an unabridged but slightly revised republication of the 1877 edition. For some skulls, Rimmer reports (21) using the Museum of Natural History, Boston. In analyzing character as revealed in physiognomy, he admitted it was not a science (62) but remained a man of his time in acting as though it was.

The original volume — Dr. William Rimmer, Art Anatomy (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1877) — is large as if it were meant to be a display item or a work of art in itself. The 1962 text is the same but with rare one-line deletions concerning minority groups, such as, on page 22, regarding faces, “the appetites and sensibilities find strongest expression in the dark skinned races.” For more on the context for the book, see Elliot Bostwick Davis, “William Rimmer’s Art Anatomy and Charles Darwin’s Theories of Evolution,” Master Drawings 40 (Winter 2002): 345–59, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1554563. The inclusion of facial expression, and its analysis, is unlike the contents of contemporary manuals on art anatomy. His competition was chiefly Henry Warren’s Artistic Anatomy of the Human Figure (London: Winsor and Newton) which is a book of skeletons and bones which was issued in a fourteenth edition in 1873. This book recommends the “antique statues” as the best models (8).

31 Anon., “Art Anatomy,” The Nation, A Weekly Journal Devoted to Politics, Literature, Science, and Art 24 (September 8, 1877): 157. The 1877 edition of 50 copies did not meet the demand, but a fire destroyed the plates in 1879, so a new edition was created in 1894 and republished thereafter. For this, see Anon., “News of the Fine Arts,” The New York Times, May 28, 1894, 3.

32 Bartlett, Rimmer, 41.

33 His procedure is described in Smith, “Dr. Rimmer,” 200.

34 On his drawings and their erasure, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 141. For painful, see Smith, “Dr. Rimmer,” 201.

35 On destruction, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 18, 50, 128, 351 (quote).

36 These include the following pictures in the 1985 Rimmer exhibition catalogue: Ebenezer K. Alden (Mead Art Museum); Mrs. Howland (Private Collection); A Riderless War Horse (Private Collection); and Sunset / Contemplation (Manoogian Collection). Learning that Lincoln Kirstein sought works by Rimmer, the owner of Mrs. Howland produced it as by him, claiming there was once a signed, companion portrait of a Dr. Howland. No such second portrait existed. The Pilgrim John Howland Society recently found, in its genealogical records, no American “Dr. Howland” of about the date of the supposed wife. There was also a fraudulent label involved. See the correspondence over the two Howland portraits in box 1, Kirstein and Nutt Research Material, Archives of American Art. Once the Howland portrait gained acceptance, the Alden portrait could be added as similar in style. In the most obvious difference, both are too sharply defined with darker shading than can be found in documented work by Rimmer. A third portrait, The Reverend Calvin Hitchcock (Fogg Museum), related to these, has also been wrongly assigned to Rimmer. Richard Sherman Nutt attributed the War Horse to Rimmer, but Rimmer did not draw horses like this (his were fairly standard as they were from memory), and the use of a dry brush is atypical. For Nutt’s role, see Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 2:516. The landscape, Sunset / Contemplation, serving as the catalogue’s cover illustration, has a forged signature with a fake date and appears to be one of several replicas by the Danish artist Hans J. Hammer of his A Square in Ariccia, Italy, after Sunset (1862; National Gallery of Denmark). Other misattributions, most of which are online, are too numerous to be addressed in a note.

37 Benjamin Champney, Sixty Years’ Memories of Art and Artists (Woburn, MA: [Privately Printed], 1900), 11.

38 David Tatham, “The Lithographic Workshop, 1825–50,” in Georgia Brady Barnhill, Diana Korzenik, and Caroline F. Sloat, ed., The Cultivation of Artists in Nineteenth-Century America (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 1997), 46.

39 Champney, Sixty Years, 11. One of Rimmer’s paintings that had the general look of a Baroque master dates from about twenty years later: his small Crucifixion (lost), ca. 1855, painted for Father John T. Roddan of St. Mary Parish, Randolph, MA. See Bartlett, Rimmer, 19 and ill. no. 14.

40 Bartlett, Rimmer, 8.

41 On singing and the fire engine company, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 9–10. Rimmer’s name as artist is inscribed on several known copies of this print. See Weidman, et al., Rimmer, no. 79.

42 Bartlett, Rimmer, 10.

43 Ibid., 8–9.

44 Another copy, in reverse, is Rimmer’s The Entombment (Worcester Art Museum) which can be identified as after Guercino’s The Dead Christ Mourned by Two Angels (National Gallery, London) from about 1617–18. This tiny lithograph has a pencil inscription, outside the image, with Rimmer’s name (misspelled) and a wrong 1845 date. Embracing mythical subjects, Rimmer also produced a lithograph of Venus, in oddly original boudoir surroundings, as Reclining Female Nude (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Kirstein concluded that it is an “allegory of luxury,” but, with a dog (traditional symbol of loyalty) included at lower left, it is more likely an allegory of faithfulness and lust. Caroline Rimmer dated it in the late 1850s, which is believable. See Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 3:769–771. Bartlett calls Rimmer’s lithograph, The Hunter’s Dog (Bartlett, Rimmer, 124 and ill. no. 10), which is a lost work, a “copy from a lithograph” but does not identify a source. It appears instead to be an original composition, showing a loyal dog protecting his dead owner, done in the manner of the English artist, Edwin Landseer, who was famous at mid-century.

45 For the passing reference to a banished lord, see Thomas Warton, The Pleasures of Melancholy; A Poem (London: for R. Dodsley, sold by M. Cooper, 1747), 18. On Reynolds and the print versions, see Martin Postle in David Mannings, Sir Joshua Reynolds: A Complete Catalogue of His Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 1:509-10. Perhaps relatedly, Rimmer’s friend, Stephen H. Perkins, owned an oil copy (lost) of the Reynolds (509).

46 Bartlett, Rimmer, 21–22.

47 Bartlett, Rimmer, 24, reported that Rimmer received a diploma from the Suffolk County Medical Society. Kirstein, “Rimmer: His Life,” 688, claimed that he had been issued a license by the same, but there is no record of either. On the lack of licenses, see Philip Cash’s essay in Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 25.

48 Bartlett, Rimmer, 25 (quote), 35. The 1863 date is given in his obituaries, such as Anon., “Dr. William Rimmer,” Boston Daily Advertiser, August 22, 1879, [1]. It was probably not an abrupt ending, and he continued as an occasional doctor. In the Massachusetts State Census of 1865 and the United States Federal Census of 1870, his occupation is listed as physician. According to Bartlett, Rimmer, 37, he continued to attend Stephen Perkins as his doctor. Perkins died in 1877. Rimmer might also have long been a bootmaker as he is listed in the United States Federal Census of 1850. In 1877, he wrote of teaching at the Boston Museum as only “one of my means of procuring a livelihood.” On this, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 91–92.

49 Schools advertised his instruction as scientific, and some of his students studied surgery. For this, see Anon., “The Establishment of the Art School,” Boston Daily Advertiser, February 17, 1864, 2. For the quote, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 143.

50 Bartlett, Rimmer, 95. He was slender and 5 feet, 10 inches.

51 For swings between arrogant and humble, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 11, 28. He reported about but was unable to identify Rimmer’s mental illness.

52 The middle initial appears on the birth certificates of Adeline (1849) and Caroline (1851) as well as on the death certificate of Thomas (1843). See the digital images under the online database Family Search.org.

53 See Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 49, 257, 263, 275, where Stephen and Phillip are projections of Rimmer. For Phillip cast out for lack of charity, see ibid., 105, 115, 117, 119, and 214. He is to assume flesh and experience what it is like to be on the other side of his condemnation (103). In a vision, a group of angels tell Rimmer that he should accompany Phillip and learn with him (137). Like Phillip, Rimmer could be a severe critic of others, but he also realized that he could be unjust. For this, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 140, and Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 137. Through his pain, Stephen teaches them both pity (ibid., 167, 177, 209). For Phillip as a lion, see ibid., 139, 279. Rimmer’s manuscript is partially paginated with numerical gaps that can be filled from his pagination. With regard to dating his much-rewritten manuscript, Rimmer was working on it at least in 1869, the date of the drawing of Phillip, and in his final days in 1879, according to his daughter’s note on the first page. Kirstein, “Dr. Rimmer?” 133, dates the manuscript as 1855–1879, without explanation for the first date. Most, if not all, of it was probably written during the decade after 1869. On the problem of dating it, see Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 1:83–84n. His daughter, Caroline, hoped to publish parts of the manuscript with a biography of Rimmer. She wrote of this to the playwright and friend of her father, James Steele MacKaye. No response is known. See her letter, February 19, 1914, James Steele MacKaye Papers, box 40, folder 10, Special Collections, Rauner Library, Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H.

54 Bartlett, Rimmer, 95.

55 For the quote, see Dante Alighieri, Dante, translated by Ichabod Charles Wright (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman, 1845) 1:10. The reference, in this translation, is to line 45 of the first canto of the Inferno. A second drawing of the same scene, with the same date, is at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford.

56 For son, see “Stephen and Phillip,” 203. For roar, see ibid., 35.

57 Boston had such a menagerie, beginning in 1835. See Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 1:374n.

58 The “uplifted mane” is mentioned in Rimmer’s description of Phillip in “Stephen and Phillip,” 155. For glowing, see Rimmer, ibid., 153.

59 On visions, for instance, see Rimmer in his “Stephen and Phillip,” 45, describing a vision in which he stands before the gate of Heaven.

60 Ferdinand Christian Baur, Paul: The Apostle of Jesus Christ, His Life and Work, His Epistles and His Doctrine. A Contribution to a Critical History of Primitive Christianity, translated by Eduard Zeller and revised by A. Menzies, 2nd ed. (London: Williams and Norgate, 1876), 1:60. The first edition is 1845.

61 For an example of their debating, see Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 349. For the debating society, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 21.

62 Rimmer seems to have understood the term “demon” in the same way that the Transcendentalist Amos Bronson Alcott did as a “lapsed or divided soul,” not pure evil. See Alcott’s Diary for 1849, Volume 23, January, p. 12, Amos Bronson Alcott Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

63 For Stephen as both demon and angel, see “Stephen and Phillip,” 49, 50. For a demon from Hell, see ibid., 40, 49, 78, 209, 211–19, 239–49. See ibid., 45–49, for Rimmer fighting a demonic, hateful and suicidal Stephen as part of himself. See ibid., 74, for Stephen’s “despairing memories.” See ibid., 217, for Stephen and Rimmer sharing guilt. See ibid., 261, for Stephen’s conversion and worship of God. For Stephen advocating for compassion, see ibid., 79, 218, 261, 265. Rimmer’s interest in St. Stephen is also evinced in his undated drawing, The Stoning of St. Stephen (unlocated), which descended from his sister’s daughter. See Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 3:744–47; and Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 39, ill. 5.

See Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 5, for a different opinion on “Stephen and Phillip.” He views the manuscript as representing Rimmer’s “relationship with his father, as embodied in two angels, Stephen and Phillip, who symbolize respectively the light and dark aspects of the soul, initially at odds and separated but eventually reconciled.” Certainly Stephen, once described as “filthy rat” (235) and a soul “in hell” (263), is not initially — if at all — the light aspect of the soul. He too could take the form of a beast. Rimmer’s father is never mentioned in the legible text, but Rimmer does once indirectly associate Phillip with him or with his heritage through the words: “son of a great king” (203). Both Kirstein and Weidman read “Stephen and Phillip,” but Kirstein never advanced far with his intended book on Rimmer, while Weidman’s interpretation appeared in published form in his dissertation and exhibition catalogue.

64 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 123.

65 Kay Redfield Jamison, Touched with Fire: Manic Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament (New York: The Free Press, 1993), 17.

66 For Rimmer as a manic depressive, or bipolar, artist, see Diane Chalmers Johnson, American Symbolist Art, Nineteenth-Century “Poets in Paint:” Washington Allston, John La Farge, William Rimmer, George Inness, and Albert Pinkham Ryder (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press, 2004), 48, who deduces his illness, in passing, as a fact; and Dorinda Evans’ discussion of him in a manic depressive context in Gilbert Stuart and the Impact of Manic Depression (Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2013), 140–45, 147, 150–52, 156–57, 160–61. Others perceived Rimmer as having a “split personality.” For this, see Barbara B. Millhouse and Robert Workman, American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House Museum of American Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 80. Contradictory opinions on Rimmer’s character and personality are documented in Bartlett, Rimmer, 133–47. For the quote, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 16. Bartlett had access to more primary information on him, in the form of a diary or diaries, than is available today, but he decided that “many facts of interest and importance, proper to be stated in another generation, cannot now be appropriately recorded” (vii).

67 See the quote in Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 26–27.

68 Ibid., 15, for his fluctuation between mad and melancholy.

69 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 29.

70 Ibid., 73.

71 For house, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 20.

72 Bartlett, Rimmer, 89.

73 Bartlett, Rimmer, 138, 16 (quote).

74 Jamison, Touched with Fire, 105–13.

75 Bartlett, Rimmer, 71.

76 Ibid., 104.

77 Jamison, Touched with Fire, 107, 110–11.

78 An 1871 lecture summarized in Bartlett, Rimmer, 68–69.

79 Perkins’ letter of September 9, 1863, pp. 4, 2, to Rimmer, Boston Medical Library. The expression is put in quotes as if a quotation from Rimmer himself.

80 Bartlett, Rimmer, 142, 37 (quote), 131 (quote), 135.

81 Marion MacLean’s notes in “Research File: Marion MacLean Undated and 1895,” box 1, p. 36, Kirstein and Nutt Research Material, Archives of American Art.

82 Bartlett, Rimmer, 135. See the description of the illness in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Revision. On the irritable state, see Jamison, Touched with Fire, 28, 39, 154.

83 For an unusual shift in handwriting, see Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 15, 38, 101, 236, 238, 312, 363, 383. The last five pages, and pages 353–55, contain indecipherable scribbling.

84 See Jamison, Touched with Fire, 29, 109–12, on grandiosity.

85 Lapthorn, “Stories and Memoirs,” 5. Bartlett, Rimmer, 1–2, generally agrees with this but does not realize his claim was as the dauphin and that he visited France. Kirstein, who heard from relatives, says Thomas was “educated like a prince” in England in a South Lancashire yeoman family called Rimmer. He was “supported by the purses of the British and Russian crowns” with the intention of returning him to France. But these two sponsors, when Thomas was age twenty in 1815, decided instead to back the last king’s brother, as King Louis XVIII, rather than his son. See Kirstein, “Rimmer: His Life,” 686. The family story that Thomas became a British army officer (Bartlett, Rimmer, 2; Lapthorn, 5) is unsupported by records.

86 Kirstein, “Rimmer: His Life,” 689. Kirstein reports that an attendant “nurse” described his death this way to Thomas’ granddaughter (unidentified). He called him “embittered to the point of derangement” (ibid., 687).

87 See her signed death certificate, June 22, 1891, in “Massachusetts Deaths and Burials, 1795–1910,” image 304 of 1536, database Family Search.org.

88 Kirstein, “Rimmer: His Life,” 687. See “Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988”, for Thomas Rimmer, August 3, 1852, no. 1985. His place of death is “Ho. Industry” in Boston, and the informant: “F. Crane.” See the photographic image on Ancestry.com. “Friend Crane,” probably a Quaker, was superintendent of the House of Industry. For this, see The Directory of the City of Boston … from July, 1850, to July, 1851 (Boston: George Adams, 1850) 126. Thomas Rimmer is listed in the Boston directories from 1825 to 1847. For this, see the Kirstein and Nutt Research Material, box 1, folder: “Biographical Material,” Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C. The burial site for Thomas is not known.

89 On disorderly conduct and confinement in the House of Industry, see The Revised Statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Passed November 4, 1835 … (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, 1836), 779, sec. 6. Usually the sentence was for a few months, but repeated offenses resulted in longer terms. No liquor was allowed, and a hospital adjoined the facility. Thomas was hot tempered and capable of fighting a man publicly over a flute that he would not return (Bartlett, Rimmer, 5). The annual reports (Boston City Archives) give little sense of inmate conditions, but the size of the House of Industry increased to over 600 inmates of both sexes during the years he could have been there. See Annual Report of the Directors of the Houses of Industry and Reformation for the Year 1852–53 (Boston: J.H. Eastburn, 1853), 16.

90 The canvas stamp is changed to allow the building number to be written in as 17 which was Morris’s address from 1849 to 1850. See Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 2:465–68.

91 For favorite, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 95.

92 For Cupid characterized this way, see, for instance, Vincent Bourne, The Poetical Works, Latin and English, of Vincent Bourne (Cambridge [England]: printed for W.P. Grant, 1838), 96, 119.

93 For the usual staff, see William Hamilton’s Prospero and Ariel, 1797 (Old National Gallery, Berlin). Rimmer also made a drawing that appears to show Prospero and Ariel with the sleeping travelers (not a scene in The Tempest but easily imagined). Ariel holds his pipe and seems to have just made himself visible, while Prospero looms phantom-like over the sleepers. See the Rimmer Sketchbook, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Boston, MA.

94 His use of a single, flourishing plant next to a foreground hand in the drawing, A Dead Soldier (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), supports this point. In a cropped, ground-level view of a battlefield with a dead man, a startling additional hand on the ground — as if the viewer’s — has the wrist arched and a symbolic, adjacent plant as the only indications of life. This is a highly original image, akin to but unlike the famous photographs of the Civil War dead.

95 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 33.

96 Laurence Sterne, The Sermons of Mr. Yorick (London: J. Dodsley, 1767), 2:134–35.

97 Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 95.

98 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 265, 269, 383.

99 Newspaper Clipping Scrapbook of Mary H. C. Rimmer, Boston Medical Library.

100 Lapthorn, “Stories and Memoirs,” 6–7.

101 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 55–57.

102 Bartlett, Rimmer, 59. New York was much more of an art center, with receptions and exhibitions, than Boston by 1860. For this, see Neil Harris, The Artist in American Society: The Formative Years, 1790–1860 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 266.

103 Warton, Pleasures, 9, 18 (quote).

104 Bartlett, Rimmer, 22, 25.

105 Lapthorn, “Stories and Memoirs,” 6–7. See note 15 for the dauphin claim.

106 The first quote is from an obituary clipping, [Boston] Evening Transcript, August 22, 1879, box with bar code: 3-1027-00033-7440, Kirstein and Nutt Research Material, Archives of American Art. The second quote is from Caroline Rimmer’s letter to Truman Bartlett, January 3, 1882, in the same box.