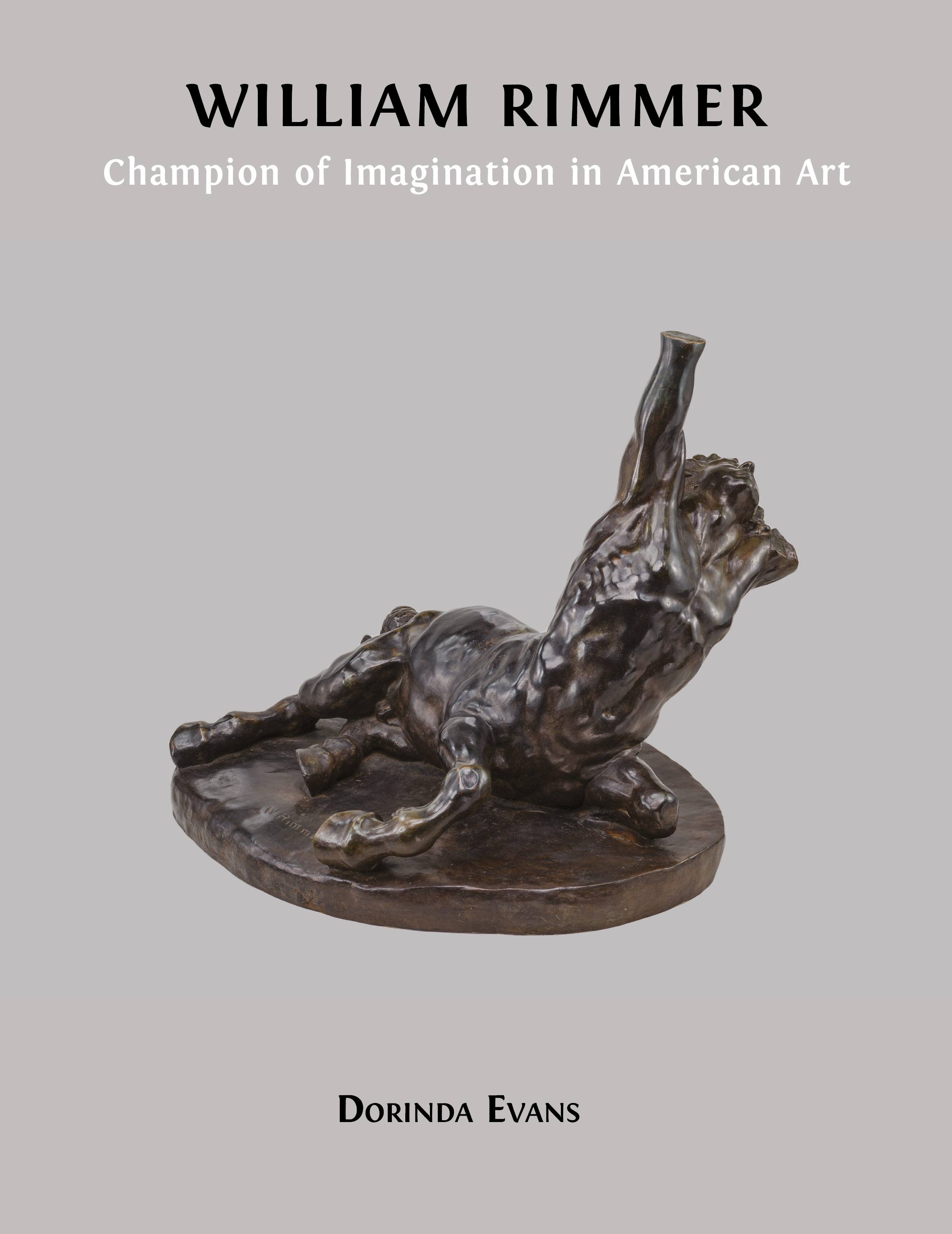

3. Self-Expression in Flight and Pursuit

© 2022 Dorinda Evans, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0304.03

William Rimmer’s Flight and Pursuit (fig. 37), signed and dated 1872, has been the cause of considerable scholarly debate since the 1980s. After entering a public collection, it appeared in American art surveys as well as a major exhibition, but there has rarely been agreement on the subject, which is not immediately evident.1 This attention is not misplaced: the picture has been treated in different ways as a rich encapsulation of Rimmer’s concerns as an artist.

Fig. 37 Flight and Pursuit, 1872. Oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 26 ¼ in (46.00 x 66.70 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of Miss Edith Nichols, 1956. Photograph © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

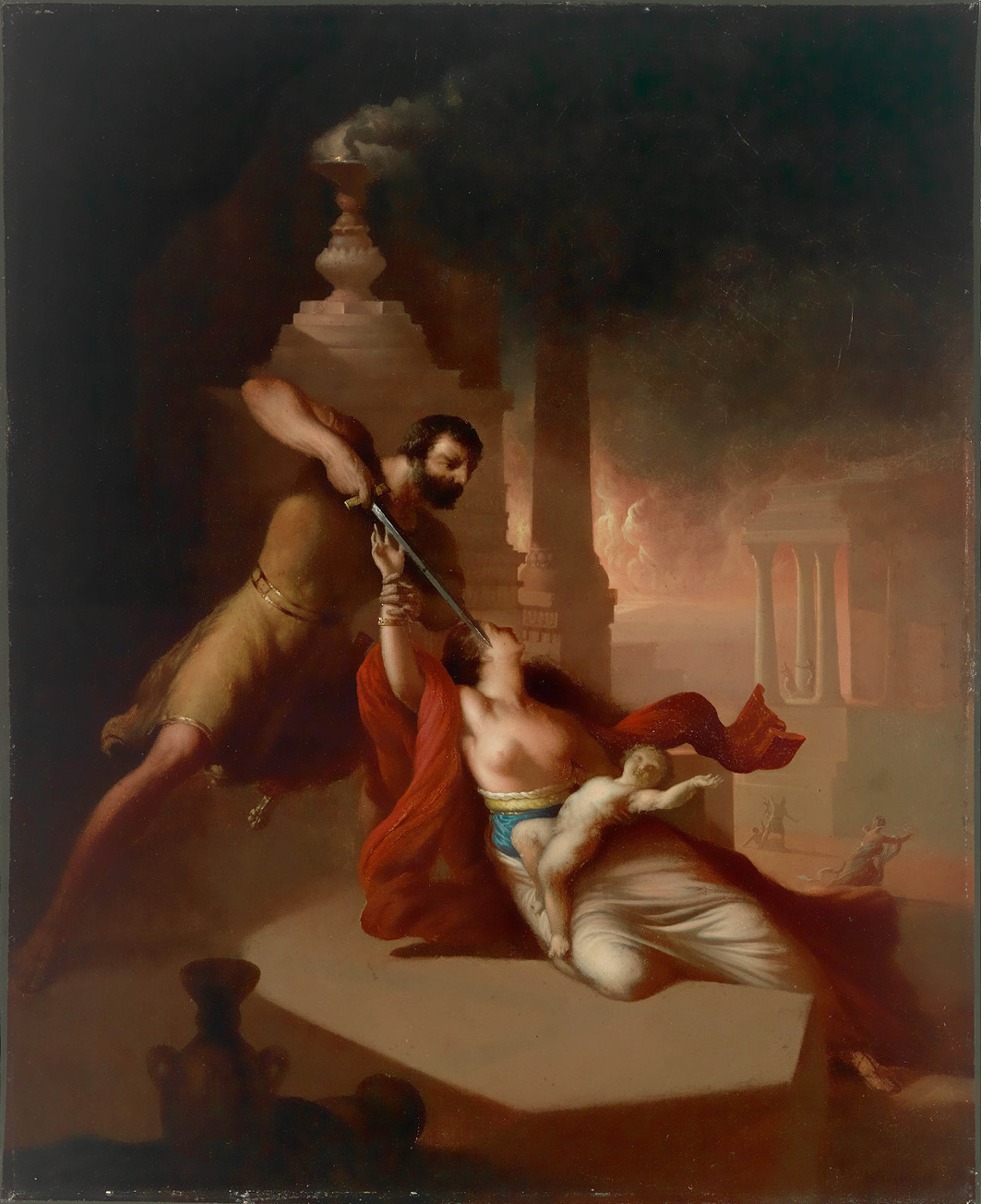

Within an exotic interior, a terrified man wearing a dagger is chased by a nearly identical figure wielding a saber. The hint of violence — imminent or recently-committed — makes the scene sensational. Wholly different historical contexts have been constructed to provide content for the picture. These include allusions to the 1866 capture of John Surratt, a conspirator in President Lincoln’s assassination; the 1811 massacre of the Mameluke warriors by the Turkish Pasha Mohammed Ali; the biblical conspirators against King Solomon, fleeing to the holy altar for safety; and the pre-Civil War pursuit of American fugitive slaves.2

In these responses, the vaporous quality of the second figure — readable as a spirit — is usually overlooked. But it is so extraordinary that it must be at the heart of a quite specific interpretation. Even the latest reading diminishes the salience of this peculiarity and, in a surprising compromise, sees the picture’s historical content as open-ended, or “left to the viewer’s imagination.”3

A compelling argument can be made that the subject’s earliest identification is, for the most part, what the artist intended. After discussing the painting with the daughter of its first owner (one of Rimmer’s closest friends), the art connoisseur Lincoln Kirstein, in 1946, called it an allegory of “man and his conscience.”4 But, in an elaboration, presumably influenced by his Harvard education, he claimed that the depiction referred to the enigmatic poem “Brahma” by Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of Harvard’s most distinguished graduates.5 This short piece, which Kirstein quotes, concerns a Hindu god’s abstruse reflection on his own nature. Since there is no visual tie, the Emerson connection led to skepticism and it is now generally deemed “tenuous at best.”6 This might not be grounds, however, for entirely discarding an explanation that can be linked through the first owner to Rimmer. Arguably the scene’s intended meaning is most convincing as an allegory of guilt or of man’s conscience in a state of sin.

With his students, Rimmer expressed a preference for the portrayal of what is timeless and universal — “the intellectual or moral condition of things.”7 This jibes well with a reinterpretation of the picture as epitomizing the conflict between a sinner and his moral sense, or conscience. The theme of conscience fits all the visual details of the scene as well as what is known of the artist and his preoccupations.8 Furthermore, it echoes the tenor of Rimmer’s private, surviving writings about imagined situations and himself. They reveal a troubled man, accustomed to self-flagellation over both perceived and imagined moral failings.9

More than has been realized, Rimmer was an artist with a mystical sensibility who not only wrote but also tended to paint from his innermost thoughts and feelings. His private life and his work were closely entwined, and inevitably so. He created mostly for himself and obtained commissions for less than a quarter of his work.10 Although traditional interpretations of Flight and Pursuit have generally favored an historical or literary explanation, the essence of the picture is convincing as much more personal. Yet it is abstracted or expressed in universal terms.

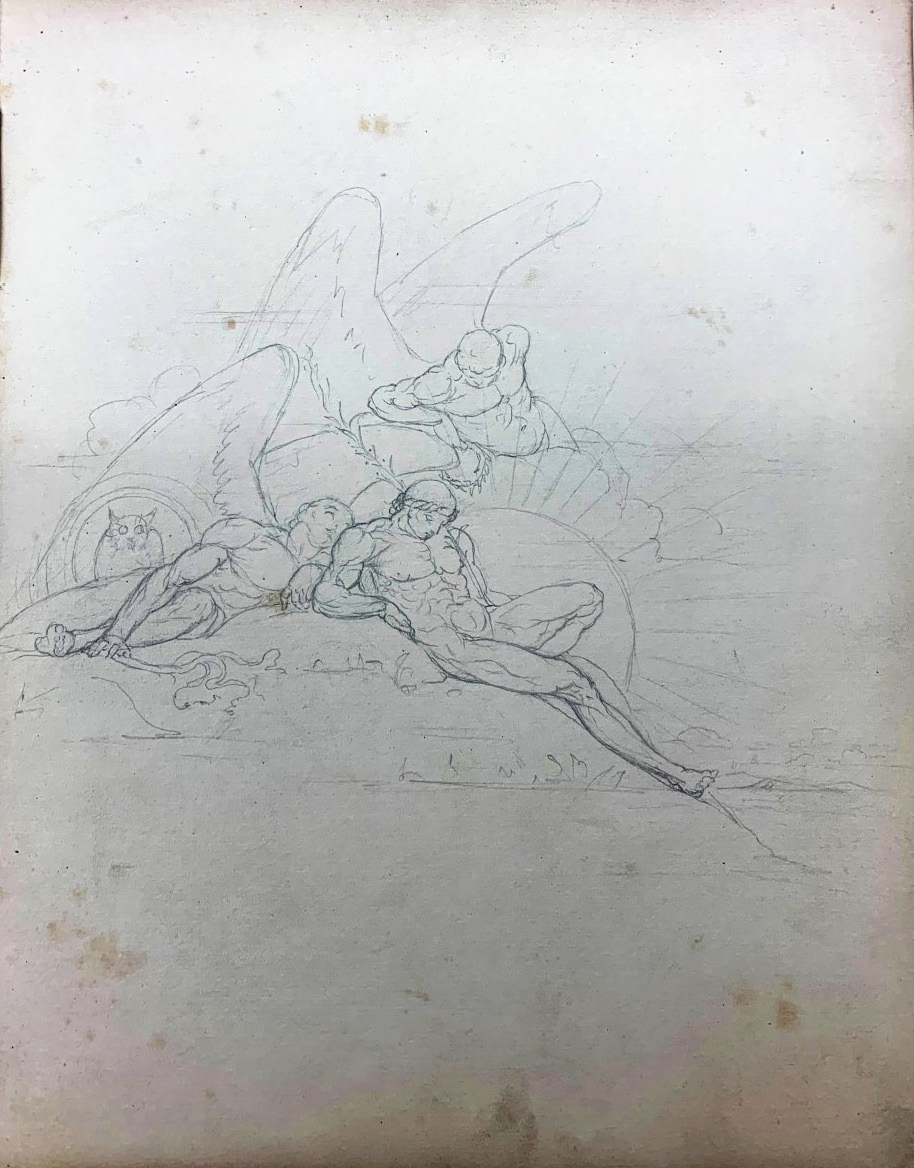

Fortunately, a preliminary drawing for the foreground figure (fig. 38) in Flight and Pursuit survives and is partially identified by the artist’s label: “oh for the horns of the Altar.”11 This inscription, referring to the Bible, corroborates other evidence that Rimmer favored biblical subjects. Reportedly, he had a “great love for the Bible” as apparently a source of moral inspiration rather than of literal truth.12 Along with the prominent, waistband knife, the inscription helps to establish the first man in the painting as a sinner whose offences include homicide. In fact, for greater emphasis, the one knife becomes two in the drawing. As recounted in 1 Kings 1:50–53 and 2:28–34, egregious offenders (in the first case, a usurper king; in the second, a double murderer) of the kings of Israel could obtain sanctuary by grasping the horns on the four corners of a special altar.13 In a telling distinction, however, Rimmer’s drawing inscription provides the sinner’s thinking, and it is not actually a biblical quotation.

Fig. 38 Oh, for the Horns of the Altar, 1872 or before. Pencil on paper, 11 4/5 x 14 ½ in (30.20 x 36.85 cm). Cushing / Whitney Medical Library, Yale University

Likewise, the strange figure (fig. 39) following the foreground man in the painting is not biblically based, indicating that the entire image deviates from the Bible. This second man is so thinly painted that he has a barely discernable face but what can be seen are his large eyes trained on the first runner. In contrast to the more strongly colored and highly modeled foreground man, the peculiar transparency of this figure transports him out of the real world. Breaking this contrast, the lower-body posture of each man mysteriously duplicates that of the other.

Fig. 39 Flight and Pursuit (detail), 1872

Through the coupling of these figures, the scene encompasses two aspects of a single person — the foreground self, in his state of sin, and, behind him, his higher nature — higher in the sense of the personification (as Kirstein saw it) of a conscience. As the picture makes clear, this Conscience, as a phantom pursuer, is first and foremost an inescapable avenger, from whom the wrongdoer will never be free. Accordingly, the temple altar, indicated by the smoke of a burnt offering at the left edge, and its horns will be of no avail. There is no safe refuge, and this is really the point. The inclusion of this sanctuary of last resort even in the drawing’s inscription means that, from the beginning, the emphasis was on the utter hopelessness of the sinner’s plight. Rather than providing rescue, the altar gives credence, if need be, to Rimmer’s known lack of respect for “priestcraft for its own sake.”14

Adding to the effect of absolute terror before a spiritual manifestation, an ominous shadow appears on the floor at the right, forked to suggest possibly two people. They do not enter the chase (contrary to some readings) but, instead, remain upright and stationary.15 That is, they appear to threaten by being ever present as if they were a haunting memory, such as unforgettable victims. Like Conscience, they can be understood as part of the mind of the apparent assassin.

Rimmer’s soul-baring, self-referential narrative, “Stephen and Phillip,” written mostly during the 1870s, is not only an extraordinary resource for understanding Rimmer and his work, but also it has special relevancy with regard to Flight and Pursuit. One of the recurrent themes is the culpability of the artist and of his imaginary companions — Stephen and Phillip (aspects of himself) — for various sins. These range from hard-heartedness to outright murder in an impulsive response to villainy.16 A crucial passage, suggestive of Rimmer’s thinking with regard to Flight and Pursuit, is where Rimmer cries out: “Alas! For adulterers and thieves and murderers. Oh, who can fancy the shadows that follow them?” Then he describes the shadows’ occupants, as if from this image where the recently deceased might inhabit the pool of darkness at the right: “Things of another world (Foul like themselves) on whom corruption hangs from their graves.”17 In a further connection, he speaks of imagined scenes that, like the painting, have historical, Middle Eastern settings, such as Babylon’s towers or Nineveh’s gates.18

At another point in the manuscript, “Conscience” appears in human form, embodied as a female beggar who tests the generosity of the disparate people she meets by asking for a piece of bread.19 In his vivid imagination, Rimmer conceived of Conscience as capable of assuming different forms in relation to a person, as an interior or exterior being. His own conscience within him, for example, trembles as it is attacked by demon claws, and Stephen, acting as an external conscience, whispers — albeit unsuccessfully — in the ear of an evildoer.20 The existence of a conscience was so consequential to Rimmer that he even included it in a rambling, art lecture that incorporated a reference to religious viewpoint.21

More personally, Rimmer writes in his text of feelings of his own guilt. He cites related, internal “whirling” and being “haunted by evil thoughts,” which include the patently erotic. He describes himself as essentially “a sinner in sad remorse,” and his recurring concern is the separation of what is morally right and wrong.22 Ashamed of a tendency to be uncharitable that became exaggerated in his mind, he could identify with sinners (despite his abhorrence of all things evil) and agonize over their moral predicament and prospect of eternal suffering.23 For him, it is the unseen world, and its meaning, that is all important.24

Rimmer’s personal torment and excessive feelings of guilt surely stemmed, in whole or part, from his mental illness. As his belabored, over-written text shows, he could become obsessed with a sense of worthlessness and overwhelming, inappropriate guilt. This preoccupation is a characteristic symptom of manic depression.25 Not only did his unpredictable mood shifts make him inconsiderate and unable to fulfill commitments — such as his scheduled lectures — but also, more painfully, he suffered from frightening, illness-related imaginings of wrongdoing by himself and others that he could not control.26

Having seen the “Stephen and Phillip” narrative, Kirstein called Rimmer a “Transcendentalist Christian.”27 His predecessor, Truman Bartlett, knew of the manuscript’s existence but had not read it. Writing in 1881 from the reminiscences of others and at least one of Rimmer’s now-missing diaries, he came to a different conclusion. He characterized the artist as an independent thinker, not affiliated with any particular philosophy or religious denomination.28 This is somewhat misleading. Despite his independence, Rimmer did adopt parts of the religious teachings of others.

For instance, he was partially influenced by the philosophy of Transcendentalism promoted by Emerson, whom he knew.29 In the manuscript, man’s conscience (akin to Emerson’s “over-soul”) transcends experience and is therefore the best guide to divine truth. Most crucially, in the manner of a Christian and a Transcendentalist, Rimmer writes revealingly of his absolute certainty of the existence of an inner God that is in everyone “innocent or guilty.”30 A conscience (not differentiated from soul) is not only an inner divine presence, but, according to Rimmer, it also has many abstract manifestations or “modes.” These include instinct, faith, hope, and “the moral sense in everything.”31

Adding another dimension, showing the independence that Bartlett perceived, Rimmer, as a questioning Christian, complains repeatedly in the text about “Darwinite Christians” whose stated beliefs adhere too closely to the theories of Charles Darwin.32 Significantly, it was Darwin who, in his 1871 Descent of Man, claimed the conscience evolved from social instincts, such as sympathy. Such thinking erases the possibility of God’s participation, which was important to Rimmer, and undermines the concept of the immortality of the soul or conscience.33 Rimmer’s few, passing mentions of Darwin are expressive of frustration. He accepted progressive evolution from a prehistoric reptilian world but believed in the involvement of God and in the soul’s immortality.34

Flight and Pursuit does not have an obvious precedent or progeny, but it shares a visual and ideological kinship with a few disparate images, all rare and all from the nineteenth century.35 Not coincidentally, this is considered a time of increased interest internationally in a person’s conscience and in the moral obligations of civilized society.36 Within the United States, the authority of the church and Bible between 1830 and 1870 even began to be supplanted by the supremacy of a private conscience.37 Closer to the artist and reflecting his social milieu, Rimmer’s influential contemporary, Emerson, played a role in this development by going so far as to champion the conscience as the highest law, the “magnetic needle” for an individual’s proper moral path.38

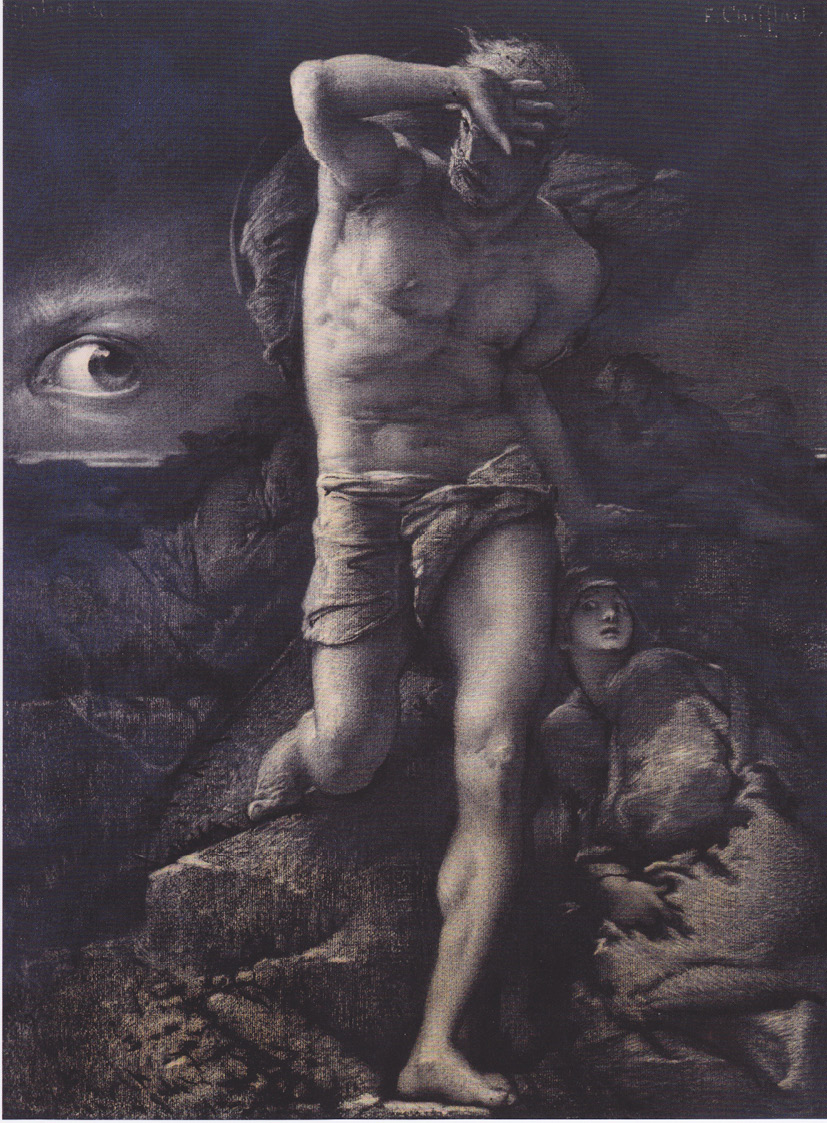

In a related French depiction from 1877, Nicolas-François Chifflart’s The Conscience (fig. 40), Conscience appears as an external apparition, but not a personification.39 Illustrating an eponymous poem by Victor Hugo, this Conscience is a mammoth, floating eye that, after the death of the biblical Abel, relentlessly follows his brother-slayer, Cain, and Cain’s family. Alarming and large as the eye is, only Cain can see it. While Rimmer’s unearthly Conscience carries a sword as an identifying emblem, the monstrousness of Chifflart’s incarnation needs no embellishment. It is sufficient, without weapon, to symbolize the horrific aspects of a guilt-ridden, accusatory conscience.

Fig. 40 Nicolas-François Chifflart, The Conscience, 1877. Charcoal on paper, 22 3/10 x 16 3/10 in (56.7 x 41.4 cm). Maison de Victor Hugo, Paris. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chifflart_-_Das_Gewissen_-_1877.

Rimmer’s threatening sword draws on literary references to a conscience as pricking or stabbing with guilt. A precedent can be found, among other sources, in two famous plays by William Shakespeare and a Catholic edition of the Bible. In Henry VIII (Act 2, Scene 4, line 1542), the king’s conscience endures a “prick” followed by a “splitting power” (line 1554). In Richard III (Act 5, Scene 2, line 17), “every man’s conscience is a thousand swords.” In a stronger connection, Proverbs 12:18 refers to being “pricked” by the very “sword of conscience” (Douay-Rheims Bible). With sources such as these, the expression “the sword of conscience,” meaning acute self-reproach, was not only recognized but also employed by the American public of the mid-nineteenth century.40 Use of the phrase apparently even increased somewhat during Rimmer’s lifetime.41 In a violent situation involving a knife, the countering threat of a long sword, taken from a contemporary expression, might be particularly apt as an accompaniment of a newly conceived Conscience.

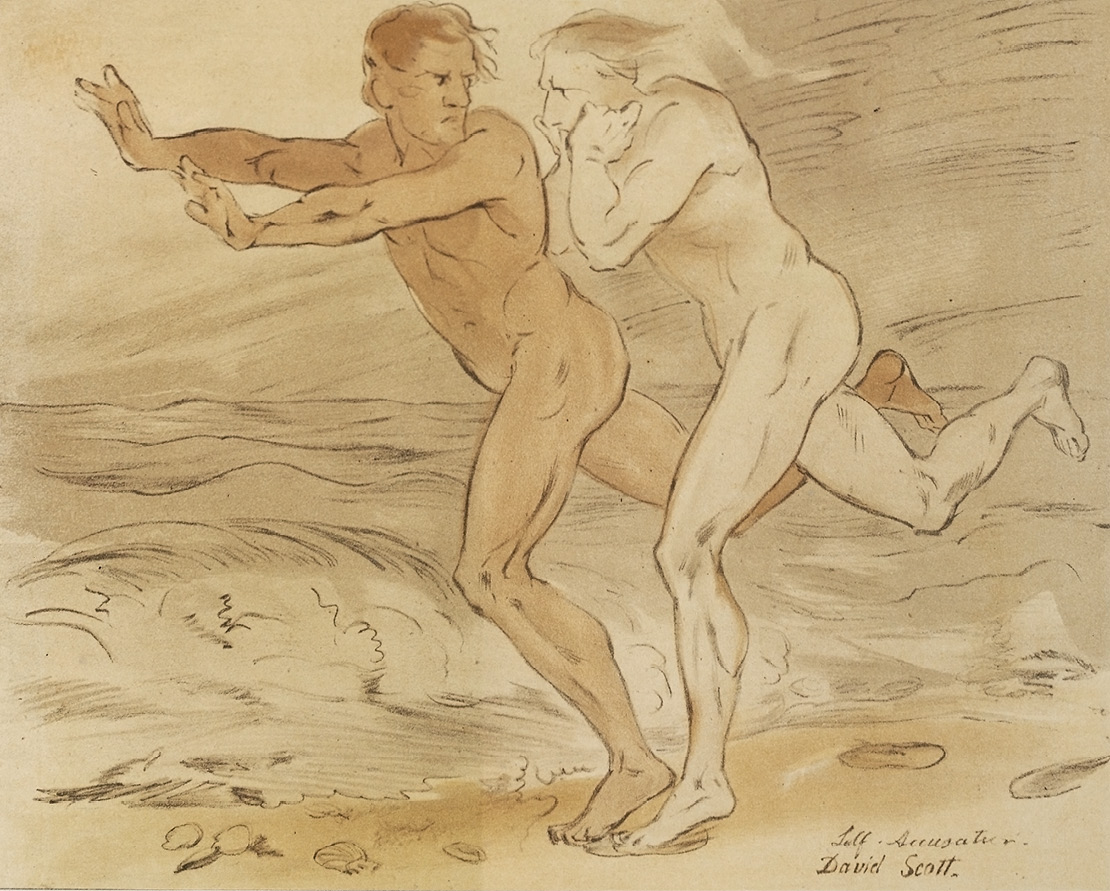

In the closest approximation, the Scottish artist, David Scott, used a phantom-like personification of a conscience — but not transparent — in an undated watercolor (unlocated) that was based on a quick sketch from 1841 (Scottish National Gallery). After his death, the watercolor appeared as a lithographic book plate in 1884 (fig. 41). Kirstein kept a photograph of the lithograph in his files, pasted in a research scrapbook next to his photograph of Flight and Pursuit.42 The book plate, inscribed Self-Accusation, shows two naked men running along a stormy shoreline. The one in front, ruddy-colored as a living person, is annoyed by the pale, near-double of himself who races with him, setting his feet in his footprints and his elbows on either side of him so that, as they move, they are uncomfortably engaged. The continuous harassment helps to identify the second figure, while his contrasting whiteness is shorthand for a ghostly presence. Although the drawings and lithograph could not have been seen by Rimmer, they provide chronological bookends to his work and are remarkably close in spirit.43 Kirstein certainly meant to record the similarity between the images, as in the replication of legs.

Fig. 41 David Scott, Self-Accusation, or Man and His Conscience, n.d. Color lithograph, 9 7/8 x 12 ¼ in (25.1 x 31 cm). From John M. Gray, David Scott, R.S.A., and His Works, Edinburgh, 1884, pl. 19

There was no fixed iconography for Conscience, and, given its history of rankling within, its visual depiction as a separate, exterior being is understandably unusual. Without the images by Chifflart and Scott, there might be grounds for the speculation of one scholar that the second figure in Flight and Pursuit could not be Conscience because it does not correspond to an “elevated moral condition.”44 But Rimmer spoke of a conscience as having many incarnations.45 Moreover, this second character wears pure white, a color traditionally indicative of virtue. As virtuous, the apparition would be an unforgiving companion rather than an angelic one, with an emotional demeanor geared to the crime and a holy identity conveyed by coloring and transparency. Its essential qualities are its purity, goading attachment, and inescapability, and, as in the case of Scott’s image, this Conscience is meaningfully a look-alike.

Irrespective of Conscience, Rimmer’s portrayal of an anguished state of mind has precursors in such well-known Romantic allegories as the Anglo-Swiss artist Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781, Detroit Institute of Arts), the Spaniard Francisco Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (ca. 1799, Yale University Art Gallery), and the American Elihu Vedder’s The Lost Mind (fig. 42).46 Finished in 1865, the last instance shows an over-protectively cloaked, yet inconsistently barefoot, young woman. With a worried, sidelong glance, she clutches what must be a defensive charm and wanders in a canyon that offers no reassuring path. Like Rimmer’s setting, hers seems to reflect her state of mind but as an awareness of isolation, abandonment, and entrapment. Because of his interest in psychic and spiritual states, the prolific Vedder is the contemporary whose imagery occasionally approximates Rimmer’s. Although the two artists seem to have known each other, they operated quite independently.47

Fig. 42 Elihu Vedder, The Lost Mind, 1864–1865. Oil on canvas, 39 1/8 x 23 ¼ (99.4 x 59.1 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Helen L. Bullard, in memory of Laura Curtis Bullard, 1921. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

Probably completed in the summer or fall of 1872, Rimmer’s painting first drew public notice when it appeared at a Boston art gallery, Williams & Everett, in early December as The Flight and The Pursuit.48 Later, evidently in 1874, the artist gave it to his supportive friend, Charles Augustus Nichols of Providence, Rhode Island, a prominent lawyer and local politician.49

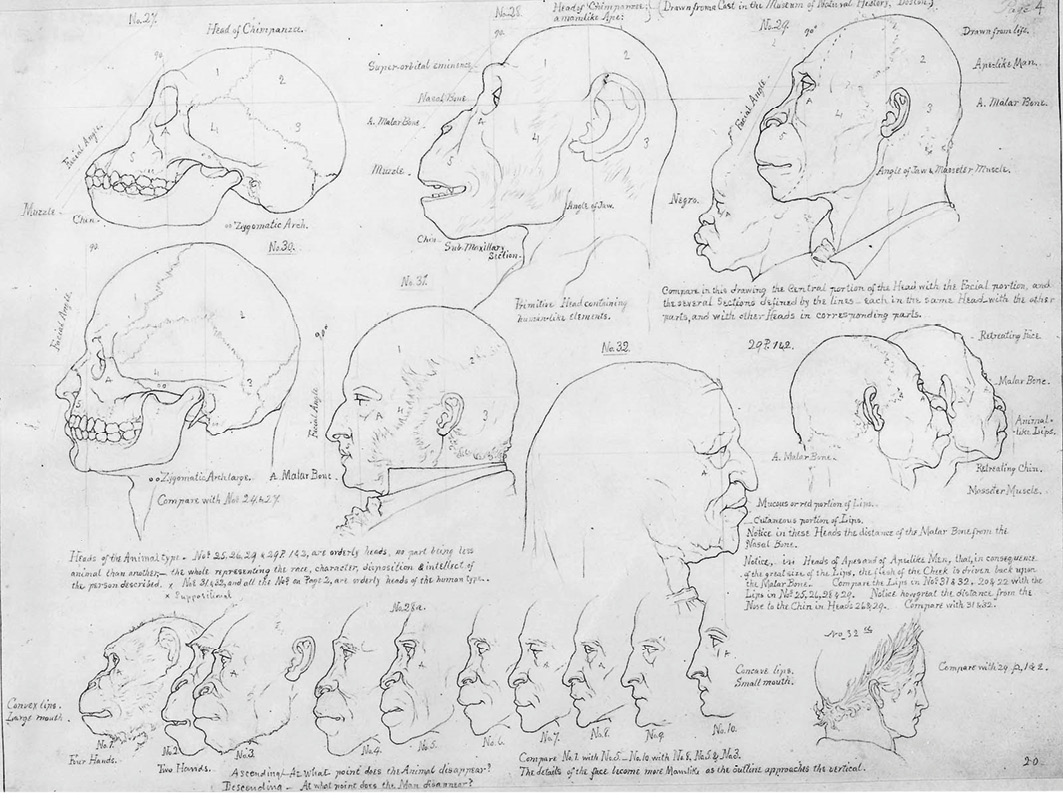

Nichols’ love of art made him an obvious recipient. He had been helpful in obtaining lecturing positions for the artist in Providence in 1871–1872 and had even become an informal Rimmer student. Making the connection closer, Rimmer’s concentration on teaching in this period seems to have influenced the appearance of Flight and Pursuit. In one of the Providence art lectures that Nichols attended, Rimmer drew individual heads that captured an attitude or emotion, such as fear as represented in both the preliminary drawing and subsequent painting. He then showed how the position of a body could strongly affect the viewer’s perception of the whole figure, including the face.50 As in his book, Art Anatomy, he also discussed the moral character that might be read from a person’s physiognomy, with different ethnic groups having both higher and more degenerate forms. According to his thinking, for example, the face of the first man in Flight and Pursuit, with his receding forehead and other attributes, would not be generic man in the manner of Scott’s protagonist, but, instead, a “debased” type.51

Although a masterpiece in its own right, Flight and Pursuit could be a kind of course summation which, aside from the anatomically accurate figures and character study, includes other aspects of Rimmer’s teaching: the dominance of one tone, the suggestion of atmosphere, the ethnic costuming, the foreshortening of limbs, and the creation of perspective through orthogonals as well as the diminished size of distant forms.52 Not all of his visual choices need to have been instructional but, because so many can be linked to his recent teaching, this experience appears to have been a source of inspiration for the picture. The desire to illustrate the effect of distance, for instance, would explain why the second figure does not follow the first in the foreground plane, as might be expected in a chase. Even the fancy cape serves to demonstrate perspective through overlap, made more obvious by the addition of a shortened white stripe which, otherwise, seems to have no purpose.

There is a disruptive element, however, that cannot be so readily explained. The background relief decoration (as well as the architecture) is strangely disjointed and heterogeneous for a real building. The decorated left and right walls of the archways, for instance, do not match, and, within a panel, the patterns are not repeated as would be expected.53 While the general ambiance is Middle Eastern, as if the scene were meant to be timeless and of biblical importance, the uncoordinated details create an otherworldly or hallucinatory effect. This could be purposeful and appropriate for Conscience. That there should be aberrations underscores the fact that the whole scene is based on the culprit’s imagination. As reported and possibly demonstrated here, Rimmer was interested in the imperfections of visual perception. He knew that it could change with circumstance.54

Before Nichols obtained the painting, it was given a public airing that went beyond Boston in that it was offered for sale, at “Mr. Brown’s” gallery in Providence in January of 1874. A local newspaper contributor described it as showing “the interior of an Oriental [Middle Eastern] sanctuary, into which a murderer is fleeing for refuge, while in the distance an avenger is seen hurrying to intercept him. A shadow projected into the right-hand corner indicates that other pursuers are behind.”55 This first impression from the period is one that Rimmer might have expected. While it misses the implications of the avenger’s transparency, it also defies subsequent explanations by not recognizing the scene as either a contemporary or historical reference. Instead, the text reads: “Although it … was evidently meant rather to furnish hints to artists than to afford pleasure to the public, this admirable piece of work may be examined with the greatest advantage.” Rimmer’s reputation is behind this reaction. He was known primarily as an art teacher who taught by example, and he seldom exhibited his own work.56 One journalist had the insight to comment that it was so rare for “a man of original genius” to be willing to instruct that Rimmer’s fame as a superior teacher seemed “to stand in the way of many people’s appreciating him as an artist.”57

As Bartlett reported, Rimmer once claimed that he always intended to create pictures from scriptural topics.58 But, after he became a lecturer, which would have been in 1861, Rimmer lost interest in themes concerning human events. Instead, as Bartlett noted, he turned more to the challenging depiction of “abstract ideas,” or his own moral allegories, which might involve single figures, multiple figures, or even landscape.59

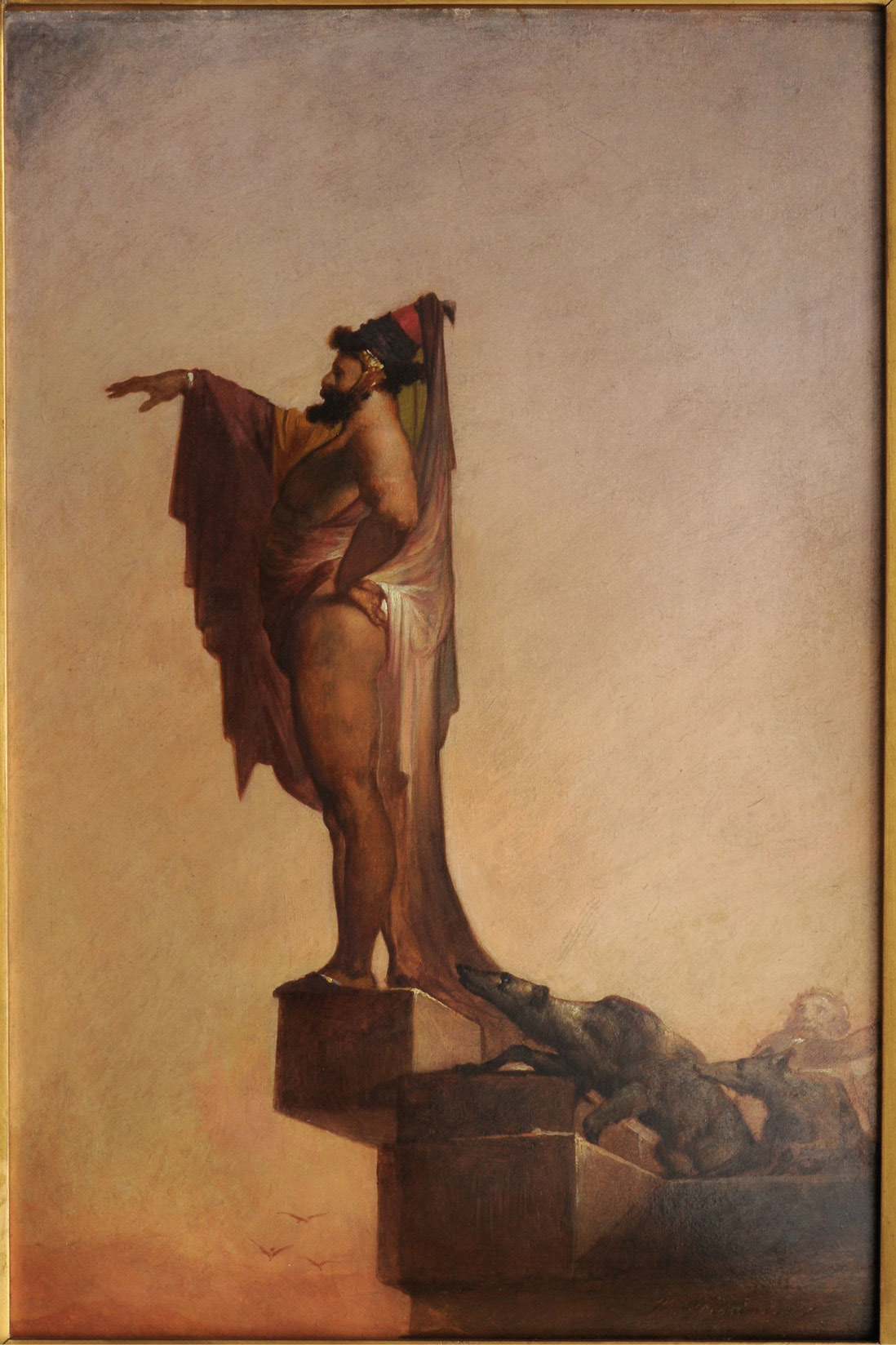

In this vein, he attempted unusual but universal subjects, such as Grief (destroyed), which is an emotional state closely related to guilt. Its realization might have been a dramatic, single personification like that in Evening, or the Fall of Day (fig. 43), where day takes the form of the beautiful, prideful fallen angel, Lucifer, “son of the morning” (Isaiah, 14:12). Or, Grief might resemble the personification in The Sentinel (fig. 44) or, with added figures, the personifications in Flight and Pursuit and The Master Builder (fig. 45). Rimmer created such imagery in preference to current, political subjects, such as (as Bartlett mentioned) scenes from the life of the Abolitionist John Brown. Indeed, he tended to think creatively in terms of weighty abstractions which occur in his manuscript as well. For example, the characters argue over which is the greater virtue, Justice or Charity, and Rimmer witnesses a vicious battle between a human female Chastity and vampire-bat Lust.60

Fig. 43 Evening, or the Fall of Day, 1869–1870. Crayon, oil and graphite on canvas, 40 x 50 in (101.6 x 127 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Leaning on a pole, the helmeted figure in The Sentinel maintains his position, as the title suggests, with sustained endurance, much like the solid wall behind him. He can be identified as Fortitude, one of the four cardinal virtues. In addition to the man’s physical strength, all-weather attire, and forbearance, the real clue to recognition is the cryptic inscription at lower left. The two upper lines may have been an attempt to write something that now appears as gibberish, but the lower line can be translated in old Hebrew as “man from Kitti” or Citi, referring to a city-kingdom (present-day Larnaca) on Cyprus, whose most famous citizen was Zeno (born ca. 334 BCE), the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy. In an original but identifiable conception, the man depicted is the very epitome of stoicism and its value as a means of protection.61 It is understandable that Rimmer, who suffered repeated misfortune, would not only be attracted to the concept of stoicism but also want to represent its steadfastness as a heroic virtue. He was all too aware of the Stoic tenet of uprightness as its own reward.62

Fig. 44 The Sentinel, ca. 1868. Oil on paperboard, 18 ½ x 12 1/8 in. (47 x 30.8 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Like The Sentinel, The Master Builder has not only a specific title traceable to the artist, but also it embodies one of Rimmer’s “abstract ideas.” In this case, he has produced an allegory of hubris or the deadly sin of pride.63 It is an instance, once again, of Rimmer delighting in constructing a figure “based upon some leading human trait.”64 Large-chested, brawny, and dressed in a fanciful outfit suggestive of vanity, the builder, at a great height, stands precariously on the edge of an unsupported building block — an embedded visual clue to Rimmer’s meaning — and gestures authoritatively with an arm cloaked in purple. Emphasizing his instability, his toe protrudes beyond the top block. At lower right, a man wearing a crown recoils with fear in his eyes and in his posture. Although elevated as a king, he would not attempt to add further height. As in Proverbs 16:18, the egotist on the highest block, or Pride itself, “goeth … before a fall.” Even the slightly slanted position of the builder’s extended hand is suggestive of downward motion. Bartlett calls the image “one of the artist’s strange subjects,” and, among possible interpretations, says it could illustrate human vanity.65 Vanity is pride, but, after Rimmer’s death in 1879, the picture lost its original meaning. Fortunately, in 1935, a Rimmer student referred to it as The Master Builder of the Tower of Babel, which he recalled seeing in 1877.66 Not coincidentally, Dante, whose Divine Comedy Rimmer read, identified the Tower of Babel and its Babylonian builder, Nimrod — seen together in Purgatory — as an example of pride. It is no wonder then that the figure of Pride resembles Babylonian reliefs of bearded kings (British Museum), and, as Nimrod (Genesis 10:9) was an acclaimed hunter, this figure is accompanied by loyal, but frightened, hunting dogs. Combining two sources — Dante and the Bible — Pride is shown as an irrationally over-confident builder, one who intends his own status to challenge that of God.67

Fig. 45 The Master Builder, ca. 1871. Oil and sepia on academy board, 21 7/8 x 15 9/16 in. (55.50 x 39.50 cm). Private Collection.

Rimmer ridiculed pride on more than one occasion, as in his poem, “The Love Chant: A Satire,” written from the point of view of a Boston suitor who is overly concerned with social appearance.68 Pride is mocked again in his preposterously elaborate helmets on the bellicose horsemen in Sketch for “To the Charge!“ (Fogg Museum) and in the raised arm of Mercutio in an invented Scene from “Romeo and Juliet” (University of Michigan Museum of Art).69 More than this, the sin of pride particularly bothered Rimmer in his own life. He must have seen it in his father’s self-destructive claim to the French throne, and he certainly saw it in his own lack of charity in his estimation of others. This is especially clear in his manuscript where, as has been noted, he projected this weakness onto his alter ego, Phillip.

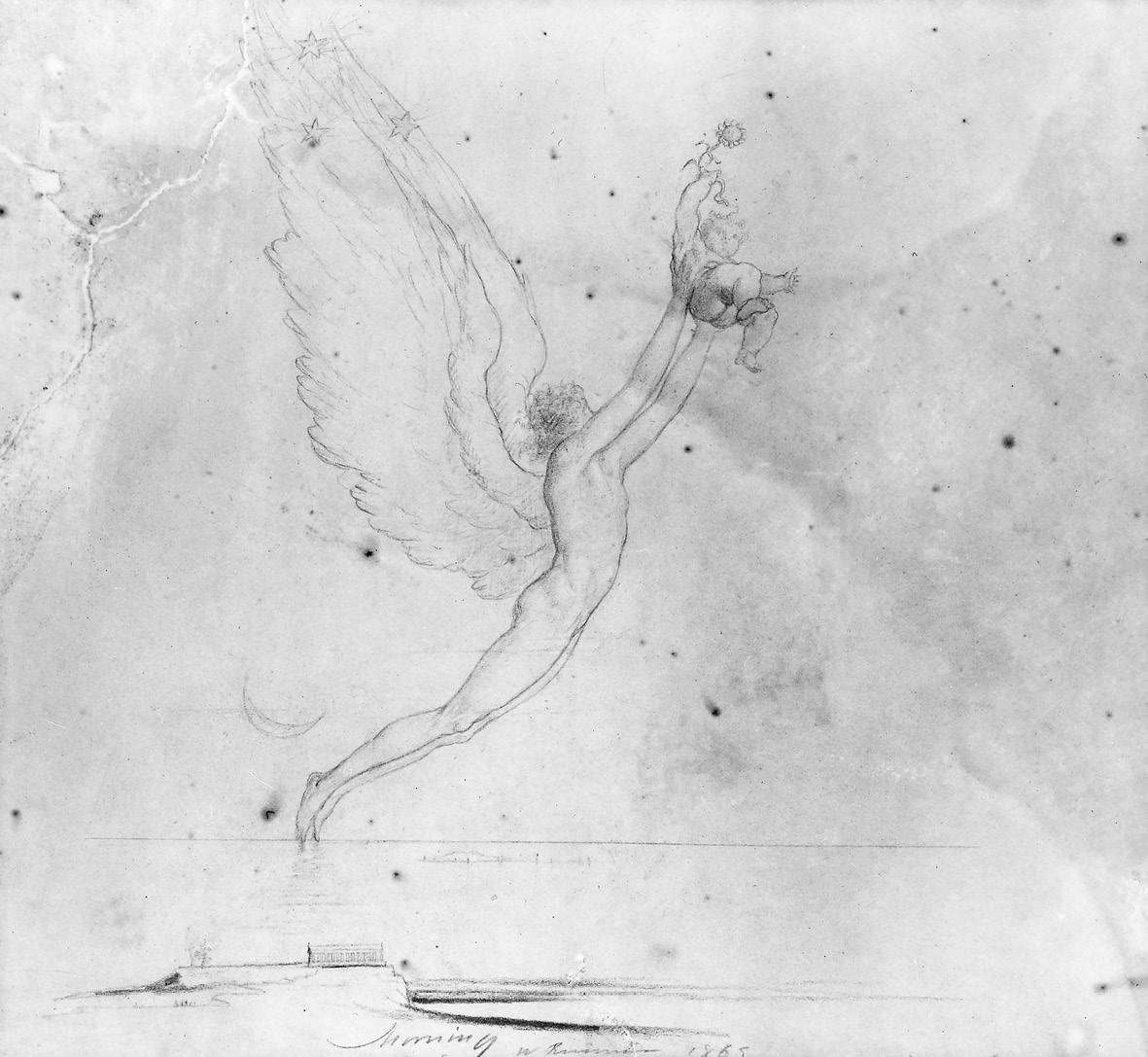

A concern with pride is undoubtedly why Rimmer, after creating paired- personification drawings, in 1869, of Evening (no. 59.263; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and Morning (fig. 46), developed and repeated the figure of Evening (Lucifer) in a larger format (fig. 43). Dante, in his visit to Purgatory, mentions seeing Lucifer (more “noble” than all other creatures) as another example of pride whom he witnessed falling “like a thunderbolt” from the sky.70 Paired with Pride, often called “the root of evil,” Morning shows a winged youth, with a classical temple beneath his feet, rising in a graceful sweep and holding aloft a happy child with a sunflower.71 The three stars on his wings refer apparently to the three theological virtues — Faith, Hope and Charity or Love — with the ancient temple symbolizing faith (tau cross and tree in front), the exuberant youth evincing hope, and the flower-holding child offering love.72 The three are divine fortifications or bulwarks against temptation, mentioned by St. Paul (1 Thessalonians 5:8). Consistent with Rimmer’s propensity for symbolic abstractions, The Master Builder, Evening, and Flight and Pursuit can all be similarly interpreted as spiritual allegories but concerned with sin. Importantly in the last two examples, the sin is not just indicated but also divinely punished.

Fig. 46 Morning, 1869. Graphite pencil and red crayon on buff paper, 12 9/16 x 14 ½ in. (31.9 x 36.8 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Miss Mildred Kennedy. Photograph © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

To the extent that Conscience is a divine response, Flight and Pursuit relates to Rimmer’s two earlier biblical compositions: Massacre of the Innocents (fig. 47) and Hagar and Ishmael (private collection), from about 1858.73 As in the case of the altar in Flight and Pursuit, Rimmer’s dislike of “priestcraft” becomes a factor in Massacre. The painted depiction adds to the mayhem of the biblical story (Matthew 2:16) a foreground vignette of a child being killed in his mother’s arms, beneath a useless incense-burning altar. On a high prominence, the victims raise their hands toward Heaven in supplication. Having come to this site for its sacredness and its supernatural potential to protect her, this mother is especially pitiful in her abandonment. Ironically her son will be murdered on the ritual block for animal sacrifice.74 The second picture has an opposing theme. God did respond to Hagar who also looks to Heaven and prays fervently, but in a desert wilderness, for the survival of herself and her son. Her prayers, and those of her son, were answered by the miraculous appearance of well water (Genesis 21:19). The contrast in the pictures spotlights an injustice that is difficult to comprehend. According to Bartlett, nothing could undermine Rimmer’s faith in “a divine Being,” but his belief grew only over time and after years of intense struggle.75

Fig. 47 Massacre of the Innocents, ca. 1858. Oil on canvas, 27 x 22 in. (68.58 x 55.90 cm). Mead Art Gallery, Amherst College, Amherst. Gift of Herbert W. Plimpton: The Hollis W. Plimpton (Class of 1915) Memorial Collection

In other religious work, Rimmer tended to focus on good and evil influences on mankind’s moral condition. For instance, he drew a figure of Satan (unlocated), a head of Mephistopheles (unlocated), a crucified Christ (lost), images of saints, and a large Assumption of the Magdalen (fig. 48). The last has been mistakenly titled Madonna / Magdalen because of uncertainty over the subject. She is the blonde Magdalen, as opposed to the Virgin Mary, whom Rimmer portrayed elsewhere as a brunette. That the picture depicts the glorious redemption of the Magdalen, one of the Bible’s most famous sinners, lends support to the emerging pattern of Rimmer’s concern with the subject of sin.76

Fig. 48 Assumption of the Magdalen, 1860s or 1870s. Oil on canvas, 60 x 29 in. (152.50 x 73.50 cm). Richard L. Feigen Collection

In this context, Rimmer’s late painting, Sleeping (fig. 49), is likely another work on his moral scale. It is convincing as a symbol of innocence rather than an erotic work as it has been interpreted.77 This is not just an imaginary child lying naked on a bed with her mouth open, arm extended, and light centered on her pelvis. Rather, in her unconscious sensuousness and the welcoming position of her arm, she is credible as a symbolic image of absolute trust and the absence of sin. In the same way, the opened flowers in an urn at her feet signal her association with a culmination of beauty. Physical beauty, as in this instance, means for Rimmer the “soul’s perfection.”78 More particularly, and far from being erotic, her bodily position and appearance recall the symbol of a human soul used in his drawing, On the Wings of the Creator (fig. 50), which refers to a child’s birth.79 In support of this connection, Rimmer described a helpless infant as “holier than the parent.”80 Through Stephen, he revealed his probable message, and continuing preoccupation, by proclaiming “the greatest of all blessings is innocence.” Her nakedness is no less than a badge of innocence.81

Fig. 49 Sleeping, ca. 1878. Oil on academy board, 8 x 10 ½ in (20.35 x 26.68 cm). Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, N.H. Museum Purchase: Gift of the Friends 1985.41

Fig. 50 On the Wings of the Creator, undated. Red chalk and pencil on brown paper, sheet: 11 15/16 x 14 3/8 in (30.3 x 36.5 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest from Estate of Frank C. Doble. Photograph © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In Flight and Pursuit, the division between the man’s corporeal self and his immaterial conscience reflects a moral hierarchy that can be found in both Rimmer’s writing and his art. For example, he wrote: “All those who follow the flesh and live in its gratification whether from weakness of conscience or the tyranny of passion are beasts … All those who master the body and believe in the soul and the conscience [emphasis added] are men, be they who or what they may.”82 Such men correctly follow the leadership of their better selves.

The same body / soul dichotomy reappears in Rimmer’s 1869 sculpture, Dying Centaur (fig. 51). As it has sometimes been understood, in an interpretation that is supported by its appearance, the bestial part of this centaur sinks in death as the soulful, human part aspires to ascend from the earth-bound body. In essence, this centaur seeks the salvation of his human soul. Suggesting this explanation, Bartlett observed that the artist “exulted in compositions in which the soul looks down upon the world, in which all power of beast [is] subservient to the exalted superiority of man.”83 It is, as Stephen realized, the divinity of man’s nature in his possession of a soul that sets him apart.84

Fig. 51 Dying Centaur, 1869. Plaster, 22 x 24 ¼ x 25 ½ in. (55.9 x 61.1 x 64.8 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of Miss Caroline Hunt Rimmer. Photograph © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

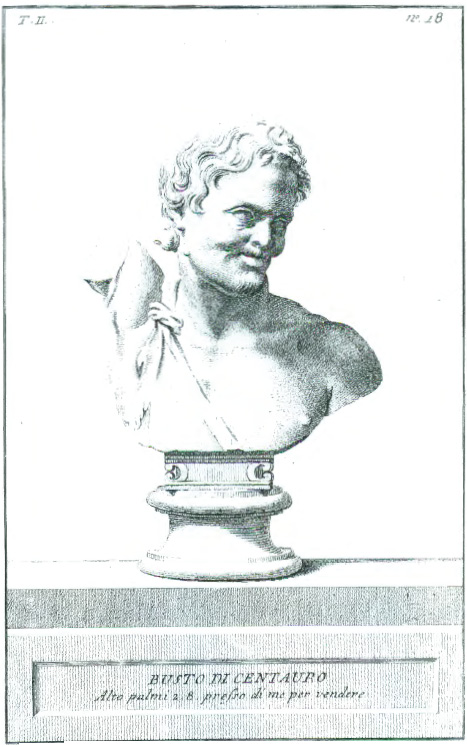

Rimmer’s youthful centaur does not adhere to its iconographic type. The face of a male centaur is traditionally bearded and configured to reveal a brutish nature in contrast to the refinement of a more civilized opponent, such as Theseus, a Lapith, or even a bearded Hercules. If the typical centaur’s beard and mustache are minimized, as in this engraving of an antique bust (fig. 52), his face still does not conform to an ideal type (the classical Greek head). But the reverse is what we see in Rimmer’s sculpture (fig. 53). With unconventional eyes, a furrowed brow, and mouth slightly agape (as if in an otherworldly trance), Rimmer’s centaur’s face is especially strange in being a combination of a Greek ideal for masculine beauty and an incarnation of pleading innocence. Indeed, the eyes, unnaturally lidless and bulging, convey the effect of “glowing orbs,” an expression Rimmer used in his manuscript to describe eyes in a spiritual state.85 Eyes in this state, he called “soul’s eyes.”86

Fig. 52 Anon., Bust of a Centaur, 1769. Engraving, 12 x 7 8/10 in (30.4 x 19.8 cm). From Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, Raccolta d’antiche statue, busti, bassirilievi, ed altre sculture, Rome, 1769, vol. 2, pl. 18

Fig. 53 Dying Centaur (detail), model 1869, cast 1967. Bronze, 25 ¾ x 25 5/8 x 21 1/2 in. (65.4 x 65.1 x 54.6 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington. Gift of the Avalon Foundation

In a related way, Rimmer’s lectures and illustrative drawings included an analysis of gradations of physiognomic difference between man and beast, connecting their outward appearance to their inner nature. While not new, this kind of encoding provided moral clarity in the reading of faces in art, especially in narrative pictures such as Flight and Pursuit. According to Rimmer’s period-based typology, the human head as it approaches the form of an ape’s skull (fig. 54) is indicative of an animal nature, and as it approaches the Greek classical ideal, as in this centaur’s head, it is indicative of an intellectual or spiritual nature.87 Such differences are consistent with Rimmer’s belief concerning the presence within man of a higher being and the need to subjugate what are animal instincts.

Fig. 54 Comparison of Men: Ape Heads, from “Art Anatomy,“ ca. 1877. Graphite pencil on paper, 10 ½ x 14 13/16 in. (26.6 x 37.7 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Although the subject of the Dying Centaur seems self-explanatory, this is no ordinary centaur. He almost certainly derives from the main character in the moral tale: The Centaur, Not Fabulous by the poet and theologian, Edward Young. In his reading choices, Rimmer favored English poets such as Young. The 1755 text went through several editions in the early nineteenth century including as part of a compendium of the author’s work in 1854.88

Significantly, Young’s “Centaur” is not an imaginary creature but rather his designation for the culmination of a human type, the “Man of Pleasure.”89 His Centaurs are biblical prodigal sons in a Christian era, who enjoy life and indulge their appetites without regard for others. As Young describes the moral decline in his part-animal subject, “The man [in his folly] debauches the brute: the brute, debauched, dethrones the man: the dethroned man, and debauched brute, join in rebellion against the immortal” soul. If unrepentant, his spirit will be poisoned forever.90 In a warning to the reader, Young returns repeatedly to the central question of what happens when the Centaur (named Altamont in the story) confronts a death that might be his entrance to Hell. This dilemma is convincing as Rimmer’s subject. As Rimmer suggests, through his centaur’s eyes and beseeching gesture toward a higher power, his soul still has — in Young’s words — “all the sublime beauty originally stamped upon it by Deity.”91 This divinely-created man who has become a Centaur desperately seeks salvation but is not yet saved. In this context, the Dying Centaur symbolizes what an indulgent man has done to make himself less perfect before his Creator.

Through this interpretation, one of Rimmer’s best-known works reinforces a new view of the artist as often a portrayer of moral concerns through invented circumstances. The Dying Centaur joins Flight and Pursuit as part of this pattern. The theme of the Centaur is also consistent with Rimmer’s apparent belief in the rewards of a life involving self-denial or stoicism.

The presence of a human, spiritual essence or higher self — as seen in the Centaur — appears to be the main theme in Rimmer’s Civil War Scene (fig. 55) as well. In this case, concerning the aftermath of an artillery raid, a wounded Northern cavalry officer seeks solace in drinking from a fresh stream. More to the point, as he contemplates a painted miniature that contains the likeness of someone he loves, his low head bandage (in an attention-attracting red) takes on the appearance of possibly a lifted blindfold. The preliminary drawing for the entire scene (Fogg Museum) suggests its basic content in that it is inscribed: “To Any Man Ful of Love.”92 While the officer is soulful in his reverie, his horse, shifting hooves uncomfortably, looks out at an abbreviated portrayal of the Confederate war dead, with quizzically alert ears but without human comprehension. Illogically, there are two bedrolls — one a Union blue and the other a Confederate gray — on the horse’s back which signals the presence of coded allusions and makes this man appear to represent soldiers from both sides. The treasured miniature, spiritually understood backlight, and distant church all contribute to the contrast of the man’s higher self (love) and lower self (hatred) as exhibited on the battlefield. The picture has been interpreted as conveying the futility of war, but the drawing’s inscription eschews war and is wholly focused on the humanity of the survivor. Wounded and grasping his miniature, he recognizes what gives his life meaning.93

Fig. 55 Civil War Scene, probably 1860s. Oil on canvas, 20 ¼ x 27 ¼ in (51.4 x 69.2 cm). Detroit Institute of Arts. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Sheldon Stern, 73.103

Rimmer’s strong inclination toward pacifism recurs in two pictures that are likewise concerned with abstract values but show moral failures. His oil paintings, Sketch for “To the Charge!“ (Fogg Museum), dated 1874, and Battle of the Amazons (fig. 56) from probably about the same time, depict the foolishness of common causes of war: arrogance and vengeance. Approximately the same size (13 × 18 inches) with one on cardboard (Charge) and the other on canvas, they deliberately relate by repeating, with some variation, the foreground two wounded men within a scene of slaughter. The pose of one of these men in To the Charge partly copies the famous sculpture of the Dying Gaul (Capitoline Museums, Rome). In the first picture, a rebellious horse provides a note of sense by refusing to join the overly-decorated, or freakishly-helmeted, horsemen in battle. In the second, concerning the Trojan War, Achilles, on horseback, pursues the queen of the Amazons, Penthesilea, who has heads of victims dangling from her saddle. What makes this vengeance particularly senseless is that these two protagonists are potential lovers. Achilles fell in love with her at the moment he killed her. Underscoring the theme of extreme folly, an unnoticed white flag of surrender, waving in the background over defeated troops, comes literally between the two riders. Its role is comparable to the horse in the first picture.94

Fig. 56 Battle of the Amazons, ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 13 3/8 x 18 in. (34.00 x 45.73 cm). Manoogian Collection.

Given the emphasis on mystery and originality in Flight and Pursuit and Rimmer’s position as a teacher, he had to have been aware of — and would have agreed with — the strong, supporting stance that the British art critic and author, John Ruskin (significantly influential at mid-century) took on both. For Ruskin, it was axiomatic that all great art had to be inventive, but, beyond this, he singled mystery out as a pictorial characteristic that is a source of special aesthetic pleasure.95 Particularly in the case of artworks such as these by Rimmer that teach, in Ruskin’s words, “Divine truth,” there must be a mysterious element: “Excellence of the highest kind without obscurity cannot exist.”96

This effect of incomprehensibility was not a passing interest but, rather, a guiding principle in much of Rimmer’s work. Because of it, he even praised the indefiniteness of the English landscapist William Turner’s backgrounds.97 In Flight and Pursuit, the lighting — like the unmatched wall patterns — plays a decisive role in promoting an ambience of mystery. Rather than wholly logical, it is partly symbolic. Light enters from hidden, implied windows at upper right, and from hidden overhead sources in the background, behind Conscience. Within framing archways, this distant light helps to dramatize and further etherealize the already-transparent, central figure of Conscience, giving the impression of a hallowed being.

Light to Rimmer carried symbolic meaning such as in Sleeping and in the following reference, in his manuscript, to celestial beauty: “The pure light of heaven hung in the sky and the sweet beams of immortal life brightened the day.”98 More relevantly, he speaks of an aura surrounding Phillip in his angelic state, signifying his status as holy or “divinely favored.”99 Rimmer’s light in his Flight and Pursuit also fosters a degree of incomprehensibility. For instance, light coming from the foreground right could explain the enigmatically illuminated, inner left side of the first arch, but, if that were the case, almost all the shadows would be different. In short, this painting is not limited by the laws of nature or confined to this world.

Consistent with this confusion, Conscience casts a shadow, albeit fainter than the nearest shade. Rimmer spoke of a fearful envisioning of shadows, creating — through imagination — a false reality. This is what the background and surroundings are, as part of a self-haunting.

When addressing the issue of subject matter, Rimmer promoted the inclusion of mystery in such a way as to lead to misunderstanding over Flight and Pursuit. Part of a lecture (reproduced in Bartlett) can be misread to mean that his paintings were intended to have an open-ended quality.100 Central to this is Rimmer’s comment that “the more closely [a subject] is defined … the more circumscribed must be its theme, the narrower the sympathies that surround it, and the less enduring the pleasure that flows from it.”101 Put differently, “individual modes of thought or conceptions of character, when given in a form that leaves nothing to the imagination, are seldom found to correspond to [the memories] of the beholder.”102 While these vague statements advise avoiding specifics — as in time, location, and costuming — his recommendation is not the same as advocating an open-ended content. Nor, in this instance, would Rimmer’s contemporaries expect it.103

Essentially, he said the same thing on another occasion: “Leave something for the imagination.”104 This exhortation relies on the association of ideas, a doctrine that echoes Ruskin but also hails from the eighteenth-century thinking of such theorists as Sir Joshua Reynolds. That is, that a work of art can be enriched by its openness to the viewer’s association.105 Washington Allston, a Boston artist from over a generation earlier, was a proponent of such a theory.106 But there is no expectation that the spectator imagine wholesale changes in subject or layers of different meaning.107 Rimmer merely pushed his students to introduce ambiguity, so that the viewer might be encouraged to indulge in the pleasure of his or her related thoughts. This would appeal to the viewer’s appreciation of a meaning that is not immediately obvious, providing potential for deeper contemplation. Significantly Rimmer not only spoke of an artist’s theme as a single subject, but he also limited the meaning of Flight and Pursuit by supplying a title for the preliminary drawing.

Not all viewers of Flight and Pursuit could relate to the picture’s deeply felt message of unrelieved guilt. But this interpretation is supported by a heretofore misidentified drawing (fig. 57) by Rimmer that proves his interest in the subject by showing its moral opposite: the triumph of a virtuous man and his conscience at the end of his life.108 Such a person offers a marked contrast to the dying Centaur. In his pose with one bent knee, the reclining man is a partial quotation of Adam from Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam (Sistine Chapel, Vatican City), and his character draws on this association — the reference to having been created by God. In addition, he carries a long laurel branch as a symbol of his triumph. On the left, in an exhausted state and leaning on the Adamesque figure in an adoring way, lies Conscience, smiling and holding a multi-thong whip. This Conscience, perhaps because of his victorious role, has wings, which are not an unheard-of appendage for Conscience.109 Above both figures is another winged being or angel offering a crown of life (James 1:12) as a reward for having resisted temptation. To the right is a setting sun and at the far left is a symbol of Satan — an eared owl — trapped in a container.110

Fig. 57 Three Angels (re-identified as Triumph of a Virtuous Man and His Conscience), probably 1860s. Graphite on paper, 10 ¼ x 8 ¼ in. (26.05 x 20.95 cm). Rimmer Sketchbook, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University

Ultimately, the aberrant appearance of Flight and Pursuit is the decisive factor in determining its meaning. It follows a modus operandi that can be found in much of Rimmer’s narrative painting and even his sculpture, The Dying Centaur. Despite the contrivance of mystery, understanding depends upon recognition of visual clues, such as the flagellant’s whip or the otherworldliness of the centaur’s face. In the case of Flight and Pursuit, there is a tantalizingly unexplained shaft of light. More specifically suggestive is the transparent, duplicative figure in white: Conscience, carrying an identifying emblem. The powerful subtext is that you cannot evade Conscience even through religious belief or its simulation.

1 See, for instance, E.P. Richardson, Painting in America from 1502 to the Present (1956 reprint: New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1965), 261–62. The exhibition’s 1985 catalogue, with an entry on the painting, is Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 68–69.

2 For Surratt, see Marcia Goldberg, “William Rimmer’s ‘Flight and Pursuit:’ An Allegory of Assassination,” Art Bulletin 58 (June 1976): 234–37, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1976.10787276. For warriors, see Ellwood C. Parry III, “Looking for a French and Egyptian Connection behind William Rimmer’s ‘Flight and Pursuit,’” American Art Journal 13 (Summer 1981): 56–60. For Solomon, see Carol Troyen in Theodore E. Stebbins Jr., et al., A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting, 1760–1910 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1983), 291–92. For slaves, but the interpretation is multi-layered and open-ended, see Sarah Burns, Painting the Dark Side: Art and the Gothic Imagination in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 129, 135, 138, 149, 157. Readings by others include the argument that the picture refers to Rimmer’s father as the lost heir to the French throne. For this, see Charles A. Sarnoff, “The Meaning of William Rimmer’s ‘Flight and Pursuit,’” American Art Journal 5 (May 1973): 19, https://doi.org/10.2307/1594284. Sarnoff’s opinion and that of others are repeated in Weidman’s entry on the work in his Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 2:592–626. Weidman also adds further suggestions, including that that the painting is “a vehicle for a wide range of symbolic meanings” (613). The same opinion appears in Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 69. Closer to the present interpretation in 1980, Troyen wrote of seeing “aspects of a single personality” in the painting. Identifying the background figure, an “unnamed force,” as the foreground man’s imagination, she concluded the scene represents “paranoia.” See Troyen, The Boston Tradition: American Paintings from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (New York: The Federation, 1980) 146–47. No one has located a close visual precedent.

3 Elliott Bostwick Davis, et al., A New World Imagined: Art of the Americas (Boston: MFA Publications, 2010), 279. This concurs with Weidman and Burns (see above).

4 See Edith Nichols’s letter, April 23 [1946], to Lincoln Kirstein, regarding their meeting to discuss Flight and Pursuit, folder entitled “Correspondence Feb–Oct, 1945,” Kirstein and Nutt Research Material, Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C. She lent the picture to a 1946 exhibition that Kirstein organized. For interpretation, see [Kirstein], Rimmer, [38]. On friendship, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 21.

5 [Kirstein], Rimmer, [38].

6 Charles Colbert, A Measure of Perfection: Phrenology and the Fine Arts in America (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina, 1997), 105.

7 Bartlett, Rimmer, 113. Rimmer strongly implies this is his aim. His Civil War drawings, such as Dedicated to the 54th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) are examples in that the fighting soldiers wear Roman armor. They thereby attain the status of timelessness or kinship with revered predecessors.

8 He had a sustained interest in allegory. See, for instance, his representation of the Civil War as a battle between Columbia and Secessia in The Struggle Between North and South, and Secessia and Columbia (both 1862, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

9 See Rimmer’s manuscript, “Stephen and Phillip,” Boston Medical Library, where he describes himself as unjust (137), guilty (217), and sinful (235, 383) with sins including evil thoughts (19). His sins become those of Stephen and Phillip.

10 Rimmer even said that we perceive the world through the lens of ourselves and much of what we think we see actually comes from our own soul. For this, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 109. The percentage, probably too high, is Weidman’s calculation in Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 1:136n188.

11 On the verso of a sketch of Hercules, which is initialed and dated 1867, the preliminary drawing probably dates from 1872, the year of the painting. As Bartlett notes, the artist was known for reusing paper scraps (Rimmer, 128). In the final painting, he corrected the extended leg somewhat in that it is more bent and the bottom of the sandal turned to conform better to a profile view.

12 Bartlett, Rimmer, 95.

13 The historical symbolism of the horns is not clear but the horned altar is first mentioned in Exodus 27:2, where it is described, and Exodus 29:12, where the projecting horns on this holiest of altars are anointed, as they habitually were, with sacrificial blood. The expression “the horns of the altar” in Rimmer’s day could mean any refuge of last resort. For an example of this, see Anon., “The Horns of the Altar,” Galveston Tri-Weekly News, November 20, 1871, [2].

14 Bartlett, Rimmer, 95.

15 That the shadow to the right indicates pursuers first appears in an 1872 Providence Daily Journal (?) clipping in the Newspaper Clipping Scrapbook of Mary H.C. Rimmer, Boston Medical Library.

16 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” for hard-hearted, 119; for murder, 219, 279, 331.

17 For alas and things, see Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 17.

18 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” for Babylon and Nineveh, 31.

19 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” for Conscience personified, 37.

20 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” for conscience, 49; for Stephen whispering, 331.

21 Bartlett, Rimmer, 107. It appears in a short aside about Protestants and Catholics, concluding that the conscience is better entrusted to worship than to reason.

22 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” for whirling, 23; for evil thoughts, 19; for sinner, 235; for right and wrong, 27–29,101, 275–83, 333, 347.

23 For lack of charity, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 21, 27, 140. But he was a conflicted person who was also known for his kindness. On this, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 141. For his charity, see Anon., “Dr. William Rimmer,” Boston Evening Transcript, August 22, 1879, 6.

24 Bartlett, Rimmer, 21.

25 Jamison, Touched with Fire, 13, 262. Also Bartlett, Rimmer, 27–28.

26 Bartlett, Rimmer, 10, 62, 81, 89. Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 21.

27 [Kirstein], Rimmer, [13]. The Transcendentalist movement (semi-religious and sometimes comprising conflicting viewpoints) was founded by a coterie of New England intellectuals, including Emerson, in the 1830s and largely spent by the end of the Civil War. One of their commonly held beliefs was that mankind could receive direct revelation from God, bypassing the experience of the senses or powers of reasoning.

28 See reminiscences throughout Bartlett, Rimmer, with a supplement on student reminiscences, 132–47. He had the recollections of Rimmer’s surviving family and intimate friends (v) and of 150 responses to about 500 circulars asking for information on Rimmer (vi). Rimmer’s lost diaries (seen by no other Rimmer scholar) are mentioned on 27, 31, 32, 47, 121, and 122. He briefly cites a “East Milton Diary” and its entries from 1861 (121) to possibly 1863 (47). But he evidently did not see all the diaries or was not allowed to use all of what he saw. For this, see Bartlett’s 1876 article on Rimmer in Walter Montgomery, ed., American Art and American Art Collections; Essays on Artistic Subjects by the Best Art Writers (Boston: E.W. Walker and Co., 1889), 1:337. From his brief description of the manuscript, Bartlett evidently did not read it (Rimmer, 84). For Rimmer’s religious outlook, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 95. Rimmer urged his children to attend any Christian church until they made up their minds as adults (ibid., 95).

29 On knowing Emerson, see Edward Waldo Emerson and Waldo Emerson Forbes, ed., Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson, with Annotations (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), 15 (vol. for 1860–1866): 10, 22, 30.

30 For the quote, see Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 181. See also ibid., 101, where “the soul is a moral universe, and in it are all things of consciousness, temporal and spiritual.” For Christian, see 1 Corinthians 3:16. On related Transcendentalism, see Philip F. Gura, American Transcendentalism: A History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007), 10–14.

31 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” for conscience and soul, 49; for modes, 374.

32 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 185 and 363–65, for Darwinites. For against Darwinite Christians, see Rimmer’s poem, “The Love Chant: A Satire,” Rimmer Commonplace Book, Boston Medical Library. On Darwinite Christians, see also Randall Fuller, Books That Changed America: How Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Ignited a Nation (New York; Viking, 2017), 189, 246–47.

33 Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, with an Introduction by John Tyler Bonner and Robert M. May (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1871, reprinted, 1981), 391–92. This followed the publication in 1859 of On the Origin of Species and posed a more direct challenge to Christians.

34 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 95. For God’s involvement, see ibid., 363. For the soul, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 28, 96. Bartlett, ibid., 84, says that Rimmer made “lengthy comments on Darwin’s writings,” separate from his manuscript; in which case, they are lost.

35 A kinship can be found later with George Grey Barnard’s life-size sculpture, The Struggle of the Two Natures in Man, 1888, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Barnard admired Rimmer’s work and praised him as one of “the greatest artists of the world.” For this, see Caroline Rimmer’s undated letter to Truman Bartlett, p. 5, in container 43, Paul Wayland Bartlett Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

36 Edward Engelberg, The Unknown Distance from Consciousness to Conscience, Goethe to Camus (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972), 2:161. According to Paul Strohm, the separation of conscience from institutional religion is “normally viewed as a consequence of Enlightenment secularization.” Evangelical Protestantism, strong in the nineteenth century, also undermined the relationship. See Strohm, Conscience: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 17, https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780199569694.001.0001.

37 D.H. Meyer, The Instructed Conscience: The Shaping of the American National Ethic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972), 137.

38 Ralph Waldo Emerson, Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson in Five Volumes (Boston: Houghton, Osgood and Company, 1880), 4:250. Charles Mayo Ellis’s early pamphlet on Transcendentalism also emphasized a moral obligation to consult one’s conscience. See Ellis, An Essay on Transcendentalism (1842, reprinted. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1970), 63, 74, 78. The emphasis on an individual conscience preceded them and has been so prevalent in New England that it has been discussed even as a Pilgrim-based, regional phenomenon. For this, see, for instance, Austin Warren, The New England Conscience (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1966). The modern idea of personal conscience is certainly Protestant-inspired, going back to Martin Luther.

39 “La conscience” (lines 213–80) in volume one of Victor Hugo’s collection of poems, “La Légende des siècles,” first published in Brussels in 1859.

40 See its use in New Hampshire in Anon., “Serious Reflections,” The Farmer’s Cabinet (August 11, 1858), [1]. Bibles influenced by the Douay, repeat the expression.

41 Online graph of the frequency of its use: Google Books Ngram Viewer.

42 See plate 19 in John M. Gray’s David Scott, R.S.A., and His Works With a Catalogue of His Paintings, Engravings, and Designs (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1884). Gray, Scott, 42, dates the original watercolor drawing (Scottish National Gallery) as 1841, but gives no reason for the date. Kirstein’s photograph is in “Scrapbook Undated,” folder 7, box with bar code ending in 7440, Kirstein and Nutt Research Material, Archives of American Art.

43 Kirstein wrote that Rimmer admired Scott’s work “at least in reproduction.” See Kirstein’s letter, July 11, 1946, to Lloyd Goodrich quoted in Weidman, Critical Catalogue, 2:595, 605. Rimmer did praise Scott’s illustrations to John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. For this, see Ednah Dow Littlehale Cheney, Reminiscences of Ednah Dow Cheney (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1902), 144.

44 For the quote, see Colbert, Measure, 105–06.

45 For incarnations, see Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 374. When Rimmer created an evil figure, its moral degradation was always obvious as in his drawing The Midnight Ride, Rimmer Commonplace Book, Boston Medical Library.

46 As in the case of Fuseli, Vedder’s first version is cited. A second, smaller version (Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas) adds to the background a symbolic light which the protagonist leaves as she enters the foreground’s darkness.

47 See Vedder’s mentions of Rimmer in Elihu Vedder, The Digressions of V (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1910), 278, 289. Unlike Rimmer, Vedder — as he admitted — was not a mystic (ibid., 408).

48 The title is in a newspaper clipping, “Fine Arts,” inscribed by hand “Dec. 8, 1872” and “Boston Herald,” in the Clipping Scrapbook, Boston Medical Library. Unlike the ambiguous title it has now, the original title is perhaps more suggestive of a single, iconic and repetitive, event.

49 Nichols is misidentified as “Col. Charles A. Nichols” in the first (1882) and subsequent editions of Bartlett. The error is compounded as “Col. Charles B. Nichols” in American Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1969), 1: 216, and thereafter. See his obituary in Proceedings of the Rhode Island Historical Society, 1877–78 (Providence: Printed for the Society, 1878), 115–16.

50 For heads, the body and Nichols, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 76, 77.

51 For debased, see Rimmer, Art Anatomy, 10, 61. Bartlett, Rimmer, for head, 103; for earthy earing, 121.

52 See course instruction in Bartlett, Rimmer, 137, 147, 73–75; costuming in Anon., “Dr. Rimmer’s Art School,” Boston Daily Advertiser (May 7, 1870), [1].

53 For Rimmer’s interest in teaching ornamental design, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 52, 83. For his instruction in ornamental and perspective drawing, see also Anon., “The Cooper Union / Its Origin and Progress,” The Evening Post [New York] (May 28, 1866), 1, in the Merle Moore Newspaper Files, library of the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington. Rimmer’s architectural ornament is not copied from period books on ornamentation or architecture. Rather, it is consistent with his fertile imagination. The whole architectural setting is generally, but without quotation, inspired by Saracenic architecture in a book given to Rimmer, as Weidman has pointed out: Johann Heck’s The Iconographic Encyclopedia of the Arts and Sciences, volume 4, plates 19 and 20. See Weidman, Critical Catalogue, 7:1831. Near Eastern subjects were popular in the U.S. and Europe at the time. On this connection, see Troyen in Stebbins, et al., A New World, 292–93.

54 See Bartlett, Rimmer, 18, for Dr. Kingman reporting on in-depth conversations with Rimmer about “the powers of observation, perception, the internal recognition of things.” A similar case of hallucination is the ghost furniture in Interior: Before a Picture (fig. 73). Alternatively, it is possible that this wall-pattern lapse is related to Rimmer’s illness, in which case he decided not to correct it. Other instances of inconsistent details — less justifiable in context — are the inventive barrier along the staircase in Samson and the Child (fig. 19); the mismatched column capitals on the fountain in Horses at the Fountain(fig. 59); the mismatched eyes in Inkstand with Horse Pulling a Stone-Laden Cart (fig. 26); the mismatched sides of the wall the man is leaning on in The Sentry (fig. 143); and the disruption in the border design, from fold to fold, at the bottom of the tablecloth in At the Window (fig. 71).

55 Undated, unidentified clipping in the Clipping Scrapbook, Boston Medical Library. Its source can be traced as the Providence Daily Journal, January 9, 1874, [2]. “Oriental” was a term used at the time for Middle Eastern (O.E.D.).

56 For his reputation, see T.H. Bartlett, “Dr. William Rimmer: Second and Concluding Article,” The American Art Review 1 (October 1880): 509, https://doi.org/10.2307/20559727.

57 Anon., “Dr. Rimmer’s Art School” [1].

58 Bartlett, Rimmer, 95.

59 For abstract ideas, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 80, 125 (quote).

60 For Grief, a blackboard depiction, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 139. For Brown, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 125. The argument and the prolonged battle are in “Stephen and Phillip,” 283, 158–63.

61 The title is given in an inscription on the reverse signed by Rimmer’s daughter, Caroline. See Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 2:543–49, for further information and speculation but without a determination of the picture’s meaning. See Diogenes Laërtius, The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, trans. C.D. Yonge (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1853), 269, for an ancient description of the perseverance of Zeno of Citium (a word that could also mean Cyprus itself). Not only might Rimmer have read it, but also it could have inspired this figure:

The cold of winter, the ceaseless rain,

Come powerless against him; weak is the dart

Of the fierce summer sun, or fell disease

To bend that iron frame. He stands apart,

In nought resembling the vast common crowd;

But, patient and unwearied, night and day …

See chapter four for the insignia on the pole.

62 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 171. Compare to William Enfield, The History of Philosophy, from the Earliest Periods: Drawn Up from Brucker’s Historia Critica Philosophiae (London: Thomas Tegg and Son, 1837), 199, on stoicism.

63 The picture was lent, with this title, to the 1880 and 1916 Rimmer exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A related small sketch, labeled “Master Builder” by Rimmer, on a sheet of drawings (lost) exhibited in the 1916 exhibition, shows — so roughly as to be almost incoherent — a person mounting a block with at least one other figure standing behind. For this, see the glass plate photographic negative, 16B23_9, Visual Archives, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Both Fortitude and Pride are completely original personifications. While sometimes helmeted, Fortitude is apparently most often shown as a woman holding or leaning on a column, and Pride is usually a woman holding a mirror and accompanied by a peacock.

64 Bartlett, Rimmer, 128. A precursor for this use of personifications is John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, but Rimmer’s characterizations are very much his own.

65 Bartlett, Rimmer, 127. Confirming a negative reading, Weidman, Critical Catalogue, 1:577, sees the main figure as even demonic.

66 H. Winthrop Peirce, The History of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1877–1927 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1930), 54. Peirce was an MFA student under Rimmer in 1877.

67 Dante Alighieri, Dante, 2:108, canto 12, lines 34–36. Nimrod, a biblical figure who is part of extra-biblical tradition, has not yet been identified with a specific historical person. He is associated with the foundation of Freemasonry and, relatedly, Rimmer was a Freemason in Chelsea, MA, from December 20, 1865, to December 21, 1870. See page 24, line 258, in “By Laws,” Star of Bethlehem Lodge, Wakefield, MA. On Nimrod, see Laurence Dermott, Ahiman Rezon, or a Help to All That Are or Would Be Free and Accepted Masons …, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Leon Hyneman, 1855), 5.

68 A clipping of the poem, published in the Sunday Herald, and dated by hand, January 8, 1874, is included in the Rimmer Commonplace Book, Boston Medical Library. The published reference to the author is given as “R.”

69 Rather than adhere to a single moment from Act 3, Scene 1, Rimmer created his own narrative which has not been understood. At left, Prince Escalus, with his party, rushes in to find the bodies of Mercutio and Tybalt while Montague and Capulet advance from the right. The dying Mercutio raises a barely visible, phantom arm with clenched fist to damn both houses, as he did earlier, for their feuding. The foolishly perceived threat to one’s pride is at the heart of the picture, and the multi-forked dead tree refers to the result. Romeo, barely visible, is fleeing in the distance.

70 Dante Allighieri, The Divine Comedy; or The Inferno, Purgatory and Paradise, trans. Frederick Pollock (London: Chapman and Hall, 1854), 260. This is purgatory, canto 12, lines 25–27. Rimmer created an earlier, 1866, drypoint of Evening — basically the same figure — as well (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

71 For root, see, for instance, H.J. Thomas, One Hundred Short Sermons: Being a Plain and Familiar Exposition of the Apostles’ Creed; the Lord’s Prayer; the Angelical Salutation; the Commandments of God; the Precepts of the Church; the Seven Sacraments; and the Seven Deadly Sins, translated by G.A. Hamilton, with introduction by M.J. Spalding (Louisville, KY: Webb and Levering, 1859), 454.

72 See [James G. Bertram, ed.], The Language of Flowers; An Alphabet of Floral Emblems (London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1857), 15, 16, for the sunflower as signifying “adoration” and “devotion.” In this popular text that went through several editions, no flower more closely conveys spiritual love. In the drawing at bottom left is a waning moon and, in front of the temple, a branchless tree and a branching tree (both barely visible). Above the branchless tree is a garden anemone, meaning “forsaken” (ibid., 9, 18). Above the branching tree is a gable with a spire, suggesting the development of churches. Evincing his knowledge of flowers, Rimmer lectured on botanical representation at the Cooper Union (Bartlett, Rimmer, 52).

73 This follows the generally accepted date in Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 59, but the basis for Weidman’s date is an unconvincing thematic pairing of Massacre with Rimmer’s Juliet and Her Nurse (fig. 61), dated 1857. Massacre could be later than ca. 1858.

74 This is the interpretation first given in Bartlett, Rimmer, 35–36. For a different view, Massacre as an allegory of American slavery, see Randall R. Griffey, “‘Herod Lives in This Republic:’ Slave Power and Rimmer’s Massacre of the Innocents,” American Art 26 (Spring 2012): 112–25, https://doi.org/10.1086/665632. He is influenced in his reading by an acceptance of Flight and Pursuit as “enigmatic” (114) and interprets the foreground woman as a symbol of the United States (crucial to his argument) because she wears red, white, and blue. But rather than imitative of the national flag, these colors are variants, and the woman further undermines this reading by wearing a prominently displayed band of yellow. In contrast, the uselessness of an altar is a repeated theme with Rimmer and can be found as well in the background of Samson and the Child (fig. 19), a work exhibited in 1883 as “about 1854.” The scene is taken from Judges 16:26.

75 Hagar and Ishmael is undated, but Weidman gives it a ca. 1858 date, partly because he thought Rimmer’s last remaining son died in 1859 and the picture might refer to a severe illness before his death (Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 60). Horace died at one year on November 11, 1858, of “diarrhea” (“Deaths Registered in the Town of Milton for the Year 1858,” p. 200, digital images on Family Search.org). Supporting this connection, the date might be retained on the basis of style. See Bartlett’s repeated mention of faith in Rimmer, 28, 95–96 (quote), 109.

76 Satan is no. 74 in the 1883 catalogue of Rimmer drawings, J. Eastman Chase Gallery, Boston (Boston Public Library file on Rimmer). For a painted Mephistopheles, see the “Dec. 22, 1872” Boston Herald clipping in the Clipping Scrapbook of Mary H.C. Rimmer, Boston Medical Library. See also Bartlett, Rimmer, 124–25, 76, and, for the Christian subjects, ibid., 19–20, 29–31. See the contrasting hair color in Rimmer’s Madonna and Child (private collection), reproduced in Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 53, fig. 15. The Magdalen is stylistically close to this unfinished Madonna and Child, with a somewhat square head akin to the imaginary heads of women by Washington Allston. The hands are not the undersized women’s hands from the 1850s. Instead, the head and hands are closer to their counterparts in the 1877 Art Anatomy. The misidentification of Magdalen is probably because the figure resembles that in a drawing, fig. 44, labeled Madonna, in Bartlett, Rimmer.

77 See a different interpretation in Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 78, where Sleeping is considered Rimmer’s “most intensely erotic work.” The title is on the reverse, evidently written by Rimmer’s daughter, Caroline. A pencil inscription on the reverse appears to read: “One of my Dear Father’s Best paintings / & it is a perfect Shame the Varnish is / not good and I suppose will be sticky / always.” In the past, it has been given a late date, ca. 1878, because the word “Best” has been misread as “last.” Sharing a bitumen problem (a cause of stickiness) with the 1871 English Hunting Scene, it could be from that time; it is convincing as a wholly imaginary image, possibly influenced by remembrance of his daughters as children.

78 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 95.

79 The title is from Rimmer’s poetic inscription below the image which continues: “Out of Eternity into Time.”Appropriately there is a rising sun below the wings. The concept of wings must come from a description in Psalm 57:1 of taking refuge in times of calamity in the shadow of God’s wings and from Psalm 63:7: “Because thou hast been my help, therefore in the shadow of thy wings will I rejoice.” Weidman dates the drawing 1869, which is possible, but there is no basis for an exact date, and it could be much earlier or later. See Weidman, Rimmer: Critical Catalogue, 3:959.

80 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 326.

81 Ibid., 335, for quote. See also Emanuel Swedenborg, whose work Rimmer read (see chapter four), where he repeatedly makes the point that the angels in the highest or inmost heaven are naked because nakedness corresponds to innocence (Swedenborg, Heaven and Its Wonders and Hell: From Things Heard and Seen (1867. Reprint, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1890), 112, 174.

82 For flesh, see Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 381; for similar thinking, see ibid. [8]. See also Bartlett, Rimmer, 32, for Rimmer commenting on such a duality. Rimmer’s statement is a paraphrase of Emanuel Swedenborg’s On the Intercourse between the Soul and the Body Which Is Supposed to Take Place Either by Physical Influx, or by Spiritual Influx, or by Pre-Established Harmony (Boston: Otis Clapp, 1848), 25–26.

83 Bartlett, Rimmer, 125. The severed arms represent pain and condense the composition. Rimmer used this device to eliminate detail in his Art Anatomy, 105, 146–49. Weidman, Critical Catalogue, 1:342–43, 339–40, and Weidman, et al., Rimmer, 43, see the sculpture as symbolically multi-layered, including references to Rimmer’s career and the Civil War.

84 Rimmer, “Stephen and Phillip,” 377.

85 Ibid., 153. The furrowed brow is clearer in the original plaster.

86 Ibid., 245.

87 Bartlett, Rimmer, 67. For the influence of Darwin and others on Rimmer’s typology, see Elliott Bostwick Davis, “William Rimmer’s Art Anatomy and Charles Darwin’s Theories of Evolution,” Master Drawings 40 (Winter 2002): 345–59.

88 His students knew of his interest in past English poets. For this, see Bartlett, Rimmer, 42.

89 Edward Young, The Complete Works, Poetry and Prose, of the Rev. Edward Young, revised with a life of the author by John Doran (London: William Tegg, 1854), 2:439. The reference could have been recognized in Rimmer’s day, but it was not known by Bartlett.

The typical response was to admire the artist’s skill (Bartlett, Rimmer, 124, 136). Edward J. Nygren first connected the sculpture with Young in a 1969 graduate paper under Jules Prown at Yale University, but his find has not been sufficiently valued. See Weidman’s essay on Rimmer’s Dying Centaur in Ruth Butler, Suzanne Glover Lindsay, et al., European Sculpture of the Nineteenth Century (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2000), 448.

90 Young, Centaur, 2:453.

91 For greater clarity in a “modernized” edition (title page): see Edward Young, The Centaur, Not Fabulous, abr. and rev. with notes by L. Carroll Judson (Philadelphia: G.B. Zieber and Co., 1846), 142, on death; 38 for the quote.