2. A CYCLE OF RĀGS: RĀG SAMAY CAKRA

©2024 David Clarke, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0313.02

Performers:

Dr Vijay Rajput (khayāl vocalist)

with

Ustād Athar Hussain Khan (tabla)

Ustād Murad Ali (sāraṅgī)

Ustād Mahmood Dholpuri (harmonium)

2.1 The Album and Its Supporting Materials

Our first album, Rāg samay cakra, presents fourteen Hindustani rāgs in the khayāl vocal style, performed by Dr Vijay Rajput (henceforth VR), a vocalist of the Kirānā gharānā (stylistic lineage). With his accompanists, VR takes the listener through a cycle (cakra) of rāgs ordered according to their designated performing times (samay): from the dawn rāg Bhairav to the midnight rāg Mālkauns (for a visual representation see Figure 1.6.2). As well as being identified with times of the day and night, rāgs are also associated with times of the year; and so the sequence ends with two seasonal rāgs: Megh, a rāg for the monsoon season, and Basant, a springtime rāg which may also be sung in the final quarter of the night. These performances are followed by supplementary tracks in which VR provides spoken renditions of the texts of the songs sung in each rāg. This is intended to help students who are not Hindu/Urdu speakers achieve correct pronunciation. The music was recorded in New Delhi in 2008; the spoken texts at Newcastle University in 2017, where the producer was David de la Haye.

All the performances on Rāg samay cakra take the form of an ālāp and choṭā khayāl—literally ‘small khayāl’. We gave a thumbnail account of these performance stages in Section 1.7, but what follows is a further concise gloss.

In an ālāp, the soloist’s job is to establish the rāg—its mood, its colours, its characteristic melodic behaviour. Listening to an ālāp is almost like overhearing an inner contemplation; the tabla is silent, so the vocalist has licence to extemporise, without being tied to any metre—an approach to rhythm known as anibaddh (similar to senza misura in western music). By contrast, the ensuing choṭā khayāl is based around a short song composition (bandiś), and is sung in a rhythmic cycle (tāl) supported by the tabla—which means the rhythmic organisation is metrical (a condition termed nibaddh); the dynamic is interactive and accumulative. Hence, the overall trajectory—from the meditative beginnings of the ālāp to the climactic closure of the choṭā khayāl—is a journey from ruminative inwardness to extravert exuberance.

As its name suggests, a choṭā khayāl is a vehicle for shorter performances in this style. Even so, there is plenty of space for elaboration: not uncommonly a choṭā khayāl will extend to around ten minutes—as on our second album, Twilight Rāgs from North India (Tracks 3 and 6). But it is also possible to give a satisfying and idiomatic rāg performance, including an ālāp, in around five minutes, as VR does throughout Rāg samay cakra. Because it is ostensibly simpler to master than the majestic, slow-tempo baṛā khayāl, a choṭā khayāl is usually what khayāl singers first learn to perform. Hence, we intend that these compressed performances will be of value to students in the earlier stages of learning. But we hope that they will inspire more advanced students too. For a choṭā khayāl presents its own challenges: it is usually sung up-tempo, at a speed ranging from medium fast to very fast—hence is also known as a drut khayāl (fast khayāl). This means the singer has to keep their wits about them through many extemporised twists and turns in which they interact with their accompanying artists; and physical as well as mental agility is required for the rapid delivery of virtuosic features such as tāns.

In Section 2.5 we provide supporting materials for each rāg of the album—namely:

- A description of the rāg, including a technical specification and an outline of its musical and aesthetic characteristics.

- A transliteration and translation of the bandiś text, as well as its original Devanāgarī version.

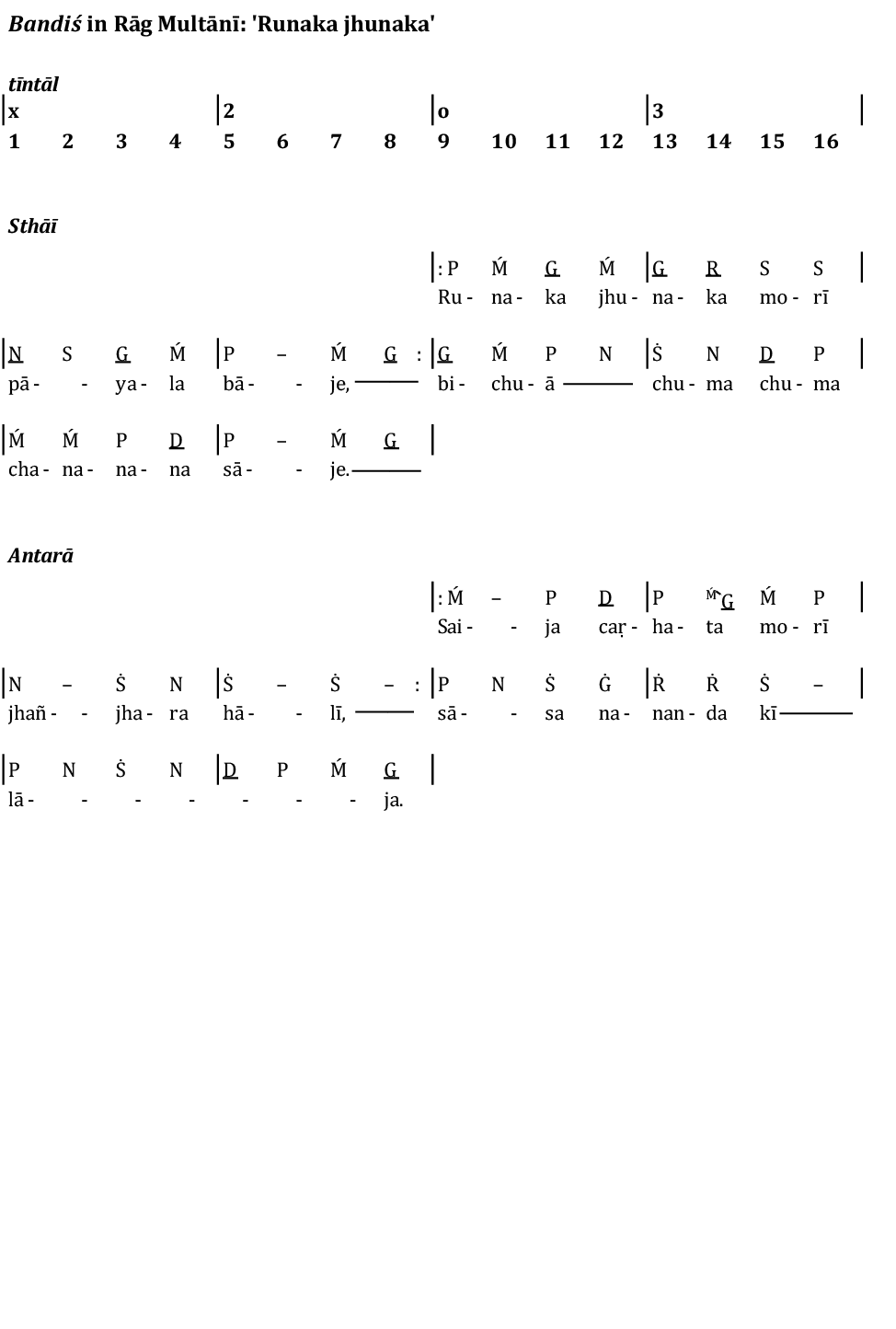

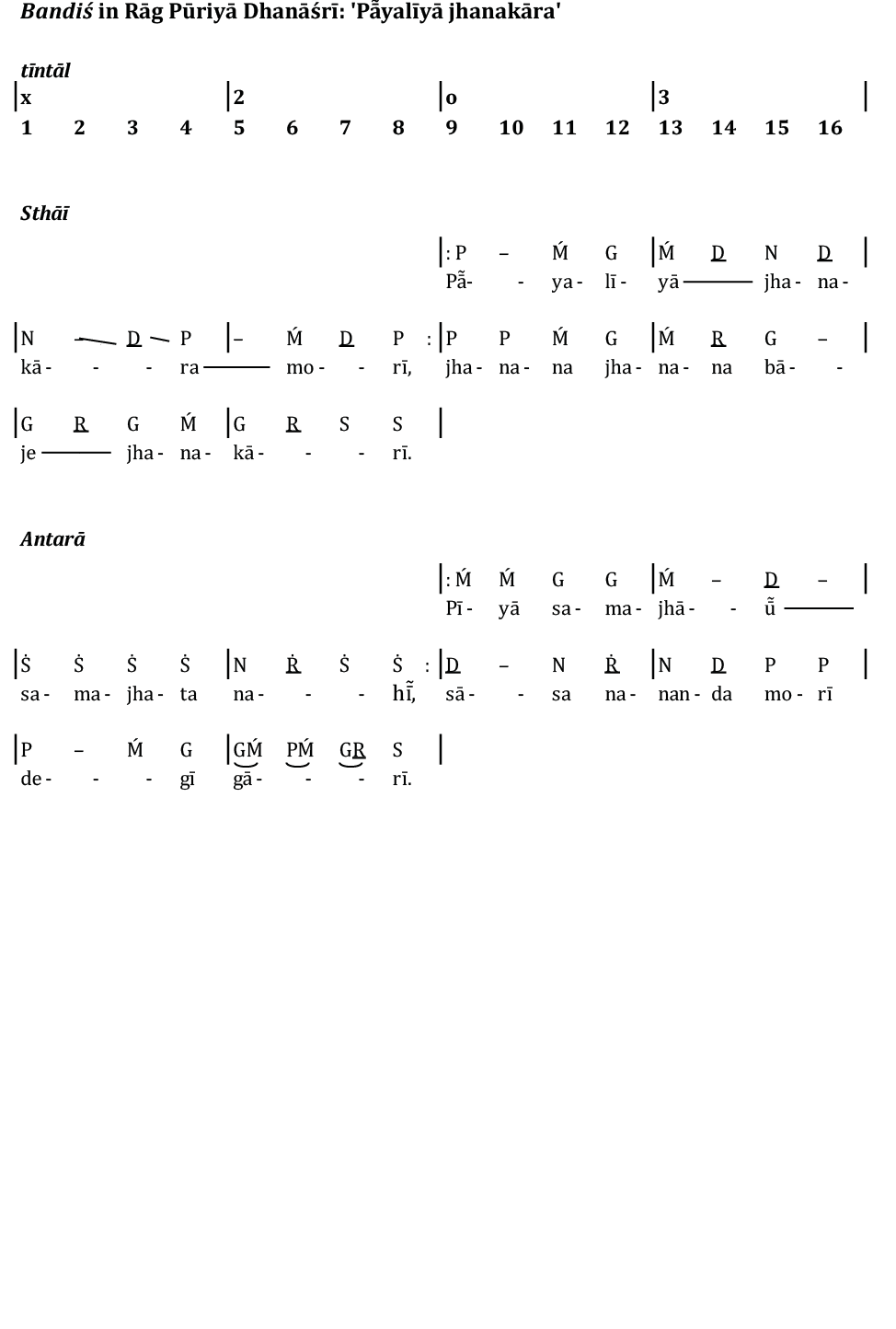

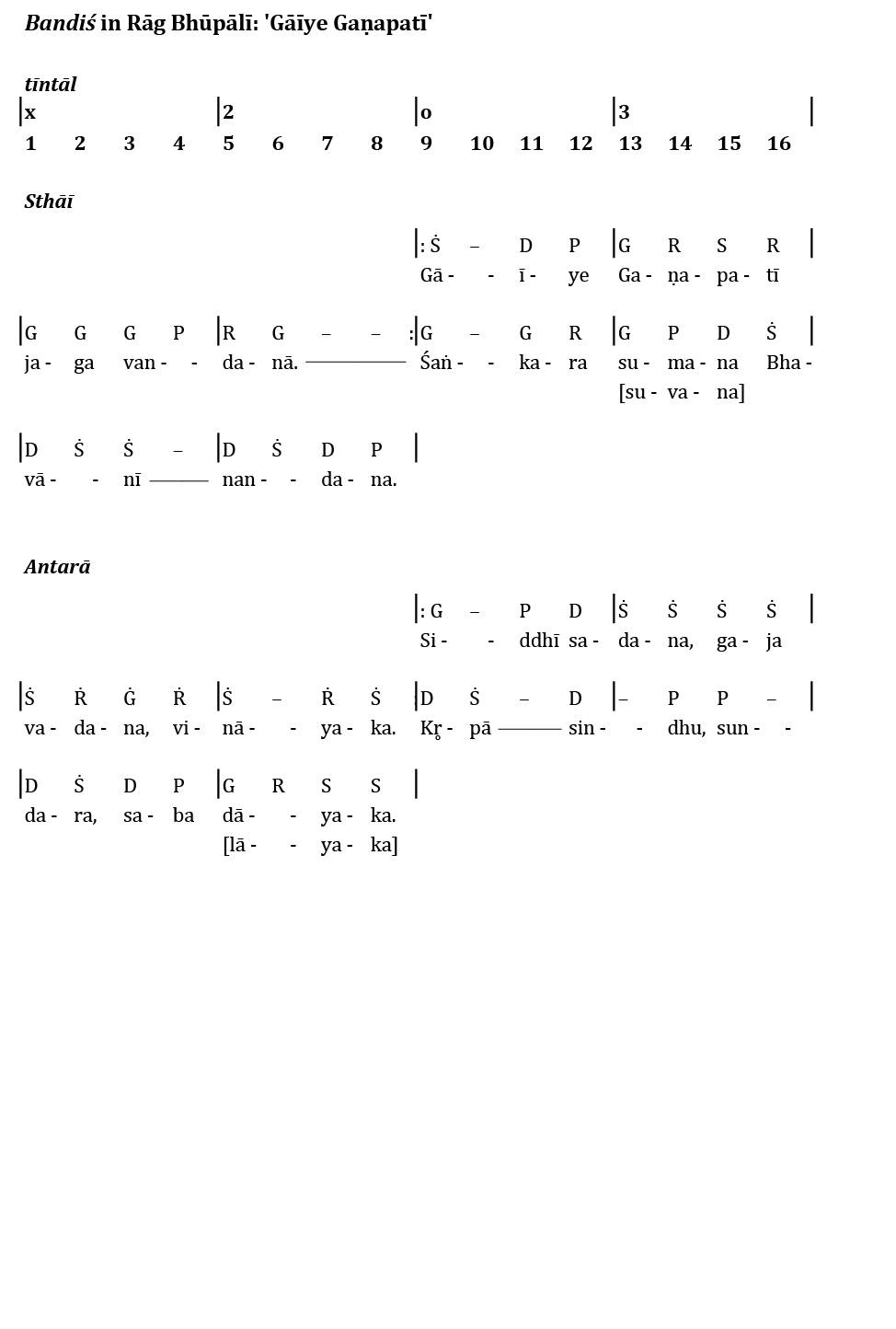

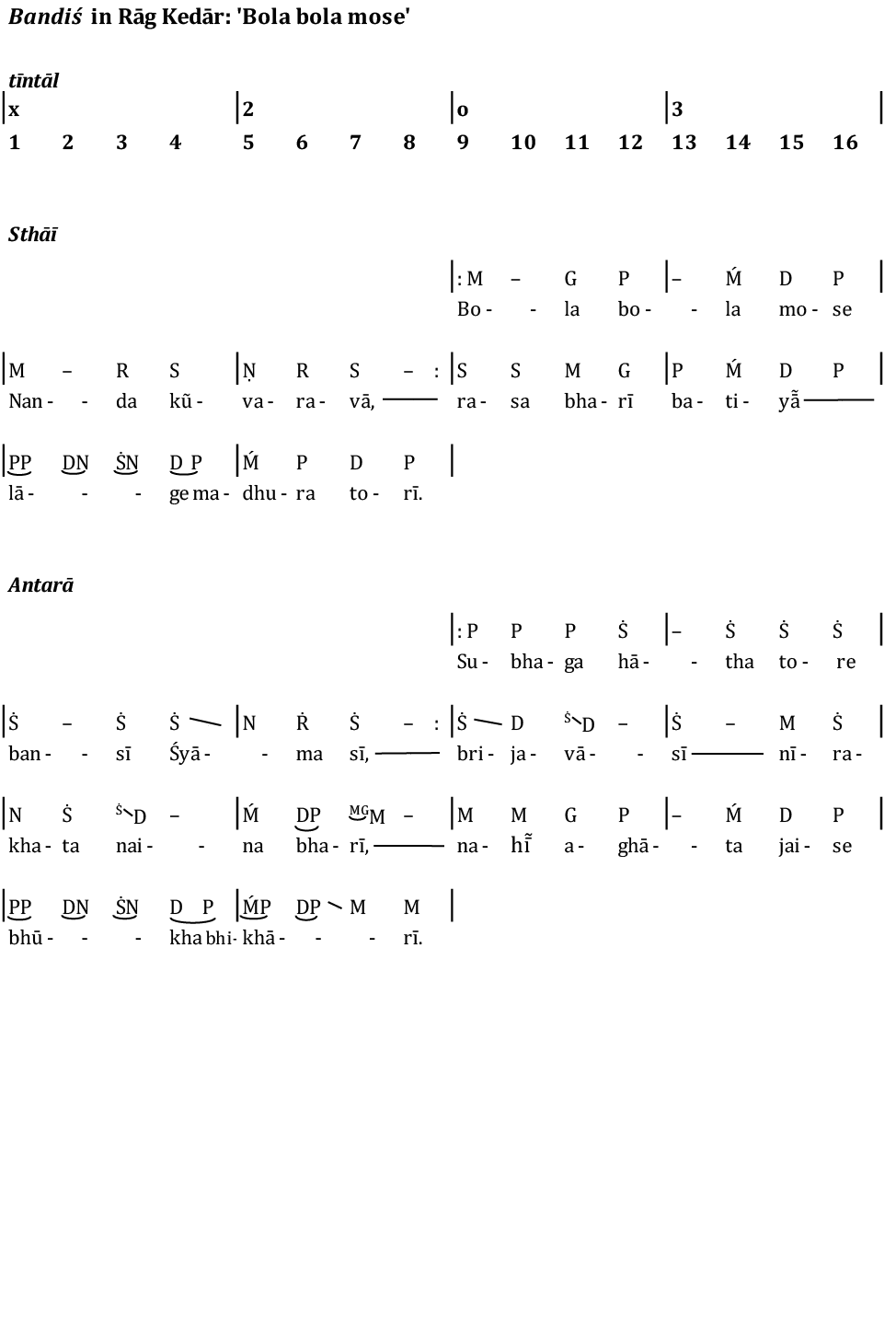

- A sargam notation of the bandiś (composition).

In the intervening sections, we provide writings that help elucidate these materials. In Section 2.2 (relating to (2), above), we consider the poetic characteristics of the song texts, as well as the problematics of trying to produce any kind of definitive version of them; we also discuss conventions relating to their transliteration and pronunciation. In Section 2.3 (relating to (3), above) we explore issues to do with the musical notation of the bandiśes, given that historically they have been transmitted orally; we also provide information about the musical notation conventions applied in this book, and about how the bandiśes as notated relate to their delivery in actual performance. Finally, in Section 2.4 (relating to (1) above), we give a brief explanation of the technical terms used in the rāg specifications.

2.2 The Song Texts

Language and Poetics

Khayāl songs have a style and language all of their own—a point that Lalita du Perron drives home in her richly detailed account in The Songs of Khayāl (Magriel and du Perron 2013, I: 201–50). Even though, in the heat of performance, the words of khayāl compositions may get submerged under waves of invention and virtuosity, the texts remain important. They offer keys to the mood of a bandiś, and can spark the singer’s imagination (the meaning of the word khayāl, let us recall). Hence, in our commentaries on the individual rāgs of Rāg samay cakra below (Section 2.5), we have extracted the bandiś texts, along with their translations, so that they can be perused in their own right, and so that students can familiarise themselves with them prior to, or in tandem with, learning the song melody.

A definitive version of a khayāl text is no more possible than a final version of its melody. Both are subject to mutation under oral transmission; both are susceptible to the vagaries of memory and imagination. Any individual artist may carry several variants of both tune and text in their head. Another challenge comes from the language itself. Khayāl songs are found in a range of North Indian regional languages and dialects, which may be related to Hindi but which do not take its modern standard form. Prominent among these is Braj Bhāṣā, which achieved status as a vernacular literary language between the late medieval era and the nineteenth century (Snell 1991), and continues to have currency in present-day musical genres such as khayāl, ṭhumrī and dhrupad. Mutabilities of phonology, grammar and spelling all add to the challenge of stabilising form and meaning. Further, there are the often allusive and ambiguous meanings of khayāl poems, which seldom exceed four lines and display numerous other stylistic idiosyncrasies (again, see du Perron’s account).

Many of the common devotional and romantic tropes of khayāl poetry are illustrated in the texts of Rāg samay cakra. These include the veneration of deities; the pain of romantic separation; the entreaties of a lover; night-time assignations (and fear of being heard by the mother- or sister-in-law); images of nature (including birds, bees and mango trees); and celebrations of the seasons (notably springtime and the monsoon). Kr̥ṣṇa, typically depicted playing his flute, is often centre stage or rarely far from the scene. He is regarded as a figure who brings the divine and romantic into union. When not being adored by all, he is frequently seen being scalded by his consort, the gopī (cowherd) Rādhā, for his teasing, for his frequent absences, and for his assignations with a rival (sautan). Many of the song texts are sung from a female standpoint, and while Rādhā is rarely named as such, she is implicitly the archetype behind many of these songs of love and longing for the divine.

Transliteration and Pronunciation

Our edition of the texts has been a collaborative venture (where, inevitably, the roles have blurred a little). Initially, a Devanāgarī (देवनागरी) version of the bandiś texts was supplied by VR from his performer’s perspective. This was then transliterated into Roman script by David Clarke (henceforth DC) and passed on to the translators; unless otherwise indicated, the English translations were composed by Jonathan Katz and Imre Bangha. Versions were then passed back and forth between collaborators, resulting in further modifications and refinements.

The oral transmission of khayāl songs militates against any would-be final version of their texts. Performers might not sing every detail of the text as they would write it, nor write down the text (if they do so at all) exactly as they sing it. Sometimes the sounds of the words may take them in one direction while their possible meaning may lead a translator or editor in another. In our edition, alternatives to the actually sung version are shown in square brackets; conversely, round brackets are used for words that are sung, but which depart from the textual version.

In aiming for a scholarly transliteration from Devanāgarī into Roman script we have followed the conventions of IAST, the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, a subset of ISO 15919 (see also the discussion above in Transliteration and Other Textual Conventions). Through its use of diacritics—dots, lines and other inflections above or below individual letters—this system provides a unique Roman counterpart for every Devanāgarī character. This may look a little more complicated or fussy than informal approaches to romanising Hindi or Urdu used in everyday vernacular practice, but it is simply more fastidious and does not take long to master; moreover it is helpful to singers in achieving correct pronunciation.

This is because IAST makes it possible to discriminate between closely related but distinct Hindavi (Hindi/Urdu) sounds in a way that is not possible with only the normal twenty-six characters of the Latin alphabet. For example, unlike English, Hindavi has two distinct ‘t’ sounds: dental, with the tongue pressed against the front teeth; and retroflex, with the tongue against the roof of the mouth. In Devanāgarī script (used for Hindi and Sanskrit, among other languages), these are written as त and ट, and are transliterated as t and ṭ respectively. The same goes for the ‘d’ sounds द and ड, transliterated as d and ḍ. (For an admirably pragmatic online guide to Devanāgarī transliteration, see Snell 2016.)

We do not indicate every aspect of pronunciation here, but the following are particularly pertinent:

- A macron (line) over a vowel indicates the sound is lengthened—hence ā = ‘aa’, as in ‘bar’ in Standard English; ī = ‘ee’, as in ‘teen’; ū = ‘oo’, as in ‘loom’.

- A tilde (wavy line) over a vowel—for example, ã, ĩ, ũ—indicates nasalisation.

- A dot over an n—as in ‘Sadāraṅg’—also indicates nasalisation.

- C is pronounced ‘ch’, as in ‘cello’ or ‘church’.

- Ś and ṣ are both pronounced ‘sh’—as in the English ‘shoot’.

- J is pronounced as in ‘January’ or ‘jungle’.

- H after a consonant—for example, bh, dh, kh—indicates that it is aspirated, i.e. pronounced with an additional puff of air.

- The underlined character kh—as in khayāl—is pronounced further back in the throat than its non-underlined counterpart; these sounds are peculiar to Urdu words of Persian or Arabic origin.

- The short vowel a (known as schwa by phoneticists) is pronounced further forward in the mouth than the longer ā—especially when sung (see Sanyal and Widdess 2004: 173, n. 17). Hence ‘pandit’ is pronounced slightly like ‘pundit’, ‘tablā’ slightly like ‘tublā’.

For more comprehensive guidance on pronunciation, readers should consult a primer such as Rupert Snell’s excellent Beginner’s Hindi (2003: viii–xviii) or the Hindi section of the website Omniglot, an online encyclopaedia of writing systems. Additionally, the transliterated song texts can be studied in conjunction with the recorded spoken renditions by VR found alongside the rāg recordings.

One further technicality should be noted. Spoken Hindavi, unlike Sanskrit, often suppresses an implicit ‘a’ vowel after a consonant (a process termed schwa deletion). This is especially common at the end of a word—hence the Sanskrit ‘rāga’ is pronounced ‘rāg’ in Hindavi. However, in sung Hindavi, and in dialects such as Braj Bhāṣā, such suppressed vowels are not silenced; indeed their enunciation is often essential to the metrical structure of Braj poetry and song (see Snell 2016: 3–4). Hence, on the advice of our translators, we have included the normally suppressed a in our transliteration of the song texts—for example, ‘dhan dhan murat’ is sung (and hence transliterated) as ‘dhana dhana murata’; similarly, ‘hamrī kahī mitvā’ as ‘hamarī kahī mitavā’.

2.3 Notating the Bandiśes (and Performing Them)

Prescriptive or Descriptive Music Writing?

Given that Hindustani classical music is primarily an oral tradition, its notation—while useful for teaching and musical analysis—raises a number of issues. In this regard, it will be useful to invoke the ethnomusicologist Charles Seeger’s (1886–1979) well-known distinction between ‘prescriptive and descriptive music writing’ (Seeger 1958). The former type, typified by western staff notation, supplies instructions to the performer that are essential in rendering a piece. The latter, typically used in ethnomusicological transcription seeks to detail a record of musical sounds and events as actually rendered—which may be useful in documenting and scrutinising performances from non-notating cultures.

An exemplary use of descriptive notation can be found in Volume II of Nicolas Magriel and Lalita du Perron’s The Songs of Khayāl (2013). Using an inflected sargam notation, Magriel seeks to capture every nuance of ornamentation and note placement in classic khayāl recordings. His aim is to illustrate—and in effect analyse—the mastery of the genre’s greatest historical exponents, as found in their recorded legacy. By contrast, our approach in Rāgs Around the Clock is more prescriptive and heuristic. Our aim is generally to notate a simplified outline of a song (bandiś) to assist students in learning it (though on some occasions it will be useful to present more fully detailed descriptive notations of what VR actually sings).

For an authentic version of a bandiś, students will need to listen to their guru or ustād demonstrate it multiple times—either live or, as with Rāgs Around the Clock, in recorded form. Our (prescriptive) notation of the songs sung on Rāg samay cakra acts as nothing more (or less) than a pedagogical aide memoire, and largely corresponds to the on-the-spot sketch a student might make during their lesson. What is omitted is as significant as what is included. What is notated are the essentials. What is not notated are the stylistic nuances heard in the actual musical renditions—which is where VR’s gāyakī—his distinctive style—is audible. Paradoxically, the abstraction of the notation helps make salient the nuances of the songs as actually sung, by their very absence.

Even in the short performances captured on Rāg samay cakra, one can often hear multiple variants of a bandiś, richly exceeding the simplified notation. Sometimes the sung version may only begin to conform to the notated one later in the performance; sometimes the notation may represent a composite distilled from different moments; sometimes what is notated may never be directly rendered as such but could be considered as a model of the song operating at the back of the performer’s mind as they deliver it; or it may conform to a version transmitted and notated on a different occasion, which may be no less—or no more—‘definitive’. So, rather than representing an idealised version of a bandiś, our notations form a practical or heuristic reference point that itself may transmute over time.

Notation Conventions

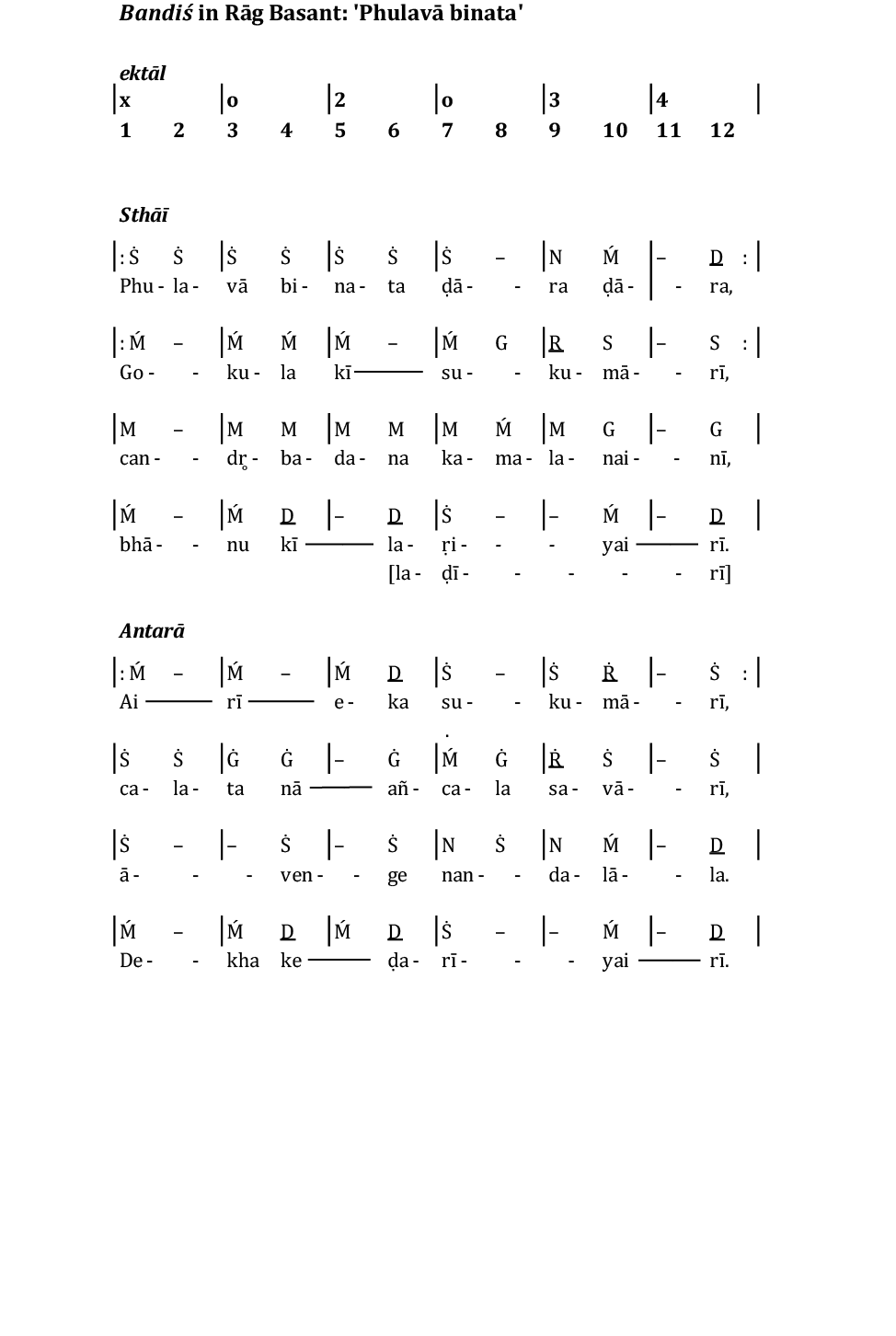

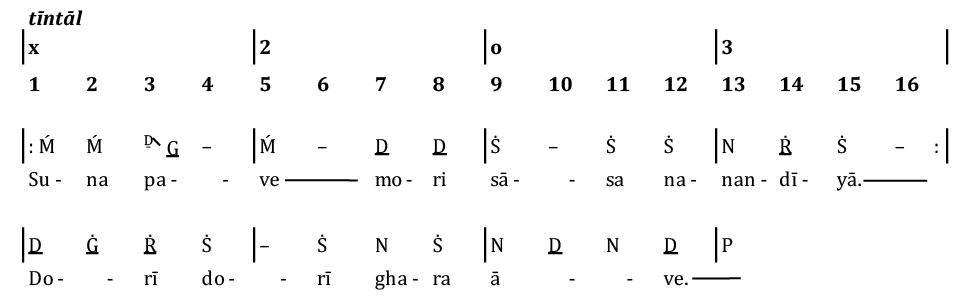

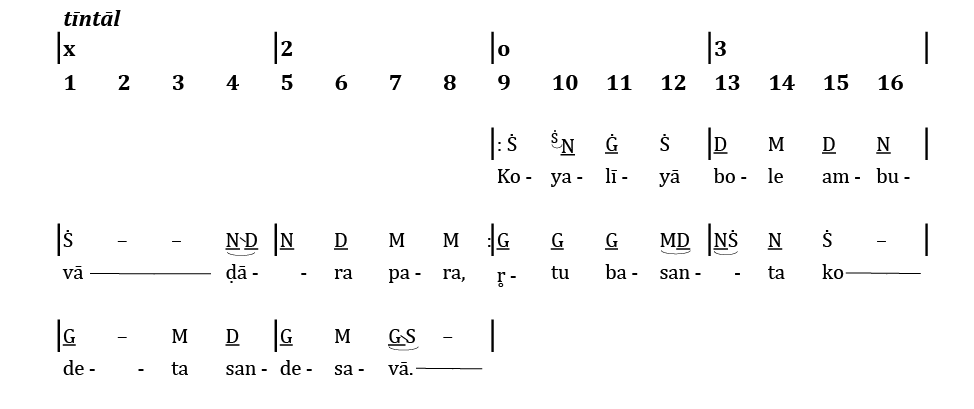

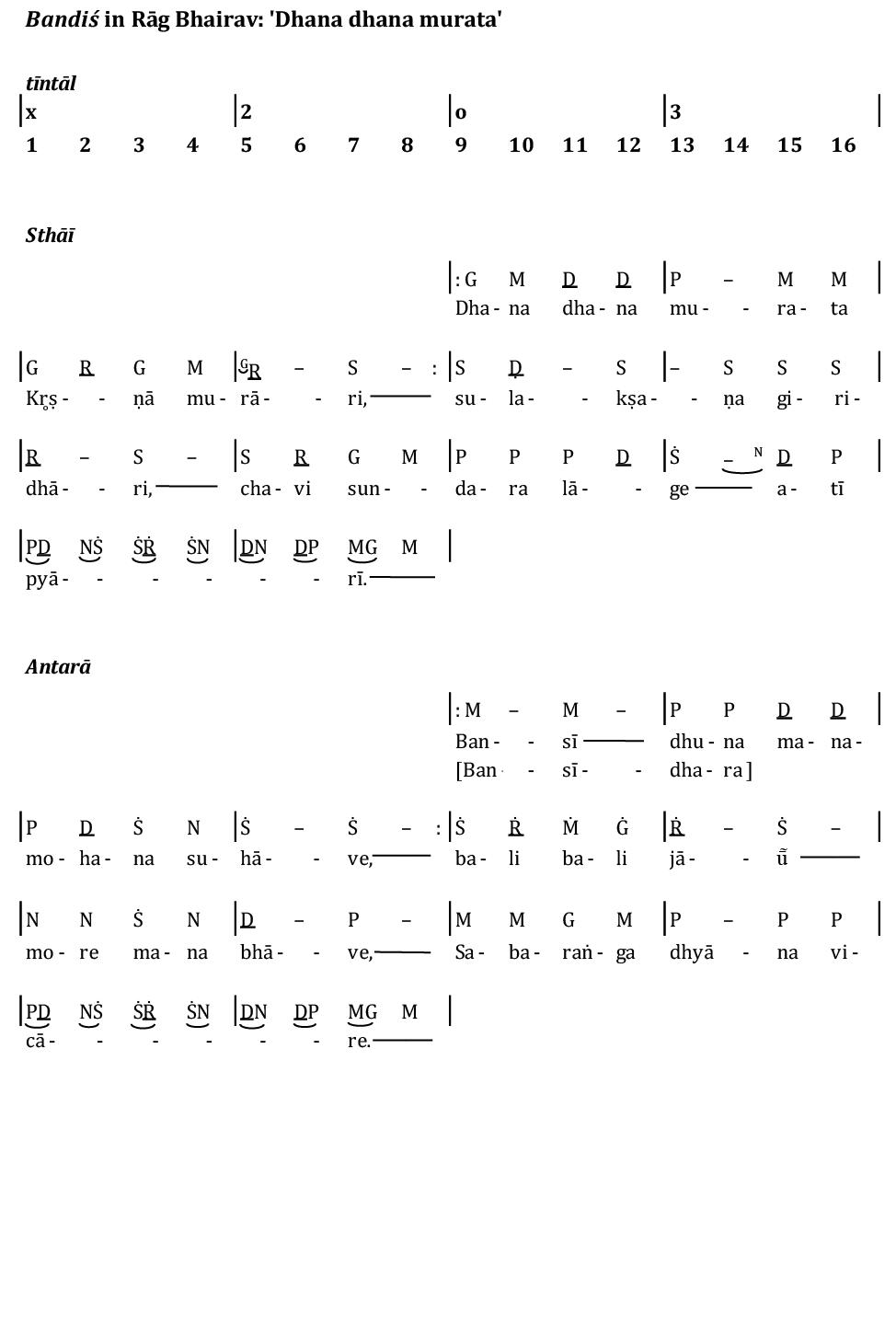

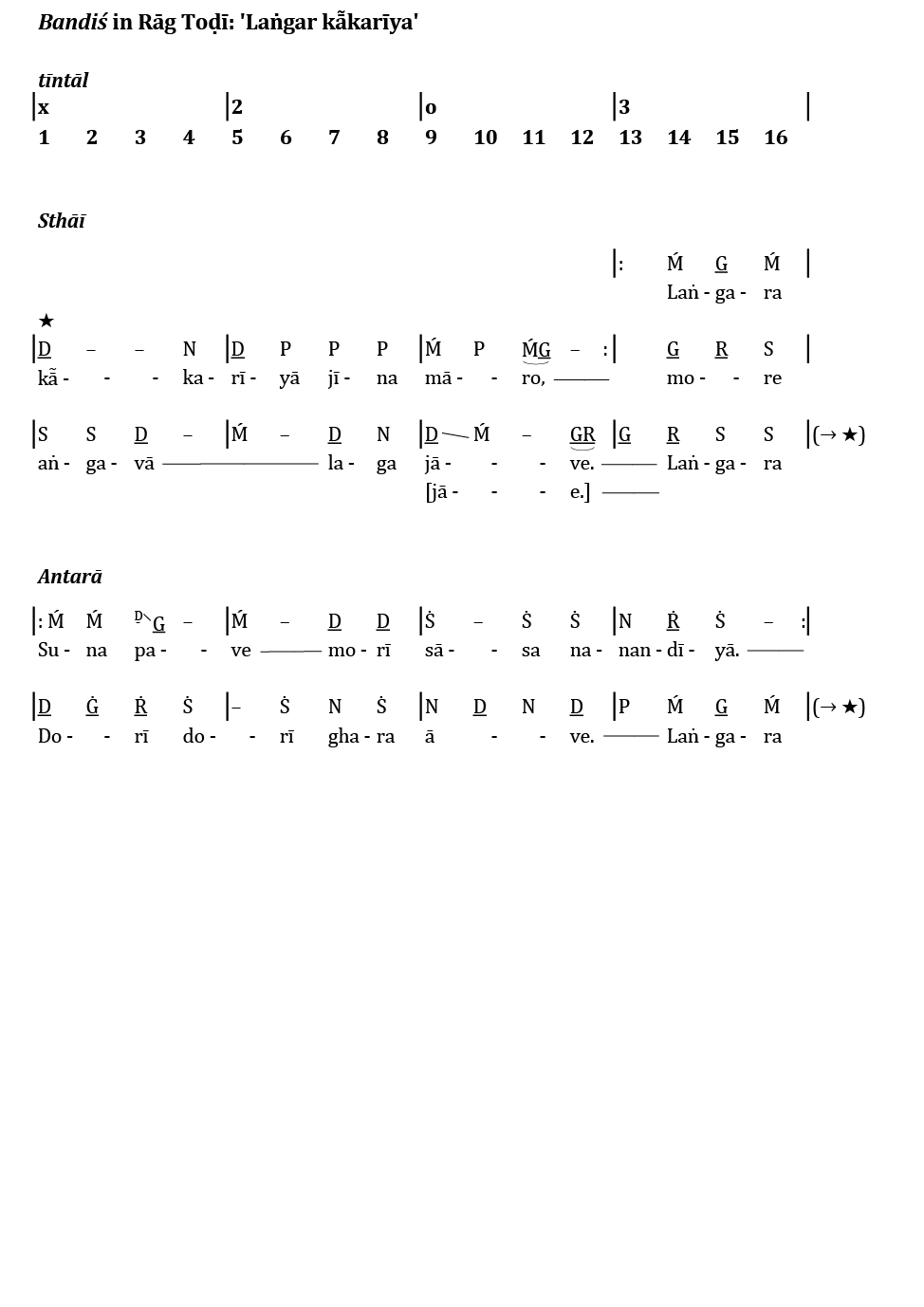

To notate the songs from our collection, we have developed a version of Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande’s (1860–1936) music writing system, as found, for example, in his multi-volume Kramik pustak mālikā (1937), and informally applied by many Hindustani musicians. Although it would have been relatively straightforward to have made transcriptions using western staff notation, we have resisted that temptation, since it is not part of the currency of Indian music, and would bring with it a welter of distorting connotations (a point which resonates with Magriel’s comments in Magriel and du Perron 2013, I: 91–2). The Bhatkhande-derived notation used here is, in any case, easy enough to decipher. Let us consider the example in Figure 2.3.1, which quotes the antarā (second part) of the famous Toḍī bandiś, ‘Laṅgara kā̃karīyā jīna māro’—as sung by VR on Track 2 of Rāg samay cakra (from 04:14).

Fig. 2.3.1 Bandiś in Rāg Toḍī: notation of antarā. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Each row of the notation represents one āvartan (cycle) of the tāl—in this case the 16-beat tīntāl. Individual beats (mātrās) are numbered in bold at the head of the notation on a horizontal axis. Vertical lines (broadly similar to barlines in western notation) mark off the subdivisions (vibhāgs) of the tāl; in the case of tīntāl, there are four vibhāgs, each lasting four mātrās. The clap pattern for the tāl is also shown according to convention: sam (the first beat) is indicated with ‘x’, khālī with ‘o’, and other clapped beats (tālī) with consecutive numbers.

The notes of the melody are given above the text, using the abbreviated syllables of sargam notation. A dot above a note name indicates that it is performed in the upper octave; a dot below, in the lower octave. Flat (komal) scale degrees are shown by underlining the note name (for example, R = komal Re); the sharpened fourth degree, tivra Ma, is indicated with a wedge above the note name (i.e. Ḿ). Dashes signify that a note is sustained through the following beat(s). Oblique lines (/ or \) indicate a glide (miṇḍ) upwards or downwards between notes.

Superscripted note names are used for ornaments (discussed further at the end of this section). Since khayāl performances are often replete with subtle ornamentation and pitch bends, these are shown sparingly, in order not to clutter the notation; as stated above, our aim is not to capture every tiny detail of the performance but to convey the basic outline of the song for practical learning purposes.

The first line of both parts of a bandiś (sthāī and antarā) is conventionally repeated. To signal this, we apply repeat mark signs (: :) from western staff notation. While subsequent lines may also be repeated, and while the first line itself may be repeated several times over (often with variations), this is not usually indicated, since the matter is largely dependent on the context of any given performance and on the performer’s mood.

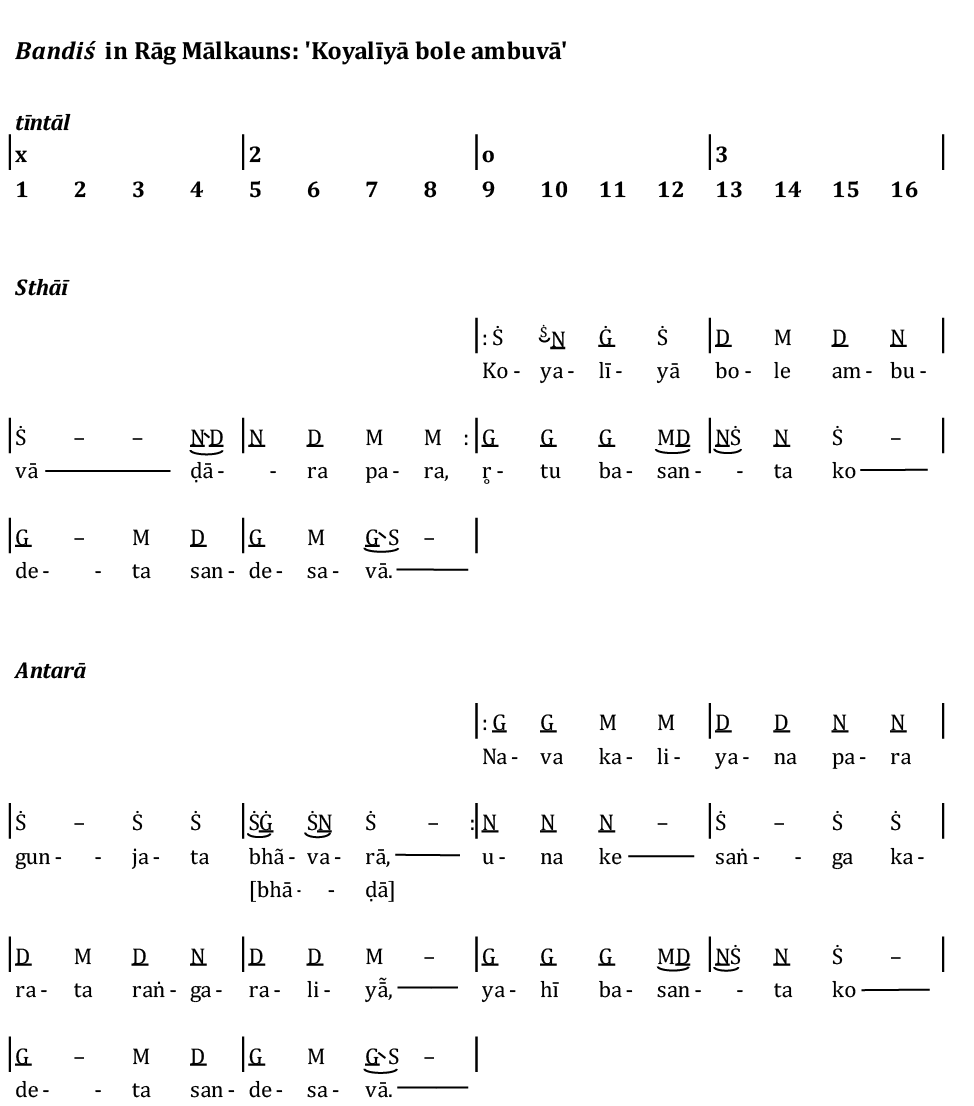

Typically of the khayāl style, all the tīntāl bandiśes in our collection begin not on sam, the first beat, but with a lead-in of several beats. (Although the antarā cited in Figure 2.3.1 does begin on sam, this is quite rare, and, in any case, the sthāī which opens the same bandiś begins on beat 14.) Not uncommonly, songs start on beat 9 (khālī), but they may begin earlier or later. Hence, the poetic lines of a song often straddle the rhythmic notational framework. This can be seen in Figure 2.3.2, which quotes the sthāī of the composition ‘Koyalīyā bole ambuvā’ in Rāg Mālkauns (Track 12 of Rāg samay cakra (from 03:28)). Here, the two lines of the stanza each extend from khālī to khālī.

Fig. 2.3.2 Bandiś in Rāg Mālkauns: notation of sthāī. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

This figure also illustrates the use of bowed lines (like slurs in western notation) beneath note names to show notes grouped within a beat. For example, on beats 12 and 13 of the second line there are two notes per beat; and since notes grouped this way are normally sung more or less evenly, we can surmise that each note lasts half a beat. (In western terms, if a beat were represented by a quarter-note or crotchet, these would be equivalent to eighth-notes or quavers.) Furthermore, throughout the notations, bowed lines are also used to connect decorative notes (shown superscripted) to the note they are decorating. In Figure 2.3.2 this can be seen on beat 10 of the first line, where a kaṇ (grace note) on Ṡā is grouped in with the main note, Ni.

From Notation to Performance

Finally, there is the question of how a bandiś as notated is deployed in performance—what, actually, do you do with this material; which portions of it do you sing when? Although the notations in this volume are, generally speaking, prescriptive, they do not unambiguously specify the order of things. Learning how to integrate the different components of a bandiś into a full khayāl performance takes time to learn, but here are some initial rules of thumb:

- Begin your choṭā khayāl with the sthāī of the bandiś. It is customary to repeat the first line—usually once, but possibly several times, depending on context.

- After the first line, sing the rest of the sthāī. The second line can also in principle be repeated, depending on the character of the composition, though this is less common than repeating the first line. Any further lines are usually sung only once.

- Once you have sung the complete sthāī, reprise the first line.

- The antarā follows similar, though not identical, conventions to the sthāī. The first line is usually repeated, other lines are less likely to be so. After the final line, you should return directly to the first line of the sthāī.

- You may sing the antarā immediately after the sthāī or save it for later, while you improvise other material.

The improvisation of material can in fact apply to just about any stage of a performance. This is necessary because, while a bandiś usually takes little more than a minute to sing, a choṭā khayāl (even a compressed one) should last significantly longer: it is expanded through a variety of devices, such as bol ālāp, tāns and various forms of laykārī. But, throughout, the bandiś acts as the glue of the performance—the Hindi term carries the connotation of binding together (Ranade 2006: 71–4). For example, the first line of the sthāī usually acts as a refrain between developmental episodes; and the antarā may be revisited at a later stage.

The question of how to develop a khayāl is one of its key challenges. Ultimately this must be learnt from the guidance of one’s teacher and the example of professional performances. While further discussion of this matter is beyond the scope of the present section, I will revisit it later in Rāgs Around the Clock, in Section 3.3, entitled ‘How Do You Sing a Choṭā Khayāl?’. There, through a detailed analysis of VR’s performances on Rāg samay cakra, I arrive at an expanded set of rubrics for performance, developing the ones sketched out above, and ultimately conjecturing whether all this might point to an implicit performance grammar for khayāl. But that more complex discussion is for later: for now, the above rules of thumb provide a starting point for how to apply the notations of Section 2.5 in practice.

2.4 Terminology Used in the Rāg Specifications

The description of each rāg in Section 2.5 begins with a technical specification of its key features. Unless otherwise indicated, we derive these thumbnails from Bhatkhande’s Kramik pustak mālikā (1937), making his version of the information available probably for the first time outside the Marathi and Hindi editions of his opus. Page references to the relevant passages are given for each entry. Below, we provide a gloss on the terminology used:

Āroh–avroh—the ascending and descending form of the scale on which the rāg is based. Often this amounts to more than proceeding directly up and down: the representation may also capture the twists and turns of the scale along its path, according to the rāg. Bhatkhande uses commas to segment the scale formations, and sometimes plays with typographical spacing—presumably in order to reflect the rāg’s grammar. These conventions are reproduced in our own specifications, although exactly what Bhatkhande means by their layout is sometimes opaque.

Pakaḍ—a quintessential phrase of the rāg, which captures its key features and syntax. Again, we emulate Bhatkhande’s use of commas and spacing in the notation—with the same caveat as above.

Jāti—literally ‘class’, ‘genus’ or ‘caste’. This is defined by the number of different pitch classes in the ascending and descending scale forms of the rāg:

The jāti expresses the ascending and descending forms as a pair—for example:

- Auḍav–ṣāḍav = five notes ascending, six-notes descending.

- Sampūrṇ–sampūrṇ = seven notes ascending and descending.

Ṭhāṭ—literally ‘framework’ (also used to signify the sitar fret setting for a rāg). This identifies the parent scale of the rāg according to Bhatkhande’s ṭhāṭ system, which arranges Hindustani rāgs into ten families distinguished by their different permutations of natural, flat and sharp scale degree (see Figure 1.3.1, above).

Vādī—the most salient note in a rāg, usually considered in conjunction with saṃvādī.

Saṃvādī—the next most salient note, usually four or five steps higher or lower than the vādī note. In other words, vādī and saṃvādī belong to complementary tetrachords of the scale of the rāg: one in the lower tetrachord (pūrvaṅg), the other in the upper (uttaraṅg).

2.5 The Rāgs

2.5.1 Rāg Bhairav

Performing time first quarter (prahar) of the day.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

||||||

|

S R G M, |

P D, |

N Ṡ |

Ṡ N D, |

P M G, |

R, |

S |

|

Pakaḍ – S, G, M P, D, P

Jāti – Sampūrṇ–sampūrṇ (heptatonic–heptatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Bhairav

Vādī – Re

Saṃvādī – Dha

(Source: Bhatkhande 1994/1937, II: 162, 164)

Bhairav should be sung at dawn or in the early morning. Its position in the rāg time cycle (samay cakra) means that it rarely gets heard in live performance, unless perhaps at the end of an all-night concert. But the rāg remains alive on recordings and in the early morning practice (riyāz) of musicians. It is regarded as one of the major rāgs of the Hindustani repertory. Its mood is generally serious and devotional (Bhairav is one of the names of Śiva), though romantic compositions in Bhairav can certainly be found. In keeping with the stillness of twilight, its delivery should be relaxed and unhurried, the tone unforced.

The keys to this rāg’s twilight ambience are its śrutis (microtonal tunings) on komal Re and komal Dha—the flattened 2nd and 6th scale degrees. These most salient tones of the rāg (vādī and saṃvādī) are often executed with a slow āndolan (oscillation) which borrows something of the brighter colour of the note above, evoking the hues of dawn. While Re and Dha can be sustained, they rarely stand alone: often decorated by a kaṇ svar (grace note) on Ga or Ni respectively, they will typically want to fall to Sā or Pa respectively; or, if approached from below, to continue in ascent.

Motions such as G–M–D are quite common, and can be a poignant way to approach Pa—as at the start of ‘Dhana dhana murata’, the bandiś heard on Rāg samay cakra (notated below). Ma, also salient, contributes to the rāg’s character and grammar: the antarā of ‘Dhana dhana murata’ sets out from this note and climaxes on it in the higher octave.

Although the jāti of Bhairav is commonly sampūrṇ–sampūrṇ—seven notes both ascending and descending—in another variant, only five notes are used in ascent: Sā, Ga, Ma, Dha and Ni. This form was sometimes favoured by artists of an older generation. Among the recordings of such doyens, Gangubai Hangal’s (1913–2009) rendition of the vilambit (slow) composition ‘Bālamavā more saīyā̃’ (as discussed in Section 4.2) shows how, even in its romantic vein, Bhairav maintains its gravity; after all, early morning is regarded as a time for meditation and prayer.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Dhana dhana murata’

This is a devotional song to Lord Kr̥ṣṇa, characteristically depicted playing his flute. In this recording, the antarā begins with a reference to ‘bansī dhuna’ (‘flute sound’), using the wording of the text taught to VR by his first guru. However, a textual variant ‘bansīdhara’ (‘flute bearer’), is also possible. The former version emphasises the divine sound of Kr̥ṣṇa’s flute, the latter his human figure. Sabaraṅg, invoked at the end, is the pen name (chāp or takhallus) of Ustād Bade Ghulam Ali Khan (1902–68), the probable composer of the song.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Dhana dhana murata Kr̥ṣṇa Murāri, |

Blessed the image of Kr̥ṣṇa Murāri, |

|

sulaksaṇa giridhārī, |

Auspicious the mountain-bearer, |

|

chavi sundara lāge atī pyārī. |

How beauteous his brilliance, most dear to me. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Bansī dhuna [Bansīdhara] manamohana suhāve, |

Lovely is the flute-bearer, enchanter of the mind, |

|

bali bali jāū̃, |

Again and again I devote myself, |

|

more mana bhāve, Sabaraṅga dhyāna vicāre. |

Delightful it is to my mind—thereon dwell the thoughts of Sabaraṅg. |

राग भैरव

स्थाई

धन धन मुरत कृष्ण मुरारि

सुलक्षण गरिधारी

छवि सुन्दर लागे, अति प्यारी।

अंतरा

बंसी धुन [बंसीधर] मनमोहन सुहावे

बली बली जाऊँ

मोरे मन भावे, सबरंग ध्यान विचारे॥

2.5.2 Rāg Toḍī

Performing time second quarter (prahar) of the day.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

||||||||

|

S, |

R G, |

Ḿ P, |

D, |

N Ṡ |

Ṡ N D P, |

Ḿ G, |

R, |

S |

|

Pakaḍ – Ḍ, Ṇ S, R, G, R, S, Ḿ, G, R G, R S

Jāti – Sampūrṇ–sampūrṇ (heptatonic–heptatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Toḍī

Vādī – Dha

Saṃvādī – Ga

(Source: Bhatkhande 1994/1937, II: 429–30)

Toḍī is an important rāg in the Hindustani classical repertoire. It is also known as Miyā̃ kī Toḍī—an attribution to the legendary singer Miyā̃ Tānsen (ca. 1500–89)—although Bhatkhande uses the shorter title. Sung or played in the second phase of the morning, Toḍī draws from the karuṇ ras, which is noted for its qualities of pathos, sadness and compassion. Possessing greater gravity than its close relative Gujarī Toḍī, this rāg expands slowly in an ālāp or baṛā khayāl; in a fast-moving choṭā khayāl like the one presented here the mood can be lighter and more playful.

All the flattened notes—Re, Ga and Dha—should be rendered very flat (ati komal). Pa needs subtle handling: the beauty and significance of this svar should be in inverse proportion to its limited frequency. When Pa does appear, it most usually features in descent, approached by a subtle and carefully timed glide from sustained Dha, probably prefigured by Ni.

In rendering Miyā̃ kī Toḍī, the performer must take care not to create confusion with rāgs based on the same scale, such as Multānī or Gujarī Toḍī. Whereas in Multānī, Dha is only used as a passing note, in Miyā̃ kī Toḍī, this note assumes considerable prominence as the vādī note—often in association with Ni. What most obviously distinguishes Miyā̃ kī Toḍī from Gujarī Toḍī is the presence of Pa; and in Miyā̃ kī Toḍī, Ga rather than Re is prominent. (The prominence of Re and Dha in Gujarī Toḍī gives it similar properties to the evening rāg Mārvā, causing some to refer to the former as ‘subah kā Mārvā’—‘morning Mārvā’.)

Although Bhatkhande theoretically includes Pa in his notation of the ascending scale of Toḍī (see the rāg specification above), in practice, any ascent to this note would not normally continue to Dha, but would rather reverse direction. In an old form of melodic construction, Pa can form part of an upward motion to Dha if immediately quitted by descent—for example, Ḿ–P–D–Ḿ–G—, R–G–R–S.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Laṅgara kā̃karīyā’

This famous Toḍī composition is a staple of the khayāl repertoire, and is a perfect example of the ‘amorous hassling’ song type—to use du Perron’s nomenclature (Magriel and du Perron 2013, I: 137–9). The text might refer to a courting practice in which the boy tries to attract the girl’s attention by throwing small pebbles at her. Or perhaps he is aiming for the pitcher of water she is carrying on her head—a common image in such songs—and she fears the pebbles will bounce off and hurt her. The girl’s anxious reference to her ever-suspicious female in-laws is also typical. The archetypal pair in such stories of amorous teasing is of course Rādhā and Kr̥ṣṇa.

This bandiś is usually rendered as a drut (fast) khayāl, though it might be sung in a not-too slow madhya lay (medium tempo). VR’s performance here focuses on the numerous ways in which the first line of the sthāī and antarā can be varied. This brings up the question of which version, if any, is the definitive form of the melody and which are the variants. The song notation attempts to show a possible ‘normative’ version, but its purpose is, as ever, primarily heuristic.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Laṅgara kā̃karīyā jīna māro, |

Shameless boy! Don’t throw these pebbles at me, |

|

more aṅgavā laga jāve [jāe]. |

They’ll hit my body. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Suna pave morī sāsa nanandīyā. |

My mother-in-law and sister-in-law will hear, |

|

Dorī dorī ghara āve. |

Quickly, come home. |

राग तोडी

स्थाई

लंगर कॉंकरीया जीन मारो

मोरे अंगवा लग जावे [जाए]।

अंतरा

सुन पावे मोरी सास ननंदीया

दोरी दोरी घर आवे॥

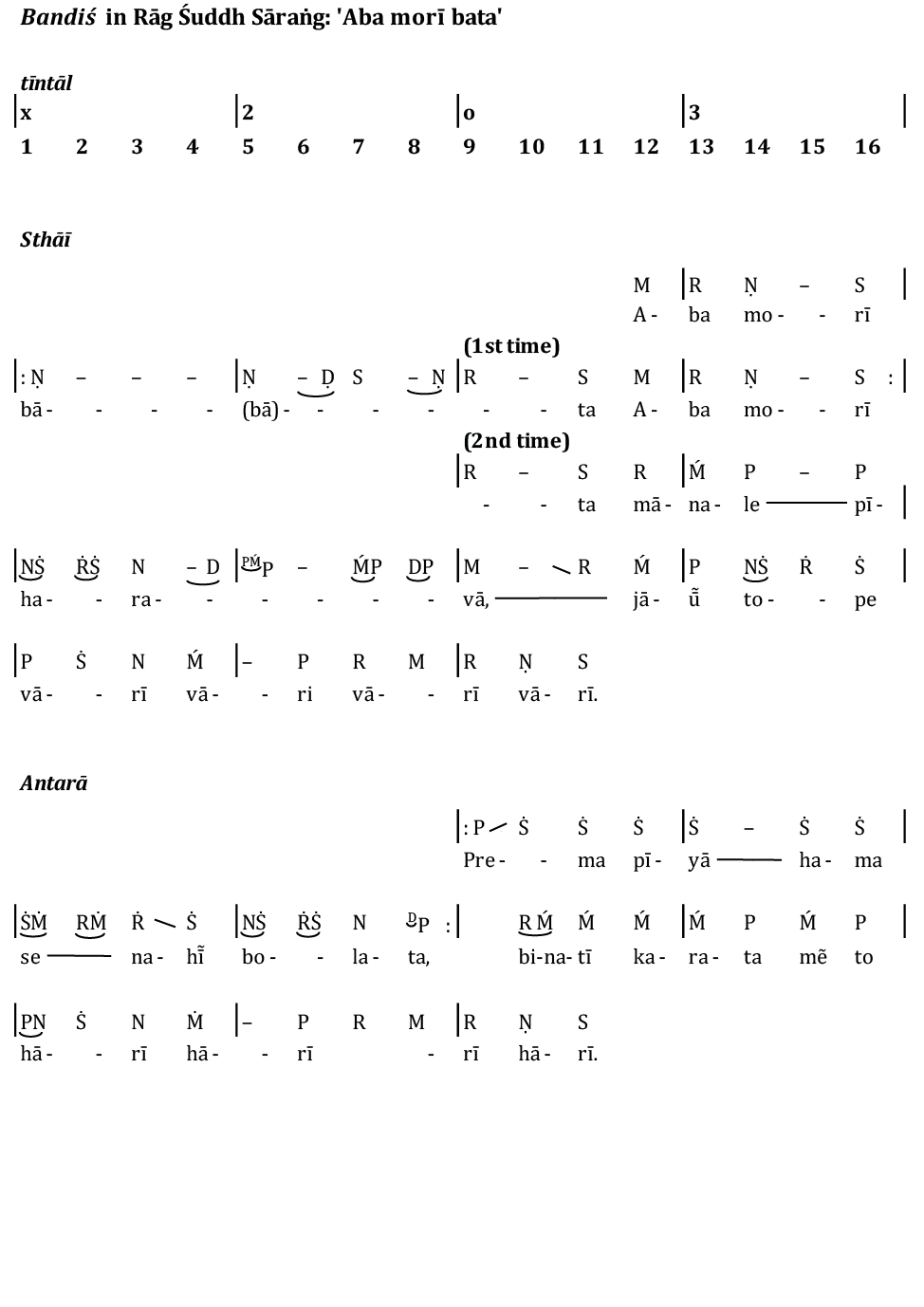

2.5.3 Rāg Śuddh Sāraṅg

Performing time second quarter (prahar) of the day.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

||||||||||||||

|

S |

R |

MR |

R |

Ḿ |

P |

N |

Ṡ |

Ṡ |

N |

DP |

M |

R |

S |

||

Pakaḍ – S, RMR, P, ḾPDḾP, MRSṆ, ṆḌSṆRS

(Source: VR)

Jāti – Auḍav–ṣāḍav (pentatonic–hexatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Kāfī

Vādī – Re

Saṃvādī – Pa

(Source: Bhatkhande 1993/1937, VI: 155)

While Bhatkhande states that Śuddh Sāraṅg may have both forms of Ni and both forms of Ma, many performers employ only śuddh Ni, while indeed using both suddh and tivra Ma. It is this latter version that VR adopts on Rāg samay cakra, and this is reflected in his specification above for the āroh–avroh and pakaḍ.

This melodious rāg is closely related to other rāgs in the Sāraṅg aṅg (group). As in Brindābanī Sāraṅg, śuddh Ma is frequently heard falling to Re; but in Śuddh Sāraṅg this is complemented by tivra Ma which tends towards Pa. Nonetheless, the latter should not be overstated, otherwise the rāg will veer towards its relative, Śyām Kalyāṇ.

Dha needs careful handling. It should not be sustained, but rather woven inconspicuously into melodic figures such as ṆḌSṆ, or NDP, or PḾDP—all of which can be heard in the bandiś sung here. A characteristic melodic pathway (or calan) once Pa is reached, is ḾPN–, NṠ, ṠNDP—DḾPM\R–, RḾPM\R–, MRSṆ, ṆḌSṆRS—.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Aba morī bāta’

This composition may originate from Ustād Fayaz Khan (1886–1950) of the Agra gharānā—as suggested by the inclusion of his pen name, Prem Pīyā, at the start of the antarā. VR learnt it from Prof. Manjusree Tyagi, his one-time mentor.

There are different ways of understanding who is being addressed in the song. In the sthāī (first part) the protagonist implores her beloved, while in the antarā (second part) she speaks to herself or to a companion, expressing her frustration at the lack of a response.

In this recording, VR experiments with varied repetition of the different lines of the bandiś, as well as with the rhythmic placing and decoration of notes. So this is a good example of how a musical realisation may part company from the corresponding notation—or at least from the form of notation used here, which is intended more to communicate the gist of a bandiś than to record its potentially inexhaustible nuances in performance.

What is more structural, however, is the way the metre of the composition cuts liltingly across the 4x4 beat tīntāl structure. For example, the five-beat figure, ‘Aba mori’ that opens the song, can be divided into 2+3 beats; while the fourfold repetition of ‘vārī’, at the end of the sthāī, and ‘hārī’, at the end of the antarā, yields a 3+3+3+2 pattern.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Aba morī bāta mānale pīharavā, |

|

|

jāū̃ tope vārī vārī vārī vārī. |

I sacrifice myself for you, over and over again. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Prema pīyā hama se nahī̃ bolata, |

|

|

binatī karata mẽ to hārī hārī hārī hārī. |

And I am wholly spent, exhausted with entreating. |

राग शुद्ध सारंग

स्थाई

अब मोरी बात मानले पीहरवा

जाऊँ तोपे वारी वारी वारी वारी।

अंतरा

प्रेम पीया हम से नहीं बोलत

बिनती करत में तो हारी हारी हारी हारी॥

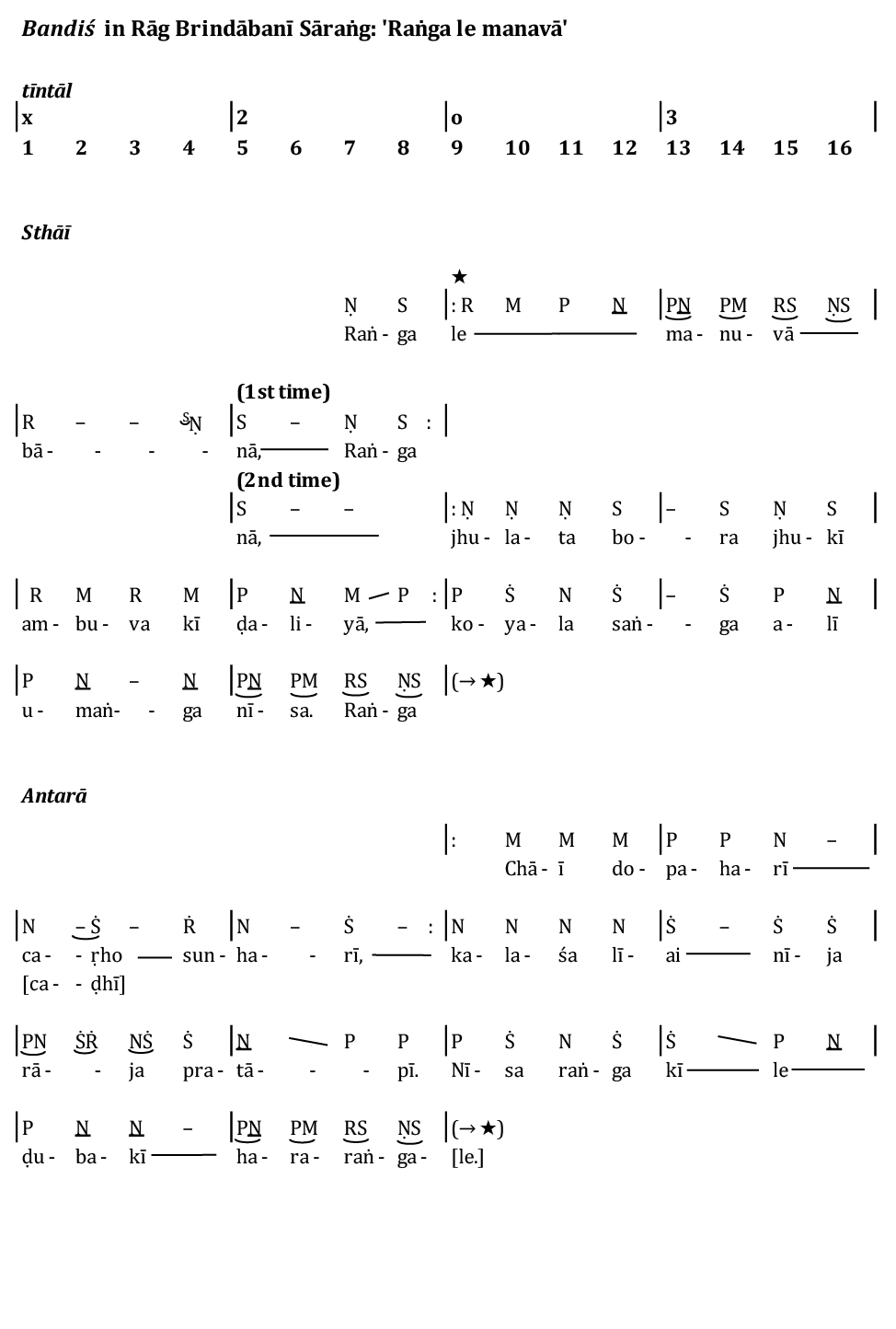

2.5.4 Rāg Brindābanī Sāraṅg

Performing time noontime (madhyan).

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

||||||

|

Ṇ S, |

R, |

MP, |

N Ṡ |

Ṡ NP, |

M R, |

S |

|

Pakaḍ – Ṇ SR, MR, PMR, S

Jāti – Auḍav–auḍav (pentatonic–pentatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Kāfī

Vādī – Re

Saṃvādī – Pa

(Source: Bhatkhande 1995/1937, III: 496)

This rāg is also known as Vṛindābanī Sāraṅg, along with other variants of its name (Bhatkhande, for example, has Bindrābanī Sāraṅg). These all invoke the village of Vrindavan—in the present day, a town in Uttar Pradesh—where the historical Kr̥ṣṇa is said to have spent his childhood.

Brindābanī Sāraṅg is considered by some to be the definitive representative of the Sāraṅg group (aṅg). Among this rāg’s distinguishing features are its pentatonic jāti, which is differently configured in āroh and avroh: the ascending scale begins on suddh Ni, while its descending counterpart incorporates komal Ni.

Perhaps most distinctive of all is Re, the vādī tone, which is very often approached tenderly from above via Ma. This intimate connection is mirrored by a similar affinity between Pa and Ni.

Bhatkhande discusses the relation of Brindābanī Sāraṅg to other members of the Sāraṅg aṅg, in particular Madhma Sāraṅg, distinguished by its more exclusive focus on suddh Ni. By contrast, in Brindābanī Sāraṅg, suddh and komal Ni have equal status. Joep Bor et al. (1999: 52) remind us that Brindābanī Sāraṅg is generally treated as a light rāg, with similarities to Megh (also included in this collection) and Deś.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Raṅga le manavā’

This is a romantic song for the hot noontime and early afternoon, in which the protagonist, sitting under the flowering mango tree, tells joyfully of the colours and beauty of the scene. It is most appropriately rendered in a leisurely madhya lay tīntāl.

Like its Śuddh Sāraṅg forebear, this Brindābanī Sāraṅg bandiś nicely illustrates the possibilities of cross-metrical play between text and tāl. In the sthāī, the opening line, ‘Raṅga le manavā bānā’, comprises 2+4+4+6 beats; while the second line, ‘jhulata bora jhukī’, creates a 3+3+2 beat lilt; and the third line, ‘koyala saṅga alī umaṅga’, creates a 3+3+3+3 beat feel.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Raṅga le manavā bānā, |

Take delight, O my mind, of this lustrous sight, |

|

jhulata bora jhukī ambuvā kī ḍaliyā, |

The blossom swaying on the bending branch of the mango tree, |

|

koyala saṅga alī umaṅga nisa. |

Gladdening the cuckoo and the bee alike. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Chāī dopaharī caṛho [caḍhī] sunharī, |

Noon, that now has spread all around, |

|

kalaśa līai nīja rāja pratāpī. |

Went up with his golden vessel to the glory and brilliance of his own kingdom. |

|

Nisa ranga kī le ḍubakī hararaṅga le. |

Plunge and bathe yourself in the colour and passion of Hari! |

राग ब्रिंदाबनी सारंग

स्थाई

रंग ले मनवा बाना

झुलत बोर झुकी अंबुवा की डलिया

कोयल संग अली उमंग निस।

अंतरा

छाई दोपहरी चढ़ो [वढी] सुनहरी

कलश लीऐ नीज राज प्रतापी

निस रंग की ले डुबकी हररंग ले॥

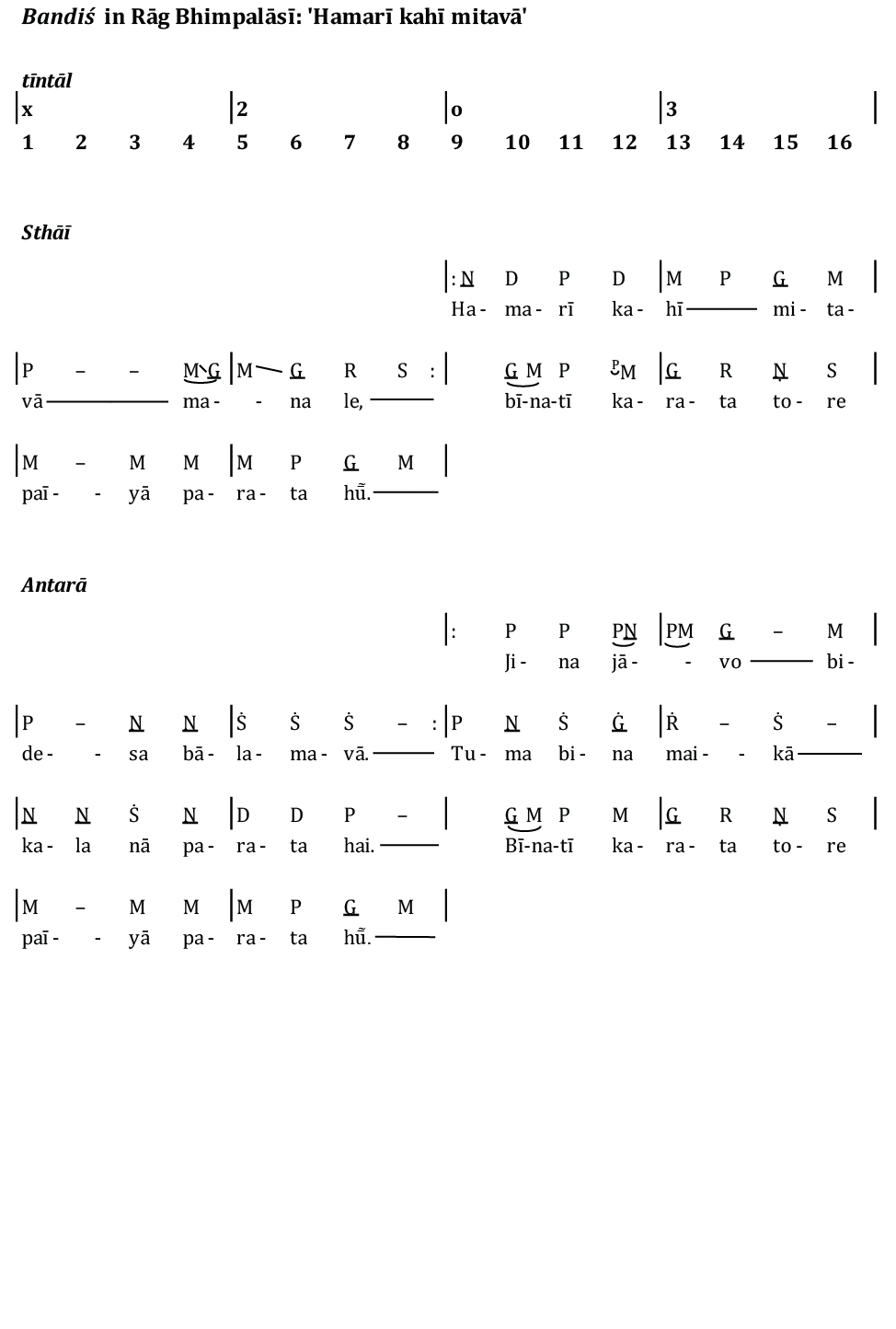

2.5.5 Rāg Bhīmpalāsī

Performing time third quarter (prahar) of the day.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

||||

|

Ṇ S G M, |

P, |

N Ṡ |

Ṡ N D P M, |

G R S |

|

Pakaḍ – N S M, MG, PM, G, MGRS

Jāti – Auḍav–sampūrṇ (pentatonic–heptatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Kāfī

Vādī – Ma

Saṃvādī – Sā

(Source: Bhatkhande 1995/1937, V: 561–2)

While Bhīmpalāsī can be rendered at all tempi—from the slowest baṛa khayāl to the fastest tarānā—its movements are characteristically languid, matching the heat of the early afternoon. Most characteristic is the slow mīṇḍ (glide) from Ma to Ga. Ni especially contributes to this rāg’s association with the karuṇ ras—with its aesthetic of poignancy, compassion and sadness.

As vādī, Ma is officially one of the most prominent notes in this rāg. Pa is also important even though it should not be overly sustained, which would risk confusion with Rāg Dhanāśrī. Among Bhīmpalāsī’s rarely mentioned subtleties is the possibility that komal Ni be inflected very slightly sharper when approached from above and very slightly flatter when approached from below. In avroh, Ni may move to Dha via a kaṇ svar (grace note) on Pa—as in ṠNPDP. Similarly, in the lower tetrachord, Ga may move to Re via a kaṇ svar on Sā—as in M\GSRS.

Similar rāgs with which Bhīmpalāsī should not be confused include Dhānī (same scale but with no Re or Dha), Patdīp (similar flavour but with suddh Ni), and Bāgeśrī (same scale but SGMDNṠ in āroh, greater prominence of Dha, and only occasional, specialised use of Pa).

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Hamarī kahī mitavā’

This song is a composition by Pandit Vinaychandra Modgal (1918–95), who was Principal of the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, New Delhi at the time VR studied there. The song bears the pathos of the karuṇ ras: the protagonist implores her lover not to leave her side. In the antarā, the image of the beloved in a far-away place is another common trope of khayāl songs.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Hamarī kahī mitavā māna le, |

Consider well my words, dear friend, |

|

bīnatī karata tore paīyā parata hū̃. |

In humble submission I fall at your feet. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Jina jāvo bidesa bālamavā. |

|

|

Tuma bina maikā kala nā parata hai. |

Without you, there is no peace for me. |

|

Binatī karata tore paīyā parata hū̃. |

In humble submission I fall at your feet. |

राग भीमपलासी

स्थाई

हमरी कही मितवा मान ले

बिनती करत तोरे पईया परत हूँ।

अंतरा

जिन जावो बिदेस बालमवा

तुम बिन मैका कल ना परत है

बिनती करत तोरे पईया परत हूँ॥

2.5.6 Rāg Multānī

Performing time fourth quarter (prahar) of the day.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

|

|

Ṇ S, G Ḿ P, N Ṡ |

Ṡ N D P, Ḿ G, R S |

Pakaḍ – Ṇ S, Ḿ G, P G, R S

Jāti – Auḍav–sampūrṇ (pentatonic–heptatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Toḍī

Vādī – Pa

Saṃvādī – Sā

(Source: Bhatkhande 1991/1937, IV: 171–2)

Bhatkhande suggests that Multānī occupies a transitional place within the diurnal cycle of rāgs. It is a parmel-praveśak rāg, meaning that it introduces a new ṭhāṭ (group of rāgs). Leading us away from the Kāfī ṭhāṭ—which includes rāgs such as Bhīmpalāsī with flat Ga and Ni—Multānī looks towards the Pūrvī ṭhāṭ—in which rāgs such as Pūriyā Dhanāśrī take flattened Re and Dha, and sharpened Ma. Multānī itself, belonging to the Toḍī ṭhāṭ, sits between those other ṭhāṭs and mediates their different qualities. With flattened Ga and Dha, and sharpened Ma, it has properties of both a late afternoon and a twilight (sāndhi prakaś) rāg. These points, then, provide support for theories of rāg performing-time (samay) based on scale construction; indeed they are cited by Nazir Jairazbhoy (1971: 63–4) in his own development of Bhatkhande’s time theory.

While Multānī shares a scale with Rāg Toḍī, it has a different grammar, which foregrounds Sā, Pa and Ni, and uses Re and Dha only discreetly. In descending patterns, Re is commonly approached elliptically from below via a kaṇ svar (grace note) on Sā. And Ga often bears the shadow of tivra Ma—hence ḾG is a common figure. These various properties might typically be joined together in a phrase such as P–DPḾPḾ\GSRṆS–, which encapsulates Multānī’s melodious, flowing character. Its mood is romantic compared with the pathos of Toḍī; but this does not diminish its status as an important rāg in the khayāl repertory.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Runaka jhunaka’

While technically a drut khayāl, this bandiś is best sung not too quickly. The scene depicted appears in a number of khayāl compositions (see, for example, Pūriyā Dhanāśrī (Section 2.5.7) in this collection). The female protagonist, discreetly approaching the bed of her loved one, fears that the tinkling of the bells on her anklet and belt might give the game away to her mother- and sister-in-law; perhaps this is as much a topic for the sultry heat of the deep afternoon as it is for the quiet of the night.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Runaka jhunaka morī pāyala bāje, |

My anklets jingle-jangled, |

|

bichuā chuma chuma chananana sāje. |

Chum chananana went my toe rings. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Saija caṛhata morī jhāñjhara hālī, |

I mounted the bed, my anklets shook and trembled, |

|

sāsa nananda kī lāja. |

My mother-in-law and sister-in-law close by, I felt coy. |

राग मुलतानी

स्थाई

रुनक झुनक मोरी पायल बाजे

बिछुआ छुम छुम छननन साजे।

अंतरा

सैज चढ़त मोरि झांझर हाली

सास ननंद की लाज॥

2.5.7 Rāg Pūriyā Dhanāśrī

Performing time evening twilight (sandhyākāl).

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

|||||||

|

Ṇ R |

GḾP, |

DP, |

NṠ |

Ṙ NDP, |

ḾG, |

Ḿ R G, |

RS |

|

Pakaḍ: – ṆRG, ḾP, DP, Ḿ G, Ḿ RG, D ḾG, RS

Jāti – Auḍav–sampūrṇ (pentatonic–heptatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Purvī

Vādī – Pa

Saṃvādī – Re

(Source: Bhatkhande 1991/1937, IV: 341–2)

Pūriyā Dhanāśrī is an early evening rāg, which Bhatkhande indicates should be sung at the time known as sandhyākāl: the transition between day and night; a time when lamps are lit and prayers are said. VR recounts how his one-time teacher, Pandit M.G. Deshpande similarly numbered Pūriyā Dhanāśrī among the sandhi prakaś (twilight) rāgs. Prakash Vishwanath Ringe and Vishwajeet Vishwanath Ringe (n.d.: https://www.tanarang.com/english/puriya-dhanashri_eng.htm) assign it to the fourth quarter (prahar) of the day.

A related rāg is Pūrvī. But Bhatkhande reminds us that while Pūrvī admits both forms of Ma, Puriyā Dhanāśrī has only tivra Ma. The latter rāg’s characteristic figure PḾGḾRG links this svar to the vādī and saṃvādī notes Pa and Re. Further characteristic movements are GḾDNṠ and ṘNDP.

The status of Pa as vadī is confirmed by its obvious prominence in performance—for instance, this pitch initiates both the first and second lines of the bandiś ‘Pā̃yalīyā jhanakāra’, sung here. But Bhatkhande’s identification of Re as saṃvādī is more ambiguous, given that this note is never dwelled on. It is likely that his choice here is theoretically driven, since vadī and saṃvādī should be four or five notes apart. Conversely, Ringe and Ringe cite Sā as saṃvādī. Either way, these tones further distinguish Pūriyā Dhanāśrī from Pūrvī, where Ga and Ni are the vadī and saṃvādī.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Pā̃yalīyā jhanakāra’

This famous song depicts a canonical scene of Braj Bhāṣā poetry: a young woman who fears that the jingling of her ankle bells will wake her mother- and sister-in-law as she steals away to her lover in the night. As with all good bandiśes, this one eloquently captures the key melodic features of the rāg (as described above), offering a good guide to its rūp or structure. VR’s rendition here illustrates the many ways in which the opening lines of the sthāī and antarā can be varied in performance.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Pā̃yalīyā jhanakāra morī, |

My ankle bells are ringing, |

|

jhanana jhanana bāje jhanakārī. |

Jingle-jangle, jingle-jangle, they ring. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Pīyā samajhāū̃ samajhata nāhī̃, |

|

|

sāsa nananda morī degī gārī. |

My mother-in-law and sister-in-law will scold me. |

राग पूरिया धनाश्री

स्थाई

पाँयलीया झनकार मोरी

झनन झनन बाजे झनकारी।

अंतरा

पीया समझाऊँ समझत नाहीं

सास ननंद मोरी देगी गारी।।

2.5.8 Rāg Bhūpālī

Performing time first quarter (prahar) of the night.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

|||||||||||

|

S |

R |

G |

P, |

D, |

Ṡ |

Ṡ, |

D |

P, |

G, |

R, |

S |

|

Pakaḍ – S, R, S Ḍ, S R G, P G, D P G, R, S

Jāti – Auḍav–auḍav (pentatonic–pentatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Kalyāṇ

Vādī – Ga

Saṃvādī – Dha

(Source: Bhatkhande 1995/1937, III: 23)

Bhūpālī is found across a range of musical idioms—from folk music and light classical genres such as ṭhumrī, through khayāl (as here), to more heavyweight styles such as dhamār and dhrupad. So, although this seemingly simple pentatonic rāg is well suited to beginners, it can also be rendered expansively and with gravity by experienced performers.

While Ga and Dha are the vādī and saṃvādī notes, Sā and Pa may also be sustained. Re can sometimes be savoured on its way to other notes, but should not be overly dwelled on.

Bhūpālī is associated with the śānt ras (Sanskrit: śāntam rasa) and its feelings of peace and tranquillity. Related rāgs include Deśkār, a morning rāg with the same āroh and avroh but with Dha rather than Ga as the vādī note, and greater emphasis on the upper tetrachord.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Gāīye Gaṇapatī’

The text of this bandiś is by the devotional poet and Hindu saint, Goswami Tulsidas. Commentators variously give his birth date as 1497, 1511, 1532 and 1554; most agree he died in or around 1623. The words of ‘Gāīye Gaṇapatī’ come from the beginning of his poem Vinay-Patrikā (‘Letter of Petition’), and are part of a hymn to the elephant-headed god, Gaṇeś (Ganesh).

The language here is in a different poetic vein from the other songs in Rāgs Around the Clock. Tulsidas wrote primarily in the Avadhī and Braj languages—eastern and western dialects of Hindi respectively. The version of the song text given below is partly based on a Hindi edition of the Vinay-Patrikā edited by Hanuman Prasad Pohar (Tulsidas 2015).

VR was taught this bandiś by Pandit M.G. Deshpande while his student at the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, New Delhi. Numerous other versions of it can readily be found online. The text may also be heard sung to different melodies in other rāgs, such as Mārvā, Hansadhvanī and Yaman, often in the lighter style of a bhajan.

(Translation adapted by DC from a word-to-word translation in Rasikas 2008.)

राग भूपाली

स्थाई

गाईये गणपती जग वंदना।

शंकर सुमन [सुवन] भवानी नंदन ॥

अंतरा

सिद्धी सदन, गज वदन, विनायक।

कृपा सिन्धु, सुन्दर, सव दायक [लायक]॥

2.5.9 Rāg Yaman

Performing time first quarter (prahar) of the night.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

||||||||||||||

|

Ṇ |

R |

G |

Ḿ |

D |

N |

Ṡ |

Ṡ |

N |

D |

P |

Ḿ |

G |

R |

S |

|

Pakaḍ – ṆRG; PḾGRS

Jāti – Ṣāḍav–sampūrṇ (hexatonic–heptatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Kalyāṇ

Vādī – Ga

Saṃvādī – Ni

(Source: VR)

Rāg Yaman exists in more than one version. The commonly adopted form passed down to VR, and thence to his students, has a jāti that omits Sā and Pa in ascent—as shown in the specification above. Even though this ascending form eventually leads to upper Sā, making a hexatonic rising scale, the common association within Yaman of figures such as ṆRG and GḾDN adds subtle pentatonic (auḍav) hues to its overall ṣāḍav–sampūrṇ (hexatonic–heptatonic) jāti. By contrast, Bhatkhande describes a different incarnation, whose jāti he notes as, simply, ‘sampūrṇ’ (heptatonic): he gives the āroh–avroh as SRG, ḾP, D, NṠ | ṠND, P, ḾG, RS; and the pakaḍ as ṆRGR, S, PḾG, R, S (Bhatkhande 1994/1937, II: 17, 18).

The mood of Yaman is typically calm and romantic, capturing the peacefulness of the time immediately after sunset. The emphasis on Ga and Ni does much to create this mood. Re and Pa are also prominent, and contribute to the rāg’s beauty. Indeed, all notes in Yaman are to some degree able to be sustained: while Ḿa and Dha are relatively less prominent, they are more than fleetingly touched upon, contributing significantly to the rāg’s colouration.

Although musicians commonly learn Yaman early in their studies, this in no way detracts from its importance in the repertory. It was much loved by Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, who performed it up to the very end of his musical life. As well as being a staple of the Hindustani classical canon, Yaman is also found in light classical and film music.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Śyām bajāi’

This joyful composition depicts Lord Kr̥ṣṇa (Śyām) playing his flute, the whole world intently listening. The lyricist would appear to be Manaraṅg (Mahawat Khan of Jaipur, according to Bonnie Wade (1997: 20)), who names himself in a play on words in the text. This bandiś was popularised by Bhimsen Joshi, who taught it to VR and numerous other disciples.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Śyām bajāi āja muraliyā̃, |

Today Śyām [Kr̥ṣṇa] plays upon his flute, |

|

ve apano [apane] adharana gunī so. |

On his lips, like a musician. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Jogī jaṅgama jatī satī aura gunī munī, |

Yogīs, ascetics and saints and good women, |

|

saba nara nārī mil. |

All men and women come together. |

|

Moha liyo hai Manaraṅga [man raṅga] ke. |

He has enchanted Manaraṅg [their minds with passion]. |

राग यमन

स्थाई

श्याम बजाइ आज मुरलियाँ

वे अपनो [अपने] अधरन गुनी सो।

अंतरा

जोगी जंगम जती सती और गुनी मुनी

सब नर नारी मिल

मोह लियो है मनरंग [मन रंग] के॥

2.5.10 Rāg Kedār

Performing time first quarter (prahar) of the night.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

||||||||||

|

S M, |

M P, |

D P, |

N D, |

Ṡ |

Ṡ, |

N D, |

P, |

Ḿ P D P, |

M, |

G M R S |

|

Pakaḍ – S, M, M P, D P M, P M, R S

Jāti – Auḍav–sampūrṇ (pentatonic–heptatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Kalyāṇ

Vādī – Ma

Saṃvādī – Sā

(Source: Bhatkhande 1995/1937, III: 118)

The warmth of this śr̥ṅgār ras (romantic-aesthetic) rāg comes in part from its sensitivity to śuddh Ma. Its sensuous entreaties are captured by oblique (vakra) motions such as MG-PḾ-DP—as at the opening of the bandiś ‘Bola bola mose’, sung here. Such indirect patterns crucially distinguish Kedār from Bihāg, which likewise has both forms of Ma. While in Bihāg, Ga is prominent (the vādī tone), in Kedār, it is Ma that is the vādī, and Ga is typically subsumed into it—within figures such as M\GP.

These are just some of the subtleties which the performer needs to master in this melodically complex rāg. Others include the treatment of Re—absent entirely in āroh, and typically prefaced by a kaṇ svar (grace note) on Sā in the elliptical descent from Ma—i.e. M–SRS. Handled carefully, komal Ni is also very occasionally permitted as a vivādī (foreign) note. Rāgs that feature similar melodic movements to Kedār include Hamīr and Kamod.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Bola bola mose’

Here is a classic devotional song to Lord Kr̥ṣṇa, addressed—in one of his many alternative appellations—as ‘son of Nand’. The setting is his home village of Brij, whose denizens are depicted as ever hungry for their god. Although this bandiś is in drut lay, the pace should be sufficiently measured to bring out the feelings of entreaty and devotion. VR learnt this song from his former teacher Pandit Vinay Chandra Maudgalya.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Bola bola mose Nanda kũvaravā, |

Talk, talk to me, O son of Nand, |

|

rasa bharī batiyā̃ lāge madhura torī. |

So sweet to me is your talk, so full of feeling. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Subhaga hātha tore bansī Śyāma sī, |

The flute in your graceful hands, |

|

brijavāsī nīrakhata naina bharī, |

The people of Braj gaze upon it and fill their eyes, |

|

nahī̃ aghāta jaise bhūkha bhikhārī. |

Like mendicants ever hungry for more. |

राग केदार

स्थाई

बोल बोल मोसे नंद कुंवरवा

रस भरी बतियाँ लागे मधुर तोरी।

अंतरा

सुभग हाथ तोरे बंसी श्याम सी

बृजवासी नीरखत नैन भरी

नहीं अघात जैसे भूख भिखारी॥

2.5.11 Rāg Bihāg

Performing time second quarter (prahar) of the night.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

||||||

|

S G, |

M P, |

N Ṡ |

Ṡ, |

N D P, |

M G, |

R S |

|

Pakaḍ – Ṇ S, G M P, G M G, R S

Jāti – Auḍav–sampūrṇ (pentatonic–heptatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Kalyāṇ/Bilāval

Vādī – Ga

Saṃvādī – Ni

(Source: Bhatkhande 1995/1937, III: 181–2)

Bihāg is an example of a rāg whose identity has changed within recent memory. This mutation turns around the subtly increasing status of tivra Ma (the sharpened fourth degree), which in Bihāg co-exists with the always more prominent suddh Ma (natural fourth). At one time, tivra Ma was expressed only fleetingly—perhaps touched on within a descending mīndh (gliding motion) between Pa and Ga. Subsequently, tivra Ma has become more salient with some performers, though it is still heard only in avroh between Pa and Ga or in patterns such as PḾP. Sung with the right kind of inflection, this can bring out the romantic character of the rāg. In the later-twentieth century VR was taught the earlier style of the rāg by his then guru, Pandit M. G. Deshpande, though he himself now gives greater prominence to tivra Ma (as we hear in Rāg samay cakra).

The ambiguity around the status of tivra Ma is reflected in Bihāg’s place in the ṭhāṭ system. Ringe and Ringe (n.d.: http://www.tanarang.com/english/bihag_eng.htm), and Patrick Moutal (1997/1991: 101) classify it under the Kalyāṇ ṭhāṭ, which has a sharpened fourth. Conversely, Bhatkhande, writing in the earlier twentieth century, places it in the Bilāval ṭhāṭ (the natural-note scale), classifying tivra Ma as vivādī—a note outside the rāg yet available as an occasional nuance. He also cautions against overstressing Re and Dha, so as to avoid confusion with Rāg Bilāval itself.

As ever, knowledge of related rāgs is important: here the comparators include Kedār, Kāmod and Hamīr. The motion SMG, for example, while allowable in Bihāg (as at the word ‘tarapa’ in the bandiś performed here), should not be over-emphasised, as this figure is more characteristic of Kedār. Meanwhile, Māru Bihāg complements its sibling rāg by reversing the dominance of tivra Ma and suddh Ma (placing the former in the ascendant), and by according much greater prominence to Dha and Re which only have a passing function in Bihāg itself.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Abahũ lālana’

This is another classic song of longing for an absent lover. In the antarā, the natural world and inner world come together in the images of rain clouds and the welling up of tears, of lightning and the trembling heart.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Abahũ lālana maikā yuga bīta gāe, |

Already now, my love, so many eons have passed for me, |

|

tumhāre darasa ko tarapa tarapa jīyarā tarase re. |

My heart is tormented, longing endlessly to see you. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Umaṅgẽ nainā bādarī sī jhara lāge, |

My welling eyes rain forth like clouds, |

|

jīyarā tarase [larajai], |

My heart trembles, |

|

dāminī sī kaundha caundha, |

It is as if lightning had dazzled me, |

|

maiharvā barase. |

The cloud showers forth rain. |

राग बिहाग

स्थाई

अबहुं लालन मैका युग बीत गए

तुम्हारे दरस को तरप तरप जीयरा तरसे रे।

अंतरा

उमंगें नैना बादरी सी झर लागे

जीयरा तरसे [लरजै]

दामिनी सी कौंध चौध

मैहरवा बरसे॥

2.5.12 Rāg Mālkauns

Performing time third quarter (prahar) of the night.

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

|||||||

|

Ṇ S, |

G M, |

D, |

N Ṡ |

Ṡ N D, |

M, |

G, |

G M G S |

|

Pakaḍ – MG, MDND, M, G, S

Jāti – Auḍav–auḍav (pentatonic–pentatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Bhairavī

Vādī – Ma

Saṃvādī – Sā

(Source: Bhatkhande 1995/1937, III: 700–1)

Performed in the depths of the night, Mālkauns likewise inhabits the depths of the imagination and cultural memory. Daniel Neuman (1990: 64–6) recounts stories from hereditary Muslim musicians who feared to sing this rāg alone after midnight because it might summon up capricious spirits known as jinns. Mālkauns is regarded as a masculine rāg belonging to the vīr ras, with its connotations of heroism and war; the mood is one of gravity. Unhurried presentation and pervasive use of very slow mīṇḍ (gliding motion) are essential to capturing its character.

Omkarnath Thakur (2005: 227) tells us that Mālkauns is a dialect form of the name ‘Mālvakausik’, and that its correct prakriti (mode of delivery) is śānt (peaceful) and gambhīr (serious). Thakur describes the formal features of Mālkauns using more traditional terminology than does his rival, Bhatkhande. In Thakur’s account, Ma has the status of nyās svar—a standing or sustained note; Sā and Ni have the status of grah svar (notes used to initiate a phrase) in ālāp and in tāns respectively; and Ga and Dha are anugāmī svar (passing notes). Thakur also draws attention to the significance in this rāg of samvad svar—notes paired in fourths: Sā–Ma, Ga–Dha, Ma–Ni.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Koyalīyā bole ambuvā’

This cheerful song makes the point that a rāg can encompass a spectrum of moods, and that a choṭā khayāl in particular can show facets of the rāg other than the dominant one. In this romantic bandiś full of natural imagery, the Kokila (Asian Koel) bird—which has similar poetic connotations to the nightingale in western culture—sings from the mango tree, heralding spring (for more on the place of birds in Braj Bhāṣā poetry and Hindustani bandiśes, see Magriel and du Perron 2013, I: 146–53). In the antarā, the image of the bee playing among the buds could be an allusion to Kr̥ṣṇa among the cowherds.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Koyalīyā bole ambuvā ḍāra para, |

The sweet Kokila bird gives voice on the branch of the mango tree, |

|

r̥tu basanta ko deta sandesavā. |

And so heralds for us the arrival of Spring. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Nava kaliyana para gunjata bhãvarā, |

On the new buds the bee buzzes, |

|

una ke saṅga karata raṅgaraliyā̃, |

In their company he plays his games, |

|

yahī basanta ko deta sandesavā. |

This is what heralds the Spring. |

राग मालकौंस

स्थाई

कोयलीया बोले अंबुवा डार पर

ऋतु बसंत को देत संदेसवा।

अंतरा

नव कलियन पर गुंजत भँवरा

उन के संग करत रंगरलियाँ

यही बसंत को देत संदेसवा॥

2.5.13 Rāg Megh

Performing time rainy season (varṣa r̥tu).

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

|||||||||||

|

S |

R |

M |

P |

N |

Ṡ |

Ṡ |

N |

P |

M |

R |

S |

|

Pakaḍ – SMRP— , PN–P, ṠPNPM\R S

Jāti – Auḍav–auḍav (pentatonic-pentatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Kāfī

Vādī – Sā

Saṃvādī – Pa

(Source: VR; Bhatkhande 1991/1937, VI: 242–3)

For all that the rainy season is regarded as a time of romance, this monsoon rāg is quintessentially weighty and serious—an old and revered gambhīr rāg. Megh draws its gravity from its place in the Malhār group of rāgs; indeed it is often known as Megh Malhār or Megh Mallār. It evokes dark storm clouds, the rumbling of thunder, and dramatic lightning flashes. Ringe and Ringe (n.d.: http://www.tanarang.com/english/megh_eng.htm) associate it with the heroic and masculine vīr ras.

All this distinguishes Megh from similar but lighter (cancal) rāgs of the Sāraṅg group—such as Bṛindābanī Sāraṅg and, especially, Madhmād Sāraṅg. The latter superficially resembles Megh through its use of the same scale and similar melodic figures. But Megh plumbs greater depths through its application of slow and heavy mīṇḍ (glides) and its more ponderous treatment of svar and ornaments. Re is often dwelled on, and is nearly always approached via Ma, which, conversely, is often treated as a kaṇ svar (grace note). The use of āndolan (oscillation) between these two notes is another point of difference from Madhmād Sāraṅg; and the figure M\R–P, drawn from Rāg Malhār, is similarly distinctive. (For further details see Moutal 1991: 121–2.)

As with many rāgs, it would be unwise to try and pin down too definitive a form of Megh. The specification and description above reflect a synthesis of Bhatkhande’s and VR’s slightly different understandings. VR makes a pragmatic distinction between Megh itself and Megh Malhār, the latter being distinguished by the subtle inclusion of komal Ga; but he admits that it remains moot whether these constitute entirely different rāgs. Bhatkhande discusses only Megh Mallār (Megh Malhār) in his Kramik pustak mālikā, mentioning that this can sometimes include the note Dha. Walter Kaufmann outlines three possible variants of Megh Mallār (1993/1968: 395–401). Similar ambiguity surrounds the identification of vādī and saṃvādī tones. Following Bhatkhande, we here give Sā and Pa, while Ringe and Ringe (ibid.), Moutal (1991: 122) and Kaufmann (ibid.: 397) all have Ma and Sā.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

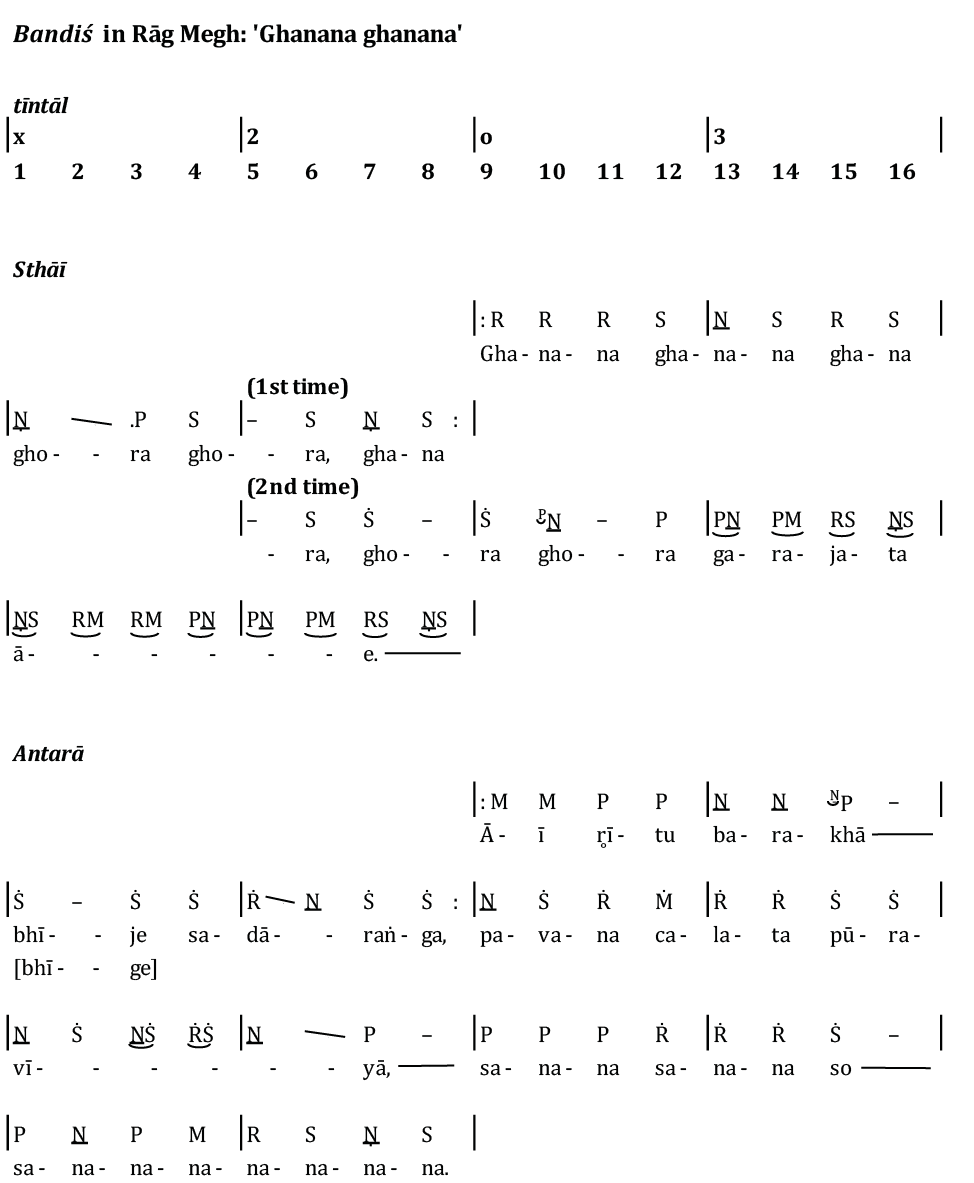

Bandiś: ‘Ghanana ghanana’

This bandiś evokes the might of an approaching thunderstorm, not only through the meaning of the words (ghor—frightful, rumbling; garajnā—to thunder, to roar), but also through their sounds; onomatopoeia and cumulative repetition serve both a textual and a musical purpose. These devices are brought out by gamak (heavy shakes) and ākār tāns.

In the antarā the lyricist identifies himself with the pen name (chāp) Sadāraṅg—the early eighteenth-century musician, Ni‘mat Khan—which may or may not be an authentic attribution. He implies he is drenched not just by the rain but also by love.

VR learnt this composition from his guide and teacher Manjusree Tyagi, and further draws inspiration from historic recorded performances of the rāg by Ustād Amir Khan (1912–74).

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Ghanana ghanana ghana ghora ghora, |

Awesome rumbling, cloud on cloud, |

|

ghora ghora garajata āe. |

Frightful roaring thunder looms. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Āī r̥ītu barakhā bhīje [bhīge] Sadāraṅga, |

The rainy season has come and Sadārang is drenched, |

|

pavana calata pūravīyā, |

The East wind blows, |

|

sanana sanana so sananananananana. |

Singing, whistling, thrilling, all the while. |

राग मेघ

स्थाई

घनन घनन घन घोर घोर

घोर घोर गरजत आए।

अंतरा

आई ऋीतु बरखा भीजे [भीगे] सदारंग

पवन चलत पूर्वीया

सनन सनन सो सननननननन॥

2.5.14 Rāg Basant

Performing time springtime (Basant) or final quarter of the night (rātri kā antim prahar).

|

Āroh (ascending) |

Avroh (descending) |

|||||||||

|

S G, |

ḾD, |

Ṙ, |

Ṡ |

Ṙ N D, |

P, |

ḾG, |

ḾG, |

ḾDḾG, |

RS |

|

Pakaḍ – ḾD, Ṙ, Ṡ, Ṙ NDP, ḾG, ḾG

Jāti – Auḍav–sampūrṇ (pentatonic–heptatonic)

Ṭhāṭ – Pūrvī

Vādī – Tār Sā

Saṃvādī – Pa

(Source: Bhatkhande 1991/1937, IV: 371–2)

Basant, which means ‘spring’, is a seasonal (mausam) rāg. On the Indian subcontinent, springtime extends from around early February—the time of the Sarasvatī pūjā—to around mid-to-late March—the festival of Holī. During this period, Rāg Basant may be performed at any time. Otherwise, it may be heard in the last phase of the night, which has similarly romantic connotations.

Basant is an uttaraṅg pradhan rāg: it emphasises the upper tetrachord of the scale. Hence tār Sā, the upper tonic, is the principal note (or vādī). Like Rāg Purvī, Basant uses both versions of Ma, though tivra Ma predominates. Śuddh Ma appears in the characteristic figure S–M–Ḿ–M–G, which draws from the grammar of Rāg Lalit—one of the few rāgs to permit two versions of the same note consecutively. While the Lalit aṅg (limb) is not compulsory in Basant, its effect can be beautiful if used sparingly; it is typically followed by the figure ḾGN–D–P.

A related rāg is Paraj. Bor et al. (1999: 30) mention that some musicians do not even distinguish between the two rāgs; but Paraj has its own characteristic melodic figures, such as Ṡ–Ṙ–S–Ṙ–N–D–N and G–M–G; and unlike Basant it incorporates Pa in ascent. Moreover Paraj is a cancal (light, flowing) rāg, while Basant would be classified as a more serious, gambhīr rāg—notwithstanding the lively choṭā khayāl sung here.

|

Performance by Vijay Rajput |

|

Spoken version of bandiś text |

Bandiś: ‘Phulavā binata’

This ektāl composition can be sung in madhya lay (medium tempo) but is most effective in drut lay (fast tempo). The notation of the final line of the antarā simplifies the tān sung by VR in the last six beats on the recorded version. The poem can be read as a conversation between two onlookers, who address each other with the endearing term ‘rī’. They admire a daughter of the village of Gokul, which we can presume to be Rādhā, the consort of Lord Kr̥ṣṇa (in the antarā, Kr̥ṣṇa is identified with the name Nandalāl). The girl’s beauty parallels that of the natural world: her face is like the moon, she has eyes like lotus flowers, and is radiant like the sun. This imagery perfectly captures the romantic feel of springtime and the rāg that bears its name.

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Phulavā binata ḍāra ḍāra, |

She picks blossoms from every branch, |

|

Gokula kī sukumārī, |

She the beauteous one of [the village of] Gokul, |

|

candr̥badana kamalanainī, |

Moon-faced, lotus-eyed, |

|

bhānu kī laṛiyai rī [laḍīrī]. |

The daughter of the sun, O my dear one! |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Ai rī eka sukumārī, |

And while she, that beauteous one, |

|

calata nā añcala savārī, |

Walks along and takes little care to veil herself, |

|

āvenge nandalāla. |

The son of Nand [Kr̥ṣṇa] will come. |

|

Dekha ke ḍarīyai rī. |

Seeing him she will feel afraid. |

राग बसंत

स्थाई

फुलवा बिनत डार डार

गोकुल की सुकुमारी

चंदृबदन कमलनैनी

भानु की लड़ियै री [लडीरी]।

अंतरा

ऐ री एक सुकुमारी

चलत ना अंचल सवारी

आवेंगे नंदलाल

देख के डरीयै री॥