3. EXPLORATIONS AND ANALYSES (I):

RĀG SAMAY CAKRA

©2024 David Clarke, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0313.03

3.1 Introduction

In the next two parts of Rāgs Around the Clock, I (David Clarke, henceforth DC) undertake a close reading of Vijay Rajput’s (henceforth, VR) performances on the book’s associated albums: Rāg samay cakra (here, in Part 3) and Twilight Rāgs from North India (in Part 4). While it would have been possible to organise these studies as track-by-track analyses of the albums, I have opted for a different strategy. Sections 3.2 and 3.3 consider in turn the two performance stages on which every track of Rāg samay cakra is based: ālāp and choṭā khayāl. The analyses pull out extracts from across the entire album in order to illustrate the different facets of these two stages (and in so doing also provide commentary on all of the fourteen rāgs sung). Following this, Part 4 includes a similarly extended account of the baṛā khayāl in Rāg Yaman from Twilight Rāgs. Hence, across the two parts, all of the three principal stages of a khayāl performance are investigated. (Other contents of Part 4 are discussed in its own introduction, Section 4.1.)

While these essays are longer reads than the earlier writings in this book, and have a stronger theoretical orientation, I have couched the material in ways that I hope will be accessible to students and lay listeners, as well as being of interest to researchers and professional musicians (I should add that it is not compulsory to read every part of every essay; each section is designed to be, to some extent, freestanding and informative in its own right). Importantly, these inquiries continue to include a pedagogical dimension. A key heuristic strategy is to place the reader in the position of the performer, and ask: what do I need to know in order to sing (and hence also to understand) an ālāp, or a choṭā khayāl, or—in Part 4—a baṛā khayāl?

In asking such questions, I also seek to pull out general truths from the specifics of VR’s performances, and speculate on some of the bigger questions raised by khayāl and Hindustani classical music more widely. The answers are often formulated as rubrics that codify the knowledge which musicians and listeners acquire over a long period—musicians in order to perform, listeners in order to become appreciative audience members (rasikas) with whom artists can subtly and co-creatively interact in the live event. Ultimately this inquiry leads to the question (also addressed in the book’s Epilogue) of what kind of knowledge is constituted by such rubrics, and how this relates to the intrinsically musical knowledge that is passed down through successive generations of performers—more bluntly, the perennial question of the relationship between theory and practice.

3.2 How Do You Sing an Ālāp?

Preamble

Ālāp is a fundamental principle of Indian classical music. It is the quintessential means through which a performer brings rāg into being: as musicologist Ashok Ranade reminds us (paraphrasing the medieval scholar Śārṅgadeva (1175–1247)), the Sanskrit word ālapti means ‘to express or elaborate raga’ (Ranade 2006: 176).

In order to distil this melodic essence, ālāp loosens its bonds with rhythm—with tāl and lay. Hence, during the ālāp that opens practically every Hindustani classical performance, the accompanying drum—tabla or pakhāvaj—is silent. Alone under the spotlight, the vocal or instrumental soloist is able to extemporise and explore a rāg at their own pace, free from any manifest pulse or metre—a condition known as anibaddh. Vocalists are also largely liberated from the constraints of text, instead singing non-semantic syllables.

Ālāps vary enormously in length—in contemporary practice, lasting anything from about a minute to over an hour. They also vary in form, according to whether the soloist is a vocalist or instrumentalist; according to genre (for example, khayāl, dhrupad); according to gharānā (stylistic school); and according to performance circumstances. Audio Example 3.2.1 illustrates ālāp in the context of khayāl and the circumstances of the album Rāg samay cakra, in which rāg performances are compressed to an average of just five minutes; here we have the opening track, in which Vijay Rajput sings the dawn rāg, Bhairav.

|

Audio Example 3.2.1 Rāg Bhairav, ālāp (RSC, Track 1, 00:00–02:01) |

We might describe this unaccompanied, prefatory stage of a rāg performance as the ālāp ‘proper’. But—importantly—the principles of ālāp often also manifest in the subsequent stages of a performance. In khayāl, a soloist often returns to this manner of singing during the subsequent bandiś (composition), alongside the tabla which now sustains the tāl. In such passages, nibaddh (metred) and anibaddh (unmetred) states co-exist as the rāg is further developed—a process sometimes known as vistār; I examine this matter further in my discussions of choṭā khayāl principles (Section 3.3) and baṛā khayāl principles (Section 4.3). In instrumental performance, and in vocal performances in the dhrupad style, the ālāp proper may be followed by two further stages, joṛ and jhālā, which invoke a pulse, though not yet the metrical rhythmic cycle of tāl (and usually still without drum accompaniment). While these stages are also considered part of the ālāp process, I do not extensively discuss them here, as they are not directly relevant to khayāl, my main topic of inquiry.

Given the significance of ālāp to Indian classical music, learning how to improvise in this fashion is paramount for a student. Indeed, this goes hand in hand with learning a rāg. The latter involves the student imitating phrases sung or played to them by their teacher in rhythmically free form, from simple to more complex, from lower register to higher register and back, so as gradually to internalise the characteristic behaviour of each svar and the rāg’s repertory of melodic formations. In effect, this is the same process as fashioning an ālāp.

Just about every musician will affirm that learning mimetically like this is the only way truly to acquire such skills. They will probably also recommend close listening to performances and recordings by the great masters and other professional artists (increasingly possible in an internet age, and an opportunity afforded by the albums accompanying the present volume). While this wisdom is unimpeachable, it is also true that pedagogy is not entirely uninformed by theory, including the legacy of the śāstras—the historical Indian treatises on music and performing arts. For example, in one of the most thoroughly researched accounts of ālāp in anglophone musicology, Ritwik Sanyal and Richard Widdess (2004: 144–52) show a continuity between rubrics for ālapti set out in Śārṅgadeva’s thirteenth-century treatise, Saṅgīta-ratnākara (2023/1993: 199–201), and ālāp performances by present-day dhrupadiyās—findings not without relevance to khayāliyās. While Widdess’s investigation (with which I dialogue below) analyses Sanyal’s own ālāp practice against the background of this wider historical context, my approach here is more inductive, seeking to channel rubrics for performing a khayāl-style ālāp from VR’s renditions on Rāg samay cakra and from my own experience of learning from him. Nonetheless, this will also reveal a degree of consistency with historic formulations; and I will also seek to draw out some generalisable theoretical principles from my analysis.

I approach my question, How Do You Sing an Ālāp?, through three explorations, each involving close musical analysis. In effect, these are self-contained essays that could be read in any order. In the first and longest, I consider ālāp formation: how does a performer shape an ālāp, both across its entire span and from phrase to phrase? In the second, I undertake an empirical analysis of duration and proportion in an ālāp: how long should an ālāp last, both in absolute terms and relative to its place in a rāg performance as a whole? And in the third exploration, I broach the under-examined issue of what it is that khayāl singers sing instead of words in an ālāp: how do they select and combine non-lexical syllables?

Exploration 1: Ālāp Formation

Although an ālāp is improvised, and approaches to it vary between artists and gharānās, this does not mean that anything is possible. An ālāp must take a coherent shape, beyond mere rāg-based noodling. ‘What is your plan?’, VR once provocatively asked me in a lesson, after I sang him a rather formless ālāp. Listen to any of the ālāps on Rāg samay cakra and it is clear that he always has a plan, even if an unconscious one. How, then, does a performer shape an ālāp—give it form, and in the process elicit a rāg? In this exploration, I approach this question through two stages of inquiry. First, I explore VR’s ālāp in Rāg Bhairav in its entirety as a case study. In the second stage, I widen the discussion, selecting extracts from Rag samay cakra as a whole, in order to explore variants of this and other principles identified in the case study.

Key to Exploration 1 are a number of theoretical terms that encapsulate certain essential processes of an ālāp and its melodic materials. Some of these terms come from explanations VR has given me verbally in class; others are adapted from western music theory; and yet others I have devised myself. Although I introduce these concepts individually as the account proceeds, I also summarise and further explain them at the end of Exploration 1. Readers may want to consult that passage for reference as they work through the analysis below.

Case Study: An Ālāp in Rāg Bhairav

Since every performer needs to know how to begin their performance, and since we have already listened to VR’s Bhairav ālāp in its entirety (Audio Example 3.2.1), let us now consider how he creates the sense of an opening—as extracted in Audio Example 3.2.2.

|

Audio Example 3.2.2 Rāg Bhairav, ālāp: opening (establishing phase) (RSC, Track 1, 00:00–00:37) |

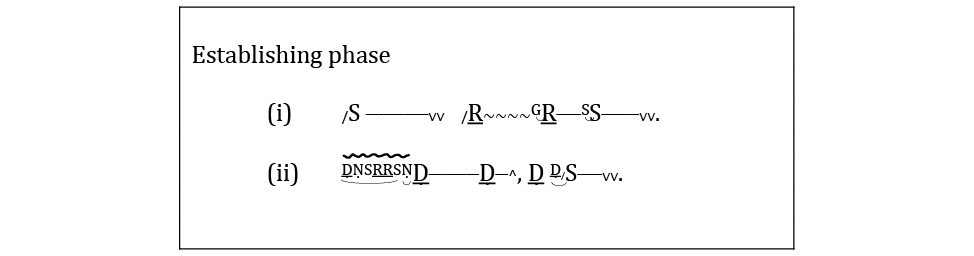

What do we hear in this passage? To begin with, the omnipresent drone of the tānpurā and just a hint of the rāg to come as harmonium player Mahmood Dholpuri discreetly touches komal Re in the background. But the first main event is VR’s entry at 00:07, where he sustains Sā, centring himself in his svar, the felt inner life of the note. Svar begins to mutate into rāg, and this single tone into a phrase, as he moves from Sā to Re; and he allows us to hear just a little flash of Ga, as a grace note (kaṇ), before descending back to Sā. These details are notated in Figure 3.2.1, phrase (i).

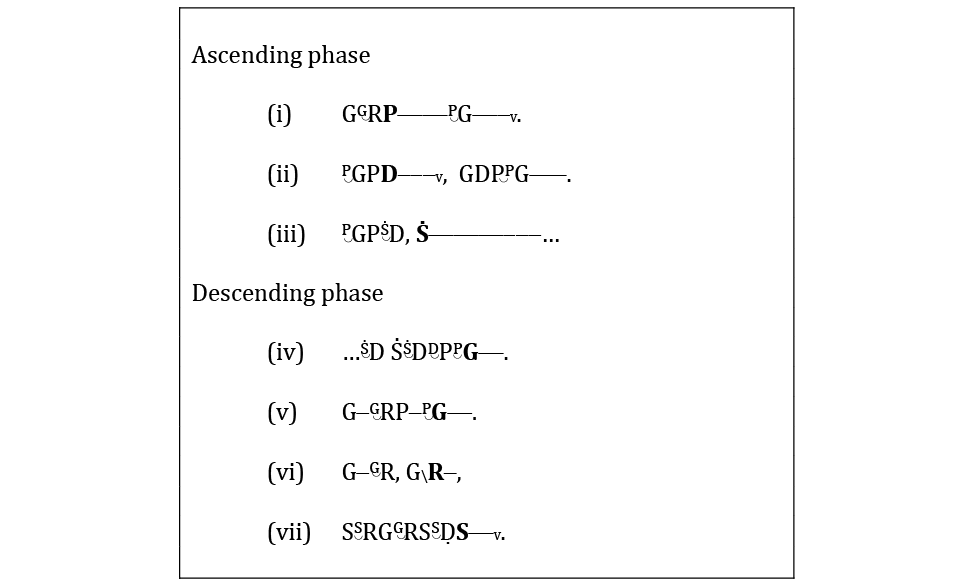

Fig. 3.2.1 Ālāp in Rāg Bhairav: opening (establishing phase), transcription. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

This transcription also includes VR’s next phrase, (ii), which begins with a rapid flourish of notes—the ornamental figure known as murkī—and then sustains komal Dhā in the lower octave; following this, as before, we return to Sā.

From even this tiny amount of material, there is already much we can glean about how to perform an ālāp. First, as we have already begun to observe, what VR sings is more than a plain sequence of pitches. The sustained tones—notated (approximately to scale) with extended lines in Figure 3.2.1—are variously approached, enlivened, or ended by various kinds of ornamentation (alaṅkār). The more explicit decorations, such as kaṇ and murkī, are indicated with superscripted sargam letters. Below this threshold are other embellishments that would be distractingly cumbersome to spell out: instead, the initial approach to Sā from an unspecified pitch space and the subsequent glide (miṇḍ) up to Re are shown with an oblique (/); continuous oscillation (āndolan) (as applied here to Re) is shown with a string of tildes (~~~), while a shake or mordent at the end of a note (one possible understanding of the term kampit) is indicated with one or more wedge or inverted wedge symbols (for example, ^, ∨∨); the application of gamak (a wide shake), is shown with a wavy line. Meanwhile, other microscopic fluctuations are left for discerning ears to savour. (For more on ornamentation see Section 1.8.)

For the performer, there is a careful balance to be struck between sustained notes and decoration. ‘Just relax’, VR might advise; ‘take your time, don’t make it too busy’. Indeed one of the distinguishing features of Hindustani classical music is the prevalence of sustained notes during ālāp—as compared with its Karnatak counterpart, which places ornamentation much more in the foreground. VR sometimes refers to the sustained (or ‘standing’) notes in khayāl with the older śāstric term, nyās svar (see Jani 2019: 24; Ranade 2006: 233). As is so often the case, the meaning of this Indic term is mutable: nyās can also mean the note on which a phrase or a rāg ends—which may or may not be the same as any of its sustained notes. Ambiguities aside, such notes provide a crucial melodic focus to each phrase; hence I sometimes also refer to them below as ‘organising pitch’ or ‘goal pitch’ (the latter borrowed from Sanyal and Widdess (2004: 145)).

The second point we should infer from this opening phase of VR’s Bhairav ālāp is his projection of the rāg’s grammar. Which notes can be sustained, which ones have a more decorative role, and in what fashion, will depend on the rāg. In this example in Bhairav, VR sustains the vādī tone, Re, in the first phrase, and the saṃvādī tone, Dha, in the second. In fact, in Bhairav, most pitches—with the qualified exception of Ni—can be sustained in some manner, as we will eventually hear.

Thirdly, we should note how the two short phrases transcribed in Figure 3.2.1, form a balanced pair—evidence of a plan. Each begins and ends on Sā; the first phrase ascends to the vādī tone and the second descends to the saṃvādī, as already noted. The first phrase begins to explore the middle octave (madhyā saptak), the second the lower octave (mandra saptak). And while the first phrase is longer than the second (around seventeen seconds compared to around twelve seconds), the two might still be perceived as durationally equivalent because they are relatively equivalent in substance. There is elasticity in the equivalence, a stretchy periodicity whose unit of measurement is something closer to a breath rather than a beat. (This observation complements Widdess’s identification of a subliminal pulse in the ālāp practice of Sanyal (Sanyal and Widdess 2004: 176–80).)

All the material we have considered so far constitutes what I term the establishing phase of an ālāp. This is, in turn, part of a larger phase schema for the ālāp as a whole—a notion explored below. Introducing another theoretical concept, adapted from western music theory, we can say that the establishing phase starts to map out svar space (pitch space) around Sā. By voicing vādī and saṃvādī, and their associated āndolan, VR introduces those colours fundamental to the rāg’s identity. Above all, the establishing phase confirms Sā as the embracing tonic—as the key reference point, and ultimate point of departure and return. While there is no single way to execute the establishing phase, the structure that VR adopts here is classic, and can be summarised in the following simple rubrics:

- Sustain Sā.

- Explore the svar space slightly above and return to Sā.

- Explore the svar space slightly below and return to Sā.

What next? In a nutshell, over the course of the rest of the ālāp, VR fully establishes the rāg by: (i) fashioning a series of similarly well–formed phrases that gradually ascend to tār (upper) Sā; and then (ii), in a somewhat shorter timescale descend back to madhya (middle) Sā. In this, we see how, behind the music’s surface, the basic āroh–avroh contour of the scale of the rāg provides a structuring framework (as it does for just about every other facet of musical material in a performance). I refer to these complementary trajectories as the ascending phase and descending phase of the ālāp.

In our Bhairav example, VR ascends to tār Sā between 00:38 and 01:32, and returns to madhya Sā between 01:32 and 01:59. However, his ascent is made indirectly: in an intermediate ascending phase, he gets some way towards the goal, but breaks off with a descent back to Sā; then, in a concluding ascending phase, he resumes his ascent, this time completing the journey to tār Sā. Let us consider these individual phases in more detail.

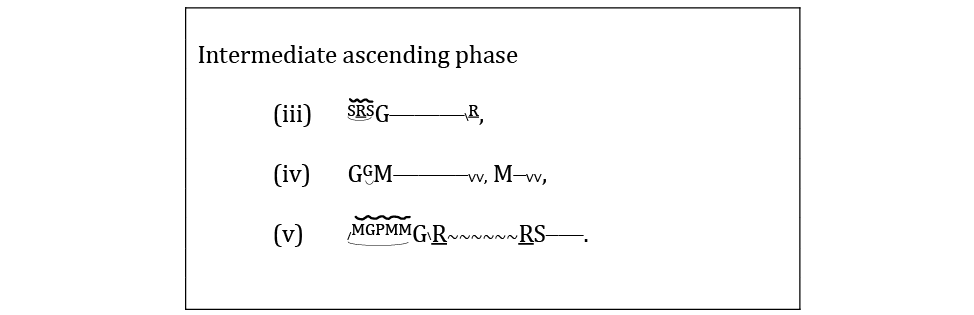

The intermediate ascending phase is extracted in Audio Example 3.2.3 and notated in Figure 3.2.2. In phrase (iii), VR improvises around Ga, picking up from the highest pitch of the establishing phase. Next, in phrase (iv), he rises to Ma and reinforces it—for Ma has structural salience in Bhairav. Then, in phrase (v), he quits the ascent and returns to madhya Sā, lingering on the vādī tone, Re, whose significance and character are highlighted by the decorative murkī that leads into it and the āndolit (microtonal oscillation) that prolongs it.

|

Audio Example 3.2.3 Rāg Bhairav, ālāp: intermediate ascending phase (RSC, Track 1, 00:38–01:01) |

Fig. 3.2.2 Ālāp in Rāg Bhairav: intermediate ascending phase, transcription. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

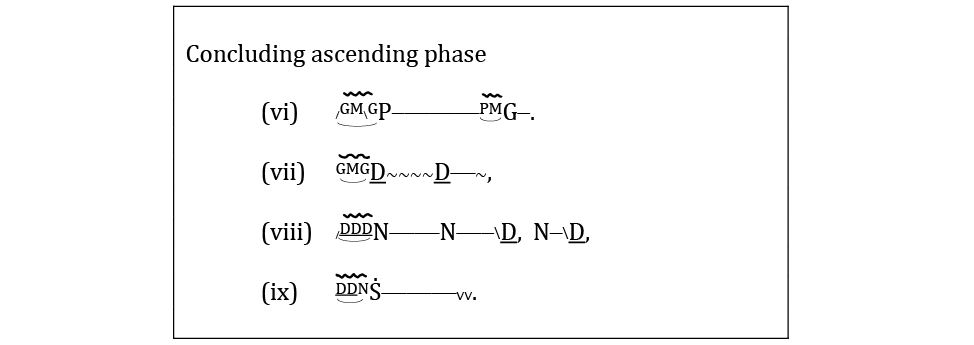

The concluding ascending phase is captured in Audio Example 3.2.4, and notated in Figure 3.2.3. The initial organising pitch, in phrase (vi), is Pa, which terminates with a momentary deflection back to Ga. The next two pitches on VR’s trajectory, voiced in phrases (vii) and (viii), are Dha and Ni; in the latter phrase they are heard in conjunction, illustrating the acute sensitivity between them in Bhairav. On the one hand, Ni strongly implies upward resolution to tār Sā, the goal of this phase; on the other, Dha also points downward to Pa, suggesting another deflection from the ultimate goal of the passage. However, this time, VR sees the implied ascent through to its conclusion and in phrase (ix) rises from Dha to tār Sā—another way in which Dha may behave under the rāg grammar of Bhairav (and in any case here catching Ni again in an ornamental kaṭhkā on the way). Such decisions can retrospectively change our understanding of what we heard prior to them. It is only because VR chooses to proceed to tār Sā that we hear this passage as the concluding phase of the ascent; had he chosen to reverse course after phrase (viii) and returned from Ni to madhya Sā—a stylistically available option—the whole passage would have instead been be perceived as a second intermediate phase. (For more on the changing significance of ālāp material in real time, see Clarke 2017: paras. 6.1–6.5.)

|

Audio Example 3.2.4 Rāg Bhairav, ālāp: concluding phase of ascent to tār Sā (Track 1, 01:02–01:32) |

Fig. 3.2.3 Ālāp in Rāg Bhairav: concluding ascending phase, transcription. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

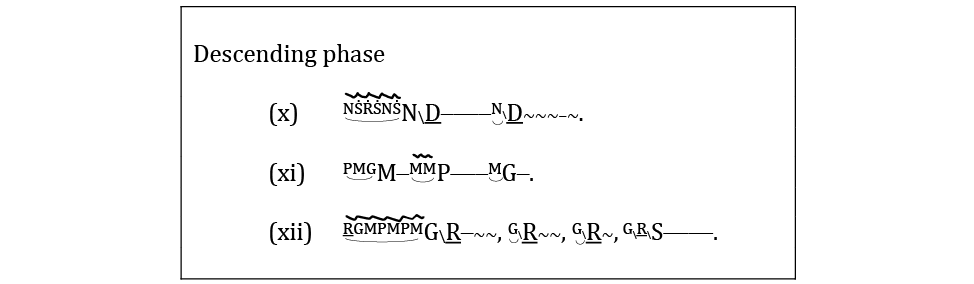

Having achieved tār Sā, VR now embarks on the descending phase of his ālāp. Following convention, this is accomplished in considerably less time than the ascending phase (I discuss the question of the relative duration of ālāp phases in Exploration 2, below). The descent is executed in a single span from tār Sā to madhya Sā, though the pathway has its twists and turns—as can be heard in Audio Example 3.2.5, and seen in Figure 3.2.4. In phrase (x), VR echoes the preceding coupling of Dha and Ni; in phrase (xi), he approaches sustained Pa elliptically via Ma, and follows it with a drop to Ga. Behind the ornamentation, the overall trajectory of these two phrases yields the pattern N–D–M–P–G—a vakra (crooked) formation congenial to Bhairav. In the final gesture of the descent, phrase (xii), VR exploits the particular qualities of Re in this rāg. Paralleling the association between Ni and Dha in the upper tetrachord, Re is here approached via Ga, which creates a longing for continuation to, and closure on, Sā. Initially, that implication remains unfulfilled while VR repeats the G–R motion three more times, stretching out the moment, until finally resolving to Sā.

|

Audio Example 3.2.5 Rāg Bhairav, ālāp: descending phase (return to mahdya Sā) (RSC, Track 1, 01:32–02:01) |

Fig. 3.2.4 Ālāp in Rāg Bhairav: descending phase, transcription. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

By way of summary, we can extrapolate from the particulars of VR’s performance some rubrics for how to execute the ascending and descending phases of the ālāp (this list continues the one given above for the establishing phase):

- Maintaining a balance between sustained and ornamental tones throughout, improvise a series of phrases, progressing steadily through the āroh scale of the rāg; continue until you reach tār Sā. This creates the ascending phase.

- You may interrupt the ascending phase partway along by a return to Sā, to form an intermediate phase of the ascent.

- If you take this option, you should next resume the ascending phase. You do not need to begin again at madhya Sā, but can pick up either from where you left off or in the space between Sā and that point.

- On reaching tār Sā, return to madhya Sā, using the avroh scale. This creates the descending phase, which should be shorter than ascending phase.

- Throughout, ensure the rāg grammar is projected; stay mindful of the vādī and saṃvādī tones, of other nyās (sustainable) svars that are important to the rāg, and of melodic motions salient to the ascending or descending phases. Not all of these features need to be projected equally prominently, but attending to at least some of them will help you convey the salient qualities of the rāg.

Phase Schema: Variations

At this juncture, we need briefly to pause to absorb the following points: the rubrics sketched out above are primarily heuristic; they do not represent universally applied principles, but offer pragmatic guidelines for what may take place in an ālāp; variants of them are possible, and indeed common. For example, the complete ālāp schema—establishing, ascending and descending phases—is often abbreviated in order to proceed more directly to the entry of the bandiś (which is always felt to be waiting in the wings). In the ensuing section I will consider some of the ways in which the duration and ambit of a khayāl ālāp can be expanded or contracted, and its content elaborated, simplified or nuanced. Looking ahead to later sections, we should also note that what a performer does or does not do in their ālāp may well have an impact on the succeeding khayāl stage of the performance, and vice versa. For example, a choṭā khayāl may resume the uncompleted āroh trajectory of an abbreviated ālāp in a series of rising bol ālāp passages (discussed in Section 3.3). And a baṛā khayāl often requires only the most perfunctory ālāp, since it may assimilate the contour of the entire ālāp phase schema into its own initial process—as manifested in the staged ascent of its baṛhat phase to tār Sā, and the eventual descent of the culminating antarā back to madhya Sā (discussed in Section 4.3).

But for now, let us consider some inflections of the rubrics derived from our case study, in order to get a sense of the wider spectrum of possibilities for an ālāp in the khayāl style. The supplementary rubrics below pick up from the ones above, and are each followed by an explanatory gloss. Rubrics 9–15 consider the construction of phases, rubrics 16–19 the formation of phrases. My examples draw largely from subsequent tracks on Rāg samay cakra, so also offering a wider window onto the album as a whole.

- While madhya Sā is usually the organising pitch of the establishing phase, you do not have to make this the very first note you sing (cf. rubric 1).

A theoretical distinction from the śāstras—one also made by VR—is useful here. This is between grah svar, a note on which you may begin a phrase, and nyās svar, a note which you may sustain, or which may act as a goal (as discussed above). Hence, while Sā functions as the nyās svar of the establishing phase, any other note appropriate to the rāg may serve to initiate it.

For example, on Rāg sama cakra, Track 2, VR begins Rāg Toḍī by dwelling on Re and Ga before falling to Sā (Audio Example 3.2.6, 00:25–00:51). This is consistent with the rāg grammar for Toḍī, in which Ga is the saṃvādī tone and Re can also be given prominence in conjunction with it. Following this (00:52–01:13), VR steps back up to Ga from mandra Dha, the vādī of the rāg, before once again returning to Sā. All this underwrites the particular importance of the vādī and saṃvādī in this rāg, which at times rival Sā.

|

Audio Example 3.2.6 Rāg Toḍī, ālāp: establishing phase (RSC, Track 2, 00:00–01:13) |

- In the establishing phase, when exploring the space below Sā, do not normally go any lower than the upper tetrachord of the lower octave (cf. rubrics 2 and 3).

While it is possible in principle to go all the way down to mandra Sā in an extended ālāp, in a shorter khayāl ālāp one would not normally explore more than four or five notes below Sā—in other words, confining oneself largely to the upper tetrachord (uttaraṅg) of the lower octave (mandra saptak). In Rāg samay cakra the deepest VR goes in his lower-octave explorations is to mandra Ma—most notably, in Rāg Mālkauns, as heard in Audio Example 3.2.7. Here Ma is the vādī; the opening up of svar space between it and Sā prolongs the establishing phase, capturing the particular gravity of this rāg.

|

Audio Example 3.2.7 Rāg Mālkauns, ālāp: establishing phase (RSC, Track 12, 00:18–01:37) |

- You may create more than one intermediate ascending phase; this/these should be each based around successively higher notes within the rāg, according to its grammar (cf. rubric 5).

While, in our case study, VR includes just one intermediate ascending phase, further additional stopping-off points are possible. These should focus on successively higher pitches—those that are allowed to be sustained within the rāg grammar. Each intermediate ascent should return to mahdya Sā.

This principle is an important means of growing an ālāp and appears to be historically consistent with Śārṅgadeva’s division of his ālapti framework into gradually ascending phases, termed svasthāna (Śārṅgadeva 2023/1993: 199–200, also discussed by Sanyal and Widdess (2004: 145).

As we can hear on several tracks of Rāg samay cakra, VR follows through on the accumulating intensity of the ascending phase to rise to tār Re or Ga. In longer performances it would be possible to go even further, and in fact VR touches just momentarily on tār Ma at the peak of the ascending phase in Brindābanī Sāraṅg (Track 4, 01:30–01:52). As ever, such moves follow the grammar of their respective rāg and serve to bring out its particular emotive properties (ras). The following instances are illustrated by the respective excerpts in Audio Example 3.2.8:

- In Multānī, VR fleetingly sings tār Ga and tār Re as decorations of tār Sā, within the figure N–Ṡ–ĠṘṠNṠ—. This does not disturb the prominence of Sā as the saṃvādī of the rāg.

- In Toḍī, by contrast, VR voices tār Ga much more fulsomely after he has reached tār Sā. In this passage, he also emphasises komal Ga’s connection with komal Dha (as saṃvādī to vādī), as he did in the lower register (cf. Audio Example 3.2.6). This plangent rendering of upper Ga evokes the karuṇ ras, which is associated with this rāg.

- In Pūriyā Dhanāśrī, VR moves to tār Re before he settles on tār Sā, in a phrase that can be distilled as G–Ḿ–D-N—, N-D–N–Ṙ–N–D-P—. Shortly afterwards, we hear tār Re again, this time following the attainment of tār Sā; once again the higher note is touched on elliptically via Ni, in a movement that skirts around tār Sā. All these figures help create the particular expressive colouristic palette of this sandhi prakāś (twilight) rag.

|

Audio Example 3.2.8 Ascents beyond tār Sā: |

Whereas rubrics 11 and 12 showed how the notional phase schema can be expanded, here we consider ways in which its elements can be contracted, or even simply not applied.

Foreshortening of the ascending phase is common when an ālāp needs to be concise. Often this is the case prior to a baṛā khayāl, where an overly developed ālāp would upstage the following khayāl, which, after all, is meant to be the main focus of the performance. For example, in both ālāps on the Twilight Rāgs album, VR takes the ascending phase only as far as Pa.

But brevity—actual or relative—is only one factor. In VR’s ālāp in Rāg Śuddh Sāraṅg (Track 3), where the ascending phase stops at Pa (Audio Example 3.2.9, 00:00–01:03), we can assume brevity not to be top priority, because he then allows himself a second ascent to the same pitch (Audio Example 3.2.9, 01:03–01:34).

|

Audio Example 3.2.9 Rāg Śuddh Sāraṅg, ālāp (RSC, Track 3, 00:00–01:35) |

VR’s motive for stopping at Pa is more likely not to overshadow the generally low profile of the first line of the following bandiś. When I asked him about this, he replied that this was not a conscious decision, though, interestingly, he did affirm a wider principle: ‘you must let the khayāl influence your ālāp; the ālāp is not just your creation, but is influenced by lots of things. You have to know the meaning of the bandiś and match its style in your ālāp’.

This point is further illustrated by a presentation in Rāg Bhairav on the Music in Motion (AUTRIM Project) website (Rao and Van der Meer n.d.: https://autrimncpa.wordpress.com/bhairav/, 01:06–02:10). Here, vocalist Padma Talwalkar progresses the ascending phase of her ālāp only as far as Dha; on the return journey to Sā she pauses on Ga. These prominent tones prepare the svar space for the same pitches in the opening of the bandiś ‘Jāgo mohan pyāre’, which flows on almost seamlessly in a beautiful transition into the khayāl that obviates any further exposition of the ālāp. This example nicely illustrates the point made at the opening of this section, that the ascending phase of an ālāp is often curtailed in order not to overly delay the entrance of the bandiś.

In other circumstances, it may be possible to dispense with the ascending and descending phases of the ālāp altogether. Many khayāl performances present only the establishing phase of an ālāp—enough to affirm Sā and indicate the essential characteristics of the rāg which are then fully explored in the ensuing khayāl. In such cases, this is usually a baṛā khayāl, and the prescinded form of the ālāp resembles the form known as aucār. Examples include Gangubai Hangal’s (1913–2009) recording of Rāg Bhairav (1994) or Kumar Gandharva’s (1924–92) rendition of Mālkauns (1993).

Some rāgs, known as uttaraṅg pradhan rāgs, emphasise the upper tetrachord. In such contexts, phrases may be oriented around tār Sā rather than madhya Sā, taking this higher pitch as their starting point and/or ultimate goal. One such rāg is Basant, whose vādī is identified by Bhatkhande as, explicitly, tār Sā (see Section 2.5.14).

This characteristic can be heard in the bandiś ‘Phulavā binata’, which VR chooses for this rāg (Track 14). Its opening sets out from tār Sā; and so, accordingly, does the ālāp which prefaces it. Here, then, VR is true to his maxim that what you do in your ālāp should relate to the content of your khayāl. Indeed, the phase schema of this ālāp unusually comprises two descending phases, both beginning on tār Sā, with no prior establishing or ascending phase. The first descent (Audio Example 3.2.10), pauses on Pa, then Ga. VR then momentarily drops further to mahdya Sā, but only as a jumping off point to sing the so-called Lalit aṅg, which involves both suddh and tivra versions of Ma sung adjacently—a figure that draws on the idiosyncratic grammar of Rāg Lalit. This motion resolves onto Ga, which could be heard as the goal tone of this first, intermediate descending phase.

|

Audio Example 3.2.10 Rāg Basant, ālāp: first descending phase (RSC, Track 14, 00:00–00:29) |

VR next steps back up through Ḿa and Dha to regain tār Sā; he redoubles this motion, touching on tār Re, and then curves back to begin the second descending phase (Audio Example, 3.2.11). This is initially modelled on the first descent; again, Pa and Ga function as intermediate goal tones. From Ga, VR makes a delightful rising deflection, Ḿ–N, before completing the descent to madhya Sā. This ends the ālāp and leads directly to the following drut ektāl khayāl, launched from the same uttaraṅg register.

|

Audio Example 3.2.11 Rāg Basant, ālāp: second descending phase, leading to opening of bandiś (RSC, Track 14, 00:29–01:06) |

(As a codicil to these observations, we should also note the complementary type of rāg, pūrvaṅg pradhan, which focuses on the lower tetrachord. Some rāgs are often considered in complementary pairs that exhibit similar scale forms and qualities but privilege opposite tetrachords. Well-known examples include Darbārī Kānaḍā and Aḍānā, which are pūrvaṅg and uttaraṅg pradhan rāgs respectively; and, similarly, Bhūpālī and Deśkār.)

- The elements of the phase schema are not radically discrete; they should flow from one another as a continuous process; their identities may sometimes blur. Phrases do not always map onto phases.

These points are a reminder that the phase schema which we extrapolated from VR’s Bhairav ālāp is more an implicit, notional framework behind the music’s surface than an explicit, empirical structure that manifests on every occasion. The actually sung phrases do not always align with the theoretical phases of the schema.

We can hear this by revisiting the extract from Pūriyā Dhanāśrī, discussed under rubric 12, above—Audio Example 3.2.8(c). In the elliptical turn around tār Sā the ascending phase blends seamlessly into the descending phase within a single sung phrase. Here, phase boundary and phrase boundary do not coincide. Contrast this with the equivalent point in Rāg Yaman—Audio Example 3.2.12. Here, after ascending from Ni to tār Sā, VR sustains this goal pitch, winds joyful variants of the decorative figure N–D–N–Ṙ around it, then takes a short breath; this phrase and the ascending phase are both over. In a new phrase (at 00:25 on the audio example), he sings tār Sā again, and begins the descending phase. Here, then, phrase and phase are in alignment. Even so, there is no change of idiom at the turning point; we still sense continuity between the successive ph(r)ases.

|

Audio Example 3.2.12 Rāg Yaman, ālāp: turn from ascending to descending phase (RSC, Track 9, 02:19–02:56) |

In VR’s realisation of Bhīmpalāsī, we find a subtle blurring of identity between all the elements of the ālāp’s phase schema, none of which precisely aligns with the manifest phrases—as we can trace in Audio Example 3.2.13. In the establishing phase (00:00–00:18), VR merges the motion below and above the initially sustained Sā into a single phrase: S—, .P–Ṇ–S–G—R–S. Already this elicits an ascending tendency beyond the immediate svar space around Sā, to Ga; and this blends into the trajectory of the subsequent intermediate ascending phase, to Ma, to Pa, to Ni (00:19–00:43)—before returning to Sā (00:44–01:00). This non-alignment of the phase framework with the phrase structure continues in the concluding ascending phase (begins 01:00), where the attainment of tār Sā (at 01:21) melts into the beginning of the descending phase back to madhya Sā, all within a single arc.

|

Audio Example 3.2.13 Rāg Bhīmpalāsī, ālāp (RSC, Track 5, 00:35–02:26) |

A similar compression of establishing, ascending and descending phases can be heard in VR’s ālāp for Rāg Bihāg (Audio Example 3.2.14). Striking here is the way practically all phrases are drawn magnetically to Ga, the vādī of the rāg and a recurrent goal pitch (nyās svar) whose force of attraction becomes a key organising principle, working in productive tension with the phase schema.

|

Audio Example 3.2.14 Rāg Bihāg, ālāp (RSC, Track 11, 00:00–01:34) |

The phrases discussed in these examples are so fluidly conjoined that it may seem arbitrary to conceptually separate them into different phases at all. Nonetheless the phase schema remains discernible, even if, in these circumstances, it is sensed as a more abstract presence behind the sensory formation of actual phrases. This tells us that these discrete but interacting principles are both part of an ālāp’s organisation. And it also tells us that the way successive phrases are conjoined is an important aspect of how to sing an ālāp. It is to this matter that we turn next, in a further set of rubrics.

Phrase Formation and Succession

- In each phrase of the ascending phase, do not generally go higher in your melodic elaborations than its organising pitch or goal tone. However, you may subtly allude to the organising pitch of the next phrase as you approach the end of your present one.

The sustained organising pitch (nyās svar) of a phrase represents a kind of ceiling. The musical elaborations that decorate this pitch should normally come from below—from the svar space that you have already begun to open up—so as to deepen the impression of the rāg as so far unfolded, rather than steal the thunder of what is coming up. However, this is more of a general principle than an abstract rule, and may sometimes be relaxed. In particular, it can be appropriate to give a discreet hint of the nyās svar of the next phrase as you reach the end of your present one. To illustrate this, let us briefly revisit the intermediate ascending phase of VR’s ālāp in Rāg Bhairav—as captured in Audio Example 3.2.3 and Figure 3.2.2. Here the goal tone is Ma, attained and sustained in phrase (iv); and it is approached from Ga, sustained in phrase (iii). Within each of these phrases, the sustained tones are elaborated by notes no higher than themselves. Nonetheless, once he reaches Ma, VR turns back to Sā with a murkī that fleetingly touches on Pa: for those with sharp ears, this anticipates the organising pitch of the next phase.

Just as an ālāp does not have to begin on Sā (rubric 9) so any phrase can begin on a note other than its organising pitch. To reiterate the terminology of the historical treatises, there is a distinction between grah svar, a note on which you can begin, and nyās svar, a note which you can hold. (Of course, in order to comply with rubric 16, the former must not be higher than the latter.) This is clearly illustrated in the extract from Bhairav just considered.

Even though the sustained, organising pitch of a phrase is usually perceived as its goal, it does not have to be sustained right to the phrase’s end. We can see examples of such behaviour in Figure 3.2.5, which notates the ascending and descending phases of VR’s Bhūpālī ālāp, as heard in Audio Example 3.2.15 (I do not consider the establishing phase here). We can readily note that in phrases (i) and (ii) the respective organising pitches Pa and Dha—shown in bold—are approached from Ga, below (cf. rubric 16), and are then quitted with a drop back to Ga. While not compulsory, this return helps keep the svar space below each goal pitch (indeed also the vādī svar) alive as VR progresses through the ascending phase.

|

Audio Example 3.2.15 Rāg Bhūpālī, ālāp: ascending and descending phases (RSC, Track 8, 00:34–01:30) |

Fig. 3.2.5 Ālāp in Rāg Bhūpālī: ascending and descending phases, transcription. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

We can note a related property in the same Bhūpālī ālāp—namely that successive phrases often start by revisiting part of the earlier svar space, creating a svar-space overlap. For example, in Figure 3.2.5 while phrase (i) reaches Pa, phrase (ii) begins on Ga below it, before attaining Dha; phrase (iii) also starts on Ga, before ascending even higher, to tār Sā.

Svar-space overlaps may occur in the opposite direction. In the descending phase of the Bhūpālī extract, phrase (iv), dropping from tār Sā, has Ga as its goal; Ga remains the goal tone of the next phrase, (v), which backfills the previous pitch space by recapturing Pa, even as it also alludes to an impending descent by touching on Re. Similarly, the final phrase, (vii), begins on, and is organised around, Sā; but the phrase recoups the higher space of its forebear, in the motion SSRGGR–, before mapping out new pitch space in the lower octave—…SSḌS—.

The purpose of such overlaps is to foster connectivity between phrases and to keep the entire rāg alive and growing even when the focus is on specific organising pitches. This makes the point that it is the nurtured rāg itself—rather than the more abstract principles of the phase schema—that is the living heart of the music.

Summary: Terminology and Key Principles of Ālāp Formation

To conclude this Exploration, I here recapitulate and re-gloss some of the main technical terms used above, along with their associated principles. This is principally by way of summary, but it also points to the possibility of a formalised theory of khayāl-style ālāp—a potential future project.

- Ālāps progress through several phases: typically an establishing phase, an ascending phase (which may be subdivided into interim and concluding phases), and finally a descending phase. In this, my own nomenclature, I have preferred the word ‘phase’ to ‘section’ since it captures the essentially fluid nature of ālāps and the way they shape time. I use the term phase schema to signify this sequence as a whole.

- Ālāps comprise a succession of phrases. Pragmatically, we may describe a phrase as a short unit of melodic material articulated by a breath, pause or some other marker. While it is possible to make a theoretical distinction between different phrase levels (for example, ‘phrase’, ‘sub-phrase’), this has not been essential to our present purpose (for a formalised investigation of phrase grammar in ālāp, see Clarke 2017). A more useful distinction, pursued above, is that between the phrases and phases of an ālāp, which, significantly, do not always map onto each other.

- Phrases are usually organised around one or more sustained tones or standing notes—or, to use the śastric term for this, nyās svar, meaning a note which can be held or sat on. Eligible notes include the vādī and saṃvādī tones of a rāg but need not be confined to these. Nyās can also mean the note on which a phrase (or a rāg) concludes—which may or may not be the same as any of its sustained notes. In similar vein, goal pitch refers to an emphasised note within a given stage of an ālāp (Sanyal and Widdess 2004: 145). Depending on context, I have used all these terms, with their overlapping shades of meaning, as well as the general descriptor, organising pitch. It should also be clear that I have used ‘note’, ‘tone’ and ‘pitch’ largely interchangeably, none of which fully captures the meaning of the Hindavi term svar.

- The sustained, organising pitch of a phrase is usually embellished by various kinds of ornament (alaṅkār) which bring the svar to life. In the notation of individual phrases, I have not shown every microscopic detail of these, as important as they are, since my aim has usually been to foreground what is melodically structural.

- I have invented the term svar space (adapting the western theoretical term pitch space) to refer metaphorically to the compass of pitches available to decorate a sustained note. As an ālāp unfolds, and the rāg opens up, so the bandwidth of this space gradually increases. In the ascending phase, the available svar space lies primarily below the current sustained note. In the descending phase, because the svar space has already been fully opened up, there is somewhat freer movement through it. Perceptually, svar space is embedded as a trace in the memory, subtly regenerated as we pass through the ālāp, deepening the rāg.

Exploration 2: Duration and Proportion

One question that faces any soloist as they begin a rāg performance is, how long shall I make my ālāp? The possibilities are elastic. Musicians often nostalgically recount a mythological heyday (I have heard VR do this) when famed artists performed ālāps lasting up to two hours, making it possible to penetrate the true depths of a rāg. At the other extreme, an ālāp may last under a minute: accomplished performers know how to present a rāg’s essence in just a few phrases when necessary.

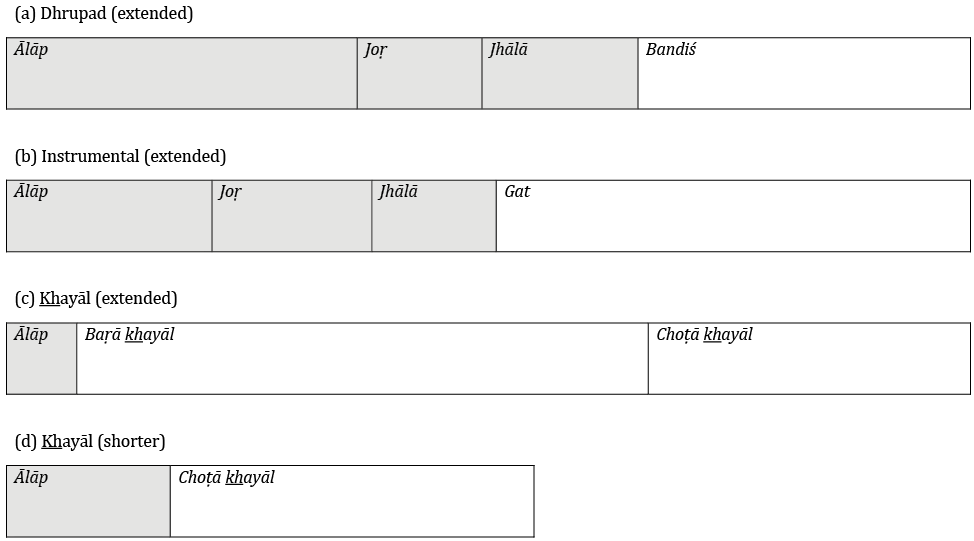

An ālāp’s duration—in both relative and absolute terms—is dependent on genre and performing context. Figure 3.2.6 considers several exemplary Hindustani classical genres, indicating typical proportions of their ālāp stage (shaded) relative to their composition-based stage (unshaded). These representations are highly schematic—approximate indications of events which may be variously extended, contracted, omitted or compounded, according to circumstance. The same rāg is of course performed continuously throughout.

Fig. 3.2.6 Relative duration of ālāp and composition stages in Hindustani classical genres. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

In part (a) we see how, in an extended dhrupad performance (whether vocal or instrumental), ālāp is the predominant feature. Even under present-day concert constraints and audience expectations, ālāps lasting between thirty and forty-five minutes are not uncommon; these will often include joṛ and jhālā sections, extending the ālāp proper, and invoking a regular rhythmic pulse, but not the full metrical apparatus of tāl (and usually without drum accompaniment). The succeeding bandiś (with pakhāvaj accompaniment) is proportionally much shorter—in absolute terms commonly lasting up to around ten to fifteen minutes, which still gives scope for extemporisation and development. In variants of this schema (usually in subsequent, lighter items of a programme), the ālāp stage may be less extensive, perhaps dispensing with joṛ and jhālā, and re-balancing the proportional relationship with the succeeding bandiś.

Instrumental rāg performances likewise often begin with an extended ālāp, typically lasting between fifteen and forty minutes, and also including joṛ and jhālā—as mapped in Figure 3.2.6(b). The composition (gat) section that follows (accompanied by tabla) is likely to be commensurably substantial. It may involve more than one composition, the first in a relatively slow (vilambit) lay or in madhya lay, the subsequent one(s) in drut lay. In lighter renditions, both ālāp and gat may be briefer, with joṛ and jhālā omitted.

In a khayāl performance, an ālāp’s duration depends to a large extent on what follows it. At the beginning of a programme, an ālāp is likely to preface a slow, extended baṛā khayāl, followed by a faster choṭā khayāl, the former imparting an aesthetic gravity comparable to dhrupad (a topic I discuss at greater length in Section 4.3). Paradoxically, this requires the ālāp to be radically shorter than is the case with dhrupad—compare parts (a) and (c) of Figure 3.2.6—since the opening stage of the baṛā khayāl itself draws on the anibaddh (unmetred) ethos of an ālāp. The ālāp proper is accordingly often reduced to just a few phrases, though it can be longer (as in VR’s ālāps on the Twilight Rāgs album, which last around three minutes). In subsequent or shorter concert items, the baṛā khayāl may be omitted, leaving just the ālāp and choṭā khayāl; this allows the ālāp scope for expansion—see Figure 3.2.6(d). Even so, there remains the question of proportion: it would be unusual for an ālāp to be longer than the succeeding choṭā khayāl.

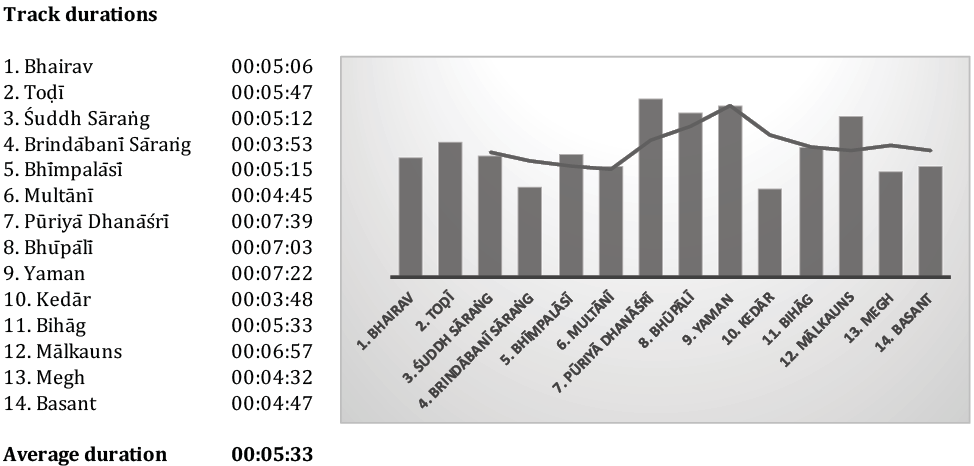

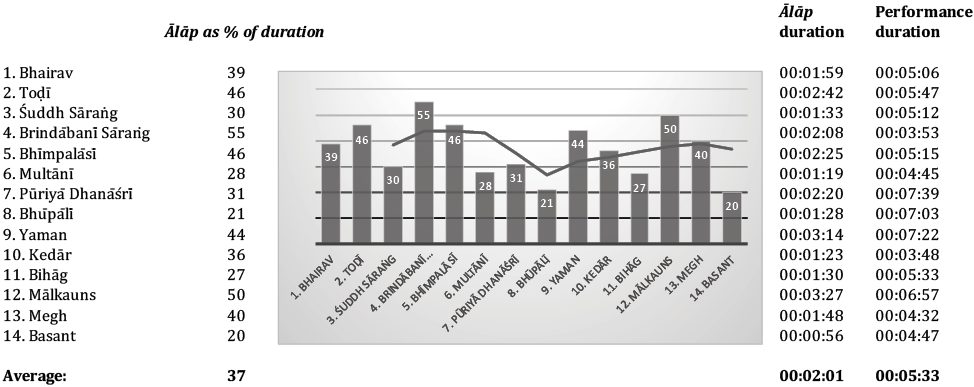

All the tracks on Rāg samay cakra follow the simpler, ālāp–choṭā khayāl schema shown in Figure 3.2.6(d). The album format and the pre-requirement to keep each rāg performance to an average of around five minutes serve as creative constraints at every level. At the level of the album as a whole, VR plays with the duration of tracks on either side of the mean length. This is demonstrated in Figure 3.2.7, which provides track data and a related column chart. Here we see significant variation in the length of performances, with Rāg Kedār at the shortest extreme (3’48”), Pūriyā Dhanāśrī at the longest (7’39”), and Bihāg lasting exactly the mean duration of the entire series (5’33”). These variations create a subtle ebb and flow in the large-scale pacing, which is tracked by the trendline mapped onto the column chart; this is based on a three-period moving average (i.e. the average duration of successive sets of three rāgs—of Tracks 1–3, then 2–4, then 3–5 etc.).

Fig. 3.2.7 Rāg samay cakra: track durations. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

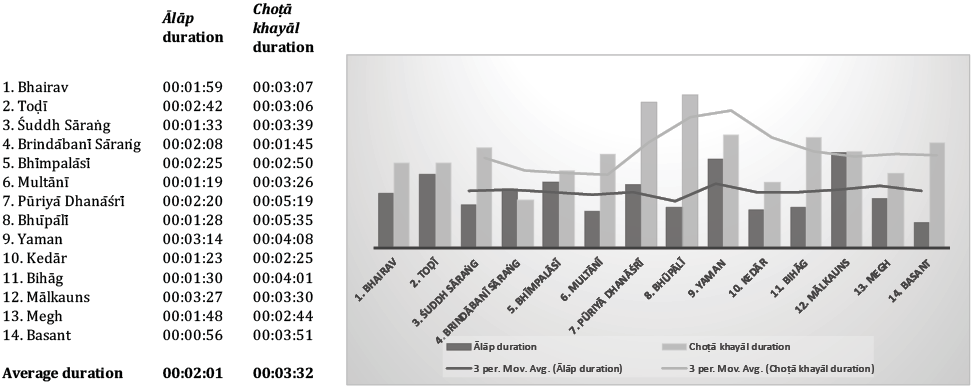

Figure 3.2.8 shows how VR varies the absolute and relative lengths of individual components—ālāp and choṭā khayāl—across performances. The durations of ālāps, range from 0’56” (Basant) to 3’27” (Pūriyā Dhanāśrī); with Bhairav, at 1’59”, clocking in close to the mean duration of 2’01”. (Instrumental introductions, whose lengths are also somewhat variable, are not analysed separately here, but rather included in the ālāp duration.) Similarly for choṭā khayāl durations: these range from 1’45” (Brindābanī Sāraṅg) to 5’19” (Pūriyā Dhanāśrī), with Mālkauns, at 3’30”, close to the mean of 3’32”. But interestingly, while ālāp and khayāl sometimes increase or decrease their three-period moving average length in step, at other times the trends proceed in contrary motion. We see flexibility in every dimension.

Fig. 3.2.8 Rāg samay cakra: ālāp and choṭā khayāl durations. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

These relativities are shown in another way in Figure 3.2.9, which charts ālāp length as a percentage of the overall performance duration. For example, in Bhūpālī and Basant, the ālāp only accounts for some 20% of the overall duration, whereas in Yaman this figure is 44%. And, unusually, in the cases of Mālkauns and Brindābanī Sāraṅg, the ālāp lasts half of the performance or more (50% and 55% respectively). If these seem relatively long durations, they remain acceptable because of the context: a sequence of many short performances, which would not be the norm in a live concert. Here, in the interests of creating a satisfying whole, VR seems to be teasing norms without violating them: the ālāps, which on average account for 37% of the performance time, do not overshadow the khayāls.

Fig. 3.2.9 Rāg samay cakra: ālāp durations as percentage of track durations. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

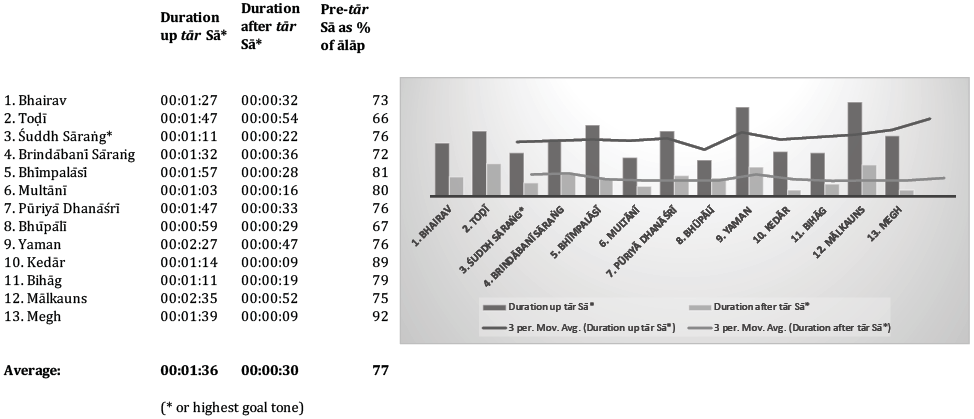

Finally, Figure 3.2.10 analyses duration within ālāps. This measures the periods before and after the arrival on tār Sā, a key goal in the phase schema (as discussed in Exploration 1). In the case of Rāg Śuddh Sāraṅg, which only ascends as far as Pa, I have taken the second ascent to this note as the point of measurement; and Basant is omitted from the data, because, as an uttaraṅg pradhan rāg, it begins on tār Sā and hence has no ascending phase as such (see rubric 14, above). As would be expected, this analysis shows the period prior to tār Sā (or equivalent highest note) to be significantly the longer, accounting for on average 77% of the overall ālāp duration. This is approximately the inverse proportion of the ratio of overall ālāp duration to overall performance duration shown in the previous figure.

Fig. 3.2.10 Rāg samay cakra: durations before and after reaching tār Sā within ālāp. Created by author (2024),

CC BY-NC-SA.

In summary, these analyses illustrate the extent to which the relative and absolute durations of an ālāp and its internal elements can be varied within a given performance context. The approach here is empirical—measurement based—and could be suggestive of a wider programme of analysis comparing, say, artists, gharānās and genres from similar standpoints across a wide corpus. But there is also the question of the performer’s phenomenology—of how duration is felt and judged in experience. This question has practical relevance for the student, since the pacing of a performance cannot be learnt just by looking at the clock—even though its absolute length may well be determined by an external agency, such as a concert organiser or album producer. Having presented VR with the empirical data assembled here, I asked him whether he had consciously intended any of the trends shown. He answered in the negative: the artists had begun recording the earlier rāgs in the cycle, and then got into a groove, encouraging each other through their interaction to develop the music artistically; the rest just followed. The data empirically evinced from the end-product of this process demonstrate that durational proportion is as important a factor as any other in Indian classical music, and can be similarly nuanced and creatively fashioned—indeed at several levels. But, like those other factors, this one also has to be internalised through a long period of practice and accumulated experience.

Exploration 3: Ālāp Syllables

Among the least explained aspects of khayāl are the non-lexical vocables—syllables without a meaning—that vocalists use when fashioning an ālāp. For all that this matter is barely talked about, these sounds are crucial, since a singer cannot sing without singing something, and the introductory ālāp of a khayāl does not, as a general principle, use any text. (This changes during a bandiś, when a singer may use the technique of bol ālāp, that is, ālāp-style passages which deploy words from the song text.) So, if you are singing a prefatory ālāp, what vocables should you use?

Two options might be sargam syllables and ākār (singing to the vowel ‘ā’)—as in the case of tāns. But, while your teacher may encourage you to sing sargam syllables while you are learning ālāp (to stay aware of what you are singing and the direction you are going in), it is less common to do so in an actual performance. Conversely, one might indeed use ‘ā’—but often this would be one of only several syllables. In practice, a large range of vocables is available: a sample taken from the ālāps VR sings on Rāg samay cakra includes ‘ā’, ‘a’, ‘nā’, ‘mā’, ‘e’, ‘re’, ‘de’, ‘ī’, rī, and ‘nū’—a syllabary typical of many khayāl singers. I spell these as if they were transliterated from Hindi, Urdu or Sanskrit, to reflect possible linguistic backgrounds, even though, in an ālāp, such syllables are non-lexical (they do not form parts of actual words) and non-semantic (they carry no conventional meaning).

When and how does a singer deploy such vocables? And, more speculatively, what is their source, and what logic governs their combination? In the following discussion, I will explore both these dimensions—the practical and theoretical—since each has a bearing on the other.

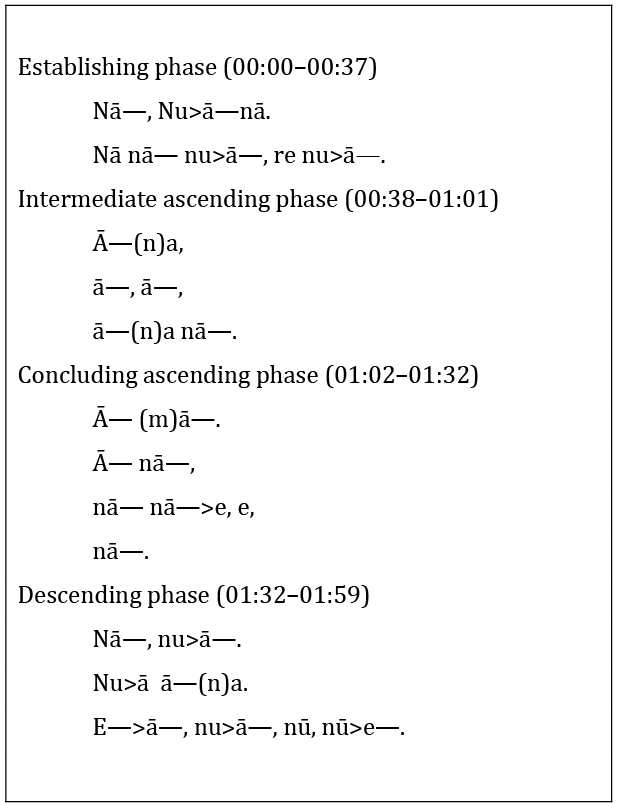

To begin with the practical, let us revisit VR’s ālāp in Rāg Bhairav, listening again to Audio Example 3.2.1, and giving particular attention to the syllables sung. Figure 3.2.11 transcribes these for each phase of the ālāp, in a layout corresponding to that of the sargam transcriptions in Figures 3.2.1–3.2.4.

|

Audio Example 3.2.1 [repeated] Rāg Bhairav, ālāp (RSC, Track 1, 00:00–02:01) |

Fig. 3.2.11 Rāg Bhairav, ālāp: syllable sequence. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

It is clear from Figure 3.2.11 that the two most common syllables in this ālāp are ‘nā’ and ‘ā’. The prevalence of ‘ā’ confirms ākār as an implicit underlying principle for ālāp singing. ‘Nā’ could be interpreted as an inflection of this which adds a soft dental consonant that focuses the initial articulation and tuning of svar—especially important in the establishing phase. In the ascending phase, VR uses ‘ā’ and ‘nā’ in full chest voice as he approaches tār Sā, to give a strong open sound—appropriately to this serious rāg. As he descends back to mahdya Sā, he returns to ‘nā’ and its variants, giving this performance a general symmetry. Prominent among these variants is ‘nu>ā’—which should be read as ‘nu’ morphing into ‘nā’. Initially, ‘nu’ is only briefly touched on, concentrating the beginning of the sound envelope at the front of the mouth before opening up to ‘ā’ at the back. At the end of the descending phase, VR more explicitly voices ‘nū’ as a vocable in its own right, before morphing it to ‘e’. A related tendency is his subtle shaping of the envelope of a vowel with a half-articulated ‘m’ or ‘n’—notated with parentheses in the Figure—which gives a subtle rhythmic nudge to the sustained vowel.

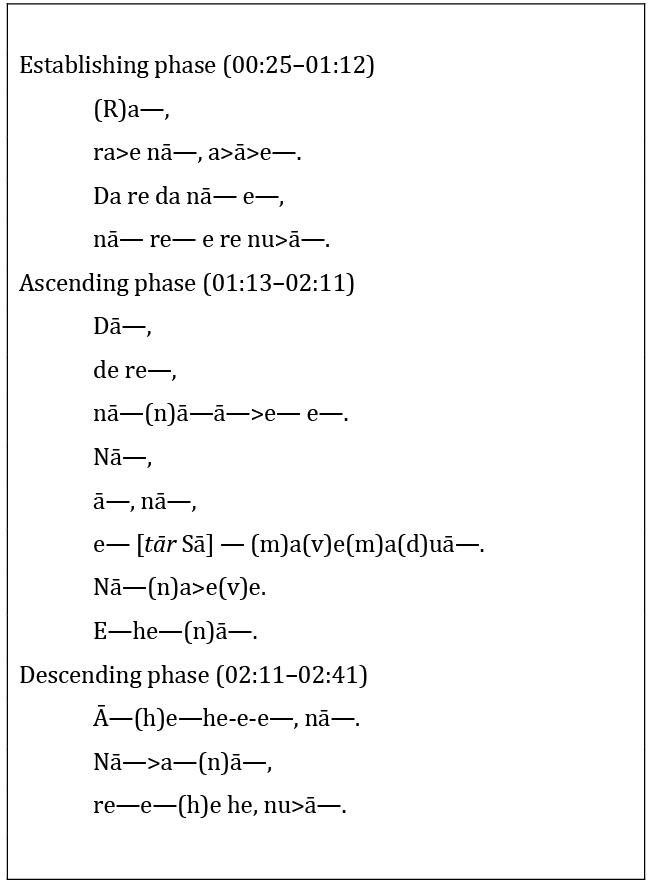

The syllabary in this ālāp, then, is carefully controlled: the overall selection is relatively confined; adjacent syllables are usually related; and contrasting ones—such as ‘re’—or less regular ones—such as ‘nū’—are used sparingly and/or at strategic moments. The penchant for morphing sounds is a more individual aspect of VR’s gāyakī; indeed, in the next track, Rāg Toḍī, we find an even more idiosyncratic application. VR’s ālāp in this rāg can be found complete in Audio Example 3.2.16; and its syllable sequence is notated in Figure 3.2.12, following the conventions used above.

|

Audio Example 3.2.16 Rāg Toḍī, ālāp (RSC, Track 2, 00:00–02:42) |

Fig. 3.2.12 Rāg Toḍī, ālāp: syllable sequence. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Syllables such as ‘da’, ‘de’, ‘re’ and ‘nā’, provide a sonic contrast to those VR deployed in his Bhairav ālāp. Sung in close succession, the initial consonants lend a forward impulse to the musical progression. While these sounds would be recognised as part of a khayāl syllabary, the morphing phonetic string that VR sings after reaching tār Sā, ‘(m)a(v)e(m)a(d)uā—’, is more idiosyncratic, as are the succeeding sequences, ‘E—he—(n)ā—’ and ‘Ā—(h)e—he-e-e—’. What is the intent here? We might surmise that, in the imaginative spirit of khayāl, VR is pushing a little beyond the orthodox syllabary in order to intensify a peak expressive moment in a rāg associated with the karuṇ ras, whose qualities are pathos, sadness and compassion. He brings emotional expression to the brink of actual words, but holds back from crossing the boundary, as this would destroy the very effect of yearning for the ineffable that is so essential here.

But, in any case, who decides what is or is not permissible? The question of who or what determines orthodoxy for ālāp syllables in khayāl remains moot. Historical writings offer some guidance, though the lessons may be equivocal. For example, Hakim Karam Imām’s treatise of 1856–7, Ma’adan ul-musīqī, lays down a distinct orthodoxy about which syllables may or may not be used in an ālāp, and in what combinations (Imām 1959: 11–13; for a commentary on the socio-historical significance of this work see Qureshi 2001: 324–35). Imām roots his maxims in mythological prehistory, invoking ‘Mahadeo’ (Śiva) and ‘the inhabitants of the Nether world’ as the source of the originating syllables ‘ā’, ‘nā’, ‘tā’ and ‘rā’ (Imām 1959: 11–12). But his authority for how this syllabary can be extended (to include, for example, ‘re’, ‘nām’, ‘tom’), and its elements combined into bols (such as ‘ta-nā’, ‘ni-rī’), comes from the historically sanctioned practice of the kalāvants—elite singers whose pedigree goes back to the court of Akbar the Great (r. 1556–1605). Yet Imām is here discussing the kalāvants as exponents of dhrupad, not khayāl; conversely, he tells us that the qavvāls, among whom ‘the singing of Khayal has been prevalent’, ‘do not have Alap. Instead they begin with words of Tarana’ (ibid: 11).

On the one hand, then, Imām’s rubrics would seem not to bear on present-day khayāl practice, since contemporary khayāliyās indeed do sing ālāps, unlike their qavvāl forebears, but in a different way from dhrupadiyās/kalāvants. On the other hand, a comparison between the syllables sanctioned by Imām and those used by present-day khayāliyās reveals some overlaps and connections. So it is worth considering the extent to which the non-lexical syllabaries of tarānā and dhrupad bear on khayāl—even if indirectly—given that these remain current in Hindustani music.

Tarānā syllables are familiar to most khayāl singers because this genre remains part of khayāl practice—a tarānā would optionally be sung at the end of a rāg performance as a virtuosic follow-on (or alternative) to a choṭā khayāl. The syllables used—such as ‘tā’, ‘nā’, ‘de’, ‘re’, ‘dim’, ‘nūm’—facilitate rapid vocal articulation and lively cross-rhythmic play (laykārī). They are believed to have their origins in the Persian language—which would be consistent with the cultivation of this form by the Sufi qavvāls. Complementing this, the syllabary of dhrupad, often termed nom tom, is held to have its roots in Hindu mantras, quintessentially ‘oṃ ananta nārāyaṇa hari oṃ’, from which syllables such as ‘ā’, ‘nā’, ‘ta’, ‘ra’, ‘rī’ and ‘nūm’ are argued to be derived (Sanyal and Widdess 2004: 156–7). Such syllables, along with related ones such as ‘te’ and ‘tūm’, are key to the life force of dhrupad ālāp—appropriately also known as nom tom ālāp.

While in both tarānā and nom tom ālāp, syllables can be permutated in many ways, there are also implicit conventions governing their combination. This takes us back to the orthodoxy reinforced by Imām, even though he gives no systematic rationale for which combinations are desirable and which are circumscribed. By contrast, Sanyal and Widdess (2004: 154–6) successfully sketch out an explicit syntax for the combination and ordering of dhrupad syllables, even though the authors acknowledge that their formula may not be rigorously followed in practice; and Widdess develops some of these ideas further in a subsequent analysis (2022).

All this sheds light on khayāl. On the one hand, most syllables used in a khayāl ālāp can also be found in the syllabaries of dhrupad, tarānā, or both (given that there are some overlaps). The fact that syllables such as ‘do’, ‘mī’ or ‘to’ would sound eccentric in a khayāl ālāp is probably related to the fact that they would not be sanctioned in dhrupad or tarānā either. For khayāl singers, then, these genres—with which most are familiar—might act as an unconscious regulating presence in the background. And, for some, their influence might be more conscious. When I discussed this matter with VR, he confirmed that dhrupad is a subtle influence on his ālāp style, and reminded me that he had spent several months learning dhrupad with Ustād Wasifuddin Dagar; indeed, his own guruji Pandit Bhimsen Joshi (1922–2011), also studied dhrupad. When singing an ālāp, VR told me, he holds the mantra (or its devotional spirit) in his head as would a dhrupad singer, even though he may not literally be voicing its syllables.

On the other hand, part of what characterises the use of syllables in khayāl ālāp is its self-differentiation from those other genres. For one thing, not all their syllables seem equally available—VR once reprimanded me for using ‘te’, presumably because it too strongly connotes dhrupad. But it is also a question of delivery style: not at all like tārānā, with its rapid-fire syllables that fully engage with tāl, and different too from dhrupad ālāp, which is considerably less melismatic than its khayāl relative. In khayāl the enunciation of syllables may be fuzzy, and the rules for how they go together are most definitely so, compared with the quasi-syntactic constraints that Sanyal and Widdess identify for dhrupad. Even so, there are implicit understandings of appropriateness that are more elusive to define—more of an ethos than a syntax. In sketching some of these conventions below, I return from theory to practice, and to a more specific response to a student’s question, ‘What syllables should I sing, and when?’

- Vowels such as ‘ā’ and ‘e’ are commonly sung; ‘ī’ is also possible, though less frequent.

- These can also be sung with an initial consonant, giving options such ‘nā’ and ‘re’ (more common), and ‘de’ and ‘rī’ (less common, but still appropriate); this helps focus tuning, and perhaps also alludes to more formalised syllabaries, such as that of dhrupad.

- Syllable choice may be conditioned by register. Hence ‘ā’ and ‘nā’ tend to be more congenial to the lower register, ‘e’ to the middle, ‘ī’ to the higher; but this is not to say that any of these syllables cannot be used in other registers.

- Carefully measured variety among syllables can help underscore the flow and direction of melodic invention; but don’t have too big a selection at any one time—it is undesirable to draw attention to the syllables themselves.

- Rarer syllables should be used sparingly and in strategic places. For example, ‘nū’ might best be used at or towards the end of a phrase to indicate closure (as would be the case with ‘nūm’ in dhrupad).

As our brief look at VR’s ālāp renditions has shown, much is also dependent on the expressive context—this is khayāl after all, a genre noted for its range of expression and creative imagination. For example, when singing tār Sā, ‘rī’ is a congenial syllable, since it focuses svar, constrains the airflow, and hence can be sustained for a long time; on the other hand, the same note can be sung in full chest voice to a syllable such as ‘nā’ if a certain robustness is appropriate—as in VR’s Bhairav ālāp. What seems particularly important to his gāyakī—no doubt an aspect of his grounding in the Kirānā gharānā and his affinities for dhrupad—is the intimate connection between syllable and svar. On any given svar, changing the syllable will change its formant—the relative strength of overtones within the note, and hence its tone colour. This perhaps explains VR’s calculated penchant for morphing vowels and blurring syllables.

Thus, the salience of a particular note within a rāg, the expressive connotations of ras, and the colouring one accordingly seeks to give it, can all be affected by the syllable chosen. This is not to say that these things are invariably consciously calculated—more probably they are imbibed through an intuitive absorption of style. Compared with dhrupad and tarānā, the syllabary of a khayāl ālāp is more open, flexible, and personal. While some artists and gharānās may choose to keep to a circumscribed syllable set, we have seen that, for VR, a measure of play within this parameter is part of the rich expressive world afforded by khayāl.

Conclusion

The preceding explorations have examined some key principles that bear on how one sings an ālāp. In the process I have sought also to illuminate VR’s ālāp renditions on Rāg samay cakra, and to illustrate aspects of his gāyakī. Throughout, I have allowed a tension to play out between providing pragmatic rubrics for practice and developing these into a theory of ālāp in its own right. To that extent I have allowed my text somewhat to exceed what would have been strictly necessary for a purely practical primer.

The tendency to theorise here is no doubt a response to the far-reaching nature of ālāp in Indian classical music; ālāp carries with itself a complex story that asks to be told. But what is also at the heart of the matter, is the way a beautiful, or touching, or searching ālāp may exceed or qualify any theoretical rubrics that can be written for it. This is not to dismiss the role of theory—whose own essence is a kind of reflection and exploration (not unlike an ālāp). But it is to note that theory and practice are rightly not identical—a point honoured in the śāstras, which sought to codify and recount past practices while also acknowledging their evolution in the present. Theory—whether communicated orally or set down in practice—will always try to capture the riches of practice and pass these on to future generations. Practice will always pull at the moorings of theory, and sometimes slip them, especially if your search is to touch the divine. Perhaps the orally transmitted and improvised nature of rāg music makes any kind of comprehensive theory of ālāp fundamentally impossible. Any claim that the rubrics I have tried to draw out here might make to universality is countervailed by a practice that nudges all such formulations towards the status of heuristics—of rules of thumb.

VR draws attention to a strongly pragmatic and contingent dimension to performing an ālāp, when he says, ‘everything affects your ālāp, not just the rāg, but the composition that follows it, the accompanists, the audience, the room you’re singing in, your mood’. These things would have had an impact on the performances recorded on Rāg samay cakra, involving particular people, in a particular place, on a particular day. Nonetheless, what we have been able to explore through that album is something that also exceeds those contingencies. Its ālāps connect with those performed by countless other musicians, and, as we have glimpsed, have resonances with treatises going back through a long and rich history. My hope is to have conveyed from the intense specifics of the performed moment something of that bigger picture and abundant culture.