4. EXPLORATIONS AND ANALYSES (II): TWILIGHT RĀGS FROM NORTH INDIA

©2024 David Clarke, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0313.04

Performers:

Dr Vijay Rajput (khayāl vocalist)

with

Ustād Shahbaz Hussain (tabla)

Ustād Fida Hussain (harmonium)

4.1 Introduction

In contrast to Rāg samay cakra, an album comprising concise renditions of fourteen rāgs in an extended sequence, Twilight Rāgs from North India presents extended accounts of just two rāgs, Bhairav and Yaman. These concert-length performances by Vijay Rajput (henceforth VR) and accompanists exemplify the wider and deeper reaches of rāg music. Each begins with an ālāp, followed by a weighty baṛā khayāl (also termed vilambit khayāl) and a fully developed choṭā khayāl (also termed drut khayāl). This form of rāg performance launches many a modern-day classical Hindustani vocal recital, after which the soloist usually moves on to shorter and lighter items, including some in semi-classical vein, such as bhajans and ṭhumrīs, or sometimes even folk- and filmi-derived songs.

Two factors drew us towards Bhairav and Yaman. First, bearing in mind the theme of our anthology, these rāgs mark especially evocative performing times (samay). They are associated with the awakening and ending of the day respectively—just after sunrise and just after sunset: times of stillness conducive to contemplation. Second, the rāgs have a core place in the Hindustani canon. They are usually learnt early in a student’s training, and remain touchstones throughout an artist’s career. This is especially true of Yaman—often the first rāg a student might learn, yet not disdained by the great artists either. VR tells of how his late guruji, the feted Bhimsen Joshi (1922–2011), never stopped exploring this rāg; he was especially fond of the drut bandiś ‘Śyām bajāi’, which VR sings as a tribute on both albums of Rāgs Around the Clock.

As the specifications and descriptions for Bhairav and Yaman were outlined in the supporting materials for Rāg samay cakra (Section 2.5.1 and Section 2.5.9), there is no need to repeat that content here. Rather, this part of Rāgs Around the Clock has two main objectives. First, Section 4.2 provides notations, transliterations, translations and commentaries relating to VR’s Bhairav performance on Tracks 2 and 3. Second, Section 4.3 examines the principles of a baṛā khayāl, taking VR’s Yaman rendering on Track 5 as a case study; this complements (and completes) the analysis initiated in Part 3, which looked at the ālāp and choṭā khayāl stages of performances from Rāg samay cakra.

Twilight Rāgs from North India was recorded at Newcastle University in April 2006 and released the same year in CD format (with slightly different orthography in the title). The sound engineer was John Ayers, and David Clarke (henceforth DC) was the producer. Work published elsewhere (Clarke 2013) provides contextual background to the album.

4.2 Rāg Bhairav: Texts, Notations and Commentaries

Aims

The subject under the spotlight in the present section is VR’s performance of the first rāg on the Twilight Rāgs album, Bhairav. One priority is to provide details of the texts and notations of the bandiśes, in the interests not least of students who want to add them to their repertoire. A further aim is to consider the issues raised by these materials and their associated performances. Hence, in the first part of this section, I consider the mutable identity of the baṛā khayāl bandiś ‘Balamavā more saīyā̃’, alongside alternative versions sung by doyens of the Kirānā gharānā. And, in the second part, I analyse the subtleties of the drut bandiś ‘Suno to sakhī batiyā’, and the ways in which VR works it into an extended choṭā khayāl. With this last analysis, I conjecture further about the possibility of an underlying performance grammar, as first raised in Section 3.3. As I have already considered general principles of ālāp in Section 3.1, I will not discuss that stage of VR’s performance here (for an analysis of his Yaman ālāp from the album, see Clarke 2017).

Baṛā Khayāl: ‘Bālamavā more saīyā̃’

Characteristically, VR chooses a baṛā khayāl in vilambit (slow) ektāl for his performance. The text of the Bhairav composition, given below, is characteristically ambiguous as to whether the object of the lyricist’s longing and devotion is earthly or divine, or both:

Rāg Bhairav—Baṛā Khayāl

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Bālamavā more saīyā̃ sadā raṅgīle. |

|

|

Antarā |

|

|

Hū̃ to tuma bīna, tarasa gaai, |

Without you, I have been pining. |

|

Darasa bega dīkhāo. |

Quickly, show yourself. |

राग भैरव—बड़ा ख़याल

स्थाई

बालमवा मोरे सईयाँ सदा रंगीले |

अंतरा

हुँ तो तुम बीन, तरस गऐ

दरस बेग दीखाओ ||

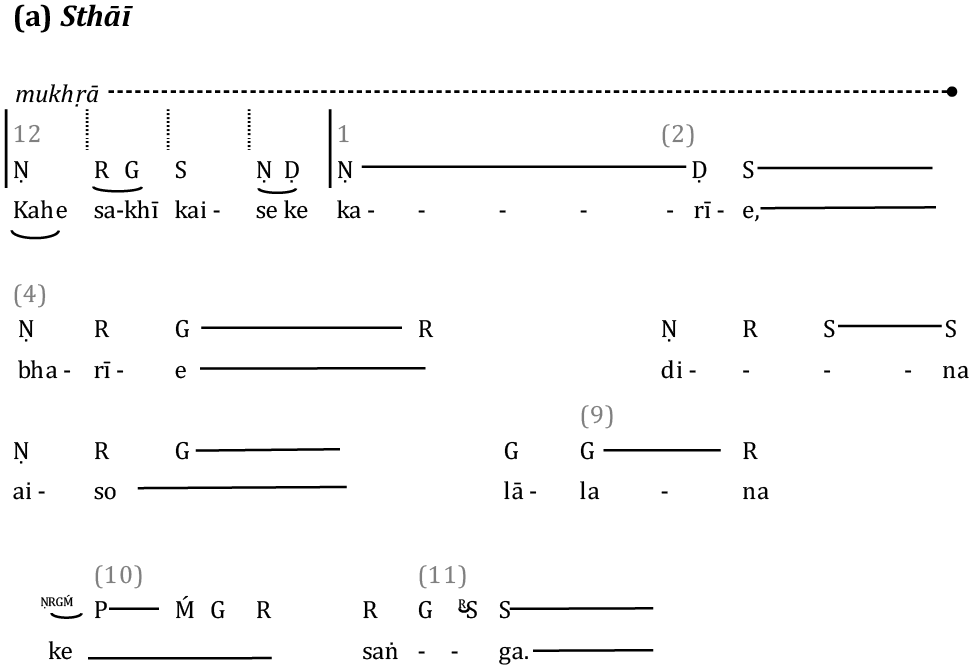

Audio Examples 4.2.1 and 4.2.2 extract the sthāī and antarā respectively from VR’s performance on Track 2 of the album; typically, the former is heard at the very outset, while the latter comes some way in, around 11:20. These extracts can be followed in conjunction with their respective musical transcriptions in Figure 4.2.1 (a) and (b).

|

Audio Example 4.2.1 Rāg Bhairav: baṛā khayāl, sthāī (TR, Track 2, 00:00–01:09) |

|

Audio Example 4.2.2 Rāg Bhairav: baṛā khayāl, antarā (TR, Track 2, 11:20–12:20) |

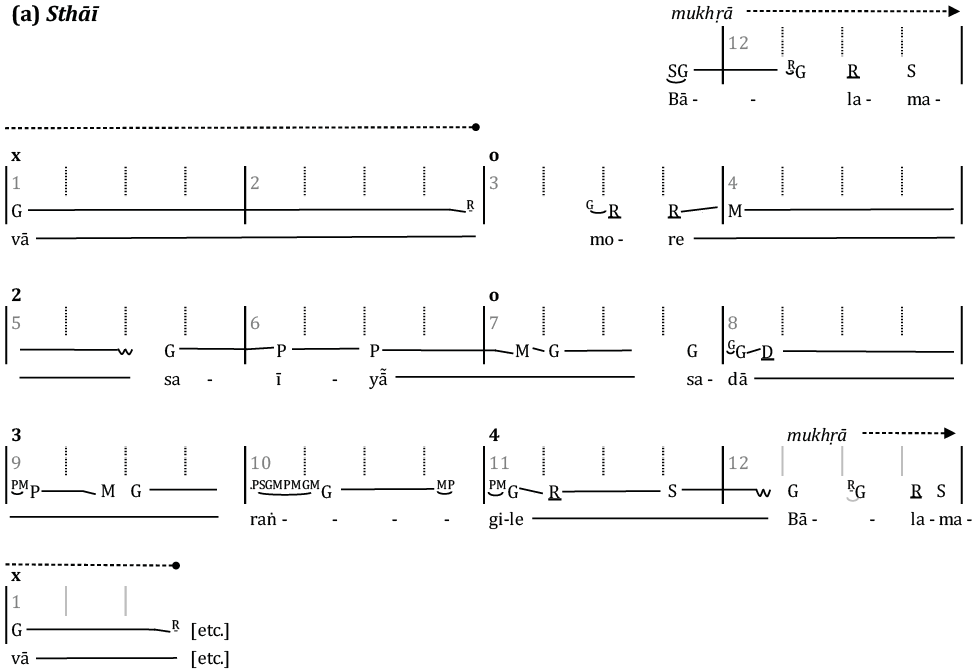

Fig. 4.2.1 Notation of baṛā khayāl, ‘Bālamavā more saīyā̃’: (a) sthāī; (b) antarā. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Notating the composition of a baṛā khayāl has its own complications. This is because the form it takes is closer in style to an ālāp than to the metrically organised song of a choṭā khayāl; it has only a loose connection with the tāl framework. Attempting to set down its somewhat amorphous contours in any definitive notated form runs even more against the grain than is the case with a choṭā khayāl—a matter I explore in greater depth in Section 4.3. In the present notation of VR’s Bhairav bandiś, I have sought to render the composition in a reasonable approximation of how he actually sings it—in Charles Seeger’s (1886–1979) terminology, this would be descriptive music writing (Seeger 1958; see also Section 2.3). Because VR does not overly elaborate the slowly unfolding melodic arc of the composition, or significantly depart from what one might imagine to be its underpinning archetype, this version may also act as a model for emulation by students—in Seeger’s parlance, it also serves as prescriptive music writing. This is provided students bear in mind that, in any actual performance, the timing of notes in relation to each mātrā of the tāl is mutable. Although I have notated the pitches here (as closely as the software permits) in the positions at which VR sings them on this particular occasion, the duration, decoration and location of notes do not have to be—indeed should not be—reproduced exactly this way every time.

Such flexibility can be illustrated by comparing VR’s different executions of the mukhṛā—the head motif that begins the composition and that is used as a refrain throughout the performance. Notionally, the beginning of this figure (‘bālama-’) should fit within the final beat (beat 12)—of the slow ektāl cycle, more or less locking on to its four sub-beats; the final syllable, ‘-vā’ lands on sam and extends some way into the beginning of the first complete āvartan. But Figure 4.2.1(a) shows how VR already allows himself some metrical leeway, extending the initial prolonged Ga by a beat, so that the whole figure lasts five sub-beats rather than four. Conversely, when he reiterates the mukhṛā at the end of the sthāī (bottom of Figure 4.2.1(a)), he begins it later in beat 12, compressing it into three sub-beats and holding the final Ga on the following sam for a shorter duration than before. Further variations can be heard at the end of every āvartan; one such is notated near the end of Figure 4.2.1(b), where, after completing the antarā, VR further compresses the mukhṛā into the last two sub-beats of the cycle.

The indeterminate identity of a baṛā khayāl bandiś means not only that an artist might subtly vary it each time they perform it, but also that even greater differences occur between artists. Interestingly, on commercially released performances of ‘Bālamavā more saīyā̃’ by Bhimsen Joshi (2016) and Gangubai Hangal (1994), the sthāī is so different from VR’s version that it could be regarded as a different composition, even though the text is essentially the same. Most saliently, the mukhṛā in their versions establishes an altogether different trajectory, taking Dha as the initial goal tone—as shown in Figure 4.2.2 which notates the first three phrases of Gangubai’s account. The prominence of Dha reflects the saṃvādī status of this pitch in Bhairav; and I will call this the ‘dhaivat version’ of the song. (The salience of Ma at the beginning or ends of phrases here is another characteristic of Bhairav, and another point of contrast between this version and the one sung by VR.) Bhimsen Joshi sings the dhaivat version a little differently from Gangubai—most notably his rendition is in vilambit tīntāl while hers is in vilambit ektāl—but the same underlying bandiś is discernible behind both performances. Given that both artists belonged to the same branch of the Kirānā gharānā—both were disciples of Sawai Gandharva—we might infer a single line of transmission.

Fig. 4.2.2 Opening of ‘Bālamavā more saīyā̃’, as performed by Gangubai Hangal (1994: Track 1). Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

I have referenced commercially available CDs here, but of course these recordings can also be found in online uploads on streaming platforms such as YouTube by using the artist, rāg or bandiś name as search terms. Searches also throw up yet further variants of the dhaivat version—not only by the same artists, but also by singers of younger generations, such as Manali Bose and Richa Shukla. This suggests the continuing transmission of the dhaivat version, and possibly its emerging status as the canonical melody for this text.

Yet the version sung by VR on Twilight Rāgs—which we can term the ‘gāndhār

version’, because Ga is the salient pitch of its mukhṛā—can also be found

with a little assiduous online searching. Two different performances by Bhimsen

Joshi are captured on YouTube (Sangeetveda1 2017: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p18MARsM92g and Nadkarni 2022: https://youtu.be/gXT3VEKCZRk).

As would be expected, there are differences of contour, pace, melodic segmentation and text underlay between Joshi’s version and VR’s; but they are recognisably the same bandiś, with the foregrounding of Ga in the mukhṛā as a salient shared feature. The very sweetness of Ga brings out the romantic aspect of the text, as compared with the gravity of the dhaivat version, which foregrounds Dha; we might interpret the gāndhār version as invoking the śr̥ṅgār ras, and the dhaivat version the karuṇ ras. Across the spectrum of recordings available both commercially and online, the contrast is greatest between VR’s rendering of the gāndhār version—the heartfelt performance of a younger man—and Gangubai’s more austere performances of the dhaivat version—documents of a much later stage in an artist’s life. I make this point not to set these very different accounts in opposition, but rather to point to how they reveal complementary aspects of the rāg, its sheer range of expressive possibility. This also underscores the importance of the Twilight Rāgs recording as a dissemination channel for the rarer, gāndhār version of the bandiś, and of VR as one of its bearers within the Kirānā gharānā.

Drut khayāl: ‘Suno to sakhī batiyā’

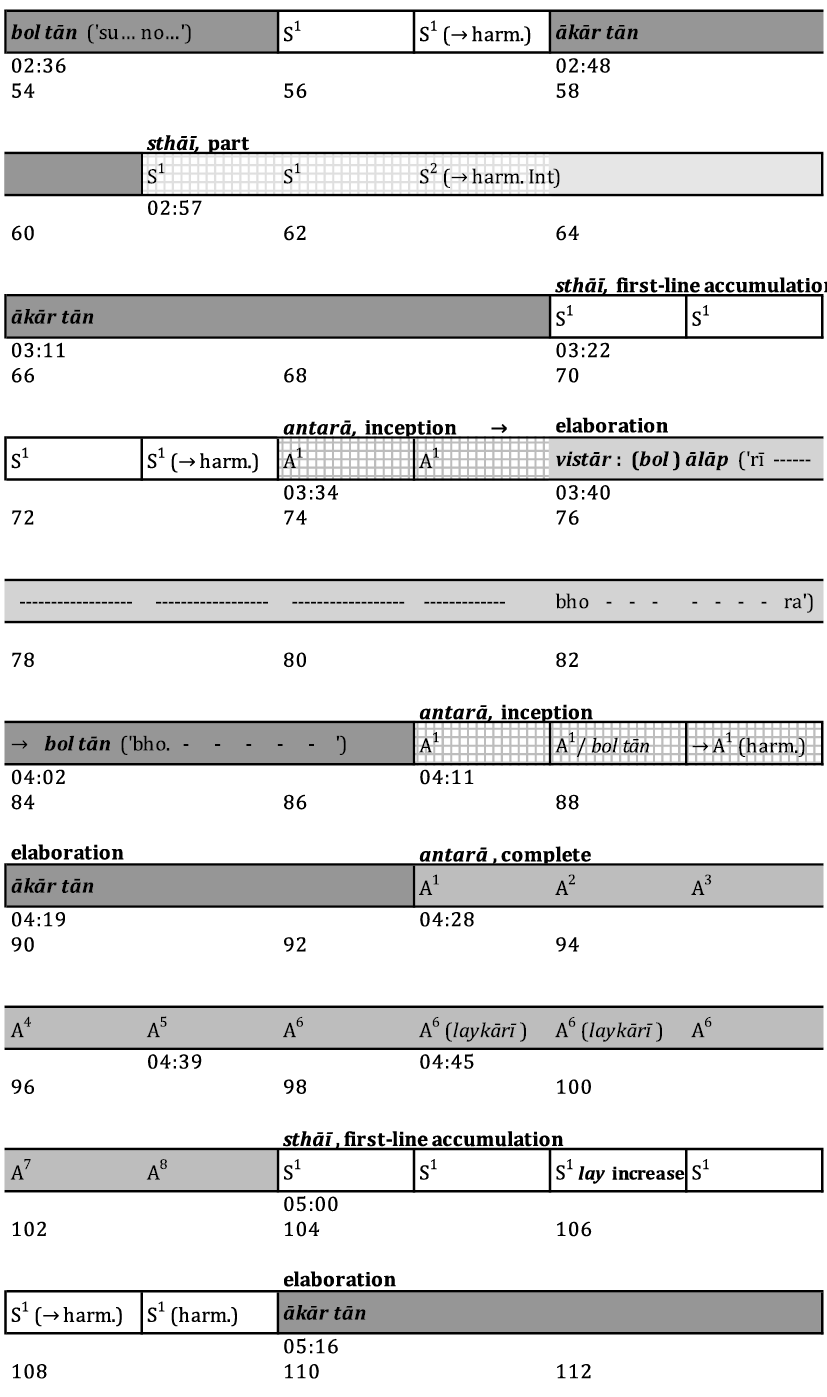

On Track 3 of Twilight Rāgs, we have a quintessential example of a khayāl in drut ektāl. This rapid twelve-beat cycle has a distinctive momentum, owing to successive stresses (tālī) on its last two metrical subdivisions (vibhāgs), which drive towards sam. This particular drut khayāl is based on a fine bandiś in Rāg Bhairav taught to VR by Pandit Madhup Mudgal at the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in New Delhi. The text is given below in the original language and in translation, and its musical setting is notated in Figure 4.2.3. Audio Examples 4.2.3 and 4.2.4 extract the sthāī and antarā from VR’s performance.

Rāg Bhairav—Drut Khayāl

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Suno to sakhī batiyā Ghanaśyāma kī rī |

Listen, my companion, to words about Ghanaśyāma [Kr̥ṣṇa]. |

|

bīta gaī sagarī raina |

The whole night has passed, |

|

kala nā parata āve caina |

I have no repose, no peace of mind. |

|

sudha nā līnī āna kachu dhāma kī rī. |

You did not remember the place, and did not come at all. |

|

Antarā |

|

|

Bhora bhaī mere āe |

Dawn has come, and you have come to me, |

|

pāga peca laṭapaṭāai |

Your curly hair all dishevelled, |

|

atahī alasāne naina |

Your eyes all bleary— |

|

tadarā mukha veta naina |

Your eyes evasive. |

|

bāta karata mukha rijhāta |

As you talk, your face is alight |

|

pagavā dharata ḍagamagāta |

But you can’t walk straight. |

|

juṭhī sau nā khāta dilā Rām kī rī. |

Don’t swear vainly on the name of Rām. |

राग भैरव—द्रुत ख़याल

स्थाई

सुनो तो सखी बतिया घनश्याम की री

बीत गई सगरी रैन

कल ना परत आवे चैन

सुध ना लीनी आन कछु धाम की री।

अंतरा

भोर भई मेरे आए

पाग पेच लटपटाऐ

अतही अलसाने नैन

तदरा मुख वेत नैन

बात करत मुख रिझात

पगवा धरत डगमगात

जुठी सौ ना खात दिला राम की री॥

|

Audio Example 4.2.3 Rāg Bhairav: drut khayāl, sthāī (TR, Track 3, 00:41–01:09) |

|

Audio Example 4.2.4 Rāg Bhairav: drut khayāl, antarā (TR, Track 3, 04:26–05:03) |

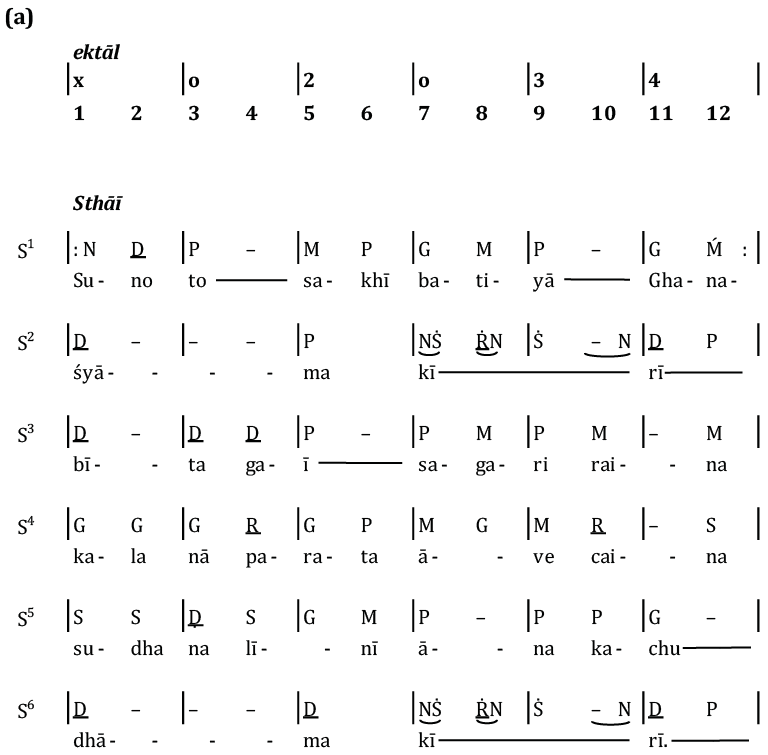

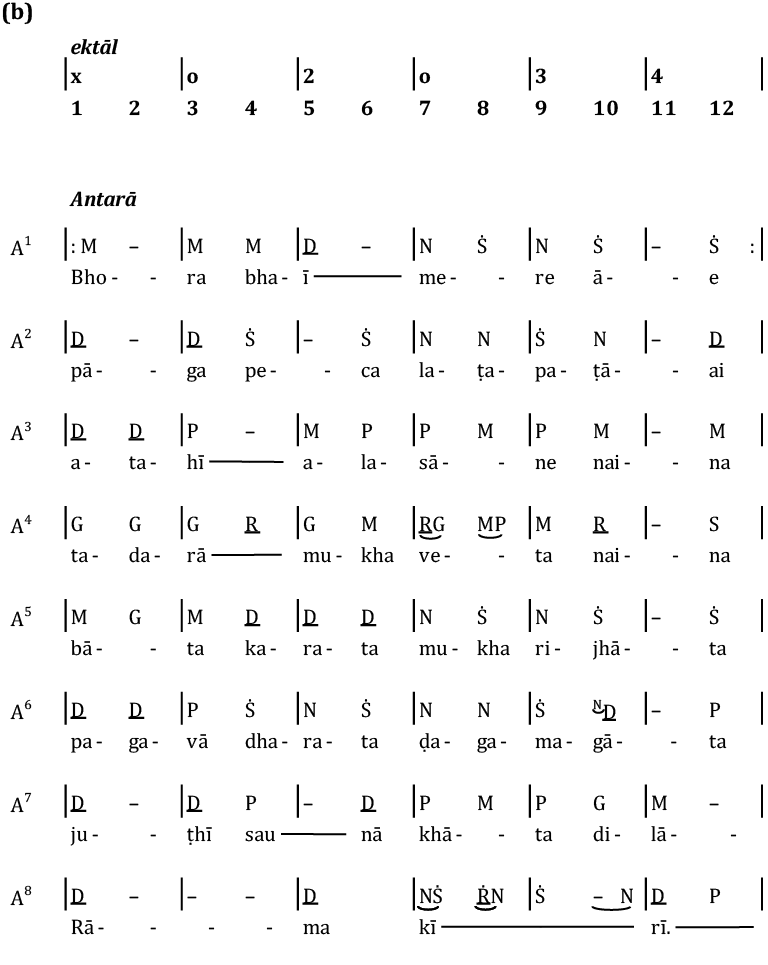

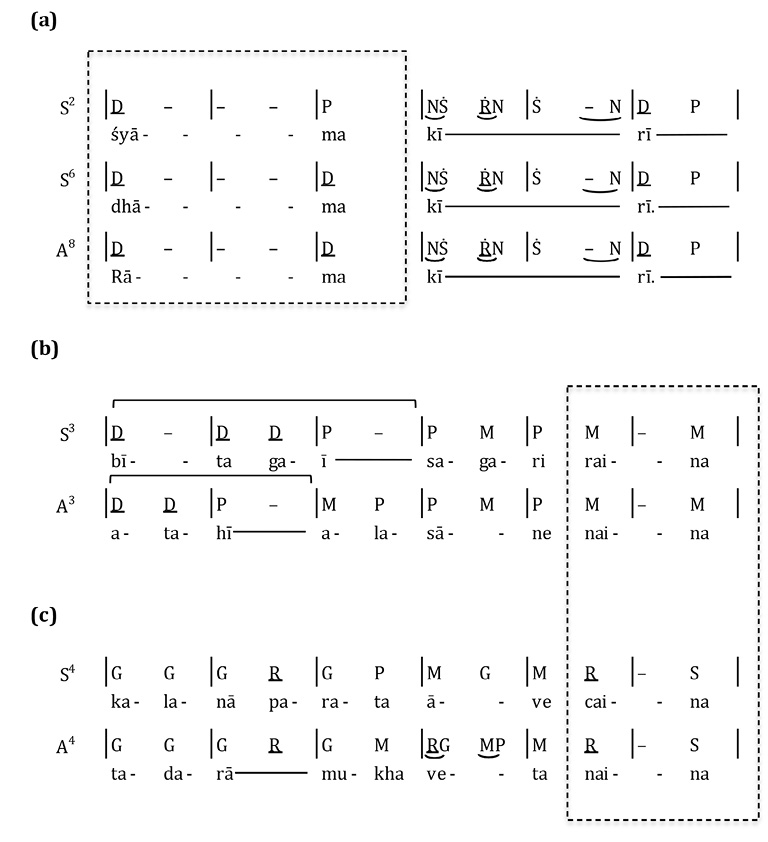

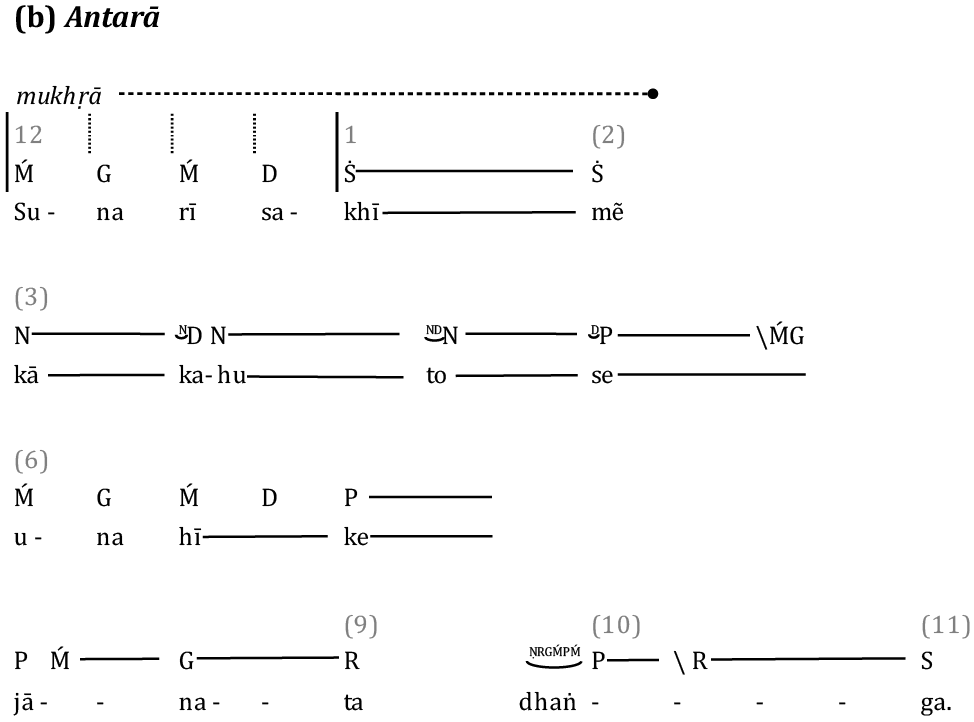

Fig. 4.2.3 Notation of drut khayāl, ‘Suno to sakhī batiyā’: (a) sthāī; (b) antarā. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

What is immediately apparent in all these forms of capture, is that this is a long bandiś. The sthāī and antarā respectively comprise six and eight phrases, each phrase lasting one āvartan—numbered S1, S2 etc., A1, A2 etc. in Figure 4.2.3; interestingly, the antarā in effect has two strophes, the second beginning at ‘bāga karata’ (phrase A5). In a spontaneous moment, VR sings the sixth phrase (‘pagavā dharata’) four times, enhancing it with lāykārī.

The text tells yet another tale of the gopī (cowherd) Rādhā being stood up by her divine lover, Kr̥ṣṇa. She recounts to her companion (rī) how she spent the whole night waiting for him; how she said to him when he finally appeared at dawn, your eyes are bleary, your hair’s dishevelled, your footing’s unsteady; don’t take the name of Ram in vain [by lying to me about where you’ve been]. For all that such a scene is a classic trope of khayāl poetics (cf. Magriel and du Perron 2013, I: 139–42), the text does not rely on formulaic Braj Bhāṣā phrases typical of so many bandiśes. Rather, it has its own distinctive language and construction. For one thing, it is underlaid with a metrical sophistication mirrored in the musical setting and amplified by various internal cross-correspondences within the melody. Figure 4.2.4 shows how textual and musical rhyming reinforce each other: (a) between phrases S2, S6 and A8; (b) between S3 and A3; and (c) between S4 and A4; equivalences are shown with a mix of horizontal alignment, boxes and braces.

Fig. 4.2.4 ‘Suno to’: musical and textual rhyme patterns. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

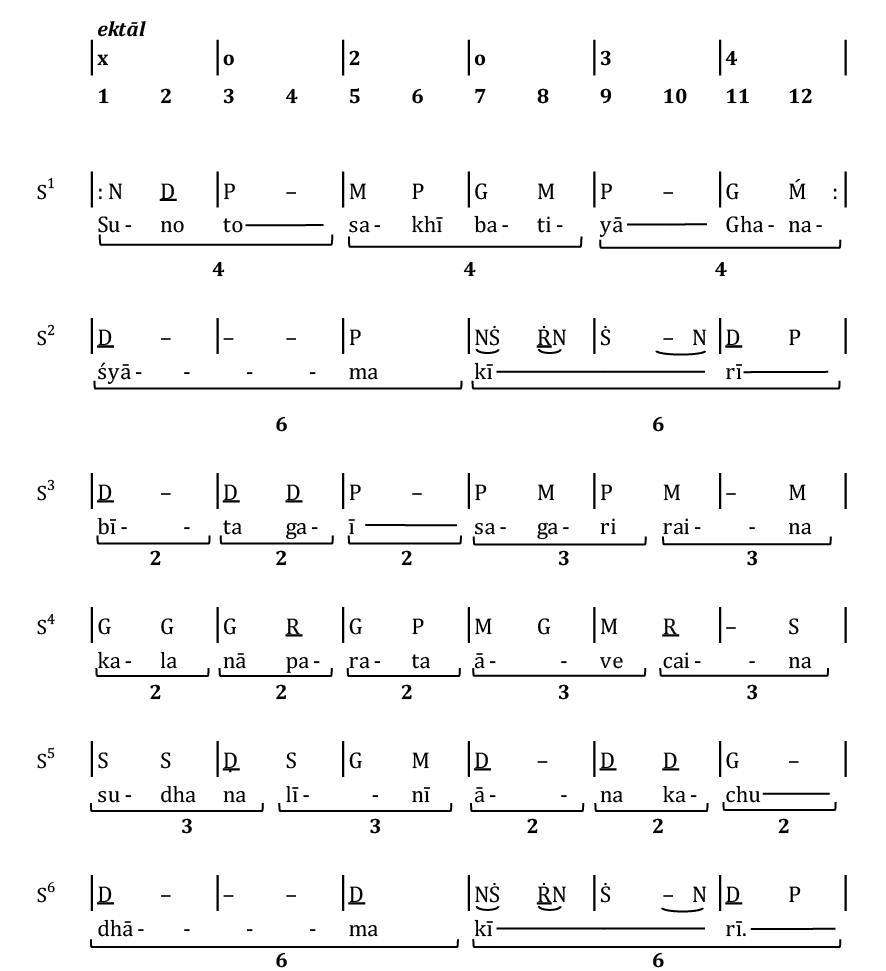

There are further subtleties. Focusing on the sthāī, Figure 4.2.5 illustrates the imaginative ways the metre of the song variably reinforces or counterpoints the metre of the tāl. In S1, the poetic metre divides the twelve beats of ektāl into three groups of four—which is congruent with the tāl’s 6x2-beat clap pattern (shown at the top of the figure). By contrast, in S2 and S6, the main impulses fall on beats 1 and 7, creating two groups of six beats; here the emphasis on beat 7 contradicts the unstressed, second khālī of the tāl cycle. Sometimes complementary groupings take place within an āvartan. In S3 and S4 the beats are arranged in a (2+2+2)+(3+3) pattern; while S5 reverses the grouping to form (3+3)+(2+2+2). These several patterns are generated through their various combinations of melodic and textual stresses and saliences. Their cross-metrical play creates a sense of cut and thrust that conveys the ambivalent feelings recounted in the text, and that imbues the song with life and energy.

Fig. 4.2.5 ‘Suno to’: metrical play. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

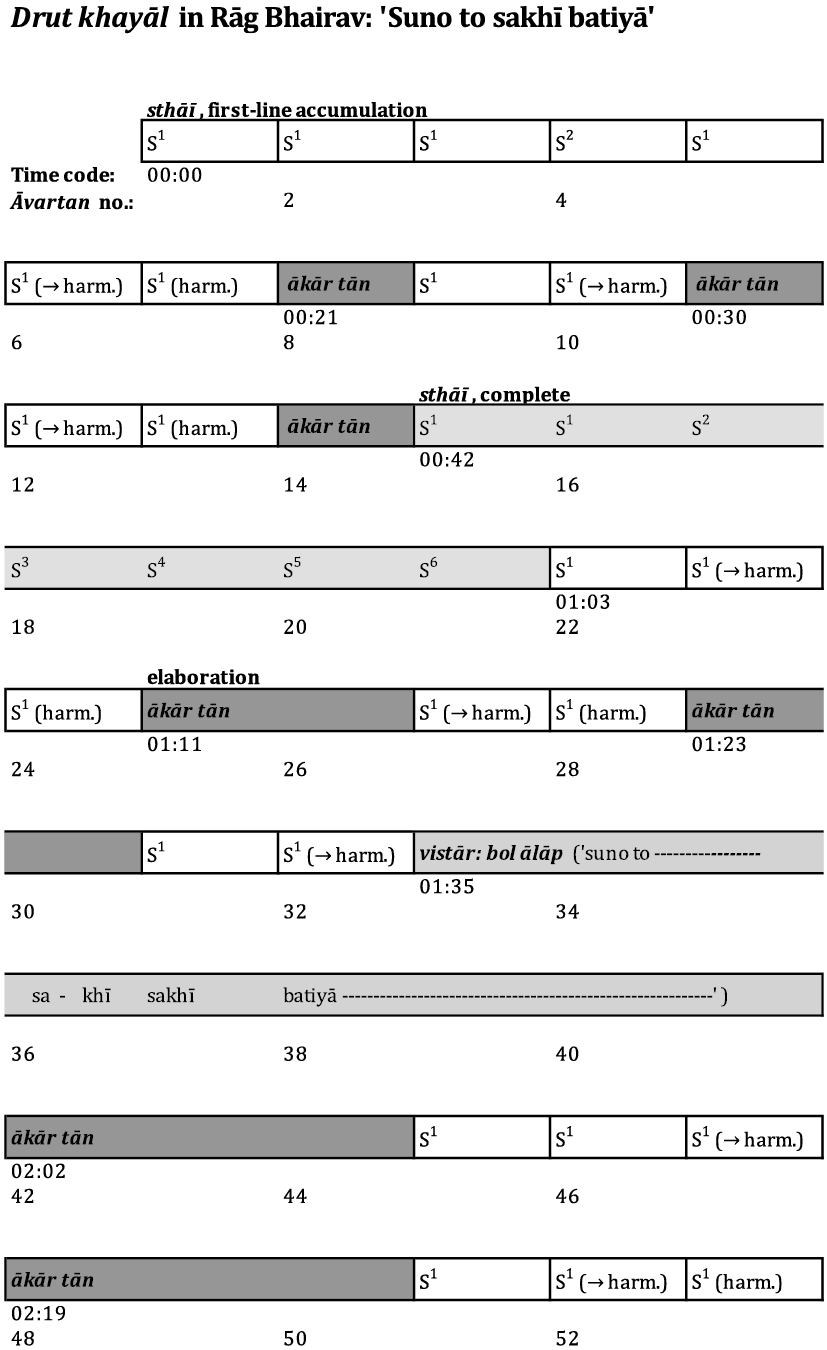

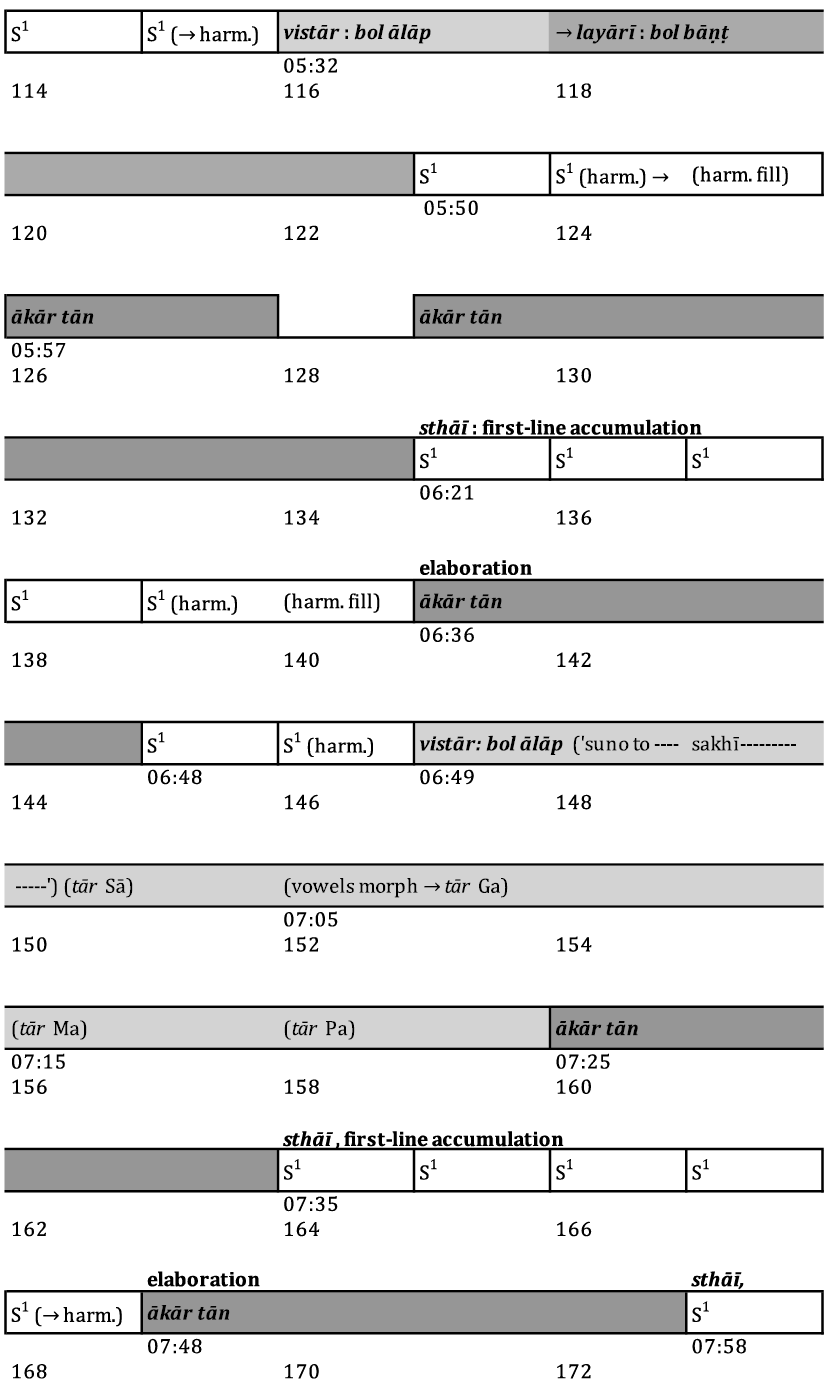

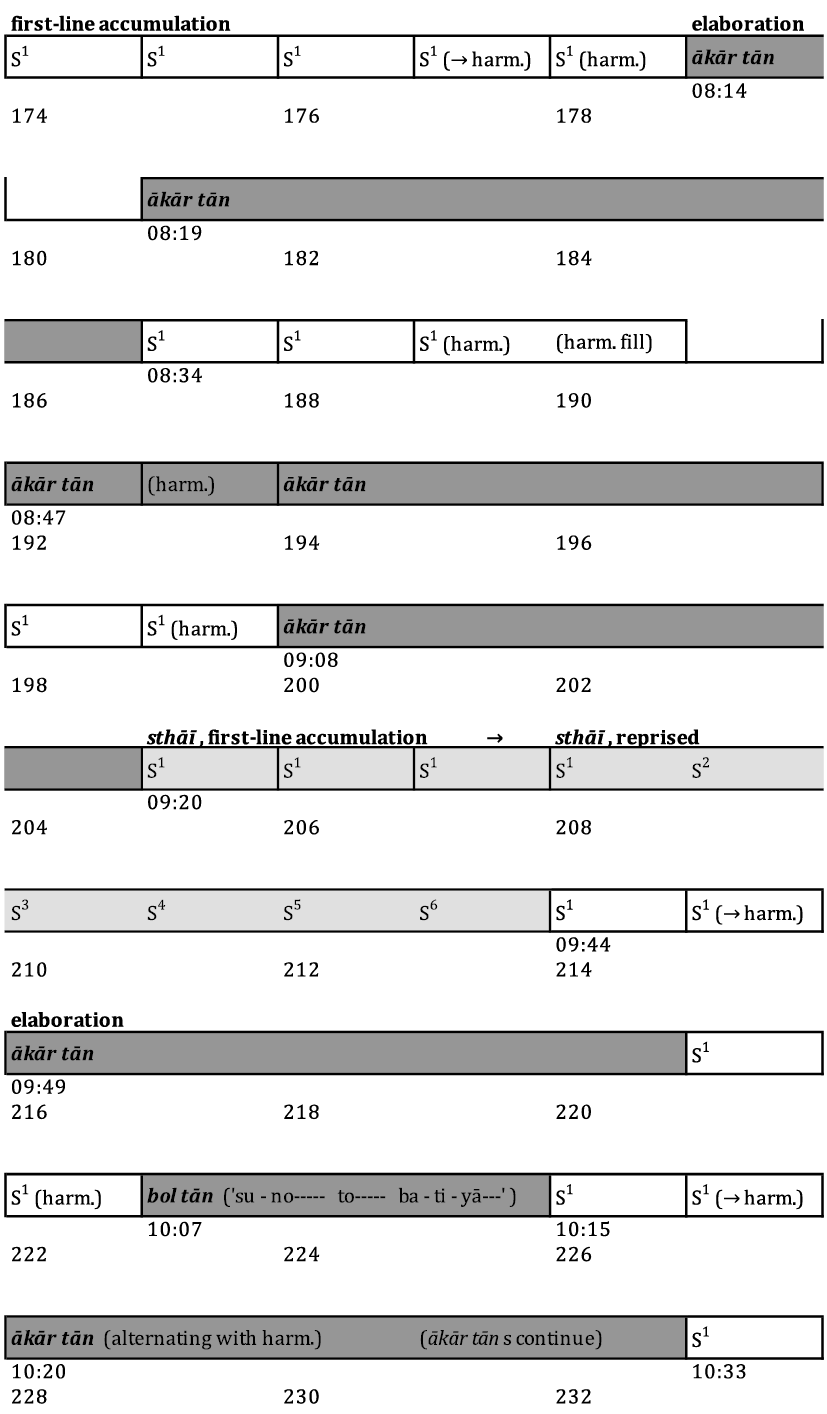

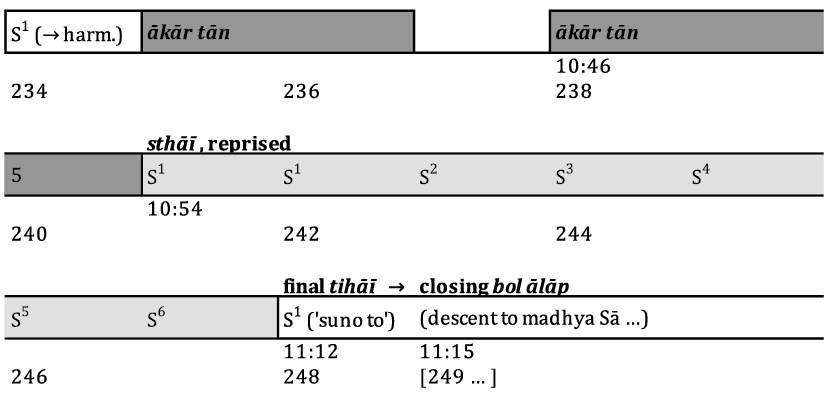

Performing a bandiś stylishly is one thing, but a khayāl singer’s artistry also lies in extemporising around it to create a full-length performance. Always an issue for the improvising soloist—and especially in such a fast lay—is the ever-pressing question of what to do next. Figure 4.2.6 graphically summarises the elaborate chain of events that VR generates in response to this imperative. Shadings highlight the different kinds of materials deployed: the sthāī (in its complete form), the antarā, passages of bol ālāp, and tāns. Unshaded areas principally signify the first line of the sthāī (S1) when sung independently from the whole and functioning as a refrain or mukhṛā; perhaps because of the rapid tempo, this function is often performed by joining statements of S1 in pairs, sometimes in a relay from voice to harmonium. White space also indicates occasional rests and fills. The 248 āvartans of the drut khayāl are numbered underneath each line and are supplemented by time codes cross-referenced to Track 3 of the album. Readers are invited to follow this graphic while listening to the entire track.

Fig. 4.2.6 ‘Suno to’: event sequence in graphical form. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Fig. 4.2.6 (cont'd) ‘Suno to’: event sequence in graphical form. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Fig. 4.2.6 (cont'd) ‘Suno to’: event sequence in graphical form. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Fig. 4.2.6 (cont'd) ‘Suno to’: event sequence in graphical form. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Fig. 4.2.6 (cont'd) ‘Suno to’: event sequence in graphical form. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

What this empirical representation makes clear is that, while statements and repetitions of the first line of the sthāī (S1) are prevalent, accounting for over a quarter of the total performance time, statements of the complete sthāī are rare. It is not heard in full until the fifteenth āvartan, having been deferred by a period of first-line accumulation interjected with tāns; after that it is heard complete only twice more, in the closing stages of the performance at āvartans 205 and 241. Even more selectively, the complete antarā is sung only once, at āvartan 93 (though its inception can be traced back to āvartans 74 and 87). These components of the bandiś, then, function as stand-out moments against the more loosely ordered tān and bol ālāp passages that prevail for so much of the rest of the time.

Tāns in fact represent the predominant means of musical extension. Their virtuosic execution here is appropriate to the climactic drut lay, and no doubt also reflects VR’s predilection for effusive tān singing. As already noted, he interjects them into the drut’s opening period of first-line accumulation—a gesture that would be premature in a freestanding choṭā khayāl, but is fitting following a baṛā khayāl, which has already done much of the exegetical work. In total, tāns—principally ākār tāns—account for about a third of the drut khayāl’s performance time. Like the less-prevalent bol ālāp or vistār passages which complement them, the appearance of these musical gestures feels more contingent and fungible than the nested phrase structure of the sthāī and antarā. To put it technically, their organisation is paratactic—i.e. not dependent on any particular ordering: a tān here could be replaced by a bol ālāp there; either could in principle be longer or shorter, or come earlier or later. This complements the hypotactic organisation of the sthāī and antarā, which convey a strong sense of internalised narrative direction, due not only to the presence of a text, but also to a corresponding musical syntax that organises the succession of their several phrases into a larger, integrated whole.

That a choṭā khayāl, blends hypotactic and paratactic principles is a point I discussed in Section 3.3, where I evaluated the possibility of an actual or virtual grammar underpinning a performer’s choices in the moment. It is worth re-visiting this issue here, for VR’s drut khayāl is a performance both richly spontaneous and subconsciously conditioned by a set of culturally understood conventions. Alongside hypotaxis and parataxis, what further principles might govern the dynamics between the immediate moment and the constantly evolving whole?

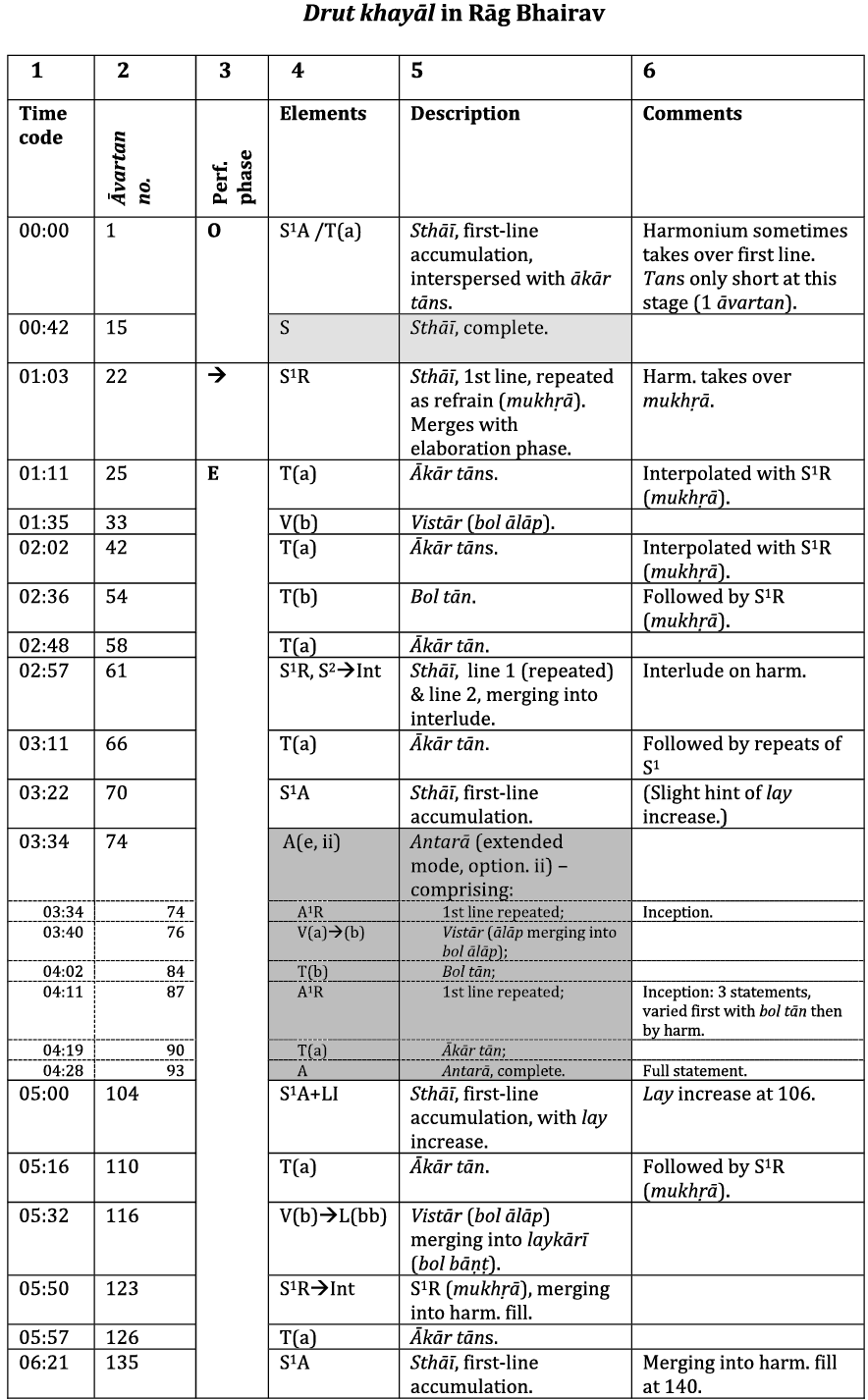

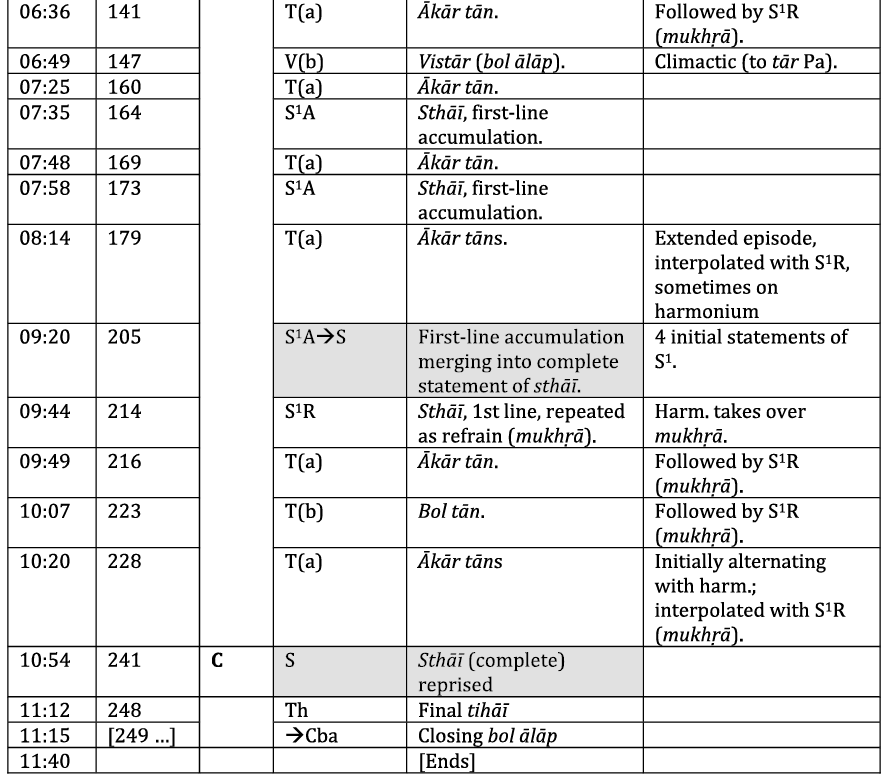

Because any larger organising principle or grammar for extemporisation must by definition exist ex tempore—that is, outside the time of any actual performance that it generates—we will need momentarily to pull back from the empirical surface of the music as graphed in Figure 4.2.6 if we want to define it. To this end, Figure 4.2.7 distils that information into an event synopsis, following the model adopted in Figure 3.3.8 and Figure 3.3.9. In column 4 of this table, each musical element, and its rubric for performance, is encoded with one or more letters, glossed in column 5 (a full schedule of rubrics can be found in Section 3.3); column 6 gives additional information specific to the performance.

Fig. 4.2.7 ‘Suno to’: event synopsis. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Fig. 4.2.7 (cont'd) ‘Suno to’: event synopsis. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Two larger principles of organisation are made legible in this synopsis. First, it conveys the saliency of the complete statements of the sthāī and antarā by carrying over their shading from the previous graphic. The highlighting of the antarā in particular draws attention to its presentation in extended mode, with several subcomponents preceding its complete statement at āvartan 93. Even though those components include such features as bol ālāp and tāns, they are here mobilised hypotactically under the auspices of the antarā itself (they fall within its orbit), and hence are also shaded in the synopsis.

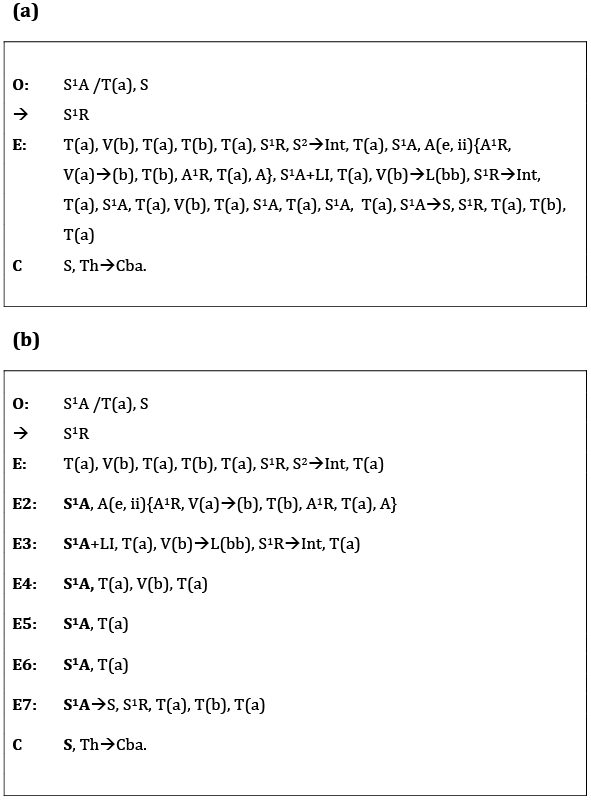

The second organisational principle is shown in column 3, which identifies the different phases of the performance: the opening phase (O), elaboration phase (E), and closing phase (C) (an arrow signifies a transitional overlap between the opening and elaboration phases). In a previous analysis (Figure 3.3.9) we saw how the elaboration phase accounted for by far the greater part of the performance. This is even more true here, where it extends across āvartans 25–240. If we further extract the information from columns 3 and 4 into a linear event string—as in Figure 4.2.8(a)—we are left in no doubt about just how many events are concatenated into the elaboration phase (E). (When listening to the performance in conjunction with this string notation it should be noted that a single symbol such as ‘T(a)’ might signify an entire episode of several ākār tāns, and also imply statements of the mukhṛā (S1) interpolated between them but not separately indicated.)

Fig. 4.2.8 ‘Suno to’: (a) event string; (b) event substrings. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Although the very long event string of the elaboration phase captures the ceaseless experience of ‘keeping going’ typical of a drut khayāl, it does beg the question of whether there might not be divisions or undulations within it that make the performance more than an experience of just one thing after another. In response, Figure 4.2.8(b) surmises a third possible principle of organisation. Here, instances of first-line accumulation of the sthāī (S1A) are posited as salient points of orientation that divide the main event string of the elaboration phase into several substrings, labelled E2–E7. This modelling may to some extent reflect the empirical experience of both performer and listener. Even so, it would be erroneous to regard the substrings as explicitly articulated formal sections like those found in, say, western rondo form.

There are other salient features that additionally mark out waystations in our perception of the larger flow. For example, it could be valuable to integrate the already-noted salience of complete statements of the sthāi and antarā into this picture. To this end, Figure 4.2.9 maps those events onto the previous pattern of substrings by showing them in larger type. The same convention is also applied to the lay increase (LI) that reinforces the first-line accumulation (S1A) at around the half-way point. (For the sake of visual clarity, the figure drops the performance-stage indications.) With its superimposition of several organisational principles, this analysis perhaps represents a closer match between theoretical modelling and the empirical experience of the performance.

Fig. 4.2.9 ‘Suno to’: event substrings/salient moments. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Further to the three organisational principles so far identified, we need to recall a fourth: the principle of accumulating intensity (AI) described under ‘global rubrics’ in Section 3.3. This has an effect on elaborative materials such as tāns, which, across the course of the performance, exhibit a principle of growth. For example, in the opening phase, prior to the first complete statement of the sthāī, the interjected tāns last just one tāl cycle—āvartans 8, 11 and 14; but after this point, they extend to two āvartans (25–6, 29–30), then to three (42–4, 48–50), then to four (66–9, 110–13), and ultimately to six (181–6). Although there are intermittent periods of contraction and expansion within this tendency, the tendency obtains nonetheless. This tells us that even though there is a paratactic dimension to the timing of tāns, they also manifest a discontinuous hypotaxis through this larger cumulative tendency.

Something similar applies to episodes of bol ālāp, of which there are essentially three, beginning at āvartans 33, 76 and 147 (another, at 116, soon mutates into bol bāṇṭ). Across these discontinuous passages, all of which initially focus on tār Sā, we can hear a gradual lifting of the registral ceiling: the first pushes gently upwards to tār Re, the second to tār Ga, and the third to tār Pa. The climactic character of the final episode might also qualify it as an addition to the strongly salient passages of this performance. The staged process of ascent and growth here is another connotation of the term vistār, which is often used (as in this book) as a close synonym for bol ālāp or its wordless counterpart. Vistār, in this guise could be considered a fifth principle of organisation within khayāl.

Additionally, we might introduce a sixth principle. In live performance, decisions about what to do next would also be conditioned by the performer’s judgement of audience response: do they want more; are they getting bored; do they need some contrast? Even a studio performance such as this would involve an internalised imagining of such factors, based on years of live performance experience, as well as actual interaction between lead artist and accompanists.

Collectively, these principles neither conclusively affirm nor definitively refute the operation of a grammatical or syntactic process behind the build-up of a khayāl performance. Instead, in their heterogeneity, they suggest a possible epistemic messiness. However, rather than tidy things up in a quest for some overriding unifying principle (a motive which has driven much western music theory), we might ponder—on this occasion at least—the merits of living with a little chaos. For, in one sense, that is just what the performer has to do. I want to conjecture whether what goes on in their inner experience might not be something like the multiple drafts model of consciousness proposed by Daniel Dennett in his 1991 volume, Consciousness Explained.

Among other things, Dennett relates this notion to the inner logistics of speech production—which, I would suggest, may not be unrelated to the production of musical utterances. To summarise a complicated argument, Dennett dismisses the idea of any unifying centre of consciousness, and, by analogy, of any central ‘meaner’ or any central process of generating meaning when human beings create sentences. His memorable image for speech production is of an inner pandemonium, operating at a pre-conscious level, of ‘word-demons’ and ‘content-demons’ that spontaneously and simultaneously generate bits of vocabulary, morsels of syntax, fragments of sentences, and so on, some of which coagulate and eventually get voiced as meaningful utterances (1991: 237–52). Dennett posits that ‘[f]ully fledged and executed communicative intentions—meanings—could emerge from a quasi-evolutionary process of speech act design that involves the collaboration, partly serial, partly in parallel, of various subsystems none of which is capable on its own of performing—or ordering—a speech act’ (1991: 239). Substitute ‘quasi-evolutionary’ with ‘cultural’, and ‘speech act’ with ‘musical gesture’, and we can see how this could apply to performing khayāl. While for some musicians, ideas may be lining up in their minds in an orderly queue waiting to be executed (I have heard reports of such claims), I suspect that for many others, especially in ati drut lay, looking into their mind would reveal a ferment of vying possibilities—like the following:

now sing a tān / sing the antarā / don’t get too intense yet / keep the audience engaged / go higher in this bol ālāp than the last time / merge this with something else / let the harmonium player take over for a bit / don’t repeat that idea, you sang it a while ago / do it for longer this time / just repeat the first line till something happens / surprise them, break off, go in a different direction / savour this svar / don’t stop yet, let them guess how long …

This is not to say that the singer would be literally thinking these thoughts as such—since the whole process is going on below consciousness and as much in parallel as in succession. Rather, I use these words as a conceit to signify pre-conscious intentions, or what Dennett calls ‘content-demons’: a host of dispositions looking for proto-materials which are similarly looking for desired content. Such materials (which Dennett would call ‘word-demons’, but which we could here term ‘musical ideas’) would include memories of musical materials, figures, shapes, patterns, actions and gestures, stored over years of practice and waiting to be triggered by the content demons—the whole pandemonium a buzz of parallel, emerging, collaborating possibilities some of which will eventually manifest as musical gestures—less through conscious decision-making than through a stacking of the odds according to the accumulating circumstances of any given moment. To adapt Dennett (1991: 238, substituting ‘singer’ for ‘speaker’): ‘In the normal case, the [singer] gets no preview; he and his audience learn what the [singer’s] utterance is at the same time’.

What all this means is that the various organisational principles described and graphed above may all be operating simultaneously in a performance, and that none has any greater privilege over the others as the organising model. It may even mean that the rubrics for musical material and behaviour specified in Section 3.3 might represent the maximum level of formalisation possible for any putative performance grammar. This is not to say that some form, or indeed several forms, of syntax might not be operating, since there is a clear difference between a well-timed, elegantly executed musical gesture and a random-sounding or botched one. Nonetheless, if Dennett is right, it could be that such principles operate in an inner cognitive environment that is not entirely free of chaos. Such speculations about the phenomenology, the lived experience, of a performance are important. They suggest, once again, that the musical event of khayāl is a complex and perhaps not entirely tidy admixture of theoretical rubrics and the material contingencies of a real time and place. The creative aim is to produce neither a great work, nor even an interesting piece, but a compelling, indeed memorable performance: a coming together of people, music and imagination.

4.3 How Do You Sing a Baṛā Khayāl? Performance Conventions, Aesthetics, Temporality

Preamble: Time Is of the Essence

A baṛā khayāl lies at the heart of a full-length khayāl performance. Here is where an artist is able (and expected) most fully to display their artistry—not only their technical prowess, but also their ability to explore the deeper reaches and subtleties of a rāg. Learning how to present a baṛā khayāl is so essential to the khayāl singer’s art that no treatment of Hindustani classical music would be complete without considering it; for audience members too, knowledge of its conventions is invaluable for more rewarding listening.

Paradoxically, while a baṛā khayāl is more expressively searching than its choṭā khayāl counterpart, pathways through it are generally clearer cut, with fewer likely forks in the road and more time to make decisions. Hence, while the inner game of what to sing next remains an issue, my greater concern in this section is with the aesthetic principles of a baṛā khayāl and the way these are implicated in the singer’s shaping of musical time. My case study is taken from Vijay Rajput’s performance of Rāg Yaman on the album Twilight Rāgs from North India. And since I don’t want to exclude feelings, sensations and lived experience from this discussion, readers would be repaid by listening to the recording (Track 5), before going further; those wanting a preliminary thumbnail of performance conventions can consult Section 1.7.

The expressive possibilities of a baṛā khayāl are afforded by its extended duration (‘baṛā’ means ‘large’) and by its spacious tempo (an alternative name is vilambit khayāl, meaning slow khayāl). Time is of the essence here in a different way from how we have so far considered it: while we previously focused on samay, the principle of performing a rāg at its given time, in this essay I consider time as actually experienced through the course of a performance, from the standpoint of both singer and listener. These concerns resonate with Martin Clayton’s book-length study, Time in Indian Music (2000), though my emphases differ; in particular, I will focus on the subtle tension between non-metrical and metrical principles (anibaddh and nibaddh) that permeates a baṛā khayāl—a tension that conditions other experiential aspects of the music, including pedagogy and aesthetics.

Evidence tells us that in the late nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries, vocalists such as Amir Khan (1912–74), influenced by Abdul Wahid Khan (1871–1949) of the Kirānā gharānā, began to perform ever slower and more spacious baṛā khayāls in a quest to broaden expressive horizons (Clayton 2000: 50–1; Deshpande 1987: 64–5; Van der Meer 1980: 61–2). And while artists such as Veena Sahasrabuddhe (1948–2016) counsel that ‘one hears much slower vilambit tempi today than our tradition recommends’ (Clayton and Sahasrabuddhe 1998: 15), it is not uncommon to find ati vilambit (very slow) khayāls being adopted almost as a norm in present-day practice.

Sahasrabuddhe also reminds us that the appropriate tempo is a question of both the temperament of the singer and the character of a bandiś. Some, more lilting baṛā khayāl compositions are best sung in madhya lay spread out over two āvartans. However, in an ati vilambit khayāl (like the one discussed here), the tempo is slow enough to accommodate the bandiś within a single capacious āvartan, and this duration then becomes the basic yardstick for improvisation. The latter vein tends to be the one favoured by many contemporary artists, especially those, such as VR, who belong to the Kirānā gharānā—a stylistic school known for its inclination towards purity of svar rather than its cultivation of lay (see Deshpande 1987: 41–5). It is this baṛā khayāl idiom that I principally discuss here.

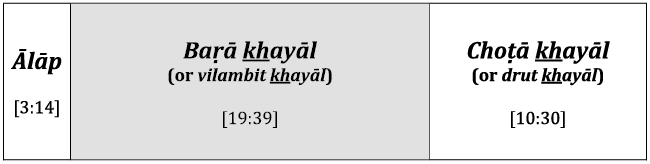

Although a baṛā khayāl does not feature in every rāg performance, when it does, it supplies the expressive centre of gravity, being flanked by a short introductory ālāp and one or more succeeding, brisker choṭā khayāls. Figure 4.3.1 illustrates how VR models his Yaman performance in just this fashion. This graphic (drawn approximately to scale) reveals his baṛā khayāl to be about six times the length of his prefatory ālāp and about twice as long as his final choṭā khayāl.

Fig. 4.3.1 Elements of a typical full-length khayāl performance, with durations from VR’s Yaman recording

(TR, Tracks 4–6). Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

In fact, at just over three minutes, the ālāp here is of relatively generous length. Not uncommonly, ālāps prefacing a baṛā khayāl might not last much more than a minute or two (indeed, the most succinct form of introduction, known as aucār, lasts just a few phrases). The reason for such curtailment is that in the first stage of a baṛā khayāl, the vocalist tends to continue in the unmetred style of an ālāp; hence there is no need to over-extend the ālāp proper, since this would steal the thunder of what follows. Nonetheless, what crucially distinguishes a baṛā khayāl from an actual ālāp is that the former additionally incorporates a slow tāl cycle supplied by the tabla. At the heart of a baṛā khayāl, then, is the simultaneous presence of the non-metrical (anibaddh) principle of ālāp and the metrical (nibaddh) principle of tāl.

Clayton (2000: 51) remarks on how the historical ‘deceleration of the tāl [in a baṛā khayāl], coupled with the expressive and melismatic singing style, broke down the conventional model of rhythmic organization. Indeed the changes brought about were so radical that it is remarkable that this type of music is still performed in tāl’. But another way to consider the situation is to note the scope for creative play that lies in the confluence of anibaddh and nibaddh principles. For much of the time, the vocalist avoids locking on to the mātrās (beats) of the tāl while all the while remaining conscious of it, moving fluidly into and out of metrical synchronisation. In an ati vilambit khayāl each radically expanded mātrā—what I here term a macro-beat—is divided into four sub-beats, made audible by the tabla; so, in vilambit ektāl, used in both baṛā khayāls on our Twilight Rāgs album, the slow twelve-beat cycle can also be heard as a faster-moving forty-eight-beat one. The point is to feel these two metrical levels simultaneously; their co-presence creates depth of field and further space for creative exploration.

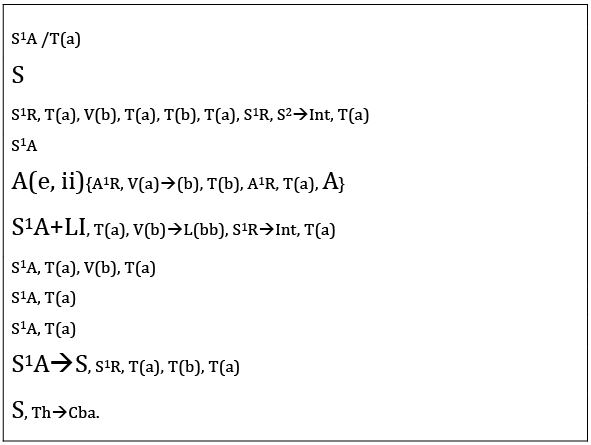

Like much else in Hindustani classical music, a baṛā khayāl is largely improvised, albeit with reference to well-established conventions. Its typical sequence of events is mapped out in Figure 4.3.2 (the graphic again cross-references these to their realisation in VR’s performance, using track time codes). Even so, it does not feel quite appropriate to consider a baṛā khayāl as a ‘form’ and its different stages or phases as ‘sections’—as in, say, western classical sonata form. For those terms carry static, architectural connotations that would belie the felt flow that is of a baṛā khayāl’s essence. To be sure, flow is an aspect of western music (and many other musics) too. But perhaps what makes this Hindustani version of the big musical utterance distinctive has something to do with its non- (or very limited) investment in musical notation. A practitioner of western classical music wanting to perform a sonata, for example, would learn ‘the piece’ from a fully notated score; indeed in western music, pieces of such substance could not have been generated without the technology of writing. Conversely, a practitioner of Hindustani classical music wanting to perform a baṛā khayāl would have nothing more in their mind—rather than on the page—than a version of the event sequence sketched in Figure 4.3.2; a knowledge of stylistic and improvisation conventions based on rāg and tāl; plus a short bandiś (composition) lasting no more than a couple of minutes in a chosen rāg, around which to improvise at length. Here, substance is generated in a different way.

Fig. 4.3.2 Typical event sequence of a baṛā khayāl, with time codes of their occurrence in VR’s Yaman recording

(TR, Track 5). Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

In the ensuing commentary, then, I seek not only to illustrate what happens and in what order (which is certainly important for students and listeners to know), but also to convey the various ways in which a baṛā khayāl’s ambiguous temporality and related interplay between the fixed and the free, the formal and the informal, permeate the performance ethos and contribute to the experience of musical depth. This also relates to the question of how a baṛā khayāl gets taught; as elsewhere in Rāgs Around the Clock, my account here includes insights gleaned directly from learning with my own guruji, VR.

Bandiś: ‘Kahe sakhī kaise ke karīe’

It will repay us to begin our exploration by examining the bandiś VR sings on this recording—‘Kahe sakhī kaise ke karīe’—since this encapsulates many of the essential, ultimately temporal, properties of the entire performance. I will focus on two such properties:

- Resistance to notation as resistance to metre: as the only (relatively) fixed or composed aspect of the musical material, the bandiś is the feature that most invites being set down in musical notation—not least when being transmitted from teacher to student. Yet at the same time (and even more than is the case in a choṭā khayāl), a baṛā khayāl composition will want not to be bound by any notational straitjacket—in the same way that its anibaddh spirit will seek to elude capture by the nibaddh essence of tāl.

- Eventfulness: another characteristic of the bandiś is that its two components, sthāī and antarā, are experienced not just as musical content but as musical events; and this eventfulness is a further dimension of a baṛa khayāl’s temporality, complementing its flux.

Let us now explore each of these properties in turn.

Resisting Notation

Conventionally, the bandiś of a baṛā khayāl is transmitted orally, directly from guru to śiṣyā in the real time of learning, being imitated over and over again by the student until committed to memory. In modern-day practice, however, the process may be a little more complicated, with notation playing at least some kind of role. Even so, the reifying effect of writing—its tendency to turn evanescent invention into a fixed thing—continues to be resisted.

For example, the learning process I have evolved with VR entails writing down only the text of a bandiś, adopting the above-described repetitive procedure for acquiring its melody, and also recording my teacher’s rendition of the composition on my smartphone. I refer to this recording after the lesson in order to consolidate my learning; it provides a virtual version of my guruji continuing the living work of oral transmission. In the spirit of this approach, I supply the text of the Yaman bandiś ‘Kahe sakhī kaise ke karie’ below—in Romanised transliteration, in English translation (by my fellow student, Sudipta Roy), and in Devanāgarī script (as supplied by VR). In the poem, the lyricist speaks to their most intimate confidant (‘sakhī’) of the pain of separation from their lover—a classic trope of khayāl poems (see Section 2.2). The text can be read in conjunction with Audio Examples 4.3.1 and 4.3.2, which extract the sthāī and antarā portions of the bandiś from VR’s performance.

Rāg Yaman—baṛā khayāl

|

Sthāī |

|

|

Kahe sakhī kaise ke karīe |

Dearest friend, what should one do with oneself |

|

bharīe dina aiso lālana ke saṅga. |

|

|

Antarā |

|

|

Suna rī sakhī mẽ kā kahu to se |

Listen, dearest friend, what more can I say? |

|

una hī ke jānata dhaṅga. |

Only he would know this longing. |

राग यमन—बड़ा ख़याल

स्थाई

कहे सखी कैसे के करीए

भरीए दिन ऐसो लालन के संग ।

अंतरा

सुन री सखी में का कहु तो से

उन ही के जानत ढंग ॥

|

Audio Example 4.3.1 Rāg Yaman: baṛā khayāl, sthāī (TR, Track 5, 00:00–01:24) |

|

Audio Example 4.3.2 Rāg Yaman: baṛā khayāl, antarā (TR, Track 5, 10:04–11:20) |

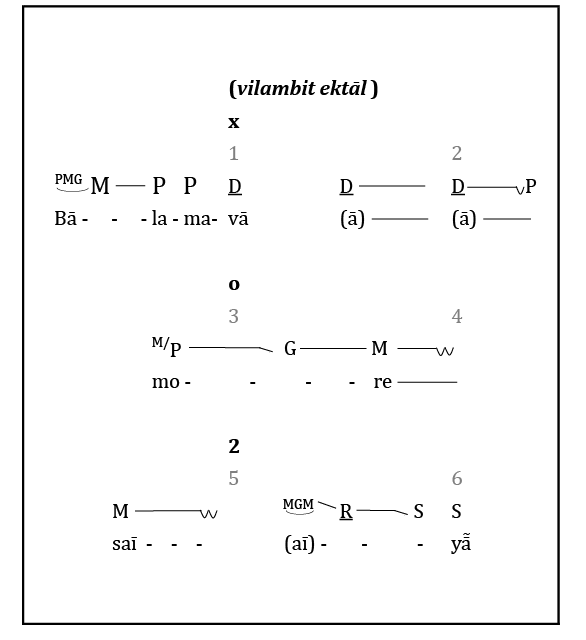

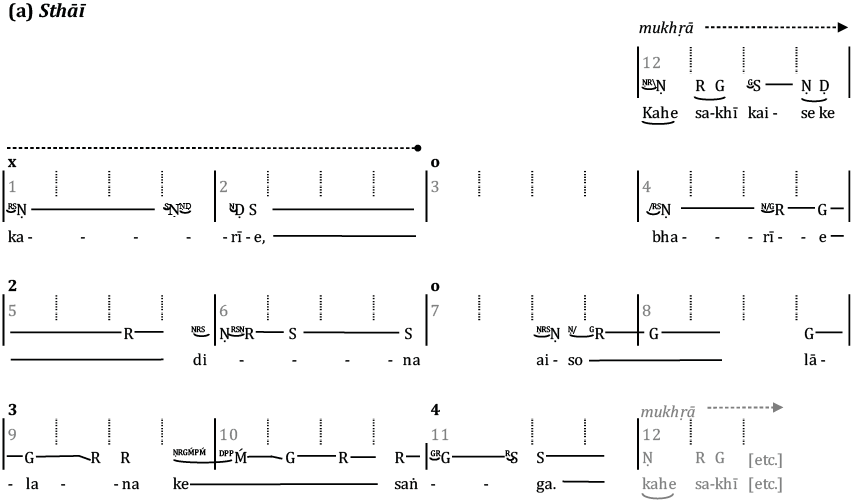

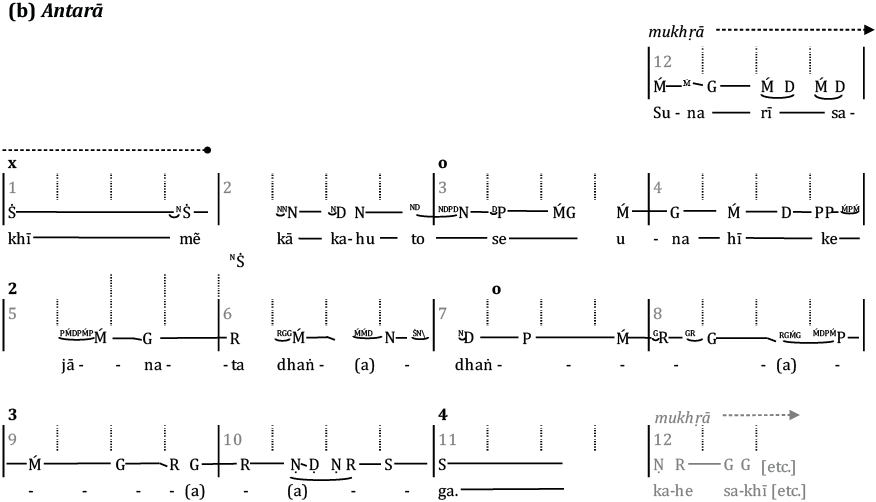

Musical notation might be incorporated into the learning process. Some teachers, adapting Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande’s (1860–1936) system, lay out the song in sargam notation on a spatial grid representing the tāl. (In the present volume, I have used this kind of notation for the choṭā khayāls of the Rāg samay cakra album.) However, since a baṛā khayāl tends to avoid any systematic attachment to the tāl, the student would eventually need to unlearn this metricised version of the composition, unlocking it from the beats and relaxing it into something more fluid. A more congenial approach—again one which I have evolved in my lessons with VR—is to notate a sketch of the bandiś using a kind of proportional notation to represent note lengths, in order better to capture the anibaddh feel of the delivery. This is illustrated in Figure 4.3.3, which in parts (a) and (b) presents the sthāī and antarā respectively of this Yaman bandiś in simplified form.

Fig. 4.3.3 Heuristic notation of bandiś: (a) sthāī; (b) antarā. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

In this style of notation there is only minimal reference to the metrical framework of the tāl (the exception being the mukhṛā, to be discussed shortly). The composition and its text are laid out phrase by phrase, showing the approximate relative duration of each pitch in sargam notation. Only when I have learnt this basic shape of the composition will I then seek to sing it accompanied by the tabla ṭhekā (which these days can be supplied digitally on an app for practise purposes), taking care to avoid too closely adhering to the individual mātrās. In learning how to fit the material into a single āvartan of the tāl, I have to listen out for salient points in the ṭhekā as approximate cues for where to begin or end a phrase. Such cues are indicated with parenthetical beat numbers in Figure 4.3.3. For example, beginning the second phrase around beat 4 of the sthāī (having taken a break after beat 2) avoids having to rush later on. And in an ektāl composition such as this, it helps to keep an ear open for beat 9—where the larger drum of the tabla returns to prominence—and beat 10—where the tabla plays the salient tirakaṭa pattern—in order to coordinate the later phrases around these points.

The most important point of interlock between bandiś and tāl—and the only significant point of departure from the anibaddh feel—is the mukhṛā. This is the head motif of the bandiś, which, unlike the rest of the composition, maps relatively directly onto the metrical underlay of the tāl. In an ati vilambit khayāl, it usually begins on or around the last macro-beat, and fairly explicitly marks out the sub-beats, creating a strong macro-up-beat to sam, after which it continues for another macro-beat or two, gradually relaxing the attachment to the metre. The mukhṛās for both sthāī and antarā are indicated in Figure 4.3.3(a) and (b), at which moments (and only these moments) a metrical grid is included for the approach to sam. It is important for the performer to have completed the sthāī (or, later on, whatever material they are inventing in any given āvartan) in time to sing the mukhṛā in its correct place in the lead-up to sam. Here this means completing the prior material by (or during) beat 11, so that the mukhṛā can re-emerge at beat 12.

This form of notation, then, is not intended as a literal transcription of what VR sings in the performance. Rather, it represents the general shape of the composition: the musical knowledge that a performer holds in their memory and which they will subtly differently realise on each occasion of performance. We might say that, commensurably with the fluid and ambiguous quality of time and form in a baṛā khayāl, the identity of the bandiś is essentially fuzzy: there is no definitive version, and it is likely to morph over time. Hence the ambivalent nature of musical notation, which runs counter to this spirit, but which can nonetheless be helpful provided one sees it for no more or less than what it is.

And ‘what it is’, in this context, might be something like Seeger’s (1958) conception of ‘prescriptive music writing’: a set of instructions for the performer. However, it would be more accurate to describe this as a heuristic version of the composition (cf. Section 2.3): it provides a pragmatic approximation—the gist of a structure—from which a student can get started with learning. But on any actual occasion of performance, the material will be decorated with ornaments (alaṅkār); and phrases might be elongated or contracted, or change their melodic contour. Even in this heuristic version, a few indications of ornamentation are warranted when, paradoxically, these are felt as integral to a musical gesture.

It is instructive to compare this heuristic version with Figure 4.3.4, a transcription of VR’s actual rendering as heard in Audio Example 4.3.1. This transcription would conform to Seeger’s category of ‘descriptive music writing’ (ibid.)—an as accurate as possible record of what is actually heard on a particular occasion. It includes the complete metrical framework of the tāl, which only makes more explicit how VR generally fashions his material so as not to coincide with individual mātrās (except for the mukhṛā). Also evident are the many decorations of the melody, generally shown as superscripted additions to the original outline (for more on ornamentation, see Section 1.8). These include kaṇ (a lightly touched grace note), and kaṭkhā or murkī (a rapid cluster of notes leading to a main note); oblique lines indicate mīṇḍ, an upward or downward glide. Perhaps most striking of all is the injection of significant additional material in the antarā after beat 6—a point to which I will return later.

Fig. 4.3.4 Transcription of bandiś: (a) sthāī; (b) antarā. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

In both versions of its notation, we can discern how the bandiś typically embodies the salient features of its rāg. The mukhṛā of the sthāī, for example, begins on Ṇi and rises to Ga (on the word ‘sakhī’), which are Yaman’s most prominent notes—saṃvādī and vādī respectively. And the melodic elaborations around these pitches (Ṇ– RG, S– ṆḌ Ṇ—) are likewise characteristic of the rāg. The sthāī as a whole also conforms to convention by occupying the lower–middle range. After the initial focus on lower Ni, it sustains the vādī tone Ga for much of its duration, rising briefly to Pa in its final phrase before returning to the mukhṛā (incidentally, VR foreshadows this overall melodic ambit in the preceding ālāp, as heard on Track 4 of the album). Complementing this, the antarā foregrounds the upper vocal register, initially focusing on tār Sā.

To summarise our account so far: by resisting notation, the bandiś asserts itself as a subjectively felt flow in which its identity can morph; and this is of a piece with the braided interplay of nibaddh and anibaddh temporalities of a baṛā khayāl more generally. To this we now need to add a further temporal notion: a baṛā khayāl punctuates this flow with a series of artfully timed events that shape its larger structure. Let us consider this evental property in more detail.

Sthāī and Antarā as Event

In a different context, Mark Doffman (2019) invokes the Greek rhetorical terms chronos and kairos to characterise a distinction between temporal process and event respectively. As Doffman puts it, chronos ‘considers time as durational and cyclical’, while kairos ‘invokes the singularity and heterogeneity of temporal experience’. Chronos is ‘processual’: it ‘relates to the sense of a sequentially structured flow’. Kairos is ‘eventful’: it ‘projects the idea of a timely or singular moment’ (2019: 171). Doffman is writing with jazz in mind, but it would not take a great stretch of the imagination to apply these notions to the Hindustani context. Having already considered a baṛā khayāl as ‘a sequentially structured flow’ (its chronic aspect), what can we say of its ‘eventfulness’ (its kairic aspect)? Again, the bandiś contains the essence, since the statements of its two discrete components, sthāī and antarā, clinch decisive structural events.

The very first event of a baṛā khayāl is a complete statement of the sthāī. Its mukhṛā feels especially portentous, marking simultaneously the onset of the sthāī, the bandiś and the baṛā khayāl itself. Furthermore, this moment of inception is dramatised by the entry of the hitherto silent tabla. The tabla player takes his cue from the vocalist, who uses the mukhṛā—the only part of the composition that is sung metrically—to indicate the tempo. Following this lead, the tabla player enters on sam. Or, indeed, just a moment before: in Audio Example 4.3.3 we hear how, in VR’s Yaman performance, Shahbaz Hussain enters with his own, rhythmic mukhṛā halfway through the last sub-beat of the vocal mukhṛā—a stylistically typical rhetorical flourish that galvanises time, intensifies the lead-in to sam, and signals that the baṛā khayāl is now underway.

|

Audio Example 4.3.3 Mukhṛā of the sthāī, with tabla entry (TR, Track 5, 00:00–00:08) |

Two further ways in which the bandiś is delivered suggest time in the aspect of kairos. First the antarā is delayed until around halfway through the performance (see Figure 4.3.2); the timing of its arrival becomes an issue for the performer: it is dramatised, and in this way becomes a major structural event (I shall elaborate further on this below—significantly, when the time comes). Secondly, both sthāī and antarā are usually heard only once in their entirety. After the sthāī has been sung in the first āvartan we can expect never to hear it sung complete again; and after the antarā has been sung complete (much further down the line) we reach another turning point in the performance. Each of these factors defines these moments as unique, and hence as events. Meanwhile, the component that assuredly is reiterated is the mukhṛā of the sthāī, which is sung at the end of practically every successive āvartan as a bridge to the next. Acting as a refrain, the mukhṛā causes just about every arrival on sam to feel like an event (kairos) on a localised level; while on the bigger canvas its appearances act as a temporal yardstick with which to calibrate the long-term temporal flux (chronos) of the performance.

Given that the composed material of the bandiś lasts little more than a couple of minutes, the big question for the vocalist, as ever in this classical tradition, is how to generate the rest of the performance. After the sthāī, what next? How does one get to the antarā? And then what? As Figure 4.3.2 indicated, there is a cognitive road map available to help the performer navigate this journey. However, the travelling still has to be done in real time; so in the remainder of this essay I will consider how this is managed, looking at the processes and events of the two main stages in turn.

Baṛhat: Analysis of a Process

Following the opening statement of the sthāī comes a staged series of improvised elaborations of the rāg—a process often termed baṛhat, derived from the Hindi verb baṛhānā, ‘to increase’ (Magriel and du Perron 2013, I: 409; Ranade 2006: 195–6). Some (for example, Ruckert 2004: 58–9) also use the word vistār (‘expansion’) to describe this process, though in this book I tend to reserve that term for more episodic appearances of bol ālāp in a choṭā khayāl. Regardless, this stage of the performance is a process of development—but of what: the bandiś or the rāg itself? The answer is characteristically ambiguous. Already we have alluded to the fuzzy form of the bandiś—due to a combination of its one-off appearance and its mutable, notation-eluding identity. Going further, we might claim that the bandiś and rāg represent far less distinct categories of musical material in a baṛā khayāl than they do in a choṭā khayāl. If the rāg is embedded in the DNA of the bandiś (I have already described how the bandiś projects the structure of the rāg), the genome of the bandiś is in turn detectable throughout the baṛhat. Hence, to the extent that the bandiś and the rāg are of a piece, this slowly expanding exposition of the rāg also implies a development of the composition. And although the sthāī does not re-emerge complete after its initial exposition, its presence in the baṛhat phase is upheld in two ways: first via the refrain function of the mukhṛā, in which the part stands for the whole (indeed, there are anecdotal accounts of listeners mistaking a mukhṛā for a composition); and second via the continuing presence of the text, which the soloist freely incorporates into his or her extemporisations—though rarely in its entirety, and not necessarily at every point, since sometimes sargam syllables or ākār might be employed.

Audio Example 4.3.4 illustrates these various points. This picks up the performance at the close of first āvartan, where VR concludes the sthāī, sings the mukhṛā, and begins the second āvartan. At this early stage in the proceedings, he still models his material quite closely on the sthāī, but now repeats the words ‘karīe’ and ‘bharīe’, dwells on lower Ni and middle Sā, then moves via Re to Ga as he sings ‘aiso lālana’, and finally presents an elaborated version of the mukhṛā as he approaches and begins the next āvartan.

|

Audio Example 4.3.4 Baṛhat: development of sthāī from end of āvartan 1 to beginning of āvartan 3 (TR, Track 5, 00:55–02:31) |

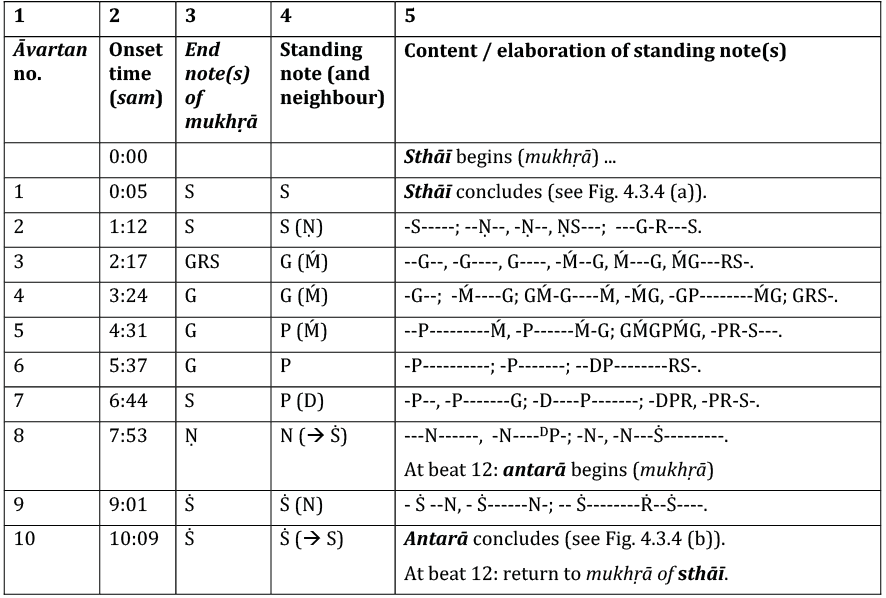

Performers sometimes describe what they do in the baṛhat as simply ‘ālāp’, or bol ālāp (given that the text is present for much of the time)—which points to the prevailing anibaddh feel. But a larger-scale process is also going on: one of subtle long-term intensification, through increasing rhythmic activity, increasingly ornate elaborations, and a gradual rise in vocal register (in Sections 3.3 and 4.2, I referred to this with the shorthand ‘AI’—accumulation of intensity). This last aspect, registral ascent, is charted for VR’s performance in Figure 4.3.5 (by way of comparison, see Nicolas Magriel’s highly systematic analysis of the baṛhat of a 1981 performance by khayāl singer Ustād Niaz Ahmed Khan (Magriel 1997)). In my analysis, successive āvartans are numbered in the leftmost column, and are correlated in the next column (2) with the time code of their onset (sam). Column 3 indicates the final pitch of the mukhṛā, which straddles sam and closes around beat 2, and, like everything else, is subject to variation. Hence, although Figure 4.3.3(a) and Figure 4.3.4(a) show how, in the sthāī, the mukhṛā closes on Sā, once the baṛhat is under way, this terminus may change to mirror the overall ascending trajectory (for example, Ga in āvartans 4–6). But the main, and most systematic, traces of this long-term ascent are found in the main body of the improvised material, whose pitch content is abstracted in columns 4 and 5 of Figure 4.3.5. Column 4 pinpoints the ‘standing note’ or nyās svar which VR makes his focal point in each āvartan—a way of providing structure to his improvisation. Reading down the column, we see how these successive standing notes manifest a gradual ascent through the scale of the rāg, āvartan by āvartan—from middle Sā in āvartan 2 to upper Sā in āvartan 9, coterminous with the beginning of the antarā.

Fig. 4.3.5 Baṛā khayāl in Rāg Yaman: stages of baṛhat. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

Not every note of every rāg can be sustained in this way—this will depend on the individual rāg grammar. In Yaman, the available nyās svars are Sā, Ga, Pa and Ni; nonetheless, Re, Ḿa and Dha are also permitted some prominence as salient neighbours to the standing notes, to which they will eventually fall or rise. Such examples of ‘helping notes’ are shown in parenthesis in column 4 next to their respective nyās svar. This shows, for example, how VR subtly gives prominence to Ḿa in three successive āvartans: as a yearning upper neighbour to Ga in āvartans 3 and 4; and as a lower-neighbour elaboration of Pa in āvartan 5. This judicious handling of Ḿa helps effect a transition from Ga to Pa, blending the colours of these three different tones.

Even allowing for the inclusion of such adjunct svars, the contents of column 4 remain highly abstract. They model the kind of schema a soloist will likely have in their mind to help them pace their progress through an extended performance. Nevertheless, there is the question of how to put flesh on these bare bones. Column 5 of Figure 4.3.5 shows the traces of such a process. For each āvartan, it indicates how the focal nyās svar is elaborated between the opening and closing statements of the mukhṛā. For example, in āvartan 4—Audio Example 4.3.5—Ga and its supporting neighbour, Ḿa, are presented in the following sequence of phrases (other, decorative notes are not shown):

[mukhṛā] -G--; -Ḿ----G; GḾ-G----Ḿ, -ḾG, -GP--------ḾG; GRS-. [mukhṛā]

|

Audio Example 4.3.5 Āvartan 4 (with opening and closing mukhṛās): elaboration of Ga and Ḿa (TR, Track 5, 03:19–04:33) |

I am using the term ‘phrase’ here in quite a loose sense, the minimum criterion for which is a brief break in the musical flow. This means that some of the elements in this analysis—those followed by a comma—might more correctly be termed sub-phrases. Others have relatively greater closure, and are shown with semi-colons. The last phrase falls to Sā, before the onset of the mukhṛā, and is shown with a full stop. The punctuation marks here are in one sense metaphorical: VR sometimes uses this idea with me to think about how to build successive phrases of an ālāp into a larger one, to create a coherent ‘sentence’ rather than formless noodling. This is a heuristic pedagogical strategy; but it also reflects the theoretical point that the melodic structure of a rāg performance, and indeed the principles of rāg itself, can be construed syntactically (see Clarke 2017).

The dashes featured in the notation of column 5 also contain coded information. They indicate the relative prolongation of the svar with which they are associated—one dash represents approximately one sub-beat’s duration. ‘Prolongation’ can mean that the svar in question is itself sustained, or it can mean that it is decorated by other notes and figuration during this time span (either before or after the nyās svar). It would, in principle, be possible to illustrate these manifold decorations through the kind of detailed transcription shown in Figure 4.3.4 for the bandiś. But my purpose here is different. The information shown in column 5 of Figure 4.3.5 is intended as a reductive ‘gist’ of how each nyās svar in column 4 is elaborated—revealing the structure behind the elaboration. It stops short of notating the decorative minutiae, which are audible enough in the recording and can be savoured against this middle ground.

For most of the duration of an āvartan the standing note shown in column 4 is also the highest note. It acts as a kind of limiter on the pitch bandwidth, which helps the soloist pace their progression through the baṛā khayāl. (This principle derives from the extemporisation of an ālāp—see my discussion of ‘svar space’ in Section 3.2, Exploration 1.) It is, however, permitted to relax this constraint towards the end of an āvartan, in order briefly to suggest the (higher) main note of the next—a kind of sneak preview. Column 5 shows how this happens at the end of āvartan 2, which, focusing on Sā neighboured by lower Ni for most of its duration, rises to Ga in the concluding phrase, before descending via Re back to Sā. This foreshadowing is sometimes also echoed at the close of the succeeding mukhṛā. For example, at the beginning of āvartan 3, the mukhṛā also ends Ga–Re–Sā (see column 3), rather than closing directly on Sā as originally heard in the sthāī.

In its slow and gradual working through the background grammar and foreground subtleties of the rāg, the baṛhat phase takes the form of a ‘sequentially structured flow’. Here, then, we experience time in the guise of chronos. The overall trajectory of this process—as shown in Figure 4.3.5, column 4—is towards tār Sā and the onset of the antarā. This is a key event in the larger-scale structure; hence time at that moment is experienced as kairos. Typically, chronos and kairos become blended in the approach to this structural moment, as the soloist teases the listener regarding the actual time of arrival of tār Sā. In Audio Example 4.3.6, we can hear how VR does this in āvartan 8 (cf. Figure 4.3.5, column 5) through an extensive and intense prolongation on Ni. Repeated iterations of this pitch push all the while towards upper Sā which is eventually attained and sustained in the final phrase. And this moment triggers the onset of the antarā, whose own mukhṛā, sung to the words ‘Suna rī sakhī mẽ’, is heard on beat 12 of the slow ektāl cycle (see Figure 4.3.4(b)), and leads us into āvartan 9.

|

Audio Example 4.3.6 Āvartan 8: prolongation of Ni, leading to tār Sā (TR, Track 5, 7:52–09:10) |

At this point, there is a further delaying tactic. Rather than launch into the complete antarā, VR follows the baṛā khayāl convention of presenting at least one further āvartan of bol ālāp before the antarā begins. In principle it is possible to extend this process for two or more āvartans, moving further into the upper octave; but commonly, as in VR’s performance here, just one proleptic bol ālāp is enough. This can be heard in Audio Example 4.3.7; the pitch content is again outlined in Figure 4.3.5, column 5, āvartan 9. VR makes an extended extemporisation around tār Sā to the word ‘sakhī’, after which the antarā is then heard complete in āvartan 10. Hence, while the main part of the baṛhat process follows the sthāī, the baṛhat associated with the antarā is anticipatory—it is filled with expectancy. The antarā functions as the climax of the baṛhat process—its outcome, even.

|

Audio Example 4.3.7 Āvartans 9 and 10: prolongation of tār Sā leading to antarā sung complete (TR, Track 5, 08:51–11:22) |

Across the course of a single āvartan, the antarā typically follows a descending path from tār Sā to mahdyā Sā. This is discernible in the heuristic notation of Figure 4.3.3(b) which also shows the stopping-off points in this process. The first phrase (‘Suna rī sakhī mẽ’) intensely voices tār Sā; the second (‘kā kahu to se’) emphasises Ni before falling to Pa; the third (‘una hī ke) also winds around Pa and rests there; the fourth (‘jānata’) falls from Pa to Re; and the final phrase (‘dhaṅga’) echoes this shape but continues to the concluding madhya Sā, deploying a characteristic Yaman cadential figure, P–R–S.

This, at least, is the notional outline. The contingencies of live performance, however, might take the vocalist along other byways—as can be seen by comparing Figure 4.3.3(b)with Figure 4.3.4(b), the transcription of what VR actually sings. This most obviously shows how he weaves various beautiful decorations into the heuristic form; but another difference also transpires: he concludes the penultimate phrase (‘jānata’) early in the cycle, at beat 6. Its pregnant final Re strongly implies the ultimate descent to Sā—but there are still five long beats to go before the mukhṛā. In the hands of an experienced performer, such contingencies can be readily absorbed within the elasticity of the form. On ‘dhaṅga’, VR recoups the upper register, rising from Ḿa to Ni; restates the first syllable as he slowly re-treads his steps down to Ga across beats 7 and 8; then with a flamboyant kaṭhkā regains Pa at the end of beat 8 and gradually descends once again, reaching mahdya Sā at beat 11 via an elliptical movement to mandra Ni and Dha in beat 10. This spontaneous moment of invention is as good an illustration as any of the blurred boundary between bandiś and bol ālāp in a baṛā khayāl.

The antarā’s descending trajectory is a mirror image of the baṛhat as a whole, which in essence rises from Madhya Sā to tār Sā. Over the course of just one āvartan, the antarā captures and then releases the intensity of that process. But given that the preceding baṛhat has taken so much longer, it would feel premature to end the baṛā khayāl here. And indeed, this moment, followed by a return to the mukhṛā of the sthāī, heralds the beginning of a new phase.

Laykārī

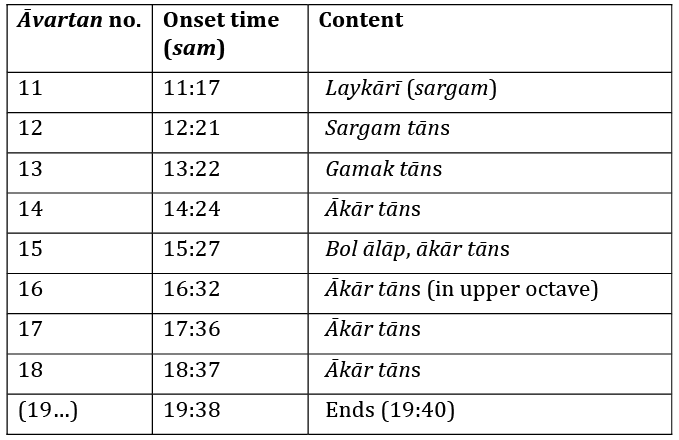

The emphasis now turns towards various forms of rhythmic variation, or laykārī (for a detailed discussion of this notion, see Clayton 2000: chapter 10). Henceforward we hear VR making a more explicit engagement with the pulse and metre of the tāl, changing the feel from anibaddh to nibaddh, and from introversion to extraversion. It is common, though not compulsory, for the tempo now to move up a gear: in the baṛā khayāl in Rāg Bhairav on the Twilight Rāgs album, VR indeed increases the lay (Track 2, 12:15); whereas at the equivalent point in the Yaman baṛā khayāl (Track 5, 11:23) he maintains the same pulse. Despite the change of delivery style, the muhkṛā of the sthāī remains a presence, articulating sam, marking out the āvartans and maintaining continuity and unity.

Fig. 4.3.6 Second part of baṛā khayāl: laykārī etc. Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC-SA.

As in the baṛhat phase, the aim is now carefully to build the intensity over the course of several āvartans. The soloist has a variety of techniques at his disposal, and Figure 4.3.6 details how VR deploys them in this performance. One common device is bol bāṇṭ, in which the song text is manipulated and treated syllabically, creating syncopation and/or cross-accentuation. VR uses this technique in his Bhairav baṛā khayāl (Track 2, 12:22–12:55) but not in its Yaman counterpart. Instead, in āvartan 11, he creates a similar laykārī effect using sargam—as captured in Audio Example 4.3.8.

|

Audio Example 4.3.8 Āvartan 11: laykārī (TR, Track 5, 11:20–12:04) |

The momentum engendered by this laykārī treatment continues in āvartan 12, where VR launches an array of sargam tāns—melodic runs sung to sargam syllables (Audio Example 4.3.9). The switch to this technique helps the baṛā khayāl progress incrementally, retaining the previous use of sargam syllables but now eliciting these in a steady rhythmic stream, four syllables to a sub-beat (sixteen to a macro-beat). Throughout, VR injects various twists and turns into the melodic flow, and further resists uniformity by briefly teasing the metrical constraints (at 00:37 of the audio example), and by momentarily morphing sargam into ākār/ekār/ikār tāns—‘ga-a-a, re-e-e, ni-i’ (at 00:43).

|

Audio Example 4.3.9 Āvartan 12: sargam tāns (TR, Track 5, 12:26–13:24) |

In āvartan 13, VR presents several strings of gamak tāns, illustrated in Audio Example 4.3.10. With this change of technique he again creates a sense of progression: he continues the preceding tāns at the same speed, but now transforms the style of delivery; gamak tāns involve making a wide oscillation around each note (a technique key to the dhrupad vocal style). Then, in āvartan 14, these become pure ākār tāns (i.e. sung to the vowel ‘ā’), as VR moves into the higher register (Audio Example 4.3.11). In the third and fourth of five runs he uses a head voice as he ascends to tār Ga and tār Ḿa respectively. What also compounds the intensity here is a ratcheting up of rhythmic complexity. Listeners with sharp ears (or access to appropriate software) will spot that VR rolls out his tāns at a rate of five notes per sub-beat (or twenty notes per macro-beat), and that their melodic grouping does not coincide with the beats but rather cuts unpredictably and ambiguously across them. This is a characteristic laykārī technique (Clayton 2000: 159–66), and points forward to a tour de force of tān work with which VR ends this baṛā khayāl.

|

Audio Example 4.3.10 Āvartan 13: gamak tāns (TR, Track 5, 13:25–13:47) |

|

Audio Example 4.3.11 Āvartan 14: ākār tāns (TR, Track 5, 14:23–15:28) |

But we are not at this point yet, and, as if to remind us of the fact, VR begins the next āvartan (15) with an extended passage of bol ālāp, focusing on the word ‘sakhī’ and the note tār Sā (rising to tār Re at 00:37 of Audio Example 4.3.12). In doing so, he creates contrast with the prevailing singing style while maintaining intensity. This also enhances the unity of the performance by recalling the baṛhat phase of the baṛā khayāl. However, the reversion to bol ālāp is only temporary, and shortly before the ninth macro-beat (at 0:46 of the audio example) VR resumes singing ākār tāns, deferring the mukhṛā until the last two sub-beats, where it is sung at double speed (dugun).

|

Audio Example 4.3.12 Āvartan 15: return to bol ālāp singing style (TR, Track 5, 15:23–16:35) |

Having re-entered ākār tān mode (his self-confessed specialism), VR stays there, sustaining a plateau of intensity for the final three āvartans with a dazzling display of invention and virtuosity. Typically, he makes no single consummating final gesture, since the baṛā khayāl is by no means the end of the performance. Instead, after the final mukhṛā, he segues into the up-tempo choṭā khayāl, ‘Śyām bejāi’.

Conclusion

Through the preceding account we have journeyed with VR through the course of a baṛā khayāl performance. We have considered how the conventions of Hindustani classical music in general—the grammar of rāg, the ordering framework of tāl—and those of a baṛā khayāl in particular—its ground plan of events, its dialectic between the metrical and non-metrical—come together to make this a quintessential form of extended rāg performance. Practised and internalised over many years, these conventions become absorbed in a musician’s consciousness until they become second nature: not merely theoretical but also experiential knowledge, absorbed into his or her mind and body over many performances, developing as an ever-more refined ability to fashion the temporal unfolding of a baṛā khayāl’s two large-scale waves of mounting intensity.

It is probably not coincidental that the evolution of a baṛā khayāl over the course of the twentieth century into its now-archetypal guise is coeval with India’s own negotiation with modernity. As Hindustani classical music increasingly became a secular concert practice, its leading musicians sought to develop its forms and conventions to allow more aesthetically substantial statements which, intentionally or otherwise, compare in magnitude to those of western classical traditions. As ever, this process has been conducted on the subcontinent’s own terms, leading to a canon not of great works and great composers, but of great exponents and pedagogical lineages (gharānās), and legendary performances. Many of these have been captured by contemporary recording technology and globally disseminated, including, in the present day, over the internet.

This is paramparā: the weight of tradition, of long lines of illustrious forebears, of conventions and codes of performance. This is what bears on every musician as they sit down alongside their fellows and before often highly knowledgeable audiences—as they centre themselves within the resonance of the tānpurās and begin to sing or play. This is what is reborn in every moment of a performance. And, on a personal note, this is what was tangible on the day in 2006 when VR, Shahbaz Hussain and Fida Hussain sat down in a recording studio at Newcastle University to record Twilight Rāgs from North India. Each track was captured in a single take with only minimal post-production editing (and with impeccable sound engineering by John Ayers). The album stands as a record of this event and as a document of VR’s role as a bearer of the legacy of his several teachers, most notably Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, and the Kirānā gharānā.

Epilogue: Laya/Pralaya

On a chilly October morning, I’m sitting in a café in a leafy suburb of Newcastle upon Tyne with my fellow khayāl student Sudipta Roy. In her day job, Sudipta is a professor of electrochemical engineering, but like me (David Clarke), she is also a śiṣyā of Vijay ji; in the guru-śiṣyā scheme of things, that makes her my guru-bahan (guru-sister) and me her guru-bhāī (guru-brother). We sometimes take our vocal class together, and have on numerous occasions shared a stage as performers. Over the years, Sudipta and I have spent many hours in our favourite coffee shops and eateries sharing our thoughts on academic life, Indian music, and the experience of learning from our guruji. If learning khayāl over some two decades has inadvertently become an extended piece of fieldwork for me, Sudipta, as well as being a good friend and ally, has been a key cultural interpreter on this ethnographic journey, sharing with me insights into Indian culture that have enriched and complemented Vijay’s musical tutelage.

On this occasion, I’m updating her on how things are going with Rāgs Around the Clock. I’ve just completed a draft of the chapter on baṛā khayāl, and over brunch we compare notes on what it feels like to actually sing one—on how you fit the loose and shifting rhythmic profiles of the sthāī and antarā into a tāl cycle.

‘I don’t really think of this like a bandiś in the normal sense’, Sudipta says. ‘It’s not rhythmically tied down like in a choṭā khayāl—it’s more like an ālāp. But in any case, we Bengalis, we don’t really use the term ālāp, even for an actual ālāp—we’d just say anibaddh, you know, “unmeasured”. And for a “normal” bandiś, like in a choṭā khayāl, we’d say nibaddh, “measured”. Bandiś means to bind, right? In a choṭā khayāl the song’s bound to the lay, the rhythm, but in a baṛā khayāl it isn’t like that, really’.

I nod. That’s my experience too, I say: the composition in a baṛā khayāl does similar work to the bandiś of a choṭā khayāl, but it just doesn’t feel the same on account of its ambiguous relationship with metre. And now that I think about it, I’ve sometimes felt myself equivocating around the word bandiś when talking about baṛā khayāls (oddly, the English word ‘composition’, which doesn’t have the connotation of ‘binding’, feels OK).

And then, almost in passing, Sudipta goes on to mention something that opens up our dialogue onto something altogether more fundamental.