1. Introduction

©2024 Petri Hoppu, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.01

The minuet is a Western European dance with particularly strong symbolic and cultural meanings. It is a couple dance in 3/4 time but, unlike other well-known couple dances like the polka or tango, partners do not touch each other for most of the dance. Instead, they move together, facing and passing each other, following predetermined figures, and using specific minuet steps. This book examines the minuet in the Nordic countries where it achieved popularity alongside many other European countries during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Surprisingly, the tradition of dancing the minuet continues in some Nordic areas into the present day.1

The minuet is known in the Western world as a couple dance and music form that originated in the baroque era, specifically in the court of Louis XIV. In the popular imagination of today, it is a smooth and dignified dance, associated with wigs, large dresses, and tricorne hats. The purpose of this book is to show that this image of the minuet is too one-dimensional and that, especially in the Nordic countries, the minuet has appeared and still appears in many forms and contexts, as well as among many different groups of people.

What may be a surprise for some people, even those living in the Nordic countries, is that the minuet occupied a prominent position in the popular culture of the region in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, being danced by nobles and also by peasants. The dance, as part of the region’s social and cultural structures, impacted the development of society. From the late nineteenth century, the minuet ceased to form part of the active dance repertoire at social events in Europe, but exceptions to this exist in the Nordic countries: specific areas of Finland and Denmark continue to dance the minuet even today.

Over the centuries, discussions of the minuet have emphasized its formality and imagined rigidness. These qualities are suggested by metaphorical usage of the name ‘minuet’ but often also by theatrical staging of the dance. This book will counter such characterizations, contrasting the reality of dancing with such discourses. Whether as a court dance or a peasant dance, the minuet has enjoyable and lively dimensions. It can be noble and dignified but also cheerful, sensual, and intimate. This book is not the final truth about the minuet, but it reveals the minuet’s multiple dimensions and opens new Nordic and embodied perspectives on it.

The Intriguing Minuet

The minuet, monsieur, is the queen of dances, and the dance of queens, do you understand?2

This quotation is taken from a fascinating 1882 short story by the French writer Guy de Maupassant in which an old man reminisces about his youth as a dancer of the minuet. The man comes to a park every day, wearing a costume and shoes from the ancien régime (the social and political regime in place at the time of the French Revolution in 1789). He draws the attention of the narrator, who finally asks, ‘What was the minuet?’ This question revives the old man, and he replies with a lengthy description of the dance. The story culminates with the older man and a female companion performing the minuet as the narrator looks on in astonishment:

They advanced and retreated with childlike grimaces, smiling, swinging each other, bowing, skipping about like two automaton dolls moved by some old mechanical contrivance, somewhat damaged, but made by a clever workman according to the fashion of his time.3

Few dances in the Western world have achieved the iconic status of the minuet. Since the seventeenth century, the minuet has been an important part of European culture, particularly in the discourses of dance and music. The subject continues to intrigue scholars and artists from the fields of performing arts and cultural studies. Similar attention is given to the waltz and tango, relating these couple dances to particular eras, symbolism, and behaviour. Yet, in many ways, the minuet stands on its own in European cultural history.

We, the authors of this book, share the curiosity of de Maupassant’s narrator regarding this dance tradition. We ask what was the minuet, but we also ask what is the minuet? Our study has involved reading about it, but also observing others as they danced it and dancing it ourselves, examining the minuet as a historical dance and also as a part of living tradition in some rural areas of the Nordic countries. We are fascinated by its originality, persistence, diversity, and its ability to survive throughout the centuries. These are the reasons we have compiled this book: an anthology of the Nordic minuet.

Dance and Metaphor

In a 1985 article about the minuet and its research, Julia Sutton wrote that:

[o]f all the dances popular from the accession of Louis XIV to the throne of France in 1661 until the French Revolution in 1789, the minuet is surely the most universally associated with that elegant period, not only because of its great popularity in its hey-day, but because it was the only baroque and rococo dance of that dancing time to be incorporated into the classical symphony and sonata, thereby remaining to the present day in the public ear (though not its eye), as a delightful reminder of an earlier time.4

At the time Sutton was writing, many dance scholars and teachers had already begun investigating the minuet’s steps and figures as described by eighteenth-century printed and manuscript sources. From the early twentieth century, interpretations of the minuet have manifested in performances by companies specializing in historical dances. Sutton lamented in her article that the minuet’s origins were not clearly traced by such groups. She saw dance scholars’ different theories and hypotheses as contradictory, crying out for new scrutiny. Sutton observed that the minuet’s history after the French Revolution and its ‘folk’, or less aristocratic incarnations, was deserving of special attention.5

Intriguingly, Sutton called the minuet an ‘elegant phoenix’: a dance and musical form that had preserved its special symbolic status in Western culture over the centuries.6 This status has contributed to the considerable interest in the minuet from dance historians since the nineteenth century. Sherril Dodds, for example, noted that the minuet as a form of court dance has been highly valued by those interested in so-called historical dances—that is, high-society dances that were popular prior to the twentieth century.7 Such scholarship has a history of its own since the nineteenth century.8 Researchers of historical dances do have an established network of global scholarship, despite the often contemporary focus of the field of dance studies. Thus the minuet is part of a cultural dance phenomenon that has intrigued many scholars around the Western world.

One reason for ongoing interest in the minuet is that the dance has proved to be extremely persistent. The modern misconception is that the minuet disappeared from European courts and the standard repertoire of the nobility during the French Revolution in the late eighteenth century. Instead, it re-emerges like a phoenix over and over again in different contexts in Europe during the subsequent centuries. Indeed, the minuet reappears not only as a dance but also as a metaphor for something dignified, rigid, old-fashioned, or peculiar.

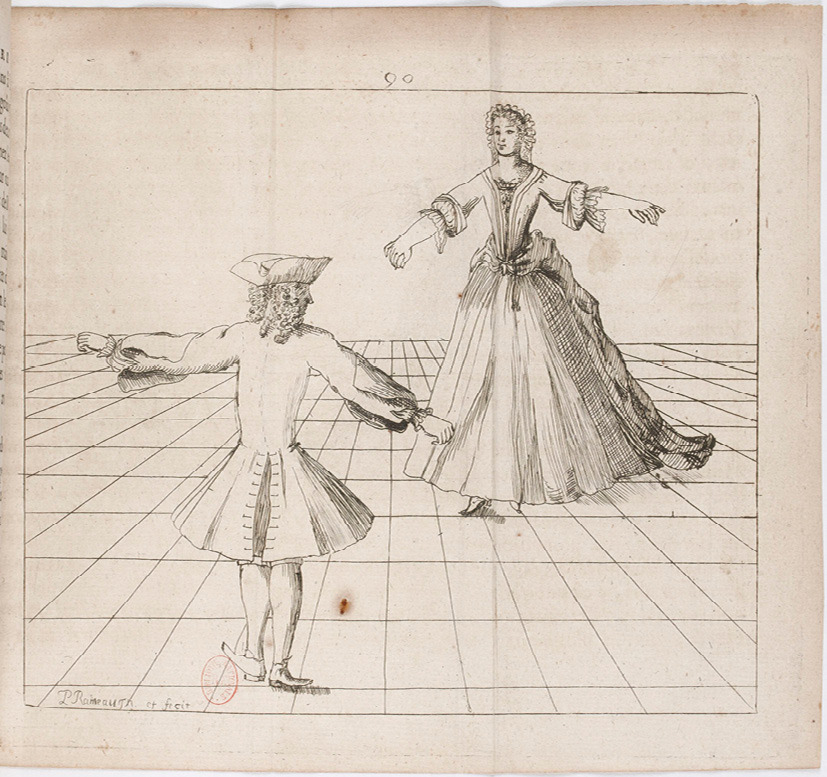

Fig. 1.1 The minuet. Pierre Rameau, Maître à danser (1725), engraving. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rameau_menuet.jpg, public domain.

As will be addressed in detail later in this book, the minuet continued to be performed throughout the nineteenth century. Surprisingly, it even appeared as part of the tradition of court balls within the German Empire at the end of that century. Minuets have also been spotted on Western stages, in theatres and films, most often to connote the atmosphere of the ancien régime. More recently, the dance has appeared primarily in metaphorical usage in different contexts. A brief look at academic and literary texts published in the last fifty years reveals many instances in which the minuet is used in this figurative manner.

An American postmodern writer, John Hawkes, commenting on his erotic novel The Blood Oranges in 1972, wrote that:

It seems obvious that the great acts of the imagination are intimately related to the great acts of life—that history and the inner psychic history must dance their creepy minuet together if we are to save ourselves from total oblivion.9

Hawkes seems to refer to the minuet as a metaphor for complicated and forced interaction that follows a specific structure to bring about clarity regarding human reality.

Similarly, in 1977, the American educational theorist Eva L. Baker contrasted the hustle (a fast-paced dance popular in the 1970s) and the minuet, using these as metaphors for evaluation:

As evaluations, the hustle and minuet differ along other continua, from energetic to passive, or exuberant to reserved. Notice, however, that these dances, as evaluation, both contribute at a marginal level to the serious pursuits of their times.10

Baker views the minuet as an example of the worldview of a particular historical era, likening this to the changing dynamics of evaluation in education.

A Russian-born scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, Leon Aron, suggested in his 1995 article that relations between the USA and Russia/The Soviet Union could be characterized as an act of tango dancing but proposed that they could be improved by changing to something more akin to the minuet:

How about the minuet for a model: elaborate, graceful, slow, aloof, and cerebral? The partners spend a great deal of time away from each other, yet get together at regular intervals, give right hands to each other, and, upon turning a full circle, part again until the next occasion.11

Aron regards the salient features of the minuet as positive and aspirational, emphasising its regularity and predictability. He considers that the nations’ relationship would benefit from a regular and stable structure, not the random and uncontrollable character of the tango.

A Finnish environmental psychologist, Liisa Horelli, used the minuet as a metaphor for a traditional and essentialist way of looking at gender in her article ‘Engendering Evaluation of European Regional Development: Shifting from a Minuet to Progressive Dance!’ (1997). Although Horelli does not refer to the dance in her main text but only in the title, the message is clear. This article suggests that the titular minuet symbolizes binary gender roles which cannot be crossed. In contrast, progressive dance embraces gender-inclusive policy-making strategies, seen as an alternative to rigid gender roles.12

A final, and perhaps most surprising, example comes from an American professor of molecular and cellular biology: David D. Moore. He commented on his colleagues’ research paper and used the minuet as a metaphor for processes taking place on the metabolic level:

In the minuet, a popular court dance of the baroque era, couples exchange partners in recurring patterns. This elaborately choreographed exercise comes to mind when reading [this] paper [...]. In this study, the nuclear receptors [...] are two of the three stars in a metabolic minuet that promotes appropriate fat utilization.13

Moore compares the precise and repetitive form of the minuet to the interaction between nuclear receptors. As a metaphor, the dance’s elegant choreography describes the pattern of the human metabolic system.

These examples indicate that the minuet is typically characterized by the attributes of calmness, ceremonialism, formality, and dignity. It is associated with highly formal behaviour, a quality that can be considered positive or negative depending on the context of the author reviewing the dance.

In all its different social contexts from courts to peasant villages, the minuet retains a human, corporeal dimension. It is not only a strictly formal dance, as its metaphorical usage suggests, but also an enjoyable and cheerful dance: an embodied experience. In the Nordic countries, where the minuet continues to be part of folk dancers’ repertoires, it is clear that the dance retains this expressive function. The minuet remains alive as both a narrative and dance practice.

Nordic Narratives and Embodiments

All of the continental Nordic countries have documented information about the minuet dating from the seventeenth century to the present day, encompassing all classes of society. In many ways, this is peculiar and unique. While the dance has not generally been a part of the active dance repertoire at European social events since the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, it has been performed in some areas of Finland and Denmark as late as in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This book argues that the minuet has had a remarkable position within dance culture in the Nordic countries, not only amongst the upper classes but also amongst the bourgeoisie and peasant population. The dance has been a part of the region’s social and cultural structures and has impacted the development of those structures.14 In the Nordic countries, the minuet is a cultural artefact that carries complex narratives and practices from various eras and areas.

It is no coincidence that various pieces of information about the minuet are found all over ‘Norden’ (the collective name given to Nordic countries in Scandinavian languages). Each Nordic country has a specific history of its own, but all share common social and cultural narratives and heritage. Norden, as defined by Peter Aronsson and Lizette Gradén, is a collective performative space, resulting from repeated performances.15 The performances are points of departure for narratives and embodied experiences that connect people to the shared concept of Norden.

The Nordic collective space has been formed over the centuries as the Nordic countries have influenced each other. These relationships, however, have not always been harmonious. Historically, there have been strong tensions between the Nordic countries, especially the most powerful ones: Denmark and Sweden. Norway and Finland have been somewhat minor political players for many years. After becoming an independent kingdom, Norway formed a union with Denmark that lasted from the fourteenth century until 1814. Norway was then part of Sweden until 1905 when it became independent once again. Finland, by contrast, was a part of Sweden from the Middle Ages until 1809. At this point, Finland became an autonomous grand principality within the Russian Empire and finally gained independence in 1917.

Over time, as the borders and cultural hegemonies shifted within the region, the state power relations changed. The minuet has been a part of the cultural and political ebbs and flows reflecting the unique class relations and cultural models in Norden. However, the minuet is not the first or even the most conspicuous historical example of Nordic dance cultures. Narratives of other old Nordic couple dance forms are more prolific. Although these dances have different names, one name reoccurs in slightly different forms in all Nordic countries: pols (Norway), polsk (Denmark), or polska (Sweden and Finland). The pols(ka) and other related couple dances can be seen as a collective and generative phenomenon amongst Nordic folk dancers, and even as an ‘exportable’ dance form.16 The minuet is described in more specialised narratives, most often connected to specific rural areas in Denmark and Swedish-speaking Finland. However, the minuet also belongs to the contemporary Nordic collective performative space because its Danish, Finnish-Swedish, and Swedish forms are shared by folk-dance enthusiasts across the Nordic countries.

Narratives of dances cannot be separated from the practice of dancing. Where there is dancing, narratives and embodiments encounter each other, generating further practices and narratives. Minuet dancing in Norden has survived for centuries and its discursive and corporeal trajectories have shifted from the European upper classes to the local Nordic peasant communities. Since the twentieth century, Nordic folk-dance communities have danced the minuet both as a performance and participatory dance. Interest in Nordic folk dance even transcends the borders of the region. Multiple Nordic institutions and networks have been working to deepen their understanding of the dances and to build co-operation with enthusiasts in other cultures and countries as well.17

Our book is a witness of the transnationality of the minuet within the Nordic region. As members of a Nordic dance scholar community specializing in folk and historical dances, we take part in the narratives and embodiments of the minuet. We have written about the dance and we have danced its different forms, many of us for several decades. As an anthology of the minuet, the book is a meeting point for our experiences and knowledge of this fascinating dance. It is a testimony we want to share with the rest of the world. In this way, we share the curiosity and passion of de Maupassant about the dance and its dancers as expressed at the end of ‘Minuet’:

Are they dead? Are they wandering among modern streets like hopeless exiles? Are they dancing—grotesque spectres—a fantastic minuet in the moonlight, amid the cypresses of a cemetery, along the pathways bordered by graves?

Their memory haunts me, obsesses me, torments me, remains with me like a wound. Why? I do not know.

No doubt you think that very absurd?18

Chapters

The chapters discuss different phenomena related to the minuet in the Nordic countries and elsewhere from the seventeenth century until the present. Each is divided into five parts covering documentation, research, structure, performances, and revitalisation related to the minuet, emphasising the Nordic forms and contexts of the dance. The authors draw from primary material in several languages and the chapters contain direct quotations as examples. These have been translated into English by the authors themselves unless stated otherwise.

Each author has conducted his or her research individually and thus, despite the fact that all have shared their results with one other, there is inevitably some duplication of sources and information between the chapters. Special attention should be paid to the extensive research of Dr Gunnel Biskop on the minuet, particularly as practised in Swedish-speaking Finland. The texts of Biskop in this book are largely based on chapters in her outstanding monograph Menuetten—älsklingsdansen [The Minuet—The Loved Dance] (2015).19 Several authors in this collection cite the monograph of Biskop and her other texts, since her work covers significant phenomena in the history of the minuet.

The texts in this book do not follow a homogenous approach. They were planned to serve different functions and they aim to target different audiences with their multi-dimensional portrayal of the Nordic minuet. There are chapters following the frames of conventional historiography and presenting excerpts from historical sources in a systematic order with comments and interpretations. These feed into general dance history methodologically and theoretically and provide access to new primary sources. There are also chapters presenting written descriptions of the dance in detail with comments and comparisons. These will be particularly relevant for practitioners working with the reconstruction of historical dances, as will the chapter presenting and applying a specific tool for movement analysis. Finally, some chapters reflect upon seeing the dance from contemporary and philosophical perspectives which aim to highlight the minuet’s position in the early twenty-first century. In this way, we combine the theoretical and methodological approaches with systematic and detailed presentations of historical material that, prior to the publication of this book, has only been available in Nordic languages. We hope this anthology will inspire others to research the minuet and its fascinating history further.

The chapters contain many dance names whose terminology is sometimes complicated. Whenever it is necessary, we explain them as they appear in the text. Most importantly, the term contradance (in French: contredanse) emerges repeatedly throughout the book. The contradances were inspired by English country dances and spread to most parts of Europe and the colonies from the decades around 1700 and onwards. Individual versions of the contradances were invented throughout the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Consequently, they became an important European dance paradigm. They are danced in sets of dancers, with typically four up to sixty individuals in each. The dancing consists of an ever-changing interaction between subgroups of those in the set. The set is usually composed of pairs but interaction can happen between two or more individual dancers, between two or more couples, between a group of ladies or between a group of men. This means that there will always be subgroups of changing size and with changing participants, moving together or in relation to each other within the set.

The first part of the book includes two chapters situating and defining the minuet as a form of dance and music. Egil Bakka and Andrea Susanne Opielka discuss different meanings and functions encompassed in the word ‘minuet’. Bakka examines the possible origin and early relations of the dance in a European context, the use of ‘minuet’ as a name of a dance, and how it correlates with movement structures. He also considers how research on the minuet in the European context compares to research on its Nordic practice. Opielka reviews literature related to European classical minuet music concerning the eighteenth century in particular.

The second part focuses on narratives about the minuet and its contexts in the Nordic countries. Anne Fiskvik sheds light on the activities of dance teachers in relation to the minuet. Then Anders Christensen and Gunnel Biskop look at the rural forms of the dance in Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Denmark since the seventeenth century. Fiskvik, Christensen, and Biskop have spent many years investigating historical sources including letters, diaries, traveller descriptions, and documents from folklore archives. They have consulted this varied selection of sources to paint a picture of the minuet as a versatile phenomenon in Norden over the last three hundred years.

The third part of the book expands the investigation of historical narratives of the minuet in Norden. First, Elizabeth Svarstad and Petri Hoppu jointly discuss multiple examples of descriptions of the minuet in dance books published in the Nordic countries, starting with an overview of the different forms of the dance practised in Europe. Next, Bakka, Svarstad, and Fiskvik use similar documents to discuss the minuet in a European theatrical context. Christensen and Biskop then examine the folkloric documentation of the minuet in Denmark and Finland. The documentation began in the early twentieth century. Christensen investigates three regions in Denmark where the minuet remained important and discusses the kind of information folklorists and folk-dance enthusiasts recorded about the dance. Biskop describes the documentation process in Swedish-speaking areas in Finland, focusing on the extensive written records of Yngvar Heikel from the 1920s and 30s and on the film footage of Kim Hahnsson produced from the 1970s onward. Opielka, Hoppu, and Svarstad conclude this part of the book with discussions of the significance of minuet music in various Nordic contexts and source material of minuet melodies in multiple countries, with a particular emphasis on music books and manuscripts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Various forms and structures of the minuet are examined in detail in the fourth part of the book. The basic form of the early eighteenth-century court minuet, le menuet ordinaire, is detailed in numerous documents ranging from Nordic dancing masters’ manuals to folkloric recordings. These records also contain information about structural variations of the basic form. Biskop discusses the different forms, distribution, and contexts of the dance in the Nordic countries, especially in Finland and Denmark. Hoppu, Svarstad, and Christensen perform a comparative analysis of the steps and basic forms of the minuet, presenting examples that range from the minuet sourced in the eighteenth century to the minuet found in more recent Danish and Finnish folkloric sources. Finally, as a conclusion, Bakka, Svarstad, and Siri Mæland look critically at how minuet structures have been analysed and interpreted in European research. They present new ways of investigating dance structures, utilizing methods including Norwegian movement analysis, svikt analysis, and the principles of triangulation (the combination of various research methods in the study of the same phenomenon). They argue that both svikt analysis and triangulation contribute to a more versatile understanding of the structures of the minuet than results from earlier European dance research which has focused solely on court dances from restricted perspectives.

In the fifth part, the focus shifts to Nordic contexts of the minuet beginning in the early twentieth century. Biskop opens with various examples of the minuet as a living tradition in Swedish-speaking Finland. She describes, for instance, how Ostrobothnian soldiers danced the minuet at the Karelian front during the Second World War. She also examines the significance of the minuet as part of the Finnish-Swedish folk-dance movement today. In Sweden and Finnish-speaking Finland, although the minuet did not have any particular role in twentieth-century dance traditions, disparate groups of folk dancers resurrected the minuet during the latter part of the century in different ways. Anna Björk examines the phases of the reconstruction process and the position of the reconstructed minuet within the contemporary Swedish folk-dance field, while Hoppu attends to recently choreographed minuets practised by Finnish folk dancers. Finally, Göran Andersson and Svarstad discuss the role of the minuet among historical dance groups in Scandinavia and examine how these groups interpret centuries-old documents describing the minuet and how they use these documents as sources of new choreographies.

In the epilogue, Mats Nilsson and Hoppu review the various approaches and perspectives of the chapters and probe the multiple meanings found in the narratives and appearances of the minuet in the Nordic countries. They reflect upon their own embodied experiences and feelings of the dance, as well as its social and cultural contexts, summarising the story of the minuet thus far and anticipating its future.

References

Aron, Leon, ‘A Different Dance—from Tango to Minuet’, The National Interest, 39 (1995), 27–37

Aronsson, Peter and Lizette Gradén, ‘Introduction: Performing Nordic Heritage—Institutional Preservation and Popular Practices’, in Performing Nordic Heritage: Everyday Practices and Institutional Culture, ed. by Peter Aronsson and Lizette Gradén (Burlington: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 1–26

Baker, Eva L., ‘The Dance of Evaluation: Hustle or Minuet’, Journal of Instructional Development, 1 (1977), 26–28

Biskop, Gunnel, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015)

Buckland, Theresa J., Society Dancing: Fashionable Bodies in England, 1870–1920 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)

Dodds, Sherril, Dancing on the Canon: Embodiments of Value in Popular Dance (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)

Hawkes, John and Robert Scholes, ‘A Conversation on The Blood Oranges between John Hawkes and Robert Scholes’, NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, 5 (1972), 197–207

Hoppu, Petri, Symbolien ja sanattomuuden tanssi—menuetti Suomessa 1700-luvulta nykyaikaan (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1999)

Horelli, Liisa, ‘Engendering Evaluation of European Regional Development: Shifting from a Minuet to Progressive Dance!’, Evaluation 3 (1997), 435–50, https://doi.org/10.1177/135638909700300404

de Maupassant, Guy, ‘Minuet’, in Original Short Stories of Maupassant, 13 vols., trans. by Albert M. C. McMaster, A. E. Henderson, Mme. Quesada, et al. ([n. p.]: Floating Press, 2014), x, pp. 1533–38

Moore, David D., ‘A Metabolic Minuet’, Nature, 502 (2013), 454–55

Nilsson, Mats, ’From Local to Global: Reflections on Dance Dissemination and Migration within Polska and Lindy Hop Communities’, Dance Research Journal, 52.1 (2020), 33–44

Sutton, Julia, ‘The Minuet: An Elegant Phoenix’, Dance Chronicle, 8 (1985), 119–52

Vedel, Karen and Petri Hoppu, ’North in Motion’, in Nordic Dance Spaces. Practicing and Imagining a Region, ed. by Karen Vedel and Petri Hoppu (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 1–17

1 The Nordic countries referred to in this book consist mainly of the continental part of the Nordic region: the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, as well as the Republic of Finland, including the autonomous region of Åland. Although the Atlantic islands, the Republic of Iceland, and the Danish autonomous regions of the Faroe Islands and Greenland belong to a Nordic political and historical entity, the minuet has not played any significant role in their cultural histories, and, therefore, these are little discussed.

2 Guy de Maupassant, ‘Minuet’, in Original Short Stories of Maupassant, 13 vols., trans. by Albert M. C. McMaster, A. E. Henderson, Mme. Quesada and others ([n. p.]: Floating Press, 2014), pp. 1533–38 (p. 1537).

3 Maupassant, pp. 1537–38.

4 Julia Sutton, ‘The Minuet: An Elegant Phoenix’, Dance Chronicle, 8 (1985), 119–52 (p. 119).

5 Ibid., p. 120.

6 Ibid., p. 142.

7 Sherril Dodds, Dancing on the Canon: Embodiments of Value in Popular Dance (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

8 Theresa J. Buckland, Society Dancing: Fashionable Bodies in England, 1870–1920 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

9 John Hawkes and Robert Scholes, ‘A Conversation on The Blood Oranges between John Hawkes and Robert Scholes’, NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, 5 (1972), 197–207 (p. 205).

10 Eva L. Baker, ‘The Dance of Evaluation: Hustle or Minuet’, Journal of Instructional Development, 1 (1977), 26–28 (p. 26).

11 Leon Aron, ‘A Different Dance—from Tango to Minuet’, The National Interest, 39 (1995), 27–37 (pp. 36–37).

12 Liisa Horelli, ‘Engendering Evaluation of European Regional Development: Shifting from a Minuet to Progressive Dance!’, Evaluation, 3 (1997), 435–50, https://doi.org/10.1177/135638909700300404 (p. 435).

13 David D. Moore, ‘A Metabolic Minuet’, Nature, 502 (2013), 454–55 (p. 454).

14 Petri Hoppu, Symbolien ja sanattomuuden tanssi—menuetti Suomessa 1700-luvulta nykyaikaan (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1999).

15 Peter Aronsson and Lizette Gradén, ‘Introduction: Performing Nordic Heritage—Institutional Preservation and Popular Practices’, in Performing Nordic Heritage: Everyday Practices and Institutional Culture, ed. by Peter Aronsson and Lizette Gradén (Burlington: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 1–26.

16 Mats Nilsson, ‘From Local to Global: Reflections on Dance Dissemination and Migration within Polska and Lindy Hop Communities’, Dance Research Journal, 52.1 (2020), 33–44 (pp. 38–40). In Norway, these couple dances are called ‘bygdedanser’, a term which includes pols as well as springar, gangar, and halling.

17 Karen Vedel and Petri Hoppu, ‘North in Motion’, in Nordic Dance Spaces. Practicing and Imagining a Region, eds Karen Vedel and Petri Hoppu (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 1–17.

18 Maupassant, p. 1538.

19 Gunnel Biskop, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015) [The Minuet—The Beloved Dance: On the Minuet in the Nordic Region—Especially in the Swedish-Speaking Area of Finland in the last Three Hundred Fifty Years].