10. The Minuet in the Theatre

©2024 Egil Bakka, et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.10

The minuet may well have grown from a theatre choreography based on inspiration and models from various sources. In this chapter we present some examples of minuets created for the theatre, and our aim is to shine some light on how the theatrical versions are related to the ordinary minuet.

In this context, we use the term ‘staged minuets’ to refer to minuets that were performed in front of an audience, whether on a stage in a theatre or at least in an arena, where there is a clear difference between the performers and the audience as opposed to minuets danced in social settings such as balls or dinner parties. Another characteristic of a staged minuet is that it involves some preparation. A choreographer must create or at least adapt the dance for use as part of a performance. Staged minuets imply some rehearsal time, in contrast to social dances, where there may not be defined borders between participants and spectators and where the dance more or less happens in the moment. In social dance occasions, for example, it might not have been decided in advance who will dance with whom or for how long the dance would last.

Choreographed and notated minuets from the eighteenth-century French tradition, like notated dances in general, can be characterized as either ballroom dances or theatre dances. Theatre dances include a more comprehensive vocabulary of steps and more elaborate techniques than those of the ballroom repertoire. In both types, many of the choreographed minuets include elements from the standard minuet: movement patterns resembling some of the usual minuet rounds, the introduction of the circles or the Z-figure, etc.

In a manuscript by Molière entitled Le Mariage forcé, comédie et ballet du Roi, dansé par Sa Majesté le 29* jour de janvier 1664, there is a Menuet pour deux Espagnols et deux Espagnoles [a minuet for two Spanish males and two Spanish females] in the handwritten scores for a divertissement with dance and music to be performed after the comedy has ended.1 Several scholars mention a score from 1664 as the first evidence of the minuet, which may be this one. Hendrik Schultze, however, refers to several minuets from the theatrical context that premiered in 1664 and subsequent years.2 Comédie-ballet is a genre of French drama that, as in Le Mariage forcé, combines acting followed by ballet, many of them written by Molière, with music and dance created by Lully and Beauchamp.3 They reached the peak of their popularity in the second half of the seventeenth century. The most famous, the Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1670), also had a minuet in the second act.

Francine Lancelot has registered only four ballet entrées written in Feuillet notation, which may mean one of several things: that the use of minuet in ballet entrées had decreased by the beginning of the eighteenth century, that already well-known versions were being used, or that ballet entrées were not of interest to the Feuillet notators.

Nevertheless, it seems that the minuet was used extensively in theatre scenes in the middle of the eighteenth century.4 One particular utilization was in the Comédie-ballet, where the dancing came after the theatre part. Another way was to use the minuet as part of the action, in scenes where characters danced the minuet as a part of the narrative. An eighteenth-century genre that used the minuet in this way was the comédies de vaudeville.5 The German music historian Herbert Schneider has edited an exciting article on minuet use in this genre. He mainly discusses the use of minuet airs in vaudeville songs and explains how they are often used in parodic or ironic ways.6

Parodies of older plays are also common. Schneider referred to a parody of Les Indes Galantes and also to other examples of re-presenting old material, such as Le Prétendu [The Suitor], a Comédie-Italienne from 1760. This is a three-act opera with spoken dialogue which imitated Charles-Simon Favart’s 1738 opéra-comique en vaudevilles entitled Le Bal bourgeois. Constant d’Orville described the minuet scene in Le Prétendu as follows :

A wealthy Bourgeois from Paris wants to give his daughter in marriage to a Provincial; this girl loves a young Officer by whom she is loved ... Arrives her dancing master, followed by the young lover ... our two lovers sing to the tune of their minuet that they still continue to dance, some verses on the embarrassment in which they find themselves. Finally, the father surprises the lover at the feet of his daughter ... Even if this scene resembles perfectly the minuet of the Opéra-comique, the Bourgeois Ball that is so famous, it was nonetheless applauded.7

In his article, Schneider provided many examples, noting characteristics of the minuet as used in theatre in the mid-eighteenth century. Although his interest in the minuet was largely musical, he also referred, at times, to the dance. For example:

‘Minuet scenes,’ as discussed below, cover various stage actions. Still, all rely on the dance concept to convey their different local meanings, which are connected principally with the idea of youthful love, either naive or ironic, and sometimes that of seduction. The signifier is the dance style itself, irrespective of the precise melody selected. It is worth emphasising how different this mode of dramatic communication was from the conventional method of parodying texted melodies […].8

It would be interesting to see a more in-depth study of the relationship between the minuet as a social dance and as a staged dance through the eighteenth century, particularly one focused on differences of class and source material. Newspaper articles as well as letters and memoirs from the period that refer to balls are the most likely sources from which to glean an impression of how frequently the minuet was used in a social context. Texts for theatre plays and even other fiction literature, however, may tell us more about the attitudes to the dance and how it is used to signal class distinction. Such a study might give us a better understanding of why the minuet declined: did it fall from favour because of the French Revolution, or were other mechanisms at play?

Two Examples on Choreographed Minuets in

Feuillet Notation

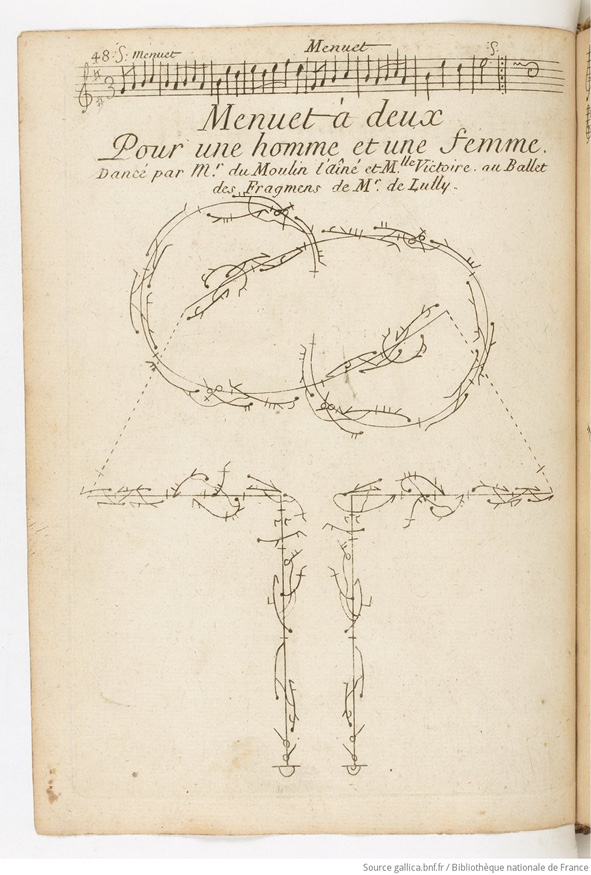

The Menuet à deux [Minuet for two] is a couple dance for a man and a woman choreographed by Guillaume-Louis Pécour (1653–1729) and performed by the characters Mr. de Moulin l’Aîne and Mlle. Victoire in the Ballet des Fragments de Mr. de Lully.9 With a prologue and five parts, the opera-ballet was composed by André Campra (1660–1744) and was first performed in Paris in 1702.

The music for the Menuet à deux is written in 3/4 time, and the Feuillet notation of the dance shows the bar lines corresponding to the 3/4 time. The tune has 32 bars, which implies a duration of only sixteen minuet steps since each step of a minuet takes two bars of music. For the first four bars, the dancers mirror each other, but, from the fifth bar onwards, the choreography changes to comprise only minuet steps and the contretemps du menuet.

Fig. 10.1 Menuet à deux [Minuet for two]. A page displaying Feuillet notation. Gallica Digital Library, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b85914682/f62.item.r=recueil%20de%20dance%20pecour/f62.jpeg, public domain.

Before the dance starts, the dancers stand side by side, facing the front of the room. During the first step of the dance, they turn to face each other and perform a pas de gaillarde. They start this step with opposite legs, which means that the man begins on his right foot, and the lady on her left foot. While keeping the same direction, they do two balancés: one forward towards each other and one backwards away from each other. To continue the choreography, starting each step on the right foot, the man stays on the left leg while the woman adds a step backwards on the left foot. The following steps are minuet steps in different directions combined with contretemps du menuet forward and backwards. The dancers begin in place and then move away from each other, first in a clockwise circle towards one another and then on the same line; the lady comes forward and the man moves backwards before they change and perform the same steps in the opposite direction: the man comes forward and the lady moves backwards; when they have finished, they end the dance by changing places: performing two minuet steps turning around each other and returning backwards to their original places doing one contretemps and one minuet step.

This choreography has the qualities of the standard minuet in both the combination of steps and, to a certain extent, the figures, showing some characteristics of the minuet’s fixed figures. Simultaneously, the choreography plays a bit more with the music and has more advanced steps than the standard minuet which usually consists primarily of the basic steps of the minuet.

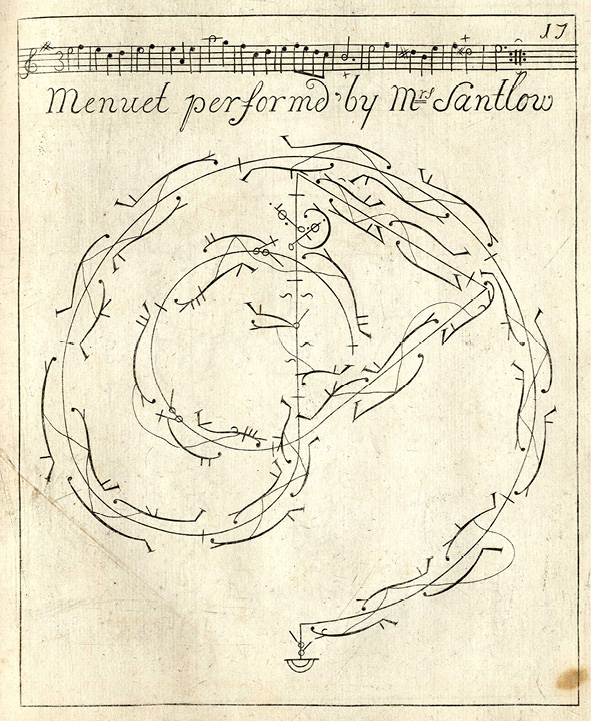

Another example of a theatre minuet is the Minuet perform’d by Mrs. Santlow, choreographed by Antony L’Abbé (c.1667–c.1756) in 1725.10 This minuet is a solo dance for one woman, and with its ninety-six bars of music, it is much longer than the Menuet à deux. Its choreography also differs from the Menuet à deux in the number of different steps. Also, it contains many more minuet steps. For example, the choreography starts with a dancer performing six minuet steps in a large circle counter-clockwise around the room. This circle resembles the standard minuet’s introduction figure. It establishes some of the minuet’s characteristics in both the floor pattern and the steps before the choreography develops into a more elaborate and advanced variation on the minuet theme. L’Abbé’s choreography includes minuet steps in different variations and directions, contretemps and balancés, pirouettes and turns, jetés and other jumps, and quite a lot of flourishes with the legs, such as quick steps performed in double tempo to the music, circling of the leg, and lifting one foot off the floor. Such elaborations demand strong technique and agility and show a minuet elevated some levels beyond the ordinary and ballroom varieties.11

Fig. 10.2 Minuet perform’d by Mrs. Santlow. A page showing the

choreography. OpenEdition Journals, https://journals.openedition.org/danse/docannexe/image/343/img-1.jpg, public domain.

The Minuet on the Nordic Stage

One theatrical arena where the minuet was included was the vaudeville or light opera. Henning Urup has studied some examples from plays that include the minuet as both music and dance during the second part of the eighteenth century and the first part of the nineteenth century. Two plays by Ludvig Holberg (1684–1754), the Mascarade and the Kilde-Reysen, include minuets. Fiskerne by Johannes Ewald (1743–1781) also contains minuets.12

A later example of the minuet in the theatre is the dance included in the play En Caprice by the Danish playwright Erik Bøgh (1822–99). The play was hugely popular in Christiania (Oslo) around 1860 when the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906) was the director at the National Theatre. Two of the play’s characters are a female Spanish dancer and a dancing master or, rather, a parody of a dancing master. In one scene, he and the dancer discuss their dancing skills. One of the dances they talk about is the minuet, and she performs one for him. The play also includes a Spanish dance and the Norwegian halling. Some have wondered why En Caprice, a relatively simple play, became so popular. Elizabeth Svarstad and Jon Nygaard, theatre historian at the University of Oslo, suggest that some of the play’s appeal can be explained by its inclusion of the dances. Since the minuet was well known to the theatregoers at the time—it had been almost an obligatory part of their education—the audience might have engaged with the play and the familiar dance repertoire. Invoking a kinaesthetic experience from the spectators’ youth allowed them to enjoy the play on several levels.13

The Elverhøj Minuet

The ‘Elverhøj minuet’ is a choreographed minuet created in 1828 for the play Elverhøj, but it became so popular that it continued to be danced outside of its original theatrical context for a very long time. Johan Ludvig Heiberg (1791–1860) wrote the libretto for Elverhøj, and Friedrich Kuhlau (1786–1832) composed the music. The choreographer, Poul Funck (1790–1837), was a solo dancer at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen.14 The play held the status as Denmark’s national play for many years, and it has been performed at the Royal Theatre more times than any other play.15

Funck was born in Copenhagen and started at the Royal Ballet when he was eight years old, remaining there for all of his life. He was one of the more recognized dancers of the period and would have danced the minuet under the supervision of balletmasters such as the French master Antoine Bournonville (1760–1843). With Bournonville in this position, there was no break in the cultural stream connecting the minuet of French court ballet to the Royal Ballet in Copenhagen. In other words, Funck learned choreography that retained the characteristics of the older minuet forms. The Royal Ballet is known for its unbroken transmission of repertoire from the eighteenth century, which it facilitates by having new dancers learn the dances from their seniors. Similarly, the minuet in the play Elverhøj is connected by an unbroken chain of transmission in the theatre/ballet environment from the French court minuet. Elverhøj was first documented on film in 1939, and the film shows that the step patterns are different from most versions of reconstructed minuet and align with svikt (the up and down movements) in the Nordic folk minuet.

The Elverhøj Minuet in Norway

The play Elverhøj was also performed in Norway. Two examples of newspaper advertisements show one performance was held in Kragerø in 1885 and the other in Christiania, in 1905. In both advertisements, the play’s dances are mentioned explicitly, which may indicate their great popularity as that which would attract audiences to buy tickets.

The performance in Kragerø is also described in text next to the advertisement. This describes Elverhøj as a beautiful romantic play that has had great success. The costumes, like the dances, are deemed extraordinary: ‘A group of young girls performed beautifully one dance while the whole ensemble performed two dances, a garland dance and the minuet, in the play’.16

On 28 November 1905, Elverhøj was performed in Christiania as a gala performance to celebrate the new king of Norway. Although almost a hundred years after its premiere, the play was chosen for this honour, perhaps, because it had originally been composed and created for the wedding of prince Frederik; who was to become king Frederik VII of Denmark, and princess Vilhelmine.17

The dances are also mentioned in the 1905 newspaper advertisement, but in contrast to the 1885 advertisement, two dancers are mentioned by name. This information may imply that the dancers, Fru Marquard Mikelsen and Hr. Danselærer Mikelsen, were the choreographers of the performance and perhaps also the dancers.

The Elverhøj Minuet in the Twentieth Century

The choreography for the Elverhøj minuet became very popular with dance teachers in Denmark.18 It is included in the dance instruction manual Lærebog i ældre danse [Textbook of Old Dances] published in Copenhagen in 1952. The book contains instructions for a range of different dances, such as couple dances, quadrilles, dances for children, and so-called older dances’. The Elverhøj minuet description in this manual shows a dance for ten couples and contains an introduction, a middle part of four minuets, and a conclusion. The steps in the dance are minuet steps, coupé, assemblé, polonaise steps, balancé, and a so-called menuet-balancé.

Fig. 10.3 The dancers in Elverhøi, at Friluftsteatret, an open-air stage at Bygdø in Oslo, constructed specifically for a performance that premiered on 16 June 1911. Photograph by Rude og Hilfling, Nasjonalbiblioteket, https://www.nb.no/items/274f0e2b6e15090b655256118a6f88a2?page=0&searchText=Elverh%C3%B8i, public domain.

The minuet step is explained as a step consisting of four steps: one long and three short. It takes two bars and counts six beats. The forward step is performed by doing a coupé with the right foot forwards to the fourth position. Step forward on the first part of the bar and rest on the second and third part of the bar. Then walk three small steps on the toes left, right, left. Then lower the left heel by the end of the last step.19

The coupé is described as ‘after a bending (on the upbeat), in both knees, one foot glides from the first to the fourth position forward or backward, the weight transfers immediately to the other foot’.20

The minuet step to the side is explained as a coupé beginning with the right foot to the side in second position, moving the left foot behind the right foot in fifth position on demi-point, moving the right foot a short step to the right on demi-point, and placing the left foot behind the right foot in fifth position on demi-point, and finally lowering the heels by the end of the step, keeping the weight on the left foot.

The minuet balance (‘Menuet-Balancé’) is explained as the dancer taking a gliding step with the right foot forward in the fourth position and transferring the weight to the right foot on the first count. Then the left foot is pulled to the third position behind and rises on the second count. On the third count, the dancer lowers and marks a light step on the right foot. The second part of the step is performed by gliding the left foot backwards to the fourth position on the fourth count and on the fifth and sixth count, closing the right foot in third position while raising, lowering and marking a light step on the left foot.21 This step resembles the pas balancé described by Pierre Rameau and other dancing masters.

The right minuet is explained as minuet steps to the side twice and is counted to twelve, i.e., four music bars. The left minuet is likewise counted to twelve and is explained as gliding the right foot forward to the fourth position on the first count and resting on the second while pulling the left foot loosely to the third position behind. On the fourth count, the dancer walks sideways on the left demi-point, placing the right foot behind the left foot in the fifth position on the demi-point, and on the sixth count, stepping to the side on the left, first on the toe and then on the whole foot.

The second part of the left minuet is explained as the dancer swinging the right foot behind the left foot in the third position with light bending in both knees on the seventh count. On the eighth count, the performer stretches the knees and rises on the toes, lowering on the ninth count. Then on the tenth count the dancer steps to the side again on the left foot on demi-point, on the eleventh, they place the right foot behind the left in the fifth position on demi-point and on the last count the dancer walks to the side on the left foot, first with the toe then the whole foot.22

The full minuet (Hel-Menuet) is explained as a compound figure, consisting of one right minuet and one left minuet, which takes eight bars of music.

The half minuet (Halv-Menuet) is also a compound figure consisting of a minuet step to the side on beats 1 to 6, one coupé to the side on the right foot on count seven and eight, and on count nine a 1/8 turn to the left, pulling the left foot towards the right foot in the first position and bending both knees. The three last counts of this figure are completed by gliding the left foot backwards to the fourth position, then on the eleventh count, the weight is transferred to the back leg, and on the last beat, both knees stretch but leaving the right foot in front and tapping the right toe in the fourth position, and at the same time lifting either the left arm or both hands forward toward the partner.23

Farmers and Ballet Students

There are some examples of the Elverhøj minuet having been performed in Norway in the social, not staged, context. In a description of a Christmas ball in 1909, it is mentioned as a formal dance that was performed after several ballroom dances including country dances, feier, English dance, figaro, and the waltz. After these dances, the young people had to leave the floor, and the older people took their positions. Simultaneously, the musician stood up with a certain stateliness and intonated the minuet from Don Juan or Elverhøj. The minuet they danced is described as so correct and so elegant that one would not think that those who were dancing were farmers.24

A search in the database of the Oslo Museum returns a hit of a photograph with the inscription ‘Menuet av Elverhøj’ written on the back.25 It is dated 1916 in Harstad, Norway. The photo shows ten young girls dressed in rococo costumes, all in the same pattern and seemingly made of the same fabric. The hair is done neatly according to eighteenth-century hairstyles.

Fig. 10.4 Den Nationale Scene ‘Elverhøj’, 1926. Photograph by Selmer Malvin Norland. Oslo Digital Museum, https://digitaltmuseum.no/021018379137/den-nationale-scene-elverhoi, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The position of the dancers shows six dancers on the first row and four on the second row. They are standing two by two, slightly turned away from each other with their backs touching. The position resembles that of the description of the Elverhøj minuet in the Textbook of Old Dances.

Concluding Remarks

In this chapter, we have tried to reconstruct the role of the minuet in the theatre from the seventeenth to the twentieth century. The theatre, rather than the ballet, repeated references to the minuet for a very long time. In the eighteenth century, older theatre pieces were often remade in the form of a parody. Often, when the original play included a minuet, this dance scene was retained in the new version. We described the remaking of the minuet for the stage through such versions as the Menuet de la Reine and the Menuet de la cour, and then Menuetten af Elverhøj, a Danish choreography for a classic romantic theatre play which also became famous in the Nordic countries. These references, which are still repeated in theatre produced in the twenty-first century, have extended the aura of the minuet far beyond the time the menuet ordinaire was a social dance in towns and cities in the Nordic countries. Several of the theatre choreographies also transcended the theatres and were taken up in more or less social contexts by dancing masters or amateur performers and, even later, in historical dancing.

This chapter presented examples selected from a much larger body of sources. We hope that, though brief, it illustrates some key features of the theatre minuet. A more thorough investigation would likely reveal more interesting aspects concerning the staged minuet and paint a fuller picture. Such work is time consuming and demanding in terms of archival work and searching for information. Many sources, such as librettos, for example, contain information about the dance, or the dancers. Very often, however, the information given is sparse, only mentioning that ‘they dance’.

References

Auken, Sune, Knud Michelsen, Marie-Louise Svane, Isak Winkel Holm, and Klaus P. Mortensen, Dansk litteraturs historie, Bind 2, 1800-1870 (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 2008)

Buelow, George J., A History of Baroque Music (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2004)

Charlton, David, ‘“Minuet-Scenes” in Early opéra-comique’ Timbre und Vaudeville. Zur Geschichte und Problematik einer populären Gattung im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, ed. Herbert Schneider. Hildesheim, 1999 in French Opera 1730–1830. Meaning and Media, edited by David Charlton (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), pp. 156–291

Feuillet, Raoul-Auger. Recueil de dances (Paris: [n. pub], 1704).

Fournier, Narcisse, Le Menuet de la Reine: Comédie-Vaudeville en deux actes. Représentée, pour la première fois, sur le théâtre du Gymnase-Dramatique, Le 27 Janvier 1843 (Paris: Imprimerie de Ve Dondey-Dupré, 1843)

Holter, Wilhelm, ‘Erindringer om mitt liv’, in Gausdalsminner, 4 (Lillehammer: Gausdal historielag, 1991), pp. 62–84.

Kiss, Dora. ‘Interpréter “le Menuet performd’ by Mrs. Santlow”’, in Recherches en danse, 2 (2014), [n.p.], http://journals.openedition.org/danse/343, https://doi.org/10.4000/danse.343

L’Abbé, Anthony, A New Collection of Dances (London: Le Roussau, 1725; repr. London: Stainer & Bell, 1991)

Lærebog i ældre danse. Utgivet af Danse-ringen (København: P. Hansen’s Bogtrykkerie, 1952)

Molière, Despois, Eugène and Paul Mesnard, Oeuvres de Molière, vol. IV (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1878)

Mortensen, Klaus P., and May Schack, eds, Dansk litteraturs historie (København: Gyldendal, 2006–2009)

Schou-Pedersen, Jørgen, and Henning Urup, ‘Menuet’, in Den Store Danske (København: Gyldendal, 2009), https://denstoredanske.lex.dk/menuet

Schulze, Hendrik, Französischer Tanz und Tanzmusik in Europa zur Zeit Ludwigs XIV: Identität, Kosmologie und Ritual (Hildesheim: Olms Verlag, 2012)

Sivertsen, Kim, ‘På Gausdalsvis’, Bladet Folkemusikk, 9 March 2011, https://folkemusikk.custompublish.com/paa-gausdalsvis.4895864.html

Svarstad, Elizabeth, and Jon Nygaard, ‘A Caprice—The Summit of Ibsen’s Theatrical Career’, Ibsen Studies, 16.2 (2016), 168–85

Urup, Henning, Dans i Danmark—Danseformer ca. 1600 til 1950 (København: Museum Tusculanum, 2007)

Vestmar, no. 48, 25 April 1885. The National Library of Oslo, https://www.nb.no/items/c1c472265b8ef53d0d86499f6e95a433

1 Molière, Despois, Eugène, Mesnard, Paul, Oeuvres de Molière, vol. IV (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1878).

2 Hendrik Schulze, Französischer Tanz Und Tanzmusik in Europa Zur Zeit Ludwigs XIV: Identität, Kosmologie Und Ritual; Hildesheim (Olms Verlag, 2012).

3 George J. Buelow, A History of Baroque Music (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2004), p. 169.

4 David Charlton ‘Minuet-Scenes’ in Early Opéra-comique Timbre Und Vaudeville. Zur Geschichte Und Problematik einer Populären Gattung Im 17. Und 18. Jahrhundert, ed. Herbert Schneider. Hildesheim, 1999’, in French Opera: 1730-1830: Meaning and Media, ed. by (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), pp. 156-291,

5 Narcisse Fournier, Le Menuet de la Reine: Comédie-Vaudeville en Deux Actes: Représentée, Pour La Première Fois, Sur Le Théâtre Du Gymnase-Dramatique, Le 27 Janvier 1843 (Paris: Imprimerie de Ve Dondey-Dupré, 1843); Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, Le Menuet de Danaé: Comédie-Vaudeville En Un Acte (Paris: Beck, Libraire, 1862).

6 David Charlton ‘Minuet-Scenes’ in Early Opéra-comique.

7 Ibid., p. 258.

8 Ibid., p. 259.

9 Raoul-Auger Feuillet, Recueil de dances (Paris : [n. pub.], 1704), 48–50.

10 Anthony L’Abbé, A new collection of dances (London: Le Roussau, F., 1725; repr., London: Stainer & Bell, 1991), pp. 17–21.

11 Still, the minuets may have been danced in a ballroom, as a common practice was to adapt dances from the stage to the ballroom in simplified versions. For an analysis of the Menuet Santlow, see Dora Kiss, ‘Interpréter “le Menuet performd’ by Mrs. Santlow”’, Recherches en danse, 2 (2014), http://doi.org/10.4000/danse.343

12 Henning Urup, Dans I Danmark: Danseformerne ca. 1600 til 1950 (Københavns Universitet: Museum Tusculanums Forlag, 2007), p. 132.

13 Elizabeth Svarstad and Jon Nygaard, ‘A Caprice—The summit of Ibsen’s theatrical career’, Ibsen Studies 16.2 (2016).

14 Urup, p. 153.

15 Sune Auken, Knud Michelsen, Marie-Louise Svane, Isak Winkel Holm, and Klaus P. Mortensen, Dansk litteraturs historie, Bind 2, 1800–1870 (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 2008), pp. 280–82.

16 Vestmar, no. 48, 25 April 1885, https://www.nb.no/items/c1c472265b8ef53d0d86499f6e95a433

17 Auken, etc., pp. 280–82.

18 Jørgen Schou-Pedersen and Henning Urup, ‘Menuet’, in Den Store Danske (København: Gyldendal, 2009), https://denstoredanske.lex.dk/menuet.

19 ‘HF en Coupé frem i 4. Position, der trædes frem paa 1. Taktdel og hviles paa 2. og 3. Taktdel. Gaa 3. smaa Trin paa Taa VF., HF., VF., sænk v Hæl i Slutningen af sidste Trin’. Lærebog i ældre danse. Utgivet af Danse-ringen (København: P. Hansen’s Bogtrykkerie 1952), p. 27.

20 Ibid., p. 26.

21 Ibid., p. 27.

22 Ibid., p. 28.

23 Ibid. Dance teacher Elizabeth Svarstad bought a copy of this book from a Danish second-hand bookshop in 2007. Its first owner had been Olga Jensen, a Danish dance teacher in the middle of the nineteenth century. Jensen had written her name on the first page of the book (together with the name ‘Fredericia’ and the date, 7 September 1952).

24 ‘Saa maatte ungdommen av gulvet, og de gamle stillede sig opp, medens Morten Døivingen strammede seg opp med en vis høitidelighet og intonerede menuetten af Don Juan eller Elverhøj. Og saa begyndte en dans så korrekt og elegant, at man ikke skulde tro, det var bønder som traadte den.’ Kim Sivertsen, ‘På Gausdalsvis’, in Bladet Folkemusikk, 9 March 2011, https://folkemusikk.custompublish.com/paa-gausdalsvis.4895864.html; Holter, Wilhelm, ‘Erindringer om mitt liv’, in Gausdalsminner, 4 (Lillehammer: Gausdal historielag, 1991), pp. 62–84 (p. 81).

25 ‘Gruppebilde av unge dansere eller skuespillere’ [‘Group picture of young dancers or actors’], Digitalt museum, https://digitaltmuseum.no/021018440293/gruppebilde-av-unge-dansere-eller-skuespillere/media?slide=0.