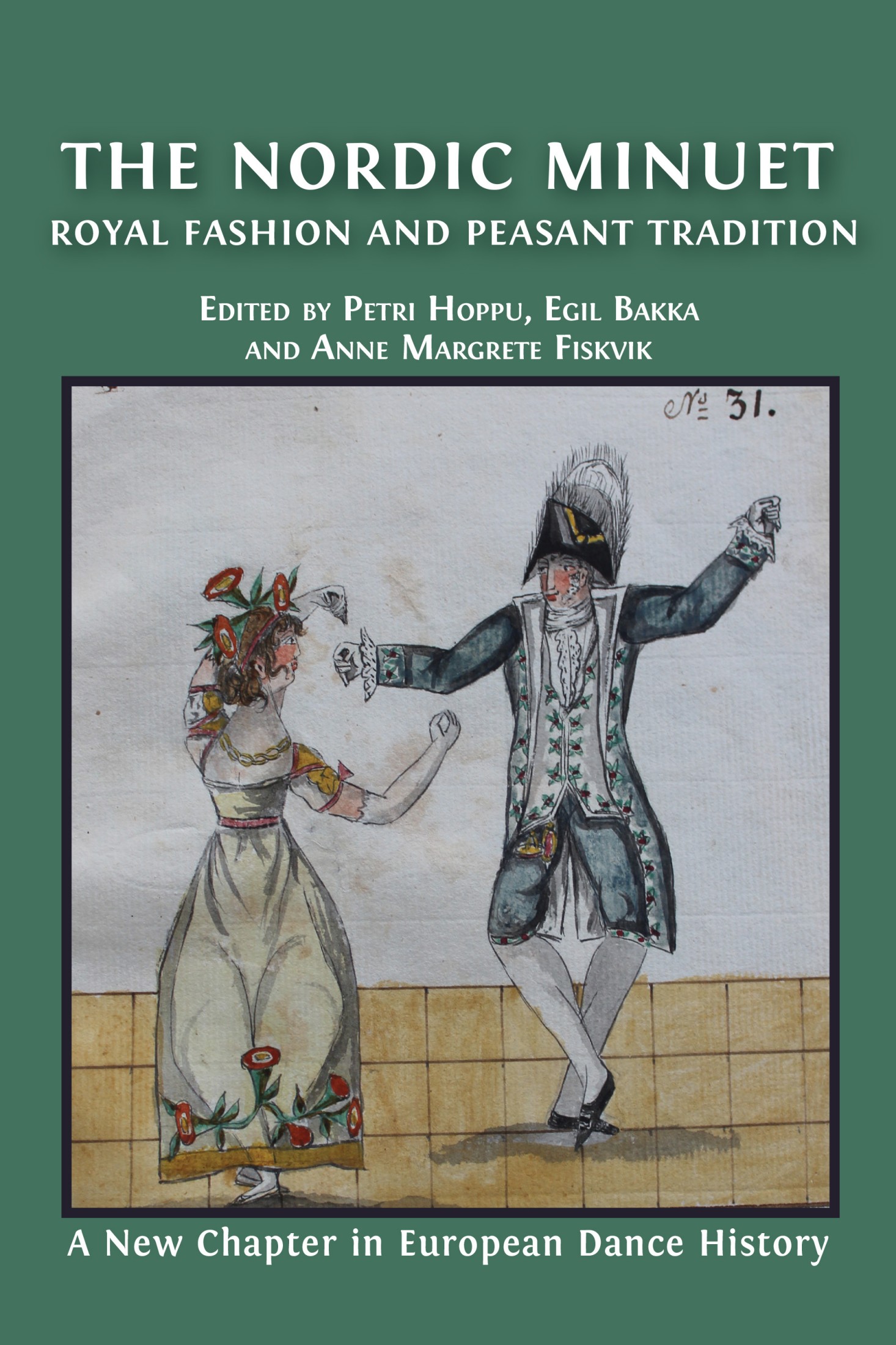

11. Collecting Minuets in Denmark in the Twentieth Century

©2024 Anders Chr. N. Christensen, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.11

In Denmark, minuet traditions were preserved in some parts of the country until the twentieth century. From the beginning of that century, examples were documented from three regions: the island of Ærø, islands of Lolland and Falster, and Randers region in Jutland. In the islands, several dances called minuets were documented at the beginning of the twentieth century. In Randers region, documentation started in the 1930s and continued sporadically until the 1980s. Danish minuets have been published in several folk-dance manuals, and many of them remain an active part of Danish folk dancers’ repertoire today. Lolland and Falster are the southernmost isles south of Sealand. As the islands were relatively isolated in earlier centuries, many traditions stayed alive until the beginning of the 1900s. A bridge to Sealand was not built on Falster until 1937.

The Mollevit from Ærø

The collection of folk dances on Ærø has, to a great extent, been focused on the Rise parish at the centre of the island, where the ancient dances have been best preserved. The farmer and fiddler Hans Andersen Hansen (1861–1953) and his family played a crucial role in maintaining the traditional minuet ‘mollevit’ on Ærø.1

The Grüner-Nielsen Collection on Ærø

The first time the island was visited by folk music and dance collectors was in 1918, when the archivist Hakon Grüner-Nielsen (1881–1953) and his wife Ellen made an extended trip in August and September which included a visit to Ærø for the purpose of collecting examples.

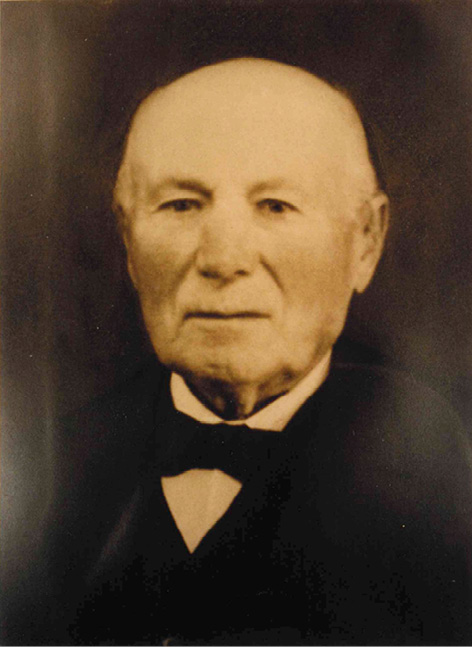

Fig. 11.1 Ellen Grüner-Nielsen was the first in Denmark who attempted to describe a popular minuet on Ærø. Photograph by Julie Laurberg Gad, København (1918). © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

There, the Grüner-Nielsens encountered the ‘mollevit’, the traditional name for the minuet on Ærø. Theirs was the first effort in Denmark to document a surviving version of the baroque minuet. In a fair copy of the record from the year 1918, Ellen Grüner-Nielsen described the collection on Ærø:

Here we were so lucky to start in St. Rise and were shown to the farmer Hans Andersen, about 60 years old, who proved to be one of the best sources we could get. Both he and his wife helped us; she danced with me, he played, and my husband wrote melodies not written down. [...] I was with them at least three times on afternoons and evenings and had to go in vain several times.2

However, they found the ‘mollevit’ was not so easy to record, as she explained: ‘I had to use an amount of time to note it down, and it may be because when noting it, it possibly could be done much simpler and more manageable.’3

Ellen Grüner-Nielsen postulated that this might have been because she herself could not perform the minuet in the way it had been taught in the dance schools. When Ellen Grüner-Nielsen wrote down the dance, she had to dance with Hansen’s wife, while Hansen played along.

Once they showed me enough (my husband played), they both danced with much grace (he in clogs), but there were so many steps to notice that I did not get a real overview. I thought myself, that I did the steps precisely as they did, but probably there was a nuance in the beat or the movement that was different; they said the whole time that I had not the right step.4

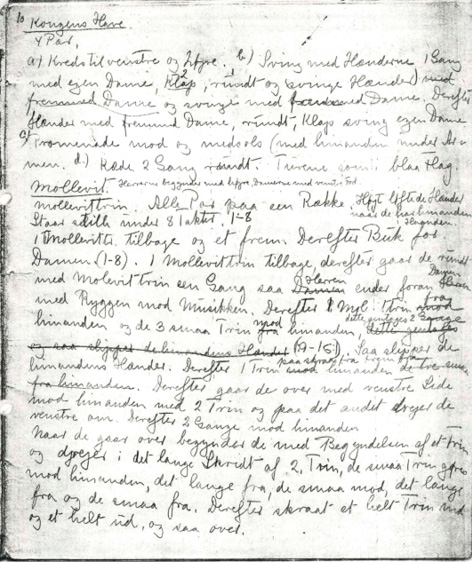

Fig. 11.2 Ellen Grüner-Nielsen’s original draft records of the Mollevit from Ærø, collected August–September 1918. This instance is the first time in Denmark anyone recorded a popular minuet. Det Kongelige Bibliotek DFS 1915/004 Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

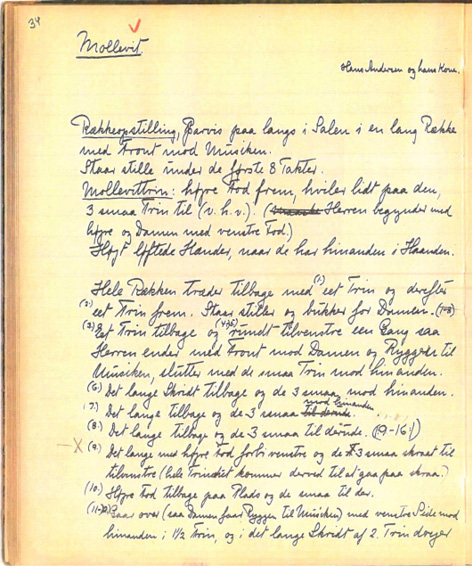

Fig. 11.3 Ellen Grüner-Nielsen’s transcription from 1930 of the Mollevit from Ærø, recorded in 1918. The photo shows only the first page of the description of the mollevit. Dansk Folkemindesamling ved Det Kongelige Bibliotek, DFS 1915/006, Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

Besides the mollevit, Ellen Grüner-Nielsen documented a ‘Foredance’, which, in ancient times, was danced after the mollevit when ‘they should have a speedy one’. Her description explained: ‘They swung their lady, then they went in the chain to the next lady, and every lady would then kiss the musicians and then her partner and such it went all the way around’. This dance disappeared in the mid-1800s. It is probabe that it is a remnant of an old Polish dance or even a foredance to a Polish dance. In addition, at one time, a dance called ‘Mollevit 3’ was in existence. Hansen reported that he had seen it danced in his earliest childhood in the late 1860s but that, when he started gigging in 1870, it had passed out of use. He did not remember the music for the dance, but he explained it as a row dance where each man had two partners. Thus, as early as the mid-1800s, there were only a few people remaining who could dance the ‘Mollevit 3’.5

The Mollevit as a Ceremonial Dance

In the last half of the 1800s on Ærø, a strong emphasis was placed on the wedding couple learning to dance the mollevit prior to their wedding. The mollevit belonged to the ceremonial class of dances at weddings on the island. The dance took place in a large living room after dinner; when the room was emptied of furniture the musicians got ready and took seats in the corner. Shortly after that, the tones signalling the start of a mollevit sounded. At this point, the two best men and two closely related females led the wedding couple into the large living room. If the best men were the fathers of the bride and groom (as was often the case), they and their wives would dance the first dance alongsidethe bride and the groom.

The bridal mollevit was danced by three couples with the wedding couple in the middle who received the most attention from the guests. Since it was customary for every young or old guest to have a turn dancing with the bride and groom, individual mollevits might be fairly short. Several records contradict this account, however, describing the bridal couple as dancing on their own. 6

The mollevit had ceremonial significance not only at weddings but also at Shrovetide riding, which ended with dining and dancing. The following description is from 1900:

The first dance—the Minuet, the favorite dance of the Ærø residents—was danced by the King and Queen alone. In the second dance—a waltz—servants and outriders participated.—Hereafter, all who wanted to dance could do so.7

In the late 1800s, the bridal mollevit was replaced by a wedding waltz, a tradition that shifted across the whole country. On Ærø, various melodies were used for the waltz. Hansen reported habitually performing a melody called ‘Kirsten’s Waltz’. Although the mollevit had ceased to be a ceremonial dance at weddings by the early 1900s, it retained a high status. It was danced at all the major parties in the Rise parish. The mollevit was danced a short time after the wedding waltz and continued to be one of the highlights at weddings.8

Fig. 11.4 The musician Hans Andersen Hansen and his wife Anne Hansen, photographed together with children and children in-law, were eager dancers and all of them could dance the mollevit (minuet). The family is photographed at the occasion of Anne and Hans Andersen Hansens’s Diamond Wedding on 21 July 1941. In the middle of the picture the diamond wedding couple, and the fourth man from the left is the son of the wedding couple, Jens Hansen, who was also a front dancer in the mollevit for many years. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

The mollevit continued to be danced in the 1930s and into the 1950s, but as the older generation, having danced the mollevit from their earliest childhood, disappeared, it became more challenging to implement. In several instances, many people wanted to dance the mollevit and lined up on the floor but were not confident enough to actually go through with it. After dancing only a little while, things fell apart, and the dancers stood discussing what had gone wrong. As late as the 1970s, musicians were asked to play the mollevit at a private party, but the dance could not be completed even this time. It all dissolved, and the dancers stood discussing in the middle of the floor.9

Kjellerup Records the Mollevit in 1939–40

In 1939–40, more than twenty years after the Grüner-Nielsens’ collection excursion to Ærø, Ane Marie Kjellerup, from Nyborg, also visited the island to record old Ærø dances including the mollevit. Kjellerup must have been unfamiliar with the earlier report where Ellen Grüner-Nielsen wrote:

Many of the dances [on Ærø] are so difficult that a follow-up collection, such as the one the FFF’s collectors later introduced [by coming several years in succession] could have been greatly desirable; but perhaps it can be done yet.10

However, Kjellerup had an advantage: having attended Paul Petersen’s dance school in Copenhagen, she already had practical and theoretical training as a dance teacher and some musical knowledge. She quickly connected to the folk-dance movement, but her actual collection of folk dances began with only a small number of dances that she was able to record in various places on Fyn. Her trip to Hindsholm in the northeast of Fyn in 1933, however, yielded a fine collection of dances that became the basis of her collection work.11

Kjellerup established a connection to the dancers and to Hansen on Ærø through a good friend who had been raised on the island. This friend brought together Hansen and four couples of dancers in Dunkær in Rise. All were exceptionally good dancers who used the dances when they met at parties in Rise. Her friend’s relationship with the local population was of great importance. Kjellerup was convinced that without this assistance, the collection would not have been successful because it otherwise would not have been not easy to gain access to the daily lives of the residents on Ærø.12 During her vist, Kjellerup recorded nine dances, which she published in the Association for Folk Dance Promotion’s regional booklet, entitled Old Dances from Fyn and the Islands (1941).13

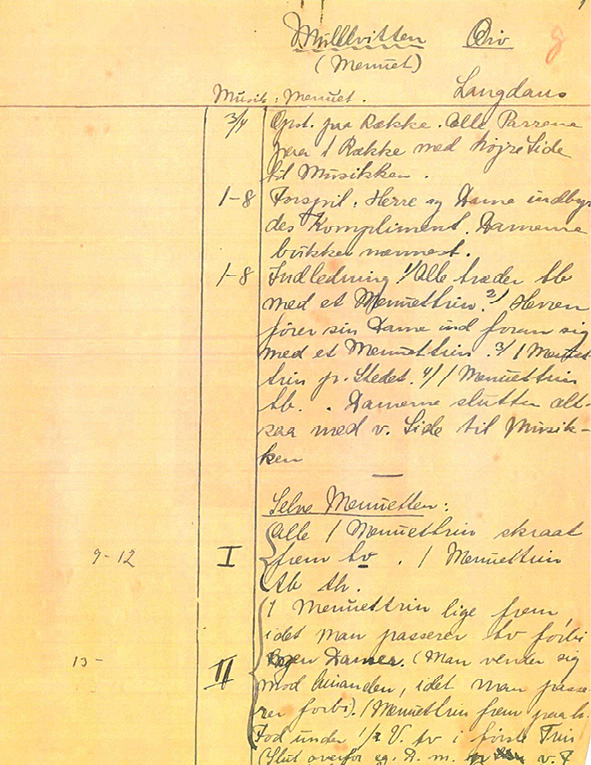

Fig. 11.5 Front page from Ane Marie Kjellerup’s original recording of the Mollevit from Ærø 1939–43. Dansk Folkemindesamling ved Det Kongelige Bibliotek 1915/006, Kildematerialet til Gamle danse fra Fyn og Øerne 1941. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

Among the dances she documented were ‘Mollevit’, ‘Contra with Mollevit’ and ‘The One with the Gap’. The latter two were quadrille dances with minuet performed to the last two repetions of the music, which the residents of Ærø called ‘Half Mollevit’. Other written sources show that dances with minuet as the two last figueres were practised in Europe from the second half of the 1700s. With great skill, Kjellerup managed to document the steps, figures, and progress of the minuet and the two quadrilles with a minuet, which was not an easy task. She was the first Danish folk-dance collector to present a traditional minuet, the mollevit, in print.14

When the first edition of Old Dances from Fyn and the Islands sold out, and republication was planned in 1949, the Association for Folk Dance Promotion (Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme) wanted to revise the booklet. Small uncertainties had arisen about how the mollevit was to be danced. Therefore, the Association decided to send Svend Clemmensen, from its description commission, to Ærø to find answers.

The trip was intended to be on October 14-15, 1948. Clemmensen and Hans Nielsen from Hjallese at Odense travelled together. On 14 October, they were to visit the folk-dance association Vippen in Marstal, and the next day they would seek out Hansen, who at that time was eighty-nine years old and lived with his son in Rise.15 When Clemmensen and Nielsen arrived at the house, Hansen’s daughter-in-law told them that the old one was taking a nap. When Hansen awoke, the pair explained their errand. Before long, Clemmensen and Nielsen were dancing to the tunes from Hansen’s violin. At the point in the dance at which the rows swap positions, however, Hansen cried, ‘No’. He could not say what was wrong about their dancing, only that it was wrong. They tried several more times, but nothing helped. They got a ‘no’ each time. Determined to help, Hansen inquired, ‘When do you leave?’. The reply was ‘Not until we have clarity about the mollevit.’ Hansen asked his daughter-in-law to call other elderly dancers and ask them to join him the Dunkær Inn at eight o’clock that evening. During this gathering, the dancing continued for four hours. The elderly people from Rise danced to their hearts’ content, and when there were doubts about the steps, Hans Nielsen and Clemmensen partnered with one of the older women.16

Fig. 11.6 The farmer and musician Hans Andersen Hansen in Rise on Ærø, 1948. Hansen was a central figure at the dance recording in 1918, 1939–40 and 1948. Photograph © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

The updated version of Old Dances from Fyn and the Islands (1949) contained additions and revisions to the description of the mollevit. For example, Clemmensen and Nielsen wrote that ‘the partners were turned half toward the front, and the ladies had half their backs toward the front, as the mollevit was danced.’ This is in contrast to the way Kjellerup explained that ‘in the variation only a half turn with the right hand and later a half turn with the left hand is danced, not a whole turn as described in 1941’.17

Rhythm and Character of the Mollevit among the Residents of Ærø and the Folk Dancers

After Kjellerup published Old Dances from Fyn and the Islands, several dance instructors still had difficulties understanding the description of the mollevit. The folk-dance instructor Skjold Jensen was among those wanted to observe the dance first-hand. So he decided, together with his father and brother-in-law, to take a trip to Ærø to see how the mollevit had been danced there. They were referred to Hansen’s son, the merchant and draper Jens Hansen in Ærøskøbing.

Fig. 11.7 Four generations gathered in Ærøskøbing. Sitting with his great-grandchild, is the musician Hans Andersen Hansen. Standing to the left, Jens Hansen, and his son, who managed the grocer’s house with drapery at Ærøskøbing square. Jens Hansen was for many years the leading dancer of the Mollevit and was a tall and handsome dancer, leading the mollevit with great certainty. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

Jens Hansen embraced the visitors and showed them into his office, a lovely large room behind his shop, with brown linoleum on the floor. Then there was dancing. Hansen’s brother-in-law played along. That experience became one of Jensen’s greatest experiences when it comes to folk dancing. He was amazed by ‘[h]ow he [Hansen] could take the steps in compliance with the music. He had from his earliest youth got the movements and the music into the body. He had grown up with it.’ Hansen seemed to have the mollevit in his blood. Jensen observed, ‘What is being danced today [in 1988 by Danish folk dancers] has nothing to do with the way my dear tutor from Ærøskøbing danced.’ Jensen continued: ‘I am not a native Ærø resident, but [I could still see that] he was completely empathetic in the rhythm with which the mollevit should be danced.’ Jensen reported that Hansen’s steps and rhythm were smooth and even, without much up-and-down movement, but with much turning or twisting of the body.18

On Ærø, a revival of the mollevit in folk-dance associations occurred in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Peter Henry Rasmussen was instrumental to this revival. While living in Odense, he had been a member of the Odense Folk Dancers—the same association in which Hans Nielsen from Hjallese was an instructor, and the two were close friends. Nielsen taught Rasmussen how to dance the mollevit. When the latter moved to Ærø in 1947 after qualifying from the Ollerup Gymnastics School, he taught both gymnastics and folk dances, including the mollevit, to many students. This movement began to grow even before Nielsen had seen the mollevit danced by the elderly population in Rise. In 1950, Rasmussen included the mollevit on the program for the first local dance show, which was held at Tranderup Village Hall. Hans Andersen Hansen was in attendance. After the show, Hansen stood up and said that the steps were good enough, but there had to be more movement and rhythm in the dance.19

Fig. 11.8 Ingeborg Therkildsen came to Æro from Jutland and married the farmer Ole Therkildsen in Rise. In a period after the second World War, Ingeborg and Ole Therkildsen participated in several dance events, where the participants mainly consisted of older people, and where the mollevit was danced every time. Photograph by Anders Chr. N. Christensen 1984. © Anders Chr. N. Christensen.

In yet another round of folk-dance collection conducted on Ærø in 1984, Anders Chr. N. Christensen was referred to Ingeborg Therkildsen, among others, as a source of knowledge about the mollevit. Therkildsen was originally from West Jutland but had married into one of the old Rise families who was fond of dancing. With these family members, she had attended some dance evenings held by the social association at the Dunkær Inn. Most of the participants were older people who met and danced the old Ærø dances. On each of those occasions, the mollevit was danced at least once.

To learn the mollevit, Therkildsen went with her husband to meet an older woman in the parish. After a few attempts to perform the steps, the woman said to Therkildsen: ‘This one you will never learn’. Therkildsen realized that the woman was right:

I thought I could [dance] the mollevit, but I could not. I have enough self-knowledge today to see that I could not make those movements as the elderly could. It was an exercise. They had done it so many times.20

Therkildsen explained that she was not the only one who could not match the style of the dancers from Rise, mentioning that they sometimes danced together with the folk dance association Vippen in Marstal. When the elderly dancers from Rise watched the younger dancers from Vippen dance the mollevit, they pointed out: ‘You may probably see that they do not have the rhythm in them the way they should have, as the elderly in our association’. Therkildsen clarified that, by this statement, the Rise dancers meant that they danced the mollevity differently: ‘They danced with the whole body, and if the legs did not participate, the body did. [...] Seeing that was fantastic’.21 Therkildsen could see for herself that the folk dancers did not dance with the unique rhythm of the elderly Rise dancers. When the latter danced the mollevit, their steps seemed to shift in relation to the music, as if they danced a little after the basic rhythm.22

The farmer and fiddler Hans Albert Jensen, from Skovby on Ærø, started playing for dances in the 1940s, and he played at more of the island’s public and private parties than any other musician. Jensen said that, when he initially went out to play, the mollevit was danced at almost all the private parties in Rise, and that there were individual families who were very good at dancing it. His impression was that the mollevit was danced in a far more relaxed way at those parties than it was by the later folk dancers of 1984. He said: ‘Yes, so it will be. It is a learned dance; it is crammed into your head’. The style was so different, Jensen said, that they seemed not to be the same dance: ‘The old people had not the bending of the knee that has been added at the folk dance’. It seems that several folk-dance instructors had, over the years, incorporated into their mollevit a small bending of the knees on the second and sixth count where there originally was no movement.23

Fig. 11.9 The former farmer and musician Johan Larsen from Rise. From his earliest youth, Larsen had played the mollevit at private and public parties in Rise and on Ærø. He could perform two different melodies. Photograph by Anders Chr. N. Christensen 1984. © Anders Chr. N. Christensen.

Mollevit Melodies

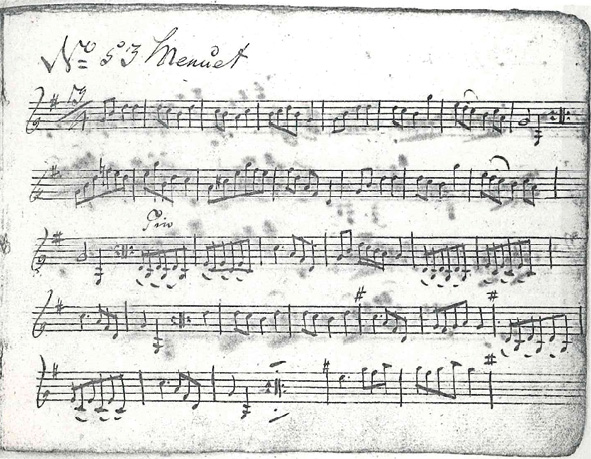

Fig. 11.10 Various minuet melodies were used on Ærø, but, over the generations, its inhabitants favoured a particular melody. The melody was written down in the earliest extant notebook in Denmark—one annotated Notebook for Niels Gottlob, commenced on 19 Februarii Anno 1772, Informant Joh. Lud. Dauer’. This notebook confirms the strong position of the minuet on Ærø in the 1700’s, since thirty-nine out of one hundred and six melodies it contains are minuets. Ærø Museum. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

For many years, the mollevit was not connected to a particular melody; a myriad of tunes had been used to accompany the same dance. Later, as the mollevit gradually came to be played only once in the course of an evening, the number of melodies narrowed. Only two melodies survived in the living tradition up to 1990.

The most used mollevit tune on Ærø has been known since the latter half of the 1700s. It is found in the oldest preserved music book from the island, one that belonged to Niels Gottlob in 1772. Out of the one hundred and six tunes in the book, thirty-nine are minuets, comprising more than a third of the recordSeveral authors note in 1790 that the peasants transformed the minuet and danced ‘minuet en quatre’ a version in which two couples dance at the same time. Interestingly, such a ‘Menuet en quatre’ occurs in Gottlob’s music book.24

The minuet tune referred to as the most used one on Ærø have many parallels known from the oldest preserved music books in Denmark.

Minuet Traditions on Lolland-Falster

When the Association for Folk Dance Promotion published a new regional booklet entitled Gamle Danse fra Lolland-Falster (Old Dances from Lolland-Falster) in 1960, it was the eleventh in a series of works documenting folk dances from Denmark. The booklet contained descriptions of thirty-two dances from Lolland-Falster. In the first edition, two of these dances included the word ‘minuet’ in their title—namely, the ‘Lang Menuet’ [Long Minuet] and ‘Menuet med Pisk’ [Minuet with Whip]. The second edition of Old Dances from Lolland-Falster (1996) was expanded by eleven dances, one of which was an additional minuet, the ‘Rund Menuet’ [Round Minuet]. A total of three dances from Lolland-Falster have the word Minuet in the title.

The three dances are described as follows:

Long Minuet, Væggerløse

Formation: Couples in two facing rows

- The rows dance one minuet step towards each other without holding hands, and then one minuet step backward to their own places. This is repeated. The couples then give each other a right hand, and dance one round toward the left, stopping in place.

- All dancers form a half chain with opposite couples, and perform two minuet steps. Two couples half chain back to their own places, using two minuet steps.

The same two couples dance with four minuet steps in a circle one round to the left, swinging the arms, beginning by swinging towards the center.

The dance is repeated at will, but during the final time, all couples form a grand circle dancing four minuet steps to the left (arms swung as before)

Johannes Egedal wrote down the dance based on information from Karen Suder, Fiskebæk at Marrebæk. His description became the basis for the printed version together with a description sent by Rasmus Toxværd, Væggerløse.25

Round Minuet

Formation: Indefinite number of couples in a grand circle

- Without holding hands, dancers perform one minuet step towards the centre of the circle and one minuet step back. This is repeated. The couples give each other a right hand and the couples dance one round to the left, using four small minuet steps. All dancers stop at their own place in front of their own partner.

- Couples then dance without holding hands around the circle as in chain with zig-zag.

The men dance counterclockwise minuet steps and the women dance clockwise minuet steps.

The zig-zag chain continues until the couples meet their partners. Then they form a grand circle holding hands, stop facing the center of the circle, and swing their arms in step to the music until the music concludes.

The Minuet with Pisk

Formation: Couples in a circle facing forward with arms down at their sides

Steps: Minuet steps and running steps

- All dance four minuet steps forwards in the dance direction side by side with own partner. Then, with four minuet steps, the ladies dance one round right around the man from the above pair. Simultaneously the man dances one round right around the woman from the behind standing pair.

At the first minuet step, the man turns right, and takes a step backward. After the fourth minuet step all stand side by side with the opposite dancer.

- Using four minuet steps, the man dances one round to the right around his partner. On the First minuet step, the women turns around to her left, starting with a step backward. After the fourth minuet step, all dancers stand by their own partners facing the forward dance direction.

- ‘The Pisk’: The couples have a backcross grip, and take eight running steps in the dance direction, starting with the right foot. The couples then turn one round in place, the men backward and the women forward.

- The couples take eight more running steps. This is repeated, and the dance continues at will.

The dance, which is also known as Mollevit med Pisk Væggerløse, was recorded by Erik Jensen after Pouline Rasmussen and tailor Jørgen Rasmussen, both from Tårs.26 The music was recorded after farmer and fiddler Jørgen Romme, Nørre Radsted.

The steps described for the three dances above are minuet steps. In a typical minuet, however, the male and female partners stand opposite each other and change places, as seen in the Minuet from Randers area and in the Mollevit from Ærø. The three dances from Lolland-Falster deviate from that practice; they have the form of contradances insofar as one couple faces another couple in row formation, couples dance in a round facing the centre of the circle, or partners dance side by side, facing the dance direction on a circular path.

In the next part of the chapter, I examine all of the records that underlie the descriptions of the minuets in Old Dances from Lolland-Falster with the objective of determining whether these dances have a relationship with the minuets from Randers and Ærø. Could the three dances above originally have been minuets with the more traditional formation in which the male and female dance partners face one other while they make the configuration?

Rasmus and Karen Toxværd’s Dance Records on

Southern Falster

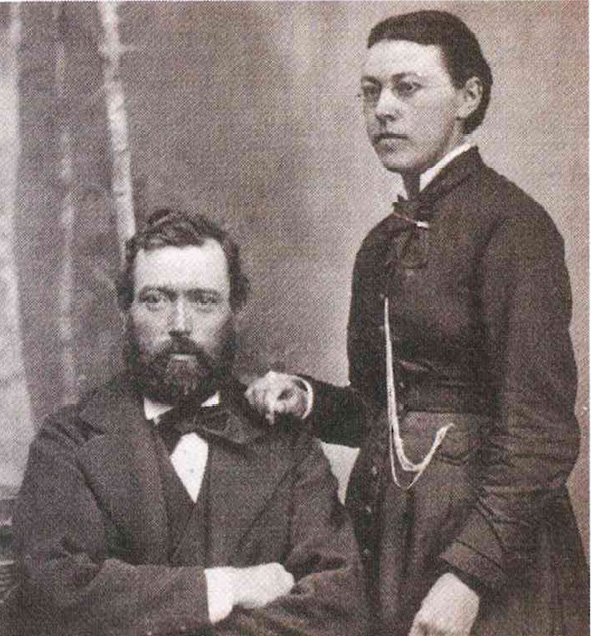

The earliest reports and records of the minuet from Falster were made by the siblings Karen (1853–1941) and Rasmus (1847–1923) Toxværd from Væggerløse on South Falster.

Fig. 11.11 The siblings Rasmus and Karen Toxværd, of Sillestrup, later Væggeløse. In the summer of 1873, Karen Toxværd was a pupil at Grundtvigs Højskole. From 1884 until her death she provided Evald Tang Kristensen and later Dansk Folkemindesamling with notes from Southern Falster. Rasmus Toxværd reviewed everything Karen submitted. He had a musical knowledge, and he wrote down all the melodies he learned from his father. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

They submitted their first folklore reports to the prominent folklore collector Evald Tang Kristensen in 1884. After the establishment of The National Collection of Folklore in 1904–05, the pair were diligent producers of folklore records. Karen submitted a vivid account collected from South Falster of the ceremonial Bridal Minuet as it was danced there in the mid-1800s:

Finally, the time came when the dance should start, and now everybody flocked to the upper room; even female cooks and dishwashers left their workplaces and placed themselves outside the windows to watch the bride dance. She danced the first minuet alone with her father, and when it was finished, he led her to the groom and asked him to ‘loosen his hand’, both here and on the whole. Then the bridal couple danced the next minuet alone. After that, the ‘bridal circle’ danced together with them, being the nearest related young people from both families, who in advance had been told with whom they should dance […] [after the coffee break:] The musicians now split up so that half of them went to the barn followed by the young people, the older people danced in the living room, and in between, beer and brandy were offered. The dance went on with animation and endurance until the bright morning, waltz and scottish changed with the minuet, sorte-lam, and fangestykket. Yes, when it became animated, it was seven steps syvspring, and nikongersdans, tremandsril, and halvfemtetur.27

Hakon Grüner-Nielsen, who we have already discussed as a folk-dance collector on Ærø, worked as an archivist with responsibility for the music department at The National Collection of Folklore. In 1917, he circulated a request for information about old folk dances from Lolland and Falster and also asked if anyone knew Minuet or Mællevæt, its local name. Grüner-Nielsen requested the following: ‘we will be very grateful to receive descriptions of the mentioned dances or at least have information on addresses of people who may be able to give us some information.’28

Rasmus Toxværd responded to the call in February 1917, submitting four closely written folio sheets with the title ‘Gamle Danse fra Sydfalster’ [‘Old Dances from South Falster’]. These included information about the Mellevæt as it was danced partly as ‘The Long Minuet’ and partly as ‘The Round Minuet’.

Toxværd wrote that the Long Mellevæt was danced only by two couples, who lined up at opposite ends of the living room:

As the music started, they went with their specific Mellevæt steps toward each other, without touching, firstly once around each other. Each couple then went towards each other, passed each other to the opposite end of the room, around each other, and likewise back again. This was repeated two or three times, and at last, the couples went towards each other and met midway.29

The fact that only two couples participated in this dance at a time might suggest that, earlier, the dance was connected to the ceremonial bridal minuet, which was danced first by the bride and her father alone. In South Falster, after the bride and the bride’s father danced, the bridal couple danced, and after that the bridal circle, consisting of the young people nearest of kind from both families, joined the festivities. During this part of the dance, two couples at a time danced with the bridal couple. A letter from Toxværd to Grüner-Nielsen regretted the former’s inability to help further with this dance:

Unfortunately, I cannot further describe the dance steps to ‘Springestykket’ as well as not to the ‘Mellevæt.’ I have seen them danced several times but did not get them learned, as I possibly was too slow-witted.30

Indeed, Toxværd recognized that the bridal minuet was danced as the Long Minuet. He had even heard that it was only danced by one couple—namely the bride and groom.31 His description of the Round minuet was as follows:

In the Round Mellevæt, as many took part as could get space and felt like it. They arranged themselves in couples in a big circle, went around each other and then to the middle of the room, still to the beat of the music, stamped, and returned back and round the neighbour. The men to the left and the girls to the right—out to the center and again back to the next neighbour and thus round the circle until everyone met the partner. Then the big circle was closed, and they swung the united hands back and forth standing at one place through some bars and thus the dance was finished.32

Karen and Rasmus Toxværd experienced the exceptional atmosphere of the dance:

In the Mellevæt where everyone went alone, it was appropriate to ‘behave’. And now you should not say, ‘Oh, how could the subdued and beggarly peasants of that time behave?’ I only have seen the Mellevæt danced by older adults, but I assert that they could dance with grandiose, literally noble dignity.Mellevæt, Springestykket, and To-Tre- and Fireture stayed as commonly used dances for a relatively long time, which you may know from the fact that there were countless Mellevæts, Springestykker, and tours.33

Rasmus Toxværd, who played the violin, related that the Mellevæt and Springestykket remained in use as common dances for a relatively long time. He estimated that they were known until sometime in the 1870s because music books from South Falster published in the preceding decades included a number of minuets that were no longer recognised by 1917.

Johannes Egedal’s Collection on Lolland-Falster 1917 and 1919

Johannes Egedal (1891–1956) became a member of The Association for Folk Dance Promotion in 1915 and, in the following year, was sent on his first collection journey, a trip to Jutland, that lasted twenty-two days. Egedal travelled by bicycle, with his violin in front and a bag with his lunch box and notebooks on the luggage carrier. The trip was extensive; by the end, he had cycled around 1000 kilometres.

Egedal travelled to Lolland-Falster in 1917. Before he left, he received some instructions from Hakon Grüner-Nielsen and was recommended to visit the siblings Karen and Rasmus Toxværd in Væggerløse to fully understand the dances that Rasmus Toxværd had sent to The National Collection of Folklore.

Fig. 11.12 Johannes Egedal, photographed in 1917 in connection with the collection of dances on Lolland and Falster. Egedal studied at the University of Copenhagen in 1917, hence the student’s cap. The bicycle was his favourite mode of transport, on which he placed pump, a repair kit, bag, and violin, used for writing down the dance melodies. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

After Egedal had recorded what Karen and Rasmus Toxværd had been able to report, he was directed to visit Karen Suder (b. 1837) from Marrebæk, south of Væggerløse.34 He described the minuet step after Suder’s description in the following manner:

The step is a polka step (always start (with) Left) and then a step now when you rest partly on this foot and makes a small soft bending.35

This 1917 description was the first attempt to document the minuet step in the traditional folk environment. While it is correct that the dance step starts with the left foot, it is doubtful that it starts with a polka step and that the next step was one in which the dancer rests on the same foot. It was probably not Egedal who did not understand the minuet step, but rather it was probably Suder who did not remember. She was eighty years old at the time of his visit, and it may have been fifty years since she had seen the minuet danced. Suder was likely unsure about the steps; perhaps she only experienced the minuet as it was danced by the older generation. Egedal believed that the dance traditions on Falster had not stayed alive for as long as those in Jutland. What he had been able to record was more inaccurate and less copious than could be wished.

Karen Suder described the Long Minuet as follows:

Minuet 2/1-8/:9–14://15.24:/

Formation: 2 pairs opposite each other.

(No touch!) 2 I’ 4 steps (1 forwards to the opposite dancer, 1 with the left hand to the opposite dancer, and 1 back/15–18/2 II’ exchanges /19–24//15–20/ at meeting swinging arms and tramp with the right (light) /21–24/.

Karen Toxværd’s mother had told that when the mood was high, the women spread their aprons while the men gave a stamp. Similar hints were found in Guldborg on Lolland (Jens Andersen), where they had a formation in rows.36

The Round Minuet was recorded by Egedal after Karen Suder, Marrebæk, and Rasmus and Karen Toxværd in Væggerløse:

They lineup in couples in a circle (they did not hold hands in the circle)

a.I. 2 times into (the circle) and back with 1 step

II. Round in couples holding one hand

b. They went in Zig-Zag in the circle (men counterclockwise, women clockwise) with one minuet step in each bar (a chain without giving hands), right foot in the peak of the bar! When this chain is finished, they form [a] ‘Big Circle’, stand still with the legs and swing the arms softly in [time with] the music’s beat. Here ends the dance. (For the total dance, only minuet steps are used.)37

Erik Jensen’s Dance Collection in the 1940s and 1950s

Erik Jensen was a dairyman. Because of this work, he visited many places across Denmark. Jensen moved to Lolland in 1939 after being recruited by Sakskøbing Dairy. From a very young age, he had engaged in folk dance through the gymnastic clubs that practised folk dance in the autumn. He also danced in a folk-dance team on Stevns that was managed by Elisabeth Andersen, collector and publisher of Old Dances from Præstø County (1939). 38 At a convention she explained that no descriptions of old dances from Lolland and Falster existed and challenged Jensen to take up the task. He started to ask the elderly people at a folk-dance event there if anyone remembered any old dances. Jensen met a few dancers who knew how to perform a few old dances. This was the beginning of Jensen’s work. By the late 1950s, he had collected enough dances to fill a regional booklet. What Jensen forwarded to Svend Clemmensen from The Association for Folk Dance Promotion formed the basis of Old Dances from Lolland-Falster (1960).39

In Old Dances from Lolland-Falster, Jensen had published the Long Minuet and the Minuet with Pisk. Egedal’s collection from 1917–19 provided one third of the Long Minuet, and he himself had found the other two thirds of the dance. Jensen received the middle third from the writer Helene Strange and the final third from an old pilot chairman in Gedser.40 In the versions of the booklet from 1960 and 1996, the Long Minuet was described as a dance in which the couples stood opposite each other in two rows. An account from Væggerløse noted that it was danced by only two couples in the living room. However, Egedal found a hint of the Long Minuet in Guldborg on Lolland, where couples had lined up in rows.41 Because the intention for the local booklets was to provide suitable dances for use in the Danish folk-dance network, their publishers decided not to include a dance was practised by only two couples at a time.

The Minuet with Pisk

Jensen’s documentation of the Minuet with Pisk included music, which he had written down from the fiddler Jørgen Romme in Nørre Radsted in northwestern Lolland’s. A Tvariant of the melody can be found in a music book which had belonged to Anders Rasmussen of Nørre Radsted. Here, it is called ‘Menuet med Polsk’ [‘Minuet with Polsk’] or ‘Rasted Degn’.42 The first two parts are clearly a minuet melody. From the third part, however, it becomes a Polsk melody. The title ‘Polsk’ is written above the third part.

Romme recommended Kirstine Hansen in Hjelm as someone who could help Jensen to learn the dance known as the ‘Mollevit med Pisk’ [‘Mollevit with Pisk’]. With Hansen, Jensen met an elderly man who also knew the dance. It took Jensen three visits to Hansen and her partner before he was sure enough about the dance to describe it.43

Jensen described the Pisk as an independent dance with eight running steps by dancers in pairs with a backcross grip forward in the dance direction. The couples then turned one round on the spot, the men backward and the women forward. Jensen understood that the Pisk was used as a ‘second course’ or a dance that came only after others such as the Snurrepisken, Firetur with Pisk, Mollevit with Pisk, and others.44 Probably, the Pisk had been called a Polsk earlier. We know from other recordings around Denmark that in the mid-1800s, it was likely a dance around on the spot. The Minuet with Pisk may be a further historical development of the minuet followed by Polsk. Danish sources from 1795 and 1798 stated that the peasants exclusively alternated between the minuet and Polish dances.

Johannes Egedal’s Observations

When Egedal recorded the old dances on Lolland and Falster in 1917 and 1919 he did not receive descriptions that were entirely comprehensible. On 27 November 1917, he wrote about his collection:

Regarding the actual work, I believe it could be said that there has been offered quite a lot more accuracy than the case was at the recording in Jutland 1916, but the result seems to me despite that not so good as recording [made in] 1916. The reason for this is double. Firstly, the old dances on Falster barely have stayed as long as in Jutland, and, secondly, a substantial increase of the number of informants has increased the uncertainty, as not all the accurate (if they exist) but also the less accurate informants have been the source. Unfortunately, I have not got as full written information from some of the informants as I could wish.45

When Jensen recorded the dances in the 1940s and 50s, very few people had actually danced the minuet. By 1960, he was familiar with the minuet step from the folk-dance movement on Ærø and in the Randers area, but he met very few people who were dancing the minuet steps on Lolland.

Minuets from Lolland-Falster Today

Minuets today are danced as contradances with minuet steps, following the descriptions from Old Dances from Lolland-Falster. One question which arises is whether we can be sure that the recorders and informants saw and remembered contradances rather than minuets. Rasmus Toxværd did not make clear if the pairs stand opposite each other as a row of men and another row of women or whetherthey stand as couples facing towards each other. The fact that the Long Minuet only could be danced by two couples in the room may be a legacy from the Minuet en quatre—a version in which four people lined up so that the men stand opposite their partner, as the peasants had danced in the late eighteenth century. It may also be a legacy of the bridal Minuet, which, on South Falster, had been danced by first the father and the bride, then the bridal couple, then two couples at a time, consisting of the bridal pair alternating with a couple from the closest family. In Væggerløse, on Falster, the Long Minuet always was danced by two couples, four persons. The Round Minuet is quite clearly a contradance which everybody could join. What makes a minuet is that the music and the dance consist exclusively of minuet steps. The Minuet with Pisk recorded by Erik Jensen after Jørgen Romme, Nørre Radsted, Lolland, may originally have been a minuet danced solo, followed by a Polsk dance with two strokes. A variant of the melody is written down under the name ‘Minuet with Polsk’ in a music book belonging to Anders Rasmussen, Lolland.46 It may be that Jørgen Romme and Kirstine Hansen only had seen the dance, and not participated in it. Therefore, they may only have been able to show the way the pairs moved and not the steps that were used.

We cannot definitively conclude whether the way that the dance was performed in 1917, 1919, and the 1940s, and the 1950s is the same as described in the booklets used now. Today, the Minuet on Lolland and Falster is described as a contradance: the man has the lady on his right side, but in the bridal minuet, traces of the earlier minuet are apparent when the man and woman take positions opposite each other. The earliest recordings of the minuet for two couples are not precise, and the steps they show differ from the minuet steps. This investigation reveals historical sources that suggest a legacy from the eighteenth-century dance figuration in which the man and woman stand opposite one another. Minuet melodies and dances probably developed from this ‘standard’ minuet form into a contradance form. When and why this development happened, one can only speculate. Perhaps the reason is that when the minuet was no longer a ceremonial dance connected with weddings, it lost its importance and, in this period, became a contradance.47 Alternatively, those making the recordings may not have understood what the dancers explained or how they danced on the floor.

Dances in the folk tradition continuously change. These changes may happen in the dance itself or because of a recorder’s misinterpretation. Once written down in dance description, the version lives on in the folk-dance environment.

Today, the Long Minuet is very popular in the Danish folk-dance environment and is often danced.

Minuet Traditions in Randers Area

The third Danish region where the minuet survived until the twentieth century was the Randers area of Central Denmark on the Jutland peninsula. Detailed documentation comes from the villages of Bjerregrav, Støvring, and Mellerup, north of Randers’ town.

The Bjerregrav Minuet

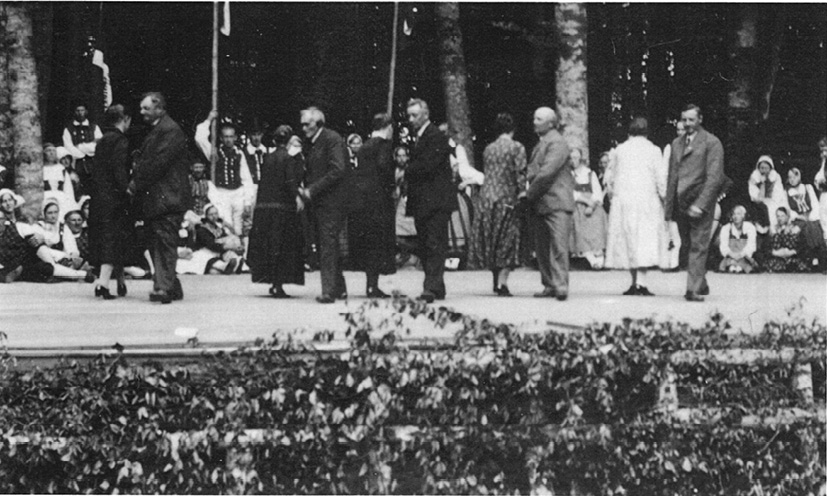

At the first national convention for Danish Folk Dancers in Skanderborg in 1930, a team of dancers from Øster Bjerregrav attracted great attention by dancing the minuet.

Fig. 11.13 From west of Randers, the Bjerregrav dancers show their ‘Monnevet’, a popular minuet, for the first time. The dancers wear their ordinary Sunday clothes, which included suits for the men, at the first Danish Folk Dance Event in 1930 in Skanderborg south of Aarhus. The photograph clearly shows how the couples exchange rows. The dancers turn their left shoulders forward in the dance direction so that the couples face their own partner, almost as in the Mollevit from Ærø. On the left are Madsine and Peder Jacobsen. He was the leading dancer who decided when the dance should stop and when the variation with giving hands should take place. Photograph © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

A spectator wrote:

It was quite breathtaking when a team of fine old peasants from Bjerregrav danced their old minuet. There were seventy-year-old people among them, and they did not wear folk costumes but their normal Sunday clothes. The minuet they danced was in every respect admirable. The dance was continually going as syncopation against the beat.48

Poul Lorenzen, who was the first chairman of the organization Danish Folk Dancers and worked as a state forester, wrote of the minuet in 1978:

We sought in vain for several years and thought it was dying, but were told that some families in Bjerregrav west of Randers still danced it at celebrations as, e.g., silver weddings.49

He had received this information in the 1930s from another state forester who managed the Fussingø forest district and this contact put Lorenzen in touch with Jens P. Bugge in Bjerregrav.50 Bugge assembled some dancers from Bjerregrav to teach the minuet to Lorenzen and some other folk dancers. Lorenzen found the dance very challenging:

We were well received and taught, but the dance, being a row dance, was not at all easy to learn, and concerning recording the minuet I nearly turned grey-haired before time. The older people comforted me at best, saying it was straightforward. You just work hard and follow the music. And remember the little drag with the foot.51

Lorenzen had to visit Bjerregrav several times before he had control over the dance.

In 1982, Anders Chr. N. Christensen was referred to two sisters who had danced the minuet over fifty years earlier for Lorenzen. Mette Christensen was ninety-three years old, and Kirstine Brøndum was ninety years old at this time. Both were living in Randers and had grown up in Sandby, a little south of Randers. Neither of the two knew the minuet from their home region. They explained that they had first seen it danced by the guests in Bjerregrav at Christensen’s wedding in Sandby, in 1910. Both sisters learned the minuet after they got married to men from Bjerregrav who could dance it. Christensen and Brøndum claimed that they found the minuet difficult to learn and that some people in Bjerregrav never learned it properly.52

Fig. 11.14 The Bjerregrav dancers are lined up for a photograph at the Nordic Folk Dance event in Ålborg, 1937. On this occasion they danced in their finest clothes otherwise used only at special occasions such as weddings, silver weddings and funerals. These were black dresses for the women and diplomatic suits for the men. On the left is Peder Jacobsen who was the dancer in Bjerregrav. Photograph © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

From 1930 to 1938, Lorenzen had invited the traditional dancers from Bjerregrav to perform their dances at various events in Denmark. Although they danced only the minuet at the first show, later they also danced an old longways scottish. At these events, the dancers appeared in their ordinary clothes and not in folk costumes. At the first performance, they wore their Sunday clothes which included suits for the men. Later, they wore their finest clothes—those that were reserved for special occasions such as weddings, silver weddings, and funerals. These included black dresses for the women and frock coats for the men.53

![Twelve dancers from Bjerregrav in rows at Nordisk Folkedanserstævne [Nordic folk dance event] (1937). Photograph.](image/11.15-DARKER.jpg)

Fig. 11.15 The dancers from Bjerregrav in rows with the leading dancers in front or in top of the row. Nordisk Folkedanserstævne 1937. Photograph © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

After these performances of the minuet in the 1930s, there was a revival of interest in the dance among the people in Bjerregrav. However, as new families arrived in Bjerregrav in that decade, the younger generation did not learn the dance. One informant recalled that ‘It even became a problem, that when musicians started playing the minuet, many ran out of the village hall and many did not like the minuet’. The minuet was danced at Christensen’s wedding in 1937, and it was also danced later, but not, it seems, after 1942 when Peder Jacobsen died. Jacobson had led the minuet, and no informants could remember other leaders.54

Performance of the Bjerregrav Minuet

Lorenzen also learned that the minuet was being danced in other communities. In 1978, he wrote:

Later the minuet also was found to be alive east of Randers. The steps are the same as in the Bjerregrav minuet and the dances are much alike, but not totally identical, and the melodies are different.55

Curiously, no preserved description of the minuet from Bjerregrav has been found. When Old Dances from the Randers Area was published in 1943, it did not contain any mention of the minuet from Bjerregrav.56 Instead a description of a minuet from Mellerup northeast of Randers was published.

Christensen recalled that the co-publisher of Old Dances from the Randers Area, Søren Hornbæk, came several times and observed the dancers from Bjerregrav. When the dancers from Bjerregrav saw the folk dancers in Randers dancing the minuet they felt that the dance was changed.57 Søren Hornbæk and those who prepared the description of the minuet for the booklet had not changed the dance, but the folk dancers danced the minuet as it was danced in Mellerup. Today, it is incomprehensible why the publishers of Old Dances from the Randers Area neither included these minuets nor described the differences between them, since the minuet was distinctive and central in the booklet. If they did not wish to present two nearly identical dances, they could have at least described their differences. The many differences between the minuets danced in Bjerregrav and Mellerup are extremely significant. According to the description from Mellerup, the signal to the first variation was given by the lead dancer by moving his hands around as if he was winding yarn; all men repeat this, and then all men delivered a clap at the first step in the first variation. In Bjerregrav, only the lead dancer clapped his hands. This clap occurred when the dance started, before the first variation, and before the termination. In contrast, in the towns northeast of Randers, the dance did not begin with a clap.58

In Bjerregrav, the minuet was never followed by a waltz or a firetur as had been common in the towns northeast of Randers.59 In Bjerregrav, the dance ended by a compliment of the couples to each other, and then the minuet was finished without any specific dance following it.60

Another difference was in how the first variation of the minuet was performed. From the description of the minuet in eastern towns that appears in Old Dances from the Randers Area (1952), partners gave their right hand, and danced one minuet step clockwise and one anti-clockwise, and the couple ended by facing their partner.61 In Bjerregrav, the first step of this variation finished sideways: dancers did not give a right hand but raised their right clenched fist and placed it their partner’s right clenched fist. After this, a backward step was danced, and instead of dancing ‘stomach to stomach’ as Mette Christensen expressed it, each dancer had his or her left shoulder against their partner’s left shoulder. This positioning is seen clearly in a photograph from 1930: when the dancers exchanged rows, they turned their left shoulders toward their partner as in Mollevit from Ærø. Some gave their partners both hands when exchanging rows.62

Another interesting observation that had emerged in the investigation in Støvring, northeast of Randers, as early as 1980 concerns the rhythmic character of the minuet. A description in Old Dances from the Randers Area stated:

One minuet step reaches over 2 bars. One counts 3 in the bar or 6 on each minuet step. At 2 and 6, no shift of foot, but a sink or a dwelling.63

These ‘sinks’ or ‘dwellings’ have become characteristic of the minuet dancing in the Danish folk-dance associations. Informants from Støvring reported that they neither sink nor dwell and had never seen the older generations make these kinds of motions. However, they did stand still on counts 2 and 6 of the minuet step.64

The investigation in Bjerregrav in 1982 revealed that the minuet had the same character there as in Støvring: there was neither a dwelling nor a sinking on counts 2 and 6 of the minuet step. Christensen insisted that ‘[i]t must be smooth’. Kristine Brøndum concurred, and said ‘You walked smoothly with small movements’.65

The Use of the Minuet in Mellerup and Støvring, Northeast of Randers

In Denmark, the minuet tradition survived the longest in Mellerup and Støvring. Albert Kjærgaard is a key source for information about dancing in these areas. He was born in 1884 and lived his whole childhood and youth in Mellerup. Kjærgaard reported:

The minuet was played once or twice always when the young or the old held a ball. The older people, that is the married ones, had one ball a year, where they danced for two days, and then the minuet always was danced, but it was also danced when the young ones had a ball.66

At the turn of the century, all of the young people local to the area could dance the minuet. Kjærgaard recalled that others who moved into the community and who could not dance the minuet often sabotaged the dance by clapping their hands to drown out the music. Nevertheless, he explained:

the musicians in Mellerup were just as interested finishing the dance. Thus it always had been, and it always had been finished the right way by playing ‘Kræn Skippers Firetur’. This was almost too much for the young generation, who then danced the waltz, which was ‘Kalkmandens Vals’.

Kjærgaard had learned ‘Kræn Skippers Firetur’, a waltz melody, which was danced by the older generation. He noticed when the ‘Firetur’ started to disappear; the musicians played ‘Kalkmandens vals’ instead.67

The minuet played an important role at weddings in the 1800s. The wedding couple danced the bridal minuet, and it was also danced on the second day of the wedding to bridal couple was danced off the (unmarrieds’) team. Informants described this rite of passage:

The young couple switched from the young group to the married group. The bachelors should hide the groom, and the bridesmaids hide the bride. When they were found, a minuet was danced followed by a firetur at a smooth square in the open.68

Records from the 1800s report that ‘They had a dram from the bottle during the minuet, going the row around while they danced.’69 Kjærgaard witnessed the same thing in his childhood:

The brandy bottle went from mouth to mouth in the row of men while dancing the minuet. All men had a mouthful while dancing and passed the bottle to the next man.70

This tradition was also reported in Bjerregrav, where ‘a bottle of cognac [was] brought by the waiter and from which all the men had a mouthful during the dance’.

Kjærgaard learned how to dance the minuet from a poor woman in Mellerup. She gathered himKjærgaard, her son, and three or four other boys of the same age in her small room for lessons. He remembered:

She said, ‘Now you may watch the legs’, and pulled up the long skirts. This did not often pass at that time that anybody got a look at the legs. ‘Then we could see how we should step.’ During the learning, the boys sang.71

The Minuet Tradition Disappears in the Randers Area

In the villages Støvring and Mellerup, about seven and ten kilometres northeast of Randers (near to Randers Bay) respectively, the minuet has stayed alive the longest. It survived nearly as long in surrounding towns—on the other side of Randers and Nørre Djursland—but began to disappear one or two generations earlier in those areas.72

Fig. 11.16 The carpenter Jens Sloth from Dalbyover plays the Monnevet in connection with video recordings in Støvring and Mellerup, 1980. He was, at that time, the last surviving musician to have played the minuet at private parties in Støvring and Mellerup. Photograph by Svend Nielsen. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

When Kjærgaard left Mellerup in 1910, everyone there, including young people, could dance the minuet. When he moved to Hald, just eight kilometres away, in 1919, only four older couples could dance the minuet. These Hald dancers tried to teach some interested people to dance the minuet, but, as Kjærgaard explained, ‘It is not so easy to learn. And no more could it’. Consequently, it was never danced at the celebrations in Hald, though, in earlier times (a generation before Kjærgaard arrived), it had been danced just as much in Hald as in Mellerup and Støvring.73

Another very informative account comes from Inge Bonde Jensen who was born in Lindbjerg near Støvring. She saw the minuet danced during her childhood at Christmas parties held in the Lindbjerg village hall in the 1920s. There, she reported, one could see the older people dance the minuet after the children had walked around the Christmas tree and played games. As the old couples lined up in two rows in their black clothes, they created a very elegant spectacle. Many continued smoking the long pipes while dancing and, at the end of the dance, they placed their mouthpieces into the buttonholes of their jackets to conclude the party by dancing the waltz.

Jensen had been taught how to dance the minuet by an aunt who also taught folk dance. But the minuet was not instructed in Mellerup. In the 1920s, the minuet was a dance that, like the waltz and rheinlaender, everybody knew. In the early 1930s, Jensen participated in several parties in Mellerup village hall, where it was always danced. This was her first great experience of dancing, standing one evening between her aunt and an older woman as they danced in long black skirts. ‘How she felt the rhythm of the minuet’.74

Fig. 11.17 The Monnevet danced in Støvring, a few kilometers northeast of Randers, in 1980. The couples are exchanging places so that the ladies return to the ladies´ row. In front are Sigurd and Inge Bonde Jensen. Sigurd Jensen is the leading dancer who decides how long time the minuet should be danced, and when the partner shall give hand to own partner, a variation in the middle of the minuet. Photograph by Svend Nielsen © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

In 1937, Jensen married Sigurd Bonde Jensen. The couple moved to Støvring, where the minuet was danced by the older people at weddings or silver weddings in the village hall. By 1940, many of the young people in the community did not know the minuet, and this was felt to be great shame. Jensen offered to teach them. The first evening was all right, she recalled, ‘You can learn the steps by some teaching [...] but the rhythm—or whatever you may call it—and I think you must dance it for many years before you appreciate it’. Several couples learned the minuet, and thus it was danced in the 1940s and 1950s. Good orchestras continued to play minuet melodies. The last time it was danced at a private celebration was in 1962, at Jensen’s parents’ golden wedding anniversary.75

At the end of the 1970s, Kjærgaard and Jensen were contacted about their memories by The Fiddlers’ Museum and The National Collection of Folklore. In 1980, it became possible to record the minuet on video. Carpenter Jens Sloth played as five couples danced the minuet in Støvring village hall.

A small revival of the minuet took place in Støvring. The music was played at a few parties in Støvring, and five couples danced. One problem, however, was that the orchestras of the 1950—which consisted of violin, piano, and drums and were very capable of playing the minuet—were being replaced by an electronic organ. According to Jensen, ‘It is not the same to dance the minuet to an electric organ as to a violin’.76

Fig. 11.18 Here, the front dancer, Sigurd Bonde Jensen, gives the signal for completion of the minuet or for all couples to give right hand to their partners. This is done by raising hands or forearms to breast height and turning the two forearms around. Note how the front dancer looks down the row to see if all have seen his signal. Photograph by Svend Nielsen, 1980. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

|

Video 11.1 Minuet danced in Støvring. Filmed by Svend Nielsen, 1980. © Dansk Folkemindesamling. Uploaded by Norwegian Centre for Traditional Music and Dance, 5 March 2024. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/48a17325 |

|

Video 11.2 Minuet danced in Støvring. Filmed by Svend Nielsen, 1980. © Dansk Folkemindesamling. Uploaded by Norwegian Centre for Traditional Music and Dance, 5 March 2024. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/8e6a59fc |

Fig. 11.19 Here, the couples are doing the variation in the middle of the minuet, where right hands have been given to their partners, and thereafter left hand given to own dancer. Here all the couples have given the left hand and are ready to dance into the basic figure of the minuet. Photograph by Svend Nielsen, 1980. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

Fig. 11.20 Here, the ladies are closest to the front, and the partners´ row has moved furthest away from the front, and they are hereafter ready for changing the rows. Photograph by Svend Nielsen, 1980. © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

The resurgence of interest in the minuet was brief. Jensen, because of illness, could no longer dance. Since then, the minuet has not been danced at private parties in Støvring. Inge and Sigurd Bonde Jensen, for many years, had been leading dancers in the minuet.

Minuet Melodies

Formerly, countless numbers of different minuet melodies have been used. In 1800, for example, the minuet was such a favoured dance that many of the fiddlers from the area composed new minuet tunes. Among these was ‘Niels Kragh’s minuet’. It became so popular in the villages northeast of Randers that this new supplanted many of the older minuet tunes. Niels Kragh was born in Hald in 1841 and died in the same place in 1915.77 ‘Skaberens Minuet’, which can be traced back to the end of the 1700s, was one of the melodies that was much loved and remembered in the Randers area.78 In Mellerup, it was still played in 1935 when it was recorded on a phonograph in Fjellerup in North Djursland.79

In Bjerregrav, west of Randers, a fine musician named Kræn Lassen always played the minuet. He had a son who was also named Kræn Lassen. The younger Lassen continued the tradition of minuet playing and had his own orchestra. At parties in Bjerregrav, the orchestra had its own melody that was always used at parties. This was composed by Søren Nielsen Høegh, who had been born in 1820, in Bjerregrav.80 Høegh became a well-known dance composer whose melodies are found in music books preserved from the Randers area. After his marriage in 1853, Høegh moved to Over Hornbæk, south of Bjerregrav. The family moved to Værum, south of Randers, in 1869, and Høegh died there in 1882.81

Fig. 11.21 ‘Skaberens Menuet’ [‘The Creator’s Minuet’] has been played many times in the region of Randers, and, in 1915, H. Grüner-Nielsen recorded a ’Skaberens Menuet’ in Fjellerup in Nørre Djursland was played by the fiddler Munk. The melody can be traced back to the end of the 1700s: it was printed in court musician Schall’s ‘Arier og viser 1790’ with lyrics by Jens Baggesen from 1786, ‘Skaberen skuede den nyskabte Klode’. Photograph © Dansk Folkemindesamling.

In Støvring and Bjerregrav, newer nineteenth-century melodies have been played in the last period of the minuet for a dance which was much older. On Ærø, however, one of the minuet melodies can be traced back to the mid-1700s.

Thoughts about the Preservation of Danish

Minuet Traditions

The three areas of Denmark in which the minuet continued as a living tradition have similarities regarding the preservation of the dance, but they differ in relation to the minuet’s form, history and current use. One cannot find any straightforward explanations for their survival.

The mollevit may have survived on Ærø because of the isolated location of the island. Rise parish, at its centre, had a different structure and status than the other parishes on the island. It was the largest parish, and contained the best-situated farms (between Ærøskøbing Iand Marstal). From ancient times, the farmers invested in shipping shares and earned money by shipping. Another important factor was that families in Ærø continued to hold large celebrations that included drinking songs and old dances. In this social environment, the mollevit had a special status, which caused these familiers to continue the dance up to the present day.

Lolland and Falster are the southernmost isles south of Sealand. Like Ærø, these islands were relatively isolated for a long time, and many traditions stayed alive until the beginning of the 1900s. Falster did not get a bridge to Sealand until 1937. Thus, the local conditions created an environment which preserved the ‘old dances’ until they could be documented in the early twentieth century.

One of the reasons why the minuet tradition may have survived between Randers Bay and Mariager Bay is that the peasants in this area were relatively wealthy and conservative, with a strong interest in maintaining their distinctive dance. The Danish folklore researcher Evald Tang Kristensen made this observation one hundred fifty years ago:

In the area north of Randers certain customs and practices have kept strangely faithful up to our times as it is an old-fashioned and much-unaffected area.82

In Støvring and Bjerregrav, nineteenth-century melodies have been played to accompany a much older dance, which has meant that the musicians included minuets in their repertoire for much longer than in most parts of Denmark.

Communities’ cultural conservatism and the flexibility of the musical repertoire may explain why the minuet has been preserved in living tradition in this region up to our time.

References

Danish Folklore Archives (Dansk Folkemindesamling), Copenhagen

DFS 1906/36. Danse og Dansemelodier, Indsender Mortensen 1943. Nodebog 1. 13 bl. ca. 1850, Anders Rasmussen, Thoreby, Lolland. 48. Menuet med Polsk eller Rasted Degn

DFS 1906/43 top 1160. Fastelavnsskikke paa Ærø. Forfattet af Lærer og Sparekassebogholder I.P. Lauridsen, Tranderup, Ærø 1918

DFS 1906/134 (83). Brev fra Aage Sørensen, Mellerup. til Hans Engkilde 20.12.1935

DFS 1915/4 (7) Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremmes arkiv. Dansebeskrivelser og melodier: Ellen Grüner-Nielsen renskrift fra 1930. Indsamlingsrejsen august–september 1918

DFS 1915/4 (7). Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremmes Arkiv: Indsendt af Toxværd, Rasmus: Gamle danse fra Sydfalster–fire folioark med dansebeskrivelser, 13.2. 1917

DFS 1915/4 (8). Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremmes Arkiv: Egedal Johannes,—Folkedanse fra Falster og Lolland—samlede sommeren 1917 af J. Egedal, Korrektioner 1919

DFS 1915/4(7). Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremmes Arkiv: Brev fra Toxværd, Rasmus, dateret Væggerløse 16 3. 1917

DFS 1915/9: 26–27. Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremmes arkiv. Dansebeskrivelser og melodier: Beskrivelser af Mollevit, Den med Gabet og Kontra Mollevit optegnet af Ane Marie Kjellerup

DFS 1915/9: 26–27 Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremmes arkiv. Dansebeskrivelser og melodier: Brev fra kommunelærer J. Weber til lektor Vedel 27.8. 1948, brev fra Svend Clemmensen til Hans Nielsen Hjallese 3.10 48, brev fra Hans Andersen Hansen, Kalvehave pr. Dunkær, og Ane Marie Kjellerup

DFS Fonogram GD 149 (1915). Mollevit spillet af Johannes Munch, Fjellerup

DFS Fonogram GD 149 (1985). Jørgen Arnt. Telefonsamtale med A. C. N. Christensen. Fortalte, at der har været danset menuet i Allingåbro i 1932–33

DFS mgt. GD 1980/24–25, Albert Kjærgaard, Øster Tørslev, born in Mellerup, samtale med A. C. N. Christensen

DFS mgt. GD 1982/3–4. Samtale om menuet med Mette Christensen og Kirstine Brøndum, Randers, med A. C. N. Christensen 1.9. 1982

DFS mgt GD 1984 /117. Samtale med Ingeborg Therkildsen, Langagergaard, Rise på Ærø

DFS mgt GD 1984/126–127. Samtale om mollevit med gårdejer og spillemand Hans Albert Jensen, Skovby på Ærø, og A. C. N.Christensen

DFS mgt GD 1988/2. Samtale med folkedansinstruktør Skjold Jensen, Odense og A. C. N. Christensen

DFS video GD 1980/3. Inge Bonde Jensen, Støvring. Samtale med A. C. N. Christensen 20.10.1980

Various unpublished material

Arnt, Jørgen. telefonsamtale med A.C.N. Christensen. Fortalte, at der har været danset menuet i Allingåbro i 1932–33. (29.1.1985)

Brøndum, Niels, Ålum. Et brev med indlagte erindringer af Christen Lassen fra Bjerregrav, om bl.a. Søren Høgh, privat eje. (1999)

Jensen, Erik, tidligere mejerist og folkeanseoptegner. Samtale med Per Sørensen. Videobåndkopi, kamera Pia Sørensen. Sakskøbing, 1991

Kjellerup, Ane Marie, Nyborg. En samtale om sit liv som danser og folkedanseroptegner. Lydbånd og videobånd indspillet af Per Sørensen. Date unspecified

―, Nyborg. Telefonsamtale med A. C. N. Christensen om danseindsamlingen på Ærø. Date unspecified

Knudsen, Christen, pottemager. Samtale med A. C. N. Christensen, hvor oplysningerne stammer fra Johan Larsen, Rise (1984)

Rasmussen, Sara, Bregninge. Samtale med A. C. N. Christensen om sin afdøde mand Peter Henry Rasmussen (1984)

Secondary sources

Biskop, Gunnel, Menuetten — älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden — särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder — under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015)

Clemmensen, Kurt, Beretning om 19. Femaar 1991–1996. Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme. Kurt Clemmensen fortæller om faderens indsamlingsrejse til Ærø i 1948 (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1996)

‘Et Bondebryllup paa Ærø’, in Folkets Almanak (København: N. C. Rom, 1911), not paginated

Friis, Achton, De Jyders Land, Anden Udgave, 1. Bind (København: Grafisk Forlag, 1965)

Gamle Danse fra Fyn og Øerne, Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme. Samlet og beskrevet af Fru Ane Marie Kjellerup, Nyborg (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1941)

Gamle Danse fra Lolland-Falster, Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1. udgave. Indsamler Erik Jensen (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1960)

—-, Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 2. udgave, Beskrivelseskommission: Kurt Clemmensen, Morten Hansen, Anette Thomsen og Ole Skov (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1996)

Gamle Danse fra Randersegnen, Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, Andet Oplag (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1952). Gamle danse fra Præstø Amt, samlet af Elisabeth Andersen, 1939 (Fakse: Præstø Amts Folkedansere, F, 1954)

Grüner-Nielsen, Hakon, ‘Spørgsmaal om Folkedans’ in Lolland-Falsters Historiske samfunds aarbog V. (Nykøbing F., 1917), p. 151

‘Hansen, Hans A, musiker, Kalvehave. Nekrolog’, Ærø Avis, 30 December 1953

Koudal, Jens Henrik, ‘Dansemusik fra Struensees tid’, in Årsskrift 2000, Ærø Museum, vol. 7, ed. by Mette Havsteen Mikkelsen (Ærøskøbing: Ærø Museum, 2000), pp. 21–24

Kristensen, Evald Tang, Gamle folks fortællinger om det jyske almueliv IV (Kolding: Arnold Busck, 1891–93)

―, Jyske Folkeminder, Elvte Samling. Gamle viser i folkemunde (Viborg: F. V. Backhausen, 1891)

Lorenzen, Poul, ‘Et alvorsord om folkedansere, folkedragter og spillemandsmusik’, Hjemstavnsliv, 3 (1978), 49

―, ‘Folkedans i Danmark’, Aalborg Amtstidende, 15 April 1931

Østergaard, Niels Jørn, ‘Melodier fra tre Randerskomponister: Frands Bek, Søren Høeg, og Christian Telling’, in Nordjysk Folkekultur (Skørping: Foreningen for Musikalsk Folkekultur, 1997), [n.p.].

Østergaard, Peter, ‘Råby Hopsa’, in Historisk årbog fra Randers Amt 36 (Randers: Nørhald Egns-Arkiv, 1980), pp. 88–92

Skov, Ole, ‘Dansens rødder 33. Menuetten på Ærø nr. 2’, Hjemstavnsliv, 12 (1998), 10–11

―, ‘Tema Dansen og Musikkens Rødder 23. Menuetten på Falster-1’, Hjemstavnsliv, 1 (1998), 20–21

1 ‘Hansen, Hans A., musiker, Kalvehave. Nekrolog’, Ærø Avis, 30 December 1953.

2 DFS 1915/4 (7) Dansebeskrivelse og Melodier, renskrift 1930 af Ellen Grüner-Nielsens indsamling, Ærø 1918.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 ‘Et Bondebryllup paa Ærø’, in Folkets Almanak (København: N.C. Rom, 1911), [n.p.].

7 DFS 1906/43 1160 Fastelavnsskikke på Ærø. I.P. Lauritsen, Tranderup, Ærø 1918.

8 Christen Knudsen, Bregninge, Samtale med A.C.N. Christensen med oplysninger fra Johan Larsen, Rise.

9 DFS mgt GD 1984/126-127. Samtale med spillemand Hans Albert Jensen, Skovby, Ærø og A.C.N Christensen.

10 DFS 1915/4/7. Hakon og Ellen Grüner-Nielsens danse- og musikindsamling på Ærø 1918.

11 Ane Marie Kjellerup, lydbånd og videobånd med samtale om hendes liv som danser og folkedanseroptegner. Indspillet af Per Sørensen.

12 Ane Marie Kjellerup. Telefonsamtale om danseindsamlingen på Ærø med A.C.N. Christensen.

13 Gamle Danse fra Fyn og Øerne. Samlet og beskrevet af Fru Ane Marie Kjellerup, Nyborg (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1941), pp. 52–71.

14 Ibid., pp. 68–71.

15 DFS 1915/9/26-27. Breve fra Hans A. Hansen, Kalvehave, Ærø, og Ane Marie Kjellerup, Nyborg, til Svend Clemmensen.

16 Ole Skov, ‘Dansens og Musikkens rødder 33. Menuetten på Ærø 2’, Hjemstavnsliv, 12 (1998), 10–11.

17 DFS 1915/9/26-D27 FFF, Kjellerup.

18 DFS mgt GD 1988/2. Samtale om Mollevit fra Ærø med folkedanseinstruktør Skjold Jensen og A.C.N. Christensen.

19 Sara Rasmussen, Bregninge. Samtale om hendes mand, folkedansinstruktør Peter Henry Rasmussen med A.C.N. Christensen, 1984.

20 DFS mgt GD 1984/117. Samtale om mollevit med Ingeborg Therkildsen, Rise, og A. C. N. Christensen.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 DFS mgt GD 1984/126-127. Samtale om mollevit med spillemand og gårdejer Hans Albert Jensen, Skovby, Ærø, og A. C. N. Christensen.

24 Jens Henrik Koudal, ‘Dansemusik fra Struensees tid’, in Årsskrift 2000 (Ærøskøbing: Ærø Museum, 2000), pp. 21–24.

25 Gamle Danse fra Lolland Falster, 2. udgave, Samlet af: Kurt Clemmensen, Morten Hansen, Anette Thomsen og Ole Skov (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1996), p. 80.

26 Ibid., pp. 58–60.

27 Gunnel Biskop, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015), p. 200.

28 Hakon Grüner-Nielsen, ‘Spørgsmål om Folkedans’, in Lolland-Falsters historiske Samfunds Aarbog V (Nykøbing F.: Lolland-Falsters historiske Samfund, 1917), p. 151.

29 DFS 1915/4(7). Danseoptegnelser indsendt af Rasmus Toxværd, 1917, p. 4.

30 DFS 1915/4(7). Brev fra Rasmus Toxværd.

31 DFS 1915/4(7). Danseoptegnelser indsendt af Rasmus Toxværd, 1917, p. 4.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Ole Skov, ‘Dansen og Musikkens Rødder 23. Menuetten på Falster-1’, Hjemstavnsliv, 1 (1998), 20–21.

35 DFS 1915/4(7). Johannes Egedal, Folkedanse fra Falster og Lolland 1917 og 1918, p. 12.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Gamle danse fra Præstø Amt, samlet af Elisabeth S. Andersen 1939 (Fakse: Præstø Amts Folkedansere, F, 1954.

39 Erik Jensen, tidligere mejerist og folkedanseoptegner, samtale med Per Sørensen, Videobåndkopi. Kamera Pia Sørensen. (Sakskøbing, 1991).

40 Ibid.

41 DFS 1915/4(7), Johannes Egedal, p. 12.

42 DFS 1906/36 Danse og Dansemelodier, Mortensen, 1943, p.48.

43 Jensen.

44 Ibid.

45 DFS 1915/4(8), Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremmes Arkiv, Folkedanse fra Falster og Lolland, samlet af Johannes Egedal (1917), p. 26.

46 Ibid.

47 DFS 1906/36. Danse og Dansemelodier, Mortensen, 1943.

48 Achton Friis, De Jyders Land, Anden Udgave, 1. Bind (København: Grafisk Forlag, 1965), p. 227.

49 Poul Lorenzen, ‘Et alvorsord om folkedansere, folkedragter og spillemandsmusik’, Hjemstavnsliv, 3 (1978), 49.

50 DFS mgt GD 1982/3–4. Mette Christensen og Kirstine Brøndum f.1891, samtale med A. C. N. Christensen.

51 Poul Lorenzen, ‘Folkedans i Danmark’, Aalborg Amtstidende, 15 April 1931.

52 DFS mgt. GD 1982/3-4.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid.

55 Lorenzen, ‘Et alvorsord’.

56 Gamle Danse fra Randersegnen, Andet Oplag (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1952), pp. 36–41.

57 DFS mgt. GD 1982/3–4.

58 Ibid.

59 DFS mgt. GD 1980/24–25. Albert Kjærgaard, Øster Tørslev, born in Mellerup, samtale med A. C. N. Christensen.

60 DFS mgt. GD 1982/3–4.

61 Gamle Danse fra Randersegnen, p. 41.

62 DFS mgt. GD 1982/3–4.

63 Gamle Danse fra Randersegnen, pp. 36–41.

64 DFS video GD 1980/3. Inge Bonde Jensen, Støvring.

65 DFS mgt. GD 1982/3–4.

66 DFS mgt. GD 1980/24–25.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 Evald Tang Kristensen, Gamle folks fortællinger om Det Jyske Almueliv IV (Kolding: Arnold Busck, 1891–93), pp. 77–78.

70 DFS mgt. GD 1980/24–25.

71 Ibid.

72 DFS Fonogram GD 149. Jørgen Arnt (1985). Telefonsamtale med A. C. N. Christensen. Fortalte, at der har været danset menuet i Allingåbro i 1932–33.

73 DFS mgt. GD 1980/ 24–25.

74 DFS video GD 1980/3.

75 Ibid.

76 Ibid.

77 Peter Østergaard, ‘Råby Hopsa’, in Historisk Årbog fra Randers Amt 36 (Randers: Nørhald Egns-Arkiv, 1980), pp. 88–92 (p. 88).