12. Collecting Minuets among

the Swedish-speaking Population

in Finland

©2024 Gunnel Biskop, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.12

Among the Swedish-speaking population in Finland, the collection of dances began early. Victor Allardt was the first to document how the minuet was danced in Lappträsk in eastern parts of Nyland’s (Uusimaa) province. He responded in 1887 to a call from Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland [The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland] (SLS) to collect folklore. Allardt’s notes mostly describe the structure of the minuet.1

The Föreningen Brage i Helsingfors [Brage Association in Helsinki], founded in 1906 to promote Finnish-Swedish folk culture, carried out the actual collection of dances. As soon as the association’s folk-dance group started its activities, the same year the association was founded, it began to gather information about folk dances from its members who were students and others who moved to Helsinki from the countryside. In 1907, some people from Ostrobothnia taught a minuet and polska from the parish of Oravais in their province to be included in the play ‘Ostrobothnian Peasant Wedding’ by Otto Andersson. In 1910, two Ostrobothnian students taught the minuet in their home village: Anna Krook, born in Oravais, taught a minuet from Oravais and medical student Thure Roos, born in Kristinestad, taught a minuet from Lappfjärd.

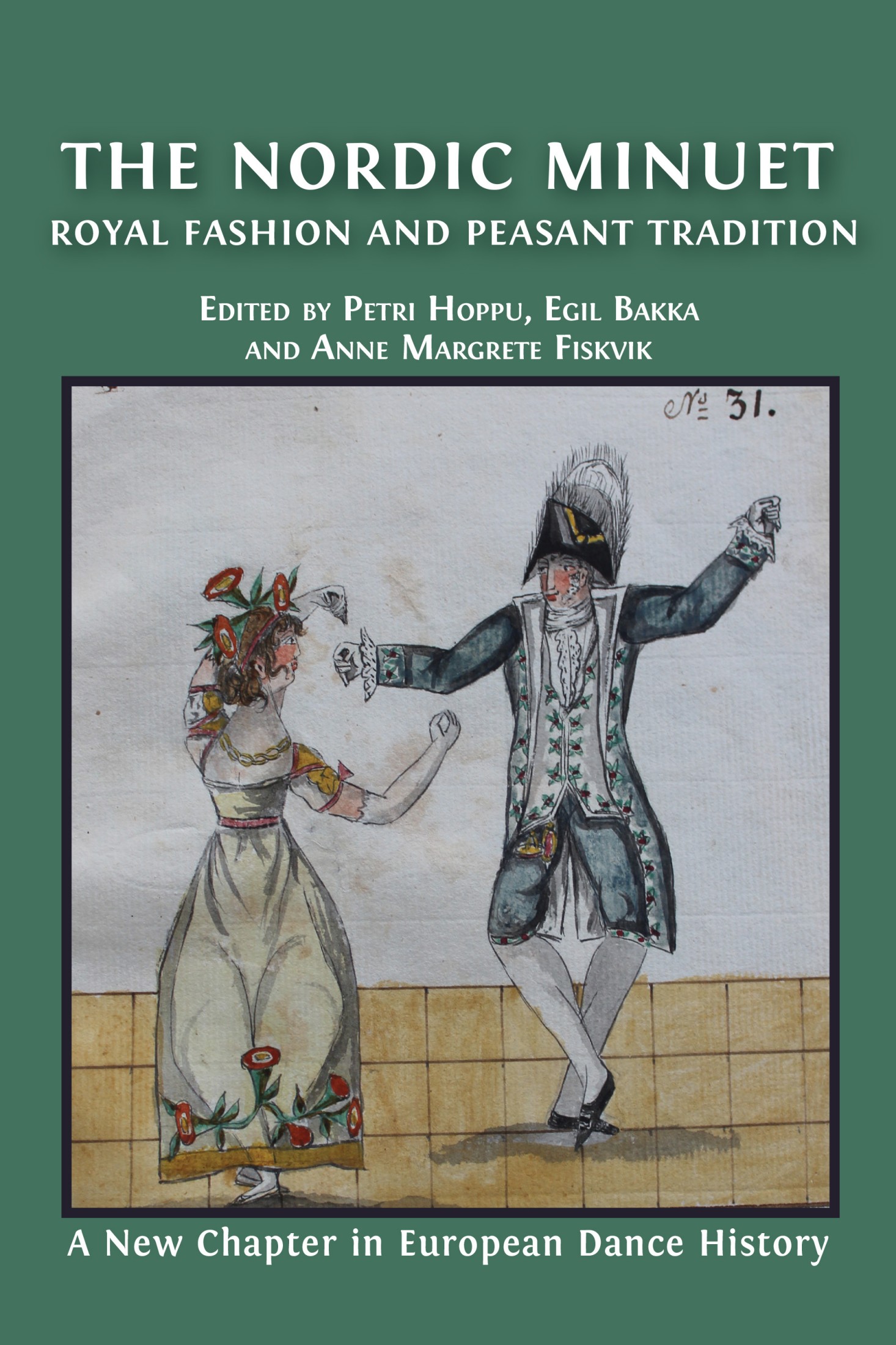

Fig. 12.1 The dance researcher Yngvar Heikel (1889–1956) documented minuets and other dances of the Swedish-speaking population in Finland. The Finnish Heritage Agency, https://finna.fi/Record/museovirasto.DF54F64E5EE3D64C2D53EBCC86B8EA27, CC BY 4.0.

The Brage Association sought to record the dances of a folk-dance group according to how the folk dancers danced them. The most challenging dance to both learn and to record was the minuet. Brage published a book called 36 Folkdanser [36 Folk Dances] (1915) that included both dance instructions and melodies. Its primary contributors were Yngvar Heikel, Thure Roos, and Holger Rancken. Among the thirty-six dances included in the book, six were minuets: three from Ostrobothnia and three from eastern Nyland.

It was later shown that the Ostrobothnian minuets were incorrectly described by Brage. The collectors had learned the minuets from young people who had never led the dance and therefore did not know how to describe its beginning. Their information about the starting beat for the minuet, among other things, was misinterpreted and, consequently, the description incorrectly insisted that the dance began with the left foot on the first beat of the bar. These minuets were excluded from later publications with dance descriptions.2

Yngvar Heikel Continues—with Paper and Pencil

Master of Arts Yngvar Heikel (1889–1956) made a strong contribution to the collection of dances in Swedish-speaking Finland. He was born in Helsinki to a father who served as director of the gymnastics establishment at the University of Helsinki. Heikel became a student in 1907, studying economics and mathematics then philosophy and the history of Finland and Scandinavia, graduating in 1915. He was a very active member of the Brage Association, acting as an occasional dance leader from 1910–19 and remaining its secretary from 1916 until his death. Beginning in 1921, he also worked as a statistician in various offices at the Bank of Finland. During the 1920s, he devoted himself to costume research and collected a significant amount of information about costume traditions in the Finnish-Swedish countryside.3

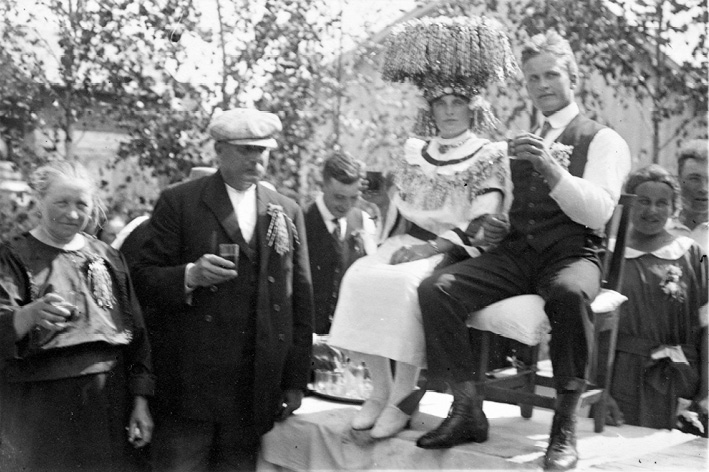

Fig. 12.2 Heikel visited Kimito in Åboland in the summer of 1924 and, by chance, came into contact with the members of the youth association. After them, he documented fifteen dances, among them minuet and polska. Photograph in Kimito by Otto Andersson (1904). SLS 105b_66. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.SLS+105+b_SLS+105b_66, CC BY 4.0.

After 36 Folkdanser was published, Heikel used what he learned to document other dances on his own. The book had given him great practice in recording dances with paper and pencil. He realized the importance of following each partner’s movements through the dance separately to capture the whole, often highly complex, dance pattern. Heikel had also built up knowledge of what figures could occur in different types of dances. The creation of 36 Folkdanser had given him the skills to continue documentation.

In the 1920s, during fieldwork trips to collect information about folk costumes, Heikel also collected information about dances whenever he had time. He recorded the ‘minett’, as the minuet was called in the eastern part of Nyland’s province. In 1922, Heikel organized a questionnaire for Brage that was sent to approximately three hundred fifty peasant musicians in all parts of Swedish-speaking Finland to solicit information about dances. About one hundred twenty-five people responded, supplying detailed and accurate information in many cases. Heikel was probably among the first in the Nordic countries to use a questionnaire as a method for the documentation of dances.4

Sometimes dances were documented accidentally. This was the case, for example, during Heikel’s folk costume fieldwork in Kimito in Åboland in the summer of 1924. He visited Kimito during a local song festival, where he expected to see many costumes. Simultaneously, Heikel was researching in Sagalund Ethnographical Museum, where he met the founder of the museum, a schoolteacher Nils Oskar Jansson (1862–1927). Jansson was also interested in old dances and had been teaching each generation since the 1890s. After the song festival, Heikel was invited to a dance hosted by the local youth association. Its members were Jansson’s students, and Heikel asked them to perform the old dances Jansson had taught them. Heikel documented fifteen dances at the event, among them the minuet and polska.5

Between 1921 and 1926, Heikel carried out seven folk costume fieldwork trips in Ostrobothnia, but during these trips he did not have time to document dances. Nevertheless, he wrote, some of his informants ‘talked about folk dances’. Heikel learned from them the order in which the minuets were danced during a ceremony at a wedding. Due to the lack of time, Heikel could not always record a dance in detail. This was the case when he received information about the minuet in Sideby in southern Ostrobothnia in 1924. He visited the eighty-seven-year old Olga Nummelin (b. 1837) who had been an instructor of old dances at a youth association. Heikel watched Nummelin dance the minuet while she sang the melody herself. Unfortunately, Heikel made no record of this minuet, so Nummelin’s knowledge of the dance has been lost to history.

In December 1926, Heikel was commissioned by Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland to publish the dances of Swedish-speaking Finland. Heikel realized that the existing collected material had to be supplemented, and he proceeded to undertake an extensive, seven-year collection expedition (1927–33). He rode a bicycle around all parts of Swedish-speaking areas in Finland, in the provinces of Ostrobothnia, Nyland, Åboland, and Åland, recording dances. He began in Ostrobothnia, where he had not previously completed much collection work.

|

|

Fig. 12.3a and Fig. 12.3b Heikel on a research trip. The bicycle was his means of transport through all of Finland’s Swedish-speaking parishes. The association Brage in Helsinki, 1922. @ Föreningen Brage.

Heikel provided many detailed descriptions of the minuet: these are so precise that they can be easily interpreted and danced today. Such records are from the parishes of Tjöck, Lappfjärd, Vörå, Oravais, Munsala, Jeppo, Nykarleby, Pedersöre, Purmo, Esse and Terjärv. In several parishes, he received conflicting details from multiple informants. In such cases, he included one complete record and, after that, noted only how the variants differed. Heikel received complete descriptions in Åboland—in Kimito and Nagu—as well as variants from different people. In Nyland, the most comprehensive accounts came from Lappträsk, Pyttis and Borgå in eastern Nyland.

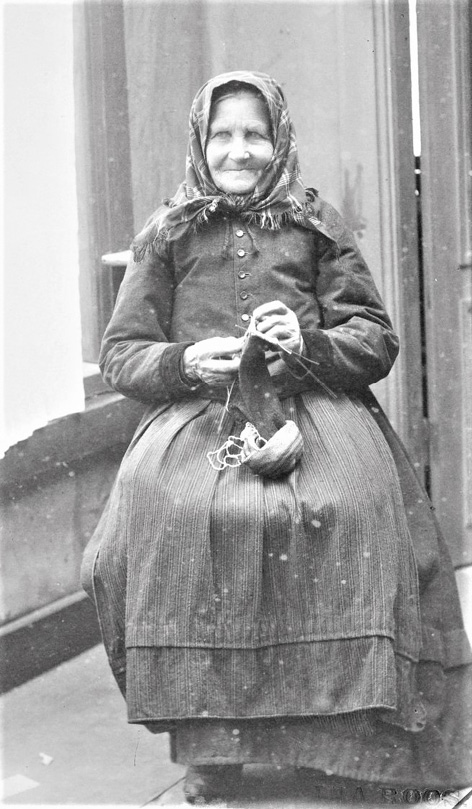

Fig. 12.4 During his research trip to Ostrobothnia, Finland in 1927, Heikel had the opportunity to attend a wedding, where some thirty minuets were danced on the first day, and even more on the second day. Here, a newlywed couple in Vörå in Ostrobothnia are seated on a table, receiving congratulations, in 1925. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. SLS 865 B 254. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_SLS+865+B+254, CC BY 4.0.

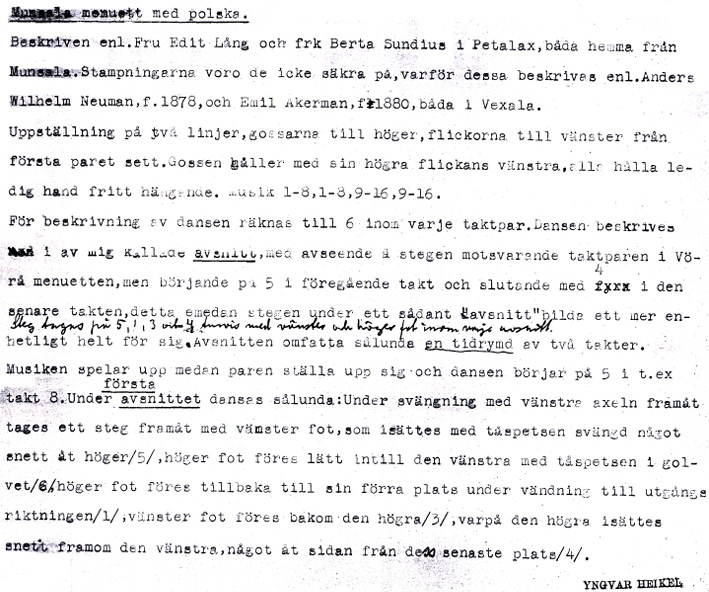

Heikel was extremely careful in his documentation work. He took notes on various details about how one informant’s dance differed from another’s. For example, from Munsala in Ostrobothnia, he collected six descriptions of the minuet from different informants. Heikel encountered the minuet twice in Munsala. First, during his folk costume fieldwork in 1925, he stayed in the parish of Petalax with a schoolteacher Oskar Langh (b. 1894) and his wife Edit (b. 1896 in Munsala). Heikel took general notes while Edit danced the minuet with her cousin, a schoolteacher Berta Sundius, who was also from Munsala. During his dance research trip in 1927, Heikel returned to the Langh couple, whom he called friends. Oskar, who played the dance melody, taught Heikel on this visit about how the minuet started, and about the relation between the dance and the music. Heikel also personally learned to dance the minuet and so was better able to write down its steps. Something he gained from two men in Munsala (b. 1878 and 1880) that he had not learned during his first visit was about the use of foot-stamping in the minuet. Edit and Bertha had not included the stamps when they performed the dance, since it was a movement performed exclusively by male partners. The women, consequently, were unsure about them.

Fig. 12.5 Tradition bearers in Lappfjärd in Ostrobothnia in Finland show the starting position in their minuet, 1973. Photograph by Kim Hahnsson. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

Heikel met various informants in Ostrobothnia. Some had come to feel that dancing was a sin and did not want to show their knowledge. Other informants were working at the time Heikel came to visit them. Some interrupted their work to show some dancing, but others did not. In Oravais, for example, Heikel called on Mrs. Brita Jusslin, who he had met during his earlier folk costume fieldwork. Jusslin and her daughter were not quite sure about the minuet, which was probably because men were, by custom, dance leaders in the minuet. The women tried to help Heikel find others who knew the dance better than themselves. He wrote:

One of them came to persuade an older woman who worked in a nearby potato field to dance the minuet for me. But that woman was stubborn, did not want to be ridiculed; she probably thought it was a sin to dance and did not come despite many persuasive attempts, so we retreated, angered by such an unusual lack of understanding.6

But Heikel did not give up. He eventually located someone willing to dance the minuet. Heikel remarked, ‘Then I got to Erik Alfred Knuters (b. 1878), who was said to be the best minuet dancer in the village and who danced with me while I was singing the melody’. In Vörå, he visited several old women to see the minuet: ‘some hesitated and did not want to, but a couple danced with me in a little cabin, just about big enough that we could be there’. He described another case in this way:

An older woman that was already sleeping, I met early the next morning when she was by a drying barn to thresh. After much persuasion, she came with another older woman and danced the minuet a couple of times to me on the log floor. Still, no one else was allowed to watch.

After this, the woman would not dance anymore.

Fig. 12.6 Tradition bearers in Tjöck in Ostrobothnia in Finland show the starting position in their minuet, 1984. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop. © Gunnel Biskop.

In a potato field in the village of Vexala in Munsala, Heikel found an eighty-seven-year old musician Jakob Fogel ‘who was immediately willing and invited me in, he took the fiddle and tried to dance. But he did not remember.’ Fogel’s son then gathered local youth to dance the minuet in the evening. At this performance, Heikel saw that ‘the people in their fifties had their distinctive way of stamping while the young people danced with violently many stamps.’

Fig. 12.7 During his research trips in the 1920s, Heikel talked to many elderly people. A woman in Tjöck, in Ostrobothnia in Finland, knits at the beginning of the twentieth century. Photograph by Ina Roos. The Finnish Heritage Agency, https://finna.fi/Record/museovirasto.E028AD9127125A7F2B5C5500868BC2C3, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 12.8 Two women in Tjöck in Ostrobothnia in Finland, show how

to take hand in hand in the minuet, 1928. Photograph by Yngvar Heikel.

SLS Folkmålskommissionen’s collection no. 5 © The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland.

Heikel cycled on and met two people in a potato field, aged seventy-three and sixty-three. He accompanied them to their house where they danced in their work boots and sang the melody themselves. In the parish of Kronoby, he met a woman who had danced the minuet, but she did not want to show it. She wanted to go to the chamber but Heikel held her arm with a gentle hand. When Heikel left off, she said, ‘Yes, goodbye now, but do not come here again’.7

Heikel observed differences in how much dancers turned their bodies in one direction or the other and in how stamping and clapping were used in the minuet. In Jeppo, he recorded seven different variations—as many as the number of informants he met. In practice, this meant that everyone had his or her own style. The differences were minor enough that people from different villages could dance the same dance together. Although dancers tended to follow a local way of dancing, they also developed individual styles.

Heikel sometimes mentioned that his female informants were unsure about the minuet. While recording the dances, he did not think about the fact that men were supposed to know and determine the different minuet figures. So, it is not surprising that the women were uncertain about them.

Fig. 12.9 Family in front of their farm in Vörå in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1923. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. SLS 865 B 381. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_SLS+865+B+381, CC BY 4.0.

During his fieldwork, Heikel made no notes about the minuet tunes. The folk music researcher Otto Andersson and others had previously recorded dance melodies between 1902 and 1907 in all Swedish-speaking areas in Finland, a total of over fifteen hundred melodies. Andersson published a selection of them, including two hundred and seventy-six minuets, in his volume Folkdans A 1 Äldre Dansmelodier [Folkdance A 1 Older Dance Melodies] (1963), which also contains polskas and polonaises. Of the minuets, one hundred and seventy-two are recorded as coming from Ostrobothnia, seventy from Nyland, twenty-six from Åboland, and eight from Åland.

Fig. 12.10 Yngvar Heikel’s description of the minuet in Munsala in 1927, prepared for the Swedish Literature Society, which demanded a rewritten version. SLS 503b, The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS). Photograph by Gunnel Biskop. © The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland.

In 1938, Heikel published Folkdans B Dansbeskrivningar [Folkdance B Dance Descriptions], which he had edited with scientific accuracy.8 Heikel released all of the available material, including the fragments, with the names of the dance and figures that the peasantry of the respective village had used. The volume comprises a total of seven hundred and ninety-seven dance documents, including variants and fragments. There were sixty-five records of the first or other special dances at weddings. From the following parishes Heikel has a total of fifty-eight records describing the minuet, some, however, fragmentary: Tjöck, Lappfjärd, Vörå, Oravais, Munsala, Jeppo, Nykarleby, Pedersöre, Purmo, Esse, Terjärv, Karleby, Kronoby, Kimito, Nagu, Hitis, Pyttis, Lappträsk, Borgå, Tenala, Snappertuna, Ekenäs, and Finström in Åland.

Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland demanded that Heikel’s material be written cleanly on a type machine, with the original notes not retained.

![Front page of the book Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning VI B. Dansbeskrivningar [Finnish Swedish Folk Poetry VI B. Dance descriptions] (1938).](image/12.11a_heikels_dansbeskrivningar_1938_biskop.jpg)

|

|

Fig. 12.11a and Fig. 12.11b Yngvar Heikel published his records in 1938 in volume VI Folkdans B Dansbeskrivningar. SLS 268, The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS). Photograph by Gunnel Biskop. © The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland.

Heikel’s work impacted the minuet, prompting it to flourish due to research and, later, documentation on film. Heikel also served as the editor of two later editions of dance descriptions, published by Brage for use by folk dancers, 30 Folkdanser [30 Folk Dances] (1931) and 45 Folkdanser [45 Folk Dances] (1949). The latter became the standard for use in the Finnish-Swedish folk-dance movement.9

Minuets Documented on Film

Engineer Kim Hahnsson (1920–99), a chairman of the Finlands Svenska Folkdansring (central organization for Swedish-speaking folk dancers in Finland) for twenty-seven years, pioneered the use of film for the documentation of folk dances, including minuets. Hahnsson may have been inspired in this endeavour by an international folk-dance symposium he attended in Bergen, Norway in 1970. In the years following, Hahnsson began to film vernacular dances, folk-dance performances, folk-dance events, and other related occasions.

The first minuet Hahnsson filmed was the minuet and the polska from Lappfjärd. Lappfjärd Spelmanslag [a local group of fiddlers] celebrated its tenth anniversary in 1973 by presenting a program of old wedding habits, and people from Lappfjärd danced their minuet, which Hahnsson and his wife Stina (1927–2006) watched. Inspired, they contacted the dancers and, in the following year, filmed them dancing the minuet and the polska. The accompanying music was recorded simultaneously on an audio cassette. Stina Hahnsson wrote a description of the dances following the recording and published it in Finlands Svenska Folkdansring’s journal Folkdansaren in 1974. The minuet had undergone some changes, including in its steps, since 1928 when Yngvar Heikel documented it.

Fig. 12.12 The engineer Kim Hahnsson documented folk dance on film, including minuets. Photograph by Stina Hahnsson, 1993. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

Fig. 12.13a and Fig. 12.13b Kim Hahnsson filmed the minuet in Munsala in 1985. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop after Hahnsson’s film. © The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland.

The next minuet Hahnsson filmed was in the village of Vexala in Munsala. He learned of this group after the folk musician Erik Johan Lindvall (1902–86) played his fiddle at a course for folk-dance instructors in 1975. Again, the music was recorded simultaneously on a c-cassette. Hahnsson met Lindvall again in the summer of 1983 and filmed what the fiddler remembered of the minuet.

Hahnsson filmed the minuet in Jeppo on 2 July 1977. People from Jeppo had practised their minuet to perform it at a folk music event in Nykarleby. As in Lappfjärd, the minuet danced there had changed in the five decades since Heikel had visited.

Hahnsson documented two further minuets on film—one in Oravais in the summer of 1980, the other in Munsala in the summer of 1985.

Fig. 12.14a, Fig. 12.14b, and Fig. 12.14c Kim Hahnsson filmed the minuet in Jeppo in 1977, when Jeppo residents performed at a party. Screenshot by Gunnel Biskop. © The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland.

Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland began documenting vernacular dances on film in 1977 under the guidance of its then-archivist, Master of Arts Ann-Mari Häggman.10 On 22 July, the group filmed the minuet in Lappfjärd and, during the same summer, they filmed the minuet in Jeppo with the same dancers who had danced at the aforementioned folk music event in Nykarleby three weeks earlier. The following year, 1978, saw the group film the minuet in Munsala.

The Folk Music Institute in Vaasa filmed the minuet and other dances at a public dance evening in Munsala in 1995, which had been initiated by Häggman.11

|

Video 12.1 Demonstration of a Jeppo minuet, polska, and Kockdansen (the Chef’s Dance) in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1977. Directed by Ann-Mari Häggman; music and dance by Jeppo Bygdespelmän with dancers. The minuet is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Uploaded by Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland [The Swedish Literature Society in Finland (SLS)], 7 May 2019. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/cb0156df |

Concluding Remarks

One can assume that the minuet among the Swedish-speaking people in Finland is well documented. Thanks to Yngvar Heikel’s extensive and detailed work, it is known how the minuet was danced in the early twentieth century. He revealed the complicated habits connected to the ceremonial dances at weddings. Later, film recordings provided insight into how the minuets were danced in the late 1900s.

References

Andersson, Otto, VI A 1 Äldre dansmelodier. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 400 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1963)

Biskop, Gunnel, ‘Från Brage till Heikel, Holm och Hahnsson — något om folkdansrörelsens betydelse för menuetten’, in Allt under linden den gröna. Studier i folkmusik och folklore tillägnade Ann-Mari Häggman 19.9.2001 (Vasa: Finlands svenska folkmusikinstitut, 2001), pp. 285–92

―, ‘Brages danslag skördar och sår’, in Brage 100 år. Arv — Förmedling — Förvandling, ed. by Bo Lönnqvist, Anne Bergman, Yrsa Lindqvist. Brage årsskrift 1991–2006 (Helsingfors: Brage, 2006), pp. 80–119

―, Dans i Lag. Den organiserade folkdansens framväxt samt bruk och liv inom Finlands Svenska Folkdansring under 75 år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2007)

―, Dansen för åskådare. Intresset för folkdansen som estradprodukt och insamlingsobjekt hos den svenskspråkiga befolkningen i Finland under senare delen av 1800-talet (doctoral thesis, Åbo: Åbo Akademi, 2012)

―, Menuetten — älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden — särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder — under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015)

Brage, 30 Folkdanser (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1931)

Brage, 36 Folkdanser (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1915)

Brage, 45 Folkdanser (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1949)

Folkdansaren, utgiven av Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 1974

Heikel, Yngvar, ‘På folkdansforskning’, in Brage Årsskrift 1926–1930 (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1931), pp. 46–53

―, VI Folkdans B Dansbeskrivningar. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 268 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1938)

―, På forskningsresor i svenskbygden. Brage Årsskrift 1974–1986. Med inledning och kommentarer utgiven av Bo Lönnqvist (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1986)

Häggman, Ann-Mari, ‘Filmen återger glädjen i dansen’, in Fynd och forskning. Meddelanden från Folkkultursarkivet 7. SLS 496 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1981), pp. 157–82

Lönnqvist, Bo, ‘Yngvar Heikel som fältforskare’, in Yngvar Heikel På forskningsresor i svenskbygden, Brage Årsskrift 1974–1986 (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1986), pp. 9–21

1 Gunnel Biskop, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015). The text is based on a chapter in the book and in the following: Gunnel Biskop, Dansen för åskådare. Intresset för folkdansen som estradprodukt och insamlingsobjekt hos den svenskspråkiga befolkningen i Finland under senare delen av 1800-talet (doctoral dissertation, Åbo: Åbo Akademi, 2012), pp. 281–87.

2 Gunnel Biskop, ‘Brages danslag skördar och sår’ in Brage 100 år. Arv—Förmedling—Förvandling, ed. by Bo Lönnqvist, Anne Bergman, Yrsa Lindqvist. Brage årsskrift (Helsingfors: Brage, 2006), pp. 80–119; Gunnel Biskop, Dans i Lag. Den organiserade folkdansens framväxt samt bruk och liv inom Finlands Svenska Folkdansring under 75 år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2007), pp. 35–59; Gunnel Biskop, ‘Från Brage till Heikel, Holm och Hahnsson—något om folkdansrörelsens betydelse för menuetten’ in Allt under linden den gröna. Studier i folkmusik och folklore tillägnade Ann-Mari Häggman 19.9.2001 (Vasa: Finlands svenska folkmusikinstitut, 2001), pp. 285–92.

3 Bo Lönnqvist, ‘Yngvar Heikel som fältforskare’, in Yngvar Heikel, På forskningsresor i svenskbygden, Brage Årsskrift 1974–1986 (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1986), pp. 9–21; Yngvar Heikel, VI Folkdans B Dansbeskrivningar. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 268 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1938); Yngvar Heikel, ‘På folkdansforskning’, in Brage Årsskrift 1926–1930 (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1931), pp. 46–53; Yngvar Heikel, På forskningsresor i svenskbygden. Brage Årsskrift 1974–1986. Med inledning och kommentarer utgiven av Bo Lönnqvist (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1986).

4 Biskop, ‘Brages danslag’, pp. 87–94; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 169–70.

5 Heikel, På forskningsresor, pp. 92–97; Biskop, Dans i Lag, p. 54.

6 Biskop, ‘Brages danslag’, pp. 90–94; Biskop, Dans i Lag, pp. 54–59; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 165–70.

7 Biskop, Menuetten, p. 169.

8 In the introduction of the volume, Heikel described the history of folk-dance research and folk dance in Finland, as well as the principles guiding his collection work and publishing. He systematized the material according to the form of the dance. For each group, he organized the variations in a landscape. Heikel wrote about the environment and function of tradition and paid close attention to the presence of dances in time and space. He also used the material he received in response to the 1922 questionnaire. Heikel also took great care in recording information about his vernacular sources. He described the age, occupation and home village of each informant and the social environment in which the dance was practised. The personal data was obtained as part of his own collection, and he was permitted to use the questionnaire and the information in the biographical department at the Brages Press archive.

9 Biskop, ‘Brages danslag’, p. 91–94; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 169–70.

10 Ann-Mari Häggman, ‘Filmen återger glädjen i dansen’ in Fynd och forskning. Meddelanden från Folkkultursarkivet 7. SLS 496 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1981), pp. 157–82.

11 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 171–72.