THE MINUET AS MOVEMENT PATTERNS

These chapters survey and analyze the movement patterns that are documented in the different historical sources described above. The standard minuet dance, le menuet ordinaire, and its derived social forms were taught to the upper classes in many European countries by dancing masters who sometimes made descriptions or notations. Additional descriptions come from twentieth-century folk-dance collectors. The question discussed here is how the different versions compare, and if and how the dance may have changed over time and from one geographical and social context to another.

As a conclusion, there is a discussion about how the source material can be viewed as a totality to enable principles of triangulation. What can we learn by combining the tools and theories used to study the mainly written material from the eighteenth century and the corresponding tools and theories used to study the folk material that is still available as movement practice?

14. Nordic Forms of the Minuet

©2024 Gunnel Biskop, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.14

The ‘standard’ minuet, which has its roots in the classic court minuet (also called the ‘ordinary minuet’, or le menuet ordinaire) from about 1700, has been the longest surviving minuet in the Nordic countries. In this ‘original’ version, the minuet step begins with the right foot, the music is in 3/4 time, and one minuet ‘step’ consisting of four foot movements carries over two music bars. This minuet step and the structure of the dance follows the shape of the letter Z. Information about how the various stages of the dance are signalled is found in descriptions of the minuets in Finland and Denmark. In Finland, accounts come mainly from the Swedish-speaking areas in Ostrobothnia and Åboland (Turku archipelago) and, in Denmark, from Jutland and Ærø. These minuet’s structure is essentially the same as that of the standard minuet, although they are danced to different melodies. I believe that the minuet reached the Nordic countries at a very early stage.1

The Ordinary Minuet in Finland

In Finland, the minuet was danced throughout the Swedish-speaking areas. In the Swedish-speaking regions of Ostrobothnia and the Turku archipelago, the minuet continued to be danced for so long that early-twentieth-century dance researcher Yngvar Heikel was able to record complete descriptions of several minuets. By ‘complete’, I mean that the descriptions are so detailed that they can still be interpreted and followed today. One of these minuets comes from Munsala in Ostrobothnia. At some point in time, a shift occurred among dancers regarding the musical beat on which the minuet step began so that older and younger dancers in the same community danced differently. The older generations continued to start the minuet with the right foot on the first beat of the first of the pair of bars (that is, 1:1), while the younger generations started with the left foot on the second beat of the second bar (that is, 2:2). Heikel emphasized the younger generation’s style of dancing.

Fig. 14.1a and Fig. 14.1b Tradition bearers in Munsala in Ostrobothnia in Finland dance their minuet, 1985. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop after film by

Kim Hahnsson. © The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland.

Here I will focus on the description from Munsala, which Yngvar Heikel recorded in its entirety. Although he did not write complete descriptions of those instances in which the informant started with the right foot on the beat (1:1), he did mention the difference as a variation of the 2:2 version.2 Heikel described the minuet from Munsala as follows:

Formation. Two opposite rows of dancers, gentlemen to the right, ladies to the left, seen from the first couple. A gentleman holds his right hand in the lady’s left hand; everybody has their other hand hanging free.

Note. To describe the dance, it is counted to 6 during two bars. The editor [Heikel] describes the dance as consisting of what he calls ‘sections’ [in Swedish: avsnitt], referring to a time space of two bars, beginning

on count number 5 of one bar and ending on count 4 in the next bar. This naming groups the steps into a coherent entity that allows them to be presented more clearly. The sections cover thus a timespan of two musical bars.3

In the first section, dance as follows. While bringing left shoulder forwards, step forwards onto left foot, with the toe pointing slightly to the right (5), touch toe of the right foot to the left foot (6), step on the right foot in its original place, while turning left shoulder back to former stance (1), step onto left foot behind right foot (3), step on the right foot in front of and slightly to the side of left foot (4).

In the second section, partners change places, maintaining handhold, and turning counter-clockwise as follows. Step on left foot forwards and past the right (5), step on right foot slightly in front of and perpendicular to the left foot (1), while turning to the left on the ball of the right foot. After completing the turn, step on the left foot behind the right foot (3) and take a step in place with the right foot (4).

During the third section, dance the same steps as in the first section.

In the fourth section, the same steps [as in the first section] are danced again, but with the difference that the left foot step on count (5) is taken diagonally forwards and to the left, release handhold on (3) and on the step with the right foot on count (4), turn halfway round to the right.

In the fifth section, Step left foot forwards and to the right of the starting position, turning completely to the right (5), touch right toe beside the left foot (6), step back with the right foot while turning halfway round to the left (1), step with the left foot to the left of the right foot while returning to original stance (3) and step with the right foot in place (4).

During the sixth and seventh sections, pass the partner on the left with the following steps. Step forwards with left foot (5), drag right foot past left foot (6) step forwards with right foot (1), drag left foot forwards past right foot (2), and step forwards with the left foot while turning left shoulder forwards (3), step forwards with the right foot while returning to start stance (4). Take a short step forwards with left foot (5), close right toe to left foot (6), step slightly to the right with right foot (1) and turn completely around to the left on ball of the right foot (1-2), step diagonally left with left foot (3) with right foot step diagonally past and to the left of left foot (4). The dancers are now standing approximately in their original places.

During the eighth section, dance the same steps as in the fourth section.

As described above for the fifth to eighth sections, this series of steps is repeated an even number of times, for example, two or four times, always passing partner on the left.

Then the same series is played two more times, the boys at the cross-over to and from their original place stamp hard with the left foot on count (5), stamp lightly with right foot on count (6), and again stamp hard with the right foot on count (1) in the sixth section. In other words, three quick stamps at the beginning of each cross-over. When they return to their original place, the boys clap their hands once on count (1) while turning on the right foot in the seventh section and count (1) in the eighth section when stepping back on the right foot.

In the following sections, dance the same steps as in the fifth section, but the boys clap hands once on count (1) when stepping back on the right foot, after which the left foot (3) and right foot (4) steps are taken as usual.

Thereupon take a right hand in right thumb hold with a partner, and dance one full turn clockwise over the following two sections, with the following steps: a step forwards with left foot (5), drag the right foot forwards past left foot (6), step forwards with the right foot turned to the right (1) make a full turn to the right on the ball of the right foot (1-2); after completing the turn, touch the left foot to the right foot (3) and take a step in place with right foot (4), then repeat these steps to return to start position. In the following sections, while maintaining the handhold, step diagonally forwards and to the left with left foot (5) and then drag right foot and touch right toe to the left foot, while turning about ¼ turn clockwise to stand close to each other with right thumb hold, tightly bent arms and elbows pointing down. Step backwards with right foot (1), step backwards with left foot (3), step with the right foot slightly to the right of its last position (4), and the dancers are back in their original positions. During the following two sections, dance one full turn counterclockwise with a partner, maintaining handhold and with the same steps as in the second section at the beginning of the dance, dancing the steps twice to return to their original places. During the subsequent two sections, the same steps as in the third and fourth sections are danced, releasing the handhold on count 3 in the fourth section.

Hereafter, the series of steps, as described for the fifth to the eighth section, is repeated an even number of times, after which they are repeated twice with the same stamps and claps as in the middle of the dance, after which the steps to the right are danced with a clap when stepping back on the right foot on count (1), then step left foot on count (3), and right foot on count (4) as described above. Then the dancers take one step with their left foot towards a partner (5) touch right foot to the left foot (6), after which the boy takes the girl’s left hand in his right and ‘turns off’ the dance, that is to say, swings their joined hands a couple of times in a small circle clockwise from the boy’s point of view. Then they dance polska.4

The minuet’s length was not predetermined. Rather, the male dancer at the top of the set, closest to the table of honour (the ‘head-table male’) decided when to give signals for a switch to the next stage.5 The minuets described from other parishes in Ostrobothnia and the Turku archipelago are similar in structure.

Fig. 14.2a and Fig. 14.2b Tradition bearers from Munsala in Ostrobothnia in Finland have dressed in folk costume to perform their minuet in Stockholm, 1987. Photograph by Stina Hahnsson. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

The Ordinary Minuet in Denmark

It is often apparent from the accounts that early researchers found it difficult to describe the minuet. The problem was the same in Denmark. There, Ellen Grüner-Nielsen did not understand the minuet on Ærø in 1918, but, based on her notes, Ane Marie Kjellerup was able to complete the description in the late 1930s. Kjellerup’s description was published in 1941 and was further supplemented by Svend Clemmensen in 1948.6

Fig. 14.3 Folk dancers in Denmark perform with a minuet from Randers in Jutland, 1950. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

Fig. 14.4 Folk dancers perform the minuet from Randers at the Nordic folk dance convention in Aarhus, Denmark in 1946. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

Kjellerup’s revised description of the minuet on Ærø, with sheet music, was published in the second edition of Gamle Danse fra Fyn og Øerne (1941). The description was intended for use by folk dancers and differs markedly from Heikel’s method of describing the minuet. The minuet on Ærø is described by Kjellerup as follows:

Step: Mollevit steps in Ærø Mollevit.

One Mollevit step is always danced over 2 bars of music and always starts with the right foot. The steps must not be stiff but a little bouncy and lilting. There are 3 different Mollevit steps, namely: forwards, backwards, and in place.

Forward step: 1 step forwards followed by a small pause on the right foot, followed by 3 small steps forwards (L R L), followed by a pause on the last step (L).

Backward step: like the forwards step, only danced backwards.

The step in place: 1 small step backwards and a pause on the right foot, close left foot to right foot but a little farther back, lift right foot slightly from the floor and set next to L, 1 step forwards and pause with L foot while turning the body slightly to R. (left shoulder forwards), and touch R foot beside L foot.

Formation: all couples in a row with right sides to the front.

The Man (M) with the Woman’s (D) left hand in his hand.

|

Prelude. |

||

|

Music |

||

|

1–8 |

Men and Women bow and curtsy respectively; the women bowing more than curtsying. |

|

|

Introduction. |

||

|

1–2 |

||

|

3–4 |

||

|

5–6 |

||

|

7–8 |

everyone dances 1 Mollevit Step backwards, dropping the handhold. |

|

|

The dancers now stand in 2 rows, the gentlemen to L and the women to the R seen from the front, with a small space between the two rows. — The Mollevit itself can begin. |

||

|

9–10 |

FIG. I. |

All dance 1 Mollevit step diagonally to the L, finishing facing own partner and L shoulder to the next opposite dancer on the left’s L shoulder, i.e., men are half-turned to face the front, and women are half-turned with their backs to the front. |

|

11–12 |

1 Mollevit Step diagonally back to the R to return to start position. |

|

|

13–14 |

FIG. II. |

1 Mollevit step straight forwards, passing partner on the L (facing partner when passing), |

|

15–16 |

again 1 Mollevit step forwards while turning halfway round to the L. Finish in front of own partner, on L foot and L shoulders towards each other. |

|

|

9–10 |

FIG. III. |

|

|

11–12 |

||

|

The dance continues with Figs. I, II, and III, for as long as desired, until the lead dancer (Man 1=head-table male), the next time he begins Fig. I, i.e., he must have his right side turned to the front, says to the men: “Shall we?” Then on the 1st step, he claps his hands. This can occur, e.g., when Fig. I begins for the 5th time. |

||

|

1–4 |

FIG. I. |

1 Mollevit step diagonally to L (Man 1 clapping on count 1). |

|

Instead of dancing Fig. II, now dance: |

||

|

5–8 |

Giving R hand to partner, dance ½ turn clockwise, 2 Mollevit steps. Hands at shoulder height; partners close together. |

|

|

1–2 |

FIG. III. |

|

|

3–4 |

||

|

5–8 |

FIG. I. |

1 Mollevit step diagonally forwards to the L and 1 Mollevit step diagonally backwards to the R. |

|

9–12 |

Turn again with a single handhold, this time giving partner L hand, ½ turn counter-clockwise, 2 Mollevit steps. |

|

|

13–16 |

FIG. III |

|

|

The dance continues, as in the beginning, with Figs. I, II, and III until man 1 again gives the signal, which this time means that the dance will end. This can occur, e.g., when Fig. I is about to begin again for the 5th time. |

||

|

1–4 |

FIG. I |

|

|

Instead of Fig. II, now dance as follows: |

||

|

5–8 |

Partners take two-hand hold, and dance 1 full turn clockwise, 2 Mollevit steps, on the last beat making a deep bow and curtsy to partner, and the dance is finished. |

|

|

As is evident, it can end at quite a random place in the music, depending on how many times Figs. I, II, and III are danced. Throughout the dance, the women hold out their skirts. The Mollevit is usually followed by a waltz.7 |

||

This minuet from Ærø strongly resembles the standard minuet from the 1700s—namely, it includes the initial reverences and the initial formation transition into two lines.8 In the standard minuet, women and men stood side by side after the initial reverence, after which the man led his lady in a half-circle to face him, dropped the handhold, and the steps of the minuet proper began. Here in Ærø, this is evident. Women and men stand next to each other and use eight bars for the reverences and eight bars for the lady and man to move into position opposite each other in two lines. Vestiges of this movement also remain in Finland in the minuet danced in Lappfjärd, and less so in that of Tjöck in Ostrobothnia.

|

Video 14.1 Minuet and polska from Lappfjärd in southern Ostrobothnia in Finland, performed by folk dancers from the regional folk-dance organization Östra Nylands Folkdansdistrikt. The minuet is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Uploaded by Pargasit, 28 January 2013. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/55c38f65 |

|

Video 14.2 Minuet and polska from Tjöck in southern Ostrobothnia in Finland, performed by folk dancers from the group Spjutsunds folkdanslag under the instruction of Lisbeth Ståhlberg. The minuet is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Uploaded by Pargasit, 31 July 2013. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/016d02a6 |

Other Forms of the Minuet in the Nordic Countries

In addition to the standard minuet, later types of minuets were also danced in all the Nordic countries. These are variations that likely were fashionable at some time but did not survive long enough to be documented in detail in the early 1900s. Most of the following information comes from Finland. In my opinion, these later minuet variations did not gain popularity in the Swedish-speaking communities in Finland because the standard minuet had such a significant and important role in the ceremonial dancing at peasant weddings.

‘A Modern Minuet’ and no ‘Boorish Slängpolska’

A diary from 1811 offers the earliest information about how the minuet was danced in Finland. The relevant entry shows that the minuet in question was different from the standard minuet. Its author, Eric Gustaf Ehrström, was the first in Finland to explain, in a few words, how the minuet was danced.

Ehrström was born in 1791 in Larsmo in Ostrobothnia, where his father Anders (b. 1744) was a minister. His father came from Närpes and had first studied at Uppsala and later in Turku. His mother (b. 1757) was the daughter of a minister and came from Storkyro, Ostrobothnia. In 1805, the Ehrström family moved to Kronoby. Eric Gustaf and his brothers were schooled by their father until 1807 when Eric Gustaf was enrolled as a student at the Åbo Academy University at the age of fifteen.

While studying in Turku, Ehrström worked as a tutor for Krogius, a lawyer with six children. For six weeks in the summer of 1811, the his patron family stayed in Hauho in Tavastland with the patriarch’s sister, who was married to Dean Ivar Wallenius. Ehrström, just turned twenty years old, accompanied them in his position as tutor. In Hauho, there were forty ‘mansions’—residences of the well-to-do—where the young man participated in the lively social environment of the Swedish-speaking ‘gentry’. His diary contains detailed daily entries that Ehrström addressed to ‘a good aunt’ living in Storkyro. The diary’s purpose, he wrote, was to ‘record those things that especially attract my attention’. Ehrström could also play the violin and had learned to dance the minuet at home. His diary provides evidence that the minuet was being danced in the areas of Jakobstad, Kronoby, and Gamlakarleby in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Ten days after arriving at Hauho, on 26 June 1811, most of the gentry were invited to a peasant wedding in the village of Kokkila, the population of which was Finnish-speaking. The wife of Dean Wallenius had assumed responsibility for dressing the bride. The wedding took place on Prustila farm in Kokkila. The groom was from another village called Lehdesmäki. Ehrström described in detail the clothing and customs of the peasantry. About the wedding, he recorded:

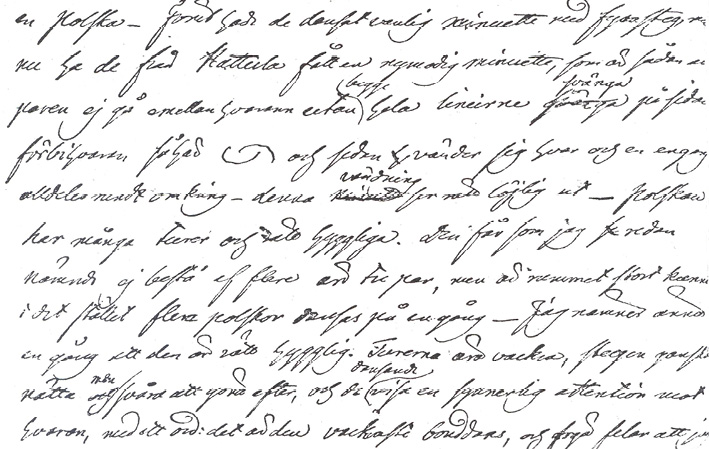

As soon as the bride was dressed and the guests gathered, the wedding was held—followed by a meal. The meal lasted from 12 o’clock to 5 o’clock, because only one group at a time ate. The first group consisted of the gentry, the young couple, and as many of the bridegroom’s family as there was room for. After eating, which did not take much time, we got up, and another group took our place despite many dishes being served. This continued until all the guests had eaten. The bride’s family served at the table and did not eat with the guests at all. Once the first group had eaten, the dancing started in another cottage. Relatively few rituals were observed. No dance could consist of more than three couples.—Everyone should dance the minuet and a polska with his partner. Initially, they had danced the usual minuet with four steps, but now they have learned a modern minuet from Hattula, in which the couples do not cross over between each other, but both lines together swing sideways past each other after which everybody turns completely around—which looks quite ridiculous.9 The polska has many sequences and is quite lovely. As I mentioned, it may not consist of more than three couples, but several polska sets can be danced at once if the room is large. I repeat that it is quite lovely. The sequences are beautiful, the steps quite dainty but challenging, and the dancers pay careful attention to each other. In one word: it is the most beautiful country dance, and it is no exaggeration to say it the most beautiful dance I’ve ever seen. I sense Aunt laughing, but come here, dear Aunt, and see it, and Aunt will agree with me, and happily take my hand when I invite Aunt [to dance it]. Aunt must not imagine it to be a boorish slängpolska, but a lively, modest, and attentive dance, in which, just as in a quadrille, one gets to rest occasionally as another couple takes its turn. Towards 8 p.m., the young newlyweds and the whole wedding party left on the journey for the bridegroom’s home in Lehdesmäki.10

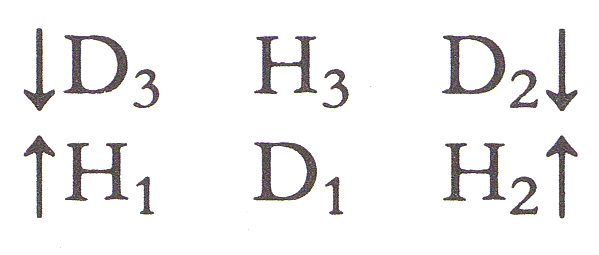

Fig. 14.5a A few lines from Eric Ehrström’s manuscript with the detail (on the fourth line from the top), about how the two lines of dancers swung past each other. This information was omitted when the diary was published in 2007. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop. © Åbo Akademi University, Manuscript department.

Fig. 14.5b Eric Ehrström’s drawing illustrating how the dancer lines exchange places. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop. © Åbo Akademi University, Manuscript department.

Ehrström felt that there were few ceremonies at the beginning of the dancing, probably he had experienced longer ceremonial wedding dances in his home region of Ostrobothnia. The first dance was a minuet and a polska, which, he emphasized, were danced by three couples at a time. Ehrström knew how to dance the ‘usual minuet’—the standard minuet from 1700 with ‘four steps’. So, too, did the aunt in Storkyro to whom he addressed his text; he did not need to clarify. The new minuet which was danced, which the aunt did not know, he must explain as well as possible, even including a sketch. Ehrström described how the two lines of three people each do not pass through each other but instead the lines ‘swing sideways past each other’, and then each person turns around individually. It can be interpreted as if the dancers completed a full circle. He thought it looked ridiculous; he had not seen anything like it before.

The polska was also danced by the three couples and had many sequences, which all of the dancers in the set did not dance at the same time. Instead, sometimes some couples stood still and rested while another couple danced something, as in a quadrille. The steps were complicated for Ehrström to follow. In addition to the complicated nature of the movements, the steps and the sequences in what he understood to be the polska were new to him. Therefore, there must have been other steps and another variation of the polska than the one he had danced in Ostrobothnia and called a ‘boorish slängpolska’, with which, we can assume, the aunt was also familiar.

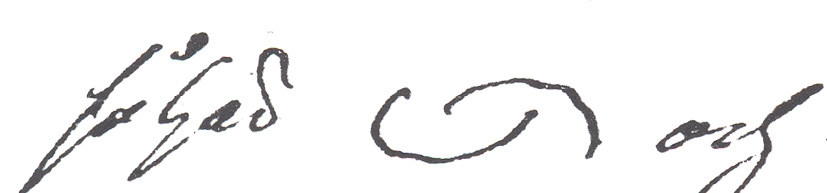

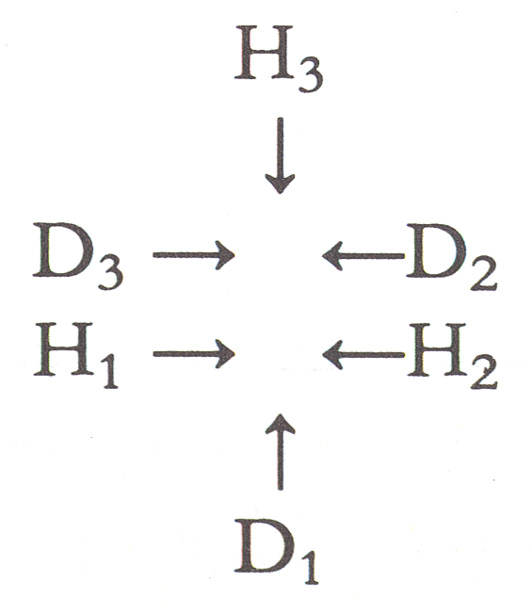

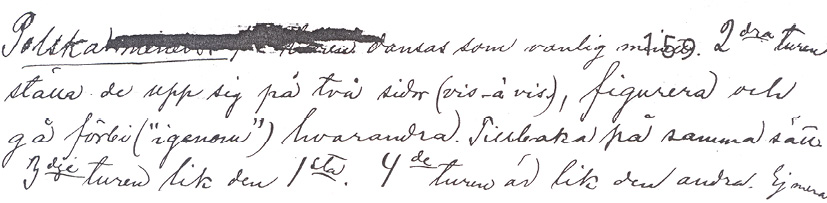

Ehrström stressed that there were three couples in a set. Such a model of the minuet explicitly danced by three couples, on which this could have been based, was described by Karl Heinz Taubert in his book Das Menuett (1988). There, the variation is called ‘Minuet en six’ 11. According to Taubert, it was devised by Ernst Christian Mädel (b. 1776) in Erfurt, Germany and published by him in the book Tanzkunst für die elegante Welt (1805). Mädel’s minuet is structured like a contradance with eight sequences of ‘verse and chorus’, in which both ‘verse’ and ‘chorus’ are danced with minuet steps, but which differ from the standard minuet step.

The initial formation in the ‘Minuet en six’, according to Taubert:

Fig. 14.5c The starting position in Menuet en six, according to Taubert. Design by Petri Hoppu.

Formation in the chorus of the Minuet en six, according to Taubert:

Fig. 14.5d The arrangement of the chorus in Menuet en six, according to Taubert. Design by Petri Hoppu

The dance was so unusual that it may have been difficult for Ehrström to understand which parts constituted a ‘verse’ and which portions were the ‘chorus’. Ehrström may have perceived the chorus as a polska with ‘many sequences’. The chorus in Taubert’s ‘Minuet en six’ consists of four parts. The first part is a chain, or double figure of eight, danced by the two outermost persons [in each line], while the two people in the centre ‘rest’, as Ehrström expressed it. In the second part, the two people in the centre of each line dance a figure eight while the other four dancers rest. These elements fit well with Ehrström’s description. The third part, called the ‘triumphal arch’, includes the people in the same line changing places with one another, which is somewhat reminiscent of Ehrström’s diagram. That sequence also includes ‘battements’ which traditionally consisted of high kicks. Ehrström explained that the steps in the polska were challenging to complete, probably because he had not previously learned battements. The fourth sequence is danced in the lines and includes half a turn to one’s partner. Ehrström wrote that the dancers turned ‘completely around’. I do not find any reference to this movement in Mädel’s minuet: it does, however, included a turn under raised arms, but otherwise only a quarter and a half turn. Taubert also wrote that one could vary the minuet by turning around completely.12 It is also possible that the minuet Ehrström described was based on some other minuet, which is not included in Taubert’s book.

This documentation of the minuet and polska in Finnish-speaking Kokkila in 1811 is remarkable and raises several issues, regardless of the dance’s particular variation. The bride and groom, their relatives and friends, and the villagers were in a Finnish-speaking peasant environment within which everyone could dance the minuet. Whether or not the twenty-year-old Ehrström himself danced is not mentioned. Even the Swedish-speaking ‘gentry’ or upper class could dance it, though it was not typically danced at their gatherings. The Hauho ‘gentry’ included a deputy judge, a captain, and a colonel, with their respective families.

Two days after the wedding, about twenty young people, all of whom Ehrström identified in his diary, were invited to the home of Dean Wallenius. He wrote that they danced, ate, and played all day, but did not mention which dances were danced. This is likely because, from Ehrström’s point of view, the dances were the usual ones and did not need to be specifically named. We see, from an ‘addendum’ to another account, however, that the Hauho ‘gentry’ danced ‘Quadrille and Angloise’ and, on one occasion, a further quadrille was danced. Why did the upper classes here abandon a new dance, the new minuet, so quickly? At the same time, how did it happen that the peasantry adopted the new minuet so quickly? An answer to the latter question may be that the neighbouring parish to Hauho—Hattula, near Tavastehus—was, in Ehrström’s words, ‘a conduit through which luxuries and regrettable customs gradually flow into the rest of Tavastland’.13

Fig. 14.6 Ordinary people in Tavastland on their way into the church.

R.W. Ekman, Churchgoers (1868), gouache on paper. Pori Art Museum, Finland. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:R_W_Ekman_Kirkkoon_k%C3%A4vij%C3%A4t_1867.jpg, public domain.

It is not important whether or not Ehrström could distinguish between the different parts of the dance or if he could distinguish the minuet from the polska, even though he could play music. He mentioned nothing about the music; it was not something that caught his attention. Folk music researchers Tobias Norlind and Otto Andersson have suggested that minuets and polskas cannot always be distinguished one from the other.14 What is important is that Ehrström clearly stated that the dance was new, that it was a three-couple dance, and that what he regarded as the ‘polska’ had many sequences and that the steps were difficult to dance (which suggests that he did not already know the steps). The most remarkable thing, in my view, is that a new dance, possibly devised in Germany around 1800 and first published in 1805, could be competently danced by the Finnish-speaking people in Kokkila in Tavastland, Finland in 1811, only six years later. Since all the wedding guests could dance it, including the groom and his relatives who came from Lehdesmäki, the dance must have been known in those villages for some time. If I have interpreted Ehrström correctly, that at least parts of the ‘Minuet en six’ were being danced in Finland, this information would contradict all previous theories as to when the minuet may have reached Sweden or Finland. It would also contradict existing theories about the routes by which dances were spread. My interpretation suggests that dances did not always come via the cities or even via the upper classes. Instead, it indicates how quickly a dance could be introduced by, for example, a dance teacher or a Hattula resident who might have stayed or perhaps studied in Germany. Or maybe a merchant, or some professional person, who had lived for a while in Europe? None of these scenarios is far-fetched.

Because Ehrström wrote about things that ‘particularly’ attracted his attention, he did not write about anything he considered usual. The dances popular among the gentry were usual, so he did not name or describe them. Whether or not the minuet he saw was the ‘Minuet en six’ really does not matter. Either way, the above argument suggests conclusions about the speed of dissemination.

In Denmark, versions of the minuet known as ‘Mollevitt 3’ are mentioned in accounts from the late 1860s. The informants remember it as dance with two different formations—one in two lines and the other in three lines, in which each gentleman had two ladies. Three sources from Norway also report that there were three people, not three couples, in the minuet, suggesting that this version also existed there.15

Minuet and Polskaminuet—Different Variants

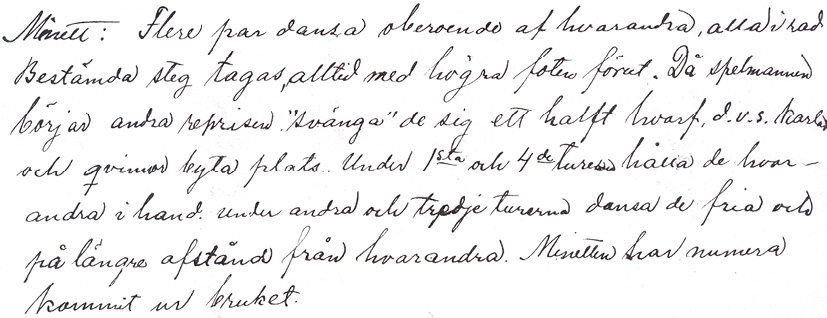

Fig. 14.7a and Fig. 14.7b Victor Allardt’s record of minuet and polska-minett in eastern Nyland, Finland, 1887. SLS 1009. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS). Photographs by Gunnel Biskop. © The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland.

In eastern Nyland (Uusimaa) in Finland, the minuet was called ‘minett’ and was danced until the latter part of the 1800s. Another minuet form emerged in this region around 1860 with the name ‘polskaminett’. As I have pointed out earlier, my opinion is that newer forms of minuet gained popularity in places where the standard minuet did not have a ceremonial role in peasant weddings. This argument is supported by the following information from eastern Nyland, an area in which the minuet did not play such a significant role.

Victor Allardt, a schoolteacher in Lappträsk, encountered the minuet and polskaminuet in the 1880s when he notated dance melodies played by folk musician Hans Jakob Hansson (b. 1836) in Lappträsk. Allardt tried to describe how the two variants were danced. Whether he relied on information from Hansson or saw, possibly danced, these minuets himself, is not made clear. About the minett in Lappträsk in 1887, he wrote:

Several couples dance independently of each other, all in a row. Specific steps are taken, always with the right foot first. When the musician starts playing the second repeat, they ‘turn’ a half-turn, that is to say, men and women change places. During the 1st and 4th parts, they hold each other’s hands. During the second and third parts, they dance individually and farther away from each other. The minett is seldom danced now.16

The minuet step itself was perhaps too difficult for Allardt to describe in words, but we are told that it begins with the right foot. He described holding hands at the beginning, changing places, and also holding hands at the end. During the ‘second and third parts’, when dancing further away from each other, it is likely that after the women’s and men’s lines had changed places and released the handhold, and some minuet steps were subsequently danced on the other side of the set before returning to the original side. Allardt does not mention the number of minuet steps at any stage of the dance. Nevertheless, characteristics of the standard minuet are apparent. When the description was later enhanced, it became evident that it was the standard minuet.17

Allardt’s 1887 account of the second minuet, the Polishminuet (polskaminett), which appeared later, is as follows:

The first part is danced like a regular minuet

In the second part, they form two lines (vis-a-vis), figuré, and change places. [The dancers] return the same way

The third part is the same as the first

The fourth part is similar to the second. No more.18

It’s difficult to know how to interpret this description. I would interpret that ‘Ordinary minuet’ refers to women and men taking minuet steps towards each other. In the second part, I understand that the couples stood side by side in two lines and danced a figuré, suggesting that there were at least two couples in the set, with each couple facing another couple, as in a contradance. When Yngvar Heikel and Holger Rancken published a more detailed description of the polskaminuet in Lappträsk in 1912, they noted that ‘in this minuet the transition steps are danced as a kind of figuré’, with four walking steps.19 The polskaminuet involved no turning or swinging of the partner either in the beginning, middle, or at the end of the dance; further, four minuet steps were danced in place before the transition. All of this evidence gives the impression that this polskaminuet was a contradance.

Heikel provided two descriptions in which the dancers took four minuet steps towards each other before changing places. He has flagged one such description from Pyttis with a question mark. This may have been a polskaminuet. In Pyttis, the minuet was followed by ‘Storpolska’, a four-couple quadrille formation. The traditional Storpolska, following the minuet (in eighteen sequences), consisted of typical quadrille ‘verse and chorus’ sequences with a chain, without taking hands, as a chorus. It would seem logical that the minuet was for a set of four couples since a four-couple quadrille followed it or that two sets of two couples joined together for the Storpolska. As a model for the polskaminuet, I think the ‘Minuet en quatre’ might have been for two couples or the ‘Minuet en Huit’ for four couples.20

No variant of the polska occurs in the description, despite the name ‘polskaminett’. However, in Denmark, there are also references to a quadrille being danced following the minuet. Types of Polsk-minuet are also mentioned both in Denmark and Sweden. On Fyn, in Denmark, both ‘Mellevett’ and ‘Polsk Melevet’ are mentioned, but no descriptions of how they were danced are available. It is possible that these were two different variants specific to the area of eastern Nyland in Finland. In Sweden, Nils Månsson Mandelgren in Skåne also mentions both a minuet and a ‘Pålsk-Mölevitt’. The polsk-minuet, it seems, become known in the area in the 1860s.21

Fig. 14.8 A minuet may be danced in a ring. Elias Martin, Dans på Sveaborg [‘Picnic’ at Sveaborg] Fortress in Finland (1764), ink drawing. National Museum, Stockholm. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dans_p%C3%A5_Sveaborg_1764.jpg, public domain.

Unpublished Descriptions of the Minuet in Finland

In his work Dansbeskrivningar [Dance Descriptions] (1938), Yngvar Heikel included not only complete dance descriptions but also incomplete descriptions, fragments, and mere mentions of dances. Therefore, it is both surprising and interesting that, as I shall next discuss, he made notes of, but left out of the publication, some information pertaining to the minuet. He presumably doubted the authenticity or veracity of the information, considering them unreliable. Yet Heikel could not have been familiar with certain variations of the European minuet, with their different formations and steps, since many of the sources available to today’s researchers did not exist in Heikel’s time or were not as readily accessible. I will analyze the notes here as Heikel wrote them; the sources are in his archives at Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland.22 Because his notes include the minuet steps and the starting formations of the dances, I will work through whether there were possible models among Europe’s fashionable dances for the dances described by his informants.

Heikel has two notes relating to quadrille sets. One relates to an account from Karl Hagert (b. 1859), a folk musician and land owner, in Sjundeå in Western Nyland. Heikel commented that the minuet Hagert described was like a quadrille in formation. Probably because Hagert admitted that he had seen this minuet danced only three times, Heikel flagged this information with a question mark.23 The second note is from Pernå in eastern Nyland. Heikel commented that a woman (b. 1866) had only seen, never danced, the minuet but that she thought:

[…] that they [the dancers] stood in a square and that the girls from one side and the boys from the other first danced towards each other, followed by the other boys and girls from the same two sides. The steps started on the right foot, the women held out their skirts, they curtseyed and bowed, took one another by the hand, and turned around. She did not remember anything else.24

Both of these notes may refer to a sequence in the ‘Minuet en huit,’ in which four couples dance in a square set and included the typical sequences of quadrille dances. Comparable formations in a square set, in which some sequences are danced with minuet steps, have been documented in Denmark.

From Pojo in Western Nyland, Heikel was provided more information which seems to show that two couples were needed to dance a minuet. According to the informant, the owner of Pehrsböle farm, Heikel attempted in 1897 to ‘get old people to dance minett, two couples were supposed to dance it, but one person refused, so nothing came of it’.25 Perhaps it was a polska-minuet because this could not be danced by only one couple.

From Borgå in eastern Nyland, there are two notes about the minuet step. One informant (b. 1867) described the steps completely different from those in the ordinary minuet. Unfortunately, Heikel did not note the description of the steps but instead said that the woman was not sure of them. He explained:

[She] specified that the steps were first taken to the sides starting to the left, then in a zigzag diagonally backwards, then in a zigzag forwards, then on the left past their partner with a turn to the right in the partner’s place, after which the whole series was repeated so that you returned to your original position. Then they went forwards, took their partner by the right hand with a thumbhold, and turned clockwise, after which the same series of steps were repeated, and then the dance ended.26

It is possible that the dancers’ steps to the left puzzled Heikel. This pattern of steps is more reminiscent of the Z-form minuet from 1700 than of the step pattern in other minuet choreographies. In the Z-form minuet, which Heikel presumably did not recognize, the first steps are danced sideways to the left. The dancers move forwards on the left past the partner to the opposite side, and the steps are repeated. Dancers also turn while holding hands with a partner. A minuet step backwards is included in a minuet by the choreographer Rameau from 1725. Also, Taubert described the minuet step backwards, as well as explaining the minuet steps to the side and forwards.27 In Sweden, there are some details in Mandelgren’s description of the minuet in Skåne, which are reminiscent of the Heikel’s note above, such as, ‘each in opposite directions or forwards or farther apart backwards’.

The second note from Borgå in eastern Nyland is from the same informant. She mentioned that an old man wrote a figure ’8’ in the sand with his toe when he danced the minuet. It should be noted that the first version of the minuet, from the 1600s, followed a figure-eight pattern. Is it possible that this form of the minuet reached Borgå, Finland’s second-oldest town? It may be possible since, at that time, Finland was part of Sweden. Alternatively, the woman may have been describing a version of the minuet that Eric Gustaf Ehrström mentioned as having been danced in Hauho, in 1811. If so, the ‘Minuet en six’ might be its inspiration. That minuet was danced by six people in two lines. In that version, participants dance a chain, without holding hands, and follow a path in the form of an eight. During the execution of the chain, it would be possible to draw an ’8’ in the sand with the toe. The minuet step is the usual type.28

From Nagu in the Turku archipelago, there is evidence of another different minuet about which Heikel also has not recorded much detail. His male informant (b. 1845) had danced the minuet but forgotten the steps. Heikel’s recorded the following information:

They held each other by the right hand at the beginning of the dance and in the middle. When he was going to dance the minuet step, he alternately crossed one leg in front of the other, crossed over on the left, turned to the right, and took the steps without reference to the beat. After the minuet came a polska.29

According to Taubert, a cross-step was included in a minuet choreographed by Gottfried Taubert (no relation), who published a dance book in 1717. In this version, when a dancer steps to the left, the right foot is crossed either in front of or behind the left foot. Taubert pointed out that this dance teacher is the only one in the Baroque period who allowed the dancer to choose whether to cross in front or behind the weight-bearing foot.30 From Finström on Åland, the 1960s researcher Viking Sundberg described a minuet with some similar step based on information from an informant born in 1882.31

From Hitis in the Turku archipelago, there is a description of a dance that begins in a circle. Heikel had received a letter from Erik Isaksson (b. 1869), a bank director and folk musician. Because Heikel does not cite the letter itself, but only makes reference to it, it may mean that Heikel did not believe that Isaksson’s information could be correct. Heikel wrote:

The minuet was called minett. He had seen the minuet danced a few times, the last time in November 1886 at a wedding, when four couples in their 60s and 70s danced it. He thinks that all the couples first danced around in a circle but supposes that may be wrong. Then the women stood on one side and the men on the other. They formed couples holding each other by the left hand and began the steps with their right foot, but he did not remember which direction. He thinks that the dancers passed their partner on the right side and held hands with a thumbhold at least once during the dance, maybe on each side. Some light handclapping occurred, but no stamps, nor lifts onto the toes, but instead knee flexes, and occasionally the women held out their skirts. Bows and curtseys towards each other occurred, and both at the beginning and the end, everyone bowed to the musician. Afterwards, they danced a polska.32

The beginning of the dance is reminiscent of an English dance called the ‘Sabina’. Dating from 1726, the Sabina includes a longways set formation for eight couples with a women’s line and a men’s line that includes minuet steps.33 From Replot in Ostrobothnia, there is also a description that indicates that the minuet at some stage of the dance was danced in a circle. In 1898, Wilhelm Sjöberg, a folklife researcher, notated a minuet tune sung by Fredrika Gädda. She remembered that ‘you first stood in two lines, which moved towards each other, and then in a second sequence, some of the dancers formed a circle’.34

H. A. Reinholm also made a note of a minuet from southwest Finland that began in a circle. Even in Denmark, there is a corresponding variant of a minuet in which dancers moved in a circular formation.

In Karleby in northern Ostrobothnia, Johan Werner Björk (1884–1967), noted a minuet that seemed to begin in a circle. Björk was studying at the University of Helsinki to be a physical education teacher, and at the same time, performed folk dances with Föreningen Brage [the Brage Association]. There he had, among other things, learned the minuet and gained an understanding of how the minuet was danced. He was also inspired to revive the minuet in Karleby, but the attempt failed when the young dancers could not learn the steps. In 1910, Björk recorded information about a minuet from Matts Heikkilä (b. 1838) who, in the 1860s and 1870s, had his own ship and traded with Stockholm. According to Björk’s notes, the minuet Heikkilä remembered was danced as follows:

Everybody [starts] in a big circle, the girls on the inside. On the [second count, all dancers] lift onto the toes, hands in front of the chest, the second time above the head. On four, [they] bow and curtsey [to their partners]. When the partners change positions, elbow to elbow, [dancers] walk in a semi-circle, looking at each other politely. [Then they] march in four directions. [Then they form a] big ring in polska rhythm, [for] two to three bars. Then [the dancers’ group] splits into two, [and] repeat. [More of the couples break away from the circle, until it is] down to two couple sets and then [all dancers return] back to the big circle.35

Probably a minuet step was taken at some point since Björk considered the dance a minuet. The starting formation is a big double circle, with the women on the inside. This may indicate some sequence in a contradance as well as the mention of ‘march[ing] in four directions’—similar elements are found in a four-couple cotillion. The first half of the dance is a gigue [jig] and the other half is danced with minuet steps.36 The sequence that might be the origin of the dance that Heikkilä mentioned which started with couples standing side by side in an open circle, and then the women were brought in to form one circle. References to ‘the hands in front of the chest, the second time above the head’ may indicate a sequence from a dance called allemande. According to Björk’s note, this was followed by a dance in polska rhythm in a big circle, the big circle being divided into progressively smaller circles, down to two couple circles, and ended when everyone joined in one big circle again. No similar form of polska has been found in Ostrobothnia. One might speculate if Heikkilä had learned a ‘modern’ dance during his business trips to Stockholm.

We do not know what form the minuet had in the dances described in these unpublished notes. What we can see is that different fashionable versions of minuets also reached Finland. These versions spread and were danced by the population in the Swedish-speaking countryside.

To Twirl—a Way to Vary the Dance

In Chapter 6, it was explained that in Lappfjärd and Tjöck in Ostrobothnia, two minuets were danced one after the other as a part of ceremonial dances and that in the second minuet, one dancer turned (twirled) individually, that is, turned around after taking the cross-over step(s). This I have interpreted to mean that dancers varied the second minuet by turning after the cross-over step to emphasize that they were dancing two different minuets.

Fig. 14.9a and Fig. 14.9b Tradition bearers in Tjöck in Ostrobothnia in Finland twirl in their minuet at an event in Stockholm in 1987. Photographs by Stina Hahnsson. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

This twirl was not unique to Lappfjärd and Tjöck but is also mentioned by informants in Oravais. There it was called ‘vingla på Jepo’ [stagger to Jeppo], which, in turn, may indicate that the turn was used also in Jeppo. Taubert mentioned that one could introduce variations in the minuet, among other things, by turning around individually. In the turn, one could use different steps, of which he provided examples, and with varying numbers of steps so that the turn was faster or slower. For example, the turn may be executed over four counts with a quarter-turn on each count.37 The origins of this turn are uncertain, but it may be that it was taken from the minuet variant described by Eric Gustaf Ehrström in his diary in 1811, as discussed above.

Fig. 14.10 Common people in Nyland in Sunday dress, c. 1808. Watercolour by C.P. Elfström. The Finnish Heritage Agency, https://finna.fi/Record/museovirasto.EDC778A5BFA4727EB8E5BC4D51C2ABF0, CC BY 4.0.

The Minuet in Contradances in Denmark and Hard-to-Interpret Notes from Sweden

Minuet steps have been included as a sequence or part of other dances, including contradances. In Denmark on Lolland-Falster, the minuet is part of ‘menuet med pisk’ [minuet with a whip, a couple dance], ‘Lang Minue’t [longways minuet, a longways set], and ‘Rund Minuet’ [round minuet, danced in a large circle].38 On Ærø, the minuet forms part of ‘Den med Gabet i’ [the one with a break in it, a quadrille] and in ‘Kontra med Mollevit’ [contradance with a minuet, also a quadrille], the latter being also mentioned on Bornholm.39 Another dance from Bornholm, the ‘Longsomma Gjärted’ [slow Gertrude, a longways set] also had minuet steps added later.40

Some notes and descriptions from Sweden are difficult to understand. Those from Skellefteå landsförsamling and from Skåne by Mandelgren, for example, are so unclear that it is a challenge to decipher how the dances might have been danced. An archive called the Philochoros Collection at Uppsala University Library includes another such description of a minuet. This description is from Luleå, and was composed by a Parliament member named Bergström in the summer of 1883. The cryptic description explained:

No introduction, two to six couples:

Original formation to the audience, leading the lady into place, bow and curtsey to partner [Struck out: ‘Two lines of men and women, facing’. On the opposite page is a drawing showing a men’s line and a women’s line]

1) Balancé back and forth

2) Traversé giving hands and return to place

3) [Struck out: ‘the whole line dances the same step’] starting with the right foot [Struck out: ‘step starting with the left foot’] traversé

step starting with left, and traversé giving hands, etc. (Left hand?)

[Struck out: ‘Reveranse’] Traversé giving two hands. Reverénce: balancé with two hands, left hand released, greeting the audience

Greeting to partner41

This account may have been recorded by Gustaf Sundström, who was from Norrland and was dance leader for the Philochoros folk-dance group, which consisted of students at Uppsala University. Features of the standard minuet are apparent: the initial formation beside one’s partner, the man’s bow to his partner, leading her to stand opposite him, thus forming a women’s line and a men’s line, and then the man and the woman switching positions with one another and returning to their original places. At the end, men released the left hand for a bow to the audience and the lady. The fact that the potential author of the note (Sundström) used French terminology could indicate that he had attended dance classes and had learned the French terms from a dance teacher who used them. It is equally possible that Bergström, the informant, had participated in dance classes in order to learn both the dance and the terminology, giving him the ability to describe the minuet using these words to Sundström.

Mixing the Minuet and Polska

Some dance and music researchers believe that the minuet and polska were mixed.42 Their observations often refer to the music, but they are not explicit about this. On the contrary, my research has not revealed any points of mixing in the dance forms anywhere in the Nordic countries during the time the minuet and the polska were part of the living tradition. Musically, the minuet and the polska have been closely related since the beginning of the 1700s, and several researchers have pointed out that minuet tunes were transformed into polska tunes. In my opinion, when the two dance forms fell out of use in large parts of the Nordic region, the melodies continued to survive, as they still do today.

Without the support of the dances, mixing and conversion within the music became possible. On the other hand, other minuet forms not directly derived from the ordinary minuet have not been transformed, such as polska-minuet. This I do not construe as mixing. Furthermore, the inclusion of minuet in sequences of some other dances, including both English longways set dances and quadrilles, I do not see as evidence of mixing between minuet and polska.

Concluding Remarks

Throughout the Nordic region, the ordinary minuet has been the most common minuet form and the one with the greatest longevity. The prevalence of that form did not hinder later forms of the minuet from achieving popularity; minuets in both square and circle formations have been danced. Considering where the latter forms have occurred, one can see that there are regions in which the minuet did not play a significant, ceremonial role in peasant weddings.

References

Archival material

Åbo Akademi University, Manuscript department

Eric Ehrström, diary

Folklife Archives (LUF), Lund University

Mandelgren’s collection: 366

Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland (SLS) (The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland), Helsinki

SLS 526:5, 17, 1009:155, 519:2, 530:7, 503:30, 530:19, 525:19, 525:16, 530:42, 66:71

Uppsala University Library

Philochoros collection: nr18 F9:3

Secondary sources

Andersson, Otto, VI A 1 Äldre dansmelodier. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 400 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1963)

Beskrivning av Åländska Folkdanser (Mariehamn: Ålands Ungdomsförbund, 1982)

Biskop, Gunnel, ‘Menuett i fyrkant eller i ring—också hos oss?’, in Folkmusik i förändring. Folk och musik 1996 (Vasa: Finlands svenska Folkmusikinstitut, 1996), pp. 67–90

―, Menuetten — älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden — särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015)

―, ‘Om svängningen i menuetten i Tjöck’, in Folkdansaren, 52.1 (2004), pp. 10–14

Christensen, Anders Chr. N., ‘Monnevet og Mollevit. Menuettraditioner på Randersegnen og på Ærø’, in Folk og Kultur. Årbog for Dansk Etnologi og Folkemindevidenskab (København: Foreningen Danmarks Folkeminder, 1999), pp. 94–126, https://tidsskrift.dk/folkogkultur/article/download/65922/94852

Ehrström, Eric, Minnen af en Resa från Åbo till Tavastland år 1811. SLS 688 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2007)

Gamle Danse fra Fyn og Øerne. Samlet og beskrevet af Fru Ane Marie Kjellerup (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1949)

Gamle Danse fra Lolland–Falster, 2. udgave (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1996)

Heikel, Yngvar, VI Folkdans B Dansbeskrivningar. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 268 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1938)

Norlind, Tobias, Svensk folkmusik och folkdans, Natur och kultur 96 (Stockholm: Stockholms Bokförlag, 1930)

Rameau, Pierre, The Dancing Master, trans. by Cyril W. Beaumont ([1725]; Alton: Dance Books, 2003)

Skov, Ole, ‘Dansens og musikkens rødder 33. Menuetten på Ærø — 2’, Hjemstavnsliv, 12 (1998), 10–11

Taubert, Karl Heinz, Höfische Tänze. Ihre Geschichte und Choreographie (Mainz: B. Schott’s Söhne, 1968)

―, Das Menuett. Geschichte und Choreographie (Zürich: Pan, 1988)

1 Gunnel Biskop, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015). (The Menuet—The loved Dance. About the minuet in the Nordic region—especially in the Swedish-speaking area of Finland—for three hundred and fifty years). The text is (in the main) based on a chapter in the book.

2 For information about how Heikel’s descriptions were compiled, see Chapter 11.

3 During each section, steps are taken in turns with left and right foot at 5, 1, 3, and 4, and the steps at 5 and 1 are taken as a rule with a small knee bend continuing at 6 and 2 respectively. When the other foot is taken to or past the first foot at 6 and 2, this is done with a light dragging on the floor. When the music starts, the couples place themselves in the dance formation, and the dance begins at 5, for example, during bar number 8.

4 Yngvar Heikel, VI Folkdans B Dansbeskrivningar. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 268 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1938), pp. 28–29; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 233–38.

5 See the detailed discussion on this in the section on the minuet in Finland.

6 Ole Skov, ‘Dansens og musikkens rødder 33. Menuetten på Ærø—2’, Hjemstavnsliv 12 (1998), 10–11; Anders Chr. N. Christensen, ‘Monnevet og Mollevit. Menuettraditioner på Randersegnen og på Ærø’, in Folk og Kultur. Årbog for Dansk Etnologi og Folkemindevidenskab (København: Foreningen Danmarks Folkeminder, 1999), pp. 94–126, https://tidsskrift.dk/folkogkultur/article/download/65922/94852 ; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 239–43.

7 Gamle Danse fra Fyn og Øerne. Samlet og beskrevet af Fru Ane Marie Kjellerup (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1941), pp. 68–71; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 239–43.

8 These features were not retained as clearly in the minuets in the Swedish-speaking areas of Finland.

9 The publisher, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, has omitted the sketch in the published edition, which I am including from the original manuscript that is available at Åbo Academy.

10 Eric Ehrström, Minnen af en Resa från Åbo till Tavastland år 1811. SLS 688 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2007), pp. 163–68, pp. 44–46; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 257–68.

11 Karl Heinz Taubert, Das Menuett. Geschickte und Choreografhie. Pan 168 (Zürich: Pan, 1988), pp. 43–50; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 259–261.

12 Karl Heinz Taubert, Höfische Tänze. Ihre Geschichte und Choreographie (Mainz: B. Schott’s Söhne, 1968), p. 182. Biskop, Menuetten, p. 260.

13 Ehrström, Minnen af en Resa, p. 48, p. 42; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 257–61.

14 Otto Andersson, VI A 1 Äldre Dansmelodier. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 400 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1963), p. CXX.

15 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 257–261.

16 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 261–63; SLS 1009.

17 Heikel, p. 8.

18 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 262–63; SLS 1009.

19 Heikel, p. 9.

20 Taubert, Das Menuett, pp. 70–76.

21 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 211, 214.

22 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 264–67; SLS 519; SLS 530; SLS 503; SLS 525; SLS 225.

23 Ibid., p. 264.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Pierre Rameau, The Dancing Master, trans. by Cyril W. Beaumont ([1725]; Alton: Dance Books, 2003), p. 54; Taubert, Das Menuett, p. 84.

28 Biskop, Menuetten, p. 265.

29 Ibid.

30 Taubert, Das Menuett, p. 85.

31 Biskop, Menuetten, p. 265; Beskrivning av Åländska Folkdanser (Mariehamn: Ålands Ungdomsförbund, 1982), p. 60.

32 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 265–66; SLS 530.

33 Taubert, Das Menuett, pp. 66–68.

34 Biskop, Menuetten, p. 266; SLS 66.

35 Gunnel Biskop, ‘Menuett i fyrkant eller i ring—också hos oss?’, in Folkmusik i förändring. Folk och musik 1996 (Vasa: Finlands svenska Folkmusikinstitut, 1996), pp. 67–90.

36 Taubert, Das Menuett, pp. 57–60.

37 Biskop, ’Menuett i fyrkant eller i ring’, pp. 67–90; Gunnel Biskop, ‘Om svängningen i menuetten i Tjöck’, in Folkdansaren 52.1 (2004), 10–14; Heikel, p. 25; Taubert, Höfische Tänze, p. 182.

38 Gamle Danse fra Lolland-Falster, 2. udgave (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1996).

39 Gamle Danse fra Fyn og Øerne. Samlet og beskrevet af Fru Ane Marie Kjellerup (København: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1949).

40 Oral assignment by Anders Christensen on 11 February 2006.

41 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 107–08; Uppsala universitetsbibliotek, Philochoros collection.

42 For example, Tobias Norlind, Svensk folkmusik och folkdans, Natur och kultur 96 (Stockholm: Stockholms Bokförlag, 1930), p. 134; Andersson, VI A 1 Äldre Dansmelodier, p. 120.