15. Minuet Structures

©2024 Petri Hoppu, et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.15

This chapter examines the steps, figures, and overall structure of the ordinary minuet and its Danish and Finnish variations. A common narrative used to explain the minuet’s emergence is that it evolved from a French folk dance called the ‘Branle de Poitou’. Dance teacher and historian Melusine Wood claimed that the originating dance was, more precisely, Branle á Mener de Poitou, a group dance with one couple at a time acting as a leading couple. In this dance, the dancers moved in a chain following the leading couple, creating a serpentine figure on the dance floor while dancing.1 Wood suggested that the original minuet was danced by one couple at a time with similar steps and figures as in Branle á Mener de Poitou and that the serpentine figure evolved gradually into the ‘Z-figure’, the most important aspect of the dance which came to be called the minuet.2

This interpretation has been popular among dance history enthusiasts but it has also frequently been disputed, because, according to Julia Sutton, there is little real evidence to support it.3 Music scholar David Tunley also has cast doubts on the link between the minuet and Branle de Poitou.4 Other dances have been suggested as the minuet’s potential predecessors. Karl-Heinz Taubert argued that the ceremonial introductions and closings, as well as the bounces and rises, were brought to the minuet from the courante, Ludvig XIV’s favourite dance.5 Sutton, for her part, believed the minuet’s possible Italian origins to be the most persuasive interpretation. Unlike Wood, she hypothesized that the S-figure that preceded the Z-figure may have arrived in France with Italian dancing masters as early as the mid-sixteenth century. However, Sutton thought that any evidence concerning the geographical and chronological origins of the minuet figures was circumstantial, and there was no way to find conclusive proof for any theories about them.6

Le Menuet Ordinaire

The ordinary minuet, le menuet ordinaire, was introduced in 1700 by Louis Pécour.7 Previously it had undergone several decades of development, especially by the most famous seventeenth-century dancing master, Pierre Beauchamp, at the French court. According to Karl-Heinz Taubert, the minuet’s main figure was first in the shape of an ‘8’, then it later changed to a ‘2’ or left-facing ‘S’; only in Pécour’s version was it changed it to a ‘Z’.8

Minuet Steps

The minuet consisted mainly of the basic step pas de menuet [minuet step]. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the minuet step reached the form that can be called ‘classic’, though with different variations. Gottfried Taubert named these pas de menuet en fleuret and pas de cour. In addition, new steps were developed throughout the eighteenth century.9

A minuet step has six counts, and therefore it uses two bars of music. This step contains four placements of the foot, or transfers of weight, and two bendings of the knee, called pliés. The minuet step is a pas composé [compound step], which means that it comprises two or more basic steps. The first part of the step is a demi-coupé: a step, and a plié. The second part of the minuet step is a pas de bourré: three steps and a plié. The minuet step always starts with the right foot for both the woman and the man, independent of which direction it is performed, whether it is forward, backward, to the right, or to the left.

The minuet step can be described like this [with counts noted in brackets]: one step forward with the right foot on the first count in the music [1], plié on the right foot on the second count [2], three steps forward on the third, fourth, and fifth counts [3–5] using a left foot, right foot, left foot pattern, and a plié on the left leg on the last count [6]. This ‘step’ is called the pas de menuet à deux mouvements because it contains two pliés. One mouvement consists of an élevé (a stretching of the leg while the dancer rises up onto the ball of the foot) and a plié.10 This vertical movement is what in the Norwegian folk-dance terminology is called svikt.11 The basic structure of the pas de menuet is presented in Table 15.1.

Table 15.1: The basic structure of the minuet step

|

Bar |

Count |

Movement |

|

|

1: |

1 |

1 |

Step with right foot |

|

2 |

2 |

||

|

3 |

3 |

Step with left foot |

|

|

2: |

1 |

4 |

Step with right foot |

|

2 |

5 |

Step with left foot |

|

|

3 |

6 |

There are a significant number of variations on the minuet step where the steps and the pliés are organised in different ways during the bar, for example, the pas de menuet un seul mouvement, pas de menuet en fleuret, and pas de menuet à trois mouvements.12 Pas de menuet à trois mouvements has a third mouvement on counts 5 and 6: a pas jété [a small jump]. Variations on the minuet step show different ways of elaborating a basic step by using different rhythms. Such varieties in marking the music create dynamics and tension in the relationship between the dance and the music.

Karl Heinz Taubert identified the basic pas de menuet as a hemiola since the even rhythmic movement (2+2+2) breaks the triple rhythm of the music (3+3).13

The Basic Form

Several European dancing masters describe the ordinary minuet. Some of the most central descriptions are those by English dancing master Kellom Tomlinson and German dancing masters Gottfried Taubert and Carl Joseph von Feldtenstein, in addition to Rameau.14 The ordinary minuet had a standardised form of six figures, presented in Table 15.2.

Table 15.2: The basic form of le menuet ordinaire

|

Introduction |

|

|

Presentation of the right hand |

|

|

Presentation of the left hand |

|

|

Presentation of both hands |

In the first figure, the introduction, the partners hold hands and perform the first steps forward, and then they move around in a circle in the middle of the floor. After the circle is completed, they let go of their hands and move in opposite directions on a diagonal to end the figure standing in opposite corners.

Figure number two, the Z-figure, is the main part of the dance. In this figure, the partners begin by moving sideways along the edges of an imaginary square standing in opposite corners of the dance floor again. Next, they move forward towards each other on the diagonal line of the Z, they meet and pass each other in the middle, and after having reached the center, they continue to the place where the partner started the Z-figure. These movements on the floor create two parallel Z-figures as each dancer forms the shape by moving first to one side, dancing forward along a diagonal towards the partner, passing the partner as the dancer continues to the opposite end of the dance floor, and finally stepping to the side again to end the pattern.

According to Rameau, the Z-figure usually consists of six minuet steps (across twelve bars of music) during which the partners change places (see Table 15.3). However, there were variations to this structure, as English dancing master S. J. Gardiner explained in his book A Dancing Master’s Instruction Book (1786).15 Gardiner said that the standard figure consists of nine minuet steps, but the ‘modern’ figure, as he called it, of eight.

Table 15.3: The structure of the Z-figure

|

Bar |

Movement |

|

1–4 |

|

|

5–8 |

Two minuet steps diagonally forward, partners change places, passing right shoulders, turning left (in some descriptions right) at the end. |

|

9–12 |

In the figure called the ‘right-hand’ presentation, the partners dance towards each other into the middle of the floor. They meet and then each holds the partner’s the right hand and they dance in a circle together; they then release their hands and move in opposite directions performing a small half circle away from each other before they again face each other. In the figure called the ‘left-hand’ presentation, they again dance towards one another in the center of the dance floor, take each other’s left hand, and dance one circle together before they move sideways to opposite corners of the dance floor to stand on the diagonal again. The next Z-figure is performed in the same way as described in the Table 15.3.

In the presentation of both hands, they move sideways, slowly circling towards each other, and then they hold both hands while dancing a full circle together. After the circle, they let go of one hand and turn to face the front of the room while they dance backward steps to complete the dance in their starting positions. When the dance is finished, they repeat the révérence (bows, honour) that marked the beginning of the dance.

The standardized form of six figures was developed and established by dancing masters employed at the French court, and it spread to other courts all over Europe. Only small variations occur in the different descriptions of the ordinary minuet offered in many of the European dance manuals from the eighteenth century.

Danish and Finnish Minuets

Several minuets from Denmark and Swedish-speaking Finland are known today, and, to a great extent, they follow the form and structure of le menuet ordinaire. Some variations, however, exhibit remarkable differences. The dance style among ordinary people in the Nordic countries, documented in detail since the early twentieth century, differs clearly from that of the European courts during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

It should be added, though, that according to Niels Blicher’s late-eighteenth-century description, male dancers in the Danish countryside eagerly performed gestures and movements, which referred to the dance of the upper classes.16 Later documents from Denmark do not mention this kind of behaviour in the minuet anymore.

Minuet Steps

The basic structure of the minuet steps in most Danish and Finnish variations is similar to that of pas de menuet, and the main figure in these variations also resembles the Z-figure. However, the Finnish variations follow a pattern of eight bars of music instead of twelve bars.

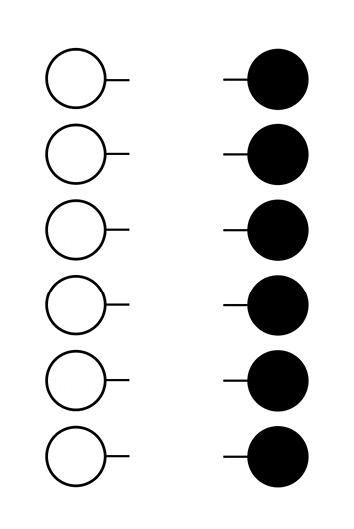

The Danish variations follow the same structure as in the ordinary minuet. The main figure consists of six minuet steps (in Danish folk-dance terminology: menuettrinn or mollevittrinn) across the music of twelve bars. The minuet is danced in longways formation (men and women in opposite lines, Fig. 15.1).

Fig. 15.1 Longways formation (black pin = male, white pin = female). © Petri Hoppu.

Four steps are first danced in place or moving a little forward and backward, after which partners change places with two steps passing partner right shoulders and turning left on the opposite side. Following the descriptions from Ærø and Støvring, the beginning of the main figure is presented in Tables 15.4 and 15.5.

Table 15.4: The beginning of the main figure, Ærø17

Table 15.5: The beginning of the main figure, Støvring

The Finnish variations’ main figure differs from the Danish and ordinary minuet since the main pattern consists merely of four steps across eight bars of music. In most Finnish variations, partners first dance two steps toward each other, following by partners changing places. Similar to the Danish variations, while changing places, partners pass right shoulders and turn left on the opposite side of the dance formation. In Finnish-Swedish folk-dance terminology, the first two steps are usually called minuet steps (in Swedish: menuettsteg), whereas the last two are called cross over steps (övergångssteg). Similar to Danish variations, the minuet is danced in longways formation as well.

Using the descriptions from Lappfjärd and Purmo, the beginning of the main figure is presented in Tables 15.6 and 15.7:

Table 15.6: The beginning of the main figure, Lappfjärd18

Table 15.7: The beginning of the main figure, Purmo19

The main figure of ordinary minuet consisted of twelve-bar structures, i.e., six minuet steps in each section. This form is found in the Danish minuets as well, whereas the Finnish minuets most often have an eight-bar structure. There are, however, also eight-bar structures in some Danish minuets, which are a part of a contra dance. The comparison of the different main figures is presented in Table 15.8.

Table 15.8: The comparison of the main figures

|

Purmo |

|||||

|

Basic step (starting upbeat) |

Pause-step-pause-step-step-step |

Drag-step-pause-step-step-step |

|||

|

steps to the left |

steps to the left and back |

steps in place or to the left and back |

steps in place |

steps in place or sideways |

|

|

5–8 |

changing places |

changing places |

|||

|

9–12 |

steps to the right |

steps in place |

steps to the left and back |

N/A |

|

What is common in all three cases is the practice of changing places with one’s partner. Otherwise, there are different ways of dancing the minuet steps towards the partner. The ordinary minuet involves practically constant movement, whereas both Danish and Finnish minuets include steps taken in place.

Moreover, in Danish minuets, dancers also move either directly or diagonally to the left and returning back the same route. In some Finnish minuets, especially in the Nykarleby region, they move clearly to the right and left before changing places. However, the Finnish type uses movements that are considerably shorter than those in the ordinary minuet or in Danish ones, lasting only one minuet step or fewer in each direction. Minuets from the Nykarleby region differ from other documented Finnish minuets mostly due to their somewhat vague structure: the beginning of each step is not always easy to determine, and the directions of the steps as well as turning the upper body are considerably different from those in other Finnish minuets.20 As we have discussed previously, some of these unique features of Nykarleby region minuets can be found in Danish minuets as well.

Minuet dancers in Swedish Ostrobothnia, when interviewed by Petri Hoppu, revealed that they do not use the concept of a ‘minuet step’. They emphasized the relation between music and dance when asked how they knew how to dance correctly. According to Hoppu, the minuets in Nykarleby region and probably more commonly in a rural context have not been experienced as consisting of separate steps. The basis for dancing is, rather, the reiteration of the basic movement sequence of the minuet with four steps and two ‘breaks’ in a specific order and with specific relation to music.21 Since the steps have not been seen as autonomous units, the dance has been flexible, making the multiple structure variations possible.

The Basic Form

The basic form of le menuet ordinaire can be found in most Danish and Finnish minuets, although its different parts are presented differently. They do not contain the reverence towards the spectators at the beginning and in the end, but otherwise, the resemblance is evident. The basic forms of the four Danish and Finnish-Swedish examples are presented in Tables 15.9–15.12.

Table 15.9: The basic form, Ærø22

Table 15.10: The basic form, Støvring

Table 15.11: The basic form, Lappfjärd23

Table 15.12: The basic form, Purmo24

The beginning of the Danish and Finnish minuets takes place either in one line, with couples hand in hand and facing the same direction, or in two lines, with partners facing each other. The first type is found in the variations from Ærø and Lappfjärd, where the gentleman leads the lady to the opposite side before the main figure starts. In Ærø, there is a reverence towards the partner before this. The Støvring variation starts with one couple turning counterclockwise hand in hand before the main figure. The variation from Purmo does not include any specific introduction, but the dance begins immediately with the main figure.

The main figure similarly takes place in all examples, including the ordinary minuet. It contains minuet steps in place, minuet steps sideways or forward and back, and minuet steps in which partners change places with the partners. Typically, the partners pass each other on the left, and they often turn toward each other while passing. The figure can be repeated as long as the gentleman (in the ordinary minuet) or the leading gentleman/all gentlemen (in other examples) wish.

Before the next part, couples begin by turning, hand in hand; then the gentleman or gentlemen make a gesture raising one hand (ordinary minuet) or give a signal such as clapping, stamping, or rotating their hands (other examples). In the Danish variation from Støvring, gentlemen first rotate their fists and, immediately before taking their partner’s hand, clap. The most complicated signals take place in several Finnish variations from the Nykarleby region where they typically consist of one signal stamp by the leading gentleman, followed by a series of several stamps by all the gentlemen; this is repeated followed by three more handclaps by all the gentlemen before they each extend a hand to their partner.25

The hand figure in the middle of the dance is found in all the examples. In the ordinary minuet the partners first hold right hands and make a circle and then immediately hold left hands and make a circle the other direction. The Danish minuet variations have the same feature of turning when holding first the right and then the left hands. In most Finnish variations, one can find several examples where the partners turn only when they are holding their right hands, although the examples from Lappfjärd and Purmo do contain instances of turning while holding both the right and left hands. The variation from Lappfjärd is closest to the ordinary minuet in that turns while holding right and left hands are completed immediately one after the other, whereas in other examples, several minuet steps are danced between the turns.

After the main figure, which is repeated similarly as at the beginning, the finale of the minuet is danced. In the ordinary minuet, this is done first with partners joining both hands and turning clockwise around, after which they return to their starting positions. Also, in both Danish examples, the partners turn while holding both hands. In contrast, in all known Finnish variations of the minuet, partners either hold one hand and turn clockwise or just finish the dance facing each other, with or without holding hand in hand. In Danish and Finnish minuets, the dancers stand in a longways formation facing each other at the end of the dance, rather than side by side as in the ordinary minuet.

Concluding Remarks

In sum, it can be said that the overall structure of the ordinary minuet is found in most Danish and Finnish vernacular minuet variations. The three basic elements analysed here—the minuet step, main figure, and basic form of the dance—have remained recognizably similar over the centuries, although their details may vary. This shows that these three basic elements are the most fundamental elements of the ordinary minuet from the dancers’ perspective. The reiteration of their structured combination creates the embodied experience of the dance.

Of course, there is more to the minuet than these elements. When it comes to style or dance technique, the differences between the ordinary minuet and its Danish and Finnish counterparts become significant. Ordinary people who do not learn the minuet in dance schools may omit the sophisticated steps or lack graceful arms. Some features of the minuet may have fallen out of use in the rural tradition over the centuries, as they have not been preserved in a literary form. Nevertheless, the basic elements are learned through imitation and embodied experiences while observing others or participating in dances.

References

Bakka, Egil, Mæland, Siri, and Svarstad, Elizabeth, ‘Vertikalitet og den franske 1700-talls menuetten’, Folkdansforskning i Norden, 36 (2012), 38–46

Blicher, Niels, Topographie over Vium Præstekald ([1795]; Copenhagen: Søren Vasegaard, 1924)

Gamle Danse fra Fyn og Øerne (Copenhagen: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1949)

Heikel, Yngvar, VI Folkdans B Dansbeskrivningar. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 268 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1938)

Hoppu, Petri, Symbolien ja sanattomuuden tanssi: Menuetti Suomessa 1700-luvulta nykyaikaan (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1999)

Inglehearn, Madeleine, Minuet in the Late Eighteenth Century: Including a Reprint of S. J.Gardiner’s ‘A Dancing Master’s Instruction Book’ of 1786 (London: Madeleine Inglehearn, 1998)

Norlind, Tobias, Dansens historia med särskild hänsyn till dansen i Sverige (Stockholm: Nordisk Rotogravyr, 1941)

Rameau, Pierre, Le maître à danser (Paris: Rollin Fils, 1748)

Sutton, Julia, ‘The Minuet: An Elegant Phoenix’, Dance Chronicle, 8 (1985), 119–52

Taubert, Gottfried, Rechtschaffener Tanzmeister oder Gründliche Erklärung der Französischen Tanz-Kunst (Leipzig: Friedrich Lanckischens Erben, 1717)

Taubert, Karl-Heinz, Höfische Tänze (Mainz: Pan, 1968)

―, Das Menuett (Zürich: Pan, 1988)

Tomlinson, Kellom, The Art of Dancing: Explained by Reading and Figures; Whereby the Manner of Performing the Steps is Made Easy by a New and Familiar Method (London: the Author, 1735)

Tunley, David, Couperin (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1982)

Wood, Melusine, More Historical Dances (London: The Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing, 1956)

1 Melusine Wood, More Historical Dances (London: The Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing, 1956), p. 84.

2 Ibid., pp. 90–91.

3 Julia Sutton, ‘The Minuet: An Elegant Phoenix’, Dance Chronicle, 8 (1985), 119–52 (p. 136).

4 David Tunley, Couperin (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1982), p. 102.

5 Karl-Heinz Taubert, Das Menuett (Zürich: Pan, 1988), p. 20.

6 Sutton, pp. 138–40.

7 Tobias Norlind, Dansens historia med särskild hänsyn till dansen i Sverige (Stockholm: Nordisk Rotogravyr, 1941), pp. 59–60.

8 Karl-Heinz Taubert, Höfische Tänze (Mainz: Pan, 1968), p. 165.

9 Gottfried Taubert, Rechtschaffener Tanzmeister oder Gründliche Erklärung der Französischen Tanz-Kunst (Leipzig: Friedrich Lanckischens Erben, 1717), pp. 618–621; Taubert, Das Menuett, pp. 88–93.

10 Rameau, Le maître à danser (Paris: Rollin Fils, 1748), pp. 67–70.

11 For an analysis of the vertical movements in the minuet step, see Egil Bakka, Siri Mæland, and Elizabeth Svarstad,‘Vertikalitet og den franske 1700-talls menuetten’, Folkdansforskning i Norden 36 (2012), 38–46. See also Chapter 16 in this volume.

12 Taubert, Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister, p. 618.

13 Taubert, Das Menuett, p. 89.

14 Kellom Tomlinson, The Art of Dancing: Explained by Reading and Figures; Whereby the Manner of Performing the Steps is Made Easy by a New and Familiar Method (London: the Author, 1735); Taubert, Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister; Carl Josef von Feldtenstein, Erweiterung der Kunst nach der Chorographie zu Tanzen, Tänze zu Erfinden, und Aufzusetzen, wie auch Anweisung zu Verschiedenen National-Tänzen als zu Englischen, Deutschen, Schwäbischen, Pohlnischen, Hannak- Masur- Kosak- und Hungarischen mit Kupfern nebst einer Anzahl Englischer Tänze (Braunschweig: Carl Josef von Feldtenstein, 1772).

15 Madeleine Inglehearn, Minuet in the Late Eighteenth Century: Including a Reprint of S. J. Gardiner’s ‘A Dancing Master’s Instruction Book’ of 1786 (London: Madeleine Inglehearn, 1998), p. 15.

16 Niels Blicher, Topographie over Vium Præstekald (Copenhagen: Søren Vasegaard, 1924).

17 Gamle Danse fra Fyn og Øerne (Copenhagen: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1949), pp. 68–71.

18 Yngvar Heikel, VI Folkdans B Dansbeskrivningar. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 268 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1938), pp. 16–18.

19 Ibid., pp 34–35.

20 Petri Hoppu, Symbolien ja sanattomuuden tanssi: Menuetti Suomessa 1700-luvulta nykyaikaan (Helsinki: SKS, 1999), pp. 331–41.

21 Ibid., pp. 411–15.

22 Gamle Danse fra Fyn og Øerne (Copenhagen: Foreningen til Folkedansens Fremme, 1949), pp. 68–71.

23 Heikel, pp. 16–18.

24 Ibid., pp. 34–36.

25 Hoppu, p. 359.