16. New Perspectives on the

Minuet Step

©2024 E. Bakka, E. Svarstad & S. Mæland, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.16

This chapter discusses how the knowledge about the Nordic folk minuet, made available in this book, may give a broader basis for interpreting the historical sources regarding the basic French eighteenth-century minuet step. The Nordic minuet forms have been in continual use since the seventeenth century and are still used as folk dance and on the stage.1 There is a striking structural resemblance between these forms and the minuet as a court dance. The knowledge of how the minuet is being danced in Nordic tradition, found in the Nordic Folk Minuet as well as at Danish Royal Ballet, will cast new light on the minuet step described in earlier centuries.

Main Sources for Reconstructing Le Menuet Ordinaire

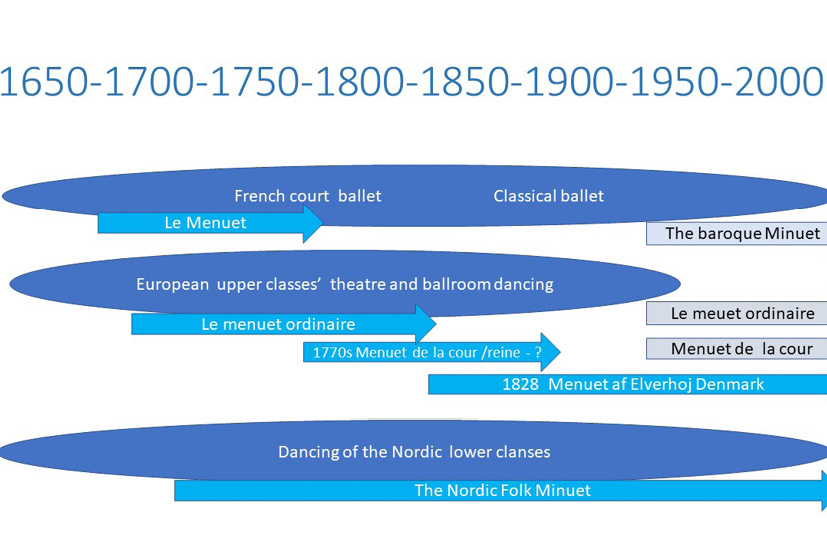

Earlier parts of this book have already scrutinised the sources available for the reconstruction of le menuet ordinaire: The descriptions by the dancing masters are practically the only ones used in historical dance circles. From the Nordic research environment we now bring in a large material of film recordings with traditional dancers who have their dance in direct unbroken line of transmission since the seventeenth century. There are still a large number of folk dancers transmitting the knowledge from these people. In addition there is an unbroken historical connection sustained by the Royal Ballet in Copenhagen via the theatrical work Elverhøj (see Chapter 10).

Fig. 16.1 Schematic illustration by Egil Bakka of the context where forms of the minuet were transmitted (dark blue), duration of the minuet forms (light blue) and reconstructions (grey).

In addition, we will thoroughly describe how a tool developed in Norway, the ‘svikt analysis’, may be helpful in the comparison and interpretation of the verticality in the minuet step of past and present.2 The tool departs from a study of the locomotion mechanics and therefore speaks to the function of the mouvement and the distribution of pliés (bending) and elevés (rising) in eighteenth century dance descriptions. Based on physics and anatomy, the svikt analysis is, in its basic principle, not culturally constructed. It therefore has the potential to be applied to any type of human locomotion, including that which is described in historical sources.

The historical material we will use for our experiment is:

- The description of Minuet in Pierre Rameau’s Dancing Master (1748)

- Feuillet notation of the minuet step for le menuet ordinaire

- Feuillet notation from Kellom Tomlinson in 1735

- William Hogarth’s informal description of the vertical movements in the minuet from 17723

Keeping the svikt patterns of the folk minuet in mind, we identify the vertical movements in all four versions above with svikt analysis. The svikt is comparable to the signs for pliés (bending/sinking) and elevés (rising) in Feuillet notation: ‘Sinkings are the Bendings of the knees. Risings are when we rise from a Sink or erect our selves’.4 Taken together, a plié and an elevé is called a movement. 5 A movement corresponds clearly to the Norwegian concept of a svikt.

From our experience as researchers and as dance practitioners and teachers, we know that dance descriptions and notations do not include all aspects of the movement pattern they try to convey. This contention is based on our practical experience and knowledge, which also contributes to the analysis. By adding new interpretations of old sources we juxtapose more understandings of the past, presenting them as a multitude of possibilities.6

The Project History

The idea of using folk versions and principles of biomechanical locomotion to aid the interpretation of historical minuet descriptions originated with Egil Bakka.7 He felt that baroque and historical dance in general seemed strained and lacked the flow that is considered an asset in most other types of dance. By reconstructing dances from other kinds of dance descriptions, Bakka learned that it was necessary to compare textual accounts of dances with ordinary practices as it seemed hardly possible to translate words and symbols into meaningful movements without being able to refer them to a related dance practice. He presented some of these ideas at a workshop of Nordic and French dance historians in Paris in June 2008, which was also a point of departure for this book. Some of the subsequent development of these ideas has been a sub-project of this book.

To test his ideas, Bakka invited Elizabeth Svarstad, a dancer trained in ballet, baroque dance, and Feuillet notation, to form a joint project. Bakka’s research assistant at that time, Siri Mæland, also participated at oral presentations to assist in the introduction of svikt analysis. Svarstad and Mæland started an experiment that involved each performing a version of the minuet step—first, from the perspective of a ballet dancer, then from the perspective of a folk dancer. The subproject has been presented several times, mostly in the framework of the book project.8 Its ideas, thus, have been discussed, questioned, and commented on by researchers and expert practitioners from many parts of the field of dance. Some of these scholars have embraced the project ideas; others have been provoked or sceptical. The discussions, comments, and feedback have been important for the development of the theory and an article.9

While engaging feedback from dance experts, the Bakka, Svarstad, and Mæland worked in tandem to develop the practice. At one point after performing the minuet regularly, Svarstad was asked by a musician with whom she had worked closely for many years whether something had changed in the way she danced the steps. This musician is not only educated in baroque music, but also plays for folk dances, and dances herself. Her observation was very interesting, suggesting a visible bodily development in Svarstad’s execution of the minuet step. Although Svarstad has studied baroque dance for many years, her involvement in the svikt analysis changed the way she performs the bendings and stretchings of the minuet.

Historical Dance—Baroque Dance

Much current interest in the minuet is rooted in the historical-dance or baroque-dance movement, which started in the 1950s when pioneers reconstructed dances from the eighteenth-century European courts. Melusine Wood in England, Wendy Hilton in the US, Francine Lancelot in France, and Karl-Heinz Taubert in Germany were among the leading pioneers, dancers, and educators who contributed to the work in the beginning.10 They and others collected, analysed, interpreted, and reconstructed dances from historical sources, producing books, manuals, and videos, starting clubs, networks, and workshops, and also creating professional companies and dance performances. Although these researchers sought to create as precise and truthful a picture as possible of the dances they reconstructed, the new field of dance studies succeeded in compiling only what dance scholar Mark Franko described in 1989, perhaps a bit too harshly, as ‘shadowy and insubstantial renditions of a period’s choreography’ that were ‘characterized by a condescending attitude to audience and performer alike’.11 Strong convictions from different personalities about which interpretations are right or wrong were transmitted and reinforced by reiteration. The risk in such cases is that successors and students will look at the well-established reconstructions as ‘historical truths’ and tend not to distinguish precisely and consistently between

- The actual dancing that happened in the eighteenth century and the nineteenth- and twentieth-century sources produced directly from experience of this dancing

- Later interpretations of eighteenth-century sources coupled with the actual dancing resulting from such interpretations (historical or baroque dance/dancing)

It is essential to make these distinctions because conflating the two phenomena contributes to authorising interpretations as ‘historical truths’ rather than treating them as more- or less-supported proposals about how dances of the past can be understood and danced.

The historical or baroque dance represents all that one has been able to reconstruct using sources originating from the European court societies and aristocracy. Therefore, the material covered by the term ‘baroque minuet’ may also refer back to specific choreographies and the general social dance material. The menuet ordinaire, which is the object for the comparative analysis in this chapter, was, without doubt, the most frequently used in the eighteenth century. It is, however, only one of the many dances named ‘minuet’ that was danced at that time and later taken up by baroque dancers. Many dancing masters described it, and indeed, several of them used many pages for their explanations. Some of the dancing masters have described the dance in words, such as Gottfried Taubert in 1717, Pierre Rameau in 1725, Kellom Tomlinson in 1735.12 In addition, Rameau demonstrated the figures of the minuet by arranging the words on the page in the shape of each figure’s performance both spatially on the dance floor in relation to the partner. Tomlinson included a minuet written in Feuillet notation.

Limitations of Dance Notation and Description

Despite all of this, dance descriptions and notations will rarely include all aspects of the movement pattern they try to convey.13 What they contain depends on when and where they were written and also on the competence of the writer. Aspects that may seem evident in the environment or irrelevant for the target audience sometimes are omitted. Some aspects are beyond the understanding of the time or beyond the notator’s ability to describe, and, therefore, the writer may exclude, simplify, or misrepresent them. In addition, even if descriptions do not simplify and reduce some aspects of a practice by relying on some prior knowledge, they can easily become incomprehensible because of their complexity. This is not so problematic if the reader knows similar dances, can see them performed, or is learning them (in-person) from the notator. The notation then acts as a memory aid or can advance understanding of the movements. Thus, no dance notation and no interpretation of a dance stands totally on its own; basic presumptions are built in on both sides. We, as readers of historical documents, therefore, need to have an awareness about the writers’ presumptions, including not only the ideal but also the ordinary way dancers carry their bodies. If folk dancers are asked to dance a ballet choreography or ballet dancers are asked to dance a traditional dance from the village, the resulting dances will differ from the usual styles practiced. Changes in the character of each dance will be evident because the ‘movement habitus’14 of one group is so different from that of the other. Good descriptions or notations can reflect some of these differences; none will be able to capture all of them.

First, we need to think about the presumptions and the ‘movement habitus’ of the dancing masters at the French court in the late seventeenth and the early eighteenth centuries. At this point, classical ballet was still in its early stages. The technique and movement conventions changed considerably in the following two hundred years, up to 1950. However, the starting reference point (or ‘movement habitus’) for pioneering researchers and interpreters of historical dance was the mid-twentieth-century version of classical ballet.

Having pointed out some of the challenges in working with written sources of information about dances from the past, we will apply our new interpretation to the first lot of our source material—namely, versions of the minuet step recorded in Feuillet notation.

Feuillet Notation

Feuillet notation was developed in the seventeenth century by Pierre Beauchamps, who was a dancing master at the court of Louis XIV. Beauchamps developed a system of signs and symbols for writing choreographies created for the ballroom, or for the theatre. Later, his student Raoul-Auger Feuillet published the system in the book Chorégraphie, ou l’art de décrire la dance (1700). The system was used in a vast number of collections of dances in the first half of the eighteenth century. The term ‘Beauchamps-Feuillet notation’ occurs, but this method is most often referred to, merely, as ‘Feuillet notation’.15

Feuillet notation provides information about the dancers’ steps, the relationship between the dance and the music, the floor patterns traced by dancers’ movements, and the relationship between the dancers. The notation seemingly presents the dancers’ actions in detail.

The Feuillet notation system was designed not to preserve but to distribute choreographies. Members of the court were expected to learn a certain number of new dances each year while maintaining some of the dances from previous years. This gave a repertoire of dances to perform at balls. Having learned how to read the dance notation system, members of the court could study the choreographies themselves, and courts in other countries could learn new dances without depending fully on a dancing master. In the early eighteenth century, most choreographies for the court were short-lived pieces, and new dances were created frequently. Such dances differ from the regular minuet in that they were composed of different steps and combinations of steps for each bar. The regular minuet, on the other hand, consisted mainly of the basic minuet step, six fixed figures, and a certain degree of improvisation was possible within the figures.

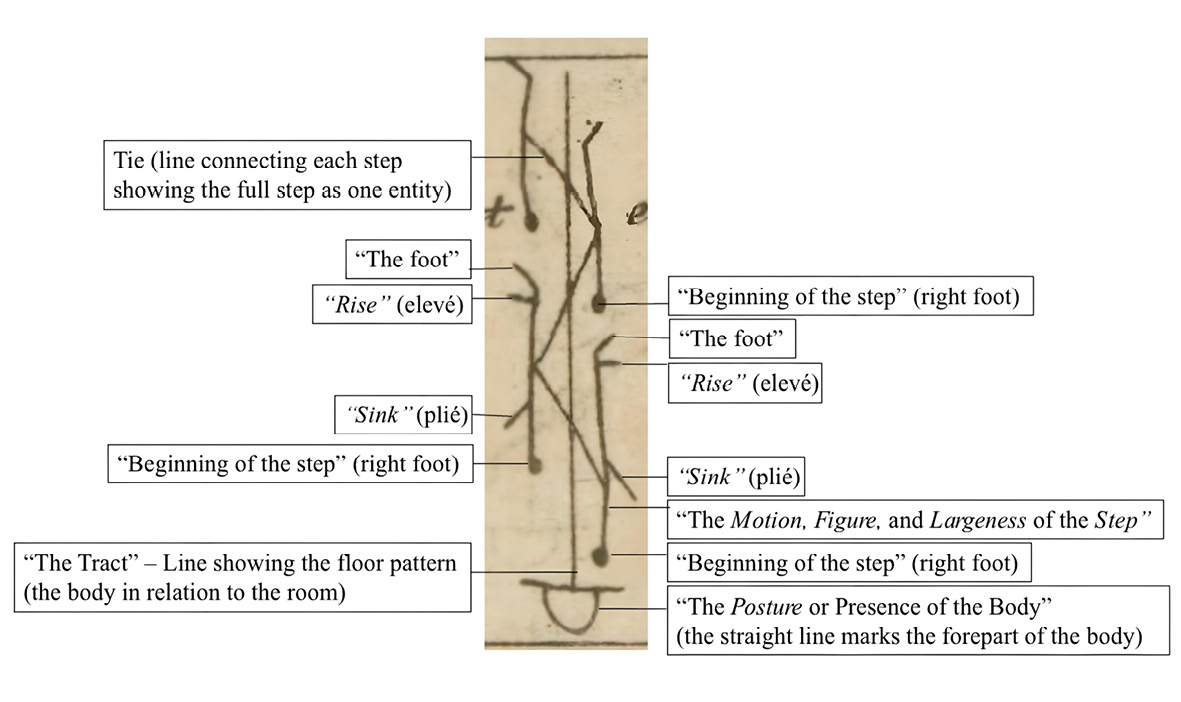

A minuet step written in Feuillet notation shows

- the body of the dancer,

- the tract, or floor pattern,

- the beginning of the step marked by a black spot,

- the movement of the feet,

- the bending marked by a small slash [/],

- the stretching or extension of the knee marked by a short horizontal stroke [–],

- the placement of the foot marked by a small side stroke representing the foot from the heel to the toe and turned outwards. The relationship with the music is shown by marking the bar line as small horizontal lines on the floor pattern line.

- thin lines binding together the different steps in a step unit. These tracts, or liaison lines, make it easier and quicker to recognise entire step units, for example, the minuet step, which consists of four placements of the feet on the floor shown as one entity.

Fig. 16.2 The minuet step in Feuillet notation from Feuillet, Chorégraphie (1701),

p. 90. Explanations of what each of the signs represent. Quotes from Feuillet (trans. Weaver), Orchesography (1706), public domain.

The graphics-based notation system shows explicitly how the steps are composed, but the actions underlying the notation are only implied. The people who performed these dances in the eighteenth century knew how to execute the steps because they took classes with a dancing master. This bodily knowledge is, of course, lost, and attempts to translate words and symbols into action are rife with challenges.

Today, the movements we make based on reading and interpreting the sources will never be corrected or supervised by the dancing master, thus we must accept that we will never know if we are even close to executing the steps in the same way as in the eighteenth century. Hence, in order to reconstruct the movements of the feet, legs and body, we maintain that looking to a bodily transmitted dance tradition over time, such as the Nordic folk minuet, may bring us closer to the bodily and organic expression of eighteenth-century dancers.

In this attempt to apply the svikt analysis to the minuet step written in Feuillet notation, as we will show later in the chapter, we concentrate on the ordinary minuet step danced forwards. Eighteenth-century sources indicate that there are several ways to perform a minuet step. The menuet ordinaire is described in many sources, and as we read Rameau, Tomlinson, and Taubert, we find the step described with bendings on count six and count two.16

Explaining the different kinds of minuet steps, Rameau began describing what he called the true pas de menuet. It contains four steps and three movements (bending and stretchings) and has a demi-coupé echappé, which is a small leap, at the end of the step. He continued, however, to state that since this step requires a very strong instep; it does not suit everyone and is not used very much. He then proceeded to explain a simplified version of this step consisting of only two mouvements (bending and stretchings):

It begins with two demi-coupés, the first being made with the right foot, the second with the left, followed by two pas marchés sur la demi-pointe, the first with the right foot, the second with the left […] in making this last pas the heel must be lowered to the ground, to enable the knee to be bent in preparation for another pas.17

Rameau described the manner of performing this step in a more detailed way where the vertical movements are more explicit:

Having then the left foot in front, let it support the weight of the body, and bring the right foot close to the left in the first position. Bend the left knee [6] without letting the right foot touch the ground. When the left knee is sufficiently bent, move the right foot to the fourth position front, at the same time rising sur la demi-pointe, straightening both knees [1] and bringing both legs together as shown in the fourth part of the demi-coupé (Fig. 26), called the equilibrium or balance. Then lower the right heel to the ground to keep the body steady and at the same time bend the right knee [2], without allowing the left foot to touch the ground, and move the latter to the fourth position front and rise on the left demi-pointe, straightening both knees [3] and bringing both legs together in balance. Then execute two pas marchés sur la demi-pointe, the first with the right foot [4], the second with the left [5], lowering the left heel to the ground after the second, in order to have the body firmly placed ready to begin another pas de menuet.18

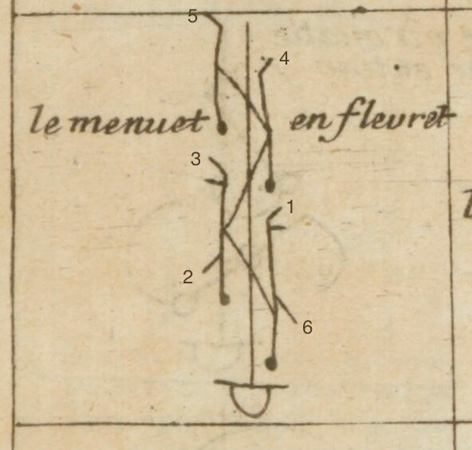

The bold face sections and numbers in brackets that Rameau included in this quotation indicate the vertical movements of the minuet step. In the figure below these parts are connected to the signs for those actions in the Feuillet notated minuet step. The numbers refer both to the vertical movements and the beats in the music.

Fig. 16.3 The minuet step as shown in Feuillet, Chorégraphie (1701), p. 90 (numbers added by the authors), public domain.

6: ‘Bend the left knee’

1: ‘straightening both knees’

2: ‘bend the right knee’

3: ‘straightening both knees’

4: ‘the right foot’

5: ‘the left’

Although the dancing masters’ descriptions of the minuet step is quite comprehensive, they lack accurate information about certain details concerning accents, rhythm, timing. More critical to our argument, the Feuillet notation system does not contain detailed information about the level and duration of plié and elevé (bending and stretching of the knees). Certainly, the notation shows bendings and stretchings of the knee and when the dancer should be on demi-point. But it is not capable of capturing details such as how much bending and stretching the dancer should use while performing various steps and positions, nor does it capture the duration or the quality of the movements. Rameau simply stressed the importance of showing a clear difference between the bending and stretching:

in regard to the bends these should always be well marked, especially when learning them, because they make a dance more pleasing; whereas, if they be not marked, the steps can hardly be distinguished and the dance appears lifeless and dull.19

The performance of bending and stretching the knee and the rising on demi-point and lowering of the heel is therefore very much left to interpretation and will be dependent on factors such as the dancer’s understanding of the notation, technique, and style, as well as the dancer’s bodily experience, training, and so on.

In baroque-dance technique, when dance is reconstructed from such descriptions, the interpretation has the potential to become literal, leading to a stiff dance posture. The minuet step is often seen performed with very straight knees. Yet, that is Rameau’s explicit prescription if we were to understand it literally, and it may seem challenging to question it and suggest an alternative reading.

Svikt as an Analytical Tool

Our suggestion for an alternative approach and interpretation of the eighteenth-century description of the minuet step is to take scientific studies of human locomotion into consideration. Studies of regular walking (‘gait-studies’) in adult humans show a vertical movement cycle for the hips.

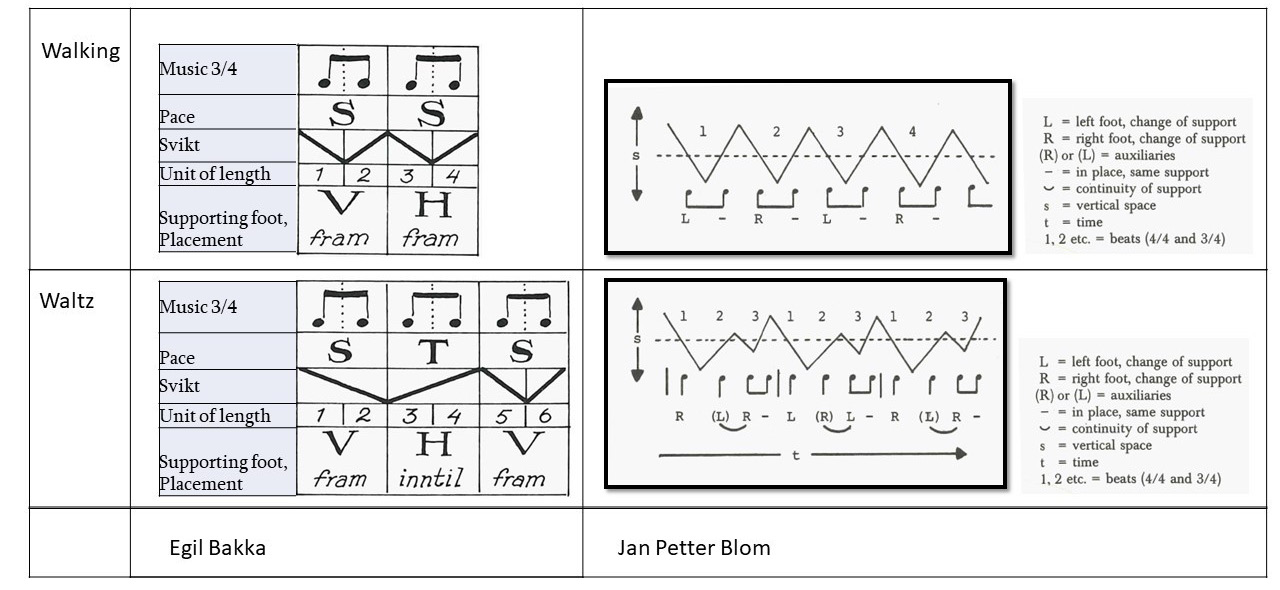

All scientific studies of locomotion show vertical movement patterns created by the manipulation of body weight. The Norwegian social anthropologist and folk music and folk-dance researcher Jan Petter Blom studied stylistic differences in the Norwegian bygdedans (regional dance) in the 1960s.20 He found that the dancers’ footwork is comprised of ‘sequences of alternate stretching and bending movements of the legs achieved by rotational movements round three axis: the hip, knee and ankle’ while the vertical movements of the centre of weight, the dance meter were a central rhythmic marker in different regional dances.21 He proposed ways of notating this type of footwork (see Figure. 16.4). On the basis of Blom’s work, Bakka developed a more descriptive analysis system of a different step type, the svikt analysis system.22 A svikt is an analytical term for the rise and fall of the centre of gravity while dancing. A svikt pattern is the wave one might draw by watching this rise and fall.23 The svikt analysis system was developed to support textual-based dance descriptions and to be used by the folk-dance movement in Norway and was based upon observation rather than measurements.24 In their analysis Blom and Bakka break up the vertical waves into a movement down: a bending (\) and a movement up: a stretching (/). A bend and a stretch becomes a total svikt (\ /). One of the differences between them when it comes to notation is that Bakka describes the svikt pattern but not the amplitude (the size of the curve’s elements), while in Blom’s notation he also prescribes the amplitude, or at least a generic amplitude.

Fig. 16.4 Notation of the vertical movements of the centre of gravity (shown graphically as straight lines) in waltzing and walking illustrated by Blom and Bakka. Bakka’s figures show one bar of music as this corresponds to the dance step. Blom’s figures show the regularity of the dance meter, using ‘vals’ to show three bars of triple meter in music and dance. For English readers: V = Venstre fot [left foot], while H = Høyre fot [right foot]. Fram is the Norwegian word for ‘forward’, while inntil is the Norwegian word for ‘close’ or ‘in place’25

As shown in the gait studies above, the body’s vertical movements—the lowering and lifting—are necessary for locomotion. Each shift of weight from one foot to the other will include some vertical movement. With the understanding that the svikt is a precondition for locomotion and is, thus, continuously present through a dance process, comes the wish to monitor and represent this aspect continuously. This is a deviation from the Feuillet system in which the vertical movements are notated only where it is enlarged in the dancing for decorative purposes.

The Vertical Pattern in the Minuet Step

In what follows, we will discuss how the minuet step written in Feuillet notation could be interpreted through the perspective of the svikt analysis. The Nordic folk minuet has a svikt (bending and stretching) consistently on each beat of the music:

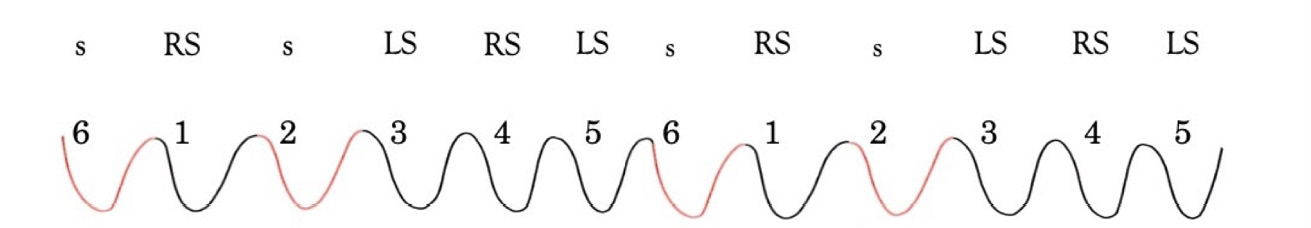

Fig. 16.5 Svikt analysis of two forward minuet steps performed from left to right. The numbers mark the beats of the music, the letters mark the svikts (bendings and stretchings), and the red parts of the curve shows the bendings highlighted in eighteenth-century dance descriptions and Feuillet notation of the minuet step. Design by Egil Bakka and Elizabeth Svarstad.

Because the structure of the eighteenth-century minuet has remained more or less unchanged in the Nordic folk minuet, it seems reasonable to assume that the vertical pattern would be similar in both of these versions. There is some variation within the ‘eighteenth-century’ and ‘folk’ instances, but there is clear consistency in the overall shared structure. Based on this hypothesis, our question is whether a minuet step with six svikts, as we know it from the Nordic folk versions of the minuet, can be reconciled with the descriptions found in eighteenth-century sources.

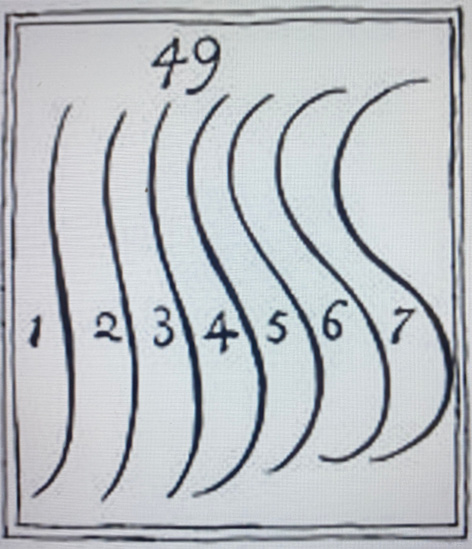

The English painter William Hogarth (1697–1764) has written a surprisingly explicit description of the minuet in his book The Analysis of Beauty (1772) that concentrates on the vertical movements and their aesthetic value:

The ordinary undulating motion of the body in common walking (as may be plainly seen by the waving line, which the shadow a man’s head makes against a wall as he is walking between it and the afternoon sun) is augmented in dancing into a larger quantity of waving by means of the minuet-step, which is so contrived as to raise the body by gentle degrees somewhat higher than ordinary, and sink it again in the same manner lower in the going on of the dance. The figure of the minuet-path on the floor [Fig. 16.6, number 122] is also composed of serpentine lines [Fig. 16.7, number 49] varying a little with the fashion: when the parties by means of this step rise and fall most smoothly in time, and free from sudden starting and dropping, they come nearest to Shakespear’s [sic] idea of the beauty of dancing, in the following lines,

– What you do,

Still betters what is done, –

– When you do dance, I wish you

A wave o’th’ sea, that you might ever do

Nothing but that; move still, still so,

And own no other function.26

Fig. 16.6 William Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty, plate 2 (1753), etching.

The figure of the minuet path on the floor in drawing number 122 in upper

left corner. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Analysis_of_Beauty_Plate_2_by_William_Hogarth.jpg, public domain.

Fig. 16.7 Serpentine lines from William Hogarth’s The Analysis of Beauty, plate 1 (1753), etching. In the scale of them, number 4 is called by Hogarth ‘The Line of Beauty’. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Serpentine_lines_from_William_Hogarth%27s_The_Analysis_of_Beauty.jpg, public domain.

Hogarth’s description of how to detect the ‘waving’ motion in the dancing corresponds strikingly with the principles of the svikt analysis. The focus on movement offers a method for interpreting the sources in our own bodies.

The waving motion is not so apparent when reading Rameau’s description of the minuet step, nor when looking at the Feuillet notation of it separately. However, Hogarth’s observation of how the head moves indicates the vertical movements of the body while dancing and substantiate our idea of using analysis of the svikts to link notation with the traces of the eighteenth-century minuet that survive in the Nordic folk minuets.

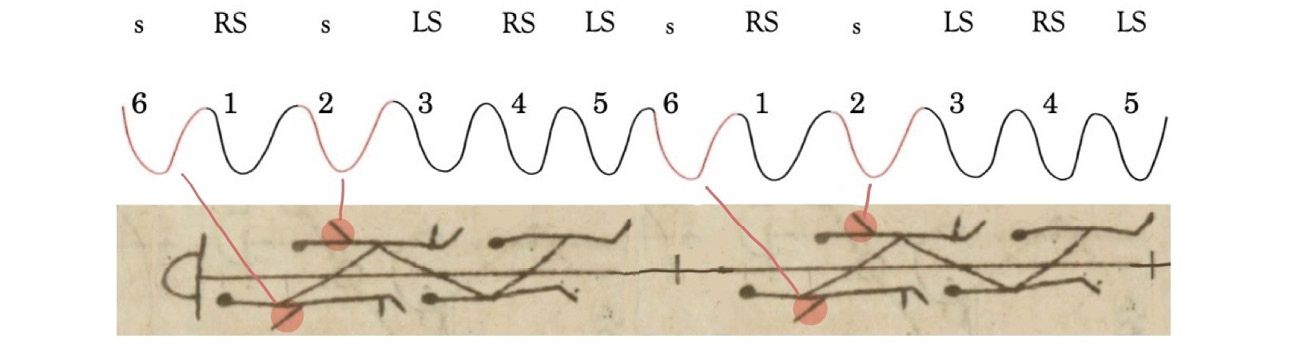

In the illustration below we have combined the notation of the minuet step written in Feuillet notation with the svikt curve of the danced minuet step (marking the waving undulation motion as the dancer performs the step).

Fig. 16.8 Svikt analysis and Feuillet notation of two forward minuet steps.

Red markings show the highlighted svikts. Svikt curve by Egil Bakka and Elizabeth Svarstad. Notation images from Feuillet, R.-A., Chorégraphie (Paris, 1700),

public domain.

The graph shows two minuet steps forward, read from left to right. The svikt curve is constructed according to Bakka’s analysis of the Nordic folk minuet, and it plots all the svikts regardless of their degree or size. The two double svikts (on counts 2 (RSs) and 6 (LSs)) are highlighted.27 The Feuillet notation underneath the svikt curve corresponds to the action of the feet in the same two forward minuet steps. The notation provides information about the direction for the dance steps and how the feet should be placed on the floor—four foot-transfers in each step. The short slashes in red circles for each of the first two movement symbols indicate the bending and the associated stretching, or plié and elevé. The red lines point to the corresponding foot transfers in the svikt curve above each. We note that the svikt curve shows a svikt for all six counts in the minuet step, while the Feuillet notation does not cover the bending and stretchings naturally inherent in foot transfers or when walking.

As we showed when discussing the gait studies earlier, locomotion mechanics require that the body must be lifted and lowered for the transfer of weight. From this point of departure, there needs to be more than the two down-up movements shown in Feuillet notation and Rameau’s descriptions, but not necessarily as many as the six that we find in the Nordic folk minuets. A likely explanation for why some of the technically required downs and ups have been omitted from the notation is that the dancing masters and notators only wanted to stress the largest downs and ups which served a decorative function. Notators might not have thought it necessary to mark the downs and ups of what may have been more or less normal walking. We know from folk-dance descriptions that notators tended to describe the unusual or the deviations from the ordinary.

Hogarth’s description mentioned a larger quantity of waves than in walking and that ‘this step rise and fall most smoothly in time’, which seems to suggest a continuity of waves—not four as in the four paces but six as a regular pulse aligned with the six beats of the music

For this reason, we argue that the Feuillet notation marks the steps with plié and elevé at the beginning that take two beats each, because these stand out as more extensive than the remaining steps that were closer to ordinary walking steps. We argue also that the dancing masters tended to describe the extraordinary rather than the ordinary. This interpretation leads us towards the svikt pattern of the Nordic folk minuet, even if svikts are not danced with any apparent difference in amplitude there.

Thus, if we compare the vertical patterns in the Feuillet notation with Blom’s notation, it may have been important for Feuillet to indicate which steps had larger amplitude (plié and elevé) than others. But how does one measure or signify gradations of this kind of amplitude? How deep is deep? A bit deeper than normal, as deep as the dancer can manage, or just a clearly emphasised bending? It is also worth noticing that sources tell us that the minuet has been danced with an apparent elevation, above the ground. Correspondingly, in some versions of the Nordic folk minuet dancers were jumping. This practice confirms that large down-and-up movements were not alien to the dance, and, as Hogarth wrote, referring to elevation, they were a bit larger than seen in walking.

If we look at the folk minuet’s structural elements, there is a striking resemblance to the minuet as a court dance. Similarly, we can make comparisons with other dances found in older sources and in folk dance. One example may be the waltz that came to the Nordic region mostly via dance teachers. The structural similarity between what the older sources tell and what is practised in traditional folk and social dance settings is striking.

A final and essential point to make about Hogarth is his insistence upon smoothness, that dance should be ‘free from sudden starting and dropping’. When a dancer intends to raise sharply onto the toes or sink precisely down on the heels, the result is just such a sudden starting and dropping. Many dancing masters too, among them Rameau, stressed that dancing and social behaviour should be natural:

I hope that in guarding against defects no one will be so stupid as to appear stiff or awkward, which faults are as bad as affectation; good breeding demands that pleasing and easy manner which can only be gained by dancing.28

What it means to be beautifully natural, unaffected and not stiff will, of course, depend upon the conventions and aesthetics of the specific time and environment. Nonetheless, it is difficult to reconcile the rigid movements of many historical dancers with Rameau’s and Hogarth’s ideals.

Advanced folk dancers may possess more of the qualities desirable in an eighteenth-century dancer. As such, they hold the keys to help reconstruct the minuet as it was danced at this time, using the svikt technique. In our oral presentations and embodiment of an alternative interpretation of the eighteen-century minuet, we have experimented, therefore, with how large a vertical amplitude would have been performed in folk dance. Other material that has survived through continuous tradition, such as the polonaise, allows the drawing of better supported interpretations. The polonaise has a clearly marked upbeat with bending of the knee on the last of the three beats in the music. This movement may be similar to the plié (bending) in the minuet step, and it appears in similar relation to the minuet music. This step was also known in the dance school circles in the Nordic region.29 The polonaise step, therefore, might be another example of a source supporting the alternative interpretation of the vertical movements of the minuet.

Constant waves lend a softer quality to the movements. We suggest that the raising on the toes is only one easily visible trait of wave producing, which the dancing masters used to describe the movements down and up in an easily understandable way. In usual locomotion the movements down and up are in a continuous flow, sinking and rising are not starting and stopping. The understanding that you put your foot down then rise back up upon it creates the very particular starts and stops that are characteristic of rigid recreations of historical dance. In natural locomotion, the sinking and rising occur while the foot is moving to a new place and continues while it is placed and receives the shift of weight. A rising conceived and performed as a separate movement is different from one that is part of a continuous flow. A small experiment may illustrate the problem: we try to describe ordinary walking in the terminology of the eighteenth century:

Try to walk like this: put your right foot forward, step on it and raise on demi-pointe. Put your left foot forward and step on it and raise on demi-pointe. (The corresponding sinking is often not mentioned). Following these instructions is likely to result not in a natural but an exaggerated type of walking movement with bigger vertical movements than usual. The experiment recreates the tendency, when interpreting verbal descriptions, to treat raisings (and lowerings) as isolated movements. It produces a locomotion quite peculiar to much of historical dance and hardly ever seen elsewhere.

It is evident from references by dancing masters that the down-and-up movements of the body were essential traits of the dances in the eighteenth and even earlier centuries.30 The simplistic way in which these movements are described, however, does not make a strict reading trustworthy. Taken literally, only the ankle movements are required for getting on the toes, and knees are kept straight. Therefore, general mechanics of locomotion, dances passed down through continuous practice, Rameau’s general call on the natural, and Hogarth’s more holistic description are all needed modifiers to the literary reading. We claim that it will allow for softer, more evenly undulating movements and for efficiency and strength to be applied in the movement production.

As we have suggested above, this collecting and application of different approaches can be seen as a method of triangulation. The idea of this method is to look at the dance from different angles. This multi-method approach serves to secure the theoretical validity of an investigation by using several methods to investigate the same matter. Between two points, one can draw a line; by adding a third point, one can make the lines cross or intersect. Just as fishers at sea have three points of reference to mark and relocate the position of a good fishing spot, this method of triangulation can guide us closer to an interpretation and closer to the matter we are investigating. It is essential to point out that the method will not yield one final and absolute answer. The method is a tool to help thinking about and understanding something better and to see more clearly what might otherwise be unclear.31

Concluding Remarks

The authors here criticise the practice among many dance historians for concentrating on one dance genre and one type of source. Although there were strong class divisions in earlier centuries and theatrical and social dance stood apart, the dances and the dancers belonged in the same world, and there was interaction between them.

When material from different source categories is combined, the methodologies used to guide the combination become essential. We apply, on one hand, triangulation, and on the other hand we apply gait studies and svikt analysis. Such studies show that the early-seventeenth-century experts did not understand the mechanics of locomotion sufficiently to describe it fully. This problem recurs when experts seek to reconstruct movements based on such descriptions and notations. An analysis of the mechanics of vertical movements during locomotion was not available to early dance notators nor to twentieth-century historians who collected vernacular accounts. The relevance of these mechanics for dance analysis was only discovered when the Norwegian anthropologist Jan-Petter Blom adapted findings from such studies to the field of dance analysis, more specifically to the analysis of Norwegian folk dance, in 1961.32

This approach has brought us to a series of proposals and contentions about the practical interpretation of various aspects of the seventeenth-century court dances that challenge the conventions and assumptions of many groups attempting to recreate historical dance and baroque dance.

- We propose that the minuet steps are based on a usual mode of locomotion similar to walking and that they, therefore, had regular svikt patterns of ups and downs throughout.

- We propose that dancing masters would only describe the larger decorative bendings and stretchings since they did not understand the vertical patterns’ mechanics and did not see smaller bendings and stretchings as relevant.

- We propose that the minuet step, even in the seventeenth century, had six svikts following the Danish and Finnish folk minuets and similar patterns in the Danish ballet tradition of the Elverhøj minuet.

- We suggest that the tendency to interpret the Feuillet notated minuet steps with foot transfers but without a marked bending should be reassessed. On the basis of the svikt analysis and due to mechanics of locomotion, we believed that also the eighteenth-century minuet step had a natural movement down and movement up on all six counts. The notators, most likely, refer to the highest level of a foot transfer, either the beginning where the foot takes on weight or at the end when it moves the weight to the next foot, or even to both points, without paying attention to—and, thus, without explicitly mentioning—the lowering of the body that, to some degree, must happen between the changes of support. Hogarth confirmed this by saying that the minuet involves a slightly greater raising and lowering of the body than occurs in ordinary walking.

- When the notation shows the vertical movement as a raising up on the toes and putting the heels down on the floor, we propose that this is a simple way of explaining more complex movements involving the entire body. Again, as Hogarth pointed out, the raising and lowering of the dancer’s body was to be performed ‘most smoothly’ […] ‘and free from sudden starting and dropping’.

- We propose that a sudden starting and dropping would result from isolated movements in ankles and knees as opposed to movements intended to raise and lower the whole body by using all joints and thus coinciding with Rameau’s ideal of dance that is not stiff or affected but ‘natural’.

- Our proposal for performing minuet steps would result in smoother waves, a more efficient take-off for each lifting of the body, and a more powerful dance, with soft and quite large down and ups, which may have been of different amplitudes.

We hope our discussions and reflections on the mechanism of locomotion, on the minuets that have survived through continuous transmission into the twenty-first century, and on a description independent from the seventeenth-century dancing masters can inspire further investigations into dances of the past.

References

Bakka, Egil, Danse, danse, lett ut på foten, Folkedansar og Songdansar (Oslo: Noregs boklag, 1970)

―, ‘Analysis of Traditional Dance in Norway and the Nordic countries’, in Dance Structures. Perspectives on the Analysis of Human Movement, ed. by A. L. Kaeppler and E. I. Dunin (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2007), pp. 105–12

Bakka, Egil and Siri Mæland, ‘The Manipulation of Body Weight for Locomotion—Labanotation and the Svikt Analysis’, in The Mystery of Movement. Studies in Honor of János Fügedi, ed. by Dóra Pál-Kovács and Vivien Szőnyi (Budapest: L’Harmattan, 2020)

Bakka, Egil, Siri Mæland, and Elizabeth Svarstad, ‘Vertikalitet i den franske 1700-talls menuetten’, Folkedansforskning i Norden, 36 (2013), 38–46

Blom, Jan-Petter, ‘The Dancing Fiddle: On the Expression of Rhythm in Hardingfele Slåtter’, Norsk Folkemusikk, 7 (1981), 305–12

―, ‘Diffusjonsproblematikken og studiet av danseformer’, in Kultur og Diffusjon: Foredrag på Nordisk Etnografmøte, Oslo 1960, ed. by Arne Martin Klausen (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1961), pp. 101–14

Centre de recereche du château de Versailles: ‘La danse française et son rayonnement (1600–1800)’, https://chateauversailles-recherche.fr/francais/colloques-et-journees-d-etudes/archives-1996-2020/colloques-et-journees-d-etudes-101/la-danse-francaise-et-son.html

Feuillet, Raoul-Auger, Chorégraphie ([1701]; Bologna: Arnaldo Forni Editore, 1983)

―, Chorégraphie ou l’art de d’écrire la dance, par caractéres, figures et signes démonstratifs (Paris: M. Brunet, 1701)

―, Recueil de dances (Paris: [n.pub.], 1700)

Franko, Mark, ‘Repeatability, Reconstruction and Beyond’, Theatre Journal, 41.1 (1989), 56–74

Hammergren, Lena, ‘Many Sources, Many Voices’, in Rethinking Dance History, ed. by Lbarraine Nicholas and Geraldine Morris (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), pp. 136–47

Hilton, Wendy, Dance and Music of Court and Theatre. Selected Writings of Wendy Hilton (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1997)

Hogarth, William, The Analysis of Beauty. Written with a View of Fixing the Fluctuating Ideas of Taste (London: J. Reeves, 1772)

Inman, Verne T., Henry James Ralston, and Frank Todd, Human Walking (Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1981)

Pécourt, Guillaume L., and Raoul-Auger Feuillet, Recueil de dances. Contenant un très grand nombres des meillieures entrées de ballet de M. Pecour (Paris: Gregg, 1704)

Rameau, Pierre, The Dancing Master, trans. by Cyril W. Beaumont ([1725]; Alton: Dance Books, 2003)

Saftien, Volker, Ars Saltandi (Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 1994).

Klara Semb, Norske folkedansar. Turdansar (Oslo: Noregs boklag, 1991)

Taubert, Gottfried, Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister, oder gründliche Erklärung der frantzösischen Tantz-Kunst (Leipzig: Friedrich Lanckischens Erben, 1717)

Taubert, Karl H., Höfische Tänze. Ihre Geschichte und Choreographie (Mainz: Schott, 1968)

Tomlinson, Kellom, The Art of Dancing Explained by Reading and Figures. Whereby the Manner of Performing the Steps is made Easy by a New and Familiar Method (London: Author, 1735)

Tschudi, Finn, ‘Om nødvendigheten av syntese mellom kvantitative og kvalitative metoder’, in Kvalitative metoder i samfunnsforskning, ed. by Harriet Holter and Ragnvald Kalleberg (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1996), pp. 122–29

Weaver, John, Orchesography (London: H. Meere, 1706)

Wood, Melusine, ‘What did they really Dance in the Middle Ages?’ Dancing Times, 25 (1935), 24–26

1 We use ‘folk dance’ in the sense of traditional dancing in rural society including the mirroring of this dancing by the revival folk dance movement.

2 Egil Bakka and Siri Mæland, ‘The Manipulation of Body Weight for Locomotion—Labanotation and the Svikt Analysis’, in The Mystery of movement: Studies in Honor of János Fügedi, ed. by Dóra Pál-Kovács and Vivien Szőnyi (Budapest: L’Harmattan, 2020), pp. 286–308.

3 William Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty: Written with a View of Fixing the Fluctuating Ideas of Taste. by William Hogarth (London: Printed by W. Strahan, for Mrs. Hogarth, and sold by her at her House in Leicester-Fields, 1772).

4 ‘Plié, est quand on plie les genoux. Elevé, est quand on les étend.’ Raoul-Auger Feuillet, Chorégraphie (Paris: [n.pub.], 1701), trans. by and qtd. in John Weaver, Orchesography (London: [n.pub.], 1706; repr. Bologna: Presso Arnaldo Forni Editore, 1983), p. 2.

5 Wendy Hilton, Dance and Music of Court and Theatre. Selected Writings of Wendy Hilton (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1997), p. 75.

6 Lena Hammergren, ‘Many Sources, Many Voices’, in Rethinking Dance History: Issues and Methodologies, ed. by Geraldine Morris and Larraine Nicholas (London: Routledge, 2018), pp. 136–47.

7 György Martin had already use to folk dance material in the interpretation of historical chain dance descriptions; Martin, György, ‘Die Branles von Arbeau und die osteuropaischen Kettentanz’, Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 15 (1973), 101–28.

8 Svarstad and Mæland also presented the project at the conference ‘La danse française et son rayonnement (1600–1800)’ in Versailles in 2012. See https://chateauversailles-recherche.fr/francais/colloques-et-journees-d-etudes/archives-1996-2020/colloques-et-journees-d-etudes-101/la-danse-francaise-et-son.html

9 For a draft version of the article, see Egil Bakka, Siri Mæland, and Elizabeth Svarstad, ‘Vertikalitet i den franske 1700-talls menuetten’, Folkdansforskning i Norden, 36 (2013), 38–46.

10 Melusine Wood, ‘What did they really Dance in the Middle Ages’, Dancing Times, 25 (1935), 24–26; Francine Lancelot, La Belle Dance: Catalogue Raisonné Fait En l’an 1995 (Paris: Van Dieren, 1996); Karl-Heinz Taubert, Höfische Tänze: Ihre Geschichte Und Choreographie (Mainz: Schott, 1968).

11 Mark Franko, ‘Repeatability, Reconstruction and Beyond’, Theatre Journal, 41.1 (1989), 56–57, www.jstor.org/stable/3207924

12 Pierre Rameau, Le maître à danser: Qui enseigne la maniere de faire tous les differens pas de danse dans toute la régularité de l’art, & de conduire les bras à chaque pas (Paris: Rollin fils, 1748); Kellom Tomlinson, The Art of Dancing Explained by Reading and Figures: Whereby the Manner of Performing the Steps is made Easy by a New and Familiar Method (London: Printed for the author, 1735).

13 We are not discussing what professional dance notators can or cannot do with the tools of the present, but rather what are usual limitations of descriptions and notations.

14 The movement aspects of a person’s habitus.

15 Raoul-Auger Feuillet, Recueil de Dances (Paris: Auteur, 1700); Feuillet, Chorégraphie Ou l’Art de Décrire la Dance, par Caractéres, Figures et Signes Démonstratifs (Paris: M. Brunet, 1701); Guillaume Louis Pécourt and Raoul-Auger Feuillet, Recueil de Dances: Contenant un très Grand Nombres, des Meillieures Entrées de Ballet de M. Pecour, Tant Pour Homme Que Pour Femmes, Dont la Plus Grande Partie Ont Été Dancées à l’Opera (Paris: Gregg, 1704).

16 Pierre Rameau, The Dancing Master; Kellom Tomlinson, The English Dancing Master; Gottfried Taubert, Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister.

17 Pierre Rameau, The Dancing Master, pp. 52–53. The descriptions of bendings and stretchings are underlined by the author.

18 Ibid., p. 53, emphases in original.

19 Rameau, The Dancing Master (1725), p. 100.

20 Blom, Jan-Petter,‘Diffusjonsproblematikken Og Studiet Av Danseforme’, in Kultur Og Diffusjon: Foredrag på Nordisk Etnografmøte, Oslo 1960, ed. by Arne Martin Klausen ([Oslo]: Universitetsforlaget, 1961), pp. 101–14.

21 Jan-Petter Blom, ‘The Dancing Fiddle: On the Expression of Rhythm in Hardingfele Slåtter’, Norsk Folkemusikk, 7 (1981) p. 305.

22 Egil Bakka, Danse, danse, lett ut på foten, Folkedansar og Songdansar (Oslo: Noregs boklag, 1970).

23 Egil Bakka, ‘Analysis of Traditional Dance in Norway and the Nordic Countries’, in Dance Structures. Perspectives on the Analysis of Human Movement, ed. by A. L. Kaeppler and E. I. Dunin (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2007), p. 108.

24 Turid Mårds, Svikt, kraft og tramp: En studie av bevegelse og kraft i folkelig dans (Trondheim: Rff-sentret, 1999), p. 115.

25 Egil Bakka’s illustration in Klara Semb, Norske Folkedansar. Turdansar (Oslo: Noregs boklag, 1991), pp. 83, 93; Blom, ‘The Dancing Fiddle’, 305.

26 William Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty, p. 147. The excerpt is from Shakespeare’s A Winter’s Tale.

27 A simple svikt (S) refers to one svikt done on one pace, double svikt (Ss) is two svikts performed on the same pace, the first on the right foot (R) and the second on the left (L).

28 Pierre Rameau, The Dancing Master, p. 2.

29 Klara Semb, Norske Folkedansar. Turdansar (Oslo: Noregs boklag, 1991), (p. 91).

30 Volker Saftien, Ars Saltandi (Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 1994).

31 Tschudi, Finn, ‘Om nødvendigheten av syntese mellom kvantitative og kvalitative metoder’, in Kvalitative Metoder i Samfunnsforskning, ed. by Harriet Holter and Ragnvald Kalleberg (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1996), p. 122.

32 Jan-Petter Blom, ‘Diffusjonsproblematikken og studiet av danseformer’, in Kultur og Diffusjon: Foredrag På Nordisk Etnografmøte, Oslo 1960, ed. by Arne Martin Klausen ([Oslo]: Universitetsforlaget, 1961), pp. 101–14.