POST REVIVAL–THE LATE TWENTIETH AND TWENTY-FIRST CENTURIES

Earlier chapters have dealt with the use of the minuet up into the early twentieth century, emphasizing the collection of the folk minuet and the revival activities in the folk-dance organization as a very important stage. The following chapters deal with new developments from the beginning of the twentieth century onwards, such as the establishing of a historical dance movement and the interpretation of historical sources into dance practice, which also includes the creation of a Swedish minuet. Another noteworthy trend is the development of ever-more advanced staging and choreographing based on folk-dance material, including the minuet.

17. Minuet Memories and the Minuet among the Swedish-speaking Population in Finland today

©2024 Gunnel Biskop, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.17

In some parishes of Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia, the minuet survived longer than in other parishes. There, the minuet was danced at weddings and parties, not once or twice at each event but many times. In Oravais, for example, in the summer of 1933, ‘at least 30 minuets were danced on the first day of the wedding, and even more the other day’, according to the dance researcher Yngvar Heikel.1 Several other parishioners recalled minuet dancing during this period. One is Professor Lars Huldén (1926–2016). He recalled a wedding in Munsala at the end of the 1930s at which guests ‘danced seventeen minuets in succession, with polskas between them, of course’.2 At that time, villages of Munsala challenged each other in minuet dancing.

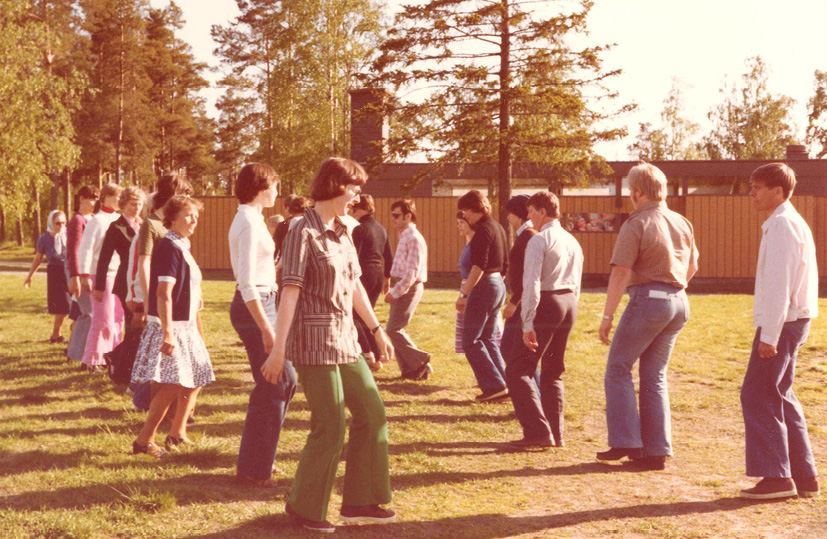

In the 1930s, some youth associations, such as Jeppo Ungdomsförening, decided that the minuet should be danced at common dance events to help ensure that it was not forgotten. People in Jeppo also managed to keep the minuet alive. Ann-Mari Häggman documented residents there dancing the minuet in film in 1977.3 She recalls that about twenty persons between the ages of twenty and seventy-five attended the recording site and danced the minuet. Häggman observed that the participants seemed to appreciate the improvised dance performance:

One danced quickly and unintentionally, generally in an unorganized manner with swinging arms, improvised hops, and stamping. Most dancers hopped the whole other half of the minuet, only a few elder ones danced with calm steps from start to finish. The dancers’ facial expressions—as they are preserved on the film—testify to an unprecedented dance pleasure.

Fig. 17.1 The minuet from Oravais in Ostrobothnia in Finland was danced by soldiers at the front during the war in the 1940s. Here, it is danced on a sunny afternoon in 1978 on a church hill in Oravais. Photograph by Stina Hahnsson. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

Bertel Holm’s Stories

In the mid-1990s, I interviewed several older men about minuets in Ostrobothnia.4 They were all veterans and had been in the war fought between Finland and the Soviet Union in 1941–44. One of these men was Captain Bertel Holm (1915–97) who came from the city of Vaasa (in Swedish: Vasa). As a young man, he had begun to dance in Vasa-Brage’s folk-dance group, and the first minuet he learned was the Oravais minuet. This was the beginning of his enthusiasm for minuets. He worked in the parishes of Lappfjärd, Tjöck and Oravais, teaching folk dances in these places for some time. After the war, Holm worked in Vaasa and participated again in Vasa-Brage’s folk-dance group. He arranged a summer gathering in Vaasa in the summer of 1945 for the Finlands Svenska Folkdansring (Finnish-Swedish Folk Dance Association, the central organization for the Swedish-speaking folk dancers in Finland). Through his useful contacts with Tjöck, Lappfjärd, Munsala, and Oravais, he succeeded in persuading tradition-bearers from these places to come to the gathering (called the folkdansstämma) to show their local minuets. This increased the significance of the dances, as the tradition-bearers became aware of the value in their minuets.5

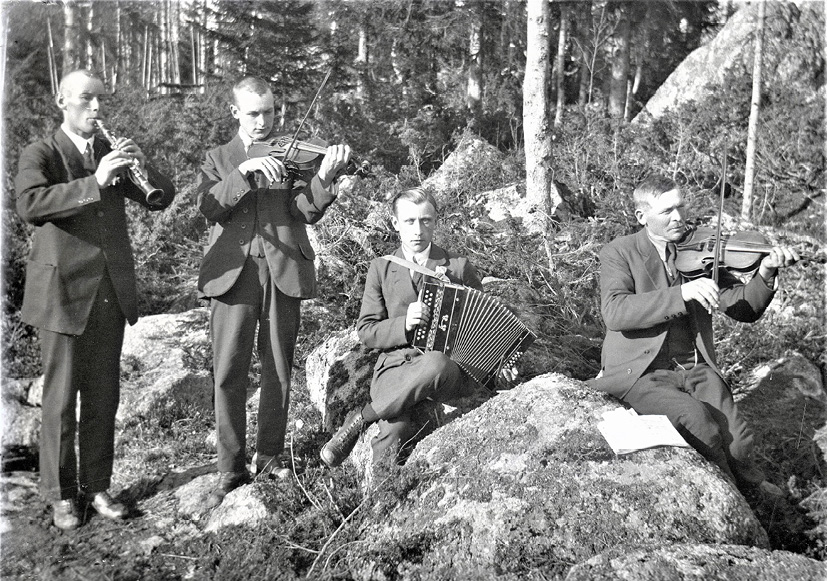

Fig. 17.2 Captain Bertel Holm kept spirits up among the soldiers at the front during the war in the 1940s by having the men sing, play, and dance the minuet. They had six violins with them at the front. Gunnel Biskop’s collection. Photograph, public domain.

Holm proved to be a significant friend of the minuet, even using it in such unusual situations as the war. During the fighting in Finland’s easternmost province Karelia, Holm was a machine-gun company commander within Infantry Regiment 61. The company consisted mainly of men from Oravais. Holm greeted his soldiers with the words ‘Finus, finus sun, and summer,’ even amid the most challenging situations. Hence, he received the nickname ‘Finus’. Holm also lifted the mood among his soldiers by having them sing, play, and dance the minuet. He considered this a survival strategy, helping his soldier to think about something other than the horrors they were facing in battle. Many times they danced on lawns, one veteran recalled. Another veteran told about a situation when Holm cheered the boys:

After the fighting at Säntämä, we marched to Tohmajärvi. It was a long march along untidy roads. Many soldiers could not make it with the marching pace of the others but stayed behind. The horses were also exhausted because they did not have the easiest task to get along with the heavy carts on the broken roads. When we arrived, Finus set up a minuet dance in the middle of the road. And, of course, some other wackos joined him. We would always sing Sillanpää’s march song [a famous Finnish military march during the war] when we marched. Such was our commander.

During a military advance, Holm played a harmonica and told his men that if they went to heaven during the march, it would be done under song and music, another veteran told me. Holm mentioned that they had six violins in the company, and when they moved, the players left them hanging from the carts with the machine guns. One of the veterans said that Holm forced him to bring his violin, even though he could not play, but he learned to do it during the war. Holm also learned to play the violin during the conflict.

Holm told me that the violin music lifted the mood and brought memories from home to the dugouts. ‘[O]ne played most Oravais and Vörå minuets with polska,’ he said. In an interview in the early 1990s, Holm explained what they once decided to do with the violin music at Shemenski during the trench warfare in 1943. One day, the company had access to loudspeakers, which were used to entice Russians to defect to the Finnish side. They started to play violin music—bridal marches and waltzes—through the loudspeakers, and the Russian soldiers responded with a shower of grenades. On another day, however, their violin-playing prompted a more musical answer, when the enemy replied with accordion and song. ‘We’re not gonna shoot now’, Captain Finus commanded, ‘Not a shot!’6

Life on the frontline, because it involved much waiting, could be boring. Whenever possible, artists and theatre groups would travel to entertain the soldiers. The folk-dance group of Vasa-Brage made such a trip to perform at Svir on 4–8 June 1943. It is not apparent from available sources whether Holm was responsible for or participated in the visit. The annual report of the dance group included a description of how they danced and performed while Russian grenades were exploding in the surrounding area:

On June 4, 4 ladies and 3 men leave, while additional participants come from the front. The trip to Svir takes two nights and one day. The program consists of speech, music, folk dances, and folk song dances. General rehearsal will occur during the daytime in the regiment’s newly built canteen, which accommodates 300 men. The expected participant fails to arrive, but another folk dancer saves the situation. During the rehearsal, Russians shoot grenades in the area, but the rehearsal can continue as none of them meets the building. After the rehearsal, Colonel Heinrich’s dugout will be visited. At the beginning of the party, the Russians start shooting again, but the party must be held since the men are gathered. The dance group performs its best dances in front of the regiment’s approximately 250 Ostrobothnians and officers and Lottas [members of an auxiliary paramilitary organisation for women in Finland], and they achieve the best contact ever with the audience. The trip is due for special reasons already the following morning. The journey leaves a memory for life at all the participants.7

This folk-dance performance was not the only one held on the frontlines. A veteran in Munsala, Per Rögård (1923–2008), explained in an interview in 1985 how, at Finus’s call, he had been involved with the minuet at the front:

Even at the front, we danced the minuet, but we were only men there. It was in Russian Karelia once when our Finland-Swedish unit went marching past a place where a Finnish unit had constructed a dance pavilion and performed folk dances with men only as dancers. They then asked us if we knew any folk dances, while Bertel ’Finus’ Holm shouted: ‘Come on boys, those who can do the minuet.’ Five couples got together, and we received a lot of applause from the Finns as well.8

The fact that there were five couples meant that ten men in the company could dance the minuet.

In a letter to me, Holm said that before the demobilization in November 1944, the minuet from Oravais was danced on various occasions, including as their final act as a company. To his soldiers, who had been together for three years and five months at the front, Holm gave an order that ‘the one who could not dance the Oravais minuet won’t be released to “civil”’. According to Commander Holm, the men obeyed this last order, dancing their final minuet together at Jeppo railway station before they were separated.

It was not only Holm who danced the minuet under challenging situations. Lars Huldén has said that in 1944 he was seventeen years old when he was summoned to the war. While he and other seventeen- and eighteen-year-olds from Ostrobothnia headed south by train to the frontline at Karelia, the train stopped at Haapamäki station. At the same time, a train came from the south, stopping at the same station. In that train, there were some boys from Munsala on their way north, home on leave. When they met each other at the station in Haapamäki, they danced the minuet and sang the music.9

Fig. 17.3 The bank director Edvin Lygdbäck in Oravais in Ostrobothnia in Finland talked about his memories of minuet dancing in interviews. Gunnel Biskop’s collection. Photograph, all rights reserved.

Edvin Lygdbäck’s and Others’ Stories

Through Holm, I made contact with some of his soldiers who had participated in the minuet dancing during the war. One of them was the Oravais bank director, veteran Edvin Lygdbäck (1923–2001). He was nineteen years old when he was ordered to the front to join Finus’s company in 1942. Lygdbäck went out to the war already knowing the minuet and said that he danced it whenever Holm ‘asked for something’—his description of Holm’s whims. He was present when, in 1943, Holm arranged a ‘minuet night’ and taught the dance in the military canteen in Svir. Those who could already dance the minuet helped to teach others who could not: ‘We could spend an entire hour dancing minuet,’ Lygdbäck recalled. He also remembered dancing the Oravais minuet with the others on a bridge near Lotinapelto when the unit moved to Viborg.

Lygdbäck also shared with me his memories of the minuet and other dancing from the time before the war. He explained that it was considered necessity for young people at the time to know how to dance the waltz, schottische, polka, and minuet. The minuet was taught by imitation rather than formal instruction: one watched someone older and simply started joining in. While still learning, children were directed to a place at the lower end of the minuet row during weddings. Lygdbäck said that he had learned the dance at a wedding in 1935 when he was twelve years old. The person who taught him was his grandmother’s sister, who had been born in 1866. He recalled that this ‘aunt’ had unsoled boots of thin and soft leather on her feet and danced very softly and neatly: she did not hop. Describing the ‘dance education’ he received on the third day of this wedding, Lygdbäck remembered that ‘[t]he musician would have some spirits, the aunt also had, there were three to four women in the yard, and everyone drank some spirits. The musician sat down and played his two-row accordion all day’. This is how the twelve-year-old boy had learned to dance the minuet.

Fig. 17.4 Wedding entourage in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1934. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. SLS 865 B 259. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_SLS+865+B+259, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 17.5 Wedding in Ostrobothnia in Finland. The bride and groom toast with the guests while the fiddlers play, 1922. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. SLS 865 B 258. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_SLS+865+B+258, CC BY 4.0.

Another who also danced very softly was Lygdbäck’s grandmother. He described her movement in the minuet in the following way: ‘she smoothed more, danced neatly, pulled out of the beat, left behind, got back to the beat again’. Lygdbäck incorporated this gentle quality into his dancing and felt that it was important for better understanding the minuet’s meaning: it was a kind of devotional feeling in the body. The minuet was considered a finer dance than some others in the late 1930s, he explained. Those who knew it felt superior to others who did not. Lygdbäck also thought that the minuet was not just a dance, but a display of skill used by the boys to impress the girls. Besides, they were proud to have the dancing skills. In his youth, all the ‘real boys’ could dance the minuet. Not all had Lygdbäck’s skill. Those who knew they were not among the best stood in the middle or farther away from the table end, towards the lower end of the row. This was natural, and there was nothing special about it. Everyone preferred to dance next to someone who knew the dance.

Lygdbäck recalled some variety in how the minuet was danced. Most typically, he explained, it was danced using ordinary steps in the first half and steps with hops in the other. However, older people could dance without hopping. He had also danced the minuet in a way that involved hopping from start to finish.

Fig. 17.6 Dance orchestra in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1922. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. SLS 865 B ÖTA 135, 20097. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_%25C3%2596TA+135+foto+20097, CC BY 4.0.

As the number of transitions in a minuet was decided by the leading man, a signal was needed to communicate when the stampings should begin. When Lygdbäck held this lead position, dancing at the table end, the signal used was that the whole row of men would join hands. If there were two rows of dancers, the second row could be at an angle with the first one, but this second row still followed the decisions of the leading man in the first row. All would keep an eye on him as the dance proceeded to know when to begin the stamping. The leading man was never allowed to ‘go sleeping’, as Lygdbäck expressed it; he must remain alert and elevate the other dancers’ moods. Sometimes men in that leadership position would spontaneously ‘cry out’ when they got into the spirit of the dance. It was also important, he remembered, that the man at the table end needed to dance with a girl who also knew what to do. All girls could not dance the minuet, he remembered. The polska was danced in two ways, ‘slow polska and faster polska’. During the dance, perhaps most during the polska, the men would shout but the women did not, Lygdbäck reported.10

In Lygdbäck’s youth, two to three minuets were danced at common dance events. Over time, the number of minuets during a dance night reduced as dance orchestras began to grow and could not play the minuet. Lars Huldén had similar experiences from the 1940s, recalling a time when it was no longer certain that an orchestra would play the minuet at a common dance event. Huldén said dancers tried to demand a minuet, explaining that

there were a few couples who went to stand at the table end, as it was called, and others got up after them. It was considered the musicians had to play the minuet. And when orchestras that could not or refused to play the minuet appeared in the 40s, those who love the minuet reacted with annoyance.11

Fig. 17.7 In Munsala in Ostrobothnia in Finland, the minuet survived into the 1990s. Here, tradition bearers, dressed in folk costume, perform in Stockholm in 1987. Photograph by Stina Hahnsson. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

Lygdbäck’s wedding, in 1946, was a big, three-day event with five hundred guests. After the ceremony, they toasted the bridal couple and swayed to the accompanying music. Coffee and the first meal were consumed at the wedding house. Then the party moved to the building that housed the youth association, with two musicians leading the procession and playing a bridal march. There, the dancing started with a bride’s waltz, and during the second waltz, the closest family joined the dance. Lygdbäck gave further details:

After 3-4 dances of tango, schottische, waltz or foxtrot, someone sat at the table end and then the minuet started. Then followed 12 minuets in succession, then one was supposed to have fitness, the bride always as the first couple, the groom as the second. Then again, other dances between, then one or two minuets again. If the bridal couple was not on the floor first, it was a violation of the etiquette.

Many other people also mentioned that it was common at weddings in the latter part of the 1940s for up to fifteen minuets to be played in succession, with several rows dancing at the same time. Generally speaking, the minuet experienced a boost after the war, as nostalgic feeling towards one’s home region was intensified.

Fig. 17.8 Several hundred wedding guests gathered in the yard for photography in Oravais in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1937. At this time, many minuets were danced and the fiddler played different melodies for each minuet. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. SLS 865 B 431 The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_SLS+865+B+431, CC BY 4.0.

Corroborating Lygdbäck’s account, Ann-May Nystedt (b. 1942) from Oravais confirmed that it was poor etiquette if the bridal couple was not first on the floor. In her memories from the 1950s, the bride was invited first and danced every dance. When a married male guest asked the bride to dance, the groom would look for that guest’s wife and invite her to dance as the second couple. When an unmarried male guest invited the bride to a dance, he told the groom which woman to invite. This custom was also noted by a male informant (b. 1894) in his responses to a 1964 questionnaire.12 Nystedt also recalled that the first two men changed places for the second minuet so each could dance with the bride, while the others in the row danced with the same partner for the duration of both dances.

Fig. 17.9 The author, Professor Lars Huldén, grew up in Munsala in Ostrobothnia in Finland. He learned to dance the minuet as a child and told about his memories in texts and in interviews. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop, 1984. © Gunnel Biskop.

As I have discussed, it was customary to learn the minuet during childhood. Huldén’s account described the situation in which he learned the minuet in the mid-1930s:

In elementary school, when we were ten, twelve, we used to practice in the minuet on the breaks, especially after a wedding, where the children had been involved late into the night and made their observations. We used to troll or sing [...]. Actually, I learned it on my own on the cowshed floor on a spring day when we cleaned calf and sheep cribs. I loaded the cart, and someone else drove. We had two coaches, and the horse was fastened for them in turn. If I was quick, I could get the load ready before the rider was back with the horse and the next empty cart. In the meantime, I practiced the minuet. The middle of the dance was the hardest part. But in the end, I got everything right.13

The minuet could also be a loud dance. Huldén explained that, in the 1930s, shouts of joy could be heard from the boys as they hopped up and down during the latter part of the minuet. He said that the shouts and stampings on Saturday nights from the youth association house could be heard one kilometre away. Yngvar Heikel wrote that the polska was danced similarly, accompanied by loud shouts, full of the joy of dance. About the tempo of the polska, Huldén said:

In the polska, it’s like a skill test to pull up such a speed that someone or someone loses the footsteps and everything breaks down. [Swedish eighteenth-century troubadour] Bellman already talks about throwing a rival out of the polska after the beat’.14

Everyone tried to keep up with the fast pace.

Nystedt learned to dance the minuet when she was eight years old, in 1951. She also had memories of how to improvise in the minuet. She had seen two men improvise at a wedding in the 1950s: while crossing over to the opposite side of the formation, they would dance between the rows for a while, finally reaching their places. This provoked laughter from the audience. These improvisers, who she called ‘great dancers’, were born in 1909 and 1904. The younger was the groom’s father. The two men took turns dancing with the bride at the table end for fifteen to sixteen minuets in succession. The laughter was a sign of approval; these ‘great dancers’ improvised following local norms, since a father would not embarrass himself at his son’s wedding. Not just anyone could improvise in this way.

Christine Julin-Häggman, in Jeppo, told me about similar events, saying that it was common for the most skilled dancers to improvise and do tricks. She had memories from weddings in the 1950s and from her own wedding in 1985 of dancing the minuet in two long rows: ‘I remember one man who stood and brushed his legs just like a horse before the dance started. It was widespread. The most skilled dancers who knew what they were doing dared to do small tricks as well’.

Nystedt said that the table end position had a high status in the 1950s. When the music started playing, people shouted ‘minuet, minuet’ and ‘rushed to the table end, standing up and turning their arms and waiting for the row to get complete’. She also said that there was a break between the minuet and the polska. This break allowed time for one couple to ‘crawl’ to get together with a second couple and for all the couples in the row to form a star with another couple. In conjunction dance instructors’ wishes, musicians started playing the polska immediately after the minuet so that the audience would not begin to applaud between the minuet and the polska.

Nystedt also pointed out that everyone felt it was essential to have good body posture in the dance. One was not supposed to be ‘crooked’ but to hold up the body unashamedly. She related that one time, in the middle of a minuet performance in the 1910s, her grandmother (b. 1886) apparently thought that her sister did not have a right attitude and did not hold up her body correctly. What did Nystedt’s grandmother do? She jabbed her sister with her elbow in the side and erupted: ‘Behave yourself!’15

Edvin Lygdbäck had a firm opinion about how the minuet had come to Oravais. He thought it had come through Kimo’s ironworks in the 1700s. He told me:

Kimo ironworks was a state in the state, governed by the mining counselor [a high-rank honorary title in Sweden at that time] in Stockholm. A priest in Oravais could not punish an employment officer. At the ironworks, they spoke their dialect, they had their traditions, they were nice people, they had the silver buckles on the shoes and the walking sticks.

The implication is that workers from Stockholm had brought their traditions, including their dances, to Oravais.

It is peculiar that so many details in these memories of the twentieth century describe traditions that go back to the beginning of the eighteenth century: invitation, changing dance partners, and the importance of body posture, apart from the minuet steps themselves. This observation prompts the question: Can the minuet in Ostrobothnia have been danced in an unbroken tradition from the beginning of the eighteenth century to the present? I can only give an affirmative answer to this. After all, the form of the minuet also goes back to the ordinary minuet.

Fig. 17.10 In dancing, the shoes were worn out, especially if someone danced a minuet for two days at a wedding. A cobbler fitting a shoe with a new heel in 1921. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. SLS 865 ota135_19815. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_ota135_19815?sid=2976468705, CC BY 4.0.

Long-lasting Dance

Several reasons might explain why the minuet has been danced for such a long time in some Ostrobothnian parishes. One explanation is that the minuet was danced and appeared in all situations, both at common dance events and weddings (both within the ceremonial part and as a common dance for guests). I like to think that the main reason was the minuet’s position as a ceremonial dance: as a pällhållare dance—as it was called in Ostrobothnia—at the wedding. It is typical for more traditional customs to survive primarily at weddings.

The very long ceremonial portion of the wedding ceremony required the hosts to adequately possess enough finances to allow for several days’ celebrations. It was also crucial that the Ostrobothnia weddings were celebrated in the same house—in one place—as opposed to the customs of the Swedish-speaking population in Nyland [Uusimaa] and the Finnish-speaking population in general, where the wedding was celebrated in two farms, first in the home of the bride then in that of the groom. Because no moving was required in Ostrobothnia, there was time for longer ceremonies. It was also significant that many priests were willing to dance. The priest danced the first minuet with the bride. The introduction of the ceremony was almost a ritual led by a priest. The ceremony was seen as an injunction, a duty, more than a pleasure. There was also a certain kind of ranking in the order of the pällhållare [bridesmaids and groomsmen] at the wedding, even regarding the dance skills in general, and there were codes and concepts that were a part of tacit knowledge passed down in the village.

The minuet’s strength was that the dance could be shaped according to the situation in which it occurred: as a single couple’s dance, two or more couples at the same time, or by the entire assembly. Consequently, the minuet was both a couple and a group dance. Common people could make the minuet a dance of their own within local norms by altering, for example, the number of couples that danced in the ceremony. Furthermore, the minuet was danced at different paces—slowly and graciously with devotion and solemnity when used in the ceremonial part of a wedding and more quickly, and joyfully, sometimes with hilarity and intensity, as a common dance.

I would like to say that the minuet was a ‘men’s dance’. Although it is danced in couples, a man directed the dancing from the table end. The minuet allowed the man in this position to display his dance skills, to show off. It also allowed those who did not yet have the required skills to dance by providing a place further away from the table end. The male partner took the leading role in specific situations, such as when, as a groom, he danced the minuet with his bride at his own wedding. Then the groom stood at the table end, and he was the leading man. Before the marriage, the groom had probably participated in the pällhållare dance at previous weddings and even danced with the bride. In such situations, he took turns with the other young men to lead the dance from the table end. Women also showed off their dance skills, first in the pällhållare dance and later as a bride themselves.

The pällhållare dance was an exciting moment that young men and women anticipated from their childhood. Because they were watched closely, they took pains to learn to dance. There were, of course, some men—a groom or a pällhållare youth—who could not dance the minuet, and they could ask a close relative to dance instead, according to information from Oravais and Lappfjärd. But that was probably not something that was the most desirable option.16

War veteran Edvin Lygdbäck had told me that, in the 1930s, the boys were proud to know the minuet. The minuet was also a dance for all ages—from young children who ‘tumbled’ around the dining corner to the oldest grandfather dancing with the grandson’s young bride. A prerequisite for the long life of the minuet was, of course, that there were musicians who could play minuets and polskas and had a sufficiently large repertoire for different situations. Unfortunately, the dance orchestras who could not play minuets and polskas in the 1940s contributed to the minuet’s decline.

Fig. 17.11 ‘It was simply the case that if you couldn’t dance a minuet, you weren’t a real man,’ said a war veteran Per Rögård in Munsala in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1985. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop after a film by Kim Hahnsson. © The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland.

In Jeppo, Viktor Andersson (1901–74), a leading musician, explained that the fast pace of the minuet demanded great vitality from players. He stated in a 1974 interview that he ‘had to play the minuet faster and more vigorously to compete with the newer dances’.17

I think the war veteran Per Rögård in Munsala answered why the minuet has lived so far in time in Ostrobothnia. He said, in 1985, ‘It was simply so that if you could not dance the minuet, you were not a real man.’18

In the latter part of the twentieth century, when the minuet was no longer danced as a ceremonial dance at weddings, the men who once danced at the table end were often the same ones who sought to keep it alive as a common dance. This is what happened in Munsala in the 1960s when the musician Erik Johan Lindvall (1902–86) began to teach the minuet to keep the tradition going. He taught Bror Spåra (b. 1935) how to stand at the table end. Together with his wife, Spåra continued to learn the minuet during the 1980s. When Spåra stopped dancing at the table end and stopped learning the minuet, it was not danced as often anymore. However, in the Ostrobothnian minuet regions, there are still people who can dance the minuet. Minuets are danced at parties of various kinds, such as weddings, birthdays, and other gatherings. There are also special dancing evenings, where the minuet has the leading role.

|

Video 17.1 Tradition bearers from Jeppo in Ostrobothnia in Finland play and dance minuet and polska at the Nordic folk dance event NORDLEK 97 in Vaasa in Finland 1997. The folk music group Jeppo Bygdespelmän plays under the direction of Christine Julin-Häggman. The minuet is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Uploaded by segasovitch, 5 April 2012. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/c85115c4 |

Today, enthusiasts have a significant role in keeping alive knowledge of minuet dancing. In Jeppo, music teacher Christine Julin-Häggman occupies this role. She teaches dance and music to children and young people in schools in Jeppo and leads several groups of young musicians of different ages. These dancers perform their minuet at various events, such as concerts, weddings, hometown feasts, and festivals. Jeppo is known today for having many musicians, and several of them have been nominated to the level of ‘Master Musicians’ at the Folk Music Festival in Kaustien. It is common for the musicians to learn the melodies on their own. In Oravais, Ann-May Nystedt is the tradition-bearer of the minuet, and she, together with her husband Olof, has been the driving force for decades. In southern Ostrobothnia in Tjöck, Ann-Mari Ahlkulla was the one who led the minuet dance into the twenty-first century.

|

Video 17.2 Minuet from Jeppo in Ostrobothnia in Finland. The group Jepokryddona perform at Kaustby Festival while master folk musician Christine Julin-Häggman and Lars Engstrand play a minuet. The minuet is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Uploaded by KulturÖsterbotten, 13 July 2019. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/98697a2f |

|

Video 17.3 Minuet and polska from Tjöck in southern Ostrobothnia in Finland. The old clothing, which today is called ‘national costume’, survived in Tjöck in southern Ostrobothnia until the 1940s. After this time, the tradition bearers have continued to dress in national costumes when they perform their minuet and polska. Here, Tjöck residents present their minuet at a fiddlers’ gathering (spelmansstämma) in 2019. Music by Tjöck Spelmanslag. The minuet is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Uploaded by Jessica Westerholm, 9 May 2023. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/0c33910f |

The Minuet within the Organized Folk

Dance Movement

The minuet has been danced in popular tradition until the present day in Ostrobothnia, but it also has been danced in an organized form within the folk-dance movement from the beginning of the twentieth century. When the Föreningen Brage i Helsingfors (Brage Association in Helsinki) was founded in 1906, the minuet was one of the dances immediately included in the dance repertoire. The same year, people from Oravais taught the minuet from their home region for the theatre performance ‘Österbottniska bondbröllopet’ [‘Ostrobothnian Peasant Wedding’]. From 1906 to 1937, nearly fifty performances were given. Members of Föreningen Brage i Helsingfors learned of minuet variations from students who moved to Helsinki: one that Brage started dancing was the minuet from Lappfjärd, and over time the minuet from Vörå also became popular.19

Although the minuet’s length was not predetermined in popular tradition but decided by the leading man, the folk-dance movement published guidelines establishing how many transitions were to be danced before the middle part of the minuet and how many further transitions were to be danced before the performance ended. However, the group continued use the traditional signals to indicate the switch. Determining the set length was the only change made to the traditional style of popular dancing by the folk dancers. There were practical reasons for this: when several groups performed the minuet at the same time, it was thought that all groups should be in the same phase of the minuet, that is to say, start the minuet at the same time, dance the middle part at the same time, and end at the same time.

Fig. 17.12 Folk dancers from Brage in Helsinki perform with a minuet from Purmo in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1983. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop. © Gunnel Biskop.

Today, the minuet is danced in every folk-dance group around the Swedish-speaking areas of Finland, and every folk dancer in this network, young and old, can dance the minuet. These folk-dance groups belong to the central organization of Finlands Svenska Folkdansring. Within it, a riksinstruktör [national instructor], together with a group of experts, sets a dance itinerary for each year. Finlands Svenska Folkdansring’s annual dance program always includes a minuet, sometimes two. The same minuet usually remains on the program for three to four years. The national instructor teaches the dances on courses to local instructors and musicians. Learning starts from the basics, with the rhythm and steps, and then covers the minuet’s different phases. Through this method, the local instructors learn more about the traditions of the minuets as well. The local folk-dance instructors then teach the minuet dances and traditions to their folk-dance groups.20

Within the folk-dance movement, the difficulty lies in interpreting the descriptions and teaching the minuet. However, Finlands Svenska Folkdansring is in a rare position in this regard. The frames of reference for interpretation of the descriptions and the transmission of minuet traditions have existed as unbroken from when the minuets were recorded in the 1910s and by Yngvar Heikel in the 1920s. Heikel, who recorded the minuets, also taught them all until the 1950s. After that, the national instructors, who had been pupils of Heikel, continued the practice. All of the national instructors have learned from the previous generation and have had practical dance knowledge. They have also educated themselves to become folk-dance instructors, and they have thus adopted a frame of reference to interpret the descriptions and teach the minuet.

Fig. 17.13 and Fig. 17.14 Folk dancers from Finlands Svenska Folkdansring perform a minuet from Oravais in Ostrobothnia during the Europeade 2017 festival in Turku. Photograph by Timo Hukkanen. © Timo Hukkanen.

Folk-dance groups meet once a week under the guidance of their local dance instructor who teaches the dances. Characteristically, folk-dance instructors have been dancing in junior teams since childhood and have been trained to serve as instructors. Like those working on the national level, these local instructors also have practical knowledge and reference frameworks to interpret the dance descriptions. Here, geographical variations of the minuet in different areas enter the picture. The source of the minuet culture in Finland’s Swedish-speaking areas is Yngvar Heikel’s work Dansbeskrivningar [Dance Descriptions], 1938, a work discussed earlier in Chapter 11. The instructors can use this source and interpret a particular minuet’s record and teach it in their group. The minuet may be different from that set on the Finlands Svenska Folkdansring’s yearly itinerary. Some folk-dance groups specialize in minuets from different areas, whereas others may dance the same minuet year in and year out.

Like the folk dancers, the folk-dance musicians also go to the source material. They use Otto Andersson’s recordings of melodies, choosing from among his two hundred seventy-six published minuets a melody from the same geographic area as the dance it will accompany.21 In the folk-dance groups, they try to dance the minuet as recorded, but each performance is a one-off phenomenon: each performance differs from the others. Plus, within each dancing group, individuals have their own styles.

|

Video 17.4 Minuet and polska from Oravais in Ostrobothnia in Finland. Demonstration video for the Finnish groups at Europeade 2017 in Turku in Finland. Folk dancers from Haga Ungdomsförening (the Haga Youth Association) and Föreningen Brage i Helsingfors (the Brage Association in Helsinki) dance. Note: the minuet is a little shortened for audience performance. Uploaded by Europeade 2017 Turku, 2 December 2016. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/919a8e6c |

|

Video 17.5 Minuet and polska from Oravais in Ostrobothnia in Finland. Two hundred folk dancers from Finlands Svenska Folkdansring perform the minuet at Europeade 2017 in Turku in Finland. The minuet is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Uploaded by Pargasit, 23 June 2019. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/11191d0e |

The purpose of Finlands Svenska Folkdansring is to sustain dance traditions, including the minuet, from different regions. Minuets from different parts of the Swedish-speaking areas of Finland differ slightly from each other. Even various villages within the same area could vary in detail from each other. Finlands Svenska Folkdansring tries to preserve the breadth of this minuet culture by encouraging the dancing of minuets from different areas. Folk-dance groups perform the dances, including the minuet, at countless exhibitions for audiences at parties and events of various kinds and festivals. The minuet is also performed jointly by all Swedish-speaking folk dancers at the Finlands Svenska Folkdansring’s folkdansstämma, an annual three-day summer gathering. This event always ends with a celebration performance for the audience, and it is common for the dancers to dress up in folk costumes at these performances.

|

Video 17.6 Minuet and polska from Oravais in Ostrobothnia in Finland. Folk dancers from Finlands Svenska Folkdansring perform in Jakobstad, 2019. The minuet is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Uploaded by Ralf Karlström, 29 June 2019. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/ed779e86 |

The Swedish-speaking folk-dance groups do not perform only in their own country. They join triennial Nordic folk-dance summer gatherings, so-called NORDLEK, arranged by turns in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, as well as in the autonomous territories of the Faroe Islands, Greenland (belonging to Denmark) and Åland (belonging to Finland). During these gatherings, folk dancers from the Nordic countries also dance the minuet. Each NORDLEK also ends with a big dance performance. At these performances, Swedish-speaking folk dancers from Finland through the ages have danced

the minuet.

|

Video 17.7 Folk dancers from Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, Finland, perform at NORDLEK in Steinkjer, Norway in July 2012. The minuet is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Uploaded by folkblueroots, 10 March 2012. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/d97e7b68. See the minuet at timecode 1:20. |

Besides surviving through performances, minuets are danced in everyday social contexts, when folk dancers come together for socializing, such as Christmas parties, birthday parties, and other private parties. In such cases, man number one—as the leading man is called within the folk-dance movement—determines the minuet’s length, as the tradition dictates. Some special arrangements are also organized for folk dancers and people who have not danced the minuet. At such events, the minuet is taught from the basics, and students only dance this one dance for an entire day.

Fig. 17.15 and Fig. 17.16 Minuet is danced today in various contexts. The minuet line stretched throughout the ballroom as the guests danced minuet from Oravais. Gunnel Biskop, author of this text, in a white blouse, celebrated her 50th birthday in 1993. Photographs by Viola Stjernberg. © Viola Stjernberg.

|

|

Tradition bearers that I have spoken with have emphasized that people like to dance next to someone who knows the minuet well. This same tendency has been found in historic sources around the Nordic region. During the fifty years I have danced the minuet as a member of a folk-dance group, I have realized the importance of the partner and those who dance beside me. When everyone knows the minuet and follows the rhythm, then everyone enjoys the dance, holds up their body with strong posture, and is proud of the dance. The experience one feels in that moment is almost indescribable. Through eye contact with my partner and with people around me, and by dancing and waving together as a whole row, I sense the rhythm in the air and the proximity of the others without necessarily looking at those who dance next to me. Such a nonverbal sense of togetherness with the group was likely felt by dancers in the past. The exhilaration of the shared experience and feeling also helps to explain why the minuet has survived through the centuries.

Fig. 17.17 The minuet from Oravais is danced with hop steps at Gunnel Biskop’s doctoral dinner, 2012. Photograph by Karin Långbacka. © Karin Långbacka.

The minuet in Finland’s Swedish countryside is included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland. Finland signed the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Intangible Heritage in 2013. The goal of the Convention is, among other things, to list, recognize, and protect the living heritage. The National Board of Antiquities is responsible for the implementation of the listing in Finland. In 2017, for the first time, it became possible to apply for a tradition to be included in the National Inventory of Living Heritage in Finland, and among the phenomena included by the Ministry of Education and Culture was the minuet.

Concluding Remarks

In Ostrobothnia in Finland, some people know how to dance the minuet today. The minuet is continuously on the teaching syllabus within organized folk-dance groups, and all Swedish-speaking folk dancers in Finland can dance the minuet. It is danced in folk-dance groups and in private gatherings. The minuet is also frequently performed for the public, in Finland, in the Nordic countries, and at festivals worldwide.

References

Archival material

Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland (SLS) (The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland), Helsinki

SLS 803

Secondary sources

Andersson, Otto, VI A 1 Äldre dansmelodier. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 400 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1963)

Biskop, Gunnel, ‘Bertel Holm och menuett i krig och fred’, Folkdansforskning i Norden, 24 (2001), 13–15

―, ‘Brages danslag skördar och sår’, in Brage 100 år. Arv — Förmedling — Förvandling, ed. by Bo Lönnqvist, Anne Bergman, and Yrsa Lindqvist. Brage årsskrift 1991–2006 (Helsingfors: Brage, 2006), pp. 80–119

―, Dans i lag. Den organiserade folkdansens framväxt samt bruk och liv inom Finlands Svenska Folkdansring under 75 år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2007)

―, ‘Menuetten i Finlands svenskbygder efter 1850’, Folkdansforskning i Norden, 36 (2013), 15–30

―, Menuetten — älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden — särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder — under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdanring, 2015)

Brage Årsskrift (Helsingfors: Brage, 1946)

Häggman, Ann-Mari, ‘Filmen återger glädjen i dansen’, in Fynd och forskning. Meddelanden från Folkkultursarkivet 7. SLS 496 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1981), pp. 157–82

Huldén, Lars, ‘Danser som jag minns’, Folkdansaren, 31.3 (1984), 7–10

―, ‘Får man hoppa i menuetten?’, Folkdansaren, 6 (1984), 3–10

Smedberg, Ulf, ‘Videobandare bjöds på Munsala-menuett’, Vasabladet, 6 June 1985

Wadström, Aina, ‘Frieri- och bröllopsbruk’, Hembygden, tidskrift för svensk folkkunskap och hembygdsforskning i Finland, 2 (1911), 80–90

Vester, Göta, ‘Dialog’, Orvas 1994, Oravais Hembygdsförening (1994)

1 Gunnel Biskop, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdanring, 2015). This chapter is mainly based on this book.

2 Lars Huldén, ‘Danser som jag minns’, Folkdansaren, 3 (1984), 7–10.

3 Ann-Mari Häggman, ‘Filmen återger glädjen i dansen’, in Fynd och forskning. Meddelanden från Folkkultursarkivet 7. SLS 496 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1981).

4 Gunnel Biskop, ‘Bertel Holm och menuett i krig och fred’, Folkdansforskning i Norden, 24 (2001), 13–15.

5 A similar situation occurred in Denmark in 1930, when dancers from Bjerregrav in Jutland had come to Skanderborg to perform their menuet for folk dancers at a folk-dance meeting. See Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 205–08.

6 Göta Vester, ‘Dialog’, Orvas 1994. Oravais Hembygdsförening (1994); Biskop, Menuetten, p. 150.

7 Brage Årsskrift 1946; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 149–53.

8 Ulf Smedberg, ‘Videobandare bjöds på Munsala-menuett’, in Vasabladet 6 June 1985.

9 Huldén, ‘Danser som jag minns’; Biskop, Menuetten, p. 152.

10 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 153–56.

11 Huldén, ‘Danser som jag minns’, p. 8.

12 SLS 803:25.

13 Huldén, ‘Danser som jag minns’, p. 8.

14 Lars Huldén, ‘Får man hoppa i menuetten?’, Folkdansaren, 6 (1984), 3–10.

15 Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 156–58

16 SLS 803:24; Aina Wadström, ‘Frieri- och bröllopsbruk’, Hembygden, Tidskrift för svensk folkkunskap och hembygdsforskning i Finland, 2 (1911), 80–90; Biskop, Menuetten, pp. 159–61.

17 Häggman, p. 169.

18 Smedberg.

19 Gunnel Biskop, ‘Brages danslag skördar och sår’, in Brage 100 år. Arv—Förmedling—Förvandling, ed. by Bo Lönnqvist, Anne Bergman, and Yrsa Lindqvist. Brage årsskrift 1991–2006 (Helsingfors: Brage, 2006), pp. 80–119.

20 Gunnel Biskop, Dans i lag. Den organiserade folkdansens framväxt samt bruk och liv inom Finlands Svenska Folkdansring under 75 år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2007); Gunnel Biskop, ‘Menuetten i Finlands svenskbygder efter 1850’, Folkdansforskning i Norden, 36 (2013), 15–30.

21 Otto Andersson, VI A 1 Äldre dansmelodier. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 400 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1963).