18. Minuet Constructions and Reconstructions

©2024 Anna Björk and Petri Hoppu, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.18

Unlike in Denmark and Swedish-speaking Finland, the vernacular or popular minuet did not survive in the continuous tradition of Sweden and Finnish-speaking Finland sufficiently long for it to be documented in detail. Although it had been danced since the seventeenth century, the vernacular minuet disappeared rapidly towards the end of the nineteenth century, and in neither Sweden nor Finnish-speaking Finland do any detailed descriptions exist. However, thanks to intensive co-operation among Nordic folk-dance organizations, Swedish and Finnish folk dancers were able to watch Danish and Finnish-Swedish minuets performed at various events, so they knew the dance and how it has appeared since the early twentieth century. Thus it is conceivable that Danish and Finnish-Swedish from times past minuets influenced the recent emergence of new minuet forms among Swedish and Finnish folk dancers.

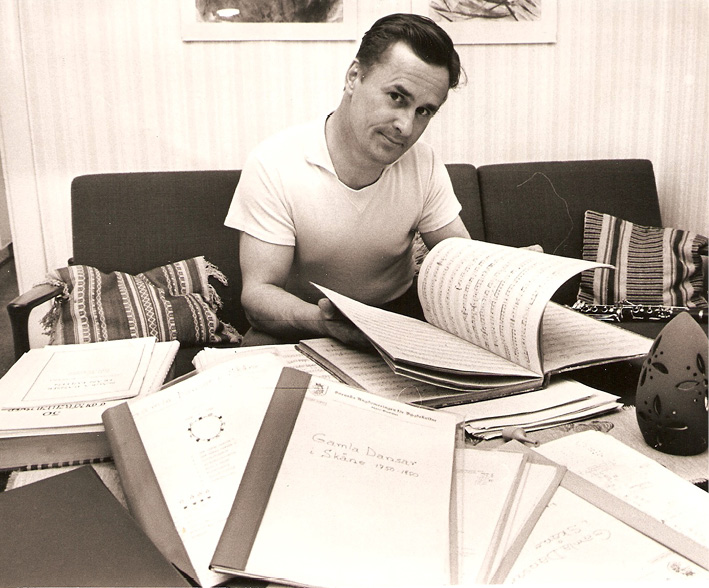

In Sweden today, the minuet is a popular dance within some folk-dance settings. It is danced at social dance events, taught in dance workshops and courses, and is often used in folk-dance performances. The minuet was reconstructed by Börje Wallin, one of the non-scholar folk-dance researchers who influenced the dancing and the dance repertoire within the folk music revival in Sweden in the 1970s.1 Thus, in Sweden, the minuet went from being a pre-modern dance to becoming a part of today’s repertoire of the urban folk-dance communities. This first part of the chapter will describe Wallin’s process of reconstructing this dance.

The minuet experienced a different re-emergence in Finnish-speaking Finland, where folk dancers created new folk-dance choreographies for the stage beginning in the mid-twentieth century. During the last decades of the century, choreographers started to compose minuets wherein Finnish-Swedish minuets were given prominence. The latter part of the chapter will examine the role and significance of these minuet constructions or compositions within the Finnish folk-dance movement.

Börje Wallin and the Reconstruction of the

Swedish Minuet

At the end of the nineteenth century, the older social dances—such as the polska and the minuet—gradually disappeared from the dance floor. The repertoire of social dancers started to change as new dances from America gained popularity in Sweden. Simultaneously, a new dance movement emerged through the establishment of folk-dance groups focused on performance. The repertoire of these groups consisted of new dances created in a folkloristic style choreographed directly for stage performances, and, to a certain amount, older social dances performed in a standardized style. Gradually, these dances were considered to be Swedish ‘folk dances’.2

In the middle of the twentieth century, a few folk dancers started to search for the traditional social dances of the past. The work of these non-scholarly dance researchers constituted the basis for the folk-dance revival in Sweden in the 1970s.3 One of these researchers was Börje Wallin from Helsingborg in the south of Sweden. He grew up as a dancer in a folk-dance group founded by his father. Wallin regularly went to Denmark to dance, visiting Danish folk-dance groups at social dance events, and there he noticed the difference between the Danish and the Swedish folk-dances. According to him, the Danish ones made more sense as traditional social dances. Their structure had more repetitive elements, which made these dances easier to learn and thus more suited to the social dance situation.4

Fig. 18.1 Börje Wallin. © HBG-BILD.

Realizing that a great many of the dances performed by his folk-dance group had never been a part of a traditional vernacular dance repertoire, Wallin started to search for the older social dances from southern Sweden. He interviewed and filmed older people and searched for information in archives and literature.5 Some experienced dancers and musicians interested in dance research regularly visited his home, and there they discussed his work, tried out the dances, and searched for even more source material. They recovered some dances from accounts of living persons, while others were revived from literature and archival material, including written dance descriptions, comments, or narratives about dance events and descriptive sketches. Wallin continued this work for the rest of his life and disseminated his research results to dancers through dance courses and other dance events. Today, these dances are again a part of the thriving folk-dance movement.

The Minuet and the Reconstruction Process

During the seventeenth century, the minuet spread in Europe, and just as in Finland and Denmark, the minuet was not only danced by the upper classes in Sweden but also by the lower classes. Unlike in Finland and Denmark, however, there are no film recordings of the minuet in Sweden, only a few written descriptions. There are, however, strong indications that the minuet had been a popular dance. It was often mentioned in memoirs, letters, poetry, and documents about a particular district’s weddings or local traditions. There are also testimonies of the minuet in archives.6 Another indication is the frequency of minuet melodies in the handwritten tune books of folk musicians. Until the end of the eighteenth century, the minuet used to be a popular melody type. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the number of known melodies drastically decreased—at the same time that the waltz was introduced and quickly gained popularity.7 In a newspaper article about dancing in the south of Sweden in 1810, it is stated that the most popular dances were the slängpolska, the waltz, and the minuet.8 It seems that the minuet disappeared at the end of the nineteenth century. However, in archive questionnaires from the 1930s and 1940s about dance traditions, many respondents still remembered the minuet being danced.9

In his search for the social dances of the past, Wallin found some minuet descriptions from southern Sweden. Assisted by musicians who already knew local minuet melodies, he started to reconstruct the dance in the 1970s. His primary sources were the archival material of Nils Månsson Mandelgren, a Swedish ethnologist, and some notes from Nils Persson from Vallkärra.10

The method Wallin used for reconstructing the minuet was as follows: to read the descriptions closely, to question and discuss what each informant really meant by his or her words, and then to practice the dance repeatedly for a long time—until the music and the described moves made sense together. Then he would repeat the process, reading and discussing the material and dancing again. Wallin found that the way the minuet was described had similarities with the minuets in Denmark and Finland. Here is one example of the minuet descriptions he used:

Both turned around. They retook each other’s hands, briefly, they let go again, after that figure, each in the opposite direction or forwards or further apart from each other. The figure was serious, slow tempo, no jumps, the feet were moved close to the floor. […] After that figure, they retook each other’s hands—let them go again, turning separately again.11

Taken out of its context, this description may seem confusing. But in comparison with the Danish and Finnish minuets Wallin had been used to dancing, it made sense.

The minuet Wallin reconstructed consists of an opening figure followed by two motifs: a figuré and a change of place.12 He interpreted one of the Swedish minuet descriptions as being a couple dance.13 He also combined the minuet with slängpolska since he found notes about slängpolska being danced in connection with the minuet.14 In full, the Wallin minuet is performed like this:

The dancers start with slängpolska turning, followed by an opening minuet figure. After this, the dancers vary between the two motifs—figuré and change of place—until the music stops.

II: The slängpolska (Music: slängpolska)

The dancers dance a slängpolska.

As mentioned in Chapter 2 of this book, the minuet had many different names. In Skåne one finds the terminology möllevitt and möllavillan. Wallin chose to call his reconstructed minuet möllevitt instead of menuett to point at the variety of dance names in earlier centuries.

The minuet of Börje Wallin has been taught in courses and workshops since the 1980s, and it has spread across Sweden. Whether the dance is similar to the minuet of the past or not, one may never know. Wallin handled his source material accurately, but he his primary concern was the dance feeling comfortable and pleasant to dance, wanting to bring it back to the present-day dance floors.15

The Swedish Minuet Today

After an interlude of almost one hundred years, the minuet is being danced again: not in a rural context anymore, but by the Swedish folk dancers of today. However, it is again danced as a part of the same dance repertoire as in the early nineteenth century, with, for example, the waltz and slängpolska—as mentioned in the quote from the newspaper article about the most popular dances in 1810. The minuet has become a popular dance in both participatory and performative settings. Today, the minuet is taught at workshops, courses, and in different forms of folk-dance education, for example, at the Stockholm University of the Arts, where it has a strong position in the dance repertoire of the folk-dance programme.

As a social dance, the minuet is mostly danced in the south of Sweden. In addition, Wallin’s daughter Karin Wallin, who often plays minuet at dance events, claims that there is almost always at least one or two couples dancing the minuet no matter where in Sweden she happens to be playing.16 As a staged folk dance, the minuet has become a popular dance, both in folk-dance groups and independent folk dancers performing folk dances.

Fig. 18.2 Anton Schneider and Petra Eriksson have worked diligently to develop the Börje Wallin minuet for stage performances. Film photographer: Henrik Peel. © Henrik Peel.

Just as the style of other Swedish folk dances has changed through the revival process, the reconstructed minuet has also partly changed over the last twenty years, being influenced by different dance teachers and performing folk dancers. Some dancers have developed ways of varying the minuet step, but the most evident change is to movements of the body, particularly, the arms and legs. Wallin had a relatively moderate dance style, influenced by notes in the source material and the minuet style he had seen in Denmark. Nowadays, the minuet is danced in varying styles, including Wallin’s.

The Minuet in Finnish Youth Associations’

Folk Dance Groups

The minuet is a popular dance among Finnish folk dancers today, but it has not had an equal status all the time and everywhere in the country. The field of Finnish folk dance is dispersed, comprised of several associations whose backgrounds differ significantly. Most importantly, folk dancing associations are organized according to the language, that is, Finnish and Swedish. Moreover, nowadays, most Finnish-speaking folk dancers belong to three organizations, of which only one is exclusively a folk-dance organization, whereas the two others have other activities.17 Finnish Youth Associations is one of the latter type. Nevertheless, it counts the largest number of folk dancers among its members in Finland. It also arranges the only regular folk dance festival in the Nordic countries, Pispalan Sottiisi (Pispala Schottische).18

Youth associations are local societies that are united under a national umbrella organization called Finnish Youth Associations. The first Finnish youth association was founded in 1881. Initially, the purpose of these associations was to educate young people in the countryside, to raise ‘good people and proper citizens’ according to their motto.19 During the first decades, social dancing was considered harmful, and the associations tried to find other activities that could replace it among the youth. First, they promoted singing games in their events and later also folk dances.20 Gradually, folk dance became one of the most popular activities in many of these associations, together with theatre, music, and sports.

The first folk-dance groups within the youth associations appeared at the turn of the twentieth century, but it was not until in the 1930s that the inclusion of these groups became commonplace in many parts of the country.21 In youth associations, folk dances were initially used for educational and civilizing purposes, and although their activities had a strong nationalist character, the preservation of a national folk-dance repertoire did not belong to its primary activities. Folk dance was seen primarily as a form of performance, similar to theatre, which led to the development of staged folk-dance arrangements. As such, the youth associations have not collected folk dances (though some of its members have done so independently), and it has published folk-dance books only occasionally.

As early as in the 1940s, the youth associations displayed a tendency towards creating stage folk dances that many claimed did not belong in the published (and accepted) folk-dance canon and should not be promoted. During this time, one of the most prominent folk-dance instructors in the youth associations, Ms. Helvi Jukarainen, composed her first folk-dance youth choreographies, for which she was strongly criticized.22 Despite this, Jukarainen continued her work after the Second World War until the 1980s. And because she was employed by youth associations, first by the national central organization and later by a regional organization, her influence was significant among youth associations’ folk-dance groups.23

Minuet as a Part of the Repertoire

The minuet as a folk dance is associated with Swedish-speaking Finland. On the contrary, minuets were very uncommon among Finnish-speaking folk dancers until the late twentieth century, when their popularity started to increase rapidly. Like other folk-dance organizations, the Finnish Youth Association publishes an annual folk-dance performance; they have been doing this since the 1940s, and it still happens today.

The first time a minuet appeared in the yearly dance programme was in 1969. The Minuet from Oravais, a version performed in the musical drama ‘Ostrobothnian Peasant Wedding’ from 1906 and later published in several Finnish-Swedish folk-dance books, was added to the performance program. Ms. Sirkka Viitanen, the Finnish Youth Association’s cultural secretary, translated the instructions from Swedish into Finnish. The same minuet was also a part of the folk-dance routine celebrating the organization’s centennial twelve years later, in 1981. In addition to this particular minuet, only instructions of the Minuet from Tjöck were published in an annual program of the youth associations before the 1980s: this took place in 1972 and, again, was made possible by Viitanen’s translation.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, several other minuets, including those from Nagu and Vörå, were translated into Finnish and incorporated into the repertoire of the youth associations’ folk-dance groups. Moreover, these minuets were not merely introduced in the annual programs. The Finnish Youth Association arranged annually international folk-dance courses, which were extremely popular at that time, and Finnish-Swedish folk-dance instructors were invited to teach various dances, including minuets. Consequently, minuets became an essential part of many groups’ repertoire.

Shortly after Finnish-Swedish minuets began to be introduced in youth associations to a more considerable extent, folk-dance instructors also began to compose new minuet choreographies which all followed a similar format. This can best be traced by examining programs of a folk-dance choreography contest, which was arranged as a part of the biannual Pispala Schottische festival. The first contest was organized as part of the first festival in 1970. Very little information has been saved about the competitions during the 1970s, but we do know that these events did not have a stable organization at that time and the themes could differ from year to year.24 Additionally, at several festivals, no contest was arranged at all. However, since 1984, the competition has followed a somewhat consistent format excluding 1990 when the format differed from other competitions and the festivals occurring from 2003 to 2009 when the gatherings were arranged at the Pispala Schottische biannual autumn festival Tanssimania (Dance Mania).25

Table 18.1: Minuets at Pispala Schottische folk-dance Choreography Contest 1984–2009

|

Year |

Name in Finnish |

Name in English |

|

1984 |

||

|

1988 |

||

|

1990 |

||

|

1992 |

||

|

2003 |

Minuee |

|

|

2005 |

Viiden askeleen menuetti ja valssi |

|

|

2007 |

Jäähyväismenuetti |

|

|

2009 |

Iltatunnelmia (Menuetti) ja Jälkipolska |

From the documents available since 1984, we can see that there were dances called a minuet in most of these contests (see Table 18.1 above). Considering that it was not until at the beginning of the 1980s that minuets even became common among the youth associations’ folk-dance groups, it is remarkable that several new minuet choreographies were composed regularly throughout the decade and beyond. In most cases, the minuet was followed by a polska, which is still typical of Finnish-Swedish minuets danced by Finnish folk-dance groups today, and in only three instances the minuet was a standalone piece or followed by a waltz.

Kuortane Minuet and Polska

The best-known folk-dance teacher in youth associations during the last decades of the twentieth century was Mr. Antti Savilampi, who composed two of the minuets mentioned in Table 18.1: Kuortane Minuet and Evening Atmosphere, both of which were followed by a polska. Kuortane Minuet, from 1992, has been danced regularly by several folk-dance groups since its inception. We shall have a closer look at its background and structure in the following analysis.26

Fig. 18.3 Folk-dance group Kiperä premiering Kuortane Minuet at Savoy Theatre, Helsinki, 1992. Photograph by Petri Mulari. © Petri Mulari.

The melody of Kuortane Minuet was composed in the late 1980s by Markku Lepistö, while he was a student at the department of folk music of Sibelius Academy (the music university of Finland). Professor Heikki Laitinen explained that he asked Lepistö to compose a minuet and polska honouring Lepistö’s home region, Kuortane, as an assignment for a musical composition course.27 Later, Lepistö collaborated with Savilampi in the late 80s and early 90s, and one of their joint artistic projects was Kuortane Minuet and Polska, which Savilampi choreographed in 1992.28 Savilampi worked as a physical education instructor of The Finnish Youth Association until 1993, and folk dance was his primary area of expertise. Therefore, during his partnership with Lepistö, he was familiar with the minuets published in annual programs and others that he became acquainted with through his contacts with Finnish-Swedish folk dancers. His participation in the Kuortane Minuet project shows influences from several Finnish-Swedish minuets, especially those from Tjöck and Lappfjärd: the basic step, basic figure, hand figure, as well as the introduction and ending have similar features as in these minuets, although they have also been modified and altered in many ways. The dance takes place in a typical longways formation, with ladies and gentlemen in opposite lines, each dancer facing his or her partner. This formation is changed in the middle of the dance and at the end of the performance the original formation is restored.

The basic step of Kuortane Minuet consists of steps during two 3/4 bars as in most minuets: a step with the right foot (1), a step with the left foot (3), a step with the right foot (4), and a step with left foot (5) or a chassé step beginning with the left foot (5–6). The latter option including a chassé step during the two last counts of the minuet step is similar to a minuet basic step found in Lappjärd, published in 1984.29 In addition, the dance contains balancé steps sideways, which resemble similar steps during the middle part of the minuet from Tjöck, as well as variations of the basic step.

The basic figure of the dance consists of twelve bars, which is typical of Danish and but not Finnish-Swedish minuets (Table 18.2). The figure starts in longways formation.

Table 18.2: The basic figure of Kuortane minuet

The overall form of the dance is presented in the Table 18.3.

Table 18.3: The form of Kuortane minuet

Savilampi’s Kuortane Minuet is a combination of influences from published Finnish-Swedish minuets and his original artistic contribution. The choreography follows the music’s main structure, but the twelve-bar basic figure differs from the eight-bar phrases of the melody. Although the dance contains the most salient features of Finnish-Swedish minuets, its distinctive stage-dance character is seen, for example, in its strict form, stylized movements, and raised hands, all of which are unfamiliar in social forms of minuets.

Concluding Remarks

Under the influences of the living traditions in Denmark and Swedish-speaking Finland, Swedish and Finnish folk dancers created new minuet practices during the last decades of the twentieth century. What connected them was the appreciation of the dance form and the desire to reinstate it in dancers’ active repertoires. However, solutions for revitalizing the minuet clearly differed in these countries. It is thus possible to see two different methods for integrating the minuet into national folk-dance fields.

The contemporary Swedish minuet is an example of how a social dance of the past, which was transmitted only by archives and literature, was reconstructed in the Swedish folk-dance revival of the 1970s. It is now, once again, a part of the vivid dance scene. Quite the opposite, new minuet choreographies in the Finnish Youth Association are made for stage purposes only, and the choreographies are popular in folk-dance performances. In addition, the Swedish minuet is only occasionally seen at social folk-dance events in Finland, usually when there is Swedish polska dancing involved.

References

Archival material

Folklife Archives (LUF), Lund University

Mandelgren’s collection

Pispala Schottische Archive, Tampere, Finland

Programs of the Pispala Schottische choreography contest 1984, 1986, 1988, 1990, 1992, 1994, 1996, 2003, 2005, 2007 and 2009

Video of the Pispala Schottische choreography contest 1992

Private archives

Correspondence between Anni Collan and Helvi Jukarainen 1946–1947

Svenskt visarkiv, Stockholm

SVAA20160515BW001

Swedish Institute for Language and Folklore (ULMA), Uppsala, Frågekort 39 Danser

Secondary sources

Andersson, Göran, ‘Philochoros—grunden till den svenska folkdansrörelsen’, in Norden i Dans: Folk, Fag, Forskning, ed. by Egil Bakka and Gunnel Biskop (Oslo: Novus, 2007), pp. 309–18

Biskop, Gunnel, Menuetten — älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden — särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder — under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015), pp. 99–108

Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 70 Finlandssvenska folkdanser. Instruktionshäfte 4 (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 1984)

Gustafsson, Magnus, Polskans historia: en studie i melodityper och motivformer med utgångspunkt i Petter Dufvas notbok (Lund: Lunds universitet, 2016)

Helmersson, Linnea, ‘Börje Wallin’, in Eldsjälarna och dansarvet: om forskning och arbetet med att levandegöra äldre dansformer, ed. by Linnea Helmersson (Rättvik: Folkmusikens hus, 2012), pp. 314–15

―, ‘Inledning’, in Eldsjälarna och dansarvet: om forskning och arbetet med att levandegöra äldre dansformer ed. by Linnea Helmersson (Rättvik: Folkmusikens hus, 2012), pp. 8–19

Hoppu, Petri, ‘Folkdansföreningar i det finska Finland’, in Norden i Dans: Folk—Fag—Forskning, ed. by Egil Bakka and Gunnel Biskop (Oslo: Novus, 2007), pp. 478–80

―, ‘National Dances and Popular Education—The Formation of Folk Dance Canons in Norden’, in Dance and the Formation of Norden: Emergences and Struggles ed. by Karen Vedel (Trondheim: Tapir, 2011), pp. 27–57

Mandelgren, Nils Månsson, Julen hos allmogen i kullen i Skåne på 1820-Talet, [Faks.-uppl.] (Lund: Mandelgrenska samlingen, 1984/1882)

Numminen, Jaakko, Yhteisön voima. Nuorisoseuraliikkeen historia 1. Synty ja kasvu (Helsinki: Suomen Nuorisoseurat, 2011)

―, Yhteisön voima. Nuorisoseuraliikkeen historia 3. Seuratoiminta (Helsinki: Suomen Nuorisoseurat, 2011)

—,Yhteisön voima. Nuorisoseuraliikkeen historia 5. Kansanliike elää (Helsinki: Suomen Nuorisoseurat, 2011)

Wallin, Börje, Gamla Dansar i Skåne, Polskor (Helsingborg: Sonja and Börje Wallin, 1992), [Booklet and DVD]

Weman, Adéle (alias Parus Ater), ‘En folklivsforskare’, Föreningen Brage, Årsskrift 2 (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1908), pp. 23–29

1 Börje Wallin was the grandfather of Anna Björk, one of the authors of this chapter.

2 Göran Andersson, ‘Philochoros—grunden till den Svenska folkdansrörelsen’, in Norden i dans: folk, fag, forskning, ed. by Egil Bakka and Gunnel Biskop (Oslo: Novus, 2007), pp. 309–18; Linnea Helmersson, ‘Inledning’, in Eldsjälarna och Dansarvet: Om Forskning och Arbetet Med att Levandegöra Äldre Dansformer, ed. by Linnea Helmersson (Rättvik: Folkmusikens hus, 2012), pp. 8–19.

3 Helmersson, ‘Inledning’.

4 Svenskt visarkiv SVAA20160515BW001. Most of the facts about Börje Wallin in this text originated from an interview with Wallin’s family members who were a part of his research.

5 Linnea Helmersson, ‘Börje Wallin’, in Eldsjälarna och Dansarvet: Om Forskning och Arbetet Med att Levandegöra Äldre Dansformer, ed. by Linnea Helmersson (Rättvik: Folkmusikens hus, 2012), pp. 314–15.

6 Gunnel Biskop, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015), pp. 99–108.

7 Magnus Gustafsson, Polskans historia: en studie i melodityper och motivformer med utgångspunkt i Petter Dufvas notbok (Lund: Lunds universitet, 2016), pp. 323–40.

8 Folklivsarkivet, Lund. Mandelgren 1882, and Mandelgrenska samlingen, 3:12:7. ‘Slängpolska’ is a Swedish couple dance with origins in the oldest version of couple dance in Sweden, which is evident because the part of the performance where dancers spin around happens while they remain in place on the dance floor rather than while they move around the dance floor like the waltz. Since the folk-dance revival, slängpolska has again become a popular dance.

9 Institutet för språk och folkminnen, Dialekt- och folkminnesarkivet i Uppsala (f.d. ULMA), Frågekort 39 Danser.

10 Mandelgren’s collection is situated at the Folklife Archives of Lund University. However, the question concerning Nils Persson’s notes is more complicated. The carpenter Nils Persson was born in 1865 in Vallkärra, close to Lund in southern Sweden. Wallin found notes about Persson’s mother dancing the minuet. At the Nordic Museum in Stockholm, there are notes about dancing made by Persson, but none contain the exact quotation that Wallin claims to have found. A former archivist at the ‘Dialekt- och ortsnamnsarkivet’ in Lund also claims to have had contact with Nils Persson about dancing. To this day, the quotation Wallin cited in his reconstruction has not been found in any archive.

11 Mandelgren’s collection. Folklife Archives, Lund. [Author’s translation.]

12 A ‘figuré’ is an expression used within Swedish folk dance referring to dance figures where two people dance together, facing each other but without embracing or touching each other. See Börje Wallin, Gamla Dansar i Skåne, Polskor (Helsingborg: Sonja and Börje Wallin, 1992), [Booklet + DVD].

13 For example, one source said: ‘Any number of couples danced at once, but each couple alone by itself.’ Mandelgren’s collection. Folklife Archives, Lund. [Author’s translation.]

14 Mandelgren’s collection. Folklife Archives, Lund.

15 Svenskt visarkiv. SVAA20160515BW001

16 Karin Wallin is a well-established folk musician who was the leading musician in Börje Wallin’s research projects and dance courses from the middle of the 1970s and onwards.

17 Petri Hoppu, ‘Folkdansföreningar i det finska Finland’, in Norden i Dans: Folk—Fag—Forskning, ed. by Egil Bakka and Gunnel Biskop (Oslo: Novus, 2007), pp. 478–80.

18 Jaakko Numminen, Yhteisön voima. Nuorisoseuraliikkeen historia 5. Kansanliike elää (Helsinki: Suomen Nuorisoseurat, 2011), p. 542, pp. 585–91.

19 Jaakko Numminen, Yhteisön voima. Nuorisoseuraliikkeen historia 1. Synty ja kasvu (Helsinki: Suomen Nuorisoseurat, 2011), pp. 89–90, p. 148.

20 Jaakko Numminen, Yhteisön Voima. Nuorisoseuraliikkeen Historia 3. Seuratoiminta (Helsinki: Suomen Nuorisoseurat, 2011), pp. 406–7.

21 Ibid., pp. 545–49. The first youth association with folk dance was Kimito ungdomsförening in Southwestern Finland, but it belonged to the Swedish-speaking youth organization which is separate from the Finnish Youth Associations; Adéle Weman (alias Parus Ater), ‘En folklivsforskare’, Föreningen Brage, Årsskrift 2 (Helsingfors: Föreningen Brage, 1908), pp. 23–29.

22 Correspondence between Jukarainen and Ms. Anni Collan, one of the early pioneers, publishers, and folk-dance collectors in Finland, reveals that Jukarainen’s activities were regarded as totally inappropriate. Collan stated that Jukarainen’s choreographies would destroy the original Finnish folk dance. (Correspondence between Anni Collan and Helvi Jukarainen 1947–1948. Private archive.) It must be stated that even the Finnish folk-dance canon—the published dances—contained choreographies or arranged folk dances (see Hoppu, ‘National Dances’).

23 Numminen, Yhteisön Voima, 5, pp. 594–95.

24 Ibid., pp. 591–92.

25 Programs of the Pispala Schottische choreography contest 1984, 1986, 1988, 1990, 1992, 1994, 1996, 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2009. Pispala Schottische Archive, Tampere, Finland.

26 The analysis of Kuortane Minuet is based on the video recording at Pispala Schottische choreography contest in 1992. The video is found in Pispala Schottische Archive, Tampere, Finland.

27 Heikki Laitinen, November 28, 2016, personal communication.

28 Antti Savilampi, July 17, 2018, personal communication.

29 Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 70 finlandssvenska folkdanser. Instruktionshäfte 4 (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 1984).