DEFINING AND SITUATING THE MINUET IN HISTORY AND RESEARCH

The first part of this book defines and situates the minuet as a dance and a musical form. Its chapters discuss the role of the minuet in European society and culture since the seventeenth century as well as its research and historiography.

2. Situating the Minuet

©2024 Egil Bakka, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.02

The starting point for my investigation is the name of the dance and whether it corresponds to one or more basic movement structures. This chapter then examines the distribution of the dance in time and space, comparing contentious ideas about its origins and ascertaining how political and social references have shaped interpretations of the dance. For these purposes, it is necessary to establish the minuet in its European historical context, including the European research landscape, despite the book’s concentration on the forms and roles of the dance in the Nordic countries.

Name and Distribution

The name ‘minuet’ occurs in various forms in different languages. Menuet (French) is the point of departure; slight variations of this word are found in many European languages: the German Menuett(e), the Swedish and Norwegian menuett, the Danish menuet, the Spanish minué, the Italian minuetto, and the Russian менуэт. Additionally, there are dialect(al) versions of the word, such as the Danish monnevet, møllevit, mollevit; the Swedish minuett, möllevitt; Finnish minetti, minuutti, minuee (Finnish); and the Norwegian mellevit.1 Some forms refer to the mix of the minuet and other dances, such as the Spanish minué afandango, a minuet partly composed of allemande.2 We also find the term ‘Volks-Menuet’ [folk minuet] which, at least in the case referred to, is a comparison between the style of the Russian national dance to that of the French court minuet. It is not proposing that the minuet had become a folk dance in Russia.3 In the same spirit, a French source characterises the Farandole as ‘this popular minuet’, not to hint that the dances are related but rather to imply that the two dances are similar in function and status.4

Surprisingly, the minuet does not seem to have been fully taken up into folk culture anywhere in Europe except in the Nordic countries, where it has survived as continued practice. It has not been possible to find definitive sources that permit any other interpretation. Proving a negative is difficult, but the following examples do suggest that the minuet was not part of folk culture in the rest of Europe.

Richard Wolfram, an Austrian dance ethnologist, for instance, was one of the most knowledgeable researchers of Austrian folk dance, and he could find little evidence of the minuet in this context. Comparing the history of Austrian and northern European folk dance, Wolfram concluded:

The ‘folk’ do take over [material from the upper classes], but not without making selections. In this way, the minuet remained almost without impact on Austrian folk dance even if the educated classes mastered it for a long period. The minuet was only played as table music at weddings and similar events in rural environments. Its courtly form could not find any danced expression here.5

A similar idea is offered in a long and well-informed article from 1865 that criticises staging practices of Mozart opera Don Juan. Discussing the historicity of staging practices, its anonymous author asks why Mozart and his libretto writer use the minuet in an opera purportedly set in Spain, since the story involves a peasant couple. The implication is that Spanish peasants do not dance the minuet. Although the statement is quite general and absolute, it points in the same direction as the previous quotation.6

|

Video 2.1 The minuet in a 2001 Zurich production of W. A. Mozart, Don Giovanni, complete opera with English subtitles. Uploaded by Pluterro, 5 November 2017. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/2a74d4a1. See timecode 01:26:59. |

The German author and philosopher Karl Heinrich Heydenreich (1764–1801) wrote the article ‘Über Tanz und Bälle’ [Dance and Balls] in 1798. In it, he portrays the minuet as the most valuable dance at upper-class balls and states bluntly that the dances of the lower classes are just a raw mixture of hopping, jumping and circling. Heydenreich does not suggest that the lower classes copy the upper classes.7

From these sources, we conclude, like the Swedish musicologist Jan Ling who writes extensively about dance in his European History of Folk Music (1997), that there is little evidence of a folk minuet outside of the Nordic countries.8 It is nevertheless important to review some folk dances outside of the Nordic countries because some of these are called the minuet and we need to check to what degree they are similar to the main forms of the minuet. Julia Sutton refers to a German minuet: the ‘Treskowitzer Menuett’.9 This is danced to music in 3/4 time like the minuet in which we are interested—but has a square formation, walking steps, and ends with a waltz. As the following video recording from the Dancilla website shows, this ‘Treskowitzer Menuett’ does not share the typical movement patterns of the minuet that will be presented in detail in later chapters.10

|

Video 2.2 ‘The Treskowitzer Menuett’, Dancilla website (2020), https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/ead1d1a8. See both videos on this page. |

Dancilla includes other videos showing dances that are referred to as minuets but also do not share its characteristics. Some seem to be folk-dance style choreographies set to pieces of classical music.

In the Czech Republic, a folk dance called Minet has been assumed to be a minuet version due to its name. A publication entitled Lidové Tance z Čech, Moravy a Slezska [Folk Dances from Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia] is an ambitious series of ten videos, each accompanied by a separate booklet. The series presents the folk dances of the Czech Republic danced by folk-dance groups all over the county.11 In this collection, we also find several names that are similar to the minuet:

- Minet—corava c Hlineca Vysokomytska a Crudimska, vol. III, piece E 11 3.

- This is a couple dance danced on a circular path to waltz-like music.

- Minet ze Stráznice u Melnica, vol. IV, piece D 11.

- Minet z C̆áslavska, vol. IV, piece D 17.

- The D 11 minet opens with men and women facing each other in two lines, which is one of the most popular formations in minuet, but then continues as a waltz couple dance. The D 17 is also more of a waltz couple dance.

- Menuetto (minet) z zapadni Moravi a cheskomoravskeho, vol. V.

This dance, with the name Menuetto, has a line formation and uses some steps on the place that vaguely resemble features of the minuet.

The Minet dance form, which is the most similar to what we would now define as ‘the minuet’, was collected 1912–13 by Fritz Kubiena in Kuhländchen, a region in the eastern part of the present Czech Republic that was inhabited at the time by a German population. Kubiena gives a precise description of the dance and accompanying music in the folk-dance collection he published in 1920.12 As can be seen in the following video, the dance does not have minuet steps or a full minuet form, but similarities in music and style suggest that the Minet may imitate minuet patterns:

|

Video 2.3 Das Kuhländler Mineth. Folk dancers safeguarding heritage from Kuhländchen perform eleven dances. Uploaded by Wir Sudetendeutschen, 30 April 2020. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/d7079ef1. See the Mineth at timecode 8:24. |

Compared to the minuet as danced by the French court, descriptions of the minuet given by European dancing masters, and those practised by Nordic folk dancers, the Czech Minet(h) dances seen above are not recognisable as minuets. Some seem to be different dances altogether. One or two have features that might have been inspired by the minuet but not much more.

Moving away from European examples, dance theorists Russel and Bourassa claim that, to this day, a form of the minuet is danced in Haiti. This dance, called in Creole the menwat, is as part of a sequence of dances that echoes the order of eighteenth-century balls.13

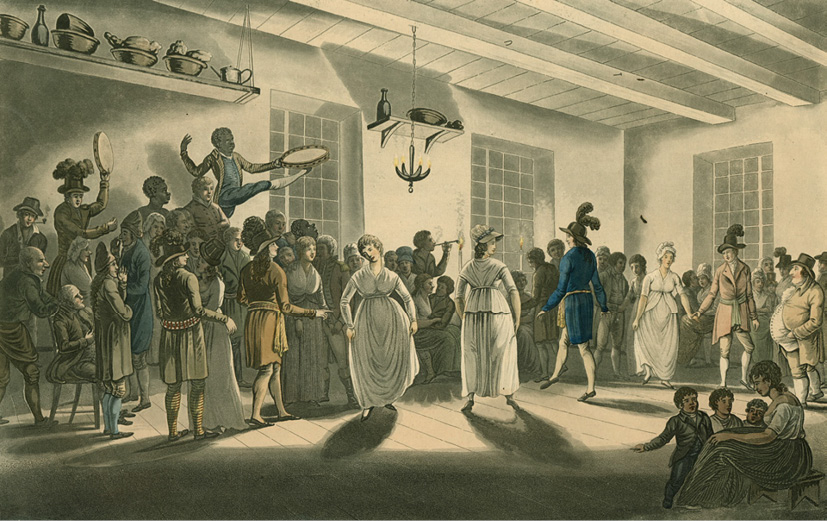

Fig. 2.1 George Henriot’s watercolour Minuets of the Canadians (1807) seems to confirm that the minuet was danced even in Canada. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Minuets_of_the_Canadians_-_TPL.jpg, public domain.

A Definition of the Minuet as Movement and Music Patterns

How can the minuet be characterised as a form? Do the movement patterns labelled ‘minuet’ in its different linguistic variations have a cohesiveness, and can it be defined clearly and consistently? In many discourses, the minuet is a dance. This is logical in the context of traditional social dancing and for the minuet’s realisation within a single community. The minuet functions as one dance in the local repertoire during a specific period, whether this is the menuet ordinaire performed in French court circles or the menuet[t] danced in Nordic urban and rural communities, particularly in Denmark and Finland. In the latter case, there were regional variations and the dance form changed over time as is usual for any dance. Still, the movement patterns and the music of these Nordic minuet forms show a surprisingly strong unity. The choreographed versions of the minuet, particularly in French court circles, do not follow this model. If we want to identify the minuet movements shared by all variations carrying the name, another concept or dance paradigm might help.

- A dance paradigm is a set of fundamental and constitutive conventions for how a specific form of dancing is organised. It is a long-lasting and widespread cluster of conventions which provides the basis for a particular kind of dancing. Some criteria for identifying a dance paradigm could be a new set of conventions for the design and organisation of dancing that is so radically different from what is already in use, that it is perceived as something completely new in the place where it settles.14

- A dance paradigm is stable enough to remain in use over a long time.

- Its conventions are inspirational and fruitful enough to give rise to an extensive dance practice.

A group of characteristics can be used to define which dances belong to the paradigm but no single characteristic is necessary or sufficient to include all dances of the paradigm. This is the principle of polythetic classification.15 An assessment must be made in each case of a dance realisation to determine if it belongs to a specific paradigm. Not all dance forms do.16

To ascertain what is typical of a minuet, it is essential to look at the movement patterns and not base any judgement strictly on the name. The main reason for this is that the choreographed forms that were used in the French court tradition were unlikely to appear unchanged as social dances in subsequent decades. For many later choreographers, it was more important to break the conventional framework in one way or another than to maintain a connection to the older menuet ordinare. Therefore, these choreographies must be assessed by other criteria. We propose defining the minuet as a social dance based on the following conventions:

- the dance can be performed by one couple

- it may group two couples together

- it may group many couples in a line of men and a line of women facing each other

- the dance does not move far away from the place it started, or, at least, it returns to the starting point

- the music is in 3/4 time

- the step pattern spans two bars

- the partners move both toward and away from each other

- the partners change places and change back again

- the partners can use one same-hand fastening17

Some Points of View on Historiography

Histories of dance in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries rely heavily on excerpts from a large variety of written sources that describe dancing or dances at that time. Such source material is not easy to find. If the scholar cannot access specialised archives, he or she must depend on materials located by earlier researchers and even adopt their interpretations. These repetitions tend to lend the interpretations an air of reliability that is seldom questioned. Without revisiting primary sources, or not doing so in a systematic way, dance historians have tended to present fragmented narratives. Dance groups interested in historical re-enactments, for example, have used the dance notations and descriptions from earlier centuries’ dancing masters. However, this work rarely displays the rigour of advanced research. The Dean of Research in French Dance Ethnology, Jean-Michel Guilcher, is an exception. He wrote an exemplary study of the eighteenth-century French contredanse, combining detailed analysis of its forms with an impressive contextualisation of the social and political life of the era.18

We argue here that this kind of critical approach is needed to achieve progress in dance history. Another significant point is that dance history has tended to be written about one genre at a time. Some historians specialise in the history of theatrical dance; others write about the history of the social dances of the upper class. Relatively few write about the history of folk dances or the dancing practised by the lower classes. Yet these different classes and different kinds of dancing existed simultaneously throughout history. This book will reveal that although there were socioeconomic divisions and specialisms, people of various groups were part of the same world and did interact. We argue that dance history should take such interaction into account to create fuller pictures of historical periods.

Fig. 2.2 Marten van Cleve, A village celebrating the kermesse of Saint Sebastian in the lower right corner there are groups of upper-class people celebrating side to side with the peasants (between 1547 and 1581), oil on panel. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marten_van_Cleve_-_A_village_celebrating_the_kermesse_of_Saint_Sebastian,_with_an_outdoor_wedding_feast_with_guests_bringing_gifts.jpg, public domain.

Finally, it is crucial to understand dancing and dances as belonging to paradigms, each of which relies on specific organizational conventions. Seeing dances as parts of certain paradigms yields a safer hypothesis about their genesis and development than drawing comparisons between isolated traits of dances not studied in context. For instance, a specific way of holding hands needs to be recognised as part of a paradigm. One such similar feature between two individual dances does not tell us much about how or whether they are related.

Dances are movement designs, which are often based on stunning relationships between strict, long-lasting, deep structures that remain stable through time and space. They usually appear with superficial variations in what are often called dance dialects but maintain the basic deep structure. Dance history needs to be understood within the context of social class, social functions, music, dress, gender roles and conventions; however, dance history also needs to include the history of the dance. The movement structures are the substance of the dance and the dances are not only inventions that reflect a cultural moment but also long-lasting patterns that connect and explain the present through the past. The following is an attempt to view the minuet from the latter perspective, where dance form and the context of dancing are merged in the analytical process. This is also the methodological point of departure for the following brief discussion about the genesis of the minuet.

The Genesis of the Minuet

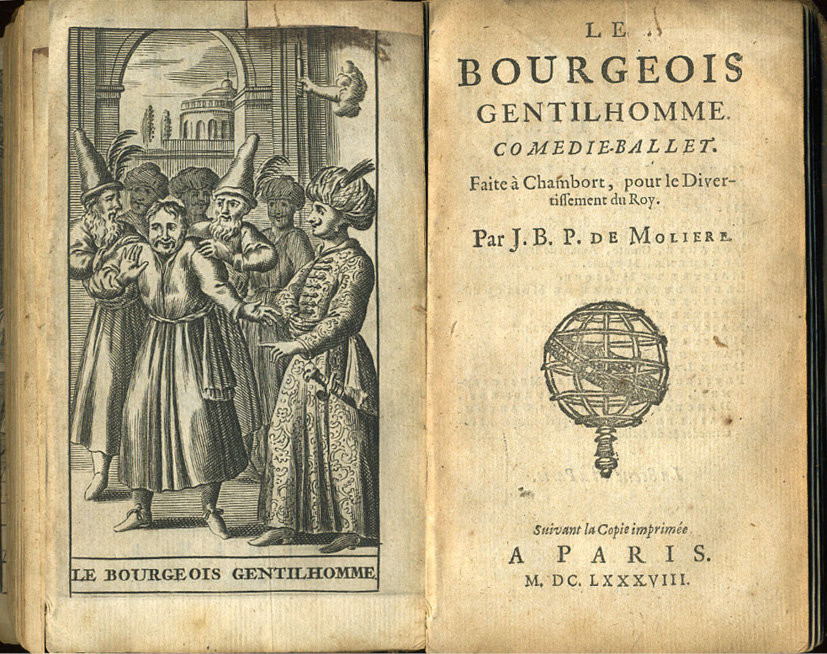

Very little evidence describing the origins of the minuet is available. However, several sources do cite a score from 1664 as the first appearance of the minuet. A document containing information about a Comédie-ballet that premiered in that year mentions the dance. Later, the advisor of Louis XIV Michel de Pure (1620–80), published a book on dance and court ballets in 1668 confirming that the menuet was relatively new at that time: ‘As for the quite new inventions, these Bourrées, these Minuets, they are only disguised repetitions of dancing master’s toys and honest and spiritual pranks to catch fools who have the means to pay’.19

A brief contention about ‘where the minuet came from’ is repeated in almost all, even the shortest, pieces written about the dance. The core of the argument is that the minuet comes from Poitou and further that it is a derivation or adaptation of one of the region’s traditional dances: the Branle de Poitou. One such text described the minuet, for instance, as an

Old French dance, triple time, which appears in the seventeenth century and seems to be derived from of a ‘branle to lead’ Poitevin. [The French composer Jean-Henry] D’Anglebert [1629–1691] named actually [one of his works] the Menuet of Poitou in his harpsichord pieces, which offer a primitive type thereof.20

There is also a Branle de Poitou described in the famous musical study Orchesographie by Thoinot Arbeau (1589).21 The French philosopher and composer Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) repeated the idea of Poitou as the origin of the minuet, crediting the French cleric Sebastian de Brossard (1655–1730) with the notion but disagreeing with him about the character of the minuet.22 Brossard, however, did not refer to the Branle at all, only to Poitou; he also described another dance, the Passe-pied, as a ‘rapid minuet’ and yet another, the Sarabande, as a ‘severe and slow minuet’.23 Did Brossard consider the minuet a general term for any type of couple dance?

Another more probable explanation for the references of Rousseau and Brossard to the ancient region of Poitou is that in the early seventeenth century, Poitou was a centre for the making of woodwind instruments, and Hautbois de Poitou was the name of a specific oboe-like instrument.24 Throughout the seventeenth century, the French court had a musical ensemble by the name ‘Hautbois et Musettes de Poitou’. The ensemble probably derived its name from these instruments since it is not likely that it was populated with musicians from Poitou, over this long period or mainly played music from the region. No other regions are mentioned in this context, yet the name Poitou seems to have had a strong presence at court.25

Fig. 2.3 Frontispiece and title page from Moliere, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1688). Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BourgeoisGentilhomme1688.jpg, public domain.

Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, a comédie-ballet first performed on 14 October 1670 before the court of Louis XIV, bore out this suggestion containing the following stage directions: ‘Six other French come after, dressed gallantly a la Poitevine accompanied by eight flutes and hautbois and dance minuets’.26 Its music was composed by Jean-Baptiste Lully and its choreography was made by Pierre Beauchamp. Therefore, we can surmise that Beauchamp may have introduced the minuet at court for the first time through this work but the name minuet and some musical and choreographical elements could be older. References to Poitou, then, probably appear in the ballet because within this performance, six of the court dancers are dressed as people from Poitou, perhaps to match the name of the music ensemble at the court.

|

Video 2.4 Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully from Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, ‘Menuet pour faire danser Monsieur Jourdain’ [Menuet to make Monsieur Jourdain dance]. Uploaded by Vlavv, 24 December 2010. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/4d73077b |

Reviewing mentions of the French branles in written sources and popular tradition may contribute to our understanding of the genesis of the minuet. There are many tunes and many versions of the dance branle, but it is beyond our scope here to give more than a few examples. Nevertheless, one might suspect that the meter and other characteristics of the music, rather than the dance pattern, is the basis of the claim that links the branle and the minuet. Jean Michel Guilcher found similarities between Arbeau’s sixteenth-century branle types and the material about the contredanse he collected in the mid-twentieth century. He does not, however, suggest any connection to the minuet when he mentions the pattern of the Branle de Poitou.27

|

Video 2.5 Branle des Poitou, from Luther Hochzeit. Uploaded by kaltric, 14 June 2014. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/0ab38173. See the Branle des Poitou at timecode 1:45. |

|

Video 2.6 Branle du Poitou (par Chacegalerie), Les Clouzeaux. Uploaded by Bedame Trad, 18 December 2018. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/86ea3111 |

If we embrace the idea of dance paradigms as widespread and long-lasting organisational structures, a chain dance such as branle and a couple dance such as the minuet would be classified as representatives of very different paradigms. I am suggesting here that Spain, France, and perhaps neighbouring countries had a comprehensive paradigm of couple dances were the partners danced in front of and around each other. In this model, when more couples danced at the same time, they often made a line of men and a line of women. This line formation is one of the characteristics we listed for the minuet but it is also typical of several well-known dances in Spain and France that may be of a similar age. The Jota, a dance in triple time, like the minuet, has several regional variations. The version from Aragon is particularly well known and is shown here:

|

Video 2.7 A jota dance, by the group ‘La Calandria’ for a fiesta in Torre del Compte on 20 August 2011. Uploaded by maxxyvidz, 20 August 2011. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/2dd07cec |

|

Video 2.8 A jota aragonesa dance, by Jorge Elipe and Elena Algora at the national jota contest in Zaragoza, Spain 2013. Uploaded by proseandpoetry, 2 May 2014. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/f0622713 |

The seguidilla is another dance in triple time that was known and popular in Spain in the sixteenth century. Several modern regional dances are considered to be derived from its early versions.28 The Fandango is a well-known triple time dance from Spain; its name was even given to a contradance that was practised in the Nordic countries.29 The French Renaissance court dance Galliard and the traditional dance Le Bourré d’Auvergne are also couple dances in triple time that share some of the characteristics of the minuet described above. There is also a similar dance from the Resian region, though its music is in 5/4.30 There are also duple time versions such as the courante and bolero. Dance historians have not linked these many triple meter couple dances in France, Spain, and Southern Europe which have characteristics in common with minuet. The one most often shared being that the partners dance in front of each other. I suggest that these dances should be seen as part of the same widespread paradigm. Further research would be required to confirm or refute this surmise.

|

Video 2.9 Seguidilla de Huebras dance, by Grupo Folklórico Abuela Santa Ana, from Albacete, La Mancha, Spain. Uploaded by Folk Dances Around the World, 8 September 2011. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/1a152e4c |

|

Video 2.10 Fandango antiguo castellano dance, by folk ensemble Nuestra Señora de los Remedios, from Alcorcon, Madrid, Spain. Uploaded by Folk Dances Around the World, 25 March 2009. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/4f22dfdc |

|

Video 2.11 Gaillarde dance, by historical dance ensemble TIME OF DANCE. Uploaded by AltaCapella, 18 March 2012. YouTube, |

|

Video 2.12 Bourrée 3 temps d’Auvergne dance, by Gregory Dyke and Cynthia Callaou. Uploaded by Tirn0, 19 April 2013. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/34ce1b13 |

|

Video 2.13 Resian dance, by Gruppo Folk Val Resia in Moscow, Russia on 9 November 2015. Uploaded by Gruppo Folk Val Resia, 10 November 2015. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/53faf208 |

Some of these are traceable as early as the seventeenth century. They can be seen as part of the same paradigm within which the minuet may have developed into an acceptable court dance. Let us look closer at the whole paradigm. One feature that French dance teachers may have considered rude is the jumping and the gesticulation with the free leg; another is the twisting of the upper body and the gesticulations of hands. Perhaps this is why the minuets have a port de bras [a way to place the arms] which could be interpreted as a refinement of the livelier hand gestures of popular forms. The minuet shared more structural and formal similarities with these open couple dances than to the branles. However, there is one point of structure that could be used to argue for a relationship between the minuet and the branle. If we start the most common movement pattern of the minuet on the third beat, the resulting step has the structural pattern of the branle simple. I would argue, however, that chain dance forms such as the branle and the couple dances of the Baroque period belong to different dance paradigms. From this perspective, the similarity noted above would be between two individual dances.

As Guilcher observed, there is a lack of extant sources about social dance even as practised in the higher circles in the seventeenth century.31 Consequently, the genesis of the minuet remains in the shadows. It seems likely, however, that the minuet was created by the dancing masters and musicians at the court of Louis XIV based on patterns from a widespread paradigm of couple dances and that its associations with the branle and perhaps also with musicians from Poitou are fictional.

Political and Social Aspects of European History

Let us take a very general and long-range perspective on the significant dance paradigms of the aristocracy in Western and Central Europe over the last five centuries. It seems reasonable to believe that during the Middle Ages, before the time of the dancing masters, the aristocracy primarily used the same dance material as the lower classes. At the very least, the dances may have sprung from the same roots and retained apparent similarities from a distant point of view. Their differentiation would not be so much in the dance forms but the style in which they were performed, as well as in dress, music, etc. During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, the dancing masters would create ballets and masques at many courts. They even brought forth social dances for use at courts and these innovations were markedly different from dances practised by the lower classes. Although they might refer to and take inspiration from the dances of the peasants in rural regions, the dancing masters would codify and adapt them to new ideals and direct similarity would disappear. This may be why these noble dances, as invented or codified at the courts, do not seem to be represented to the same degree as the chain dances and the contradances in traditional dance material throughout Europe. Contradances, first known as country dances, are said to have their roots in the lower classes, but the upper-class variations created by the dancing masters were the dominant ones. This can be seen from the wealth of contra dances in dancing masters’ manuals. Contradances were first published by the sixteenth-century Englishman John Playford and this practice continued through to the early twentieth century. Still, for many reasons, the contra or country dances were not as strictly codified by the courts as the minuet.

Around 1800, the round dances grouped under the name of ‘walzen’ [waltzing] and later ‘walzer’ [waltz], came fully into fashion. These dances emerged from the lower classes and created challenges for dancing masters that the profession until this time had yet to encounter. I have not seen claims or evidence that dancing masters played a central role in bringing waltzing into fashion. Rather, it seems that they took these dances into the courts only after demand for them had grown strong. This puts the round dances in a different relationship to courts and power since they were not created or codified by their servants. These dances slowly entered upper-class culture in ways comparable to class journeys of the nouveau riches. These dances also lacked the structural richness of the contradances and did not lend themselves as easily to new choreographies. When the dancing masters saw they needed to deal with the round dances, they faced the challenge of adapting them to the mechanics and strategies of class distinction.

The Minuet at the French Court

How popular was the minuet at the French court? Louis XIV’s sister-in-law Lieselotte von der Phalz (1652–1722), a German princess who married into the French royal family in 1671, did not like it. Her letters from the beginning of the eighteenth century state that nothing made her more impatient than being made to sit and watch the minuet for three hours. She did not like the French dances at all, and she said that she had a special aversion to the minuet.32 In 1672, immediately after arriving in Paris, she complained that she did not like dancing anymore, partly because the French dances were different from the German ones she knew from home.33

Fig. 2.4 Lieselotte von der Pfalz introduces the Prince Elector of Saxony to Louis XIV in 1714. Louis de Silvestre, König Ludwig XIV. empfängt den späteren König von Polen und Kurfürsten von Sachsen August III (1715), oil on canvas. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Louis_XIV_1714.jpg, public domain.

In the year 1700, Lieselotte reported that after a ballet performance, the court danced many minuets.34 This is interesting because she had remarked in 1695 that dancing had fallen out of fashion in France. She claimed that it was so popular for people to play cards at parties that young people did not want to dance anymore.35 Historian Philip F. Riley substantiated this idea when he described how Louis XIV, during the last three decades of his reign, considered dancing a sin and persecuted those who practised it. At the court, dancing was to a large extent replaced by gambling during the 1690s.36 By 1697, dancing was still a rare activity, but Lieselotte hoped that the incoming duchess of Bourgogne, Princess Marie Adélaïde of Savoy (1685–1712), would restore its fashionability.37 A spate of deaths in the royal family during 1711–12 (including the Dauphin [Crown Prince], his son and daughter-in-law, plus two of their children) meant that the five-year-old great-grandson of Louis XIV, upon the latter’s death in 1715, succeeded him as Louis XV, after a period of regency. It is an open question how all these deaths in the royal family may have influenced life at court in the regency that followed, as answering this question would require a systematic search for sources that is beyond the scope of this book. However, a modest search in French newspapers returns a few hints that the minuet continued at the court through the reign of Louis XV. The Parisian La Gazette reported that an eleven-year-old Louis XV danced the minuet at a reception held in January 1722 to mark the arrival of the seven-year-old princess from Spain who was meant to become his queen.38 Much later, in October 1757, the same Gazette reported that a court ball opened with minuets, though the king and queen were merely observers of, rather than participants in, the dance.39

Fig. 2.5 Louis XIV, his son, grandson and great-grandson, the later Louis XV with his governess. French school, Madame de Ventadour with Louis XIV and his Heirs (c. 1715–1720), oil on canvas. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Louis_XIV_of_France_and_his_family_attributed_to_Nicolas_de_Largilli%C3%A8re.jpg, public domain.

The French Revolution

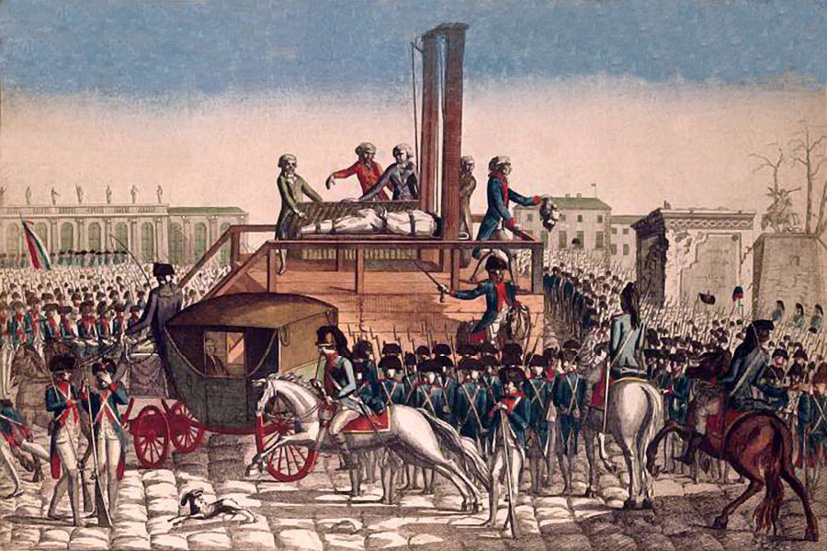

The French Revolution started in 1789 and progressed through many different stages until Napoleon Bonaparte took power in 1799. This period included the execution of the King and Queen, plus thousands of aristocrats and leading people. There were several periods of killings and executions called la terreur. Many sources from the time suggest that dancing, though not killed by the Revolution, was hampered and changed by these periods of terror. In the words of one commentator:

During the terrible days of the revolutionary government, the Jacobins [males and females] were the only ones who danced. The great masters of the minuet, the gavotte and the Allemande found themselves condemned to a very disastrous rest at their purse and forced to give their place to masters of an inferior rank. They found more activity than they wanted amongst the female citizens of the suburbs Saint Antoine and Saint Marceau, whose fathers or young husbands showed indifference to the bloody scenes that happened in the square of Louis XV or at the throne barrier.

After 9 Thermidor, joy and dancing began again with much more brilliance and more generally than before, since it had been suppressed for a long time. Then there was not a single girl who did not hurry to take lessons in such a unique art so well suited to enable them to distinguish themselves in public and private assemblies. […]

At the same time so many families deplored the tragic death of their leaders and of what was dearest to them, others danced on the ground of the old cemetery Saint Sulpice. The dance teachers were more in vogue than ever during the consulate and the empire.

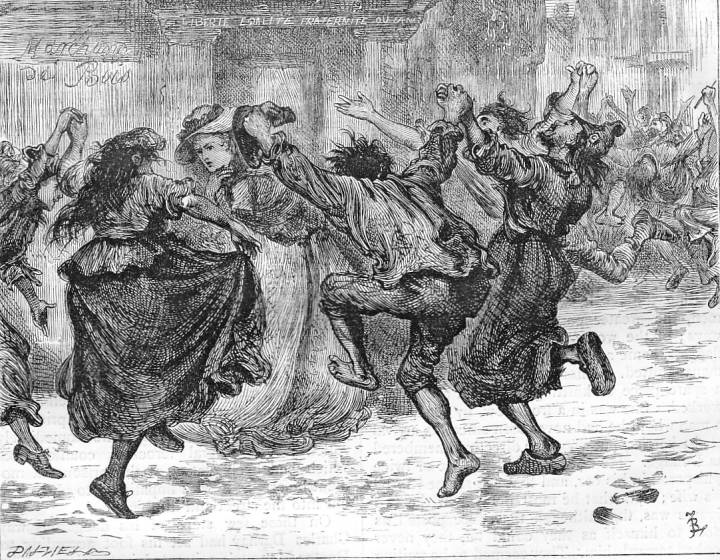

Fig. 2.6 Fred Barnard, The Mob in Paris dancing La Carmagnole (1870). La Carmagnole was a chain dance with singing popular among common people during the French Revolution, known from 1792. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:T2C,_Fred_Barnard,_The_Carmagnole_(III,5).jpeg, public domain.

All doors were opened for the dancing masters: the court, the palaces, the hotels, the residential school of young ladies, the houses of bankers. It only took a word and all the beauties hastened there to receive their lessons. It was then a complete revolution in the art of choreography. To become worthy of trust for their practices and to increase their reputation, Masters were occupied with inventing new figures, new steps and new contradances or they borrowed from abroad that which their genius could not imagine. It was in this way that the Walse [waltz], heavily executed by male and female dancers from Germany, was imported to France to the despair of mothers and husbands. This lustful dance was first and for many years in fashion in large houses and amongst the bourgeois. Today, it is no longer much in use, except in the most common balls and taverns.40

Fig. 2.7 Execution of deposed French King Louis XVI, anonymous eighteenth-century engraving, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Exécution_de_Louis_XVI_Carnavalet.jpg, public domain.

The minuet was a product of Louis XIV’s court, known as l’ancien régime, the old regime before the revolution in 1789. In France, it seems that the revolution did kill the minuet; in the nostalgic short story of de Maupaussant, presented at the beginning of this book, the old minuet dancer said: ‘Depuis qu’il n’y a plus de roi, plus de menuet’ [Since there is no king anymore, there is no minuet].41

The minuet was associated with the court and the royals to such a degree that few people dared to or wanted to dance it during the Revolution; the new leading classes of the country had not learned or even wanted to learn it. On the other hand, Jean-Michel Guilcher suggests that the minuet was already falling out of favour prior to the Revolution, being hardly danced any more during the very last years of l’ancien régime.42 The contradances had a much broader reach even before the Revolution. These dances were easily refreshed by the dancing masters to remove any association with the earlier regime and remained in fashion.

From an account by the French Duchess de Arantés, we can glean some of the feelings and the unsaid ways of expressing adherence right after the French Revolution. She, Laure Martin de Permond (1784–1838), married one of Napoleon’s close co-operators, general Jean-Andoche Junot (1771–1813), in 1800. She was the daughter of a widow in whose Paris home Napoleon had been a frequent guest at the beginning of his career around 1784. Later, after falling out with Napoleon, the widow kept a house where she received sympathisers of l’ancien régime.43 Some weeks after the wedding of her daughter, the widow threw the usual wedding party in her home and the family convinced Napoleon (who was at that time the first consul) and his wife to attend. It was a party at which many political, as well as personal, tensions lay just under the surface.

Fig. 2.8 Marguerite Gérard, La Duchesse Abrantes and General Junot (c. 1800), painting. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marguerite_G%C3%A9rard_-_La_Duchesse_Abrantes_et_le_General_Junot.jpg, public domain.

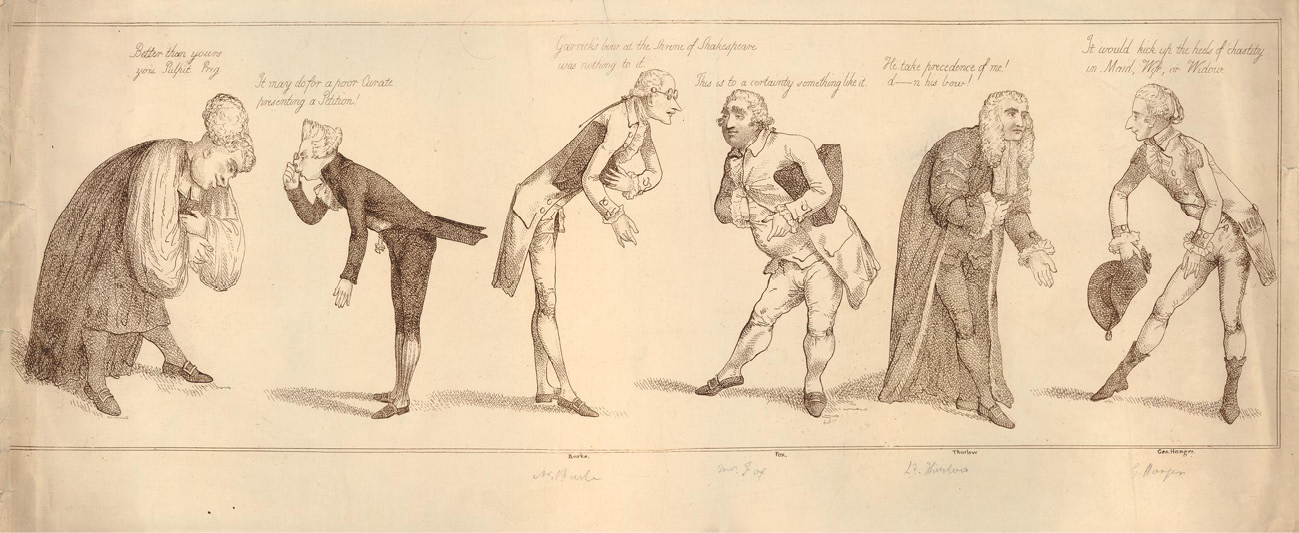

According to the hostess, dancing the minuet was a requirement at wedding parties, though the bride protested and cursed the practice. They resolved the disagreement with a compromise: the bride consented to take several minuet lessons from a famous ballet dancer named Gardel and arranged for another renowned minuet dancer from l’ancien régime, M Treniz, to dance with her, all the while hoping to avoid the performance. M Treniz was not present when it was time for the dance but the hostess insisted, so the bride had to dance with a different gentleman. This man had come to the party without a hat and had to borrow one since the minuet could not be done without it. When the minuet had finished, M Treniz appeared and was offended that somebody else had taken his place in the dance. He gave a long speech about the importance of mastering the greeting with the hat that prefaced the dance, indirectly shaming his stand-in. Napoleon, upon hearing this, was half-amused and half-provoked by the outdated topic and the comic figure of the man. What may have been the conventional or acceptable style during the old regime had clearly become a caricature.

Fig. 2.9 The Prince’s Bow (1788), etching after Frederick George Byron. Satire on greetings with hat, targeting particularly the later King George IV. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Prince%27s_bow._(BM_1868,0808.5697).jpg, public domain.

The bride did not spell out why she was so reluctant to dance the minuet. The social dances used at the party are referred to as reels and anglaises. It seems no one other than the bride and her partner danced the minuet, though a number of the older guests undoubtedly knew the minuet. It had only been eleven years since the start of the Revolution. Perhaps because the minuet was expected to be danced very well, we might guess that the bride felt that she had not mastered it to the level required. What seems more likely, however, is that she did not want to be perceived as old-fashioned; but it is even more probable that she was viewing the minuet as inappropriate to dance in the presence of the first consul. The groom was, after all, one of Napoleon’s men. She may even have worried that it would be insulting to the first consul to honour l’ancien régime by performing ‘its’ dance. Her mother, on the other hand, may have wished to provoke and irritate the old friend she had fallen out with, playing a game of etiquette with seeming candour and innocence but a hidden edge of sympathy for Napoleon’s adversaries.

The defeat and imprisonment of Napoleon in 1814 was followed by the so-called Bourbon Restoration, which lasted until the July Revolution of 1830. Brother of the executed King Louis XVI reigned in a highly conservative fashion, allowing the exiled to return. Although they were unable to reverse most of the changes introduced by the French Revolution and Napoleon, the erstwhile aristocrats could be expected to revive practices from l’ancien régime. However, it seems that the minuet did not experience any real revival, even if it may have lingered on to some degree as a symbol of distinguished behaviour in the upper classes. Many other European courts had followed the model of the French court and had adopted the minuet accordingly. Most royals in Europe had been appalled at the beheading of their peers and in some cases their family members in France. It is reasonable to expect them to have retained the pre-terror French ideals, including the minuet. In spite of this, the dance does seem to have fallen out of frequent use at most European courts by the beginning of the nineteenth century.

The Minuet at Other European Courts

From brief mentions, we can build up a picture of the minuet as it was being performed and conceived by the aristocracy outside of France.

At the Prussian court in Berlin, for example, the minuet was in use in 1797. The famous Oberhofmeisterin Sophie von Voss (1729–1814), when she almost seventy years old, wrote that she danced several minuets at a party for visitors and court staff that year.44

Fig. 2.10 The bride Princess Luise kisses the forehead of a well-wisher from the crowd. The Oberhofmeisterin von Voss at the left. Woldemar Friedrich, [untitled] (1896). Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prinzessin_Luise_k%C3%BCsst_ein_M%C3%A4dchen_aus_dem_Volk.jpg, public domain.

Writer Felix Eberty (1812–84) grew up in Berlin in a bourgeois Jewish family. He recalled his youth as a time when, ‘We learned just as little French language as we learned to dance—both these were considered non-German and unpatriotic right after the liberation war (1813), and we, the boys, detested it’.45 Eberty also referred to his aunt Hanna ‘who when she was young had been an attractive partner for the French officers who preferred to invite her to [dance] ‘Ekossaise’ and ‘Kontertanz’. Waltz and Galopp are newer and the minuet already was about to die’.46 He might be describing a time around 1800 or even earlier.

Fig. 2.11 Georg Cristoph Grooth, portrait of Friedrich Wilhelm von Bergholtz (1742), oil. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Friedrich_Wilhelm_von_Bergholtz.jpg, public domain.

Friedrich Wilhelm von Bergholz (1699–1765) was a courtier from Holstein who followed his Duke on a mission to Russia and stayed there for some years. In his diary, he described dancing at the Russian court in 1722, at which time the minuet seems already well known:

After the table had been lifted, there was dancing, and Her Royal Highness, our most gracious lord, started the ball with the Empress in a Polish dance. The very smallest imperial princess, along with the Grand Duke and his sister, also appeared at the beginning of the dance, so afterwards the little imperial princess of 5 years also had to dance English, Polish and Minuets, which for her age was quite well done. She is an extremely beautiful child. At around 9 o’clock, the dance ended with the English chain dance, in which the Empress herself also danced.47

This was towards the end of the reign of Peter the Great (1672–1725). He brought European cultural traditions to Russia and may even have introduced polite social dancing. Before this time, women did not participate in parties at the court but were kept out of sight in the terem.48

Fig. 2.12 Mikhail Petrovitch Klodt, Terem of tsarevnas (1878). Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Terem_tsareven_klodt.jpg, public domain.

The minuet seems to have gone out of use in Russia around 1800. The German philologist Aage Ansgar Hansen-Löve summed up changes in the social dance at the Russian court around this time:

In Russia, the transition from typical aristocratic court dances like the minuet to the repertoire of social dances, such as the mazurka and the Waltz, took place at the beginning of the 19th century. It happened in the course of a new appropriation wave and is to understand as a new break of tradition.49

One might question whether the decline of the minuet in Russia was a widespread change. All three dances were used at court by the aristocrats. We do not know if the waltz also influenced the lower classes of Russia as early as this or whether the dance had not yet filtered down to them from the aristocrats.

The unhappy consort of the British Regent (later King George IV of Britain), Caroline of Brunswick, went travelling from 1814 and visited several European courts. One member of her staff, John Adolphus, kept a diary in which he described the German court of Kassel where she stayed with Wilhelm I, Elector of Hesse.50 Adolphus observed minuet dancing at this court and suggested that the practice was customary there. It seems strange that the minuet continued to have this prominence as late as 1814 and that the waltz was not mentioned, especially as Caroline was known to have danced the waltz much earlier in Britain when she arrived to marry the British Regent. Adolphus may have been trying to protect Caroline from being considered too German and therefore stressed the minuet, taking care not to mention the waltz.

Fig. 2.13 Anonymous, Queen Caroline, wife of King George IV, is greeted by people from Marylebone (c. 1820), etching. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Queen_Caroline,_wife_of_King_George_IV,_is_greeted_by_Wellcome_L0050927.jpg, CC BY 4.0.

Another reason why Adolphus may not have mentioned the waltz is that there might have been a ban on this dance at this court and that they tried to prolong the use of the minuet. Napoleon favoured his own family and gave the land of the Elector to his brother. In 1814, at the time of the report, the Elector of Hesse had just returned to his position after the defeat of Napoleon and may have wished to reinstate the earlier customs of the court. As Adolphus wrote:

After supper, the company put on their masks; her Highness is led into the ballroom, and the rest follow, each lady being handed in by her partner. The Electress and her partner walk to the upper end of the room; the next couple stop at a small distance below them; the third next to the second, and so on, till this double line filled the length of the room. From this arrangement, one would naturally expect a country-dance; but a minuet is all. The music begins, and the masked people, consisting of twenty or thirty couples, walk a minuet together. This being over, which is rather a confused affair, everyone sits down, the Electress excepted. She generally dances nine or ten minuets successively with as many different gentlemen. She then takes her seat till the rest of the company have danced minuets; which being over, cotillions and country-dances begin, and continue till four or five in the morning.51

It is interesting to note that Adolphus described the court as having ‘walked’ the minuet. He probably meant that they did not use the minuet steps but simple walking. This technique was also used in Contra Dances and was a sign that dancers were forgetting the dance, that it was losing its popularity. A similar account comes from the province of France in 1701, ‘They danced the minuet doing nothing but walking on the beat’. Jean-Michel Guilcher interprets this excerpt as an example of how upper-class people in the towns imitated the court dances but had not learned them properly.52

State of Research

On the surface, it may seem that the literature about the minuet is not very extensive. After all, few monographs have ‘minuet’ in their titles. However, when we expand the search to include separate articles or books with chapters about the dance, more substantial amounts of information are found. To survey this material, I have grouped it into different types, according to its creators and their purpose.

The Dancing Masters

The dancing masters were the first experts who wrote professionally about minuet dancing. The famous book of Pierre Rameau from 1725 is often considered the first significant description of the minuet as a standard social dance: le menuet ordinaire. Information about the dance was published before that, however, in Feuillet notation, as well as in a couple of books produced by dancing masters in Leipzig (at that time, part of the Electorate of Saxony). It is quite surprising to see that there were so many dancing masters publishing books in a city with only sixteen thousand inhabitants. Kurt Petermann has discussed this leading group of academic dancing masters, reprinting works by several of them, including Johan Pasch, Samuel Behr, Gottfried Taubert and Louis Bonin.53 Tilden Russel has examined the corpus of eight books/editions published in Leipzig in the period 1703–17, finding commonalities that suggest their authors may have borrowed from each other. Still, only a few of these texts contain descriptions of the minuet.54 It is but a small number of books from the early eighteenth century that have caught the attention and scrutiny of dance historians to date.55

Several manuals from dancing masters published later in the century included descriptions of the minuet. These texts have hardly been systematically surveyed and compared, except in the book The Menuet de la Cour (2007).56 The attitude of the renowned nineteenth-century French dancing master, Henri Cellarius, represented the status of the minuet in Europe during his time:

I will cite, for instance, a dance which has not been executed in France for many years, but which still finds partisans in other countries,—the minuet de la cour. This dance is much too foreign to our manners for us ever to expect to see it re-appear. But, as a study, it offers very great advantages; it impresses on the form positions both noble and graceful.57

Another vital source of material for studying the early minuet is the Feuillet notations, although the number of minuets so notated is not large. Francine Lancelot, a dance researcher and pioneer of historical dance in France, has published an impressive work surveying these Feuillet notations. She wrote,

The corpus is made up of the compositions of French choreographers notated in Feuillet notation. […] The total corpus as of today includes 539 dances, printed or manuscript, coming from collections of dances, treatises, or published separately. These sources are spread out between 1700 and 1790. […] The choreographic corpus of minuets is made up of twenty dances—sixteen ballroom dances and four ballet entrées—to which are added six movements contained in multipartite forms. 58

The first minuet in Feuillet notation was published in 1706 and the final two were published in 1781. Lancelot defined the ballroom dances as those indicated as such by the titles of the collections, such as the annual collections from 1703 to 1724, or by the preface. The other group of dances is the ballet entrées. She found the minuet corpus quite slim ‘with regards to the first appearance of the menuet in the mid-seventeenth century, its vivid rise and its preponderant place during the entire eighteenth century‘.59 I discuss the work of Lancelot here because she presents the historical material in Feuillet notation but her work is also interesting for the revival of historical dances—a different but no less important or valid kind of research.

Works Connected to the Reconstruction of Historical Dances

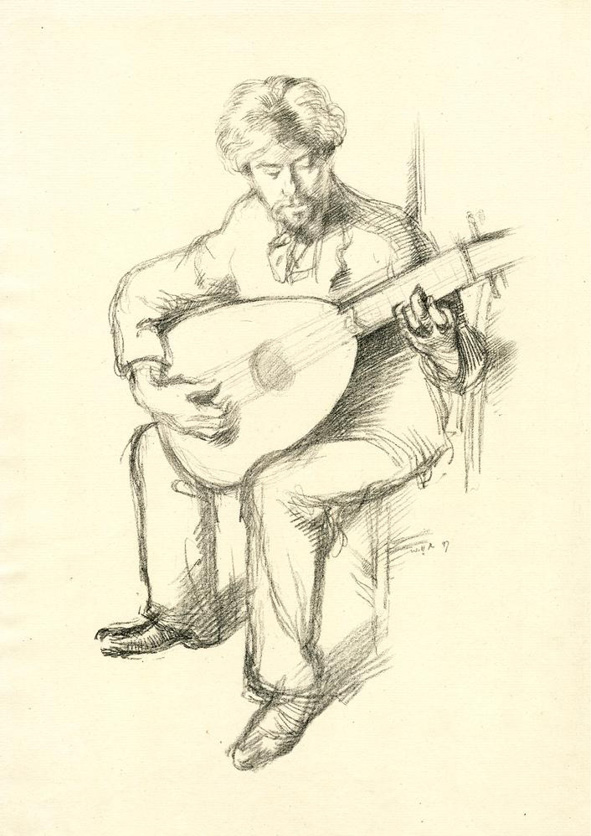

Much of the literature on the minuet is linked to the movement for the revival of historical dances. Most authors writing on the minuet seem to have participated in this movement and they intend for their work, including the re-presentation of dance manuals, to serve as aids in this revival. The first twentieth-century manual of what the author called ‘historical dances’ was probably published by the American pedagogue Mari Ruef Hofer in 1917.60 Europe’s revival movement during the same period was likely inspired by Eugène Arnold Dolmetsch (1858–1940), a French-born musician and instrument maker who was also a leading figure in the twentieth-century revival of interest in early music.

Fig. 2.14 Anonymous, portrait of Eugène Arnold Dolmetsch, playing the lute (1897), lithograph. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Print_(BM_1903,1006.7).jpg, public domain.

According to Harry Haskell, ‘Dolmetsch’s interest in historical dances paralleled the revival of folk dance in England by Cecil Sharp and others in the early 1900s’.61 He collected dance treatises and showed them to friends and acquaintances, hoping to interest them in reconstructing the old steps and patterns. His third wife, Mabel (1874–1963), eventually took up his challenge and became an acknowledged authority on historical dance, although her work has been criticised in retrospect.62 Already in 1916, she published her first article on the subject but her major works came in 1949 and 1954.63 Peter Brinson described her involvement in the revival as follows: ‘The study of early dance forms was led by Mabel Dolmetsch and Melusine Wood. They were joined presently by Joan Wildeblood, Mary Skeaping and Belinda Quirey; Skeaping and Quirey being pupils of Melusine Wood in this area of scholarship’.64 Wood also published in the early twentieth century, but her three essential manuals for historical dance appeared between 1952 and 1960. 65 Wood died in 1971. Dolmetsch and Wood intended their manuals for practical purposes and often do not supply references for their sources. Belinda Quirey (1912–1996), a British dance history teacher and student of Melusine Wood, also published a popular dance history that still has references.66

The two most prominent authors in the second generation of dance historians take took up a novel approach by combining interpretations of referenced historical sources with corresponding presentations of dance history. The British historical dancer, scholar, and student of Melusine Wood Wendy Hilton (1931–2002), published an advanced work on interpreting the descriptions and Feuillet notations in The French Noble Style, 1690–1725 (1981).67 The German dance historian and music pedagogue Karl Heinz Taubert (1912–1990) published several works, including summaries of dance history and dance descriptions, a general collection in 1968, a book on Baroque dances, and a monograph on the Minuet. 68 Mary Skeaping (1902–1984) was a British ballerina and choreographer who served as ballet master of the Royal Swedish Ballet in the 1950s. Whilst in Sweden, she started reconstructing seventeenth and eighteenth-century court ballets and involved the Swedish dance pedagogue Regina Beck-Friis (1940–2009) in this effort. Beck-Friis continued this work, later publishing four volumes (and a video) in Swedish on historical dances from the continent.69 Finally, we need to mention Volker Saftien’s book, which combines dance descriptions and discussion of their sources, engaging with interpretation and context.70

Research Emphasizing Minuet Music

Publications that discuss the minuet but do not include dance descriptions or notations aimed at the historical dance movement often focus instead on the music of the minuet. This is a substantial body of literature but one we do not take up here in detail. The American dance and music historian Tilden Russell has published extensively on the minuet as a form of dance, but he often approaches it from a musical angle. His Master’s dissertation from 1983 is mainly about the changes in minuet music during the period when minuet dancing 1781–1825 was in decline on the European continent.71 He returns to the music-dance relationship in several articles, claiming, for example, that

Odd-measured phrases, […] existed in dance music. However, they did not confuse the dancers or render the music undanceable; on the contrary, they seem to have had a positively stimulating effect.72

[…] That dance-minuets were full of examples of flexibility and liberties with gross form, phrase and smaller details […] When fully realized in performance by dancers and musicians, the dance minuet was in its way as much a play with form as the art minuet.73

More recently, Eric McKee has written on the dance-music relationship in the minuet and the waltz. His primary research question asked ‘What did the dancers require of the music, and how did the composers of the minuet and waltz respond to the practical needs of the dancers?’74 McKee’s method is a sophisticated and detailed comparison of minuet scores by Bach and Mozart and dance descriptions by dancing masters at work, predominantly in the eighteenth century. However, his starting point is a problematic assumption about the structural requirements of a minuet or waltz. Dancers and musicians usually want to find a shared harmony; the tolerance to the other part may have its limits but that is a question about performance rather than structure.75 This is seen in the fact that old dance melodies are often adapted for use with new dances. Minuet melodies can be found accompanying dances such as polska, springar or waltz in Nordic dance music. In these cases, it is not the musical structure that has been changed; it is instead the tempo and metrical accentuation. McKee also emphasised what he called a hypermeter as he searched for ‘the dancer’s cueing requirements’ in the music.76 Experience with traditional triple-time music with a similar hypermeter structure shows that the main problem is to get started on the right beat, rather than on the right bar; in fact, it is often acceptable to begin on any bar of the music. Russell’s claim that there was entirely danceable music with odd-measured phrases does not support McKee’s theory of the hypermeter’s correspondence in music and dance. This example reveals the problem of working strictly from prescriptive material, without studying the performance practice. Petri Hoppu responded to my question about practice as follows:

People without knowledge of Western theory of music don’t think about ‘bars/measures’ while beginning the dance but they perceive the music in different ways, listening to the beat and accents and their relation to the overall melodic and rhythmic structure (the perception is complicated). Therefore, it is possible they start the dance in the middle of the bar at the end of a musical phrase, as often happens in Nykarleby region. When it comes to the question of minuets with odd-measured phrases, only a few of them exist in the Finnish-Swedish collections (together with minuets that may contain 2/4 or 4/4 bars). These are rare, and I’ve never heard that one would have played them during actual dancing.77

This commentary sheds important light on the question about melodies with odd-measured phrases: even if they seem not to have been popular as dance music, they should, in principle, not cause problems for dancers.

The Nordic Folk Dance Minuet

The music of the minuet has not been a core focus of Nordic folk music research. In Norway and Sweden, where the dance disappeared from practice in the nineteenth century, the topic remained on the periphery of scholarship concerning folk dance and folk music. On the other hand, in Denmark and Finland, folk-dance and folk-music scholars did document minuet dance movements as well as dance music, and they published a few small articles early in the twentieth century.78 Professor Otto Andersson’s work in Swedish-speaking Finland from the beginning of the twentieth century to the 1960s should be mentioned as an early example of extensive minuet music collection, analysis, and publication.79

Substantial research and publication on minuet as folk dance and it’s music accelerated after 1990, driven mainly by some of the authors of this book, other individuals connected to the authors’ group and to the group’s parent organisation, Nordisk forening for folkedansforskning (who are supporting this work). Petri Hoppu completed his doctoral dissertation about the minuet in Finland from a socio-historical perspective in 1999. It emphasised both symbolic and embodied aspects of the dance. According to Hoppu, minuet dancing, including the dance structure, was closely connected to Finland’s social and cultural development during the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries.80 Gunnel Biskop began publishing articles on the minuet in 1993 in Folkdansaren, a membership journal for the Finnish folk-dance organisation Finlands svenska folkdansring rf., a practice which she continued for two decades. These articles provided much of the material for her book Menuetten—älsklingsdansen (2015), upon which a large part of the present text is based. Biskop drew from her lengthy research into Nordic sources but also her own practical knowledge of the dance. Her work connects these findings to general European history.81

Concluding Remarks

In conclusion, we have found that the term ‘minuet’ and its versions in European languages refer to a precisely definable movement structure in the field of social dance. It has few variations compared to other dance forms or paradigms—comparisons that will be discussed in greater detail in the following chapters of this book. We have also suggested that the minuet might be seen as part of a larger paradigm of couple dances widespread, at least in Spain and France where the couples dance in front of each other without couple turning motifs.82 Finally, we have maintained that the dance clearly belonged to the upper classes and was taken up by the lower classes only in the Nordic countries, with the Czech mineth as a possible minor exception.

References

Abrantès, Laure J., Mémoires de madame la duchesse d’Abrantès, ou Souvenirs historique sur Napoléon, la Révolution, le Directoire, le Consulat, l’Empire et la Restauration, 3 vols. (Paris: L’Adcocat librairie, 1831)

Adolphus, John, Memoirs of Caroline, Queen Consort of Great Britain (London: Jones, 1821)

Andersson, Otto, VI A 1 Äldre dansmelodier. Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning. SLS 400 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1963)

Arbeau, Thoinot, Orchésographie: méthode et théorie en forme de discours et tablature pour apprendre à danser, battre le tambour (Geneva: Editions Minkoff, 1972)

Bakka, Egil, ‘Dance paradigms: Movement analysis and dance studies’, in Dance and Society. Dancer as a Cultural Performer, ed. by Elsie Ivancich Dunin, Anne von Bibra Wharton, and László Felföldi (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2005), pp. 72–80

―, ‘Innleiing. Turdansen i Folkedansarbeidet’, in Klara Semb, Norske Folkedansar. Turdansar (Oslo: Noregs boklag, 1991), pp. 17–58

―, ‘Revisiting Typology and Classification in the Era of Digital Humanities’, Arv, 75 (2019), 153–79

―, ‘Typologi og klassifisering som metode’, in Nordisk Folkedanstypologi: En systematisk katalog over publiserte nordiske folkedanser, ed. by Egil Bakka (Trondheim: Rådet for folkemusikk og folkedans, 1997), pp. 7–16

Beck-Friis, Regina, The Joy of Dance through the Ages. VHS tape (Malmö: Tönnheims Förlag, 1998)

Beck-Friis, Regina, Magnus Blomkvist, and Birgitta Nordenfelt, Dansnöjen Genom Tiden, 3 vols. (Lund: Historiska Media, 1998)

―, Västeuropeiska danser från medeltid och renässans (Stockholm: Akademilitteratur, 1980, 1998)

Behr, Samuel Rudolph and Kurt Petermann, Die Kunst, Wohl Zu Tantzen (Leipzig: Zentralantiquariat der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, 1977)

Bergholz, Friedrich W. V., ‘Tagebuch 1721–1724 Dritter Teil‘, Magazin Für Die Neue Historie Und Geographie, 21 (1787), 180–552

Biskop, Gunnel, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015)

Blasis, Carlo and R. Barton, Notes upon Dancing, Historical and Practical (London: M. Delaporte, 1847)

Bonin, Louis and Johann Leonhard Rost, Die Neueste Art Zur Galanten Und Theatralischen Tanz-Kunst (Berlin: Edition Hentrich, 1996)

Brennet, Michel, Dictionnaire pratique et historique de la musique (Metronimo.com, 2003), https://dictionnaire.metronimo.com/index.php?a=print&d=1&t=5615

Brinson, Peter, Dance as Education: Towards a National Dance Culture (Taylor and Francis, London, 2004)

Brossard, Sebastien D., Dictionnaire de musique contenant une explication des termes Grecs, Latin, Italiens & François les plus usitez dans la musique ... et un catalogue de plus de 900 auteurs qui ont écrit sur la musique en toutes sortes de temps de pays & de langues ... (Amsterdam: aux dépens d’ Estienne Roger, 1707), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1510881v

Caillot, Antoine, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des mœurs et usages des français depuis les plus hautes conditions: jusqu’aux classes inférieures de la société, pendant le règne de Louis XVI, sous le Directoire exécutif, sous napoléon bonaparte, et jusqu’à nos jours, 2 vols (Paris: Dauvin, 1827), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6378010q.texteImage

Cellarius, Henri, Fashionable Dancing: By Cellarius. with Twelve Illustrations by Gavarni (London: David Bogue, 1847), https://www.libraryofdance.org/manuals/1847-Cellarius-Fashionable_Dancing_1_(Goog).pdf

Dolmetsch, Mabel, Dances of England and France from 1450–1600 (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1949)

―, Dances of Spain and Italy: From 1400 to 1600 (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1954)

―, ‘Sixteenth-Century Dances’, The Musical Times, 57 (1916), 142–45

Durán y Ortega, Josefa, Memoiren der Sennora Pepita, 3 vols (Berlin: Hermann Hollstein, 1854), III

Eberty, Felix, Jugenderinnerungen Eines alten Berliners (Berlin: Hertz, 1878)

Guilcher, Jean-Michel, La Contredanse et les renouvellements de la danse franc̦aise (Paris: Mouton 1969)

―, La Tradition Populaire de danse en Basse-Bretagne (Spézet: Coop Breizh, 1997)

―, La Tradition de danse en Béarn et Pays Basque français (Paris: Editions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 1984)

Hansen-Löve, Aage A., ‚Von Der Dominanz zur Hierarchie im System der Kunstformen zwischen Avantgarde Und Sozrealismus‘, Wiener Slawistischer Almanach, 47 (2001), 7

Haskell, Harry, The Early Music Revival: A History (Mineola, NY: Dover, 1996)

Haynes, Bruce and Robin Spencer, The Eloquent Oboe: A History of the Hautboy 1640–1760 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001)

Heikel, Yngvar, ‘Om Menuetter i Österbotten’, Budkavlen, 2 (1929), 105–11

Heale, Philippa, ‘Seguidilla’, in International Encyclopedia of Dance, 5 vols. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998)

Heydenreich, Karl H., ‚Über Tanz Und Bälle‘, Deutsche Monatschrift (May 1798), 43–52

Hilton, Wendy, Dance of Court & Theater: The French Noble Style, 1690–1725 ([Princeton]: Princeton Book Company, 1981)

Hofer, Mari R., Polite and Social Dances: A Collection of Historic Dances, Spanish, Italian, French, English, German, American, with Historical Sketches, Descriptions of the Dances and Instructions for their Performance (Chicago: Clayton F. Summy, 1917)

Hoppu, Petri, Symbolien ja sanattomuuden tanssi. Menuetti Suomessa 1700-luvulta nykyaikaan (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1999)

Horak, Karl, Treskowitzer Menuett (Dancilla, 2020), https://www.dancilla.com/wiki/index.php/Treskowitzer_Menuett

Kubiena, Fritz, Kuhländer Tänze. Dreißig der Schönsten Alten Tänze aus dem Kuhländchen (Neutitschein: Selbstverl. d. Hrsg., 1920)

Lancelot, Francine, La belle dance: Catalogue raisonné fait en l’an 1995 (Paris: Van Dieren, 1996)

Lidové Tance z Čech, Moravy a Slezska I - X, dir. by Zdenka Jelínková and Hanna Laudova (Strážnice: Ústav lidové kultury ve Strážnici, 1994)

Ling, Jan, A History of European Folk Music (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1997)

Guy de Maupassant, ‘Menuet’, in Oeuvres complètes, contes de la bécasse ([n.p.]: Arvensa Editions, 2021), pp. 1957–60

McKee, Eric, Decorum of the Minuet, Delirium of the Waltz: A Study of Dance-Music Relations in 3/4 Time (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012)

Molière, J. B. P., Le bourgeois gentilhomme. Comédie-ballet. Faite à Chambort, pour le divertissement du Roy (Paris: Suivant la Copie imprimée, 1680)

Orléans, Charlotte-Elisabeth and Babin Malte-Ludolf, Liselotte Von der Pfalz in Ihren Harling-Briefen: Sämtliche Briefe der Elisabeth Charlotte, Duchesse d’Orléans, and die Oberhofmeisterin Anna Katharina Von Harling, Geb. Von Offeln, und Deren Gemahl Christian Friedrich Von Harling, Geheimrat und Oberstallmeister, zu Hannover (Hanover: Hahn, 2007)

Pasch, Johann and Kurt Petermann, Beschreibung Wahrer Tanz-Kunst (Leipzig: Zentralantiquariat der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, 1978)

Pure, Michel de, Idée des spectacles anciens et nouveaux. Des anciens: cirques, amphithéâtres, theatres, naumachies, triomphes. nouveaux: comédie, mascarades, exercices et reveuës militaires, feux d’artifices, entrées des rois et des regnes (Paris: Michel Brunet, 1668), https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Id%C3%A9e_des_spectacles_anciens_et_nouveaux/MOJspb_BxekC?hl=en&gbpv=1

Pushkareva, Natalia, Women in Russian History: From the Tenth to the Twentieth Century (Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe, 1997)

Quirey, Belinda, Steve Bradshaw, and Ronald Smedley, May I have the Pleasure?: The Story of Popular Dancing (London: Dance Books Limited, 1976)

Ramovš, Mirko, Polka je Ukazana: Plesno Izročilo na Slovenskem. Od Slovenske Istre do Trente, 2 vols. (Ljubljana: Kres, 1999)

Riley, Philip F., A Lust for Virtue: Louis XIV’s Attack on Sin in Seventeenth Century France (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001)

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques and Claude Dauphin, Le dictionnaire de musique de Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Une édition critique (Bern: Peter Lang, 2008)

Russell, Tilden, ‘Minuet Form and Phraseology in Recueils and Manuscript Tune boks’, Journal of Musicology, 17 (1999), 386–419

―, Minuet, Scherzando, and Scherzo: The Dance Movement in Transition, 1781–1825 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983)

―, ‘The Minuet According to Taubert’, Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, 24 (2006), 138–62

―, ‘The Unconventional Dance Minuet: Choreographies of the Menuet d’Exaudet’, Acta Musicologica, 64 (1992), 118–38

Russell, Tilden, and Dominique Bourassa, The Menuet de la Cour (Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 2007)

Saftien, Volker, Ars Saltandi: Der europäische Gesellschaftstanz im Zeitalter der Renaissance und des Barock (Hildesheim: Olms, 1994)

Sutton, Julia, ‘The Minuet: An Elegant Phoenix’, Dance Chronicle, 8 (1984), 119–52

Sychra, Antonín, Antonín Dvořák: Zur Ästhetik Seines sinfonischen Schaffens ([Leipzig]: Deutscher Verlag für Musik, VEB, 1973)

Taubert, Gottfried and Raoul-Auger Feuillet, Rechtschaffener Tanzmeister, oder, gründliche Erklärung der frantzösischen Tantz-Kunst: bestehend in drey Büchern, Deren das Erste Historice des Tantzens Ursprung Fortgang, Verbesserung, Unterschiedlichen Gebrauch (Leipzig: F. Lanckischens, 1717)

Taubert, Karl H., Barock-Tänze: Geschichte, Wesen und Form, Choreographie und Tanz-Praxis (Zürich: Pan, 1986).

―, Höfische Tänze: Ihre Geschichte Und Choreographie (Mainz: Schott, 1968)

Tomlinson, Kellom, The Art of Dancing Explained by Reading and Figures: Whereby the Manner of Performing the Steps is made Easy by a New and Familiar Method: Being the Original Work, First Design’d in the Year 1724, and Now Published by Kellom Tomlinson, Dancing-Master [...] in Two Books (London: the author, 1735)

Urup, Henning, Dans i Danmark: Danseformerne ca. 1600 til 1950 (København: Museum Tusculanum, 2007)

Voss, Sophie Marie von, Neunundsechzig Jahre am preußischen Hofe: Aus den Erinnerungen der Oberhofmeisterin Sophie Marie Gräfin Von Voss (Berlin: Berlin Story Verlag, 2012)

Wolfram, Richard, Die Volkstänze in Österreich und verwandte Tänze in Europa (Salzburg: Müller, 1951)

Wood, Melusine, Advanced Historical Dances (London: Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing, 1960)

―, Historical Dances (Twelfth to Nineteenth Century): Their Manner of Performance and their Place in the Social Life of the Time (London: Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing, 1964)

―, More Historical Dances, Comprising the Technical Part of the Elementary Syllabus and the Intermediate Syllabus: The Latter Section Including such Dances as Appertain but Not Previously Described (London: Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing, 1956)

―, Some Historical Dances, Twelfth to Nineteenth Century: Their Manner of Performance and their Place in the Social Life of the Time (London: Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing, 1952)

―, ‘What did they really dance in the Middle Ages?’, Dancing Times, 25 (1935), 24–26

Yih, Yuen-Ming D., Music and Dance of Haitian Vodou: Diversity and Unity in Regional Repertoires (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Wesleyan University, 1995)

‚Zur Oper Don Juan. Kontroversfragen Bezüglich Der Darstellung Auf Der Bühne‘, Morgenblatt Für Gebildete Leser (1865), 772–80

1 Unlike the popular understanding, the Danish term molinask does not refer to the minuet but to a contradance.

2 Carlo Blasis and R. Barton, Notes upon Dancing, Historical and Practical (London: M. Delaporte, 1847), p. 52.

3 ‘The Russian dance is like a folk minuet full of grace and dignity, but livelier, more natural, and less lacking in ideas than the old French dance, which was limited to ornamental postures and bows modelled after the custom of the time.’ Josefa Durán y Ortega, Memoiren der Sennora Pepita, 3 vols (Berlin: Hermann Hollstein, 1854), iii, p. 163.

4 Jean-Michel Guilcher, La Tradition de danse en Béarn et Pays Basque Français (Paris: Editions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 1984), p. 658.

5 Richard Wolfram, Die Volkstänze in Österreich und Verwandte Tänze in Europa (Salzburg: Müller, 1951), p. 23.

6 ‘Zur Oper Don Juan. Kontroversfragen Bezüglich Der Darstellung Auf Der Bühne‘, Morgenblatt Für Gebildete Leser (1865), pp. 772–80.

7 Karl H. Heydenreich, ‘Über Tanz Und Bälle’, Deutsche Monatschrift, May 1798, pp. 43–52 (p. 48).

8 Jan Ling, A History of European Folk Music (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1997), p. 192.

9 Julia Sutton, ‘The Minuet: An Elegant Phoenix’, Dance Chronicle, 8 (1985), 119–52 (p. 151).

10 Horak, Karl, Treskowitzer Menuett, 2021 vols. (Dancilla, 2020) https://www.dancilla.com/wiki/index.php/Treskowitzer_Menuett

11 The following dance titles appear in Lidové Tance z Čech, Moravy a Slezska, 10 vols., directed by Zdenka Jelínková and Hanna Laudova (Strážnice: Ústav lidové kultury ve Strážnici, 1994).

12 Fritz Kubiena, Kuhländer Tänze Dreißig Der Schönsten Alten Tänze Aus Dem Kuhländchen (Neutitschein: Selbstverl. d. Hrsg., 1920).

13 Tilden Russell and Dominique Bourassa, The Menuet de la Cour (Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 2007); Egil Bakka, ‘Typologi og klassifisering som metode’, in Nordisk Folkedanstypologi: En Systematisk Katalog Over Publiserte Nordiske Folkedanser, ed. by Egil Bakka (Trondheim: Rådet for folkemusikk og folkedans, 1997), pp. 7–16; Yuen-Ming D. Yih, Music and Dance of Haitian Voudou: Diversity and Unity in Regional Repertoires (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Wesleyan University, 1995).

14 Egil Bakka, ‘Dance Paradigms: Movement Analysis and Dance Studies’, in Dance and Society: Dancer as a Cultural Performer, ed. by Elsie Ivancich Dunin, Anne von Bibra Wharton, and László Felföldi (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2005), pp. 72–80 (pp. 73–74).

15 Egil Bakka, ‘Revisiting Typology and Classification in the Era of Digital Humanities’, Arv, 75 (2019), 153–79 (p. 168).

16 Bakka, ‘Dance Paradigms’, p. 74.

17 One same-hand fastening is to hold hands left in left or right in right.

18 Jean-Michel Guilcher, La contredanse et les renouvellements de la danse franc̦aise, Études Européennes, 6 vols. (Paris: Mouton, 1969).

19 Michel de Pure, Idée des spectacles anciens et nouveaux. Des anciens: cirques, amphitheatres, theatres, naumachies, triomphes. Nouveaux: Comedie, mascarades, exercices et reveuës militaires, feux d’artifices, entrées des rois et des regnes (Paris: Michel Brunet, 1668).

20 Michel Brennet, Dictionnaire pratique et historique de la musique (Metronimo.com, 2003) https://dictionnaire.metronimo.com/index.php?a=print&d=1&t=5615

21 Thoinot Arbeau, Orchésographie: Méthode et théorie en forme de discours et tablature pour apprendre à danser, battre le tambour (Geneva: Editions Minkoff, 1972).

22 Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Claude Dauphin, Le Dictionnaire de musique de Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Une edition critique (Bern: Peter Lang, 2008), p. 425.

23 Sebastian de Brossard, Dictionnaire de musique contenant une explication des termes Grecs, Latin, Italiens & François les plus usitez dans la musique (Amsterdam: P. Mortier, 1710), pp. 203, 212, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8623304q

24 Bruce Haynes and Robin Spencer, The Eloquent Oboe: A History of the Hautboy 1640–1760 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 45.

25 Ibid., p. 53.

26 J. B. P. Molière, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme. Comedie-ballet. Faite à Chambort, pour le Divertissement du Roy (Paris: Suivant la Copie imprimée, 1681), p. 108.

27 Jean-Michel Guilcher, La Tradition Populaire de Danse en Basse-Bretagne (Spézet: Coop Breizh, 1997).

28 Philippa Heale, ‘Seguidillas’, in International Encyclopedia of Dance, 6 vols. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), vol. 5, p. 565.

29 Egil Bakka, ‘Innleiing. Turdansen i Folkedansarbeidet’, in Klara Semb, Norske Folkedansar: Turdansar (Oslo: Noregs boklag, 1991), pp. 17–58; Henning Urup, Dans i Danmark: Danseformerne ca. 1600 til 1950 (København: Museum Tusculanum, 2007), p. 141.

30 Mirko Ramovš, Polka je Ukazana: Plesno Izročilo na Slovenskem. Od Slovenske Istre do Trente, 2 vols. (Ljubljana: Kres, 1998-1999), 2, pp. 214–51.

31 Guilcher, Jean-Michel, La contredanse et les renouvellements de la danse franc̦aise (Paris: Mouton, 1969), p. 24.

32 Charlotte-Elisabeth Orléans and Malte-Ludolf Babin, Liselotte Von Der Pfalz in Ihren Harling-Briefen: Sämtliche Briefe Der Elisabeth Charlotte, Duchesse d’Orléans, and Die Oberhofmeisterin Anna Katharina Von Harling, Geb. Von Offeln, Und Deren Gemahl Christian Friedrich Von Harling, Geheimrat Und Oberstallmeister, Zu Hannover (Hannover: Hahn, 2007), pp. 792–93.

33 Ibid., p. 24.

34 Ibid., p. 233.

35 Ibid., p. 170.

36 Philip F. Riley, A Lust for Virtue: Louis XIV’s Attack on Sin in Seventeenth-Century France (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2001).

37 Orléans and Babin, p. 197.

38 ‘Relation des rejoissances publiques’, Gazette, 1 January 1722, p. 153.

39 ‘De Versaille’, Gazette, 29 October 1757, p. 542.