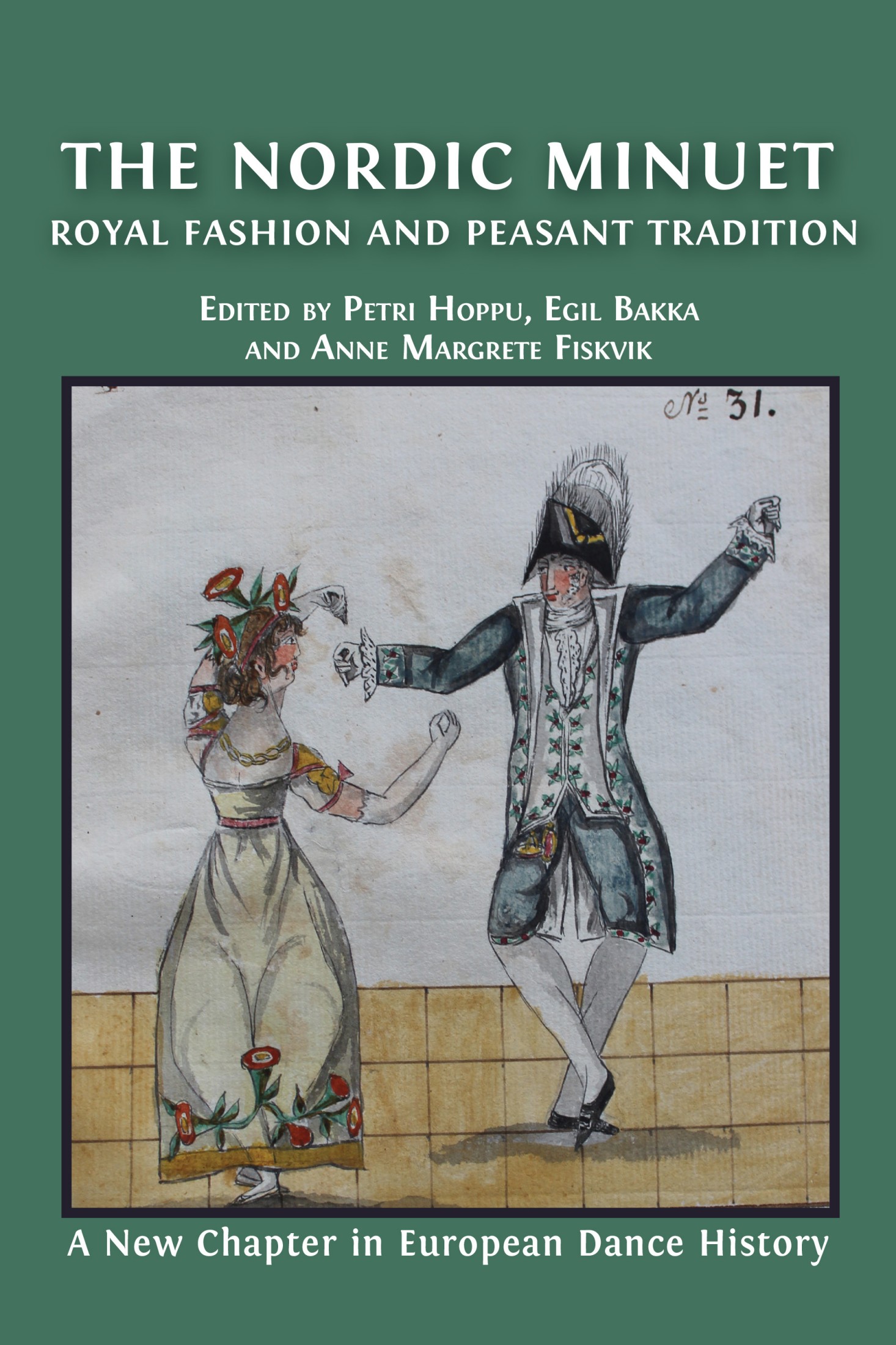

6. The Minuet in Finland after 1800

©2024 Gunnel Biskop, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.06

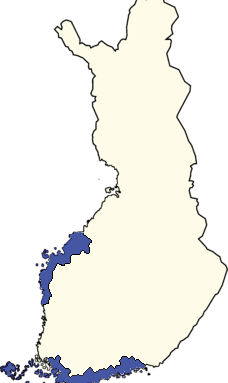

Until 1809, Finland was part of Sweden. After the war between Sweden and Russia 1808–09, Finland became an autonomous grand principality under the Russian Empire until 1917, when Finland became independent. Until 1863, Swedish was the only official language in Finland, but since that year both Finnish and Swedish have been national languages. The majority of the Finns speaks Finnish. The Swedish-speaking population mainly reside on the coasts—along the Gulf of Bothnia and the Gulf of Finland—and toward the west in Ostrobothnia, southwest Turku and Åland, and southern Nyland (in Finnish: Uusimaa). Among the Swedish-speaking population, the minuet was and, in some parts of the country, continues to be a vital dance. By contrast, the minuet among the Finnish-speaking population was of lesser significance and fell out of use. In the following chapter, I will discuss the minuet among these language groups separately.1

The Minuet as a Common Dance among the Swedish-speaking Population in Finland

I will begin with the minuet of the Swedish-speaking population in Finland. Focusing specifically on the minuet of ‘ordinary people’ or the rural population, I will distinguish between the minuet as a common dance in society and the minuet as a ceremonial dance at weddings.

Fig. 6.1 The Swedish language area in Finland marked in blue. In the west Ostrobothnia, in the southwest Åland and Åboland, in the south Nyland. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Svenskfinland.png, CC BY-SA 3.0.

In Sweden, the minuet began to fall out of use among the upper class in the early 1800s, and the situation was the same in Finland. In Finland, this is shown in detailed diaries where many dances are mentioned, but not minuets. However, the dance teachers continued to have the minuet on their repertoire for a long time. In 1805 a dancing master at The Royal Opera in Stockholm, G. C. Drellström, arrived in Turku and taught ‘minuets, quadrilles, waltzes, anglaises, and ballets and solo dances’ in the city and the countryside. Some dancing masters had minuets in their repertoire, insisting that learning helped achieve a good body posture. A German dance teacher Adolf Meyer taught the minuet in addition to modern dances in 1835. An Estonian dance teacher Caroline Tyrong mentioned four years later, in 1839, that she taught the minuet and usual dances. She specifically taught children to dance. A Prussian dance teacher Theodor Georges taught in Borgå for a month ‘Kachucha, Polka, Mazurka, Redova, Contre Dance, Minuet, Vals, etc’ during his trip to St. Petersburg in 1849.2

Although the minuet was no longer a common dance among the upper class, the upper class could still dance the minuet in the nineteenth century, even as late as in the 1850s. One example is from Zacharias Topelius in Nykarleby, who wrote of dancing minuets and polskas at weddings of ordinary people in 1840. According to his account, older men and women in Nykarleby could still dance the minuet until the wee hours of the morning. Another example comes from Western Nyland, where the upper class at Fagervik danced the minuet in 1859.3

Fig. 6.2 Peasant wedding in Ostrobothnia in Finland, c. 1808. Watercolour by C.P. Elfström. The Finnish Heritage Agency, Finland, https://finna.fi/Record/museovirasto.1F90D360E232F5D63D90BE41B6A1E749, CC BY 4.0.

The collapse of the minuet’s popularity took place throughout Europe, although in Germany, for example, attempts were made to revive it at the end of the nineteenth century. According to a Finnish newspaper, German dance teachers had already taken the first steps and made a publication in which the teachers were invited to work on reviving the minuet and gavott, which had already been taken up by the German imperial court. But, the text continued:

However, a simplification of these dances is predicted since, in their old condition, our dance audience would consider them tiresome, stiff, and too challenging to learn. The minuet that has been proposed is ‘menuett à la reine’, but with the change that the steps, which in the old form of the dance would form a Z, are exchanged, due to the large space their execution requires, for a single traverse with a change of place.4

The German court began to dance the minuet again. In Finland, this resurgence did not occur, however; the same belief—that the steps were challenging to learn has been—is seen throughout the Nordic region.

Among the rural population, the minuet has been danced in all parts of Swedish-speaking Finland. As an ordinary dance, the minuet was danced at everyday dance events and weddings after the ceremonial dances when all the wedding guests were allowed to dance. For many years, the minuet has been featured in popular tradition in Ostrobothnia in Vörå–Oravais–Munsala–Jeppo–Nykarleby, and in Lappfjärd and Tjöck. In these regions, many minuets were also danced as ceremonial dances at weddings. In other parts of Ostrobothnia—from Närpes to Korsholm and from Pedersöre to Karleby—as well as in Nyland, the archipelago of Turku, and Åland the minuets fell mostly out of use in the 1860s and 70s; however, it did remain in prominent use in some regions until the 1890s.

The ‘Table End’ and Its Meaning

As a part of the minuet dance formation, Finnish-Swedish descriptions often mention ‘table end’, which comes from the wedding context and refers to the table behind which the bride and bridegroom sat at their wedding. The minuet is danced in a longways formation, with women and men opposite each other. The couple who stood closest to the bride’s table were called ‘table-end couple’, and the ‘table-end’ man had a role in leading the dance. He was required to know at which point of the music the dance should begin, which, according to a male informant in Oravais in Ostrobothnia in the 1990s, was the hardest thing about the whole minuet. The leader, also, was supposed to decide how many times one changed places with one’s partner before one proceeded to the middle figure. The length of the minuet was not specified in the vernacular tradition. The ‘table-end’ man would also know when to give a signal to indicate the figure change. These signals varied in different regions. In Lappträsk in eastern Nyland, one said ‘good midday’ in Nagu; in Turku archipelago, men raised their hand; and in Ostrobothnia they stamped or clapped their hands. In some parishes in Ostrobothnia, the men made a series of stampings before clapping. To know when the stampings were to begin, different signals, again, were used depending on the village: sometimes it was a single stamp by the leader, in others it was by all or some of the men clasping hands.

After the turnaround in the middle of the minuet, the dance continued as before. To know when the dance would end, the signals were repeated. In Lappträsk, one said ‘good evening’, and, in Nagu, men raised their hand again. In Ostrobothnia, the sign was given by more stamping and clapping. There were also different ways to finish the minuet. Couples could pull down their joined hands twice before releasing them, or they could make a circle with the hands.

How long the music commonly played while couples were setting up, before the dance started, varied. From Vörå, it was reported that the musicians played the first reprisal twice, prompting the pairs to stand up. From Oravais, it appears that sometimes the music played longer and sometimes a shorter time before the dance began. In the 1940s, the melody was played once through. From Purmo, a statement suggests that dancers were to get in place while the music played first reprisals. In Jeppo, one found one’s place in the line before the minuet music started and left the dancefloor before the Polska music started. From Tjöck and Lappfjärd, accounts suggest that dancers moved to the floor while the musicians played through the melody.

If there were many people participating in the minuet and several longways formations were needed, there was still only one man in the first row who led the dance. This model suggests that there was a kind of ranking in minuet dancing—one based not on social position but the ability to dance. When the minuet was followed by a polska, the leader decided how long it was danced in each direction and when it was supposed to end, stamping as a signal.5

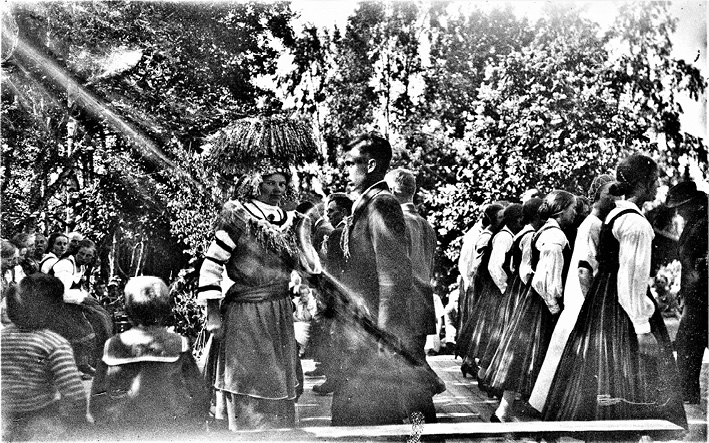

Fig. 6.3 The following images (6.3, 6.4a, 6.4b, and 6.4c) are a unique suite of images from a wedding in Vörå in Ostrobothnia in Finland in 1925. Photographs by Erik Hägglund. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS). In the first image, a wedding procession is seen. The bride has just been picked from the yard where she has been dressed. (ota135_19160), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_ota135_19160?sid=3078898293, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 6.4a The bride and groom. (ota135_19137), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_ota135_19137?sid=3078898293, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 6.4b The wedding guests gathered in the courtyard. (SLS 865 B 263), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_SLS+865+B++263, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 6.4c The minuet is danced, in two lines. On the left is the bride and groom, with the bride wearing a tall crown looking straight into the camera. The young girls in the row on the right are wearing folk costumes that were reconstructed in the village some decades earlier. (ota135_19159), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_ota135_19159?sid=3078898293, CC BY 4.0.

Polska after the Minuet

It was mentioned above that the minuet was followed by a polska. This latter dance will appear many times in my discussion, so there is a reason to briefly outline the phenomenon of what is called a dance-pairing. In Ostrobothnia, Finland, the polska is danced after the minuet even today, and we saw the same pairing above in discussion of the minuet in Sweden-Finland in the eighteenth century. The tradition of dancing the two dances together as first dances at weddings is longstanding in the lower classes. I call this the ceremonial dance or dances.

As a common dance of the upper class in Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Norway in the 1700s, and in Nyland in Finland, also in the nineteenth century, these dances were not paired together. Instead, the minuet and the polska were two separate dances that were danced independently of each other, even if they were danced at the same event. On the other hand, among the rural population, the minuet could be followed by a polska. For example, this pairing of ceremonial dances is what we see during weddings in Sweden, Finland, and Denmark from the mid-eighteenth century.

During the ceremonial dances at weddings of ordinary people, two dances were danced. When the polska followed the minuet in the ceremony, there was a natural break between the dances, when the bride was handed over to the following person who would dance with her, or when the gift would be given over to her. These involved a process of ‘handing over’—both the bride to the following person who would dance with her and a gift to the bride, such as a silver spoon or money. Originally, two polskas were danced in this case, and the handover took place between the two polskas. When the minuet became popular in the latter part of the eighteenth century, it took the position of the first polska, while one would still dance the second polska as before.

There is some evidence that a polska did not always follow the minuet in the ceremonial dances. This might be the case when the priest danced with the bride. The priest, who had wedded the couple, did not give any gift. The priest had another function: he had, according to popular beliefs, a protective effect against evil beings who might attack the bride, who were thought to be exposed to evil spirits.

In the area of Ostrobothnia with a Finnish-speaking population, the tradition of giving the bride a gift in the form of money during an intermission between the two dances persisted into the 1840s. Even after this custom faded, however, the minuet and polska continued to be danced one after the other. We often see in vernacular culture that customs and practices survive for a long time, even when people cease to remember or never knew their meaning. These dance traditions survived at weddings—and especially within the ceremonial dances—before they were utterly forgotten.

Today, minuets and polskas are danced consecutively, almost as one dance, in Ostrobothnia, a tradition which began in the 1950s when folk-dance groups began to perform the minuet. The intention was to prevent the audience from applauding after the minuet.

The various polskas that were danced after the minuet were structurally different. In the northern parts of Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia, two couples typically danced together with crossed arms and making polska steps clockwise and anti-clockwise. The number of couples who danced together could vary. In the southern parts of Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia as well as in Nagu in the Turku archipelago, the polska was danced both in couples and in big circles with several dance patterns following each other.6

Fig. 6.5 The men in Ostrobothnia in Finland are perhaps on their way to a dance evening, 1922. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. Ostrobothnian tradition archive 135. SLS 865. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_%25C3%2596TA+135+foto+20093, CC BY 4.0.

The Minuet—the Favourite Dance—in Ostrobothnia

A schoolteacher named Johan Hagman (b. 1858) from Munsala, wrote a colourful description of a common dance event in Christmastime in Ostrobothnia in the 1880s. He depicted popular customs and practices, giving a clear picture of a regular dance event with coffee, alcohol, food, and dance. The dance lasted for three days. Hagman wrote:

On Christmas day, nothing was done. One went to church, looked pious, ate oven porridge and pancake for dinner, and slept well all afternoon. But two days later, just after dinner, one saw one crowd after the other, young boys and girls, go to the gathering place, the girls dressed in checked woollen dresses and muslin scarfs, the boys in their best holiday clothes with feathers in the cap, long-necked pipes in their mouths and the tassels of the tobacco pouches hanging a half cubit out of the pocket. Terrible congestion soon arose in the cottage. It all resembled a fat dead mass, each stood there and looked stupid, and the boys whiffed with ‘feel on the tobacco’ mixed with lavender flowers so that the cabin was filled with clouds of smoke.

The youths hired a cottage for the dance event and asked two musicians to perform. The place was crowded, and after the musicians had rosined their bows and tuned their strings:

One, two, three, a fresh minuet starts. Now the rigidity is gone, now there is life and movement in the mass, and in the wildest hurry, anyone, who can use his elbows to get to the table end, grabs a girl and stays in a line. They stand in two long rows against each other, the girls in one, the boys in the other, and wait for a suitable stroke of a violin to start dancing. So—a stamp of the boys, a swing with the arms, and—the minuet is in full swing. When this is over, a roaring polska follows, then a new minuet with a polska and so on in infinitely [...] one minuet and polska takes over another with a lot of stamps and handclaps. Those who do not have room to dance spend their time with jokes and cheerful conversation and express their opinion either admiring or criticizing any of the dancers. Due to the heavy congestion, it is almost impossible to stand still. One needs to move, and the whole mass is moving, and everyone is pushed forward like cogs in a wheel.7

The quote mentioned that the boys ‘at the wildest speed’ would reach the table end, honorary place. It was an honour to stand at the table end. The minuet was the favourite dance in Munsala, followed by the polska, but no one knew or remembered why.

Even in Vörå, the minuet was the most beloved dance at the same time. A sensual description of the minuet as a common dance at a wedding in Vörå was included in a novel by Hugo Ekhammar (b. 1880). Ekhammar was born in Helsinki, but he had seen people dancing the minuet when he was the principal of Vörå Folk High School 1907–08. He did not write about how the dance started at the wedding but started his account at the point at which everyone got to dance.

Ekhammar wrote enthusiastically about how the cottage had been decorated as a wedding hall as well as about the bride and the common dance:

The walls were covered with white sheets, the oven with white paper. There were two, three large mirrors on each wall, which reflected the moving mass on the floor. In the middle of the ceiling appeared the wedding cloth, made of a white sheet and a black side cloth inside, angled with this and with the fringes hanging down as well as from the sheet. Three wide-screen lamps hung on the ceiling and threw a clear shine over the tightly packed, sweaty human mass who danced and hopped a minuet in the crowd, partly stood on the floor and on the wall-mounted benches, where some also sat down in holes, formed between those who stood around them.

The tall crown of silver and golden brass on the proudly arrayed bride’s head made her the tallest of all, and taller, jollier, wilder than the other dancing women, she jumped and stepped towards her friend after the tones of the two musicians’ fiercely rubbed strings. To meet her, the groom stepped proudly and smiling in the dancing men’s line, which rolled back and forth, turned to the side and returned, met and crossed over through the rolling women’s lines and turned and continued in a constant wave-like motion. At a particular moment, the men stamped fiercely with their boots and clapped their hands with a huge bang. The floor swung violently with the dance, and the door to the potato store was kicked off by a heel or toe and must be guarded so that no one would fall into the black depth. The minuet ended with a swirling polska, danced in groups of four persons so that the brilliant brass lilies in the breasts seemed united to a golden wreath. [After the polska, other dances were danced.] But then, again, one wanted to dance the minuet, the dear dance, and again the men’s and women’s lines rolled against each other, crossed over, and swelled back to meet each other again.8

From Ekhammar’s description, it is apparent that minuets were popular in Vörå in the 1910s. One also gets a good picture of how the dance progressed with participants crossing over to the opposite sides of the formation and of the men’s great stamping and clapping, which signalled different stages of the dance. Ekhammar called the minuet ‘the loved dance’.

Fig. 6.6 Musicians in Vörå in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1922. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. Ostrobothnian tradition archive 135. SLS 865. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_ota135_19707, CC BY 4.0.

Ekhammar also wrote that the bride ‘jumped’ and ‘stepped towards’ her partner, movements that can be interpreted as pertaining to the minuet. When the dance researcher Yngvar Heikel documented dances in Munsala in 1927, he learned that the minuet was danced with fast hopping steps. In Jeppo, we see the same: it was stated that one hopped in the minuet. People talked about the ‘hop minuet,’ and the hop steps took place during counts 5–6 and 1–2, while at 3 and 4 one took walking steps, the whole minuet through.9 In Jeppo, dancers even hopped in place before the minuet is started. According to an informant I interviewed in the 1990s, the minuet with hop steps was more used during the first years of the twentieth century than in the 1920s. According to another informant, ‘the old’ had said that they began to dance with hop steps in the minuet in the 1920s. In the 1930s, people often danced, or ‘stepped out’ the first half of the minuet and hopped the other half. Professor Lars Huldén, a well-known writer who was born and raised in Munsala, confirms this. He wrote, ‘In Munsala, the minuet was often danced with hop steps during the other half of the dance, after the turning with hand in hand, with the order of the steps right, right, left, right, left, left’. This same phenomenon, wherein participants hop-stepped the second half of the minuet after the turning in the middle of the dance, is still practised by Jeppo dancers today.

The popularity of the minuet was witnessed by Yngvar Heikel, who was invited to a wedding in Jeppo in 1927, during his dance collection fieldwork. Heikel wrote that the minuet was so dominant that almost every dance was a minuet or polska. He also described the beginning of the minuet: ‘Immediately when the music started, some thirty pairs rushed and set themselves in the line, because everyone wanted to get as close to the bridal couple as possible’. The bride always danced at the table end, and everyone tried to get to that direction.

In Kvevlax and Maxmo, the minuet was danced until the twentieth century. In Kvevlax, a source in 1932 stated that one danced the minuet, quadrille, slätvals [smooth waltz], polska, and singing dances at Christmastime events. Another informant (b. 1877) gave the following information about the common dance at a wedding in Kvevlax:

On the second afternoon at wedding those young people danced the minuet opposite to each other who had flirted with each other the night before [...]. This dance was followed with great curiosity by all. One would like to see who had flirted with each other and maybe become a couple.

In Maxmo, the minuet was also danced at the same time and is said to have forgotten by 1924.10

Fig. 6.7 Schoolgirls in Tjöck in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1907. When Otto Andersson was on a music recording trip in Tjöck in 1904, he was surprised that the people then still used the old costume. Photograph by Ina Roos. The Finnish Heritage Agency, https://finna.fi/Record/museovirasto.CA8EAA998D5E25E69490C69C7AEFC234, CC BY 4.0.

In southern Ostrobothnia in Lappfjärd and Tjöck, the minuet was the main dance when a folk music researcher Otto Andersson (1879–1969) documented folk music in the region in 1904. Andersson took part in a local dance event called ‘oppsito’ in Tjöck, and he was astonished over its structure and repertoire. A significant number of the girls were dressed in local costumes, which was still a common practice in Tjöck.

Fig. 6.8a People in Tjöck in Ostrobothnia in Finland in harvest work, 1890. Photograph by Ina Roos. The Ostrobothnian tradition archive. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+146_ota146+foto+459, CC BY 4.0.

Fig. 6.8b Adolf von Becker, Dance Rehearsal (1893). Finnish National Gallery, https://finna.fi/Record/fng_nyblin.WSOY_S_IV_4-70,_25, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Andersson was also surprised that older people also participated in ‘oppsito’ and that the participants had brought something to eat that was shared during the evening. Moreover, he was astonished by the dance repertoire: ‘the strange thing about it was that there were almost no other dances than minuets’. He continued:

After the first minuet, I was expecting something else. But new minuets followed one after the other, only occasionally alternating with other dances. When I wondered if the dance continued like this only to demonstrate the minuets for me, I was told that ‘oppsitona’ used to go to just this way in this village. If the dances were somewhat uniform—though captivating enough by the style’s rarity—then the melodies were varied. The musician here, like elsewhere, puts an honor in favour of a rich repertoire.11

Andersson, born on Åland where the minuet had been discontinued, felt that the minuets were ‘somewhat uniform’. It is hard to say whether he meant they were similar or repetitious. The latter is more likely since he specifically comments that the melodies were varied. As an ‘outsider,’ he may not know that the minuet is danced in particular ways in particular villages. It is also interesting that Andersson, who was travelling to record folk music and subsequently saw the youngsters dance did not mention anything about the polska having been danced after the minuet. Thus, his accounts suggests that the polska was not danced after the minuet at everyday dance events.

Fig. 6.9 A wealthy peasant’s farm in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1910–1960. Photograph by Erik Hägglund. SLS 865 B 473. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+135%252C+SLS+865_SLS+865+B+473, CC BY 4.0.

In the northern parts of Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia, in Karleby, Kronoby, Nedervetil, Terjärv, Larsmo, and the town of Gamlakarleby, the minuet was common until the 1870s, when the purpuri [potpourri] became the main dance. A woman (b. 1839) from Kronoby explained that at everyday dance events, in the mid-1800s, participants danced ‘all night, polska and minuet’. About the common dance at weddings, she said:

The first day, girls and boys danced ’with money’ with the bride, the other day, old men and women. One danced the polska — when the bride often wore out a couple of shoes — and minuet. When this dance ended, the bride would dance with goblets, big silver cups with drink, and sprinkle it on the guests [...]. One danced mostly polska and minuet — not purpuri.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the minuet was replaced by the purpuri. In 1893 in Kronoby, it was said that ‘in the past polskas and minuets were danced, but now the most common is purpuri, a dance with 6–8 figures, then polka and schottische’. Similar information comes from Terjärv, where the purpuri was replacing the ‘minett’ in the 1870s. In Gamlakarleby, it was said in the 1880s that the minuet had previously been the most common dance. Although the minuet was no longer danced there when Yngvar Heikel collected dances in the 1920s, there were people in the region who still knew it.

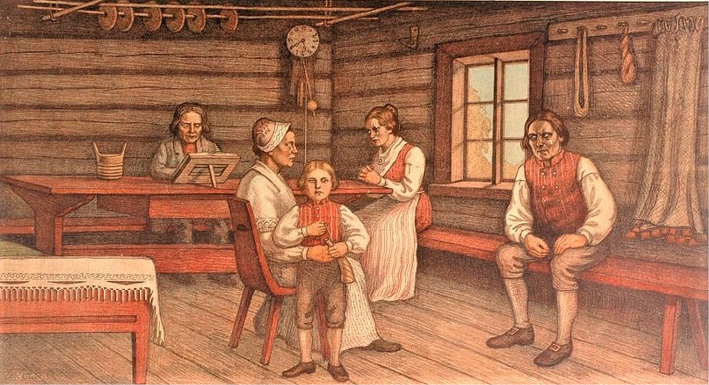

Fig. 6.10 Interior from a farmhouse in Oravais in Ostrobothnia in Finland. Photograph by Valter W. Forsblom (1916). SLS 269_19. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.SLS+269_SLS+269_19, CC BY 4.0.

In Larsmo, the minuet was still danced in the late 1800s, but the purpuri eventually became the main dance. The minuet had been introduced in Larsmo at the end of the eighteenth century at the latest. This is evidenced by Eric Gustaf Ehrström’s diary from 1811, which I shall examine in more detail in connection with the minuet’s various forms. In 1929, a female informant in Larsmo (b. 1846) explained that, at the wedding, the dance began with what was called ‘rosan’, and minuets were danced later. She wrote:

But after the rosan there was common dance, purpuri, polkamazurka, and waltz until the evening meal […]. On the third day, the closest relatives and acquaintances enjoyed themselves. They danced polska and minuets, the bride dancing with the groom’s father and the groom with the bride’s mother. All the old ones were on the move.

The ‘rosan’ was the initial part of the first purpuri at the wedding, and only it appeared in the first purpuri. It was danced only by the young people who made up the wedding party—the pällhållare [bridesmaids and groomsmen]. The minuet was still danced, but, interestingly, the dance of the bride and the groom’s father and the groom and the bride’s mother did not take place until the third day of the wedding celebration.

In central Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia, especially in the region surrounding Vasa, the minuet disappeared earlier than elsewhere in this region. In the Replot archipelago, for instance, the minuet fell out of use as early as in the 1830s. Carl Johan Roos (b. 1815), who was the priest of Replot 1855–79, wrote in 1872 about weddings: ‘The waltz has not yet become common and the minuet, this solemn dance, has disappeared more than fifty years ago. The wild polska keeps its place from the beginning to the end’. Roos was born in Kristinestad, near to Lappfjärd and Tjöck, so he knew what kind of dance the minuet was. When he spoke of the ‘solemn dance,’ he would probably have experienced the minuet as the first dance at a wedding in his native city. An early twentieth-century folklore researcher in Repolot, Wilhelm Sjöberg, also stated that, in the 1890s, the minuet no longer occurred in the region around Vasa.12

Fig. 6.11 Folk dancers in Helsinki perform a minuet from Vörå in Ostrobothnia in 1932. The man to the left dances at the ‘end of the table’ and has the leading role in the minuet. Photograph by Rafael Roos. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

In Pedersöre, Purmo, Esse, and Vörå, the people danced minuets up until the twentieth century; and in Nykarleby, Jeppo, Munsala, Oravais, as well as in Lappfjärd and Tjöck, they continued almost into the present. To these parishes, I will return with regard to the ceremony of weddings, where the minuet had a significant role.

|

|

Fig. 6.12a and Fig. 6.12b Tradition bearers from Munsala in Ostrobothnia in Finland have dressed in folk costumes to present their minuet and polska in Stockholm in 1987. Photographs by Stina Hahnsson. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

The Minuet as a Common Dance in Nyland

The minuet has been danced in all Nyland parishes, and some examples are highlighted here. As stated earlier, the minuet was usually called ‘minett’ in this locale. The diaries of the Priest Samuel Ceder (b. 1779) contain several pieces of information about the minuet between 1796 and 1804, in Turku and in Nyland. Ceder was the son of a farmer who lived outside Uusikaupunki in Western Finland. He attended Åbo Cathedral school in 1794 and then continued studying at the Åbo Academy University (Akademy in Turku). In Turku, he went to the dance school led by Fredrik Forsmark, the city dancing master, who we encountered above at Haapaniemi War School. Ceder graduated from the Academy in 1804 and was ordained a priest in Borgå the same year.

Ceder explained that, in 1796, when he was 17, he had been at a wedding in the countryside. There were many people at the wedding, among them the daughter of a wealthy merchant from Uusikaupunki, with whom he danced the minuet. He thus already knew the minuet when he came to Turku, enrolling in the dance school there specifically to learn more ‘modern’ dances. In his diary, Ceder said in 1803 that ‘I began learning the solo steps for the first time, as well as perfecting me in the ordinary steps’. The quadrille was the primary dance in Turku, according to his record. In February 1803, he probably attended dance lessons twice a day since he noted: ‘2 quadrilles in the morning and 2 in the afternoon’. On different occasions, he had danced ‘9 quadrilles’ or ‘eleven quadrilles’. In Turku, the minuet was on the decline.

Fig. 6.13 During a dance evening in Helsinki in 2019, the participants have fun dancing the minuet from Oravais in Ostrobothnia in Finland, with hops. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop. © Gunnel Biskop.

In the spring of 1804, Ceder moved to Helsinge north of Helsinki to take up his position as priest. From here, he visited different villages. In the autumn, he recorded that he had danced the minuet. On 10 October, he attended a wedding, writing that he had danced ‘a minuet with mademoiselle Fredrika and a quadrille with mademoiselle Walberg’. The next day he performed two marriages at the same event: one of the grooms was a dragoon and the other a farmworker. Ceder was invited to wed and dance. He stayed at the wedding until six o’clock in the morning, noting that ‘everyone moved to Sonaby, I also wanted to enjoy myself’. The wedding was celebrated on two different farms. Because he had been invited ‘to wed and dance’, I deduce that he probably danced the first dance with the bride.

On Christmas day 1804, Ceder was invited to a dinner at the home of Lieutenant Sahlstedt, where he danced some quadrilles and minuets. Ceder was not married and wanted to find himself a wife. The lieutenant’s sister, who sat next to him during dinner, looked like his ‘ideal girl’; however, ‘She did not invite me to the minet—but a lieutenant Lind had the luck two or three times—I danced with her a quadrille—maybe a minet as well—at 11 I went back home’. The lady was the partner who was supposed to invite to minuets. Probably, on this occasion, the minuet was danced by one couple at a time.

The following day, Ceder wedded another couple. Along with the church cantor, he was in the wedding yard and wrote: ‘[I] had dinner in Tolkby, at Bökars. Danced a few minuets—I was puzzled if I should go to Qvarnbacka—danced a few more quadrilles’. This wedding also took place on two different farms, and he was unsure whether to go to the second location. The following day, the third day of Christmas, he was in Tavastby. A group of twelve people gathered at Gållbacka. It was ‘quite fun, despite the presence of the reverend’s wife’. He continued, ‘even there was dancing—quadrilles, minuets, polskas, and so on’. Ceder mentioned the quadrille, minuet, and polska by name. His phrase ‘and so on’ may signal that there were also other dances. In 1805, Ceder moved to eastern Nyland and, from this point onwards, he does not write about his own dancing or mention any dances.

The minuet survived in the district of Helsinge well into the nineteenth century. In 1964, two informants born in 1885 and 1898, responding to a questionnaire, described memories in which minuets had previously been danced at a wedding in Helsinge.13

Another diary, written by the thirteen-year-old Jacobina Charlotta Munsterhjelm at Tavastby mansion in Elimäki, shows that the minuet was danced by servants. She wrote a few lines in her diary on Midsummer Day 1800, noting that ‘after we had eaten the dinner, the servant girls danced a polska and some minuets’. The young diarist did not report anything about the music. Maybe the servants sang to their dance. Besides the polska and minuet, the thirteen-year-old mentioned långdans (anglaise), polska, and quadrille. Munsterhjelm does record that she danced the waltz with her relatives on Christmas 1800 in Rantasalmi, a parish considered to be the most progressive in the province of Savo for its adoption of new dance styles.

In Strömfors, the minuet was merely one dance among many others in the 1830s. Of the dance at a wedding, one ninety-two-year-old informant remarked: ‘After the meal, there is a dance in the hall, the “master of ceremonies” first asks the bride to a polonaise. Then follow the polska, old waltz, quadrille, danced very often, as well as the minuet’. She also described related customs, noting that the guests received a drink as well as cheese and bread when they entered the wedding house. Furthermore, the bridesmaids and groomsmen were supposed to consist of at least two couples. They carried burning candles in their hands as they accompanied the bride into the room, one couple walking in front of the bride and the other couple behind. In the neighbouring parish Pyttis, the minuet survived until the 1890s.

Fig. 6.14 Young people in Eastern Nyland in Finland play ‘Last couple out’. Photograph by Gabriel Nikander, 1914. SLS 240_12. Swedish Literature Society in Finland, https://finna.fi/Record/sls.SLS+240_SLS+240_12, CC BY 4.0.

The language scientist Axel Freudenthal gives an eyewitness account of dance from his summer trip to Nyland in 1860. He stayed in Mörskom and wrote that ‘the only pleasure at gatherings is dance consisting of the waltz, Swedish quadrille, minuet, polska, contredanse and so-called Swedish march, and in the summertime, swings as well as singing games under the sky, are the usual amusements’.

Snippets of information from different places suggest that men had their favourite songs for the minuet. For example, in Pellinge in Borgå archipelago, the men ask the musicians to play ‘their melody’ when dancing. This account also shows that the minuet was common in Pellinge.

In Esbo, too, the minuet was a common dance among other dances. The first dance at a wedding was a polonaise. The folklore collector Gabriel Nikander playfully described the following dances, saying that some were beautiful while others were not. Nikander wrote:

After the polonaise, an old waltz followed, then the evening’s first Swedish quadrille, most like stamping, also danced matradura, a mixture of old francaise and väva vadmal [weaving dance]. Sometimes niemanengelska [reel for nine] and minuet, but most old waltz and quadrille. Someone knew the polka and danced it as a ‘free spectacle’, a beautiful dance with figures. Polkamazurka was danced badly, galloped by gentry only.

In Lojo in the 1910s, older dances included minuets, hamburgska and Swedish quadrilles, ‘which sadly have now been forgotten’. According to information from 1918, weddings in Kyrkslätt often involved the following dances: ‘old Swedish quadrille, minuet (in old times), waltz, reel and later niemanspolska [polska for nine]’. A parishioner from Tenala explained in the 1920s that, among old dances, there were ‘purpuri and minuet, which should never have been lost’.14

The Minuet as a Common Dance in Turku Archipelago

Previously, I mentioned that the minuet was danced in Turku since the 1740s; it continued to be danced there throughout the century. In 1797, the town’s annual celebration was scheduled for 24 January, to coincide with King Gustaf III’s birthday, and it was one of the most important events in Turku’s entertainment. Åbo Tidning wrote that the celebration involved a concert followed by dancing, ‘the dance took place, to which Concertmaster Ferling had composed a new minuet and contredanse, and thus [the dance] continued with mutual cheerfulness and ordinary food and drink, until midnight’.

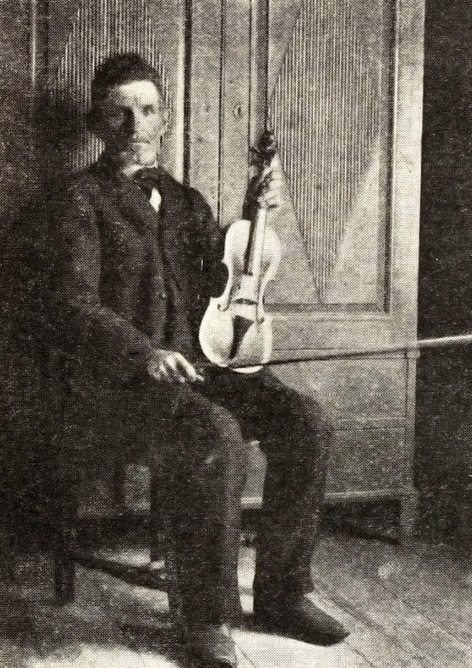

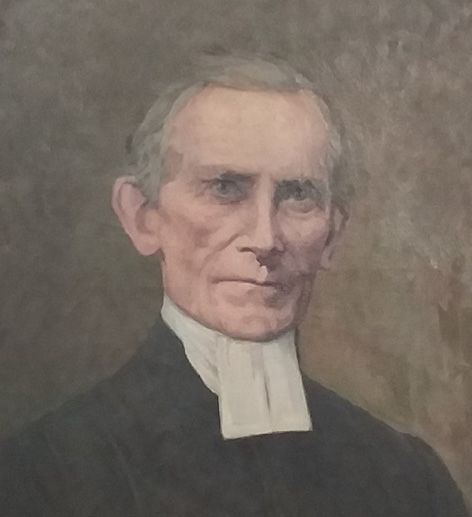

In Turku, Musikaliska Sällskapet i Åbo (the Musical Society in Turku) was founded in 1799. Its members were often students at the academy who, after graduation, moved to other places, bringing their interest in music, melodies, and dances to various parts of the country, including in places that, today, are Finnish-speaking. Andersson created a list of forty pages of members, all of whom could play instruments. One of the violinists in the company’s orchestra was Gabriel Hirn (b. 1782), who became a vicar in Kimito in 1824. Almost every Sunday, Hirn arranged a dance event at the vicarage for ‘the more distinguished youth of the village’. The vicar himself played the violin, and his wife and mother of seven children Hedvig Charlotta (b. 1784), ‘stamped the beat from the bottom of her heart’. Likely, the young people also danced the minuet. How early the minuet came to Kimito is hard to determine. Music had been part of the Kimito Ungdomsförening (youth association) since the 1890s; a local folk musician Gustaf Bohm (1836‒1912) who was active in the youth association indicated that his father, grandfather, and grandfather’s father had all been musicians. His great grandfather, born in 1734, was the most skilled musician. It is hardly too daring to say that the minuet was danced in Kimito in the late 1740s, as it then appeared in the region surrounding Turku and in Åland.

Fig. 6.15 The fiddler Gustaf Bohm in Kimito in Finland was the fourth fiddler in direct descent. Photograph by Otto Andersson. Archive of the Sibelius Museum. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gustaf_Adolf_Bohm_%28Sm_5888%29_%2827113680084%29.jpg, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 6.16 Kimito Ungdomsförening in Åboland in Finland dances its minuet at a summer party, 1904. The schoolteacher Nils Oskar Jansson dances mainly in the row at the ‘end of the table’. Photograph by Otto Andersson. SLS 105b_70. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.SLS+105+b_SLS+105b_70?sid=2972784501, CC BY 4.0.

The minuet was a common dance in the parish of Pargas until the 1870s. From Christmas to January 13, young people divided Pargas into different areas and each was tasked with arranging a dance. During one Christmas season, then, thirteen dance events were held. The assembled company danced ‘polska, minuet and waltzes, in the 1840s quadrilles’. At weddings in Pargas, the dance began with a polonaise. This was followed by the minuet, quadrille, and ‘triman-English’ (reel for three). Later came the waltz, polka, and stigare (schottische).15

The minuet was also danced on the islands of the Turku archipelago. In Korpo, the minuet was a common dance during the 1840s. Lars Wilhelm Fagerlund (1852-1939), a later medical doctor and governor of the province of Åland, wrote in his account of wedding customs in 1878 that dancing began when the meal was finished. One danced ‘in particular polska, waltz, minuet, schulsa, pater Mickel, reel, ryska [Russian], maskurát, Gustaf’s skål, song dances among others’.16

In Nagu the minuet was a common dance as well. It was said that in the middle of the nineteenth century, one dance ‘polska, hoppvals [hop-waltz], minuets, sjuls, hamburgska, etc’. Unlike his descriptions of dancing in Esbo, details are lacking in Nikander’s discussion of the minuet in Nagu; however, he did devote attention to other wedding customs.

For example, in 1894, three travellers observed a minuet in Nagu at a common dance event. After the post-dinner coffee was drunk, the dance started with a waltz, and one couple after the other turned around on the bowing floor. Then the polka was danced and after that a quadrille. The travellers expressed a wish to see a special dance, namely the minuet, and this was fulfilled:

A seventy-year-old man, who, during the more lively figures, could barely prevent his gray hair strokes from falling from his bare scalp, brought to dance a silver-haired older woman, who was almost eighty, and the other dancers were no younger than forty years. Figures and compliments were performed as dignified and graceful as ever in Versailles’s lavish salons during the eighteenth century, and this dance was the one whose looks brought us most enjoyment.

This writer knew that the minuet was danced in the village and that it originated in France.

The minuet survived for a long time in Nagu. At the end of the 1920s, Yngvar Heikel interviewed several people who could provide information about it. A woman born in 1854 knew the minuet well, Heikel said, and he was able to prepare a detailed description of the dance based on her account. In Nagu and Hitis, one bowed to the musician when one started the minuet and also when one finished it.17

The Minuet as a Common Dance in Åland

As we discussed earlier, Carl Tersmeden danced the minuet in Åland in the 1740s. The minuet continued to be danced there until the 1870s. According to information from Hammarland in the 1910s, the first dance at a wedding involved the bride inviting the priest to dance. Then, the groom invited the bridesmaids to dance. One danced ‘polska, quadrille (after 1850), sometimes minuet’. Vendla Bergman (b. 1857) in Finström had seen the minuet danced at a wedding in 1868 when she was a child. No information is available about how the minuets were danced here.18

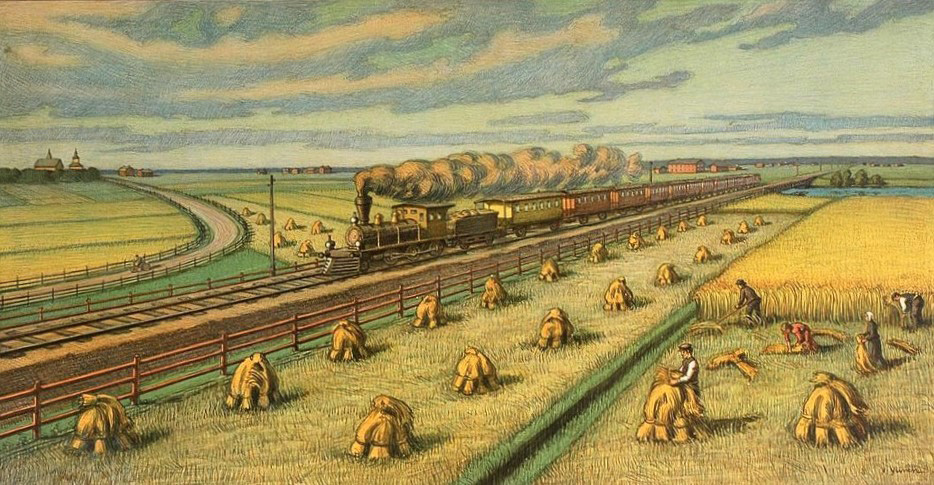

Fig. 6.17 View from southern Ostrobothnia in Finland, school poster by Vihtori Ylinen (1915). Vantaa City Museum, Finland, https://finna.fi/Record/vantaa.Arkisto:281:3, CC BY 4.0.

The Minuet as a Ceremonial Dance among the Swedish-speaking Population in Finland

Dance activities at rural wedding were divided into two parts, consisting of a ceremonial part and a common part. Only certain people participated in the ceremonial part, which was executed strictly according to the traditional scheme. These initial ceremonies were entertainment but also an integral part of the marriage ritual, incorporating the bride and groom into a new community as a married couple. Thus, the ceremonial dances were also understood as a duty. When these were complete, the dance became ‘common’, that is, all the wedding guests were allowed to dance. During this second part, all had a chance to dance with the bride.

I will use the term ‘ceremonial dance’ for the first dance or dances of the wedding.19 Rural people did not use this name but called them, among other things, ‘duty dances’. This implies that certain people were obliged to perform these dances. Rural people also refer to the pällhållardansen, ‘the pällhållar dance’, or ‘the dance of the pällhållare when describing those danced only by the pällhållare in the ceremonial part of the wedding. Some people speak of the fördans and the föredans, meaning the initial or fore-dance; these terms, in my view, indicate that these were dances that were danced before the ‘common dance’ when all the wedding guests were allowed to participate. However, there was much variation in these customs.

Participation in the ceremonial dances varied depending on the parish and even the village, and these rituals took different forms at different times. As well as the bride and groom, the priest, the ‘master of ceremonies’ (host), the maid of honour, parents, relatives, bridesmaids, and groomsmen could attend. In Ostrobothnia, bridesmaids and groomsmen were called pällhållare in Swedish, since they hold a scarf or a kind of a baldachin, which was called a päll above the couple during the wedding ceremony. These were the bride’s and groom’s unmarried relatives and friends, and the group originally numbered eight (four boys and four girls) but the practice later expanded to include more. The bridal couple decided the dancing partnerships in advance, and they also pre-determined which couple would be the primary, most honoured, one. Thus, there was also a ranking among the pällhållare, mainly based on family relations. The ‘master of ceremonies’ was the one who delivered the welcome speech. He decided where the guests would sit and controlled when everything should begin. He also made sure that the food was on the table and that the ceremony was followed carefully. As often still happens today, the maid of honour was the one who dressed the bride and was her helper during the wedding.

According to several pieces of information, the priest danced the first dance with the bride, and then the priest symbolically handed the bride to the groom. It is possible that the first dances with the priest were construed as a religious rite rather than mere dancing. The presence of the priest also had another meaning, namely, to protect against evil powers. Some accounts mention that the priest must attend the first dances for the marriage to be considered finalized.

Fig. 6.18 Adolf von Becker, By the Hearth, an Ostrobothnian Courting Scene (1871), oil. Finnish National Gallery, https://finna.fi/Record/kansallisgalleria.5C435246C4784C3647D65AE63EED596D?sid=2972798628, CC0.

Features, Characteristics, and Conditions of

the Ceremonial Dance

The symbolic function of the ceremonial dances was to transfer the bride and groom from one status to another: from unmarried to married. In ‘the pällhållar dance’, the bride’s and groom’s unmarried female and male relatives and friends danced in honour of the bridal couple. This could also be interpreted as a fertility rite. At the same time, the pällhållar dance distinguished the married couple from the unmarried youth—the bride and groom could never again participate in the pällhållar dance. The ceremony was a farewell, when parents and the closest family danced with the bride and groom. At the end of the wedding, in the so-called polska circles, which I do not deal with here, the new status often was visibly conferred on the bridal couple. This might be expressed, for example, in a change of attire or a change of the name of the bride and groom on the following day. The ceremonies’ ultimate goal was to ensure that the bride and groom would be happy and that the couple would achieve prosperity and success. For them to be well, the ceremonies must be executed correctly and proceed according to the tradition. Because the meaning of a wedding ceremony must be upheld, villages would not risk a negative outcome by deviating from established patterns?

The minuet, as the first ceremonial dance, was characterized by solemnity. This often meant it was danced slowly, as the priest Carl Johan Roos observed in Replot, Ostrobothnia, in the early 1870s. The ceremonial minuets included courteous bows and curtseys, and the ritual was conducted with great seriousness and reverence. Consequently, modifications were made to make it a somber dance. In Tjöck, for example, the boys did not clap their hands during the minuets, but the leading dancer gave a signal in the middle of the dance only by snapping his fingers. Even during the following polska, no stamping was permitted. Otto Lillhannus stated that, in Lappfjärd during his grandfather’s time around 1850, the minuet was so slow that ‘the young people had difficulties [in order] to follow the rhythm of the music’.

The different tempos of the minuet distinguished its uses as a ceremonial wedding dance and as a common dance. With this reason in mind, it is easier to make sense of sources’ very different information about the tempo and experience of the minuet. The slowness sometimes described may refer not only to the ceremonial dances but also to the bridal procession approaching the church and the bridal couple entering the church. Further, there were strict etiquette rules that elongated the entire proceeding. For example, one would never rush to sit down before the wedding dinner started because nobody wanted to be the first to do so. In their actions, guests were simultaneously conscious of their social positions and extremely careful to honour the ranking system.

Fig. 6.19 Wedding in Lappfjärd in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1907. Photography by Ina Roos. The Finnish Heritage Agency, https://finna.fi/Record/museovirasto.65ED6D94B58047CD314AD99D3D5E4545, CC BY 4.0.

One of the ceremonies’ conditions was economic; it was supposed that families could afford to hold a wedding that lasted for several, usually three to four, days. The ability to comply with this stipulation could be expressed in many different ways, including in the number of wedding days and the number of guests, the lavishness of the food and gifts—clothing and jewellery—given by both host and wedding guests. During his fieldwork, Yngvar Heikel learned that much like the custom today wherein bridesmaids dress in matching colourful attire, in Lappfjärd, for each of the days of the wedding, female participants in the ceremonies wore a different colour of skirt: it was considered inappropriate to wear a blouse that had not been created specifically for a particular celebration. There is also evidence that many rules and customs strictly dictated the rural people’s dress code for these events.

The duration of the dancing also extended the ceremony. Allowing each couple to dance two minuets—the latter one with a twirl throughout the dance before the dance was completed—was a further way of emphasizing prosperity. The whole village was involved in a large wedding with preparations and work of various kinds, including the giving and receiving of gifts. This elaborate process also likely produced competition; if one farm or village showed prosperity by hosting a big wedding, another farm or village may feel that they could not show anything less.

Crucially, the wedding was celebrated in one house, as opposed to the tradition that occurred among those who spoke Finnish in Central and Eastern Finland and Swedish-speaking people in Nyland. There, the wedding was usually celebrated in two houses: first in that of the bride then in that of the groom. The need to move the assembly may have curtailed longer ceremonies.

Another consideration for long ceremonies was the music. A reputable musician would not repeat a tune throughout the entirety of the wedding, which meant that the musicians had to have many minuets in their repertoire. In the parish of Oravais, one report explained that different bridal couples would have different bride minuet melodies. My interpretation is that, as long as a musician had an immense repertoire, there could continue to be many minuets in the ceremony. It was in the musician’s interest to be regarded as reputable and, in the ceremonial dances, he was able to show off his skills.

When performed as a ceremonial dance, the minuet was danced in a series that was modelled on the customs of the seventeenth century. Accounts suggest that there were difference and similarities in how different regions organized the series. Changes were also introduced over time. Yngvar Heikel also painstakingly gathered information about how the dance began at the wedding in the early 1920s. Heikel was careful in his work, and he recorded the order that was followed in dancing the minuets and, often, who danced with whom. Unfortunately, he did not record the method of the invitation system, that is, who invited or picked up whom.20

Fig. 6.20 Tradition bearers from Tjöck in Ostrobothnia in Finland, dressed in folk costume, dance their minuet at the seventy-fifth anniversary of Finland’s Swedish Folk Dance Association in 2006. Photograph by Gunnel Biskop. © Gunnel Biskop.

The Minuet as a Ceremonial Dance in Ostrobothnia

Several detailed descriptions of the minuet as a ceremonial dance originate from Ostrobothnia, where the minuet was practised longer than in other regions. There, ceremonial dances had a significant role. Heikel’s documentation from the early 1920s explains how the ceremony was implemented. Interestingly, his records almost always show that a polska followed the minuet. However, from people who have themselves danced minuets at a wedding or have seen minuets danced, there is contradictory information regarding many instances when the polska was not danced after the minuet, specifically when/if the priest danced with the bride. I have earlier in the text presented my idea of the origins of this phenomenon.

Fig. 6.21 Folk dancers in Helsinki perform a minuet from Vörå in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1932. Photograph by Rafael Roos. © Finlands Svenska Folkdansring.

In Nykarleby

The oldest information about the minuet as a ceremonial dance at a wedding in Ostrobothnia is from Nykarleby in the 1830s. Young Zacharias Topelius wrote about the wedding in his diary, long before he began his novel-writing career. He was attending two weddings of the lower class of society, where the gift to the bride was still made up of money, handed over between two dances, minuet and polska.

One wedding, for a servant of the Topelius family, was held in 1837. Of that event, the nineteen-year-old Topelius wrote the following in his diary: ‘I danced the minuet and polska with the bride and left my Riksdaler [coin], which was the main thing’. Since the giving of the Riksdaler was the most important part of the process, this account shows the dutiful element of the ceremony. After the wedding that had been held for her, the bride expressed her great pleasure that so much money had been given that the whole event was paid for.

Topelius attended a second wedding in 1840 and described an even older custom involving the giving of gifts to the bride. At this event, the bride had been a young woman from the cottage next to Topelius’s home. She wore a high brass crown, and she invited Topelius to join the dance with her, which was the custom at that time. He wrote:

And we danced, Brita and I, a great minuet. And then a polska. These dances then alternated to great and continuous pleasure for the young couple, who, in exchange for their ceremonial bread and schnapps, earned more than 40 Riksdaler during that day.21

At this time, the tradition was still active that guests who ‘paid’ for the dance would be given bread and schnapps. This is a marked contrast to the latter part of the nineteenth century, when the service of alcohol was forbidden at weddings. It is also apparent from this account that the bride invited Topelius to dance, a tradition that dates back to the early-1700s.

|

|

Fig. 6.22 and Fig. 6.23 Minuet danced at a party of an association in Helsinki, 2013. Photographs by Gunnel Biskop. © Gunnel Biskop.

In Munsala and Oravais

Sofia Fågel (b. 1869) told about weddings in Munsala in the 1850s: ‘First the priest danced with the bride, then as a solo by bride and groom, and after that, with pällhållare so that only two couples were simultaneously on the floor’. Fågel did not mention a polska after the minuet, and neither did she specify whether the priest or the bride opened the dance with an invitation, but I believe the priest would have danced the first minuet, as he would have been the highest in rank among the guests. After the dance, the priest handed the bride to the groom, and the second minuet was danced solo by bride and groom. After that, the bride continued to dance with each groomsman, while simultaneously, the groom continued to dance with each bridesmaid in turn, with two couples on the floor at any one time. The bride always danced closest to the bridal table, which meant that every pällhållare boy was at the table end and decided, among other things, the length of the minuet. The number of pällhållare couples was probably at least four, with at least six minuets danced during the ceremony. According to Fågel, this process could last for a few hours. 22

Seventy-five years later, Heikel received information from a wedding dresser Tilda Nyström (b. 1859) in Munsala that suggested significant changes in procedure. She said that the bridal couple danced the first minuet and the polska together, as the only pair on the floor. Then the bridal couple danced with each the pällhållare, corresponding with events in Fågel’s essay: two couples on the dance floor at a time. Finally, the bridal couple and all pällhållare couples danced first the minuet and then the polska. According to Nyström, the priest no longer attended the wedding dances.23

However, according to other sources, at least in Oravais, the priest continued to dance the minuet with the bride. Anders Lundqvist (b. 1851) and his wife Lovisa (b. 1850) told a folklore collector at the beginning of the 1910s that, after the meal, the relatives of the bridal couple relatives would dance the minuet with the bride and groom. They specified who danced with whom and in which order:

3) The groom and the priest’s wife (or the maid of honour)

4) The groom’s parents with the bridal couple

5) The bride’s parents with the bridal couple

6) The closest family

Guests who had not been invited to this part of the wedding arrived at dusk, around eight o’ clock, and they would also dance with the bride. The Lundqvists reported that these guests would pay up to five marks for the dance.

The folklore collector records that the first three minuets were danced by one couple and two couples danced the fourth and fifth minuets at the same time. The ‘closest relatives’ probably continued to dance with the bride and groom, still with two couples on the floor. In the seventh minuet, all the pällhållare couples danced simultaneously, probably with each boy dancing at the table end on his turn. The informants said that the number of minuets was only indicative, ‘in fact, these dances can be expanded to a great number, such as the case today,’ that is, in the 1910s. The minuet was danced as a ceremonial dance in Oravais in the 1950s.24

In Maxmo and Vörå

A son of a farmer from Maxmo, Harald Öling (b. 1901), painted a good picture of the wedding customs and dances of the parish in a paper he wrote at Vörå Folk High School in 1920. It used to be common for the students to write about ‘old times’, providing a wealth of amateurishly collected information. Öling’s information came from interviews with his parents or grandparents. His paper contains details that have not been seen before, namely that the pällhållare were ranked. He wrote:

The bridal couple first danced alone. They danced a so-called minuet. After them, all who had held the päll were allowed to dance in the following order: those who were highest among the pällhållare danced first with the bride and groom. After they had danced, they switched over, so the following couple got to dance. The former took place as the last couple in the lead, and this was repeated until every couple had danced similarly. Then a march was played. The bridal couple left the dance floor then. The pällhållare began to dance in the same way as before until they all danced with each other. A farewell march was also played for them. Now the bridal couple returned to the floor again. Then the closest relatives were allowed to dance with the bridal couple. While this was happening, the rest of the guests enjoyed having a drink, etc. Then it was their turn to dance.

So the first minuet was danced solo by the bridal couple. After that, the bride and groom danced with each pällhållare couple, while the other pällhållare danced simultaneously. What is clarified here is that even the pällhållare danced in a specific order with the bridal couple. Whether the ranking was based on family or social status is not given. After each round, the pällhållare couple who had danced moved to the end of the row, and the bridal couple continued to dance with the following pällhållare couple. When the bride and groom had danced with all the pällhållare couples, the bride and groom left the dance floor during a march, and the pällhållare continued to dance minuets and change partners until everyone had danced with everyone, and all the boys had danced at the table end. Then the pällhållare left the floor with a march, and the bridal couple returned and danced with the closest relatives, probably two couples at a time. This custom of a ‘march out and in’ is rarely mentioned in other sources. According to Öling’s notes, four pällhållare couples danced, parents and some siblings, and thus at least fifteen minuets were danced. This writer does not mention any polska.

In Vörå, the polska appeared as a ceremonial dance in the oldest history. The musician Fredrik Berg (b. 1847) wrote that the polskas were the only dances in ancient times, and the minuet was introduced much later. This is also evidenced by records of folklore traditions in Vörå from the 1910s. An informant born in 1828 mentioned: ‘Bride and groom danced the first dance with each other, then with the parents. Each time, three polskas were danced’. A younger commentator, born 1853, said: ‘The first dance was a minuet, it was danced by the bridal couple themselves, after which the bride and groom were to dance with parents and relatives. After that, the bride danced with all the guests’. A third informant, born in 1892, stated that the bridal minuet was self-evident. It was danced by the bride and groom as the only couple. This was probably followed by a minuet danced by two couples simultaneously. When the guests danced with the bride, any number of couples might be on the floor at the same time.

There are also examples of the minuet as a ‘money dance’, where guests pay for the dance. One woman born in 1848 said: ‘When the dance then took place, one toasted after each minuet. Everyone who danced with the bride gave a coin, the boys 50 pence, the girls 25 pence’. At a wedding in 1887, the dance began with a waltz by the bridal couple:

Then the minuet followed with the couple’s parents. One minuet did hardly stop until a new one was tuned up. Then they kept on until the couple had danced with all the guests. Then it was the milk men’s and uninvited guests’ turn.

In this instance, the minuet with the parents were danced by two couples. How many couples danced at the same time after them was not specified.25

Fig. 6.24 The priest dances a minuet with the bride at the end of the eighteenth century. A detail of a painting from a wedding, Leksand, Dalecarlia, Sweden. Nordiska museet’s archive, Stockholm, all rights reserved.

In Ytterjeppo and Forsby

From Ytterjeppo village, Anna Björkqvist (b. 1872) described the ceremonial dances. She was interviewed by Yngvar Heikel who reported that they not only discussed but danced the minuet enthusiastically and for a long time during their conversation, indicating that Björkqvist was competent in her dance. She explained that there were often ten pällhållare couples, and that the ceremonial wedding dances proceeded in this order:

- A minuet and polska were danced by the bride and groom alone, they danced solo.

- A minuet and polska were danced by the bride and pällhållare boy No. 1 and by the groom and the girl No. 1. The two couples were simultaneously on the floor.

- A minuet and polska danced by the bride with the boy No. 2 and the groom with the girl No. 2, still two couples on the floor.

- Then the bride and groom continued to dance with all the pällhållare couples in turn; two couples on the floor at the same time.

- From the second minuet, each pällhållare boy in turn stood at the table end when they were dancing with the bride. With 10 pällhållare couples, up to eleven minuets and polskas would have been danced by this point. But this ceremony was not yet complete.

- The ceremony continued as all the pällhållare couples danced at the same time, without the bridal couple. First, all the pällhållare boys danced a minuet and polska with the corresponding girl, with pair No. 1 standing at the table end.

- Then, all the pällhållare couples danced simultaneously again, but they changed partners so that the first pällhållare girl (No. 1) danced with the final pällhållare boy (No. 10), allowing the first pällhållare boy (No. 1) to partner with girl No. 2; the boy No. 2 with the girl No. 3; the boy No. 3 with the girl No. 4, and so on. Following this pattern, the wedding party switched partners for each round until all the pällhållare boys had danced with all the pällhållare girls.

When the bride was not on the floor, the pällhållare girl No. 1 was all the time closest to the bridal couple’s table, and the pällhållare boys changed their place so that each could dance at the table end. All the pällhållare couples were able to dance ten consecutive minuets and polskas after each other. In this example from Ytterjeppo with ten pällhållare couples, a total of twenty-one minuets and twenty-one polskas were danced as ceremonial dances before the proceedings were finished and after this, the common dance could begin.

Sofi Norrback (b. 1847) from Forsby village reported an older custom when she explained that the first minuet and the polska were only played through by the musicians, without anyone dancing. This practice occurred in the early 1800s, including in southern Ostrobothnia when the polska opened the wedding dances. Then the bride and groom danced the first minuet and polska. After that, the bride and groom continued to dance with each pällhållare couple in turn, so that there were two couples on the floor at the same time. After that, a march was played to usher ‘the bridal couple out and pällhållare in’. All the pällhållare couples then danced the minuet and polska at the same time. Since there were at least four pällhållare couples at a wedding, at least six minuets would have been performed. The ritual of the bridal couple leaving the floor and the pällhållare entering it when a march was played was also mentioned above in Maxmo.26

Fig. 6.25 Minuet as a ceremonial dance at a wedding in Vörå, Ostrobothnia region, Finland, 1916. The minuet is danced by two couples at a time, with the bride and groom on the left. Photograph by Valter W. Forsblom. SLS 269_58. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.SLS+269_SLS+269_58, CC BY 4.0.

In Pedersöre, Esse and Purmo

From the parish of Pedersöre we glean somewhat different information. A 1930 account told that the bridal couple danced the first minuet but gives no further information about how the dance continued. Anna Lövholm (b. 1860) from Pedersöre parish told Yngvar Heikel in 1928 that the minuet and polska were danced only once as a ceremonial dance by the following persons: the bride with the ‘master of ceremonies’, the groom with the wife of the ‘master of ceremonies’, the mother of the bride with the father of the groom, the groom’s mother with the bride’s father, and each pällhållare boy his corresponding partner. After these minuets, other dances, such as the polka, waltz, schottische, and mazurka were danced, while each pällhållare would dance any of these dances in turn with the bride or the groom. The pällhållare paid for the dance and got a drink.27

In Ytteresse village, the first minuet and polska were danced by the bridal couple, and at the same time, all the pällhållare danced with their partners, Anna Lisa Ellström (b. 1858) reported. The bride danced the second minuet and the polska with the boy No. 1 at the table end. At the same time, the groom danced with the girl No. 1 and the rest of the pällhållare with their partners. The bridal couple then continued to dance with each pällhållare couple in turn, while the other pällhållare couples danced at the same time. This meant that every pällhållare boy had to dance at the table end and decide the minuet’s length while dancing with the bride. For example, if there were six pällhållare couples, seven minuets and polskas were danced before the ceremony was completed. In Överesse village, ninety-year-old Sofia Portin Teirfolk (b. 1834), who was said to have a good memory, explained that two couples danced a minuet and polska at a time as a ceremonial dance.28

In Purmo parish, it was said that the bride and groom danced the first minuet and the polska with the bride’s parents. Then the bridal couple danced with each pällhållare couple in turn, each time together with as many pällhållare couples, depending in this instance not on the number of participants, but on the size of the dance space. Also here, each pällhållare boy, in turn, danced at the table end.29

In Lappfjärd and Tjöck

In Lappfjärd and Tjöck, the ceremonial dances lasted for several hours, and it was called pällhållar dance. At a wedding at the end of the nineteenth century, the number of pällhållare couples could be four, six, or eight. The first pällhållar girl had a particular task, as she would pick up the bride’s white gloves when the wedding dinner started. Immediately after dinner, the pällhållare dance was performed, and after that, the female guests went home to change into other, presumably less constricting, clothes and returned for the common dance.

According to Otto Lill-Hannus (b. 1890) from Lappfjärd in the pällhållar dance, two minuets and a polska were danced in each round. I will return to this phenomenon of ‘two minuets’ later on. I assume here that the number of pällhållare couples is six:

- During the first round — of two minuets and a polska — all pällhållare danced with their partners. The bridal couple did not dance. The No. 1 pällhållare couple danced at the table end.

- During the second round, the pällhållare couples changed partners so that the boy No. 1 danced with the girl No. 2; boy 2 with the girl 3; boy 3 with the girl 4; boy 4 with the girl 5; boy 5 with the girl 6, and boy 6 with girl No. 1.

- Then the pällhållare continued to change partners for each round so that each pällhållare boy came to dance with each pällhållare girl. Since there are six pällhållare couples in this example, six rounds have been danced thus far — twelve minuets and six polskas. The first pällhållare girl (No. 1) always danced near the bride table with the other girls in their places, while the pällhållare boys subsequently changed their position and danced at the table end in turn.

- At this point, the bridal couple, who had not yet danced, entered the dance floor. The bride danced with pällhållare boy No. 1, the groom with pällhållare girl No. 1 and the rest of the pällhållare with their partners. When the bride was on the floor, she always danced closest to the wedding table, and the pällhållare boys danced at the table end as they danced with the bride.

- Then the bride and groom continued to dance with each pällhållare couple, and the other pällhållare danced simultaneously.

- As late as during the last round did the bride and groom dance together while the pällhållare danced with their partners.

With six pällhållare couples, this ceremony contained thirteen rounds—twenty-six minuets and thirteen polskas. Everyone, both boys and girls, got a drink for each dance, paying for the dance or alcohol by giving a gift to the bride.30

Fig. 6.26 Wedding in Lappfjärd, Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1909. The bride and groom with four pairs of their friends. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.%25C3%2596TA+146_ota146+foto+1101, CC BY 4.0.

The pällhållare always danced their local minuet, the minuet they had learned in their childhood or youth. Their musical accompaniment, however, varied. To the two minuets during each round, different tunes were played. A reputable wedding player did not repeat the same melody. Otto Lillhannus claimed that his musician grandfather Erik Ebb (b. 1814) had forty minuets, thirty polskas, and a number of waltzes in his repertoire.31

In Lappfjärd and Tjöck, as mentioned above, two minuets were danced in succession in the ceremony. One might wonder why this happened and how these minuets differed. The probable explanation is that, earlier in history, when there were only four pällhållare couples, the wedding ceremony was significantly shorter. In order to show wealth with a long ceremony, one could extend the proceedings by dancing two minuets, one after the other following by a polska. The first was danced in the usual way and the second with a swing (twirl), meaning that the dancers one turned (twirled), individually a lap around after changing places with the partner. The number of steps used for this twirl is not known, but the twirl was performed slowly. An informant from Tjöck told me in the 1990s that one had a lot of time to sit and watch the dancers and that and the women’s skirts barely moved while twirling. This twirl occurred only during the ceremony when two minuets were danced. By varying the dance style with a twirl, the ceremony’s extension, whose function was to demonstrate prosperity, was validated.

Later on, probably in the early 1900s, when six or eight pällhållare couples became the standard, the ceremony in Lappfjärd was shortened by determining that the pällhållare would change places with one’s partner only three times before the turning with hand in hand in the middle of the dance floor. The couples continued similarly after that, changing places three times again, but each continued to dance two minuets (the latter with a twirl). Information from Tjöck suggests that the minuet and polska were danced completely during the ceremony, which could mean that there was no set number of times the dancers would change places.

Fig. 6.27 Four farms in a row in Tjöck in Ostrobothnia in Finland, 1914. Photograph by Valter W. Forsblom. SLS 2351_38b. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS), https://finna.fi/Record/sls.SLS+235_SLS+235a_38b, CC BY 4.0.

In sum, the ceremonial dances in Lappfjärd and Tjöck was originally danced with four pällhållare couples. At that time, the ceremony was extended by dancing two minuets. Later, when there were more—six or eight—pällhållare couples, the ceremony was shortened by limiting the length of each minuet.

Yngvar Heikel also mentioned in connection with the minuet’s description in Lappfjärd that one usually rested a while before the polska began. It is not clear if this was also true within the ceremonial dances, or only when the minuet appeared as a common dance. My view, however, is that Heikel was referring to the ceremonial dances and that, in the common dance, there was no polska after the minuet.32

Fig. 6.28 Tjöck residents dance their minuet, with the bride and groom at the ‘end of the table’ during the arrangement of a traditional peasant wedding in Tjöck, Ostrobothnia, Finland, 1987. Photograph by Stina Hahnsson. © Finland’s Svenska Folkdansring.

The Minuet as a Ceremonial Dance in Nyland

In Nyland, the minuet never occupied the same vital role in the ceremony as in Ostrobothnia. There are only a few notes that the minuet was used there as a ceremonial dance. One document stated that the minuets were the first dance at a wedding, and it was called a ‘bridal minuet’: ‘It was danced first by the bride, groom, bridesmaids and groomsmen, after which the other guests continued’.33 Who danced with whom and how many couples danced at the same time is not specified.

In Eastern Nyland

On 3 November 1831, in Sarvlaks village in Pernå parish, Eastern Nyland, an eighteen-year-old nobleman named Carl Fredrik von Born took part in the wedding of his subordinates—a practice that was standard at that time. He recorded in his diary that ‘the newly-married danced together’ the first minuet while two musicians played the tune. The minuet was thus danced solo. Then, quadrilles were danced, ‘both Swedish and Russian,’ as well as waltz and anglais. Even in the neighbouring parish Liljendal, it was said that the minuet was performed as the first dance at the wedding.

In Pyttis parish, the minuet would always be the first dance at a wedding, according to an 1887 lecture by Gustaf Åberg (b. 1854). At that time, the polonaise had already taken over the role as a ceremonial dance, but the minuet continued to be used to open the dance proceedings. Åberg said that the bride would be invited by the priest, ‘or if he didn’t like dancing’, by the ‘master of ceremonies’. She was ‘then handed over to the groom, who in turn may lead the dance, etc’. The minuet was still danced in Pyttis parish into the 1890s.

Likewise, in Pellinge village, the minuet was a ceremonial dance during the latter part of the nineteenth century. The first minuet was danced by the bride and the ‘master of ceremonies’ and the second by the groom and the maid of honour. Then the father of the bride and the wife of the master of ceremonies danced, along with other relatives. The first minuets were danced solo, possibly two couples on the floor with the bridal couple as one of them. Then followed the waltz for everyone and when it was danced, ‘the so-called groom’s dance was played, which always consisted of a quadrille and after that polskas, waltzes, quadrilles, and minuets followed each other throughout the night’. It is rare that the ‘groom’s dance,’ a quadrille, was danced after everyone had been dancing.34

In Western Nyland