7. The Minuet in Norway

©2024 Gunnel Biskop, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.07

The minuet spread to all the Nordic countries, including Norway.1 Handwritten music notebooks from Norway are an early source of evidence. During the period of the later 1700s, the music in these notebooks is entirely dominated by minuets, according to Ånon Egeland.2 One of these notebooks is by Hans Nils Balterud, a farmer in Aurskog east of Oslo, and was written from 1758 to 1772. It contains about 380 tunes, of which about 280 are minuets.3 However, despite the abundance of records regarding minuet tunes, information about the dance itself is fairly minimal.

The Minuet in Norway in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

In many published diaries from the 1700s, the writers mention that they had danced but neglect to specify what they had danced. One of these diarists was the Swedish geologist Baron Daniel Tilas (1712–1772). In addition to being active in Sweden, he also made several trips to Norway and Finland to study mining and ecology. His diary offers a depiction of folklife because he described, among other things, weddings and costumes.

Fig. 7.1 Daniel Tilas described social life in Fredrikshald in 1749 in Norway, where the minuet was probably danced. Portrait by Olof Arenius (1750). Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Daniel_Tilas.jpg, public domain.

In 1749 he lived in Fredrikshald in southeastern Norway for many years. There Tilas participated in events in the social circles of two groups: the merchant class and the military officers and senior officials at the fortress of Fredriksten. His impression was that the two groups competed to arrange the most magnificent parties and banquets that extended into the morning hours. When he described the entertainments that the officers arranged, he felt compelled to mention as an example, ‘a concert and ball’ held weekly on Thursday evenings, ‘in purpose-rented rooms, and which was among the most distinguished and respectable subscription events in the city’. Tilas recorded that it was attended by about forty couples, that is, eighty people, with each person paying two riksdaler for admission. A typical evening would proceed like this:

The concert began at 5 p.m. and lasted until 7 p.m. Then lots were drawn to form couples for the first set of dances, partly to avoid rank order disputes and partly so that everyone would have danced at least once. Once the first set was finished, everyone was free to dance with whomever they wished. Coffee and tea were included in the price and, at about 10 p.m., cold meats, and bread and butter. Should anyone want to have wine, it was acquired and billed separately. The ball was scheduled to finish at midnight, and just as the clock struck, the music would cease abruptly. However, as the young people were not always satisfied, it usually cost a contribution for the musicians of a riksorts from each male attendee, and dancing often continued until 6 a.m.4

Dancing occurred in shifts, as Tersmeden described in Sweden. Attendance to one of these weekly events was restricted, and everyone paid for themselves. No one was considered to belong to ‘those with the highest [social] rank’ who otherwise would have been expected to dance the first round: all were equal. Thus, the determination of the dancing order occurred via the drawing of lots. There were two reasons why they drew lots to determine who would dance first: to avoid disputes over rank order precedence and to ensure that everyone danced at least once. In my view, they likely switched partners during the round, so that everyone danced with everyone else before the next round began. The author’s use of the word ‘disputes’ shows the significance and rigidity of social ranking. Tilas did not mention what was danced on these occasions, but I am convinced that it was the minuet. He also danced at balls arranged by the merchants and emphasized how similar the events were despite being organized by the two different groups. Therefore, I believe that the merchants in Fredrikshald also danced the minuet in 1749.5 Coupled with Nils Balterud’s music notebook from Aurskog which included a large number of minuets, Tilas’ diary fully supports the conclusion that the minuet was danced in Fredrikshald in 1749.

After the 1760s, more information is available about minuets in Norway. From the curricula of several dance teachers, we can gain an insight into what pupils learned at dancing schools in Christiania (modern-day Oslo), among other places. One of the dances taught was the minuet, as evidenced by advertisements in the first Norwegian newspaper, which began publishing in 1763. In 1770, C. D. Stuart from England, known as Madame Stuart, announced that she was teaching ‘Menuets’. Madame Stuart was a leading cultural personality who gave concerts and worked as a dancer, singer, and actor. In the same year, a peripatetic dance teacher, Martin Nürenbach, taught ‘Menuets, English Dances, and Solos’. In 1772, yet another dance teacher, Andreas Lie, came to Oslo to teach: ‘1) menuet according to the most recent method, 2) English dance with the correct original steps “released in this and the previous year”, 3) French Contradances, 4) Scottish Reels, 5) Solos with 12 variations’. That same year, dance teacher N. Brandt also came to Christiania, announcing that he would be teaching the ‘Menuet, English and French contradances, Minuet-Dauphin Solo, Pas de Deux’. Attempting to distinguish himself from local teachers, Brandt insisted that ’only those, who have learned abroad, could dance adequately’.6

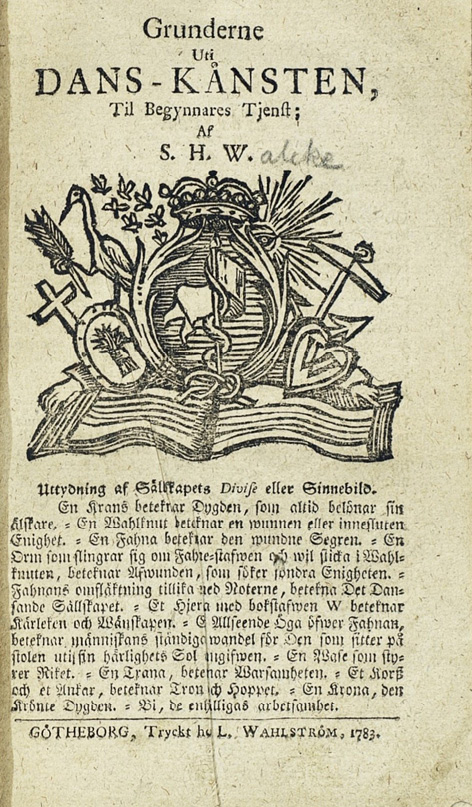

We can also gain insight into what pupils learned in Bergen, where Sven Hendric Walcke, a dance teacher, ran dance classes from the late 1790s into the 1800s. In 1783, in Sweden, Walcke published a book of dances, and in 1802 in Bergen, he published another book of dances containing English dances and contradances.

Fig. 7.2 Dance teacher Sven Hendric Walcke ran a dance school in Bergen, Norway. The image shows a page from a dance book he published in Sweden in 1783. Sven Henric Walcke, Grunderne uti Dans-Kånsten, til Begynnares Tjenst (Götheborg: L. Wahlström, 1783), https://litteraturbanken.se/f%C3%B6rfattare/WalckeSH/titlar/GrunderneUtiDansK%C3%A5nsten/sida/I/faksimil, public domain.

One of Walcke’s students was Johannes Carsten Hauch (1790–1872), later an author and zoologist in Denmark. Hauch related in his memoirs that a dance teacher came to Bergen and held dance classes for children. The lessons, which lasted for six to eight weeks, were attended by both girls and boys. Hauch and his younger sister were sent to these classes when he was not even ten years old.

Fig. 7.3 In his childhood, Johannes Carsten Hauch attended Walcke’s dance school but did not progress further than the minuet steps in his dance education. Portrait of Hauch by unknown artist. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HauchJC.jpg, public domain.

Hauch wrote extensively about Walcke as a dance teacher, and since Walcke is mentioned in many contexts, I quote the text here:

This dancing master called himself Mr. Walke and was employed on the Ballet staff in Copenhagen. He was a real character, and it seemed ironic that he should be a teacher in that art in which inborn grace is the pivot around which everything else revolves, a dignity which no learned behaviour can replace. He was tall, dry, and very skinny, almost like a skeleton, his head was narrow and bald, and his limbs were so severely proportioned that every movement was ungainly. He stammered severely, yes, and sometimes his voice ultimately failed him, which was blamed on a problem with his tongue. When this happened, he would flail the air with his hands. This often caused his pupils to laugh, which upset him much. As a consequence, his mouth would seize up even more, so he gesticulated, even more, provoking even greater laughter. Most of the time, it ended with a couple of the boys banished to a corner to be jeered at and as a warning to the others. As a result, you could sometimes see five or six boys standing in the corners, and when the punishment needed to be more severe, Mr. Walke himself would tie the arm of the delinquent to a large chair with a handkerchief. However, as I recall, the ladies were never subjected to this punishment, although it was often they who laughed most. He could leap, and perform entrechats, and turn around in the air while simultaneously playing his little pochette. All this was evidence of great agility and mobility, but it suited him poorly. However, he did know how to teach children so that they could participate in all the dances that were fashionable at that time in a short time.

As a dance instructor, Walcke did not seem to have physical qualifications on his side, but he nevertheless worked as a dance instructor in many different venues. His dance course was divided into classes. Hauch wrote:

The course was divided into three boys’ classes and three girls’ classes, into which everybody, as far as possible, was assigned depending on the progress made each day. My sister and I first started the course sometime after it had begun. My sister, who at that time had very light and graceful movements, made rapid progress; I, on the other hand, was plodding, and it cost me a lot of effort just to learn the five positions and so-called big [grand] and small [petit] battements that preceded the actual dance figures. The various steps, or where to place the feet to dance the minuet or a waltz or a so-called English dance, were drawn in chalk on the floor. For a long time, I did not get beyond the minuet step and was therefore placed in the third class, among the youngest children.7

Young Hauch had difficulty mastering the five positions and the big and small battements [leg movements], which the students had to learn before progressing to participating in the dances themselves. The dance teacher also indicated in chalk on the floor where the feet were to be placed. Unfortunately, the author did not progress beyond the minuet steps and was placed in the third class among the youngest children.

In the same period, in Stavanger, the minuet was danced in ‘Det Stavangerske Klubselskab’ [The Stavanger Club]. The company was chartered in 1784. Ten years later, its charter was revised, and several regulations were added in subsequent years. Ambiguities in their detail prompted questions from members. One of these questions was whether children should accompany members to balls. A response from 1795 stated that:

Whether the correspondent’s minor and not yet confirmed children may attend regular Balls—NB. Only one at a time from each household–no one who cries, but only those who can dance the minuet or English [dance] properly without incommoding the company—and NB. not at festive occasions, as the attendance at these is large enough.

This answer stipulates that the children should know how to dance ‘the minuet or English dance properly’ to attend general balls. In January 1796, the club’s constitution was amended to specify that a not-yet confirmed minor may participate in public balls if he or she ‘can dance without disrupting the dance’.

But by the beginning of the 1800s, it seems that the club’s balls were not conducted entirely according to the rules. It was decided in 1802 that:

at balls, English dances may not be danced by more than 12 couples at a time; that between every two English dances, three minuets be played, as long as someone steps forward to dance them; if no one steps forward to dance the first [of the three] minuets, then another English dance begins right away. To supervise this, the youngest Director will be present throughout the ball.

By ruling that only twelve couples may dance an English dance, the organizers probably wished to limit the length of those dances. There is an uncertainty in this statement as to whether anyone would come forward to dance the minuet, suggesting that not everyone was interested in it any longer. The minuet continued to appear in the 1823 edition of the regulations. The repertoire and the order of the dances is precisely specified:

the first two dances before and after the meal with four sequences, later at least two with four sequences between each with six [sequences]. After every two English dances may be played a minuet or a waltz, which must not last longer than 5 minutes, no other dance must last longer than 1 hour. There are precise rules and penalties in case of breaches of the regulations concerning sequences, quadrilles, and figures.8

Here, in 1823, it was decided that a minuet could be danced as an alternative to a waltz. Since it was necessary to regulate how long a minuet or waltz might last, it raises the question of whether the minuet was danced by one couple at a time, thus prolonging the time it took. Similarly, one can only speculate whether the waltz was danced by a few couples at a time, for a few turns around the floor, and then continued by other couples, which would prolong the length of the dance if there were many couples.

Lieutenant-Colonel Jens Christian Schrøder described a dance in a private home in his memoirs. He gives an account of, among other things, the social life in his parents’ home at the Valde estate in Vestfold, southern Norway, in the early 1800s. Several members of the military lived in the village, and they customarily gathered at Christmas for dinner and dancing at each other’s residences. On Christmas Day, they always convened at the home of Schrøder’s parents. Schrøder wrote that red wine was drunk with the food and that guests sang at the table and collected money for the poor. He also described what was always danced:

In the evening, punch and beer were served. There was never a party at Valde at which, in the evening, my father did not lead a menuet, in remembrance of the old days and to honour the older guests, who all joined him on the dance floor, including an old aunt—sister to my maternal grandfather General Grüner. One would see the senior dragoon officers with big boots and big silver spurs advancing and retiring in their minuet. Only my father, I seem to remember, danced this noble dance with grace. After the Menuet, most of the younger and more agile dancers followed with the so-called ‘springedans or Polskdans’ with its leaps and capers.9

All the older people danced the minuet. The host, the father of the household, ‘led’ the dance; in other words, he danced ‘as the first couple at the top of the set’. That honour was self-evident since the dance was held on his estate. It was also a given that the older generation had the first dance to themselves since one danced in order of social rank. After the more senior guests had danced, the younger guests were allowed to dance, and they mostly danced ‘springedans or Polish dance’. At parties at Valde, the military officers wore their dress uniforms with boots and silver spurs and clearly caught the attention of a wide-eyed child.

According to a memoir by Johan Christiansen (b. 1832 in Askim in southeastern Norway), the minuet was losing its popularity in the mid-nineteenth century. He described the balls and how the ladies and gentlemen were dressed. About the dances, Christiansen wrote that they usually consisted of ‘the Lancers, Francaise, Figaro, Waltz and Mazurka, and the older generation even danced the minuet, which they called “Mellevit”’.10 Only the generation still danced the minuet at this time. Christiansen’s account does not specify in which social environment this occurred.

The Minuet among the Rural Population during the Nineteenth Century

The minuet has also been danced in Norway at different times in different rural areas. In her memoirs, Gustava Kielland (1800–89), who was married to the parish dean Gabriel Kielland, described the minuet on Finnøy in Boknafjorden north of Stavanger. The dean’s family lived on the island from 1823 to 1837.

Fig. 7.4 Gustava Kielland told about minuet dancing on Finnøy in Boknafjorden in Norway. Localhistoriewiki.no, https://lokalhistoriewiki.no/wiki/Fil:Gustava_Kielland_01.jpg, public domain.

She dictated her memoirs later in life, and they were published in 1882. In her depictions of weddings on Finnøy, she mentions that ‘mellevit’ was danced. Kielland wrote that it was often tricky to persuade wedding guests to be seated at the tables. People held back and were reluctant to be the first to be placed since the seating was arranged according to social status. Gustava and her husband Gabriel had the highest rank among the guests, and as a matter of course, would be seated closest to the bride and groom. Kielland explained:

When you arrived at the farm where the wedding was being held, you were received at the door by the master of ceremonies with a ‘stirrup cup’, ie. a glass of schnapps and a pretzel. After entering the room and greeting the bride and groom, their relatives, and the other guests, one was seated at the table. When it came to Gabriel and me, it was an easy task for the master of ceremonies, we were obviously to be seated closest to the bridal party. But the master of ceremonies had a great deal of difficulty seating the other guests, as social rank had to be strictly adhered to. He had to ensure that each guest was seated correctly according to his or her rank. This was not always so easy for the master of ceremonies.

Kielland further elaborated on the seating arrangements, writing that the guests were possessed by a ‘reticence demon,’ which meant that most modestly preferred not to sit at the place to which the ‘master of ceremonies’ directed them but rather to be seated further away from the place of honour where the bride and groom sat. It became a verbal battle and a tussle that struck the recently-arrived minister’s wife as comical. She was not aware of the custom, which was common in rural communities all over the Nordic countries.

During the day, dancing could take place outdoors, and in the evening, indoors. Kielland said:

In the evening, the hall was filled with guests, leaving only a small open space. There the bride would dance ‘mellevit’ with the groom and a couple of other close relatives; they did not have much room to move. The bride’s dancing was stiff, stately, and careful because of the bridal crown, and her partner could not make giant leaps in the small space. I can still see our aged neighbour, Lars Fleskje, at his sister’s wedding, gracefully and carefully dancing ‘mellevit’ with her in a similarly small space, with a little dribble of tobacco juice staining each corner of his mouth. All the guests had to see the bride dance ‘mellevit’.11

This depiction indicates that the minuet was still customarily danced on the island in the 1830s.

Fig. 7.5 Finnøy Rectory in Norway. Painted by Thomas Fearnley (1826). Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Finn%C3%B8y_av_Fearnley.jpg, public domain.

Kielland described two different weddings at which she had seen the minuet danced. At the first, she mentioned that the bride would dance minuet with the groom and then with ‘a few others’, maybe with two or three of the bridal couple’s closest male relatives. My view is that the minuet here was danced one couple at a time. She further elaborated that the bride’s dancing was stiff and stately because of the crown; this was undoubtedly true, but, in my opinion, Kielland was unfamiliar with the slow and graceful style of the minuet when it was used as the first dance at a wedding. The bride’s dance partner, in that situation, would not make giant leaps. Kielland here recalled a second wedding at which an older neighbour, Lars Fleskje, danced the minuet gracefully and cautiously with his sister, the bride. Fleskje’s minuet was danced in the correct style for the ceremonial part of the wedding dance. Fleskje is unlikely to have been mentioned were it not for the tobacco juice dribbling out of the corners of his mouth. It was common for everyone to see the bride dancing minuet.

From folklife depictions, it appears that the minuet continued to be part of Norwegian wedding customs well into the latter part of the 1800s. In Vest-Agder in southern Norway, it was still danced in 1886 at a wedding by some older women who requested it when they were contributing to the payment for the musician(s) since they felt they were too stiff and unsteady to attempt the more popular dances. By that time, the minuet, as well as the tretur and fyrtur, were considered ‘resting dance[s]’ and not suitable for a man to dance. Such a resting dance had to be followed by a faster dance, for example, a ‘springdans’. This was still considered the norm around 1900.

Many accounts from Vest-Agder record memories of minuet dancing. A woman in Fjotland, who had seen a girl of confirmation age dance the ‘melevitt’ said, ‘there were two of them; she turned her head so much’. Another remembered that a woman ‘held out her skirts and turned on the floor with another dancer, either man or woman’. In a local folklife depiction, Jon Gunnuvson (b. 1835) described the elderly dancing the minuet:

I saw the melevitt once. It was at Ola Kjerran’s wedding in Åmdal. There were three of them [dancing]. I think it was Torborg Åmdal, Ola from Hedningskjerret, and Eli Knibe. They took small steps towards one another and swayed out to the sides again. It was the most beautiful dance I have ever seen. It was just like a child’s play. But young people never try mellevit. The steps are so tricky.12

The depiction here is of three people dancing the minuet. Similar information was also given by a woman in Hægbostad, who had heard that ‘when they danced the melevitt, they were three dancers’.

From Kragerø, northeast of Vest-Agder, another report seems to indicate that three persons danced the minuet. Fredrik Hougen (b. 1820) included in his memoirs a funny story about the minister and headmaster Hans Georg Daniel Barth (b. 1814), who was known to be ironic, playful, and extremely agile. He could fold himself double and pretend to be ‘a dwarf’. He had done so during the Christmas holidays when families were visiting each other. Barth’s wife Charlotte had arrived at one such get-together around 1850 hand-in-hand with this ‘dwarf’: Barth himself. Both had mingled among the other guests, greeted everyone, and ‘participated’ in the minuet. Whether this stunt was or extemporaneous is not clear; however, the report indicates that people knew the minuet and knew it well enough for the absurdity to be entertaining. Hougen wrote:

After New Year, there was a big festive ball hosted by the town’s richest wholesaler. The host had enlisted the catechist [minister] to dance the minuet with him. The host’s other partner was the wife of Weibye, the head customs official. In her younger days, she had been a lady-in-waiting at the court in Stockholm and still carried herself with courtly demeanour. This piqued the ironically-inclined catechist. As the host with his courtly partner performed the solemn turns, the catechist made his most significant efforts to mimic them, dancing like a dwarf between the stately couple or rolling like a ball of wool around them to the great amusement of the whole company. They laughed till they cried.13

The minuet in question was a version for three dancers: the host with Mrs. Weibye and with the agile comedian Barth. The contrast was exaggerated because Mrs. Weibye had been lady-in-waiting in Stockholm and carried herself accordingly. It is probable that the host, the wealthy wholesaler, had not intended the minuet to be a comic spectacle but rather a majestic display. Taking the former lady-in-waiting and the minister as his partners, the host would not have expected antics from those of such comparatively high social rank.

In Gudbrandsdalen, the music of the minuet survived among musicians into the 1900s. The fiddler Trygve Fuglestad (b. 1902) could play a minuet, explaining that ‘I learned it from my mother. She told me that the boy and the girl each danced by themselves, the boy holding out his trouser legs with his hands and the girl holding out her skirt’.14 Klara Semb, who documented folk dances in Norway at the beginning of the twentieth century, heard about some people who could dance the minuet but did not want to demonstrate it for fear of ‘giving it away’. Semb was not able to get a description.15

We do not know how the minuet was danced in Norway. It appears that there were two different versions: the ordinary minuet and a version for three dancers. I have not found a minuet for three people elsewhere in the Nordic countries. Therefore, it is interesting that the late-twentieth-century dance researcher Karl Heinz Taubert mentions a popular minuet for three to twelve individual dancers. Other popular versions were for two couples (en quatre), for four couples (en huit), for three couples (en six), and eight couples (en ronde).16

The minuet which was danced one couple at a time at the weddings in Finnøy could be similar to the ordinary minuet from the 1700s. This is also likely to be the case for the minuet seen by the German dancing master Friedrich Albert Zorn (1816–95) in Norway in 1836. Zorn worked as a dancing master in Christiania at the time.17

Fig. 7.6 In his youth, Friedrich Albert Zorn visited Hønefoss in Norway in 1836 and watched the minuet performed. Portrait of Zorn. Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek, https://ausstellungen.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/tanz/items/show/98, public domain.

Zorn later became a well-known choreographer and dance theorist. In his book, Grammatik der Tanzkunst (1887), he included details of the dances and dance steps. Zorn described the ‘Menuet de la cour’ [the minuet of the royal court], which I call the ‘standard’ minuet, noting how it has spread to many countries and to all royal courts in Europe, as well as to remote areas where one would not at all expect to see it. An example of one such place he gives is Norway. I have translated his words here:

The author was once very astonished to see the peasant boys and girls dancing it [the minuet] in an isolated Norwegian village (Høhnefossen), having travelled there to learn about the national dance of the area, the halling. 18

The ordinary minuet, the court minuet, had thus spread to Hønefoss by 1836. Zorn had travelled there to acquaint himself with the Norwegian ‘national dance,’ the halling. There he saw boys and girls of the peasant class dancing the minuet. Hønefoss, which lies about sixty kilometers northwest of Oslo, was a tiny remote village. For this reason, Zorn was surprised to see the minuet being danced there. Unfortunately, he did not describe how these peasant boys and girls danced the minuet, but Zorn was only twenty years old at the time and had not yet begun his choreographic or theoretical work. He recorded his reminiscence of the minuet in Hønefoss in the 1880s. If the dance had been somehow different from the ordinary minuet, I suspect that Zorn would have mentioned it. Therefore, I think that the minuet in 1836 Hønefoss was very similar to the ordinary minuet.

Concluding Remarks

In Norway, the minuet was danced by various social classes, as in the other Nordic countries. The minuet was danced there from at least the mid-1700s and was still being mentioned in the 1900s. Much evidence is to be found in music notebooks from the later part of the 1700s. Although the details given are sparse, it can be seen that the minuet was danced on larger estates and landholdings, it was danced solo [by one couple] as the first dance at weddings on a small island, and it was danced by young peasant boys and girls. Finally, in addition to the ordinary minuet, a version of the minuet existed which allowed for three dancers.

References

Bakka, Egil, Brit Seland Dag Vårdal, and Ånon Egeland, Dansetradisjonar frå Vest-Agder (Vest-Agder Ungdomslag/Rådet for folkemusikk og folkedans, 1990)

Biskop, Gunnel, Menuetten — älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden — särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder — under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015)

Christiansen, Johan (pseudonym), Mine Livserindringer af Christer (Christiania: H.S. Bernhoft, 1908)

Christensen, Carl, Træk af Det Stavangerske Klubselskabs Historie (Stavanger: Det Stavangerske Klubselskab, 1915)

Hauch, C., Minder fra min barndom og min ungdom (Kjøbenhavn: C.A. Reitzels Forlag, 1867)

Hirn, Sven, Våra danspedagoger och dansnöjen. Om undervisning och evenemang före 1914. SLS 505 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1982)

Hougen, Fredrik, Kragerøminner, 5 vols. (Kragerø: Vestmars forlag, 1936–41)

Kielland, Gustava, Erindringer fra mitt liv (Stavanger: Nomi forlag, 1967)

Koudal, Jens Henrik, For borgere og bønder. Stadsmusikantvæsenet i Danmark ca. 1660–1800. Københavns Universitet (København: Museum Tusculanums Forlag, 2000)

Qvamme, Børre, Det musikalske Lyceum og Konsertlivet i Christiania 1810–1838 (Oslo: Solum Forlag, 2002)

Schrøder, Hans, Oberstlieutenant Jens Christian Schrøders Erindinger, Fra Svunden Tid. Norske breve, erindringer og dagbøker, bind 3 (Kristiania: Steenske forlag, 1924)

Taubert, Karl Heinz, Das Menuett. Geschichte und Choreografhie (Zürich: Pan, 1988)

Tilas, Daniel, Daniel Tilas, Curriculum vitae I–II 1712–1757 Samt Fragment av dagbok September–Oktober 1767, ed. by Holger Wichman. Historiska Handlingar, del 38:1 (Stockholm: Kungl. Samfundet för utgifvande af handskrifter rörande Skandinaviens historia, 1966)

Wyller, Trygve, Det Stavangerske Klubselskab og Stavanger by i 150 år (Stavanger: Dreyers Grafiske Anstalt, 1934)

Zorn, Friedrich Albert, Grammatik der Tanzkunst. Theoretischer und praktischer Unterricht in der Tanzkunst und Tanzschreibkunst oder Choregraphie (Leipzig: J. J. Weber, 1887)

1 Gunnel Biskop, Menuetten—Älsklingsdansen. Om Menuetten i Norden—Särskilt i Finlands Svenskbygder—Under Trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015). [The Minuet—The Loved Dance describes the minuet in the Nordic region—especially in the Swedish-speaking population in Finland—for three hundred and fifty years]. The text is a translation into English of a chapter in the book.

2 Egil Bakka, Brit Seland, Dag Vårdal, and Ånon Egeland, Dansetradisjonar frå Vest-Agder (Vest-Agder Ungdomslag/Rådet for folkemusikk og folkedans, 1990), p. 55.

3 Jens Henrik Koudal, For borgere og bønder. Stadsmusikantvæsenet i Danmark ca. 1660–1800. Københavns Universitet (København: Museum Tusculanums Forlag, 2000), p. 548.

4 A ‘riksorts’ was one quarter of a rixdollar. Daniel Tilas, Daniel Tilas, Curriculum vitae I–II 1712–1757 Samt Fragment av Dagbok September–Oktober 1767, ed. by Holger Wichman. Historiska Handlingar, del 38:1 (Stockholm: Kungl. Samfundet för utgifvande af handskrifter rörande Skandinaviens historia, 1966), p. 226–28. Tilas was born at the Gammelbo mine in Ramsberg in Västmanland, Sweden. His grandparents were Urban Hjärne and Maria Swaan. The poem containing the first reference to the minuet in Sweden was dedicated to them on the occasion of their wedding in 1676.

5 The fact that Tilas did not name the dance may be because it was a given that it was a minuet and did not, therefore, need to be specified. By contrast, while visiting a market in Mora in Dalecarlia, Tilas had encountered a dance with which he was unfamiliar, and in, that instance, he named the dance. He wrote that he did not know the dance but learned it. It was called ‘Mora huppdantzen’. He was a quick learner and could quickly ‘step into the main dance’ in front of ‘an audience of several hundred’. To finish the event, the dancers participated in a chain dance. See Tilas, pp. 44–45.

6 Børre Qvamme, Det Musikalske Lyceum og Konsertlivet i Christiania 1810–1838 (Oslo: Solum Forlag, 2002), p. 19. According to Sven Hirn, Nürenbach had previously visited Åbo, Helsingfors and Gothenburg, and returned from Christiania to Finland in 1773. One can assume that he taught the same dances in all those places. See Sven Hirn, Våra danspedagoger och dansnöjen. Om undervisning och evenemang före 1914. SLS 505 (Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1982), p. 14.

7 C. Hauch, Minder Fra Min Barndom Og Min Ungdom (Kjøbenhavn: C.A. Reitzels Forlag, 1867), pp. 67–70. Citation 4.5.2004 from Nordisk databas, according to Kari Okstad.

8 Carl Christensen, Træk af Det Stavangerske Klubselskabs Historie (Stavanger: Det Stavangerske Klubselskab, 1915), pp. 8–19, pp. 24–25, p. 26; c.f. Trygve Wyller, Det Stavangerske Klubselskab og Stavanger by i 150 år (Stavanger: Dreyers Grafiske Anstalt, 1934), p. 155. Citation 20.5.2004 from Nordisk database, according to Egil Bakka. Thanks to Oddbjørn Salte who mentioned the source.

9 Hans Schrøder, Oberstlieutenant Jens Christian Schrøders Erindinger, Fra Svunden Tid. Norske breve, erindringer og dagbøker, bind 3 (Kristiania: Steenske forlag, 1924), pp. 16–17. Citation 10.5.2004 from Nordisk databas, according to Egil Bakka.

10 Johan Christiansen, Mine Livserindringer af Christer (pseudonym) (Christiania, 1908), p. 184. Cit. 5.4.2004 from Nordisk databas, according to Kari Okstad.

11 Gustava Kielland, Erindringer Fra Mitt Liv (Stavanger: Nomi forlag, 1967), pp. 123–26.

12 Jon Gunnuvson, qtd. in Bakka, et al., pp. 52–53.

13 Fredrik Hougen, Kragerøminner, 5 vols (Kragerø: Vestmars forlag, 1936–1941), iv, p. 551.

14 Fuglestad, qtd. in Bakka et al., p. 55.

15 Semb, qtd. in Bakka et al., p. 55.

16 Karl Heinz Taubert, Das Menuett. Geschickte und Choreografhie (Zürich: Pan, 1988), p. 30.

17 Friedrich Albert Zorn, Grammatik der Tanzkunst. Theoretischer und Praktischer Unterricht in der Tanzkunst und Tanzschreibkunst oder Choregraphie (Leipzig: J.J. Weber, 1887), p. 20.

18 Ibid., p. 183.