SOURCES ABOUT THE DANCE FORM AND HOW THEY WERE CREATED

The chapters in Part III systematically survey the sources that were produced to document the minuet as movement patterns. These sources mainly include descriptions, notations, and recordings. From the early eighteenth century until the end of the nineteenth century, dancing masters were the sole creators of these resources. However, in the early twentieth century, a new group of experts emerged: folk-dance collectors established themselves and added filming as a new documentation technique, particularly from 1970 onwards.

The sources produced by Nordic dancing masters are relatively modest and depend to a large extent on European sources, so these are surveyed as a part of the total picture of the minuet. One expression of the dance that is not given primary focus in this book is its variety of theatrical formats—but some of these sources are briefly surveyed.

As for the documentation from folk-dance collectors, the situation is reversed. The minuet disappeared in Europe; we have not been able to find any evidence that the ‘folk minuet’ had a continuous existence outside of the Nordic countries. However, because the folk minuet was documented in some rural communities in Denmark and Finland, it was folk-dance collectors who produced this documentation. On the other hand, due to the earlier disappearance of the folk minuet in Sweden and Norway, these folk-dance collectors did not manage to document corresponding material in their countries.

Thus these chapters discuss the creation (and creators) of the sources, as well as the context of their production and use. The collection and documentation of the folk minuet has particularly rich material that places the dance in its social context. The chapters give examples of notations and descriptions, and, where available, even the field notes of the collectors as an illustration of the variety of sources. Also included is a brief survey of works showing how the minuet music spread to the Nordic countries as well as a draft about how these were created.

9. Historical Examples of the Forms of the Minuet

©2024 Elizabeth Svarstad and Petri Hoppu, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.09

Historical sources in the Nordic countries reflect the minuet’s strong position in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Egil Bakka stated that the minuet was probably the dominant dance among the upper classes in the Nordic countries for most of the eighteenth century and went out of fashion sometime before 1800.1 Around the mid-1700s, the minuet also gained a valued position in the culture of the lower classes of society in many places in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland. And it never fell completely out of fashion among this group. As a folk dance, the minuet is still an on-going practice even today in some areas.

In this chapter, we first look at the forms of the minuet through European sources. We present how the French court minuet and its practice as well as different minuet forms are presented in selected Nordic sources from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Examples of sources that contain a remarkable amount of information on the minuet are a Norwegian manuscript from around 1750 with notes from a dance lesson, dance books by Swedish dancing master Sven Henrik Walcke, the dance book of Swiss dancing master J. J. Martinet from 1797 (translated into Danish in 1801), early nineteenth-century dance books from the Danish dancing masters Pierre Jean Laurent and Jørgen Gad Lund, as well as the 1886 manual of the Norwegian dance teacher Janny Isachsen.2

The French Court Minuet

The French court minuet, or the ordinary minuet, is a dance in 3/4 time and exists in several variations. As a ballroom dance at the French court in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, it was danced by one couple at a time. For many years, the standard minuet was the first dance to be performed at formal balls in France. It was danced by all couples that were present and in hierarchical order according to social rank. The French dancing master Pierre Rameau (1674–1748) described in 1725 how the minuet was organized at a so-called bal reglé. The king and queen would dance the first dance. Next, the queen would dance with the prince, or whoever was the next in the rank order before the prince would dance the next minuet with the princess. And so it continued down the hierarchy; each one danced, in turn, two minuets.3 Since the courts were large, the session dedicated to the minuet must have lasted a long time. Only upon the completion of the minuets could the ball proceed with the other dances on the program.

In addition, as an obligatory part of the minuet, every couple had to perform proper bows and curtsies, so-called reverence, both before and after the dance. The reverence was first directed towards the king, and after that, the couple would bow and curtsy to one another. American musicologist Tilden Russell wrote that the minuet with its incorporated bows had the function as a formal opening ceremony at the court balls as well as a ‘show’ and a demonstration of status.4 The hierarchy that determined the order of dancing couples, the room’s visibility, and the carefully and elegantly performed dance made the minuet very suitable within the ball’s formal frames and an arena for displaying gentility as well as dance skills.

In addition to the ordinary minuet, there were also minuets as a part of the theatrical dance repertoire, and several choreographies exist in Feuillet notation for either a couple—comprised of a man and a woman or of two men—or a solo man or woman. These minuets ranged from easier versions to more elaborate and technically advanced dances. Elements of minuets also appeared as part of compound dances, or suites, and contradances or parts of contradances.5

The minuet’s fixed form and its use of basic steps contributed to making it very suitable as a starting point in both dance and education. Even though it was technically advanced, it was more straightforward in its construction than many other dances in the eighteenth-century European repertoire. For example, dances such as the sarabande, bourrée, and gigue were choreographed from the beginning to the end with different steps and step combinations for each music bar, while also changing choreography for each specific piece of music. By contrast, the minuet could, or can, be danced to almost any minuet tune. Because it consisted of a limited system of figures,6 the minuet could be danced with greater flexibility than these other aforementioned choreographed dances, in which every detail needed to be mastered to perfection. The minuet, despite its fixed form, allowed improvisation. Its figures could be repeated several times, according to the dancers’ choice, and, as mentioned earlier, one could vary the dance steps with different versions of the minuet step and replace some of the minuet steps with other steps, such as the pas de bourrée or pas balancé, for example. But too many elaborations made the minuets very long, and the abovementioned ceremony of minuets opening a ball might last for hours. Rameau wrote in 1725 that he believed the minuets should be kept as short as possible: ‘It is both reasonable and becoming to set some Limits; for though a Person never dances so well, the figure is still the same. Therefore the shorter it is made, the better’.7

Different Forms of the Minuet

From the early eighteenth century, bal réglé became a common form of dance event among courts and high society in Europe. A key characteristic of these formal balls is that they were opened with a series of minuets. The standardised form of menuet ordinaire was common at courts all over Europe, with insignificant variations as the European eighteenth-century dance manuals witness.

However, the dancing of one couple at a time was not the only option in the ordinary minuet, although it was the most emblematic and best known. Several couples could share the dance floor as well. A German dancing master, C. J. von Feldtenstein, described in 1772 the latter kind of dancing in the following manner:

When a whole row of dancers set themselves to dance so that all the couples will perform simultaneously and dance every figure of the minuet with the same tempo or rhythm at the same time, then a certain symmetry in one’s eye is developed. […] When a row wants to end their dance and a new row of dancers intends to enter the dance floor, the first ones finishing their dance with reverence but the others starting the minuet with an opening compliment immediately, then the dance hall is never empty[.]8

Thus, we can see that the minuet could be danced in a similar ‘longways’ set as one did in many contemporaneous contradances. Feldtenstein explained that, while dancing like this, the usual Z-figure needed to be danced in a more curved way to allow several persons to make it at the same time. Interestingly, this was the most typical arrangement for minuets among Danish and Finnish peasants.

According to Karl Heinz Taubert, the minuet could also be danced by several couples simultaneously, without following any specific formation, so that couples arranged themselves freely on the dance floor, facing their partners.9 Taubert’s interpretation, however, is based on an early-eighteenth-century picture, and its reliability is doubtful. We have not found other evidence confirming this kind of dancing although it may have been practised.

In addition to the ordinary minuet, new minuet choreographies were created. From the beginning of the eighteenth century until the French Revolution, approximately forty minuet choreographies were published: most of them were complex variations of the ordinary minuet, figured minuets (menuets figurés), and a few that originated in the theatre. While any minuet melody could accompany the ordinary minuet, figured minuets were connected to specific tunes.10 In 1717, in his treatise, Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister, Gottfried Taubert mentioned some examples that became popular during the eighteenth century: Menuet de [la] Cour, Menuet d’Anjou, and Menuet d’Espagne.11 As a matter of fact, Menuet de la Cour survived in many forms until the twentieth century, gradually coming to represent the ideal of what the minuet had been and should be.12

Contradances that became popular in Europe during the eighteenth century also influenced the development of the minuet. The contradances that were minuets, for example, Le Menuet à quatre [the Minuet of four (dancers)] and Menuet en huit [the Minuet for eight (dancers)] were both accompanied by minuet music and performed in longways or square formations containing minuet steps. 13

The most famous publication of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English country dances, the roots for the European contradance paradigm, was John Playford’s The English Dancing Master, which came out in several revised editions from 1651 to 1728. The total number of dances in the eighteen volumes is 1053.14 The earliest editions do not contain minuets, but, in the later ones, one finds ten dances that are called minuets (see Table 9.1).

Table 9.1: Minuets in The Dancing Master15

|

Name |

First Published |

|

1695 |

|

|

1696 |

|

|

1701 |

|

|

1710 |

|

|

1710 |

|

|

1718 |

|

|

1726 |

|

|

1726 |

|

|

1726 |

|

|

1726 |

These dances are typically danced with minuet steps and music with minuet rhythm, but otherwise, they are longways dances, common English country dances. In addition to these dances that have the word minuet in their names, some editions of The Dancing Master contain other dances with minuet steps and rhythm without any reference to minuet in their titles (Table 9.2).

Table 9.2: Other dances with minuet steps and rhythm in The Dancing Master16

|

Name |

First published |

|

The Marlborough |

1706 |

|

Drive the Monsieur from Flanders |

1710 |

|

Mademoiselle Dupingle [also known as Sabina] |

1718 |

|

Beautiful Clarinda |

1726 |

|

Belsize |

1726 |

|

Love in a Mask |

1726 |

Using minuet steps in contradance figures was not the only way these two different dance forms were combined. The Menuet/Minuet Congo or Minuet d’Hugger reuses the Z-figures and hand movements of the minuet while including various steps and rhythm of contradances in the same dance. That is, the minuet steps are absent. Although the descriptions of the Menuet Congo variations do not include music, the accompanying music was probably similar to that used in contradances rather than in the minuet. This type of combined-dance appeared in several countries in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.17

Notes from a Minuet Lesson

We now turn to Nordic manuscripts and publications from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and examine what they say about the minuet. The manuscript Information i Dandsingen av Monsieur Dulondel [Information (Lesson) in Dance by Monsieur Dulondel, no date] contains notes on dance, and on the minuet especially. It even includes some Feuillet notation, which is a unique find in the Norwegian source material.18

Christopher Hammer (1720–1804), in whose collection the Information i Dandsingen manuscript was found, was a student at the Sorø Academy in Denmark from 1747 to 1748. According to historian and librarian Vegard Elvestrand, students there were taught so-called ‘noble exercises’ and other arts and activities. These noble exercises consisted of fencing, music, dance, horse riding, and arts, according to the Sorø Academy’s laws, as discussed by Vegard Elvestrand.19 The manuscript may very well have been produced by someone connected with the dance teaching at Sorø. Elvestrand has the impression that the manuscript was written from dictation, but he does not think this was work done by Hammer himself, finding it unlikely that the young man went to a dance school for a general education that led him to become a civil servant.20 Although information has not been found that connects the French master Monsieur Dulondel and Hammer to dance teaching at Sorø, it is somewhat likely that Hammer participated in dance lessons as dance occupied an active position in young people’s education and social life. Further, while there is no information showing that Hammer danced while he was living in Norway, he pointedly mentioned dance and, specifically, the minuet in his Sognebeskrivelse over Hadeland—an undated text describing life in the parish for which he acted as overseer.21 The fact that he kept this and one other dance manuscript in his library does show that he had a particular interest in dance.

The Information i Dandsingen manuscript contains information on dance and dance instructions as well as how to perform bows and curtsies. Much of it concerns the ordinary minuet for one couple, which seems to have been the central theme of the dance lesson from which the notes are taken.22

The first part of the manuscript contains information about the relationship between the dance and the music. The next part contains data on dance technique in general, such as the five positions of the feet. These are described using Feuillet notation, showing first the positions of the left foot then those of the right. The subsequent parts explain how to perform a reverence—the bow and curtsy that were an obligatory part of the minuet. Reverences were performed before the dance and after the dance, and European dance manuals describe the correct ways to make proper reverences for different situations. The description in Hammer’s manuscript corresponds with instructions given by Taubert and Rameau and includes notes on how to take off and put on the hat.

The notes within this manuscript that concern the minuet focus on the Z-figure. There are also notes on how to hold the body, which also correspond with descriptions in Taubert and Rameau. Emphasis is placed on keeping the body straight, the arms turned a little outwards, the fingers a little rounded, and the feet turned outwards. One of the paragraphs in the manuscript concerns especially the turning out of the feet. It insists that ‘If the [pupil’s] feet cannot be well turned out, they must be forced by using a board’. There is also a drawing showing the foot signs in Feuillet notation and how the angle of the turned-out feet becomes wider when standing on the board, which is called a tourne-pied or a tourne-hanche. This method shows that well-turned feet were ideal for dancing correctly, forming the pupils’ bodies, and developing an elegant way of standing and walking.

Towards the end of the manuscript, there is a note describing how one should learn to keep the beat by clapping the hands. The dancing master plays the pochette, a pocket violin, and the pupils practice the dance steps. Clapping was also advised by Rameau, who thought the practice useful in teaching the rhythmic difference between what he called ‘a true and a false cadence’. The pas de menuet, Rameau explained, was performed to two bars of triple time wherein ‘every first bar is the true cadence and the last the false’.23 To distinguish these, he recommended clapping the right hand against the left hand to mark the true cadence and lifting the left hand to mark the false one.

The Information i Dandsingen manuscript contains a basic introduction to the eighteenth century’s dance technique, the minuet as a dance, and some information about how to dance in general. It shows that dance teaching in Denmark in the mid-eighteenth century reflected the continental standard. The French dancing master Dulondel followed the French norm and his practice was likely influenced by Taubert.

The Minuet in Sven Henric Walcke’s Books

Sven Henric Walcke was a Swedish dancing master who worked a large part of his career in Norway from the 1790s to 1825. Walcke wrote two manuscripts containing dances, and while in Bergen, he authored and published one printed dance book. These are valuable sources of insight into Norway’s activity at this time. Walcke had also published two books in Sweden in 1782 and 1783. All five books contain information on the minuet.

Walcke’s Swedish Books

Walcke’s book Grunderne uti Dans-Kånsten [Basics in the Art of Dance] was published in Sweden in 1783. Here, he emphasized the importance of taking lessons with a dancing master who, in person, can easily teach the minuet steps, the manner of asking someone to dance, the turning, the style of holding hands, whereas, in writing, all of those things are difficult to make clear. Grunderne also contains a remark that the dancing master will show both minuet steps and steps for contradances in geometrical drawings.24 This information underscores Walcke’s idea that to learn how to dance the minuet properly and to understand the ceremonial gestures connected with it, students must take lessons with a dancing master. The inclusion of the remark on geometrical drawings points to one of his teaching methods: several sources note that Walcke made drawings in chalk on the floor so that the students could practise the steps by themselves.25

Walcke did not explicitly explain the minuet step in his books, but he has mentioned the dance several times in different contexts. All of these contribute to painting a picture of the importance of the minuet in his practice as a dancing master and a teacher, and that also reflects the European situation regarding the minuet.

In the Minnes-Bok uti Danskonsten [Memory Book for the Art of Dance] (1782), Walcke has included a list of minuet rules. These concern the positions of the feet while performing the minuet steps, keeping the beat, the bending and raising of the legs, and the turning. For instance, the dancing partners should always have their faces turned towards each other; ladies should hold the dress with their hands with straight arms and relaxed fingers; when asking someone to dance, it should be done by taking a few light steps out on the floor then performing a bow while looking at the desired potential dance partner. These rules show that the minuet should be performed according to a wider set of norms, the teaching of which was also considered to fall within the remit of the dancing master.

In the Memory Book, there is also a list of ten different kinds of minuets: the ordinary minuet, the single minuet, the double and single balance minuet, the figuré minuet, the coupé minuet, the masquerade minuet, the ballet minuet, the solo minuet, and a minuet for when royal persons are present.26 Walcke does not give any additional information about or explanations of these types. It is therefore difficult to know the characteristics of the various minuets and to ascertain the difference between them. However, it is quite clear that the ordinary minuet is the French menuet ordinaire. The double balance (‘Dubbel ballance’), figuré, and coupé minuets may imply versions with more elaborate steps and figures added to them. Taubert has described several different ways to replace the minuet steps with other steps, such as balancés, contretemps, or fleurets.27 When many such replacements of steps and changes in the figures are made, the dance is usually called a ‘figured minuet’.28

The Single and Double Balance Minuet—Some Hypotheses

The adjectives ‘single’ and ‘double’ minuet do not make sense in themselves. Still, some possible interpretations of the dance called the ‘double balance’ may be reasoned out. These variations on the minuet may contain the step ‘balancé’ and, in that way, could be an example of minuet steps being replaced, as Taubert has described. Alternatively, the names could imply that some parts of the minuet, or some minuet steps, should be performed on the same spot, similar to the concept of balancé in contradances. This minuet step then resembles a step in the Finnish minuet. Petri Hoppu has described a minuet step from Lappfjärd, Finland that has this characteristic:

Bar 1: Step forward with R foot (1), which has in the previous step been dragged past L foot. The step is toward partner, with toes pointed forward, and almost no swinging of the body. Move L foot lightly to heel of R foot (2), i.e., with no bodyweight. Step back with L foot (3) to original place.

Bar 2: Step back with R foot (4), with almost no body swing. Lift L foot, and return to the floor on the same spot (5). Drag R foot past L foot (6), ready to step onto it on the next beat.29

Here, the dancer moves forward and back in the same step. This pattern may be similar to the steps included in the balance minuet.

The Minuet in Contradances

In addition to the minuets resembling the ordinary minuet, there are numerous examples of elements of the minuet being integrated into contradances. A contradance may be a minuet from the beginning to the end, i.e., the whole dance may contain minuet steps and music. However, minuets can also be the last part, or final figure, of a contradance. This merging of dance types occurs in the Nordic countries as well as the European context. In the dance book published in Bergen, his Book of Figure Dances (1802), Walcke published contradances and some of the English dances have the minuet as one of their last figures.30 Since there are no tunes in this book, it is difficult to determine how the dance may have related to the music. However, there is a description of the minuet as part of a contradance in a manuscript from 1804, where the music for the contradance is written in 3/8 time, which is the metre for waltz at this time. When the minuet comes, the music is changed to 3/4, reverting to 3/8 when the minuet part is over.31

That the minuet was an integrated part of the contradance repertoire implies that the minuet was well established in the dancers’ repertoire. Otherwise, it would be too difficult for them to adapt their rhythms and movements to perform the minuet steps simply for a few bars between the figures of the contradance.

The Squared Minuet

In addition to the relatively significant number of contradances wherein passages of the minuet are included within the rest of the figures, some contradances were made up entirely by the minuet, from beginning to end.

The squared minuet (Den 4re kantede Menuetten) is a notable find in the Norwegian source material in this regard: it is the only known description of a contradance that is wholly a minuet. It is a minuet for eight persons and is danced in a square formation as in a quadrille. The dance description from 1816 contains information for male and female partners for each figure of the dance.32

In the first figure, all couples perform a bow and curtsy. Then the dancers take their partner’s hands. The descriptions of the subsequent figures specify several additional minuet steps, indicating when dancers are to move on the spot (dancing in place), towards the middle of the square, across the floor, or to turn and dance sideways and backward steps in different directions. These figures contain diagonals, corners of the square, and ways of turning and holding both hands, which points towards their origins in the ordinary minuet.33 This source exemplifies how the classical minuet and its educational qualities were accommodated within the contradance.

Martinet’s Description of the Minuet Steps

J. J. Martinet was a dancing master in Lausanne who published the dance manual Essai, ou Principes Elementaires de l’Art de la Danse [Essay, or Basic Principles for the Art of Dancing] (1797). The book was translated into Danish and published in Copenhagen in 1801. It contains some paragraphs on the minuet among the information on how to stand, walk, and perform bows and dance steps.

Martinet’s book marks a shift in the purpose of publishing dance manuals. Whereas earlier dance books were intended for pupils who had taken dance classes and might use the book to remember what they had learned, Martinet’s book was directed also to those who wanted their children to learn to dance but did not have a dancing master to teach them. The ability to learn to dance the dancing masters’ repertoire without necessarily taking dance lessons reflected a shift in the position of the minuet. What was once a skill and activity only for the court and the elite was being made accessible to the lower classes of society.

Martinet wrote that the minuet had been abandoned for a long time and was hardly used as a ballroom dance anymore. However, he stated that the minuet included all the basics of dancing and that it was easy to prove that one could not dance well if he or she had not learned the minuet. The minuet developed the limbs and gave a beautiful contour, power, and regularity to the movements and developed the balance. Martinet recommended practising the minuet to avoid stiff body postures and turns, unstable walking, and movements he liked those of mechanical dolls or automata. He thought that the minuet was to dance what the ABCs are to words and speech (‘som A. B. C. for Ordene og Talen’).34

According to Martinet, the minuet consisted of three fundamental steps that repeated many times. The three steps were the forward step, the sideways step to the right, and the sideways step to the left. Martinet called these ‘complete steps’, explaining that a ‘complete minuet step’ consists of ‘bendings, slidings, [walking] steps, and stretchings’.

|

Video 9.1 ‘Ballet Glossary—Feet Positions’, The Royal Opera House. Uploaded by the Royal Opera House, 25 February 2011. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/55cc685e |

Martinet’s description of the minuet step starts from the third position with the right foot in front, a straight body and head with the chin pulled back, the shoulders pulled back, and straight knees. ‘Then bent [knees], slide the right foot forward into the fourth position, bent [knees], slide the left foot forward into the fourth position, then two steps, stretched in the fourth position forward.’ The knees must be extended after every bending.

Both slidings should be made together with the knees’ bending, so that the foot slid changeably with the tip [of the toes]. Place the ball of the foot straight in the fourth position so that one completed the first half with a bending and the second half with stretched knees in a slow and even movement in the time of first four quarter notes of both bars [of the minuet step].

This places each bending on the last two quarter notes of both bars. Both steps which comprise the minuet step should be made placing the feet in the fourth position, with a quick movement, and with straight knees on the last two quarter notes of the 2 bars, so that each step was performed to one beat of the bar.

The ordinary minuet step (Martinet)

|

6 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

3 |

|

|

4 |

step with the right foot |

|

5 |

step with the left foot |

The sideways step to the right starts from the third position, then a plié slides the right foot into the second position, while the left foot remains in the same line without lifting from the floor, stretching the dancer’s knees until half the length of the second position after six inches (tommer) from the right foot. And in one movement, plié, then the left foot in the third position behind the right, and then two steps to the right side with straight knees, one step in the second position and one step in the third position behind the right foot.

The sideways step to the right (Martinet)

|

6 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

3 |

|

|

4 |

|

|

5 |

|

Concerning the sideways step to the left, Martinet wrote that the two steps in the sideways steps to the left are not equal steps like the sideways steps to the right. The left steps start from a plié, then slide the right foot into the fourth position forward and quickly pull the left foot with straight knees into the first position; then again plié, slide the left foot into the second position and then take two straight steps to the left side, one with the right foot in the third position behind the left and one with the left foot in the third position. This is the first complete sideways step.

The sideways step to the left, version 1 (Martinet)

|

6 |

|

|

1 |

slide the right foot to 4th position forward and pull the left foot to 1st position |

|

2 |

|

|

3 |

|

|

4 |

step with the right foot to the left side, to 3rd position behind |

|

5 |

|

The second version of the sideways step to the left is described starting from the second position:

Starting with a plié, then placing the right foot behind the left in the third position so that one pulls quickly the same [foot, i.e., the left] backwards with the tip [of the toe]. Then one rises on both feet in the same position with relatively straight knees and holds [this position] for the rest of the ‘plié bar’. Then plié, slide the left foot to the second position and do two straight steps where one is performed with the right foot in the third position behind the left foot and the second step with the left foot in the second position.35

The sideways step to the left, version 2 (Martinet)

|

6 |

|

|

1 |

place the right foot behind the left in 3rd position and pull the left foot backwards |

|

2 |

rise on both feet |

|

3 |

|

|

4 |

step with the right foot to 3rd position behind the left foot |

|

5 |

|

Martinet wrote that the minuet belongs to the category of solemn [alvorlige] dances. This category included the pantomime, simple and figured minuets, Menuet Dauphin, Menuet de la Cour, two kinds of passepieds, and so on. As opposed to the solemn dances, he set the category of joyful [muntre] dances, which included, for example, Entrées de ballet, branles, contradances, and the waltz.36

Pierre Jean Laurent’s Minuet Drawings

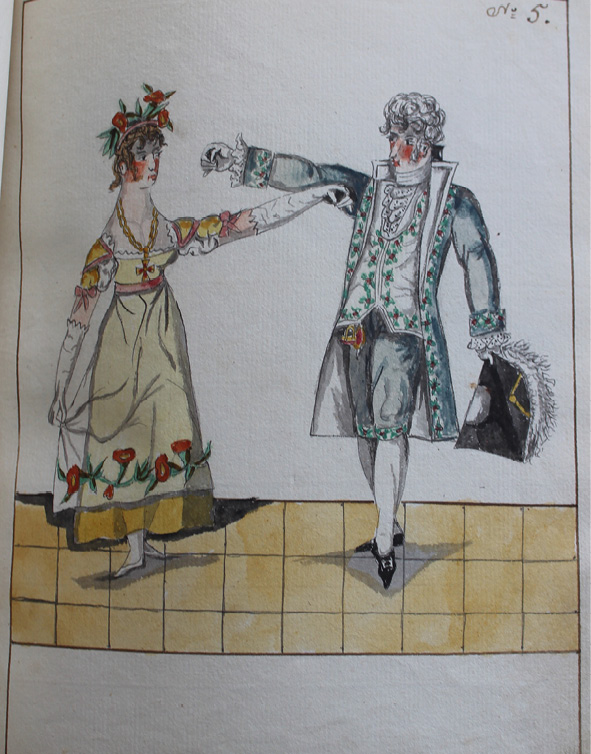

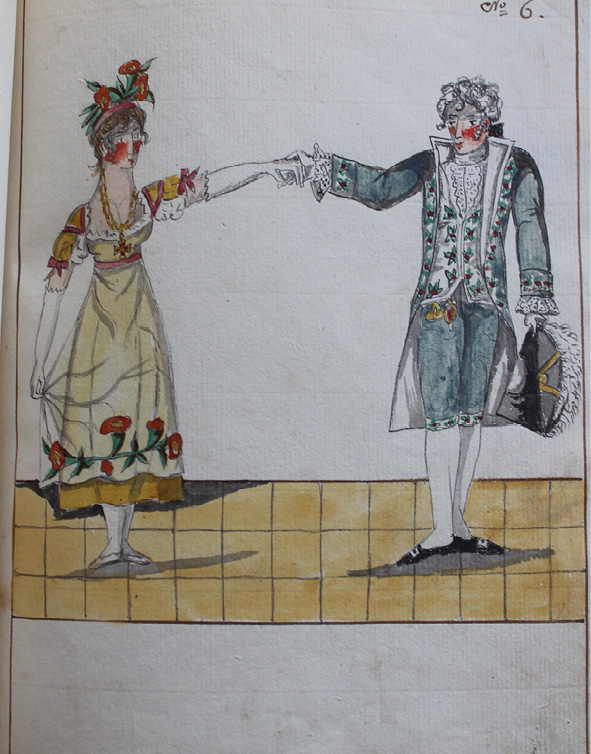

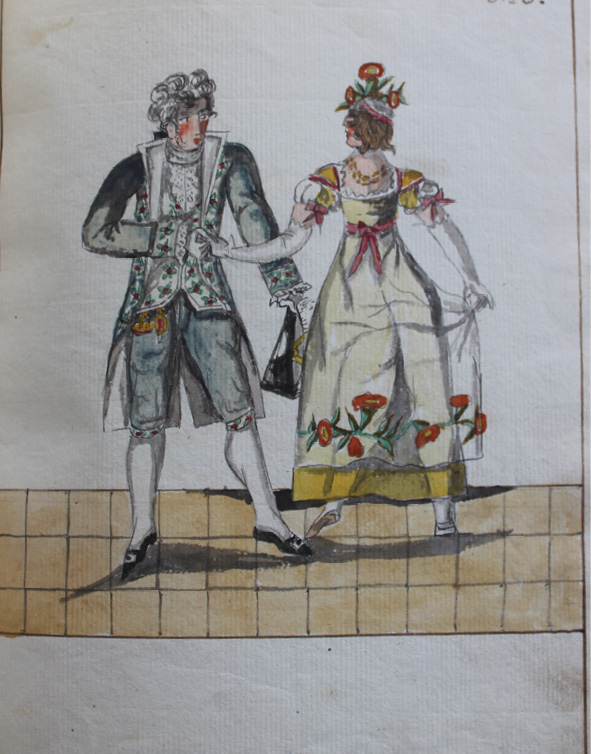

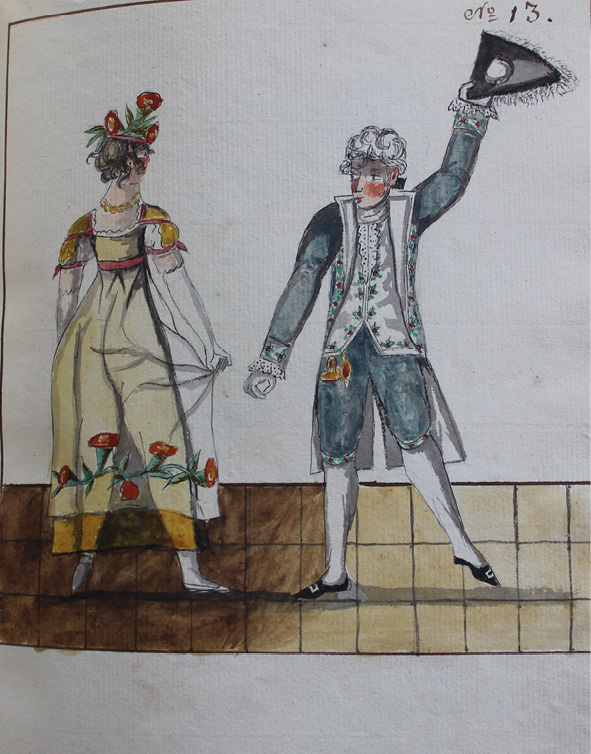

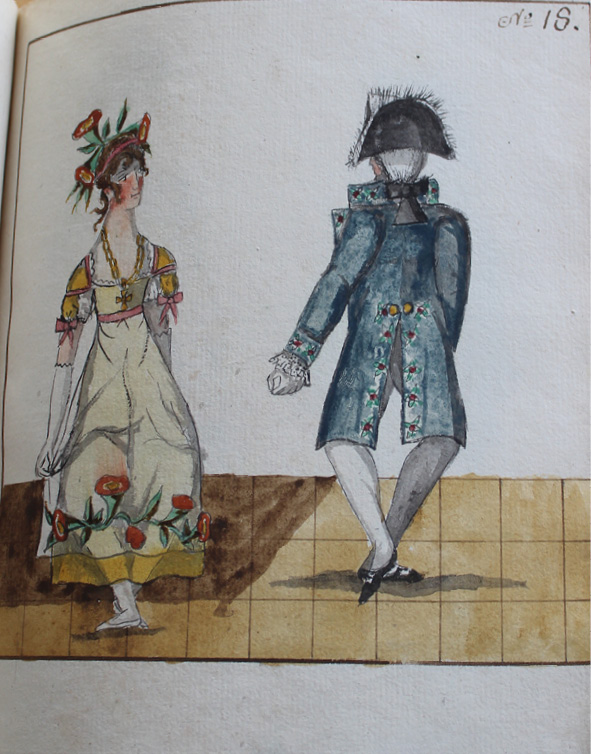

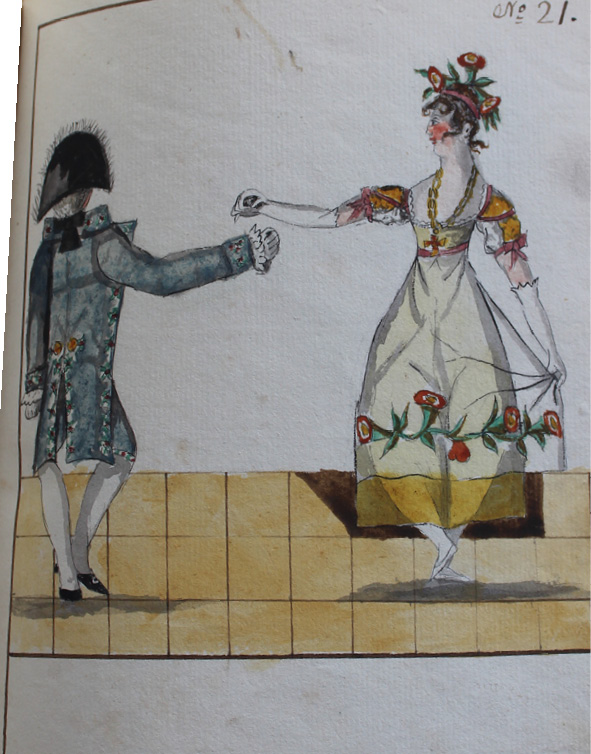

A manuscript by the dancing master Pierre Jean Laurent called Weiledning ved Underviisning i Menuetten [A Guide for Teaching the Minuet] is preserved in the collection at the Royal Library in Copenhagen.37 The text in the book can be dated to around 1816.38 The manuscript contains a set of coloured drawings of a couple dancing the minuet, and dance scholar Henning Urup has published on the manuscript several times.39 Laurent included information on ancient dance history and some information about his career in the manuscript, but, apart from the images, he did not include in the manuscript any information about the minuet.40 The Royal Danish Library has given us the permission to use the photographs of these drawings, taken by Elizabeth Svarstad, in our book.

In the manuscript, sixteen drawings depict a couple performing the minuet. Each illustration is coloured and is given an entire page in the book. In what follows, we have attempted to describe the pictures and give a sketch of the positions, figures, spacing, and the relationship between the dancers. Many of the drawing are relatively easy to interpret with regard to the movements of the dancers and their relation to the other’s position. Some drawings, however, are less clear about how the dancers stand, in which direction they are moving, and where the feet are pointing. Our description, therefore, must be understood as one of several possible interpretations of these illustrations.

Throughout, the man is shown in a typical eighteenth-century costume with short pants, vest, and jacket in a light grey colour, all decorated with flower embroidery. His shirt is white with lots of ruffles, and he is holding a three-cornered hat. The lady’s dress has an early-nineteenth-century style: it has a long skirt in a light and almost transparent fabric, with a ribbon or belt marking a high waist. Her dress is decorated with flowers, matching those in her hair. She is also wearing long white gloves.

Fig. 9.1 Laurent’s drawing 1. The couple side by side, the man a little further back than the lady. They are facing front but looking towards each other. They are both standing on the left foot and pointing the right foot in front of the left. The man is holding his hat in his left hand. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad.

© Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.2 Laurent’s drawing 2. The man stands in the first position performing a bow by bending his head forward. The lady stands in the third position with the left foot in front. She is curtsying by bending her knees to the side, and she is also looking down to the floor, still holding her dress with both hands. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.3 Laurent’s drawing 3. The man stands on his right foot with the left foot pointed in front. The lady does the opposite, standing on the left foot and pointing the right foot in front. This picture shows the couple taking a step forward on the outer leg. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.4 Laurent’s drawing 4. The couple stand facing each other. The man stands in the first position performing another bow, but this bow is directed towards the lady. The lady stands in the third position with the right foot in front, performing a curtsy by bending the knees in the same way as in picture number two, but now looking towards the man. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad.

© Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.5 Laurent’s drawing 5. The couple stretch out the arm to the side; the man has stretched his right arm, and the lady has stretched out her left. They stand in the fourth position; the man on his right foot pointing the left foot in front, and the lady on her left foot with the right foot turned out to the side in front of the left. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.6 Laurent’s drawing 6. Both stand in the third position with both feet on the floor. The left foot is behind, and the right foot is in front. They are holding hands and looking at each other. They are holding their arms relatively high. The man has slightly bent his elbow while the lady has her arm quite stretched. The man is still holding his hat in the left hand, and the lady is still holding her dress with her right hand. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.7 Laurent’s drawing 7. The partners are still holding hands. They seem to always be in the third position, but they have now bent their knees, and they both seem to lean a little bit away from each other. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.8 Laurent’s drawing 8. The man faces front, but he is now on the other side of the lady. He is standing in the second position on the right toe and pointing the left foot as if he has just taken a step to the right side. He is still holding the lady in his right hand and the hat in his left. The lady is now turned so that we see her back. She is standing on her right foot, pointing the left foot to the side. She holds the man’s right hand with her left, looking at him. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad.

© Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.9 Laurent’s drawing 9. The couple have released the hands. At this point, the man is standing but facing the back of the room so that we see his back. He is standing in the third position with his right foot in front. The lady is facing the front of the room, also standing in the third position with her right foot in front, holding her dress with both hands. This illustration most likely depicts the couple performing the Z-figure of the minuet. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad.

© Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.10 Laurent’s drawing 10. The couple have passed each other, probably on the Z-figure’s diagonal line. They both stand on their right foot, and their left feet seem to be pointed behind their right feet. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad.

© Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.11 Laurent’s drawing 11. The couple are back-to-back. The lady is standing on her left foot, stretching the right foot in front. The man seems to be standing on his right foot, with the left foot pointed either behind or to the side. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.12 Laurent’s drawing 12. The couple have turned around and face each other, but they stand in opposite corners. Both stand on the right foot, stretching and pointing the left foot to the side. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad.

© Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.13 Laurent’s drawing 13. The partners have changed places, but they both stand on the right foot, pointing the left foot to the side. The man has lifted his left arm, in which he holds the hat, high up. The lady faces the back of the room so that we see her back. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.14 Laurent’s drawing 14. The couple is depicted closer to each other. The man is standing on his left leg with his right leg in front and off the floor. The hat is on his head, and he is holding it with the left hand. The lady seems to be standing on her right leg, but with her left leg behind her. They seem to be about to pass each other back-to-back. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad.

© Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.15 Laurent’s drawing 15. They are both standing on their right legs with their left legs pointed to the side (the man’s foot seems to be a little more to the back than the lady’s) as if they are performing a sideways step. The man is facing the back of the room while the lady is facing the front. The man has held his arm out to the side, and he seems to be about to lower the arm after putting the hat on his head. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.16 Laurent’s drawing 16. The man and lady have changed sides. They seem to be standing on their left legs in plié with their right feet off the floor, about to take the next step to the right. The man faces the back of the room, and the lady is turned front, but they are looking at each other. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.17 Laurent’s drawing 17. They are in almost the same positions as picture number sixteen, but they are now standing on their left legs, pointing their right feet in front. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.18 Laurent’s drawing 18. The man and lady each stand on their right foot in plié with the left foot behind. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.19 Laurent’s drawing 19. They stand on the right foot’s demi-point with the left foot pointed to the side. The man is facing the back of the room, and the lady is facing the front. They seem to be standing in what is often called ‘the corners’ from where dancers start or end the Z-figure. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.20 Laurent’s drawing 20. They each stand on the left leg with the right pointed behind and seem to be moving towards each other on the diagonal line from the corners in which they were standing in picture number 19. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.21 Laurent’s drawing 21. They both stand on their left leg with the right foot lifted off the floor. They have changed places again, and now they are both stretching their right hand out to the side towards each other. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.22 Laurent’s drawing 22. They stand on their right feet with their left feet pointed behind. They are holding right hands. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.23 Laurent’s drawing 23. They stand on the right foot with the left foot pointed to the side or slightly back. They still hold the right hands but have moved closer to each other causing their elbows to bend as if they have moved towards each other and turned the left shoulder towards the middle. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.24 Laurent’s drawing 24. The dancers each stand on their left foot with their right lifted off the floor as in the middle of a sideways step to the right side. They seem to move to or from the corner from where the minuet figures start or end, and they have their left arms stretched out towards each other. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.25 Laurent’s drawing 25. They seem to stand in the first position almost side by side. They now hold left hands, and the man has bent his elbow so that the dancers are relatively close to each other. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.26 Laurent’s drawing 26. The dancers each stand on their right leg, pointing the left to the side, and seem to move away from each other. They have let go of their partner’s left hand, but they still hold their arms to the side as they are about to lower them. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.27 Laurent’s drawing 27. The dancers are standing on their right legs with their left feet pointed to the side or behind. They seem to move on the diagonal. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.28 Laurent’s drawing 28. They cross each other back-to-back in the middle of the room. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.29 There is no drawing No. 29 in the manuscript. The page may be missing, or Laurent may have skipped the number 29 by mistake. On other pages in the manuscript, Laurent has corrected the numbers, such as picture number 14 and 26, and 27. It is unclear whether a drawing number 29 is missing or not. In Laurent’s drawing 30, the couple stands in the third position with their left legs in front. The man faces the front, while the lady faces the back of the room. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.30 Laurent’s drawing 31. They each stand on their left foot in plié with the right foot lifted in front. They have both stretched out both arms and are about to perform the figure called presenting both hands. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad.

© Royal Danish Library.

Fig. 9.31 Laurent’s drawing 32. They have both turned to face the front of the room, and the man holds the lady’s left hand in his right hand. The picture shows the minuet’s concluding position, and the couple appears to be about to perform the bow and curtsy. Photograph by Elizabeth Svarstad. © Royal Danish Library.

Jørgen Gad Lund’s Minuet

Jørgen Gad Lund, as we have seen in earlier chapters, was a Danish dancing master who published a dance book Terpsichore, eller: En Veiledning for mine Dandselærlinger til at beholde de Trin og Toure i Hukommelsen, som de under mig have gjennemgaaet [Terpsichore, or a Guide to for my Dance Pupils for Remembering the Steps and Figures I have Taught Them] in three editions from 1823 to 1833.41 The book was first published in Mariboe, Denmark in 1823, and a second and third editions were published in 1827 and 1833, respectively.42 Lund included a description of a whole minuet for several couples, reproduced here in translation:

One stands side by side in the fifth position, the ladies on the right. One bends the knees, then slide the right foot to the side, pull the left [foot] to the [right], and perform a bow and curtsy [Compliment]. Now the man puts the left foot backwards to the fourth position, and the lady puts the right [foot backwards to the fourth position]. Then they turn towards each other by sliding the foot forward which had been in the fourth position into the third position. They take a step forward, the lady with the right foot and the man with the left. Then they each pull their other foot towards themselves and take another bow and curtsy.

The man offers his right hand to the lady, who puts her left [hand] in his. Then they take one step backwards, the man with the right [foot] and the lady with the left foot and then they take three faster steps so that these three [steps] do not take more than one bar. In the last [step], they turn and stand the way they started.

[They] take a slow step forward with the right foot, then take three quicker [steps], which starts on the left foot. The man leads his lady around, while she makes first a slow step, then three fast steps, another slow step, and then releases his hand while she steps back and stands on the side where they started the minuet. While the lady walks around, the man takes a slow step to the right side, then three faster steps around while turning his face to the lady. Again he takes a slow step, and then he steps back while letting her go, and [he] stands on the opposite side of where they started, facing his partner.

Now they perform the minuet steps, which are as follows: first, one bends the knees and slides the right foot to the side and stretch the left tip of the toe towards the floor, and this takes one bar. Then one takes three faster steps to the right side: starting with the left foot and pulling it behind the right [foot] in the fifth position, the right to the side again, and once more the left [foot] behind as before. This takes the second bar. Now a slow step to the right side, like the first time in the third bar, then slide the left foot backwards to the fourth position while turning the body towards the person with whom one is dancing with, and stretch the right tip of the toe towards the floor, and now the four bars are completed.

Now one slides the left foot forward to the third position while turning straight in (facing) the quadrille, rising a little on the toes and then lowering the whole foot again. This is the fifth bar. Now one takes three faster steps to the left side: bending the knees and sliding the left foot to the second position, then the right foot behind in the third [position] and again the left [foot] to the side so that they end the sixth bar with the right foot in the second position, the tip of the toe towards the floor.

Now one pulls the right foot backwards into the fifth position while bending the knees, rise on the toes, and lower the foot. This is the seventh bar. Now one takes three fast steps again to the left side, as before, and this is the eighth bar. One slides the right foot into the first position and then forward to the fourth [position] to carry the full weight of the body. The left [foot] must be stretched behind. This is the ninth bar. Then three fast steps across the floor, passing the [person] with whom one was dancing, who must be on the right side, Now the tenth bar is completed.

Again a slow step forward with the right foot in the eleventh bar, as in the ninth [bar]. Now one places the left foot in front in the fourth position, and slide then the right foot forward into the fifth position while turning to the left. Finally, one starts the steps to the right side again.

In the minuet, there can be as many couples side by side as space allows. When one has danced the steps some times on each side, then one must make sure, that when one is on the side where one was standing when one let go of each other, then, when one wants to go across the floor, then do a turn firstly holding the right hands. One raises the right arm while making a slow step forward on the right foot, then make the three quick [steps] while giving the hand to the person one is dancing with. Now take a slow [step] around and again three quick [steps] while letting go of each other and standing on the place where one started. After this, the steps are being done to the right side, then give the left hands to each other, precisely in the same manner as with the right [hand] previously.

At this point, the steps are being done to the right and left side and across the floor, passing each other. Now the man should be standing on the side where he started the minuet and the lady [should be standing] on the other side. Again to the right and left side. Then one raises the arms and walk towards each other, taking one slow and three fast steps while giving each other both hands and stand facing each other. Then a slow step to the side, the man to the right, and the lady to the left. Then three quick steps to the same side and turn, in the same way they were standing when then minuet started.

Next, a step to the right side and take a bow and curtsy. Then [move] the foot backwards to the fourth position, like in the beginning: one now turns towards one another and makes a step to the side, like in the beginning, while taking a bow and curtsy to each other, completing the minuet.

While dancing the minuet, one must always keep one’s face towards the one with whom one is dancing with. The body must be held very upright, though without being stiff. The lady holds her dress in her hands, and the man lets his arms hang at his side. You must endeavour to be careful and carry your body with becoming grace! Because this dance is the most important of all. If you can perform it with grace and grandeur, then all the other dances will be easy for you. Every dance is dependent on fashion, but even though more popular [stormende] dances have displaced the minuet, it still is the most beautiful of all.

Janny Isachsen’s Minuet

A dance manual was published by dance teacher Janny Isachsen (1835–94) in Christiania (Oslo) in 1886. Isachsen was an actress in Bergen and Christiania for twenty years, beginning in 1852. After leaving the stage, she became a dance teacher.

The book, Lommebog for Dansende [Pocketbook for Dancers], contains descriptions of several dances in fashion around the 1880s, such as the lanciers, française, and fandango. Isachsen’s description of the minuet shows that it still was in practice in being taught towards the end of the nineteenth century. The minuet is described in five sections: an introduction, three tours, and a conclusion. The different steps are also described.

The dance begins with the couples standing side by side in the first position. All the dancers take a step to the right in the introduction, then close with the left foot and perform a bow and curtsy (compliment). Left foot a step backward to face each other. Three small steps to the right and a compliment. Then the left foot to the left, walk three small steps with the right foot behind the left, then turn in to form a line. The man and lady give a right hand and turn three times, starting with the right foot and continue with three small steps to the right, always with the left foot behind the right. Man and lady to the opposite places with three backward steps to form two lines of men and ladies on each line.

The first figure begins with a description of the long pas menuet: the men and women take one step and three small steps to the right and a compliment. Then make three short steps to the right, and then forward on the right foot while looking at each other. The same is repeated back again to the left until the lady and the man stand in front of each other.

The next paragraph describes a figure called travacé:

Step on the right foot and walk three small steps. All turn on the left foot and remain standing on the right, shoulder to shoulder. Again step out on the left foot, three short steps, turn back again into the opposite line.

The short pas menuet (with the right hand) is described as all take a step to the right, three small steps to the right, forward on the right foot looking at the man, back on the left, give the right hand, three steps towards each other, take hands, turn a whole turn, continue turning on the left foot into the opposite line.

The second and third figures are described in the same way as the first figure, except that in the second figure, the short pas menuet, they hold their partner’s left hand within their own left hand and then hold both of their partner’s hands in the third figure.

In the conclusion of the minuet, all take a step to the right, close with the left foot and a compliment. Take a step back on the left and stand in front of each other, three short steps to the right, and compliment. Take a step on the left foot again, walk three short steps with the right behind the left, turn in to stand on one line. Finish with a compliment.43

The instructions in Isachsen’s manual describe a minuet that shares many similarities with the ordinary minuet. What is different is mainly that it is a dance for several couples at one time. According to the descriptions, many steps closely resemble those of the ordinary minuet. However, some of the Isachsen’s minuet steps begin on the left foot, which would not happen in the ordinary minuet during the eighteenth century. The figures in this dance have the characteristic forms of an introduction and the taking of first the right hand, then the left, and then both hands. The travacé tours in between the taking of hands make the partners change places, and the pattern would correspond to the Z-figure of the ordinary minuet. The commonalities show the connection to the former minuet, and at the same time, Isachsen’s description offers information on the development of the minuet over the course of the eighteenth century.

The minuet Isachsen describes is extremely similar to that represented in Jørgen Gad Lund’s book Terpsichore, which was published in Denmark several decades earlier. Isachsen’s minuet may very well be an example of a development of Lund’s minuet.

Concluding Remarks

Sources for dance and music show that the minuet was both a dance practice and an educational dance taught by Nordic dancing masters. It was regarded as a classical dance with educational qualities. The ordinary minuet, le menuet ordinaire, was danced in the same way in the Nordic countries as elsewhere in Europe during the eighteenth century. Soon after the French Revolution in 1789, the minuet lost its status as the main dance at the ball due to its strong ties to the French aristocracy. Dancing masters continued to teach it, however, because they considered the minuet essential to the establishment of good posture and elegant movements. It was regarded as the best method for developing a strong technique and a sound basis for performing other dances in fashion, such as contradances and the waltz.

By presenting the French minuet tradition and giving examples of how it is reflected in Nordic sources, we have attempted to trace minuet practice in the Nordic countries in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as well as its development in use and popularity over approximately one hundred fifty years. The different pieces of information on the practice and the value of this dance in the sources presented here show the minuet’s existence and indicate its importance in terms of repertoire, as a method for education and polite manners and for developing basic dance skills.

References

Archival material

National Library of Norway, Oslo

Mus.ms. 295, Svend H. Walcke, ‘Dansebok’ (1804)

Mus.ms. 299, Svend H. Walcke, ‘Musik og Tuure Bog medelt[?] inhentede Lærdomme for mine Elever udi Dands og afgivet av mig S. H. Walcke Aaret 1816,’ (1816)

Royal Danish Library

Acc. 2012/28, Håndskriftsamlingen. Laurent, Pierre Jean, ‘Weiledning ved Underviisning i Menuetten tilligemed en kort Underretning om dens Oprindelse og Fremgang blandt forskjellige Nationer’

Special Collections, Gunnerus Library, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim

XA HA Qv. 80n. Information i Dandsingen av. Mons. Dulondel

Secondary Sources

Anonymous, The Extraordinary Dance Book T B. 1826. An Anonymous Manuscript in Facsimile, Commentaries and analyses by Elizabeth Aldrich, Sandra Noll Hammond, and Armand Russell. Dance & Music Series No. 11. Stuyvesant (New York: Pendragon Press, 2000)

Bakka, Egil, Europeisk dansehistorie: For VK 1 og VK 2 (Oslo: Gyldendal undervisning, 1997)

―, Norske dansetradisjonar (Oslo: Samlaget, 1978)

Bakka, Egil, Siri Mæland, and Elizabeth Svarstad, ‘Vertikalitet og den franske 1700-talls menuetten’, Folkdansforskning i Norden, 36 (2012), 38–46

Balon, Claude, and Jacques Dezais, XIII recueil de danses pour l’année 1715 (Paris: [n. pub.], 1714)

Brives, Nouvelle méthode pour apprendre l’art de la danse sans maitre (Toulouse: [n. pub.], 1779)

Elvestrand, Vegard, Generalkonduktør Christopher Hammer (1720–1804) og hans manuskriptsamling: Registratur, biografi, slektshistorie (Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag, 2004)

Feldtenstein, Carl Josef von, Erweiterung der Kunst nach der Chorographie zu tanzen, Tänze zu erfinden, und aufzusetzen, wie auch Anweisung zu verschiedenen National-Tänzen als zu Englischen, Deutschen, Schwäbischen, Pohlnischen, Hannak- Masur- Kosak- und Hungarischen mit Kupfern nebst einer Anzahl Englischer Tänze (Braunschweig: [n. pub.], 1772)

Feuillet, Raoul-Auger, Ve Recueil de dances de bal pour l’année 1707, recueillies et mises au jour par M. Feuillet (Paris: [n. pub.], 1707).

Gorset, Hans Olav, ‘Fornøyelig Tiids-Fordriv’: Musikk i norske notebøker fra 1700-tallet: Beskrivelse, diskusjon og musikalsk presentasjon i et oppføringspraktisk perspektiv (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Norges musikkhøgskole, 2011)

Hauch, Carsten, Minder fra min Barndom og min Ungdom: Med et Prospect af Malmanger Prestegaard (København: Reitzel, 1867)

Huitfeldt-Kaas, Henrik Jørgen, ‘Om Familien Brochmann i Norge’, Personalhistorisk Tidsskrift, 16 (1895), 249–74

Isachsen, Janny, Lommebog for Dansende (Kristiania: Cammermeyer, 1886)

Link, Georg, Vollkommene Tanzschule aller in Kompagnien und Bällen vorkommenden Tänzen (1796)

Lund, Jørgen Gad. Terpsichore, eller: En Veiledning for mine Dandselærlinger, til at beholde de Trin og Toure i Hukommelsen, som de hos mig have gjennemgaaet (Mariboe: C.E. Schultz, 1823).

Martinet, J. J., Begyndelsesgrunde i Dandsekonsten: Bestemt til nyttig Selvøvelse, og for de Forældre som ej holde Dandsemester til deres Børn, trans. by C. H. Lund (Kiøbenhavn: L. Reistrups Forlag, 1801)

Ogasapian, John, Music of the Colonial and Revolutionary Era (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004)

Pfitzinger, Scott, Playford’s Dancing Master: The Complete Dance Guide An exhaustive collection, catalogue, and index of all dances published in editions of the Dancing Master, 1651-1728 (2019), http://playforddances.com

Rameau, Pierre, Le maître à danser (Paris: Jean Villette, 1725; repr. New York: Broude Brothers, 1967)

Rameau, Pierre, The Dancing Master, trans. by Cyril W. Beaumont (Alton: Dance Books, 2003)

Russell, Tilden, and Dominique Bourassa, The menuet de la cour (Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 2007)

Saltator, A Treatise on Dancing (Boston: The Commercial Gazette, 1802)

Sinding-Larsen, Fredrik, Den Norske Krigsskoles Historie i ældre Tider (Kristiania: Cammermeyer, 1900)

Svarstad, Elizabeth, ‘Aqquratesse i alt af Dands og Triin og Opførsel’ Dans som sosial dannelse i Norge 1750–1820 (doctoral dissertation, The Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2017)

―, ‘Transkripsjon av og kommentar til Pierre Jean Laurents dansebok’, Folkdansforskning I Norden, 40 (2017), 14–19

Taubert, Gottfried, Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister, oder gründliche Erklärung der frantzösischen Tantz-Kunst (Leipzig: Friedrich Lanckischens Erben, 1717)

Taubert, Karl Heinz, Das Menuett. Geschichte und Choreographie (Zürich: Pan, 1988).

Tomlinson, Kellom, The Art of Dancing: Explained by Reading and Figures; Whereby the Manner of Performing theSsteps is Made Easy by a New and Familiar Method (London: the Author, 1735)

Urup, Henning, Dans i Danmark: Danseformerne ca. 1600 til 1950 (København: Museum Tusculanums Forlag, 2007)

Walcke, Sven Henric, Grunderne uti Dans-Kånsten, til Begynnares Tjenst (Götheborg: L. Wahlström, 1783)

―, Minnes-Bok uti Danskonsten (Nyköping: Carl Hasselrot, 1782)

―, Toure-Bog af Engelsk- og Contra-Dandse for mine Elever (Bergen: Hans Kongel. Majestæts priviligerede Bogtrykkerie, 1802)

1 Egil Bakka, Europeisk Dansehistorie: For VK 1 og VK 2 (Oslo: Gyldendal undervisning, 1997), p. 117.

2 Martinet has the initials J. J. in the original French version whereas they are J. F. in the Danish translation.

3 Pierre Rameau, Le maître à danser (Paris: Jean Villette, 1725; repr., New York: Broude Brothers, 1967), pp. 49–54.

4 Tilden Russell and Dominique Bourassa, The Menuet de la Cour (Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 2007), p. 3.

5 The term contradance refers to a large dance form and paradigm of group dances popular in Europe and other parts of the world, especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In English, they are sometimes referred to as country dances. They are danced in sets of dancers, usually composed of couples, with typically four up to sixty individuals in each.

6 The term figure corresponds mostly to the French term tour, and the Scandinavian derivation tur. The terms were used to signify the dance patterns corresponding to a reprise—usually eight bars of music but could also be used for shorter or longer sequences of a dance.

7 Rameau, Le maître à danser, p. 51.

8 C. J. von Feldtenstein, Erweiterung der Kunst Nach der Choreographie zu Tanzen (Braunschweig: [n.pub.], 1772), p. 80.

9 Karl Heinz Taubert, Das Menuett. Geschichte und Choreographie (Zürich: Pan, 1988), p. 82.

10 Russell and Bourassa, p. 3.

11 Gottfried Taubert, Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister, Oder Gründliche Erklärung der Frantzösischen Tantz-Kunst (Leipzig: Friedrich Lanckischens Erben, 1717), p. 379; about Menuet d’Espagne, see also Claude Balon and Jacques Dezais, XIII Recueil de Danses pour l‘Année 1715 (Paris: [n. pub.], 1714), pp. 8–14.

12 Russell and Bourassa, p. 18.

13 Raoul Auger Feuillet, Ve Recueil de Dances de Bal pour l‘Année 1707, Recueillies et Mises au Jour par M. Feuillet (Paris: [n. pub.], 1707); Georg Link, Vollkommene Tanzschule aller in Kompagnien und Bällen Vorkommenden Tänzen (1796).

14 John Ogasapian, Music of the Colonial and Revolutionary Era (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004), p. 102.

15 Scott Pfitzinger-Kumle, Playford’s Dancing Master: The Complete Dance Guide: An Exhaustive Collection, Catalogue, and Index of all Dances Published in Editions of the Dancing Master, 1651–1728 (2019), http://playforddances.com

16 Ibid.

17 Anonymous, The Extraordinary Dance Book T B. 1826. An Anonymous Manuscript in Facsimile, Commentaries and analyses by Elizabeth Aldrich, Sandra Noll Hammond, and Armand Russell. Dance & Music Series No. 11. Stuyvesant (New York: Pendragon Press, 2000), p. 118; Brives, Nouvelle Méthode Pour Apprendre l’art de la Danse Sans Maitre (Toulouse : [n.pub.], 1779), pp. 20–25; Saltator, A Treatise on Dancing (Boston: The Commercial Gazette, 1802), p. 73.

18 Elizabeth Svarstad, ‘Aqquratesse i alt af Dands og Triin og Opførsel.’ Dans Som Sosial Dannelse i Norge 1750–1820 (unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2017), pp. 176–88.

19 Vegard Elvestrand, Generalkonduktør Christopher Hammer (1720–1804) og hans manuskriptsamling: Registratur, biografi, slektshistorie (Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag, 2004), p. 193.

20 Ibid.

21 Egil Bakka, Norske Dansetradisjonar (Oslo: Samlaget, 1978), p. 27.

22 Special Collections, Gunnerus Library, The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim: XA HA Qv. 80n. Information i Dandsingen av. Mons. Dulondel.

23 Pierre Rameau, The Dancing Master, trans. by Cyril W. Beaumont (Alton: Dance Books, 2003), p. 66.

24 Sven Henric Walcke, Grunderne uti Dans-Kånsten, til Begynnares Tjenst (Götheborg: L. Wahlström, 1783), Chapter II.

25 Henrik Jørgen Huitfeldt-Kaas, ‘Om Familien Brochmann i Norge’, Personalhistorisk Tidsskrift 16 (1895), 249–274; Fredrik Sinding-Larsen, Den Norske Krigsskoles Historie i ældre Tider (Kristiania: Cammermeyer, 1900), p. 116; Carsten Hauch, Minder fra min Barndom og min Ungdom: Med et Prospect af Malmanger Prestegaard (København: Reitzel, 1867), pp. 68–69.

26 Sven Henric Walcke, Minnes-Bok uti Danskonsten (Nyköping: Carl Hasselrot, 1782), p. 12.

27 Taubert, Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister, p. 617.

28 Email from Tilden Russell, February 2016.

29 Email from Petri Hoppu, November 2016.

30 Sven H. Walcke, Toure-Bog af Engelsk- og Contra-Dandse for mine Eleve (Bergen: Hans Kongel. Majestæts priviligerede Bogtrykkerie, 1802), [no page numbers].

31 Sven H. Walcke, Dansebok. (1804), Mus.ms. 295, National Library of Norway, Oslo, pp. 77–80.

32 Mus.ms. 299, Sven H. Walcke, ‘Musik og Tuure Bog medelt[?] inhentede Lærdomme for mine Elever udi Dands og afgivet av mig S. H. Walcke Aaret 1816’ (1816), p. 45, National Library of Norway, Oslo.

33 For a transcription, see Svarstad, ‘Aqquratesse i Alt af Dands og Triin og Opførsel’, pp. 196–97.

34 J. J. Martinet, Begyndelsesgrunde i Dandsekonsten: Bestemt til Nyttig Selvøvelse, og for de Forældre som ej Holde Dandsemester til deres Børn, trans. by C. H. Lund (Kiøbenhavn: L. Reistrups Forlag, 1801), 22.

35 Martinet, pp. 21–26.

36 Ibid., pp. 31–32.

37 Pierre Jean Laurent, ‘Weiledning ved Underviisning i Menuetten tilligemed en kort Underretning om dens Oprindelse og Fremgang blandt forskjellige Nationer’, Acc. 2012/28, Håndskriftsamlingen, Royal Danish Library.

38 Laurent wrote in it that he had been receiving his pension for about 30 years, since 1786.

39 See, for example Henning Urup, Dans i Danmark: Danseformerne ca. 1600 til 1950 (Københavns Universitet: Museum Tusculanums Forlag, 2007).

40 The book shows clear signs of several pages having been cut out. It may therefore be possible that an eventual instruction of the minuet has been taken out, perhaps for the purpose of teaching the minuet. For a transcription, see Elizabeth Svarstad, ‘Transkripsjon av og kommentar til Pierre Jean Laurents dansebok’ in Folkedansforskning i Norden, 40 (2017), 14–19.

41 Jørgen Gad Lund, Terpsichore, eller: En Veiledning for mine Dandselærlinger, til at beholde de Trin og Toure i Hukommelsen, som de hos mig have gjennemgaaet (Mariboe: C.E. Schultz, 1823).

42 Dancing master Poul Kaastrup published Lund’s book in Thisted in Denmark in 1825 and dancing master Espen Hall later published the same book in three editions in Norway from 1831 to 1837.

43 Janny Isachsen, Lommebog for Dansende (Kristiania: Cammermeyer, 1886), pp. 30–37.