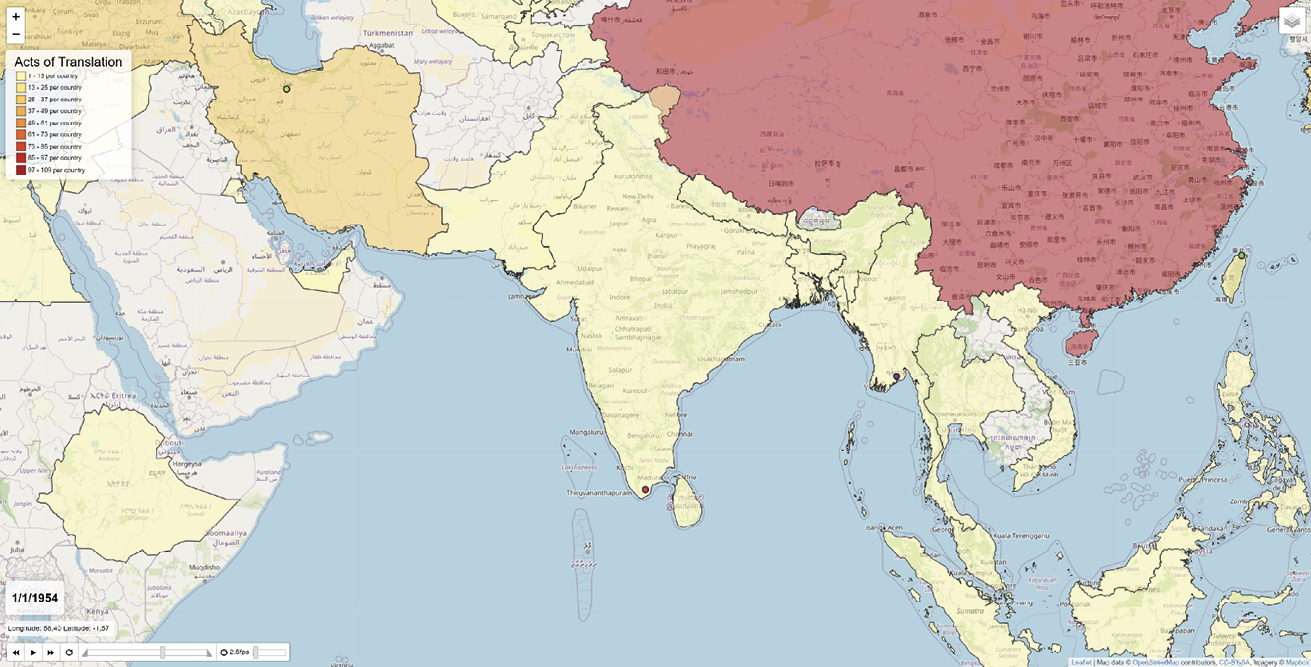

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

1. Jane, Come with Me to India: The Narrative Transformation of Janeeyreness in the Indian Reception of Jane Eyre

© 2023 Ulrich Timme Kragh & Abhishek Jain, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.04

Jane Eyre on India: The Indian Motif as a Suspense Juncture

‘I want you to give up German and learn Hindostanee.’2 These words are spoken by Mr St John Rivers to Jane Eyre as he tries to convince her to become closely involved in his linguistic and theological preparations for leaving England to go on a Christian mission. The quoted passage is one of the several commentaries on India scattered throughout the novel, which, taken together, create a composite of an Indian motif, the full significance of which has hitherto remained unexplored. Its paucity in Brontëan studies detracts not only from understanding the complexities of the literary characters in Jane Eyre but more importantly from the exploration at hand of the South Asian reception of the novel across the configurations of the oeuvre of the Indian adaptations and translations. In what follows, an elucidation of the Indian motif will begin by identifying the Indian elements in the novel and be expanded upon by a theoretical appraisal of its narrative function that relies on indigenous Indian narratological theory.

As it turns out, Mr Rivers is hoping to marry Jane so that she may accompany him on his oriental journey as a missionary helpmeet and fellow labourer, a conductress of Indian schools, and a helper amongst Indian women.3 Dutiful as she is, Jane consents to studying Hindustani, an archaic linguistic term referring to modern Hindi, Urdu, and to some extent Indo-Persian spoken throughout much of northern India.4 Already fluent in French, the British-born Jane abandons learning German and pursues the study of Hindustani for two months. One passage describes how she sits ‘poring over the crabbed characters and flourishing tropes of an Indian scribe’.5

Soon thereafter, Mr Rivers purchases a one-way ticket on an East Indiaman ship, bidding farewell to his native England with a foreboding sense of never returning:

‘And I shall see it again,’ he said aloud, ‘in dreams when I sleep by the Ganges: and again in a more remote hour — when another slumber overcomes me — on the shore of a darker stream!’6

Before leaving for Calcutta,7 he finally proposes to Jane, saying ‘Jane, come with me to India’,8 and although she initially embraces the idea of joining him on this Christian quest, in the end she cannot give her heart to Mr Rivers. The marriage never comes to be and Jane does not set out to ‘toil under eastern suns, in Asian deserts’.9 Instead, she leaves his home in the English countryside and, in a dramatic turn of events, goes back to her true love, the male protagonist Mr Edward Rochester, whom she finally marries in the book’s closing chapter.

Indubitably, the Indian motif is by no means central to the novel in its first twenty-six chapters, which narrate Jane’s childhood and her life as a young adult serving as a governess at Mr Rochester’s estate, Thornfield Hall. Yet, as the plot unfolds throughout the remaining twelve chapters, India gradually emerges as a place of particular imagination and it is possible to discern its significance at a crucial turn of events, marking a watershed in the narrative. Having, in Chapter 27, discovered the secret life of Mr Rochester and broken off their marriage engagement, Jane wanders away into a new circumstance in her haphazard encounter with the three siblings of the Rivers family throughout Chapters 28 to 33. It is in this new setting of separation from Mr Rochester that India — in Chapter 34 — enters the story with full force.

In the last part of the book, India initially appears in Chapter 32, where the eastern land is brought into focus by Jane in a conversation that she is having with Mr Rivers, as he prepares to set out for the far reaches of the British Empire. Jane has drawn a portrait of Miss Oliver and she offers to make a similar one for Mr Rivers to take on his voyage:

Would it comfort, or would it wound you to have a similar painting? Tell me that. When you are at Madagascar, or at the Cape, or in India, would it be a consolation to have that memento in your possession?10

Here, Jane for the first time mentions India as the ultimate destination of Mr Rivers’s voyage, alongside the Cape of South Africa and the island of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean as intermediary ports of call along the traditional shipping route to the Indian subcontinent prior to the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, twenty-two years after the publication of Brontë’s book. Thus, unwitting of its looming momentousness, Jane for the first time broaches the topic of India.

The Indian theme then returns emphatically in Chapter 34, this time raised by Mr Rivers appertaining to Jane. As he, for priestly reasons, beseeches Jane to accompany him on the missionary journey as his wife, India becomes concretised as the fundamental object of a life-altering decision for Jane. The subcontinent crystallises as a potential destination of escape from the amorous tragedy that she earlier underwent with Mr Rochester. Consequently, Asia becomes a realm in which she might live out a utopian form of religious self-sacrifice unto death. Torn, she reflects on Mr St John Rivers’s proposal:

Of course (as St. John once said) I must seek another interest in life to replace the one lost: is not the occupation he now offers me truly the most glorious man can adopt or God assign? Is it not, by its noble cares and sublime results, the one best calculated to fill the void left by uptorn affections and demolished hopes? I believe I must say, Yes — and yet I shudder. Alas! If I join St. John, I abandon half myself: if I go to India, I go to premature death. And how will the interval between leaving England for India, and India for the grave, be filled? Oh, I know well! That, too, is very clear to my vision. By straining to satisfy St. John till my sinews ache, I shall satisfy him — to the finest central point and farthest outward circle of his expectations. If I do go with him — if I do make the sacrifice he urges, I will make it absolutely: I will throw all on the altar — heart, vitals, the entire victim. He will never love me; but he shall approve me; I will show him energies he has not yet seen, resources he has never suspected. Yes, I can work as hard as he can, and with as little grudging.11

India is no longer merely an outer place in the story. By becoming a trope forming a religious-idealist alternative to Jane’s former English life of servitude, it is an occasion for the female protagonist gradually to fulfil an inner realisation of a newfound power and independence, which in the end permits the plot’s complication to unravel.

Ultimately, in Chapter 35, Jane rejects Mr Rivers’s marriage proposal and abandons the prospect of going to India. At this moment of inner strength gushing forth, she intuitively feels that her true love, Mr Rochester, is calling her from afar, and in Chapter 37 she then travels back to Thornfield Hall, while Mr Rivers sets out for India alone. Thereupon, the Indian motif recedes into the background, only to return at the very end of the novel. In the book’s closing paragraphs, Jane adopts a changed narrative perspective of reminiscing from the future to recount what later became of Mr Rivers in India, which underscores the Indian theme as a figuration of surrender and personal realisation:

As to St. John Rivers, he left England: he went to India. He entered on the path he had marked for himself; he pursues it still. A more resolute, indefatigable pioneer never wrought amidst rocks and dangers. Firm, faithful, and devoted, full of energy, and zeal, and truth, he labours for his race; he clears their painful way to improvement; he hews down like a giant the prejudices of creed and caste that encumber it. He may be stern; he may be exacting; he may be ambitious yet; but his is the sternness of the warrior Greatheart, who guards his pilgrim convoy from the onslaught of Apollyon.[12] His is the exaction of the apostle, who speaks but for Christ, when he says — ‘Whosoever will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross and follow me.’ His is the ambition of the high master-spirit, which aims to fill a place in the first rank of those who are redeemed from the earth — who stand without fault before the throne of God, who share the last mighty victories of the Lamb,[13] who are called, and chosen, and faithful.

St. John is unmarried: he never will marry now. Himself has hitherto sufficed to the toil, and the toil draws near its close: his glorious sun hastens to its setting. The last letter I received from him drew from my eyes human tears, and yet filled my heart with divine joy: he anticipated his sure reward, his incorruptible crown. I know that a stranger’s hand will write to me next, to say that the good and faithful servant has been called at length into the joy of his Lord. And why weep for this? No fear of death will darken St. John’s last hour: his mind will be unclouded, his heart will be undaunted, his hope will be sure, his faith steadfast. His own words are a pledge of this —

‘My Master,’ he says, ‘has forewarned me. Daily He announces more distinctly, — ‘Surely I come quickly!’ and hourly I more eagerly respond, — ‘Amen; even so come, Lord Jesus!’14

It is remarkable that such should be the very last words of the novel. Ending the whole book with a Christian pronouncement of devoted service to God by the lone English missionary in India who ‘labours for his race, … clears their painful way to improvement [and] … hews down like a giant the prejudices of creed and caste that encumber it’ is a token of the unexpected prominence of India in the book’s narrative.

Literary merits aside, Brontë’s construction of India is by no means straightforward and warrants cautious scrutiny. On the one hand, from a contemporary postcolonial perspective, Brontë’s India could well be seen as an entirely orientalist topos of the heathen presented as being in dire need of moral improvement and social progress.15 Targeted for Christian proselytisation, this Indian Other is to be stripped of what is perceived as its baseless religious beliefs and backward social system.16

On the other hand, from a literary historicist perspective, Brontë’s colonial India could be seen as indispensable to the intercultural poetics at play in the novel’s literary portrayal of England in the mid-nineteenth century. The author is evidently familiar with several Indian goods and sporadically employs allusions to Indian mercantile imports, such as rubber, fabric, and ink, embedded in the daily language used by the novel’s characters.17 Brontë’s literary allusions to India represent an England saturated by the economic and cultural infusions flowing from its colonial empire. They concord with the historical epoch, when the British colonial trade with India was booming and the Indian languages, religions, and literature had begun to impose a cultural allure on the British mindset, pictured in the story by Jane’s foray into her brief study of Hindustani. In fact, the very first English translations from the Indian classical Sanskrit literature had already been published by Sir Charles Wilkins in the 1780s, half a century before Brontë wrote Jane Eyre,18 and the first British chair of Sanskrit Studies had been established at Oxford University in 1833 — a decade and a half prior to Brontë’s book — by an endowment from Lt. Colonel Joseph Boden, who had served in colonial India. By the 1840s, when Brontë wrote her novel, contemporaneous English literature was thick with portrayals of India and Indian elements, as encountered in the Indian-born English author Thackeray’s novel Vanity Fair (1848).

It is unknown whether Charlotte Brontë possessed a deeper familiarity with India and its culture. India in her novel is primarily an important place for Christian mission, as reflected in the apparent reason for Jane’s study of Hindustani.19 This Christian depiction of India aligns with some of the early efforts at culturally translating India to the British audience, which were presented as being driven by a religious calling, seen, for instance, in Lt. Colonel Boden’s endowment to Oxford University for the Sanskrit chair being explicitly intended to serve ‘the conversion of the Natives of India to the Christian Religion, by disseminating a knowledge of the Sacred Scriptures amongst them more effectually than all other means whatsoever’.20

While Brontë’s portrayal of India certainly is culturally one-sided and religiously hegemonic, there nevertheless is a more profound facet to the Indian motif pertaining to its key function within the novel’s plot. The nineteen-year-old Jane’s fateful encounter with Mr Rivers, her two-month endeavour to study Hindustani under his tutelage, and finally her expressed yet ultimately unrealised wish to accompany him to India as a fellow missionary cannot be reduced to mere expressions of a fervent Christian calling intrinsic to Jane’s character. Rather, these elements in the storyline, along with the reappearance of Mr Rivers and his Indian mission at the very end of the book, suggest that the novel’s Indian motif holds a deeper significance aimed at expressing how Jane gradually opens up her young mind to the broader world and the possibilities it holds for her. It offers a way of fulfilling her inner restlessness and deeply felt need for seeing the world that she had already entertained while residing as a governess at Thornfield Hall:

… I longed for a power of vision which might overpass that limit; which might reach the busy world, towns, regions full of life I had heard of but never seen.21

Consequently, the narrative function of the Indian motif serves as a transformative condition of Jane’s character that subsequently triggers in her the telepathic voice of Mr Rochester, which ultimately induces her to return and marry him.

Such plot transitions are commonly interpreted in English literary criticism through the traditional narrative theory of Aristotelian thought. This foundational model espouses plot transitions as driven exclusively by agentive characters and consequently places the action of the plot at its centre. For this reason, it is necessary to consider a theoretical model that would shift the focus from the action to the dramatic purposes of non-agentive motifs. This methodological shift would allow for comprehending Brontë’s narrative strategy of letting an outer condition — the possibility of participating in an Indian mission, a non-agentive element — alter Jane’s character. By employing a classical Indian model of narratology derived from the dramaturgy of Bharata Muni, a theory of the dramatic purposes of non-agentive motifs may be developed, and applied to Jane Eyre and its non-action-based Indian elements.

In the standard Aristotelian model of narrative, a mythos (μῦθος plot) is an imitation of a praxis (πρᾶξις action) that may be said to consist of five parts: (1) the exposition, (2) the rising action, (3) the climax, (4) the falling action, and (5) the dénouement (unravelling) accompanied by revelation.22 In the final chapters of Jane Eyre, the climax of the plot can be identified as Mr Rochester’s attempt to marry Jane, which fails when it is brought to light that he still is bound by an earlier marriage to the mentally ill Bertha Mason from the West Indies. The falling action follows with Jane’s hurried departure from Thornfield Hall and her being taken in by the Rivers family, far away from Mr Rochester. The dénouement is then put in motion with the telepathic voice calling Jane back to Mr Rochester, whereby the plot’s agon (αγων complication) conclusively unravels when she returns and discovers that Thornfield Hall has burned down and Bertha has perished, while the now blind and widowed Mr Rochester has survived, which sets Jane free to marry him.

While these narratological constituents of Aristotelian plot analysis account for the characters’ actions, they do not allow a narrative function to be ascribed to the Indian motif, which is not driven by the dramatic action. In Aristotle’s model, the motif can be understood only as a minor intensifying context within the falling action, for which there is no Greek term. This limitation originates from the Aristotelian emphasis on the plot being exclusively the dramatic action, which can only be performed by the characters in the drama. Given that the utopian trope of India is not a character, the Aristotelian model cannot ascribe any action to the trope. Consequently, the Indian trope falls outside the explanatory scope of standard narratology. In spite of its evident transformative influence on the main storyline, the Indian motif becomes diminished in a traditional narratological analysis when it is demoted to an entirely passive yet suspenseful outer circumstance in the drama.

The ardent reader of Jane Eyre, therefore, might wish to revisit the Indian motif when called by a different classicist voice, that of the dramatologist Bharata Muni resonating from ancient India. For when the storyline of Jane Eyre is viewed through the alternative narratological lens of the Bharatic tradition of the Nāṭyaśāstra (A Treatise on Drama) of Indian dramaturgy, whose theoretical focus lies primarily on the plot’s sandhi (संधि junctures) rather than on its imitation of a praxis (action), it all of a sudden becomes possible to uncover the deeper significance of the Indian ingredients within the plot.23

In the Bharatic narratology, the itivṛtta (इतिवृत्त plot) is divided into five broad action-oriented avasthā (अवस्था stages) that are tied together by five sandhi (junctures). The part of the story between Jane’s departure from Mr Rochester until her return to him can, in the Bharatic schema, be identified as the penultimate juncture known as vimarśa (विमर्श suspense), which is a crisis characterised by deceit, anger, or an obstacle that causes hesitation and doubt in the protagonist.24 It is within this transitional phase of the plot, the vimarśasandhi (विमर्शसंधि suspense juncture), that Brontë introduces the Indian motif.

The suspense juncture generally serves to tie together the plot’s middle stage with its final resolution. In the case of Jane Eyre, the suspense juncture contains a longer subplot of its own, namely the story of Jane’s stay with the Rivers siblings and in particular her platonic relationship with Mr Rivers. In the Bharatic narratology, such a subplot is called a patākā (पताका pennant), since it is a story within the story, which tapers out just like the triangular shape of a pennant flag. The pennant type of subplot is defined as an episode that is integral to the main plot, given that it helps to drive the main plot forward. It is marked by having its own distinct artha (अर्थ objective), which differs from the overall objective of the main plot.25

While the pennant subplot encompasses Jane’s encounter and relationship with Mr Rivers, its artha (objective) is the Indian motif, i.e., Mr Rivers’s proposition for Jane to go with him to India. This artha of the subplot represents an alternative to the artha of the main plot, which is Jane’s marriage to Mr Rochester. In relation to the larger plot structure, the subplot’s Indian motif correspondingly signifies an opening up within Jane towards the possibility of a new objective, a different life elsewhere. Although Jane decides not to go to India, it is the maturation of her character brought about by the alternative of the Indian motif that closes the suspense juncture in the plot and propels Jane into the final plot stage, namely the so-called phalayogāvasthā (फलयोगावस्था stage of reaching the result), which is represented by her return and marriage to Mr Rochester.

In the Bharatic narrative model, the phalayogāvasthā ends with another sandhi (juncture) of its own, the fifth juncture called nirvahaṇa (निर्वहण closure). The nirvahaṇasandhi (निर्वहणसंधि closure juncture) is, in the classical Bharatic schema, said to have fourteen possible forms.26 In the case of Jane Eyre, two of these forms of closure can be identified, namely bhāṣaṇa (भाषण a closing speech) and grathana (ग्रथन a tying together of the action). The bhāṣaṇa is the above-cited narration found in the novel’s three final paragraphs that recount what later became of Mr Rivers. The grathana is the re-emergence of the topos of India in the antepenultimate paragraph of the novel, echoing the Indian motif of the suspense juncture. The fact that Brontë returns to the Indian motif at this concluding point creates a narrative bridge between the living vision of Jane’s India and the dying reality of Mr Rivers’s India, solidifying the author’s overarching resolution to make India a focal point of the plot. Correspondingly, the link between the objective of the vimarśasandhi (suspense juncture) and the two narrative expressions of the nirvahaṇasandhi (closure juncture) reveals the centrality of the Indian motif for the entire novel.

India on Jane Eyre: The Narrative Transformations of the Indian Motif

In the Aristotelian theory of poetics, a turning point defines the moment in a play when the dramatic action begins to unravel, in Greek referred to as peripeteia (περιπέτεια reversal). ‘Jane, come with me to India’ engenders such a peripeteia by initiating the gradual return of Jane to Mr Rochester while simultaneously precluding Jane from ever arriving on Indian soil.27

In a paradoxical turn of events, Jane nevertheless has been transposed to India, and not by Charlotte Brontë, but by the Indians themselves. Jane first touched Indian soil in 1914 dressed in native sāṛī (साडी saree) and speaking Bengali as she stepped onto the literary scene in the Indian novel Sarlā. In the ensuing popular reception of Jane Eyre in India, Jane has ever since lived multifarious lives through numerous adaptations and translations of Brontë’s novel into disparate regional Indian languages. Nonetheless, in the Indian academic reception since the 1980s, Jane Eyre has forever remained a novel to be read in English, never contemplated with regard to its Indian motif, and invariably confined to the discursive English realm of modern social and literary theory.

As will be argued below, highlighting these different linguistic pathways through a chronological survey of the literary and cinematographic adaptations of the novel, juxtaposed with Jane Eyre’s academic reception and circulation in India, uncovers a state of irony in the significance of the Indian motif articulated with a Bharatic narratological awareness. For when the English novel is translocated specifically to India, the Indian motif loses its force and is replaced by other literary devices, signalling a narrative transformation.

In 1914, the Christian schoolteacher Nirmmalā Bālā Soma (নির্ম্মলা বালা সোম ) published the Bengali novel Sarlā (সরলা Sarlā) in 188 pages.28 It was self-published by the author and printed by N. Mukherjee at Gupta, Mukherjee & Co.’s Press in Calcutta. Soma had been educated at the renowned Bethune women’s college in Kolkata and went on to obtain a master’s degree in English from the University of Calcutta. The novel, written in Bangla language, i.e., Bengali, is a literary adaptation of Jane Eyre which recasts the story into the Bengal region of colonial India. The book consists of thirty chapters, most of which are just four to five pages in length. With a storyline and prose texture closely resembling Brontë’s Jane Eyre, it tells the story of the Indian female protagonist Ms. Sarlā, a faithful rendering of Jane, from her upbringing as an orphan into her life as a young adult. Sarlā works as a governess for Mr Śacīndrakumār Bandyopādhyāy with whom she gradually becomes romantically involved. Having discovered that he is bound by an existing marriage to the insane wife Unnādinī, Sarlā runs away and is accepted into the Christian family of Mr Śarat Bābu and his two sisters. After Sarlā, with Mr Śarat’s help, has obtained a large inheritance from a deceased uncle, Mr Śarat proposes to her, asking her to join him on travels to do Christian work. She rejects the proposal and instead returns to marry Mr Bandyopādhyāy, who, after a fateful fire, is now widowed and blind. Ten years later, Mr Śarat passes away, having lived an austere, solitary existence devoted to God. Sarlā briefly praises him as a most heroic and devout Christian, whose desires she never fulfilled.

In a short epilogue on the last page of the book, Soma remarks that she does not claim originality for her novel and does not consider it a translation. Without mentioning Jane Eyre explicitly, the author notes that the story of Sarlā is based on an unnamed English work, deviating from the original in many places. For instance, the novel does not contain the colonial dimension of Englishmen traveling to their Indian colony, but it retains the religious aspect of Christian mission in India. Being quite close to Brontë’s novel yet altered in certain ways, Soma’s literary work can best be described as an anurūpaṇ (अनुरूपण adaptation) of Jane Eyre. An adaptation, whether literary or cinematographic, is characterised by the reproduction of a prototypical story in a recognizable fashion while adding certain new elements of its own. Soma’s novel never became widespread in India. The writer was not well-known and the book was published independently in just a small number of copies without ever being reprinted. Sarlā remains the first Indian adaptation of Jane Eyre and also the version that stands the closest to Brontë’s original.

Three decades after Soma’s literary adaptation, the 1950s mark the period when Jane Eyre was introduced to a broader Indian audience. Just a few years after India had gained independence from British colonial rule in 1947, which took place precisely a century after Brontë’s publication of Jane Eyre in 1847, the first Indian cinematographic adaptation appeared in 1952, followed the next year by the first abridged translation into an Indian language, namely the Tamil translation of 1953. The first cinematographic adaptation was the Hindi-Urdu Bollywood film Saṅgdil (संगदिल سنگدل Stone-Hearted),29 bearing the English subtitle An Emotion Play of Classic Dimensions. Produced and directed by Ār. Sī. Talvār (b. 1910), it was shot at the Eastern Studios and Prakash Studios in Mumbai.30 The film stars the actress Mumtāz Jahāṃ Begham Dehlavī (1933–1969, stage name Madhubālā) in the female lead role of Kamlā and Muhammad Yūsuf Khān (b. 1922, stage name Dilīp Kumār) in the male lead role of Śaṅkar.

Although Saṅgdil displays many elements detectable from the original novel, in his screenplay Rāmānand Sāgar (1917–2005)31 takes many liberties in constructing the female and male protagonists. The major difference is that while Jane and Mr Rochester first become acquainted as adults in Brontë’s narrative, the film portrays Kamlā and Śaṅkar as living in the same household since early childhood. Śaṅkar’s father adopts Kamlā after the death of her father, a close friend of his, and secretly usurps Kamlā’s inheritance, leaving her to the cruelty of his wife, who treats her like a servant. After the death of Śaṅkar’s father, the stepmother sends Kamlā to an orphanage. On the way to the orphanage, Kamlā manages to escape and is adopted by a group of Hindu pujārīn (पुजारीन priestesses) living in a local Śiva temple, where she grows up. Later in the film, the childhood friends Kamlā and Śaṅkar are gradually reunited as adults, when Kamlā visits Śaṅkar’s new estate in order to carry out religious worship as a devadāsī (देवदासी) performer of Hindu sacred dance.32

A series of events then unfolds, which is highly reminiscent of the second half of Brontë’s novel with certain alterations. When Kamlā leaves Śaṅkar on their wedding day as she discovers that he already is married to the insane woman Śīlā, she returns to the temple where she grew up in order to pursue a wholly celibate life as a Hindu priestess. There is, accordingly, no character in the film matching Mr Rivers and consequently Kamlā is never exposed to the element of having to learn a foreign language nor of having to go abroad as a missionary. Instead, while Kamlā places her personal belongings one by one into a sacrificial fire during a purification ritual aimed at fully devoting herself to the new religious life of a renunciate, Śaṅkar’s estate is set ablaze by Śīlā and burns to the ground, with Śīlā being consumed by the fire. When, during the ritual, Kamlā is asked by the high priestess whether she still has an attachment to anyone in the world, she internally hears Śaṅkar’s voice calling her name and realises her strong bond to him. Kamlā interrupts the ritual and returns to her beloved Śaṅkar, who has by then become blind and widowed.

Saṅgdil, which was an Indian box office hit, can certainly be considered an adaptation of Jane Eyre, in that it thoroughly rewrites the prototypical story of the English novel while retaining some familiar elements. The film is, though, not much further removed from the original than, for instance, the 1934 Hollywood movie adaptation of Jane Eyre directed by Christy Cabanne, starring Virginia Bruce and Colin Clive, which likewise makes many omissions and changes of its own to the story.33 Saṅgdil may thus be said to belong to a film genre similar to that of its literary ancestor, with the proviso that the change of medium from text to screen naturally involves transformations that transcend the strictly narrative aspect of the literary genre.34 This is particularly evident in the film’s inclusion of several song and dance segments, as is characteristic of most Bollywood films, such as the celebrated song Dhartī se dūr gore bādloṃ ke pār (धरती से दूर गोरे बादलों के पार Far from the Earth, Across the White Clouds).

Some of the creative modifications of narrative found in Saṅgdil were perhaps culturally necessitated when placing the story in an Indian setting inhabited by Indian characters. One such requisite is Kamlā’s upbringing as a temple priestess, because this is a profession that allows her as an adult to enter Śaṅkar’s estate. It would have been improbable for Kamlā to come to the estate as a governess, since Indian unmarried women normally did not hold such positions in the nineteenth century.

Other changes in the storyline may have been motivated by literary concerns aimed at opening up the story to the Indian audience, which may have served to draw the film into intertextual connections with distinctively Indian literary genres. In particular, the reunion of Kamlā and Śaṅkar in the middle of the film made possible by their childhood friendship echoes a beloved Indian literary device of abhijñāna (अभिज्ञान recognition). Famous across India from the Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa’s (4th-5th centuries) classic drama Abhijñānaśākuntala (The Recognition of Śakuntalā), this literary theme is a transformation of the lovers’ estrangement into their mutual recall and subsequent conjugal union. The film innovatively draws on Kālidāsa’s story to infuse Jane Eyre with a new potent reason for the love to unfold.

Saṅgdil is the Indian adaptation that portrays its female protagonist in the most powerful way, because it entirely leaves out any Mr Rivers character and instead has Kamlā seek an independent religious life as a Hindu renunciate priestess. Kamlā’s decision to return to Śaṅkar is not based on having been offered an alternative marriage to another man. It instead flows from her inner awakening that she still has an emotional connection to Śaṅkar, which she wishes to confront and eventually pursue. In this version, there is no manifest colonial aspect and the story’s religious dimension has been transformed from Christian to Hindu, and transposed onto Kamlā.

In 1959, Jane emerged in yet another Indian adaptive guise. The lauded South Indian writer Nīḷā Dēvi (ನೀಳಾ ದೇವಿ, b. 1932) from Bengaluru, Karnataka, published the Kannada novel Bēḍi Bandavaḷu (ಬೇಡಿ ಬಂದವಳು The Woman Who Came out of Need) in 240 pages. This was the second Indian book adaptation of Jane Eyre. The book was published by Mōhana Prakāśana in Mysuru.35 Analogous to the earlier Bengali novel by Soma, Dēvi recasts Brontë’s story into an Indian setting, keeping the plot close to the storyline of the English novel. The female protagonist Indu takes up a position as a private teacher for a young girl at the estate of Mr Prahlāda. The story then unfolds along the lines of the English novel, although all of the dialogue has been rewritten and Indu is a softer, less individualistic character than her British counterpart. Having left Mr Prahlāda’s estate upon the discovery of a mad wife in the attic, Indu is taken in to the home of Mr Nārāyaṇa and his two sisters. He is a young Brahmin, who works at a Hindu temple and is involved in distributing herbal medicine to the local rural community. When offered a job at a textile mill in faraway Ahmedabad in the Indian state of Gujarat, he proposes to Indu and asks her to accompany him. She rejects his proposal. At this moment, she remembers Mr Prahlāda and is overcome with longing. Soon thereafter, she telepathically hears Prahlāda crying out her name as he is blinded in a fire that burns down his estate, whereupon she returns and marries him. Mr Nārāyaṇa does not reappear in the story.

While the Kannada novel resembles Soma’s earlier Bengali work in the manner in which it adapts the English novel into an Indian setting, the Kannada version entirely lacks the Christian dimension, which remains prominent in the Bengali adaptation. The novel is the first Indian adaptation to replace, or at least substantially downplay, the religious mood of Jane Eyre in favour of a secular choice. Mr Nārāyaṇa proposes marriage to Indu, not for the sake of religious mission, which traditionally is a relatively unimportant aspect of Hinduism, but instead with the secular prospect of moving for his new job at a textile mill. The novel presents Indu as finding independence through her new position as a schoolteacher, and by the financial security that she obtains from getting an inheritance, without suggesting any inner transformation taking place within Indu that could explain her decision to return to Mr Prahlāda. In this sense, Indu’s character is slightly weakened in the Kannada novel.

In 1968, a decade after the publication of Dēvi’s Bēḍi Bandavaḷu, the novel was picked up and filmed under the same title Bēḍi Bandavaḷu (ಬೇಡಿ ಬಂದವಳು The Woman Who Came out of Need) by the South Indian director Si. Śrīnivāsan.36 The Kannada language film features the actress Candrakalā (1950–1999) as Indu and the actor Kalyāṇ Kumār (1928–1999) as Prahlāda. The filmization entails several minor changes to the story of the Kannada novel. A new element is the interspersed comic relief provided in the film by the supporting character Kr̥ṣṇa, a male servant at the estate, played by the South Indian comedian Baṅgle Śāma Rāv Dvārakānāth (stage name Dvārakīś, b. 1942). Another narrative difference from the Kannada novel is that Indu in the film serves as the governess not for one but for four girls at the estate. The film deals only briefly with Indu’s stay at the Nārāyaṇa family and Mr Nārāyaṇa does not propose marriage to Indu. Instead, he asks her about her general intentions to marry, which causes her to remember Prahlāda. Finally, the ending of the film differs slightly from the novel. When Indu discovers that Prahlāda has turned blind, she wishes to destroy her own eyesight with a lit candle. She is prevented from doing so by a doctor who enters the scene just in time to assure her that Prahlāda’s sight can be restored with surgery at a hospital in Bengaluru. The film ends with Prahlāda and Indu driving away for Bengaluru in the back of a jeep. In terms of filmic adaptative transformations, like Saṅgdil, the Kannada film includes several genre-altering song and dance routines not found in the Kannada novel, thereby imbuing the film with an added feature of the musical genre. Some of these are the song Ēḷu svaravu sēri (ಏಳು ಸ್ವರವು ಸೇರಿ Uniting the Seven Musical Notes) performed by the playback singer Pi. Suśīla (b. 1935) and the amorous tune Nīrinalli aleya uṅgura (ನೀರಿನಲ್ಲಿ ಅಲೆಯ ಉಂಗುರ Rings of Waves in the Water) performed by Suśīla and Pi. Bi. Śrīnivās (1930–2013).

Character-wise, the filmization of Bēḍi Bandavaḷu weakens Indu’s role even further. It omits both Indu’s employment as a schoolteacher and Mr Nārāyaṇa’s marriage proposal, and as a result it does not give Indu any concrete choice of another way to fulfilment. Indu finds financial independence through an inheritance, but is uncertain about what to do with her life. Her hesitancy builds up in the scene when Mr Nārāyaṇa inquires about her general plans to marry, which causes her to remember and long for Mr Prahlāda. Indu undergoes no emotional transformation at all and returns to Mr Prahlāda when, in her solitude, she realises that her heart belongs to him.

In the following year, 1969, after the commercial success of Bēḍi Bandavaḷu, a remake of the film was produced in the Tamil language entitled Cānti Nilaiyam (சாந்தி நிலையம் A Peaceful Home) directed by Ji. Es. Maṇi.37 Remarkably, it is the only production of the five Indian cinematographic adaptations made in colour. The film script was rewritten for the Tamil version by the screenwriter Citrālayā Kōpu (pen name Caṭakōpaṉ, 1959–1990) in a decidedly more melodramatic form, leading the plot even further away from the storyline of Brontë’s Jane Eyre. The film features Vacuntarā Tēvi (stage name Kāñcaṉā, b. 1939) in the female lead as Mālati and Kaṇapati Cuppiramaṇiyaṉ Carmā (stage name Jemiṉi Kaṇēcaṉ, 1920–2005) in the male lead as Pācukar. Mālati is hired as a governess at Pācukar’s estate to look after four girls and one boy, all of whom are very rowdy and naughty. The developing romance between Pācukar and Mālati is haunted by Pācukar’s mad wife, Janakī, who lives hidden in the attic. Janakī’s role is, though, relatively minor, since the plot’s main conflict has been shifted to Pācukar and Janakī’s brother Pālu, correlative to Brontë’s character Richard Mason, the brother of Bertha Mason. Pālu aggressively pressures Pācukar to pay him money in order to settle an old family feud. Long ago, Pācukar’s father was wrongfully accused of murder and the legal settlement forced Pācukar to marry the insane Janakī. Pācukar’s family was required to pay compensation, part of which Pācukar still owes Pālu. When Pālu interrupts the wedding of Mālati and Pācukar, Mālati runs away on foot. Pācukar and Pālu have a dramatic fist fight, during which Janakī sets the house on fire. Mālati does not manage to get far, since one of the children runs after her and is hit by a car, whereupon Mālati rushes back to bring the child to a hospital. Janakī and her atrocious brother both perish in the fire, while Pācukar survives with his sight intact. The film ends happily with Pācukar, Mālati, and the children reunited at the family table in the still-standing and now peaceful house, which has survived the fire. The Tamil version tends to reduce the female protagonist Mālati’s emotional independence to the extent that she only briefly escapes on foot, whereupon she immediately has to return to help the injured child, leaving Mālati no time or possibility to reflect on seeking a new life of her own.

In the same year, 1969, that Ji. Es. Maṇi released the Tamil film Cānti Nilaiyam, the director Pi. Sāmbaśivarāvu created his debut film, the Telugu thriller Ardharātri (అర్ధరాత్రి Midnight).38 While not exactly an adaptation but rather an appropriation of Jane Eyre that is here recast in a completely different filmic genre of suspense, this cloak-and-dagger Telugu film contains the Jane-Eyre-inspired themes of an orphan woman and a mad wife, two characters already well-known to Indian cinemagoers from the earlier Jane Eyre adaptations.39 The film starts with a murder and a prison escape. It then tells the story of a young orphan woman, Saraḷa, a name reminiscent of the Bengali Sarlā character from the 1914 novel by Soma. The female lead is played by the actress Bhāratī Viṣṇuvardhan (b. 1948). After being expelled from her childhood home by a mean stepmother, Saraḷa is hit by a car and is taken into the household of the driver, a childless rich man named Śrīdhar, played by the actor Koṅgara Jaggayya (1926–2004). Saraḷa looks after Śrīdhar and a romance develops between them. Every midnight the house is haunted by a strange female presence emerging from a cottage in the garden, which terrifies the household’s male servants. Intrigued by the mysterious phenomenon, Saraḷa unsuccessfully tries to find out what lies behind the apparition. When Śrīdhar and Saraḷa are to be married, their wedding is interrupted by the antagonist Kēśav. He reveals that Śrīdhar already is married to the mad woman Rāṇi, Kēśav’s sister, who lives in the mysterious cottage in the garden. Onto the scene steps Śrīdhar’s long-lost father, who escaped from prison at the beginning of the film. The father discloses that Kēśav long ago murdered Rāṇi’s boyfriend, referring back to the murder shown at the beginning of the film. The fatal event drove Rāṇi insane. Kēśav managed to pin the murder on Śrīdhar’s father, which in turn forced his son, Śrīdhar, to marry the traumatised Rāṇi. In a dramatic twist of events, Kēśav sets the garden cottage on fire, in which he and Śrīdhar get into a fight to the death. Rāṇi saves Śrīdhar from being killed by Kēśav. Badly hurt in the fire, she dies from her wounds while lying on the ground calling out the name of her beloved murdered boyfriend. The police arrive and arrest Kēśav and his thuggish servant. The last scene shows Śrīdhar and Saraḷa as a married couple.

In 1972, a Telugu cinematographic remake of the 1969 Tamil film Cānti Nilaiyam was released under the similar title Śānti Nilayaṃ (శాంతి నిలయం, A Peaceful Home) directed by Si. Vaikuṇṭha Rāma Śarma.40 It features the actress Añjalīdēvi (1927–2014) in the role of Mālati.

The two Indian novels and five cinematographic renditions, starting with the Bengali novel Sarlā in 1914 up to the Telugu film Śānti Nilayam in 1972, can all be characterised as widely differing from the English Jane Eyre in terms of their outer setting, culture, religion, and language, while sharing certain elements with Brontë’s storyline and the typological features of its characters. None of these works explicitly acknowledges its indebtedness to Jane Eyre and yet, in spite of all the narrative transformations introduced in the Indian books and films, a reader or viewer familiar with Brontë’s novel would undoubtedly be able to pinpoint the resemblances. In particular, the motifs of the orphan girl, the romantic relationship with the estate owner, his hidden mad wife, and the portentous fire are repeated points of similitude.

Their common denominator of relocating the story to an India inhabited by Indian characters creates a quaint sense of fictionalised displacement. The new native soil, however, is extrapolated not through cultural comparison but by a hybridised substitution of English manner and tongue with Indian demeanour and vernacular in a Western-inspired mise en scène. Through this narrative process of metonymic transposition, the sāṛī-clad acculturated Janes amplify the subsidiary Indian features of Brontë’s novel into their preponderant trait, nonetheless with one inadvertent consequence for the anticipated metamorphosis of Jane’s character. The full transference of the story to India causes the Indian motif in Brontë’s novel, with its specific function as a transformative transition of peripeteia in the plot’s dénouement, to be rendered mute. Depriving the Indian Janes — Sarlā, Kamlā, Indu, Mālati, and Saraḷa — of the opportunity to go on a Christian mission to India with the Mr Rivers characters circumscribes the story’s vimarśasandhi (suspense juncture) that in Brontë’s novel enabled Jane to realise her sovereign self. Facing this inherent dilemma, the authors of the Indian adaptations are forced to provide their Jane characters with alternatives for finding closure after the betrayal they suffer from the Mr Rochester personas — Bandyopādhyāy, Śaṅkar, Prahlāda, Pācukar, and Śrīdhar — which inevitably leads to the progressive weakening of Jane’s internal character.

Diminishing the Indian Janes inexorably brings the otherwise obscure figure of Bertha Mason to the fore as a catalyst for unravelling the plot. The desperation and madness of the wife in the attic becomes a prominent feature, especially in the 1969 Telugu thriller Ardharātri, wherein the female protagonist Saraḷa is portrayed as an extraordinarily passive individual unable to react even when learning that her suitor is already married. To resolve the plot’s consequent impasse, the mad Rāṇi is made to stop the villain brother from killing Śrīdhar by sacrificing herself in the flames. In this sense, Ardharātri could be regarded as the ultimate adaptation of Jane Eyre, since it is here that the mad Rāṇi’s suppressed rage and not Saraḷa’s dullness and indecisiveness becomes the actual dramatic device for the dénouement.

The character of the mad wife Bertha Mason with its gothic determinism has been a topic of enduring fascination for academic Brontë studies in South Asia. Remarkably, the discourse on madness in Indian scholarship focusses on Jane Eyre solely as a Victorian novel to be scrutinized in English, never beheld through the prism of the Indian adaptations and translations. In their discussion, South Asian scholars have relied primarily on the Western classics of feminist theory and postcolonial critique while entirely leaving out literary and cinematographic adaptations in Indian languages.41 Therefore, when India’s leading scholar on the Brontë sisters, Kalyani Ghosh,42 examines the figure of Bertha, she does so in terms of an argument largely drawn from the feminist analysis put forth earlier by the American literati Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar.43 Ghosh argues that Bertha is an archetypal figure of hunger, rebellion, and rage, who has been victimised and repressed under a patriarchal social order, highlighting a degree of affinity between Bertha and Jane as to their entrapment in their inner and outer imprisonments.44 In a similar vein, Ratna Nandi maintains that Bertha’s volcanic rage is a projection of Jane’s fiery nature, representing a forbidden female expression, the explosiveness of which symbolises a destructive end to the despotic rule of man.45

Already in 1957, the Indian-Canadian scholar Devendra P. Varma observed that Brontë’s idea of the hidden mad wife seems to have been borrowed from a comparable motif in Ann Radcliffe’s gothic novel A Sicilian Romance (1790).46 It needs to be remarked that the ubiquitous character of the mad wife in all seven adaptations speaks to the power of the ancient Indian trope of female madness present throughout centuries of classical Indian literature, with its prototype in Princess Ambā from the ancient Hindu epic Mahābhārata.47 This most famous scorned mad woman in the Indian literary tradition is the quintessential figure of female resistance to male repression and ultimate self-sacrifice on the altar of revenge. When the love and life of Princess Ambā have been ruined after a violent intervention by the male anti-hero Bhīṣma, Ambā wanders the earth in a state of madness and pursues extreme religious renunciation in search of vengeance. By committing religious suicide, she returns in a reincarnation as Śikhaṇḍin, becoming an instrument for the hero Arjuna to slay Bhīṣma on the epic battlefield of Kurukṣetra. In contrast, in the context of Indian Buddhist narratives, the thread of madness is a common literary device allowing female protagonists to escape from the clutches of unwanted arranged marriages and pursue alternative lifestyles as religious mendicants for the sake of enlightenment, exemplified by the female Buddhist saint Lakṣmī in the twelfth-century biography by Abhayadattaśrī. Feigning insanity, Princess Lakṣmī deters her suitor from marrying her and thereby avoids a marriage with an unvirtuous prince, who through his indulgence in hunting breaks the fundamental Buddhist ethic of non-violence.48

While the relocation of Jane Eyre to India in the literary and cinematographic adaptations may evoke such classic Indian literary portrayals of insanity, it at the same time eradicates the overt colonial implications of madness first pointed out by the Indian-American Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in her highly influential postcolonial critique of the English novel.49 Spivak views Brontë’s Bertha as involving the construction of a self-immolating colonial subject who had to kill herself for the glorification of the coloniser’s social mission, thereby allowing Jane to realise her role as ‘the feminist individualist heroine of British fiction’.50 She notes that the underlying imperialistic staging of Bertha’s role remains obscure unless the reader is familiar with the British colonialist history of legal manipulation surrounding the former Hindu practice of widow self-immolation.51 In 1829, eighteen years prior to the publication of Brontë’s Jane Eyre, following a long political campaign in both Britain and India, the British government in India banned widow self-immolation, which Spivak maintains was a law imposed primarily for the sake of the colonial government to mandate itself as the protector of the Indian people against themselves.52

Spivak’s postcolonial critique has been bolstered by the Bangladeshi feminist scholar Firdous Azim.53 Azim extends Spivak’s earlier appraisal by asserting that the rise of the entire Western genre of the novel served an outright imperialistic purpose aimed at silencing and excluding women as well as persons of colour. Her analysis of Jane Eyre is — like Spivak’s — centred on the figure of Bertha Mason as Jane’s antithesis, her binary Other, who in a colonialist sense embodies attributes of savagery, madness, and sexuality.54

In the adaptations, strikingly the Indian Bertha characters do not hail from the West Indies and their stories do not entail the same imperialist subtext as found in Brontë’s work. Hence, the postcolonial critiques of the English novel raised by Spivak and Azim cannot be transferred outright to these adaptations. Nevertheless, the psychological antithesis between Bertha and Jane remains present throughout all the adaptations, magnifying the image of the mad wives’ rage proportionately as the Jane characters diminish in independence and strength in the later Indian film adaptations.

An issue closely related to the theme of madness is Brontë’s use of literary imagery. In a sophisticated feminist deconstruction of Jane Eyre, the Indian scholar Sonia Sarvipour,55 relying on Elaine Showalter’s feminist poetics,56 argues that the abundant images of dark corridors, locked rooms, and barely contained fires are significant examples of a unique female literary style characterised by recurrent themes of imprisonment, hidden rooms, and fantasies of mobility.57 She contends that such tropes are suggestive of a thick mist of female repression, which enveloped the lives of Victorian women, and that Brontë’s language fundamentally is a masculine form of prose in spite of its frequent use of feminine figuration and imagery. Ultimately, Sarvipour defines this multivalence as a literary mode of unreadability or undecidability, which she argues lies at the very heart of feminist writing.

The diverse ways in which the Bertha character has been portrayed in the popular adaptations versus how she has been conceived of in the scholarly reception in India illustrates that there exists a dialectic tension between the adaptations within the popular reception and the scholarly critiques within the academic debate. The popular adaptations voice the narratives in Indian vernaculars and Indianize the characters, whereas every academic study limits the story to its English source text, discussing it primarily in the framework of Western discourse.58 The opposition between the popular and academic forms of reception is embedded in a particular politics of language and audience, whereby Indian scholars, writing for an educated English readership, are primarily in dialogue with research by non-Indian scholars, giving minimal cross-reference to the work by their Indian academic peers. They deliberate, acquiesce, or expostulate without heeding the prevailing adaptations and translations of Jane Eyre in the Indian regional languages.

The politics of language and audience can only be understood against the backdrop of the nature of the broader status of the English language, the circulation of English classics, and their presence in higher education in India. For to read a literary classic directly in English signals on the subcontinent a cosmopolitan standing, and accordingly every Indian city has a number of well-stocked bookstores specialising in English literature, such as the store chains Crossword Bookstore or Sapna Book House, each of which is sure to have a copy of Jane Eyre in its section of English classics. The considerable acclaim received today by the major works of nineteenth-century English literature imported to India is closely linked with the high social status and widespread use of the English language throughout South Asia in spite of, as well as because of, the language’s colonial history on the subcontinent. In short, English ‘is the “master language” of the urban nouveaux riches’.59 The English language functions governmentally and often practically as an unofficial lingua franca between the different speakers of the twenty-two Indian languages officially endorsed in the Indian Constitution, for which reason learning English and achieving cultivation in English literature are of economic and cultural importance both to the state and the individual.

As evidenced in the Indian system of education, an extraordinary seventeen percent of Indian children attend schools where English is the main medium of instruction, while the remaining pupils receive five to ten English language classes per week within the frame of a primary school education in Hindi (49%) or other Indian regional language (33%).60 English literature and its classics are indisputably valuable to Indians, although this statement must be read with the caveat in mind that India has a highly prolific production of Indian English literature involving its own English classics, to mention but a few, the writings by the Indian poets and novelists Mulk Raj Anand (1905–2004), R. K. Narayan (1906–2001), Raja Rao (1908–2006), A. Salman Rushdie (b. 1947), Vikram Seth (b. 1952), Amitav Ghosh (b. 1956), S. Arundhati Roy (b. 1961), and Kiran Desai (b. 1971). The British Victorian literature, to which Jane Eyre belongs, is without doubt just one among several forms of English literary classics in India.

The popularity of Jane Eyre as an English classic throughout India is demonstrated by its wide distribution and presence in school curricula. Aside from the many print and e-book English editions available on the continent from large multinational publishers, such as Penguin, HarperCollins, and Macmillan India, the novel has frequently been reprinted in English by a number of smaller domestic Indian publishers, including Atlantic Publishers and Distributors (New Delhi), Om Books (Hyderabad), Maple Press (Noida), Rupa Publications (New Delhi), Rama Brothers India (New Delhi), and Gyan Publishing House (New Delhi). Indian publishers have likewise brought out several abridged English versions of the novel, some of them illustrated, mainly intended for the children and student book market, e.g., those published by S. Chand Publishing (New Delhi) as part of their ‘Great Stories in Easy English’ series, Har-Anand Publications (New Delhi), and Om Kidz Books (Hyderabad) in their ‘Om Illustrated Classics’ series.

In the system of higher education, Jane Eyre appears frequently on the curricula of English departments at many Indian universities. The book is a standard component of the undergraduate course ‘Analysis of English Literature’, where it is read alongside Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations (1861), D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers (1913), and William Golding’s The Lord of the Flies (1954), albeit not always in its entirety and typically in the form of excerpts.61

In spite of the omnipresence of the novel in English throughout India and its primary importance to Indian academic discourse, it could be argued that the cinematographic adaptations in Indian vernaculars supersede the permeability of Jane Eyre across social strata, because an English-clad Jane stays perpetually aloof and exotic. While the English Jane Eyre is widespread, it is no match for the familiarity with the story effected by the box-office hits of the Indian film adaptations delivered in several major regional languages. Adaptation is thus the literary form that most eminently captures acculturation. Jane Eyre in India is accordingly not exclusively a literary classic in English or an Indian translation, but through its literary and cinematographic adaptations the Jane character has metamorphosed from a British governess to a polyglot South Asian maiden. The creative license exercised by the novelists and filmmakers to adjust and transform the story whilst retaining the recognizability of the original comprises the hallmark of these adaptations.

Jane Eyre in Anuvād: The Substance of Janeeyreness

Translation is, in a sense, the opposite of adaptation. While adaptation stands out through a difference to the original due to its distinctive feature of modifying the plot, the setting, or the medium, translation has conventionally been qualified by an expectation to reproduce the source text so adequately that the text itself becomes fully meaningful in the target language, whether it be an interlingual or intralingual rendering.62 This understanding of translation, which has been termed semantic equivalence, remains common to contemporary academic traditions across the West and India, despite the critique levelled against the idea in more recent Translation Studies.63

As will be argued, defining translation by equivalence, as opposed to the modification that is characteristic of adaptation, accidentally hides and suppresses many thriving forms of South Asian translational performativity. In light of this, to be able to discern the distinct qualities of the multifarious Indian translations of Jane Eyre presented below, it is first necessary to digress into the historical forms of Indian translational practices. Using these as a frame, it will be possible to arrive at a suitable definition of translation that may uncover a unique episteme of literary criticism for Indian translation theory.

At its very foundation, Indian civilisation is not culturally anchored in interlingual translation, unlike its European counterpart. In Europe, intellectual cultivation has been built on the edifice of translation, at first through Latin translations of the ancient Greek texts during the Roman Empire and subsequently through the Latin and later vernacular translations of the Bible.64 Europe — with its borrowed cultural roots transplanted through careful translation from Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, and Arabic — turned translation into such an art of significance and exactitude that it could unequivocally be considered a keystone in the historical formation of Europe’s many vernacular political and cultural identities, in the building of the modern European nation states, and in the wider European colonialism across the globe.65 The Christian Protestant Reformation of the early sixteenth century, for instance, coincided with the Latin and German Bible translations by Erasmus of Rotterdam and Martin Luther,66 while the Early Modern English language itself often is defined as commencing in 1611 with the printing of the King James Bible, a new English translation of the Christian scripture. Even the most recent global technological advances in digital machine translation in the twenty-first century have had their quantitative linguistic basis in the exactitude of the digital data corpus of the documents translated by the administrations of the European Union and the United Nations.

There is absolutely no comparable instance prior to modernity of any major text translated interlingually into an Indian language having a similar cultural impact on India, at least not if translation is understood narrowly as involving ‘equivalence’ in the sense in which translation was defined in 1959 by the influential Russian-American linguist Roman Jakobson, namely as a process of substituting linguistic codes entailing ‘two equivalent messages in two different codes’.67

There are, however, a few minor texts that were imported from outside of India in premodernity that continue to be influential. These include Persian and Arabic texts that were translated into Sanskrit and Indian vernaculars from the sixteenth century onwards, mostly into the South Indian Dakanī and Tamil languages as well as the Northeast Indian Middle Bengali language, as represented by the Bengali poets Ālāol (‘Alāwal, 1607–1673) and Abdul Hakim (‘Abd al-Ḥakīm, c.1600-c.1670).68 The translations are literal in nature and, anachronistically, this trait of semantic equivalence qualifies them as falling within the ambit of the modern Indian term anuvād (अनुवाद translation), which was introduced into Hindi in the late nineteenth century as a response to the English concept of translation.69 This is significant, because these seventeenth-century translations predate the introduction of the modern translational practices promulgated by Christian missionaries and European colonialists from the eighteenth century onwards.

It is worth mentioning that, parallel to these developments, in India itself other translations marked by semantic equivalence sprang up in the non-Islamic Jain communities in Western India, represented by poets such as Banārsidās of Agra (1587-c.1643) and the contemporary Hemrāj Paṇḍe, who translated entire texts from Sanskrit into Brajbhāṣā, an early form of the Hindi language that evolved from Prakrit and Apabhramsha.70 As for foreign major works of high cultural impact, it was first in modernity that they were transmitted into Indian languages. In this regard, the Bible translated into Tamil in 1706 and the Qur’an translated into Bengali in 1886 and then into Urdu in 1902 stand out.

While, in premodern times, there was no import of foreign cultures into Indian educational and intellectual institutions through interlingual translation, there nevertheless was a historic opposite movement of translation flowing out of India having far-reaching impact. From the second to the fifteenth centuries, interlingual translation of texts for the export of Indian religions and literature was prevalent, with numerous works written in Sanskrit and other Indian languages being translated into foreign languages. Thousands of Indian Buddhist scriptures and commentaries were translated into East and Inner Asian languages, in particular Chinese and Tibetan.71 Moreover, from the sixth century onwards, a number of literary and religious works were translated into Persian and Arabic, including story collections, poems, epics, and Hindu mystical works.72

Although Indian scholars often supervised the translation endeavours from Indian into foreign languages as presiding experts, these specialists never felt compelled to translate non-Indian works into the classical languages of South Asia. In fact, the dominant literary form of translation from the very inception of Indian literature has always been intralingual. Its embodiment is exegesis entailing interpretation and commentarial reiteration, as represented by the exegetic device of anuvāda (अनुवाद repetition, paraphrase). Etymologically, Sanskrit anuvāda consists of two distinct morphemes anu (अनु after) and vāda (वाद speech), and has a specific technical application in the context of a Sanskrit commentarial literary method of intralingual rewriting and supplementing of an earlier stated vidhi (विधि rule) or pakṣa (पक्ष assertion) within the one language of Sanskrit.73 For instance, a seventh-century commentator makes use of anuvāda in the sense of reiterating an opponent’s position, in Sanskrit parapakṣānuvāda (परपक्षानुवाद reiteration of others’ position), in a scholastic debate.74

Given that the hallmark of intralingual hermeneutics is a non-equivalence between the source and target texts, the early history of Indian translation is marked by a flexible intertextuality that has influenced both the interlingual exchange between the Indian indigenous languages and the degree of semantic equivalence in their literary representations.75 These translational forms range within the classical spectrum from the non-literal Kannada varṇaka (ವರ್ಣಕ retelling) to the word-for-word Sanskrit chāyā (छाया shadow), often transferring a text into multiple Indian languages as well as displaying non-linear multitextuality across traditions.

A typical exemplification of an ancient source transmitted interlingually and intertextually is the Prakrit epic Paümacarẏa (The Passage of Padma). Belonging to a genre of mahākāvya (महाकाव्य grand poem, epic), this Jain work has many commonalities with the Hindu epic Rāmāyaṇa (The Course of Rāma). The first version of the text was composed in an ancient Prakrit vernacular by the Jain monk Vimalasūri around the fifth century CE, entitled Paümacarẏa (The Passage of Padma). It was then adapted into a Sanskrit version, the Padmacarita (The Passage of Padma), in the seventh century by Raviṣeṇa. Finally, during the ninth century, the South Indian poet Svayambhūdeva adapted the story under the title Paümacariu (The Passage of Padma) into the medieval Apabhramsha vernacular, which linguistically was a precursor for Old Hindi. Although the three linguistic versions of the Paümacarẏa share the same narrative structure, they are by no means word-for-word translations of semantic equivalence and therefore could be said to belong under the notion of varṇaka (retelling).76

Another form of varṇaka (retelling) is represented in the genre of the scholarly writing of śāstra (शास्त्र treatise). Its classic example is the ninth-century text on poetics written in Old Kannada entitled Kavirājamārga (The Royal Road of Poets) by Śrīvijaya. Being an interlingual and intertextual translation of the major Sanskrit treatise on literary theory Kāvyādarśa (The Mirror of Poetry), it parallels 230 verses from this late-seventh-century classic by the poetician Daṇḍin while innovating the remaining 302 verses of the text.77

Neither of the two texts proclaim themselves as varṇaka (retelling), however, there is a medieval epic that specifically identifies itself as such, directly acknowledging its reliance on an earlier work. The case in point is the Old Kannada Vikramārjunavijaya written by Pampa (902–75 CE), which is a rendering of the Sanskrit epic Mahābhārata by Vyāsa. Already at the outset of the poem, Pampa declares:

No past poet has given a varṇaka (retelling) in Kannada of the long story of the Mahābhārata in its entirety and without any loss to its structure. In doing so, to fuse poetic description with the story elements, only Pampa is competent.78

The author describes his style of writing as a varṇaka (retelling) of the Mahābhārata as its source text. Pampa’s perception of the question of equivalence is encapsulated in one of the poem’s verses, wherein he describes himself as ‘swimming across the vast and divine ocean of the sage Vyāsa.’79 It is notable that in spite of telling the story of the Sanskrit Mahābhārata in its entirety and maintaining the internal structure of the epic, Pampa shortened the epic down to a mere 1609 verses as compared to the more than 89000 verses of the Sanskrit text. If swimming were to be seen as a trope for fluid translation of non-semantic equivalence, it could be deemed that Pampa’s poem is not only a translational adaptation but also a paradigmatic medieval example of an abridgement and, as shall be argued further on, abridgement is a defining characteristic of many of the modern Indian translations of Jane Eyre.

Parallel to varṇaka (retelling), chāyā (shadow) proliferated over the course of the first millennium CE, bringing to the fore word-for-word interlingual translation of smaller textual passages consisting of individual verses or prose sentences from the Prakrit vernaculars into Sanskrit. It was practised especially by Jain exegetes, who were masters of transposing Jain Prakrit scriptures into Sanskrit commentarial writing. Chāyā (shadow) could be considered the earliest Indian term for translation.80 Its usage is limited to commentaries and dramatic stage writing in Sanskrit, wherein it features as interpolated translation of Prakrit linguistic elements that are of non-Sanskritic provenance.

In the case of a commentary, a Prakrit pericope is first cited in its original form, then furnished with a literal Sanskrit chāyā translation, and thereupon expounded in Sanskrit prose. In the case of stage writing, a Prakrit dialogue spoken by either a woman or lower-caste man is first cited in its original form and then furnished with a literal Sanskrit chāyā translation. The use of chāyā translation, a tradition that has continued to the present day, is necessitated by the fact that the older Prakrit vernacular forms had become linguistically archaic by the middle of the first millennium.81

The indicative feature of chāyā is its precise equivalence between the Prakrit source text and the Sanskrit translation, obtained through the application of systematic principles of phonetic correspondence and through the faithful reproduction of grammatical and syntactical structures. Chāyā positively fulfils the trademarks of the modern definition of translation as ‘two equivalent messages in two different codes’ with a characteristic leeway for some level of interpretation common to all forms of literal translation.

Dictated by the rather undifferentiated nature of the Prakrit phonetic forms, subtle yet at times considerable interpretative compromises are required because the Sanskrit language is phonetically more elaborate. A conspicuous instance of such a translational interpretation from Prakrit to Sanskrit is the rendering of the Buddhist scriptural term sutta (सुत्त sermon) into the Brahmanical literary term sūtra (सूत्र thread, mnemonic formula). Instead of translating the Prakrit sutta into Sanskrit sūkta (सूक्त well-spoken, aphorism), which would likely have been the linguistically correct equivalent, the Buddhist translators selected the Brahmanical Sanskrit term sūtra in order to appropriate the prestige of this well-established Brahmanical term. Under the circumstances, a translational decision was made to avoid a rhetorically less compelling Sanskrit word sūkta, even though it was phonetically and semantically equal to the Prakrit sutta.82

It would be remiss to omit mention of the precursors to chāyā in the older Indic literature. Verily, the history of writing in India begins with a translation in the year 260 BCE, when the Indian Emperor Aśoka issued an edict incised on a rock in the frontier region of Kandahar, Afghanistan. The edict features a bilingual proclamation in Greek and Aramaic believed to have been a literal translation from a now lost common source text in a Prakrit vernacular.83

Later precursors to chāyā dating to the first century BCE involve literal translations of Prakrit portions of texts into another Prakrit vernacular or Sanskrit. These include the early Buddhist aphoristic treatise Dhammapada (Words of Dharma) rendered from the Prakrit Pāli language into the Prakrit Gāndhārī language under the same title and into an enlarged Sanskrit recension entitled Udānavarga (Chapters of Utterances). The translations share with their source an underlying textual structure and some of the chapter headings and verses.84

The above short exposition of the history of translation in premodern India demonstrates a varying degree of equivalence in the classical textual practices of literary transmission within one language or across languages through anuvāda (paraphrase), varṇaka (retelling), and chāyā (shadow). Accordingly, Jakobson’s definition for translation would, if applied to the Indian literary heritage, eclipse and consequently reject the premodern translational practices. Although the theory of equivalence has been dislodged in recent scholarship, it reverberates in the proclamations made by some contemporary literary critics, who argue that speaking of translation in premodern India ‘makes no cultural sense in this world’,85 amounts to ‘a non-history’ prior to the colonial impact in the nineteenth century,86 or requires demoting premodern Indian translation to transcreation.87 In contrast, it could be argued that the classical Indian intertextual processes fall well within the bounds of the etymological configuration of the classical Latin notions of translatio (carrying across), transferre (transfer), and vertere (turning) of a text,88 whereby the European metaphor of semantic movement is echoed in the Indian images of verbal repetition. Among contemporary Indian academics, there are therefore some who have consistently employed the term translation for the premodern period also.89

Counterintuitively, the classical translational practices of anuvāda (paraphrase), varṇaka (retelling), and chāyā (shadow) have not abated in modern India and exist side by side with the new forms of interlingual translation that became commonplace in British colonial India. By the nineteenth century, numerous translations of European and non-European works were produced in all Indian languages and copious translations between the different Indian regional languages themselves began to flourish across the continent initiating the era of modern translational practices alongside scholarly methods of philology.90

Post-independence India has become home to new sophisticated paradigms of semantic equivalence, fusing traditional forms of linguistic sciences with modern forms of vernacular textualities. Innovative efforts to produce modern literal translations of classical Indian works have drawn on indigenous reading practices to balance the subjectivity of translation with the objectivity of grammatical scrutiny. It suffices to mention the large body of work by the contemporary Rajasthani scholar Kamal Chand Sogani employing what is known as the samjhane kī Sogāṇī paddhati (समझने की सोगाणी पद्धति Sogāṇī Comprehension Method) of vyākarṇātmak anuvād (व्याकरणात्मक अनुवाद grammatical translation).91

It is in this ambience that the modern Hindi concept of anuvād (translation) was coined and persists as a household term into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in the complex literary landscape of India, and it is in this sense that the Indian translations of Jane Eyre are referred to as anuvād (translations).92

The below examination of the numerous anuvād (translations) of Jane Eyre into Indian bhāṣā (भाषा vernaculars) accordingly reveals a plethora of underground renditions of the literary work that stubbornly resist the superimposition of academic universalising definitions onto their proliferating praxis. The publications will be reviewed in chronological order in terms of their geographical, linguistic, and bibliographical distinctions. Through considering their varying length and degree of abridgement, through identifying their paratextual self-proclamations as translations or other textual forms, and through unpacking their modes of acknowledgement of the original novel and its author, it is hoped to reach a conclusion as to their translational status.

Following the period of the six decades of Indian Jane Eyre adaptations bracketed by the appearance of the Bengali novel Sarlā in 1914 and the release of the Telugu film Śānti Nilayam in 1972, the late 1970s witnessed the dawn of the era of Indian Jane Eyre translations. Only a single translation into Tamil had been produced earlier in the 1950s. To date, at least nineteen translations of Jane Eyre into nine South Asian languages have been published throughout India, Bangladesh, and Nepal: Tamil (1953), Bengali (1977, 1990, 1991, 2006, 2010, 2011, 2018, 2019), Punjabi (1981), Malayalam (1983, 2020), Gujarati (1993, 2009), Nepali (1997), Assamese (1999, 2014), Hindi (2002), and Kannada (2014).

The very first translation of Jane Eyre into an Indian language was published in 1953 by the Tirunelvēlit Ten̲n̲intiya Caivacittānta Nūr̲patippuk Kal̲akam (திருநெல்வேலித் தென்னிந்திய சைவசித்தாந்த நூற்பதிப்புக் கழகம் The South India Saiva Siddhanta Publishing Society of Tirunelveli) in the South Indian city of Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu. It is a translation into Tamil language bearing the title Jēn̲ Ayar (ஜேன் அயர் Jane Eyre). The translator is given as Kācināta Piḷḷai Appātturai (காசிநாத பிள்ளை அப்பாத்துரை, 1907–1989). The book consists of 110 pages. A slightly enlarged reprint in 143 pages was brought out under the title Jēn̲ Ayar: Ulakap pukal̲ per̲r̲a nāval (ஜேன் அயர்: உலகப் புகழ் பெற்ற நாவல் Jane Eyre: A World-Renowned Novel) in 2003 by the publishing house Cāratā Māṇikkam Patippakam (சாரதா மாணிக்கம் பதிப்பகம்) in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. The translator’s name is given in the reprint as Kā Appātturaiyār (கா அப்பாத்துரையார்).

The second translation was issued in 1977 in Dhaka, Bangladesh, by the publishing house Muktadhārā (মুক্তধারা). Entitled Jen Āẏār (জেন আয়ার Jane Eyre), it was translated into Bengali by Surāiyā Ākhtār Begam (সুরাইয়া আখতার বেগম) in merely 43 pages.93

The third translation appeared four years later in 1981. It was rendered into the Punjabi language in the North-Western Indian state of Punjab under the title Sarvetam viśva mārit Jen Āir (ਸਰਵੇਤਮ ਵਿਸ਼ਵ ਮਾਰਿਤ ਜੇਨ ਆਇਰ The World-Renowned Jane Eyre) and was printed in 2000 copies by the Bhāṣā Vibhāg (ਭਾਸ਼ਾ ਵਿਭਾਗ Language Department) in the city of Patiala, Punjab. The book’s front matter lists Charlotte Brontë as the mūl lekhak (ਮੂਲ ਲੇਖਕ original author) and the anuvādak (ਅਨੁਵਾਦਕ translator) as Kesar Siṅgh Ūberāi (ਕੇਸਰ ਸਿੰਘ ਊਬੇਰਾਇ, 1911–1994), who was a university professor. The precise number of pages of the slim volume is not known.94