The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

11. Emotional Fingerprints: Nouns Expressing Emotions in Jane Eyre and its Italian Translations

© 2023 Paola Gaudio, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.17

Introduction

Good writers are able to make every novel a unique representation of emotional dynamics, a cognitive roller-coaster of emotional ups and downs, as their empathic readers let the narrator take their hand and lead them across the universe of narrative fiction, which is fraught with emotions of all kinds. If this is possible, it is because writers have a finely-tuned knack for triggering vicarious emotions by using mere words, and they can differentiate very subtly among the vast array of emotions made available by their language.

Charlotte Brontë had a natural talent for story-telling, and her passionate nature ensured that her novels should be imbued with a wide range of emotions.1 It has been almost two centuries now since her novel was first published, and the main reason it is still such an engaging story today is because of the stirring emotions that capture its readers.2 Even though times change and cultures develop in different directions, it seems that we share an inner core of empathy that responds emotionally to the (mis)adventures of others’ lives, even though these go back two hundred (or even two thousand for that matter) years and never really existed beyond the written page. Sometimes emotions can be stirred without even labelling them as such in the narrative, and a love scene can be such even if the word love is not mentioned at all. It is, however, revealing to observe the type and frequency of those that are actually present in a canonical novel such as Jane Eyre and see how these relate to the characters and the plot. High frequency of use is certainly a key indication of the relevance of a certain emotion in the novel. Sometimes, however, what is missing can be equally revealing in terms of themes and narrative style, hence it deserves some attention. The first part of this essay addresses the issue of frequency of emotion-nouns in Jane Eyre and, on the basis of all the data collected, insights are then gained and discussed with regard to the themes of the novel and the depiction of its characters.

As one of the classics of nineteenth-century British literature, Jane Eyre is not published in English only, but in a variety of languages, including Italian. The second part of this study is an attempt to understand whether and to what degree the quantitative pattern of emotion-nouns in the original English text is duplicated in Italian. In order to do this, the consistency in the frequency of Italian emotion-nouns is first analysed across the translations, then compared with the findings from the English original. Lexical correspondences between English and Italian emotion-nouns are thus identified and quantified.

The results of the quantitative analysis of emotion-nouns in individual translations are finally presented in the form of what are called emotional fingerprints, i.e., a visual representation, by means of word clouds, of the emotions characterizing each version of the book.

The following methodological section accounts for the selection method of emotion-nouns in the English original as well as in the translations; it sheds light on the issues deriving from the syntactic asymmetries between English and Italian in relation to this specific research; and it outlines some basic statistical principles applied to process the data and gain insight on the whys and hows of the results obtained.

Methodology

The approach to the study of emotions in both Jane Eyre and its translations is definitely inductive, meaning that the intent of this research is not to implement any specific theory on quantitative or comparative analysis of data, on inter- or intra-linguistic translation, or on the definition of emotions, but rather to observe the specificities of the texts at stake and, from that, apply any type of analysis, statistical or otherwise, that appears to be able to point to patterns and anomalies. Such an approach applies to all sections of this essay, from the discussion of emotions in the source text, to the analysis of the corpora, to the statistical data, and to the creation of emotional fingerprints in the form of word clouds as a means to visually represent the idiosyncrasies of the translations. What I am offering is neither a close reading nor a distant one: it is rather a transversal reading through the eyepiece of emotional lexis across the source text and its translations.

Given the general framework, a few words on how the data was gathered, and on the constraints, limitations, and exceptions that were necessary to lend rigour and coherence to the results, are certainly required. The English source text is the 2006 Penguin edition of Jane Eyre in .txt format. The Italian texts are .txt files of eleven translations, ranging from the anonymous one published back in 1904 to the more recent 2014 translations by Stella Sacchini and by Monica Pareschi.

The focus being emotions, namely an over-reaching, all-encompassing category, the object of study is narrowed down to the lexical items expressing emotions and belonging in the syntactic category of nouns, whether singular or plural. As a consequence, it should be noted that, because of this, the figures underestimate emotions expressed by other parts of speech (adjectives, adverbs, and verbs). Thus, in the case of love, only the noun is considered, but not any of its derivatives loved, loving, lovingly, loveless, unloving, lovely, etc. The same applies to other words such as fear, hope or wish, and their derivative forms (fearful, fearless, fearlessly, etc.). Even though there is a quantitative underestimation of emotions as expressed by other parts of speech, the peculiarity of nouns is that, whilst verbs describe what someone does,3 adverbs indicate how something is done, and adjectives are descriptive by nature, nouns are either subjects or objects of any statement, they either originate the predicate or complete it: in other words, they constitute the fulcrum of any utterance by naming what topic is being discussed, evoked, analysed, commented upon, or dealt with — either by the characters themselves or by the fictional narrator — and this is precisely why a noun-focused analysis cannot be overlooked. There is another reason for narrowing down the field of research to nouns only, and it has to do with the comparability — or lack thereof — of syntactic roles between languages. Even excluding all derivatives, in English the word love can still be a noun or a verb; not so in Italian, where there are two different words: the noun amore, and the verb amare. Sorpresa, in contrast, can be both a verb and a noun, just like its English equivalent surprise. Yet, there is no correspondence between the syntactic roles of these verb-forms in the two languages: surprise is either present indicative, imperative, or exhortative in English; but in Italian, the verb-form sorpresa is a female singular past participle, also used as adjective. Similarly, sorprese and surprises, in addition to being plural nouns, can also be verbs in the third person singular: in Italian, sorprese is a past tense (lei mi sorprese, ‘she surprised me’), in English it is a present (‘she surprises me’). Like the singular sorpresa, its plural sorprese can be past participle and adjective too — not so in English.

Syntactic ambiguity applies to words which can be nouns, verbs, or adjectives:4 love and loves, doubt and doubts, regret and regrets, etc. these can all be either nouns or verbs — which is actually a common phenomenon. Therefore disambiguation is necessary. More in detail, plural nouns can be homonymous with a past participle or a second person singular of the verb in Italian; in English, they can be homonymous with a third person singular of the present indicative. Sometimes — not always — the ambiguity is symmetric and occurs in both languages: desideri and desires, tormenti and torments can all be either plural nouns or verbs (respectively, second person singular of the verbs desiderare and tormentare in Italian; third person singular of the verbs to desire and to torment in English).

For the corpora to be genuinely comparable, syntactic roles must not be mixed up. Following these adjustments, and since the scope of this study comprises exclusively nouns, each token should — ideally — have its equivalent in the translations. This latter claim however, is not at all a given since — as will be extensively shown — there are substantial variations in the translations, with certain emotion-nouns popping up a lot more often than in the original or disappearing altogether.

As to what constitutes an emotion and what not, the plethora of taxonomies of emotions varies greatly in the scientific world, depending on the aim of the classification and the perspective from which they are considered (psychological, cognitive, neurological, anthropological, etc.).5 Things are complicated even further by the relationship between emotion and reading, which implies a different way of experiencing emotion, and which is based on empathy.6 The aim of this essay is not, however, to recreate any taxonomy of emotions, neither it is to describe the dynamics at play between text and emotional reactions on the part of the readers. Since the approach is inductive, emotion theories such as Paul E. Griffiths’s7 and Antonio Damasio’s8 have only worked as general guidelines in the initial approach to the source text. The inductive process that led to identifying the spectrum of emotion-nouns used by Charlotte Brontë in Jane Eyre took place by analysing the word-frequency list of the novel in English. The nouns that were thus recognized as expressing emotions in English have then paved the way to the identification of emotion-nouns in the Italian translations, whose word lists were also individually examined.

Etymologically, an emotion stirs something inside and, for the purposes of this study, it can be defined as whatever arises instinctively or spontaneously in the perceiver’s consciousness following a stimulus. Such stimulus can range from an actual event to a mere mental image. An emotion is not the same as a physical sensation (feebleness, coldness, etc.), even though the two are closely related as emotions always involve some physical response like increased heart-beat or dilated pupils; and it is not a behaviour either (kindness, rudeness, etc.) even though behaviours are often either causes or consequences of an emotional response. Within this general framework, any noun which could arguably be considered some type of emotion was included in the selection. The word emotion itself has also been included in the research for obvious reasons of self-reference, along with its near-synonyms passion, sentiment, sensation, and feeling. It goes without saying that these words do not express any specific emotion themselves. However, their relevance stems from the purpose they serve of indicating that the semantic field of the portion of text in which they occur revolves indeed around emotions.

A broad parameter for the quantitative selection of the emotional lexis for the contrastive analysis is that, for a noun to be taken into consideration, it needs to have a frequency equal to or higher than ten occurrences, either in the source text or in one of the translations. There is one exception to this rule and it concerns the word misery, which was included because of its peculiarity, and which will be analysed in the section ‘English–Italian equivalents and outliers’. Such inclusion does not skew the analysis, because the emphasis of the contrastive analysis is not so much on the quantitative identification of emotional-nouns in the novel — which is dealt with in the next section — but on the differences and similarities between source text and target texts: thus, the addition of one more case simply makes the enquiry a little more extensive.

Once the data were gathered, statistics provided the tools necessary to gain insights on the results. At the basis of the statistical analysis there is the fundamental notion of the normal curve, which is a bell-shaped, symmetric curve representing a great part of natural and societal phenomena. The assumption is that, in the infinite world of possibilities offered by translation, the different translations of a word are normally distributed (i.e., their distribution follows the normal curve). The word hate, for example, is likely to be translated as odio by the vast majority of Italian translators and on most occasions. Some, however, will now and then translate it with disprezzo (contempt), repulsione (repulsion) or maybe omit it altogether, with frequencies which decrease as the target word becomes more and more unusual. In this research, the standard deviation (SD) measures the variability of the translations for each emotion-noun: if the standard deviation is low, there is greater consistency in how a word is translated, if it is high, there is little consistency in its translations. Z-scores represent the frequency of a certain value (in this case, the number of occurrences of an emotion-noun) expressed into standard deviations. The more a z-score is closer to zero, the more it approaches the mean, i.e., the more similar its frequency is to the average frequency of that same noun across the translations. Most values fall within the interval ±1 SD (i.e., their z-score is between –1 and +1). Values that fall outside this interval are considered outliers, if the values lie outside the interval ±2 SD, they are extreme outliers.

One more statistic that will be used is the standard error (SE), which is another measure of dispersion. In fact, in the analysis that follows, the standard error is a measure of dispersion of the distribution of standard deviations. In other words, the standard error tells us whether the variability observed per each emotion-noun in the eleven translations is normal or not. Since the standard error is basically just a type of standard deviation, the same rules apply, therefore values that fall outside the interval ±1 SE will be considered outliers; and those that fall outside the interval ±2 SE will be considered extreme outliers.

Hence, the present research shows which emotion-nouns are used with similar frequencies across the translations and which are not. The mean frequency of every Italian emotion-noun is then compared to the frequency of its usual equivalent in the English source text. This allows us to determine whether and to what extent there actually exists a correspondence between English and Italian emotion-nouns in Jane Eyre. Lastly, since z-scores measure how typical or unusual the frequency of an emotion-noun is, they will be the reference values used to recreate the emotional fingerprints of each translation in the final section.

Emotions in Jane Eyre

The list of nouns expressing emotions in the original English version of Jane Eyre is provided in Table 1. As can be seen at a glance, love ranks first (81 occurrences), pleasure second (78), hope third (57), doubt (52) fourth, and fear fifth (47). Overall, there are at least 78 types of emotions and an average of 30.3 tokens per chapter. The list, however, is not exhaustive, since it contains only the most frequent emotions (>10) and a selection of the lesser used ones, and does not account for those which occur only once, like apprehension, disdain, envy, foreboding, tedium, trepidation, etc. The number of nouns expressing emotions in Jane Eyre is therefore noteworthy, especially with regard to the sheer linguistic variety of the emotions Charlotte Brontë mentions in her narrative.

|

Emotion-noun |

Freq. |

Emotion-noun |

Freq. |

|

love |

81 |

anguish |

10 |

|

78 |

disgust |

10 |

|

|

hope |

57 |

melancholy |

10 |

|

doubt |

52 |

jealousy |

9 |

|

47 |

anxiety |

8 |

|

|

wish |

35 |

impatience |

8 |

|

pain |

33 |

misery |

8 |

|

affection |

30 |

anger |

7 |

|

passion |

30 |

hate |

7 |

|

delight |

27 |

regret |

7 |

|

solitude |

25 |

woe |

7 |

|

pride |

24 |

concern |

6 |

|

happiness |

23 |

ire |

6 |

|

pity |

23 |

loneliness |

6 |

|

courage |

22 |

sadness |

6 |

|

suffering |

22 |

satisfaction |

6 |

|

sympathy |

22 |

scorn |

6 |

|

21 |

tenderness |

6 |

|

|

excitement |

18 |

repentance |

4 |

|

17 |

wrath |

4 |

|

|

grief |

17 |

aversion |

5 |

|

surprise |

17 |

contempt |

5 |

|

terror |

17 |

distress |

5 |

|

despair |

16 |

indignation |

5 |

|

shame |

16 |

desperation |

4 |

|

sorrow |

16 |

hesitation |

4 |

|

desire |

14 |

agitation |

3 |

|

fury |

14 |

compassion |

3 |

|

enjoyment |

13 |

humiliation |

3 |

|

horror |

13 |

longing |

3 |

|

curiosity |

12 |

rage |

3 |

|

disappointment |

12 |

restlessness |

3 |

|

dread |

12 |

yearning |

3 |

|

agony |

11 |

bewilderment |

2 |

|

gratitude |

11 |

bitterness |

2 |

|

mercy |

11 |

fun |

2 |

|

relief |

11 |

torment |

2 |

|

remorse |

11 |

wretchedness |

2 |

|

wonder |

11 |

||

|

admiration |

10 |

|

TOT Types: |

78 |

|

TOT Tokens: |

1,152 |

|

Mean: |

14.8 |

|

SD: |

15.4 |

|

Mean per chapter: |

30.3 |

|

Word Count:9 |

58,598 |

|

Emotion-nouns %: |

1.96 |

Table 1: Emotion-nouns in Jane Eyre

As to the ranking of individual emotions, love trumps them all — as any respectable Victorian female Bildungsroman is expected to do.

Pleasure is a bit more problematic. The first instinct would be to disregard it altogether because of its recurrent use in today’s everyday language, which often has little to do with actual emotions and refers rather to fixed expressions like ‘it’s a pleasure to meet you’ — which are commonly uttered even when the underlying emotion is closer to indifference or nuisance rather than true pleasure. However, on reading the various instances of pleasure in the novel, and given the extremely high frequency of the word itself, it cannot be altogether dismissed — at least not without first wondering whether or not it plays some significant role in Jane Eyre.

It does. Many instances of the word occur in relation to Rochester and refer either to his dissolute lifestyle prior to proposing to Jane, or to the pleasure both Rochester and Jane find in sharing each other’s company. In all such cases it is evident that the word carries with it sensual rather than spiritual overtones. Still, the novel does not point to purely hedonistic quests, and those Jane Eyre narrates have also to do with small, everyday pleasures that derive, for example, from her enjoying Miss Temple’s company in an otherwise hostile environment, from experiencing genuine sisterhood for the first time, or from running in the wind:

[Miss Temple] kissed me, and still keeping me at her side […] where I was well contented to stand, for I derived a child’s pleasure from the contemplation of her face.10

There was a reviving pleasure in this intercourse, of a kind now tasted by me for the first time — the pleasure arising from perfect congeniality of tastes, sentiments, and principles.11

It was not without a certain wild pleasure I ran before the wind, delivering my trouble of mind to the measureless air-torrent thundering through space.12

Even when sensual in nature, the pleasures Jane craves are very much delimited by her sense of modesty, her rationality, and her greater intent to be an independent, self-respecting woman. She is in fact well aware of the dangers posed by the unrestrained pleasures Rochester himself succumbed to, that ‘heartless, sensual pleasure — such as dulls intellect and blights feeling’.13 And when he claims that, ‘since happiness is irrevocably denied me, I have a right to get pleasure out of life: and I will get it, cost what it may’, Jane’s reply is: ‘then you will degenerate still more, sir’.14

However, within the limits imposed extra-diegetically by Victorian values, and intra-diegetically by Jane’s very nature, she herself gleefully and unhesitatingly appreciates the pleasures life can give, the ‘so many pure and sweet sources of pleasure’15 she is granted daily at Moor House, for example, or the short-lived pleasure of the conqueror’s solitude she enjoyed when she stood up to Mrs Reed in chapter 2. Along the same lines, when St John proposes, she refuses to succumb to a life devoid of pleasures and filled with miseries only, because ‘God did not give her [her life] to throw away’.16

Jane Eyre is thus a hedonistic quest to the extent that pleasure and love are the ultimate goals of any human being — unless it is St John, of course. His endgame is misery, to the point that not only does he willingly endure it — not unlike Helen Burns — but he actively pursues it. Yet even to him, in his eyes, suffering — and its siblings: endurance, perseverance, and restraint — become indeed pleasures, for it is them that allow him to actually enjoy life, giving it the meaning he craves and, ultimately, to be reunited with his beloved Jesus Christ.

Hence, considering the occurrence of individual emotions, it is love and pleasure that stand out the most, followed by hope, doubt, fear, and wish.

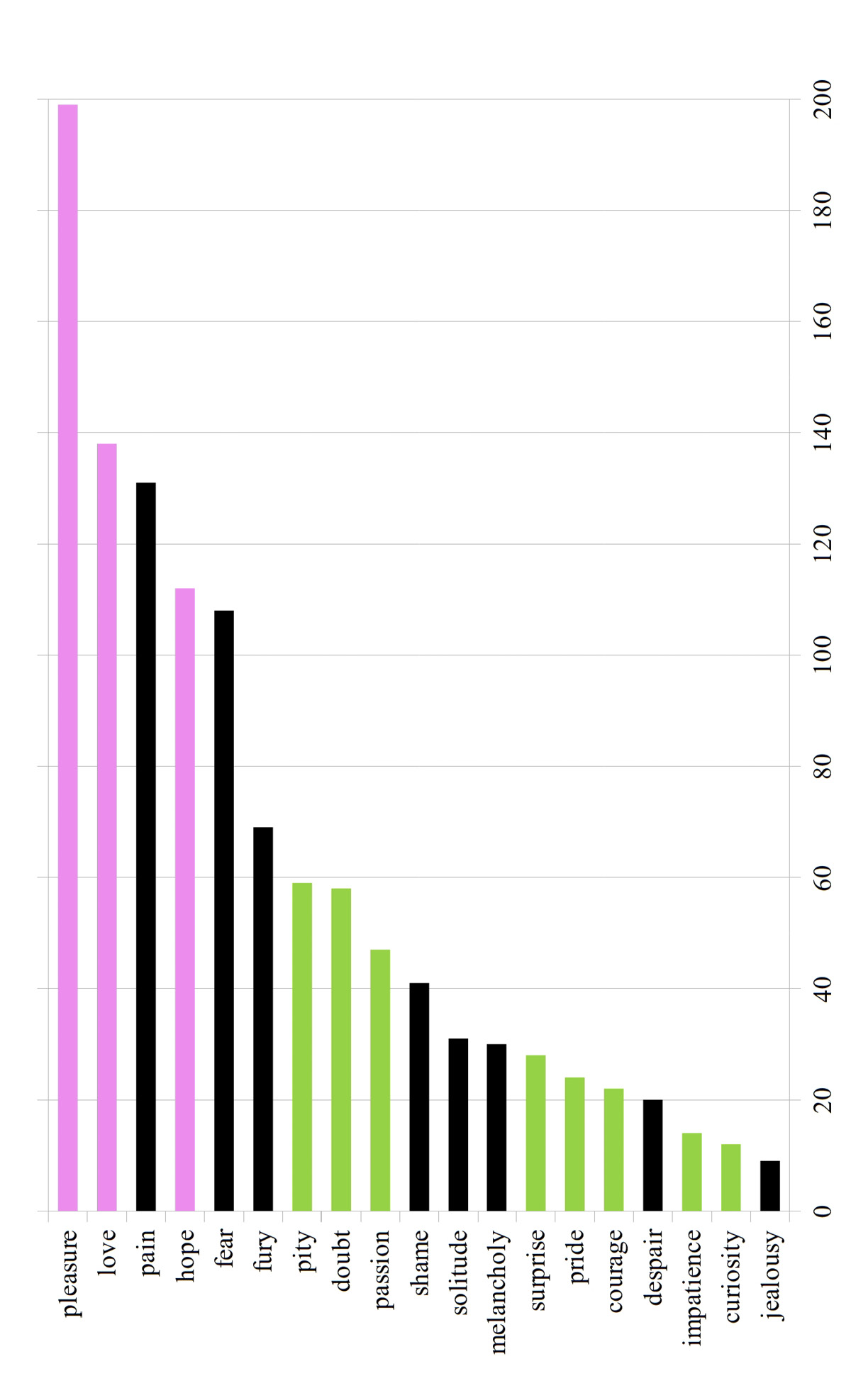

Things change a little if we pool together synonyms or near-synonyms (e.g., pain and suffering, despair and desperation), as well as lexical labels that refer to some common underlying emotion, even though there may be different nuances involved (e.g., terror is fear felt to the utmost degree; affection is a bland type of love, etc.). The more complex an emotion is, the more it shares traits with other emotions: jealousy, for example, which in the array stands for an independent category — like courage, curiosity, and pride — might easily be perceived as inherent in love and desire. This is why other similar groupings could certainly be created on the basis of perceived contiguity between emotions. The groupings suggested here are represented in Figure 14, and they are labelled by the most frequent emotion within the sub-set:

- pleasure, happiness, joy, excitement, enjoyment, delight, relief, satisfaction, fun;

- love, affection, tenderness, gratitude, admiration;

- pain, suffering, grief, sorrow, agony, anguish, woe, misery, distress, torment;

- hope, wish, desire, longing, yearning;

- fear, terror, horror, dread, anxiety, concern, aversion, disgust;

- fury, anger, rage, ire, wrath, hate, scorn, contempt, indignation, bitterness;

- pity, mercy, sympathy, compassion;

- passion, emotion;

- shame, remorse, regret, repentance, humiliation;

- solitude, loneliness;

- melancholy, sadness, wretchedness, disappointment;

- surprise, wonder;

- doubt, hesitation, bewilderment;

- despair, desperation;

- impatience, restlessness, agitation.

A further differentiation is suggested by colour: positive emotions are represented in pink, negative emotions in black, mixed emotions in green. Like in any fairy tale, in Jane Eyre too, good triumphs over evil, as positive emotions grouped under the label pleasure are by far the most frequent ones, followed by love and competing closely with a long tail of negative and mixed emotions, making the battle even more engaging. If we pool all positive emotions (in pink, 449 occurrences) and all negative ones (in black, 439 occurrences), their frequency is roughly the same, with positive emotions exceeding the negative by only 10 points. It is even more interesting to notice that negative emotions are scattered among a greater variety of nouns (40 nouns in 8 groupings), whereas the range of nouns expressing positive emotions is much more limited (19 in 3 groupings). Even so, both pleasure and love still trump all other groupings — with an inversion if compared to the individual frequencies of Table 1.

Love ranks second then, and it is in good company, because its existential synonym — pain — ranks third by just a few occurrences. In Italian, love (amore) actually rhymes with pain (dolore), and they do tend to go hand in hand, as the latter swiftly replaces the former if its object is made unavailable for whatever reason. If love and pain belong in the realm of reality — albeit fictional — hope and fear are their parallels in the realm of possibility. Hope that difficulties will be surmounted eventually and that love, in whatever form, will conquer all; and fear that the positive emotions might be taken away and replaced by everlasting negative ones.

The words hope, wish, desire, longing, and yearning have been pooled together because they all indicate a void to be filled: from Jane’s perspective it may be sexual desire for Rochester, but also a melancholic longing for the affection of a loving family, the material wish for food and shelter when she had neither, an intense desire for liberty or, were this not to be granted, at least for a new servitude:

I desired liberty; for liberty I gasped; for liberty I uttered a prayer; it seemed scattered on the wind then faintly blowing. I abandoned it and framed a humbler supplication. For change, stimulus. That petition, too, seemed swept off into vague space. ‘Then,’ I cried, half desperate, ‘grant me at least a new servitude!’.17

This desire to fill some existential void is naturally not peculiar to Jane, since it characterizes any existential quest — in fiction no less than in real life — and clearly affects other characters as well, from Helen’s desire to forgive and accept, to John Reed’s unquenchable thirst for vice, Eliza’s wish for quiet and order, St John’s visionary mission, and Rochester’s predicament since before he met Jane (i.e., the difficulty he repeatedly experienced in his quest to find a soulmate able to fill his need for companionship in order to avert his deep-seated solitude). Even Bessie and Miss Temple are ultimately defined by their desire to have a family of their own, and finally embrace the love this entails.

Jane Eyre is therefore primarily a novel about pleasure, love, pain, hope, and fear, but it also concerns doubt, solitude, fury, pride, courage, and an amazing plurality of further emotions, whether considered individually or grouped as in Figure 14. These kinds of emotion are not at all dissimilar from those usually experienced, to varying degrees, in any ordinary life: their peculiarity in Jane Eyre lies in the unique entanglement provided by the plot and by the narrative skills of its author.

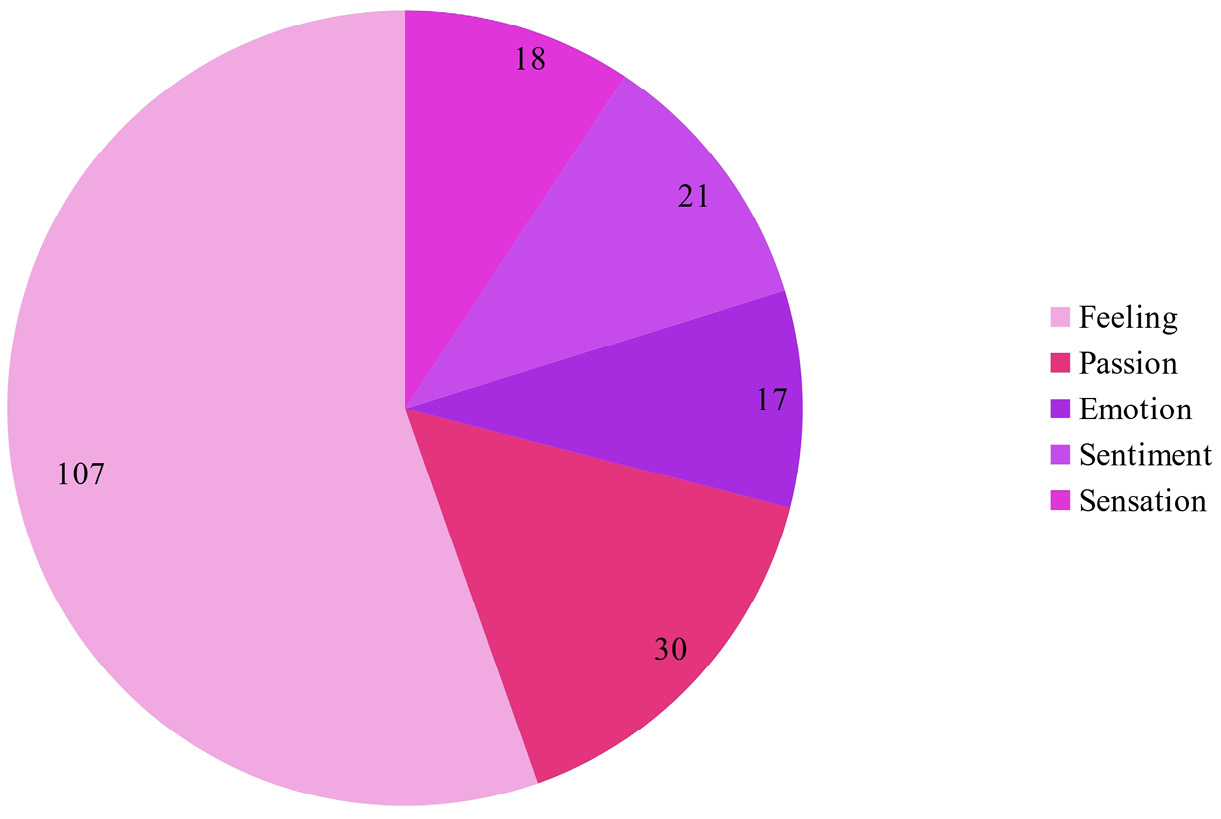

Fig. 15 Frequency of ‘emotion’ and its near-synonyms

As for the word emotion itself and its near-synonyms feeling, sensation, passion, and sentiment, they occur 193 times altogether (Figure 15) i.e., an average of 5 times per chapter and, together with the tokens in Table 1, they amount to 2.2 % of the total word-count (function words excluded).

That the noun feeling should be the one used the most is not surprising given its overarching meaning. A different matter is the word passion. Hidden in its high frequency lurks a potentially disruptive challenge affecting the Victorian values of modesty and restraint. Even though not an emotion itself, passion works as an intensifier of emotions. If felt with passion — which etymologically derives from the Latin patior, to suffer, and thus indicates that the intensity of what is felt is such that it actually becomes painful — any emotion becomes excessive, uncompromising, difficult if not impossible to control — much less to suppress — and thus poses a genuine threat to the established order.

Emotion-Nouns in the Italian Translations

In an ideal — slightly boring — universe, each word would have its equivalent in any other language: the occurrences of, say, love would repeat themselves with the same frequency in all translations, in all languages — and the same would be true of any other noun, verb, adjective, etc. In an infinite number of translations, the distribution of occurrences of the equivalents of love would be normal, its variability extremely low (i.e., small standard deviation) and due to the occasional random error. The real world is of course a little more complicated. So it happens that such hypothetical equivalence tends to go awry. Not always, though. In the prismatic variability of translation, constants can still be identified.

These occur when the measure of variability of translation-equivalents is below average. From a statistical point of view, every distribution of values (in this case, the occurrence of emotion-nouns in Italian) varies to a certain degree from its mean. One of the possible measures of such variability is the standard deviation and its related z-score statistic. The observed minimum and maximum range of the standard deviation in the data gathered here is 0.8 and 20. The higher the standard deviation, the more the distribution varies (i.e., the frequency of the same emotion-noun varies across the translations); the lower the standard deviation, the less variable the distribution (i.e., there is more consistency in the frequency of the same emotion-noun in the translations). As to z-scores, these measure how far the variability of a certain value is from the average. In the following tables, z-scores refer to the standard error (SE), i.e., they indicate whether the standard deviation of a particular emotion-noun is higher (z-score >0) or lower (z-score<0) than the average standard deviation (z-score=0). High SE z-scores indicate that there is little or no consistency in the frequency with which an emotion-noun occurs across all translations; low SE z-scores indicate consistency, and SE z-scores equal to or close to zero indicate that the variability of that emotion-noun is around average.

The nouns in the table below therefore represent, in decreasing order, emotions whose frequency is most consistent across the translations,18 with rimorso (remorse) ranking first. It will be noticed that the mean frequency of some of them is rather low: hence, by virtue of the scarcity of occurrences, their consistency is only partially significant. Of greater interest are those words whose mean frequency is relatively high, such as felicità (happiness, 37 occurrences on average), disperazione (despair/desperation, 23.2 occurrences on average) and orgoglio (pride, 20.4 occurrences on average), which appear with close to the same frequency in all translations: the frequency of — for example — felicità is exactly the same in Pozzo Galeazzi, Reali, D’Ezio and Sacchini (40), with the other translators using it slightly less, like Gallenzi (39), Déttore (36), etc., down to Pareschi, with her 32 occurrences, who therefore lowers the mean value a bit more. That SE z-scores should point to a lower-than-normal dispersion rate in the frequencies of disperazione (–0.60), felicità (–0.55), and orgoglio (–0.52), across the translations is significant precisely because of their relatively high frequencies.

The list of emotion-nouns that are consistently reproduced in all the translations are therefore listed in Table 2 below. Nouns with the highest mean frequencies are highlighted in grey:

|

Emotion-noun |

Usual English equivalent |

Mean |

SD |

SE z-score |

|

|

1 |

rimorso |

remorse |

11.8 |

0.8 |

–1.21 |

|

2 |

gelosia |

jealousy |

8.6 |

1.1 |

–1.13 |

|

3 |

commozione |

1.1 |

1.2 |

–1.10 |

|

|

4 |

agonia |

agony |

1.5 |

1.4 |

–1.03 |

|

5 |

rimpianto |

regret |

7.6 |

1.6 |

–0.99 |

|

6 |

delusione |

disappointment |

10.6 |

1.7 |

–0.95 |

|

7 |

ammirazione |

admiration |

13.5 |

1.8 |

–0.93 |

|

8 |

disprezzo |

contempt |

11.9 |

1.9 |

–0.91 |

|

9 |

infelicità |

misery |

2.8 |

1.9 |

–0.89 |

|

10 |

curiosità |

curiosity |

14.7 |

2.1 |

–0.85 |

|

11 |

divertimento |

fun |

4.9 |

2.5 |

–0.72 |

|

12 |

impazienza |

impatience |

12.0 |

2.6 |

–0.70 |

|

13 |

disgusto |

disgust |

8.6 |

2.8 |

–0.65 |

|

14 |

odio |

hate |

12.9 |

2.8 |

–0.64 |

|

15 |

amarezza |

bitterness |

9.9 |

2.8 |

–0.64 |

|

16 |

malinconia |

melancholy |

7.7 |

2.9 |

–0.62 |

|

17 |

godimento |

enjoyment |

6.3 |

2.9 |

–0.61 |

|

18 |

delizia |

delight |

3.1 |

2.9 |

–0.60 |

|

19 |

disperazione |

despair/desperation |

23.2 |

2.9 |

–0.60 |

|

20 |

felicità |

happiness |

37.0 |

3.1 |

–0.55 |

|

21 |

sconforto |

discouragement |

2.4 |

3.1 |

–0.54 |

|

22 |

eccitamento/eccitazione |

excitement/excitation |

7.1 |

3.1 |

–0.54 |

|

23 |

preoccupazione |

concern |

7.7 |

3.2 |

–0.54 |

|

24 |

gratitudine |

gratitude |

12.5 |

3.2 |

–0.53 |

|

25 |

orgoglio |

pride |

20.4 |

3.2 |

–0.52 |

|

26 |

meraviglia |

wonder |

6.2 |

3.3 |

–0.50 |

Table 2: High consistency

At the other end of the spectrum, there are those emotions that do not have much consistency in the frequency with which they appear in each translation, and whose SE z-score is >0.5 (here it is nouns with the lowest mean frequencies that are highlighted in grey):

|

Emotion-noun |

Usual English equivalent |

Mean |

SD |

SE z-score |

|

|

1 |

ansia |

anxiety |

10.7 |

7.2 |

0.61 |

|

2 |

timore |

dread |

19.4 |

7.4 |

0.66 |

|

3 |

pietà |

mercy |

25.3 |

7.7 |

0.76 |

|

4 |

collera |

choler/wrath |

10.8 |

8.2 |

0.89 |

|

5 |

piacere |

86.8 |

8.3 |

0.92 |

|

|

6 |

simpatia |

sympathy |

15.5 |

8.6 |

1.00 |

|

7 |

amore |

love |

88.0 |

8.7 |

1.04 |

|

8 |

sofferenza |

suffering |

27.1 |

8.8 |

1.07 |

|

9 |

pena |

pity |

29.3 |

10.8 |

1.64 |

|

10 |

dubbio |

doubt |

48.7 |

13.0 |

2.25 |

|

11 |

gioia |

57.6 |

13.0 |

2.26 |

|

|

12 |

dolore |

pain |

39.8 |

13.6 |

2.43 |

|

13 |

paura |

81.2 |

20.0 |

4.26 |

Table 3: Low consistency

Unsurprisingly, their mean frequency is relatively high. Indeed, the correlation coefficient between frequencies and z-scores happens to be strongly positive (+0.7): in other words, emotion-nouns whose frequency is higher tend to have greater variability, and vice versa. That such correlation should only be strong and not perfect explains why even lower frequency words like ansia (anxiety, 10.7 occurrences on average) and collera (choler, 10.8 occurrences on average) make it among the least consistent ones (SE z-score >0.5), whereas the z-score of amore (love, 1.04 SE z-score), which has the highest mean frequency in the selection (88), is virtually identical with that of simpatia (sympathy, 1 SE z-score), whose frequency is much lower (15.5).19

One last case that is worth commenting on is the least consistent of all, paura (fear): its frequency in each translation varies so much that it is impossible to identify anomalies since there is no ‘normal’ value — even more so considering that its usual equivalent in the source text is used 47 times only, against a mean of 81 occurrences in the translations. As a matter of fact, the frequency of paura ranges from the 55 occurrences in Pareschi to more than twice as many in D’Ezio (119). The impact this has on the texts is clearly remarkable as Pareschi’s turns out to be a fearless translation, whereas D’Ezio’s is a fearful one.

English-Italian Equivalents and Outliers

The preceding section focuses on the consistency of nouns expressing emotions throughout the translations. This section relates such data to equivalent emotion-nouns in the original anglophone version of Jane Eyre.

If it is true that there is no exact correspondence between lexical systems of different languages, it is also true that, especially when languages have common origins — as is the case with English and Italian — overlapping areas do exist and can be quite broad, with occasional equivalence. Terror, for example, finds its unquestionable counterpart in the Italian terrore, there is no tangible difference between solitude and solitudine, remorse and rimorso: their substantially similar semantic core is proven not simply by common etymologies — as etymologically equivalent words can gain completely different meanings across languages and develop, for example, into false friends like actually and attualmente (currently), eventually and eventualmente (possibly) — but by semantic and pragmatic similarities. Indeed, even when etymologically different, there is no doubt that the overwhelmingly most common equivalent of love in Italian is amore, hate corresponds to odio, bitterness to amarezza, and so on and so forth. Appendix 1, at the end of this paper, provides the English-Italian equivalents for each emotion-noun as found in Jane Eyre. For the most part, the parameters applied for identifying such correspondences are: etymology, semantics, and pragmatics. Sometimes, however, the equivalence is not straightforward: in those cases, equivalence was determined on the basis of similarity in frequency and, in exceptional cases, similar words had to be grouped20 — so it happens that rage was pooled with anger, excitement with excitation, solitude with loneliness, etc.21

In spite of these adjustments, which are due to the inevitable differences in languages, there is a hefty equivalence in the frequency of most emotion-nouns between the anglophone version of Jane Eyre and the Italian ones. In light of the many factors that can and do affect the outcome of translations, which never turn out to be identical, such consistencies are indeed noteworthy. Here is a selection of the most similar emotion-nouns in terms of frequency:

|

English |

Eng. Freq. |

Mean It. Freq. |

|

|

contempt/scorn |

disprezzo |

11 |

11.9 |

|

despair/desperation |

disperazione |

20 |

23.2 |

|

emozione |

17 |

17.8 |

|

|

fury |

furia |

14 |

13.6 |

|

hope |

speranza |

57 |

60.1 |

|

jealousy |

gelosia |

9 |

8.6 |

|

love |

amore |

81 |

88 |

|

passion |

passione |

30 |

27.6 |

|

regret |

rimpianto |

7 |

7.6 |

|

relief |

sollievo |

11 |

10.2 |

|

remorse |

rimorso |

11 |

11.8 |

|

shame |

vergogna |

16 |

16.1 |

|

solitude/loneliness |

solitudine |

31 |

31.3 |

|

terror |

terrore |

17 |

17.3 |

Table 4: Similar frequencies of emotion-nouns

It could certainly be argued that there might be discrepancies between source text and target texts as to where these words occur, because each occurrence of every Italian emotion-noun is not necessarily a systematic translation of always the same corresponding English word. The most representative such case is possibly gioia, which can translate a whole range of emotions besides joy, including delight, enjoyment and bliss (see infra). This, however, does not invalidate the evidence that the impact these emotion-nouns have on the English novel as a whole is nearly identical to the one they have on the Italian translations, because what matters is the sheer amount of emotion-nouns rather than their displacement. Besides, the evidence pointing to substantial consistency is impressive.

There are exceptions, though, and they can be even more revealing than the consistencies. It could be assumed that the lack of correspondence in the frequency of emotion-nouns would concern special cases with little or no semantic overlap between English and Italian words. That is not the case. Surprisingly, common emotions such as agony, courage, excitement, happiness, joy, and the above-mentioned bitterness and hate — which all find ready-to-use equivalents in Italian — are substantially inconsistent. In Table 5, the inconsistency between English and Italian emotion-nouns is expressed in z-scores: when z-score is >+2, the emotion is under-represented in the translations, when it is <–2, it is over-represented. These reference values indicate that the frequency with which they occur in Jane Eyre is higher or lower than 95% of all other values in the normal distribution — which makes them truly exceptional. Table 5 also shows the mean difference between the mean frequency of the emotion in the Italian translations and its English equivalent in the original text:

|

English |

JE Z-score |

Mean difference |

|

|

delight |

delizia |

8.2 |

–23.5 |

|

excitement/excitation |

eccitamento/eccitazione |

3.8 |

–12.2 |

|

agony |

agonia |

6.6 |

–9.0 |

|

enjoyment |

godimento |

2.3 |

–6.4 |

|

misery |

infelicità |

2.7 |

–5.5 |

|

hate |

odio |

–2.1 |

5.7 |

|

bitterness |

amarezza |

–2.8 |

7.4 |

|

affection |

affetto |

–2.1 |

8.7 |

|

sadness |

tristezza |

–2.3 |

11.5 |

|

courage |

coraggio |

–2.4 |

14.1 |

|

happiness |

felicità |

–4.5 |

14.1 |

|

gioia |

–2.8 |

36.6 |

Table 5: Emotion-nouns whose frequency in Italian is not consistent with the source text

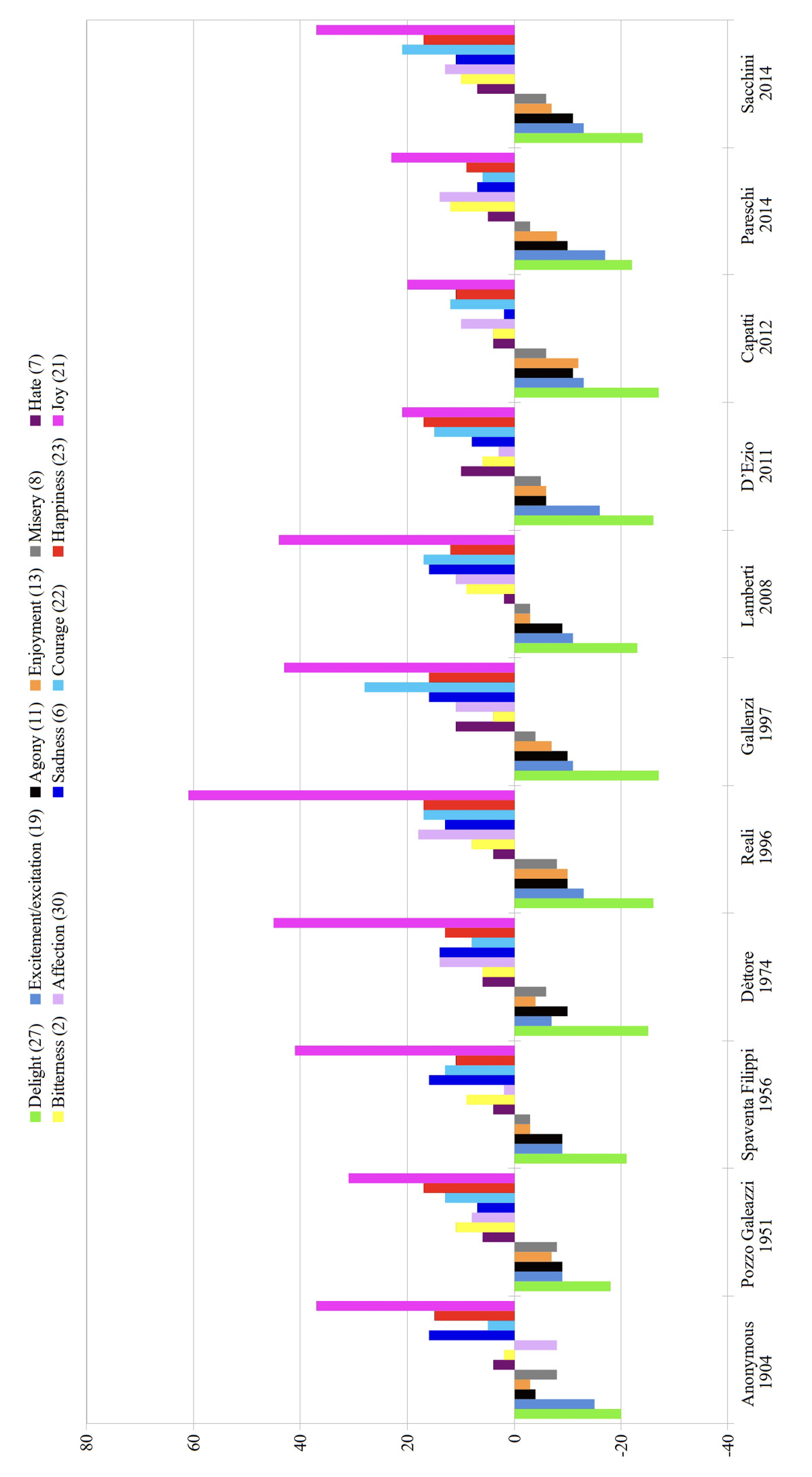

Figure 16 further elaborates the data by representing English occurrences as reference point (zero on the Y axis) and the bars indicating the difference between the frequency of emotion-nouns in the translations and the frequency of corresponding emotion-nouns in the source text (which is given in parentheses).

Thus, delight and excitement appear much less in Italian (as delizia and eccitamento) than in the original (on average –23.5 and –12.2 times respectively). Likewise, agony, enjoyment, and misery do not occur in Italian as often as in English. In Stella Sacchini’s and Bérénice Capatti’s translations, for example, agony is never used, whereas in the original there are 11 such occurrences. A close reading of the text reveals that, for example, Sacchini tends to systematically translate agony with angoscia or also miserie (miseries), but never with its closer equivalent agonia. Bars above zero indicate that the opposite is true: hate, bitterness, affection, sadness, courage, happiness, and joy are to be found much more in the translations than in the original text. Among these, the frequency of joy is outstanding. Its frequency in Italian (gioia) is higher by up to 61 occurrences (in Luisa Reali). This means that Italian readers’ general impression of the novel will be a lot more joyful than it is for readers of the English text.

Fig. 16 Difference in frequency of emotion-nouns in English and Italian

At this point it remains to be seen what happens to those emotions that tend to disappear from the translations or pop up where there is no trace of them in the original. Let us consider joy, which is the most extreme case of asymmetry, and see the reasons why there are so many instances of gioia in the Italian translations.

Reali uses the word gioia 82 times, whereas in English there are only 21 occurrences of joy — four times as many as in the original. On a closer reading of the occurrences within the text, it transpires that gioia works as a passe-partout word to be used here and there every time the translator finds it suitable: in particular, it appears that Reali systematically uses gioia to translate delight (as a matter of fact, Reali never uses its corresponding delizia at all):

it is my delight to be entreated22

È una gioia per me sentirmi pregare23

I permitted myself the delight of being kind to you24

Mi concessi la gioia di essere gentile con te25

This thus explains, on the one hand, the remarkably high frequency of gioia in Reali, as the 27 occurrences of the word delight add to the frequency of joy (21) in the source text; and, on the other hand, why the word delight is under-represented in Italian.

The following examples are from Dèttore’s translation instead. As in Reali, here too joy is nowhere to be found in the original:

I seemed to distinguish the tones of Adèle, when the door closed.26

mi parve distinguere le grida di gioia di Adèle, quando la porta venne chiusa.27

Oh, it is rich to see and hear her!28

Oh, non è una gioia vederla e udirla?29

I have at last my nameless bliss: As I love — loved am I!30

Raggiunto ho infine la mia gioia infinita: Amare… essere amato.31

and my eyes seemed as if they had beheld the fount of fruition.32

e gli occhi sembravano aver contemplato la fonte della gioia.33

The one systematic tendency that can be appreciated in Dèttore lies in the translation of enjoyment with gioia (even the example above, concerning fruition, is a reflection of such tendency, as the obsolete Middle English meaning of fruition is indeed enjoyment):34

Much enjoyment I do not expect in the life opening before me.35

Non mi aspetto molta gioia dalla vita che mi si apre dinanzi.36

It is not like such words as Liberty, Excitement, Enjoyment.37

[…] non è davvero come Libertà, Esultanza e Gioia.38

To the outliers in Figure 16 must be added the noun infelicità, which deserves some attention. It is the only case included in the selection of emotion-nouns to be used less than 10 times, either in the translations or in the source text. As a matter of fact, its usual English equivalent, unhappiness, is never used by Charlotte Brontë in Jane Eyre. Yet, it pops up here and there across the translations, with up to 5 occurrences (in Lia Spaventa Filippi, Luca Lamberti, and Monica Pareschi — while Giuliana Pozzo Galeazzi and Luisa Reali remain faithful to the original and never mention it). Infelicità is the opposite of felicità, just as unhappiness is the opposite of happiness, but Charlotte Brontë prefers using misery, never unhappiness. Misery occurs 8 times in English and it can surely be translated as miseria (there are actually several such occurrences in the translations), but the Italian word — not unlike the English one, only to a much greater extent — tends to be associated with a condition of destitution or poverty (therefore not an emotion), and this is why it happens that some Italian translators express the emotion of feeling miserable with infelicità, thus reserving the use of miseria to refer to the condition of poverty. Besides, as is well known, unhappiness is not necessarily associated with destitution — albeit just moral — and may befall anyone, even the rich and wealthy, or the otherwise non-destitute.

That unhappiness is nowhere to be found in the source text may be surprising, but it is not uncommon, since the word itself is sparsely used in other nineteenth-century novels as well: it appears only twice in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, in William Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, and in Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist; it is also never mentioned by Charlotte Brontë’s sisters Anne in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, and Emily in Wuthering Heights.

Emotional Fingerprints

The lexical idiosyncrasies of the translations in relation to the number and frequency of outliers is visually represented by means of word clouds constituting the emotional fingerprint of each translation. The aim of the previous sections was to identify those emotion-nouns that are consistently reproduced in the target texts, those that are not, and what emotions differ quantitatively the most in relation to the source text. This section revolves instead around the identification of outliers in each translation, so as to characterize them on the basis of their idiosyncrasies. Such idiosyncrasies are the actual emotional fingerprints of the translations, making them unique and distinguishable from all the others, and affecting the emotional impact of the novel on its readers. All translations have some emotional fingerprint: this is revealed by identifying and visualizing39 the extent to which the emotion-nouns that are used by a specific translator differs from the source text and from all other translations. The translation’s emotional fingerprint is therefore not a mere representation of the most frequent emotion-nouns, because it reveals what emotions set that particular translation apart from the others, hence making it one of a kind.

Fig. 17 Emotional fingerprints (i)

Fig. 18 Emotional fingerprints (ii)

Fig. 19 Emotional fingerprints (iii)

The statistics used as a basis for creating emotional fingerprints are emotion-nouns’ z-scores, calculated with reference to the mean and standard deviation of the distribution of each emotion-noun in the source text as well as in the translations. For an emotional fingerprint to be significant, it is not necessary that there should be outliers: even where all emotions are within the norm (their variability from the mean is non-remarkable), it is revealing to appreciate the idiosyncrasies of the translations, as the values fed to the cloud generator are based on the individual emotions’ z-scores in each translation. They include all z-scores >+0.1 (which indicate that the noun is used more than average). Yet, since a translation’s emotional fingerprint can also be characterized by low frequencies of certain emotions, these are likewise comprised in the cloud, with the ten lowest z-scores (i.e., the words that are used the least) coloured in grey and preceded by a minus sign. As in the previous sections, emotion-nouns lying outside the range mean ±2 standard deviations — i.e., whose z-score is either >+2 or <–2 — are considered extreme outliers.

Whenever the use of a certain item is particularly recurrent, it sticks out more. In the emotional fingerprints, the bigger the word, the more unusual it is — with the most unusually frequent words popping out with greater visibility and flashy colours, as opposed to the colour of the unusually infrequent ones, which is always grey.40

Table 6: Extreme outliers (for complete data see Appendix 2)

The 1904 anonymous translation is a semi-abridged one, therefore it is unavoidable that some nouns should be fewer than average.41 In this case, then, outliers by dearth are not really significant as their lower frequency may be due to the text being abridged. For the very same reason, the anonymous translator’s outliers in excess are particularly remarkable. Those which are used with unusual frequency are: agonia (agony), vergogna (shame), meraviglia (wonder), collera (wrath), dolore (pain), and, above all, commozione (stirring emotion) — whose z-score is a good +9.27. Stirring emotion is a label used here for a word that does not have a ready equivalent in English, and which the anonymous translator uses 12 times, i.e., once every three chapters on average. Commozione means being stirred or touched, often to tears, sometimes out of joy, sometimes out of grief — hence, stirring emotion seems to be its closest equivalent. The anonymous translator is not the only one to use commozione, as Pozzo Galeazzi (2), Spaventa Filippi (2), Dèttore (3), and Reali (2) use it too, albeit with a much lower frequency. From the gathered data, it can be evinced that there is a temporal decrease in its use, as it disappears altogether from Gallenzi’s 1997 translation onward.42 In the translations that did use it, the words commozione and emozione are equivalents of the same word emotion, even though their meaning — in current Italian — is not at all interchangeable, as commozione is a hyponym of emozione. That the 1904 translation should be one of a kind is consistent with its publication date — which certainly sets its language apart from the more recent translations — and is also compatible with the tendency this translator shows to omit whole sentences, which again is in line with the higher occurrence of negative outliers. With such a tendency to abridge, the higher frequency of positive outliers really stands out — as can be appreciated by observing its emotional fingerprint (see Figure 17).

Moving on to the second most emotionally peculiar translation, Capatti’s, there are here seven outliers: two in excess (divertimento, sconforto) and five in dearth (ammirazione, disperazione, gelosia, gratitudine, solitudine). Among these, the most remarkable is the frequent use of sconforto (discouragement), a word which is barely used by all other translators (Pozzo, Reali, Lamberti, and D’Ezio use it just once, Déttore, Pareschi, and Sacchini twice, Gallenzi three times), or never at all (anonymous, Spaventa Filippi), but which Capatti repeats 11 times. The higher frequency of such word is to be explained in several ways. A couple of occurrences, for example, are the result of the nominalization of adjectives:

All I see has made me thankful, not despondent.43

Tutto ciò che vedo mi ha fatto provare gratitudine e non sconforto.44

the most troubled and dreary look.45

uno sguardo pieno di ansia e sconforto.46

In this latter case, two pre-modifiers (the past-participle ‘troubled’, and the adjective ‘dreary’) are replaced by post-modifying nouns (ansia e sconforto). Capatti uses sconforto also when translating ‘dejection’ (3 occurrences), usually in the expression ‘to sink into dejection’ or simply ‘to sink’ (1), where sconforto clearly constitutes an over-interpreting addition:

my heart again sank47

il mio cuore sprofondò nuovamente nello sconforto.48

[I] sank into inevitable dejection49

sprofondavo nello sconforto50

sank with dejection51

sprofondato nello sconforto.52

The remaining occurrences of sconforto variously translate distress (2), depression (1), and damp (2).

After the anonymous translator’s and Capatti’s, third in order of peculiarity is Pozzo’s translation, with three extreme outliers, two of which are in excess (vergogna and delizia) and one in dearth (rabbia). The rest of the translations have only a couple of extreme outliers each, or none at all — which points to a substantial uniformity in the use of emotion-nouns across the Italian translations. Among the extreme outliers, Reali’s repetitive use of the word dubbio (doubt, 77 occurrences) is particularly striking as it concerns a highly variable word (the anonymous translation and hers are in fact the only translations to have extreme outliers in highly variable distributions). Also, the increase in frequency of such a word in the other translations, which can be observed after hers was published, might be due to an influence she might have exerted on them by virtue not only of her skills as translator but also of her renowned publisher Mondadori (Gallenzi’s 1997 translation came out just a few months after Reali’s and was probably not affected at all): be that as it may, the frequency of the word dubbio in all subsequent translations is >40, whereas before 1996 it was always <40.

As a conclusion to this section, the emotional fingerprint of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (Figure 20) is a suggestive way to summarize what it feels like to read her novel in its original form rather than in translation.

Fig. 20 Emotional fingerprint of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre

Conclusion

Analysing emotions in fiction is a mammoth task. Novels play with emotions by definition — or else they would be non-fictional pieces of writing. Simply differentiating between what expresses an emotion and what does not is in itself problematic. Comparing patterns of emotional lexis in the original as well as in eleven translations is even harder.

The first challenge of this study was to define a methodology aimed at isolating a significant portion of emotionally relevant items in the source and target texts. This portion was defined as lexical labels expressing emotions, and falling into the category of singular and plural nouns.

The second challenge was to rank the relevance of such lexis in Jane Eyre as originally written by Charlotte Brontë, in English. In order to do that, it was not only the mere frequency of individual words that was considered, but — wherever possible — similar emotions were pooled together so as to account for the reading experience, regardless of subtle differentiations in the use of synonyms or near-synonyms (e.g., despair, desperation). It goes without saying that a close reading of all 78+ emotions would comprise an analysis of nearly every single sentence of the novel — which is why the focus was limited to pointing out a few outstanding cases: love, pain, pleasure, hope, fear, wish, and passion.

The third challenge was to compare the emotional lexis in the original with that of the translations. The first step in the comparison procedure was to analyse the frequency of emotion-nouns in the translations so as to assess their consistency — or lack thereof. The findings show a general homogeneity in the frequency of most emotion-nouns, with rimorso (remorse) ranking first for consistency and disperazione (despair), felicità (happiness), and orgoglio (pride) sticking out for greater relevance given their relatively high frequency. At the other end of the consistency spectrum, there are gioia (joy), dolore (pain), and paura (fear), the latter showing a most impressive level of variability among the translations. The focus was then shifted to the similarity in frequency between the Italian emotion-nouns and their corresponding English ones, revealing them to be substantially similar in most cases, with virtually identical frequency in emotion-nouns such as contempt and disprezzo, emotion and emozione, fury and furia, jealousy and gelosia, along with several more pairs. Exceptions to the many and substantial English-Italian equivalents are a handful of emotion-nouns whose differences are illustrated in Figure 16, with delight (delizia) and joy (gioia) being, respectively, the most under-represented and the most over-represented emotion-noun in the translations.

Finally, the emotional fingerprint of each translation was the ultimate challenge, as its goal is to summarize in one image the peculiarities of something as complex as the emotional dimension of different translations of the same text. To this purpose, the use of word clouds has proven to be effective.

There are still questions that remain to be answered. Among these, there is one which is not explicitly addressed by this transversal reading of the novel, but which the emotional fingerprints silently point to: besides the usual factors influencing translatorial outputs — such as time period, intended readership, ideology, or gender — what specifically accounts for the degrees of variability and idiosyncrasies in the representation of emotions? Surely it must be a reflection of the translators’ psyche, of their subjectivity as individuals, of their poetics as writers.

Works Cited

Edition and Translations of Jane Eyre

Brontë, Charlotte, Jane Eyre, ed. with an Introduction and Notes by Stevie Davies (London: Penguin 2006).

——, Jane Eyre o le memorie di un’istitutrice, 2 vols., trans. by anonymous (Milano: Fratelli Treves, 1904).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by Giuliana Pozzo Galeazzi, with an Introduction by Oriana Palusci (Milano: Rizzoli, 1951, 1997).

——, trans. by Lia Spaventa Filippi, with an Introduction by Giuseppe Lombardo (Roma: Newton & Compton, 1956, 2002).

——, trans. by Ugo Dèttore, with an Introduction by Paolo Ruffilli (Milano: Garzanti, 1974, 1995).

——, trans. by Luisa Reali, with an Introduction by Franco Buffoni (Milano: Mondadori, 1996).

——, trans. by Alessandro Gallenzi (Milano: Frassinelli, 1997).

——, trans. by Luca Lamberti, with an Introduction by Carlo Pagetti (Torino: Einaudi, 2008).

——, trans. by Marianna D’Ezio (Firenze: Giunti Editore, 2011).

——, trans. by Bérénice Capatti (Milano: Rizzoli, 2013).

——, trans. by Monica Pareschi (Milano: Neri Pozza, 2014).

——, trans. by Stella Sacchini, with an Afterword by Remo Ceserani (Milano: Feltrinelli, 2014).

Other Sources

Alexander, Christine, The Early Writings of Charlotte Brontë (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1983).

Damasio, Antonio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain (London: Picador, 1994).

Evans, Dylan, Emotion: The Science of Sentiment (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 2001).

Gordon, Lyndall, Charlotte Brontë: A Passionate Life (London: Vintage, 1994).

Griffiths, Paul E., What Emotions Really Are: The Problem of Psychological Categories (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

Hogan, Patrick C., ‘Affect Studies’, in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature (USA: Oxford University Press, 2016), http://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.105

Levorato, Maria Chiara, Le emozioni della lettura (Bologna: il Mulino, 2000).

Stoneman, Patsy, Brontë Transformations: The Cultural Dissemination of Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights (London: Prentice Hall/Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1996).

Tan, Ed S., ‘Emotion, Art and the Humanities’, in Handbook of Emotions, 2nd edn, ed. by Michael Lewis and Jeannette M. Haviland-Jones (New York and London: Guilford Press, 2000), pp. 116–34.

Vinaya, ‘Five Reasons Why Jane Eyre Would Never Be A Bestseller in Our Times’ (December 2010), https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/135963844?book_show_action=true&from-review_page=1

WordClouds.com (Vianen: Zygomatic, 2003–2020), https://www.wordclouds.com/

Wehrs, Donald R. and Thomas Blake (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Affect Studies and Textual Criticism (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63303-9

Appendices

Appendix 1: English-Italian Emotion Nouns53

|

English |

Eng. freq. |

It. mean freq. |

It. SD |

Eng. z-score |

|

|

affection |

affetto |

30 |

40.4 |

5.0 |

–2.092 |

|

agitation |

agitazione |

3 |

7.4 |

3.7 |

–1.193 |

|

agony |

agonia |

11 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

6.626 |

|

bitterness |

amarezza |

2 |

9.9 |

2.8 |

–2.815 |

|

admiration |

ammirazione |

10 |

13.5 |

1.8 |

–1.967 |

|

love |

amore |

81 |

88.0 |

8.7 |

–0.805 |

|

anguish/distress |

angoscia |

15 |

20.1 |

5.6 |

–0.910 |

|

anxiety |

ansia |

8 |

10.7 |

7.2 |

–0.377 |

|

wrath/choler |

collera |

5 |

10.8 |

8.2 |

–0.709 |

|

commozione |

0 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

–0.919 |

|

|

compassion |

compassione |

3 |

10.4 |

4.1 |

–1.798 |

|

courage |

coraggio |

22 |

37.0 |

6.3 |

–2.372 |

|

curiosity |

curiosità |

12 |

14.7 |

2.1 |

–1.312 |

|

delight |

delizia |

27 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

8.176 |

|

disappointment |

delusione |

12 |

10.6 |

1.7 |

0.817 |

|

desire/wish54 |

desiderio/voglia |

60 |

61.7 |

5.1 |

–0.335 |

|

disgust |

disgusto |

10 |

8.6 |

2.8 |

0.508 |

|

despair/desperation |

disperazione |

20 |

23.2 |

2.9 |

–1.090 |

|

contempt/scorn |

disprezzo |

11 |

11.9 |

1.9 |

–0.486 |

|

fun |

divertimento |

2 |

4.9 |

2.5 |

–1.153 |

|

pain/grief |

dolore |

50 |

39.8 |

13.6 |

0.752 |

|

doubt |

dubbio |

52 |

48.7 |

13.0 |

0.255 |

|

excitement/excitation |

eccitamento/eccitazione |

19 |

7.1 |

3.1 |

3.786 |

|

emozione |

17 |

17.8 |

5.7 |

–0.142 |

|

|

happiness |

felicità |

23 |

37.0 |

3.1 |

–4.477 |

|

fury |

furia |

14 |

13.6 |

5.4 |

0.074 |

|

jealousy |

gelosia |

9 |

8.6 |

1.1 |

0.372 |

|

gioia |

21 |

57.6 |

13.0 |

–2.820 |

|

|

enjoyment |

godimento |

13 |

6.3 |

2.9 |

2.304 |

|

gratitude |

gratitudine |

11 |

12.5 |

3.2 |

–0.473 |

|

impatience |

impazienza |

8 |

12.0 |

2.6 |

–1.549 |

|

misery |

infelicità |

8 |

2.8 |

1.9 |

2.691 |

|

ire |

ira |

6 |

6.0 |

3.6 |

0.000 |

|

melancholy |

malinconia |

10 |

7.7 |

2.9 |

0.802 |

|

wonder |

meraviglia |

11 |

6.2 |

3.3 |

1.458 |

|

hate |

odio |

7 |

12.9 |

2.8 |

–2.102 |

|

pride |

orgoglio |

24 |

20.4 |

3.2 |

1.124 |

|

horror |

orrore |

13 |

11.5 |

3.7 |

0.400 |

|

passion |

passione |

30 |

27.6 |

5.5 |

0.433 |

|

paura |

47 |

81.2 |

20.0 |

–1.711 |

|

|

pity |

pena |

23 |

29.3 |

10.8 |

–0.584 |

|

piacere |

78 |

86.8 |

8.3 |

–1.066 |

|

|

mercy |

pietà |

11 |

25.3 |

7.7 |

–1.853 |

|

concern |

preoccupazione |

6 |

7.7 |

3.2 |

–0.537 |

|

anger/rage |

rabbia |

10 |

11.9 |

5.4 |

–0.353 |

|

remorse |

rimorso |

11 |

11.8 |

0.8 |

–1.014 |

|

regret |

rimpianto |

7 |

7.6 |

1.6 |

–0.380 |

|

discouragement |

sconforto |

0 |

2.4 |

3.1 |

–0.766 |

|

sympathy |

simpatia |

22 |

15.5 |

8.6 |

0.760 |

|

satisfaction |

soddisfazione |

6 |

12.6 |

3.8 |

–1.747 |

|

suffering/sorrow |

sofferenza |

38 |

27.1 |

8.8 |

1.237 |

|

solitude/loneliness |

solitudine |

31 |

31.3 |

5.5 |

–0.055 |

|

relief |

sollievo |

11 |

10.2 |

4.3 |

0.185 |

|

surprise |

sorpresa |

17 |

12.1 |

4.3 |

1.152 |

|

hope |

speranza |

57 |

60.1 |

4.6 |

–0.670 |

|

tenderness |

tenerezza |

6 |

13.4 |

4.5 |

–1.635 |

|

terror |

terrore |

17 |

17.3 |

6.1 |

–0.049 |

|

dread |

timore |

12 |

19.4 |

7.4 |

–1.005 |

|

torment |

tormento |

2 |

10.0 |

5.3 |

–1.512 |

|

sadness |

tristezza |

6 |

17.0 |

4.8 |

–2.277 |

|

shame |

vergogna |

16 |

16.1 |

3.3 |

–0.030 |

Appendix 2: Italian Emotion-Noun Frequency and Z-Scores55

|

Anonymous |

Pozzo |

Spaventa |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

z-score |

freq. |

|

|

affetto |

-3.701 |

22 |

-0.483 |

38 |

-1.690 |

32 |

0.724 |

44 |

1.529 |

48 |

0.121 |

41 |

0.121 |

41 |

-1.489 |

33 |

-0.080 |

40 |

0.724 |

44 |

0.523 |

43 |

|

agitazione |

0.976 |

11 |

-0.108 |

7 |

0.705 |

10 |

-1.464 |

2 |

-0.922 |

4 |

2.061 |

15 |

0.434 |

9 |

0.163 |

8 |

-0.651 |

5 |

0.434 |

9 |

-0.651 |

5 |

|

agonia |

3.836 |

7 |

0.349 |

2 |

0.349 |

2 |

-0.349 |

1 |

-0.349 |

1 |

-0.349 |

1 |

0.349 |

2 |

2.441 |

5 |

-1.046 |

0 |

-0.349 |

1 |

-1.046 |

0 |

|

amarezza |

-2.102 |

4 |

1.104 |

13 |

0.392 |

11 |

-0.677 |

8 |

0.036 |

10 |

-1.390 |

6 |

0.392 |

11 |

-0.677 |

8 |

-1.390 |

6 |

1.461 |

14 |

0.748 |

12 |

|

ammirazione |

-0.281 |

13 |

0.843 |

15 |

0.281 |

14 |

0.281 |

14 |

-0.281 |

13 |

0.843 |

15 |

0.281 |

14 |

0.843 |

15 |

-2.529 |

9 |

-0.281 |

13 |

-0.281 |

13 |

|

amore |

-0.690 |

82 |

-0.230 |

86 |

1.035 |

97 |

-0.345 |

85 |

1.035 |

97 |

-1.496 |

75 |

1.265 |

99 |

0.345 |

91 |

-1.150 |

78 |

-1.035 |

79 |

0.575 |

93 |

|

angoscia |

-2.515 |

6 |

-0.731 |

16 |

0.161 |

21 |

1.944 |

31 |

-0.375 |

18 |

0.339 |

22 |

-0.018 |

20 |

-1.088 |

14 |

-1.445 |

12 |

0.161 |

21 |

1.052 |

26 |

|

ansia |

-1.075 |

3 |

-0.377 |

8 |

-1.214 |

2 |

0.879 |

17 |

1.996 |

25 |

0.042 |

11 |

-1.075 |

3 |

-0.656 |

6 |

0.879 |

17 |

0.042 |

11 |

-0.516 |

7 |

|

collera |

2.838 |

34 |

1.981 |

27 |

0.147 |

12 |

0.269 |

13 |

1.248 |

21 |

-1.076 |

2 |

0.147 |

12 |

-0.587 |

6 |

-1.199 |

1 |

-0.587 |

6 |

-0.342 |

8 |

|

commozione |

9.104 |

12 |

0.752 |

2 |

0.752 |

2 |

1.587 |

3 |

0.752 |

2 |

-0.919 |

0 |

0.752 |

2 |

-0.919 |

0 |

-0.919 |

0 |

-0.919 |

0 |

-0.919 |

0 |

|

compassione |

0.146 |

11 |

0.632 |

13 |

-0.826 |

7 |

-0.583 |

8 |

-1.069 |

6 |

-0.826 |

7 |

0.146 |

11 |

0.875 |

14 |

1.118 |

15 |

1.604 |

17 |

-1.069 |

6 |

|

coraggio |

-1.581 |

27 |

-0.316 |

35 |

-0.316 |

35 |

-1.107 |

30 |

0.316 |

39 |

2.055 |

50 |

0.316 |

39 |

0.000 |

37 |

-0.474 |

34 |

-1.423 |

28 |

0.949 |

43 |

|

curiosità |

-2.284 |

10 |

0.146 |

15 |

1.604 |

18 |

-0.340 |

14 |

0.146 |

15 |

-0.340 |

14 |

-0.340 |

14 |

-0.340 |

14 |

-1.798 |

11 |

-0.340 |

14 |

1.604 |

18 |

|

delizia |

1.334 |

7 |

2.018 |

9 |

0.992 |

6 |

-0.376 |

2 |

-0.718 |

1 |

-1.061 |

0 |

0.308 |

4 |

-0.718 |

1 |

-1.061 |

0 |

0.650 |

5 |

-0.034 |

3 |

|

delusione |

-0.934 |

9 |

0.817 |

12 |

-0.934 |

9 |

1.401 |

13 |

1.401 |

13 |

-0.350 |

10 |

-1.518 |

8 |

-0.350 |

10 |

0.234 |

11 |

0.234 |

11 |

-0.934 |

9 |

|

desiderio/voglia |

-4.273 |

40 |

-1.319 |

55 |

0.059 |

62 |

-0.138 |

61 |

0.847 |

66 |

-1.319 |

55 |

-0.926 |

57 |

1.437 |

69 |

-0.335 |

60 |

1.241 |

68 |

0.453 |

64 |

|

disgusto |

-1.306 |

5 |

0.871 |

11 |

-1.306 |

5 |

-0.218 |

8 |

0.871 |

11 |

0.871 |

11 |

-1.306 |

5 |

0.145 |

9 |

1.233 |

12 |

-1.306 |

5 |

0.145 |

9 |

|

disperazione |

-2.452 |

16 |

-0.068 |

23 |

0.954 |

26 |

0.272 |

24 |

-0.068 |

23 |

-0.068 |

23 |

0.954 |

26 |

-0.068 |

23 |

-2.452 |

16 |

-0.409 |

22 |

0.954 |

26 |

|

disprezzo |

-0.486 |

11 |

-1.025 |

10 |

0.054 |

12 |

-1.025 |

10 |

-0.486 |

11 |

-1.025 |

10 |

1.673 |

15 |

0.054 |

12 |

-0.486 |

11 |

1.133 |

14 |

1.133 |

14 |

|

divertimento |

-1.551 |

1 |

-1.551 |

1 |

-0.358 |

4 |

0.040 |

5 |

0.437 |

6 |

0.040 |

5 |

0.040 |

5 |

-0.358 |

4 |

2.426 |

11 |

-0.358 |

4 |

-0.358 |

4 |

|

dolore |

2.741 |

77 |

1.267 |

57 |

-0.648 |

31 |

-1.312 |

22 |

-0.354 |

35 |

0.309 |

44 |

-0.427 |

34 |

1.857 |

65 |

-0.722 |

30 |

0.678 |

49 |

-0.648 |

31 |

|

dubbio |

-2.138 |

21 |

-0.749 |

39 |

-0.749 |

39 |

-0.903 |

37 |

2.185 |

77 |

-0.980 |

36 |

-0.594 |

41 |

0.255 |

52 |

0.795 |

59 |

0.332 |

53 |

0.409 |

54 |

|

eccitamento/eccitazione |

-0.986 |

4 |

0.923 |

10 |

0.923 |

10 |

1.559 |

12 |

-0.350 |

6 |

0.286 |

8 |

0.286 |

8 |

-1.305 |

3 |

-0.350 |

6 |

-1.623 |

2 |

-0.350 |

6 |

|

emozione |

-0.318 |

16 |

-1.026 |

12 |

-0.318 |

16 |

0.389 |

20 |

1.627 |

27 |

-1.911 |

7 |

0.035 |

18 |

0.212 |

19 |

-0.495 |

15 |

0.743 |

22 |

0.743 |

22 |

|

felicità |

0.320 |

38 |

0.959 |

40 |

-0.959 |

34 |

-0.320 |

36 |

0.959 |

40 |

0.640 |

39 |

-0.640 |

35 |

0.959 |

40 |

-0.959 |

34 |

-1.599 |

32 |

0.959 |

40 |

|

furia |

-1.218 |

7 |

-0.295 |

12 |

-0.295 |

12 |

-0.111 |

13 |