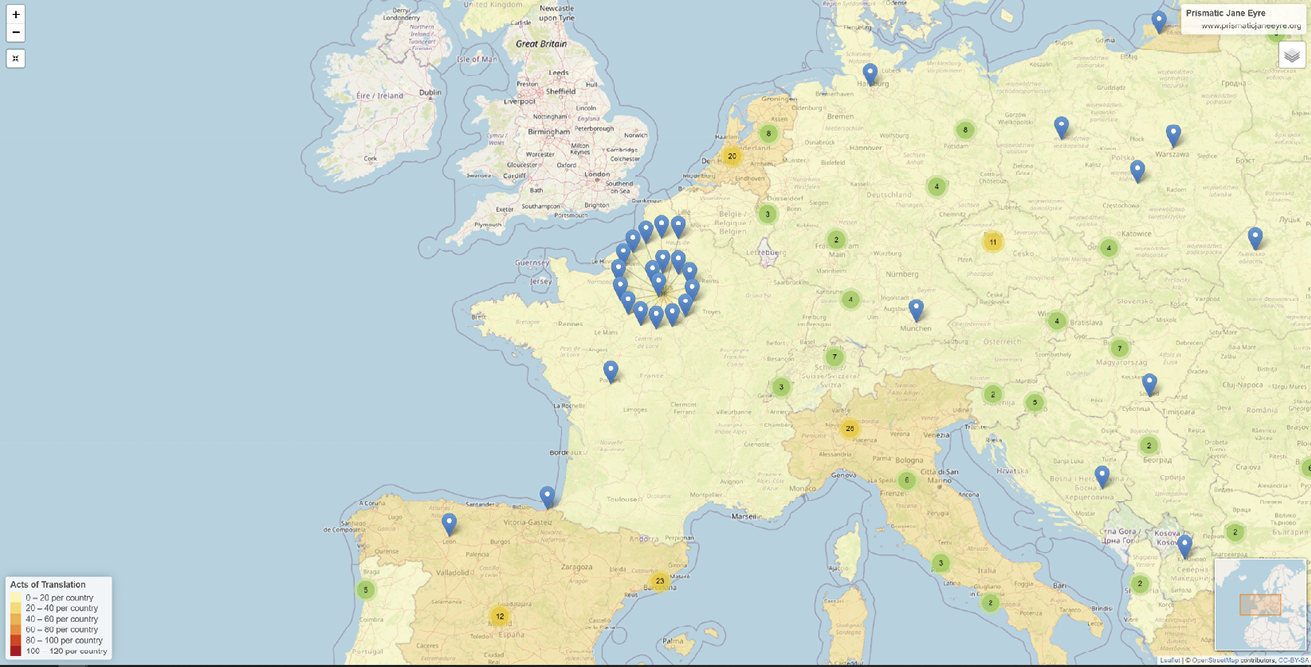

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

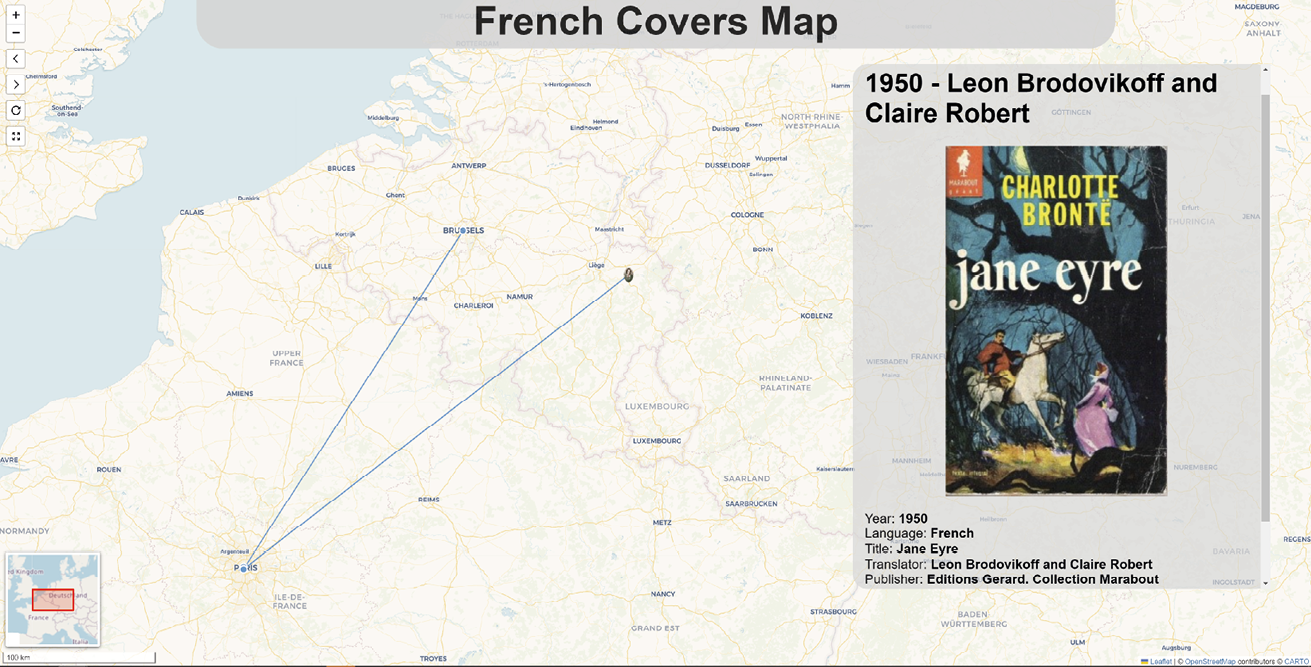

The French Covers Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/french_storymap/ Researched by Céline Sabiron, Léa Rychen and Vincent Thierry; created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci

14. Biblical Intertextuality in the French Jane Eyre

© 2023 Léa Rychen, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.21

Introduction: The Bible of Jane Eyre in Jane Eyre

In the mid-nineteenth century, English novelists tended to expect from their readership an extended knowledge of the Biblical texts, and Charlotte Brontë certainly did not depart from this principle. She was born in a parsonage as the daughter of a clergyman, and her upbringing in an Evangelical Anglican household profoundly influenced her own reading and writing.1 The centrality of Christianity in Brontë’s works is evidenced in her 1853 novel Villette and its virulent criticism of Roman Catholicism, but Jane Eyre also echoes the Christian faith. Time and again, the novel published in 1847 quotes the Bible, especially the iconic language of the King James version.2 This translation produced by the Church of England, commissioned by James VI and I in 1604 and published in 1611, is even considered by some ‘the most important book in English religion and culture’.3 Biblical intertextuality is paramount to the understanding of Jane Eyre. Along her journey, the protagonist encounters characters such as Brocklehurst, Helen and St John, whose immersion in religion radically defines their choices of actions and words. As will be studied later, Jane’s interactions with them often present her own radical interpretation of the Christian sacred text, which serves as a foundation for her reflections on life, love, meaning and purpose.

In the twenty-one different translations of Jane Eyre in French, the web of intertextual references to the Christian Bible has suffered many changes. Traduttore, traditore, as the famous saying goes: is the Biblical intertextuality of Jane Eyre betrayed in the French translations? Many factors account for such a loss, from the translators’ own styles, the cuts in the original texts, and the various translation choices, to the very history of the culture the translations are produced for. Indeed, as the history of Christianity in France dramatically differs from that in England, so too does the place of the Biblical texts and language in the literary culture. There is no French equivalent of the 1611 English Authorized Version, no canonical Bible to attach one’s religious imagery to. And as the process of secularization accelerated in the French-speaking world, that same religious imagery drastically faded for Charlotte Brontë’s future readership. Jane Eyre is written not only in English but also in the language of the Bible, with connections to its characters and stories. A comparison of seven different translations written between 1854 and 2008 shows that the French translators very often alter the significance of the Biblical allusions.4

A revelation on Revelation

‘Do you read your Bible?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘With pleasure? Are you fond of it?’

‘I like Revelations, and the book of Daniel, and Genesis and Samuel, and a little bit of Exodus, and some parts of Kings and Chronicles, and Job and Jonah.’

‘And the Psalms? I hope you like them?’

‘No, sir.’5

Early in the novel, ten-year-old Jane meets the sinister Brocklehurst who confronts her about her knowledge of the Bible. The young girl shows her singularity by citing difficult, prophetic books as her favourite ones: among them is the last book of the New Testament canon. A translation of the first word in Koine Greek, apokalypsis (which means ‘unveiling’ or ‘revelation’), the English title ranges from The Book of Revelation, Revelation to John, and Apocalypse of John, to simply The Revelation or Revelation. In French, according to tradition the title L’Apocalypse is used, after the Latin Vulgate translation apocalypsis, but the book is sometimes referred to as Livre de la Révélation or Révélation de Jésus-Christ. It is interesting to note that Charlotte Brontë writes ‘Revelations’ in the plural, an unusual form of the title which might be thought a misquotation. In the mouth of ten-year-old Jane Eyre, however, it could mean both the apocalyptic book and the apocalyptic genre, to which Daniel and Job might also pertain.

Some French translators closely follow the original and translate quite literally ‘les Révélations’ (Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, 1854;6 Brodovikoff and Robert, 1946;7 Maurat, 1964;8 and Jean, 2008),9 while the others choose ‘l’Apocalypse’.10 For the French readership, the first choice tends to obscure the direct relation to the Bible. Is the aim to draw the reader away from the clear mention of the controversial Biblical book? Is it to stick to the script of the original novel, with the equivocal word in the plural form? A comparison with another mention in the novel can help understand these translation choices.

The second instance when the book of Revelation is mentioned is in Chapter 35, when St John Rivers gives the evening reading. The shift is apparent: ‘la Révélation’ appears in one translation (Brodovikoff and Robert, 1946);11 ‘l’Apocalypse’ in all the others. The standard title is reinstated; the possibility of a play on words with all Biblical revelations disappears. However, the term ‘la Révélation’ also alludes to the Revelation of God through Jesus Christ — that is, the Christian message in its entirety — and thus gives a broader perspective on what is revealed. In the 1897 Service and Paton edition of Brontë’s text — the one reproduced electronically in Project Gutenberg — there is an evolution between the two passages, and ‘Revelations’ becomes ‘Revelation’.12 Although the original text has the plural form in both cases, the shift is significant. In between, Jane has endured all kinds of revelations as she has grown up and walked on her faith journey (the book is indeed often viewed as a female Bildungsroman). The revelations and emotions she wrestles with pave the way for a much more linear, consistent, solid truth. Jane’s vision of God, her understanding of the Bible and of herself, her own character and vision for the future have become clearer. In the novel, other instances of the term ‘revelation’ (in singular or plural form, but with a lower-case ‘r’) include the encounter with the gypsy woman (Chapter 18), Jane’s Christic vision over the bed of the wounded Mason (Chapter 20), and Jane’s critical conversations about love and duty with Rochester and St John (Chapters 20, 27, and 34). Jane’s path is fraught with revelations that lead to her own search for (Biblical) truth.

In French, translators Léon Brodovikoff and Claire Robert keep this same tension with the evolution from ‘les Révélations’ to ‘la Révélation’: this suggests that they used the Service and Paton text, or another edition that included the same variant, and that they kept very close to the English, allowing for double meanings while making the reference to the Bible less obvious. On the contrary, Marion Gilbert and Madeleine Duvivier, R. Redon and J. Dulong, and Sylvère Monod have kept ‘l’Apocalypse’ all the way through, asserting the allegiance to the Biblical book and placing Jane Eyre in a Biblical frame, while losing the possible correspondences with the character’s personal revelations. Noëmi Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, Charlotte Maurat and Dominique Jean give ‘les Révélations’ (in italics for Maurat) in the first instance, keeping ten-year-old Jane’s own words when describing the Bible, and re-establishing the official title of the Biblical book (‘l’Apocalypse’) when it is actually read through and quoted.

Jane as Felix: A Multi-Dimensional Characterisation

Still I felt that Helen Burns considered things by a light invisible to my eyes. I suspected she might be right and I wrong; but I would not ponder the matter deeply; like Felix, I put it off to a more convenient season.13

The Biblical intertextuality also lies in historical references. The allusion to Felix, the Roman procurator of Judea between 52 and 58 CE, has its roots in the Biblical passage of Acts 24, when the apostle Paul stood trial before Felix in Caesarea: ‘And after certain days, when Felix came with his wife Drusilla, which was a Jewess, he sent for Paul, and heard him concerning the faith in Christ. And as he reasoned of righteousness, temperance, and judgment to come, Felix trembled, and answered, Go thy way for this time; when I have a convenient season, I will call for thee’.14 In Charlotte Brontë’s text, Helen is equated to Paul preaching patience, acceptance and duty to a Felix-like Jane who feels compelled to embrace these truths, but postpones the commitment that such a decision entails.

The treatment of the reference in the French translations is varied: it is either cut (in Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, and Redon and Dulong), simply translated ‘comme Félix’ (in Gilbert and Duvivier,15 and Brodovikoff and Robert)16 or similarly translated with the addition of an explanatory footnote (in Monod,17 and Maurat)18 or endnote (in Jean).19 As for Redon and Dulong, they repeatedly cut Biblical references. Their translation seems to demonstrate the frailty of the Biblical presence in French literature. Still, the disappearance of this specific comparison can be viewed as an attempt to erase its masculinity, rather than its Biblical nature. Indeed, scholar Rachel Williams suggests that Lesbazeilles-Souvestre consistently negates the ‘masculine’ elements in the novel with the aim of producing a female-oriented translation.20

While the Biblical intertextuality cannot survive radical cuts, a simple reference requires the reader’s active participation and knowledge. On the other hand, accompanying notes (see following table) influence the reader’s perception of the reference, as they may emphasise several aspects of it.

|

Translator |

Date |

Note |

|

1964 |

‘Félix, proconsul, gouverneur de la Judée pour les Romains, avait épousé Drusille, princesse juive, fille du vieux roi Agrippa Ier. C’est devant Félix que comparut saint Paul à Césarée; il retint l’apôtre en prison pour plaire aux Juifs.’21 |

|

|

1966 |

‘Gouverneur de Judée (cf Actes, 24, 25).’22 |

|

|

Jean |

2008 |

‘Allusion aux Actes des apôtres, XXIV, 25: « Mais, comme Paul discourait sur la justice, sur la tempérance, et sur le jugement à venir, Félix, effrayé, dit: Pour le moment retire-toi; quand j’en trouverai l’occasion, je te rappellerai. »’23 |

Monod’s note provides the reader with information as to the referent and the origin of the comparison. It gives historical as well as Biblical background, though it emphasises the position of the man rather than his personality or actions. Maurat’s note focuses on explaining who Felix actually was. The choice of words and names denotes a wish for historical accuracy. It seems to insist on the man’s prejudicial sense of justice — using imprisonment as a springboard for his own popularity: ‘pour plaire aux Juifs’ (‘to please the Jews’). Jean’s note differs in the sense that it does not specifically explain, but instead gives the Biblical verse that the passage alludes to. Felix is only presented in his refusal to listen to and accept Paul’s teaching.

The Biblical intertextuality here resides in the syntagm ‘comme Félix’ but also in the additional comments, which shed a different light on this comparison to Jane. Felix’s portrayal — as a governor, as a man of power, as a manipulative politician, as a sceptic, as a possible truth-seeker — necessarily affects Jane Eyre’s characterisation. With one single translation, the texts then colour the protagonist in different ways.

A Proverbial Shaping of Culture

Well has Solomon said — ‘Better is a dinner of herbs where love is, than a stalled ox and hatred therewith.’24

Charlotte Brontë here quotes Proverbs 15.17 from the King James Bible. Comparison of both Catholic and Protestant Biblical verses with the French translations of Jane Eyre suggests that most of them follow the English wording rather than an official Biblical French version. Phrases like ‘un dîner d’herbe’ (chosen by Lesbazeilles-Souvestre and Maurat)25 or ‘dîner d’herbes’ (chosen by Monod,26 and Brodovikoff and Robert)27 are direct literal translations from the English text. This shows that the centrality of the Bible (especially the 1611 King James version) in nineteenth-century English literature has no parallel in the French literary spectrum. Indeed, whereas the Reformation in England led to a rejection of the Catholic Church and preservation of the Bible, in France it did quite the opposite. The Catholic Church kept its political and religious influence, but the Bible was set aside. As a result, the Bible did not shape the French language and culture, as was the case in England or Germany. Prominent writers and philosophers such as Blaise Pascal read the Bible in Latin. The Vulgate subsequently infused their works, and not a French version. There is no benchmark translation of the Bible in French, but rather many individual translations produced either by Catholics or Protestants, which differ in their choice of Hebrew and Greek or Latin as the language of the translation. It is then up to the readers to choose which translations to read.

In this passage, some translators indicate the reference of the verse, but that does not mean they quoted it from an actual French Bible. Monod mistakes Chapter 15 for 25,28 thus altering the reference. Although Maurat adds it in a note,29 she does not follow the same translation pattern as with other Biblical verses in her work (she states in a footnote that ‘toutes les références bibliques de cette traduction sont tirées de la Bible de Crampon30’)31 and provides her own version of the proverb. In fact, only Jean directly quotes from a French Bible, the Louis Segond version,32 which he says he uses for all Biblical quotations in his translation.33

Both Gilbert and Duvivier’s, and Redon and Dulong’s translations cut the whole reference altogether. It is of note that both translations are published in a post-World-War France (1919 and 1946 respectively), at a time when religious faith was strongly decreasing. Furthermore, the beginning of the twentieth century in France was marked by a series of laws undermining the Catholic Church and denying its legitimacy in the educational field. The 1904 law denied religious congregations the right to teach; the following year saw the official separation of the Church and the State. The concept of laïcité was being given a legal basis. This was a time of growing tensions, both between France and the Vatican, and within the country. The traumatic Vichy regime reinstated the funding of Catholic private schools and authorized religious congregations to teach. To counteract this, the 1946 Constitution gave laïcité a constitutional weight. The text clearly marked a separation between religion and education — considered as a ‘temporal power’ belonging only to the State. In such an atmosphere, it is understandable that some editors would be reluctant to associate forms of teaching (Jane giving a proverb) with Christianity, simply erasing the Biblical quote.

Rochester Between Job, Hobbes and Moby Dick

‘I wish to be a better man than I have been, than I am; as Job’s leviathan broke the spear, the dart, and the habergeon, hindrances which others count as iron and brass, I will esteem but straw and rotten wood.’34

Jane’s encounters with Rochester are occasions of much mystery and Jane slowly uncovers the veil of his enigmatic, poignant character. At the beginning of Chapter 15, as he opens up about his past with Céline Varens, his personality is also portrayed through a reference to the book of Job: ‘The sword of him that layeth at him cannot hold: the spear, the dart, nor the habergeon. He esteemeth iron as straw, [and] brass as rotten wood.’35 In this passage of the Bible, God is talking to Job and his three accusing friends to manifest his almighty powers and his control over creation. The parallel between Rochester’s words and the Biblical text makes him a fate-stricken, agonising man in the image of Job, as well as a control-seizing, powerful defender in the image of a God-created monster. It surrounds Rochester with an atmosphere of mystique that complexifies the character.

The reference is absent in Gilbert and Duvivier,36 and in Redon and Dulong,37 who performed major cuts to Rochester’s discourse. As we have seen, the choice to cut the Biblical reference can be viewed as an appropriation of the text in a cultural context (two post-World War periods, respectively 1919 and 1946) when secularism was intensifying and personal allegiance to Christianity was questioned. In the other translations (like Proverbs 15.17 in Chapter 8), the Biblical intertextuality does not seem to call for any correspondence with existing Biblical translations in French. The translators rather freely adapted the text in its rhythms and choice of words.

Interestingly, Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, and Brodovikoff and Robert translate ‘Leviathan’ with ‘baleine’,38 thus creating an overlap between the books of Job and Jonah. Indeed, the French term ‘baleine’ appears in some Biblical versions (e.g., 1744 Martin) to translate the Hebrew hattannûn, sea monster or gā·ḏō·wl dāḡ, great fish. It is specifically the term gā·ḏō·wl dāḡ that appears in the book of Jonah when it is said, ‘Now the LORD had prepared a great fish to swallow up Jonah. And Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights’.39 When exegetes pondered over the kind of great fish Jonah could have been swallowed up by, the possibility of a whale appeared because of its great size. But in this Chapter of Job, the Hebrew word is liw·yā·ṯān (serpent, sea monster, or dragon) which quite literally gave the English ‘Leviathan’ and the French ‘Léviathan’, sometimes translated by ‘crocodile’.

However, the French translators are not alone in the cross-over between ‘Leviathan’ and ‘whale’. Nowadays, liw·yā·ṯān means ‘whale’ in Modern Hebrew. This is also to be found in literature: the rabbinic literature traditionally associates Job and Jonah, and the Talmud suggests that the whale is doomed to be killed by the Leviathan. In his 1851 Moby-Dick, Herman Melville also describes the Leviathan as being ‘Job’s whale’ — and thus it was translated as ‘la baleine de Job’ in Moby Dick’s French translations, the first being in 1928.40 Such a phrase has the effect of drawing attention away from God (the one in the book of Job who mentions the Leviathan as an instrument of his almighty power) to Job, a mere man, and thus humanizes the reference. But by turning the Leviathan into a whale, it creates a new kind of image: the possible allusion to Hobbes disappears, and so does the fear that such a monstrous creature provokes. The whale is a much more accessible animal that one can visualize, and even hunt and dominate. With Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s, and Brodovikoff and Robert’s translations, the intertextuality goes beyond the relationship between Jane Eyre and the Bible: it also creates a dialogue between languages (Hebrew, English and French), and several texts.

Les liaisons dangereuses, or the Aftermath of Iconic Couples

‘Now, King Ahasuerus! What do I want with half your estate? Do you think I am a Jew-usurer, seeking good investment in land? I would much rather have all your confidence. You will not exclude me from your confidence if you admit me to your heart?’

‘You are welcome to all my confidence that is worth having, Jane; but for God’s sake, don’t desire a useless burden! Don’t long for poison — don’t turn out a downright Eve on my hands!’41

Several Biblical references are intertwined in the dialogue between Jane and Rochester. The proposition of giving out half the estate out of love or admiration recalls King Ahasuerus and Esther in the Old Testament (as well as Herod and Salome in the New Testament), when the king makes the extravagant promise of answering any of his lady’s wishes. The mention of Eve may refer to the woman’s temptation of her husband leading both of them to sin — or to the desire for knowledge that the fruit represents. This exchange between Jane and Rochester is therefore coloured by the echo of major ethical themes and complex couples taken from the Bible.

Again, the French translations make varying use of these references, leaving the Biblical intertextuality challenged. The whole passage is cut in Gilbert and Duvivier,42 while Lesbazeilles-Souvestre cuts the comparison with Eve. The remaining translations (including, unusually, Redon and Dulong) preserve both references. What is striking though is the use of notes, which lead to different interpretations. Both Jean and Monod felt the need to give their readership explanations about ‘roi Assuérus’, but the two explanations are radically different. Jean (as with the example from Chapter 6) quotes the whole verse from the Bible43 whereas Monod provides historical background and moves away from the strictly Biblical framework.44 He focuses on the marriage between King Ahasuerus and Esther — who hid her Jewishness from her husband following the advice of her uncle Mordecai — hence insisting on the lack of honesty within the couple. This once again proves how a single reference can foster multiple interpretations.

Jane Eyre’s Song of Lament

‘Be not far from me, for trouble is near: there is none to help.’

It was near: and as I had lifted no petition to Heaven to avert it — as I had neither joined my hands, nor bent my knees, nor moved my lips — it came: in full heavy swing the torrent poured over me. The whole consciousness of my life lorn, my love lost, my hope quenched, my faith death-struck, swayed full and mighty above me in one sullen mass. That bitter hour cannot be described: in truth, ‘the waters came into my soul; I sank in deep mire: I felt no standing; I came into deep waters; the floods overflowed me.’45

As our protagonist evolves throughout her coming-of-age journey, her own language goes through a process of refinement, being whetted against the cultural language with which she has grown up. In her despair regarding the situation with Bertha, the Psalms of David are intertwined with her own lament. Two references to Psalms follow closely in the passage quoted above, both announced by quotation marks. Here, the Biblical intertextuality wraps Brontë’s text and protagonist with a certain degree of sacredness. The first reference is to Psalm 22: ‘Be not far from me; for trouble is near; for there is none to help.’46 The second reference is an adaptation of the beginning of Psalm 69: ‘Save me, O God; for the waters are come in unto my soul. I sink in deep mire, where there is no standing: I am come into deep waters, where the floods overflow me.’47 While the introductory words ‘in truth’ reinforce the Biblical authority, the rewording of the psalm somewhat questions its legitimacy. Whose voice is true? This is a question this text seems to ask, as often with the Biblical references in Jane Eyre.

The Biblical intertextuality in French is kept more or less visible through devices such as punctuation, notes, and direct mentions of God and Scripture. Just as in the original, the psalmist’s and Jane’s words overlap. In this respect, it is interesting to note that most translations of Psalm 69 are gender neutral; but Gilbert and Duvivier’s translation denotes a male speaker (‘je suis entré’, ‘les flots m’ont submergé’);48 while Redon and Dulong’s translation denotes a female speaker (‘je suis tombée’, ‘je me suis enfoncée’).49 Whose voice is this then? It is either David’s in the Bible, Jane’s in the novel, or both undifferentiated. These grammatical additions, due to the gender-marked agreements in French, question the notion of the appropriation and interpretation of the Biblical text.

In this passage, most translators make a didactic use of notes, suggesting how little the French readership might know of the Bible. Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s (1854) and Brodovikoff and Robert’s (1946) are the only translations without accompanying notes; they are also the only ones that insert ‘Mon Dieu !’50 or ‘par Dieu !’51 at the beginning of the Biblical quotation, turning it into a direct address to God and placing the passage in a more vehemently spiritual (though not explicitly Biblical) light.

A Theological Debate at the Heart of the Novel: St John and Calvinism

The heart was thrilled, the mind astonished, by the power of the preacher: neither were softened. Throughout there was a strange bitterness; an absence of consolatory gentleness; stern allusions to Calvinistic doctrines — election, predestination, reprobation — were frequent; and each reference to these points sounded like a sentence pronounced for doom. When he had done, instead of feeling better, calmer, more enlightened by his discourse, I experienced an inexpressible sadness; for it seemed to me — I know not whether equally so to others — that the eloquence to which I had been listening had sprung from a depth where lay turbid dregs of disappointment — where moved troubling impulses of insatiate yearnings and disquieting aspirations. I was sure St. John Rivers — pure-lived, conscientious, zealous as he was — had not yet found that peace of God which passeth all understanding: he had no more found it, I thought, than had I with my concealed and racking regrets for my broken idol and lost elysium — regrets to which I have latterly avoided referring, but which possessed me and tyrannised over me ruthlessly.52

When she is around St John, Jane is in contact with not only the poetic language but also the systematic doctrines of the Bible. Later systematized by the sixteenth-century reformer John Calvin and his successors, the three doctrines mentioned in this passage (election, predestination and reprobation) find their roots in the writings of one of the first theologians, the apostle Paul. A few verses in his epistle to the Romans are often cited as justification for these doctrines: ‘Even so then at this present time also there is a remnant according to the election of grace’53 (i.e., election); ‘For whom he did foreknow, he also did predestinate to be conformed to the image of his Son, that he might be the firstborn among many brethren’54 (i.e., predestination); ‘Israel hath not obtained that which he seeketh for; but the election hath obtained it, and the rest were blinded’55 (i.e., reprobation, the opposite of the election). The term ‘reprobation’ itself does not appear in the Bible: it comes from Latin probare (prove, test) and reprobates (reproved, condemned) and describes the fate of ‘the rest’, that is, those God has not elected and predestined.

In this passage, Jane criticizes St John’s sermons for being sternly Calvinistic. Now, in order to understand the subtle criticism, it is important to recognize in this description a striking contrast with Charlotte Brontë’s own religious beliefs. Indeed, her letters and writings show that her Evangelical faith leans towards Arminianism: a theology regarding the atonement of sins as the consequence of God’s desire to see all redeemed.56 According to this view, humans’ free will and their own decision whether or not to reject God determines whether or not they will be redeemed and brought into a relationship with God. Calvinism, on the other hand, insists on man’s total depravity and inability to choose God. God’s gift of faith is only directed to those he eternally elected, and eternal punishment awaits those his grace did not touch.

Brontë grew up during ‘the heyday of Evangelical controversies’, with prominent Evangelical preachers such as Whitfield and Wesley gaining in popularity against the status quo of the Church of England.57 This led to profound divisions ‘among and between Wesleyan Methodists, Primitive Methodists, Calvinists, Arminians, and various “high” and “low” Tractarian and Evangelical Anglicans’.58 In this context, Brontë might have witnessed the fierce dispute between Calvinists and Arminianists on questions of salvation even in her own family and parsonage.59 This definitely left a mark on her novel and tainted her protagonist’s spiritual struggles when facing the differing theologies of Brocklehurst, Helen Burns and St John.

In French, there are different translations for the ‘stern allusions to Calvinistic doctrines — election, predestination, reprobation’. As we will see in the following table, the choice of words and punctuation is highly significant as it changes the meaning of the words and turns a doctrinal, heavily theological passage into a more philosophical reflection.

|

Date |

Translation |

|

|

1854 |

‘sombres allusions aux doctrines calvinistes, aux élections, aux prédestinations, aux réprobations’60 |

|

|

1919 |

passage cut |

|

|

1946 |

‘allusions sévères à des doctrines calvinistes, aux choix, aux prédestinations, aux réprobations’61 |

|

|

1946 |

‘allusions sévères aux doctrines de Calvin […] le choix, la méditation, la réprobation’62 |

|

|

1964 |

‘allusions aux sévères doctrines calvinistes sur le libre arbitre, la prédestination, la réprobation’63 |

|

|

1966 |

‘allusions sévères aux doctrines calvinistes (élection, prédestination, réprobation)’64 |

|

|

Jean |

2008 |

‘austères allusions aux doctrines calvinistes — élection, prédestination, réprobation’65 + endnote: ‘réprobation s’entend ici au sens religieux de jugement par lequel Dieu réprouve le pécheur ou refuse de le compter au nombre des élus.’66 |

The whole passage is cut by Gilbert and Duvivier, in line with the recurrent excision of explicit Christian references in their 1919 translation, which perhaps responds to the political context of growing secularism, as we have seen. Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, and Brodovikoff and Robert use the plural form (‘aux élections, aux prédestinations, aux réprobations’; ‘aux choix, aux prédestinations, aux réprobations’). This suggests an enumeration of separate facts or experiences, which the simple commas emphasise: it is not clear from the syntax whether they are conceived of as examples of Calvinist doctrines, or other themes alluded to by St John. Redon and Dulong, by stating ‘doctrines de Calvin’, put an emphasis on the reformer, presenting the man rather than the theological branch: this gives a historical more than a religious perspective. Also, the term ‘choix’ carries fewer Biblical connotations than ‘election’ and does not specifically refer to the Pauline verses (the same comment can be made about Brodovikoff and Robert’s translation). Therefore, both 1946 translations seem to reduce the Biblical intertextuality. This is even more obvious with Redon and Dulong translating ‘predestination’ with ‘méditation’, which is radically different. Meditation is not a doctrine, but rather a spiritual or even philosophical practice. One cannot but think of Descartes’ Méditations sur la philosophie première (1641) — a cornerstone in French history of thought. In the same vein, it is interesting that Maurat translates ‘election’ (God choosing those who will believe in him) by ‘le libre arbitre’ (man’s own choice to believe in God) and thus completely shifts the focus from God to man. It sheds light on Calvin as a philosopher more than a theologian, and it draws a less religious portrait of St John. Again, it seems that the spiritual is preferred over the Biblical, and the philosophical over the religious. Yet, this shift of discipline from a God-centred theology to a more humanistic philosophy comes in a passage of clear theological reflection. Indeed, Jane overtly comments on St John’s positions as ‘stern’ and invokes a Pauline expression (‘that peace of God which passeth all understanding’)67 to counterbalance his theology with her own. In the philosophical turn brought about by the French translators, one might wonder where St John might find that kind of peace. Could it come from the works of our modern philosophers?

Jane Eyre, a Marian Figure

Reader, it was on Monday night — near midnight — that I too had received the mysterious summons: those were the very words by which I replied to it. I listened to Mr. Rochester’s narrative, but made no disclosure in return. The coincidence struck me as too awful and inexplicable to be communicated or discussed. If I told anything, my tale would be such as must necessarily make a profound impression on the mind of my hearer: and that mind, yet from its sufferings too prone to gloom, needed not the deeper shade of the supernatural. I kept these things then, and pondered them in my heart.68

As we have seen, Biblical intertextuality allows for a superimposition of several voices: that of the Biblical author, that of the people in the Biblical account, that of Jane Eyre, and behind all of them that of Charlotte Brontë. This passage parallels the account of the birth of Jesus in Luke’s Gospel. When the shepherds visit Joseph and Mary and the newborn Jesus, they praise the baby as being the promised Saviour and Christ. They repeat in amazement what the angels told them. They go and spread the news all around. Luke goes on to say that ‘Mary kept these things then, and pondered them in her heart’ (Luke 2.19). It is a moment when reality (the pain of giving birth, the simplicity of the manger, the smell of the cattle) and the supernatural meet. Revelations have been made and wait to be implemented. Under the pen of Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre before Rochester becomes Mary the mother of God — the bearer of amazing truths and great responsibilities, the witness and author of pure love. This Biblical reference affects not only the characterisation of Jane, but also that of Rochester and their tumultuous, profound relationship.

In the original, the wording exactly parallels the Biblical verse, with the only change occurring in the grammatical pronouns. However, it appears in the French translations that there is very little correspondence with official Biblical versions, either Catholic or Protestant:

|

Translator |

Date |

Translation |

|

1854 |

‘Je gardai ces choses ensevelies dans mon cœur et je les méditai.’69 |

|

|

1919 |

‘Je gardai donc ces choses et les repassai dans mon cœur.’70 |

|

|

1946 |

‘Je gardai donc ces choses-là dans mon cœur et les méditai.’71 |

|

|

1946 |

‘Je gardai pour moi mes réflexions sur cet incident.’72 |

|

|

1964 |

‘Je gardai donc toutes ces choses pour moi, et les méditai dans mon cœur.’73 |

|

|

1966 |

‘Aussi je ne dis mot de ce mystère et le méditai dans mon cœur.’74 |

|

|

Jean |

2008 |

‘Aussi conservai-je en moi-même toutes ces choses que je repassai dans mon cœur.’75 + endnote ‘Citation de l’Évangile selon Luc, II, 19’76 |

Gilbert and Duvivier are probably the most faithful to the Bible, as their translation follows the verse in the Louis Segond Bible: ‘Marie gardait toutes ces choses, et les repassait dans son cœur’. The only adaptation is the substitution of ‘donc’ by ‘toutes’.

The other translations look similar but show some differences in the syntax and choice of words, which makes it harder to recognize Luke’s verse in them: Lesbazeilles-Souvestre adds the adjective ‘ensevelies’ (‘buried’), Maurat adds ‘pour moi’ (‘to myself’), Jean ‘en moi-même’ (‘for myself’) and Brodovikoff and Robert write ‘ces choses-là’ (‘those things’). Redon and Dulong’s and Monod’s translations are the most inventive with further lexical changes: ‘réflexions sur cet incident’ (‘reflexions on this incident’), ‘ce mystère’ (‘this mystery’). On the whole, the translators seem to be willing to provide their own version of the verse. Even Jean, who gives the Biblical reference in a note, rewrites it in his own way.

The superimposition of voices is then enriched by that of the translator. At first sight, the Biblical intertextuality could appear to be jeopardized. But the rewriting is also a way to give a new breath to the Biblical text, to play with the literary words and let the magic of intertextuality operate.

An Apocalyptic End: Jane, St John(s), and the Translators’ Voices

His own words are a pledge of this —

‘My Master,’ he says, ‘has forewarned me. Daily He announces more distinctly, — “Surely I come quickly!” and hourly I more eagerly respond, — “Amen; even so come, Lord Jesus!”’77

The novel ends with a final Biblical reference, which is the penultimate verse of the Bible: ‘He which testifieth these things saith, Surely I come quickly. Amen. Even so, come, Lord Jesus.’78 In the intricate game of the interaction of texts and superimposition of voices, Jane tells of St John, who writes to her by quoting from the Bible. The novel ends thus suspended, almost unfinished, with the promise of a change to come. It announces a death, more than the Second Coming, but the intertextuality allows for an array of interpretations. What is clear is that, by concluding her novel with the Bible (and its own conclusion for that matter) she adds a final touch of sacredness to her text. However, it can be argued that this sacredness does not systematically appear in the French translations:

|

Translator |

Date |

Translation |

|

1854 |

‘« Mon maître, dit-il, m’a averti; chaque jour il m’annonce plus clairement ma délivrance. J’avance rapidement, et à chaque heure qui s’écoule, je réponds avec plus d’ardeur: « Amen; Venez, Seigneur Jésus! »’79 |

|

|

1919 |

‘ — Mon Maître, dit-il, m’a averti. Chaque jour il me le fait savoir plus nettement: « Je viens bientôt ! » et, d’heure en heure, je réponds avec plus d’ardeur: « Amen; viens, Seigneur Jésus! »’80 |

|

|

1946 |

‘« Mon Maître », dit-il, « m’a prévenu. Journellement Il m’annonce plus distinctement: sans aucun doute. Je viens rapidement » et d’heure en heure je Lui réponds plus passionnément: « Amen, même ainsi, venez, Mon Seigneur! »’81 |

|

|

1946 |

‘« Mon Maître, dit-il, m’a donné l’avertissement; chaque jour il me l’annonce avec plus de netteté: je viens sûrement et rapidement, et à chaque heure je réponds avec plus de ferveur: Amen, venez, Seigneur Jésus. »’82 |

|

|

1964 |

‘« Mon maître m’a averti. De jour en jour son message se fait plus net: “J’arrive bientôt, sache-le.” Et, d’heure en heure, je réponds avec plus de ferveur: “Amen; viens donc, Seigneur Jésus.” »’83 |

|

|

1966 |

‘« Mon Maître, écrit-il, m’a averti d’avance. Chaque jour il m’annonce plus distinctement: Sois-en sûr, je viens promptement ! Et d’heure en heure, je réponds avec plus d’empressement: Amen, qu’il en soit ainsi; viens, Seigneur Jésus! »’84 |

|

|

Jean |

2008 |

‘« Mon Maître m’a averti. Chaque jour il annonce plus distinctement: “Oui, je viens bientôt !” et, chaque heure, je réponds: “Amen, viens Seigneur Jésus!”. »’85 |

Only Gilbert and Duvivier and Jean keep the Biblical reference with quotation marks and the most common French translation of that verse: ‘Je viens bientôt’.86 The other translators take away the quotation marks (apart from Maurat) and provide their own translation of the phrase, thus distancing themselves from any Biblical version. The subsequent variations both in the verb (‘venir’ (‘come’), ‘avancer’ (‘advance’), ‘arrive’ (‘arrive’)) and the adverb (‘rapidement’ (‘rapidly’), ‘sûrement’ (‘certainly’), ‘promptement’ (‘promptly’)) highlight the paradox that St John’s ‘own words’ are, in reality, those of another St John — the Biblical writer. This confusion of voices might have encouraged the translators to find their own voices, too.

Conclusion: Emerging New Voices

From the interactions with Brocklehurst and Helen Burns, to the tumultuous and conflicting relationships with Rochester and St John; in the evolution from the passionate, rebellious child to the tempered, collected woman; in all stages of her life from the pupil to the teacher, the character of Jane Eyre is made to reflect on the teaching of the Christian Bible and its incarnation in her own life. She talks to God and quotes from the King James Version. Charlotte Brontë and her protagonist, along with thousands of young English people, learnt how to read and speak with the Bible: they were influenced by its tone, its powerful imagery, its morals, and its poetry. Although we could argue that Biblical reception in Britain had been undermined by eighteenth-century rationalists and nineteenth-century scientific theories, Brontë’s readership was still used to seeing the sacred text as a reference, both in life and through literature. All in all, we can see the several faces of the Bible in Jane Eyre: a hypotext sustaining the novel, a closely read text studied and understood differently by the characters, and a reservoir of words and images that the author and her protagonist (and possibly her readership) were plunged into and shaped by.

The first French translation of Jane Eyre was published in 1854, at a time when France had long undergone a profound dechristianization which was to become officially institutionalized at the beginning of the following century. The place of the Bible as sacred scripture had gradually moved to the margins due to the hegemony of a ritualized and politicized Catholic Church, the violence of the Reformation, and the ever-growing influence of liberals and atheists among the French elite. This historical context necessarily had an impact on the number of Biblical references in the novel. Indeed, in all the French translations, the Biblical references suffer changes, metamorphoses, distortions, cuts, transformations of all sorts. Biblical verses disappear, mentions of Biblical characters or stories are cut, Brontë’s words are translated directly from the English without reference to a French Bible. The translations then appear to be a French version of the King James Bible. In their choice of words, the French translators tend to prefer the spiritual over the Biblical and the philosophical over the religious.

Biblical intertextuality thus undergoes important changes in the French translations of Jane Eyre. There seems to be a tendency to hide or disguise the Biblical verses behind the garment of the translator’s own style. Or else the translators decided to follow Jesus’ parable when he said: ‘No one tears a piece out of a new garment to patch an old one. Otherwise, they will have torn the new garment, and the patch from the new will not match the old’.87 They preferred to sew on another piece with new voices altogether, even if that meant losing the subtlety of Brontë’s intertextual fabric.

Works Cited

Translations of Jane Eyre

Brontë, Charlotte, Jane Eyre ou les mémoires d’une institutrice, trans. by Noémie Lesbazeilles-Souvestre (Paris: D. Giraud, 1854). The version used here is the electronic version provided by The Project Gutenberg.

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by R. Redon and J. Dulong (Paris: Éditions du Dauphin, 1946).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by Marion Gilbert and Madeleine Duvivier (Paris: GF Flammarion, 1990 [1919]).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean (Paris: Gallimard, 2012 [2008]).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by Léon Brodovikoff and Claire Robert (Verviers, Belgique: Gérard and Co., 1950 [1946]).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by Sylvère Monod (Paris: Pocket, 2011 [1966]).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by Charlotte Maurat (Paris: Le Livre de Poche, 1992 [1964]).

Other Sources

La Bible Segond, trans. by Louis Segond (Oxford, Paris, Lausanne, Neuchatel, Geneva: United Bible Societies, [1880] 1910).

La Sainte Bible, trans. by Augustin Crampon (Paris, Tournai, Roma: Desclée et Cie, 1923).

Les Saints Livres connus sous le nom de Nouveau Testament, trans. by John Nelson Darby (Vevey: Ch. F. Recordon, 1859).

Le Nouveau Testament, trans. by David Martin (New York: American Bible Society, 1861).

La Sainte Bible, trans. by Jean-Frédéric Ostervald (Neuchatel: A. Boyve et Cie, 1744).

La Bible du Semeur, trans. by Alfred Kuen, Jacques Buchhold, André Lovérini and Sylvain Romerowski (Charols: Excelsis, 1992).

La Traduction œcuménique de la Bible (Villiers-le-Bel: United Bible Society, Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1975).

Brontë, Charlotte, Villette, in The Project Gutenberg, produced by Delphine Lettau, Charles Franks and Distributed Proofreaders.

Crook, Richard E., ‘The Influence of the Bible on English Literature’, The Irish Church Quarterly, 4 (1911), 283–95, https://doi.org/10.2307/30067106.

Hunt, Arnold, ‘400 years of the King James Bible’, The Times Literary Supplement, 9 February 2011.

Jay, Elisabeth, ‘Jane Eyre and Biblical Interpretation’, in Jane Eyre, de Charlotte Brontë à Franco Zeffirelli, ed. by Frédéric Regard and Augustin Trapenard (Paris: Sedes, 2008), pp. 65–76.

Jeffrey, Franklin J., ‘The Merging of Spiritualities: Jane Eyre as Missionary of Love’, Nineteenth-Century Literature, 49 (1995), 456–82, https://doi.org/10.2307/2933729.

Jones, Phyllis Kelson, ‘Religious Beliefs of Charlotte Brontë, as Reflected in her Novels and Letters’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, The Open University, 1997).

Melville, Herman, Moby Dick, trans. H. Guex-Rolle (Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1989).

Williams, Rachel, ‘The reconstruction of feminine values in Mme Lesbazeille-Souvestre’s 1854 translation of Jane Eyre’, Translation and Interpreting Studies: The Journal of the American Translation and Interpreting Studies Association, 7 (2012), 19–23, https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.7.1.02wil

1 See Phyllis Kelson Jones, ‘Religious Beliefs of Charlotte Brontë, as Reflected in her Novels and Letters’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, The Open University, 1997).

2 This rings true for countless English literary works, from Shakespeare to Shelley, via Bacon, Bunyan, and Blake. See Richard E. Crook, ‘The Influence of the Bible on English Literature’, The Irish Church Quarterly, 4 (1911), 283–95.

3 David Norton, cited by Arnold Hunt, ‘400 years of the King James Bible’, The Times Literary Supplement (February 9 2011).

4 The seven French translations under study are those of Noëmi Lesbazeilles-Souvestre (1854), Marion Gilbert and Madeleine Duvivier (1919), Léon Brodovikoff and Claire Robert ([1946] 1950), R. Redon and J. Dulong (1946), Charlotte Maurat (1964), Sylvère Monod (1966), and Dominique Jean (2008).

5 JE, Ch. 4.

6 Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, The Project Gutenberg electronic text.

7 Brodovikoff and Robert, p. 39.

8 Maurat, p. 47. ‘Révélations’ is italicised.

9 Jean, p. 75.

10 See for example Redon and Dulong, p. 32.

11 Brodovikoff and Robert, p. 497.

12 See Essay 2 above for a discussion of this edition.

13 JE, Ch. 6.

14 Acts 24.24–25, in the King James Version.

15 Gilbert and Duvivier, p. 77.

16 Brodovikoff and Robert, p. 68.

17 Monod, p. 98.

18 Maurat, p. 72.

19 Jean, p. 111.

20 Noëmi Lesbazeilles-Souvestre ‘actively attempted to construct Jane Eyre as a text that is proper both for a female writer to have produced and for female readers to consume by consistently negating the so-called “masculine” elements she found in the novel. The character of Jane Eyre is significantly altered in the translation in ways that bring her more in line with conventional feminine values.’ Rachel Williams, ‘The reconstruction of feminine values in Mme Lesbazeille-Souvestre’s 1854 translation of Jane Eyre’ [Abstract], Translation and Interpreting Studies, 7 (2012), 19–33 (p. 19).

21 Maurat, p. 72.

22 Monod, p. 98.

23 Jean, p. 805.

24 JE, Ch. 8.

25 Maurat, p. 94.

26 Monod, p. 130.

27 Brodovikoff and Robert, p. 91.

28 ‘Proverbe de Salomon issu de la Bible (références 25,17)’, Monod, p. 130, note 3.

29 Maurat, p. 94, note 2.

30 La Sainte Bible de Crampon (1923), a Catholic Bible translated from the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek manuscripts.

31 Maurat, p. 47, note 1.

32 La Bible Segond ([1880] 1910), a Protestant Bible translated from the Hebrew, Aramean, and Greek manuscripts.

33 Jean, p. 141; p. 807.

34 JE, Ch. 15.

35 Job 41.26–27 in the King James Version. The precise reference depends on the Biblical versions.

36 See passage in Gilbert and Duvivier, pp. 154–55.

37 See passage in Redon and Dulong, pp. 133–35.

38 ‘la baleine de Job’, Brodovikoff and Robert, p. 177.

39 Jonah 1.17, King James Version.

40 For example, see Herman Melville, Moby Dick, trans. H. Guex-Rolle (Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1989), p. 220.

41 JE, Ch. 24.

42 See Gilbert and Duvivier, pp. 274–75.

43 ‘Allusion à Esther, V, 6: « Et pendant qu’on buvait le vin, le roi dit à Esther: Quelle est ta demande? Elle te sera accordée. Que désires-tu? Quand ce sera la moitié du royaume, tu l’obtiendras. »’ Jean, p. 818, note 2.

44 ‘Le roi Assuérus (485 à 465 avant l’ère courante), petit-fils de Cyrus, après avoir répudié son épouse Vashti, choisit pour nouvelle reine la belle Esther. Mais Esther n’avait pas révélé au roi qu’elle était juive, sur les conseils de son oncle Mordékhaï.’ Monod, p. 441, note 1.

45 JE, Ch. 26.

46 Psalms 22.11, King James Version.

47 Psalms 69.2, King James Version.

48 Gilbert and Duvivier, p. 305.

49 Redon and Dulong, p. 289.

50 Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, The Project Gutenberg electronic text.

51 Brodovikoff and Robert, p. 345.

52 JE, Ch. 30.

53 Romans 11.5, King James Version.

54 Romans 8.29, King James Version.

55 Romans 11.7, King James Version

56 See Elisabeth Jay, ‘Jane Eyre and Biblical Interpretation’, in Jane Eyre, de Charlotte Brontë à Franco Zeffirelli, ed. by Frédéric Regard and Augustin Trapenard (Paris: Sedes, 2008), pp. 65–76.

57 Franklin J. Jeffrey, ‘The Merging of Spiritualities: Jane Eyre as Missionary of Love’, Nineteenth-Century Literature, 49 (1995), 456–82 (p. 459).

58 Jeffrey, ‘The Merging of Spiritualities’, p. 459.

59 Jones, ‘Religious Beliefs of Charlotte Brontë’, p. 8.

60 Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, The Project Gutenberg electronic text.

61 Brodovikoff and Robert, p. 419.

62 Redon and Dulong, p. 342.

63 Maurat, p. 406.

64 Monod, p. 593.

65 Jean, p. 576.

66 Jean, p. 824.

67 Philippians 4.7.

68 JE, Ch. 37.

69 Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, The Project Gutenberg electronic text.

70 Gilbert and Duvivier, p. 460.

71 Brodovikoff and Robert, p. 536.

72 Redon and Dulong, p. 435.

73 Maurat, p. 515.

74 Monod, p. 753.

75 Jean, p. 726.

76 Ibid., p. 829.

77 JE, Ch. 38.

78 Revelation 22.20, King James Version.

79 Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, The Project Gutenberg electronic text.

80 Gilbert and Duvivier, p. 466.

81 Brodovikoff and Robert, p. 542.

82 Redon and Dulong, p. 440.

83 Maurat, p. 520.

84 Monod, p. 761.

85 Jean, p. 733.

86 This Biblical translation is to be found in the following versions: Ostervald, Crampon, Darby, Martin, Segond, Traduction Oecuménique de la Bible, Semeur.

87 Luke 5.36, New International Version.