The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

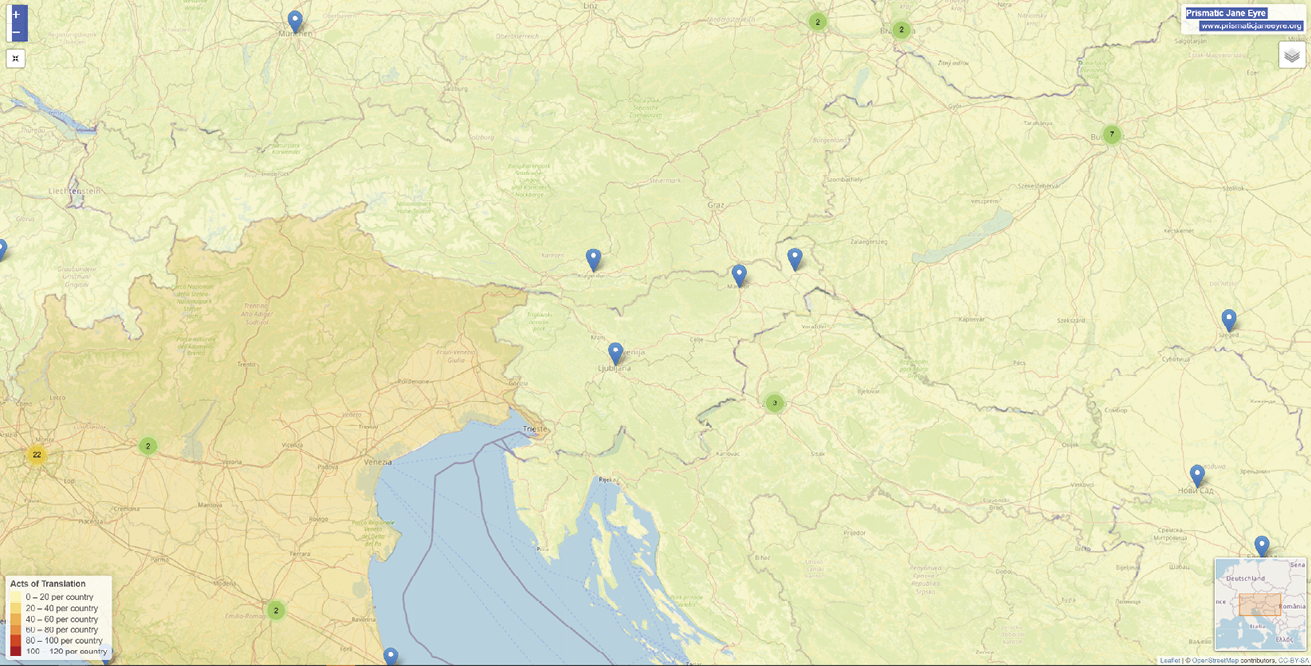

The Slovenian Covers Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/slovenian_storymap/ Researched by Jernej Habjan; created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci

15. Free Indirect Jane Eyre: Brontë’s Peculiar Use of Free Indirect Speech, and German and Slovenian Attempts to Resolve It

© 2023 Jernej Habjan, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.23

Pursuing a close reading of a global novel across languages, it makes sense to start with an element of analysis which is found in as many languages as possible without being limited to the abstract linguistic material common to those languages; an element which is in common without being simply common.1 One such element may arguably be free indirect speech: ‘an interlinguistic process’2 — as Marguerite Lips calls it in her book-length study — that uses linguistic units found globally to reach the realm of metalinguistics — to use Mikhail Bakhtin’s term for the study of polyphonic literary devices such as free indirect speech.3 Gertraud Lerch, a major influence on the Bakhtin Circle in matters of free indirect speech,4 delineates this stylistic device as follows:

In direct as well as indirect speech, the author starts by using a speech verb, a thought verb, etc. (Il dit: ‘Mon père te hait!’ or Il dit que son père la haïssait) to pin the responsibility of what was said to his characters, from whom he distances himself precisely by using this verb. In free indirect speech, however, he supresses the verb and arranges the expressions of his characters as if he took them seriously, as if these were facts and not mere utterances or thoughts (Il protesta: Son père la haïssait!). This is possible only due to the poet’s empathy with the creations of his fantasy, due to his identification with them[.]5

As a unit of analysis, free indirect speech is firmly based in linguistic features whose spread is almost as global as language itself, namely direct and indirect speech.6 It mixes these features in cognitively interesting and historically dynamic ways, using what is common to modern languages to yield results that are often anything but common. Indeed, as we will see, there is a form of free indirect speech used in Jane Eyre that is so uncommon that many translations of the novel resolve it in favour of either direct or indirect speech. In fact, the more recent the translation, the more likely it will relay this peculiar and uncommon form of free indirect speech as either common direct speech or common indirect speech.

Defined as merger of direct speech’s tone and indirect speech’s tenses and personal pronouns, there is hardly any free indirect speech in Jane Eyre; defined in this standard way, one would have to look for it in what some have recently presented as the other camp, that of Jane Austen. Indeed, John Mullan even credits Austen for inventing free indirect speech in his Intelligence Squared defence of Austen against Emily Brontë.7 Moreover, introducing his evolutionary tree of free indirect speech as the final figure of his Graphs, Maps, Trees, Franco Moretti writes that free indirect speech by leaving the individual voice a certain amount of freedom, while permeating it with the impersonal stance of the narrator’, brought about ‘an unprecedented “third” voice, intermediate and almost neutral in tone between character and narrator: the composed, slightly resigned voice of the well-socialized individual, of which Austen’s heroines — these young women who speak of themselves in the third person, as if from the outside — are such stunning examples’.8

Hence, when it comes to what we today perceive as standard free indirect style, Brontë, any Brontë, is indeed in a different camp than Austen. There is, however, quite a lot of talk in Jane Eyre that only makes sense as free indirect speech in quotation marks: speech that merges with the tenses and personal pronouns of indirect speech not only the tone of direct speech but also its quotation marks.9 Once this kind of talk in Jane Eyre is understood in this way, even the quotation marks themselves seem to start making sense: as they are invariably used in those cases of free indirect speech that the narrator finds harmful, they seem to be bracketing out that speech. And vice versa, the standard type of free indirect speech, the one without quotation marks, as rare as it is in Jane Eyre, seems to be opening itself up to the speech it is relaying, as this speech tends to be dear to the narrator. As a result, even standard indirect speech is anything but standard in Jane Eyre. In subsequent realist and modernist prose, free indirect speech will go on to become the main device for achieving, neither an opening up to the relayed speech nor a bracketing out of it, but Moretti’s ‘“third” voice’, a position that is neither the relaying narrator’s nor the relayed character’s; in Jane Eyre, however, it seems to achieve both, but by means of two distinct linguistic forms: free indirect speech without quotation marks (the standard), and free indirect speech within them. As a result, neither the standard nor its opposite seem to produce Moretti’s ‘well-socialized individual’ of an Austen heroine; in Jane Eyre, the ‘“third” voice’ is not the voice of Austen’s third-person narrator, but the voice of Jane herself: Jane the narrator bracketing out those who hurt Jane the heroine and embracing those who do not. If the Brontë camp is really different from the Austen camp, it is because it has more nuance in its free indirect speech, not less.

Free Indirect Speech within Quotation Marks

The kind of free indirect speech that uses elements of both direct and indirect speech, including the former’s quotation marks, is certainly non-standard. There is a passage in Jane Eyre where the text itself is, as it were, aware of this, as it resolves its own free indirect speech in quotation marks by taking the direction of direct speech, making the pronouns and the sequence of tenses conform to the presence of quotation marks. And since the type of free indirect speech used in this passage renders, as already mentioned, even the standard type quite non-standard, let us open with it.

I entered the shop: a woman was there. Seeing a respectably-dressed person, a lady as she supposed, she came forward with civility. How could she serve me? I was seized with shame: my tongue would not utter the request I had prepared. I dared not offer her the half-worn gloves, the creased handkerchief: besides, I felt it would be absurd. I only begged permission to sit down a moment, as I was tired. Disappointed in the expectation of a customer, she coolly acceded to my request. She pointed to a seat; I sank into it. I felt sorely urged to weep; but conscious how unseasonable such a manifestation would be, I restrained it. Soon I asked her ‘if there were any dressmaker or plain-workwoman in the village?’

‘Yes; two or three. Quite as many as there was employment for.’

I reflected. I was driven to the point now. I was brought face to face with Necessity. I stood in the position of one without a resource, without a friend, without a coin. I must do something. What? I must apply somewhere. Where?

‘Did she know of any place in the neighbourhood where a servant was wanted?’

‘Nay; she couldn’t say.’

‘What was the chief trade in this place? What did most of the people do?’

‘Some were farm labourers; a good deal worked at Mr. Oliver’s needle-factory, and at the foundry.’

‘Did Mr. Oliver employ women?’

‘Nay; it was men’s work.’

‘And what do the women do?’

‘I knawn’t,’ was the answer.10

Even though it contains indirect speech’s tenses and pronouns, the exchange in quotation marks might seem a mere linguistic alternative to the usual version of direct speech in Brontë’s time; in fact, we can trace this alternative back to the first chapter of her first novel, The Professor, in which the first-person narrator reproduces a letter in which he had written the following: ‘When I had declined my uncles’ offers they asked me “what I intended to do.”’11 However, in the last two utterances, the above exchange does use the usual version of direct speech (‘And what do the women do?’ ‘I knawn’t’), as if to imply that the preceding utterances were indeed a mix of direct and indirect speech, a mix that places them beyond any linguistic alternative and in the realm of Bakhtinian metalinguistics, the study of free indirect speech as precisely a mix of direct and indirect speech. Despite the quotation marks, the utterances only make sense as instances of free indirect speech; they can only be read in a non-contradictory manner if they are read as reported, indirect speech which is quoted, that is, as quoting while reporting.

This tension is all the more obvious if we look at translations, as they tend to resolve it in the direction of either quoting or reporting. To this end, it is sufficient to look at a couple of languages. Here, selected translations of Jane Eyre in German and Slovenian will be consulted: a Germanic language like English, and a Slavic one; a language that has produced not only numerous translations of Jane Eyre but also a scholarly monograph on them,12 and a language that has rendered Jane Eyre but twice and that has received the novel through a dramatisation written and staged precisely in the other language;13 and, finally, a language of the imperial metropole and a language of a province that had only started its struggle for sovereignty at the time when Jane Eyre was written. But all these differences curiously make the selection equally easy in both languages: the German translations are so large in number that one can simply take the first nearly complete translation and trace its fate in a very recent revision of that same translation; and the Slovenian ones are so scarce that one can just take each in one hand and consult them both at once.

None of these translations retains the original combination of quotation marks and tenses and pronouns. The strange tension between quotation marks and past tenses from the beginning of the exchange (‘Soon I asked her “if there were any dressmaker or plain-workwoman in the village?”’) is resolved by Marie von Borch in the first nearly complete German translation by simply dropping the quotation marks: ‘Gleich darauf fragte ich sie, ob im Dorfe eine Schneiderin oder eine einfache Handarbeiterin sei.’14 This solution is retained also in Martin Engelmann’s 2008 revision of the translation: ‘Ich fragte sie, ob es im Dorf wohl eine Schneiderin oder eine einfache Handarbeiterin geben würde?’15 The same holds for the two most recent German translations,16 as well as for both Slovenian translations, which respectively read ‘Čez nekoliko časa sem jo vprašala, ali imajo v vasi kakšno šiviljo ali krojačnico.’ and ‘Čez nekaj časa sem jo vprašala, ali je v vasi kakšna krojačica ali šivilja.’17

Yet as soon as Jane asks her second question, von Borch’s early German translation follows this strange type of free indirect speech to the quotation mark, as it were. As a result,

‘Did she know of any place in the neighbourhood where a servant was wanted?’

‘Nay; she couldn’t say.’

is rendered as:

‘Ob sie von irgend einer Stelle in der Nachbarschaft wisse, wo eine Dienerin gebraucht werde?’

‘Nein, sie wisse von keiner.’18

Moreover, the translation follows this paradoxical pattern even after it has been resolved by the original itself. There, as we have seen, the exchange ends with a pair of lines of this non-standard free indirect speech followed by a pair of lines of plain direct speech:

‘Did Mr. Oliver employ women?’

‘Nay; it was men’s work.’

‘And what do the women do?’

‘I knawn’t,’ was the answer.

Von Borch, however, turns the penultimate line’s direct speech back into that peculiar type of free indirect speech:

‘Ob Mr. Oliver auch Frauen beschäftige?’

‘Nein, es sei Männerarbeit.’

‘Und womit beschäftigten sich die Frauen?’

‘Weiß nicht,’ lautete die Antwort.19

It seems, then, that von Borch’s 1887–90 translation is more Catholic than the Pope; for where the original uses the final two lines of the exchange to resolve this tension in the direction of direct speech (‘“And what do the women do?”’), the translation reintroduces the tension (‘“Und womit beschäftigten sich die Frauen?”’ instead of ‘“beschäftigen”’) after it has already resolved it in the direction of indirect speech (‘Gleich darauf fragte ich sie, ob im Dorfe eine Schneiderin […] sei.’ instead of ‘fragte ich sie, “ob im Dorfe eine Schneiderin […] sei”.’).

This is resolved in 2008, when Engelmann’s revision of von Borch’s 1887–90 translation applies the initial solution in the direction of indirect speech throughout the exchange, omitting the quotation marks also in the penultimate line:

Und womit beschäftigten sich die Frauen?

‘Keine Ahnung,’ lautete die Antwort.20

This is also the direction in which the tension reintroduced by the early translation (‘“Und womit beschäftigten sich die Frauen?”’) is solved in one of the two most recent German translations, by Melanie Walz:

Und was taten die Frauen?

‘Weiß nicht’, lautete die Antwort.21

However, the most recent German translation chooses the opposite direction: following the original itself, Andrea Ott renders the last two utterances of the exchange as direct speech:

‘Und was tun die Frauen?’

‘Weiß nicht’, kam die Antwort[.]22

The same holds also for the two Slovenian translations. Here is the one by France Borko and Ivan Dolenc:

‘In s čim se ukvarjajo pri vas ženske?’

‘Ne bi mogla povedati,’ je bil odgovor.23

And here is the one by Božena Legiša-Velikonja:

‘Kaj delajo pa ženske?’

‘Ne vem,’ je bil odgovor.24

Hence, insofar as von Borch’s 1887–90 translation is updated by Engelmann in 2008 in the same way the original exchange itself is altered by its final pair of lines, one could say that the dynamics of this passage in English are refracted in the history of its German translations. In turn, this translation history mirrors the history of English prose itself: much like Engelmann and other contemporary translators of Jane Eyre (Walz or Ott in German, Borko and Dolenc or Legiša-Velikonja in Slovenian), the English novel after the Brontës, too, seems increasingly uncomfortable with the tension of quoted reporting, or, reported quoting.

But let us return to Whitcross. Jane looking for work is not the only example of this tension between direct and reported speech. In the very next substantial exchange, quotation marks are again merged with third-person pronouns and past tenses:

An old woman opened: I asked was this the parsonage?

‘Yes.’

‘Was the clergyman in?’

‘No.’

‘Would he be in soon?’

‘No, he was gone from home.’

‘To a distance?’

‘Not so far — happen three mile. He had been called away by the sudden death of his father: he was at Marsh End now, and would very likely stay there a fortnight longer.’

‘Was there any lady of the house?’

‘Nay, there was naught but her, and she was housekeeper;’ and of her, reader, I could not bear to ask the relief for want of which I was sinking; I could not yet beg; and again I crawled away.25

In German, this tension is retained in von Borch’s 1887–90 translation, but not in Engelmann’s 2008 revision, where sentences like ‘“Ob er bald nach Hause kommen würde.”’26 are relieved of their quotation marks and thus resolved as simple indirect speech,27 a solution chosen also by the two most recent translations.28 Conversely, the two Slovenian translations keep the original quotation marks and instead turn conditional verbs like the one in ‘“Would he be in soon?”’ into future verbs to get plain direct speech, as in ‘“Se bo kmalu vrnil?”’,29 which could be back-translated as ‘“Will he be in soon?”’

Similarly, as the exchange ends with Jane trying to sell her gloves and the housekeeper retorting ‘“No! what could she do with them?”’,30 this mix is retained in German in 1887–9031 but resolved as indirect speech by Engelmann in 2008, Walz in 2015, and Ott in 2016;32 indirect speech is also the solution chosen by the first Slovenian translation, while the second one chooses direct speech.33

The opposite solution, indirect speech, is chosen early on by von Borch’s translation,34 as well as by all the other translations,35 as they confront this mixture:

She had taken an amiable caprice to me. She said I was like Mr. Rivers, only, certainly, she allowed, ‘not one-tenth so handsome, though I was a nice neat little soul enough, but he was an angel.’ I was, however, good, clever, composed, and firm, like him. I was a lusus naturæ, she affirmed, as a village schoolmistress: she was sure my previous history, if known, would make a delightful romance.

[…] She was first transfixed with surprise, and then electrified with delight.

‘Had I done these pictures? Did I know French and German? What a love — what a miracle I was! I drew better than her master in the first school in S—. Would I sketch a portrait of her, to show to papa?’36

The first Slovenian translation is the only partial exception here in that it renders the final paragraph as direct rather than indirect speech. It does join the other translations, though, when it comes to rendering as plain indirect speech the following direct-indirect mix:

St. John arrived first. […] Approaching the hearth, he asked, ‘If I was at last satisfied with housemaid’s work?’37

In this case, the second Slovenian translation is the exception, only not for turning free indirect speech into direct speech like the first Slovenian translation of the previous case, but, much more surprisingly, for retaining the original tension:

Najprej se je pokazal St. John. […] Ko je stopil k štedilniku, me je vprašal, ‘ali se nisem končno že naveličala prostaškega dela služkinje?’38

But the very first example of what can only be understood as non-standard free indirect speech is to be found as early as the book’s third paragraph. Even before Mrs Reed starts to address Jane Eyre in the third person instead of the second to signal hierarchy, Jane the narrator returns the favour with interest and quotes Mrs Reed in the third person instead of the first. The result is free indirect speech that is even more polyphonic than that of Mrs Reed:

Me, she had dispensed from joining the group; saying, ‘She regretted to be under the necessity of keeping me at a distance; but that until she heard from Bessie, and could discover by her own observation, that I was endeavouring in good earnest to acquire a more sociable and childlike disposition, a more attractive and sprightly manner — something lighter, franker, more natural, as it were — she really must exclude me from privileges intended only for contented, happy, little children.’39

When, much later in the novel, Mrs Reed is reintroduced together with her third-person address, Jane the narrator does the same to Mrs Reed’s daughters, Eliza and Georgiana, quoting them in the third person instead of the first:

I asked if Georgiana would accompany her.

‘Of course not. Georgiana and she had nothing in common: they never had had. She would not be burdened with her society for any consideration. Georgiana should take her own course; and she, Eliza, would take hers.’

‘It would be so much better,’ she said, ‘if she could only get out of the way for a month or two, till all was over.’40

In Eliza’s case, this tension between quotation marks and the sequence of tenses is resolved in favour of the latter starting from 1887–90;41 the first Slovenian translation is the only one that does the opposite and drops, not the quotation marks, but the sequence of tenses to turn the original mix into direct speech.42 In Georgiana’s case, this latter solution is chosen also by the other Slovenian translation,43 as well as by von Borch’s early German edition44 and its recent revision by Engelmann, where ‘“It would be so much better,” she said, “if she could only get out of the way for a month or two […]”’ reads ‘“Es wäre so viel besser,” pflegte sie zu sagen, “wenn ich auf ein oder zwei Monate fort könnte […]”’.45

As for the book’s third paragraph, Mrs Reed is everywhere translated in the same way as Eliza, that is, as ordinary indirect speech without quotation marks.46

The early translation is less averse to mixing direct and indirect speech when it comes to sentences such as ‘“Did I like his voice?” he asked’ in Chapter 24: in 1887–90, von Borch translated this into German as ‘“Ob seine Stimme mir denn eigentlich so sehr gefiele?” fragte er.’47 Engelmann’s 2008 revision, however, omits the quotation marks to turn the sentence into indirect speech: ‘Ob seine Stimme mir denn eigentlich gefiele?, fragte er.’48 This is also the direction taken by the most recent German translations,49 while the Slovenian translations take the opposite, direct path, turning past tense into present tense and the first and third person into the second and first: ‘“Ali ti ugaja moj glas?” je vprašal.’50 and ‘“Ti je všeč moj glas?” je vprašal.’51 — which could both be back-translated as ‘“Do you like my voice?” he asked.’

As soon as this singing voice leads to serious questions, von Borch’s 1887–90 translation sobers up, as it were, and turns the free indirect style of the question into plain direct speech rather than leaving that task to Engelmann’s 2008 revision. In 1887–90 as well as 2008, the section

as he reached me, I asked with asperity, ‘whom he was going to marry now?’

‘That was a strange question to be put by his darling Jane.’52

is translated as

Als er neben mir stand, fragte ich streng: ‘Nun, wen werden Sie denn jetzt heiraten?’

‘Das ist eine seltsame Frage von den Lippen meines Lieblings, Jane!’53

This holds also for the following paragraph:

‘Indeed! I considered it a very natural and necessary one: he had talked of his future wife dying with him. What did he mean by such a pagan idea? I had no intention of dying with him — he might depend on that.’54

Both in 1887–90 and 2008, the ending ‘“he might depend on that.”’ is translated as ‘“darauf können Sie sich verlassen.”’55 instead of ‘“darauf könnte er sich verlassen.”’

Accordingly, the beginning of the section

‘Would I be quiet and talk rationally?’

‘I would be quiet if he liked, and as to talking rationally, I flattered myself I was doing that now.’56

is translated in 1887–90 as well as 2008 as ‘“Willst du jetzt still sein oder vernünftig mit mir reden?”’57 instead of ‘“Ob sie jetzt still sein oder vernünftig mit ihm reden wolle?”’

Incidentally, the second and latest Slovenian translation is the most surprising again, as it keeps the original tension of the last three examples,58 rather than resolving it in the direction of either direct or indirect speech.

To conclude this list, here is an utterance that keeps both of the two elements that are omitted in the standard type of free indirect speech, that is, not only direct speech’s quotation marks but also indirect speech’s third-person speech verbs (in this case, ‘“he had […] remarked”’ and ‘“he feared”’):

This silence damped me. I thought perhaps the alterations had disturbed some old associations he valued. I inquired whether this was the case: no doubt in a somewhat crest-fallen tone.

‘Not at all; he had, on the contrary, remarked that I had scrupulously respected every association: he feared, indeed, I must have bestowed more thought on the matter than it was worth. How many minutes, for instance, had I devoted to studying the arrangement of this very room? — By-the-bye, could I tell him where such a book was?’59

The first Slovenian translation turns this into direct speech, rendering ‘“Not at all; he had, on the contrary, remarked that I had […]”’ as ‘“Nikakor ne,” je dejal. ‘“Nasprotno! Opazil sem, da ste […]”’.60 The other translations simply omit the original quotation marks to create plain indirect speech.61 But this bifurcation, where the first Slovenian edition resolves non-standard free indirect speech in the opposite direction than the second one or the recent German translations, is to be expected by now; what is also to be expected is that, in the early German translation, the tension of the final paragraph is not simply turned into direct rather than indirect speech, as in the early Slovenian translation, but, much more interestingly, retained:

Sein Schweigen dämpfte meine Freude. Ich glaubte, daß die Veränderungen vielleicht einige alte Erinnerungen gestört hätten, welche ihm wert und lieb gewesen. Ich fragte, ob dies der Fall sei. Vielleicht in sehr niedergeschlagenem Ton.

‘Durchaus nicht. Er bemerke im Gegenteil, daß ich mit der größten Gewissenhaftigkeit alles, was ihm wert sei, geschont habe; er fürchte in der That, daß ich der Sache mehr Wichtigkeit beigelegt, als sie wert sei. Wieviel Minuten hätte ich zum Beispiel damit zugebracht, über das Arrangement dieses Zimmers nachzudenken? — Übrigens, könne ich ihm denn nicht sagen, wo dies und jenes Buch sei?’62

Finally, if we return to the beginning of Jane’s exchange with the Whitcross shop-keeper, we can also return to the standard type of free indirect speech, where quotation marks are omitted rather than kept. For the sentence ‘How could she serve me’ can now be read as free indirect speech as well:

I entered the shop: a woman was there. Seeing a respectably-dressed person, a lady as she supposed, she came forward with civility. How could she serve me? I was seized with shame: my tongue would not utter the request I had prepared.63

Indeed, all the German translations we have been consulting read ‘How could she serve me’ as free indirect speech, namely ‘Womit sie mir dienen könne?’.64 Similarly, the latest Slovenian translation has ‘S čim mi lahko postreže?’, and only the other Slovenian edition merges the sentence with the previous one to come up with a sentence characteristic of indirect speech: ‘je prodajalka vljudno prišla k meni in me vprašala, s čim mi lahko postreže.’, or, in back-translation, ‘she came forward with civility and asked me how she could serve me.’

Free Indirect Speech without Quotation Marks

If this example of standard free indirect speech seems banal, let us conclude with two examples that are far from being banal and that, moreover, are the clearest examples of this type of free indirect speech in Jane Eyre. As early as Chapter 2, Jane relays her own past speech without using either quotation marks or third-person speech verbs:

What a consternation of soul was mine that dreary afternoon! How all my brain was in tumult, and all my heart in insurrection! Yet in what darkness, what dense ignorance, was the mental battle fought! I could not answer the ceaseless inward question — why I thus suffered; now, at the distance of — I will not say how many years, I see it clearly.

Here, Jane’s past exclamations merge with her present report — that is, past exclamation points merge with the present use of the past tense — so that even her final comment on the difference between her past and her present cannot fully revoke the merger (which all the consulted translations seem to understand as they retain even the italics of ‘why’).65

But we also find free indirect speech at the opposite end of the book, in Chapter 37, where the respective positions of Jane and Rochester finally merge. The paragraph starts as indirect speech but then loses the latter’s features without gaining those of direct speech. So, at first, speech is relayed not by direct quotation but by a speech verb conjugated for a third-person pronoun, in this case ‘he said’; in time, however, this, too, is abandoned. And as the introductory ‘he said’ is gradually omitted, ‘his’ (that is, Rochester’s) speech merges with the narrator’s (that is, Jane’s):

I should not have left him thus, he said, without any means of making my way: I should have told him my intention. I should have confided in him: he would never have forced me to be his mistress. Violent as he had seemed in his despair, he, in truth, loved me far too well and too tenderly to constitute himself my tyrant: he would have given me half his fortune, without demanding so much as a kiss in return, rather than I should have flung myself friendless on the wide world. I had endured, he was certain, more than I had confessed to him.

Both here and in the translations,66 the result is an account irreducible to either of the two subject positions involved; not even the return of ‘he said’ in the form of ‘he was certain’ can revoke the merger of the two positions — especially since, as the reader already knows by this point, she indeed deliberately confessed a mere portion of what she had endured.

Whereas the quotation marks in the non-standard examples seemed to be bracketing out free indirect speech, here, in these two standard examples, the narrator relays speech as if to embrace it: as if Jane were trying to embrace first her own past speech and then Rochester’s present speech; first her past as an orphan of Lowood and then her future as Mrs Rochester; first her past self and then her future other; first her virtue and then her reward. And as an item, the two standard examples of free indirect speech, the one from the second chapter and the one from the second last chapter, seem to embrace Jane Eyre itself.

Finally, as the type of free indirect speech represented by these two examples has been made standard simply by the subsequent development of prose narrative, be it original or translated, one could say that this type, where Jane Eyre and hence Jane Eyre are embraced, is in turn embraced by translators and rewriters, to the point that it is now standard. Conversely, the other kind of example, where speech harmful to Jane is bracketed out, is itself increasingly avoided and thus made non-standard by those who translate and write in the wake of Jane Eyre. Jane Eyre itself belongs to the historical moment when novelists were still allowed to rely on quotation marks to produce the effect of free indirect style while already having the possibility of dispensing with quotation marks and practising free indirect style as it is known today. As a whole, Jane Eyre is a kind of merger of these two ways of merging direct and indirect speech, one of which has since become the standard and one of which this essay has tried to valorise by looking at how it has fared in translation.

Works Cited

Translations of Jane Eyre

Brontë, Charlotte, Jane Eyre, trans. by Božena Legiša-Velikonja (Ljubljana: Založništvo slovenske knjige, 1991).

——, Jane Eyre, die Waise von Lowood. Eine Autobiographie, trans. by Martin Engelmann (Berlin: Aufbau-Taschenbuch, 2008).

——, Jane Eyre. Eine Autobiographie, trans. by Melanie Walz (Berlin: Insel, 2015).

——, Jane Eyre. Roman, trans. by Andrea Ott (Zürich: Manesse, 2016).

——, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by France Borko and Ivan Dolenc (Maribor: Večer, 1955).

Other Sources

Bakhtin, Mikhail, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, trans. by Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

Bell, Currer, Jane Eyre, die Waise von Lowood. Eine Autobiographie, trans. by M.[arie] von Borch (Leipzig: Philipp Reclam jun., [1887–90]).

Birch-Pfeiffer, Charlotte, ‘Die Waise aus Lowood. Schauspiel in zwei Abtheilungen und vier Acten. Mit freier Benutzung des Romans von Currer Bell’, in Gesammelte dramatische Werke (Leipzig: Reclam, 1876), XIV, pp. 33–147.

——, Jane Eyre or The Orphan of Lowood: A Drama in Two Parts and Four Acts, trans. by Clifton W. Tayleure (New York: Fourteenth Street Theatre, 1870).

——, Lowoodska sirota: igrokaz v dveh oddelih in 4 dejanjih / po Currer Bellovem romanu nemški spisala Charlotte Birch-Pfeifer, trans. by Dav.[orin] Hostnik (Ljubljana: Dramatično društvo, 1877).

Brontë, Charlotte, The Professor (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1857).

Fludernik, Monika, The Fictions of Language and the Languages of Fiction (London and New York: Routledge, 1993).

Güldemann, Tom, Quotative Indexes in African Languages: A Synchronic and Diachronic Survey (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2008), https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110211450

Hohn, Stefanie, Charlotte Brontës Jane Eyre in deutscher Übersetzung. Geschichte eines kulturellen Transfers (Tübingen: Narr, 1998).

Lerch, Gertraud, ‘Die uneigentliche direkte Rede’, in Idealistische Neuphilologie: Festschrift für Karl Vossler, ed. by Victor Klemperer and Eugen Lerch (Heidelberg: C. Winter, 1922), pp. 107–19.

Lips, Marguerite, Le style indirect libre (Paris: Payot, 1926).

Moretti, Franco, Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for Literary History (London and New York: Verso, 2005).

Page, Norman, Speech in the English Novel: Second Edition (Houndmills and London: Macmillan, 1988).

Tatlock, Lynne, ‘Canons of International Reading: Jane Eyre in German around 1900’, in Die Präsentation Kanonischer Werke um 1900. Semantiken, Praktiken, Materialität, ed. by Philip Ajouri (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2017), pp. 121–46, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110549102-008

Toner, Anne, Jane Austen’s Style: Narrative Economy and the Novel’s Growth (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108539838

Vološinov, Valentin N., Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, trans. by Ladislav Matejka and I. R. Titunik (New York and London: Seminar Press, 1973).

Wagner, Erica, et al., ‘Jane Austen vs. Emily Brontë: The Queens of English Literature Debate’ (Intelligence2, 2014), https://intelligencesquared.com/events/jane-austen-vs-emily-bronte/

1 This book chapter was written at the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts in the framework of the research programme ‘Studies in Literary History, Literary Theory and Methodology’ (P6-0024 [B]), which was funded by the Slovenian Research Agency.

2 Marguerite Lips, Le style indirect libre (Paris: Payot, 1926), p. 216, my translation.

3 See Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, trans. by Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), pp. 181–85, 202.

4 See Valentin N. Vološinov, Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, trans. by Ladislav Matejka and I. R. Titunik (New York and London: Seminar Press, 1973), pp. 141–59.

5 Gertraud Lerch, ‘Die uneigentliche direkte Rede’, in Idealistische Neuphilologie: Festschrift für Karl Vossler, ed. by Victor Klemperer and Eugen Lerch (Heidelberg: C. Winter, 1922), pp. 107–19 (p. 108), my translation. The examples in French translate as ‘He said: “My father hates you!”’, ‘He said that his father hated her’, and ‘He protested: his father hated her!’ respectively; the combination of the reporter’s tenses and pronouns and the reportee’s exclamation point (or, in negative terms, the absence of both quotation marks and the conjunction that) makes the final example a mix of the other two.

6 Language typologist Tom Güldemann even claims that one of these two features, direct speech, may be ‘universal’; following such a strong category, his formulation that the other feature is ‘missing’ from or ‘restricted’ in ‘a number of languages’ does nothing to suggest that it is not global. See Tom Güldemann, Quotative Indexes in African Languages: A Synchronic and Diachronic Survey (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2008), p. 9.

7 See Erica Wagner et al., ‘Jane Austen vs. Emily Brontë: The Queens of English Literature Debate’ (Intelligence2, 2014), https://intelligencesquared.com/events/jane-austen-vs-emily-bronte/

8 Franco Moretti, Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for Literary History (London and New York: Verso, 2005), p. 82.

9 The habit of novelists to add quotation marks to indirect and free indirect speech has been noted by scholars, as has been the fading of this convention around the time Charlotte Brontë became a novelist. That the change in the convention might imply a change in free indirect speech itself has not been considered, however, even though free indirect speech has been rightly approached as precisely a set of conventions. See Norman Page, Speech in the English Novel: Second Edition (Houndmills and London: Macmillan, 1988), p. 31; Monika Fludernik, The Fictions of Language and the Languages of Fiction (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), pp. 226, 150; Anne Toner, Jane Austen’s Style: Narrative Economy and the Novel’s Growth (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), p. 173.

10 JE, Ch. 28. Here and in subsequent quotations I bold those quotation marks, tenses, and pronouns which together create what I call non-standard free indirect speech.

11 Currer Bell, The Professor (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1857), p. 4.

12 See Stefanie Hohn, Charlotte Brontës Jane Eyre in deutscher Übersetzung. Geschichte eines kulturellen Transfers (Tübingen: Narr, 1998); for an English-language chapter-length study based on this book, see Lynne Tatlock, ‘Canons of International Reading: Jane Eyre in German around 1900’, in Die Präsentation Kanonischer Werke um 1900. Semantiken, Praktiken, Materialität, ed. by Philip Ajouri (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2017), pp. 121–46.

13 See Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer, ‘Die Waise aus Lowood. Schauspiel in zwei Abtheilungen und vier Acten. Mit freier Benutzung des Romans von Currer Bell’, in Gesammelte dramatische Werke, vol. 14 (Leipzig: Reclam, 1876), pp. 33–147; for the Slovenian translation, see Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer, Lowoodska sirota: igrokaz v dveh oddelih in 4 dejanjih / po Currer Bellovem romanu nemški spisala Charlotte Birch-Pfeifer, trans. by Dav.[orin] Hostnik (Ljubljana: Dramatično društvo, 1877). For the dual-language German-English edition, see Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer, Jane Eyre or The Orphan of Lowood: A Drama in Two Parts and Four Acts [trans. by Clifton W. Tayleure] (New York: Fourteenth Street Theatre, 1870).

14 Currer Bell, Jane Eyre, die Waise von Lowood. Eine Autobiographie, trans. by M.[arie] von Borch (Leipzig: Philipp Reclam jun.[, 1888]), p. 522.

15 Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, die Waise von Lowood. Eine Autobiographie, trans. by Martin Engelmann (Berlin: Aufbau-Taschenbuch, 2008), p. 503.

16 See Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre. Eine Autobiographie, trans. by Melanie Walz (Berlin: Insel, 2015), p. 432; and Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre. Roman, trans. by Andrea Ott (Zürich: Manesse, 2016), p. 403.

17 Charlotte Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by France Borko and Ivan Dolenc (Maribor: Večer, 1955), p. 448; and Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. II, trans. by Božena Legiša-Velikonja (Ljubljana: Založništvo slovenske knjige, 1991), p. 316.

18 Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 522.

19 Ibid., p. 522.

20 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 503.

21 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 433.

22 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, p. 404.

23 Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, p. 449.

24 Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 2, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 317.

25 JE, Ch. 28.

26 Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 525.

27 See Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 506.

28 See Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 434; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, p. 406.

29 Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, p. 451; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 2, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 318.

30 JE, Ch. 28.

31 See Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 525.

32 See Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 506; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 435; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, p. 406.

33 See Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, p. 452; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 2, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 318.

34 See Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, pp. 589–90.

35 See Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, pp. 568–69; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 487; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, pp. 457–58; Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, pp. 507–8; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 2, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, pp. 356–57.

36 JE, Ch. 32.

37 JE, Ch. 34.

38 Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 2, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, pp. 378–79.

39 JE, Ch. 1.

40 JE, Ch. 21.

41 See Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, pp. 372–73; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, pp. 358–59; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 310; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, p. 286; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 1, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 223.

42 See Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, p. 319.

43 See Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 1, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 224.

44 See Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 373.

45 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 359.

46 See Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, pp. 3–4; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 5; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 13; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, p. 5; Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, p. 5; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 1, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 5.

47 Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 432.

48 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 414.

49 See Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 358; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, p. 331.

50 Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, p. 371.

51 Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 2, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 264.

52 JE, Ch. 24. In Charlotte Brontë: Style in the Novel (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1973), p. 36, Margot Peters characterises this passage as ‘direct indirect discourse’, a term that tries to say as much as my ‘free indirect speech within quotation marks’, but whose elegance comes at the price of entirely losing the connection with the concept of free indirect speech. Perhaps this is the reason why Peters applies the term only to this example of what I describe as free indirect speech within quotation marks.

53 Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, pp. 433–34; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 417.

54 JE, Ch. 24.

55 Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 434; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 417.

56 JE, Ch. 24.

57 Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 434; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 418.

58 See Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 2, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, pp. 265–66.

59 JE, Ch. 34.

60 See Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, p. 541.

61 See Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 606; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 518; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, p. 488; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 2, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 379.

62 Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 627.

63 JE, Ch. 28.

64 Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 521; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 502; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 432; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, p. 403.

65 See Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 17; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, p. 18; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 24; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, p. 16; Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, p. 17; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 1, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 13.

66 See Bell, Jane Eyre, trans. by von Borch, p. 705; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Engelmann, pp. 681–82; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Walz, p. 581; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Ott, pp. 549–50; Brontë, Sirota iz Lowooda, trans. by Borko and Dolenc, p. 610; and Brontë, Jane Eyre, vol. 2, trans. by Legiša-Velikonja, p. 424.